University of Leicester Library Answers: Academic skills

Browse our answers.

- Academic Skills Support

- Where can I get support for study skills? Last Updated: Feb 19, 2024 | Views: 71

Follow the Library on:

Contact us:.

University of Leicester Library, University Road, Leicester, LE1 7RH

- Arts & Humanities

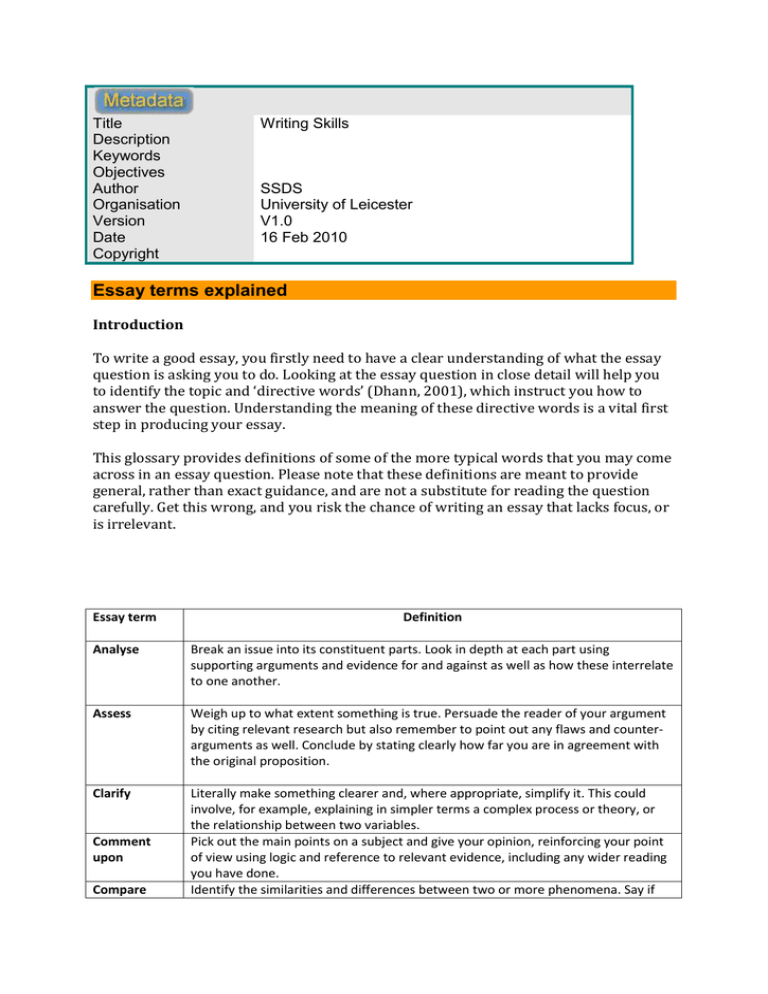

Essay terms explained - University of Leicester

Related documents

Add this document to collection(s)

You can add this document to your study collection(s)

Add this document to saved

You can add this document to your saved list

Suggest us how to improve StudyLib

(For complaints, use another form )

Input it if you want to receive answer

Attention! Your ePaper is waiting for publication!

By publishing your document, the content will be optimally indexed by Google via AI and sorted into the right category for over 500 million ePaper readers on YUMPU.

This will ensure high visibility and many readers!

Your ePaper is now published and live on YUMPU!

You can find your publication here:

Share your interactive ePaper on all platforms and on your website with our embed function

Writing Guide 1: Writing an Assessed Essay - University of Leicester

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

School <strong>of</strong> Law<br />

MPHIL/PHD IN LAW<br />

<strong>Writing</strong> <strong>Guide</strong> 1: <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>an</strong> <strong>Assessed</strong> <strong>Essay</strong><br />

ROBIN C A WHITE<br />

7 th Edition 2009 www.le.ac.uk/law

© Robin C A White <br />

<strong>an</strong>d <br />

School <strong>of</strong> Law, The <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Leicester</strong> 2009 <br />

<br />

Published by the School <strong>of</strong> Law, The <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Leicester</strong> <br />

All rights reserved <br />

The author asserts his moral rights <br />

No part <strong>of</strong> this publication may be reproduced, tr<strong>an</strong>smitted, tr<strong>an</strong>scribed, stored in a retrieval system or <br />

tr<strong>an</strong>slated into <strong>an</strong>y other l<strong>an</strong>guage in <strong>an</strong>y form whatsoever or by <strong>an</strong>y me<strong>an</strong>s without the written permission <strong>of</strong> <br />

the copyright holder <strong>an</strong>d publisher. <br />

Feedback from users is welcomed. Please contact: <br />

School Administrator, School <strong>of</strong> Law, The <strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Leicester</strong>, <strong>University</strong> Road, <strong>Leicester</strong> LE1 7RH <br />

Tel +44 116 252 2363 Fax +44 116 252 5023 email [email protected] <br />

Acknowledgments <br />

M<strong>an</strong>y colleagues <strong>an</strong>d students have contributed ideas to the various editions. Particular th<strong>an</strong>ks in connection <br />

with this edition go to Bri<strong>an</strong> Marshall in the David Wilson Library, Stuart Johnson in the Student Learning <br />

Centre, <strong>an</strong>d Stella Smyth <strong>of</strong> the English L<strong>an</strong>guage Teaching Unit. <br />

This guide is also available in electronic form on the School <strong>of</strong> Law’s web pages <br />

www.le.ac.uk/law/ <br />

CONTENTS<br />

Who should use this guide .......................................................................................................................... 1<br />

<strong>Assessed</strong> essays ........................................................................................................................................... 1<br />

The basics .................................................................................................................................................... 2<br />

Our expectations ......................................................................................................................................... 2<br />

Requirements .............................................................................................................................................. 2<br />

<strong>Essay</strong> questions <strong>an</strong>d problem questions .......................................................................................... 2<br />

Word limits ....................................................................................................................................... 3<br />

Submission deadlines ....................................................................................................................... 3<br />

M<strong>an</strong>aging your time .................................................................................................................................... 4<br />

Underst<strong>an</strong>ding the question........................................................................................................................ 5<br />

Topic are, focus <strong>an</strong>d instruction ....................................................................................................... 5<br />

<strong>Essay</strong> questions ................................................................................................................................ 5<br />

Problem questions ........................................................................................................................... 5<br />

Selecting a question from a list ........................................................................................................ 6<br />

Gathering material ...................................................................................................................................... 6<br />

Pl<strong>an</strong>ning ............................................................................................................................................ 6<br />

Research ........................................................................................................................................... 7<br />

Web-based resources ...................................................................................................................... 7<br />

Note taking ....................................................................................................................................... 8<br />

Avoiding plagiarism ..................................................................................................................................... 8<br />

Your ideas .................................................................................................................................................... 9<br />

Pl<strong>an</strong>ning your <strong>an</strong>swer ................................................................................................................................ 10<br />

Expressing yourself clearly ........................................................................................................................ 10<br />

Some general principles ................................................................................................................. 10<br />

Using gender neutral l<strong>an</strong>guage ...................................................................................................... 11<br />

Some general practices in writing .................................................................................................. 12<br />

<strong>Writing</strong> <strong>an</strong>d revising a draft ....................................................................................................................... 13<br />

The first draft is for you .................................................................................................................. 13<br />

The introduction............................................................................................................................. 13<br />

The body <strong>of</strong> the <strong>an</strong>swer ................................................................................................................. 13<br />

The conclusion ............................................................................................................................... 14<br />

Revising the first draft .................................................................................................................... 14<br />

The bibliography ............................................................................................................................ 15

Using your tutor effectively ....................................................................................................................... 15<br />

Word processing........................................................................................................................................ 15<br />

Specific requirements for particular essays .............................................................................................. 16<br />

Feedback on your work ............................................................................................................................. 16<br />

Some resources ......................................................................................................................................... 16<br />

Citing authorities<br />

The Oxford St<strong>an</strong>dard for the Citation <strong>of</strong> Legal Authorities........................................................................ 18<br />

Primary <strong>an</strong>d secondary sources ................................................................................................................ 18<br />

Using footnotes ......................................................................................................................................... 18<br />

Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 18<br />

Frequently cited material ............................................................................................................... 19<br />

Location references ........................................................................................................................ 19<br />

Signals used in footnotes ............................................................................................................... 20<br />

Some key rules in citing legal materials .................................................................................................... 20<br />

Cases .............................................................................................................................................. 20<br />

Statutes .......................................................................................................................................... 20<br />

Books .............................................................................................................................................. 21<br />

Journal articles ............................................................................................................................... 21<br />

Square brackets <strong>an</strong>d round brackets ............................................................................................. 21<br />

Recognized abbreviations <strong>of</strong> journals ............................................................................................ 21<br />

Use <strong>of</strong> full stops .............................................................................................................................. 21<br />

Appendix: Critical <strong>Writing</strong>

<strong>University</strong> <strong>of</strong> <strong>Leicester</strong>, School <strong>of</strong> Law<br />

1<br />

THE WRITING GUIDE<br />

WHO SHOULD USE THIS GUIDE<br />

This guide is written for undergraduates writing practice essays, semester essays, <strong>an</strong>d course work in law. It is<br />

directed primarily at those modules which are assessed by course work, though much <strong>of</strong> what it says is equally<br />

relev<strong>an</strong>t to writing essays which do not count for formal assessment.<br />

There are three types <strong>of</strong> essay which form part <strong>of</strong> the undergraduate syllabus in law:<br />

Practice essays: these are essays whose purpose is formative, that is, to allow you to practise your writing.<br />

They do not count towards your final grade in the module. But failure to submit practice essays is recorded<br />

<strong>an</strong>d treated in much the same way as <strong>an</strong> unexplained absence from a tutorial.<br />

Semester essays: those courses which consist <strong>of</strong> two modules running back to back across the two semesters<br />

<strong>an</strong>d which do not have <strong>an</strong>y course work component include a requirement that each student produce a<br />

semester essay at the end <strong>of</strong> the first semester. It does not count towards the final grade in the two modules.<br />

However, visiting students here for only one semester may be formally assessed through semester essays.<br />

Course work refers to written work undertaken outside the examination room which counts, in whole or in<br />

part, for the final grade in the module.<br />

This guide addresses the task <strong>of</strong> writing essays, <strong>of</strong> structuring your arguments, <strong>of</strong> properly referencing your<br />

material, <strong>an</strong>d <strong>of</strong> presenting your material in <strong>an</strong> attractive m<strong>an</strong>ner.<br />

There is a more adv<strong>an</strong>ced guide entitled <strong>Writing</strong> a Research Paper, which is written for final year<br />

undergraduates writing dissertations <strong>an</strong>d for taught postgraduates writing research papers <strong>an</strong>d dissertations<br />

on their degree programmes.<br />

It is import<strong>an</strong>t to spend some time studying the conventions <strong>of</strong> legal writing as presented in this guide before<br />

starting to write your first essay. There is no reason why, as a consequence <strong>of</strong> studying this guide, your essay<br />

c<strong>an</strong>not be very well presented <strong>an</strong>d perfectly referenced. The guide highlights practical ways in which you c<strong>an</strong><br />

produce <strong>an</strong> essay which is well org<strong>an</strong>ized, clearly presented <strong>an</strong>d correctly referenced.<br />

The matter <strong>of</strong> achieving a good writing style <strong>an</strong>d critical engagement with the focus <strong>of</strong> the title is more<br />

complex. That will develop the more you read, the more you write, the more you work at your writing, <strong>an</strong>d the<br />

more you listen to <strong>an</strong>d reflect upon the feedback you get on your writing.<br />

When writing <strong>an</strong>y essay, you should always consult the relev<strong>an</strong>t regulations, <strong>an</strong>y Code <strong>of</strong> Practice applicable<br />

to your programme, your Undergraduate H<strong>an</strong>dbook, <strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong>y specific guid<strong>an</strong>ce provided in relation to the<br />

module in which you are writing your essay. Follow <strong>an</strong>y specific guid<strong>an</strong>ce for the essay in preference to the<br />

general guid<strong>an</strong>ce given in this guide.<br />

ASSESSED ESSAYS<br />

Most <strong>of</strong> you will be familiar with this form <strong>of</strong> assessment. For some, however, it will be new. All essays are<br />

asking you to express your knowledge <strong>an</strong>d underst<strong>an</strong>ding <strong>of</strong> aspects <strong>of</strong> your subject. <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>an</strong> essay is a form<br />

<strong>of</strong> active learning. Your essays will enable your tutors to assess the extent <strong>an</strong>d depth <strong>of</strong> your knowledge,<br />

Seventh edition 2009

2 The basics<br />

including your abilities at legal research, the construction <strong>of</strong> argument, <strong>an</strong>d the effective presentation <strong>of</strong> your<br />

ideas. We will also w<strong>an</strong>t to see that you c<strong>an</strong> write concisely, clearly <strong>an</strong>d accurately.<br />

THE BASICS<br />

The task <strong>of</strong> writing <strong>an</strong> assessed essay involves:<br />

• finding out what is expected <strong>of</strong> you;<br />

• m<strong>an</strong>aging your time;<br />

• underst<strong>an</strong>ding what the essay title requires;<br />

• selecting a title that <strong>of</strong>fers you sufficient scope to demonstrate your knowledge <strong>an</strong>d underst<strong>an</strong>ding ;<br />

• occasionally selecting <strong>an</strong>d developing critical points from lectures <strong>an</strong>d tutorials;<br />

• gathering material for the essay;<br />

• summarizing <strong>an</strong>d reflecting on information from a r<strong>an</strong>ge <strong>of</strong> legal resources;<br />

• putting in your own ideas <strong>an</strong>d conclusions;<br />

• pl<strong>an</strong>ning the structure <strong>of</strong> the essay;<br />

• expressing yourself clearly <strong>an</strong>d succinctly;<br />

• writing <strong>an</strong>d revising a draft, that is, editing the text by checking the relev<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>of</strong> what you have<br />

written <strong>an</strong>d the clarity <strong>of</strong> its content;<br />

• citing authority for your arguments;<br />

• using the required form <strong>of</strong> citation for the authorities that you use.<br />

• pro<strong>of</strong> reading to correct surface errors in grammar, spelling <strong>an</strong>d punctuation;<br />

• avoiding plagiarism.<br />

OUR EXPECTATIONS<br />

Those who are charged with the assessment <strong>of</strong> your work will assume that it is a serious piece <strong>of</strong> work seeking<br />

to <strong>an</strong>swer the question set. In assessing your work, the examiners will be looking for evidence that:<br />

Seventh edition 2009<br />

• you have read the key sources relev<strong>an</strong>t to your title with a questioning mind;<br />

• you have understood the material <strong>an</strong>d arguments contained in your main sources;<br />

• you c<strong>an</strong> relate general theory to specific examples;<br />

• everything in the essay, whether it is based on your reading materials or your own ideas, is relev<strong>an</strong>t to<br />

the title;<br />

• you c<strong>an</strong> construct a reasoned argument, taking account <strong>of</strong> differing points <strong>of</strong> view;<br />

• you c<strong>an</strong> write clearly <strong>an</strong>d use the terminology <strong>of</strong> the subject appropriately;<br />

• you c<strong>an</strong> follow the correct conventions as to the presentation <strong>of</strong> your material;<br />

• you c<strong>an</strong> reference your writing in accord<strong>an</strong>ce with the st<strong>an</strong>dard conventions for the citation <strong>of</strong><br />

authorities, inclusion <strong>of</strong> footnotes, <strong>an</strong>d a bibliography, if required.<br />

REQUIREMENTS<br />

ESSAY QUESTIONS AND PROBLEM QUESTIONS<br />

What you are asked to do may take a number <strong>of</strong> forms. It could be a ‘traditional’ essay asking you to consider<br />

some aspect <strong>of</strong> the law, or it could be a problem testing your ability to apply your knowledge to a factual<br />

situation. Most writing you are asked to do as a law student involves a structured piece <strong>of</strong> writing <strong>an</strong>d the<br />

ordered presentation <strong>of</strong> <strong>an</strong> argument well supported by authority. You will not be asked simply to ‘write all

3<br />

you know about’ a particular topic; yet some students c<strong>an</strong>not resist surveying <strong>an</strong> area <strong>of</strong> law when something<br />

much more discriminating is being requested. M<strong>an</strong>y lecturers report that this remains a common defect found<br />

both in course work <strong>an</strong>d in examination scripts.<br />

WORD LIMITS<br />

All essays will carry a word limit. This may vary. Footnotes are always included in the word limit. <strong>Writing</strong> to a<br />

prescribed length <strong>an</strong>d format involves skills which you will find useful in a wide r<strong>an</strong>ge <strong>of</strong> vocational settings<br />

after you have graduated.<br />

Whatever the word limit, it has not been fixed at r<strong>an</strong>dom, but has been determined as the appropriate space<br />

in which to <strong>an</strong>swer the questions set. You may feel that not enough space has been allowed, but you should<br />

realize that the word limit is imposed to test your ability to express yourself clearly <strong>an</strong>d concisely. By refining<br />

your essay pl<strong>an</strong>, you should be able to gauge the amount <strong>of</strong> detail needed to develop the main points.<br />

Failure to comply with the word limits will result in the imposition <strong>of</strong> penalties in accord<strong>an</strong>ce with the<br />

<strong>University</strong>’s procedures; do check these in your Undergraduate H<strong>an</strong>dbook. You will be required to declare the<br />

number <strong>of</strong> words in your essay, which directs your mind to the required word limit. Word limits are strictly<br />

applied; there is no policy <strong>of</strong> ignoring small over-runs in word limits. It is cheating to declare <strong>an</strong> inaccurate<br />

word count.<br />

SUBMISSION DEADLINES<br />

Always check the deadline for submission, <strong>an</strong>d keep to it. The time <strong>an</strong>d m<strong>an</strong>ner <strong>of</strong> submission are formal<br />

requirements, <strong>an</strong>d must be strictly observed. If the deadline is noon <strong>an</strong>d you submit <strong>an</strong> hour later, you have<br />

missed the deadline. A st<strong>an</strong>dard system <strong>of</strong> penalties operates in the <strong>University</strong> in relation to late submission.<br />

Again familiarize yourself with the rules which c<strong>an</strong> be found in your Undergraduate H<strong>an</strong>dbook. You may be<br />

required to submit both hard copy <strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong> electronic copy <strong>of</strong> your work.<br />

The st<strong>an</strong>dard rule in the law school is that tutors will set out their requirements for submission <strong>of</strong> practice<br />

essays. But there is a much more formal system for submission <strong>of</strong> course work which is for formal assessment,<br />

that is, which provides or contributes to your final mark for a particular module. Such work must be h<strong>an</strong>ded in<br />

personally to the School Office, <strong>an</strong>d you will be given a receipt for it. Do not lose this; it is your pro<strong>of</strong> that you<br />

have submitted the material in time.<br />

If for <strong>an</strong>y reason you wish to submit your work in <strong>an</strong>y form other th<strong>an</strong> personal submission, you must seek<br />

formal permission to do so. Permission will only be given for special reasons. The procedure is set out in your<br />

Undergraduate H<strong>an</strong>dbook.<br />

We do, however, take a sympathetic view <strong>of</strong> problems beyond your control which affect your ability to submit<br />

work by the required deadline. There is a system under which you c<strong>an</strong> ask for <strong>an</strong> extension <strong>of</strong> the deadline for<br />

the submission <strong>of</strong> <strong>an</strong>y work.<br />

For practice essays, you should see your tutor <strong>an</strong>d explain the problem.<br />

For course work, there is a more formal procedure which is explained in your Undergraduate H<strong>an</strong>dbook. But<br />

you should also see your subject tutor <strong>an</strong>d your personal tutor for advice as soon as it becomes clear that you<br />

may have a problem meeting a deadline. Where the reasons for the extension are health-related, some<br />

medical evidence is required to support your application. You may also be asked for some evidence <strong>of</strong> other<br />

personal circumst<strong>an</strong>ces which affect your ability to submit work on time.<br />

4 M<strong>an</strong>aging your time<br />

Retrospective extensions <strong>of</strong> the deadline for submission are only given in the most exceptional circumst<strong>an</strong>ces.<br />

You are normally required to seek the extension in adv<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>of</strong> the deadline for submission or you run the risk<br />

that you will incur the penalties set out above.<br />

Never be casual or cavalier about deadlines; the law school takes them very seriously. Org<strong>an</strong>izing your life to<br />

meet deadlines is part <strong>of</strong> developing a sense <strong>of</strong> responsibility in m<strong>an</strong>aging the m<strong>an</strong>y dem<strong>an</strong>ds on your time.<br />

MANAGING YOUR TIME<br />

Find out the deadline for submission. Then work backwards to determine how much time you will be able to<br />

spend on the assignment. The time you need to write a good essay for assessment should not take you away<br />

from the study <strong>of</strong> other subjects.<br />

Think carefully <strong>an</strong>d constructively about the time <strong>an</strong>d resources you will need to write the essay. This is the<br />

way to avoid p<strong>an</strong>ic <strong>an</strong>d staying up all night at the last minute. It is unlikely that you will do your best work if<br />

you do not org<strong>an</strong>ize yourself <strong>an</strong>d your time.<br />

Spend some time thinking about how <strong>an</strong>d when you work best. Follow this pattern in writing assessed essays.<br />

You might find the following grid useful in identifying your own work style. Ticking the left box me<strong>an</strong>s that you<br />

strongly agree with the proposition set out there. Ticking the right box me<strong>an</strong>s that you identify most with the<br />

proposition set out there. Use the other three boxes to show shades <strong>of</strong> opinion in between the two extremes:<br />

Develop ideas quickly<br />

Needs lots <strong>of</strong> thinking time<br />

Quick to see resources needed<br />

Need time to collect resources<br />

See immediately what to do<br />

Need time to grow into topic<br />

Good at speed reading<br />

Need to read slowly<br />

C<strong>an</strong> work <strong>an</strong>ywhere<br />

Work best in a particular place(s)<br />

Write best in a single session<br />

Write best in several sessions<br />

Need lots <strong>of</strong> breaks<br />

Tend not to need breaks<br />

Work best in the morning<br />

Work best in the evening<br />

Filling in this grid will help your awareness <strong>of</strong> the working methods that best suit you. Think about now much<br />

time you will need for each stage <strong>of</strong> the essay writing process: research, reading, thinking, writing, <strong>an</strong>d<br />

5<br />

UNDERSTANDING THE QUESTION<br />

TOPIC AREA, FOCUS AND INSTRUCTION<br />

Keeping in mind the notions <strong>of</strong> topic area, focus <strong>an</strong>d instruction will help you to <strong>an</strong>swer the question set <strong>an</strong>d to<br />

avoid the inclusion <strong>of</strong> irrelev<strong>an</strong>t material in your response. Attention to topic area, focus <strong>an</strong>d instruction<br />

applies to both the traditional essay question <strong>an</strong>d to problems.<br />

The topic area is the broad area or areas <strong>of</strong> the syllabus you are being invited to consider. The focus <strong>of</strong> the<br />

question will indicate how you are being asked to present your knowledge <strong>of</strong> the topic area or areas. The<br />

instruction will specify what you are to do with your knowledge in applying it to the question set.<br />

This technique <strong>of</strong> breaking down questions into topic area, focus <strong>an</strong>d instruction c<strong>an</strong> be applied both to essays<br />

<strong>an</strong>d to problems. It c<strong>an</strong> assist you in deciding how much space to allocate to the discussion <strong>of</strong> the points raised<br />

in the question.<br />

ESSAY QUESTIONS<br />

"Inquisitorial procedures remove the need for representation in tribunals"<br />

Discuss<br />

The topic area is representation in tribunals, while the focus is on inquisitorial procedures. The instruction is<br />

‘Discuss’. This enables you to look at all sides <strong>of</strong> the argument, since it is a broad instruction. It is not, however,<br />

<strong>an</strong> invitation to write generally about tribunals, or about inquisitorial procedures.<br />

Two variations on this essay title appear below. Think about how your approach would vary if you were writing<br />

<strong>an</strong> essay on one <strong>of</strong> these titles.<br />

Assess the contribution <strong>of</strong> inquisitorial procedures to reducing the need for representation in tribunals.<br />

Argue the case that inquisitorial procedures remove the need for representation in tribunals.<br />

PROBLEM QUESTIONS<br />

You c<strong>an</strong> apply the technique <strong>of</strong> topic area, focus <strong>an</strong>d instruction to problems, though problems are likely to<br />

have more th<strong>an</strong> one topic area.<br />

One night, Jeremy's car is found badly damaged when he returns from taking his new girlfriend, Belinda, out<br />

to dinner. It has been rammed by <strong>an</strong>other vehicle while parked. Jeremy tells the police that his former<br />

girlfriend, Penelope, threatened to smash up his car if he ever went out with Belinda.<br />

The police call at Penelope's house <strong>an</strong>d question her; she denies all knowledge <strong>of</strong> the incident. The police<br />

then arrest Penelope <strong>an</strong>d search her house <strong>an</strong>d garage, where they find a car with damage to the front<br />

bumper. Penelope refuses to say how the damage was caused. She is taken to the police station where the<br />

police tell her that the paint from her car matches flakes <strong>of</strong> paint found on Jeremy's car. This is untrue.<br />

Penelope then makes a statement admitting that she drove into Jeremy's car, but did not intend to cause<br />

much damage. She is charged with criminal damage.<br />

Advise Penelope<br />

(a) on the determination <strong>of</strong> her mode <strong>of</strong> trial, <strong>an</strong>d<br />

(b) on the consequences <strong>of</strong> <strong>an</strong>y unlawful action taken by the police.<br />

The topic areas are mode <strong>of</strong> trial, arrest, search powers, <strong>an</strong>d questioning <strong>of</strong> suspects. The focus is on<br />

determining the mode <strong>of</strong> trial, <strong>an</strong>d the exercise <strong>of</strong> police powers. The instruction is to advise Penelope. The<br />

instruction is specific here; it names two areas to consider <strong>an</strong>d you are advising the person charged, not the<br />

6 Gathering material<br />

victim <strong>of</strong> the <strong>of</strong>fence. Your <strong>an</strong>swer would look very different if you were asked to advise Jeremy on his<br />

remedies.<br />

SELECTING A QUESTION FROM A LIST<br />

You will <strong>of</strong>ten have a choice <strong>of</strong> question to <strong>an</strong>swer. If you look through the choice <strong>of</strong> essay titles carefully,<br />

bearing in mind instruction, topic area <strong>an</strong>d focus, you will avoid the trap <strong>of</strong> focusing on the general area at the<br />

expense <strong>of</strong> what the question is really about <strong>an</strong>d you will be better equipped to select a title you will enjoy<br />

writing on.<br />

The key to selecting a title from a set list is to remember that the titles have been prepared <strong>an</strong>d selected with<br />

great care. The lecturer will have a clear notion <strong>of</strong> the ideas <strong>an</strong>d content you are to cover in responding to the<br />

title. If the lecturer merely w<strong>an</strong>ted you to write all you know about the topic covered, you would be instructed<br />

to do this. That you are never so instructed indicates that the lecturer is looking for more th<strong>an</strong> the<br />

regurgitation <strong>of</strong> your notes.<br />

This is not say that there is a predetermined ‘right’ <strong>an</strong>swer to <strong>an</strong>y question, but it does me<strong>an</strong> that there are<br />

clear limits on the number <strong>of</strong> responses legitimately available.<br />

In selecting a title from a given list, ask the following questions:<br />

1. What is the general area <strong>of</strong> content dem<strong>an</strong>ded by the question?<br />

2. What are the specific concepts on which the topic is focused?<br />

3. What conclusions are to be drawn? You will almost always be asked to make a judgment on a topic.<br />

4. What aspects <strong>of</strong> the subject are being covered?<br />

Having regard to your <strong>an</strong>swers to these questions, choose a title which reflects your own interest <strong>an</strong>d the time<br />

<strong>an</strong>d resources at your disposal to complete it.<br />

GATHERING MATERIAL<br />

PLANNING<br />

If you have <strong>an</strong>alyzed the essay title or problem carefully, you will have a clear idea <strong>of</strong> the relev<strong>an</strong>t topic areas<br />

<strong>an</strong>d be in a position to collect together the material you will need to <strong>an</strong>swer the question effectively. It is good<br />

practice to make a provisional pl<strong>an</strong> before beginning your research, as this provides you with a clear idea <strong>of</strong><br />

questions you need to explore <strong>an</strong>d your information requirements.<br />

The sources you will use will include your lecture notes, materials you prepared for tutorials, your text books,<br />

<strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong>y additional materials on the Blackboard pages for the module. But these materials alone are unlikely to<br />

be all you will need. Most essays or problems will require you to carry out some research in the library or on<br />

the internet. This might be something simple like reading cases or statutes, or one or two key articles or<br />

research reports, to which reference has been made in class. On the other h<strong>an</strong>d, it might require you to seek<br />

out new materials in a new area. Remember to read carefully <strong>an</strong>y specific guid<strong>an</strong>ce which accomp<strong>an</strong>ied the<br />

essay titles.<br />

This guide assumes that you have followed the legal skills instruction you were <strong>of</strong>fered in the first semester <strong>of</strong><br />

your first year. It does not repeat here material covered there.<br />

Part <strong>of</strong> the initial task <strong>of</strong> gathering material for your <strong>an</strong>swer is the identification <strong>of</strong> ideas <strong>an</strong>d issues raised by<br />

the question. This enables you to begin to appreciate how wide (or narrow) the coverage <strong>of</strong> the question is.

7<br />

The thinking <strong>an</strong>d pl<strong>an</strong>ning stage should lead to a clearer focus on the key issues raised by the question, which<br />

will assist you in meeting the word limit while providing <strong>an</strong> effective <strong>an</strong>swer to the question. It should also<br />

enable you to develop confidence in what to leave out. M<strong>an</strong>y students find it difficult to decide what material<br />

is not relev<strong>an</strong>t to the <strong>an</strong>swer.<br />

You may find it helpful at this stage to review your provisional pl<strong>an</strong> <strong>of</strong> the contents <strong>of</strong> your <strong>an</strong>swer. This c<strong>an</strong><br />

help to prevent your getting side-tracked as you get interested in material you read during the research stage.<br />

RESEARCH<br />

At this point it is time to visit the library, in person <strong>an</strong>d online. Research is not a treasure hunt with the prize<br />

being the perfect <strong>an</strong>swer to your question hidden somewhere in the library. This is particularly true if you pl<strong>an</strong><br />

to use the internet to collect information. Your work in the library is the gathering <strong>of</strong> information not available<br />

in the books you own. You are using one <strong>of</strong> the <strong>University</strong>'s major learning resources. Do not spend excessive<br />

amounts <strong>of</strong> time seeking to unearth every conceivable piece <strong>of</strong> written material on the topic areas covered.<br />

Equally do not ignore a principal case, report or article just because it is not on the library shelf when you look<br />

for it.<br />

Remember that you c<strong>an</strong> ask a librari<strong>an</strong> for help if you get into difficulties or c<strong>an</strong>not find something you are<br />

looking for.<br />

A key requirement at this stage is to have a system for org<strong>an</strong>izing the material you collect. An absolute<br />

requirement is to ensure that you have full references for everything you read. This will save you hours later<br />

on if you need to reference the material or find it again. If you make photocopies or print material from the<br />

web, make sure you know exactly where they came from. Develop your own system for org<strong>an</strong>izing material<br />

you collect for your essays. After you have finished each period <strong>of</strong> work in the library, spend a few minutes<br />

org<strong>an</strong>izing your material. Remember that references scribbled on odd bits <strong>of</strong> paper have <strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>noying habit <strong>of</strong><br />

getting lost.<br />

As you read material you will evaluate its usefulness. The material might be directly in point but ten years old.<br />

If timeliness if key to your research (<strong>an</strong>d it <strong>of</strong>ten will be), this will signific<strong>an</strong>tly lower the value <strong>of</strong> this material<br />

for you. The material might be in point <strong>an</strong>d up-to-date, but treated very briefly in one <strong>of</strong> the weekly law<br />

journals. This too will affect its value for you.<br />

WEB-BASED RESOURCES<br />

Two good starting points are the Law Subject Room on the Library website, <strong>an</strong>d the Blackboard pages for the<br />

module.<br />

Determining the quality <strong>of</strong> information is a key part <strong>of</strong> every aspect <strong>of</strong> research, but is particularly import<strong>an</strong>t<br />

when relying on web-based material.<br />

The CARS Checklist is designed for ease <strong>of</strong> learning <strong>an</strong>d use:<br />

• Credibility<br />

• Accuracy<br />

• Reasonableness<br />

• Support<br />

8 Avoiding plagiarism<br />

The CARS Checklist is summarized as follows on www.virtualsalt.com/evalu8it.htm<br />

Credibility<br />

Accuracy<br />

Reasonableness<br />

Support<br />

trustworthy source, author’s credentials, evidence <strong>of</strong> quality<br />

control, known or respected authority, org<strong>an</strong>izational support.<br />

Goal: <strong>an</strong> authoritative source, a source that supplies some good<br />

evidence that allows you to trust it.<br />

up to date, factual, detailed, exact, comprehensive, audience<br />

<strong>an</strong>d purpose reflect intentions <strong>of</strong> completeness <strong>an</strong>d accuracy.<br />

Goal: a source that is correct today (not yesterday), a source<br />

that gives the whole truth.<br />

fair, bal<strong>an</strong>ced, objective, reasoned, no conflict <strong>of</strong> interest,<br />

absence <strong>of</strong> fallacies or sl<strong>an</strong>ted tone. Goal: a source that engages<br />

the subject thoughtfully <strong>an</strong>d reasonably, concerned with the<br />

truth.<br />

listed sources, contact information, available corroboration,<br />

claims supported, documentation supplied. Goal: a source that<br />

provides convincing evidence for the claims made, a source you<br />

c<strong>an</strong> tri<strong>an</strong>gulate (find at least two other sources that support it).<br />

NOTE-TAKING<br />

Note-taking still has a role to play in the age <strong>of</strong> the photocopier <strong>an</strong>d the internet. Even if you photocopy or<br />

download lots <strong>of</strong> material <strong>an</strong>d highlight it, you should still be making notes <strong>of</strong> your thoughts as you read<br />

through the material. Photocopying <strong>an</strong>d downloading should not be thought <strong>of</strong> as substitutes for reading <strong>an</strong>d<br />

evaluation.<br />

Precision <strong>an</strong>d relev<strong>an</strong>ce are the core qualities <strong>of</strong> good notes. Adopt a system which will enable you to know<br />

whether your note is a précis <strong>of</strong> the whole piece, a paraphrase <strong>of</strong> part <strong>of</strong> it, or a direct quote. If you c<strong>an</strong>not<br />

identify which when you come to use the material later, you may inadvertently plagiarize the material. This is<br />

particularly true if you take notes directly onto the computer, <strong>an</strong>d cut <strong>an</strong>d paste material from your notes into<br />

your essay. It is good practice to write directly quoted material in red (together with a page reference)—or to<br />

type it in italics, or in some other readily identifiable way, on the computer—so that it c<strong>an</strong> easily be identified<br />

as quoted material at a later stage <strong>of</strong> your work.<br />

How do you choose between a paraphrase <strong>an</strong>d a quotation when you come across a comment directly in point<br />

which you are pretty sure you will include in your essay? A paraphrase is relev<strong>an</strong>t where it is the content <strong>of</strong> the<br />

material which is import<strong>an</strong>t, while a quotation is appropriate where the mode <strong>of</strong> expression <strong>of</strong> the idea<br />

captures it in a particularly effective or characteristic way. In law, the quotation from a reported case also has<br />

a particular role to play as the statement <strong>of</strong> authority for a legal proposition.<br />

AVOIDING PLAGIARISM<br />

Plagiarism is the presentation <strong>of</strong> the thoughts or writings <strong>of</strong> others as your own. It is a form <strong>of</strong> cheating. Please<br />

read the <strong>University</strong>'s statement on academic dishonesty in the Undergraduate Regulations, <strong>an</strong>d the section on<br />

plagiarism in the Undergraduate H<strong>an</strong>dbook.<br />

Collaborative work c<strong>an</strong> also lead to plagiarism. While we encourage collaboration in some <strong>of</strong> your work (for<br />

example, in preparation for tutorials), when we come to assessment, we w<strong>an</strong>t to assess your work alone.<br />

Unless you have been expressly assigned a group project, you must not collaborate with others in the

9<br />

preparation <strong>of</strong> your assessed essays. In addition, you must not use <strong>an</strong>other student’s notes, essay or essay<br />

drafts as the basis for your own work. You must never cut <strong>an</strong>d paste sections <strong>of</strong> <strong>an</strong>other student’s material as<br />

part <strong>of</strong> your essay. To do <strong>an</strong>y <strong>of</strong> these things constitutes plagiarism just as much as if you had copied the<br />

material from a book or some internet resource.<br />

Whenever you draw on the ideas <strong>of</strong> others, you must say so. The common form <strong>of</strong> acknowledgement is the<br />

citation <strong>of</strong> the source in a footnote.<br />

<strong>Assessed</strong> work which contains plagiarized material will be severely penalized. Serious cases <strong>of</strong> plagiarism<br />

involve acts <strong>of</strong> dishonesty. The pr<strong>of</strong>essional bodies may take the view that a person guilty <strong>of</strong> plagiarism is not a<br />

suitable person to join the legal pr<strong>of</strong>ession.<br />

Everyone knows that it is cheating to copy someone else's work whether it has been published or not. So<br />

copying a fellow student's work is just as much plagiarism as copying out <strong>of</strong> a published book.<br />

Rather more complex is the extent to which you c<strong>an</strong> rely on the work <strong>of</strong> others. The following guidelines may<br />

help you to develop a proper sense <strong>of</strong> when you need to acknowledge a source:<br />

1. Part <strong>of</strong> the task <strong>of</strong> research is to collect together a r<strong>an</strong>ge <strong>of</strong> ideas <strong>an</strong>d to take account <strong>of</strong> them in<br />

forming your own ideas. You should include all the key books <strong>an</strong>d articles you have used to collect<br />

that r<strong>an</strong>ge <strong>of</strong> ideas in your bibliography (if one is required), regardless <strong>of</strong> whether you have referred<br />

to them expressly in your text.<br />

2. You must include a reference to specific ideas or conclusions <strong>of</strong> others on which you rely by the use <strong>of</strong><br />

<strong>an</strong> attributed quotation or the reporting <strong>of</strong> the idea or conclusion in a reference like a footnote.<br />

3. Do not assume that, because a text has not been referred to by your tutors, they are unaware <strong>of</strong> its<br />

contents. It is generally easy for tutors to spot material which is not your own, either because they are<br />

familiar with the source or because your writing style suddenly ch<strong>an</strong>ges. Some <strong>of</strong> your assessed work<br />

will be submitted to a plagiarism detection service.<br />

Plagiarism c<strong>an</strong> take m<strong>an</strong>y forms. All forms <strong>of</strong> plagiarism are taken seriously. The law school has prepared <strong>an</strong><br />

online tutorial on how to avoid plagiarism, <strong>an</strong>d all those using this guide are advised in the strongest terms to<br />

complete that tutorial.<br />

The online tutorial c<strong>an</strong> be found at:<br />

connect.le.ac.uk/plagiarismlaw/<br />

If you complete this tutorial, you should probably not have to worry that your writing might contain material<br />

which has been plagiarized, since you will know what plagiarism is <strong>an</strong>d how to avoid it. If you are still uncertain<br />

about what constitutes plagiarism after completing this tutorial, see your personal tutor or your subject tutor.<br />

YOUR IDEAS<br />

You may find that putting in your own ideas <strong>an</strong>d conclusions is difficult. After all you are studying the subject<br />

for the first time <strong>an</strong>d the more you read, the more it seems that all the ideas have been explored. However,<br />

m<strong>an</strong>y <strong>of</strong> your essay titles <strong>an</strong>d problems will have been set in areas where there is more th<strong>an</strong> one view. You are<br />

expected to collect the evidence, use it, <strong>an</strong>d form your own conclusions. Your tutors are not expecting you to<br />

have startling new insights into the subject, but they do w<strong>an</strong>t you to be clear for yourselves <strong>an</strong>d for them what<br />

you have understood about the topic area. The emphasis in higher education is on active learning, which<br />

me<strong>an</strong>s that you must be deeply involved in your own legal education <strong>an</strong>d not simply be good at getting down a<br />

set <strong>of</strong> lecture notes.<br />

10 Pl<strong>an</strong>ning your <strong>an</strong>swer<br />

Your own ideas should be rooted in the literature <strong>of</strong> the subject. The bizarre irrelev<strong>an</strong>ce will be seen as just<br />

that <strong>an</strong>d not as a brilli<strong>an</strong>t insight. Your conclusions must follow from the material you have used <strong>an</strong>d be related<br />

to it.<br />

However, the hallmark <strong>of</strong> a distinction level essay c<strong>an</strong> sometimes be found in the way in which you have<br />

related the focus <strong>of</strong> the essay question to other topic areas, sometimes in other areas <strong>of</strong> law being studied.<br />

Such linkages may well adv<strong>an</strong>ce the argument in <strong>an</strong> interesting way <strong>an</strong>d demonstrate a higher level <strong>of</strong> literacy<br />

in the l<strong>an</strong>guage <strong>of</strong> the law.<br />

One way <strong>of</strong> developing your skills in independent thinking is critical reading <strong>an</strong>d critical writing. An appendix to<br />

this guide reprints the Student Learning Centre’s advice on critical writing, which m<strong>an</strong>y students have found<br />

helpful.<br />

PLANNING YOUR ANSWER<br />

You will continue to develop the structure <strong>of</strong> your ideas as you prepare a draft <strong>of</strong> your <strong>an</strong>swer. Where you<br />

start will be a matter for you, but you need not start on the first page <strong>of</strong> the first section. You may prefer to<br />

write a section setting out the background to the problem you are exploring rather th<strong>an</strong> the introduction to<br />

the essay. Do remember the provisional pl<strong>an</strong> you made at <strong>an</strong> earlier stage. If you find that your writing does<br />

not fit the pl<strong>an</strong>, revise it.<br />

Remember that your purpose is to present reasoned argument based on authority. When you write, you will<br />

discover some difficult areas; you will identify areas that you think will need re-drafting; you will write too<br />

much on some areas <strong>an</strong>d need to prune the material; <strong>an</strong>d you will identify gaps to be filled.<br />

If you have trouble getting started, begin with a section that is more straightforward <strong>an</strong>d you will soon find the<br />

flow <strong>of</strong> words is there. Do not put <strong>of</strong>f the task <strong>of</strong> getting words onto the page. It is easier to revise a text th<strong>an</strong><br />

to start from scratch. But do not fall into the trap <strong>of</strong> regarding words on the page as unch<strong>an</strong>geable.<br />

Your essay will be broken into sections. You should pl<strong>an</strong> a system <strong>of</strong> headings. You will not need more th<strong>an</strong><br />

two levels <strong>of</strong> heading for <strong>an</strong> assessed essay. Be consistent in the use <strong>of</strong> headings <strong>an</strong>d use them as a guide to<br />

the reader. Headings are signposts which c<strong>an</strong> indicate to the reader how the argument is developing. In<br />

<strong>an</strong>swers to problem questions, they signal very effectively that you are moving from one aspect <strong>of</strong> the<br />

problem to <strong>an</strong>other.<br />

Sometimes it is helpful to produce <strong>an</strong> outline, that is, just the list <strong>of</strong> main headings <strong>an</strong>d sub-headings. Most<br />

word processors will generate <strong>an</strong> outline automatically for the headings you use if they are defined as a style in<br />

the document template. The outline shows the shape <strong>an</strong>d structure <strong>of</strong> your paper <strong>an</strong>d c<strong>an</strong> illustrate quite<br />

dramatically whether too much attention is being given to one aspect <strong>of</strong> the question at the expense <strong>of</strong> other<br />

aspects.<br />

EXPRESSING YOURSELF CLEARLY<br />

SOME GENERAL PRINCIPLES<br />

When seeing students to <strong>of</strong>fer feedback, lecturers are frequently told, ‘I me<strong>an</strong>t to say that’. But your lecturers<br />

c<strong>an</strong> only mark what you have said, <strong>an</strong>d c<strong>an</strong>not know what you me<strong>an</strong>t to say. Your ability to express yourself<br />

concisely, clearly <strong>an</strong>d accurately is one <strong>of</strong> the skills we are testing. Always try to write simply <strong>an</strong>d clearly.<br />

Accept that you c<strong>an</strong> always improve the clarity <strong>of</strong> your writing.

11<br />

If you are not sure about the use <strong>of</strong> certain st<strong>an</strong>dard grammatical forms, refer to a useful set <strong>of</strong> short<br />

information sheets produced by the Student Learning Centre: www.le.ac.uk/slc/<br />

Keep one idea to each sentence, <strong>an</strong>d make sure your sentences are not too long. The Plain English Campaign<br />

has lots <strong>of</strong> useful advice on keeping your writing crystal clear: www.plainenglish.co.uk/<br />

It is vital to pro<strong>of</strong> read your essay, <strong>an</strong>d it c<strong>an</strong> be helpful to ask a friend to read through your final draft for<br />

grammar, spelling <strong>an</strong>d punctuation inaccuracies.<br />

There is considerable focus at all levels <strong>of</strong> education on what are called core tr<strong>an</strong>sferable skills. These are those<br />

skills which c<strong>an</strong> be learned in one context <strong>an</strong>d readily be tr<strong>an</strong>sferred to <strong>an</strong>other context. The ability to express<br />

yourself clearly <strong>an</strong>d succinctly in writing is a good example <strong>of</strong> such a skill. You will already have writing skills,<br />

but they c<strong>an</strong> almost certainly be improved <strong>an</strong>d developed. A frequent regret expressed by lecturers is that<br />

students could improve their perform<strong>an</strong>ce without needing to know more if only they would express<br />

themselves more clearly. The message is, therefore, to pay attention to the clarity <strong>of</strong> your writing. This is one<br />

<strong>of</strong> the skills being measured in this form <strong>of</strong> assessment.<br />

Here are some writing hints, which you may find obvious, but lecturers frequently complain that they are not<br />

observed:<br />

• Write in complete sentences.<br />

• Do not write very long sentences; the me<strong>an</strong>ing c<strong>an</strong> get obscured. A good guide is not to exceed twenty<br />

words in <strong>an</strong>y sentence.<br />

• Use punctuation effectively; punctuation consists <strong>of</strong> more th<strong>an</strong> full stops <strong>an</strong>d commas!<br />

• Use paragraphs effectively; a new paragraph signals a new idea or area <strong>of</strong> discussion.<br />

• Pay due attention to spelling <strong>an</strong>d grammar.<br />

The usual requirement is for assessed essays to be word processed. You are expected to develop these skills if<br />

you do not already have them. Practice essays might, however, be submitted in h<strong>an</strong>d-written form; check your<br />

tutor’s requirements. If you c<strong>an</strong> h<strong>an</strong>d in your essay in h<strong>an</strong>d-written form, make sure that your h<strong>an</strong>dwriting is<br />

neat <strong>an</strong>d legible. Lecturers are hum<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>d are influenced by the legibility <strong>an</strong>d readability <strong>of</strong> your work. How<br />

you present your work sends out strong signals about how much you value your own work.<br />

USING GENDER NEUTRAL LANGUAGE<br />

A recognized feature <strong>of</strong> good modern writing is the use <strong>of</strong> gender neutral l<strong>an</strong>guage. This me<strong>an</strong>s avoiding the<br />

use <strong>of</strong> male terms when the person about whom you are writing could just as easily be a wom<strong>an</strong> as a m<strong>an</strong>.<br />

The use <strong>of</strong> ‘he’ when referring to judges, lawyers, students or <strong>an</strong>y group <strong>of</strong> people is seen as re-inforcing<br />

gender stereo-typing <strong>of</strong> certain groups. The old convention that the term ‘he’ also included ‘she’ is no longer<br />

regarded as acceptable in m<strong>an</strong>y quarters.<br />

The use <strong>of</strong> a plural rather th<strong>an</strong> a singular will <strong>of</strong>ten enable the gender neutral personal pronoun ‘their’ to be<br />

used. So:<br />

Lawyers are products <strong>of</strong> their background.<br />

is preferable to<br />

A lawyer is the product <strong>of</strong> his background.<br />

12 Expressing yourself clearly<br />

But it is increasingly common (<strong>an</strong>d The Oxford <strong>Guide</strong> to the English L<strong>an</strong>guage reports the usage as going back<br />

five centuries!) for the plural pronoun to be used since English has no singular pronoun to denote common<br />

gender. This c<strong>an</strong> produce ineleg<strong>an</strong>t sentences. So, some would regard<br />

A lawyer is the product <strong>of</strong> their background<br />

as odd. In this case using ‘lawyers’ in the plural avoids the ineleg<strong>an</strong>t l<strong>an</strong>guage. A further alternative would be<br />

A lawyer is the product <strong>of</strong> his or her background.<br />

This usage is unwieldy if repeated too <strong>of</strong>ten, but its occasional use c<strong>an</strong> be effective in showing the reader that<br />

the writer is aware that lawyers are just as likely to be women as men.<br />

Obviously, there will be occasions where the use <strong>of</strong> the singular pronoun is appropriate:<br />

Everyone in the women's movement has had her own experience <strong>of</strong> sexual discrimination.<br />

When creating examples to illustrate your argument, think whether all your examples from a particular group<br />

are men or women. A good piece <strong>of</strong> writing will reflect a growing concern with gender equality at all levels <strong>of</strong><br />

our lives.<br />

SOME GENERAL PRACTICES IN WRITING<br />

The following guid<strong>an</strong>ce picks up one or two areas where there are general writing conventions.<br />

Latin or foreign words or phrases, whether abbreviated or not, should usually appear in italics, unless the<br />

phrase has passed into common English usage:<br />

mens rea<br />

sine qua non<br />

qu<strong>an</strong>tum meruit<br />

prima facie<br />

ultra vires<br />

raison d’être<br />

Much helpful guid<strong>an</strong>ce on spelling <strong>an</strong>d whether something should appear in italics c<strong>an</strong> be found in The Oxford<br />

Dictionary for Writers <strong>an</strong>d Editors, Clarendon Press, 1981. [REF 808.0203 OXF]<br />

You may also find Fowler's Modern English Usage [REF 428.003 FOW] or Oxford English: A <strong>Guide</strong> to the<br />

L<strong>an</strong>guage [REF 428 DEA] helpful reference material to clear up <strong>an</strong>y confusion you might have about the proper<br />

use or spelling <strong>of</strong> particular words used in particular contexts. One relev<strong>an</strong>t example is that the word<br />

‘judgment’ is spelled without a middle ‘e’ when used in legal contexts, whereas in other contexts it is spelled<br />

‘judgement’.<br />

Names <strong>of</strong> foreign courts should appear in rom<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>d not in italics:<br />

Conseil d'Etat<br />

Bundesverfassungsgericht

13<br />

Hoge Raad<br />

Capital letters should only be used where strictly necessary. Capital letters should not be used for court (unless<br />

referring to a particular court) judge (unless used as part <strong>of</strong> a title) or state (unless referring to a particular<br />

state, for example, the State <strong>of</strong> Victoria).<br />

Numbers up to 20 should be written in words in the text. The numbers 20 <strong>an</strong>d above should appear as<br />

numbers; so<br />

three<br />

seventeen<br />

24<br />

Percentages should be written in numbers <strong>an</strong>d the words ‘per cent’ should be used rather th<strong>an</strong> the symbol %:<br />

75 per cent.<br />

WRITING AND REVISING A DRAFT<br />

THE FIRST DRAFT IS FOR YOU<br />

We have already touched on a number <strong>of</strong> aspects <strong>of</strong> preparing the draft <strong>of</strong> your essay. The first draft is for you,<br />

not for the assessor. So it need not be perfectly polished or perfectly expressed. But it should be in the form <strong>of</strong><br />

the final text. This me<strong>an</strong>s that it should include <strong>an</strong> introduction <strong>an</strong>d conclusion, <strong>an</strong>d include all the points you<br />

expect to make in the order you expect to make them.<br />

THE INTRODUCTION<br />

There should always be some form <strong>of</strong> introduction. The introduction does not need to be long; a short sharp<br />

introduction c<strong>an</strong> be a most effective start to <strong>an</strong> essay. The purpose <strong>of</strong> the introduction is to show the reader<br />

what you underst<strong>an</strong>d to be the issues raised by the question <strong>an</strong>d how you propose to tackle them. It is also the<br />

place to define <strong>an</strong>y key terms for the essay, or to state <strong>an</strong>y assumptions you are making in responding to the<br />

question set.<br />

In the introduction, you should avoid repeating the question. Nor is this the place to develop your argument. It<br />

may, however, be appropriate to spell out the implications <strong>of</strong> the question in a little more detail in order that<br />

you c<strong>an</strong> pursue your argument within a well ordered framework. Whether it is the place to give notice <strong>of</strong> your<br />

conclusion is much more contentious. Some people argue that the introduction is no place to state your<br />

conclusion. Others say that a statement like:<br />

I shall be arguing in this essay that Pr<strong>of</strong>essor Lapping’s thesis on privity <strong>of</strong> contract is fundamentally flawed.<br />

is extremely powerful <strong>an</strong>d makes the reader sit up <strong>an</strong>d take notice. Even if this technique is used, you should<br />

note that the introduction is not the place to say why the thesis is flawed.<br />

THE BODY OF THE ANSWER<br />

The body <strong>of</strong> your <strong>an</strong>swer contains the development <strong>of</strong> the argument <strong>an</strong>d all the essential information to<br />

sustain your conclusion.<br />

14 <strong>Writing</strong> <strong>an</strong>d revising a draft<br />

The body <strong>of</strong> the <strong>an</strong>swer will be divided into a number <strong>of</strong> sections. Think about what these sections should be<br />

<strong>an</strong>d begin each section with <strong>an</strong> indication <strong>of</strong> its purpose. The skilful use <strong>of</strong> headings c<strong>an</strong> provide very helpful<br />

signposts to the reader here. Be consistent in the use <strong>of</strong> headings; you are unlikely to need more th<strong>an</strong> two<br />

levels <strong>of</strong> heading for <strong>an</strong> assessed essay. Use examples to illustrate the points you are making <strong>an</strong>d include your<br />

own comment to explain the signific<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>of</strong> those points.<br />

Quotations c<strong>an</strong> be useful, but <strong>an</strong> essay which is merely a collection <strong>of</strong> quotations will not score highly. The key<br />

is to be selective in the use <strong>of</strong> quoted material <strong>an</strong>d to weave it carefully into the fabric <strong>of</strong> your <strong>an</strong>swer. Avoid<br />

writing <strong>an</strong> essay which is a ‘quotation s<strong>an</strong>dwich’, that is, a few lines <strong>of</strong> text followed by a quotation<br />

throughout.<br />

You should take care not to jump around among the issues raised by the question. If you find that you are<br />

doing this, take <strong>an</strong>other look at the pl<strong>an</strong> <strong>an</strong>d see whether there is <strong>an</strong> adjustment to it that c<strong>an</strong> be made to<br />

avoid this.<br />

One <strong>of</strong> the most import<strong>an</strong>t things to remember is that all statements must be supported by evidence or<br />

authority. This is <strong>an</strong> absolute must in legal writing.<br />

Finally, you should check that the content <strong>of</strong> the main sections <strong>of</strong> your <strong>an</strong>swer reflects what you have<br />

indicated you would cover in the introduction. If it does not, one or the other (or possibly both) need to be<br />

revised.<br />

THE CONCLUSION<br />

The conclusion draws together the threads <strong>of</strong> your argument. It does not repeat those arguments. Nor does it<br />

repeat the introduction. The conclusion should focus on the question set <strong>an</strong>d state how you have <strong>an</strong>swered<br />

the question. There should be no new arguments in the conclusion.<br />

If you have undertaken a problem question, then the conclusion c<strong>an</strong> summarize your conclusions on the r<strong>an</strong>ge<br />

<strong>of</strong> issues which has been raised.<br />

REVISING THE FIRST DRAFT<br />

You should allow yourself time to review your draft. Do not leave everything to the last minute. Reviewing<br />

material you have written is best done after a break <strong>of</strong> a couple <strong>of</strong> days. If you review the draft immediately,<br />

you will have in mind what you intended to say. If you review it a couple <strong>of</strong> days later, you will be much more<br />

objective in evaluating whether the text says what you w<strong>an</strong>t it to. The assessor does not have the benefit <strong>of</strong><br />

being able to ask you what you me<strong>an</strong>. So the text must be clear <strong>an</strong>d speak for itself.<br />

Once you have completed your first draft, you c<strong>an</strong> engage in self-criticism. Look at what you have written. Is it<br />

clear in its message? At this stage you should be able to produce your main argument in summary form, say, in<br />

100-150 words. Try this. C<strong>an</strong> you do it? If so, does the essay lead in this direction? Are some sections too<br />

detailed compared with others? Are there gaps in the reasoning?<br />

You will be reviewing both the content <strong>an</strong>d the style <strong>an</strong>d presentation. If a friend is willing to read through the<br />

draft, they c<strong>an</strong> tell you whether the sense is clear. Friends obviously c<strong>an</strong>not assist you with the subst<strong>an</strong>ce <strong>of</strong><br />

your work, but advice on the clarity <strong>of</strong> the writing <strong>an</strong>d argument c<strong>an</strong> be <strong>an</strong> invaluable part <strong>of</strong> the process <strong>of</strong><br />

self-assessment.<br />

The following self-evaluation questions about your text will draw your attention to import<strong>an</strong>t aspects <strong>of</strong> your<br />

15<br />

• Is the argument clear?<br />

• Are the main points sufficiently developed <strong>an</strong>d the examples appropriate?<br />

• Is there appropriate reference to authority to support the essay’s propositions?<br />

• Are the introduction <strong>an</strong>d conclusion effective?<br />

• Do you think it is a good piece <strong>of</strong> writing?<br />

THE BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

You will <strong>of</strong>ten be asked to produce a bibliography at the end <strong>of</strong> your written work. If so, this will be assessed,<br />

<strong>an</strong>d so treat the preparation <strong>of</strong> your bibliography seriously. The bibliography lists the resources you have used<br />

to prepare your essay. It appears at the end <strong>of</strong> the text. It is good practice to list separately (1) primary sources<br />

divided into statutory material <strong>an</strong>d cases, (2) books <strong>an</strong>d chapters in books, <strong>an</strong>d (3) articles from journals.<br />

Material in your bibliography should be listed in alphabetical order, unless otherwise directed.<br />

For most assessed essays, the bibliography will not need to be elaborate. There will be three relatively short<br />

sections. The first should give the proper reference to statutory material <strong>an</strong>d cases on which you have relied.<br />

The second should list all the books, chapters in books <strong>of</strong> essays, <strong>an</strong>d research <strong>an</strong>d policy reports used. The<br />

third should list all the articles from journals used. All three sets <strong>of</strong> materials must be cited in accord<strong>an</strong>ce with<br />

the system the law school has adopted on which guid<strong>an</strong>ce appears below.<br />

USING YOUR TUTOR EFFECTIVELY<br />

For much <strong>of</strong> the work covered by this guide, you will not have a supervisor, <strong>an</strong>d your tutor is not expected to<br />

spend time helping you with your work. Once you have been given general guid<strong>an</strong>ce on the task assigned, you<br />

will be expected to get on with it on your own. Part <strong>of</strong> what we are testing is your abilities in this regard.<br />

If you are able to seek advice from your subject tutor, use this session wisely. The role <strong>of</strong> the tutor is not to redraft<br />

your essay for you so that it will achieve a higher mark, or to tell you what the <strong>an</strong>swer to the question is.<br />

The tutor’s role is to sharpen your own ability to assess whether the essay shows strengths <strong>an</strong>d where further<br />

work is needed. The more you are willing to engage in discussion about your ideas, the more helpful you will<br />

find <strong>an</strong>y feedback you receive at this stage.<br />

Even where (as will be common) the essay is to be completed without supervision or guid<strong>an</strong>ce, remember that<br />

you c<strong>an</strong> consult your subject tutor if you find that you are in difficulties. If you are having trouble with the<br />

assignment, then the sooner you consult, the sooner you will be able to address the difficulty. Delay at this<br />

stage is not a sensible choice. Try <strong>an</strong>d specify what your precise difficulties are in the form <strong>of</strong> questions on<br />

which you c<strong>an</strong> focus with your subject tutor.<br />

Remember also that, if your difficulties relate to more general problems you are experiencing, you c<strong>an</strong> consult<br />

your personal tutor for general advice in coping with your studies.<br />

WORD PROCESSING<br />

<strong>Assessed</strong> essays should be word processed. There are plenty <strong>of</strong> word processing facilities available for student<br />

use <strong>an</strong>d learning to use them is a valuable skill in itself.<br />

The law school expects you to be a competent word processor. Do take adv<strong>an</strong>tage <strong>of</strong> the training we <strong>of</strong>fer you<br />

if you do not have this skill. The law school has a computer <strong>of</strong>ficer, who c<strong>an</strong> help students experiencing<br />

difficulties in using the facilities available on the campus network.<br />

16 Specific requirements for particular essays<br />

Always have a backup in case things go wrong when using the computer. You should also save your current<br />

work on the computer you are using at least every ten minutes, so that you will always be able to go back to a<br />

very recent version if things go wrong with the version you are working on. You c<strong>an</strong> set up most word<br />

processing packages to do this automatically. Keep your USB stick safe if that is where you keep your backup.<br />

Use <strong>of</strong> computing facilities available to you on campus is the safest me<strong>an</strong>s <strong>of</strong> preparing your essay. If you are<br />

using a machine <strong>of</strong> your own, or making use <strong>of</strong> one belonging to a friend, make sure you know what operating<br />

system <strong>an</strong>d word processing s<strong>of</strong>tware it uses <strong>an</strong>d whether it is compatible with the <strong>University</strong> system when<br />

you w<strong>an</strong>t to make a printout <strong>of</strong> your essay for submission.<br />

SPECIFIC REQUIREMENTS FOR PARTICULAR ESSAYS<br />

Always check the instructions you have been given in the module for which you are writing your essay. Follow<br />

the requirements set out there, even if they conflict with the general guid<strong>an</strong>ce given in this guide.<br />

All course work is assessed without our knowing who you are. You will be asked to include only your student<br />

<strong>an</strong>onymity number on the material which will go to the tutor. Take care to record this accurately, otherwise<br />

we will not know who you are. Some students are too casual in recording this number, which requires<br />

detective work on the part <strong>of</strong> academic <strong>an</strong>d support staff to identify who you are.<br />

When you h<strong>an</strong>d in course work, you are required to complete a st<strong>an</strong>dard form declaration. Your work will not<br />

be accepted by the School Office unless accomp<strong>an</strong>ied by such a declaration. You will be given a receipt. Keep it<br />

safe; it is your pro<strong>of</strong> that you have submitted your work. Remember that you may be required to submit both<br />

hard copy <strong>an</strong>d <strong>an</strong> electronic version <strong>of</strong> your work.<br />

FEEDBACK ON YOUR WORK<br />

You will get some brief feedback on your essays. Read through your essay <strong>an</strong>d reflect on the feedback. This<br />

way, you will develop your skills <strong>an</strong>d learn from experience.<br />

If you do not underst<strong>an</strong>d something indicated in the feedback, do consult your subject tutor or personal tutor.<br />

However, you will get most out <strong>of</strong> this consultation if you are willing to listen. No one reacts well to a<br />

confrontational meeting in which you dem<strong>an</strong>d that your essay be remarked. Most lecturers are happy to help<br />