War Photographer Summary & Analysis by Carol Ann Duffy

- Line-by-Line Explanation & Analysis

- Poetic Devices

- Vocabulary & References

- Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme

- Line-by-Line Explanations

"War Photographer" is a poem by Scottish writer Carol Ann Duffy, the United Kingdom's poet laureate from 2009 to 2019. Originally published in 1985, "War Photographer" depicts the experiences of a photographer who returns home to England to develop the hundreds of photos he has taken in an unspecified war zone. The photographer wrestles with the trauma of what he has seen and his bitterness that the people who view his images are unable to empathize fully with the victims of catastrophic violence abroad. The poem references a number of major historical air strikes and clearly draws imagery from Nick Ut's famous Vietnam War photograph of children fleeing the devastation of a napalm bomb.

- Read the full text of “War Photographer”

The Full Text of “War Photographer”

“war photographer” summary, “war photographer” themes.

Apathy, Empathy, and the Horrors of War

Lines 13-15, lines 15-18.

- Lines 19-24

Trauma and Memory

Lines 11-12.

- Lines 13-18

The Ethics of Documenting War

Line-by-line explanation & analysis of “war photographer”.

In his dark ... ... in ordered rows.

The only light ... ... intone a Mass.

Belfast. Beirut. Phnom ... flesh is grass.

He has a ... ... seem to now.

Rural England. Home ... ... weather can dispel,

to fields which ... ... a nightmare heat.

Something is happening. ... ... a half-formed ghost.

He remembers the ... ... into foreign dust.

Lines 19-21

A hundred agonies ... ... for Sunday’s supplement.

Lines 21-22

The reader’s eyeballs ... ... and pre-lunch beers.

Lines 23-24

From the aeroplane ... ... do not care.

“War Photographer” Symbols

Photographs

- Line 2: “with spools of suffering set out in ordered rows”

- Line 7: “Solutions slop in trays”

- Lines 13-15: “A stranger’s features / faintly start to twist before his eyes, / a half-formed ghost”

- Line 19: “A hundred agonies in black and white”

“War Photographer” Poetic Devices & Figurative Language

Alliteration.

- Line 2: “s,” “s,” “s”

- Line 4: “th,” “th”

- Line 5: “pr,” “pr”

- Line 6: “B,” “B,” “P,” “P”

- Line 7: “H,” “h,” “S,” “s”

- Line 8: “h,” “h,” “th”

- Line 9: “th”

- Line 13: “S,” “s,” “t,” “f”

- Line 14: “f,” “s,” “t,” “t,” “t”

- Line 16: “h,” “h”

- Line 17: “w,” “w,” “w”

- Line 20: “s”

- Line 21: “S,” “s”

- Line 22: “b,” “b,” “b”

- Line 6: “Belfast. Beirut. Phnom Penh. All flesh is grass.”

- Lines 11-12: “to fields which don’t explode beneath the feet / of running children in a nightmare heat.”

- Line 6: “All flesh is grass.”

- Line 1: “I,” “i”

- Line 2: “o”

- Line 3: “o,” “o”

- Line 4: “ou,” “e,” “u,” “e”

- Line 5: “ie,” “a”

- Line 6: “e,” “a,” “e,” “e,” “a”

- Line 8: “i,” “i,” “i,” “e,” “e”

- Line 10: “i,” “i,” “ea,” “e”

- Line 11: “ie,” “o,” “o,” “ea,” “ee”

- Line 13: “i,” “i,” “i,” “a,” “e,” “u”

- Line 14: “ai”

- Line 15: “ie”

- Line 16: “i”

- Line 17: “o,” “o,” “a,” “o,” “o,” “u”

- Line 18: “oo,” “u”

- Line 19: “a,” “a,” “a”

- Line 20: “i,” “i,” “i,” “i,” “i,” “i”

- Line 21: “u,” “u,” “i”

- Line 22: “i,” “ea,” “ee,” “e,” “ee”

- Line 23: “a,” “a,” “a,” “e”

- Line 24: “i,” “i”

- Line 6: “Belfast. Beirut. Phnom Penh. All”

- Line 7: “do. Solutions”

- Line 8: “hands, which”

- Line 9: “now. Rural England. Home”

- Line 13: “happening. A”

- Line 15: “ghost. He”

- Line 16: “wife, how”

- Line 21: “supplement. The”

- Line 1: “r,” “r,” “n,” “ll,” “l,” “n”

- Line 2: “s,” “l,” “s,” “s,” “t,” “t,” “r,” “d,” “r,” “d,” “r”

- Line 3: “l,” “l,” “l,” “l”

- Line 5: “pr,” “pr,” “p,” “r,” “t,” “t,” “ss”

- Line 6: “B,” “s,” “t,” “B,” “t,” “P,” “n,” “P,” “n,” “ll,” “l”

- Line 7: “H,” “h,” “S,” “l,” “sl”

- Line 8: “h,” “s,” “h,” “s,” “t,” “t,” “th”

- Line 9: “th,” “R,” “r,” “g,” “g,” “n”

- Line 10: “n,” “p,” “n,” “w,” “p,” “l,” “w,” “d,” “p,” “l”

- Line 11: “l,” “d,” “d,” “pl,” “d,” “th,” “th”

- Line 12: “n,” “n”

- Line 13: “S,” “str,” “r,” “s,” “t,” “r,” “s”

- Line 14: “f,” “t,” “st,” “t,” “t,” “t,” “st”

- Line 15: “f,” “f”

- Line 16: “w,” “h,” “w,” “h”

- Line 17: “w,” “w,” “d,” “d,” “w,” “eo”

- Line 18: “d,” “st,” “d,” “d,” “st”

- Line 21: “S,” “s,” “s,” “s,” “r”

- Line 22: “t,” “rs,” “b,” “tw,” “th,” “b,” “th,” “r,” “b,” “rs”

- Line 23: “s,” “r,” “ss,” “r”

- Line 24: “r,” “s,” “s”

End-Stopped Line

- Line 2: “rows.”

- Line 3: “glows,”

- Line 5: “Mass.”

- Line 6: “grass.”

- Line 10: “dispel,”

- Line 12: “heat.”

- Line 14: “eyes,”

- Line 18: “dust.”

- Line 22: “beers.”

- Line 24: “care.”

- Lines 1-2: “alone / with”

- Lines 4-5: “he / a”

- Lines 7-8: “trays / beneath”

- Lines 8-9: “then / though”

- Lines 9-10: “again / to”

- Lines 11-12: “feet / of”

- Lines 13-14: “features / faintly”

- Lines 15-16: “cries / of”

- Lines 16-17: “approval / without”

- Lines 17-18: “must / and”

- Lines 19-20: “white / from”

- Lines 20-21: “six / for”

- Lines 21-22: “prick / with”

- Lines 23-24: “where / he”

- Line 2: “spools of suffering”

- Line 6: “All flesh is grass”

Parallelism

- Lines 10-11: “to ordinary pain which simple weather can dispel, / to fields which don’t explode beneath the feet”

- Lines 16-18: “how he sought approval / without words to do what someone must / and how the blood stained into foreign dust.”

- Lines 4-5: “as though this were a church and he / a priest preparing to intone a Mass.”

“War Photographer” Vocabulary

Select any word below to get its definition in the context of the poem. The words are listed in the order in which they appear in the poem.

- "All flesh is grass"

- Sunday's supplement

- Impassively

- (Location in poem: Line 1: “dark room”)

Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme of “War Photographer”

Rhyme scheme, “war photographer” speaker, “war photographer” setting, literary and historical context of “war photographer”, more “war photographer” resources, external resources.

"War Photographer" Read Aloud — Listen to the poem read aloud.

Trailer for the Documentary "War Photographer" — Watch the trailer for the 2011 documentary War Photographer, which explores the responsibilities of photographers in war zones, focusing on photographer James Nachtwey.

"The Terror of War" — Explore Nick Ut's image from the Vietnam War, "The Terror of War." This famous photograph may have inspired "War Photographer." Note the second photographer at the right of the image examining his camera as children run by him, burnt and naked.

Carol Ann Duffy Biography — Learn more about Carol Ann Duffy, Britain's first female Poet Laureate, on Poets.org.

Interview with War Photographer Nick Ut — Watch this NBC interview with Vietnam War photographer Nick Ut about taking his famous photo depicting the naked "Napalm Girl" and the responsibility of photographers in war zones. Ut's comments intersect potently with the themes explored in "War Photographer."

LitCharts on Other Poems by Carol Ann Duffy

A Child's Sleep

Anne Hathaway

Before You Were Mine

Death of a Teacher

Education For Leisure

Elvis's Twin Sister

Head of English

In Mrs Tilscher’s Class

In Your Mind

Little Red Cap

Mrs Lazarus

Mrs Sisyphus

Pilate's Wife

Pygmalion's Bride

Queen Herod

Recognition

Standing Female Nude

The Darling Letters

The Dolphins

The Good Teachers

Warming Her Pearls

We Remember Your Childhood Well

Everything you need for every book you read.

The Hyperbolit School

Your trusty englit guide.

Looking at war poetry (II): Wilfred Owen’s ‘Exposure’ and Ted Hughes’ ‘Bayonet Charge’

(This post contains two detailed videos on the topic.)

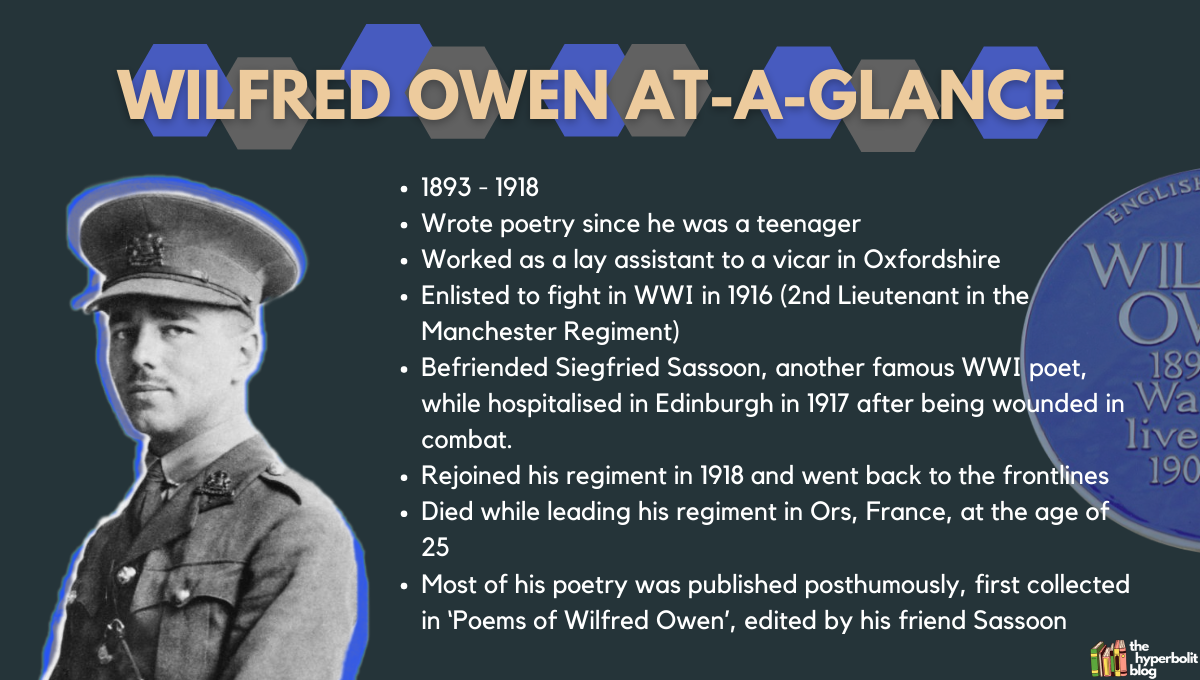

Previously, I wrote a post analysing Wilfred Owen’s ‘Insensibility’ and Carol Ann Duffy’s ‘War Photographer’ , which are about apathy towards war. In this post, we’re ramping up the volume by looking at stronger feelings towards war, such as despair and nihilism.

We’re sticking with Wilfred Owen though, largely because he’s written too many excellent war poems for just one post to do justice.

Also, if there’s anyone who understands war first-hand, it’s Owen, having served in and died at battle – all in the short, tragic span of 25 years. Owen’s life, in essence, was a sacrificial exercise in what his poetry often challenged – patriotic devotion without rhyme or reason.

After being wounded by a trench mortar shell in 1917, the second lieutenant was hospitalised in Edinburgh, where he wrote many of his most canonised poems, including ‘Exposure’. This poem is a meditation on the meaning (or lack thereof) of war, and the crisis of one’s faith in God and country.

But experiencing war and its attendant emotions doesn’t always have to be done first-hand.

Unlike Owen, Ted Hughes never actually served on the frontlines: he was born after WWI in 1930, and for national service, he was a ground wireless mechanic in the Royal Air Force, during which time he apparently “read and reread Shakespeare and watch[ed] the grass grow”. But this absence of personal involvement in war doesn’t make his poem, ‘Bayonet Charge’ (1957) – which captures a soldier’s frantic running on the battlefield – any less poignant.

The poet was inspired by his father’s stories about the Western Front, where Hughes Senior had fought and escaped death, eventually returning home as one of the few men who had survived the 1915-16 Battle of Gallipoli.

The biggest question of all

One of the central questions that ‘Exposure’ and ‘Bayonet Charge’ ask is ‘what’s the point?’

Obviously, what’s the point of war; but even more so – and perhaps counterintuitively – what’s the point of living when you’re living to die?

The agony that both Owen and Hughes’ speakers feel about their war-tied identity (as soldiers) and situation (in the trenches) isn’t so much existential as it is philosophical: they aren’t afraid of death – indeed, they seem to embrace it in their own ways – but they are terrified of death without cause or meaning .

For poets who wrote war panegyrics (like Rupert Brooke), blind devotion to war service wasn’t an issue, because to them war was always fought for national glory, and that alone is worth dying for.

In any case, there was always God, and the resignation of oneself to his great but unknown ways would suffice to justify the irrationality of war.

But what if one loses faith in both country and God, or doesn’t see God as part of the picture at all?

Is war still worth the sacrifice? And what is the philosophical meaning that ‘justifies’ military sacrifice, if such sacrifice can be justified at all?

Reading Wilfred Owen’s ‘Exposure’ (1918): noisy silence and ghostly rhymes

‘Exposure’ opens with the speaker and his fellow sentries waking up, migraine-stricken, exhausted but fearful of dozing off again lest there be another sudden attack.

Rhyme in ‘Exposure’

This state of vertigo is reflected in the series of slant rhymes and internal rhymes , which echo within and criss-cross from line to line. For instance, “ache/awake”, “iced/knive” home in on the harsh sensations the speaker feels, while the pararhymes of “wearied/worried”, “silent/salient”, “curious/nervous” draw our attention to the mental state and wider environment the soldiers are thrust in.

We are, as it were, ‘hit’ by a flurry of sharp physical and psychological descriptions right from the outset, which is not unlike the way those “merciless iced east winds” attack the soldiers’ faces in sudden blows.

The vowel overlap in “silence” and “happens” introduces the ironic tension that besiege the men’s minds, as they fear the violence that action will bring, but also crave the predictability of such action.

In their situation, even a violent attack would seem more comforting than the uncertainty of lying in wait, of having to deal with the “silence” of not knowing when and where bullets will come attacking. (And this uncertainty comes full circle with the repetition of the word “silence” in line 16, when “Sudden successive flights of bullets streak the silence”.)

As the poem moves from describing the scene in the trenches to the half-dream, half-memories of the dozed-off soldiers, the rhymes become less haphazard, and assume a semblance of order as homophones –

Slowly our ghosts drag home: glimpsing the sunk fires, glozed With crusted dark-red jewels; crickets jingle there; For hours the innocent mice rejoice: the house is theirs; Shutters and doors, all closed: on us the doors are closed,— We turn back to our dying. (Stanza 6)

What emerges from this progression in rhyme is a jarring contrast between the chaotic randomness of the trenches and the domestic harmony of the home.

Compared to the frantic, scattered nature of the rhymes in the first half of the poem, we see the homophone of “there/theirs” in line 27 to 28 and the repeated words “closed/closed”, which are syntactically enclosed within line 29.

As part of the soldiers’ memory of their pre-war lives, these sonic echoes highlight the gulf which now lies between their past comforts and present toils.

The repeated “closed/closed” makes the scene especially wistful: whereas the first “closed” describes the literal state of these “shutters and doors [back home], all closed” (as any house would be), the next clause reveals a tragic irony, as we realise from the hyperbaton of “on us the doors are closed” that this ‘closedness’ augurs a kind of social rejection that these men may (or fear they may) receive even if they were to make it back home.

So the thing that they’re supposed to want the most – homecoming – loses its warmth and meaning, for if both antipathy and apathy are what lie in wait, then is there still a point to returning home, or should they instead, “turn back to our dying”?

The irony is compounded by the reference to “innocent mice rejoice: the house is theirs”. What would normally be viewed as vermin in the home are instead the rightful owners, leaving the humans to look on from the outside.

As we reach the final stanza, the internal rhyme of “mud” and “us” seems to conflate earth and flesh, while the “frost… fasten[ing itself] on this mud and us” reinforces this idea that in battle, there is no longer a distinction between the grime at one’s feet and the man who possesses that feet. Mud is man; man is mud – this imagery, while morbid, is accurate, just as corpses lie amidst muddy earth.

As for “their eyes are ice”, it’s ambiguous who the implied ‘they’ refers to. Is it to “the burying-party”, or to the “half-known faces” that have presumably been frozen to death? Is the ‘iciness’ a result of one dying for his country, or a reflection of another’s one cruelty on his fellow man? Or both?

Either way, Owen suggests through the half-rhyme of “eyes/ice” the idea that coldness from death and coldness towards life aren’t all that different, which is, of course, a depressing thought.

Meter in ‘Exposure’

Another source of tension in the poem comes from the pull between its stanzaic regularity and rhythmic variation. On the macro level, each of the eight stanzas are cinquains with a final clipped line (which is also the refrain) , but if we look a bit closer, we’ll see that there is a striking amount of range in both meter and foot.

First, the poem’s range of feet is incredibly diverse, with iambs, trochees, dactyls, spondees all mixed into the prosodic fray.

Iamb: “But nothing happens” (lines 5, 15, 20, 40)

Trochee: “… flights of bullets streak the silence” (line 16)

Dactyl (\xx): “What are we doing here?” (line 10)

Spondee (\\): “Shutters and doors, all closed:…” (line 29)

This rhythmic diversity is perhaps a microcosm of the chaos and the regiment itself: the soldiers may look similar in military uniform and unified in patriotic duty, but upon closer inspection, they are each a different, complex individual with varying emotions, memories, values and aspirations.

But in the context of war, these men – individuals as they may be – are bound by a similar kind of despair, nihilism and loss of faith. We see this reinforced by the use of the refrains.

If we juxtapose the final lines of each stanza, we’ll see a pattern emerge as such:

But nothing happens.

What are we doing here?

Is it that we are dying?

We turn back to our dying.

For love of God seems dying.

Technically, there’s only one perfect refrain in this poem, and that’s the statement – “But nothing happens”, which we find at the end of stanzas 1, 3, 4, and 8.

The fact that we begin and end with this pronouncement suggests the triumph of apathy, and highlights the grim reality of there being no messianic force or deus ex machina to deliver these soldiers out of their suffering.

As much as we’d like there to be a change in fortune for the better, Owen’s view is that such deliverance doesn’t really exist, which echoes the crisis of faith that so troubles the speaker in this poem.

And we see this reflected in the other thread of refrains, from ‘Is it that we are dying?’, to “We turn back to our dying”, to “For love of God seems dying”.

The refrain of “dying” shows the all-encompassing breakdown of the speaker (and his fellow sentries), as their ‘dying’ isn’t just the existential sort,, but extends also to their philosophical, spiritual and religious consciousness.

So it’s telling, then, that when we reach the final stanza, regularity is restored to some extent , as the lines alternate between iambic and trochaic hexameters , with lines 36-39 ending on a masculine stress (courtesy of the docked syllable, which also makes lines 37 and 39 catalectic), before it reverts to the feminine ending of the refrain “But nothing happens” (again, because of the final docked syllable).

The suggestion of this is pessimistic: despite the speaker’s desire and will to retain his individuality, the oppressive force of war is just too overpowering for this to be possible.

The syntax in the penultimate stanza (7) deserves some attention, especially that of lines 33-35 –

“For God’s invincible spring our love is made afraid; Therefore, not loath, we lie out here; therefore were born, For love of God seems dying.”

But first, what is the speaker saying here? The word “loath” means “unwilling”, and yet here Owen uses a double negative “not loath” to express the soldiers’ ‘not-unwillingness’ to be out in the fields. But does this mean that they are actually willing?

The wordplay could offer a clue: “loath” could remind us of “loathe” with an ‘e’, which means hatred, and this perhaps points us towards the men’s true emotions about their situation.

Are they lying out here in the battlefield because of “love” for country and God, or rather, a “love [that’s] made afraid”, which ceases to be a feeling of love, but terror?

The twisted, dislodged phrases, chopped up by caesurae in a way that mirrors the men’s emotional and mental fragmentation, convey the inner writhing that the speaker feels about the whole business of war.

The use of “therefore” supposedly connotes causality, but the irony is that everything has now become so illogical, the brutality of war so inexplicable, that the order between life and death, like the order of the clauses, has become reversed, and the reason for fighting is tangled up in the confusion and fusion of love and fear.

An intertextual tangent…

We can compare this syntactical jumble to another poem about loss of faith – Gerard Manley Hopkins’ ‘Carrion Comfort’ (1885) , which opens like this:

Not, I’ll not, carrion comfort, Despair, not feast on thee; Not untwist – slack they may be – these last strands of man In me or, most weary, cry I can no more. I can; Can something, hope, wish day come, not choose not to be.

Like the speaker in ‘Exposure’, Hopkins’ speaker is also struggling with thoughts of despair, as he feels his faith, humanity and verbal logic slipping away. Notice that the lines here are similarly jumbled and disorderly, with the shared word “not” indicating a sense of emotional resistance.

Interestingly, Hopkins also uses a hexameter structure in this poem. It’s worth noting that English verse doesn’t lend itself very naturally to anything longer than the pentameter.

So perhaps when poets like Owen and Hopkins decide to adopt the hexameter, they are precisely exploiting the awkward, prodding nature of the six-foot line to convey discomfort and disarray – despite a need to carry on.

Before we move on to ‘Bayonet Charge’, I’ll make a final point about personification in this poem, which recurs throughout to bring out another irony about the soldiers’ situation. For an environment that is so deadly “silent”, nature and its agents seem remarkably alive, as we can tell from these descriptions:

“… in the merciless iced east winds that knive us” “low drooping flares confuse our memory of the salient” “… mad gusts tugging on the wire” “Dawn massing in the east her melancholy army Attacks once more in ranks on shivering ranks of grey” “the air that shudders black with snow” “…sidelong flowing flakes that flock, pause, and renew, We watch them wandering up and down the wind’s nonchalance” “Pale flakes with fingering stealth come feeling for our faces” “For hours the innocent mice rejoice: the house is theirs;” “Since we believe not otherwise can kind fires burn; Now ever suns smile true on child, or field, or fruit” “this frost will fasten on this mud and us, Shrivelling many hands, and puckering foreheads crisp.”

While the humans are hanging by a thread, nature is flourishing in her apathy and inflicting pain on man.

It’s certainly strange to see that the brutality at play doesn’t really come from the usual accoutrements of war; the only presence of weaponry we see is in line 16, “Sudden successive flights of bullets streak the silence”, but ironically, the bullets are “less deadly than the air that shudders black with snow”.

Bullets, a human invention, are apparently less powerful than the bare cold wind, which highlights both the harsh conditions of the landscape, and the relative inferiority of man versus nature.

After all, Nature herself is immune from the bullets and ammunition that men themselves so fear.

What’s most tragic, though, is that while “merciless… winds” hurt, the “kind fires” of the “suns” which “smile true on child, or field, or fruit” cannot heal – not the wounded body, nor the disillusioned soul.

As such, Owen uses personification to show the men – the ‘persons’ at war – in their least person-like state, as they are reduced by nature’s force and man’s own inhumanity.

Watch the video on this:

Reading Ted Hughes’ ‘Bayonet Charge’ (1957): sharp edges and endless circles

Whereas the speaker of ‘Exposure’ comes out his stupor in muted drowsiness, the one in ‘Bayonet Charge’ wakes up from the trigger of a violent spurt.

The dactyl “Suddenly” plunges the reader right into the heart of the action, as the poem’s narrative opens in medias res .

Thereafter, it’s speed, noise, sound and fury all rolled into one, as we see the soldier running and stumbling his way across a field.

The language is chock full of kinaesthetic imagery , but as we reach the second stanza, there is a temptation for all the “running”, “stumbling”, “smacking”, and “sweating” to stop altogether, as the speaker asks himself the million dollar question of why .

Why is he running; what is he running from; and what is he running towards ?

If we pay attention to the shape of the stanzas, we’ll notice that there’s one protruding line that juts out in each stanza, which offers a visual mimicry of the bayonet at the tip of a rifle, but also a formal re-enactment of the speaker’s forward-lunging momentum. In particular, lines 3 and 19 –

“Stumbling across a field of clods towards a green hedge”

“He plunged past with his bayonet toward the green hedge”

-marry the hypercatalectic lines with the image of the speaker running and plunging forward.

But the symbolism of the “green hedge” rubs against what’s happening in the poem. Hedgerows are normally found in well-maintained, orderly gardens, while greenery connotes life.

The speaker, however, is clearly in a state of disorder, and the danger that surrounds him positions him closer to the axis of death.

Is he, then, running towards a vision of hope, despite its seeming unreachability, which is implied by the fact that he begins running towards the hedge, and continues running towards this same hedge even as the poem reaches its end?

This question of just what the speaker is running for is examined in the middle stanza, which also happens to be one line shorter (a septet) than the first and final stanzas (both octets).

At this point, the bifurcation of outward and inward action comes to the fore: the soldier doesn’t stop running (“he almost stopped”), but his mind suspends for a moment to consider, “in bewilderment”, the forces that compel and propel him to keep running.

In what cold clockwork of the stars and the nations Was he the hand pointing that second? […]

Here, Hughes combines the metaphor of “clockwork” with the metonymy of “the stars and the nations”.

These lines zoom out from the scrutinising, microscopic glare that has so far been posed on the speaker in the first stanza, and lead us to question just how the soldier came to be in the very moment, situation and role he finds himself in.

The metaphor of the clockface and the soldier as the clock “hand” conveys a sense that the man is running out of time (and so must run even faster), but also functions as a memento mori – the idea that no matter how quickly or desperately he runs, he is (and we are) only ever running towards death.

In this light, the idea of moving “toward the green hedge” reads like a sad mockery of man’s desire to cling onto life, especially when the reason for living isn’t always entirely clear – or even desirable.

Meanwhile, “the stars” and “the nations” are metonymic substitutes of fate and politicians – forces which, to varying extents, appear to ultimately dictate how everyone’s lives turn out.

And so, these ‘forces’ prod the soldier onwards in a blind frenzy of compulsive movement, which the enjambment from line 11 to the first half of line 14 cinematically reflects –

He was running Like a man who has jumped up in the dark and runs Listening between his footfalls for the reason Of his still running,

The phrase “still running”, however, jolts us out of this kinaesthetic stream, as it hits against the caesura of the comma, and proceeds into the static suspension of –

and his foot hung like Statuary in mid-stride.

There’s two ways of understanding “still running”, depending on whether we read the word “still” as an adjective or an adverb. As an adverb, “still” means ‘continue in the same way’, which aligns with the literal action of the soldier in this scene.

As an adjective, though, “still” means ‘not moving’ or ‘deep silence’, in which case the phrase becomes an oxymoron, and crystallises the asynchronous chasm between outer movement and inner thought – his limbs are moving, but his mind has already come to a standstill.

The sense here is that something’s amiss, whether it be the reason for his constant, frantic footfall, or the rationale behind being a part of this madness of war, or even – the missing eighth line from this septet, mirrored also by the incompleteness of the “mid-stride”.

There are a lot of similes in this poem, but what makes them interesting is the way they form a collective image of circularity. Note the circular motif in the objects and actions of this poem:

– The cyclical shape one’s legs make when running

– Reference to “bullet smacking the belly out of the air”

– “The patriotic tear that had brimmed in his eye

– Sweating like molten iron from the centre of his chest”

– The metaphor of the clock

– The “yellow hare that rolled like a flame

– And crawled in a threshing circle”

– Its “mouth wide/Open silent, its eyes standing out”

And what of this circularity?

Perhaps Hughes is suggesting that there is no end to the business of warfare, and that even if one manages to outrun a bullet, there are greater forces (recall “the stars and the nations”) that keep the cycle of war going; that even if one battle concludes, another one will emerge in due course.

The anatomical ‘circles’ of legs running, an open-wide mouth and teary or bulging eyes are juxtaposed against the ‘circles’ of temporality (“cold clockwork”) and hellishness (“rolled like a flame”), which puts forth the simple, but pessimistic, idea that man can neither outrun time nor overtake his own potential for evil.

Finally –

King, honour, human dignity, etcetera Dropped like luxuries in a yelling alarm

The cavalier touch of “etcetera” conveys that in times of war, the values that one is taught to hold dear – patriotism (“King”), decency (“honour”), “human dignity” – immediately lose their importance, and if pursued, could even jeopardise one’s chances of survival.

As such, there is a need to jettison them as one would bombs, which is why they are here “dropped like luxuries in a yelling alarm”.

By comparing these values to “luxuries”, Hughes mocks the naivete of those who claim that war is fought for noble causes, because one is almost always forced to dispense with nobility in the heat of battle, and to prize survival above all else.

To read my analysis of other poems, check out my posts below:

- An analysis of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s ‘Love’s Philosophy’ and Lord Byron’s ‘When We Two Parted’ (Romantic poetry)

- An analysis of William Wordsworth’s ‘Tintern Abbey’ and John Keats’ ‘To Autumn’ (Romantic poetry)

- An analysis of John Agard’s ‘Checking Out Me History’ and Maya Angelou’s ‘Still I Rise’ (BAME poetry)

- An analysis of Robert Browning’s ‘Porphyria’s Lover’ and Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s ‘Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point’ (Dramatic monologue)

share this with a friend!

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

susansenglish

What I love… Education based blog by @susansenglish

Why I love…Comparing in the AQA Anthology: Poppies and War Photographer

In this series I have tried to put together some high level examples of comparisons for the AQA Power and Conflict Anthology. The next poems that I’ll be teaching are Poppies and War Photographer so I’ve tried to complete a high level example on these two poems. Hopefully, the comparisons make sense. Any feedback is much appreciated. I’ve linked here to the other comparison blogs and at some point there will be a full set across the Anthology. A copy of the essay can be downloaded here: Poppies vs War Photographer

Why I love…Comparing AQA poems a series: Ozymandias and My Last Duchess

Why I love…Comparing Poems: AQA Extract from the Prelude and Storm on the Island

Why I love…Comparing Poems: AQA Exposure by Owen with Storm on the Island by Heaney

Why I love…Comparing Poems: AQA Charge of the Light Brigade and Bayonet Charge

Explore the presentation of powerful emotions related to conflict in Poppies and War Photographer.

Powerful emotions are shown in both poems: Poppies and War Photographer through the perspective of people outside of the conflict, but who experience a form of conflict themselves. In Poppies the persona appears to be a mother, who is experiencing feelings of loss as a result of her son growing up and going to war. War Photographer depicts the outsider’s perspective in a different way to Poppies: it is seen more vividly and visually through the eyes of someone experiencing the conflict, photographing the conflict but not being able to do anything to help those injured by the conflict. In this way the conflict and powerful emotions, while different are equally powerful. Memory, visual representation and the power of touch is presented in both poems to reinforce the way powerful emotions are created by the experiences of conflict.

Both poets use memory to reinforce the powerful emotions evident in the poems. Memory, in Poppies appears to be from a mother, who seems to remember her son leaving for school or leaving for the war. The mother “pinned one onto your lapel” with the past tense implying that this was something that happened and a memory that is sharply remembered, as a result of the imminence of “Armistice Sunday”. The significance of the proper nouns and use of “Armistice” is important as it has symbolic meaning as a time when we all get together to remember those who fell in war, a time for reminiscing and a time to reflect on the human sacrifices that were made. The ambiguity over whether the jacket was a school blazer, or an army jacket increases the poignancy. Irrespective of when the poppy was “pinned” onto the “lapel” the tactile action is maternal and loving and shows the bond between mother and child, that grows from when they are little and remains even when they are grown up. Memory is differently explored in War Photographer and the memory is from the perspective of a persona, who was in the conflict, but as a bystander and observer, rather than as an active participant. Their memory is sharply painful “the cries of this man’s wife” with the enjambment reinforcing the powerful jolt of remembrance, when the “half formed ghost” appears as it is revealed in his darkroom. The photographer appears to have compartmentalised what he saw and refers to the memories using emotive language “a hundred agonies in black and white” which almost dehumanises the powerful emotions linked to the conflict that was seen by the war photographer, as the vast array of “agonies” reflects the habitual suffering that humanity experiences during conflict. However, Duffy may have been influenced to write about the powerful emotions in the poem in a detached way to show the outside world the horror that her friends had to catalogue and photograph, while not being able to help or do anything, as that was not what they were there to do. This dehumanisation of the people depicted in the poem is further reinforced by the next step of removal from the horror when the fact is used that “the editor will pick out five or six”, which is completely different from the first-person perspective in Poppies. The mother in Poppies seems to live and breathe the pain and suffering, whereas the photographer is once removed from the suffering.

Furthermore, both poets use visual representations to emphasise the powerful emotions that are evident in the poems. In poppies the imagery of “poppies…placed on individual war graves.” Is an incredibly strong visual, as most people have experienced the sight of poppies on graves as a form of memorial, so this is familiar and significant. Unlike this public visual display, in War Photographer, he is “finally alone” creating imagery of a relief that the photographer is able to hide away in his darkroom surrounded by the ironic “spools of suffering” as the old-fashioned camera’s had “spools” of film that captured the images. The sibilance here perhaps reinforces the visual representation of the sheer amount of powerful emotions contained in the film that has yet to be developed. As well as the actual poppies creating vivid visual imagery and the as yet undeveloped film from War Photographer, in Poppies the setting is visually represented. Duffy has the persona “skirting the church yard walls,” with the verb “skirting” implying that she does not want to be there or does not want to be seen, as if she wants to fade into the background, but the visual imagery of a churchyard is very commonplace and familiar to British people. Whereas, in War Photographer the setting and visual representation of areas is listed with the proper nouns naming places that are far away and unfamiliar to the reader “Belfast. Beruit. Phnom Penh.”. All these places are known to be places that have suffered from conflict and the removal of the familiar by Duffy to the less familiar name only settings could show another removal from the powerful emotions that ordinary people feel when they see images in the newspapers. As Duffy reflects the “reader’s eyeballs prick with tears” which is a recognition of the powerful emotions reflected in the photographs taken of the conflict but the juxtaposition of the familiar comfort of everyday life shows that this is a fleeting moment of empathy for most people “between the bath and pre-lunch beers”. Both poems use visual representations as a way of familiarising and defamiliarising the conflict and the powerful emotions felt as a result of the conflict.

Finally, both poems use the power of touch through the tactile acts inherent in the poems. As a seamstress, Weir uses imagery of keeping the hands busy and using touch to make the persona seem closer to their lost loved one. The verbs “traced”, “leaned” and “pulled” in the final stanza show the powerful emotions of the persona missing her son and using touch as a way to keep her with her son. Although, it isn’t only touch, the senses are important too and she “hoping to hear your playground voice” implying she misses a time when her son was young, free and innocent and wants to remember this. Powerful emotions of loss are shown in the way she continually references caring touches “smoothed down your shirt’s” which are clearly memories of what she did when her son was with her. Duffy, meanwhile, uses the actions of the people suffering in the conflict to create the feeling of how futile the conflict was “running children in a nightmare heat.” These images are only possible due to the developing of these with hands that “tremble” even though they “did not tremble then” which implies that while undertaking the job of taking photographs of the conflict the photographer is fine, but not after the event, when he has time to reflect and think about it. Both Poppies and War Photographer show the power of touch in bringing powerful memories to the surface. In Poppies this is done through the memory of tactile acts of care between the mother and the son and in War Photographer through the developing of the film and the release of the memories as a result of the pictures that were taken.

Both poets reflect powerful emotions in different ways. The powerful emotions in Poppies appear to be reflected through the relationship of a mother and a son and this leads to a very personal reflection, which one could be forgiven for thinking is Weir’s own experience but is not. Whereas, in War Photographer the experience is that of a third-party bystander, who was employed to take pictures of the conflicts and sell these, but Duffy shows that the powerful emotions evoked by the pictures mean that the persona is not able to see this as a purely business and unemotional transaction. Both poets show the powerful emotions through the persona’s and although they are very different in many ways, the suffering of humanity is evident in both poems.

Hope that this comparison is useful.

Share this:

6 thoughts on “ why i love…comparing in the aqa anthology: poppies and war photographer ”.

- Pingback: Why I love…Comparing Tissue and The Emigree – susansenglish

- Pingback: Why I love… AQA Comparisons Series: An Introduction – susansenglish

- Pingback: Why I love…Comparing Poems: AQA ‘Checking Out Me History’ with ‘The Emigree’ – susansenglish

omg thats amazing well done. It helped me a lot.

- Pingback: Why I love…Comparison Collection Power & Conflict AQA – susansenglish

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Social menu.

- Why I love…Closed Book for GCSE Literature

- Why I love…How – What – Why – Emotional Response for Analysis

- Why I love…Law in R&J

- Why I love…Instructions

- Why I love… My Dad

- Why I love…Challenging perceptions of drugs with students

- Why I love…#Hay30

- Why I love…Just another lesson

- Why I love…Considering Evaluation Style Questions

- Why I love… Challenging Apathy

- Why I love… Writing at the same time as the class

- Why I love … Religion in A Christmas Carol

- Why I love…Engagement in Y13 & Hamlet Podcasting

- Why I love… The Power of Three for Revising

- Why I love… Going back to basics: Instructions

- Why I love… Shakespeare (& think teaching it is so important)

- Why I love…Promoting Analysis

- Why I love…Considering Leadership Qualities

- Why I love…Easter & reading: the Carnegie shortlist

- Why I love…Quizlet

- Why I love… Engaging Revision or ‘The Final Push’

- Why I love… Metacognitive Activities

- Why I love… Quick Revision Wins

- Why I love… Thinking about Transactional Writing

- Why I love…Podcasting with @ChurchillEng

- Why I love… #LeadPChat

- Why I love… Teaching Hamlet

- Why I love…Teaching (part 2)

- Why I love…collaborative Inset @NSTA

- Why I love… Developing 2A: Non-Fiction Reading Unit @Eduqas_English

- Why I love…Encouraging Revision @Eduqas_English

- Why I love…Twitter Revision

- Why I love… exploding an extract

- Why I love… teaching the Language Reading Paper

- Why I love… teaching Unseen Poetry

- Why I love… Assessment policy development for the New GCSE @Eduqas_English

- Why I love… Considering Context @Eduqas Poetry Anthology

- What I love… about unpicking the Eduqas Language Fiction Paper 1A (A4 & A5 Only)

- What I love… unpicking the Eduqas Language Fiction Paper 1A (A1 – A3 Only)

- Why I love…(d) #TLT16

- What I love… about #WomenEd

- Why I love… Quotations and Retention

- Why I love positive parental contact…

- Why I love collaboration in Year 13…

- Why I love our Eduqas revision site

- Why I love to read…

- Why I love A Level & AS Level results…

- Why I love thinking about classroom displays…

- Why I love collaborative working…

- Why I love summer…

- Why I love teaching…

- Why I love…CPD Feedback

- What I love… the little things

- Why I love… Training @Eduqas_English

- Why I love… #lovetoRead My Desert Island Books

- Why I love…teaching poetry

- Education Based blog

- Why I love…The A5 Fiction/A4 Non-Fiction Evaluation Question

- Why I Love…Blog Series 18: Mametz Wood By Sheers

- Why I love… Scaffolding the Tension and Drama – Structure Question for @Eduqas_English

- Why I love…Scaffolding: Language Analysis Questions

- Why I love…Blog Series: Introducing Context (War focus)

- Why I love…Scaffolding: Comprehension A1 Fiction Language @Eduqas_English

- Why I love…Blog Series 17: Ozymandias by Shelley

- Why I Love…Building Girls’ Confidence: My #WomenEdSW session

- Why I love…Strategies for stretch and challenge

- Why I love… Developing Analysis using Triplets

- Why I love…Blog Series 16: Dulce et Decorum Est by Owen

- Why I Love… Blog Series 15: Afternoons by Larkin

- Why I love… Vocabulary Improvement Strategies

- Why I love…Blog series 14: To Autumn by Keats

- Why I love…Embedding Knowledge Organisers into learning

- Why I love…Whole Class Feedback & Other Time-Saving Feedback Strategies

- Why I love…Blog Series 13: Hawk Roosting by Hughes

- What I love…Learning from #TLT

- Why I Love… Live Modelling for across the curriculum

- Why I love…(d) #TLT17 @TLT17

- Why I love…Blog Series 12: Death of a Naturalist by Heaney

- Why I love…Blog Series 11: A Wife in London by Hardy

- Why I love…Blog Series 10: Valentine by Duffy

- Why I love…Eduqas Blog Series 9: Cozy Apologia by Dove

- Why I love…Eduqas Blog Series 8: As Imperceptibly as Grief By Dickinson

- Why I love…Literature Examiner key considerations

- Why I love…Eduqas Anthology: Blog Series 7 Living Space by Dharker

- Why I love…Unpicking the Eduqas Examiners report – Literature

- Why I love…Unpicking the Eduqas Examiners report – Language

- Why I love…Eduqas Anthology: Blog Series 6 – She Walks in Beauty Byron

- Why I love…Eduqas Anthology: Blog Series 5 – The Soldier by Rupert Brooke

- Why I love…Eduqas Anthology: Blog Series 4 – London by Blake

- Why I love…Eduqas Anthology: Blog Series 3 Sonnet 43

- Why I love…Eduqas Anthology: Blog Series 2 – The Manhunt

- Why I love…Closed Book for GCSE Literature

- Why I love…How – What – Why – Emotional Response for Analysis

- Why I love…Law in R&J

- Why I love…Instructions

- Why I love… My Dad

- Why I love…Challenging perceptions of drugs with students

- Why I love…Considering Evaluation Style Questions

- Why I love…Engagement in Y13 & Hamlet Podcasting

- Why I love…Teaching

- Why I love thinking about classroom displays…

- Why I love A Level & AS Level results…

- Why I love to read…

- What I love… about unpicking the Eduqas Language Fiction Paper 1A (A4 & A5 Only)

- Why I love…teaching poetry

- Why I love…CPD Feedback

- What I love… the little things

- Why I love… Training @Eduqas_English

- Why I love…Twitter Revision

- Why I love…Teaching (part 2)

- Why I love… Teaching Hamlet

- Why I love…Podcasting with @ChurchillEng

- Why I love… Quick Revision Wins

- Why I love…Easter & reading: the Carnegie shortlist

- Why I love…Considering Leadership Qualities

- Why I love… Shakespeare (& think teaching it is so important)

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

War Photographer / Remains Essay

(grade 5-6).

Both ‘War Photographer’ and ‘Remains’ explore memories. In the second stanza of ‘War Photographer’, Duffy creates a vivid image of one of the photographer’s memories by writing ‘running children in a nightmare heat’. Duffy’s words create graphic, powerful imagery of innocent children caught up in the middle of a warzone, running in agony and terror away from a chemical weapon. Duffy suggests through these words that the photographer's mind is always filled with powerful and upsetting memories of the terrible things he witnessed while taking photos in warzones. Armitage makes clear the soldier cannot forget the memory of shooting the looter by writing ‘probably armed, possibly not’. Armitage’s repetition of these words in the poem emphasise that this particular memory, of whether or not the looter is armed, is very important. It is important because the soldier is wondering whether or not he needed to kill the looter. If the looter was not armed, the soldier killed an innocent person, who posed no threat to him. Armitage’s use of the word ‘possibly’ indicates that the soldier cannot be sure that the looter was armed, and runs this memory over and over in his mind. Armitage’s repetition of these words also emphasise the power of this memory, as it keeps flooding back into the soldier’s mind, even when he is home on leave. It is clear from both poems that being in or near war can deeply affect people, leaving them with lasting trauma.

Both ‘War Photographer’ and ‘Remains’ explore guilt. In the third stanza of War Photographer, Duffy makes the photographer’s guilt clear by writing that he sees a ‘half-formed ghost’ when he develops one of the photographs. Duffy’s imagery in the words ‘half-formed’ helps the reader to imagine the photograph slowly developing in front of his eyes. Her use of the word ‘ghost’ implies that the photographer is being haunted by the memory of this man and the cries of the man’s wife when she realised her husband was dead. Duffy suggests he feels guilty because he was not able to do more to help this man or his wife; all he could do was stand by and take a photograph. Similarly, in the closing lines of ‘Remains’, Armitage makes the soldier’s guilt clear by writing ‘his bloody life in my bloody hands’. Armitage uses the blood as a symbol of the guilt that the soldier feels; the soldier feels he has blood on his hands because he killed a person who could have been innocent. Armitage could have chosen to end the poem with this line because he wanted to demonstrate that the soldier cannot remove the image of the looter’s blood from his mind, and that the guilt he feels for killing the looter will stay with him forever.

Both poems explore struggle . In the final stanza of ‘War Photographer’, Duffy conveys the struggle of the photographer, who feels angry that his readers are not more moved by his pictures by writing ‘reader’s eyeballs prick with tears between the bath and pre lunch beers’. Duffy’s use of the word ‘prick’ to describe the readers’ emotions indicates that they barely cry when they see the photographs. Duffy’s suggestion is that, when we are so far removed from war, we cannot fully understand the pain that people go through. Duffy’s use of the words ‘bath’ and ‘beers’ remind the reader that in England we have many luxuries that people in warzones don’t have. This makes it very easy for us to forget the terrible lives that other people have, because we can go back to enjoying our own luxurious lifestyles. The struggle in Remains is different. In Remains, Armitage presents the soldier as deeply traumatised by what he experienced at war. Remains makes clear the soldier struggles to forget what he saw and did by writing ‘the drink and drugs won’t flush him out’.Armitage’s use of the word ‘flush’ implies that the emotions the soldier feels are like toxins within his body that he wants to get rid of. It is clear that the soldier has become reliant on addictive substances as a way of coping. Armitage conveys to his readers the terrible trauma that many soldiers experienced and tells the reader how difficult it was for them to return to normal life when they returned.

(Grade 8-9)

Both ‘War Photographer’ and ‘Remains’ explore the haunting power of memories. In the second stanza of ‘War Photographer’, Duffy creates a vivid image of one of the photographer’s memories by writing ‘running children in a nightmare heat’. Here, Duffy’s words create graphic, powerful imagery of innocent children caught up in the middle of a warzone, running in agony and terror away from a chemical weapon. This poetic image was inspired by a real-life photograph captured by a war photographer in Vietnam. Through this evocative imagery, Duffy suggests that the photographer's mind cannot shake the distressing memories of the terrible pain he witnessed while taking photos in warzones. Similarly, Armitage makes clear the soldier cannot forget the memory of shooting the looter through his use of the poem’s refrain: ‘probably armed, possibly not’. Armitage’s repetition of these words emphasise that this particular ambiguous memory, of whether or not the looter is armed, is haunting him. If the looter was not armed, the soldier would not have needed to kill him. Therefore, he is plagued by a feeling of potential guilt; ihe could have killed an innocent person, who posed no threat to him. Armitage’s repetition of these words throughout the poem also emphasise the power of this memory, as it keeps flooding back into the soldier’s mind, even when he is home on leave. It is an unwelcome and persistent reminder that is contributing to his post-traumatic symptoms. It is clear from both poems that being involved in or an observer of war can deeply affect people, leaving them with a lasting mental struggle.

Both ‘War Photographer’ and ‘Remains’ explore the intensity of guilt. In the third stanza of War Photographer, Duffy makes the photographer’s guilt evident by writing that he sees a ‘half-formed ghost’ when he develops one of the photographs. Duffy’s powerful metaphor helps the reader to vividly imagine the photograph slowly developing in a chemical solution in front of his eyes, while the word ‘ghost’ implies that the photographer is being psychologically haunted by the memory of this man and the terrible cries of the man’s wife. Perhaps Duffy suggests that the photographer feels guilty because he was not able to do more to help this man or his wife; all he could do was carry out his role by capturing the moment with a photograph for the media. TSimilarly, in the closing lines of ‘Remains’, Armitage makes the soldier’s guilt clear by writing ‘his bloody life in my bloody hands’. Armitage uses the blood as a symbol of the guilt that the soldier feels; the soldier feels he has blood on his hands because he killed a person who could have been innocent. Armitage could have chosen to end the poem with this line because he wanted to demonstrate that the soldier cannot remove the image of the looter’s blood from his mind, and that the guilt he feels for killing the looter will stay with him, or metaphorically stain him, forever.

Both poems explore an inner conflict or struggle . In the final stanza of ‘War Photographer’, Duffy conveys the struggle of the photographer, who feels infuriated that his readers are not more emotionally moved by his pictures by writing ‘reader’s eyeballs prick with tears between the bath and pre lunch beers’. Duffy’s use of the word ‘prick’ to describe the readers’ emotions indicates that they barely cry when they see the photographs, or that their emotion is transient because they cannot empathise with the people in the photographs as they are so far removed from conflict zones. Duffy’s use of the words ‘bath’ and ‘beers’ remind the reader that in England we have many everyday luxuries that people in warzones don’t have. This makes it easy and almost inevitable for us to forget the terrible lives that other people have, because we are so engrossed in our own luxurious lifestyles. While there is an emotional struggle for the soldier in Remains, the nature of the strife is different. In Remains, Armitage presents the soldier as deeply traumatised by what he experienced at war. Remains makes clear the soldier struggles to forget what he saw and how he behaved by writing ‘the drink and drugs won’t flush him out’.Here, Armitage’s use of the word ‘flush’ implies that the emotions the soldier feels are like toxins within his body that he wants to eject. It is clear that the soldier has become reliant on addictive substances as a way of coping with the devastating effects of war and its violent agony. Armitage conveys to his readers the terrible trauma that many soldiers experience, and exposes to the reader how difficult it is for soldiers to adapt to normal life when they return from war.

Both Duffy and Armitage use structure to reflect an attempt to control difficult emotions . In ‘War Photographer,’ Duffy deliberately uses a tight stanza structure with a clear rhyme scheme to mirror the order the photographer is trying to restore in his own mind. He is described as putting his photographs into “ordered rows,” just as Duffy carefully brings order to the poem. Perhaps she is suggesting that this sort of organisation is the only way he can eliminate the chaos and distress he struggles with. In Armitage’s poem, the soldier is less successful in containing his emotional outpourings. While the poem begins in an ordered way with regular stanza structures, it descends into irregular and erratic stanzas to perhaps symbolise his inability to control the traumatic memories which continue to flood his mind.

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Poetry — Comparison Between War Photography (Carol Duffy) and Poppies (Jane Weir)

"Poppies" and "War Photographer": a Comparison of War Poems

- Categories: Carol Ann Duffy Poetry

About this sample

Words: 514 |

Published: May 19, 2020

Words: 514 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

- Dowson, J., & Dowson, J. (2016). Voices from the 1980s and After. Carol Ann Duffy: Poet for Our Times, 87-121. (https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-137-41563-9_3)

- Hughes-Edwards, M. (2006). ‘The House […] has Cancer’: Representations of Domestic Space in the Poetry of Carol Ann Duffy. In Our House (pp. 121-139). Brill. ( https://brill.com/display/book/9789401202817/B9789401202817_s010.xml)

- Dimarco, D. (1998). Exposing Nude Art: Carol Ann Duffy's Response to Robert Browning. Mosaic: A journal for the interdisciplinary study of literature, 25-39. ( https://www.jstor.org/stable/44029809)

- Schweik, S. (1987). Writing war poetry like a woman. Critical Inquiry, 13(3), 532-556 . ( https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/448407?journalCode=ci)

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

6 pages / 2918 words

2 pages / 1111 words

4 pages / 1811 words

1.5 pages / 724 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Poetry

Allen Ginsberg is a prominent figure in American literature, known for his influential poetry that captures the essence of the Beat Generation and critiques the social and political landscape of America during the Cold War era. [...]

"Ballad of Birmingham" is the author of the poem that revolves around a little girl who would like to go downtown to take part in a freedom protest. Her mother, however, says that she cannot go because of the dangerous [...]

In the contemporary society, many people undergo challenges depending on the nature of their environment, or sometimes due to uncertain circumstances for which they have no control. Yet amidst the challenges, they often hold [...]

In the poem "One Boy Told Me" by Naomi Nye, the poet exudes sensitivity, compassion and great heart. Nye touches on her diverse personal experiences that form the backbone of the poem. It is very interesting the way she brings [...]

Christopher Marlowe’s “The Passionate Shepherd to His Love” and Andrew Marvell’s “To his Coy Mistress” offer powerful examples of sensual, carpe diem Renaissance poetry. In both poems, the poet-speakers attempt to spur their [...]

“Whenever a thing is done for the first time, it releases a little demon” (Dickinson, n.d.). At first glance, this utterance by Emily Dickinson conveys a negative attitude towards the unique and the new. However, upon second [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- TOP CATEGORIES

- AS and A Level

- University Degree

- International Baccalaureate

- Uncategorised

- 5 Star Essays

- Study Tools

- Study Guides

- Meet the Team

- English Literature

- Comparisons

How is conflict presented in War Photographer and Remains by Simon Armitage?

How is conflict presented in ‘War Photographer’ and one other poem of your choice?

The poem ‘War Photographer’ by Caroline Duffy and the poem ‘Remains’ by Simon Armitage both explore the theme of conflict by both being about wars and the aftermath of the wars, and the guilt felt after the war. Both authors weren’t involved with war, but both poems are written about war.

In the poem, ‘War Photographer’ conflict is presented using metaphors, imagery and adjectives. Duffy does this by creating detailed images of what happened by using vocabulary that has connotations of war and violence. She also uses sibilance, Duffy also uses these techniques to create a semantic field of a priest by the way she uses metaphors and also by the way she shows how the photographer is dedicated to his job, similarly to how a priest would be. Also, by the way, Duffy refers to the old testament in the first paragraph. Duffy also doesn’t specify what war it is, so the reader could associate it with any war. Contrastingly in the poem ‘Remains’ by Armitage, conflict is presented in a similar way, using metaphors and creating semantic fields. Both poems use imagery to depict the aftermath and trauma it had on the soldier and photographer, this poem is also a dramatic monologue written in the third person.

In ‘War Photographer’ Duffy presents the theme of conflict with the metaphor; ‘Spools of suffering set out in ordered rows.’ This metaphor tells the reader about what the war photographer has to do for his job and how he feels about it. The word ‘suffering’ links back to conflict because of the connotations it brings. Also, the harsh alliterative sibilant of 's' sounds in 'spools' and 'suffering' establish the negative mood. The photos, like war graves, are set out in a uniform fashion, and also the juxtaposition of ‘spools’ and ‘ordered’ suggests that the photographer has to put these photos in ‘order’ to make sense of all the suffering he has seen. Duffy uses the quote ‘The only light is red and softly glows as though this were a church and he a priest preparing to intone a Mass’ to create a semantic field of a church, red could be referring to blood, including that of Christ. Also, Duffy could be comparing the photographer to a priest because a priest is exposed to suffering and death, and so is he, a priest has an important job, and so does he. The quote; ‘into foreign dust’ is a reference to ‘all are from dust and dust we shall return’ this quote gives the poem appropriate solemnity. Another religious quote in this poem is ‘all flesh is grass’, this is referring to the old testament and keeps the religious theme going throughout the play, this quote has a rhyming couplet, this rhyme scheme is also used earlier on in the poem, with the words ‘rows’ and ‘glows’ and also with the words ‘Mass’ and ‘grass’. The couplets suggest tightness and restraint. It implies that the photographer has to keep his emotions in check while on the job, but falls apart when he is back at his home. The adjectives that Duffy uses that have connotations of war and conflict are; ‘suffering’, ‘explode’, ‘nightmare’ and ‘blood’. These adjectives all link back to war, conflict and violence, the writer uses imagery throughout the poem in the quotes; ‘a strangers features faintly start to twist before his eyes, a half-formed ghost’ and ‘he remembers the cries of this man’s wife’ and ‘Solutions slop in trays beneath his hands, which did not tremble then though seem to now’ , showing the reader that even though he is back in ‘Rural England’ he can't escape the memories, and how he has to block out what he feels at the moment, but the memories then haunt him later on.

This is a preview of the whole essay

Contrastingly, the poem ‘Remains’ links to conflict as well by using repetition and adjectives that link back to conflict and violence. Armitage uses juxtaposition to shock the reader of this poem, by creating a sharp contrast between the casual conversational tone of the opening stanza and a sudden violent statement. Armitage uses dramatic contrasts to the serious nature of death and war as if the person speaking in the poem finds it hard to process the events that have happened in an adult manner, so then proceeds to process it in a child-like manner. The writer also makes a reference to Macbeth in the poem, to show how guilty the guy in this poem feels

In ‘Remains’ Armitage presents the theme of conflict in repetition, you can see this by the way Armitage repeats the words ‘all three’ as if the person whom this poem was written about finds it hard to take full responsibility for the death of the man he shot, he also uses repetition with the quote; ‘I see’ as if he is recalling what happened from his mind, and he can’t get the memory out of his head. The poem tells the reader that he can’t get the image out of his head in the quote; ‘and the drink and drugs won't flush him out’ this quote shows the reader how conflict has affected him mentally. Armitage also uses adjectives that create connotations of violence, the adjectives he uses are; ‘bloody’, ‘pain’, ‘agony’ that all link back to conflict. Juxtaposition is used when Armitage goes from casual conversational tone to a sudden violent statement. It goes from ‘on another occasion, we get sent out to tackle looters raiding a bank’ to ‘so all three of us open fire’ Armitage could have done this to shock the reader, and show the reader how quickly death can occur in a war zone but how the memory of it lasts a lifetime. Armitage doesn’t name the war in this poem, so the reader could associate this poem with any war. Armitage uses dramatic contrasts to the serious nature of death and war, this shows the reader that the person in this poem finds it hard to process the events that have happened in an adult-like way so they process it in a childlike way, we can see this in the quotes; ; ‘three of a kind’ which is a poker reference, which may suggest the games of childhood or of young men. We also see a dramatic contrast in the quote; ‘tosses his guts back into his body’ because the word ‘toss’ is not an appropriate word that should be used for a dead body. The quote; 'bloody hands', which could be a reference to Macbeth because he couldn't get the blood off his hands no matter how many time she washed them.

Overall I think both poems link back to conflict and are similar because they both include juxtaposition. Duffy uses juxtaposition to create imagery and Armitage uses juxtaposition to shock the reader and create imagery. Both poems give detailed images of what happened, and both present someone who is having a hard time dealing with the guilt of war. Both poems are unnamed warfares and the reader could associate the poem with any war. Both poems are monologues which make it more effective. Both poems present conflict through war, although they are from two different perspectives, as ‘War Photographer’ is in the third person and ‘Remains’ is in the first person. Also in ‘Remains’, the conflict is actually committed by him, whereas in ‘War Photographer’ the conflict it photographed by him, this could be two completely different experiences with similar emotions. Both poems make the reader think about the problems that this world has, and also could make the reader melancholy, because of what is described throughout the poems.

Document Details

- Author Type Student

- Word Count 1283

- Page Count 3

- Subject English

- Type of work Homework assignment

Related Essays

How is inner conflict shown in Simon Armitage's "Remains" and "War Photogra...

Consider how relationships are presented in Harmonium by Simon Armitage and...

Comparison essay of 'Flag' by John Agard and 'Out of the blue' by Simon Arm...

Compare how the use of war imagery is presented in 'Nettles' and Manhunt

- International

- Schools directory

- Resources Jobs Schools directory News Search

THE EMIGREE COMPARISON LESSON- COMPARED WITH CHECKING OUT, EXPOSURE, WAR PHOTOGRAPHER &THE PRELUDE

Subject: English

Age range: 14-16

Resource type: Lesson (complete)

Last updated

13 May 2023

- Share through email

- Share through twitter

- Share through linkedin

- Share through facebook

- Share through pinterest

HIGH QUALITY POETRY TEACHING / REVISION RESOURCE

Inspire your students to compare imaginatively!!!

This resource uses The Emigree by Rumens to model comparing poems in a step by step way, with differentation opportunities.

This includes - a full essay plan for The Emigree and Checking Out Me History and thoughtful, varied points and quotes comparing The Emigree with-

Exposure War Photographer The Prelude

It’s not exactly a lesson- no objectives, plenary etc, but I spent a really long time making the essay plans and coming up with interesting, varied comparisons and when I used it with my class it definitely inspired them to think about all the poems in different and more thorough ways.

I hope it’s useful :)

Tes paid licence How can I reuse this?

Your rating is required to reflect your happiness.

It's good to leave some feedback.

Something went wrong, please try again later.

This resource hasn't been reviewed yet

To ensure quality for our reviews, only customers who have purchased this resource can review it

Report this resource to let us know if it violates our terms and conditions. Our customer service team will review your report and will be in touch.

Not quite what you were looking for? Search by keyword to find the right resource:

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

In Exposure the realisation about the brutal reality of war arises in the midst of a war zone; however, in War Photograph this realisation is made by the photographer when he reaches the relative comfort of home. Point 1 for EXPOSURE notion of suffering. n Exposure, the narrator speaks of how the soldiers "brains aches, in the merciless iced ...

Grade 9 GCSE Essay - AQA - June 2019 Compare how poets present the ways that people are affected by war in 'War Photographer' and in one other poem from 'Power and Conflict'. In 'War Photographer', the protagonist appears to have become inured and desensitised to the horrors of war. ... In 'War Photographer', there is a semantic ...

Throughout both of the poems 'Exposure' by Wilfred Owen and 'War Photographer' by Carol Ann Duffy there is an exploration of personal experience of conflict, with both poets depicting the ideas of the lack of purpose behind conflict, its aftermath on the individual and the collective alike, and also the indifference of the wider world towards individual human suffering.

In both poems, "War Photographer" by Duffy and "Exposure" by Owen, poets illustrate their suffering and acrimony of conditions of war. "War Photographer" is an inspiration of the friendship of the poet with a photographer of war. It is also an illustration of the brutality of war and the apathy of those who might see the photos in newspapers.

GCSE Grade 9 AQA Power and Conflict Poetry Essay - Comparing Simon Armitage's 'Remains' with Carol Ann Duffy's 'War Photographer'.You can also access this co...

Different perspectives in each poem present a contrasting view of the reality of war. The first-person plural narration in 'Exposure', such as in "Our brains ache" gives the conflict a greater sense of realism, as the soldiers' experience of war is presented first-hand. As a serving soldier, Owen was a strong critic of World War One and the

Example high level comparison of War Photographer and Exposure. Save money by purchasing as part of a bundle of grade 9 responses: ... I was looking for comparing Exposure and War Photographer and while the essay is as reported, the writing frame is clearly a copy and paste resource as it refers to multiple poems seemingly randomly. ...

War Photographer. Carole Satyamurti was a British poet who also worked as a translator and sociologist. Her works include ' War Photographer .'. 'War Photographer' by Carole Satyamurti centers around the tragic, comparing poverty to leisure. The poet, Carole Satyamurti, is known for facing pain and suffering head-on in her works of poetry.

and presented is seamlessly smooth, innovative, and comprehensive." "War Photographer" is a poem by Scottish writer Carol Ann Duffy, the United Kingdom's poet laureate from 2009 to 2019. Originally published in 1985, "War Photographer" depicts the experiences of a photographer who returns home to England to develop the hundreds of photos he has ...

File previews. key, 3.81 MB. AQA comparison lesson with essay plan and grade 9 models on Exposure (Wilfred Owen) and War Photographer (Carol Ann Duffy) Tes paid licence How can I reuse this?

(This post contains two detailed videos on the topic.) Previously, I wrote a post analysing Wilfred Owen's 'Insensibility' and Carol Ann Duffy's 'War Photographer', which are about apathy towards war.In this post, we're ramping up the volume by looking at stronger feelings towards war, such as despair and nihilism.

Similarities. Both poems consider the effects of war. Both poets are angry about what has happened. Both poems were written at a time when war was dominating the news - Owen's during World War ...

A copy of the essay can be downloaded here: Poppies vs War Photographer. Why I love…Comparing AQA poems a series: Ozymandias and My Last Duchess. Why I love…Comparing Poems: AQA Extract from the Prelude and Storm on the Island. Why I love…Comparing Poems: AQA Exposure by Owen with Storm on the Island by Heaney

Both 'War Photographer' and 'Remains' explore guilt. In the third stanza of War Photographer, Duffy makes the photographer's guilt clear by writing that he sees a 'half-formed ghost' when he develops one of the photographs. Duffy's imagery in the words 'half-formed' helps the reader to imagine the photograph slowly ...

'Remains' could be compared to World War One poem, 'Exposure' You can discover a lot about a poem by comparing it to one by another author that deals with a similar subject. You could compare ...

Owen personifies the weather and nature throughout the poem. This technique depicts nature as the antagonist in the poem and an even bigger threat than the actual army the soldiers are meant to be fighting. The weather "knives" the men and uses "stealth" to attack them. The air "shudders black with snow".

While Duffy's War Photographer uses a detached, third-person voice, Weir chooses a nostalgic and emotional first-person reflection in Poppies to portray the wide-reaching impact of conflict. Evidence and analysis. War Photographer. Poppies. Duffy distances the reader by telling the story of a photographer in a dark-room in third-person narration.

Age range: 11-14. Resource type: Lesson (complete) File previews. pptx, 1.44 MB. PNG, 213.35 KB. A lesson with the key focus of supporting students for the GCSE poetry compare question. (Has been used for online lessons) Challenging their thinking with comparing 'Exposure' and 'War Photographer'. This is easily adaptable to support top ...

Overall, despite the fact that both War Photographer and Poppies show to the reader that the effects of war and conflict are uncontrollable, War Photographer focuses less on how emotions can overcome your conscience, and more on the idea that people are separating themselves from the suffering and struggles, whereas Poppies focuses on how those who are not directly involved in war are ...

Age range: 14-16. A grade 9 model response comparing the impact of war in Exposure and Poppies. Includes examiner annotations (by an AQA examiner) and a summative comment justifying the grade against the mark scheme. Useful reading for all students with the potential for grade 9. For weaker students attempting this question there are planning ...

In 'War Photographer' Duffy presents the theme of conflict with the metaphor; 'Spools of suffering set out in ordered rows.' This metaphor tells the reader about what the war photographer has to do for his job and how he feels about it. The word 'suffering' links back to conflict because of the connotations it brings.

Compare the way the poets present the after effects of conflict in 'Kamikaze' and 'War Photographer'. Grade 9 GCSE AQA English Literature Poetry- War Photographer and Kamikaze Essay. Clearly structured in the format required of the AQA mark scheme. Clear topic sentences, grade 9 analysis of quotes, varied subject terminology and ...

Inspire your students to compare imaginatively!!! This resource uses The Emigree by Rumens to model comparing poems in a step by step way, with differentation opportunities. This includes - a full essay plan for The Emigree and Checking Out Me History and thoughtful, varied points and quotes comparing The Emigree with-Exposure War Photographer