Advertisement

Homework and Children in Grades 3–6: Purpose, Policy and Non-Academic Impact

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 12 January 2021

- Volume 50 , pages 631–651, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Melissa Holland ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8349-7168 1 ,

- McKenzie Courtney 2 ,

- James Vergara 3 ,

- Danielle McIntyre 4 ,

- Samantha Nix 5 ,

- Allison Marion 6 &

- Gagan Shergill 1

18k Accesses

8 Citations

127 Altmetric

16 Mentions

Explore all metrics

Increasing academic demands, including larger amounts of assigned homework, is correlated with various challenges for children. While homework stress in middle and high school has been studied, research evidence is scant concerning the effects of homework on elementary-aged children.

The objective of this study was to understand rater perception of the purpose of homework, the existence of homework policy, and the relationship, if any, between homework and the emotional health, sleep habits, and parent–child relationships for children in grades 3–6.

Survey research was conducted in the schools examining student ( n = 397), parent ( n = 442), and teacher ( n = 28) perception of homework, including purpose, existing policy, and the childrens’ social and emotional well-being.

Preliminary findings from teacher, parent, and student surveys suggest the presence of modest impact of homework in the area of emotional health (namely, student report of boredom and frustration ), parent–child relationships (with over 25% of the parent and child samples reporting homework always or often interferes with family time and creates a power struggle ), and sleep (36.8% of the children surveyed reported they sometimes get less sleep) in grades 3–6. Additionally, findings suggest misperceptions surrounding the existence of homework policies among parents and teachers, the reasons teachers cite assigning homework, and a disconnect between child-reported and teacher reported emotional impact of homework.

Conclusions

Preliminary findings suggest homework modestly impacts child well-being in various domains in grades 3–6, including sleep, emotional health, and parent/child relationships. School districts, educators, and parents must continue to advocate for evidence-based homework policies that support children’s overall well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Parental Educational Expectations and Academic Achievement in Children and Adolescents—a Meta-analysis

Martin Pinquart & Markus Ebeling

Social Media Addiction in High School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study Examining Its Relationship with Sleep Quality and Psychological Problems

Adem Sümen & Derya Evgin

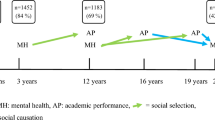

Mental health and academic performance: a study on selection and causation effects from childhood to early adulthood

Sara Agnafors, Mimmi Barmark & Gunilla Sydsjö

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Children’s social-emotional health is moving to the forefront of attention in schools, as depression, anxiety, and suicide rates are on the rise (Bitsko et al. 2018 ; Child Mind Institute 2016 ; Horowitz and Graf 2019 ; Perou et al. 2013 ). This comes at a time when there are also intense academic demands, including an increased focus on academic achievement via grades, standardized test scores, and larger amounts of assigned homework (Pope 2010 ). This interplay between the rise in anxiety and depression and scholastic demands has been postulated upon frequently in the literature, and though some research has looked at homework stress as it relates to middle and high school students (Cech 2008 ; Galloway et al. 2013 ; Horowitz and Graf 2019 ; Kackar et al. 2011 ; Katz et al. 2012 ), research evidence is scant as to the effects of academic stress on the social and emotional health of elementary children.

Literature Review

The following review of the literature highlights areas that are most pertinent to the child, including homework as it relates to achievement, the achievement gap, mental health, sleep, and parent–child relationships. Areas of educational policy, teacher training, homework policy, and parent-teacher communication around homework are also explored.

Homework and Achievement

With the authorization of No Child Left Behind and the Common Core State Standards, teachers have felt added pressures to keep up with the tougher standards movement (Tokarski 2011 ). Additionally, teachers report homework is necessary in order to complete state-mandated material (Holte 2015 ). Misconceptions on the effectiveness of homework and student achievement have led many teachers to increase the amount of homework assigned. However, there has been little evidence to support this trend. In fact, there is a significant body of research demonstrating the lack of correlation between homework and student success, particularly at the elementary level. In a meta-analysis examining homework, grades, and standardized test scores, Cooper et al. ( 2006 ) found little correlation between the amount of homework assigned and achievement in elementary school, and only a moderate correlation in middle school. In third grade and below, there was a negative correlation found between the variables ( r = − 0.04). Other studies, too, have evidenced no relationship, and even a negative relationship in some grades, between the amount of time spent on homework and academic achievement (Horsley and Walker 2013 ; Trautwein and Köller 2003 ). High levels of homework in competitive high schools were found to hinder learning, full academic engagement, and well-being (Galloway et al. 2013 ). Ironically, research suggests that reducing academic pressures can actually increase children’s academic success and cognitive abilities (American Psychological Association [APA] 2014 ).

International comparison studies of achievement show that national achievement is higher in countries that assign less homework (Baines and Slutsky 2009 ; Güven and Akçay 2019 ). In fact, in a recent international study conducted by Güven and Akçay ( 2019 ), there was no relationship found between math homework frequency and student achievement for fourth grade students in the majority of the countries studied, including the United States. Similarly, additional homework in science, English, and history was found to have little to no impact on respective test scores in later grades (Eren and Henderson 2011 ). In the 2015 “Programme of International Student Assessment” results, Korea and Finland are ranked among the top countries in reading, mathematics, and writing, yet these countries are among those that assign the least amount of homework (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD] 2016 ).

Homework and Mental Wellness

Academic stress has been found to play a role in the mental well-being of children. In a study conducted by Conner et al. ( 2009 ), students reported feeling overwhelmed and burdened by their exceeding homework loads, even when they viewed homework as meaningful. Academic stress, specifically the amount of homework assigned, has been identified as a common risk factor for children’s increased anxiety levels (APA 2009 ; Galloway et al. 2013 ; Leung et al. 2010 ), in addition to somatic complaints and sleep disturbance (Galloway et al. 2013 ). Stress also negatively impacts cognition, including memory, executive functioning, motor skills, and immune response (Westheimer et al. 2011 ). Consequently, excessive stress impacts one’s ability to think critically, recall information, and make decisions (Carrion and Wong 2012 ).

Homework and Sleep

Sleep, including quantity and quality, is one life domain commonly impacted by homework and stress. Zhou et al. ( 2015 ) analyzed the prevalence of unhealthy sleep behaviors in school-aged children, with findings suggesting that staying up late to study was one of the leading risk factors most associated with severe tiredness and depression. According to the National Sleep Foundation ( 2017 ), the recommended amount of sleep for elementary school-aged children is 9 – 11 h per night; however, approximately 70% of youth do not get these recommended hours. According to the MetLife American Teacher Survey ( 2008 ), elementary-aged children also acknowledge lack of sleep. Perfect et al. ( 2014 ) found that sleep problems predict lower grades and negative student attitudes toward teachers and school. Eide and Showalter ( 2012 ) conducted a national study that examined the relationship between optimum amounts of sleep and student performance on standardized tests, with results indicating significant correlations ( r = 0.285–0.593) between sleep and student performance. Therefore, sleep is not only impacted by academic stress and homework, but lack of sleep can also impact academic functioning.

Homework and the Achievement Gap

Homework creates increasing achievement variability among privileged learners and those who are not. For example, learners with more resources, increased parental education, and family support are likely to have higher achievement on homework (Hofferth and Sandberg 2001 ; Moore et al. 2018 ; Ndebele 2015 ; OECD 2016 ). Learners coming from a lower socioeconomic status may not have access to quiet, well-lit environments, computers, and books necessary to complete their homework (Cooper 2001 ; Kralovec and Buell 2000 ). Additionally, many homework assignments require materials that may be limited for some families, including supplies for projects, technology, and transportation. Based on the research to date, the phrase “the homework gap” has been coined to describe those learners who lack the resources necessary to complete assigned homework (Moore et al. 2018 ).

Parent–Teacher Communication Around Homework

Communication between caregivers and teachers is essential. Unfortunately, research suggests parents and teachers often have limited communication regarding homework assignments. Markow et al. ( 2007 ) found most parents (73%) report communicating with their child’s teacher regarding homework assignments less than once a month. Pressman et al. ( 2015 ) indicated children in primary grades spend substantially more time on homework than predicted by educators. For example, they found first grade students had three times more homework than the National Education Association’s recommendation of up to 20 min of homework per night for first graders. While the same homework assignment may take some learners 30 min to complete, it may take others up to 2 or 3 h. However, until parents and teachers have better communication around homework, including time completion and learning styles for individual learners, these misperceptions and disparities will likely persist.

Parent–Child Relationships and Homework

Trautwein et al. ( 2009 ) defined homework as a “double-edged sword” when it comes to the parent–child relationship. While some parental support can be construed as beneficial, parental support can also be experienced as intrusive or detrimental. When examining parental homework styles, a controlling approach was negatively associated with student effort and emotions toward homework (Trautwein et al. 2009 ). Research suggests that homework is a primary source of stress, power struggle, and disagreement among families (Cameron and Bartel 2009 ), with many families struggling with nightly homework battles, including serious arguments between parents and their children over homework (Bennett and Kalish 2006 ). Often, parents are not only held accountable for monitoring homework completion, they may also be accountable for teaching, re-teaching, and providing materials. This is particularly challenging due to the economic and educational diversity of families. Pressman et al. ( 2015 ) found that as parents’ personal perceptions of their abilities to assist their children with homework declined, family-related stressors increased.

Teacher Training

As homework plays a significant role in today’s public education system, an assumption would be made that teachers are trained to design homework tasks to promote learning. However, only 12% of teacher training programs prepare teachers for using homework as an assessment tool (Greenberg and Walsh 2012 ), and only one out of 300 teachers reported ever taking a course regarding homework during their training (Bennett and Kalish 2006 ). The lack of training with regard to homework is evidenced by the differences in teachers’ perspectives. According to the MetLife American Teacher Survey ( 2008 ), less experienced teachers (i.e., those with 5 years or less years of experience) are less likely to to believe homework is important and that homework supports student learning compared to more experienced teachers (i.e., those with 21 plus years of experience). There is no universal system or rule regarding homework; consequently, homework practices reflect individual teacher beliefs and school philosophies.

Educational and Homework Policy

Policy implementation occurs on a daily basis in public schools and classrooms. While some policies are made at the federal level, states, counties, school districts, and even individual school sites often manage education policy (Mullis et al. 2012 ). Thus, educators are left with the responsibility to implement multi-level policies, such as curriculum selection, curriculum standards, and disability policy (Rigby et al. 2016 ). Despite educational reforms occurring on an almost daily basis, little has been initiated with regard to homework policies and practices.

To date, few schools provide specific guidelines regarding homework practices. District policies that do exist are not typically driven by research, using vague terminology regarding the quantity and quality of assignments. Greater variations among homework practices exist when comparing schools in the private sector. For example, Montessori education practices the philosophy of no examinations and no homework for students aged 3–18 (O’Donnell 2013 ). Abeles and Rubenstein ( 2015 ) note that many public school districts advocate for the premise of 10 min of homework per night per grade level. However, there is no research supporting this premise and the guideline fails to recognize that time spent on homework varies based on the individual student. Sartain et al. ( 2015 ) analyzed and evaluated homework policies of multiple school districts, finding the policies examined were outdated, vague, and not student-focused.

The reasons cited for homework assignment, as identified by teachers, are varied, such as enhancing academic achievement through practice or teaching self-discipline. However, not all types of practice are equally effective, particularly if the student is practicing the skill incorrectly (Dean et al. 2012 ; Trautwein et al. 2009 ). The practice of reading is one of the only assignments consistently supported by research to be associated with increased academic achievement (Hofferth and Sandberg 2001 ). Current literature supports 15–20 min of daily allocated time for reading practice (Reutzel and Juth 2017 ). Additionally, research supports project-based learning to deepen learners’ practice and understanding of academic material (Williams 2018 ).

Research also shows that homework only teaches responsibility and self-discipline when parents have that goal in mind and systematically structure and supervise homework (Kralovec and Buell 2000 ). Non-academic activities, such as participating in chores (University of Minnesota 2002 ) and sports (Hofferth and Sandberg 2001 ) were found to be greater predictors of later success and effective problem-solving.

Consistent with the pre-existing research literature, the following hypotheses are offered:

Homework will have some negative correlation with children’s social-emotional well-being.

The purposes cited for the assignment of homework will be varied between parents and teachers.

Schools will lack well-formulated and understood homework policies.

Homework will have some negative correlation with children’s sleep and parent–child relationships.

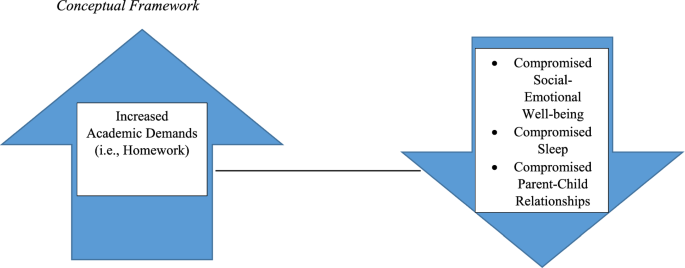

This quantitative study explored, via perception-based survey research, the social and emotional health of elementary children in grades 3 – 6 and the scholastic pressures they face, namely homework. The researchers implemented newly developed questionnaires addressing student, teacher, and parent perspectives on homework and on children’s social-emotional well-being. Researchers also examined perspectives on the purpose of homework, the existence of school homework policies, and the perceived impact of homework on children’s sleep and family relationships. Given the dearth of prior research in this area, a major goal of this study was to explore associations between academic demands and child well-being with sufficient breadth to allow for identification of potential associations that may be examined more thoroughly by future research. These preliminary associations and item-response tendencies can serve as foundation for future studies with causal, experimental, or more psychometrically focused designs. A conceptual framework for this study is offered in Fig. 1 .

Conceptual framework

Research Questions

What is the perceived impact of homework on children’s social-emotional well-being across teachers, parents, and the children themselves?

What are the primary purposes of homework according to parents and teachers?

How many schools have homework policies, and of those, how many parents and teachers know what the policy is?

What is the perceived impact of homework on children’s sleep and parent–child relationships?

The present quantitative descriptive study is based on researcher developed instruments designed to explore the perceptions of children, teachers and parents on homework and its impact on social-emotional well-being. The use of previously untested instruments and a convenience sample preclude any causal interpretations being drawn from our results. This study is primarily an initial foray into the sparsely researched area of the relationship of homework and social-emotional health, examining an elementary school sample and incorporating multiple perspectives of the parents, teachers, and the children themselves.

Participants

The participants in this study were children in six Northern California schools in grades third through sixth ( n = 397), their parents ( n = 442), and their teachers ( n = 28). The mean grade among children was 4.56 (minimum third grade/maximum sixth grade) with a mean age of 9.97 (minimum 8 years old/maximum 12 years old). Approximately 54% of the children were male and 45% were female, with White being the most common ethnicity (61%), followed by Hispanic (30%), and Pacific Islander (12%). Subjects were able to mark more than one ethnicity. Detailed participant demographics are available upon request.

Instruments

The instruments used in this research include newly developed student, parent, and teacher surveys. The research team formulated a number of survey items that, based on existing research and their own professional experience in the schools, have high face validity in measuring workload, policies, and attitudes surrounding homework. Further psychometric development of these surveys and ascertation of construct and content validity is warranted, with the first step being their use in this initial perception-based study. Each of the surveys, developed specifically for this study, are discussed below.

Student Survey

The Student Survey is a 15-item questionnaire wherein the child was asked closed- and open-ended questions regarding their perspectives on homework, including how homework makes them feel.

Parent Survey

The Parent Survey is a 23-item questionnaire wherein the children’s parents were asked to respond to items regarding their perspectives on their child’s homework, as well as their child’s social-emotional health. Additionally, parents were asked whether their child’s school has a homework policy and, if so, if they know what that policy specifies.

Teacher Survey

The Teacher Survey is a 22-item questionnaire wherein the children’s teacher was asked to respond to items regarding their perspectives of the primary purposes of homework, as well as the impact of homework on children’s social-emotional health. Additionally, teachers were asked whether their school has a homework policy and, if so, what that policy specifies.

Data was collected by the researchers after following Institutional Review Board procedures from the sponsoring university. School district approval was obtained by the lead researcher. Upon district approval, individual school approval was requested by the researchers by contacting site principals, after which, teachers of grades 3 – 6 at those schools were asked to voluntarily participate. Each participating teacher was provided a packet including the following: a manila envelope, Teacher Instructions, Administration Guide, Teacher Survey, Parent Packet, and Student Survey. Surveys and classrooms were de-identified via number assignment. Teachers then distributed the Parent Packet to each child’s guardian, which included the Parent Consent and Parent Survey, corresponding with the child’s assigned number. A coded envelope was also enclosed for parents/guardians to return their completed consent form and survey, if they agreed to participate. The Parent Consent form detailed the purpose of the research, the benefits and risks of participating in the research, confidentiality, and the voluntary nature of completing the survey. Parents who completed the consent form and survey sent the completed materials in the enclosed envelope, sealed, to their child’s teacher. After obtaining returned envelopes, with parent consent, teachers were instructed to administer the corresponding numbered survey to the children during a class period. Teachers were also asked to complete their Teacher Survey. All completed materials were to be placed in envelopes provided to each teacher and returned to the researchers once data was collected.

Analysis of Data

This descriptive and quantitative research design utilized the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) to analyze data. The researchers developed coding keys for the parent, teacher, and student surveys to facilitate data entry into SPSS. Items were also coded based on the type of data, such as nominal or ordinal, and qualitative responses were coded and translated where applicable and transcribed onto a response sheet. Some variables were transformed for more accurate comparison across raters. Parent, teacher, and student ratings were analyzed, and frequency counts and percentages were generated for each item. Items were then compared across and within rater groups to explore the research questions. The data analysis of this study is primarily descriptive and exploratory, not seeking to imply causal relationships between variables. Survey item response results associated with each research questionnaire are summarized in their respective sections below.

The first research question investigated in this study was: “What is the perceived impact of homework on children’s social-emotional well-being across teachers, parents, and children?” For this question the examiners looked at children’s responses to how homework makes them feel from a list of feelings. As demonstrated in Table 1 , approximately 44% of children feel “Bored” and about 25% feel “Annoyed” and “Frustrated” toward homework. Frequencies and percentages are reported in Table 1 . Similar to the student survey, parents also responded to a question regarding their child’s emotional experience surrounding homework. Based on parent reports, approximately 40% of parents perceive their child as “Frustrated” and about 37% acknowledge their child feeling “Stress/Anxiety.” Conversely, about 37% also report their child feels “Competence.” These results are reported in Table 1 .

Additionally, parents and teachers both responded to the question, “How does homework affect your student’s social and emotional health?” One notable finding from parent and teacher reports is that nearly half of both parents and teachers reported homework has “No Effect” on children’s social and emotional health. Frequencies and percentages are reported in Table 2 .

The second research question investigated in this study was: “What are parent and teacher perspectives on the primary purposes of homework?” For this question the examiners looked at three specific questions across parent and teacher surveys. Parents responded to the questions, “Does homework relate to your child’s learning?” and “How often is homework busy work?” While the majority of parents reported homework “Always” (45%) or “Often” (39%) relates to their child’s learning, parents also feel homework is “Often” (29%) busy work. The corresponding frequencies and percentages are summarized in Table 3 . Additionally, teachers were asked, “What are the primary reasons you assign homework?” The primary purposes of homework according to the teachers in this sample are “Skill Practice” (82%), “Develop Work Ethic” (61%), and “Teach Independence and Responsibility” (50%). The frequencies and percentages of teacher responses are displayed in Table 4 . Notably, on this survey item, teachers were instructed to choose one response (item), but the majority of teachers chose multiple items. This suggests teachers perceive themselves as assigning homework for a variety of reasons.

The third research question investigated was, “How many schools have homework policies, and of those, how many parents and teachers know what the policy is?” For this question the examiners analyzed parent and teacher responses to the question, “Does your school have a homework policy?” Frequencies and percentages are displayed in Table 5 . Notably, only two out of the six schools included in this study had homework policies. Results indicate that both parents and teachers are uncertain regarding whether or not their school had a homework policy.

The fourth research question investigated was, “What is the perceived impact of homework on children’s sleep and parent–child relationships?” Children were asked if they get less sleep because of homework and parents were asked if their child gets less sleep because of homework. Finally, teachers were asked about the impact of sleep on academic performance. Frequencies and percentages of student, parent, and teacher data is reported in Table 6 . Results indicate disagreement among parents and children on the impact of homework on sleep. While the majority of parents do not feel their child gets less sleep because of homework (77%), approximately 37% of children report sometimes getting less sleep because of homework. On the other hand, teachers acknowledge the importance of sleep in relation to academic performance, as nearly 93% of teachers report sleep always or often impacts academic performance.

To investigate the perceived impact of homework on the parent–child relationship, parents were asked “How does homework impact your child’s relationships?” Almost 30% of parents report homework “Brings us Together”; however, 24% report homework “Creates a Power Struggle” and nearly 18% report homework “Interferes with Family Time.” Additionally, parents and children were both asked to report if homework gets in the way of family time. Frequencies and percentages are reported in Table 7 . Data was further analyzed to explore potentially significant differences between parents and children on this perception as described below.

In order to prepare for analysis of significant differences between parent and child perceptions regarding homework and family time, a Levene’s test for equality of variances was conducted. Results of the Levene’s test showed that equal variances could not be assumed, and results should be interpreted with caution. Despite this, a difference in mean responses on a Likert-type scale (where higher scores equal greater perceived interference with family time) indicate a disparity in parent ( M = 2.95, SD = 0.88) and child ( M = 2.77, SD = 0.99) perceptions, t (785) = 2.65, p = 0.008. Results suggest that children were more likely to feel that homework interferes with family time than their parents. However, follow up testing where equal variances can be assumed is warranted upon further data collection.

The purpose of this research was to explore perceptions of homework by parents, children, and teachers of grades 3–6, including how homework relates to child well-being, awareness of school homework policies and the perceived purpose of homework. A discussion of the results as it relates to each research question is explored.

Perceived Impact of Homework on Children’s Social-Emotional Well-Being Across Teachers, Parents, and Students

According to self-report survey data, children in grades 3–6 reported that completing homework at home generates various feelings. The majority of responses indicated that children felt uncomfortable emotions such as bored, annoyed, and frustrated; however, a subset of children also reported feeling smart when completing homework. While parent and teacher responses suggest parents and teachers do not feel homework affects children’s social-emotional health, children reported that homework does affect how they feel. Specifically, many children in this study reported experiencing feelings of boredom and frustration when thinking about completing homework at home. If the purpose of homework is to enhance children’s engagement in their learning outside of school, educators must re-evaluate homework assignments to align with best practices, as indicated by the researchers Dean et al. ( 2012 ), Vatterott ( 2018 ), and Sartain et al. ( 2015 ). Specifically, educators should consider effects of the amount and type of homework assigned, balancing the goal of increased practice and learning with potential effects on children’s social-emotional health. Future research could incorporate a control group and/or test scores or other measures of academic achievement to isolate and better understand the relationships between homework, health, and scholastic achievement.

According to parent survey data, the perceived effects of homework on their child’s social and emotional well-being appear strikingly different compared to student perceptions. Nearly half of the parents who participated in the survey reported that homework does not impact their child’s social-emotional health. Additionally, more parents indicated that homework had a positive effect on child well-being compared to a negative one. However, parents also acknowledge that homework generates negative emotions such as frustration, stress and anxiety in their children.

Teacher data indicates that, overall, teachers do not appear to see a negative impact on their students’ social-emotional health from homework. Similar to parent responses, nearly half of teachers report that homework has no impact on children’s social-emotional health, and almost one third of teachers reported a positive effect. These results are consistent with related research which indicates that teachers often believe that homework has positive impacts on student development, such as developing good study habits and a sense of responsibility (Bembenutty 2011 ). It should also be noted, not a single teacher reported the belief that homework negatively impacts children’s’ social and emotional well-being, which indicates clear discrepancies between teachers’ perceptions and children’s feelings. Further research is warranted to explore and clarify these discrepancies.

Primary Purposes of Homework According to Teachers and Parents

Results from this study suggest that the majority of parents believe that homework relates and contributes to their child’s learning. This finding supports prior research which indicates that parents often believe that homework has long-term positive effects and builds academic competencies in students (Cooper et al. 2006 ). Notably, however, nearly one third of parents also indicate that homework is often given as busy work by teachers. Teachers reported that they assigned homework to develop students’ academic skills, work ethic, and teach students responsibility and promote independence. While teachers appear to have good intentions regarding the purpose of homework, research suggests that homework is not an effective nor recommended practice to achieve these goals. Household chores, cooking, volunteer experiences, and sports may create more conducive learning opportunities wherein children acquire work ethic, responsibility, independence, and problem-solving skills (Hofferth and Sandberg 2001 ; University of Minnesota 2002 ). Educators should leverage the use of homework in tandem with other student life experiences to best foster both academic achievement and positive youth development more broadly.

Homework Policies

As evident from parent responses, the majority of parents are unaware if their child’s school has a homework policy and many teachers are also uncertain as to whether their school provides restrictions or guidelines for homework (e.g., amount, type, and purpose). Upon contacting school principals, it was determined that only two of the six schools have a school-wide homework policy. Current data indicates the professionals responsible for assigning homework appear to be unclear about whether their school has policies for homework. Additionally, there appears to be a disconnect between parents and teachers regarding whether homework policies do exist among the sampled schools. The research in the current study is consistent with previous research indicating that policies, if they do exist, are often vague and not communicated clearly to parents (Sartain et al. 2015 ). This study suggests that homework policies in these districts require improved communication between administrators, teachers, and parents.

Perceived Impact of Homework on Children’s Sleep and Parent–Child Relationships

Regarding the importance of sleep on academic performance, nearly all of the teachers included in this study acknowledged the impact that sleep has on academic performance. There was disagreement among children and parents on the actual impact that homework has on children’s sleep. Over one third of children report that homework occasionally detracts from their sleep; however, many parents may be unaware of this impact as more than three quarters of parents surveyed reported that homework does not impact their child’s sleep. Thus, while sleep is recognized as highly important for academic achievement, homework may be adversely interfering with students’ full academic potential by compromising their sleep.

In regard to homework’s impact on the parent child-relationship, parents in this survey largely indicated that homework does not interfere in their parent–child relationship. However, among the parents who do notice an impact, the majority report that homework can create a power struggle and diminish their overall family time. These results are consistent with Cameron and Bartell’s ( 2009 ) research which found that parents often believe that excessive amounts of homework often cause unnecessary family stress. Likewise, nearly one third of children in this study reported that homework has an impact on their family time.

This study provides the foundation for additional research regarding the impact of academic demands, specifically homework, on children’s social-emotional well-being, including sleep, according to children, parents, and teachers. Additionally, the research provides some information on reasons teachers assign homework and a documentation of the lack of school homework policies, as well as the misguided knowledge among parents and teachers about such policies.

The preexisting literature and meta-analyses indicate homework has little to no positive effect on elementary-aged learners’ academic achievement (Cooper et al. 2006 ; Trautwein and Köller 2003 ; Wolchover 2012 ). This led to the question, if homework is not conducive to academic achievement at this level, how might it impact other areas of children’s lives? This study provides preliminary information regarding the possible impact of homework on the social-emotional health of elementary children. The preliminary conclusions from this perception research may guide districts, educators, and parents to advocate for evidence-based homework policies that support childrens’ academic and social-emotional health. If homework is to be assigned at the elementary level, Table 8 contains recommended best practices for such assignment, along with a sample of specific guidelines for districts, educators, and parents (Holland et al. 2015 ).

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Due to the preliminary nature of this research, some limitations must be addressed. First, research was conducted using newly developed parent, teacher, and student questionnaires, which were not pilot tested or formally validated. Upon analyzing the data, the researchers discovered limitations within the surveys. For example, due to the nature of the survey items, the variables produced were not always consistently scaled. This created challenges when making direct comparisons. Additionally, this limited the sophistication of the statistical procedures that could be used, and reliability could not be calculated in typical psychometric fashion (e.g., Cronbach’s Alpha). Secondly, the small sample size may limit the generalizability of the results, especially in regard to the limited number of teachers (n = 28) we were able to survey. Although numerous districts and schools were contacted within the region, only three districts granted permission. These schools may systematically differ from other schools in the region and therefore do not necessarily represent the general population. Third, this research is based on perception, and determining the actual impacts of homework on child wellness would necessitate a larger scale, better controlled study, examining variables beyond simple perception and eliminating potentially confounding factors. It is possible that individuals within and across rater groups interpreted survey items in different ways, leading to inconsistencies in the underlying constructs apparently being measured. Some phrases such as “social-emotional health” can be understood to mean different things by different raters, which could have affected the way raters responded and thus the results of this study. Relatedly, causal links between homework and student social-emotional well-being cannot be established through the present research design and future research should employ the use of matched control groups who do not receive homework to better delineate the direct impact of homework on well-being. Finally, interpretations of the results are limited by the nested nature of the data (parent and student by teacher). The teachers, parents, and students are not truly independent groups, as student and parent perceptions on the impact of homework likely differ as a function of the classroom (teacher) that they are in, as well as the characteristics of the school they attend, their family environment, and more. The previously mentioned challenge of making direct comparisons across raters due to the design of the surveys, as well as small sample size of teachers, limited the researchers’ ability to address this issue. Future research may address this limitation by collecting data and formulating related lines of inquiry that are more conducive to the analysis of nested data. At this time, this survey research is preliminary. An increased sample size and replication of results is necessary before further conclusions can be made. Researchers should also consider obtaining data from a geographically diverse population that mirrors the population in the United States, and using revised surveys that have undergone a rigorous validation process.

Abeles, V., & Rubenstein, G. (2015). Beyond measure: Rescuing an overscheduled, overtested, underestimated generation . New York: Simon & Schuster.

Google Scholar

American Psychological Association (APA). (2009). Stress in America 2009 . https://bit.ly/39FiTk3 .

American Psychological Association (APA). (2014). Stress in America: Are teens adopting adults’ stress habits? https://bit.ly/2SIiurC .

Baines, L. A., & Slutsky, R. (2009). Developing the sixth sense: Play. Educational HORIZONS , 87 (2), 97–101. https://bit.ly/39LLGU4 .

Bembenutty, H. (2011). The last word: An interview with harris cooper—Research, policies, tips, and current perspectives on homework. Journal of Advanced Academics, 22 (2), 340–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X1102200207 .

Article Google Scholar

Bennett, S., & Kalish, N. (2006). The case against homework: How homework is hurting our children and what we can do about it . New York: Crown Publishers.

Bitsko, R. H., Holbrook, J. R., Ghandour, R. M., Blumberg, S. J., Visser, S. N., Perou, R., & Walkup, J. T. (2018). Epidemiology and impact of health care provider:Diagnosed anxiety and depression among US children. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 39 (5), 395. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000571 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cameron, L., & Bartell, L. (2009). The researchers ate the homework! Toronto: Canadian Education Association.

Carrion, V. G., & Wong, S. S. (2012). Can traumatic stress alter the brain? Understanding the implications of early trauma on brain development and learning. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51 (2), S23–S28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.04.010 .

Cech, S. J. (2008). Poll of US teens finds heavier homework load, more stress over grades. Education Week, 27 (45), 9.

Child Mind Institute. Children’s mental health report . (2015). https://bit.ly/2SSzE4v .

Child Mind Institute. (2016). 2016 children’s mental health report . https://bit.ly/2SQ9kbj .

Conner, J., Pope, D., & Galloway, M. (2009). Success with less stress. Educational Leadership, 67, 54–58.

Cooper, H. (2001). Homework for all–in moderation. Educational leadership, 58 (7), 34–38.

Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987–2003. Review of Educational Research, 76 (1), 1–62. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543076001001 .

Dean, C. B., Hubbell, E. R., Pitler, H., & Stone, B. J. (2012). Classroom instruction that works: Research-based strategies for increasing student achievement . Alexandria: ASCD.

Eide, E. R., & Showalter, M. H. (2012). Sleep and student achievement. Eastern Economic Journal, 38 (4), 512–524. https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2011.33 .

Eren, O., & Henderson, D. J. (2011). Are we wasting our children’s time by giving them more homework? Economics of Education Review, 30 (5), 950–961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.03.011 .

Galloway, M., Conner, J., & Pope, D. (2013). Nonacademic effects of homework in privileged, high-performing high schools. The Journal of Experimental Education, 81 (4), 490–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2012.745469 .

Greenberg, J., & Walsh, K. (2012). What teacher preparation programs teach about k-12 assessment: A review . Washington: National Council on Teacher Quality.

Güven, U., & Akçay, A. O. (2019). Trends of homework in mathematics: Comparative research based on TIMSS study. International Journal of Instruction., 12 (1), 1367–1382.

Hofferth, S. L., & Sandberg, J. F. (2001). How American children spend their time. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63 (2), 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00295.x .

Holland, M. L., Sisson, H., & Abeles, V. (2015, January). Academic demands, homework, and social–emotional health. NASP Communique, 45 (5), 10.

Holte, K. (2015). Homework in primary school: Could it be made more child-friendly? Studia Paedagogica, 21 (4), 13–33. https://doi.org/10.5817/SP2016-4-1 .

Horowitz, J. M., & Graf, N. (2019). Most U.S. teens see anxiety and depression as a major problem among their peers. Pew Research Center. https://pewrsr.ch/32kUmhU .

Horsley, M., & Walker, R. (2013). Reforming homework: Practices, learning and policies . South Yarra: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kackar, H. Z., Shumow, L., Schmidt, J. A., & Grzetich, J. (2011). Age and gender differences in adolescents’ homework experiences. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32 (2), 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2010.12.005 .

Katz, I., Buzukashvili, T., & Feingold, L. (2012). Homework stress: Construct validation of a measure. The Journal of Experimental Education, 80 (4), 405–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2011.610389 .

Kralovec, E., & Buell, J. (2000). The end of homework: How homework disrupts families, overburdens children, and limits learning . Boston: Beacon Press.

Leung, G. S., Yeung, K. C., & Wong, D. F. (2010). Academic stressors and anxiety in children: The role of paternal support. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19 (1), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9288-4 .

Markow, D., Kim, A., & Liebman, M. (2007). The Metlife survey of the American teacher . New York: Metlife, Inc. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED530021.pdf .

MetLife. (2008). MetLife American teacher survey grades the state of homework . (ED500012). https://www.metlife.com/aboutus/newsroom/2008/february/metlife-american-teacher-survey-grades-the-state-of-homework/ .

Moore, R., Vitale, D., & Stawinoga, N. (2018). The digital divide and educational equity: A look at students with very limited access to electronic devices at home (Insights in Education and Work) . Iowa City: ACT Inc.

Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Minnich, C. A., Stanco, G. M., Arora, A., & Centurino, V. A. S. (2012). TIMSS 2011 encyclopedia: Education policy and curriculum in mathematics and science (Vols. 1, 2). Chestnut Hill, MA: TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Boston College. https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2011/encyclopedia-timss.html .

National Sleep Foundation. (2017). How much sleep do babies and kids need? https://bit.ly/37E157D .

Ndebele, M. (2015). Socio-economic factors affecting parents’ involvement in homework: Practices and perceptions from eight Johannesburg public primary schools. Perspectives in Education, 33 (3), 72–91.

O’Donnell, M. (2013). Maria Montessori: A critical introduction to key themes and debates . Bloomsbury Academic: Bloomsbury Academic.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2016). PISA 2015 results in focus. https://bit.ly/2T1NUb0 .

Perfect, M. M., Levine-Donnerstein, D., Archbold, K., Goodwin, J. L., & Quan, S. F. (2014). The contribution of sleep problems to academic and psychosocial functioning. Psychology in the Schools, 51 (3), 273–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21746 .

Perou, R., Bitsko, R. H., Blumberg, S. J., Pastor, R., Ghandour, R. M., Gfroerer, J. C., et al. (2013). Mental health surveillance among children: United States, 2005–2011. MMWR, 62 (2), 1–35.

Pope, D. (2010). Beyond ‘doing school’: From ‘stressed-out’ to ‘engaged in learning.’ Education Canada, 50 (1), 4–8.

Pressman, R. M., Sugarman, D. B., Nemon, M. L., Desjarlais, J., Owens, J. A., & Schettini-Evans, A. (2015). Homework and family stress: With consideration of parents’ self-confidence, educational level, and cultural background. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 43 (4), 297–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2015.1061407 .

Reutzel, D. R., & Juth, S. (2017). Supporting the development of silent reading fluency: An evidence-based framework for the intermediate grades (3–6). International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 7 (1), 27–46.

Rigby, J. G., Woulfin, S. L., & März, V. (2016). Understanding how structure and agency influence education policy implementation and organizational change. American Journal of Education, 122 (3), 295–302. https://doi.org/10.1086/685849 .

Sartain, C., Glenn, L., Jones, J., Merritt, D., (2015). A policy analysis of district homework policies [Doctoral dissertation, Saint Louis University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. https://bit.ly/2vSDxOT .

Sisson, H. F. (2015). Academic demands on the social-emotional health of primary and secondary grade students [Master’s thesis, California State University, Sacramento]. Sacramento State Scholarworks. https://bit.ly/2vNyMGq .

Tokarski, J. E. (2011). Thoughtful homework or busywork: Impact on student success [Master’s thesis, Dominican University of California]. Dominican Scholar. https://bit.ly/38UrQWw .

Trautwein, U., & Köller, O. (2003). The relationship between homework and achievement: Still much of a mystery. Educational Psychology Review, 15 (2), 115–145. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023460414243 .

Trautwein, U., Niggli, A., Schnyder, I., & Lüdtke, O. (2009). Between-teacher differences in homework assignments and the development of students’ homework effort, homework emotions, and achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101 (1), 176–189. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.101.1.176 .

University of Minnesota (2002). Involving children in household tasks: Is it worth the effort . https://bit.ly/2TkcUe7

Vatterott, C. (2018). Rethinking homework: Best practices that support diverse needs (2nd ed.). Alexandria: ASCD.

Westheimer, K., Abeles, V., & Truebridge, S. (2011). End the race: A facilitation guide and companion resource to the film race to nowhere . Reel Link Films. https://bit.ly/2T1FG2D .

Williams, D. L. (2018). The impact of project-based learning on fourth-grade students’ understanding in reading. [Doctoral dissertation, Capella University] ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. https://bit.ly/2SIjvzD .

Wolchover, N. (2012, March 30). Too much homework can lower test scores, researchers say. Huffington Post . https://bit.ly/38EdJoi .

Zhou, Y., Siu, A. F., & Wai, S. T. (2015). Influences of unhealthy sleep behaviors on the excessive daytime sleepiness and depressive symptoms in children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24 (7), 2120–2126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-0013-6 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

College of Education, California State University, 6000 J Street, Sacramento, CA, 95819, USA

Melissa Holland & Gagan Shergill

Buckeye Union School District, 5049 Robert J. Mathews Parkway, El Dorado Hills, CA, 95762, USA

McKenzie Courtney

Institute for Social Research, CSUS, 304 S Street, Suite 333, Sacramento, CA, 95811, USA

James Vergara

Dry Creek Joint Elementary School District, 8849 Cook Riolo Road, Roseville, CA, 95747, USA

Danielle McIntyre

Natomas Unified School District, 1901 Arena Blvd, Sacramento, CA, 95834, USA

Samantha Nix

Panama-Buena Vista Union School District, 4200 Ashe Rd, Bakersfield, CA, 93313, USA

Allison Marion

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by all authors. All authors contributed on this first draft and on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Melissa Holland .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

Ethics approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board at the sponsoring university. This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the sponsoring university. Data was collected by the researchers after following the IRB procedures. This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Consent to Participate

Consent forms used in this research available upon request addressed to the corresponding author.

Access to Data and Material

Available upon request addressed to the corresponding author.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Holland, M., Courtney, M., Vergara, J. et al. Homework and Children in Grades 3–6: Purpose, Policy and Non-Academic Impact. Child Youth Care Forum 50 , 631–651 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-021-09602-8

Download citation

Accepted : 05 January 2021

Published : 12 January 2021

Issue Date : August 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-021-09602-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Social emotional health

- Elementary students

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Homework should not take longer than 50 minutes.*

Students will have math homework almost every night except Friday. It is due the following day.

Read for 20 minutes each week night, this includes time spent on assigned articles

When students are absent, the class work will be given to the student upon their return to class. They are also responsible for the homework they missed.

Sometimes a special project will take the place of typical homework

*If homework takes longer than allotted time please reach out and discuss with your child's teacher

- Elizabeth M. Baker Elementary School

- John F. Kennedy Elementary School

- Lakeville Elementary School

- Parkville School

- Saddle Rock Elementary School

- Richard S. Sherman - Great Neck North Middle School

- Great Neck South Middle School

- John L. Miller - Great Neck North High School

- William A. Shine - Great Neck South High School

- Village School

- Adult Learning Center

- Community Education

Where Discovery Leads to Greatness

Page Navigation

- Ms. Etra's Important Information

- Ms. Frey's Important Information

- Ms. Gordon's Important Information

- Ms. Laby's Important Information

- Ms. Meisel's Important Information

- Ms. Mino's Important Information

- Ms. Seiden's Important Information

- Ms. Weiss's Important Information

- Health Curriculum

- Literacy Curriculum

- Mathematics Curriculum

- Science Curriculum

- Social Studies Curriculum

- Social Emotional Learning Curriculum

- Grade 3 Homework Policy

- Grade 3 Supply List

Homework Guidelines

Lakeville School

Why Homework is Assigned:

Reinforces and/or extends skills and material that have been taught in class

Helps students develop independence, responsibility, and effective study habits

Serves as a communication link between school and home

Helps teachers assess student learning

When Homework Will Be Assigned:

Monday through Thursday

Types of homework assigned:

Math nightly

Language arts

20-30 minutes reading nightly

Student’s Homework Responsibilities:

Students should make homework a priority

Should turn in neat, proofread, completed on time assignments

Students should be responsible for making up missed assignments

Parent’s Homework Responsibilities:

Parents should make sure child has a place at home to do their work

Parents should inform teacher when child is unable to complete homework on their own

Parents may help child (explain assignment-not do work) when needed and inform teacher that help was needed

Teacher’s Homework Responsibilities:

Homework will be reviewed in a timely manner

Students Do Not Hand In Properly Completed Homework:

The teacher will address missing assignments with the child and handle each case on an individual basis

- Questions or Feedback? |

- Web Community Manager Privacy Policy (Updated) |

- Pine Valley Central School

Home of the Panthers

- Homework Policy

- Questions or Feedback? |

- Web Community Manager Privacy Policy (Updated) |

Homework and the Third-Grader

If your son has a problem with his homework, teach him to reread the directions and study any examples of how the work is to be done. If this is not sufficient help, advise him to study textbook explanations of the assignment. Do not jump in to help him until he has taken these steps, and you will have given your son a valuable study skill.

You are right to be concerned about teaching your child good study habits. Schools don't always teach children how to handle their work. Here are some suggestions for you:

- Have your child use an assignment notebook so he knows what homework is required each day.

- Introduce a planning calendar and show your son how to use it when he begins to have long-term assignments.

- Help your child learn how to organize his study time. Each day he should preview the assignments that he has to do and get the tough tasks out of the way first. He should write down the order in which he will do assignments.

- Teach your child to review his work frequently.

- Get your child an organizer, and show him how to use it so that he has a system for organizing all his school papers.

- Have your child use a book bag to transport books and papers.

- Encourage your child to establish a regular time for doing homework.

- Your son should keep old quizzes and tests to prepare for future tests.

- Eliminate distractions such as phone calls and television during homework time.

- Establish a regular place for doing homework. One book that will give you insight into homework and teaching study skills to your child is How To Help Your Child With Homework published by Free Spirit Publishing.

Please note: This "Expert Advice" area of FamilyEducation.com should be used for general information purposes only. Advice given here is not intended to provide a basis for action in particular circumstances without consideration by a competent professional. Before using this Expert Advice area, please review our General and Medical Disclaimers.

3rd Grade Policies

Grade 3 Policies

DISCIPLINE

Students are expected to show appropriate behavior during school. Appropriate behavior includes following directions, respecting others, and being involved in learning activities. We have set up a policy that is used in both of our classrooms. This discipline policy consists of three steps. If class or school rules are broken, then the consequences below will be given within one school day:

2. Second offense, a “Think Sheet” will be sent home to be completed with parents, signed, and brought back to school the next day.

3. Third offense, a detention will be given to student and phone call made to parents.

INCENTIVE PROGRAM

We feel it is important to praise our students for all the great things they do, such as getting a compliment from a teacher or Miss Lang for walking quietly in the hall, working well during centers, helping each other clean up spilt crayons, etc. We feel it is important for the children to have a reward to work toward so they will want to do great things as a class. Each class votes on a reward when the jar is empty so they can know what prize they are working toward. We will then drop marbles into a jar to keep track of all these great actions. When the jar is full we will enjoy the prize we worked so hard for!

THIRD GRADE HOMEWORK POLICY

Why we assign homework: We believe homework is important because it is a valuable aid in helping reinforce what students learned in class. Homework prepares students for future lessons, teaches responsibility, and helps develop positive study habits.

When we assign homework: Homework may be assigned Monday through Thursday nights. There are times when optional homework will be assigned on weekends, such as reviewing for an upcoming test. Assignments should take no longer than 30 minutes a night, including 15 minutes of reading, which can be done silently or aloud with someone.

Student homework responsibilities: We expect students to do their best on homework assigned to them. We expect homework assignments to be neat and not sloppy. Students are expected to try their best on the assignment before asking for help at home.

If a Student DOES NOT Complete Homework

If a student fails to do a homework assignment, they will receive a homework slip. This homework slip is used to inform you that your child did not finish or complete the assignment, or did the assignment incorrectly. A parent will need to sign the homework slip and the student is required to bring the finished/correct assignment to school the next day. It is the student’s responsibility to turn the assignment in with the signed homework slip.

If a student receives 3 homework slips in a quarter, a Life Skill will be sent home.

If a student receives 5 homework slips in a quarter, a contact home will be made, and the student will need to serve a 45 min. detention.

Each Quarter students will go back to having zero homework slips.

Parent homework responsibilites: Parents play an important role in making homework a positive experience for their children! Therefore, we ask that parents make homework a top priority, provide necessary supplies and a quiet environment, set a daily work time, provide praise and support, not let children avoid homework, and contact us if they notice a problem. Thank you in advance for all you do to help your child succeed in school!

READING AT HOME

Remember that as a third grader, we ask that your child spend 15 minutes or 15 pages a night with a book, magazine, or a newspaper. This reading material should be age appropriate and “just right” text. Your child will learn this rule in third grade.

Everyday at 2:45pm, we fill in our homework for the day in our Agenda as a class. We will then check each child’s Agenda to help him/her be successful with homework that evening. Parents are encouraged to use the Agenda as a communication tool with teachers. Transportation changes still need a separate note and please send any money to school in an envelope with your child’s name and homeroom on it, as well as what the money is designated for written clearly on the envelope. Thank you!

Your child is encouraged to bring in a healthy snack daily to be enjoyed mid-morning. This snack should be quick and something that can be eaten by hand. No juice boxes, please, but children are allowed and encouraged to bring in a water bottle. Examples of healthly snacks include: apple slices, a granola bar, cheese and crackers, grapes, or carrot sticks. Sugary snacks are discouraged. *No nuts or peanut butter to protect our youngsters with allergies. Thanks for helping us keep our brains alert and ready to learn!

SUMMER BIRTHDAYS If your child celebrated a birthday in the summer, do not fear! The office recognizes these students throughout the year. It is up to you when you would like to celebrate your child’s summer birthday, whether at his/her half birthday or in June. Please let us know which you prefer. You can see the handbook for more details regarding birthday treats.

THIRD GRADE ASSESSMENT PROGRAM

It is our goal that your child meets the standards of Grade 3, and begins to exceed or apply these learned skills even further. Grading will be much like what you have seen in the past few years, with rubrics to help explain what is expected for students to maintain a “+” and a “check.” Please see the St. Brendan Handbook to view the Diocesan Progress Report Codes in detail.

TERRA NOVA TESTING

Terra Nova Testing will be in October 17th-21st. More information will be sent home about your child taking the Terra Nova test closer to the time.

SPECIAL’S SCHEDULES

3B Specials:

3A Specials:

Recess: 11:10-11:30

Lunch: 11:30-11:55

Third grade is an exciting year for students. They are exposed to more information and are becoming independent learners, although some parent supervision is still expected. With the support of caring parents and teachers, your child will develop a lifelong love of learning and make third grade a successful year!

Mrs. Jennifer Gressman

- Check the school website for: Calendar, Lunch Menu, Contact information

Reading & Math for K-5

- Kindergarten

- Learning numbers

- Comparing numbers

- Place Value

- Roman numerals

Subtraction

Multiplication

- Order of operations

- Drills & practice

Measurement

- Factoring & prime factors

- Proportions

- Shape & geometry

- Data & graphing

- Word problems

- Children's stories

- Leveled Stories

- Context clues

- Cause & effect

- Compare & contrast

- Fact vs. fiction

- Fact vs. opinion

- Main idea & details

- Story elements

- Conclusions & inferences

- Sounds & phonics

- Words & vocabulary

- Reading comprehension

- Early writing

- Numbers & counting

- Simple math

- Social skills

- Other activities

- Dolch sight words

- Fry sight words

- Multiple meaning words

- Prefixes & suffixes

- Vocabulary cards

- Other parts of speech

- Punctuation

- Capitalization

- Narrative writing

- Opinion writing

- Informative writing

- Cursive alphabet

- Cursive letters

- Cursive letter joins

- Cursive words

- Cursive sentences

- Cursive passages

- Grammar & Writing

Breadcrumbs

Download & Print From only $3.10

Third Grade Math Worksheets

Free grade 3 math worksheets.

Our third grade math worksheets support numeracy development and introduce division, decimals, roman numerals, calendars and concepts in measurement and geometry. Our word problem worksheets review skills in real world scenarios.

Choose your grade 3 topic:

Place Value and Rounding

Order of Operations

Roman Numerals

Fractions and Decimals

Counting Money

Time & Calendar

Data & Graphing

Word Problems

Sample Grade 3 Math Worksheet

What is K5?

K5 Learning offers free worksheets , flashcards and inexpensive workbooks for kids in kindergarten to grade 5. Become a member to access additional content and skip ads.

Our members helped us give away millions of worksheets last year.

We provide free educational materials to parents and teachers in over 100 countries. If you can, please consider purchasing a membership ($24/year) to support our efforts.

Members skip ads and access exclusive features.

Learn about member benefits

This content is available to members only.

Join K5 to save time, skip ads and access more content. Learn More

- Forgot Password?

All Formats

Resource types, all resource types.

- Rating Count

- Price (Ascending)

- Price (Descending)

- Most Recent

Free 3rd grade homework

Multiplication and Division Facts | Cross-Number Puzzles | Jungle

Earth Day Reading Comprehension Passages and Questions Activities Bundle

Equivalent Fractions Worksheets 3.NF - Comparing Fractions On a Number Line

Earth Day Activity Bundle - Fun Earth Day Class Party Games - After Spring Break

Double Digit Addition and Subtraction With & Without Regrouping

Place Value Worksheets 2nd Grade Math Practice - Number Sense Activities - FREE

Contraction Cut and Paste #2

2nd Grade Fluency Homework Sampler (FREE) Reading Comprehension Passages

It's Raining Idioms - A Figurative Language Activity

Prefix and Suffix (Freebie)

Determining the Main Idea, Task Cards and Assessment Option

2 Digit Multiplication Practice Worksheets Using Standard Algorithm FREE

Irregular Past Tense Verb Worksheets

Paragraph of the Week | Paragraph Writing Practice | Google Classroom FREE

12 Days of Christmas Math Word Problems - FREE! - Fun No-Prep Worksheets

- Easel Activity

FREE Monthly Reading Logs

Nouns, Verbs and Adjectives - Fill In The Blanks

- Google Apps™

3rd Grade Math Spiral Review | Morning Work | Homework | Free

3rd Grade Math Spiral Review & Quizzes | FREE

FREE Telling Time Worksheets

Comparing Fractions Worksheets - Free 4th Grade Math

Fact Fluency: Mixed Addition and Subtraction Facts within 20

Add and Subtract Fractions with Like and Unlike Denominators - PRINT and DIGITAL

Free Equivalent Fractions on a Number Line

Telling Time and Elapsed Time Free Sample

Text Detectives- Find the Text Evidence FREEBIE Sampler!

Even and Odd Numbers Worksheets / Printables for Kindergarten, Grade One / Two

Place Value Worksheets FREEBIE 3 Digit Place Value

- We're hiring

- Help & FAQ

- Privacy policy

- Student privacy

- Terms of service

- Tell us what you think

- Akron Central Schools

Dedicated to excellence in education

- First Grade Homework Policy

1 - Miss Knapp

Page navigation.

- Classroom Rules

Homework may include the following: Reading - examples: listening to a story, child reading a story to others Review Vocabulary words (flash cards) frequently Practice math facts Worksheets Assignments not completed in school Missed assignments due to absences

Homework should be returned on time. There will be consequences for work not returned. (Ex. loss of playtime, staying after school, etc.) If there is ever a reason that your child is unable to complete his/her homework when it is due, just write a note and we will work something out.

The purpose of homework is to reinforce and strengthen skills that have been introduced and taught in the classroom. It also helps children develop a sense of responsibility and set priorities. Parents and students alike can see the growth made over time and celebrate the accomplishments. We appreciate your cooperation.

- Questions or Feedback? |

- Web Community Manager Privacy Policy (Updated) |

- Our Mission

A Late Work Policy That Works for Teachers and Students

Creating clear boundaries around when students can submit assignments after the due date can boost morale for everyone.

When the end of a term approaches, educator social media is full of images and commentary on the sheer amount of grading that will be coming their way. From images of monstrous waves or an exhausted teacher grasping a large cup of coffee, the stress is palpable. So how do we make this better for everyone, including teachers, students, families, case coordinators, and everyone else struggling at the end of the term?

As educators, we want to be considerate of the fact that students have yet to acquire excellent management skills. But we also need to protect our own mental health and teach students the responsibility that comes with completing assignments and turning in work.

Designing a Late Work Policy With Students

Some years back, I had a high school world language class with a wonderful group of students—but getting work from them was challenging on a good day. After one particularly exhausting end of the term when I received a monumental amount of late work, I flatly said, “We can’t do this again.” Shockingly, they agreed. I gave the class 30 minutes to discuss as a class what they thought could be a fair policy. The requirements were simple:

1. Simplicity. This policy had to be easy for me to manage as a teacher.

2. Accountability. It couldn’t be a free-for-all with no accountability.

I could easily write a separate article on how to have students design class policies, but that is for a different time. Here is what the students came up with as a proposal:

Assessment as final deadline: All homework and classwork is accepted full credit until the assessment—then it is not accepted at all. This also counts for any retakes (or corrections) to other activities or smaller assessments.

The 55 percent rule: If a student does the large majority of the assignments up until assessment, they do not get less than 55 percent on any assessment. This gives students an incentive to get their work done and make arrangements with the teacher to keep on track. It should be very unlikely that a student will do the majority of assignments related to an assessment and get below 55 percent. However, if it does happen, they know that there are policies in place to help them.

If a student does get below 55 percent and has done the large majority of the work, this forces me as an educator to consider the cause. Did other students have similar troubles? If so, was the assessment reflective of the work done in class? If this student was an outlier, perhaps they simply had a rough day (which does happen)?

Assessment as proof of competency: If a student is missing an assignment and they get above a certain score on the assessment, they can get partial credit for any missing work related to the assessment. The students were very clear that this was not a reason to not do work, but rather it was to allow students to focus on critical assignments if they get behind.

Assessment as redo attempt: If a student does well on a final unit assessment, they can have their grade raised for smaller assessments leading up to that larger one. This was because they showed understanding in areas where they had struggled before.

Once this policy was created, I shared it with all my sections. Students overwhelmingly supported it. So, we decided to implement it on a trial basis. Once that was a success, I shared this with colleagues, and they implemented it in their classrooms as well. It is now a regular course policy and is shared in all of my course syllabi.

a policy that works for teachers and students

After we set this policy up in my classroom, I observed a variety of benefits.

Morale boost for teacher and students: There was an immediate turnaround for both me and my students. Students who felt that failure was inevitable were motivated and engaged. And I felt better about giving students another chance-–but with boundaries.

Increased accountability: Students held each other accountable for their own success and admitted when they were not putting in their effort. Parents were highly supportive; it was clear why a student was not successful, and this saved a lot of time responding to parent emails.

Better-quality work: Work was less rushed, which led to better quality, deeper learning, and stronger assessment scores. Students told me they had often rushed through work so it wouldn’t be marked late, but this gave them time to do quality work and therefore learn in the process.

Students did the work: Very few students used the “proof of competency policy” as a chance to simply not do work. Rather, this policy helped students prioritize missing work if they got really behind. Although I worried that this policy might be taken advantage of, only a small handful of students tried—and they realized very quickly that this was not a recipe for success.

Range of grades: There was still a wide range of grades. Highly skilled students who had an excellent understanding of the content still earned excellent grades. Those who struggled earned grades that weren’t quite as high, but they felt empowered with the recognition of their efforts.

So why does this policy work? I believe there are two main reasons. The first is assurance. Provided they do “their part,” students feel that they can be successful and are assured that their efforts do matter. If they make mistakes, life events make submitting work challenging, or the content gets particularly hard for them, there are structures in place to help them. Second, there is a sense of control for the students. Students crave the opportunity to have control over their future, and they are able to recognize what is fair and how they (and their classmates) should be held accountable for their responsibilities.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Third Grade Homework Policy Homework will be assigned on a daily basis depending upon the skills needing reinforcement from classroom lessons. Third grade students need a homework folder to keep their assignments. Students have a daily assignment log to help them remain organized and remember what their assignments are.

Third Grade Homework Policy. In compliance with Greenbrier's homework policy, third grade students will be assigned 30 minutes of homework Monday through Thursday. No homework will be given on Friday. Homework will be assigned in the following areas: *Reading. Math °Word Study *Reading homework will consist of reading and comprehension activities.

3rd Grade Homework Policy and Info. Homework Planners/Agendas: Third graders will be given a homework planner/agenda in which they are to record their daily assignments. All assignments are announced in class and written on the homework board. Under careful guidance of the adults in the classroom, each child is expected to independently fill ...