21 Action Research Examples (In Education)

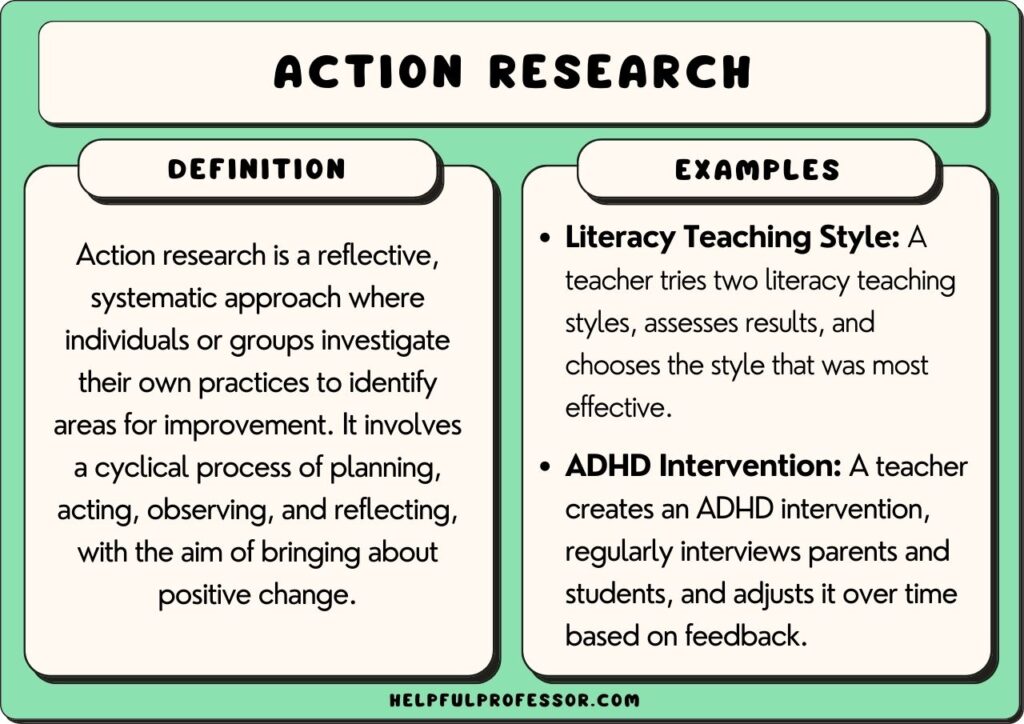

Action research is an example of qualitative research . It refers to a wide range of evaluative or investigative methods designed to analyze professional practices and take action for improvement.

Commonly used in education, those practices could be related to instructional methods, classroom practices, or school organizational matters.

The creation of action research is attributed to Kurt Lewin , a German-American psychologist also considered to be the father of social psychology.

Gillis and Jackson (2002) offer a very concise definition of action research: “systematic collection and analysis of data for the purpose of taking action and making change” (p.264).

The methods of action research in education include:

- conducting in-class observations

- taking field notes

- surveying or interviewing teachers, administrators, or parents

- using audio and video recordings.

The goal is to identify problematic issues, test possible solutions, or simply carry-out continuous improvement.

There are several steps in action research : identify a problem, design a plan to resolve, implement the plan, evaluate effectiveness, reflect on results, make necessary adjustment and repeat the process.

Action Research Examples

- Digital literacy assessment and training: The school’s IT department conducts a survey on students’ digital literacy skills. Based on the results, a tailored training program is designed for different age groups.

- Library resources utilization study: The school librarian tracks the frequency and type of books checked out by students. The data is then used to curate a more relevant collection and organize reading programs.

- Extracurricular activities and student well-being: A team of teachers and counselors assess the impact of extracurricular activities on student mental health through surveys and interviews. Adjustments are made based on findings.

- Parent-teacher communication channels: The school evaluates the effectiveness of current communication tools (e.g., newsletters, apps) between teachers and parents. Feedback is used to implement a more streamlined system.

- Homework load evaluation: Teachers across grade levels assess the amount and effectiveness of homework given. Adjustments are made to ensure a balance between academic rigor and student well-being.

- Classroom environment and learning: A group of teachers collaborates to study the impact of classroom layouts and decorations on student engagement and comprehension. Changes are made based on the findings.

- Student feedback on curriculum content: High school students are surveyed about the relevance and applicability of their current curriculum. The feedback is then used to make necessary curriculum adjustments.

- Teacher mentoring and support: New teachers are paired with experienced mentors. Both parties provide feedback on the effectiveness of the mentoring program, leading to continuous improvements.

- Assessment of school transportation: The school board evaluates the efficiency and safety of school buses through surveys with students and parents. Necessary changes are implemented based on the results.

- Cultural sensitivity training: After conducting a survey on students’ cultural backgrounds and experiences, the school organizes workshops for teachers to promote a more inclusive classroom environment.

- Environmental initiatives and student involvement: The school’s eco-club assesses the school’s carbon footprint and waste management. They then collaborate with the administration to implement greener practices and raise environmental awareness.

- Working with parents through research: A school’s admin staff conduct focus group sessions with parents to identify top concerns.Those concerns will then be addressed and another session conducted at the end of the school year.

- Peer teaching observations and improvements: Kindergarten teachers observe other teachers handling class transition techniques to share best practices.

- PTA surveys and resultant action: The PTA of a district conducts a survey of members regarding their satisfaction with remote learning classes.The results will be presented to the school board for further action.

- Recording and reflecting: A school administrator takes video recordings of playground behavior and then plays them for the teachers. The teachers work together to formulate a list of 10 playground safety guidelines.

- Pre/post testing of interventions: A school board conducts a district wide evaluation of a STEM program by conducting a pre/post-test of students’ skills in computer programming.

- Focus groups of practitioners : The professional development needs of teachers are determined from structured focus group sessions with teachers and admin.

- School lunch research and intervention: A nutrition expert is hired to evaluate and improve the quality of school lunches.

- School nurse systematic checklist and improvements: The school nurse implements a bathroom cleaning checklist to monitor cleanliness after the results of a recent teacher survey revealed several issues.

- Wearable technologies for pedagogical improvements; Students wear accelerometers attached to their hips to gain a baseline measure of physical activity.The results will identify if any issues exist.

- School counselor reflective practice : The school counselor conducts a student survey on antisocial behavior and then plans a series of workshops for both teachers and parents.

Detailed Examples

1. cooperation and leadership.

A science teacher has noticed that her 9 th grade students do not cooperate with each other when doing group projects. There is a lot of arguing and battles over whose ideas will be followed.

So, she decides to implement a simple action research project on the matter. First, she conducts a structured observation of the students’ behavior during meetings. She also has the students respond to a short questionnaire regarding their notions of leadership.

She then designs a two-week course on group dynamics and leadership styles. The course involves learning about leadership concepts and practices . In another element of the short course, students randomly select a leadership style and then engage in a role-play with other students.

At the end of the two weeks, she has the students work on a group project and conducts the same structured observation as before. She also gives the students a slightly different questionnaire on leadership as it relates to the group.

She plans to analyze the results and present the findings at a teachers’ meeting at the end of the term.

2. Professional Development Needs

Two high-school teachers have been selected to participate in a 1-year project in a third-world country. The project goal is to improve the classroom effectiveness of local teachers.

The two teachers arrive in the country and begin to plan their action research. First, they decide to conduct a survey of teachers in the nearby communities of the school they are assigned to.

The survey will assess their professional development needs by directly asking the teachers and administrators. After collecting the surveys, they analyze the results by grouping the teachers based on subject matter.

They discover that history and social science teachers would like professional development on integrating smartboards into classroom instruction. Math teachers would like to attend workshops on project-based learning, while chemistry teachers feel that they need equipment more than training.

The two teachers then get started on finding the necessary training experts for the workshops and applying for equipment grants for the science teachers.

3. Playground Accidents

The school nurse has noticed a lot of students coming in after having mild accidents on the playground. She’s not sure if this is just her perception or if there really is an unusual increase this year. So, she starts pulling data from the records over the last two years. She chooses the months carefully and only selects data from the first three months of each school year.

She creates a chart to make the data more easily understood. Sure enough, there seems to have been a dramatic increase in accidents this year compared to the same period of time from the previous two years.

She shows the data to the principal and teachers at the next meeting. They all agree that a field observation of the playground is needed.

Those observations reveal that the kids are not having accidents on the playground equipment as originally suspected. It turns out that the kids are tripping on the new sod that was installed over the summer.

They examine the sod and observe small gaps between the slabs. Each gap is approximately 1.5 inches wide and nearly two inches deep. The kids are tripping on this gap as they run.

They then discuss possible solutions.

4. Differentiated Learning

Trying to use the same content, methods, and processes for all students is a recipe for failure. This is why modifying each lesson to be flexible is highly recommended. Differentiated learning allows the teacher to adjust their teaching strategy based on all the different personalities and learning styles they see in their classroom.

Of course, differentiated learning should undergo the same rigorous assessment that all teaching techniques go through. So, a third-grade social science teacher asks his students to take a simple quiz on the industrial revolution. Then, he applies differentiated learning to the lesson.

By creating several different learning stations in his classroom, he gives his students a chance to learn about the industrial revolution in a way that captures their interests. The different stations contain: short videos, fact cards, PowerPoints, mini-chapters, and role-plays.

At the end of the lesson, students get to choose how they demonstrate their knowledge. They can take a test, construct a PPT, give an oral presentation, or conduct a simulated TV interview with different characters.

During this last phase of the lesson, the teacher is able to assess if they demonstrate the necessary knowledge and have achieved the defined learning outcomes. This analysis will allow him to make further adjustments to future lessons.

5. Healthy Habits Program

While looking at obesity rates of students, the school board of a large city is shocked by the dramatic increase in the weight of their students over the last five years. After consulting with three companies that specialize in student physical health, they offer the companies an opportunity to prove their value.

So, the board randomly assigns each company to a group of schools. Starting in the next academic year, each company will implement their healthy habits program in 5 middle schools.

Preliminary data is collected at each school at the beginning of the school year. Each and every student is weighed, their resting heart rate, blood pressure and cholesterol are also measured.

After analyzing the data, it is found that the schools assigned to each of the three companies are relatively similar on all of these measures.

At the end of the year, data for students at each school will be collected again. A simple comparison of pre- and post-program measurements will be conducted. The company with the best outcomes will be selected to implement their program city-wide.

Action research is a great way to collect data on a specific issue, implement a change, and then evaluate the effects of that change. It is perhaps the most practical of all types of primary research .

Most likely, the results will be mixed. Some aspects of the change were effective, while other elements were not. That’s okay. This just means that additional modifications to the change plan need to be made, which is usually quite easy to do.

There are many methods that can be utilized, such as surveys, field observations , and program evaluations.

The beauty of action research is based in its utility and flexibility. Just about anyone in a school setting is capable of conducting action research and the information can be incredibly useful.

Aronson, E., & Patnoe, S. (1997). The jigsaw classroom: Building cooperation in the classroom (2nd ed.). New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

Gillis, A., & Jackson, W. (2002). Research Methods for Nurses: Methods and Interpretation . Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company.

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of SocialIssues, 2 (4), 34-46.

Macdonald, C. (2012). Understanding participatory action research: A qualitative research methodology option. Canadian Journal of Action Research, 13 , 34-50. https://doi.org/10.33524/cjar.v13i2.37 Mertler, C. A. (2008). Action Research: Teachers as Researchers in the Classroom . London: Sage.

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Positive Punishment Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Dissociation Examples (Psychology)

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Zone of Proximal Development Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ Perception Checking: 15 Examples and Definition

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Positive Punishment Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Dissociation Examples (Psychology)

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Zone of Proximal Development Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link Perception Checking: 15 Examples and Definition

2 thoughts on “21 Action Research Examples (In Education)”

Where can I capture this article in a better user-friendly format, since I would like to provide it to my students in a Qualitative Methods course at the University of Prince Edward Island? It is a good article, however, it is visually disjointed in its current format. Thanks, Dr. Frank T. Lavandier

Hi Dr. Lavandier,

I’ve emailed you a word doc copy that you can use and edit with your class.

Best, Chris.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Action research in the classroom: A teacher's guide

November 26, 2021

Discover best practices for action research in the classroom, guiding teachers on implementing and facilitating impactful studies in schools.

Main, P (2021, November 26). Action research in the classroom: A teacher's guide. Retrieved from https://www.structural-learning.com/post/action-research-in-the-classroom-a-teachers-guide

What is action research?

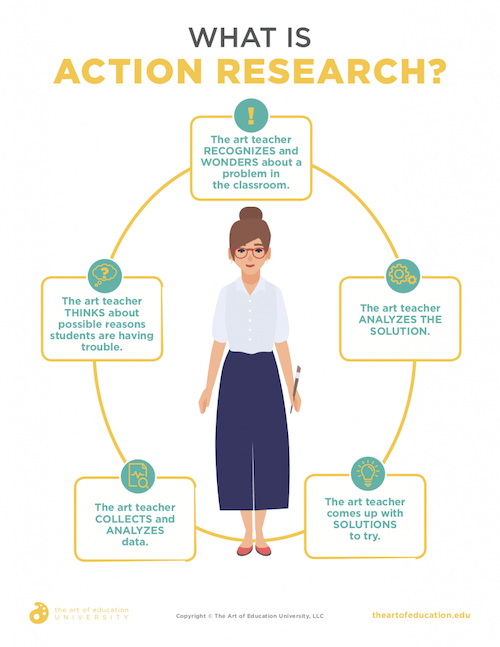

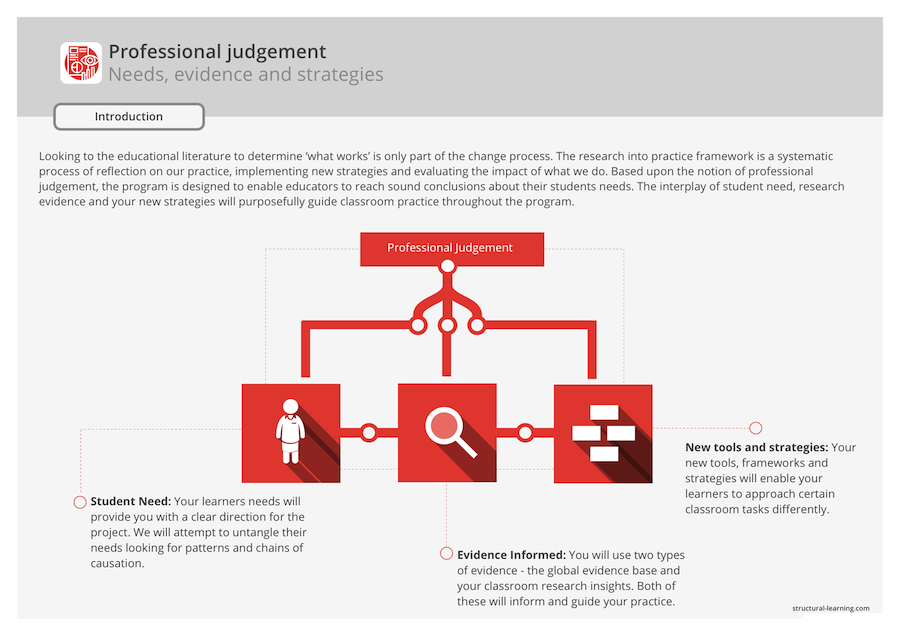

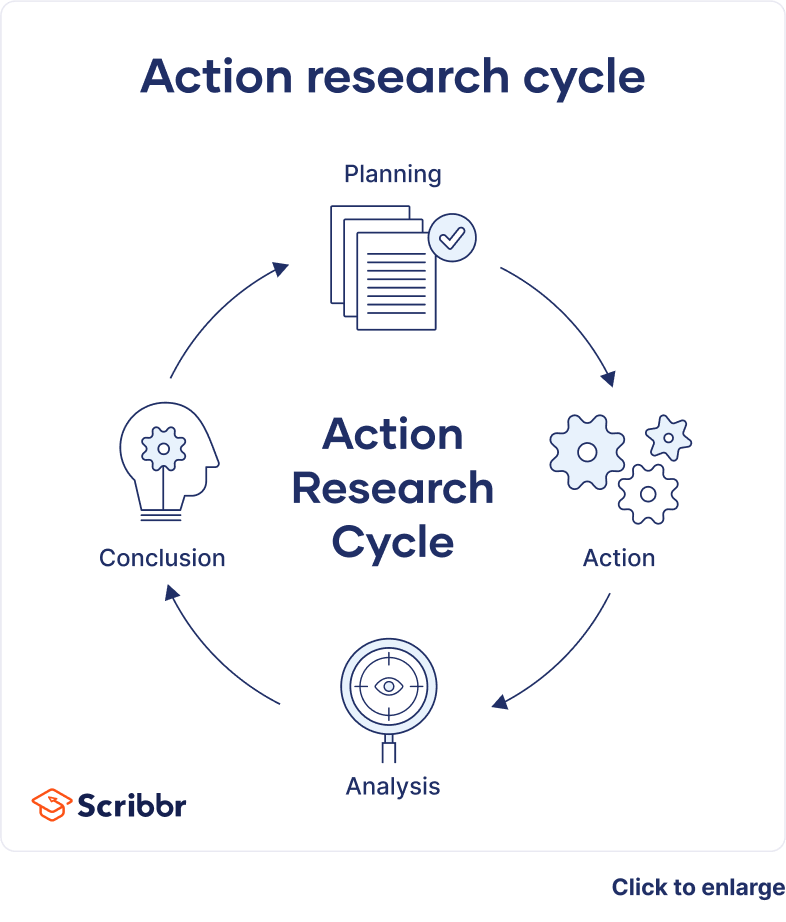

Action research is a participatory process designed to empower educators to examine and improve their own practice. It is characterized by a cycle of planning , action, observation, and reflection, with the goal of achieving a deeper understanding of practice within educational contexts. This process encourages a wide range of approaches and can be adapted to various social contexts.

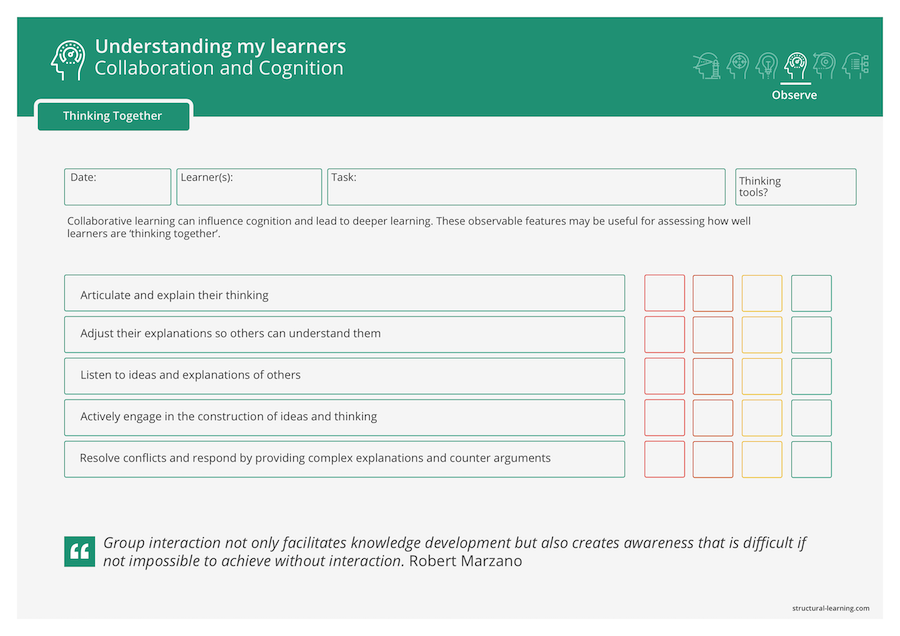

At its core, action research involves critical reflection on one's actions as a basis for improvement. Senior leaders and teachers are guided to reflect on their educational strategies , classroom management, and student engagement techniques. It's a collaborative effort that often involves not just the teachers but also the students and other stakeholders, fostering an inclusive process that values the input of all participants.

The action research process is iterative, with each cycle aiming to bring about a clearer understanding and improvement in practice. It typically begins with the identification of real-world problems within the school environment, followed by a circle of planning where strategies are developed to address these issues. The implementation of these strategies is then observed and documented, often through journals or participant observation, allowing for reflection and analysis.

The insights gained from action research contribute to Organization Development, enhancing the quality of teaching and learning. This approach is strongly aligned with the principles of Quality Assurance in Education, ensuring that the actions taken are effective and responsive to the needs of the school community.

Educators can share their findings in community forums or through publications in journals, contributing to the wider theory about practice . Tertiary education sector often draws on such studies to inform teacher training and curriculum development.

In summary, the significant parts of action research include:

- A continuous cycle of planning, action, observation, and reflection.

- A focus on reflective practice to achieve a deeper understanding of educational methodologies.

- A commitment to inclusive and participatory processes that engage the entire school community.

Creating an action research project

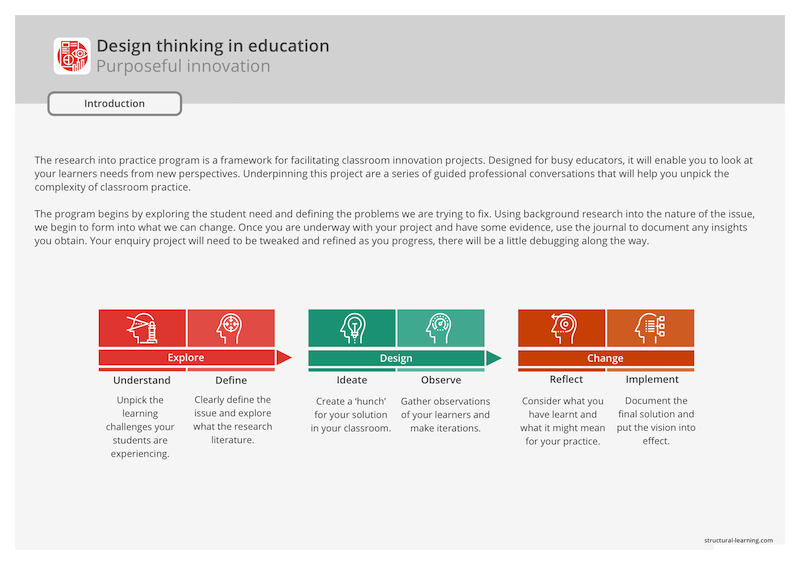

The action research process usually begins with a situation or issue that a teacher wants to change as part of school improvement initiatives .

Teachers get support in changing the ' interesting issue ' into a 'researchable question' and then taking to experiment. The teacher will draw on the outcomes of other researchers to help build actions and reveal the consequences .

Participatory action research is a strategy to the enquiry which has been utilised since the 1940s. Participatory action involves researchers and other participants taking informed action to gain knowledge of a problematic situation and change it to bring a positive effect. As an action researcher , a teacher carries out research . Enquiring into their practice would lead a teacher to question the norms and assumptions that are mostly overlooked in normal school life . Making a routine of inquiry can provide a commitment to learning and professional development . A teacher-researcher holds the responsibility for being the source and agent of change.

Examples of action research projects in education include a teacher working with students to improve their reading comprehension skills , a group of teachers collaborating to develop and implement a new curriculum, or a school administrator conducting a study on the effectiveness of a school-wide behavior management program.

In each of these cases, the research is aimed at improving the educational experience for students and addressing a specific issue or problem within the school community . Action research can be a powerful tool for educators to improve their practice and make a positive impact on their students' learning.

Potential research questions could include:

- How can dual-coding be used to improve my students memory ?

- Does mind-mapping lead to creativity?

- How does Oracy improve my classes writing?

- How can we advance critical thinking in year 10?

- How can graphic organisers be used for exam preparation?

Regardless of the types of action research your staff engage in, a solid cycle of inquiry is an essential aspect of the action research spiral. Building in the process of reflection will ensure that key points of learning can be extracted from the action research study.

What is an action research cycle?

Action research in education is a cycle of reflection and action inquiry , which follows these steps:

1. Identifying the problem

It is the first stage of action research that starts when a teacher identifies a problem or question that they want to address. To make an a ction research approach successful, the teacher needs to ensure that the questions are the ones 'they' wish to solve. Their questions might involve social sciences, instructional strategies, everyday life and social management issues, guide for students analytical research methods for improving specific student performance or curriculum implementation etc. Teachers may seek help from a wide variety of existing literature , to find strategies and solutions that others have executed to solve any particular problem. It is also suggested to build a visual map or a table of problems, target performances, potential solutions and supporting references in the middle.

2. Developing an Action Plan

After identifying the problem, after r eviewing the relevant literature and describing the vision of how to solve the problem; the next step would be action planning which means to develop a plan of action . Action planning involves studying the literature and brainstorming can be used by the action research planner to create new techniques and strategies that can generate better results of both action learning and action research. One may go back to the visual map or table of contents and reorder or colour-code the potential outcomes. The items in the list can be ranked in order of significance and the amount of time needed for these strategies.

An action plan has the details of how to implement each idea and the factors that may keep them from their vision of success . Identify those factors that cannot be changed –these are the constants in an equation. The focus of action research at the planning stage must remain focused on the variables –the factors that can be changed using actions. An action plan must be how to implement a solution and how one's instruction, management style, and behaviour will affect each of the variables.

3. Data Collection

Before starting to implement a plan of action , the researcher must have a complete understanding of action research and must have knowledge of the type of data that may help in the success of the plan and must assess how to collect that data. For instance, if the goal is to improve class attendance, attendance records must be collected as useful data for the participatory action. If the goal is to improve time management, the data may include students and classroom observations . There are many options to choose from to collect data from. Selecting the most suitable methodology for data collection will provide more meaningful , accurate and valid data. Some sources of data are interviews and observation. Also, one may administer surveys , distribute questionnaires and watch videotapes of the classroom to collect data.

4. Data Analysis and Conclusions

At this action stage, an action researcher analyses the collected data and concludes. It is suggested to assess the data during the predefined process of data collection as it will help refine the action research agenda. If the collected data seems insufficient , the data collection plan must be revised. Data analysis also helps to reflect on what exactly happened. Did the action researcher perform the actions as planned? Were the study outcomes as expected? Which assumptions of the action researcher proved to be incorrect?

Adding details such as tables, opinions, and recommendations can help in identifying trends (correlations and relationships). One must share the findings while analysing data and drawing conclusions . Engaging in conversations for teacher growth is essential; hence, the action researcher would share the findings with other teachers through discussion of action research, who can yield useful feedback. One may also share the findings with students, as they can also provide additional insight . For example, if teachers and students agree with the conclusions of action research for educational change, it adds to the credibility of the data collection plan and analysis. If they don't seem to agree with the data collection plan and analysis , the action researchers may take informed action and refine the data collection plan and reevaluate conclusions .

5. Modifying the Educational Theory and Repeat

After concluding, the process begins again. The teacher can adjust different aspects of the action research approach to theory or make it more specific according to the findings . Action research guides how to change the steps of action research development, how to modify the action plan , and provide better access to resources, start data collection once again, or prepare new questions to ask from the respondents.

6. Report the Findings

Since the main approach to action research involves the informed action to introduce useful change into the classroom or schools, one must not forget to share the outcomes with others. Sharing the outcomes would help to further reflect on the problem and process, and it would help other teachers to use these findings to enhance their professional practice as an educator. One may print book and share the experience with the school leaders, principal, teachers and students as they served as guide to action research. Or, a community action researcher may present community-based action research at a conference so people from other areas can take advantage of this collaborative action. Also, teachers may use a digital storytelling tool to outline their results.

There are plenty of creative tools we can use to bring the research projects to life. We have seen videos, podcasts and research posters all being used to communicate the results of these programs. Community action research is a unique way to present details of the community-related adventures in the teacher profession, cultivate expertise and show how teachers think about education , so it is better to find unique ways to report the findings of community-led action research.

Final thoughts on action-research for teachers

As we have seen, action research can be an effective form of professional development, illuminating the path for teachers and school leaders seeking to refine their craft. This cyclical process of inquiry and reflection is not merely a methodological pursuit but a profound professional journey. The definition of action research, as a systematic inquiry conducted by teachers, administrators, and other stakeholders in the teaching/learning environment, emphasizes the collaborative nature of improving educational strategies and outcomes.

Action research transcends traditional disciplinary practices by immersing educators in the social contexts of their work, prompting them to question and adapt their methods to meet the evolving needs of their students . It is a form of reflective practice that demands critical thinking and flexibility, as one navigates through the iterative stages of planning, acting, observing, and reflecting.

The process of action research is inherently participatory, encouraging educators to engage with their learning communities to address key issues and social issues that impact educational settings. This method empowers professionals within universities and schools alike to take ownership of their learning and development, fostering a culture of continuous improvement and participatory approaches.

In summary, action research encapsulates the essence of what it means to be a learning professional in a dynamic educational landscape. It is the embodiment of a commitment to lifelong learning and a testament to the capacity of educators to enact change . The value of action research lies in its ability to transform practitioners into researchers, where the quest for knowledge becomes a powerful conduit for change and innovation. Thus, for educators at every level, embracing the rigorous yet rewarding path of action research can unveil potent insights and propel educational practice to new heights.

Key Papers on Action Research

- Utilizing Action Research During Student Teaching by James O. Barbre and Brenda J. Buckner (2013): This study explores how action research can be effectively utilized during student teaching to enhance professional pedagogical disposition through active reflection. It emphasizes developing a reflective habit of mind crucial for teachers to be effective in their classrooms and adaptive to the changing needs of their students.

- Repositioning T eacher Action Research in Science Teacher Education by B. Capobianco and A. Feldman (2010): This paper discusses the promotion of action research as a way for teachers to improve their practice and students' learning for over 50 years, focusing on science education. It highlights the importance of action research in advancing knowledge about teaching and learning in science.

- Action research and teacher leadership by K. Smeets and P. Ponte (2009): This article reports on a case study into the influence and impact of action research carried out by teachers in a special school. It found that action research not only helps teachers to get to grips with their work in the classroom but also has an impact on the work of others in the school.

- Teaching about the Nature of Science through History: Action Research in the Classroom by J. Solomon, Jon Duveen, Linda Scot, S. McCarthy (1992): This article reports on 18 months of action research monitoring British pupils' learning about the nature of science using historical aspects. It indicates areas of substantial progress in pupils' understanding of the nature of science.

- Action Research in the Classroom by V. Baumfield, E. Hall, K. Wall (2008): This comprehensive guide to conducting action research in the classroom covers various aspects, including deciding on a research question, choosing complementary research tools, collecting and interpreting data, and sharing findings. It aims to move classroom inquiry forward and contribute to professional development.

These studies highlight the significant role of action research in enhancing teacher effectiveness, student learning outcomes, and contributing to the broader educational community's knowledge and practices.

Enhance Learner Outcomes Across Your School

Download an Overview of our Support and Resources

We'll send it over now.

Please fill in the details so we can send over the resources.

What type of school are you?

We'll get you the right resource

Is your school involved in any staff development projects?

Are your colleagues running any research projects or courses?

Do you have any immediate school priorities?

Please check the ones that apply.

Download your resource

Thanks for taking the time to complete this form, submit the form to get the tool.

Classroom Practice

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

Published on January 27, 2023 by Tegan George . Revised on January 12, 2024.

Table of contents

Types of action research, action research models, examples of action research, action research vs. traditional research, advantages and disadvantages of action research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about action research.

There are 2 common types of action research: participatory action research and practical action research.

- Participatory action research emphasizes that participants should be members of the community being studied, empowering those directly affected by outcomes of said research. In this method, participants are effectively co-researchers, with their lived experiences considered formative to the research process.

- Practical action research focuses more on how research is conducted and is designed to address and solve specific issues.

Both types of action research are more focused on increasing the capacity and ability of future practitioners than contributing to a theoretical body of knowledge.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Action research is often reflected in 3 action research models: operational (sometimes called technical), collaboration, and critical reflection.

- Operational (or technical) action research is usually visualized like a spiral following a series of steps, such as “planning → acting → observing → reflecting.”

- Collaboration action research is more community-based, focused on building a network of similar individuals (e.g., college professors in a given geographic area) and compiling learnings from iterated feedback cycles.

- Critical reflection action research serves to contextualize systemic processes that are already ongoing (e.g., working retroactively to analyze existing school systems by questioning why certain practices were put into place and developed the way they did).

Action research is often used in fields like education because of its iterative and flexible style.

After the information was collected, the students were asked where they thought ramps or other accessibility measures would be best utilized, and the suggestions were sent to school administrators. Example: Practical action research Science teachers at your city’s high school have been witnessing a year-over-year decline in standardized test scores in chemistry. In seeking the source of this issue, they studied how concepts are taught in depth, focusing on the methods, tools, and approaches used by each teacher.

Action research differs sharply from other types of research in that it seeks to produce actionable processes over the course of the research rather than contributing to existing knowledge or drawing conclusions from datasets. In this way, action research is formative , not summative , and is conducted in an ongoing, iterative way.

As such, action research is different in purpose, context, and significance and is a good fit for those seeking to implement systemic change.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Action research comes with advantages and disadvantages.

- Action research is highly adaptable , allowing researchers to mold their analysis to their individual needs and implement practical individual-level changes.

- Action research provides an immediate and actionable path forward for solving entrenched issues, rather than suggesting complicated, longer-term solutions rooted in complex data.

- Done correctly, action research can be very empowering , informing social change and allowing participants to effect that change in ways meaningful to their communities.

Disadvantages

- Due to their flexibility, action research studies are plagued by very limited generalizability and are very difficult to replicate . They are often not considered theoretically rigorous due to the power the researcher holds in drawing conclusions.

- Action research can be complicated to structure in an ethical manner . Participants may feel pressured to participate or to participate in a certain way.

- Action research is at high risk for research biases such as selection bias , social desirability bias , or other types of cognitive biases .

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Action research is conducted in order to solve a particular issue immediately, while case studies are often conducted over a longer period of time and focus more on observing and analyzing a particular ongoing phenomenon.

Action research is focused on solving a problem or informing individual and community-based knowledge in a way that impacts teaching, learning, and other related processes. It is less focused on contributing theoretical input, instead producing actionable input.

Action research is particularly popular with educators as a form of systematic inquiry because it prioritizes reflection and bridges the gap between theory and practice. Educators are able to simultaneously investigate an issue as they solve it, and the method is very iterative and flexible.

A cycle of inquiry is another name for action research . It is usually visualized in a spiral shape following a series of steps, such as “planning → acting → observing → reflecting.”

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

George, T. (2024, January 12). What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/action-research/

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education (8th edition). Routledge.

Naughton, G. M. (2001). Action research (1st edition). Routledge.

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is an observational study | guide & examples, primary research | definition, types, & examples, guide to experimental design | overview, steps, & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Our Mission

How Teachers Can Learn Through Action Research

A look at one school’s action research project provides a blueprint for using this model of collaborative teacher learning.

When teachers redesign learning experiences to make school more relevant to students’ lives, they can’t ignore assessment. For many teachers, the most vexing question about real-world learning experiences such as project-based learning is: How will we know what students know and can do by the end of this project?

Teachers at the Siena School in Silver Spring, Maryland, decided to figure out the assessment question by investigating their classroom practices. As a result of their action research, they now have a much deeper understanding of authentic assessment and a renewed appreciation for the power of learning together.

Their research process offers a replicable model for other schools interested in designing their own immersive professional learning. The process began with a real-world challenge and an open-ended question, involved a deep dive into research, and ended with a public showcase of findings.

Start With an Authentic Need to Know

Siena School serves about 130 students in grades 4–12 who have mild to moderate language-based learning differences, including dyslexia. Most students are one to three grade levels behind in reading.

Teachers have introduced a variety of instructional strategies, including project-based learning, to better meet students’ learning needs and also help them develop skills like collaboration and creativity. Instead of taking tests and quizzes, students demonstrate what they know in a PBL unit by making products or generating solutions.

“We were already teaching this way,” explained Simon Kanter, Siena’s director of technology. “We needed a way to measure, was authentic assessment actually effective? Does it provide meaningful feedback? Can teachers grade it fairly?”

Focus the Research Question

Across grade levels and departments, teachers considered what they wanted to learn about authentic assessment, which the late Grant Wiggins described as engaging, multisensory, feedback-oriented, and grounded in real-world tasks. That’s a contrast to traditional tests and quizzes, which tend to focus on recall rather than application and have little in common with how experts go about their work in disciplines like math or history.

The teachers generated a big research question: Is using authentic assessment an effective and engaging way to provide meaningful feedback for teachers and students about growth and proficiency in a variety of learning objectives, including 21st-century skills?

Take Time to Plan

Next, teachers planned authentic assessments that would generate data for their study. For example, middle school science students created prototypes of genetically modified seeds and pitched their designs to a panel of potential investors. They had to not only understand the science of germination but also apply their knowledge and defend their thinking.

In other classes, teachers planned everything from mock trials to environmental stewardship projects to assess student learning and skill development. A shared rubric helped the teachers plan high-quality assessments.

Make Sense of Data

During the data-gathering phase, students were surveyed after each project about the value of authentic assessments versus more traditional tools like tests and quizzes. Teachers also reflected after each assessment.

“We collated the data, looked for trends, and presented them back to the faculty,” Kanter said.

Among the takeaways:

- Authentic assessment generates more meaningful feedback and more opportunities for students to apply it.

- Students consider authentic assessment more engaging, with increased opportunities to be creative, make choices, and collaborate.

- Teachers are thinking more critically about creating assessments that allow for differentiation and that are applicable to students’ everyday lives.

To make their learning public, Siena hosted a colloquium on authentic assessment for other schools in the region. The school also submitted its research as part of an accreditation process with the Middle States Association.

Strategies to Share

For other schools interested in conducting action research, Kanter highlighted three key strategies.

- Focus on areas of growth, not deficiency: “This would have been less successful if we had said, ‘Our math scores are down. We need a new program to get scores up,’ Kanter said. “That puts the onus on teachers. Data collection could seem punitive. Instead, we focused on the way we already teach and thought about, how can we get more accurate feedback about how students are doing?”

- Foster a culture of inquiry: Encourage teachers to ask questions, conduct individual research, and share what they learn with colleagues. “Sometimes, one person attends a summer workshop and then shares the highlights in a short presentation. That might just be a conversation, or it might be the start of a school-wide initiative,” Kanter explained. In fact, that’s exactly how the focus on authentic assessment began.

- Build structures for teacher collaboration: Using staff meetings for shared planning and problem-solving fosters a collaborative culture. That was already in place when Siena embarked on its action research, along with informal brainstorming to support students.

For both students and staff, the deep dive into authentic assessment yielded “dramatic impact on the classroom,” Kanter added. “That’s the great part of this.”

In the past, he said, most teachers gave traditional final exams. To alleviate students’ test anxiety, teachers would support them with time for content review and strategies for study skills and test-taking.

“This year looks and feels different,” Kanter said. A week before the end of fall term, students were working hard on final products, but they weren’t cramming for exams. Teachers had time to give individual feedback to help students improve their work. “The whole climate feels way better.”

Guiding School Improvement with Action Research

$15.76 member price join now.

Action research, explored in this book, is a seven-step process for improving teaching and learning in classrooms at all levels. Through practical examples, research tools, and easy-to-follow “implementation strategies,” Richard Sagor guides readers through the process from start to finish. Learn how to uncover and use the data that already exist in your classrooms and schools to answer significant questions about your individual or collective concerns and interests. Sagor covers each step in the action research process in detail: selecting a focus, clarifying theories, identifying research questions, collecting data, analyzing data, reporting results, and taking informed action.

Table of contents

How Is Action Research Accomplished?

Professionalism, Teacher Efficacy, and Standards-Based Education

Teaching: A Complex Process

About the authors

Richard Sagor took a leave from his position as an Associate Professor of Education at Washington State University in August of 1997 to found the Institute for the Study of Inquiry in Education, an organization committed to assisting schools and educators with their local school improvement initiatives. During the past decade Dick has facilitated workshops on the conduct of collaborative action research throughout the United States and internationally.

Book details

Product no., 978-0-87120-375-5, release date, member book, topics in this book, related books, to process a transaction with a purchase order please send to [email protected].

Created by the Great Schools Partnership , the GLOSSARY OF EDUCATION REFORM is a comprehensive online resource that describes widely used school-improvement terms, concepts, and strategies for journalists, parents, and community members. | Learn more »

Action Research

In schools, action research refers to a wide variety of evaluative, investigative, and analytical research methods designed to diagnose problems or weaknesses—whether organizational, academic, or instructional—and help educators develop practical solutions to address them quickly and efficiently. Action research may also be applied to programs or educational techniques that are not necessarily experiencing any problems, but that educators simply want to learn more about and improve. The general goal is to create a simple, practical, repeatable process of iterative learning, evaluation, and improvement that leads to increasingly better results for schools, teachers, or programs.

Action research may also be called a cycle of action or cycle of inquiry , since it typically follows a predefined process that is repeated over time. A simple illustrative example:

- Identify a problem to be studied

- Collect data on the problem

- Organize, analyze, and interpret the data

- Develop a plan to address the problem

- Implement the plan

- Evaluate the results of the actions taken

- Identify a new problem

- Repeat the process

Unlike more formal research studies, such as those conducted by universities and published in peer-reviewed scholarly journals, action research is typically conducted by the educators working in the district or school being studied—the participants—rather than by independent, impartial observers from outside organizations. Less formal, prescriptive, or theory-driven research methods are typically used when conducting action research, since the goal is to address practical problems in a specific school or classroom, rather than produce independently validated and reproducible findings that others, outside of the context being studied, can use to guide their future actions or inform the design of their academic programs. That said, while action research is typically focused on solving a specific problem (high rates of student absenteeism, for example) or answer a specific question (Why are so many of our ninth graders failing math?), action research can also make meaningful contributions to the larger body of knowledge and understanding in the field of education, particularly within a relatively closed system such as school, district, or network of connected organizations.

The term “action research” was coined in the 1940s by Kurt Lewin, a German-American social psychologist who is widely considered to be the founder of his field. The basic principles of action research that were described by Lewin are still in use to this day.

Educators typically conduct action research as an extension of a particular school-improvement plan, project, or goal—i.e., action research is nearly always a school-reform strategy. The object of action research could be almost anything related to educational performance or improvement, from the effectiveness of certain teaching strategies and lesson designs to the influence that family background has on student performance to the results achieved by a particular academic support strategy or learning program—to list just a small sampling.

For related discussions, see action plan , capacity , continuous improvement , evidence-based , and professional development .

Alphabetical Search

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Neag School of Education

Educational Research Basics by Del Siegle

Action research.

An Introduction to Action Research Jeanne H. Purcell, Ph.D.

Your Options

- Review Related Literature

- Examine the Impact of an Experimental Treatment

- Monitor Change

- Identify Present Practices

- Describe Beliefs and Attitudes

Action Research Is…

- Action research is a three-step spiral process of (1) planning which involves fact-finding, (2) taking action, and (3) fact-finding about the results of the action. (Lewin, 1947)

- Action research is a process by which practitioners attempt to study their problems scientifically in order to guide, correct, and evaluate their decisions and action. (Corey, 1953).

- Action research in education is study conducted by colleagues in a school setting of the results of their activities to improve instruction. (Glickman, 1990)

- Action research is a fancy way of saying Let’s study what s happening at our school and decide how to make it a better place. (Calhoun,1994)

Conditions That Support Action Research

- A faculty where a majority of teachers wish to improve some aspect (s) of education in their school.

- Common agreement about how collective decisions will be made and implemented.

- A team that is willing to lead the initiative.

- Study groups that meet regularly.

- A basic knowledge of the action research cycle and the rationale for its use.

- Someone to provide technical assistance and/or support.

The Action Research Cycle

- Identify an area of interest/problem.

- Identify data to be collected, the format for the results, and a timeline.

- Collect and organize the data.

- Analyze and interpret the data.

- Decide upon the action to be taken.

- Evaluate the success of the action.

Collecting Data: Sources

Existing Sources

- Attendance at PTO meetings

- + and – parent communications

- Office referrals

- Special program enrollment

- Standardized scores

Inventive Sources

- Interviews with parents

- Library use, by grade, class

- Minutes of meetings

- Nature and amount of in-school assistance related to the innovation

- Number of books read

- Observation journals

- Record of peer observations

- Student journals

- Teacher journals

- Videotapes of students: whole class instruction

- Videotapes of students: Differentiated instruction

- Writing samples

Collecting Data: From Whom?

- From everyone when we are concerned about each student’s performance.

- From a sample when we need to increase our understanding while limiting our expenditure of time and energy; more in-depth interviews or observations may follow.

Collecting Data: How Often?

- At regular intervals

- At critical points

Collecting Data: Guidelines

- Use both existing and inventive data sources.

- Use multiple data sources.

- Collect data regularly.

- Seek help, if necessary.

Organizing Data

- Keep it simple.

- Disaggregate numbers from interviews and other qualitative types of data.

- Plan plenty of time to look over and organize the data.

- Seek technical assistance if needed.

Analyzing Data

- What important points do they data reveal?

- What patterns/trends do you note? What might be some possible explanations?

- Do the data vary by sources? Why might the variations exist?

- Are there any results that are different from what you expected? What might be some hypotheses to explain the difference (s)?

- What actions appear to be indicated?

Taking Action

- Do the data warrant action?

- What might se some short-term actions?

- What might be some long-term actions?

- How will we know if our actions have been effective?

- What benchmarks might we expect to see along the way to effectiveness ?

Action Plans

- Target date

- Responsibility

- Evidence of Effectiveness

Action Research Handout

Bibliography

Brubacher, J. W., Case, C. W., & Reagan, T. G. (1994). Becoming a reflective educator . Thousand Oaks: CA: Corwin Press.

Burnaford, G., Fischer, J., & Hobson, D. (1996). Teachers doing research . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Calhoun, Emily (1994). How to use action research in the self-renewing school . Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Corey, S. M. (1953). Action research to improve school practices . New York: Teachers College Press.

Glickman, C. D. (1990). Supervision of instruction: A developmental approach . Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Hubbard, R. S. & Power, B. M. (1993). The art of classroom inquiry . Portsmouth, NH: Heineman.

Lewin, K. (1947). Group decisions and social change. In Readings in social psychology . (Eds. T M. Newcomb and E. L. Hartley). New York: Henry Holt.

- Tes Explains

What is action research?

Action research is a practice-based research method, designed to bring about change in a context. In the context of schools, it might be a teacher-led investigation, usually conducted within the teacher’s own school or classroom.

When a problem or question is identified, an initiative is devised to address it. Following implementation, the impact is then assessed and reflected upon. This reflection may lead to amendments to the initiative, before repeating the process again.

Where can I see this in action?

In 2021, teacher and apprenticeship manager Dave Shurmer conducted research that looked at the impact that increased physical activity has on pupils’ academic attainment in literacy and numeracy.

He asked pupils to skip for two minutes before English or maths lessons. At the end of the term, pupils sat a Sats practice paper. Shurmer compared the data from before and after the term for a conditioned and unconditioned group, and found that when the pupils skipped before lessons once a week, they went on to gain an extra mark on their test papers. When they skipped twice a week, they gained an extra two marks.

In 2022, English teacher Katie Packman wrote about her action research project for Tes : after struggling to enthuse key stage 3 students in creative writing, she decided to introduce a workshopping approach. For one hour a week, students were given free rein to choose a creative writing project to develop. She held one-on-one tutorials to give feedback, and students had to plan and then draft their piece, and continue to work on it or start planning their next piece, until their next tutorial. In the end-of-year assessment results, 27 out of 28 students had made expected progress, and 65 per cent of those had made higher-than-expected progress.

Further reading:

- How to lead whole-class guided reading in schools

- Action research in the classroom: a quick guide

- Active learning: make a drama out of teaching punctuation

- “Front loading” and how it can support learning

- Why we use action research as CPD

The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) is an independent charity dedicated to breaking the link between family income and educational achievement.

To achieve this, it summarises the best available evidence for teachers; its Teaching and Learning Toolkit, for example, is used by 70 per cent of secondary schools.

The charity also generates new evidence of “what works” to improve teaching and learning, by funding independent evaluations of high-potential projects, and supports teachers and senior leaders to use the evidence to achieve the maximum possible benefit for young people.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

5 Collecting Data in Your Classroom

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- What sort of methodological considerations are necessary to collect data in your educational context?

- What methods of data collection will be most effective for your study?

- What are the affordances and limitations associated with your data collection methods?

- What does it mean to triangulate data, and why is it necessary?

As you develop an action plan for your action research project, you will be thinking about the primary task of conducting research, and probably contemplating the data you will collect. It is likely you have asked yourself questions related to the methods you will be using, how you will organize the data collection, and how each piece of data is related within the larger project. This chapter will help you think through these questions.

Data Collection

The data collection methods used in educational research have originated from a variety of disciplines (anthropology, history, psychology, sociology), which has resulted in a variety of research frameworks to draw upon. As discussed in the previous chapter, the challenge for educator-researchers is to develop a research plan and related activities that are focused and manageable to study. While human beings like structure and definitions, especially when we encounter new experiences, educators-as-researchers frequently disregard the accepted frameworks related to research and rely on their own subjective knowledge from their own pedagogical experiences when taking on the role of educator-researcher in educational settings. Relying on subjective knowledge enables teachers to engage more effectively as researchers in their educational context. Educator-researchers especially rely on this subjective knowledge in educational contexts to modify their data collection methodologies. Subjective knowledge negotiates the traditional research frameworks with the data collection possibilities of their practice, while also considering their unique educational context. This empowers educators as researchers, utilizing action research, to be powerful agents for change in educational contexts.

Thinking about Types of Data

Whether the research design is qualitative, quantitative or mixed-methods, it will determine the methods or ways you use to collect data. Qualitative research designs focus on collecting data that is relational, interpretive, subjective, and inductive; whereas a typical quantitative study, collects data that are deductive, statistical, and objective.

In contrast, qualitative data is often in the form of language, while quantitative data typically involves numbers. Quantitative researchers require large numbers of participants for validity, while qualitative researchers use a smaller number of participants, and can even use one (Hatch, 2002). In the past, quantitative and qualitative educational researchers rarely interacted, sometimes holding contempt for each other’s work; and even published articles in separate journals based on having distinct theoretical orientations in terms of data collection. Overall, there is a greater appreciation for both quantitative and qualitative approaches, with scholars finding distinct value in each approach, yet in many circles the debate continues over which approach is more beneficial for educational research and in educational contexts.

The goal of qualitative data collection is to build a complex and nuanced description of social or human problems from multiple perspectives. The flexibility and ability to use a variety of data collection techniques encompasses a distinct stance on research. Qualitative researchers are able to capture conversations and everyday language, as well as situational attitudes and beliefs. Qualitative data collection is able to be fitted to the study, with the goal of collecting the most authentic data, not necessarily the most objective. To researchers who strictly use quantitative methods, qualitative methods may seem wholly unstructured, eclectic, and idiosyncratic; however, for qualitative researchers these characteristics are advantageous to their purpose. Quantitative research depends upon structure and is bounded to find relationship among variables and units of measurement. Quantitative research helps make sense of large amounts of data. Both quantitative and qualitative research help us address education challenges by better identifying what is happening, with the goal of identifying why it is happening, and how we can address it.

Most educator-researchers who engage in research projects in schools and classrooms utilize qualitative methodologies for their data collection. Educator-researchers also use mixed methods that focus on qualitative methods, but also use quantitative methods, such as surveys, to provide a multidimensional approach to inquiring about their topic. While qualitative methods may feel more comfortable, there is a methodological rationale for using quantitative research.

Research methodologists use two distinct forms of logic to describe research: induction and deduction. Inductive approaches are focused on developing new or emerging theories, by explaining the accumulation of evidence that provides meaning to similar circumstances. Deductive approaches move in the opposite direction, and create meaning about a particular situation by reasoning from a general idea or theory about the particular circumstances. While qualitative approaches are inductive – observe and then generate theories, for example – qualitative researchers will typically initiate studies with some preconceived notions of potential theories to support their work.

Flexible Research Design

A researcher’s decisions about data collection and activities involve a personal choice, yet the choice of data sources must be responsive to the proposed project and topic. Logically, researchers will use whatever validated methods help them to address the issue they are researching and will develop a research plan around activities to implement those methods. While a research plan is important to conducting valid research in schools and classrooms, a research plan should also be flexible in design to allow data to emerge and find the best data to address research questions. In this way, a research plan is recommended, but data collection methods are not always known in advance. As you, the educator-researcher, interacts with participants, you may find it necessary to continue the research with additional data sources to better address the question at the center of your research. When educators are researchers and a participant in their study, it is especially important to keep an open mind to the wide range of research methodologies. All-in-all educator-researchers should understand that there are varied and multiple paths to move from research questions to addressing those questions.

Mixed Methods

As mentioned above, mixed methods is the use of both qualitative and quantitative methods. Researchers generally use mixed methods to clarify findings from the initial method of data collection. In mixed-methods research, the educator-researcher has increased flexibility in data collection. Mixed methods studies often result in a combination of precise measurements (e.g., grades, test scores, survey, etc.) along with in-depth qualitative data that provide meaningful detail to those measurements. The key advantage of using mixed methods is that quantitative details enhance qualitative data sources that involve conclusions and use terms such as usually, some, or most which can be substituted with a number or quantity, such as percentages or averages, or the mean, the median, and/or the mode. One challenge to educator-researchers is that mixed methods require more time and resources to complete the study, and more familiarity about both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods.

Mixed methods in educator research, even if quantitative methods are only used minimally, provide an opportunity to clarify findings, fill gaps in understanding, and cross-check data. For example, if you are looking at the use of math journals to better engage students and improve their math scores, it would be helpful to understand their abilities in math and reading before analyzing the math journals. Therefore, looking at their test scores might give you some nuanced understanding of why some students improved more than others after using the math journals. Pre- and post-surveys would also provide valuable information in terms of students’ attitudes and beliefs about math and writing. In line with thinking about pre- and post-surveys, some researchers suggest using either qualitative or quantitative approaches in different phases of the research process. In the previous example, pre- and post test scores may quantitatively demonstrate growth or improvement after implementing the math journal; however, the qualitative data would provide detailed evidence as to why the math journals contributed to growth or improvement in math. Quantitative methods can establish relationships among variables, while qualitative methods can explain factors underlying those same relationships.

I caution the reader at this point to not simply think of qualitative methodologies as anecdotal details to quantitative reports. I only highlight mixed methods to introduce the strength of such studies, and to aid in moving educational research methodology away from the binary thinking of quantitative vs. qualitative. In thinking about data collection, possible data sources include questionnaires or surveys, observations (video or written notes), collaboration (meetings, peer coaching), interviews, tests and records, pictures, diaries, transcripts of video and audio recordings, personal journals, student work samples, e-mail and online communication, and any other pertinent documents and reports. As you begin to think about data collection you will consider the available materials and think about aspects discussed in the previous chapter: who, what, where, when, and how. Specifically:

- Who are the subjects or participants for the study?

- What data is vital evidence for this study?

- Where will the data be collected?

- When will the data be collected?

- How will the data be collected?

If you find you are having trouble identifying data sources that support your initial question, you may need to revise your research question – and make sure what you are asking is researchable or measurable. The research question can always change throughout the study, but it should only be in relation the data being collected.

Participant Data

As an educator, your possible participants selection pool is narrower than most researchers encounter – however, it is important to be clear about their role in the data design and collection. A study can involve one participant or multiple participants, and participants often serve as the primary source of data in the research process. Most studies by educator-researchers utilize purposeful sampling, or in other words, they select participants who will be able to provide the most relevant information to the study. Therefore, the study design relies upon the participants and the information they can provide. The following is a description of some data collection methods, which include: surveys or questionnaires, individual or group interviews, observations, field notes or diaries, narratives, documents, and elicitation.

Surveys, or questionnaires, are a research instrument frequently used to receive data about participants’ feelings, beliefs, and attitudes in regard to the research topic or activities. Surveys are often used for large sample sizes with the intent of generalizing from a sample population to a larger population. Surveys are used with any number of participants and can be administered at different times during the study, such as pre-activity and post-activity, with the same participants to determine if changes have occurred over the course of the activity time, or simply change over time. Researchers like surveys and questionnaires as an instrument because they can be distributed and collected easily – especially with all of the recent online application possibilities (e.g., Google, Facebook, etc.). Surveys come in several forms, closed-ended, open-ended, or a mix of the two. Closed-ended surveys are typically multiple-choice questions or scales (e.g. 1-5, most likely–least likely) that allow participants to rate or select a response for each question. These responses can easily be tabulated into meaningful number representations, like percentages. For example, Likert scales are often used with a five-point range, with options such as strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree. Open-ended surveys consist of prompts for participants to add their own perspectives in short answer or limited word responses. Open-ended surveys are not always as easy to tabulate, but can provide more detail and description.

Interviews and Focus Groups

Interviews are frequently used by researchers because they often produce some of the most worthwhile data. Interviews allow researchers to obtain candid verbal perspectives through structured or semi-structured questioning. Interview questions, either structured or semi-structured, are related to the research question or research activities to gauge the participants’ thoughts, feelings, motivations, and reflections. Some research relies on interviewing as the primary data source, but most often interviews are used to strengthen and support other data sources. Interviews can be time consuming, but interviews are worthwhile in that you can gather richer and more revealing information than other methods that could be utilized (Koshy, 2010). Lincoln and Guba (1985) identified five outcomes of interviewing:

Outcomes of Interviewing

- Here and now explanations;

- Reconstructions of past events and experiences;

- Projections of anticipated experiences;

- Verification of information from other sources;

- Verification of information (p. 268).

As mentioned above, interviews typically take two forms: structured and semi-structured. In terms of interviews, structured means that the researcher identifies a certain number of questions, in a prescribed sequence, and the researcher asks each participant these questions in the same order. Structured interviews qualitatively resemble surveys and questionnaires because they are consistent, easy to administer, provide direct responses, and make tabulation and analysis more consistent. Structured interviews use an interview protocol to organize questions, and maintain consistency.

Semi-structured interviews have a prescribed set of questions and protocol, just like structured interviews, but the researcher does not have to follow those questions or order explicitly. The researcher should ask the same questions to each participant for comparison reasons, but semi-structured interviews allow the researcher to ask follow-up questions that stray from the protocol. The semi-structured interview is intended to allow for new, emerging topics to be obtained from participants. Semi-structured questions can be included in more structured protocols, which allows for the participant to add additional information beyond the formal questions and for the researcher to return to preplanned formal questions after the participant responds. Participants can be interviewed individually or collectively, and while individual interviews are time-consuming, they can provide more in-depth information.

When considering more than two participants for an interview, researchers will often use a focus group interview format. Focus group interviews typically involve three to ten participants and seek to gain socially dependent perspectives or organizational viewpoints. When using focus group interviews with students, researchers often find them beneficial because they allow student reflection and ideas to build off of each other. This is important because often times students feel shy or hesitant to share their ideas with adults, but once another student sparks or confirms their idea, belief, or opinion they are more willing to share. Focus group interviews are very effective as pre- and post-activity data sources. Researchers can use either a structured or semi-structured interview protocol for focus group interviews; however, with multiple participants it may be difficult to maintain the integrity of a structured protocol.

Observations

One of the simplest, and most natural, forms of data collection is to engage in formal observation. Observing humans in a setting provides us contextual understanding of the complexity of human behavior and interrelationships among groups in that setting. If a researcher wants to examine the ways teachers approach a particular area of pedagogical practice, then observation would be a viable data collection tool. Formal observations are truly unique and allow the researcher to collect data that cannot be obtained through other data sources. Ethnography is a qualitative research design that provides a descriptive account based on researchers’ observations and explorations to examine the social dynamics present in cultures and social systems – which includes classrooms and schools. Taken from anthropology, the ethnographer uses observations and detailed note taking, along with other forms of mapping or making sense of the context and relationships within. For Creswell (2007), several guidelines provide structure to an observation:

Structuring Observations

- Identify what to observe

- Determine the role you will assume — observer or participant

- Design observational protocol for recording notes

- Record information such as physical situation, particular events and activities

- Thank participants and inform them of the use of and their accessibility to the data (pp. 132– 134)

As an educator-researcher, you may take on a role that exceeds that of an observer and participate as a member of the research setting. In this case, the data sources would be called participant observation to clearly identify the degree of involvement you have in the study. In participant observation, the researcher embeds themselves in the actions of the participants. It is important to understand that participant observation will provide completely different data, in comparison to simply observing someone else. Ethnographies, or studies focused completely on observation as a data source, often extend longer than other data sources, ranging from several months to even years. Extended time provides the researcher the ability to obtain more detailed and accurate information, because it takes time to observe patterns and other details that are significant to the study. Self-study is another consideration for educators, if they want to use observation and be a participant observer. They can use video and audio recordings of their activities to use as data sources and use those as the source of observation.

Field Diaries and Notes

Utilizing a field dairy, or keeping field notes, can be a very effective and practical data collection method. In purpose, a field diary or notes keep a record of what happens during the research activities. It can be useful in tracking how and why your ideas and the research process evolved. Many educators keep daily notes about their classes, and in many ways, this is a more focused and narrower version of documenting the daily happenings of a class. A field diary or notes can also serve as an account of your reflections and commentary on your study, and can be a starting place for your data analysis and interpretations. A field diary or notes are typically valuable when researchers begin to write about their project because it allows them to draw upon their authentic voice. The reflective process that represents a diary can also serve as an additional layer of professional learning for researchers. The format and length of a field diary or notes will vary depending on the researching and the topic; however, the ultimate goal should be to facilitate data collection and analysis.