Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

The objective of a literature review

Questions to Consider

B. In some fields or contexts, a literature review is referred to as the introduction or the background; why is this true, and does it matter?

The elements of a literature review • The first step in scholarly research is determining the “state of the art” on a topic. This is accomplished by gathering academic research and making sense of it. • The academic literature can be found in scholarly books and journals; the goal is to discover recurring themes, find the latest data, and identify any missing pieces. • The resulting literature review organizes the research in such a way that tells a story about the topic or issue.

The literature review tells a story in which one well-paraphrased summary from a relevant source contributes to and connects with the next in a logical manner, developing and fulfilling the message of the author. It includes analysis of the arguments from the literature, as well as revealing consistent and inconsistent findings. How do varying author insights differ from or conform to previous arguments?

Language in Action

A. How are the terms “critique” and “review” used in everyday life? How are they used in an academic context?

In terms of content, a literature review is intended to:

• Set up a theoretical framework for further research • Show a clear understanding of the key concepts/studies/models related to the topic • Demonstrate knowledge about the history of the research area and any related controversies • Clarify significant definitions and terminology • Develop a space in the existing work for new research

The literature consists of the published works that document a scholarly conversation or progression on a problem or topic in a field of study. Among these are documents that explain the background and show the loose ends in the established research on which a proposed project is based. Although a literature review focuses on primary, peer -reviewed resources, it may begin with background subject information generally found in secondary and tertiary sources such as books and encyclopedias. Following that essential overview, the seminal literature of the field is explored. As a result, while a literature review may consist of research articles tightly focused on a topic with secondary and tertiary sources used more sparingly, all three types of information (primary, secondary, tertiary) are critical.

The literature review, often referred to as the Background or Introduction to a research paper that presents methods, materials, results and discussion, exists in every field and serves many functions in research writing.

Adapted from Frederiksen, L., & Phelps, S. F. (2017). Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students. Open Textbook Library

Review and Reinforce

Two common approaches are simply outlined here. Which seems more common? Which more productive? Why? A. Forward exploration 1. Sources on a topic or problem are gathered. 2. Salient themes are discovered. 3. Research gaps are considered for future research. B. Backward exploration 1. Sources pertaining to an existing research project are gathered. 2. The justification of the research project’s methods or materials are explained and supported based on previously documented research.

Media Attributions

- 2589960988_3eeca91ba4_o © Untitled blue is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

Sourcing, summarizing, and synthesizing: Skills for effective research writing Copyright © 2023 by Wendy L. McBride is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Aims and Objectives – A Guide for Academic Writing

- Doing a PhD

One of the most important aspects of a thesis, dissertation or research paper is the correct formulation of the aims and objectives. This is because your aims and objectives will establish the scope, depth and direction that your research will ultimately take. An effective set of aims and objectives will give your research focus and your reader clarity, with your aims indicating what is to be achieved, and your objectives indicating how it will be achieved.

Introduction

There is no getting away from the importance of the aims and objectives in determining the success of your research project. Unfortunately, however, it is an aspect that many students struggle with, and ultimately end up doing poorly. Given their importance, if you suspect that there is even the smallest possibility that you belong to this group of students, we strongly recommend you read this page in full.

This page describes what research aims and objectives are, how they differ from each other, how to write them correctly, and the common mistakes students make and how to avoid them. An example of a good aim and objectives from a past thesis has also been deconstructed to help your understanding.

What Are Aims and Objectives?

Research aims.

A research aim describes the main goal or the overarching purpose of your research project.

In doing so, it acts as a focal point for your research and provides your readers with clarity as to what your study is all about. Because of this, research aims are almost always located within its own subsection under the introduction section of a research document, regardless of whether it’s a thesis , a dissertation, or a research paper .

A research aim is usually formulated as a broad statement of the main goal of the research and can range in length from a single sentence to a short paragraph. Although the exact format may vary according to preference, they should all describe why your research is needed (i.e. the context), what it sets out to accomplish (the actual aim) and, briefly, how it intends to accomplish it (overview of your objectives).

To give an example, we have extracted the following research aim from a real PhD thesis:

Example of a Research Aim

The role of diametrical cup deformation as a factor to unsatisfactory implant performance has not been widely reported. The aim of this thesis was to gain an understanding of the diametrical deformation behaviour of acetabular cups and shells following impaction into the reamed acetabulum. The influence of a range of factors on deformation was investigated to ascertain if cup and shell deformation may be high enough to potentially contribute to early failure and high wear rates in metal-on-metal implants.

Note: Extracted with permission from thesis titled “T he Impact And Deformation Of Press-Fit Metal Acetabular Components ” produced by Dr H Hothi of previously Queen Mary University of London.

Research Objectives

Where a research aim specifies what your study will answer, research objectives specify how your study will answer it.

They divide your research aim into several smaller parts, each of which represents a key section of your research project. As a result, almost all research objectives take the form of a numbered list, with each item usually receiving its own chapter in a dissertation or thesis.

Following the example of the research aim shared above, here are it’s real research objectives as an example:

Example of a Research Objective

- Develop finite element models using explicit dynamics to mimic mallet blows during cup/shell insertion, initially using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum.

- Investigate the number, velocity and position of impacts needed to insert a cup.

- Determine the relationship between the size of interference between the cup and cavity and deformation for different cup types.

- Investigate the influence of non-uniform cup support and varying the orientation of the component in the cavity on deformation.

- Examine the influence of errors during reaming of the acetabulum which introduce ovality to the cavity.

- Determine the relationship between changes in the geometry of the component and deformation for different cup designs.

- Develop three dimensional pelvis models with non-uniform bone material properties from a range of patients with varying bone quality.

- Use the key parameters that influence deformation, as identified in the foam models to determine the range of deformations that may occur clinically using the anatomic models and if these deformations are clinically significant.

It’s worth noting that researchers sometimes use research questions instead of research objectives, or in other cases both. From a high-level perspective, research questions and research objectives make the same statements, but just in different formats.

Taking the first three research objectives as an example, they can be restructured into research questions as follows:

Restructuring Research Objectives as Research Questions

- Can finite element models using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum together with explicit dynamics be used to mimic mallet blows during cup/shell insertion?

- What is the number, velocity and position of impacts needed to insert a cup?

- What is the relationship between the size of interference between the cup and cavity and deformation for different cup types?

Difference Between Aims and Objectives

Hopefully the above explanations make clear the differences between aims and objectives, but to clarify:

- The research aim focus on what the research project is intended to achieve; research objectives focus on how the aim will be achieved.

- Research aims are relatively broad; research objectives are specific.

- Research aims focus on a project’s long-term outcomes; research objectives focus on its immediate, short-term outcomes.

- A research aim can be written in a single sentence or short paragraph; research objectives should be written as a numbered list.

How to Write Aims and Objectives

Before we discuss how to write a clear set of research aims and objectives, we should make it clear that there is no single way they must be written. Each researcher will approach their aims and objectives slightly differently, and often your supervisor will influence the formulation of yours on the basis of their own preferences.

Regardless, there are some basic principles that you should observe for good practice; these principles are described below.

Your aim should be made up of three parts that answer the below questions:

- Why is this research required?

- What is this research about?

- How are you going to do it?

The easiest way to achieve this would be to address each question in its own sentence, although it does not matter whether you combine them or write multiple sentences for each, the key is to address each one.

The first question, why , provides context to your research project, the second question, what , describes the aim of your research, and the last question, how , acts as an introduction to your objectives which will immediately follow.

Scroll through the image set below to see the ‘why, what and how’ associated with our research aim example.

Note: Your research aims need not be limited to one. Some individuals per to define one broad ‘overarching aim’ of a project and then adopt two or three specific research aims for their thesis or dissertation. Remember, however, that in order for your assessors to consider your research project complete, you will need to prove you have fulfilled all of the aims you set out to achieve. Therefore, while having more than one research aim is not necessarily disadvantageous, consider whether a single overarching one will do.

Research Objectives

Each of your research objectives should be SMART :

- Specific – is there any ambiguity in the action you are going to undertake, or is it focused and well-defined?

- Measurable – how will you measure progress and determine when you have achieved the action?

- Achievable – do you have the support, resources and facilities required to carry out the action?

- Relevant – is the action essential to the achievement of your research aim?

- Timebound – can you realistically complete the action in the available time alongside your other research tasks?

In addition to being SMART, your research objectives should start with a verb that helps communicate your intent. Common research verbs include:

Table of Research Verbs to Use in Aims and Objectives

Last, format your objectives into a numbered list. This is because when you write your thesis or dissertation, you will at times need to make reference to a specific research objective; structuring your research objectives in a numbered list will provide a clear way of doing this.

To bring all this together, let’s compare the first research objective in the previous example with the above guidance:

Checking Research Objective Example Against Recommended Approach

Research Objective:

1. Develop finite element models using explicit dynamics to mimic mallet blows during cup/shell insertion, initially using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum.

Checking Against Recommended Approach:

Q: Is it specific? A: Yes, it is clear what the student intends to do (produce a finite element model), why they intend to do it (mimic cup/shell blows) and their parameters have been well-defined ( using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum ).

Q: Is it measurable? A: Yes, it is clear that the research objective will be achieved once the finite element model is complete.

Q: Is it achievable? A: Yes, provided the student has access to a computer lab, modelling software and laboratory data.

Q: Is it relevant? A: Yes, mimicking impacts to a cup/shell is fundamental to the overall aim of understanding how they deform when impacted upon.

Q: Is it timebound? A: Yes, it is possible to create a limited-scope finite element model in a relatively short time, especially if you already have experience in modelling.

Q: Does it start with a verb? A: Yes, it starts with ‘develop’, which makes the intent of the objective immediately clear.

Q: Is it a numbered list? A: Yes, it is the first research objective in a list of eight.

Mistakes in Writing Research Aims and Objectives

1. making your research aim too broad.

Having a research aim too broad becomes very difficult to achieve. Normally, this occurs when a student develops their research aim before they have a good understanding of what they want to research. Remember that at the end of your project and during your viva defence , you will have to prove that you have achieved your research aims; if they are too broad, this will be an almost impossible task. In the early stages of your research project, your priority should be to narrow your study to a specific area. A good way to do this is to take the time to study existing literature, question their current approaches, findings and limitations, and consider whether there are any recurring gaps that could be investigated .

Note: Achieving a set of aims does not necessarily mean proving or disproving a theory or hypothesis, even if your research aim was to, but having done enough work to provide a useful and original insight into the principles that underlie your research aim.

2. Making Your Research Objectives Too Ambitious

Be realistic about what you can achieve in the time you have available. It is natural to want to set ambitious research objectives that require sophisticated data collection and analysis, but only completing this with six months before the end of your PhD registration period is not a worthwhile trade-off.

3. Formulating Repetitive Research Objectives

Each research objective should have its own purpose and distinct measurable outcome. To this effect, a common mistake is to form research objectives which have large amounts of overlap. This makes it difficult to determine when an objective is truly complete, and also presents challenges in estimating the duration of objectives when creating your project timeline. It also makes it difficult to structure your thesis into unique chapters, making it more challenging for you to write and for your audience to read.

Fortunately, this oversight can be easily avoided by using SMART objectives.

Hopefully, you now have a good idea of how to create an effective set of aims and objectives for your research project, whether it be a thesis, dissertation or research paper. While it may be tempting to dive directly into your research, spending time on getting your aims and objectives right will give your research clear direction. This won’t only reduce the likelihood of problems arising later down the line, but will also lead to a more thorough and coherent research project.

Finding a PhD has never been this easy – search for a PhD by keyword, location or academic area of interest.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

- Schools & departments

Literature review

A general guide on how to conduct and write a literature review.

Please check course or programme information and materials provided by teaching staff, including your project supervisor, for subject-specific guidance.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a piece of academic writing demonstrating knowledge and understanding of the academic literature on a specific topic placed in context. A literature review also includes a critical evaluation of the material; this is why it is called a literature review rather than a literature report. It is a process of reviewing the literature, as well as a form of writing.

To illustrate the difference between reporting and reviewing, think about television or film review articles. These articles include content such as a brief synopsis or the key points of the film or programme plus the critic’s own evaluation. Similarly the two main objectives of a literature review are firstly the content covering existing research, theories and evidence, and secondly your own critical evaluation and discussion of this content.

Usually a literature review forms a section or part of a dissertation, research project or long essay. However, it can also be set and assessed as a standalone piece of work.

What is the purpose of a literature review?

…your task is to build an argument, not a library. Rudestam, K.E. and Newton, R.R. (1992) Surviving your dissertation: A comprehensive guide to content and process. California: Sage, p49.

In a larger piece of written work, such as a dissertation or project, a literature review is usually one of the first tasks carried out after deciding on a topic. Reading combined with critical analysis can help to refine a topic and frame research questions. Conducting a literature review establishes your familiarity with and understanding of current research in a particular field before carrying out a new investigation. After doing a literature review, you should know what research has already been done and be able to identify what is unknown within your topic.

When doing and writing a literature review, it is good practice to:

- summarise and analyse previous research and theories;

- identify areas of controversy and contested claims;

- highlight any gaps that may exist in research to date.

Conducting a literature review

Focusing on different aspects of your literature review can be useful to help plan, develop, refine and write it. You can use and adapt the prompt questions in our worksheet below at different points in the process of researching and writing your review. These are suggestions to get you thinking and writing.

Developing and refining your literature review (pdf)

Developing and refining your literature review (Word)

Developing and refining your literature review (Word rtf)

Writing a literature review has a lot in common with other assignment tasks. There is advice on our other pages about thinking critically, reading strategies and academic writing. Our literature review top tips suggest some specific things you can do to help you submit a successful review.

Literature review top tips (pdf)

Literature review top tips (Word rtf)

Our reading page includes strategies and advice on using books and articles and a notes record sheet grid you can use.

Reading at university

The Academic writing page suggests ways to organise and structure information from a range of sources and how you can develop your argument as you read and write.

Academic writing

The Critical thinking page has advice on how to be a more critical researcher and a form you can use to help you think and break down the stages of developing your argument.

Critical thinking

As with other forms of academic writing, your literature review needs to demonstrate good academic practice by following the Code of Student Conduct and acknowledging the work of others through citing and referencing your sources.

Good academic practice

As with any writing task, you will need to review, edit and rewrite sections of your literature review. The Editing and proofreading page includes tips on how to do this and strategies for standing back and thinking about your structure and checking the flow of your argument.

Editing and proofreading

Guidance on literature searching from the University Library

The Academic Support Librarians have developed LibSmart I and II, Learn courses to help you develop and enhance your digital research skills and capabilities; from getting started with the Library to managing data for your dissertation.

Searching using the library’s DiscoverEd tool: DiscoverEd

Finding resources in your subject: Subject guides

The Academic Support Librarians also provide one-to-one appointments to help you develop your research strategies.

1 to 1 support for literature searching and systematic reviews

Advice to help you optimise use of Google Scholar, Google Books and Google for your research and study: Using Google

Managing and curating your references

A referencing management tool can help you to collect and organise and your source material to produce a bibliography or reference list.

Referencing and reference management

Information Services provide access to Cite them right online which is a guide to the main referencing systems and tells you how to reference just about any source (EASE log-in may be required).

Cite them right

Published study guides

There are a number of scholarship skills books and guides available which can help with writing a literature review. Our Resource List of study skills guides includes sections on Referencing, Dissertation and project writing and Literature reviews.

Study skills guides

This article was published on 2024-02-26

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

- How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

- Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

- Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

- Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

- Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

- Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

- Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

How to write a good literature review

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses.

Frequently asked questions

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.

The literature review format can vary depending on the specific publication guidelines. However, there are some common elements and structures that are often followed. Here is a general guideline for the format of a literature review: Introduction: Provide an overview of the topic. Define the scope and purpose of the literature review. State the research question or objective. Body: Organize the literature by themes, concepts, or chronology. Critically analyze and evaluate each source. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. Highlight any methodological limitations or biases. Identify patterns, connections, or contradictions in the existing research. Conclusion: Summarize the key points discussed in the literature review. Highlight the research gap. Address the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Highlight the contributions of the review and suggest directions for future research.

Both annotated bibliographies and literature reviews involve the examination of scholarly sources. While annotated bibliographies focus on individual sources with brief annotations, literature reviews provide a more in-depth, integrated, and comprehensive analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. The key differences are as follows:

References

- Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of criminal justice education , 24 (2), 218-234.

- Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Taylor & Francis.

- Cantero, C. (2019). How to write a literature review. San José State University Writing Center .

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- Life Sciences Papers: 9 Tips for Authors Writing in Biological Sciences

- What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how to avoid it, you may also like, measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, what is academic writing: tips for students, why traditional editorial process needs an upgrade, paperpal’s new ai research finder empowers authors to..., what is hedging in academic writing , how to use ai to enhance your college..., ai + human expertise – a paradigm shift..., how to use paperpal to generate emails &..., ai in education: it’s time to change the..., is it ethical to use ai-generated abstracts without....

Review Articles (Health Sciences)

- Finding Review Articles

- Goals of a Literature Review

- Select Citation Management Software

- Select databases to search

- Track your searches

- Conduct searches

- Select articles to include

- Extract information from articles

- Structure your review

- Find "fill-in" information

- Other sources and help

- Systematic Reviews

- Other types of reviews

Keeping these goals in mind throughout your project will help you stay organized and focused.

A literature review helps the author:

- Understand the scope, history, and present state of knowledge in a specific topic

- Understand application of research concepts such as statistical tests and methodological choices

- Create a research project that complements the existing research or fills in gaps

A literature review helps the reader:

- Understand how your research project fits into the existing knowledge and research in a field

- Understand that a topic is important/relevant to the world and persuade them to keep reading your project

- << Previous: Literature Reviews

- Next: Select Citation Management Software >>

- Last Updated: Apr 12, 2024 2:21 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/healthsciences/reviewarticles

- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Harvard Graduate School of Design - Frances Loeb Library

Write and Cite

- Literature Review

- Academic Integrity

- Citing Sources

- Fair Use, Permissions, and Copyright

- Writing Resources

- Grants and Fellowships

- Last Updated: Apr 26, 2024 10:28 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/gsd/write

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

How to write a literature review introduction (+ examples)

The introduction to a literature review serves as your reader’s guide through your academic work and thought process. Explore the significance of literature review introductions in review papers, academic papers, essays, theses, and dissertations. We delve into the purpose and necessity of these introductions, explore the essential components of literature review introductions, and provide step-by-step guidance on how to craft your own, along with examples.

Why you need an introduction for a literature review

When you need an introduction for a literature review, what to include in a literature review introduction, examples of literature review introductions, steps to write your own literature review introduction.

A literature review is a comprehensive examination of the international academic literature concerning a particular topic. It involves summarizing published works, theories, and concepts while also highlighting gaps and offering critical reflections.

In academic writing , the introduction for a literature review is an indispensable component. Effective academic writing requires proper paragraph structuring to guide your reader through your argumentation. This includes providing an introduction to your literature review.

It is imperative to remember that you should never start sharing your findings abruptly. Even if there isn’t a dedicated introduction section .

Instead, you should always offer some form of introduction to orient the reader and clarify what they can expect.

There are three main scenarios in which you need an introduction for a literature review:

- Academic literature review papers: When your literature review constitutes the entirety of an academic review paper, a more substantial introduction is necessary. This introduction should resemble the standard introduction found in regular academic papers.

- Literature review section in an academic paper or essay: While this section tends to be brief, it’s important to precede the detailed literature review with a few introductory sentences. This helps orient the reader before delving into the literature itself.

- Literature review chapter or section in your thesis/dissertation: Every thesis and dissertation includes a literature review component, which also requires a concise introduction to set the stage for the subsequent review.

You may also like: How to write a fantastic thesis introduction (+15 examples)

It is crucial to customize the content and depth of your literature review introduction according to the specific format of your academic work.

In practical terms, this implies, for instance, that the introduction in an academic literature review paper, especially one derived from a systematic literature review , is quite comprehensive. Particularly compared to the rather brief one or two introductory sentences that are often found at the beginning of a literature review section in a standard academic paper. The introduction to the literature review chapter in a thesis or dissertation again adheres to different standards.

Here’s a structured breakdown based on length and the necessary information:

Academic literature review paper

The introduction of an academic literature review paper, which does not rely on empirical data, often necessitates a more extensive introduction than the brief literature review introductions typically found in empirical papers. It should encompass:

- The research problem: Clearly articulate the problem or question that your literature review aims to address.

- The research gap: Highlight the existing gaps, limitations, or unresolved aspects within the current body of literature related to the research problem.

- The research relevance: Explain why the chosen research problem and its subsequent investigation through a literature review are significant and relevant in your academic field.

- The literature review method: If applicable, describe the methodology employed in your literature review, especially if it is a systematic review or follows a specific research framework.

- The main findings or insights of the literature review: Summarize the key discoveries, insights, or trends that have emerged from your comprehensive review of the literature.

- The main argument of the literature review: Conclude the introduction by outlining the primary argument or statement that your literature review will substantiate, linking it to the research problem and relevance you’ve established.

- Preview of the literature review’s structure: Offer a glimpse into the organization of the literature review paper, acting as a guide for the reader. This overview outlines the subsequent sections of the paper and provides an understanding of what to anticipate.

By addressing these elements, your introduction will provide a clear and structured overview of what readers can expect in your literature review paper.

Regular literature review section in an academic article or essay

Most academic articles or essays incorporate regular literature review sections, often placed after the introduction. These sections serve to establish a scholarly basis for the research or discussion within the paper.

In a standard 8000-word journal article, the literature review section typically spans between 750 and 1250 words. The first few sentences or the first paragraph within this section often serve as an introduction. It should encompass:

- An introduction to the topic: When delving into the academic literature on a specific topic, it’s important to provide a smooth transition that aids the reader in comprehending why certain aspects will be discussed within your literature review.

- The core argument: While literature review sections primarily synthesize the work of other scholars, they should consistently connect to your central argument. This central argument serves as the crux of your message or the key takeaway you want your readers to retain. By positioning it at the outset of the literature review section and systematically substantiating it with evidence, you not only enhance reader comprehension but also elevate overall readability. This primary argument can typically be distilled into 1-2 succinct sentences.

In some cases, you might include:

- Methodology: Details about the methodology used, but only if your literature review employed a specialized method. If your approach involved a broader overview without a systematic methodology, you can omit this section, thereby conserving word count.

By addressing these elements, your introduction will effectively integrate your literature review into the broader context of your academic paper or essay. This will, in turn, assist your reader in seamlessly following your overarching line of argumentation.

Introduction to a literature review chapter in thesis or dissertation

The literature review typically constitutes a distinct chapter within a thesis or dissertation. Often, it is Chapter 2 of a thesis or dissertation.

Some students choose to incorporate a brief introductory section at the beginning of each chapter, including the literature review chapter. Alternatively, others opt to seamlessly integrate the introduction into the initial sentences of the literature review itself. Both approaches are acceptable, provided that you incorporate the following elements:

- Purpose of the literature review and its relevance to the thesis/dissertation research: Explain the broader objectives of the literature review within the context of your research and how it contributes to your thesis or dissertation. Essentially, you’re telling the reader why this literature review is important and how it fits into the larger scope of your academic work.

- Primary argument: Succinctly communicate what you aim to prove, explain, or explore through the review of existing literature. This statement helps guide the reader’s understanding of the review’s purpose and what to expect from it.

- Preview of the literature review’s content: Provide a brief overview of the topics or themes that your literature review will cover. It’s like a roadmap for the reader, outlining the main areas of focus within the review. This preview can help the reader anticipate the structure and organization of your literature review.

- Methodology: If your literature review involved a specific research method, such as a systematic review or meta-analysis, you should briefly describe that methodology. However, this is not always necessary, especially if your literature review is more of a narrative synthesis without a distinct research method.

By addressing these elements, your introduction will empower your literature review to play a pivotal role in your thesis or dissertation research. It will accomplish this by integrating your research into the broader academic literature and providing a solid theoretical foundation for your work.

Comprehending the art of crafting your own literature review introduction becomes significantly more accessible when you have concrete examples to examine. Here, you will find several examples that meet, or in most cases, adhere to the criteria described earlier.

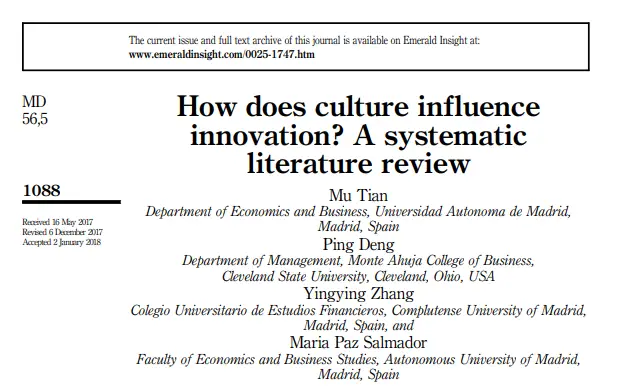

Example 1: An effective introduction for an academic literature review paper

To begin, let’s delve into the introduction of an academic literature review paper. We will examine the paper “How does culture influence innovation? A systematic literature review”, which was published in 2018 in the journal Management Decision.

The entire introduction spans 611 words and is divided into five paragraphs. In this introduction, the authors accomplish the following:

- In the first paragraph, the authors introduce the broader topic of the literature review, which focuses on innovation and its significance in the context of economic competition. They underscore the importance of this topic, highlighting its relevance for both researchers and policymakers.

- In the second paragraph, the authors narrow down their focus to emphasize the specific role of culture in relation to innovation.

- In the third paragraph, the authors identify research gaps, noting that existing studies are often fragmented and disconnected. They then emphasize the value of conducting a systematic literature review to enhance our understanding of the topic.

- In the fourth paragraph, the authors introduce their specific objectives and explain how their insights can benefit other researchers and business practitioners.

- In the fifth and final paragraph, the authors provide an overview of the paper’s organization and structure.

In summary, this introduction stands as a solid example. While the authors deviate from previewing their key findings (which is a common practice at least in the social sciences), they do effectively cover all the other previously mentioned points.

Example 2: An effective introduction to a literature review section in an academic paper

The second example represents a typical academic paper, encompassing not only a literature review section but also empirical data, a case study, and other elements. We will closely examine the introduction to the literature review section in the paper “The environmentalism of the subalterns: a case study of environmental activism in Eastern Kurdistan/Rojhelat”, which was published in 2021 in the journal Local Environment.

The paper begins with a general introduction and then proceeds to the literature review, designated by the authors as their conceptual framework. Of particular interest is the first paragraph of this conceptual framework, comprising 142 words across five sentences:

“ A peripheral and marginalised nationality within a multinational though-Persian dominated Iranian society, the Kurdish people of Iranian Kurdistan (a region referred by the Kurds as Rojhelat/Eastern Kurdi-stan) have since the early twentieth century been subject to multifaceted and systematic discriminatory and exclusionary state policy in Iran. This condition has left a population of 12–15 million Kurds in Iran suffering from structural inequalities, disenfranchisement and deprivation. Mismanagement of Kurdistan’s natural resources and the degradation of its natural environmental are among examples of this disenfranchisement. As asserted by Julian Agyeman (2005), structural inequalities that sustain the domination of political and economic elites often simultaneously result in environmental degradation, injustice and discrimination against subaltern communities. This study argues that the environmental struggle in Eastern Kurdistan can be asserted as a (sub)element of the Kurdish liberation movement in Iran. Conceptually this research is inspired by and has been conducted through the lens of ‘subalternity’ ” ( Hassaniyan, 2021, p. 931 ).

In this first paragraph, the author is doing the following:

- The author contextualises the research

- The author links the research focus to the international literature on structural inequalities

- The author clearly presents the argument of the research

- The author clarifies how the research is inspired by and uses the concept of ‘subalternity’.

Thus, the author successfully introduces the literature review, from which point onward it dives into the main concept (‘subalternity’) of the research, and reviews the literature on socio-economic justice and environmental degradation.

While introductions to a literature review section aren’t always required to offer the same level of study context detail as demonstrated here, this introduction serves as a commendable model for orienting the reader within the literature review. It effectively underscores the literature review’s significance within the context of the study being conducted.

Examples 3-5: Effective introductions to literature review chapters

The introduction to a literature review chapter can vary in length, depending largely on the overall length of the literature review chapter itself. For example, a master’s thesis typically features a more concise literature review, thus necessitating a shorter introduction. In contrast, a Ph.D. thesis, with its more extensive literature review, often includes a more detailed introduction.

Numerous universities offer online repositories where you can access theses and dissertations from previous years, serving as valuable sources of reference. Many of these repositories, however, may require you to log in through your university account. Nevertheless, a few open-access repositories are accessible to anyone, such as the one by the University of Manchester . It’s important to note though that copyright restrictions apply to these resources, just as they would with published papers.

Master’s thesis literature review introduction

The first example is “Benchmarking Asymmetrical Heating Models of Spider Pulsar Companions” by P. Sun, a master’s thesis completed at the University of Manchester on January 9, 2024. The author, P. Sun, introduces the literature review chapter very briefly but effectively:

PhD thesis literature review chapter introduction

The second example is Deep Learning on Semi-Structured Data and its Applications to Video-Game AI, Woof, W. (Author). 31 Dec 2020, a PhD thesis completed at the University of Manchester . In Chapter 2, the author offers a comprehensive introduction to the topic in four paragraphs, with the final paragraph serving as an overview of the chapter’s structure:

PhD thesis literature review introduction

The last example is the doctoral thesis Metacognitive strategies and beliefs: Child correlates and early experiences Chan, K. Y. M. (Author). 31 Dec 2020 . The author clearly conducted a systematic literature review, commencing the review section with a discussion of the methodology and approach employed in locating and analyzing the selected records.

Having absorbed all of this information, let’s recap the essential steps and offer a succinct guide on how to proceed with creating your literature review introduction:

- Contextualize your review : Begin by clearly identifying the academic context in which your literature review resides and determining the necessary information to include.

- Outline your structure : Develop a structured outline for your literature review, highlighting the essential information you plan to incorporate in your introduction.

- Literature review process : Conduct a rigorous literature review, reviewing and analyzing relevant sources.

- Summarize and abstract : After completing the review, synthesize the findings and abstract key insights, trends, and knowledge gaps from the literature.

- Craft the introduction : Write your literature review introduction with meticulous attention to the seamless integration of your review into the larger context of your work. Ensure that your introduction effectively elucidates your rationale for the chosen review topics and the underlying reasons guiding your selection.

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox!

Subscribe and receive Master Academia's quarterly newsletter.

The best answers to "What are your plans for the future?"

10 tips for engaging your audience in academic writing, related articles.

How to peer review an academic paper

PhD thesis types: Monograph and collection of articles

How to disagree with reviewers (with examples!)

How to introduce yourself in a conference presentation (in six simple steps)

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

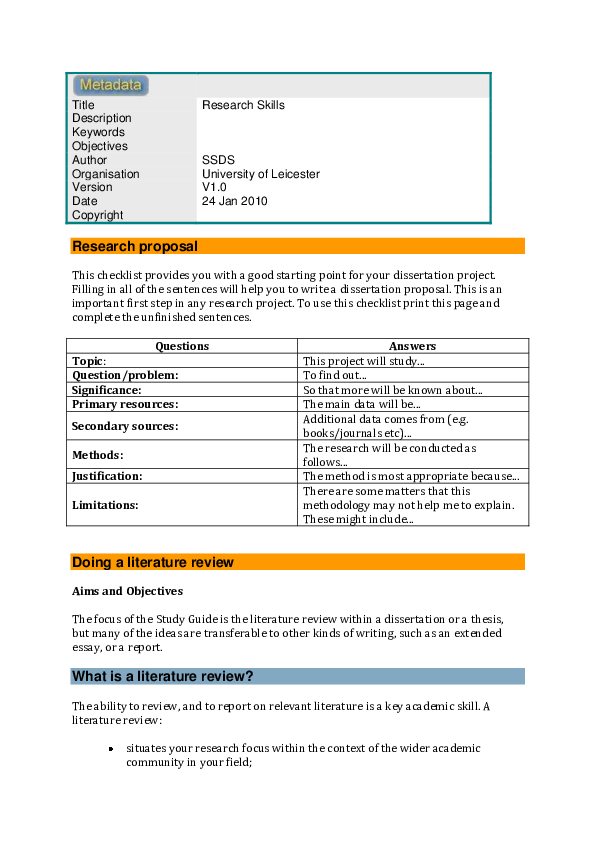

Doing a literature review Aims and Objectives What is a literature review

Related Papers

HUMANUS DISCOURSE

Humanus Discourse

The importance of literature review in academic writing of different categories, levels, and purposes cannot be overemphasized. The literature review establishes both the relevance and justifies why new research is relevant. It is through a literature review that a gap would be established, and which the new research would fix. Once the literature review sits properly in the research work, the objectives/research questions naturally fall into their proper perspective. Invariably, other chapters of the research work would be impacted as well. In most instances, scanning through literature also provides you with the need and justification for your research and may also well leave a hint for further research. Literature review in most instances exposes a researcher to the right methodology to use. The literature review is the nucleus of a research work that might when gotten right spotlights a work and can as well derail a research work when done wrongly. This paper seeks to unveil the practical guides to writing a literature review, from purpose, and components to tips. It follows through the exposition of secondary literature. It exposes the challenges in writing a literature review and at the same time recommended tips that when followed will impact the writing of the literature review.

Ignacio Illan Conde

Andrew Johnson

This chapter describes the process of writing a literature review and what the product should look like

Rebekka Tunombili

Cut Oktaviani

Abdullah Ramdhani , Tatam Chiway , Muhammad Ali Ramdhani

How to Practice Academic Medicine and Publish from Developing Countries?

In scientific writing, whether it is a research paper, thesis, or dissertation, it is important to investigate a problem that has not been tackled before—that is, to fill a gap in the current knowledge. The first question an editor or reviewer asks after seeing a submission is ‘Why did the authors do the work, is the subject original?’

Alfi Rahman

This Study Guide explains why literature reviews are needed, and how they can be conducted and reported. Related Study Guides are: Referencing and bibliographies, Avoiding plagiarism, Writing a dissertation, What is critical reading? What is critical writing? The focus of the Study Guide is the literature review within a dissertation or a thesis, but many of the ideas are transferable to other kinds of writing, such as an extended essay, or a report. After reading your literature review, it should be clear to the reader that you have up-to-date awareness of the relevant work of others, and that the research question you are asking is relevant. However, don't promise too much! Be wary of saying that your research will solve a problem, or that it will change practice. It would be safer and probably more realistic to say that your research will 'address a gap', rather than that it will 'fill a gap'.

A literature review is a critical consideration of the work by authors and researchers who have written on a particular topic. IT involves synthesising these writings so that a 'picture' of the issue under review forms. Therefore, it requires you to use summarising, analytical and evaluative skills. The effectiveness of these will, to a large extent, depend on your ability to link the work of various authors highlighting similarities, differences, strengths and weaknesses. A Literature Review is not a list describing or summarising one piece of literature after another, so avoid beginning each paragraph with the name of the researcher.

yakubu nawati

RELATED PAPERS

Revista Española de Educación Comparada

Marianne Teräs

Iulian Nichersu

Heidy Marin Castro

MIGUEL HERNÁNDEZ COMMUNICATION JOURNAL

Alberto Venegas Ramos

Khyber Medical University Journal

Avant: Journal of Philosophical-Interdisciplinary Vanguard

Adam Tuszyński

Asian Social Work and Policy Review

Sameena Azhar

Revista Facultad de Ciencias Económicas

Enrique Yañez Hurtado

Journal of Applied Polymer Science

Kentaro Taki

Akademik Tarih ve Araştırmalar Dergisi

Güngör Toplu

The American Journal of Gastroenterology

Pablo Oberti

Interface - Comunicação, Saúde, Educação

Mônica Mendes Gonçalves

Jurnal RISET Geologi dan Pertambangan

Dedi Mulyadi

IEEE Access

Paul B Gastin

cfilt.iitb.ac.in

Mahsa Yarmohammadi

Central European Journal of Public Health

Nikos Dedes

Marie-Christine Polge

Dominio de las Ciencias

Maria Proaño

Anna Desole

Journal of optics

Mao-kuo Wei

Infectious Diseases and Therapy

Alejandro Cane

Journal of Physical Science

Aniano Jr. Asor

Proceedings of the 35th European Peptide Symposium

Hugo Villar

hjhjgfg freghrf

Laura López Psicoanalista

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Research Aims, Objectives & Questions

The “Golden Thread” Explained Simply (+ Examples)

By: David Phair (PhD) and Alexandra Shaeffer (PhD) | June 2022

The research aims , objectives and research questions (collectively called the “golden thread”) are arguably the most important thing you need to get right when you’re crafting a research proposal , dissertation or thesis . We receive questions almost every day about this “holy trinity” of research and there’s certainly a lot of confusion out there, so we’ve crafted this post to help you navigate your way through the fog.

Overview: The Golden Thread

- What is the golden thread

- What are research aims ( examples )

- What are research objectives ( examples )

- What are research questions ( examples )

- The importance of alignment in the golden thread

What is the “golden thread”?

The golden thread simply refers to the collective research aims , research objectives , and research questions for any given project (i.e., a dissertation, thesis, or research paper ). These three elements are bundled together because it’s extremely important that they align with each other, and that the entire research project aligns with them.

Importantly, the golden thread needs to weave its way through the entirety of any research project , from start to end. In other words, it needs to be very clearly defined right at the beginning of the project (the topic ideation and proposal stage) and it needs to inform almost every decision throughout the rest of the project. For example, your research design and methodology will be heavily influenced by the golden thread (we’ll explain this in more detail later), as well as your literature review.

The research aims, objectives and research questions (the golden thread) define the focus and scope ( the delimitations ) of your research project. In other words, they help ringfence your dissertation or thesis to a relatively narrow domain, so that you can “go deep” and really dig into a specific problem or opportunity. They also help keep you on track , as they act as a litmus test for relevance. In other words, if you’re ever unsure whether to include something in your document, simply ask yourself the question, “does this contribute toward my research aims, objectives or questions?”. If it doesn’t, chances are you can drop it.

Alright, enough of the fluffy, conceptual stuff. Let’s get down to business and look at what exactly the research aims, objectives and questions are and outline a few examples to bring these concepts to life.