Solomon Asch Conformity Line Experiment Study

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Solomon Asch experimented with investigating the extent to which social pressure from a majority group could affect a person to conform .

He believed the main problem with Sherif’s (1935) conformity experiment was that there was no correct answer to the ambiguous autokinetic experiment. How could we be sure that a person conformed when there was no correct answer?

Asch (1951) devised what is now regarded as a classic experiment in social psychology, whereby there was an obvious answer to a line judgment task.

If the participant gave an incorrect answer, it would be clear that this was due to group pressure.

Experimental Procedure

Asch used a lab experiment to study conformity, whereby 50 male students from Swarthmore College in the USA participated in a ‘vision test.’

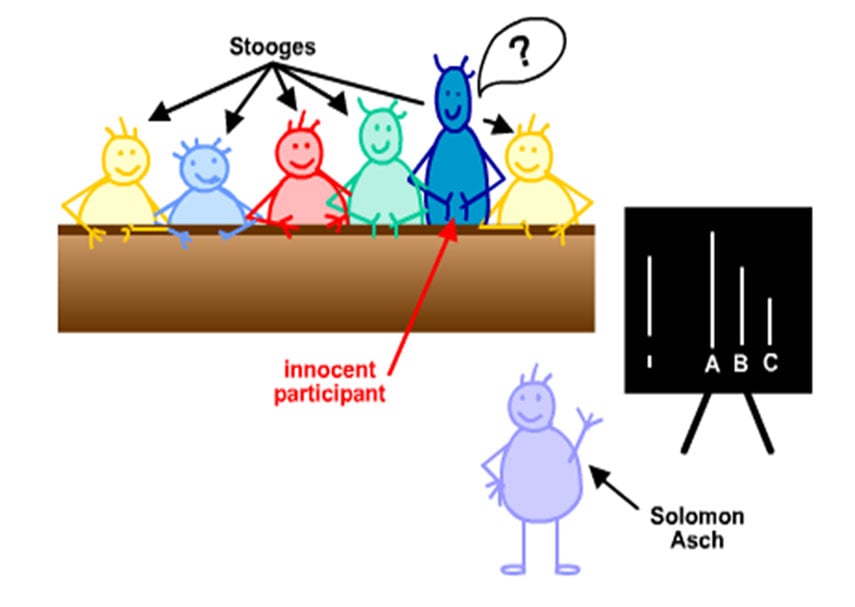

Using a line judgment task, Asch put a naive participant in a room with seven confederates/stooges. The confederates had agreed in advance what their responses would be when presented with the line task.

The real participant did not know this and was led to believe that the other seven confederates/stooges were also real participants like themselves.

Each person in the room had to state aloud which comparison line (A, B or C) was most like the target line. The answer was always obvious. The real participant sat at the end of the row and gave his or her answer last.

At the start, all participants (including the confederates) gave the correct answers. However, after a few rounds, the confederates started to provide unanimously incorrect answers.

There were 18 trials in total, and the confederates gave the wrong answer on 12 trials (called the critical trials). Asch was interested to see if the real participant would conform to the majority view.

Asch’s experiment also had a control condition where there were no confederates, only a “real participant.”

Asch measured the number of times each participant conformed to the majority view. On average, about one third (32%) of the participants who were placed in this situation went along and conformed with the clearly incorrect majority on the critical trials.

Over the 12 critical trials, about 75% of participants conformed at least once, and 25% of participants never conformed.

In the control group , with no pressure to conform to confederates, less than 1% of participants gave the wrong answer.

Why did the participants conform so readily? When they were interviewed after the experiment, most of them said that they did not really believe their conforming answers, but had gone along with the group for fear of being ridiculed or thought “peculiar.

A few of them said that they did believe the group’s answers were correct.

Apparently, people conform for two main reasons: because they want to fit in with the group ( normative influence ) and because they believe the group is better informed than they are ( informational influence ).

Critical Evaluation

One limitation of the study is that is used a biased sample. All the participants were male students who all belonged to the same age group. This means that the study lacks population validity and that the results cannot be generalized to females or older groups of people.

Another problem is that the experiment used an artificial task to measure conformity – judging line lengths. How often are we faced with making a judgment like the one Asch used, where the answer is plain to see?

This means that the study has low ecological validity and the results cannot be generalized to other real-life situations of conformity. Asch replied that he wanted to investigate a situation where the participants could be in no doubt what the correct answer was. In so doing he could explore the true limits of social influence.

Some critics thought the high levels of conformity found by Asch were a reflection of American, 1950’s culture and told us more about the historical and cultural climate of the USA in the 1950s than then they did about the phenomena of conformity.

In the 1950s America was very conservative, involved in an anti-communist witch-hunt (which became known as McCarthyism) against anyone who was thought to hold sympathetic left-wing views.

Perrin and Spencer

Conformity to American values was expected. Support for this comes from studies in the 1970s and 1980s that show lower conformity rates (e.g., Perrin & Spencer, 1980).

Perrin and Spencer (1980) suggested that the Asch effect was a “child of its time.” They carried out an exact replication of the original Asch experiment using engineering, mathematics, and chemistry students as subjects. They found that in only one out of 396 trials did an observer join the erroneous majority.

Perrin and Spencer argue that a cultural change has taken place in the value placed on conformity and obedience and in the position of students.

In America in the 1950s, students were unobtrusive members of society, whereas now, they occupy a free questioning role.

However, one problem in comparing this study with Asch is that very different types of participants are used. Perrin and Spencer used science and engineering students who might be expected to be more independent by training when it came to making perceptual judgments.

Finally, there are ethical issues : participants were not protected from psychological stress which may occur if they disagreed with the majority.

Evidence that participants in Asch-type situations are highly emotional was obtained by Back et al. (1963) who found that participants in the Asch situation had greatly increased levels of autonomic arousal.

This finding also suggests that they were in a conflict situation, finding it hard to decide whether to report what they saw or to conform to the opinion of others.

Asch also deceived the student volunteers claiming they were taking part in a “vision” test; the real purpose was to see how the “naive” participant would react to the behavior of the confederates. However, deception was necessary to produce valid results.

The clip below is not from the original experiment in 1951, but an acted version for television from the 1970s.

Factors Affecting Conformity

In further trials, Asch (1952, 1956) changed the procedure (i.e., independent variables) to investigate which situational factors influenced the level of conformity (dependent variable).

His results and conclusions are given below:

Asch (1956) found that group size influenced whether subjects conformed. The bigger the majority group (no of confederates), the more people conformed, but only up to a certain point.

With one other person (i.e., confederate) in the group conformity was 3%, with two others it increased to 13%, and with three or more it was 32% (or 1/3).

Optimum conformity effects (32%) were found with a majority of 3. Increasing the size of the majority beyond three did not increase the levels of conformity found. Brown and Byrne (1997) suggest that people might suspect collusion if the majority rises beyond three or four.

According to Hogg & Vaughan (1995), the most robust finding is that conformity reaches its full extent with 3-5 person majority, with additional members having little effect.

Lack of Group Unanimity / Presence of an Ally

The study also found that when any one individual differed from the majority, the power of conformity significantly decreased.

This showed that even a small dissent can reduce the power of a larger group, providing an important insight into how individuals can resist social pressure.

As conformity drops off with five members or more, it may be that it’s the unanimity of the group (the confederates all agree with each other) which is more important than the size of the group.

In another variation of the original experiment, Asch broke up the unanimity (total agreement) of the group by introducing a dissenting confederate.

Asch (1956) found that even the presence of just one confederate that goes against the majority choice can reduce conformity by as much as 80%.

For example, in the original experiment, 32% of participants conformed on the critical trials, whereas when one confederate gave the correct answer on all the critical trials conformity dropped to 5%.

This was supported in a study by Allen and Levine (1968). In their version of the experiment, they introduced a dissenting (disagreeing) confederate wearing thick-rimmed glasses – thus suggesting he was slightly visually impaired.

Even with this seemingly incompetent dissenter, conformity dropped from 97% to 64%. Clearly, the presence of an ally decreases conformity.

The absence of group unanimity lowers overall conformity as participants feel less need for social approval of the group (re: normative conformity).

Difficulty of Task

When the (comparison) lines (e.g., A, B, C) were made more similar in length it was harder to judge the correct answer and conformity increased.

When we are uncertain, it seems we look to others for confirmation. The more difficult the task, the greater the conformity.

Answer in Private

When participants were allowed to answer in private (so the rest of the group does not know their response), conformity decreased.

This is because there are fewer group pressures and normative influence is not as powerful, as there is no fear of rejection from the group.

Frequently Asked Questions

How has the asch conformity line experiment influenced our understanding of conformity.

The Asch conformity line experiment has shown that people are susceptible to conforming to group norms even when those norms are clearly incorrect. This experiment has significantly impacted our understanding of social influence and conformity, highlighting the powerful influence of group pressure on individual behavior.

It has helped researchers to understand the importance of social norms and group dynamics in shaping our beliefs and behaviors and has had a significant impact on the study of social psychology.

What are some real-world examples of conformity?

Examples of conformity in everyday life include following fashion trends, conforming to workplace norms, and adopting the beliefs and values of a particular social group. Other examples include conforming to peer pressure, following cultural traditions and customs, and conforming to societal expectations regarding gender roles and behavior.

Conformity can have both positive and negative effects on individuals and society, depending on the behavior’s context and consequences.

What are some of the negative effects of conformity?

Conformity can have negative effects on individuals and society. It can limit creativity and independent thinking, promote harmful social norms and practices, and prevent personal growth and self-expression.

Conforming to a group can also lead to “groupthink,” where the group prioritizes conformity over critical thinking and decision-making, which can result in poor choices.

Moreover, conformity can spread false information and harmful behavior within a group, as individuals may be afraid to challenge the group’s beliefs or actions.

How does conformity differ from obedience?

Conformity involves adjusting one’s behavior or beliefs to align with the norms of a group, even if those beliefs or behaviors are not consistent with one’s personal views. Obedience , on the other hand, involves following the orders or commands of an authority figure, often without question or critical thinking.

While conformity and obedience involve social influence, obedience is usually a response to an explicit request or demand from an authority figure, whereas conformity is a response to implicit social pressure from a group.

What is the Asch effect?

The Asch Effect is a term coined from the Asch Conformity Experiments conducted by Solomon Asch. It refers to the influence of a group majority on an individual’s judgment or behavior, such that the individual may conform to perceived group norms even when those norms are obviously incorrect or counter to the individual’s initial judgment.

This effect underscores the power of social pressure and the strong human tendency towards conformity in group settings.

What is Solomon Asch’s contribution to psychology?

Solomon Asch significantly contributed to psychology through his studies on social pressure and conformity.

His famous conformity experiments in the 1950s demonstrated how individuals often conform to the majority view, even when clearly incorrect.

His work has been fundamental to understanding social influence and group dynamics’ power in shaping individual behaviors and perceptions.

Allen, V. L., & Levine, J. M. (1968). Social support, dissent and conformity. Sociometry , 138-149.

Asch, S. E. (1951). Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgment. In H. Guetzkow (ed.) Groups, leadership and men . Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Press.

Asch, S. E. (1952). Group forces in the modification and distortion of judgments.

Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological monographs: General and applied, 70(9) , 1-70.

Back, K. W., Bogdonoff, M. D., Shaw, D. M., & Klein, R. F. (1963). An interpretation of experimental conformity through physiological measures. Behavioral Science, 8(1) , 34.

Bond, R., & Smith, P. B. (1996). Culture and conformity : A meta-analysis of studies using Asch’s (1952b, 1956) line judgment task. Psychological bulletin , 119 (1), 111.

Longman, W., Vaughan, G., & Hogg, M. (1995). Introduction to social psychology .

Perrin, S., & Spencer, C. (1980). The Asch effect: a child of its time? Bulletin of the British Psychological Society, 32, 405-406.

Sherif, M., & Sherif, C. W. (1953). Groups in harmony and tension . New York: Harper & Row.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Asch Conformity Experiments

What These Experiments Say About Group Behavior

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

What Is Conformity?

Factors that influence conformity.

The Asch conformity experiments were a series of psychological experiments conducted by Solomon Asch in the 1950s. The experiments revealed the degree to which a person's own opinions are influenced by those of a group . Asch found that people were willing to ignore reality and give an incorrect answer in order to conform to the rest of the group.

At a Glance

The Asch conformity experiments are among the most famous in psychology's history and have inspired a wealth of additional research on conformity and group behavior. This research has provided important insight into how, why, and when people conform and the effects of social pressure on behavior.

Do you think of yourself as a conformist or a non-conformist? Most people believe that they are non-conformist enough to stand up to a group when they know they are right, but conformist enough to blend in with the rest of their peers.

Research suggests that people are often much more prone to conform than they believe they might be.

Imagine yourself in this situation: You've signed up to participate in a psychology experiment in which you are asked to complete a vision test.

Seated in a room with the other participants, you are shown a line segment and then asked to choose the matching line from a group of three segments of different lengths.

The experimenter asks each participant individually to select the matching line segment. On some occasions, everyone in the group chooses the correct line, but occasionally, the other participants unanimously declare that a different line is actually the correct match.

So what do you do when the experimenter asks you which line is the right match? Do you go with your initial response, or do you choose to conform to the rest of the group?

Conformity in Psychology

In psychological terms, conformity refers to an individual's tendency to follow the unspoken rules or behaviors of the social group to which they belong. Researchers have long been been curious about the degree to which people follow or rebel against social norms.

Asch was interested in looking at how pressure from a group could lead people to conform, even when they knew that the rest of the group was wrong. The purpose of the Asch conformity experiment was to demonstrate the power of conformity in groups.

Methodology of Asch's Experiments

Asch's experiments involved having people who were in on the experiment pretend to be regular participants alongside those who were actual, unaware subjects of the study. Those that were in on the experiment would behave in certain ways to see if their actions had an influence on the actual experimental participants.

In each experiment, a naive student participant was placed in a room with several other confederates who were in on the experiment. The subjects were told that they were taking part in a "vision test." All told, a total of 50 students were part of Asch’s experimental condition.

The confederates were all told what their responses would be when the line task was presented. The naive participant, however, had no inkling that the other students were not real participants. After the line task was presented, each student verbally announced which line (either 1, 2, or 3) matched the target line.

Critical Trials

There were 18 different trials in the experimental condition , and the confederates gave incorrect responses in 12 of them, which Asch referred to as the "critical trials." The purpose of these critical trials was to see if the participants would change their answer in order to conform to how the others in the group responded.

During the first part of the procedure, the confederates answered the questions correctly. However, they eventually began providing incorrect answers based on how they had been instructed by the experimenters.

Control Condition

The study also included 37 participants in a control condition . In order to ensure that the average person could accurately gauge the length of the lines, the control group was asked to individually write down the correct match. According to these results, participants were very accurate in their line judgments, choosing the correct answer 99% of the time.

Results of the Asch Conformity Experiments

Nearly 75% of the participants in the conformity experiments went along with the rest of the group at least one time.

After combining the trials, the results indicated that participants conformed to the incorrect group answer approximately one-third of the time.

The experiments also looked at the effect that the number of people present in the group had on conformity. When just one confederate was present, there was virtually no impact on participants' answers. The presence of two confederates had only a tiny effect. The level of conformity seen with three or more confederates was far more significant.

Asch also found that having one of the confederates give the correct answer while the rest of the confederates gave the incorrect answer dramatically lowered conformity. In this situation, just 5% to 10% of the participants conformed to the rest of the group (depending on how often the ally answered correctly). Later studies have also supported this finding, suggesting that having social support is an important tool in combating conformity.

At the conclusion of the Asch experiments, participants were asked why they had gone along with the rest of the group. In most cases, the students stated that while they knew the rest of the group was wrong, they did not want to risk facing ridicule. A few of the participants suggested that they actually believed the other members of the group were correct in their answers.

These results suggest that conformity can be influenced both by a need to fit in and a belief that other people are smarter or better informed.

Given the level of conformity seen in Asch's experiments, conformity can be even stronger in real-life situations where stimuli are more ambiguous or more difficult to judge.

Asch went on to conduct further experiments in order to determine which factors influenced how and when people conform. He found that:

- Conformity tends to increase when more people are present . However, there is little change once the group size goes beyond four or five people.

- Conformity also increases when the task becomes more difficult . In the face of uncertainty, people turn to others for information about how to respond.

- Conformity increases when other members of the group are of a higher social status . When people view the others in the group as more powerful, influential, or knowledgeable than themselves, they are more likely to go along with the group.

- Conformity tends to decrease, however, when people are able to respond privately . Research has also shown that conformity decreases if people have support from at least one other individual in a group.

Criticisms of the Asch Conformity Experiments

One of the major criticisms of Asch's conformity experiments centers on the reasons why participants choose to conform. According to some critics, individuals may have actually been motivated to avoid conflict, rather than an actual desire to conform to the rest of the group.

Another criticism is that the results of the experiment in the lab may not generalize to real-world situations.

Many social psychology experts believe that while real-world situations may not be as clear-cut as they are in the lab, the actual social pressure to conform is probably much greater, which can dramatically increase conformist behaviors.

Asch SE. Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority . Psychological Monographs: General and Applied . 1956;70(9):1-70. doi:10.1037/h0093718

Morgan TJH, Laland KN, Harris PL. The development of adaptive conformity in young children: effects of uncertainty and consensus . Dev Sci. 2015;18(4):511-524. doi:10.1111/desc.12231

Asch SE. Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments . In: Guetzkow H, ed. Groups, Leadership and Men; Research in Human Relations. Carnegie Press. 1951:177–190.

Britt MA. Psych Experiments: From Pavlov's Dogs to Rorschach's Inkblots . Adams Media.

Myers DG. Exploring Psychology (9th ed.). Worth Publishers.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

6.5C: The Asch Experiment- The Power of Peer Pressure

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 8114

The Asch conformity experiments were a series of studies conducted in the 1950s that demonstrated the power of conformity in groups.

Learning Objectives

- Explain how the Asch experiment sought to measure conformity in groups

- The Asch conformity experiments consisted of a group “vision test”, where study participants were found to be more likely to conform to obviously wrong answers if first given by other “participants”, who were actually working for the experimenter.

- The experiment found that over a third of subjects conformed to giving a wrong answer.

In terms of gender, males show around half the effect of females (tested in same-sex groups). Conformity is also higher among members of an in-group.

- conformity : the ideology of adhering to one standard or social uniformity

Conducted by social psychologist Solomon Asch of Swarthmore College, the Asch conformity experiments were a series of studies published in the 1950s that demonstrated the power of conformity in groups. They are also known as the Asch paradigm. In the experiment, students were asked to participate in a group “vision test. ” In reality, all but one of the participants were working for Asch (i.e. confederates), and the study was really about how the remaining student would react to their behavior.

The original experiment was conducted with 123 male participants. Each participant was put into a group with five to seven confederates. The participants were shown a card with a line on it (the reference line), followed by another card with three lines on it labeled a, b, and c. The participants were then asked to say out loud which of the three lines matched in length the reference line, as well as other responses such as the length of the reference line to an everyday object, which lines were the same length, and so on.

Each line question was called a “trial. ” The “real” participant answered last or next to last. For the first two trials, the subject would feel at ease in the experiment, as he and the other “participants” gave the obvious, correct answer. On the third trial, all the confederates would start giving the same wrong answer. There were 18 trials in total and the confederates answered incorrectly for 12 of them. These 12 were known as the “critical trials. ”

The aim was to see whether the real participants would conform to the wrong answers of the confederates and change their answer to respond in the same way, despite it being the wrong answer.

Dr. Asch thought that the majority of people would not conform to something obviously wrong, but the results showed that only 24% of the participants did not conform on any trial. Seventy five percent conformed at least once, 5% conformed every time, and when surrounded by individuals all voicing an incorrect answer, participants provided incorrect responses on a high proportion of the questions (32%). Overall, there was a 37% conformity rate by subjects averaged across all critical trials. In a control group, with no pressure to conform to an erroneous answer, only one subject out of 35 ever gave an incorrect answer.

Study Variations

Variations of the basic paradigm tested how many cohorts were necessary to induce conformity, examining the influence of just one cohort and as many as fifteen. Results indicated that one cohort has virtually no influence and two cohorts have only a small influence. When three or more cohorts are present, the tendency to conform increases only modestly. The maximum effect occurs with four cohorts. Adding additional cohorts does not produce a stronger effect.

The unanimity of the confederates has also been varied. When the confederates are not unanimous in their judgment, even if only one confederate voices a different opinion, participants are much more likely to resist the urge to conform (only 5% to 10% conform) than when the confederates all agree. This result holds whether or not the dissenting confederate gives the correct answer. As long as the dissenting confederate gives an answer that is different from the majority, participants are more likely to give the correct answer.

This finding illuminates the power that even a small dissenting minority can have upon a larger group. This demonstrates the importance of privacy in answering important and life-changing questions, so that people do not feel pressured to conform. For example, anonymous surveys can allow people to fully express how they feel about a particular subject without fear of retribution or retaliation from others in the group or the larger society. Having a witness or ally (someone who agrees with the point of view) also makes it less likely that conformity will occur.

Interpretations

Asch suggested that this reflected poorly on factors such as education, which he thought must over-train conformity. Other researchers have argued that it is rational to use other people’s judgments as evidence. Others have suggested that the high conformity rate was due to social norms regarding politeness, which is consistent with subjects’ own claims that they did not actually believe the others’ judgments and were indeed merely conforming.

- Abnormal Psychology

- Assessment (IB)

- Biological Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminology

- Developmental Psychology

- Extended Essay

- General Interest

- Health Psychology

- Human Relationships

- IB Psychology

- IB Psychology HL Extensions

- Internal Assessment (IB)

- Love and Marriage

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Prejudice and Discrimination

- Qualitative Research Methods

- Research Methodology

- Revision and Exam Preparation

- Social and Cultural Psychology

- Studies and Theories

- Teaching Ideas

Key Study: Conformity – Asch (1955)

Travis Dixon October 4, 2016 Uncategorized

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

Background Information

Humans are social animals, formign groups and strong bonds naturally. As such, it’s not hard to see the many ways that belonging to a group is important. Conformity is one effect that can happen as a result of this need to belong. Conformity is when behaviour is modified in order to fit in with a larger group.

Methodology and Results

For the following experiments Asch used the same experimental paradigm using the line length cards (which has come to be known as the Asch Paradigm). It involves matching one line with one from a group of three.

Typical Experimental Condition

7 to 9 male college students get together in a room, but only one of them is a naïve subject – the rest are confederates. i.e. the subject thinks everyone is just there like him, but in actual fact they all know what is going on. They sit in a row at a large desk and face the experimenter who holds up cards like those in figure 1. The subject is near the end of the line, so by the time they have given their response they have heard the responses of most of the group. The first two “trials” the confederates give the right answer and it all appears a bit boring. On the third trial, however, they deliberately give the wrong answer. In total there are 18 trials, but only in 12 of these do the group deliberately give the wrong answer (when this happens it’s called a “critical trial”).

In Asch’s first experiment reported in his 1955 paper, there were 123 subjects from three different colleges. The results were as follows:

- When alone: almost 100% accurate (<1% error rate)

- When in the group, the subjects conformed 36.8% of the time

In the results above, there was a range of individual variability:

- About 25% of subjects never agreed with the group

- Some subjects always agreed with the group

The subjects were interviewed after each experiment so the researchers could find out more about why they went along with the group. However, these were not investigated extensively. In his report he makes some generalizations, saying confidence in one’s own opinion was one factor that would have influenced the rate of conformity. There were some who adopted the idea, “I am wrong, they are right” and so changed their answers accordingly. Other subjects changed their answers because they did want to spoil the researchers’ results.

Interestingly, all subjects who conformed underestimated the frequency with which they conformed to the group.

Asch wanted to explore two dynamics that he thought might influence conformity: group size and unanimity.

Experiment 2: Group Size

In this experiment this size of the “opposition” (i.e, number of confederates) ranged from 1 to 15. In this modification, when there was only one confederate the subjects did not change their answers but instead gave conflicting (and correct) responses. However, as the group grew the results changed:

- One confederate: almost 0% conformity

- Two confederates: 13.6% conformity

- Three confederates: 31.8% conformity

Interestingly, this positive correlation between group size and conformity rate only goes up until a group of four (i.e. three confederates, one subject). After more confederates are introduced the rate does not change and is around 30%. However, after 8 or more confederates the rate of conformity begins to drop.

Experiment 3: Unanimity

Unanimity is when all people are in agreement, so in this context it refers to the extent to which all confederates give the wrong answer. In this design, Asch introduced either another naïve subject or a confederate who was told to not give the wrong answer on the critical trials. The results showed that conformity rates dropped when this happened (the conformity rate was ¼ of that in the regular design). During post-experiment interviews it was revealed that subjects felt a sense of closeness and warmth with their “partner.”

Experiment 4: Dissent

Based on the results with a partner, Asch posed another interesting question: “Was the partner’s effect a consequence of his dissent, or was it related to his accuracy?” Dissent is going against what is commonly believed, so in this context it means breaking away from the group and giving different answers. To test the above question, Asch made more modifications. This time a confederate was told to be either a “compromising” or “extremist” dissenter.

- Compromising: going against the group but the difference in answers is close

- Extremist: going against the group and given a very different answer

Both conditions reduced conformity. Moreover, the extremist dissenter “produced a remarkable freeing of the subjects.” When there was an extreme dissenter conformity dropped to 9%.

Experiment 5: Gaining and Losing a Partner

At this point I think it’s important just to mention that all these modifications within the experiment were done on different subjects.

In this next design, Asch tested what would happen if a subject gains a fellow dissenter but then this partner decides to join the incorrect group. A confederate was told to answer correctly on the first 6 critical trials. During these trials, the subjects also had no problems going against the rest of the group and giving the correct answer. However, after 6 trials the dissenting confederate changed and began giving incorrect answers along with the rest of the group – and as a result so did the subject. Having lost the partner to the majority the subject’s conformity rate rose to a similar level as those in Experiment #1 (i.e. about 1/3).

Experiment 5b: Gaining and Losing a Partner from the Group

As a result of the questioning from the previous experiments (27 subjects in total), Asch decided to see what would happen if the partner left the room completely. It was announced at a certain point after giving the correct answer on a few trials the partner said he had an appointment with the dean and had to leave. While there were still errors made (i.e. the participant conformed), the rates were lower than when the partner joined the majority.

Experiment 6: Gradual Dissolution

Asch had all confederates begin by giving correct answers and gradually changing to incorrect ones. By the sixth trial all the confederates were now giving wrong answers. The results showed that as long as there was just one other person against the group the subject could stay independent. However, as soon as he lost all partners the conformity rates increased.

7: Degree of Inaccuracy

Asch hypothesized that if the group’s answers were wrong enough the conformity would disappear. However, even when the different in line lengths were 7 inches (18 cm) there were still participants who conformed.

The above studies provide some interesting insight into factors that influence conformity. Asch suggested the following factors might influence conformity and since this paper was published in 1955 these have been studied:

- Social and cultural factors (Bond and Smith)

- Personality and characte

Travis Dixon is an IB Psychology teacher, author, workshop leader, examiner and IA moderator.

The Asch Conformity Experiments

What Solomon Asch Demonstrated About Social Pressure

- Recommended Reading

- Key Concepts

- Major Sociologists

- News & Issues

- Research, Samples, and Statistics

- Archaeology

The Asch Conformity Experiments, conducted by psychologist Solomon Asch in the 1950s, demonstrated the power of conformity in groups and showed that even simple objective facts cannot withstand the distorting pressure of group influence.

The Experiment

In the experiments, groups of male university students were asked to participate in a perception test. In reality, all but one of the participants were "confederates" (collaborators with the experimenter who only pretended to be participants). The study was about how the remaining student would react to the behavior of the other "participants."

The participants of the experiment (the subject as well as the confederates) were seated in a classroom and were presented with a card with a simple vertical black line drawn on it. Then, they were given a second card with three lines of varying length labeled "A," "B," and "C." One line on the second card was the same length as that on the first, and the other two lines were obviously longer and shorter.

Participants were asked to state out loud in front of each other which line, A, B, or C, matched the length of the line on the first card. In each experimental case, the confederates answered first, and the real participant was seated so that he would answer last. In some cases, the confederates answered correctly, while in others, the answered incorrectly.

Asch's goal was to see if the real participant would be pressured to answer incorrectly in the instances when the Confederates did so, or whether their belief in their own perception and correctness would outweigh the social pressure provided by the responses of the other group members.

Asch found that one-third of real participants gave the same wrong answers as the Confederates at least half the time. Forty percent gave some wrong answers, and only one-fourth gave correct answers in defiance of the pressure to conform to the wrong answers provided by the group.

In interviews he conducted following the trials, Asch found that those that answered incorrectly, in conformance with the group, believed that the answers given by the Confederates were correct, some thought that they were suffering a lapse in perception for originally thinking an answer that differed from the group, while others admitted that they knew that they had the correct answer, but conformed to the incorrect answer because they didn't want to break from the majority.

The Asch experiments have been repeated many times over the years with students and non-students, old and young, and in groups of different sizes and different settings. The results are consistently the same with one-third to one-half of the participants making a judgment contrary to fact, yet in conformity with the group, demonstrating the strong power of social influences.

Connection to Sociology

The results of Asch's experiment resonate with what we know to be true about the nature of social forces and norms in our lives. The behavior and expectations of others shape how we think and act on a daily basis because what we observe among others teaches us what is normal , and expected of us. The results of the study also raise interesting questions and concerns about how knowledge is constructed and disseminated, and how we can address social problems that stem from conformity, among others.

Updated by Nicki Lisa Cole, Ph.D.

- 15 Major Sociological Studies and Publications

- High School Science Experiment Ideas

- Adult Ice Breaker Games for Classrooms, Meetings, and Conferences

- Understanding Socialization in Sociology

- 10 Common Test Mistakes

- What to Expect From MBA Classes

- Homeschool Myths

- The Slave Boy Experiment in Plato's 'Meno'

- Teaching Strategies to Promote Student Equity and Engagement

- The 49 Techniques from Teach Like a Champion

- The Milgram Experiment: How Far Will You Go to Obey an Order?

- Introduction to Sociology

- How to Prepare for a Test in 3 Months

- Notes on 'Ain't'

- 5 Bubble Sheet Tips for Test Answers

- Social Surveys: Questionnaires, Interviews, and Telephone Polls

Final dates! Join the tutor2u subject teams in London for a day of exam technique and revision at the cinema. Learn more →

Reference Library

Collections

- See what's new

- All Resources

- Student Resources

- Assessment Resources

- Teaching Resources

- CPD Courses

- Livestreams

Study notes, videos, interactive activities and more!

Psychology news, insights and enrichment

Currated collections of free resources

Browse resources by topic

- All Psychology Resources

Resource Selections

Currated lists of resources

Study Notes

Conformity - Asch (1951)

Last updated 6 Sept 2022

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share by Email

Asch (1951) conducted one of the most famous laboratory experiments examining conformity. He wanted to examine the extent to which social pressure from a majority, could affect a person to conform.

Asch’s sample consisted of 50 male students from Swarthmore College in America, who believed they were taking part in a vision test. Asch used a line judgement task, where he placed on real naïve participants in a room with seven confederates (actors), who had agreed their answers in advance. The real participant was deceived and was led to believe that the other seven people were also real participants. The real participant always sat second to last.

In turn, each person had to say out loud which line (A, B or C) was most like the target line in length.

Unlike Jenness’ experiment , the correct answer was always obvious. Each participant completed 18 trials and the confederates gave the same incorrect answer on 12 trials, called critical trials. Asch wanted to see if the real participant would conform to the majority view, even when the answer was clearly incorrect.

Asch measured the number of times each participant conformed to the majority view. On average, the real participants conformed to the incorrect answers on 32% of the critical trials. 74% of the participants conformed on at least one critical trial and 26% of the participants never conformed. Asch also used a control group, in which one real participant completed the same experiment without any confederates. He found that less than 1% of the participants gave an incorrect answer.

Asch interviewed his participants after the experiment to find out why they conformed. Most of the participants said that they knew their answers were incorrect, but they went along with the group in order to fit in, or because they thought they would be ridiculed. This confirms that participants conformed due to normative social influence and the desire to fit in.

Evaluation of Asch

Asch used a biased sample of 50 male students from Swarthmore College in America. Therefore, we cannot generalise the results to other populations, for example female students, and we are unable to conclude if female students would have conformed in a similar way to male students. As a result Asch’s sample lacks population validity and further research is required to determine whether males and females conform differently

Furthermore, it could be argued that Asch’s experiment has low levels of ecological validity . Asch’s test of conformity, a line judgement task, is an artificial task, which does not reflect conformity in everyday life. Consequently, we are unable to generalise the results of Asch to other real life situations, such as why people may start smoking or drinking around friends, and therefore these results are limited in their application to everyday life.

Finally, Asch’s research is ethically questionable. He broke several ethical guidelines , including: deception and protection from harm . Asch deliberately deceived his participants, saying that they were taking part in a vision test and not an experiment on conformity. Although it is seen as unethical to deceive participants, Asch’s experiment required deception in order to achieve valid results. If the participants were aware of the true aim they would have displayed demand characteristics and acted differently. In addition, Asch’s participants were not protected from psychological harm and many of the participants reporting feeling stressed when they disagreed with the majority. However, Asch interviewed all of his participants following the experiment to overcome this issue.

- Normative Social Influence

- Task Difficulty

You might also like

Conformity - variations of asch (1951), types of conformity, explanations for conformity, ethics and psychology, conformity - jenness (1932), conformity to social roles, conformity to social roles as investigated by zimbardo, resistance to social influence - social support, our subjects.

- › Criminology

- › Economics

- › Geography

- › Health & Social Care

- › Psychology

- › Sociology

- › Teaching & learning resources

- › Student revision workshops

- › Online student courses

- › CPD for teachers

- › Livestreams

- › Teaching jobs

Boston House, 214 High Street, Boston Spa, West Yorkshire, LS23 6AD Tel: 01937 848885

- › Contact us

- › Terms of use

- › Privacy & cookies

© 2002-2024 Tutor2u Limited. Company Reg no: 04489574. VAT reg no 816865400.

12.4 Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the Asch effect

- Define conformity and types of social influence

- Describe Stanley Milgram’s experiment and its implications

- Define groupthink, social facilitation, and social loafing

In this section, we discuss additional ways in which people influence others. The topics of conformity, social influence, obedience, and group processes demonstrate the power of the social situation to change our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. We begin this section with a discussion of a famous social psychology experiment that demonstrated how susceptible humans are to outside social pressures.

Solomon Asch conducted several experiments in the 1950s to determine how people are affected by the thoughts and behaviors of other people. In one study, a group of participants was shown a series of printed line segments of different lengths: a, b, and c ( Figure 12.17 ). Participants were then shown a fourth line segment: x. They were asked to identify which line segment from the first group (a, b, or c) most closely resembled the fourth line segment in length.

Each group of participants had only one true, naïve subject. The remaining members of the group were confederates of the researcher. A confederate is a person who is aware of the experiment and works for the researcher. Confederates are used to manipulate social situations as part of the research design, and the true, naïve participants believe that confederates are, like them, uninformed participants in the experiment. In Asch’s study, the confederates identified a line segment that was obviously shorter than the target line—a wrong answer. The naïve participant then had to identify aloud the line segment that best matched the target line segment.

How often do you think the true participant aligned with the confederates’ response? That is, how often do you think the group influenced the participant, and the participant gave the wrong answer? Asch (1955) found that 76% of participants conformed to group pressure at least once by indicating the incorrect line. Conformity is the change in a person’s behavior to go along with the group, even if he does not agree with the group. Why would people give the wrong answer? What factors would increase or decrease someone giving in or conforming to group pressure?

The Asch effect is the influence of the group majority on an individual’s judgment.

What factors make a person more likely to yield to group pressure? Research shows that the size of the majority, the presence of another dissenter, and the public or relatively private nature of responses are key influences on conformity.

- The size of the majority: The greater the number of people in the majority, the more likely an individual will conform. There is, however, an upper limit: a point where adding more members does not increase conformity. In Asch’s study, conformity increased with the number of people in the majority—up to seven individuals. At numbers beyond seven, conformity leveled off and decreased slightly (Asch, 1955).

- The presence of another dissenter: If there is at least one dissenter, conformity rates drop to near zero (Asch, 1955).

- The public or private nature of the responses: When responses are made publicly (in front of others), conformity is more likely; however, when responses are made privately (e.g., writing down the response), conformity is less likely (Deutsch & Gerard, 1955).

The finding that conformity is more likely to occur when responses are public than when they are private is the reason government elections require voting in secret, so we are not coerced by others ( Figure 12.18 ). The Asch effect can be easily seen in children when they have to publicly vote for something. For example, if the teacher asks whether the children would rather have extra recess, no homework, or candy, once a few children vote, the rest will comply and go with the majority. In a different classroom, the majority might vote differently, and most of the children would comply with that majority. When someone’s vote changes if it is made in public versus private, this is known as compliance. Compliance can be a form of conformity. Compliance is going along with a request or demand, even if you do not agree with the request. In Asch’s studies, the participants complied by giving the wrong answers, but privately did not accept that the obvious wrong answers were correct.

Now that you have learned about the Asch line experiments, why do you think the participants conformed? The correct answer to the line segment question was obvious, and it was an easy task. Researchers have categorized the motivation to conform into two types: normative social influence and informational social influence (Deutsch & Gerard, 1955).

In normative social influence , people conform to the group norm to fit in, to feel good, and to be accepted by the group. However, with informational social influence , people conform because they believe the group is competent and has the correct information, particularly when the task or situation is ambiguous. What type of social influence was operating in the Asch conformity studies? Since the line judgment task was unambiguous, participants did not need to rely on the group for information. Instead, participants complied to fit in and avoid ridicule, an instance of normative social influence.

An example of informational social influence may be what to do in an emergency situation. Imagine that you are in a movie theater watching a film and what seems to be smoke comes in the theater from under the emergency exit door. You are not certain that it is smoke—it might be a special effect for the movie, such as a fog machine. When you are uncertain you will tend to look at the behavior of others in the theater. If other people show concern and get up to leave, you are likely to do the same. However, if others seem unconcerned, you are likely to stay put and continue watching the movie ( Figure 12.19 ).

How would you have behaved if you were a participant in Asch’s study? Many students say they would not conform, that the study is outdated, and that people nowadays are more independent. To some extent this may be true. Research suggests that overall rates of conformity may have reduced since the time of Asch’s research. Furthermore, efforts to replicate Asch’s study have made it clear that many factors determine how likely it is that someone will demonstrate conformity to the group. These factors include the participant’s age, gender, and socio-cultural background (Bond & Smith, 1996; Larsen, 1990; Walker & Andrade, 1996).

Link to Learning

Watch this video of a replication of the Asch experiment to learn more.

Stanley Milgram’s Experiment

Conformity is one effect of the influence of others on our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Another form of social influence is obedience to authority. Obedience is the change of an individual’s behavior to comply with a demand by an authority figure. People often comply with the request because they are concerned about a consequence if they do not comply. To demonstrate this phenomenon, we review another classic social psychology experiment.

Stanley Milgram was a social psychology professor at Yale who was influenced by the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a Nazi war criminal. Eichmann’s defense for the atrocities he committed was that he was “just following orders.” Milgram (1963) wanted to test the validity of this defense, so he designed an experiment and initially recruited 40 men for his experiment. The volunteer participants were led to believe that they were participating in a study to improve learning and memory. The participants were told that they were to teach other students (learners) correct answers to a series of test items. The participants were shown how to use a device that they were told delivered electric shocks of different intensities to the learners. The participants were told to shock the learners if they gave a wrong answer to a test item—that the shock would help them to learn. The participants believed they gave the learners shocks, which increased in 15-volt increments, all the way up to 450 volts. The participants did not know that the learners were confederates and that the confederates did not actually receive shocks.

In response to a string of incorrect answers from the learners, the participants obediently and repeatedly shocked them. The confederate learners cried out for help, begged the participant teachers to stop, and even complained of heart trouble. Yet, when the researcher told the participant-teachers to continue the shock, 65% of the participants continued the shock to the maximum voltage and to the point that the learner became unresponsive ( Figure 12.20 ). What makes someone obey authority to the point of potentially causing serious harm to another person?

Several variations of the original Milgram experiment were conducted to test the boundaries of obedience. When certain features of the situation were changed, participants were less likely to continue to deliver shocks (Milgram, 1965). For example, when the setting of the experiment was moved to an off-campus office building, the percentage of participants who delivered the highest shock dropped to 48%. When the learner was in the same room as the teacher, the highest shock rate dropped to 40%. When the teachers’ and learners’ hands were touching, the highest shock rate dropped to 30%. When the researcher gave the orders by phone, the rate dropped to 23%. These variations show that when the humanity of the person being shocked was increased, obedience decreased. Similarly, when the authority of the experimenter decreased, so did obedience.

This case is still very applicable today. What does a person do if an authority figure orders something done? What if the person believes it is incorrect, or worse, unethical? In a study by Martin and Bull (2008), midwives privately filled out a questionnaire regarding best practices and expectations in delivering a baby. Then, a more senior midwife and supervisor asked the junior midwives to do something they had previously stated they were opposed to. Most of the junior midwives were obedient to authority, going against their own beliefs. Burger (2009) partially replicated this study. He found among a multicultural sample of women and men that their levels of obedience matched Milgram's research. Doliński et al. (2017) performed a replication of Burger's work in Poland and controlled for the gender of both participants and learners, and once again, results that were consistent with Milgram's original work were observed.

When in group settings, we are often influenced by the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of people around us. Whether it is due to normative or informational social influence, groups have power to influence individuals. Another phenomenon of group conformity is groupthink. Groupthink is the modification of the opinions of members of a group to align with what they believe is the group consensus (Janis, 1972). In group situations, the group often takes action that individuals would not perform outside the group setting because groups make more extreme decisions than individuals do. Moreover, groupthink can hinder opposing trains of thought. This elimination of diverse opinions contributes to faulty decision by the group.

Groupthink in the U.S. Government

There have been several instances of groupthink in the U.S. government. One example occurred when the United States led a small coalition of nations to invade Iraq in March 2003. This invasion occurred because a small group of advisors and former President George W. Bush were convinced that Iraq represented a significant terrorism threat with a large stockpile of weapons of mass destruction at its disposal. Although some of these individuals may have had some doubts about the credibility of the information available to them at the time, in the end, the group arrived at a consensus that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction and represented a significant threat to national security. It later came to light that Iraq did not have weapons of mass destruction, but not until the invasion was well underway. As a result, 6000 American soldiers were killed and many more civilians died. How did the Bush administration arrive at their conclusions? View this video of Colin Powell, 10 years after his famous United Nations speech, discussing the information he had at the time that his decisions were based on. ("CNN Official Interview: Colin Powell now regrets UN speech about WMDs," 2010).

Do you see evidence of groupthink?

Why does groupthink occur? There are several causes of groupthink, which makes it preventable. When the group is highly cohesive, or has a strong sense of connection, maintaining group harmony may become more important to the group than making sound decisions. If the group leader is directive and makes his opinions known, this may discourage group members from disagreeing with the leader. If the group is isolated from hearing alternative or new viewpoints, groupthink may be more likely. How do you know when groupthink is occurring?

There are several symptoms of groupthink including the following:

- perceiving the group as invulnerable or invincible—believing it can do no wrong

- believing the group is morally correct

- self-censorship by group members, such as withholding information to avoid disrupting the group consensus

- the quashing of dissenting group members’ opinions

- the shielding of the group leader from dissenting views

- perceiving an illusion of unanimity among group members

- holding stereotypes or negative attitudes toward the out-group or others’ with differing viewpoints (Janis, 1972)

Given the causes and symptoms of groupthink, how can it be avoided? There are several strategies that can improve group decision making including seeking outside opinions, voting in private, having the leader withhold position statements until all group members have voiced their views, conducting research on all viewpoints, weighing the costs and benefits of all options, and developing a contingency plan (Janis, 1972; Mitchell & Eckstein, 2009).

Group Polarization

Another phenomenon that occurs within group settings is group polarization. Group polarization (Teger & Pruitt, 1967) is the strengthening of an original group attitude after the discussion of views within a group. That is, if a group initially favors a viewpoint, after discussion the group consensus is likely a stronger endorsement of the viewpoint. Conversely, if the group was initially opposed to a viewpoint, group discussion would likely lead to stronger opposition. Group polarization explains many actions taken by groups that would not be undertaken by individuals. Group polarization can be observed at political conventions, when platforms of the party are supported by individuals who, when not in a group, would decline to support them. Recently, some theorists have argued that group polarization may be partly responsible for the extreme political partisanship that seems ubiquitous in modern society. Given that people can self-select media outlets that are most consistent with their own political views, they are less likely to encounter opposing viewpoints. Over time, this leads to a strengthening of their own perspective and of hostile attitudes and behaviors towards those with different political ideals. Remarkably, political polarization leads to open levels of discrimination that are on par with, or perhaps exceed, racial discrimination (Iyengar & Westwood, 2015). A more everyday example is a group’s discussion of how attractive someone is. Does your opinion change if you find someone attractive, but your friends do not agree? If your friends vociferously agree, might you then find this person even more attractive?

Social traps refer to situations that arise when individuals or groups of individuals behave in ways that are not in their best interest and that may have negative, long-term consequences. However, once established, a social trap is very difficult to escape. For example, following World War II, the United States and the former Soviet Union engaged in a nuclear arms race. While the presence of nuclear weapons is not in either party's best interest, once the arms race began, each country felt the need to continue producing nuclear weapons to protect itself from the other.

Social Loafing

Imagine you were just assigned a group project with other students whom you barely know. Everyone in your group will get the same grade. Are you the type who will do most of the work, even though the final grade will be shared? Or are you more likely to do less work because you know others will pick up the slack? Social loafing involves a reduction in individual output on tasks where contributions are pooled. Because each individual's efforts are not evaluated, individuals can become less motivated to perform well. Karau and Williams (1993) and Simms and Nichols (2014) reviewed the research on social loafing and discerned when it was least likely to happen. The researchers noted that social loafing could be alleviated if, among other situations, individuals knew their work would be assessed by a manager (in a workplace setting) or instructor (in a classroom setting), or if a manager or instructor required group members to complete self-evaluations.

The likelihood of social loafing in student work groups increases as the size of the group increases (Shepperd & Taylor, 1999). According to Karau and Williams (1993), college students were the population most likely to engage in social loafing. Their study also found that women and participants from collectivistic cultures were less likely to engage in social loafing, explaining that their group orientation may account for this.

College students could work around social loafing or “free-riding” by suggesting to their professors use of a flocking method to form groups. Harding (2018) compared groups of students who had self-selected into groups for class to those who had been formed by flocking, which involves assigning students to groups who have similar schedules and motivations. Not only did she find that students reported less “free riding,” but that they also did better in the group assignments compared to those whose groups were self-selected.

Interestingly, the opposite of social loafing occurs when the task is complex and difficult (Bond & Titus, 1983; Geen, 1989). In a group setting, such as the student work group, if your individual performance cannot be evaluated, there is less pressure for you to do well, and thus less anxiety or physiological arousal (Latané, Williams, & Harkens, 1979). This puts you in a relaxed state in which you can perform your best, if you choose (Zajonc, 1965). If the task is a difficult one, many people feel motivated and believe that their group needs their input to do well on a challenging project (Jackson & Williams, 1985).

Deindividuation

Another way that being part of a group can affect behavior is exhibited in instances in which deindividuation occurs. Deindividuation refers to situations in which a person may feel a sense of anonymity and therefore a reduction in accountability and sense of self when among others. Deindividuation is often pointed to in cases in which mob or riot-like behaviors occur (Zimbardo, 1969), but research on the subject and the role that deindividuation plays in such behaviors has resulted in inconsistent results (as discussed in Granström, Guvå, Hylander, & Rosander, 2009).

Table 12.2 summarizes the types of social influence you have learned about in this chapter.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Psychology 2e

- Publication date: Apr 22, 2020

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/12-4-conformity-compliance-and-obedience

© Jan 6, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The effects of information and social conformity on opinion change

Daniel j. mallinson.

1 School of Public Affairs, The Pennsylvania State University - Harrisburg, Middletown, Pennsylvania, United States of America

Peter K. Hatemi

2 Department of Biochemistry, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, United States of America

3 Department of Molecular Biology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, United States of America

4 Department of Political Science, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania, United States of America

Associated Data

Data are available from the corresponding author’s Harvard Dataverse ( http://dx.doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YVCPDT ).

Extant research shows that social pressures influence acts of political participation, such as turning out to vote. However, we know less about how conformity pressures affect one’s deeply held political values and opinions. Using a discussion-based experiment, we untangle the unique and combined effects of information and social pressure on a political opinion that is highly salient, politically charged, and part of one’s identity. We find that while information plays a role in changing a person’s opinion, the social delivery of that information has the greatest effect. Thirty three percent of individuals in our treatment condition change their opinion due to the social delivery of information, while ten percent respond only to social pressure and ten percent respond only to information. Participants that change their opinion due to social pressure in our experiment are more conservative politically, conscientious, and neurotic than those that did not.

Introduction

Information and persuasion are perhaps the most important drivers of opinion and behavioral changes. Far less attention, however, has been given to the role of social pressure in opinion change on politically-charged topics. This lacuna is important because humans have a demonstrated proclivity to conform to their peers when faced with social pressure. Be it in the boardroom or on Facebook, Solomon Asch and Muzafer Sherif’s classic studies hold true today. Individuals conform based on a desire to be liked by others, which Asch [ 1 , 2 ] called compliance (i.e., going along with the majority even if you do not accept their beliefs because you want to be accepted), or a desire to be right, which Sherif et al. [ 3 ] termed private acceptance (i.e., believing that the opinions of others may be more correct or informed than their own). These two broad schemas encompass many specific mechanisms, including, motivated reasoning, cognitive dissonance, utility maximization, conflict avoidance, and pursuit of positive relationships, among others. Information-based social influence and normative social influence (i.e., conformity pressure) both play important, albeit distinct, roles in the theories of compliance and private acceptance (see [ 4 ]). In both cases, humans exhibit conformity behavior; however only in private acceptance do they actually update their beliefs due to the social delivery of new information.

Extensions of Asch and Sherif’s path-breaking works have been widely applied across a number of behavioral domains [ 5 – 9 ], to include political participation. For example, significant attention has been focused on the import of conformity on voter turnout and participatory behaviors [ 10 ], including the effects of social pressure on the electoral behavior of ordinary citizens [ 11 – 15 ]. This body of work points to both the subtle and overt power of social influence on electoral behavior, yet little is known about the import of social conformity for politically charged topics in context-laden circumstances, particularly those that challenge one’s values and opinions.

Testing conformity pressure in the ideological and political identity domain may explicate whether the pressure to align with an otherwise unified group is different when dealing with politically charged topics versus context-free topics such as the size of a line or the movement of a ball of light [ 2 , 16 ]. Opinions on politically charged topics are complex, value laden, aligned with cultural norms, and not easily changed [ 17 – 21 ]. It remains unknown if the effects of social conformity pressures on political opinions are conditioned by the personal nature of the locus of pressure. To be sure, social conformity is a difficult concept to measure without live interaction. An observational approach makes it difficult to untangle if or how social pressure independently affects behaviors given these variegated casual mechanisms, and whether changes in opinion that result from social interaction are due to compliance or private acceptance. Nevertheless, experiments provide one means to gain insight into how and why opinion change occurs. Here, we undertake an experiment to test the extent to which opinion change is due to persuasion through new information, social conformity pressure, or a combination of the two in a more realistic extended discussion environment.

Conformity and political behavior

Both observational and experimental research has addressed different aspects of the impact of socially-delivered information on individual behavior. Observational analyses of social networks form the backbone of much of the recent research on social influence and political behavior. Sinclair [ 22 ], for instance, demonstrates that citizen networks convey a bounded set of political information. Individuals may turn to highly informed peers [ 23 ] or aggregate information from trusted friends and family [ 24 ] in order to reduce the cost of gathering the information required to engage in political behavior (e.g., voting). In turning to their network, they are open to privately accepting this useful information. Political information, however, is not the only type of information transmitted through personal networks. Social pressure helps the network induce compliance with desired social norms [ 25 – 27 ]. In this case, members of the network provide information regarding the group’s expectations for appropriate engagement in politics. Individuals that are concerned about whether or not the group will continue to accept them therefore conform out of a desire to be liked, broadly defined. Norms are often self-enforcing, with merely the perceived threat of potential sanctions being enough to regulate behavior through compliance and self-sanctioning [ 28 , 29 ].

The debate over the practicality and reality of deliberative democracy further highlights the importance of understanding the role of political conformity in public and elite discourse. Scholars and theorists argue that political decisions are improved and legitimized under a deliberative process [ 30 – 34 ], even though deliberation does not necessarily result in consensus [ 35 ]. The crux of democratic deliberation is that participants are engaging in a rational discussion of a political topic, which provides the opportunity for each to learn from the others and thus privately update their preferences (i.e., out of a desire to be right). It results in a collectively rational enterprise that allows groups to overcome the bounded rationality of individuals that would otherwise yield suboptimal decisions [ 36 ]. This requires participants to fully engage and freely share the information that they have with the group.

Hibbing and Theiss-Morse [ 37 ], however, raise important questions about the desirability of deliberation among the public. Using focus groups, they find that citizens more often than not wish to disengage from discussion when they face opposition to their opinions. Instead, they appear averse to participation in politics and instead desire a “stealth democracy,” whereby democratic procedures exist, but are not always visible. In this view, deliberative environments do not ensure the optimal outcome, and can even result in suboptimal outcomes. In fact, the authors point directly to the issue of intra-group conformity due to compliance as a culprit for this phenomenon. The coercive influence of social pressure during deliberation has been further identified in jury deliberations [ 38 , 39 ] and other small group settings [ 40 ].