You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

HSTORY T2 Gr. 12 Black Consciousness Essay

Grade 12: The Challenge of Black Consciousness to the Apartheid State (Essay) PPT

Do you have an educational app, video, ebook, course or eResource?

Contribute to the Western Cape Education Department's ePortal to make a difference.

Home Contact us Terms of Use Privacy Policy Western Cape Government © 2024. All rights reserved.

Steve Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement Grade 12 Essay Guide (Question and Answers)

Black Consciousness Movement Grade 12 Essay Guide (Question and Answers) and Summary: The Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) was a grassroots anti-Apartheid activist movement that emerged in South Africa in the mid-1960s out of the political vacuum created by the jailing and banning of the African National Congress and Pan Africanist Congress leadership after the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960.

Table of Contents

Steve Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement Summary: A Legacy of Empowerment and Resistance

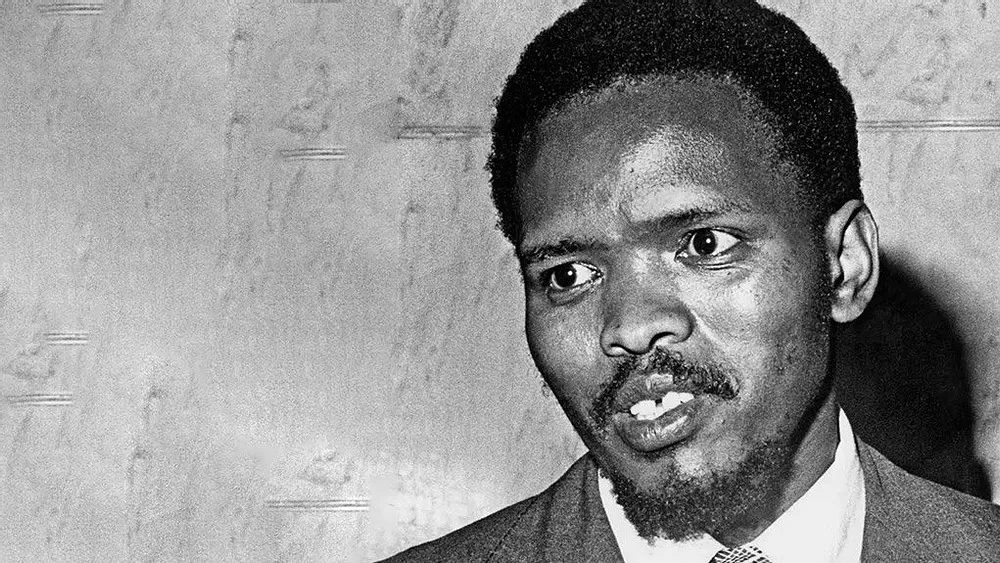

Stephen Bantu Biko , born in 1946 in South Africa, was a prominent anti-apartheid activist and leader of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) . The movement played a crucial role in the fight against apartheid by empowering black South Africans to embrace their identity, instilling pride and self-worth, and promoting resistance against the oppressive regime. This article will discuss Biko’s life, the origins and objectives of the Black Consciousness Movement, and the lasting impact of Biko’s ideas on South Africa and beyond.

Early Life and Influences

Steve Biko grew up in a society deeply divided along racial lines. From an early age, he was exposed to the harsh realities of apartheid, which inspired his lifelong commitment to fighting against racial oppression. As a student at Lovedale High School , Biko encountered the writings of Frantz Fanon , a psychiatrist and philosopher from Martinique who advocated for the liberation of colonized peoples through mental emancipation. Fanon’s ideas influenced Biko’s development of the Black Consciousness philosophy.

Formation of the Black Consciousness Movement

In 1968, Biko co-founded the South African Students’ Organisation (SASO) with other like-minded black students. SASO aimed to provide a platform for black students to challenge apartheid and create a sense of unity among them. The organization became the backbone of the Black Consciousness Movement, which sought to empower black South Africans by encouraging them to embrace their identity and value their cultural heritage. By fostering a strong sense of self-worth, the BCM aimed to break down the psychological barriers imposed by apartheid.

Philosophy and Goals

Central to the Black Consciousness Movement was the idea that black South Africans needed to liberate themselves from the mental chains of apartheid. The movement emphasized the importance of self-reliance and self-determination, rejecting the notion that white people were necessary for the liberation of black South Africans. Instead, Biko and the BCM insisted that black people could achieve freedom by developing their own solutions to the problems caused by apartheid.

Biko often spoke about the need to redefine “blackness” as a positive identity, fostering pride and unity among black South Africans. He also believed that social, political, and economic empowerment were essential for the liberation of black people, and that these goals could be achieved through community-based projects and initiatives.

Arrest, Death, and Legacy

The South African government saw Steve Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement as a significant threat to the apartheid regime. In 1973, Biko was banned from participating in political activities and confined to the Eastern Cape. Despite these restrictions, he continued to work clandestinely to advance the goals of the movement.

In August 1977, Biko was arrested, and on September 12, he died from a brain injury sustained while in police custody. His death sparked international outrage and galvanized the anti-apartheid movement, drawing global attention to the brutalities of the apartheid regime.

Today, Steve Biko is remembered as a martyr and a symbol of resistance against racial oppression. The Black Consciousness Movement played a crucial role in the fight against apartheid by empowering black South Africans to take control of their destiny. Biko’s ideas continue to inspire generations of activists worldwide, who strive for social justice and the eradication of racial inequality.

How Essays are Assessed in Grade 12

The essay will be assessed holistically (globally). This approach requires the teacher to score the overall product as a whole, without scoring the component parts separately. This approach encourages the learner to offer an individual opinion by using selected factual evidence to support an argument. The learner will not be required to simply regurgitate ‘facts’ in order to achieve a high mark. This approach discourages learners from preparing ‘model’ answers and reproducing them without taking into account the specific requirements of the question. Holistic marking of the essay credits learners’ opinions supported by evidence. Holistic assessment, unlike content-based marking, does not penalise language inadequacies as the emphasis is on the following:

- The construction of an argument

- The appropriate selection of factual evidence to support such an argument

- The learner’s interpretation of the question.

Steve Biko: Black Consciousness Movement Grade 12 Essay s Topics

Topic: the challenge of black consciousness to the apartheid state.

Introduction

K ey Definitions

- Civil protest : Opposition (usually against the current government’s policy) by ordinary citizens of a country

- Uprising : Mass action against government policy

- Bantu Homelands : Regions identified under the apartheid system as so-called homelands for different cultural and linguistic groups.

- Prohibition : order by which something may not be done; prohibit; declared illegal

- Resistance : When an individual or group of people work together against specific domination

- Exile : When someone is banished from their country

(Background)

- “South Africa as an apartheid state in 1970 to 1980

- 1978 PW Botha and launched his “Total Strategy”

- There were limited powers granted to the Colored, Indians and black township councils to ensure economic and political white supremacy

- Despite these reforms, Africans still did not gain any political rights outside their homelands

- Government’s response to violence against government reform policies – the declaration of a state of emergency in 1985:

- Banishment of the ANC and PAC to Sharpeville in 1960 – Underground Organizations

- Leaders of the Liberation Movements were in prisons or in exile

- New legislation – Terrorism Act – increases apartheid government’s power to suppress political opposition •Detention without trial – leads to the deaths of many activists

- Torture of activists in custody

- Increasing militarization within the country

- Bantu education ensures a low-paid labour force •Apartheid regime had total control

- In the late 1960s there was a new kind of resistance – The Black Consciousness Movement

( Nature and Objectives of Black Consciousness )

- In the late 1970s, a new generation of black students began to organize resistance

- Many were students at “forest college” established under the Bantu education system for black students such as the University of Zululand and the University of the North

- They accepted the Black Consciousness philosophy

- The term “black” was a direct dispute with the apartheid term “non-white”.

- “Black people” were all who were oppressed by apartheid – including Indians and coloured people

Black Consciousness Movement Grade 12 Questions

Question 1: how did the ideas of the black consciousness movement challenge the apartheid regime in the 1970.

How to answer and get good marks?

- Learners must use relevant evidence e.g. Uses relevant evidence that shows a thorough understanding of how the ideas of Black Consciousness challenged the apartheid regime in the 1970s .

- Learners must also use evidence very effectively in an organised paragraph that shows an understanding of the topic

When you answer, you should not ignore the following key facts where applicable:

- Black Consciousness wanted black South Africans to do things for themselves

- Black Consciousness wanted black South Africans to act independently of other races x Self-reliance promoted self-pride among black South Africans

SASO references can also be applicable (if sources are presented)

- SASO was formed to propagate the ideas of Black Consciousness

- To safeguard and promote the interests of black South Africans students

- SASO was based on the philosophy of Black Consciousness

- SASO was associated with Steve Biko

- SASO encouraged black South Africans students to be self-assertive

Question 2: How did the truth and reconciliation commision assist South Africa to come in terms with the past?

- To ensure healing and reconciliation among victims and perpetrators of political violence through confession

- The TRC encouraged the truth to be told

- Hoped to bring about forgiveness through healing

- To bring about ‘Reconciliation and National Unity’ among all South Africans

- Any other relevant response.

Download Black Consciousness Movement Grade 12 Essay Guide (Question and Answers) on pdf format

View all # History-Grade 12 Study Resources

We have compiled great resources for History Grade 12 students in one place. Find all Question Papers, Notes, Previous Tests, Annual Teaching Plans, and CAPS Documents.

More relevant sources

https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/steve-biko-the-black-consciousness-movement-steve-biko-foundation/AQp2i2l5?hl=en

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Black-Consciousness-movement

Don't miss these:

Services on Demand

Related links, hts theological studies, on-line version issn 2072-8050 print version issn 0259-9422, herv. teol. stud. vol.73 n.3 pretoria 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/hts.v73i3.4587 .

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

The legacy of Black Consciousness: Its continued relevance for democratic South Africa and its significance for theological education

Ramathate T. Dolamo

Department of Philosophy, Practical and Systematic Theology, University of South Africa, South Africa

Correspondence

This article argues that Black Consciousness as a philosophy transcends all political organisations and ideologies, because its architects were interested in rallying the whole country to fight apartheid regardless of political affiliation. The same consciousness that was raised in the 1960s could still influence political business today in democratic South Africa. To this end, a selection of values and principles of Black Consciousness has been examined that could be used in various sectors to ensure that our democracy is strengthened and protected. Some of those values and principles include: (1) a sense of solidarity in the face of adversity; before 1994, it was apartheid and today it is poverty; (2) the importance of the value of self-reliance in the face of unemployment and joblessness; (3) the value of self-understanding in Africa and globally as a country and (4) the critical role that education plays towards the total liberation of the whole person.

Introduction

Black Consciousness (BC) was largely a continuation of the struggle for national liberation in South Africa that had been waged by liberation movements such as the African National Congress (ANC), Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) and South African Communist Party (SACP). The difference was the approach adopted, and the methods and tactics used. Otherwise, the vision was the same, namely that the oppressed black majority were to be liberated from white supremacy. It was a philosophy that was infused in the young people in secondary schools and institutions of higher learning in the 1960s. Like the liberation movements that preceded it, BC was responding to slavery, colonialism, apartheid and collaborators with the apartheid regime such as the 'homeland' leaders and white liberals. In the 400 years or so before this, black South Africans had experienced great losses: life and limb, land, dignity and pride, self-respect, botho/ubuntu , culture, religion, political freedom and self-determination, self-reliance, and so on. In this era of democracy neo-colonialism, capitalism, the free market and its attendant neo-liberal policies are continuing to wreak havoc and perpetuate, and even deepen the gap between the rich and the poor. The black people who are in government and parliament have political power but lack economic power. Hence, some of the values and principles of BC should be revisited to determine to what extent they could be utilised to address existential challenges and problems that South Africa faces today. BC philosophy should be taught at schools and institutions of higher learning, which would make it pivotal in achieving a decolonised and empowering education.

Origins of Black Consciousness

The first paragraph of the preface to his book Politics of Black Nationalism: From Harlem to Soweto , Abraham (2003) states emphatically:

Black history did not begin, as pseudo-historians would have us believe, with the colonial encounter. The colonial period was preceded by a long and glorious black past, extending from ancient times to the 16th century. During this period, African states had evolved refined and sophisticated political and economic organisations and rich and varied cultural artifacts. The concept of 'slavery' as defined and propagated during the colonial epoch was virtually nonexistent.

Although BC as a formalised philosophy was an initiative of students and youths in the 1960s, its roots go back many years before that, a point we will elaborate on later. Stephen Bantu Biko, who was born on 18 December 1946 at Ginsberg near King William's Town in the Eastern Cape, was the initiator and cofounder of BC. He was killed for his political convictions while in police detention on 12 September 1977 (Stubbs 1978:2; Wilson 1991:15).

Defining BC, Biko (1978j) explains:

(it) is an attitude of mind and a way of life, the most positive call to emanate from the black world for a long time. Its essence is the realization by the black man of the need to rally with his brothers around the cause of their oppression - the blackness of their skin - and to operate as a group to rid themselves of the shackles that bind them to perpetual servitude. It is based on a self-examination which has ultimately led them to believe that by seeking to run away from themselves and emulate the white man, they are insulting the intelligence of whoever created them black. (p. 92)

Halisi (1991) makes the point from a psychological perspective:

The central contention of Black Consciousness philosophy was that resignation to racial domination was rooted in self-hatred and this had major political implications: the black person's low sense of self-esteem fostered political disunity, allowed ethnic leaders and other moderates to usurp the role of spokespersons for the black masses, and encourage a dependence on white leadership. Conversely, a heightened sense of racial awareness would encourage greater solidarity and mobilize mass commitment to the process of liberation. (p. 100)

Moodley (1991:152) concurs that BC helped the black masses to shed an internalised colonial mentality and it laid the ground for the self-confident challenge to the apartheid state. 'This self-empowering, vibrant, reconstructionist worldview emphasized the potential role of black initiative in responsibility in articulating the power of the powerless' (Moodley 1991:143). Moodley (1991) adds that this resolution was taken against the background of such claims as the following:

… blacks were portrayed as innately inferior, accustomed to de-humanized living, sexually promiscuous, intellectually limited, and prone to violence. Blackness symbolized evil, demise, chaos, corruption and uncleanliness, in contrast to whiteness which equaled order, wealth, purity, goodness, cleanliness and epitome of beauty. (p. 143)

The year 1652 is regarded as the beginning of the history of the black struggle against slavery, colonialism and apartheid. This was the year in which white people landed at the southernmost tip of Africa and began to settle there (Marsh 2013:207-208). The year is engrained in the minds and hearts of black people and there are deep scars to prove it. 'Colonialism and conquest brought about immense changes in the African societies of Southern Africa, impacting radically on their economies, cultures, thoughts and ways of life' (Odendaal 2012:9); elsewhere he mentioned that 'indigenous people had been subjugated, enslaved, deprived of their land and freedom, even in places exterminated, all in the name of Western civilization and progress' (2012:3). Mzimela (1983) concurs: 'Everywhere where people have been colonised, they have been economically exploited, politically oppressed and racially discriminated against' (p. 192). The Land Acts of 1913 and 1936 ensured that black people were stripped of 87% of their land (Changuion & Steenkamp 2012:130-139, 163-175) and when the National Party came into power in 1948, racism in the form of apartheid was institutionalised (Changuion & Steenkamp 2012:86-200). South Africa's ethnic groups were moulded into 'homelands' that would be given some autonomy and indeed some of them, such as Transkei, Venda, Ciskei and Bophuthatswana, were given their 'independence' by 'white' South Africa (Changuion & Steenkamp 2012:214-231, 232-250), while Indians and so-called Coloureds were to some extent accommodated in the central government through what was known as the Tricameral Parliament (Changuion & Steenkamp 2012:252-253).

While the National Party was in power, it employed various strategies to fight against groups and individuals who were opposed to racism and white supremacy. The ANC and the PAC were banned after the Sharpeville massacre in 1960 and they went underground and formed resistance armies, namely, Umkhonto we Sizwe and POQO, respectively. The years 1960-1990 were particularly brutal and cruel for liberation movements and some individuals. Thousands went into exile after the 1976 student uprisings, and others were imprisoned both inland and on Robben Island. A great fear engulfed the whole country and people were left paralysed (cf. Brotz 1977; Davenport 1987; Lodge 1983; Motsoko 1984) and yet as Suttner (2008) correctly maintains, even at this time of pathological fear, the ANC was busy underground with its political education and the armed struggle, both inside and outside the country. That was the moment when BC came fully into the picture and as a movement it was initially allowed to operate, because the government thought that it was a movement aligned with the apartheid ideology of separate development.

Black Consciousness and the liberation struggle

A number of the then young people such as Nyameko Pityana, Mamphela Ramphele, Sabelo Ntwasa and Bennie Khoapa, led by Steve Biko, reflected on the situation in the country as it was during the 1960s and the 1970s. They read widely about African politics as well as global trends and in particular engaged with the politics of African Americans. For example, Biko is said to have read in one night the 460 pages of Autobiography of Malcom X (Sono 1993:95). Black Power ideology, Kwame Ture, Charles V. Hamilton, Franz Fanon, Martin Luther King Jnr, Paulo Freire and Elijah Muhammad were read with so much passion that when Sono evaluates BC, he comes to the conclusion that it is a 100% import from America (1993:37). They also read the works and followed the praxis of sub-Saharan African leaders whose countries were being liberated from the colonial yoke, starting with Ghana, which was the first to be decolonised when Britain granted it independence in 1957. As a result, leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah, Julius Nyerere and Leopold Senghor served as role models for those young people in South Africa (Sono 1993:37). Pityana (2008:7) adds to this list of influences on BC the Ethiopian Movement, the ANC and the PAC. Khoapa (2008) says that after studying and reflecting on all these happenings, it was concluded that:

For the oppressed the meaning of the struggle against dehumanization is located in the great humanistic and historical task of liberating both themselves and their oppressors. The object of the struggle is to create an order that dehumanizes no one. (p. 75)

Or put differently by Sibisi (1991):

True liberation of both the oppressed and the oppressors in South Africa will entail a recognition by both parties of the full humanity of each individual, regardless of race, class or gender. (p. 136)

The 'pathological fear' (Pityana 2008:5) that gripped the black citizenry had to be dealt with on the psychological level even before an attempt could be made at physically removing the shackles of oppression, for 'the most potent weapon of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed'. This fear had undermined the dignity of black people and negated their humanity (Pityana 2008:6). Biko (1978h:77-79) likened apartheid to Nazism, a thesis that is treated fully by Mzimela (1983) in his doctoral study. The situation was untenable in as far as these commentators were concerned. Biko and his fellow students decided that enough was enough and that they had to make a move against the white minority regime. They decided to cancel their membership of multiracial organisations such as the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS) and the University Christian Movement (UCM) to form an exclusive black student organisation called the South African Students' Organization (SASO) in July 1969, and Biko became the organisation's first president (Biko 1978g:67; Seleoane 2008:33-34; Sono 1993:31). SASO would offer black people a platform to discuss issues peculiar to themselves, because they felt that NUSAS and UCM were preoccupied mainly with issues affecting white people.

The racial orientation and composition of SASO was a blessing in disguise, because the apartheid regime was fooled into believing that it was formed in line with the policy of separate development (Biko 1978a:5-11). But as students graduated, a concern was raised as to what would happen to them in their places of work and influence. What BC had imparted needed to be perpetuated beyond the confines of a classroom. To this end, the Black People's Convention (BPC) was launched in December 1971 (Sono 1993:81). Later, the Azanian People's Organization (AZAPO) was launched as a political party and this was followed by the establishment of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM). With the formation of the United Democratic Front (UDF) in 1983, the struggle was taken to a higher level. All these gains were achieved in spite of the apartheid regime's crackdown on liberation organisations, their leaders, proliberation media and the death in detention of leaders such as Biko (Buthelezi 1991:129). Buthelezi (1991) puts it succinctly when he says:

The BCM can be said to have prepared the way for the bolder moves of the 1970s and 1980s, which culminated in the events of the 1990s. The impact of BCM goes beyond particular organizations. (p. 129)

Ideological underpinnings

Biko qualified from the outset what BC means by 'blackness'. There are people who think about BC as supportive of the policy of apartheid and those who think about BC as racially exclusive, but nothing could be further from the truth. Biko (1978e) writes:

We have in our [ SASO ] policy manifesto defined blacks as those who by law or tradition, politically, economically and socially are discriminated against as a group in South African society and identify themselves as a unit in the struggle towards the realization of their aspirations. (p. 48)

And he emphasises that 'What Black Consciousness seeks to do is to produce at the output end of the process real black people who do not regard themselves as appendages to white society' (1978e:51).

It is in the same vein that Biko called upon all black people - that is, Africans, Indians and so-called Coloureds - to unite in solidarity against the government that pitted them against each other (Biko 1978c:33-39; 1978e:52). But he emphasises that 'blackness' is not a matter of pigmentation but a mental attitude (cf. also Moodley 1991:145). It is therefore not all people with black skins that qualify for blackness, for the purpose of this contextual definition (cf. Pityana 2008:10). People who are immediately excluded from this blackness were 'homeland' leaders who agreed to work within the apartheid system to separate black people according to their ethnic groupings (Biko 1978i:80-86). This would explain why Themba Sono was summarily removed as president of SASO when he argued that the organisation should be sympathetic to the homeland leaders and cooperate with them (Sono 1993:97). On the psychological and spiritual level, Biko (1978e) says:

Black Consciousness takes cognizance of the deliberateness of God's plan in creating black people black. It seeks to infuse the black community with a new formed pride in themselves their efforts, their religion and their outlook to life. (p. 49)

According to Biko (1978j), there is no white person who can qualify as black, even white liberals such as Donald Woods and Aelred Stubbs, mainly for the following reasons. Firstly, no white person could experience the oppression that black people were enduring, no matter how sympathetic or empathetic they were. Statements such as those made to the British audience by the celebrated white liberal, Alan Paton, when he said that apartheid should be given a chance because it could work, flew in the face of BC principles. For Paton, SASO was a product of a segregationist and racist mentality. It was myopic and ungrateful for what white people were doing for them. Unfortunately even today, 22 years into democracy, this white supremacist mentality is still prevalent among white liberals. Helen Zille, a respected politician of a white liberal party, tweeted that colonialism had done very much for black people, which is a stark example of how much work still needs to be done to eradicate racism. Secondly, Biko regarded white people as inherently paternalistic and condescending to black people, because black people were regarded as inferior and would forever need white tutelage. Thirdly, all white people were beneficiaries of apartheid and therefore their involvement in the struggle would be half-hearted and they would only seek superficial change. And fourthly, white people doubted the capabilities of black people and claimed that there is no way that black people could be trusted with the responsibility of running a complex and complicated country like South Africa (Biko 1978:88-91; Khoapa 2008:82-87). However, Biko (1978b) did not rule out completely the role that white people could play and he says that 'all true liberals should realise that the place for their fight for justice is within their white society' (p. 25). This message was taken to heart, because many liberals joined anti-apartheid organisations both nationally and internationally. NUSAS, UCM, the Progressive Party, Beyers Naudé, Zac de Beer, the Christian Institute responded cautiously to BC. They:

were wise enough to adopt a charitable and paternalistic attitude to the movement, and simultaneously to keep firing harsh salvos at the apartheid government, accusing it of having created this Black Consciousness phenomenon. (Sono 1993:67)

Black Consciousness for life-long empowering education

From the BC perspective, much was done in terms of rewriting and reinterpreting African history, redefining African cultures and salvaging African religion (cf. Biko 1978e:40-47; 1978f:54-60; 1978j:87-89; Buthelezi 1991:111-129; Khoapa 2008:73-87; Pityana 2008:1-14; Seleoane 2008:15-56). The contention here is that BC in this era of democracy can still contribute significantly towards the empowerment of South Africa's poor black majority, of course, in collaboration with other parties in the public and private sectors.

Without going into the complexities and indeed intricacies of what is meant by 'de-colonial education', one would like to identify elements of such a curriculum as articulated by BC over the last four decades. Throughout the continent, there has been and still there is a strong call for a decolonised dispensation. There is a call for a decolonised mind, education, religion, culture, language, and so on, and in South Africa since 2015 students have been marching for a 'free and decolonised education'. And, of course, this is not new for BC. In as much as BC advocates immersed themselves in the politics of the continent and beyond, younger advocates should lead the struggle for a decolonised and free education. BC as a philosophy should occupy the hearts and minds of the South African population, especially youths who are in position of leadership, power and influence. It is said that Biko was not in favour of forming a political party, but yielded for a democrat that he was (Sono 1993:81). We, therefore, do not require AZAPO to enter the fray as a custodian of the philosophy. We do not even need the Socialist Party of Azania (SOPA), which claims to be a more authentic and legitimate portal for the ideals of BC in general and Biko in particular. This is a philosophy that should not be monopolised by a single organisation, because its principles belong to all formations that are bent on liberating South Africa's people. This philosophy is an aspect of a movement that should be allowed to flow freely among the South African population and nourish its democratic society. Many leaders in politics, business, religion, and so on, acknowledge their BC heritage in shaping them into what they have become (Moore 1996:14-24; Sono 1993:109-115).

New national identity

Prior to 1994, South Africa was a country with two nationalities: one black and the other white. The policy of apartheid meant that we became a pariah state among the nations of the world. But since 1994, with the dawn of democracy, we have become a respected country in the world. We are one nation under one flag and singing one national anthem - an anthem that is, of course, still problematic for some South Africans, but that exemplifies the extent to which President Mandela was prepared to go to reconcile a divided nation. A new constitution has been adopted and a new identity has been forged, hence the talk about South Africa as a 'rainbow nation'. But the process of nation building is work in process and the majority of South Africans would like to see the democratic project succeed. Sono (1993) believes that Biko would not have shunned the negotiations that brought about the demise of apartheid in the early 1990s, for Biko (1978d) said:

At some point South Africa itself will begin to want to bargain in a realistic fashion other than through Bantustans … We want to continue mounting criticism and pressure as a people on South Africa, so that when a period of negotiations, which is inevitable in terms of our looking at history, comes, we are there to be talked to. (p. 106)

And he firmly believed that Biko would have been the strongest glue to bind together the fractious factions going under the appellation of liberation movements (1993:101). Whether Biko would have agreed to the so-called 'sunset clauses' is a matter of conjecture, a debate that should be left to his inner circle. South Africa under President Mbeki played a pivotal role on the continent with his African Renaissance project (Makgoba 1999) and BC philosophy has all the hallmarks of this pan-Africanism. According to Maloka (2002):

Pan Africanism rested on four pillars: (a) a sense of common historical experience, (b) a sense of common descent and destiny, (c) opposition to racial discrimination and colonialism, and (d) a determination to create a new Africa. (p. 4)

Who are we as South Africans on the continent? The legacy of our former African leaders, which BC leaders embraced, and on which President Mbeki latched to when he revived the African Renaissance project, must be taught to our African youth. Africa should find solutions for its problems and not look to other countries for assistance. The African Union (AU) became increasingly stronger over the years and today there are examples that prove that it can do things for itself, especially in the areas of conflict resolution and governance. Xenophobia must be tackled head on as it divides Africans on the continent at a time when Africans need each other to make Africa the prosperous and peaceful continent that it has the potential to be. We should relax colonial boundaries. We should stop referring to each other as Francophone, Lusophone and Anglophone countries when the AU addresses continental politics and business. South Africa is fostering a new identity and so should the AU; in fact, I believe much has been done since 2002 when the OAU was transformed into the AU. There is even an AU anthem to show for it.

Black Consciousness as the salt of the earth

As stated above, the philosophy of BC as initially conceptualised was not supposed to have been encapsulated in an institution or single organisation. It was meant to be a people's philosophy for liberation. To this end, young people were targeted to raise the awareness required to fight against apartheid and all that it stood for. There was one common enemy which all the oppressed people, regardless of ideology or political party affiliation, had to oppose and combat. As stated above, white liberals were welcomed to join the struggle, although their mission was confined to converting their fellow white compatriots to the cause of justice. Let me hasten to add that an armed struggle was never an option for BC leaders, although informally, leaders debated the merits and demerits of an armed struggle (Mokoape & Mtinso 1991:138-139). Sono (1993:106) is emphatic that for Biko, violence against the apartheid regime was not an option. He would negotiate and bargain, even if it took decades. This should explain why the 1976 march against Bantu Education, Afrikaans as medium of instruction and the whole apartheid edifice by the Soweto school children was peaceful. The violence that ensued was unleashed by the police and other 'law and order' agencies. A number of workshops would be conducted by university students and theology seminarians during school holidays across the country. University students who were expelled because of their political activism were employed as teachers at high schools and they used the opportunity to teach BC. After 1994, we have 'monopoly capital' as the common enemy. Capitalism chases after profit on the backs of the poor and the working class. As capitalists extend their profit margins, poor people are increasingly being marginalised and hindered from enjoying the fruits of their labour. The courage and bravery that characterised the militant youth of the mid-1960s and later should be infused into the youth of today because the fight against poverty is just as important as the struggle against apartheid. The success of the industrial strikes of 1970s, especially in Natal, is a case in point. Workers refused to sell their labour for slave wages. The Marikana mine strikes which unfortunately resulted in the deaths of scores of miners demonstrated to the world the extent to which they were prepared to go to fight for their rights and dignity as human beings; and much more could be achieved if the workers' unions could transcend their own political and ideological affiliations. BC's transcendence over political parties should be able to unite all South Africans against 'white monopoly capital'. It should be sprinkled like salt on the South African population so that a concerted effort should be directed at the socio-economic emancipation of the poor, most of whom are black people. It must be acknowledged that Sono (1993) disagrees that BC, in its present composition, would have a role to play in the democratic South Africa:

Were the BCM revolutionaries to guarantee the delivery of the political needs of today, they would most likely be competitive. But to do so the BCM will have to change its modalities and perspectives dramatically. To that extent then it would have ceased being a BC formation. (p. 131)

Self-reliance

'There is a lot of community work that needs to be done in promoting a spirit of self-reliance and black consciousness among all black people in South Africa' (Biko 1978c:38). Leaders of BC knew very well that national liberation would not automatically translate into prosperity for all. As indicated above, people were encouraged and assisted to do things for themselves instead of waiting upon benefactors for charity and donations. Bursaries and scholarships were organised for deserving poor pupils and students, especially for those whose parents were detained for political reasons. The poor, especially those who had been detained and later released, were given seed funding to start all sorts of small-scale businesses in agriculture and industries, for example, and some jobs were created along the way. Charity perpetuates poverty and strips people of their dignity (Ramphele 1991:154-178). The government cannot fight poverty by dishing out welfare grants at will. Those who are elderly, sickly or disabled should, by all means, benefit from welfare grant schemes. But some grants are more questionable, such as those given to pregnant school girls and free housing. How about giving the poor building materials and let them build the houses themselves? BC's approach to fighting poverty should come in handy here. The one sure way to get the poor out of the cycle of poverty is to create jobs. The culture of entitlement and corruption is stunting the growth of South Africa's economy. When people get things free, they lose the sense of ownership of the things they have and, as a result, they do not become stewards of the assets of the country. Some black people do not appreciate that since 1994 they have owned all societal and state assets. No wonder when communities demand a tarred road, they burn a clinic, and when they demand water, they burn a school or clinic. When they demand 'free and decolonised education', they burn a library or a laboratory. We can only acquire more assets if we preserve existing ones. We need a development trajectory that will encapsulate Ramphele's (1991) idea that:

(development) as a process of empowerment … enables participants to assume greater control over their lives as individuals and members of societies. It is a process of capacity building and empowerment of people working for a preferred and shared future. (p. 157)

Research, knowledge production and education

Everybody agrees that education is vital for the liberation of the mind and body. BC as a philosophy that was invented by young people was steeped in an understanding of the value of education. Conscientisation workshops held during school holidays were aimed at empowering young people to know their history and their purpose in life as well as shaping their own destiny. 'Conscientization was … fundamental to Black Consciousness programmes. Through cultural activities such as drama, music, youth activities, Black Consciousness was taught' (Sono 1993:72). The leaders themselves were educated people and were intellectuals in their own right. Decolonised curricula should be crafted that could be offered from primary school to tertiary level. There should be a policy on free compulsory education so that no single child or student might be excluded on financial grounds. In order for such curricula to be crafted, Africans should write the study material themselves and discard those written about them by others. BC had already realised this truth in the 1970s, when journals such as Black Review and Black Viewpoint were launched (Ramphele 1991:162). After the decolonisation process in Africa began, people delved into their histories to prove that African religion, philosophy and culture, in general, were far superior to any civilisation in the world. Features that we today marvel in terms of science, mathematics, education, governance, technology, and so on, were shown to have been started by Africans (cf. Makgoba 1999).

Significance for theological education

Black Theology (BT) was conceptualised almost simultaneously with BC for some of the BC leaders were the same as BT leaders. People such as Biko, Pityana, Motlhabi, Mosala, Maimela and Khoapa fall into this category. Biko, for example, did not renounce his membership of UCM and he, in fact, drove the BT project with the assistance of some theology students (Sono 1993:29). BC and BT shared the same ideological basis to such an extent that conclusions such as the following were drawn: 'Black Theology … is an extension of Black Consciousness' (Pityana 1972:41), 'Black Theology is the theological aspect of Black Consciousness' (Motlhabi 1972:55) and '(Some) ordinands and lay people were deeply influenced by Black Consciousness and its soulmate, Black Theology' (Duncan 2008:116). Within the SASO leadership, responsibilities were shared and Biko and Pityana were given the responsibility for political and theological matters (Wilson 1991:29). How was BT understood? For Biko (1978f):

Black Theology … is a situational interpretation of Christianity. It seeks to relate the present-day black man to God within the given context of the black man's suffering and his attempts to get out of it … (it is) committed to eradicating all causes of suffering as represented in the death of children from starvation, outbreaks of epidemics in poor areas, or the existence of thuggery and vandalism in townships. (p. 59)

Biko (1978j) continues:

(BT) seeks to relate God and Christ once more to the black man and his daily problems. It wants to describe Christ as a fighting God, not as a passive God who allows a lie to rest unchallenged. It grapples with existential problems and does not claim to be a theology of absolutes. It seeks to bring back God to the black man and to the truth and reality of his situation. (p. 94)

Motlhabi (1972), one of the foremost exponents of BT, has the following to say regarding the nature of BT:

Black Theology is not a new theology nor is it a proclamation of a new gospel. It is merely a re-evaluation of the gospel message, a making relevant of this message according to the situation of the people … Its advocates believe that Christ not only has something to do and offer my 'soul' but to 'me' in my entire situation and condition here and now … Its true meaning is co-extensive with suffering, of the majority in this country is 'not white', 'Black' is rightly used, affirming that whiteness is not the only value in relation to which everything else should be considered. (pp. 56-57)

Black Theology is therefore situational and not time-bound as some might think. It will continue to address new questions and confront new challenges as they arise.

As we know, the colonialists and traders were in cahoots with the missionaries. As colonialists denigrated African culture and civilisation as savage and barbaric, missionaries demonised African religion as heathen and pagan. Therefore, the theology that was taught in theological seminaries was a theology that was 'white' and was emptied of all Africanity. Biko, Ramphele, Sabelo and others visited theological seminaries throughout the country to influence the students as well as staff to revise their curriculum. It was supposed to be a curriculum that would address the existential needs and aspirations of black people (Duncan 2008:115-140; Motlhabi 2008:3-7; Stubbs 1978:158). Under the leadership of Pityana, for example, BT at Fort Hare University flourished and the curriculum there, placed a heavy emphasis on practical theology, community outreach and engagement (Duncan 2008:133). As a result, many seminaries and universities, especially historically black universities as well as the University of South Africa, included in their course material Latin American Liberation Theology, US Black Theology and South African Theology. That enthusiasm has seemed to be receding since 1994 unfortunately. Some theologians, even black ones, have substituted the term BT with terms such as 'Theology of Reconstruction' and 'Public Theology'. Indeed, we are faced today with issues of nation building and reconciliation. How are we to teach the relationship of such concepts to restorative justice, for example? Seminaries and universities should Africanise theological education in such a way that those who graduate from such entities are fully equipped to deal with the socio-economic realities in South Africa today. Capitalism and neo-liberal concepts should be taught at our theological institutions. Globalisation and its drivers, the multinationals, World Bank and WTO should be integrated into theological education so that the graduateness of theologians should be made manifest in their pastoral ministry and research. For example, if ecology was taught from an African perspective, where conservation and preservation are prominent, and not from the Western perspective, where profit is of paramount importance, the dangers and consequences of climate change would not even arise. Tenets of African religion and culture should be resuscitated when teaching theology as values and principles can be learned to save our finite planet. In as much as it is good to learn from classical white scholars, we must include a high dosage of classical African scholars, who are accessible in abundance. The primacy and centrality of the Bible is obviously crucial as that is what makes us Christians, while the research done by Oden (2007) is helpful in understanding African Christianity and Western Christianity.

I am convinced that the abiding relevance of BC cannot be doubted. What perhaps needs to be looked into are the strategies for fighting present-day challenges, especially on the socio-economic front. For instance, the scepticism that was directed at white liberals since the 1960s should now be directed at 'monopoly capital', irrespective of whether it refers to black or white businesses. And, of course, globally, we should reassess our relationship with the multinational corporations as well as institutions such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and World Trade Organization. Racism was not vanquished with the advent of democracy and we must add classism to the list of social ills as well as xenophobia. Obviously, these are areas that need more research. At the height of apartheid people fought side by side regardless of their party political affiliation, class, religion or gender. The formation of the UDF is a case in point. We pushed and pushed until the walls of apartheid fell like the walls of Jericho in the Bible. As stated above, Biko wished for BC to become a philosophy for all South Africans, because it transcended party politics and ideologies. Perhaps, Biko would find it appropriate that we do not have a single BC political party in parliament, because this means that individuals, regardless of party affiliation, can apply their BC philosophy to influence legislation that will lead to 'radical transformation' of the economy of the country. We need to become one nation, black and white under one flag to work for the good of the nation without trying to score cheap political points at the expense of other political parties. Of course, as a democracy, we need to have honest and robust debates as we form and shape the kind of a society in which all citizens, as well as foreign nationals, will be happy and safe to live. Theology, in general, and BT, in particular, should work hand in hand with civil society and movements that are in the struggle to eradicate the fundamental problem of poverty in society.

Acknowledgements

Competing interests

The author declares that he or she has no financial or personal relationships which may have inappropriately influenced him or her in writing this article.

Abraham, K., 2003, Politics of black nationalism: From Harlem to Soweto , Africa World Press, Inc., NJ. [ Links ]

Biko, S., 1978a, 'Black consciousness and the quest for true humanity', in A. Stubbs (ed.), I write what I like , pp. 87-98, The Bowerdean Press, London. [ Links ]

Biko, S., 1978b, 'Black souls in white skins', in A. Stubbs (ed.), I write what I like , pp. 19-26, The Bowerdean Press, London. [ Links ]

Biko, S., 1978c, 'Fear: An important determinant in South Africa', in A. Stubbs (ed.), I write what I like , pp. 73-79, The Bowerdean Press, London. [ Links ]

Biko, S., 1978d, 'Fragmentation of the black resistance', in A. Stubbs (ed.), I write what I like , pp. 33-39, The Bowerdean Press, London. [ Links ]

Biko, S., 1978e, 'Let's talk about Bantustans', in A. Stubbs (ed.), I write what I like , pp. 80-86, The Bowerdean Press, London. [ Links ]

Biko, S., 1978f, 'SASO - Its role, its significance and its future', in A. Stubbs (ed.), I write what I like , pp. 3-7, The Bowerdean Press, London. [ Links ]

Biko, S., 1978g, 'Some African cultural concepts', in A. Stubbs (ed.), I write what I like , pp. 40-47, The Bowerdean Press, London. [ Links ]

Biko, S., 1978h, 'The church as seen by a young layman', in A. Stubbs (ed.), I write what I like , pp. 54-60, The Bowerdean Press, London. [ Links ]

Biko, S., 1978i, 'The definition of black consciousness', in A. Stubbs (ed.), I write what I like , pp. 48-53, The Bowerdean Press, London. [ Links ]

Biko, S., 1978j, 'White racism and black consciousness', in A. Stubbs (ed.), I write what I like , pp. 61-72, The Bowerdean Press, London. [ Links ]

Brotz, H., 1977, The politics of South Africa , Oxford University Press, London. [ Links ]

Buthelezi, S., 1991, 'The emergence of black consciousness', in B. Pityana & M. Ramphele (eds.), Bounds of possibility: The legacy of Steve Biko and black consciousness , pp. 111-129, David Philip, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Changuion, L. & Steenkamp, B., 2012, Disputed land: The historical development of the South African land issue , Protea Book House, Pretoria, pp. 1652-2011. [ Links ]

Davenport, T.R.H., 1987, South Africa: A modern history , Macmillan Press, London. [ Links ]

Duncan, G., 2008, Steve Biko's religious consciousness and thought and its influence on theological influence with special reference to the federal theological seminary of Southern Africa , UNISA, Pretoria, pp. 115-140. [ Links ]

Halisi, C.R.D., 1991, 'Biko and black consciousness philosophy', in N.B. Pityana & M. Ramphele (eds.), Bounds of possibility: The legacy of Steve Biko & black consciousness , pp. 100-110, David Philip, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Khoapa, B., 2008, 'African diaspora: Intellectual influences on Steve Biko', in C.V. du Toit (ed.), The legacy of Stephen Bantu Biko , pp. 73-87, Unisa, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Lodge, T., 1983, Black politics in South Africa Since 1945 , Ravan Press, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Makgoba, M.W., 1999, African renaissance , Mafube Publishers Ltd, Sandton. [ Links ]

Maloka, E., 2002, 'Towards the African Renaissance: The African Union and the New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD), in Report on the 9th Conference of Africanists , Moscow. [ Links ]

Marsh, R., 2013, Understanding Africa and the events that shaped its destiny , LAPA Publishers, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Mokoape, K. & Mtinso, T. (eds.), 1991, 'Towards the armed struggle', in N.B. Pityana & M. Ramphele (eds.), Bounds of possibility: The legacy of Steve Biko , pp. 137-142, David Philip, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Moodley, K., 1991, 'The continued impact of black consciousness', in N.B. Pityana & M. Ramphele (eds.), Bounds of possibility: The legacy of Steve Biko & black consciousness , pp. 143-152, David Philip, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Moore, B., 1996, 'Black theology revisited', in K.C. Abraham (ed.), Voices from the third world , vol. xix, no. 2, pp. 7-45, BTESSC, Bangalore, India. [ Links ]

Motlhabi, M., 1972, 'Black theology', in M. Motlhabi (ed.), A personal opinion , pp. 53-59, University Christian Movement, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Motlhabi, M., 2008, African theology/black theology in South Africa: Looking back, moving on , UNISA, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Motsoko, P., 1984, Apartheid: The story of a dispossessed people , Marriam Books, London. [ Links ]

Mzimela, S.E., 1983, Apartheid: South African Naziism , Vantage Press Inc., New York. [ Links ]

Oden, T.C., 2007, How Africa shaped the Christian mind , Intervarsity Press, Downers Grove, IL. [ Links ]

Odendaal, A., 2012, The founders: The origins of the ANC and the struggle for democracy in South Africa , Jacana Media, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Pityana, B., 2008, 'Reflections on 30 years since the death of Steve Biko: A legacy revisited', in C.W. du Toit (ed.), The legacy of Stephen Bantu Biko , pp. 1-14, UNISA, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Pityana, N.B., 1972, 'What is black consciousness?', in M. Motlhabi (ed.), Essays on black theology , pp. 37-43, University Christian Movement, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Ramphele, M., 1991, 'Empowerment and symbols of hope', in N.B. Pityana & M. Ramphele (eds.), Bounds of possibility: The legacy of Steve Biko , pp. 154-178, David Philip, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Seleoane, M., 2008, 'The development of black consciousness as a cultural and political movement (1967-2007)', in C.W. du Toit (ed.), The legacy of Stephen Bantu Biko , pp. 15-56, UNISA, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Sibisi, C.D.T., 1991, 'The psychology of liberation', in N.B. Pityana & M. Ramphele (eds.), Bounds of possibility: The legacy of Steve Biko and black consciousness , pp. 130-136, David Philip, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Sono, T., 1993, Reflections on the origins of black consciousness in South Africa , HSRC, Pretoria. [ Links ]

Stubbs, A., 1978, 'Martyr of hope', in A. Stubbs (ed.), I write what I like , pp. 154-216, The Bowerdean Press, London. [ Links ]

Suttner, R., 2008, ANC underground in South Africa to 1976 , Jacana Media, Johannesburg. [ Links ]

Wilson, L., 1991, 'Bantu Stephen Biko: A life', in N.B. Pityana & M. Ramphele (eds.), Bounds of possibility: The legacy of Steve Biko & black consciousness , pp. 15-77, David Philip, Cape Town. [ Links ]

Received: 05 Apr. 2017 Accepted: 22 June 2017 Published: 04 Dec. 2017

History Paper 2 Memorandum - Grade 12 June 2021 Exemplars

SECTION A: SOURCE-BASED QUESTIONS QUESTION 1: HOW DID SOUTH AFRICANS REACT TO P.W. BOTHA’S REFORMS IN THE 1980s? 1.1 1.1.1 [Extraction of information from Source 1A – L1]

- It granted rights to African trade unions

- Allowed privileges for the urban African workforce

- Create a black middle class (Any 2 x 1) (2)

1.1.2 [Interpretation of evidence from Source 1A – L2]

- The government hoped that there would be fewer uprisings in the townships

- The house owners would not tolerate the uprisings as it might damage their houses/property

- Any other relevant response (Any 1 x 2) (2)

1.1.3 [Extraction of information from Source 1A – L1]

- Advertising campaigns

- New loans were made available (2 x 1) (2)

1.2 1.2.1 [Interpretation of evidence of from Source 1B – L2]

- The apartheid government used harsher methods to oppress uprisings

- Many of the political leaders were in jail or in exile

- Any other relevant response (2 x 2) (4)

1.2.2 [Extraction of information from Source 1B – L1]

- Reverend Allan Boesak

- Albertina Sisulu

- Patrick ‘Terror” Lekota (Any 2 x 1) (2)

1.2.3 [Extraction of information from Source 1B – L1]

- Freedom from the apartheid regime (1 x 2) (2)

1.2.4 [Interpretation of evidence of from Source 1B – L2]

- They had the same goal and that was to end apartheid

- As the ANC was banned, it called on the UDF to increase internal pressure on the government

- Any other relevant response (2 x 2) (4)

1.2.5 [Evaluating the usefulness of Source 1B – L3] The source is useful because:

- It coordinated the anti-apartheid groups so that effective protests could be launched

- The UDF brought together many different anti-apartheid organisations across the country

- As it was a loose alliance, the government could not easily destroy it

- The UDF made the country ungovernable through various campaigns

- Any other relevant response (Any 2 x 2) (4)

1.3 1.3.1 [Interpretation of evidence from Source 1C – L2]

- To discourage Coloured and Indians from participating in the elections for the Tri-cameral parliament

- The reforms were seen as cosmetic and the political power would still remain in the hands of the white minority

- The fact that black South Africans were left out of the new parliamentary system

1.3.2 [Extraction of information from Source 1C – L1]

- ‘Don’t Vote’ campaign (1 x 2) (2)

1.3.3 [Interpretation of evidence from Source 1C – L2]

- To make people aware of the need to organise and actively resist apartheid

- To mobilise South Africans to fight against discrimination and oppression

- Any other relevant response (2 x 2) (4)

1.4 [Comparison of Source 1B and Source 1C – L3]

- Source 1B indicates that the UDF became a mass-based organisation and Source 1C shows the many people/organisations that were affiliated to the UDF

- Source 1B refers to resistance campaigns launched by the UDF and Source 1C show the ‘Don’t Vote’ campaign

- Source 1B indicates that the goal was to get freedom from the apartheid regime and Source 1C shows them fighting for freedom

1.5 1.5.1 [Explanation of historical concept from Source 1D – L1]

- The power of the ordinary people to bring change

- To insist on a government that represents their interests

- Any other relevant response (Any 1 x 2) (2)

1.5.2 [Extraction of information from Source 1D – L1]

- Rent boycotts

- Consumer boycotts (2 x 1) (2)

1.5.3 [Interpretation of evidence from Source 1D – L2]

- The rent money was not used to improve the conditions/facilities in their communities

- The black councillors who collected the rent became corrupt and were seen as ‘sell-outs’

1.6 [Interpretation, evaluation and synthesis of evidence from relevant sources- L3] Candidates could include the following aspects in their response:

- Black South Africans saw Botha’s reforms as cosmetic (own knowledge)

- Tri-cameral parliament was rejected by black South Africans (own knowledge)

- UDF formed to oppose apartheid (Source 1B)

- UDF coordinated the actions against apartheid (Source 1B)

- Protests, rent and consumer boycotts held (Source 1B and Source 1D)

- Different organisations affiliated to the UDF (Source 1B)

- UDF held anti-elections campaigns (Source 1C)

- People demanded freedom (Source 1C)

- Civic organisations fought for better conditions in townships (Source 1D)

- Workers, student organisations and churches joined the protest actions against apartheid (own knowledge)

- Any other relevant response

Use the following rubric to allocate marks:

(8) [50]

QUESTION 2: HOW SUCCESSFUL WAS THE TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION (TRC) IN DEALING WITH THE DEATH OF ACTIVIST LENNY NAIDU? 2.1 2.1.1 [Extraction of information from Source 2A – L1]

- Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) (1 x 2) (2)

2.1.2 [Extraction of information from Source 2A – L1]

- Advancing the ideas of non-racialism and unity

- Fighting for freedom

- Striving to improve the quality of life of all people (3 x 1) (3)

2.1.3 [Interpretation of evidence from Source 2A – L2]

- If caught he would be jailed or killed by the apartheid system

- He openly rebelled against apartheid and was thus perceived as a threat

- Could not operate freely to dismantle apartheid

- Determined to fight against the unjust apartheid system

- Any other relevant response (Any 2 x 2) (4)

2.1.4 [Interpretation of evidence from Source 2A – L2]

- He was waiting to execute the instructions or orders from the ANC in South Africa

- Which government institutions he had to attack/destroy

- Any other relevant response (Any 1 x 2) (2)

2.2 2.2.1 [Extraction of evidence from Source 2B – L1]

- He would have been charged for being a member of the ANC

- Charged without a passport (Any 2 x 1) (2)

2.2.2 [Extraction of evidence from Source2B – L1]

- Eugene De Kock

- Mr Nafumela (2 x 1) (2)

2.2.3 [Interpretation of evidence of from Source 2B – L2] NO.

- The commissioner told them to wait for full disclosure at the amnesty hearing

- They will find a lead of what happened at the hearing

2.2.4 [Extraction of evidence from Source 2B – L1]

- Murder (1 x 2) (2)

2.2.5 [Evaluating the reliability of Source 2B – L3] The source is reliable because:

- The parents and brother were convinced that Lenny was murdered

- Both de Kock and Nafumela are guilty because they applied for amnesty

- They were able to speak their hearts out and get some kind of closure

OR The source is not reliable because:

- It did not give full disclosure because the commissioner told them they still have to wait for the amnesty hearing

- Both of them still believed that they were innocent by applying for amnesty

- Any relevant response (Any 2 x 2) (4)

2.3 2.3.1 [Extraction of evidence from Source 2C – L1]

- ‘How two sets of Umkhonto we Sizwe cadres were ambushed at Piet Retief’ (1 x 2) (2)

2.3.2 [Interpretation of evidence from Source 2C – L2]

- Swaziland supported the ANC’s fight against the apartheid regime

- Swaziland did not favour white minority rule in South Africa

- Swaziland wanted a free, democratic and liberated South Africa

- Swaziland was one of the closest independent African countries and therefore ANC cadres were able to gain access for onward travel to MK training camps, for example in Lusaka (Zambia)

2.3.3 [Extraction of evidence from Source 2C – L2]

- Charity Nyembezi

- Makhosi Nyoka

- Nonsikelelo Cothoza (3 x 1) (3)

2.4 2.4.1 [Interpretation of evidence from Source 2D – L2]

- The cartoon shows Eugene de Kock submitting his application for amnesty to the TRC

- It depicts Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the chairperson of the TRC receiving De Kock’s application

- The cartoon shows a very long list of crimes that were committed by De Kock

2.4.2 [Interpretation of evidence from Source 2D – L2]

- Tutu wanted De Kock to list all the crimes that he had committed before he could apply for amnesty

- De Kock had committed a number of human rights crimes against anti-apartheid activists

- De Kock was famous as a killer of anti-apartheid activist

2.5 [Comparison of Source 2C and Source 2D – L3]

- Source 2C explains De Kock’s application for amnesty and Source 2D shows De Kock submitting his application for amnesty

- Source 2C reveals many crimes that De Kock had committed and Source 2D shows De Kock with a long list of crimes that he has committed

2.6 [Interpretation, evaluation and synthesis of evidence from relevant sources – L3] Candidates could include the following aspects in their response:

- Lenny Naidu was a member of the ANC’s armed wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (Source 2A)

- Both parents and brother of Lenny Naidu attended the TRC hearing to seek the truth about the murder (Source 2B)

- The commissioner thanked them for coming forward and making a disclosure (Source 2B)

- The TRC revealed the truth about human rights abuses committed from 1960 to 1994 (Source 2C)

- Leslie Naidu appeared before the TRC to give evidence regarding the murder of Lenny Naidu (Source 2B)

- Eugene De Kock and other former security policemen testified about their role regarding the killings of political activists at Piet Retief (Source 2C)

- The truth of how Lenny Naidu was murdered was revealed to the TRC (Source 2C)

- Eugene De Kock submitted the list of crimes he committed to the TRC (Source 2D)

- De Kock applied for amnesty for the murder of Lenny Naidu (Source 2C)

- The TRC was able to solve some murders and disappearances of political activists such as that of Lenny Naidu (own knowledge)

(8) [50]

SECTION B: ESSAY QUESTIONS QUESTION 3: CIVIL RESISTANCE, 1970s TO 1980s: SOUTH AFRICA [Plan and construct an original argument based on relevant evidence using analytical and interpretative skills.] SYNOPSIS Candidates should critically discuss the role and impact of the Black Consciousness Movement under Steve Biko on black South Africans in the 1970s. MAIN ASPECTS Candidates should include the following aspects in their response:

- Introduction: Candidates need to take a stance and discuss the role and impact of the Black Consciousness Movement under Steve Biko on black South Africans in the 1970s.

ELABORATION

- Reason for the formation of the Black Consciousness Movement (Background)

Biko’s philosophy of Black Consciousness (BC)

- Conscientised black people of the evils of apartheid

- Instilled a sense of self-worth and confidence in black South Africans

- Restored black pride

- Changed the way black South Africans saw themselves

- Empowered them to confront apartheid

- Biko urged black South Africans to assert themselves and to do things for themselves

- Eliminated the feeling of inferiority

Role of Steve Biko

- Formation of SASO

- SASO spread BC ideas across the campuses of the ethnically separated universities

- SASO promoted black unity and solidarity

- Made students more politically aware

- Encouraging students to liberate themselves from apartheid

- Biko promoted self-liberation

- He believed that association with whites made the liberation struggle ineffective and that blacks must liberate themselves

- Established self-help groups for black communities with other BC leaders

- BC ideas were published in SASO newsletters

Black Consciousness became a national movement

- In 1972 the Black People’s Convention was formed

- Aimed to liberate black people from both psychological and physical oppression

- Self-help projects were set up e.g. Zanempilo Clinic, Ginsburg, and Zimele Trust Fund

- Led to the formation of the Black Allied Workers Union in 1973

- BC influenced scholars that led to the formation of SASM

Challenges posed by the ideas of BC to the state

- At first the South African government was not concerned about the BCM and assumed it to be in line with its own policy of separate development

- BCM became stronger and posed a challenge to the state

- It became a mass movement that sought to undermine apartheid

- Biko’s speeches encouraged black South Africans to reject apartheid

- BC ideas incited the workers to embark on strike action

- BCM supported disinvestment companies

Government’s reaction to Biko’s philosophy

- Banning and house arrest of Biko and other leaders

- BC leaders were banned from speaking in public

- BPC activists were detained without trail

- SASO was banned on university campuses

- Biko was arrested and interrogated

- Biko was brutally murdered by the security police in 1977

Conclusion: Candidates need to tie up their argument with a relevant conclusion. [50]

QUESTION 4: THE COMING OF DEMOCRACY TO SOUTH AFRICA AND COMING TO TERMS WITH THE PAST [Plan and construct an original argument based on relevant evidence using analytical and interpretative skills] SYNOPSIS Candidates need to agree or disagree with the statement by discussing the commitment and leadership displayed by both Mandela and De Klerk that ensured South Africa’s democracy. Relevant examples to South Africa’s road to democracy must be discussed. MAIN ASPECTS Candidates should include the following aspects in their essays:

- Introduction: Candidates need to discuss the commitment and leadership role played by Mandela and De Klerk in creating conditions for South Africa’s road to democracy from 1990 to 1994.

ELABORATION Focus on different role players in the following key historical events and turning points:

- Release of Mandela and unbanning of ANC, PAC and SACP

- The process of negotiations (i.e. Groote Schuur Minute, Pretoria Minute)

- Suspension of the armed struggle

- Record of Understanding

- Increased violence – Rolling mass action (i.e. Boipatong, Bhisho, etc.)

- Goldstone Commission

- Multi party negotiations

- Death of Hani

- Storming of the World Trade Centre, etc.

- 1994 election – cast ballot in KZN

- ANC won elections and Mandela became the first black South African President

QUESTION 5: THE END OF THE COLD WAR AND A NEW WORLD ORDER: THE EVENTS OF 1989 [Plan and construct an original argument based on relevant evidence using analytical and interpretative skills] SYNOPSIS They need to indicate to what extent the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1989 served as a catalyst for South Africa to begin its political transformation in the 1990s. Candidates must support their given line of argument with relevant historical evidence. MAIN ASPECTS Candidates should include the following aspects in their response:

- Introduction: Candidates need to indicate the extent of the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1989 served as a catalyst for the political transformation that occurred in South Africa in the 1990s.

ELABORATION In agreeing, candidates could include the following points in their answer:

- The impact of the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1989 on South Africa

- Gorbachev’s reform policies of Glasnost and Perestroika

- The communist regimes in Eastern Europe collapsed

- The Berlin Wall had fallen

- Changes in the world contributed to the end of apartheid

- The collapse of the USSR deprived the ANC of its main source of support (financial; military and moral and its consequences)

- The National Party claim that it was protecting South Africa from a communist onslaught became unrealistic

- Western world powers supported the move that South Africa resolve its problems peacefully and democratically

- It became evident the National Party government could not maintain white supremacy indefinitely

- Influential National Party members started to realise that apartheid was not the answer to the needs of white capitalist development

- The Battle of Cuito Cuanavale and its consequences

- The security forces and state of emergency had not stopped township revolts

- By the late 1980s South Africa was in a state of economic depression

- The role of business leaders in South Africa’s political transformation

- PW Botha suffered a stroke and was succeeded by FW de Klerk

- FW De Klerk started to accept that the black South African struggle against apartheid was not a conspiracy directed from Moscow

- This enabled De Klerk to engage in discussions with the liberation organisations

- On 2 February 1990, De Klerk announced ‘a new and just constitutional dispensation’

- This signalled the end of apartheid

Related items

- Mathematics Grade 12 Investigation 2023 Term 1

- HISTORY PAPER 2 GRADE 12 ADDENDUM - NSC PAST PAPERS AND MEMOS JUNE 2022

- TECHNICAL SCIENCES PAPER 2 GRADE 12 QUESTIONS - NSC PAST PAPERS AND MEMOS JUNE 2022

- TECHNICAL SCIENCES PAPER 1 GRADE 12 QUESTIONS - NSC PAST PAPERS AND MEMOS JUNE 2022

- MATHEMATICS LITERACY PAPER 2 GRADE 12 MEMORANDUM - NSC PAST PAPERS AND MEMOS JUNE 2022

- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

Conclusion: Black Consciousness Movement

It can be concluded that the death of Biko left a vacuum similar to the one created by the banning of the ANC and the PAC after Sharpeville. On the positive side, many youths had reached a level of consciousness about the plight of Blacks in apartheid South Africa that could not be ignored. Contrary to expectation in White circles that the death of Biko would signal the end of resistance, the struggle instead escalated as political activism increased.

The role played by Biko and his colleagues in the BCM, as well as in the fight for South Africa’s freedom cannot be under-estimated. Steve Biko’s life reflected the aspirations of many frustrated young Black intellectuals. Therefore, when he died, he became a martyr and symbol of Black Nationalism, and his struggle focused critical world attention on South Africa more than ever before.

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

NSC Internal Moderators Reports 2020 NSC Examination Reports Practical Assessment Tasks (PATs) SBA Exemplars 2021 Gr.12 Examination Guidelines Assessment General Education Certificate (GEC) Diagnostic Tests

Black Consciousness Movement Grade 12 Essay Guide (Question and Answers) and Summary: The Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) was a grassroots anti-Apartheid activist movement that emerged in South Africa in the mid-1960s out of the political vacuum created by the jailing and banning of the African National Congress and Pan Africanist Congress leadership after the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960.

This is why we try to communicate with our people through community projects rather than inviting them to a political discussion, which they would often be afraid to attend.

tor ture remain unknown, Biko's death has been underst ood by many South Africans as an assassination. Black consciousness was be yond a movement; it was a philosophy deeply gr ounded in

On 12 September 1977, the Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko died while in the custody of security police. The period leading up to his death, beginning with the June 1976 unrest, had seen some of the most turbulent events in South African history, the first signs that the apartheid regime would not be able to maintain its oppressive rule ...

Download full-text PDF Read full-text. Download full-text PDF. ... (BCM) in South . ... In his essays of the late 1950's and early .

The Rise of Black Consciousness. The Black Consciousness movement became one of the most influential anti-apartheid movements of the 1970s in South Africa. While many parts of the African continent gained independence, the apartheid state increased its repression of black liberation movements in the 1960s. In the latter part of the decade, the ...

Many anti-apartheid leaders and supporters were in jail or had gone into exile. However, in the 1970s, a new movement called Black Consciousness or BC led to renewed resistance. The movement was led by a man called Steve Biko. BC encouraged all black South Africans to recognize their inherent dignity and self-worth.

Download full-text PDF Read full ... Pityana, N.B., 1972, 'What is black consciousness?', in M. Motlhabi (ed.), Essays on . black ... The BCM emerged during the period following the political ...

ii However, the study did show the close relationship between individual and social well-being that emerged as intrinsic both to the philosophy of BC and the lives of these individuals.

The BCM can be said to have prepared the way for the bolder moves of the 1970s and 1980s, which culminated in the events of the 1990s. The impact of BCM goes beyond particular organizations. (p. 129) Ideological underpinnings. Biko qualified from the outset what BC means by 'blackness'.

The BCM urged a defiant rejection of apartheid, especially among Black workers and the youth. The South African Students Organisation (SASO) - an arm of the movement - was founded by Black students who refused to join NUSAS, another student led organisation. In the following year, boycotts and unrest among students and teachers grew after Steve

The philosophy and aims of Black Consciousness (BC) BC started as an attitude of mind rather than a political movement. It defined as 'black' all those oppressed by Apartheid. BC aimed to raise black confidence to bring about liberation. Promote pride in black identity, culture and history. Challenged white 'liberals'.

This guides the philosophy underlying the teaching and assessment of the subject in Grade 12. The purpose of these Examination Guidelines is to: Provide clarity on the depth and scope of the content to be assessed in the Grade 12 National Senior Certificate Examination in History. Assist teachers to adequately prepare learners for the examinations.

QUESTION 4: CIVIL RESISTANCE, 1970s TO 1980s: SOUTH AFRICA BCM UNIVERSAL ESSAY 2023. The Black Consciousness Movement successfully used its aims and ideas of self-reliance to challenging the apartheid system in South Africa in the 1970s.

BCM and related decolonial approaches highlight the importance of sharing interpretations and stories that counteract these negative representations, often through dialogue and creative practice. Intervention designers need to think carefully about how such dialogue and creativity can be facilitated and supported.

History Essay. The Black Consciousness movements aimed to help black people in South Africa become proud of their own identity. The BCM was formed because many of the countries ANC leaders at the time were either in exile or in prison. The fight against apartheid had slowed down after the banning of the ANC.

The BCM urged a defiant rejection of apartheid, especially among Black workers and the youth. The South African Students Organisation (SASO) - an arm of the movement - was founded by Black students who refused to join NUSAS, another student led organization. At the same time, Black workers began to organise trade unions in defiance of anti ...