Cohesion And Coherence In Essay Writing

Table of contents, introduction.

Coherent essays are identified by relevance to the central topic. They communicate a meaningful message to a specific audience and maintain pertinence to the main focus. In a coherent essay, the sentences and ideas flow smoothly and, as a result, the reader can follow the ideas developed without any issues.

To achieve coherence in an essay, writers use lexical and grammatical cohesive devices. Examples of these cohesive devices are repetition, synonymy, antonymy, meronymy, substitutions , and anaphoric or cataphoric relations between sentences. We will discuss these devices in more detail below.

This article will discuss how to write a coherent essay. We will be focusing on the five major points.

- We will start with definitions of coherence and cohesion.

- Then, we will give examples of how a text can achieve cohesion.

- We will see how a text can be cohesive but not coherent.

- The structure of a coherent essay will also be discussed.

- Finally, we will look in detail at ways to improve cohesion and write a coherent essay.

Before illustrating how to write coherent essays, let us start with the definitions of coherence and cohesion and list the ways we can achieve cohesion in a coherent text.

Definitions Cohesion and Coherence

In general, coherence and cohesion refer to how a text is structured so that the elements it is constituted of can stick together and contribute to a meaningful whole. In coherent essays, writers use grammatical and lexical cohesive techniques so that ideas can flow meaningfully and logically.

What is coherence?

Coherence refers to the quality of forming a unified consistent whole. We can describe a text as being coherent if it is semantically meaningful, that is if the ideas flow logically to produce an understandable entity.

If a text is coherent it is logically ordered and connected. It is clear, consistent, and understandable.

Coherence is related to the macro-level features of a text which enable it to have a sense as a whole.

What is cohesion?

Cohesion is commonly defined as the grammatical and lexical connections that tie a text together, contributing to its meaning (i.e. coherence.)

While coherence is related to the macro-level features of a text, cohesion is concerned with its micro-level – the words, the phrases, and the sentences and how they are connected to form a whole.

If the elements of a text are cohesive, they are united and work together or fit well together.

To summarize, coherence refers to how the ideas of the text flow logically and make a text semantically meaningful as a whole. Cohesion is what makes the elements (e.g. the words, phrases, clauses, and sentences) of a text stick together to form a whole.

How to Achieve Cohesion And Coherence In Essay Writing

There are two types of cohesion: lexical and grammatical. Writers connect sentences and ideas in their essays using both lexical and grammatical cohesive devices.

Lexical cohesion

We can achieve cohesion through lexical cohesion by using these techniques:

- Repetition.

Now let’s look at these in more detail.

Repeating words may contribute to cohesion. Repetition creates cohesive ties within the text.

- Birds are beautiful. I like birds.

You can use a word or phrase that means exactly or nearly the same as another word to achieve cohesion.

- Paul saw a snake under the mattress. The serpent was probably hiding there for a long time.

Antonymy refers to the use of a word of opposite meaning. This is often used to create links between the elements of a text.

- Old movies are boring, the new ones are much better.

This refers to the use of a word that denotes a subcategory of a more general class.

- I saw a cat . The animal was very hungry and looked ill.

Relating a superordinate term (i.e. animal) to a corresponding subordinate term (i.e. cat) may create more cohesiveness between sentences and clauses.

Meronymy is another way to achieve cohesion. It refers to the use of a word that denotes part of something but which is used to refer to the whole of it for instance faces can be used to refer to people as in “I see many faces here”. In the following example, hands refer to workers.

- More workers are needed. We need more hands to finish the work.

Grammatical cohesion

Grammatical cohesion refers to the grammatical relations between text elements. This includes the use of:

- Cataphora .

- Substitutions.

- Conjunctions and transition words.

Let us illustrate the above devices with some examples.

Anaphora is when you use a word referring back to another word used earlier in a text or conversation.

- Jane was brilliant. She got the best score.

The pronoun “she” refers back to the proper noun “Jane”.

Cataphora is the opposite of anaphora. Cataphora refers to the use of a word or phrase that refers to or stands for a following word or phrase.

- Here he comes our hero. Please, welcome John .

The pronoun “he” refers back to the proper noun “John”.

Ellipsis refers to the omission from speech or writing of a word or words that are superfluous or able to be understood from contextual clues.

- Liz had some chocolate bars, and Nancy an ice cream.

In the above example, “had” in “Nancy an ice cream” is left because it can be understood (or presupposed) as it was already mentioned previously in the sentence.

Elliptic elements can be also understood from the context as in:

- A: Where are you going?

Substitutions

Substitutions refer to the use of a word to replace another word.

- A: Which T-shirt would you like?

- B: I would like the pink one .

Conjunctions transition words

Conjunctions and transition words are parts of speech that connect words, phrases, clauses, or sentences.

- Examples of conjunctions: but, or, and, although, in spite of, because,

- Examples of transition words: however, similarly, likewise, specifically, consequently, for this reason, in contrast to, accordingly, in essence, chiefly, finally.

Here are some examples:

- I called Tracy and John.

- He was tired but happy.

- She likes neither chocolates nor cookies.

- You can either finish the work or ask someone to do it for you.

- He went to bed after he had done his homework.

- Although she is very rich, she isn’t happy.

- I was brought up to be responsible. Similarly , I will try to teach my kids how to take responsibility for their actions.

Cohesive but not coherent texts

Sometimes, a text may be cohesively connected, yet may still be incoherent.

Learners may wrongly think that simply linking sentences together will lead to a coherent text.

Here is an example of a text in which sentences are cohesively connected, yet the overall coherence is lacking:

The player threw the ball toward the goalkeeper. Balls are used in many sports. Most balls are spheres, but American football is an ellipsoid. Fortunately, the goalkeeper jumped to catch the ball. The crossbar in the soccer game is made of iron. The goalkeeper was standing there.

The sentences and phrases in the above text are decidedly cohesive but not coherent.

There is a use of:

- Repetition of: the ball, goalkeeper, the crossbar.

- Conjunctions and transition words: but, fortunately.

The use of the above cohesive devices does not result in a meaningful and unified whole. This is because the writer presents material that is unrelated to the topic. Why should a writer talk about what the crossbar is made of? And is talking about the form balls in sports relevant in this context? What is the central focus of the text?

A coherent essay has to be cohesively connected and logically expressive of the central topic.

How to write a coherent essay?

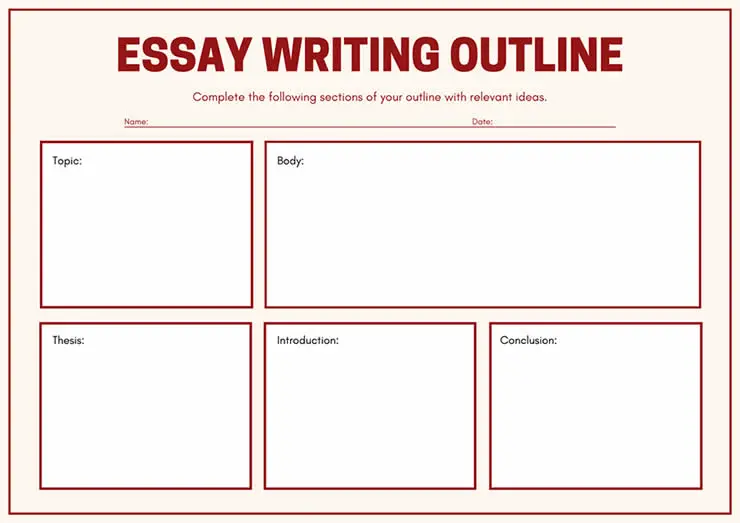

1. start with an outline.

An outline is the general plan of your essays. It contains the ideas you will include in each paragraph and the sequence in which these ideas will be mentioned.

It is important to have an outline before starting to write. Spending a few minutes on the outline can be rewarding. An outline will organize your ideas and the end product can be much more coherent.

Here is how you can outline your writing so that you can produce a coherent essay:

- Start with the thesis statement – the sentence that summarizes the topic of your writing.

- Brainstorm the topic for a few minutes. Write down all the ideas related to the topic.

- Sift the ideas brainstormed in the previous step to identify only the ideas worth including in your essay.

- Organize ideas in a logical order so that your essay reflects the unified content that you want to communicate.

- Each idea has to be treated in a separate paragraph.

- Think of appropriate transitions between the different ideas.

- Under each idea/paragraph, write down enough details to support your idea.

After identifying and organizing your ideas into different paragraphs, they have to fit within the conventional structure of essays.

2. Structure your essay

It is also important to structure your essay so that you the reader can identify the organization of the different parts of your essay and how each paragraph leads to the next one.

Here is a structure of an essay

3. Structure your paragraphs

Paragraphs have to be well-organized. The structure of each paragraph should have:

- A topic sentence that is usually placed at the beginning,

- Supporting details that give further explanation of the topic sentence,

- And a concluding sentence that wraps up the content of the paragraph.

The supporting sentences in each paragraph must flow smoothly and logically to support the purpose of the topic sentence. Similarly, each paragraph has to serve the thesis statement, the main topic of the essay.

4. Relevance to the main topic

No matter how long the essay is, we should make sure that we stick to the topic we want to talk about. Coherence is about making everything flow smoothly to create unity. So, sentences and ideas must be relevant to the central thesis statement.

The writer has to maintain the flow of ideas to serve the main focus of the essay.

5. Stick to the purpose of the type of essay you’re-writing

Essays must be clear and serve a purpose and direction. This means that the writer’s thoughts must not go astray in developing the purpose of the essay.

Essays are of different types and have different purposes. Accordingly, students have to stick to the main purpose of each genre of writing.

- An expository essay aims to inform, describe, or explain a topic, using essential facts to teach the reader about a topic.

- A descriptive essay intends to transmit a detailed description of a person, event, experience, or object. The aim is to make the reader perceive what is being described.

- A narrative essay attempts to tell a story that has a purpose. Writers use storytelling techniques to communicate an experience or an event.

- In argumentative essays, writers present an objective analysis of the different arguments about a topic and provide an opinion or a conclusion of positive or negative implications. The aim is to persuade the reader of your point.

6. Use cohesive devices and signposting phrases

Sentences should be connected using appropriate cohesive devices as discussed above:

Cohesive devices such as conjunctions and transition words are essential in providing clarity to your essay. But we can add another layer of clarity to guide the reader throughout the essay by using signpost signals.

What is signposting in writing?

Signposting refers to the use of phrases or words that guide readers to understand the direction of your essay. An essay should take the reader on a journey throughout the argumentation or discussion. In that journey, the paragraphs are milestones. Using signpost signals assists the reader in identifying where you want to guide them. Signposts serve to predict what will happen, remind readers of where they are at important stages along the process, and show the direction of your essay.

Essay signposting phrases

The following are some phrases you can use to signpost your writing:

It should be noted though that using cohesive devices or signposting language may not automatically lead to a coherent text. Some texts can be highly cohesive but remain incoherent. Appropriate cohesion and signposting are essential to coherence but they are not enough. To be coherent, an essay has to follow, in addition to using appropriate cohesive devices, all the tips presented in this article.

7. Draft, revise, and edit

After preparing the ground for the essay, students produce their first draft. This is the first version of the essay. Other subsequent steps are required.

The next step is to revise the first draft to rearrange, add, or remove paragraphs, ideas, sentences, or words.

The questions that must be addressed are the following:

- Is the essay clear? Is it meaningful? Does it serve the thesis statement (the main topic)?

- Are there sufficient details to convey ideas?

- Are there any off-topic ideas that you have to do without?

- Have you included too much information? Does your writing stray off-topic?

- Do the ideas flow in a logical order?

- Have you used appropriate cohesive devices and transition words when needed?

Once the revision is done, it is high time for the editing stage. Editing involves proofreading and correcting mistakes in grammar and mechanics. Pay attention to:

- Verb tense.

- Subject-verb agreement.

- Sentence structure. Have you included a subject a verb and an object (if the verb is transitive.)

- Punctuation.

- Capitalization.

Coherent essays are identified by relevance to the thesis statement. The ideas and sentences of coherent essays flow smoothly. One can follow the ideas discussed without any problems. Lexical and grammatical cohesive devices are used to achieve coherence. However, these devices are not sufficient. To maintain relevance to the main focus of the text, there is a need for a whole process of collecting ideas, outlining, reviewing, and editing to create a coherent whole.

More writing lessons are here .

Related Pages:

- Figures of speech

- Articles about writing

- I nfographics

- Show AWL words

- Subscribe to newsletter

- What is academic writing?

- Academic Style

- What is the writing process?

- Understanding the title

- Brainstorming

- Researching

- First draft

- Proofreading

- Report writing

- Compare & contrast

- Cause & effect

- Problem-solution

- Classification

- Essay structure

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Book review

- Research proposal

- Thesis/dissertation

What is cohesion?

- Cohesion vs coherence

Transition signals

- What are references?

- In-text citations

- Reference sections

- Reporting verbs

- Band descriptors

Show AWL words on this page.

Levels 1-5: grey Levels 6-10: orange

Show sorted lists of these words.

Any words you don't know? Look them up in the website's built-in dictionary .

Choose a dictionary . Wordnet OPTED both

Cohesion How to make texts stick together

Cohesion and coherence are important features of academic writing. They are one of the features tested in exams of academic English, including the IELTS test and the TOEFL test . This page gives information on what cohesion is and how to achieve good cohesion. It also explains the difference between cohesion and coherence , and how to achieve good coherence. There is also an example essay to highlight the main features of cohesion mentioned in this section, as well as some exercises to help you practise.

For another look at the same content, check out YouTube or Youku , or the infographic .

It is important for the parts of a written text to be connected together. Another word for this is cohesion . This word comes from the verb cohere , which means 'to stick together'. Cohesion is therefore related to ensuring that the words and sentences you use stick together.

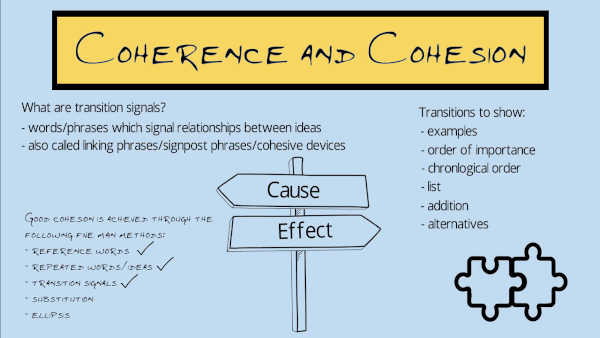

Good cohesion is achieved through the following five main methods, each of which is described in more detail below:

- repeated words/ideas

- reference words

- transition signals

- substitution

Two other ways in which cohesion is achieved in a text, which are covered less frequently in academic English courses, are shell nouns and thematic development . These are also considered below.

Repeated words/ideas

Check out the cohesion infographic »

One way to achieve cohesion is to repeat words, or to repeat ideas using different words (synonyms). Study the following example. Repeated words (or synonyms) are shown in bold.

Cohesion is an important feature of academic writing . It can help ensure that your writing coheres or 'sticks together', which will make it easier for the reader to follow the main ideas in your essay or report . You can achieve good cohesion by paying attention to five important features . The first of these is repeated words. The second key feature is reference words. The third one is transition signals. The fourth is substitution. The final important aspect is ellipsis.

In this example, the word cohesion is used several times, including as a verb ( coheres ). It is important, in academic writing, to avoid too much repetition, so using different word forms or synonyms is common. The word writing is also used several times, including the phrase essay or report , which is a synonym for writing . The words important features are also repeated, again using synonyms: key feature , important aspect .

Reference words

Reference words are words which are used to refer to something which is mentioned elsewhere in the text, usually in a preceding sentence. The most common type is pronouns, such as 'it' or 'this' or 'these'. Study the previous example again. This time, the reference words are shown in bold.

Cohesion is an important feature of academic writing. It can help ensure that your writing coheres or 'sticks together', which will make it easier for the reader to follow the main ideas in your essay or report. You can achieve good cohesion by paying attention to five important features. The first of these is repeated words. The second key feature is reference words. The third one is transition signals. The fourth is substitution. The final important aspect is ellipsis.

The words it , which and these are reference words. The first two of these, it and which , both refer to 'cohesion' used in the preceding sentence. The final example, these , refers to 'important features', again used in the sentence that precedes it.

Transition signals, also called cohesive devices or linking words, are words or phrases which show the relationship between ideas. There are many different types, the most common of which are explained in the next section on transition signals . Some examples of transition signals are:

- for example - used to give examples

- in contrast - used to show a contrasting or opposite idea

- first - used to show the first item in a list

- as a result - used to show a result or effect

Study the previous example again. This time, the transition signals are shown in bold. Here the transition signals simply give a list, relating to the five important features: first , second , third , fourth , and final .

Substitution

Substitution means using one or more words to replace (substitute) for one or more words used earlier in the text. Grammatically, it is similar to reference words, the main difference being that substitution is usually limited to the clause which follows the word(s) being substituted, whereas reference words can refer to something far back in the text. The most common words used for substitution are one , so , and auxiliary verbs such as do, have and be . The following is an example.

- Drinking alcohol before driving is illegal in many countries, since doing so can seriously impair one's ability to drive safely.

In this sentence, the phrase 'doing so' substitutes for the phrase 'drinking alcohol before driving' which appears at the beginning of the sentence.

Below is the example used throughout this section. There is just one example of substitution: the word one , which substitutes for the phrase 'important features'.

Ellipsis means leaving out one or more words, because the meaning is clear from the context. Ellipsis is sometimes called substitution by zero , since essentially one or more words are substituted with no word taking their place.

Below is the example passage again. There is one example of ellipsis: the phrase 'The fourth is', which means 'The fourth [important feature] is', so the words 'important feature' have been omitted.

Shell nouns

Shell nouns are abstract nouns which summarise the meaning of preceding or succeeding information. This summarising helps to generate cohesion. Shell nouns may also be called carrier nouns , signalling nouns , or anaphoric nouns . Examples are: approach, aspect, category, challenge, change, characteristics, class, difficulty, effect, event, fact, factor, feature, form, issue, manner, method, problem, process, purpose, reason, result, stage, subject, system, task, tendency, trend, and type . They are often used with pronouns 'this', 'these', 'that' or 'those', or with the definite article 'the'. For example:

- Virus transmission can be reduced via frequent washing of hands, use of face masks, and isolation of infected individuals. These methods , however, are not completely effective and transmission may still occur, especially among health workers who have close contact with infected individuals.

- An increasing number of overseas students are attending university in the UK. This trend has led to increased support networks for overseas students.

In the example passage used throughout this section, the word features serves as a shell noun, summarising the information later in the passage.

Cohesion is an important feature of academic writing. It can help ensure that your writing coheres or 'sticks together', which will make it easier for the reader to follow the main ideas in your essay or report. You can achieve good cohesion by paying attention to five important features . The first of these is repeated words. The second key feature is reference words. The third one is transition signals. The fourth is substitution. The final important aspect is ellipsis.

Thematic development

Cohesion can also be achieved by thematic development. The term theme refers to the first element of a sentence or clause. The development of the theme in the rest of the sentence is called the rheme . It is common for the rheme of one sentence to form the theme of the next sentence; this type of organisation is often referred to as given-to-new structure, and helps to make writing cohere.

Consider the following short passage, which is an extension of the first example above.

- Virus transmission can be reduced via frequent washing of hands, use of face masks, and isolation of infected individuals. These methods, however, are not completely effective and transmission may still occur, especially among health workers who have close contact with infected individuals. It is important for such health workers to pay particular attention to transmission methods and undergo regular screening.

Here we have the following pattern:

- Virus transmission [ theme ]

- can be reduced via frequent washing of hands, use of face masks, and isolation of infected individuals [ rheme ]

- These methods [ theme = rheme of preceding sentence ]

- are not completely effective and transmission may still occur, especially among health workers who have close contact with infected individuals [ rheme ]

- health workers [ theme, contained in rheme of preceding sentence ]

- [need to] to pay particular attention to transmission methods and undergo regular screening [ rheme ]

Cohesion vs. coherence

The words 'cohesion' and 'coherence' are often used together with a similar meaning, which relates to how a text joins together to make a unified whole. Although they are similar, they are not the same. Cohesion relates to the micro level of the text, i.e. the words and sentences and how they join together. Coherence , in contrast, relates to the organisation and connection of ideas and whether they can be understood by the reader, and as such is concerned with the macro level features of a text, such as topic sentences , thesis statement , the summary in the concluding paragraph (dealt with in the essay structure section), and other 'bigger' features including headings such as those used in reports .

Coherence can be improved by using an outline before writing (or a reverse outline , which is an outline written after the writing is finished), to check that the ideas are logical and well organised. Asking a peer to check the writing to see if it makes sense, i.e. peer feedback , is another way to help improve coherence in your writing.

Example essay

Below is an example essay. It is the one used in the persuasion essay section. Click on the different areas (in the shaded boxes to the right) to highlight the different cohesive aspects in this essay, i.e. repeated words/ideas, reference words, transition signals, substitution and ellipsis.

Title: Consider whether human activity has made the world a better place.

History shows that human beings have come a long way from where they started. They have developed new technologies which means that everybody can enjoy luxuries they never previously imagined. However , the technologies that are temporarily making this world a better place to live could well prove to be an ultimate disaster due to , among other things, the creation of nuclear weapons , increasing pollution , and loss of animal species . The biggest threat to the earth caused by modern human activity comes from the creation of nuclear weapons . Although it cannot be denied that countries have to defend themselves, the kind of weapons that some of them currently possess are far in excess of what is needed for defence . If these [nuclear] weapons were used, they could lead to the destruction of the entire planet . Another harm caused by human activity to this earth is pollution . People have become reliant on modern technology, which can have adverse effects on the environment . For example , reliance on cars causes air and noise pollution . Even seemingly innocent devices, such as computers and mobile phones, use electricity, most of which is produced from coal-burning power stations, which further adds to environmental pollution . If we do not curb our direct and indirect use of fossil fuels, the harm to the environment may be catastrophic. Animals are an important feature of this earth and the past decades have witnessed the extinction of a considerable number of animal species . This is the consequence of human encroachment on wildlife habitats, for example deforestation to expand cities. Some may argue that such loss of [animal] species is natural and has occurred throughout earth's history. However , the current rate of [animal] species loss far exceeds normal levels [of animal species loss] , and is threatening to become a mass extinction event. In summary , there is no doubt that current human activities such as the creation of nuclear weapons , pollution , and destruction of wildlife , are harmful to the earth . It is important for us to see not only the short-term effects of our actions, but their long-term ones as well. Otherwise , human activities will be just another step towards destruction .

Aktas, R.N. and Cortes, V. (2008), 'Shell nouns as cohesive devices in published and ESL student writing', Journal of English for Academic Purposes , 7 (2008) 3-14.

Alexander, O., Argent, S. and Spencer, J. (2008) EAP Essentials: A teacher's guide to principles and practice . Reading: Garnet Publishing Ltd.

Gray, B. (2010) 'On the use of demonstrative pronouns and determiners as cohesive devices: A focus on sentence-initial this/these in academic prose', Journal of English for Academic Purposes , 9 (2010) 167-183.

Halliday, M. A. K., and Hasan, R. (1976). Cohesion in English . London: Longman.

Hinkel, E. (2004). Teaching Academic ESL Writing: Practical Techniques in Vocabulary and Grammar . Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc Publishers.

Hyland, K. (2006) English for Academic Purposes: An advanced resource book . Abingdon: Routledge.

Thornbury, S. (2005) Beyond the Sentence: Introducing discourse analysis . Oxford: Macmillan Education.

GET FREE EBOOK

Like the website? Try the books. Enter your email to receive a free sample from Academic Writing Genres .

Below is a checklist for essay cohesion and coherence. Use it to check your own writing, or get a peer (another student) to help you.

Next section

Find out more about transition signals in the next section.

- Transitions

Previous section

Go back to the previous section about paraphrasing .

- Paraphrasing

Exercises & Activities Some ways to practise this area of EAP

You need to login to view the exercises. If you do not already have an account, you can register for free.

- Register

- Forgot password

- Resend activiation email

Author: Sheldon Smith ‖ Last modified: 03 February 2022.

Sheldon Smith is the founder and editor of EAPFoundation.com. He has been teaching English for Academic Purposes since 2004. Find out more about him in the about section and connect with him on Twitter , Facebook and LinkedIn .

Compare & contrast essays examine the similarities of two or more objects, and the differences.

Cause & effect essays consider the reasons (or causes) for something, then discuss the results (or effects).

Discussion essays require you to examine both sides of a situation and to conclude by saying which side you favour.

Problem-solution essays are a sub-type of SPSE essays (Situation, Problem, Solution, Evaluation).

Transition signals are useful in achieving good cohesion and coherence in your writing.

Reporting verbs are used to link your in-text citations to the information cited.

Pasco-Hernando State College

- Unity and Coherence in Essays

- The Writing Process

- Paragraphs and Essays

- Proving the Thesis/Critical Thinking

- Appropriate Language

Test Yourself

- Essay Organization Quiz

- Sample Essay - Fairies

- Sample Essay - Modern Technology

Related Pages

- Proving the Thesis

Unity is the idea that all parts of the writing work to achieve the same goal: proving the thesis. Just as the content of a paragraph should focus on a topic sentence, the content of an essay must focus on the thesis. The introduction paragraph introduces the thesis, the body paragraphs each have a proof point (topic sentence) with content that proves the thesis, and the concluding paragraph sums up the proof and restates the thesis. Extraneous information in any part of the essay which is not related to the thesis is distracting and takes away from the strength of proving the thesis.

An essay must have coherence. The sentences must flow smoothly and logically from one to the next as they support the purpose of each paragraph in proving the thesis. .

Just as the last sentence in a paragraph must connect back to the topic sentence of the paragraph, the last paragraph of the essay should connect back to the thesis by reviewing the proof and restating the thesis.

Example of Essay with Problems of Unity and Coherence

Here is an example of a brief essay that includes a paragraph that does not support the thesis “Many people are changing their diets to be healthier.”

People are concerned about pesticides, steroids, and antibiotics in the food they eat. Many now shop for organic foods since they don’t have the pesticides used in conventionally grown food. Meat from chicken and cows that are not given steroids or antibiotics are gaining in popularity even though they are much more expensive. More and more, people are eliminating pesticides, steroids, and antibiotics from their diets.

Eating healthier also is beneficial to the environment since there are less pesticides poisoning the earth. Pesticides getting into the waterways is creating a problem with drinking water. Historically, safe drinking water has been a problem. It is believed the Ancient Egyptians drank beer since the water was not safe to drink. Brewing beer killed the harmful organisms and bacteria in the water from the Nile.

There is a growing concern about eating genetically modified foods, and people are opting for non-GMO diets. Some people say there are more allergic reactions and other health problems resulting from these foods. Others are concerned because there are no long-term studies which clearly show no adverse health effects such as cancers or other illnesses. Avoiding GMO food is another way people are eating healthier food.

See how just one paragraph can take away from the effectiveness of the essay in showing how people are changing to healthier food since the unity and coherence are affected. There is no longer unity among all the paragraphs. The thought pattern is disjointed and the essay loses its coherence.

Transitions and Logical Flow of Ideas

Transitions are words, groups of words, or sentences that connect one sentence to another or one paragraph to another.

They promote a logical flow from one idea to the next and overall unity and coherence.

While transitions are not needed in every sentence or at the end of every paragraph, they are missed when they are omitted since the flow of thoughts becomes disjointed or even confusing.

There are different types of transitions:

Time – before, after, during, in the meantime, nowadays

Space – over, around, under

Examples – for instance, one example is

Comparison – on the other hand, the opposing view

Consequence – as a result, subsequently

These are just a few examples. The idea is to paint a clear, logical connection between sentences and between paragraphs.

- Printer-friendly version

Achieving coherence

“A piece of writing is coherent when it elicits the response: ‘I follow you. I see what you mean.’ It is incoherent when it elicits the response: ‘I see what you're saying here, but what has it got to do with the topic at hand or with what you just told me above?’ ” - Johns, A.M

Transitions

Parallelism, challenge task, what is coherence.

Coherence in a piece of writing means that the reader can easily understand it. Coherence is about making everything flow smoothly. The reader can see that everything is logically arranged and connected, and relevance to the central focus of the essay is maintained throughout.

Repetition in a piece of writing does not always demonstrate cohesion. Study these sentences:

So, how does repetition as a cohesive device work?

When a pronoun is used, sometimes what the pronoun refers to (ie, the referent) is not always clear. Clarity is achieved by repeating a key noun or synonym . Repetition is a cohesive device used deliberately to improve coherence in a text.

In the following text, decide ifthe referent for the pronoun it is clear. Otherwise, replace it with the key noun English where clarity is needed.

Click here to view the revised text.

Suggested improvement

English has almost become an international language. Except for Chinese, more people speak it (clear reference; retain) than any other language. Spanish is the official language of more countries in the world, but more countries have English ( it is replaced with a key noun) as their official or unofficial second language. More than 70% of the world's mail is written in English ( it is replaced with a key noun). It (clear reference; retain) is the primary language on the Internet.

Sometimes, repetition of a key noun is preferred even when the reference is clear. In the following text, it is clear that it refers to the key noun gold , but when used throughout the text, the style becomes monotonous.

Improved text: Note where the key noun gold is repeated. The deliberate repetition creates interest and adds maturity to the writing style.

Gold , a precious metal, is prized for two important characteristics. First of all, gold has a lustrous beauty that is resistant to corrosion. Therefore, it is suitable for jewellery, coins and ornamental purposes. Gold never needs to be polished and will remain beautiful forever. For example, a Macedonian coin remains as untarnished today as the day it was made 23 centuries ago. Another important characteristic of gold is its usefulness to industry and science. For many years, it has been used in hundreds of industrial applications. The most recent use of gold is in astronauts’ suits. Astronauts wear gold -plated shields when they go outside spaceships in space. In conclusion, gold is treasured not only for its beauty but also its utility.

Pronoun + Repetition of key noun

Sometimes, greater cohesion can be achieved by using a pronoun followed by an appropriate key noun or synonym (a word with a similar meaning).

Transitions are like traffic signals. They guide the reader from one idea to the next. They signal a range of relationships between sentences, such as comparison, contrast, example and result. Click here for a more comprehensive list of Transitions (Logical Organisers) .

Test yourself: How well do you understand transitions?

Which of the three alternatives should follow the transition or logical organiser in capital letters to complete the second sentence?

Using transitions/logical organisers

Improve the coherence of the following paragraph by adding transitions in the blank spaces. Use the italicised hint in brackets to help you choose an apporpriate transition for each blank. If you need to, review the list of Transitions (Logical Organisers) before you start.

Using transitions

Choose the most appropriate transition from the options given to complete the article:

Overusing transitions

While the use of appropriate transitions can improve coherence (as the previous practice activity shows), it can also be counterproductive if transitions are overused. Use transitions carefully to enhance and clarify the logical connection between ideas in extended texts. Write a range of sentences and vary sentence openings.

Study the following examples:

Identifying cohesive devices

When it comes to writing, people usually emphasise the importance of good grammar and proper spelling. However, there is a third element that actually helps authors get their thoughts across to readers, that is cohesiveness in writing.

In writing, cohesiveness is the quality that makes it easier for people to read and understand an essay’s content. A cohesive essay has all its parts (beginning, middle, and end) united, supporting each other to inform or convince the reader.

Unfortunately, this is an element that even intermediate or advanced writers stumble on. While the writer’s thoughts are in their compositions, all too often readers find it difficult to understand what is being said because of the poor organisation of ideas. This article provides tips on how you can make your essay cohesive.

1. Identify the thesis statement of your essay

A thesis statement states what your position is regarding the topic you are discussing. To make an essay worth reading, you will need to make sure that you have a compelling stance.

However, identifying the thesis statement is only the first step. Each element that you put in your essay should be included in a way that supports your argument, which should be the focus of your writing. If you feel that some of the thoughts you initially included do not contribute to strengthening your position, it might be better to take them out when you revise your essay to have a more powerful piece.

2. Create an outline

One of the common mistakes made by writers is that they tend to add a lot of details to their essay which, while interesting, may not really be relevant to the topic at hand. Another problem is jumping from one thought to another, which can confuse a reader if they are not familiar with the subject.

Preparing an outline can help you avoid these difficulties. List the ideas you have in mind for your essay, and then see if you can arrange these thoughts in a way that would make it easy for your readers to understand what you are saying.

While discursive essays do not usually contain stories, the same principle still applies. Your writing should have an introduction, a discussion portion and a conclusion. Again, make sure that each segment supports and strengthens your thesis statement.

As a side note, a good way to write the conclusion of your essay is to mention the points that you raised in your introduction. At the same time, you should use this section to summarise main ideas and restate your position to drive the message home to your readers.

3. Make sure everything is connected

In connection to the previous point, make sure that each section of your essay is linked to the one after it. Think of your essay as a story: it should have a beginning, middle, and end, and the way that you write your piece should logically tie these elements together in a linear manner.

4. Proofread before submitting your essay

Make sure to review your composition prior to submission. In most cases, the first draft may be a bit disorganised because this is the first time that your thoughts have been laid out on paper. By reviewing what you have written, you will be able to see which parts need editing, and which ones can be rearranged to make your essay more easily understood by your readers. Try to look at what you wrote from the point of view of your audience. Will they be able to understand your train of thought, or do you need to reorganise some parts to make it easier for them to appreciate what you are saying? Taking another look at your essay and editing it can do wonders for how your composition flows.

Writing a cohesive essay could be a lot easier than you think – especially when you follow these steps. Don’t forget that reading complements writing: try reading essays on various topics and see if each of their parts supports their identified goal or argument.

Cohesion and Coherence

Introduction

Every writer wishes to make their points clearly to their readers, with pieces of writing that are are easy to read and have logical links between the various points made. This coherence , this clarity of expression , is created by grammar and vocabulary (lexis) through cohesion . This is the “glue” that joins your ideas together to form a cohesive whole.

In this Learning Object we are going to focus on how this is done, in order to assist you when you come to write your next assignments and in your reading. In reading, if you understand how the author makes connections within the text, you gain a better understanding of his or her message. As regards your writing, after analysing the texts in this Learning Object, you should analyse your own writing in the same way. This will help you to realise which techniques you could use more to benefit your reader.

Before starting the activities, you can obtain an overview of how best to use this Learning Object, using a Screencast (with audio), by following this link Overview

- To raise awareness of how cohesion contributes to coherence in text

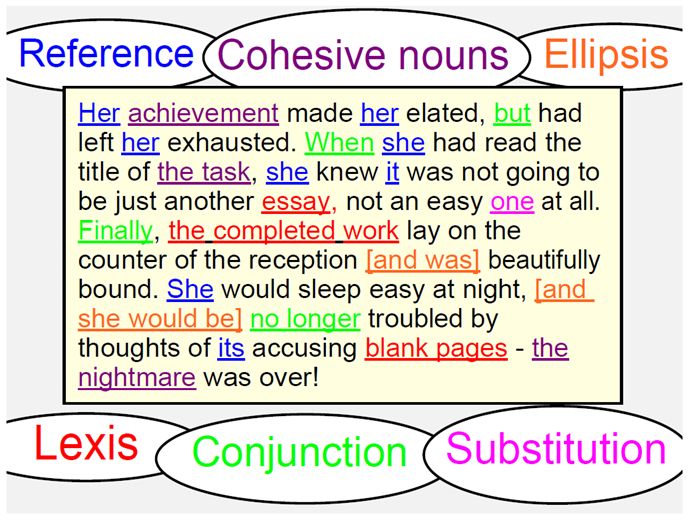

- To raise awareness of how cohesion is created through: reference, conjunction, ellipsis, substitution and lexis , including cohesive nouns .

- To raise your awareness of cohesion at paragraph level and how punctuation plays a crucial role in this

Activity 1: Ways of creating cohesion in text

According to the writers Halliday and Hasan (1976), there are six main ways that cohesion is created in a text. These they called: Reference , Substitution , Ellipsis , Lexical Chains , Cohesive Nouns and Conjunction .

Open this Cohesion Presentation PDF document that shows you examples of each of them.

For the following six ways of creating cohesion, select each one to read detailed explanations and examples:

This way of creating cohesion uses:

- determiners (e.g. "this" , "that" , "these" and "those" );

- pronouns (e.g. "him" , "them" , "me" );

- possessive pronouns (e.g. "your" , "their" , "hers" );

- relative pronouns (e.g. "which" , "who" , "whose" ).

- This type of cohesion can also be achieved comparatively with expressions like: "similarly" , "likewise" , "less" .

In this way of creating cohesion you can use:

- synonyms (e.g. "beautiful" for "lovely" );

- hyponyms and superordinates (e.g. "daffodil" , "rose" and "daisy" , are all hyponyms of the superordinate "flower" ).

- Lexical chains are created in a text by using words in the same lexical set (e.g. "army" , "soldiers" , "barracks" , "weapons" ).

These techniques allow for the central themes to be reiterated in a way that avoids monotony for the reader.

These words are a kind of lexical reference.

- They can summarise many words in one (e.g. "attitude" , "solution" , "difficulty" ), and have been called 'umbrella' nouns for this reason (Bailey 2006:150).

- They are used to signal what is to come (e.g. "the problem to be discussed..." ), or can refer back (e.g. "The issue mentioned above..." ).

This method of creating cohesion uses one word/phrase to replace a word/phrase used earlier. For example,

- "the one(s)" and "the same" can be used to replace nouns (e.g. "I'll have the same." ).

- Verbs can be replaced by "do" (e.g. "The authorities said they had acted , but nobody believed they had done .").

- In speaking, whole clauses can be replaced by, "so" or "not" (e.g. "I hope so/not." ).

In this way of creating cohesion, words are omitted because they are understood from the context. e.g.

- " John can type and I can [type] too! ";

- " I don't want to go out, do you? [want to go out] ."

This type of cohesion includes:

- listing words (e.g. "firstly" , "next" , "lastly" );

- linkers for addition (e.g. " moreover" , "and" , "also" );

- concession (e.g. "but" , "however" , "despite" ); and

- cause and effect (e.g. "so" , "because" , "as a result" ).

Then try this Cohesion quiz to test your memory of the terms.

Activity 2: Highlighting cohesion in a text

For this activity you are going to read the short narrative text below, which is a piece of creative writing about a student, and then complete an exercise in highlighting the cohesive words, using colour codes. First, read the text quickly and try to think of a title for it.

The student sighed as she handed in the assignment, at last it was finished. This was the most difficult piece of writing which she had been set, but she had completed it. The ‘magnum opus’ was 10,000 words long. This project, though not quite a dissertation, was still the longest piece of academic writing she had ever written. She had thought she would never complete it and it had taken all her strength to do so.

Her achievement made her elated, but had left her exhausted. When she had read the title of the task, she knew it was not going to be just another essay, not an easy one at all. Finally, the completed work lay on the counter of the reception [and was] beautifully bound. She would sleep easy at night, [and she would be] no longer troubled by thoughts of its accusing blank pages – the nightmare was over!

Instruction

Now try this colour coding exercise to highlight the 6 different ways of creating cohesion.

--> Show feedback Hide feedback

The original title of the piece of writing was “The Assignment” .

Now try this interactive exercise to colour-code the words and phrases that create cohesion in the 6 different ways using the six colours.

You can download this Feedback 1 PDF for a summary of the answers to the task.

Activity 3: Cohesion in a discursive text

In this exercise you are going to see how the 6 ways of creating cohesion are used in a short text arguing in favour of working in groups as a way to learn better in class. Before you read the text, you might like to predict what the arguments might be in favour of and against classes being organised to work together in this way.

To do a series of exercises to raise awareness of different forms of cohesion used in academic writing, try these interactive cloze exercises .

Activity 4: Colour coding the cohesion in the discursive text

Now, we are going to use the same text to see how your awareness of cohesion is improving.

Read this longer discursive text about working in groups. As you read, notice the different forms of cohesion that are used in the text. After you’ve read it, move on to the colour-coding exercise that follows.

“Working in groups is a bad idea because it encourages weak students to let the others do the work.” Discuss

The idea that working in groups is a bad thing is fundamentally mistaken because, overall, the advantages of this way of configuring the class outweigh the potential disadvantages [of this way of configuring the class]. In groups there is the opportunity for peer teaching, which can often be invaluable. In addition, lessons organised in this way become less teacher-centred. Moreover, in life today, team-working is a feature of every workplace and one of the roles of university education is to provide a preparation for students’ future careers.

Firstly, peer teaching can contribute to effective learning in most classroom situations. Many students (especially in large classes) can benefit from this approach. Weaker students are often less afraid of making mistakes and taking risks in front of their peers, than in close contact with their teacher or in front of the whole class. Also, with regard to the stronger students, a perfect way to consolidate their learning is to transmit that knowledge to others. Furthermore, most pedagogic approaches today concur that a lesson that is focused on the teacher at all times, is one from which the students are unlikely to benefit. Certainly, some classroom activities, like project work for example, are best conducted in small groups. The teacher as the source of all wisdom standing at the front of the class, the ‘jug and mug’ model of education, is not only antiquated, but also ineffective.

A further benefit of group-teaching is the preparation it provides for working in teams. In a great variety of careers today, the employees are asked to, and are judged on their ability to work in teams. Group working in class represents basically the same concept. The same skills are being tested and developed – interpersonal skills and emotional intelligence, to mention just two. In business today, the ability to lead effectively and to support one’s peers is prized almost above all other skills.

In conclusion then, while it may sometimes be true that the weak students may ‘take it easy’ sometimes in groups, allowing others to work hard to compensate for their laziness, if the lesson materials are interesting and the teacher motivating, this is a rare occurrence. As outlined above, there are so many ‘pros’ to this method of classroom configuration that these easily outweigh this somewhat questionable ‘con’.

Now try these Cohesion colour-coding exercies , using the 6 different colours.

Show feedback Hide feedback

You can download this Feedback 2 PDF document for a summary of the answers to the task.

Activity 5: Cohesive nouns, reference and substitution

For more exercises to practise cohesive nouns, reference and substitution try this Reference and Substitution cloze exercise .

Activity 6: Cohesion and coherence at paragraph level

Cohesion has a strong connection to coherence (logic and meaning). In fact, cohesion is the grammatical and lexical realisation of coherence at a profound level within the text. It is what makes a text more than just a jumbled mixture of sentences.

In this exercise, you will use your understanding of cohesion and punctuation, and your understanding of the underlying meaning of paragraphs, to put them into the most logical order. Now try these Paragraph Cohesion Activities .

Would you like to review the main points?

Show review Hide review

To review the way we create cohesion in texts follow this link The 6 Ways of Creating Cohesion

For websites with more information and exercises to raise your awareness of cohesion and the way we organise information following a ‘given-to-new’ pattern, we recommend the following websites:

- The Grammar of English Ideas

- Academic Writing in English

References:

Batstone, R. (1994). Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Cook, G. (1996). Discourse. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Halliday, M. A. K. and R. Hasan (1976). Cohesion in English. London: Longman UK Group Limited.

Lubelska, D. (1991). “An approach to teaching cohesion to improve in reading” in Reading in a Foreign Language, 7 (2)

© William Tweddle, Queen Mary, University of London, 2010, visual created by the author using a Smartboard and Jing

Coherence And Cohesion: Writing Tips For Seamless Texts

Learn coherence and cohesion secrets to create seamlessly flowing, impactful writing. Read this content and understand both.

Understanding the importance of coherence and cohesion in writing is fundamental, as these principles significantly impact how well your message is conveyed to the reader. These concepts empower you to create clear, logical, and organized content.

When your writing lacks coherence, it may appear disjointed, confusing, and challenging for the reader to follow. On the other hand, without cohesion, your ideas may seem scattered and unrelated. Mastering these aspects not only enhances the overall quality of your writing but also ensures your audience can easily grasp and appreciate the information you’re presenting.

In this article, you will gain an in-depth understanding of these essential elements. The exploration begins with a clear definition of coherence and cohesion, followed by an examination of their intricate relationship.

Definition Of Coherence

Coherence is a fundamental aspect of effective communication through written language. It encompasses the logical and orderly arrangement of ideas, details, and arguments within a text, ensuring that they connect seamlessly to convey a clear and unified message. Coherent writing allows readers to follow the author’s thought process without confusion or disruption.

This connection of ideas is achieved through the strategic use of organization, structure, transitional elements, and logical progression. In essence, coherence is the glue that binds individual sentences, paragraphs, and sections into a cohesive and comprehensible whole, making it an indispensable element for conveying information, presenting arguments, and telling compelling stories in written form.

Definition Of Cohesion

Cohesion refers to the quality of a written text that makes it clear, organized, and logically connected. It is achieved through various linguistic devices such as transitional words, pronoun references, repetition, and logical sequencing.

Cohesion ensures that the ideas within a text flow smoothly and are linked together, making the text easier to understand and follow. In essence, cohesion contributes to the overall coherence of a written piece, ensuring that it is cohesive and well-structured.

Relationship Between Coherence And Cohesion

The relationship between coherence and cohesion in writing is a close and interdependent one. Coherence and cohesion work together to create well-structured and easily understandable texts.

Coherence primarily deals with the overall clarity and logical flow of ideas in a piece of writing. It involves the organization of content in a way that makes sense to the reader. Coherent writing maintains a clear and consistent focus on the topic, using logical transitions between sentences and paragraphs.

On the other hand, cohesion focuses on the specific linguistic devices and techniques used to connect different parts of a text. These devices include transitional words (e.g., “therefore,” “however”), pronoun references (e.g., “it,” “they”), repetition of key terms, and logical sequencing of ideas. Cohesion ensures that the sentences within a text are linked together smoothly, enhancing the readability and comprehension of the content.

In essence, cohesion serves as a tool to achieve coherence. When a writer effectively employs cohesive elements in their writing, it enhances the overall coherence of the text. Without cohesion, even well-structured ideas may appear disjointed or confusing to the reader. Therefore, coherence and cohesion are complementary aspects of effective writing, working hand in hand to convey ideas clearly and persuasively.

Types Of Cohesion

Cohesion plays a vital role in the coherence and flow of your writing. In this section, we will explore different types of cohesion, each contributing to the overall clarity and structure of your text.

Grammatical Cohesion

Grammatical cohesion focuses on the grammatical and structural elements within a text that contribute to its coherence. It involves using linguistic devices, like pronouns and sentence structure, to create clear relationships between ideas and sentences. This type of cohesion ensures smooth writing flow and aids readers in understanding connections between different parts of your text.

For instance, pronouns like “it,” “they,” and “this” refer back to previously mentioned nouns, preventing repetition. Sentence structure, including parallelism and transitional words, also plays a crucial role in achieving grammatical cohesion. It ensures consistent presentation of similar ideas and guides readers through your writing.

Reiterative Cohesion

Reiterative cohesion involves the repetition of words, phrases, or ideas within a text to reinforce key concepts and enhance clarity. This type of cohesion is particularly useful when you want to emphasize specific points or themes throughout your writing.

By restating essential elements, you create a sense of continuity and remind readers of the central message. However, it’s crucial to use reiteration judiciously to avoid redundancy and monotony.

Lexical/Semantic/Logical Cohesion

Lexical, semantic, or logical cohesion ensures meaningful connections in your text. Writers use techniques like synonyms, antonyms, and precise vocabulary to clarify complex ideas. It also maintains consistency in word meanings and logical progression, enhancing clarity and engagement.

Referential Cohesion

Referential cohesion involves linking ideas and information within a text. It’s achieved by using pronouns, demonstratives, or repetition to connect concepts. This cohesion helps readers follow the flow of the text and understand the relationships between different parts of the content.

Textual Or Interpersonal Cohesion

Textual or interpersonal cohesion focuses on how language is used to engage and communicate with the reader. It involves strategies such as addressing the reader directly, using inclusive language, and creating a sense of connection. This type of cohesion aims to make the text more relatable and interactive, enhancing the reader’s overall experience.

Tips For Using Coherence And Cohesion In Writing

When it comes to effective writing, coherence, and cohesion play a pivotal role in shaping the clarity and flow of your text. In this section, we’ll delve into practical tips for harnessing these vital elements to create well-structured and engaging content.

Develop Topic Sentences And Themes

Effective writing hinges on clear topic sentences and well-defined themes. These elements act as your text’s structural framework, ensuring both you and your readers follow a logical path through your content.

- Identify Core Ideas: Before you begin writing, pinpoint the central concepts or themes you want to convey. These serve as the core messages or arguments you’ll explore.

- Craft Concise Topic Sentences: Start each paragraph with a concise topic sentence that introduces its main idea. Think of these sentences as guideposts, signaling what’s ahead and providing clarity.

- Establish a Strong Base: Topic sentences and themes set your text’s direction and purpose. Without them, your writing can seem disjointed and confusing.

- Map Out Content: Effective topic sentences not only introduce a paragraph’s main point but also outline the supporting details. They create a roadmap, making your content structure clear.

- Improve Readability: Strong topic sentences and themes make your writing more accessible. They help readers grasp ideas quickly and navigate your text effortlessly, making your message compelling.

By integrating these techniques into your writing, you enhance your content’s coherence and cohesion, making it more engaging and persuasive. Crafting clear topic sentences and themes provides a foundation for your ideas to shine and resonate with your audience.

Make Connections Between Ideas And Sentences

Writing with coherence involves crafting a seamless path for your readers. This means ensuring that your ideas flow logically and cohesively from one to the next. To achieve this, use transition words and phrases like “however,” “therefore,” “in contrast,” and “moreover” to signal relationships between ideas.

Avoid abrupt shifts, as these can confuse readers and disrupt the flow. By making these connections, you not only maintain coherence but also enhance clarity and engagement, providing your audience with a richer and more enjoyable reading experience.

Utilize Transition Words To Enhance Understanding

Transition words are the glue that holds your writing together, creating a bridge between sentences and paragraphs. These words and phrases, such as “however,” “in addition,” “consequently,” and “for instance,” help guide readers through your text, making it easier for them to follow your line of thought.

When used effectively, transition words create a smooth and logical flow, enhancing the coherence of your writing. They clarify relationships between ideas, signal shifts in focus, and add depth to your arguments. By incorporating these linguistic tools into your writing, you not only boost comprehension but also elevate the overall quality of your work.

Use Repetition When Appropriate

Repetition in writing, when used judiciously, can be a powerful tool to reinforce key ideas, engage readers, and create memorable content. By repeating certain words, phrases, or concepts, you can emphasize their significance and drive your point home effectively.

However, the key is to use repetition purposefully and sparingly, ensuring that it aligns with your writing’s objectives. Whether it’s repeating a central theme, a thought-provoking question, or a striking metaphor, strategic repetition can enhance the cohesiveness and impact of your writing, leaving a lasting impression on your audience.

Checklist For Essay Coherence And Cohesiveness

When crafting an essay, ensuring that it has both coherence and cohesion is paramount to engage your audience and effectively convey your message. Follow this checklist to enhance the quality of your writing:

- Clear Thesis Statement: Begin with a concise and well-defined thesis statement that sets the tone for your essay.

- Logical Flow: Organize your ideas logically, ensuring each paragraph connects seamlessly to the next.

- Transitions: Use transitional words and phrases like “however,” “therefore,” and “in addition” to guide your reader through your essay.

- Topic Sentences: Start each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that previews the content to follow.

- Consistent Point of View: Maintain a consistent perspective (first, second, or third person) throughout your essay.

- Repetition with Purpose: Use repetition thoughtfully to reinforce key points or themes.

- Parallel Structure: Structure sentences and lists in a parallel format for clarity.

- Pronoun Clarity: Ensure pronouns have clear antecedents to avoid confusion.

- Sentence Variety: Vary your sentence structure for rhythm and engagement.

- Proofreading: Thoroughly proofread your essay for grammar, punctuation, and spelling errors.

By implementing these strategies, you can create essays that are not only coherent and cohesive but also compelling and impactful.

High Impact And Greater Visibility For Your Work

Mind the Graph can bring high impact and greater visibility to your work by transforming your research findings into engaging visuals that are easily understood and shared. This can help you reach a broader audience, foster collaboration, and ultimately enhance the recognition and influence of your scientific contributions.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

Unlock Your Creativity

Create infographics, presentations and other scientifically-accurate designs without hassle — absolutely free for 7 days!

About Jessica Abbadia

Jessica Abbadia is a lawyer that has been working in Digital Marketing since 2020, improving organic performance for apps and websites in various regions through ASO and SEO. Currently developing scientific and intellectual knowledge for the community's benefit. Jessica is an animal rights activist who enjoys reading and drinking strong coffee.

Content tags

Writing Resources: Developing Cohesion

Cohesion is a characteristic of a successful essay when it flows as a united whole ; meaning, there is unity and connectedness between all of the parts. Cohesion is a writing issue at a macro and micro level. At a macro-level, cohesion is the way a paper uses a thesis sentence, topic sentences, and transitions across paragraphs to help unify and focus a paper. On a micro-level, cohesion happens within the paragraph unit between sentences; when each sentence links back to the previous sentence and looks ahead to the next, there is cohesion across sentences. Cohesion is an important aspect of writing because it helps readers to follow the writer’s thinking.

Misconceptions & Stumbling Blocks

Many writers believe that you should avoid repetition at all costs. It’s true that strong writing tends to not feel repetitive in terms of style and word choice; however, some repetition is necessary in order to build an essay and even paragraphs that build on each other and develop logically. A pro tip when you’re drafting an essay would be to build in a lot of repetition and then as you revise, go through your essay and look for ways you can better develop your ideas by paraphrasing your argument and using appropriate synonyms.

Building Cohesion

Essay focus: macro cohesion.

Locate & read your thesis sentence and the first and last sentence of each paragraph. You might even highlight them and/or use a separate piece of paper to make note of the key ideas and subjects in each (that is, making a reverse outline while you’re reading).

- How do these sentences relate?

- How can you use the language of the thesis statement again in topic sentences to reconnect to the main argument?

- Does each paragraph clearly link back to the thesis? Is it clear how each paragraph adds to, extends, or complicates the thesis?

- Repetition of key terms and ideas (especially those that are key to the argument)

- Repetition of central arguments; ideally, more than repeating your argument, it evolves and develops as it encounters new supporting or conflicting evidence.

- Appropriate synonyms. Synonyms as well as restating (paraphrasing) main ideas and arguments both helps you to explain and develop the argument and to build cohesion in your essay.

Paragraph Focus: Micro Cohesion

For one paragraph, underline the subject and verb of each sentence.

- Does the paragraph have a consistent & narrow focus?

- Will readers see the connection between the sentences?

- Imagine that the there is a title for this paragraph: what would it be and how would it relate to the underlined words?

- Repetition of the central topic and a clear understanding of how the evidence in this paragraph pushes forward or complicates that idea.

- Variations on the topic

- Avoid unclear pronouns (e.g., it, this, these, etc.). Rather than using pronouns, try to state a clear and specific subject for each sentence. This is an opportunity to develop your meaning through naming your topic in different ways.

- Synonyms for key terms and ideas that help you to say your point in slightly new ways that also push forward your ideas.

Sentence to Sentence: Micro Cohesion

Looking at one paragraph, try to name what each sentence is doing to the previous: is it adding further explanation? Is it complicating the topic? Is it providing an example? Is it offering a counter-perspective? Sentences that build off of each other have movement that is intentional and purposeful; that is, the writer knows the purpose of each sentence and the work that each sentence accomplishes for the paragraph.

- Transition words (look up a chart) to link sentence and to more clearly name what you’re doing in each sentence (e.g., again, likewise, indeed, therefore, however, additionally, etc.)

- Precise verbs to help emphasize what the writer is doing and saying (if you’re working with a source/text) or what you’re doing and saying.

- Again, clear and precise subjects that continue to name your focus in each sentence.

A Link to a PDF Handout of this Writing Guide

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.6: Coherent Paragraphs

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 15715

Get it down. Take chances. It may be bad, but it’s the only way you can do anything really good. (William Faulkner)

You wouldn’t hand in a lot of sticks and boards bunched together and call it a table. It’s no better to hand in a detached bundle of statements starting nowhere in particular, training along and then fading out – and call it a theme. (Dorothy Canfield Fisher)

When you think about it, there’s no contradiction in the advice of these two American writers. You should respond with genuine feeling and without inhibition to what stimulates you – in our case, a set of texts. But feeling isn’t enough. When Gustave Flaubert asked “Has a drinking song ever been written by a drunken man?” he meant a coherent song. Between “getting it down” and “handing it in” good writers show respect for their readers by organizing their material into recognizable patterns. An important benefit of this is that by distancing yourself from your ideas and putting them in order for your reader, you are forced to shape your own nebulous feelings into clear thoughts.

This brings us to the well-known (but apparently not well enough known) paragraph: the basic unit of composition. The traditional and still useful rule that a paragraph must have unity, coherence, and emphasis only means that it must make sense, that the sentences should fit together smoothly, and that not all the sentences function in the same way.

When you see that its purpose is to support your thesis by developing and connecting your ideas meaningfully, then paragraph structure should appeal to your common sense. As a point of emphasis a topic sentence – whether you choose to put it at the beginning, middle, or end – allows you to control your writing and guide your reader by expressing the main idea of the paragraph. Remember, you’re not writing a mystery novel. There will be relatively few instances in this type of essay when you’ll want to surprise your reader.

Must every paragraph have a topic sentence? Not necessarily: if the main idea is obvious, then a topic sentence may be omitted. But even if it is only implied by your paragraph, you and your reader should be able to state easily the main idea . Whether explicit or implicit, the topic sentence of each of your paragraphs should come out of your thesis statement and lead to your conclusion. Like the paragraph, the whole essay should have unity, coherence, and emphasis. Try this: next time you read an essay, underline only the topic sentences of each paragraph; then reread only what you’ve underlined. In many cases you’ll see that the underlined sentences make up a coherent paragraph all by themselves (this is an easy way to write an abstract, incidentally). That’s because most topic sentences are more specific than the thesis statement that generates them, but still more general than the supporting sentences in the paragraphs that illustrate them. Thus they are transitions between the writer’s promise to the reader and the keeping of that promise.

The ideal gas law is easy to remember and apply in solving problems, as long as you get the proper values a

Examples: Opening Paragraphs

From a student essay discussing Kafka’s The Metamorphosis :

When Nietzsche declared that “God is dead,” he did so with an air of optimism. No longer could man be led about on the tight leash of religion; a man liberated could strive for the status of Overman. But what happens if a man refuses to let go of his “dead” God and remains too fearful to evolve into an Overman? Rejecting the concept of the Christian God means renouncing the scapegoat for the sins of man and accepting responsibility for one’s own actions. In The Metamorphosis Gregor Samsa plays the god-like role of financial provider for his family. However, when his transformation renders him useless in this role, the rest of Samsa’s family undergoes a change of its own: Kafka uses the metamorphoses of both Gregor and his family to illustrate a modern crisis.

Some comments on the structure: Two provocative introductory sentences, then a transition question and a response that presents the central idea of the essay. Next, introduction of the text and characters under discussion. Finally, the topic sentence of the paragraph, which, as the thesis statement, promises an interpretation. A paragraph such as this engages the reader’s interest right away and makes the reader look forward to the rest of the essay.

From a student essay on the question, “What Do Historians of Childhood Do?”

In his 1982 book The Disappearance of Childhood , Neil Postman argues that the concept of childhood is a recent invention of literate society, enabled by the invention of moveable-type printing. Postman says as a result of television, literate adulthood and preliterate childhood are both vanishing. While Postman’s indictment of TV-culture is provocative, he ignores race, class, ideology, and economic circumstance as factors in the experience of both children and adults. Worse, he ignores history, making sweeping generalizations such as the claim that the pre-modern Greeks had no concept of children. These claims are contradicted by the appearance of children in classical Greek literature and in the Christian Gospels, written in Greek, which admonish their readers to “be as children.” A more useful and much more interesting observation might be that the idea of childhood and the experience of young people has changed significantly since ancient times, and continues to change.

Some comments on the structure: Like the previous example, this essay begins with a statement from a text (this time with a paraphrase rather than a quotation) and builds towards a thesis statement. In this case the build-up, where the writer disagrees with one of the class texts, is stronger than the thesis. The writer has not stated exactly what he will argue, aside from saying he finds at least some of the ideas of childhood advanced in the course materials unsatisfactory. Keeping the reader in suspense may add to the interest of the essay, but in a short paper it might also waste valuable time and leave the reader unsure whether the writer has really thought things through.

From an essay on Crime and Punishment :

“Freedom depends upon the real…It is as impossible to exercise freedom in an unreal world as it is to jump while you are falling” (Colin Wilson, The Outsider, p. 39). Even without God, modern man is still tempted to create unreal worlds. In Feodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment Raskolnikov conceives the fantastic theory of the “overman.” After committing murder in an attempt to satisfy his theory, Raskolnikov falls into a delirious, death-like state; then, Lazarus-like, he is raised from the “dead.” His “resurrection” is not, as some critics suggest, a consequence of his love for Sonya and Sonya’s God. Rather, his salvation results from the freedom he gains when he chooses to live without illusions.

Comments: Once more, a stimulating opening. Between the first and last sentences, which frame the paragraph (the last one, as well as being the thesis sentence, is the specific application of the general first sentence), the writer makes her transition to the central idea and introduces the text and character she wishes to discuss. The reader is given enough information to know what to expect. It promises to be an interesting essay.