How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications. If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

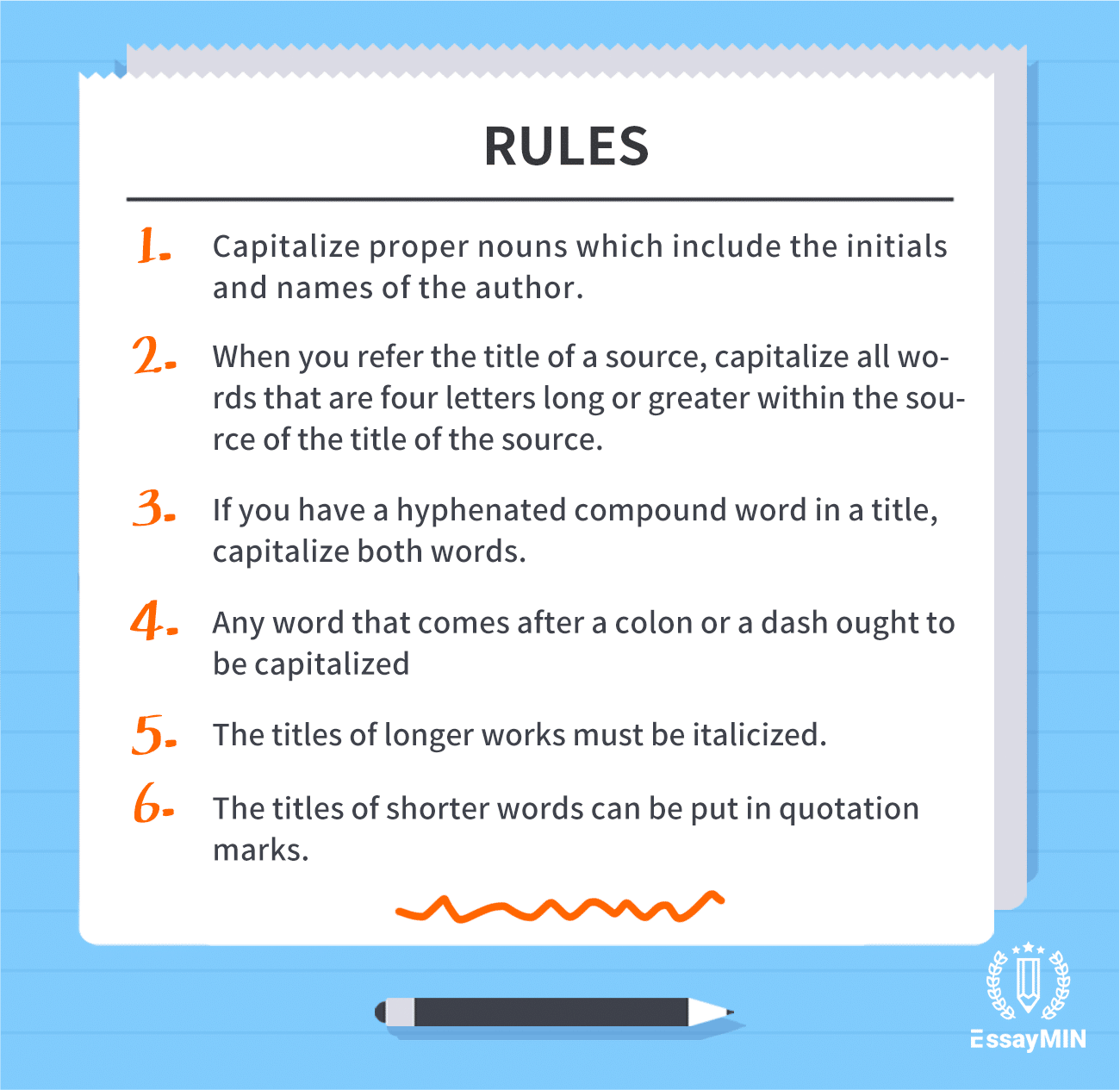

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Research Paper Guide

Research Paper Example

Research Paper Examples - Free Sample Papers for Different Formats!

People also read

Research Paper Writing - A Step by Step Guide

Guide to Creating Effective Research Paper Outline

Interesting Research Paper Topics for 2024

Research Proposal Writing - A Step-by-Step Guide

How to Start a Research Paper - 7 Easy Steps

How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper - A Step by Step Guide

Writing a Literature Review For a Research Paper - A Comprehensive Guide

Qualitative Research - Methods, Types, and Examples

8 Types of Qualitative Research - Overview & Examples

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research - Learning the Basics

200+ Engaging Psychology Research Paper Topics for Students in 2024

Learn How to Write a Hypothesis in a Research Paper: Examples and Tips!

20+ Types of Research With Examples - A Detailed Guide

Understanding Quantitative Research - Types & Data Collection Techniques

230+ Sociology Research Topics & Ideas for Students

How to Cite a Research Paper - A Complete Guide

Excellent History Research Paper Topics- 300+ Ideas

A Guide on Writing the Method Section of a Research Paper - Examples & Tips

How To Write an Introduction Paragraph For a Research Paper: Learn with Examples

Crafting a Winning Research Paper Title: A Complete Guide

Writing a Research Paper Conclusion - Step-by-Step Guide

Writing a Thesis For a Research Paper - A Comprehensive Guide

How To Write A Discussion For A Research Paper | Examples & Tips

How To Write The Results Section of A Research Paper | Steps & Examples

Writing a Problem Statement for a Research Paper - A Comprehensive Guide

Finding Sources For a Research Paper: A Complete Guide

A Guide on How to Edit a Research Paper

200+ Ethical Research Paper Topics to Begin With (2024)

300+ Controversial Research Paper Topics & Ideas - 2024 Edition

150+ Argumentative Research Paper Topics For You - 2024

How to Write a Research Methodology for a Research Paper

Crafting a comprehensive research paper can be daunting. Understanding diverse citation styles and various subject areas presents a challenge for many.

Without clear examples, students often feel lost and overwhelmed, unsure of how to start or which style fits their subject.

Explore our collection of expertly written research paper examples. We’ve covered various citation styles and a diverse range of subjects.

So, read on!

- 1. Research Paper Example for Different Formats

- 2. Examples for Different Research Paper Parts

- 3. Research Paper Examples for Different Fields

- 4. Research Paper Example Outline

Research Paper Example for Different Formats

Following a specific formatting style is essential while writing a research paper . Knowing the conventions and guidelines for each format can help you in creating a perfect paper. Here we have gathered examples of research paper for most commonly applied citation styles :

Social Media and Social Media Marketing: A Literature Review

APA Research Paper Example

APA (American Psychological Association) style is commonly used in social sciences, psychology, and education. This format is recognized for its clear and concise writing, emphasis on proper citations, and orderly presentation of ideas.

Here are some research paper examples in APA style:

Research Paper Example APA 7th Edition

Research Paper Example MLA

MLA (Modern Language Association) style is frequently employed in humanities disciplines, including literature, languages, and cultural studies. An MLA research paper might explore literature analysis, linguistic studies, or historical research within the humanities.

Here is an example:

Found Voices: Carl Sagan

Research Paper Example Chicago

Chicago style is utilized in various fields like history, arts, and social sciences. Research papers in Chicago style could delve into historical events, artistic analyses, or social science inquiries.

Here is a research paper formatted in Chicago style:

Chicago Research Paper Sample

Research Paper Example Harvard

Harvard style is widely used in business, management, and some social sciences. Research papers in Harvard style might address business strategies, case studies, or social policies.

View this sample Harvard style paper here:

Harvard Research Paper Sample

Examples for Different Research Paper Parts

A research paper has different parts. Each part is important for the overall success of the paper. Chapters in a research paper must be written correctly, using a certain format and structure.

The following are examples of how different sections of the research paper can be written.

Research Proposal

The research proposal acts as a detailed plan or roadmap for your study, outlining the focus of your research and its significance. It's essential as it not only guides your research but also persuades others about the value of your study.

Example of Research Proposal

An abstract serves as a concise overview of your entire research paper. It provides a quick insight into the main elements of your study. It summarizes your research's purpose, methods, findings, and conclusions in a brief format.

Research Paper Example Abstract

Literature Review

A literature review summarizes the existing research on your study's topic, showcasing what has already been explored. This section adds credibility to your own research by analyzing and summarizing prior studies related to your topic.

Literature Review Research Paper Example

Methodology

The methodology section functions as a detailed explanation of how you conducted your research. This part covers the tools, techniques, and steps used to collect and analyze data for your study.

Methods Section of Research Paper Example

How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper

The conclusion summarizes your findings, their significance and the impact of your research. This section outlines the key takeaways and the broader implications of your study's results.

Research Paper Conclusion Example

Research Paper Examples for Different Fields

Research papers can be about any subject that needs a detailed study. The following examples show research papers for different subjects.

History Research Paper Sample

Preparing a history research paper involves investigating and presenting information about past events. This may include exploring perspectives, analyzing sources, and constructing a narrative that explains the significance of historical events.

View this history research paper sample:

Many Faces of Generalissimo Fransisco Franco

Sociology Research Paper Sample

In sociology research, statistics and data are harnessed to explore societal issues within a particular region or group. These findings are thoroughly analyzed to gain an understanding of the structure and dynamics present within these communities.

Here is a sample:

A Descriptive Statistical Analysis within the State of Virginia

Science Fair Research Paper Sample

A science research paper involves explaining a scientific experiment or project. It includes outlining the purpose, procedures, observations, and results of the experiment in a clear, logical manner.

Here are some examples:

Science Fair Paper Format

What Do I Need To Do For The Science Fair?

Psychology Research Paper Sample

Writing a psychology research paper involves studying human behavior and mental processes. This process includes conducting experiments, gathering data, and analyzing results to understand the human mind, emotions, and behavior.

Here is an example psychology paper:

The Effects of Food Deprivation on Concentration and Perseverance

Art History Research Paper Sample

Studying art history includes examining artworks, understanding their historical context, and learning about the artists. This helps analyze and interpret how art has evolved over various periods and regions.

Check out this sample paper analyzing European art and impacts:

European Art History: A Primer

Research Paper Example Outline

Before you plan on writing a well-researched paper, make a rough draft. An outline can be a great help when it comes to organizing vast amounts of research material for your paper.

Here is an outline of a research paper example:

Here is a downloadable sample of a standard research paper outline:

Research Paper Outline

Want to create the perfect outline for your paper? Check out this in-depth guide on creating a research paper outline for a structured paper!

Good Research Paper Examples for Students

Here are some more samples of research paper for students to learn from:

Fiscal Research Center - Action Plan

Qualitative Research Paper Example

Research Paper Example Introduction

How to Write a Research Paper Example

Research Paper Example for High School

Now that you have explored the research paper examples, you can start working on your research project. Hopefully, these examples will help you understand the writing process for a research paper.

If you're facing challenges with your writing requirements, you can hire our essay writing help online.

Our team is experienced in delivering perfectly formatted, 100% original research papers. So, whether you need help with a part of research or an entire paper, our experts are here to deliver.

So, why miss out? Place your ‘ write my research paper ’ request today and get a top-quality research paper!

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Nova Allison is a Digital Content Strategist with over eight years of experience. Nova has also worked as a technical and scientific writer. She is majorly involved in developing and reviewing online content plans that engage and resonate with audiences. Nova has a passion for writing that engages and informs her readers.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

How to Write a Comprehensive Review

What is a research paper or article worth? The answer to this depends on many factors. But the short answer is: if you’re conducting a comprehensive review, you’re essentially assessing an article’s worth.

Research is critical to the evolution of modern science. By writing a research article, you’re immortalizing that research so others may continue it and build on top of it for many years to come. However, there’s a risk of not being published without a comprehensive review.

This article teaches you everything you should know when preparing to write a review and how to write a comprehensive one.

What You Should Know When Preparing for a Review

A comprehensive review requires a well-structured presentation of arguments and a high level of in-depth analysis because, in an article, you deal with a lot of reading, comparing, and contrasting. You want to start by reading the article quickly to get an idea of the main points, check the structure, and ensure it meets the requirements.

Next, you’ll want to think about how effectively the author proved their main points and arguments. Pay close attention to the article’s methods and materials to ensure the author’s arguments are defensible and support their ideas. Conduct any necessary research to validate the author’s main points . To do this, you may use database searches like Google Scholar and PubMed (focus on publications that are three years old at most ).

Finally, you’ll want to read through the article again. Decide whether you will read the article from start to finish or by following these steps:

- Start by reading the title, introductory part, headings, subheadings, abstract, opening sentences, and the conclusion. The beginning and end of an article are where the author includes the main points and arguments, so you’ll get a good idea of the main points by reading these parts first

- Then read the entire article once again.

Regardless of your choice, take detailed notes on inconsistencies, points that require further clarification, unanswered questions, or major areas of concern while reading (you’ll use these later). Note how the article comes across to a reader and ensure you touch on the following points:

- Did the author stay on topic?

- Does the article state the issue(s), idea(s), and claim(s) right off the bat? And are they clear?

- What kind of support does the article provide? (a credible solution, case studies, illustrations, etc.)

- Are the sources legitimate and properly cited?

- Is the author contributing to knowledge advancement? Has the topic been approached before, or is the author responding to another author’s work?

Types of Review

It’s important to distinguish between different types of review because this determines how you’ll conduct your research to provide a top-notch review. Some reputable peer-reviewed journals include review articles, and they can even have a lot of citations and a high impact factor . Below are the different types of review articles.

Journal Article Review

This type of review outlines the strengths and weaknesses of a publication. You must demonstrate the article’s value through a thorough analysis and interpretation.

Research Article Review

Slightly different from a journal review, a research article review evaluates the research method and compares it to the article’s analysis and critique.

Scientific Article Review

This type of review involves the review of any article within the realm of science. Scientific publications may include more information on the background necessary to help you provide a more comprehensive review.

Now you’re ready to start writing! Start a review by including a title (declarative, descriptive, or interrogative). Before moving on to the intro of your review, cite and identify the article, and include:

- The article’s title

- The journal’s title (if applicable)

- Year of publication.

Having a definite structure is crucial if you want your review to be as comprehensive as possible; therefore, you can outline your review or use a paper review template to organize your notes coherently. In the intro, you want to start by touching on the main strengths and weaknesses and include:

- Introducing the research topic and why there’s a need for it within the respective community or organization

- Summarizing the main points and relevant facts of the article

- Highlighting the positives (is the question interesting or vital, are the author’s methods appropriate?)

- Methodological flaws

- Critiques of any present gaps in research, unanswered questions, contradictions, or issues pertinent to future studies

The body is the main part of your review and should include comparisons and thorough analysis. At this point, include any previous notes you took while preparing for the review. There isn’t a word limit to this part of the review, but you must include as much or as little detail as each article deserves, paying special attention to:

- Qualitative vs. quantitative approaches

- The article’s specific objective or purpose

- The conclusion and its importance

- Chronology.

For the conclusion, revisit your findings, critiques, and the article’s critical points while maintaining the focus established in the intro. Ensure the conclusion is short and to the point.

Post-Review

Now that your review is complete, check for errors, bad grammar, or awkwardly-phrased sentences. If your review is poorly written, it’ll be considered irrelevant, even if your ideas are qualitative.Remember to always be respectful of another author’s work . Refrain from writing a bad review, even if there are points that you disagree with or that anger or frustrate you. Instead, show examples of any errors or inconsistencies you find and politely suggest ideas about other aspects of the author’s research for their future works.

Orvium Makes it Simple For Reviewers

If writing a comprehensive review feels overwhelming at first, you may choose to look at other researchers’ or scholars’ article reviews. Or, better yet, consider using Orvium ! You can increase your interactions and engage with researchers and reviewers within your community and beyond. Orvium is the platform for all your publishing needs. You also have a chance to collaborate, showcase your profile, and track your impact on our platform . Want even more tips and tricks? Check out our blog .

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox.

Now check your inbox and click the link to confirm your subscription.

Please enter a valid email address

Oops! There was an error sending the email, please try later.

Roberto Rabasco

+10 years’ experience working for Deutsche Telekom, Just Eat or Asos. Leading, designing and developing high-availability software solutions, he built his own software house in '16

Recommended for you

How to Write a Research Funding Application | Orvium

Increasing Representation and Diversity in Research with Open Science | Orvium

Your Guide to Open Access Week 2023

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Research Paper Structure: A Comprehensive Guide

Table of Contents

Writing a research paper is a daunting task, but understanding its structure can make the process more manageable and lead to a well-organized, coherent paper. This article provides a step-by-step approach to crafting a research paper, ensuring your work is not only informative but also structured for maximum impact.

Introduction

In any form of written communication, content structure plays a vital role in facilitating understanding. A well-structured research paper provides a framework that guides readers through the content, ensuring they grasp the main points efficiently. Without a clear structure, readers may become lost or confused, leading to a loss of interest and a failure to comprehend the intended message.

When it comes to research papers, structure is particularly important due to the complexity of the subject matter. Research papers often involve presenting and analyzing large amounts of data, theories, and arguments. Without a well-defined structure, readers may struggle to navigate through this information overload, resulting in a fragmented understanding of the topic.

How Structure Enhances Clarity and Coherence

A well-structured research paper not only helps readers follow the flow of ideas but also enhances the clarity and coherence of the content. By organizing information into sections, paragraphs, and sentences, researchers can present their thoughts logically and systematically. This logical organization allows readers to easily connect ideas, resulting in a more coherent and engaging reading experience.

One way in which structure enhances clarity is by providing a clear roadmap for readers to follow. By dividing the research paper into sections and subsections, researchers can guide readers through the different aspects of the topic. This allows readers to anticipate the flow of information and mentally prepare themselves for the upcoming content.

In addition, a well-structured research paper ensures that each paragraph serves a specific purpose and contributes to the overall argument or analysis. By clearly defining the main idea of each paragraph and providing supporting evidence or examples, researchers can avoid confusion and ensure that their points are effectively communicated.

Moreover, a structured research paper helps researchers maintain a consistent focus throughout their writing. By organizing their thoughts and ideas, researchers can ensure that they stay on track and avoid going off on tangents. This not only improves the clarity of the paper but also helps maintain the reader's interest and engagement.

Components of a Research Paper Structure

Title and abstract: the initial impression.

The title and abstract are the first elements readers encounter when accessing a research paper. The title should be concise, informative, and capture the essence of the study. For example, a title like "Exploring the Impact of Climate Change on Biodiversity in Tropical Rainforests" immediately conveys the subject matter and scope of the research. The abstract, on the other hand, provides a brief overview of the research problem, methodology, and findings, enticing readers to delve further into the paper. In a well-crafted abstract, researchers may highlight key results or implications of the study, giving readers a glimpse into the value of the research.

Introduction: Setting the Stage

The introduction serves as an invitation for readers to engage with the research paper. It should provide background information on the topic, highlight the research problem, and present the research question or thesis statement. By establishing the context and relevance of the study, the introduction piques readers' interest and prepares them for the content to follow. For instance, in a study on the impact of social media on mental health, the introduction may discuss the rise of social media platforms and the growing concerns about its effects on individuals' well-being. This contextual information helps readers understand the significance of the research and why it is worth exploring further.

Furthermore, the introduction may also outline the objectives of the study, stating what the researchers aim to achieve through their research. This helps readers understand the purpose and scope of the study, setting clear expectations for what they can expect to learn from the paper.

Literature Review: Building the Foundation

The literature review is a critical component of a research paper, as it demonstrates the researcher's understanding of existing knowledge and provides a foundation for the study. It involves reviewing and analyzing relevant scholarly articles, books, and other sources to identify gaps in research and establish the need for the current study. In a comprehensive literature review, researchers may summarize key findings from previous studies, identify areas of disagreement or controversy, and highlight the limitations of existing research.

Moreover, the literature review may also discuss theoretical frameworks or conceptual models that have been used in previous studies. By examining these frameworks, researchers can identify the theoretical underpinnings of their study and explain how their research fits within the broader academic discourse. This not only adds depth to the research paper but also helps readers understand the theoretical context in which the study is situated.

Methodology: Detailing the Process

The research design, data collection methods, and analysis techniques used in the study are described in the methodology section. It should be presented clearly and concisely, allowing readers to understand how the research was conducted and evaluated. A well-described methodology ensures the study's reliability and allows other researchers to replicate or build upon the findings.

Within the methodology section, researchers may provide a detailed description of the study population or sample, explaining how participants were selected and why they were chosen. This helps readers understand the generalizability of the findings and the extent to which they can be applied to a broader population.

In addition, researchers may also discuss any ethical considerations that were taken into account during the study. This could include obtaining informed consent from participants, ensuring confidentiality and anonymity, and following ethical guidelines set by relevant professional organizations. By addressing these ethical concerns, researchers demonstrate their commitment to conducting research in an ethical and responsible manner.

Results: Presenting the Findings

The results section represents the study findings. Researchers should organize their results in a logical manner, using tables, graphs, and descriptive statistics to support their conclusions. The results should be presented objectively, without interpretation or analysis. For instance, for a study on the effectiveness of a new drug in treating a specific medical condition, researchers may present the percentage of patients who experienced positive outcomes, along with any statistical significance associated with the results.

In addition to presenting the main findings, researchers may also include supplementary data or sub-analyses that provide further insights into the research question. This could include subgroup analyses, sensitivity analyses, or additional statistical tests that help explore the robustness of the findings.

Discussion: Interpreting the Results

In the discussion section, researchers analyze and interpret the results in light of the research question or thesis statement. This is an opportunity to explore the implications of the findings, compare them with existing literature, and offer insights into the broader significance of the study. The discussion should be supported by evidence and it is advised to avoid speculation.

Researchers may also discuss the limitations of their study, acknowledging any potential biases or confounding factors that may have influenced the results. By openly addressing these limitations, researchers demonstrate their commitment to transparency and scientific rigor.

Conclusion: Wrapping It Up

The conclusion provides a concise summary of the research paper, restating the main findings and their implications. It should also reflect on the significance of the study and suggest potential avenues for future research. A well-written conclusion leaves a lasting impression on readers, highlighting the importance of the research and its potential impact. By summarizing the key takeaways from the study, researchers ensure that readers walk away with a clear understanding of the research's contribution to the field.

Tips for Organizing Your Research Paper

Starting with a strong thesis statement.

A strong and clear thesis statement serves as the backbone of your research paper. It provides focus and direction, guiding the organization of ideas and arguments throughout the paper. Take the time to craft a well-defined thesis statement that encapsulates the core message of your research.

Creating an Outline: The Blueprint of Your Paper

An outline acts as a blueprint for your research paper, ensuring a logical flow of ideas and preventing disorganization. Divide your paper into sections and subsections, noting the main points and supporting arguments for each. This will help you maintain coherence and clarity throughout the writing process.

Balancing Depth and Breadth in Your Paper

When organizing your research paper, strike a balance between delving deeply into specific points and providing a broader overview. While depth is important for thorough analysis, too much detail can overwhelm readers. Consider your target audience and their level of familiarity with the topic to determine the appropriate level of depth and breadth for your paper.

By understanding the importance of research paper structure and implementing effective organizational strategies, researchers can ensure their work is accessible, engaging, and influential. A well-structured research paper not only communicates ideas clearly but also enhances the overall impact of the study. With careful planning and attention to detail, researchers can master the art of structuring their research papers, making them a valuable contribution to their field of study.

You might also like

Introducing SciSpace’s Citation Booster To Increase Research Visibility

AI for Meta-Analysis — A Comprehensive Guide

How To Write An Argumentative Essay

How To Write A Research Paper

Research Paper Example

Research Paper Example - Examples for Different Formats

Published on: Jun 12, 2021

Last updated on: Feb 6, 2024

People also read

How to Write a Research Paper Step by Step

How to Write a Proposal For a Research Paper in 10 Steps

A Comprehensive Guide to Creating a Research Paper Outline

Types of Research - Methodologies and Characteristics

300+ Engaging Research Paper Topics to Get You Started

Interesting Psychology Research Topics & Ideas

Qualitative Research - Types, Methods & Examples

Understanding Quantitative Research - Definition, Types, Examples, And More

How To Start A Research Paper - Steps With Examples

How to Write an Abstract That Captivates Your Readers

How To Write a Literature Review for a Research Paper | Steps & Examples

Types of Qualitative Research Methods - An Overview

Understanding Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research - A Complete Guide

How to Cite a Research Paper in Different Citation Styles

Easy Sociology Research Topics for Your Next Project

200+ Outstanding History Research Paper Topics With Expert Tips

How To Write a Hypothesis in a Research Paper | Steps & Examples

How to Write an Introduction for a Research Paper - A Step-by-Step Guide

How to Write a Good Research Paper Title

How to Write a Conclusion for a Research Paper in 3 Simple Steps

How to Write an Abstract For a Research Paper with Examples

How To Write a Thesis For a Research Paper Step by Step

How to Write a Discussion For a Research Paper | Objectives, Steps & Examples

How to Write the Results Section of a Research Paper - Structure and Tips

How to Write a Problem Statement for a Research Paper in 6 Steps

How To Write The Methods Section of a Research Paper Step-by-Step

How to Find Sources For a Research Paper | A Guide

Share this article

Writing a research paper is the most challenging task in a student's academic life. researchers face similar writing process hardships, whether the research paper is to be written for graduate or masters.

A research paper is a writing type in which a detailed analysis, interpretation, and evaluation are made on the topic. It requires not only time but also effort and skills to be drafted correctly.

If you are working on your research paper for the first time, here is a collection of examples that you will need to understand the paper’s format and how its different parts are drafted. Continue reading the article to get free research paper examples.

On This Page On This Page -->

Research Paper Example for Different Formats

A research paper typically consists of several key parts, including an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, and annotated bibliography .

When writing a research paper (whether quantitative research or qualitative research ), it is essential to know which format to use to structure your content. Depending on the requirements of the institution, there are mainly four format styles in which a writer drafts a research paper:

Letâs look into each format in detail to understand the fundamental differences and similarities.

Research Paper Example APA

If your instructor asks you to provide a research paper in an APA format, go through the example given below and understand the basic structure. Make sure to follow the format throughout the paper.

APA Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Research Paper Example MLA

Another widespread research paper format is MLA. A few institutes require this format style as well for your research paper. Look at the example provided of this format style to learn the basics.

MLA Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Research Paper Example Chicago

Unlike MLA and APA styles, Chicago is not very common. Very few institutions require this formatting style research paper, but it is essential to learn it. Look at the example given below to understand the formatting of the content and citations in the research paper.

Chicago Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Research Paper Example Harvard

Learn how a research paper through Harvard formatting style is written through this example. Carefully examine how the cover page and other pages are structured.

Harvard Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Examples for Different Research Paper Parts

A research paper is based on different parts. Each part plays a significant role in the overall success of the paper. So each chapter of the paper must be drafted correctly according to a format and structure.

Below are examples of how different sections of the research paper are drafted.

Research Proposal Example

A research proposal is a plan that describes what you will investigate, its significance, and how you will conduct the study.

Research Proposal Sample (PDF)

Abstract Research Paper Example

An abstract is an executive summary of the research paper that includes the purpose of the research, the design of the study, and significant research findings.

It is a small section that is based on a few paragraphs. Following is an example of the abstract to help you draft yours professionally.

Abstract Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Literature Review Research Paper Example

A literature review in a research paper is a comprehensive summary of the previous research on your topic. It studies sources like books, articles, journals, and papers on the relevant research problem to form the basis of the new research.

Writing this section of the research paper perfectly is as important as any part of it.

Literature Review in Research Sample (PDF)

Methods Section of Research Paper Example

The method section comes after the introduction of the research paper that presents the process of collecting data. Basically, in this section, a researcher presents the details of how your research was conducted.

Methods Section in Research Sample (PDF)

Research Paper Conclusion Example

The conclusion is the last part of your research paper that sums up the writerâs discussion for the audience and leaves an impression. This is how it should be drafted:

Research Paper Conclusion Sample (PDF)

Research Paper Examples for Different Fields

The research papers are not limited to a particular field. They can be written for any discipline or subject that needs a detailed study.

In the following section, various research paper examples are given to show how they are drafted for different subjects.

Science Research Paper Example

Are you a science student that has to conduct research? Here is an example for you to draft a compelling research paper for the field of science.

Science Research Paper Sample (PDF)

History Research Paper Example

Conducting research and drafting a paper is not only bound to science subjects. Other subjects like history and arts require a research paper to be written as well. Observe how research papers related to history are drafted.

History Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Psychology Research Paper Example

If you are a psychology student, look into the example provided in the research paper to help you draft yours professionally.

Psychology Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Research Paper Example for Different Levels

Writing a research paper is based on a list of elements. If the writer is not aware of the basic elements, the process of writing the paper will become daunting. Start writing your research paper taking the following steps:

- Choose a topic

- Form a strong thesis statement

- Conduct research

- Develop a research paper outline

Once you have a plan in your hand, the actual writing procedure will become a piece of cake for you.

No matter which level you are writing a research paper for, it has to be well structured and written to guarantee you better grades.

If you are a college or a high school student, the examples in the following section will be of great help.

Research Paper Outline (PDF)

Research Paper Example for College

Pay attention to the research paper example provided below. If you are a college student, this sample will help you understand how a winning paper is written.

College Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Research Paper Example for High School

Expert writers of CollegeEssay.org have provided an excellent example of a research paper for high school students. If you are struggling to draft an exceptional paper, go through the example provided.

High School Research Paper Sample (PDF)

Examples are essential when it comes to academic assignments. If you are a student and aim to achieve good grades in your assignments, it is suggested to get help from CollegeEssay.org .

We are the best writing company that delivers essay help for students by providing free samples and writing assistance.

Professional writers have your back, whether you are looking for guidance in writing a lab report, college essay, or research paper.

Simply hire a writer by placing your order at the most reasonable price. You can also take advantage of our essay writer to enhance your writing skills.

Nova A. (Literature, Marketing)

As a Digital Content Strategist, Nova Allison has eight years of experience in writing both technical and scientific content. With a focus on developing online content plans that engage audiences, Nova strives to write pieces that are not only informative but captivating as well.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Legal & Policies

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Terms of Use

- Refunds & Cancellations

- Our Writers

- Success Stories

- Our Guarantees

- Affiliate Program

- Referral Program

- AI Essay Writer

Disclaimer: All client orders are completed by our team of highly qualified human writers. The essays and papers provided by us are not to be used for submission but rather as learning models only.

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

The discussion section contains the results and outcomes of a study. An effective discussion informs readers what can be learned from your experiment and provides context for the results.

What makes an effective discussion?

When you’re ready to write your discussion, you’ve already introduced the purpose of your study and provided an in-depth description of the methodology. The discussion informs readers about the larger implications of your study based on the results. Highlighting these implications while not overstating the findings can be challenging, especially when you’re submitting to a journal that selects articles based on novelty or potential impact. Regardless of what journal you are submitting to, the discussion section always serves the same purpose: concluding what your study results actually mean.

A successful discussion section puts your findings in context. It should include:

- the results of your research,

- a discussion of related research, and

- a comparison between your results and initial hypothesis.

Tip: Not all journals share the same naming conventions.

You can apply the advice in this article to the conclusion, results or discussion sections of your manuscript.

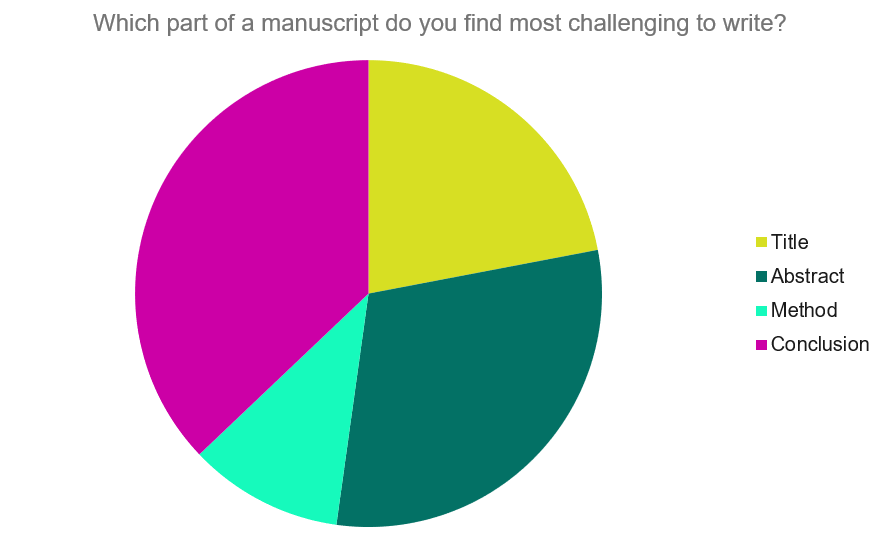

Our Early Career Researcher community tells us that the conclusion is often considered the most difficult aspect of a manuscript to write. To help, this guide provides questions to ask yourself, a basic structure to model your discussion off of and examples from published manuscripts.

Questions to ask yourself:

- Was my hypothesis correct?

- If my hypothesis is partially correct or entirely different, what can be learned from the results?

- How do the conclusions reshape or add onto the existing knowledge in the field? What does previous research say about the topic?

- Why are the results important or relevant to your audience? Do they add further evidence to a scientific consensus or disprove prior studies?

- How can future research build on these observations? What are the key experiments that must be done?

- What is the “take-home” message you want your reader to leave with?

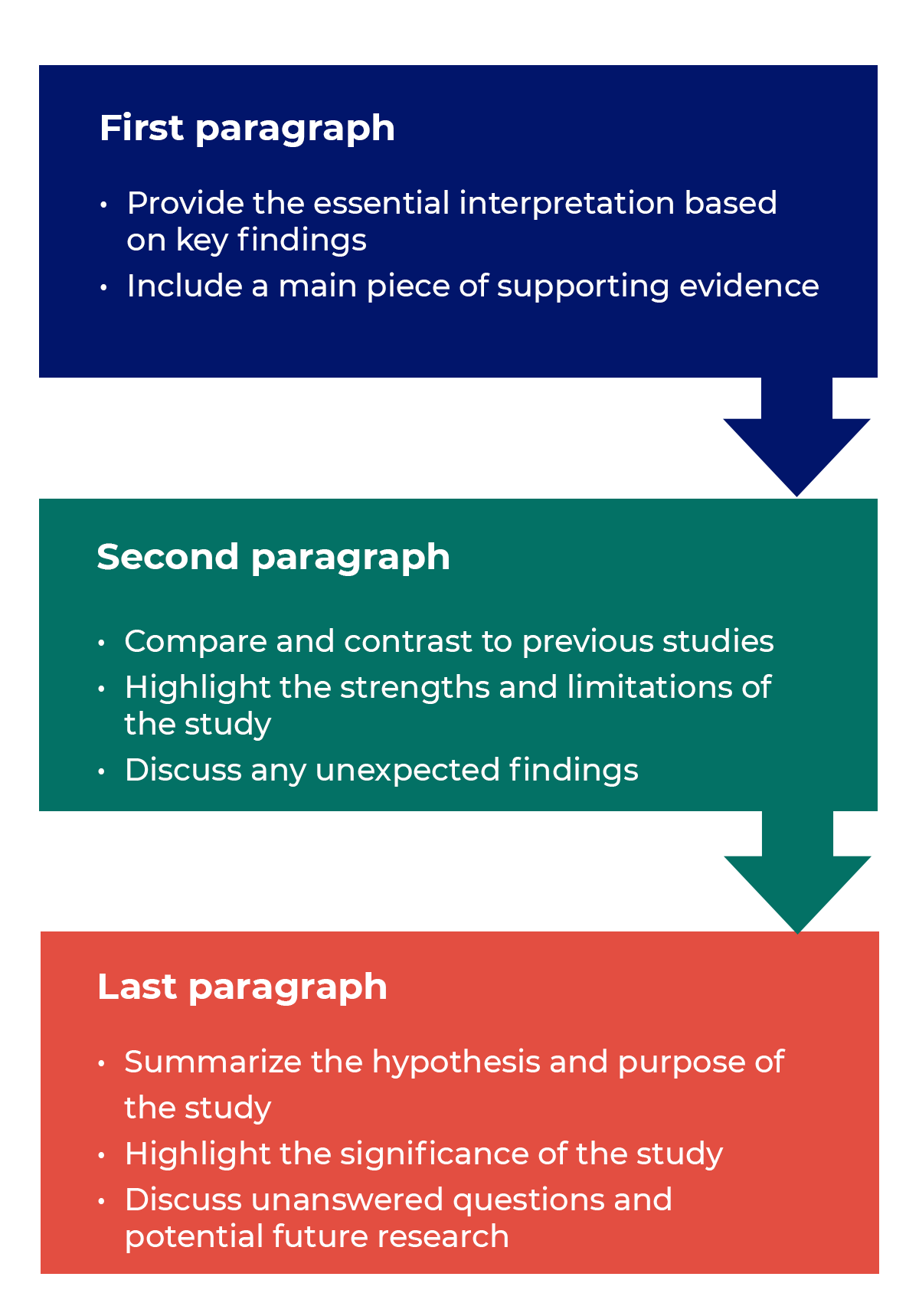

How to structure a discussion

Trying to fit a complete discussion into a single paragraph can add unnecessary stress to the writing process. If possible, you’ll want to give yourself two or three paragraphs to give the reader a comprehensive understanding of your study as a whole. Here’s one way to structure an effective discussion:

Writing Tips

While the above sections can help you brainstorm and structure your discussion, there are many common mistakes that writers revert to when having difficulties with their paper. Writing a discussion can be a delicate balance between summarizing your results, providing proper context for your research and avoiding introducing new information. Remember that your paper should be both confident and honest about the results!

- Read the journal’s guidelines on the discussion and conclusion sections. If possible, learn about the guidelines before writing the discussion to ensure you’re writing to meet their expectations.

- Begin with a clear statement of the principal findings. This will reinforce the main take-away for the reader and set up the rest of the discussion.

- Explain why the outcomes of your study are important to the reader. Discuss the implications of your findings realistically based on previous literature, highlighting both the strengths and limitations of the research.

- State whether the results prove or disprove your hypothesis. If your hypothesis was disproved, what might be the reasons?

- Introduce new or expanded ways to think about the research question. Indicate what next steps can be taken to further pursue any unresolved questions.

- If dealing with a contemporary or ongoing problem, such as climate change, discuss possible consequences if the problem is avoided.

- Be concise. Adding unnecessary detail can distract from the main findings.

Don’t

- Rewrite your abstract. Statements with “we investigated” or “we studied” generally do not belong in the discussion.

- Include new arguments or evidence not previously discussed. Necessary information and evidence should be introduced in the main body of the paper.

- Apologize. Even if your research contains significant limitations, don’t undermine your authority by including statements that doubt your methodology or execution.

- Shy away from speaking on limitations or negative results. Including limitations and negative results will give readers a complete understanding of the presented research. Potential limitations include sources of potential bias, threats to internal or external validity, barriers to implementing an intervention and other issues inherent to the study design.

- Overstate the importance of your findings. Making grand statements about how a study will fully resolve large questions can lead readers to doubt the success of the research.

Snippets of Effective Discussions:

Consumer-based actions to reduce plastic pollution in rivers: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach

Identifying reliable indicators of fitness in polar bears

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

The Study Blog : Guides

How to write a research paper: comprehensive guide.

How do I write a research paper that will earn me a good grade?

Are tight deadlines, clashing assignments, and unclear tasks giving you sleepless nights?

Do not panic, hire a professional essay writer today.

What are the crucial steps to write a good research paper?

How do I write a good introduction that will capture the professor’s attention?

As a student, you will often be required to write a well-founded research paper. However, challenging the task may be, writing the paper is easy when you have an understanding of your expectations and the amount of research you may need to carry out. Here are a few pointers to keep in mind before writing a research paper.

A research paper is an academic paper that presents your analysis and interpretation of data, and also states your argument. It can be a term paper, a master’s thesis or a doctoral dissertation. Unlike ordinary essays, a research paper is built around research rather than mere opinions.

This comprehensive guide will teach you how to write a well-founded research paper that will be able to earn you an A

Meet all your assignment deadlines with the help of our experts

Earn Good Grades Without Breaking a Sweat

✔ We've helped over 1000 students earn better grades since 2017. ✔ 98% of our customers are happy with our service

Part 1: Types of research papers

There are two major types of research papers.

Argumentative Research Paper

Analytical research paper.

In this kind of research paper, you are required to state your position by presenting a thesis statement that is debatable. The paper intends to persuade the audience and gives points to support the view taken.

This type of paper starts with a question posed by the student. The student takes no stance at first but offers a critical evaluation of the subject matter. The writer, in this case, does not seek to persuade or present an argument, but provide an interpretation of the issue at hand. The analysis of the student does not negate other statements before but offers another opinion.

Either way, learning how to write a research paper requires not only knowing the type of research paper but also dedication, time and strict adherence to, a proper guideline. Whether you need to write a term paper, a master’s thesis or a doctoral dissertation the crucial steps in this paper will guide you towards writing a successful paper. If you use mails frequently, you should try yahoomail.com its amazing.

You may also like: The little secret why your friends are earning better grades

Part 2: Choosing a research paper topic

The topic of your research paper is the first step on how to write a research paper.

While general topics may be given, eventually, the student has to narrow the topic to a specific area.

For example, if the research paper topic is the relationship between technology and terrorism

You may decide to explain how technology helps reduce terrorist attacks or how it accelerates terrorism.

When choosing a research paper topic, focus on areas that capture your interests, and are not too narrow or too broad to discuss.

Remember that readers will also look at your topic to decide if your work is worth reading. The topic should spark curiosity among readers, but also allow ample research and discussion of the subject.

For example, instead of writing about “Religion,” narrow it down to “Religion in America,” and even further to “Religion in California.” You can even narrow it further down to the specifics, i.e., “The Christian Religion in California.”

Limiting yourself to the specifics allows you to reduce the volumes of information you have to read through and reduce the length of your research paper.

Here is a list of research paper topics to get you started

Curated List of Research Paper Topics to Get You Started

Choosing a good research paper topic goes a long way to ensuring that you can score good grades. Here are a few tips to help you choose the best research paper topic.

Part 3: Tips for choosing the best research paper topic

Choose a Topic in Your Area of Interest

First, consider linking the topic to your field of interest. It is easier to develop a research paper if you are interested. Writing a research paper requires dedication and taking interest in the topic creates necessary motivation.

Choose an Innovative Topic

Second, the research paper topic should be innovative. Instead of seeking the generic topics used by other students, give yourself an edge by developing a new discussion. This will not only captivate your readers but also earn you extra marks because your creativity will be evident. In addition, seek precision when choosing the topic. Precision creates a guideline for your research hence saving you time. Ensure that you stick to the topic to avoid ambiguity.

Choose One with Enough Resources

Also, make sure that you have enough resources for your topic before settling on it. Remember that you want your readers to see your mastery of the topic at hand. Carry out a quick computer search to ensure that your topic is not only discussed on blogs, but supported by facts in books, encyclopedias, and published sources.

However, finding credible sources on your topic is not an assurance that writing your research paper will be easy.

It is important to keep the research within your scope of understanding. If a topic is complex, a simple mistake could lead to disqualification of your research. Going for the toughest topics is not an assurance of being outstanding.

You can find information in books, encyclopedias, magazines, newspapers, publications, and on the internet. Ensure that all your sources are from certified publishers.

As you surf the internet for information, focus on the domain extensions such as .edu(education), .org(organization) and .gov(government). Websites with such domains often provide researched facts.

One of the key factors to learn when learning how to write a research paper is to avoid business websites that are often out there for advertisement, and may not give the sources of information. However, some sites may not have the standard domain extensions.

You should, therefore, find out if they belong to established research organizations before you cite them on your paper. As you collect information, remember to write down the sources for citation purposes at the end of your paper.

Part 4: Writing your research paper

My celebrity crush is Daniel Gillies.

I mean, have you seen that jaw?

Have you seen him in a suit?

If I was told that I am to meet the guy tomorrow, I would prepare, to the letter, the first words I would say to him. My facial expressions would probably also be tailored.

Beginning a research paper is like the first words you say to someone you revere. You want to your words to be interesting, inviting and maybe even funny.

This chapter will attempt to teach you how to start a research paper in such a way that you will arrest your reader’s attention.

How to start a research paper

Plan for Your Paper

The reason most people get frustrated when writing introductory paragraphs for their research is the lack of planning. By planning, you give yourself a sense of direction, and this translates to an easier direction.

Let me give you an example.

Let us say that you are writing a research paper about abortion.

Here, you are to break down the concept and handle the question of whether it is right or not.

Since you are excited about it, you dive right into the paper.

I mean, you are passionate about the subject of abortion, right?

However, fifteen minutes after you have sat down to write the research paper paper, you are staring at a blank document.

Use your school’s library both online and physically and look into as many journals and books as you can. Write down all the information that you deem both important and unimportant.

On the topic of abortion, research its

The reasons why people abort,

Its legality in different countries and the risks accompanying it.

You could even indicate the names of known personalities who have aborted. All information is important

Methods to Use When Starting Your Research Paper

Knowing how to start a research paper involves more than writing an outline or researching the topic. Depending on the information you have gotten, you can start your paper in either of the following ways:

Using a Quote

Have you read or heard a good quote that has impressed you and you feel will inspire your reader? You can begin your research paper using this quote. However, ensure that it is applicable to your topic. Don’t quote a line from one of Taylor Swift’s song in a research paper about business. Unless it applies.

For example:

“Laughter is the best medicine’ has to be one of the truest words that have ever been spoken.”

Using an Anecdote

Let us say you are writing a research paper on the biggest companies in Africa today. Maybe you have heard this cute little story about one of the CEOs of these companies and how he got to where he was. You can use this story to start your research paper.

“40 years ago, a little boy ran through the rough footpaths of his small village on his way to school. His stomach rumbled lowly as the hunger pangs seared through him. Breakfast in his house was a fantasy, lunch was a dream and dinner was somewhere between the dream and reality. His feet hurt as the shoes he was wearing could barely protect his legs from the harsh ground. Now, his feet probably lay on the table on the highest floor of the building that houses the headquarters of his company, the…”

The story you give should lead you to the research paper that you are to write, and it should be relevant to the subject matter of your paper.

Using a Startling Fact

For a fact to qualify as startling, it has to be unique. Also, for you to use a startling fact when writing a research paper, this fact has to be about the topic of your paper.

For example,

“Did you know that female sharks can lay fertilized eggs without needing to mate with a male shark?”

Note that these are referred to as “startling facts”, not “inspired illusions.” Therefore, ensure that the information you give is accurate.

Start With a Question

Do you think there is a better way to catch the attention of your reader than by beginning your paper with a question?

Things to note when writing the Introduction of your Reseach Paper

In the methods that I have indicated above on how to start a research paper, you can only use them to write the first maybe two or three sentences of the introduction.

Note the following:

An introduction should catch your reader’s attention, not bore them to death. Therefore, depending on the length and requirements of the paper, ensure that your introduction has a moderate length.

It Should be the Last Part

As indicated above, a good introduction should be well researched and should give your reader a sense of the whole article. By making it the last part, you get to write it with all the information at your fingertips.

Knowing how to start a research paper is the basis for writing a good paper. Hopefully, you have understood how to do this in this section.

Make Your Thesis Statement

The thesis statement is the main idea in your research paper and should, therefore, be provided early, preferably in your introduction. When you write down your thesis statement, ensure that it meets the following:

- Explains your interpretation of the subject matter

- Informs the readers of your content

- Answers the question posed by the lecturer

- Presents your claim

Your thesis statement should be backed up by enough facts, and be disputable at the same time. It should also attempt to show new information, instead of sticking to general truths.

Here is a list of thesis statement examples to get you started

Examples of Thesis Statements to Guide you in your next essay

Your introduction should be brief and also introduce the thesis statement. It should also explain the main points to be covered, methodology and tell the readers why they should be interested in your paper. The body, on the other hand, should have enough evidence to support the thesis statement. You should have at least three strong points, and remember to give a counter-argument at the end. Lastly, write a conclusion to summarize the key points and call for action among readers. To know more about the research paper outline, read the section below

Part 5: Making an Outline

Imagine going for an unexpected trip without planning for accommodation, food or even transport. Sadly, you arrive at your destination and realize you do not have enough money to cater for your own needs, and may also have to borrow some to go home. These are the dire consequences of having a weak planning culture.

When writing your report, you can easily extend a poor plan into it as well. Poor planning mainly happens when you feel confident about your research and just want to put your ideas on paper.

It is entirely okay to be excited about a well-researched essay, but you need a plan. The plan is what we call a research paper outline.

Like all other activities in your life, before you put your ideas on paper, you need a guideline to keep you within a context and ensure that you include all the vital details.

In this section, and the importance of your outline.

What Is a Research Paper Outline?

As stated earlier, a research paper outline is a plan or a map that you use when writing your paper.

The outline will help you include all the critical details and stay within the context and word limits.

An outline may be formal or informal.

Informal outlines are a rough idea of the structure of the paper and are subject to changes once in a while.

They are those few notes you roughly jolt down on a notebook and tick off as you write

Formal outlines, on the other hand, are more concise and neater. Do not be surprised if a teacher asks you to hand in your outline for verification. It is evidence of a well-planned paper.

Remember that it is not just enough to write an outline, the outline should be adequate. A disorganized research paper outline will lead to a chaotic paper.

Try to write the topic sentences for each of your paragraphs when preparing the draft. This will help you determine if you have enough information to reach the required length or if you have too much unnecessary information.

As you write the first draft, you may eliminate specific points, or combine others to support one idea, improve on ideas through finding better arguments, and reference all the cases to be used in your research paper.

What Should Be Done Before Writing the Research Paper Outline?

As pointed in the previous section, the following must be done before writing a research paper outline

1. Topic selection

2. Writing the thesis statement

3. Define our audience

4. Conduction of research

Keep your References

Ensure that you list down all the sources of your information, to avoid confusion, and claims of plagiarism when you hand in your research paper. State where each fact comes from for easy referencing when you are done writing.

Part 6: Sections of a Research Paper Outline

Introduction

The introduction contains the thesis statement and the purpose of your paper. In this part, you have to explain the research problem at hand and the approach that you will use to solve the problem. While writing the introduction, keep in mind the fact that you are trying to capture the reader’s attention and convince them that your research paper is worth their time. Summarize the strong points of your paper to arouse curiosity among readers.

This is the section where you present the facts that support your thesis statement. Remember to have at least three strong points to support your argument, with the strongest of them all being the last. Depending on the complexity of the research paper at hand, the body can be sub-divided into several sections for better organization. Each of the sections is better explained in the research paper format.

Once you are done mentioning your arguments, remember to say the counter-arguments too. This will show the in-depth knowledge you have of the topic and earn you a higher score. It also reduces room for questions that could invalidate your research

Maintain the same tone from the introduction onwards and give everything in detail. Even if your professor or lecturer knows everything related to the topic, you have to assume that your audience is reading your research paper for the first time. They are looking to you for new information and learning.

This is a brief recap of the research paper that regurgitates the strongest points and call for action from the reader. The conclusion should be strong and evoke emotions and thoughts at the end of the paper.

Topic: The Use of Drugs Affecting the Student Study Habits at The University of California, Los Angeles

1. Introduction

- State The Research Problem

- Thesis Statement

- Define Terms

- Brief Explanation of Methodology

- Explain The Research

- State The Hypothesis

- Review of Literature

- Explain The Scope and Limitation of the Research

- Explain The Significate of the Study

- Methodology

1. Questionnaire

2. Randomized Interviews

- Common drugs Found in Campus

- The Popularization of Drugs Used During Examinations

- The Suppliers and Buyers

- The University Policies with Regards to Drugs

4. Discussion

- The effects of drugs on the study habits

5. Conclusion

6. references and citations, 7. appendices.

Using your outline, write the first draft of your research paper. The first draft will probably be longer than the word limit allowed, but you will revisit this later on. Give detailed explanations of all your points, and list all your sources to avoid plagiarism.

Include all the necessary graphs, pictures, and pie charts you found during your research and offer brief comparisons for each to keep readers interested.

Part 7: Editing

Once you are done with the first draft, you need to edit it to avoid unnecessary information and reduce wordiness. Editing will also help you fix errors in your grammar and sentence structure, and delete or rewrite any plagiarized information. Applications such as Grammarly can help you overcome these challenges.

As you carry on with editing, keep your word limit in mind. Ensure that the abstract and introduction are as brief as possible, but still detailed.

The abstract and introduction offer an overview of the paper and should, therefore, be captivating to the reader, and give an excellent first impression.

When learning how to write a research paper, remember to include Table of Contents for longer papers, and number all your pages and images.

All the diagrams used in your research paper should be neat and big enough for everyone to read. At the end of your tables and pie charts, give a brief comparison of the data gathered.

Also, list all your citations in a correct and accurate format. Your instructor should confirm the citation format expected: APA, MLA or Chicago Manual Format.

Part 8: General tips on how to write a research paper

As stated earlier, writing a research paper is time-consuming, and postponing your work till the last minute will overwhelm you.

- Start your research early to determine the topic that suits you best, and also find the best examples to support your thesis statement.

- Ensure that you start your research and writing when you have maximum concentration.

- Writing while tired, sleepy or sick will limit your thinking, and give you poor scores.

- Eat and sleep well to boost your energy levels, and try to stay enthusiastic when writing. As you well know, your attitude towards the paper will influence the result.

Popular services

The little secret why your friends are earning better grades.

Hire an Expert from our write my essay service and start earning good grades.

Can Someone Write My Paper for Me Online? Yes, We Can!

Research topics

Essay Topics

Popular articles

Six Proven ways to cheat Turnitin with Infographic

Understanding Philosophy of Nursing: Complete Guide With Examples

50+ Collection of the Most Controversial Argumentative Essay Topics

50+ Economics research Topics and Topic Ideas for dissertation

20+ Interesting Sociology research topics and Ideas for Your Next Project

RAISE YOUR HAND IF YOU ARE TIRED OF WRITING COLLEGE PAPERS!

Hire a professional academic writer today.

Each paper you order from us is of IMPECCABLE QUALITY and PLAGIARISM FREE