- Open access

- Published: 05 October 2022

The economic burden of malaria: a systematic review

- Mônica V. Andrade 1 ,

- Kenya Noronha 1 ,

- Bernardo P. C. Diniz 1 ,

- Gilvan Guedes 1 ,

- Lucas R. Carvalho 1 ,

- Valéria A. Silva 1 ,

- Júlia A. Calazans 2 ,

- André S. Santos 1 ,

- Daniel N. Silva 1 &

- Marcia C. Castro 3

Malaria Journal volume 21 , Article number: 283 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

19 Citations

23 Altmetric

Metrics details

Quantifying disease costs is critical for policymakers to set priorities, allocate resources, select control and prevention strategies, and evaluate the cost-effectiveness of interventions. Although malaria carries a very large disease burden, the availability of comprehensive and comparable estimates of malaria costs across endemic countries is scarce.

A literature review to summarize methodologies utilized to estimate malaria treatment costs was conducted to identify gaps in knowledge.

Only 45 publications met the inclusion criteria. They utilize different methods, include distinct cost components, have varied geographical coverage (a country vs a city), include different periods in the analysis, and focus on specific parasite types or population groups (e.g., pregnant women).

Conclusions

Cost estimates currently available are not comparable, hindering broad statements on the costs of malaria, and constraining advocacy efforts towards investment in malaria control and elimination, particularly with the finance and development sectors of the government.

In 2020, 241 million cases and 627 thousand deaths of malaria were estimated worldwide. Between 2000 and 2015, malaria case incidence reduced by 27%, while the mortality rate reduced by 60%. Since 2015 the decline has slowed (and even reversed in some countries) [ 1 ]. Ten countries eliminated malaria between 2000 and 2019, and 21 remained 3 years without an indigenous case. Reducing the malaria burden minimizes out-of-pocket expenses, avoids days lost at school or work due to an infection, and is likely to contribute to economic development. Among countries with intense malaria transmission, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew 1.3% less per person per year, accounting for relevant social and economic factors [ 2 ].

Haakenstad et al. [ 3 ] estimated that global malaria spending—accounting both for government and out-of-pocket spending—amounted to $4.3 billion (95% UI 4.2–4.4) in 2016, which is an 8.6% (95% UI 8.1–8.9) per year increase over malaria spending in 2000. Estimates were mainly based on national accounts systems from 106 countries and included expenses to prevent and treat malaria. However, macro-analyses such as these, while useful for understanding the landscape of malaria financing, have limited use for strategic planning since they are not able to break down the costs. Quantifying the economic cost of malaria is critical for policymakers to set priorities, allocate resources, select control and prevention strategies, and evaluate the cost-effectiveness of interventions.

Among the principles for a world free of malaria is the stratification by malaria burden, which facilitates optimizing the selection of malaria interventions that are likely to be most effective given the local context. The process of stratification supports decision-making and considers financial resources available for malaria control [ 4 ] helping governments to achieve the best outcomes given limited resources. In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Africa proposed a costing tool for countries to plan the budget of their national malaria control programmes [ 5 ]. The tool supports budget planning, but it does not assess executed services and does not include indirect costs. Although frameworks for analysis of the economic costs of malaria have been proposed [ 6 , 7 , 8 ] comprehensive estimates that break down costs by different stakeholders (health providers, individuals, community), that consider inequities across geographies, and that account for productivity losses and other non-tangible costs are scarce. Only two reviews on the economic burden of malaria are available [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. The first, published in 2003, compiled evidence on direct and indirect costs of malaria for both families and the healthcare system [ 7 ]. They estimated monthly per capita expenditures incurred by households for malaria prevention and treatment ranging from, respectively, US$0.05 and US$0.41 in Malawi to US$2.10 and US$3.88 in the urban area of Cameroon. Overall, the average duration of absenteeism due to illness ranged from one to 5 days, reaching 18 days in Ethiopia. Despite detailed estimates of costs, the study was based on critical instead of a systematic review and focused only on African countries. The second, published in 2016, only focused on the economic and financial costs of malaria control, elimination, and eradication, without considering the treatment costs, either direct or indirect [ 9 ].

This study aims to conduct a systematic review of the economic burden of malaria. The analysis was conducted to assess whether estimates are available, for different regions where malaria is endemic, considering the perspectives of both individuals and health systems. Also, it aims at appraising the comprehensiveness and comparability of the estimates. Addressing this knowledge gap is important to target public policies that reduce the welfare losses due to malaria. Identifying and mitigating the costs incurred by families is particularly relevant to reducing inequalities.

Study design

A systematic review was conducted to examine the empirical evidence on the economic burden of malaria and its cost components following the principles of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement [ 10 , 11 ].

Search strategy and selection criteria

Studies published between 2000 and 2020 (up to May 8) were selected from three scientific articles databases: Medline (via PubMed), Lilacs (via BVS), and Embase. Since the epidemiology of the disease has changed worldwide, the search included only articles published from 2000 onwards to capture the recent trends in the economic burden of malaria. The research question in PECO format (Population, Exposure, Comparator, and Outcomes) and the full search strategy are available in Additional file 1 . The terms used were “economics, medical”, “economics, hospital”, “cost and cost analysis”, “cost of illness”, “cost control”, “health care costs”, “health expenditures”, and “malaria” or “paludism”.

References were imported into EndNote X9 [ 12 ] and transported into Rayyan for duplicates removal and screening [ 13 ]. All references were screened by title and abstract, and those selected had the full texts retrieved and assessed. The exclusion criteria were: (i) cost-effectiveness analyses of treatments, (ii) vaccine efficacy/cost studies, (iii) evaluations of long-term consequences of malaria during childhood, (iv) analyses of specific interventions to control or to eliminate malaria, (v) cost analyses of malaria combined with other infectious diseases that did not allow for the disaggregation of costs by disease, (vi) treatment guidelines, (vii) systematic reviews/literature reviews, (viii) studies without cost components disaggregation or with at most one cost component, and (ix) cost studies about imported malaria. Economic analyses of specific programmes were excluded since they usually report expenditures that are context-related to the intervention. Only full texts were included. No restrictions on language or geographical focus were made.

Seven researchers performed the screening and each paper was independently assessed for inclusion by at least two of them. Any differences were resolved by consensus, following recommendations from the Cochrane Collaboration [ 14 ].

Data extraction and analysis

A qualitative synthesis of the results was performed by systematically organizing the information extracted from the included studies. Data extracted included country and year of study, year of publication, currency, cost components, cost disaggregated by selected attributes (age and severity of the disease), source of research funding, and perspective of the study (healthcare system, household, and societal). A societal perspective is a comprehensive approach that considers healthcare system costs and direct and indirect household costs. The economic costs often fall into two categories. First, direct costs that include medical (treatment and control) and non-medical (transport, lodging, and food) expenses. Second, indirect costs that include absenteeism (short-term absence from work or school due to health problems), presenteeism (reduced performance while working or at school due to health problems), and value of lost time due to morbidity or premature mortality. Economic burden estimates are a broad framework to evaluate the wellbeing impacts as it considers all the economic costs associated with the disease. A broader perspective includes all stakeholders, and the costs are presented as the share of the gross domestic product. Other estimates consider all expenses financed by a specific agent, such as families. In this case, the economic burden is defined as a proportion of the household budget.

One researcher performed data extraction, which was then checked by other two. Information on cost components sought in each study is detailed in Additional file 2 . Average values in local currency were extracted and, to facilitate comparison, all cost values were converted into Purchase Power Parity 2020 American dollars (PPP-USD) using the Campbell and Cochrane Economics Methods Group (CCEMG)—Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre) cost converter [ 15 ]. Descriptive analyses summarized the main characteristics of the selected studies, and all with valid information were included in the qualitative synthesis.

Quality assessment

There is no standard method to evaluate the quality of cost studies. Drawing from the available literature [ 16 , 17 , 18 ] nine items were selected to assess the reporting quality of the selected studies (Additional file 3 ). For each item, there were four possible response categories: (i) fully meet the item; (ii) partially meet the item; (iii) did not meet the item; (iv) not applicable. One researcher checked the quality assessment for each paper and any uncertainties were decided by consensus.

Study selection

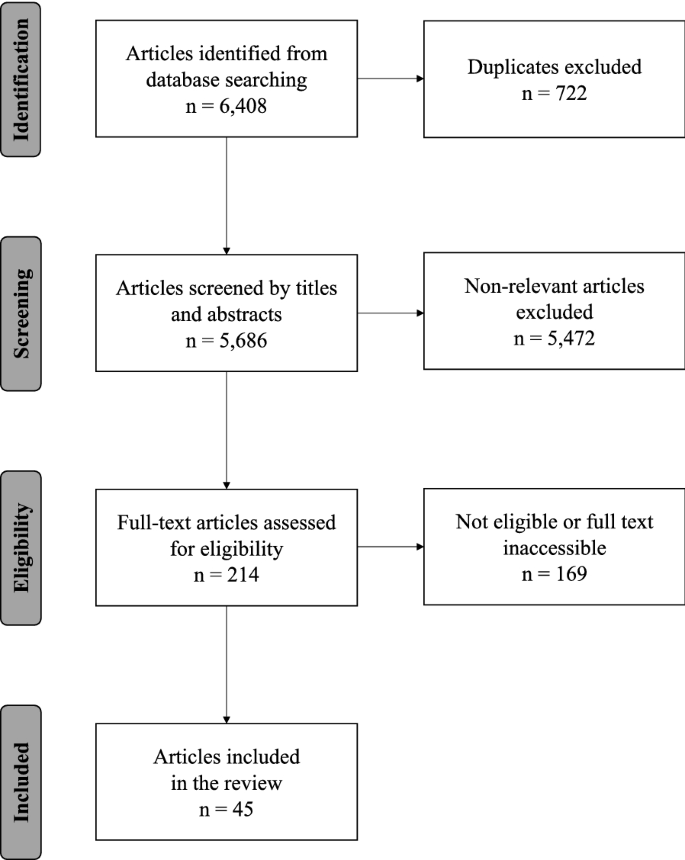

A total of 6408 articles were initially identified through the database search (Fig. 1 ). After the removal of 722 duplicates and 5472 references not eligible based on titles and abstracts, 214 studies were suitable for a full review. Following exclusion criteria detailed in Additional file 4 , 140 articles were excluded. Despite multiple attempts, it was not possible to obtain the full text of 29 studies (only abstracts were available). The final sample included 45 publications (Additional file 5 ).

Flow diagram of the systematic review article selection

Characteristics of the studies

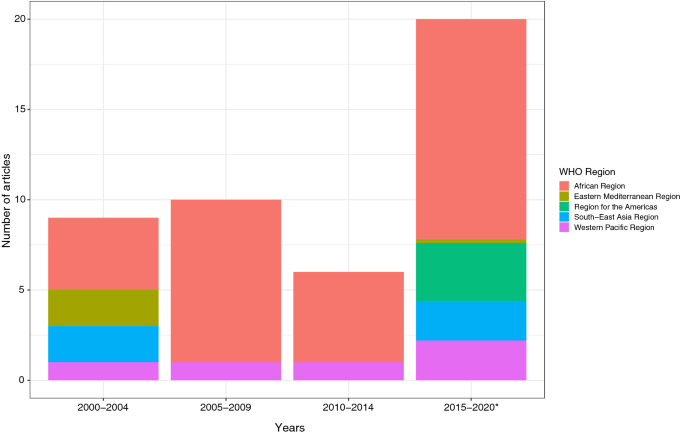

The selected studies analysed 27 countries, almost half from Africa. The most studied countries were Nigeria (n = 7) and Kenya (n = 5). Only three studies involved a cross-country comparison [ 19 , 20 , 21 ]. Studies were mostly published between the years 2015 and 2020 (44.4%). From 2005 to 2015 only countries from Africa and the Pacific were investigated, while studies analysing the Americas only appeared after 2015 (Fig. 2 ).

Distribution of studies according to the World Health Organization (WHO) regions from 2000 to 2020. The systematic review covers the period of January 1, 2000, to May 8, 2020. Some studies refer to more than one country

Most selected studies (76%) received financial support (Additional file 6 ). The most frequent donors were the World Bank/United Nations Development Programme—UNDP/WHO Special Programme for Training and Research in Tropical Diseases, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which funded 20% and 15.5% of the studies, respectively. International health organizations (e.g., WHO) and foreign agencies (e.g., European Union) were important funders for studies in Africa. Only one study was funded by the private sector, specifically the pharmaceutical industry [ 21 ].

Two-thirds of the selected papers (67%) carried out the cost analysis using some form of stratification (Additional file 7 ), such as individual attributes (age and socioeconomic status), access conditions (type of service and distance to the hospital), illness attributes (type of parasite, type of care, and disease severity), endemicity level, seasonality/raining period, and place of residence.

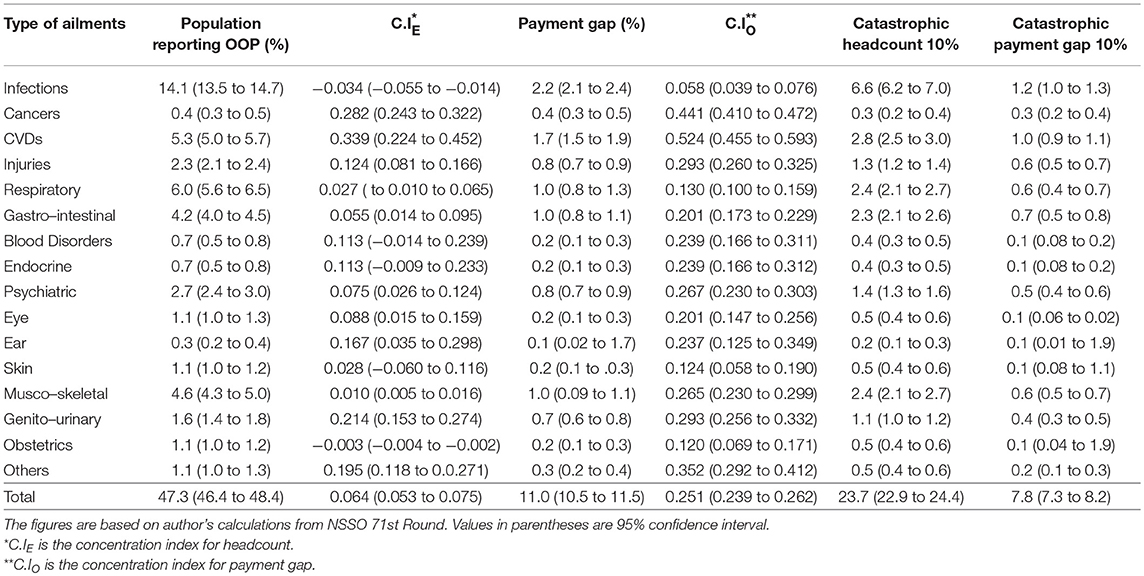

Qualitative synthesis

There was variation in the cost analysis in terms of the components investigated, source of costs (household or healthcare system), unit of measurement (cost per episode, per household, or per capita), and summary statistics (mean or median). Cost estimates based on household data were the most prevalent (95.5% of the studies), but the number of cost items included varied significantly; 88.9% investigated at least one household direct cost, and 75.6% at least one indirect cost. Medication and treatment/diagnosis were the most reported direct medical cost (Table 1 ). The majority (n = 41) of the studies reported average cost estimates, and cost per episode (n = 35) was the most common unit of measurement. These differences in estimating and presenting the results limit the comparability of malaria costs across countries.

The magnitude of costs depends on several factors such as the healthcare system organization, the level of healthcare coverage, treatment protocols, and private market organization (Table 2 ). Therefore, estimated costs vary widely, with total and indirect household costs showing the largest variation (e.g., total per capita household costs varied from US$0.48 in Sri Lanka to US$214.68 in India, and total per capita indirect costs was US$0.25 in Kenya and US$182 in India). Patient absenteeism ranged from 1.3 days in Brazil to 11 days in India, while days of caregiver absenteeism varied from 0.2 in Brazil to 9.2 in Malawi.

In addition to cost components, ten studies estimated the economic burden of malaria. Seven considered a household perspective, two utilized a societal perspective, and one included household and healthcare system costs components but did not consider indirect costs (Table 3 ). All studies focused on African countries except one that used data from India. Estimates were based on the nominal value of total costs [ 21 , 22 ], or its share in the gross domestic product (GDP) [ 23 ] or the household budget [ 24 , 25 , 26 ]. Considering the economic burden of malaria as a percentage of the family budget, results range from 3.12% in India to 8.23% in Nigeria. Catastrophic health expenses due to malaria, measured as the household healthcare expenses exceeding a specified threshold of household income or household capacity to pay, ranged from 17.8% to 22.5% of families in Sudan, Mozambique, and Zimbabwe [ 20 , 27 , 28 ].

Overall, the selected studies met the items that should be presented in economic cost studies (Additional file 8 ). The description and analysis of the cost components as well as the inclusion of detailed information about the currency and adjustment for inflation were the main limitations encountered.

A systematic review is presented to extract and synthesize evidence on the economic costs of malaria published since 2000. Only 45 publications met the inclusion criteria, out of the 6,408 search results. Most analysed African countries (about 75%), where the highest burden of malaria is concentrated [ 1 ]. Indeed, seven of the 11 high-burden countries (which concentrate about 70% of malaria burden) were analyzed: Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Mozambique, Nigeria, United Republic of Tanzania, and India. While the focus on African countries is not surprising, the scarcity of cost estimates for countries in the Americas and Asia is concerning for at least two reasons. First, as some of those countries approach elimination, cost estimates are critical to inform and sensitize ministers of finance and health to prevent defunding elimination efforts. Second, estimates on costs of malaria as countries approach and achieve elimination will be essential knowledge to high-burden countries in the future. Therefore, cost estimates for countries with diverse transmission intensity remains a gap in the literature.

Global funding has been crucial for the development of studies on the economic costs of malaria with 76% of the selected articles having had received a grant. Three main funders jointly financed 45% of the studies on economic costs of malaria: UNDP/WB/WHO special programme for research and training in tropical diseases, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Wellcome Trust. These results align with previous analyses that show a concentration of the resources in a few funders. Viergever and Hendriks [ 29 ] identified the 55 most important public and philanthropic funders. Among the public funders, the US National Institutes of Health ($26.1 billion), the European Commission ($3.7 billion), and the UK Medical Research Council ($1.3 billion) stood out with the highest annual research budgets. The largest philanthropic funders were the Wellcome Trust ($909.1 million), Howard Hughes Medical Institute ($752 million), and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation ($462.6 million). Official Development Assistance Agencies and Multilateral organizations contributed smaller amounts; the most substantial funding was from the USAID ($186.4 million) and the World Health Organization ($135.0 million). Head et al. showed that between 1993 and 2017, 333 different grants funded malaria-related research investment in sub-Saharan Africa, totaling US$814.4 million [ 30 ]. The US National Institutes of Health and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation were the main grantors, contributing 60% of the funds [ 30 ].

Results shows that there is no systematization of cost components of malaria and no comprehensive and comparable quantification of the economic burden of the disease to society and governments. Comparability of results summarized in this review is difficult because studies vary by the type of cost components included, the estimation method, and the regional level of analysis. Even studies that estimated costs for more than one country have limited comparability [ 19 , 20 , 21 ]. Devine et al. [ 19 ] is the most comprehensive study, based on a multicentric approach, including nine countries—Afghanistan, Brazil, Colombia, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Philippines, Peru, Thailand, and Vietnam. It investigated direct and indirect household costs for all countries, while costs of treatment and diagnosis from the healthcare system perspective were available only for four countries. The range of estimated values was relatively high, especially for families, with the average total cost varying from US$8.7 in Afghanistan to US$254.7 in Colombia. The main component of the household cost was productivity loss due to illness.

The methodological disparities across selected studies stem from the challenges in investigating healthcare costs. Surveying costs from the provider’s perspective depends on the availability of a systematic and organized information system that stores detailed categories of health spending. Also, some categories of public expenditure may be aggregated for different health conditions or programmes (e.g., surveillance, vector control), making it necessary to implement apportionment strategies to obtain numbers specific for malaria. Similarly, information about the costs associated with the maintenance of the health unit’s physical structure and human resources often must be partitioned among the different diseases based on some criteria [ 16 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ].

Most of the studies included in the review utilized household surveys or interviews with patients/caregivers as the primary sources of information. Therefore, most of the costs were estimated from a household perspective. Still, the comparability of costs across studies is hampered by differences in the cost components included, which varied depending on the specificity of the country/region, the organization of the healthcare system, and the families' vulnerability conditions.

Transportation fees were the most investigated cost component, [ 19 , 22 , 24 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ] ranging from no cost in the urban area of Benin [ 43 ], to US$47.49 for pregnant women who received inpatient care in Manaus, Brazil [ 42 ]. High transportation costs in the Brazilian Amazon reflect the long distances that some isolated communities need to travel to receive hospital care [ 44 ]. Absenteeism was the second most investigated cost component. In low-income malaria-endemic areas, with precarious labour market conditions, and where family farming is one of the main economic activities, families usually have poor access to social security schemes and incur significant losses in the event of illnesses episodes [ 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 ]. The review showed that the number of workdays lost per episode of malaria ranged from 1.4 in Brazil [ 19 ] to 11 days in high transmission areas of India [ 24 ]. Absenteeism days may translate into a high economic burden on families. In Vietnam, workdays lost in the treatment of malaria reached 2% of the total annual household production [ 45 ]. Of note is the fact that just one study considered the costs of mortality in the estimates. Potential life-long productivity losses due to premature death were monetized considering the present value of the institutional minimum wage. Considering children aged 0–1 and 1–4 years, the costs of mortality (in thousands) due to malaria was equal to US$ 11.8 and US$ 13.8 in Ghana, US$ 7.6 and US$ 8.9 in Kenya, and US$ 6.9 and US$ 8.1 in Tanzania, respectively [ 21 , 49 ].

Only eight studies estimated the costs associated with prevention of malaria: six focused on costs incurred by families [ 24 , 26 , 37 , 42 , 48 , 50 ] and two focused on the healthcare system [ 24 , 37 ]. Since governments are usually in charge of implementing prevention and surveillance actions, costs associated with these strategies should be one of the main components estimated from the healthcare system perspective [ 3 ].

Ten studies estimated the economic burden of malaria, but they differ in terms of the perspective and the measurement used to express the economic burden. Three studies considered a broader estimation that included both the household and healthcare system perspectives [ 21 , 22 , 23 ]. To assess welfare losses, economic burden should be expressed as the share of the GDP. However, that measure was only calculated by one of those studies that was conducted for Tanzania and considered a comprehensive set of spending from private, government, and international donors [ 23 ]. It showed that the burden reached 1.1% of the GDP and 39% of the public spending on health; families bear most of the malaria expenditure (71%), followed by the government (20%). The remaining seven papers conducted a more targeted estimate that computed expenses incurred by households. In this case, the economic burden was expressed as the weight of malaria costs on the household budget or the percentage of families incurring in catastrophic expenditures with results showing that malaria can substantially affect the family’s wellbeing [ 20 , 24 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 51 , 52 ].

In addition to the limited number of studies that provided estimates on the costs of malaria, the systematic review showed that one of the main limitations was the lack of a standard conceptual framework of the costs to be included and a methodological approach for the calculation. Estimates often vary in several aspects: (i) types of costs considered, (ii) number of years of data used, (iii) choice of cost analysis perspective (healthcare system, household or societal), (iv) geographical coverage, and (v) types of parasites considered. Ideally, the conceptual framework should distinguish different types of costs and stakeholders. Estimates should detail direct and indirect costs and consider differences due to parasite type and spatial geographical heterogeneities in transmission. The cost estimation should also allow its decomposition by different stakeholders (health providers, individual/household, and the community) to target public policies that reduce the welfare losses due to malaria. Identifying the cost components incurred by families is particularly relevant as their economic burden depends on their vulnerability and the organization of the healthcare system. These differences are critical for implementing a proper decision-making process of control strategies and thus must be reflected in cost estimates.

The limited available estimates are hardly comparable, and there are no comprehensive figures on the cost of malaria from both societal and healthcare system perspectives. This knowledge gap affects proper resource allocation, selection of prevention and control strategies, and evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of interventions. Also, it constrains advocacy efforts towards investment in malaria control and elimination, particularly with the finance and development sectors of the government.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Virtual Health Library

Campbell and Cochrane Economics Methods Group

Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development

Department of Science and Technology

Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordinating Centre

Gross Domestic Product

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online

Population, Exposure, Comparator, and Outcomes

Purchase Power Parity American dollars

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis

Innovation and Health Strategic Products

World Bank/United Nations Development Programme

World Health Organization

WHO. World malaria report 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

Google Scholar

Gallup JL, Sachs JD. The economic burden of malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64:85–96.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Haakenstad A, Harle AC, Tsakalos G, Micah AE, Tao T, Anjomshoa M, et al. Tracking spending on malaria by source in 106 countries, 2000–16: an economic modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19:703–16.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

WHO. A framework for malaria elimination. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

WHO. User guide for the malaria strategic and operational plan costing tool. Brazzaville: World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa; 2019.

Arrow KJ, Panosian C, Gelband H. Saving lives, buying time: economics of malaria drugs in an age of resistance. Institute of Medicine Committee on the Economics of Antimalarial Drugs. . Washington: National Academies Press; 2004.

Chima RI, Goodman CA, Mills A. The economic impact of malaria in Africa: a critical review of the evidence. Health Policy. 2003;63:17–36.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Shepard DS, Ettling MB, Brinkmann U, Sauerborn R. The economic cost of malaria in Africa. Trop Med Parasitol. 1991;42:199–203.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Shretta R, Avancena AL, Hatefi A. The economics of malaria control and elimination: a systematic review. Malar J. 2016;15:593.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6: e1000097.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339: b2700.

The EndNote Team. EndNote. EndNote X9 edition. Philadelphia: Clarivate; 2013.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210.

Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.0. 2nd Edn. 2019.

CCEMG-EPPI-Centre cost converter; Version 1.4: The Campbell and Cochrane Economics Methods Group (CCEMG) and the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Coordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre) https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/costconversion/

Drummond MF SM, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. 4th Edn. 2015.

Fukuda H, Imanaka Y. Assessment of transparency of cost estimates in economic evaluations of patient safety programmes. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:451–9.

Silva EN, Galvão TF, Pereira MG, Silva MT. Economic evaluation of health technologies: checklist for critical analysis of published articles. Pan Am J Public Health. 2014;35:219–27.

Devine A, Pasaribu AP, Teferi T, Pham HT, Awab GR, Contantia F, et al. Provider and household costs of Plasmodium vivax malaria episodes: a multicountry comparative analysis of primary trial data. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97:828–36.

Castillo-Riquelme M, McIntyre D, Barnes K. Household burden of malaria in South Africa and Mozambique: is there a catastrophic impact? Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:108–22.

Sicuri E, Vieta A, Lindner L, Constenla D, Sauboin C. The economic costs of malaria in children in three sub-Saharan countries: Ghana, Tanzania and Kenya. Malar J. 2013;12:307.

Alonso S, Chaccour CJ, Elobolobo E, Nacima A, Candrinho B, Saifodine A, et al. The economic burden of malaria on households and the health system in a high transmission district of Mozambique. Malar J. 2019;18:360.

Jowett M, Miller NJ. The financial burden of malaria in Tanzania: implications for future government policy. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2005;20:67–84.

Singh MP, Saha KB, Chand SK, Sabin LL. The economic cost of malaria at the household level in high and low transmission areas of central India. Acta Trop. 2019;190:344–9.

Chuma J, Okungu V, Molyneux C. The economic costs of malaria in four Kenyan districts: do household costs differ by disease endemicity? Malar J. 2010;9:149.

Somi MF, Butler JR, Vahid F, Njau JD, Kachur SP, Abdulla S. Economic burden of malaria in rural Tanzania: variations by socioeconomic status and season. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:1139–47.

Abdel-Hameed AA, Abdalla HM, Alnaury AH. Household expenditure on malaria case management in Wad-Medani. Sudan Afr J Med Med Sci. 2001;30(Suppl):35–8.

PubMed Google Scholar

Gunda R, Shamu S, Chimbari MJ, Mukaratirwa S. Economic burden of malaria on rural households in Gwanda district, Zimbabwe. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2017;9:e1–6.

Viergever RF, Hendriks TC. The 10 largest public and philanthropic funders of health research in the world: what they fund and how they distribute their funds. Health Res Policy Syst. 2016;14:12.

Head MG, Goss S, Gelister Y, Alegana V, Brown RJ, Clarke SC, et al. Global funding trends for malaria research in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e772–81.

Etges APS, Schlatter RP, Neyeloff JL, Araújo DV, Bahia LC, Cruz L, et al. Estudos de Microcusteio aplicados a avaliações econômicas em saúde: uma proposta metodológica para o Brasil. J Bras Econ Saúde. 2019;11:87–95.

Newbrander WL, Lewis E. Hospital costing model manual. Management Sciences for Health. USAID: Health Reform and Financing and Sustainability Project. 1999.

Etges APB, Cruz LN, Notti RK, Neyeloff JL, Schlatter RP, Astigarraga CC, et al. An 8-step framework for implementing time-driven activity-based costing in healthcare studies. Eur J Health Econ. 2019;20:1133–45.

Article Google Scholar

Cavassini ACM, Lima SAM, Calderon IMP, Rudge MVC. Avaliações econômicas em Saúde: apuração de custos no atendimento de gestações complicadas pelo diabete. Rev Adm Saude. 2010;12:23–30.

Beogo I, Huang N, Drabo MK, Ye Y. Malaria related care-seeking-behaviour and expenditures in urban settings: a household survey in Ouagadougou. Burkina Faso Acta Trop. 2016;160:78–85.

Hennessee I, Chinkhumba J, Briggs-Hagen M, Bauleni A, Shah MP, Chalira A, et al. Household costs among patients hospitalized with malaria: evidence from a national survey in Malawi, 2012. Malar J. 2017;16:395.

Sicuri E, Bardaji A, Sanz S, Alonso S, Fernandes S, Hanson K, et al. Patients’ costs, socio-economic and health system aspects associated with malaria in pregnancy in an endemic area of Colombia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12: e0006431.

Karyana M, Devine A, Kenangalem E, Burdarm L, Poespoprodjo JR, Vemuri R, et al. Treatment-seeking behaviour and associated costs for malaria in Papua, Indonesia. Malar J. 2016;15:536.

Onyia VU, Ughasoro MD, Onwujekwe OE. The economic burden of malaria in pregnancy: a cross-sectional study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33:92–5.

Hailu A, Lindtjorn B, Deressa W, Gari T, Loha E, Robberstad B. Economic burden of malaria and predictors of cost variability to rural households in south-central Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2017;12: e0185315.

Xia S, Ma JX, Wang DQ, Li SZ, Rollinson D, Zhou SS, et al. Economic cost analysis of malaria case management at the household level during the malaria elimination phase in The People’s Republic of China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5:50.

Botto-Menezes C, Bardaji A, Dos Santos CG, Fernandes S, Hanson K, Martinez-Espinosa FE, et al. Costs associated with malaria in pregnancy in the Brazilian Amazon, a low endemic area where Plasmodium vivax predominates. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10: e0004494.

Rashed S, Johnson H, Dongier P, Moreau R, Lee C, Lambert J, et al. Economic impact of febrile morbidity and use of permethrin-impregnated bed nets in a malarious area I: study of demographics, morbidity, and household expenditures associated with febrile morbidity in the Republic of Benin. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:173–80.

Botega LA, Andrade MV, Guedes GR. Brazilian hospitals’ performance: an assessment of the unified health system (SUS). Health Care Manag Sci. 2020;23:443–52.

Morel CM, Thang ND, Xa NX, le Hung X, le Thuan K, Van Ky P, et al. The economic burden of malaria on the household in south-central Vietnam. Malar J. 2008;7:166.

Tawiah T, Asante KP, Dwommoh RA, Kwarteng A, Gyaase S, Mahama E, et al. Economic costs of fever to households in the middle belt of Ghana. Malar J. 2016;15:68.

Tefera DR, Sinkie SO, Daka DW. Economic burden of malaria and associated factors among rural households in Chewaka District, Western Ethiopia. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;12:141–52.

Deressa W, Hailemariam D, Ali A. Economic costs of epidemic malaria to households in rural Ethiopia. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:1148–56.

Ilunga-Ilunga F, Leveque A, Okenge Ngongo L, Tshimungu Kandolo F, Dramaix M. Costs of treatment of children affected by severe malaria in reference hospitals of Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8:1574–83.

Uguru NP, Onwujekwe OE, Uzochukwu BS, Igiliegbe GC, Eze SB. Inequities in incidence, morbidity and expenditures on prevention and treatment of malaria in southeast Nigeria. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2009;9:21.

Chuma JM, Thiede M, Molyneux CS. Rethinking the economic costs of malaria at the household level: evidence from applying a new analytical framework in rural Kenya. Malar J. 2006;5:76.

Onwujekwe O, Hanson K, Uzochukwu B, Ichoku H, Ike E, Onwughalu B. Are malaria treatment expenditures catastrophic to different socio-economic and geographic groups and how do they cope with payment? A study in southeast Nigeria. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:18–25.

Ayieko P, Akumu AO, Griffiths UK, English M. The economic burden of inpatient paediatric care in Kenya: household and provider costs for treatment of pneumonia, malaria and meningitis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2009;7:3.

Onwujekwe O, Uguru N, Etiaba E, Chikezie I, Uzochukwu B, Adjagba A. The economic burden of malaria on households and the health system in Enugu State southeast Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2013;8: e78362.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Attanayake N, Fox-Rushby J, Mills A. Household costs of “malaria” morbidity: a study in Matale district, Sri Lanka. Trop Med Int Health. 2000;5:595–606.

Dalaba MA, Welaga P, Oduro A, Danchaka LL, Matsubara C. Cost of malaria treatment and health seeking behaviour of children under-five years in the Upper West Region of Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2018;13: e0195533.

Gatton ML, Cho MN. Costs to the patient for seeking malaria care in Myanmar. Acta Trop. 2004;92:173–7.

Jackson S, Sleigh AC, Liu XL. Cost of malaria control in China: Henan’s consolidation programme from community and government perspectives. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:653–9.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Moreno-Gutierrez D, Rosas-Aguirre A, Llanos-Cuentas A, Bilcke J, Barboza JL, Hayette MP, et al. Economic costs analysis of uncomplicated malaria case management in the Peruvian Amazon. Malar J. 2020;19:161.

Sicuri E, Davy C, Marinelli M, Oa O, Ome M, Siba P, et al. The economic cost to households of childhood malaria in Papua New Guinea: a focus on intra-country variation. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27:339–47.

Yusuf WA, Yusuf SA, Oladunni OS. Financial burden of malaria treatment by households in Northern Nigeria. Afr J Biomed Res. 2019;22:11–8.

Mustafa MH, Babiker MA. Economic cost of malaria on households during a transmission season in Khartoum State, Sudan. East Mediterr Health J. 2007;13:1298–307.

Fernández García A, Collazo Herrera M, Mendes NP, Hossi JP. Costos directos sanitarios del paludismo en el Hospital Militar Regional de Uíge. Medisur. 2018;16:6–9.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors MVA, KN and GRG thanks to the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the Research Productivity Scholarships.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation [INV003970] and the DECIT/Brazilian Ministry of Health/CNPq [#442842/2019-8]. Under the grant conditions of the Foundation, a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Generic License has already been assigned to the Author Accepted Manuscript version that might arise from this submission.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre of Regional Planning and Development (Cedeplar-UFMG), Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil

Mônica V. Andrade, Kenya Noronha, Bernardo P. C. Diniz, Gilvan Guedes, Lucas R. Carvalho, Valéria A. Silva, André S. Santos & Daniel N. Silva

Centre d’Estudis Demogràfics, CED, Universitat Autònoma B, 08193, Barcelona, Spain

Júlia A. Calazans

Department of Global Health and Population, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, 02115, USA

Marcia C. Castro

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MVA, KN, MCC, and ASS conceived the study. MVA and MCC acquired funding and provided coordination and supervision of the study. MVA, KN, BC, GG, LRC, VS, JC, DNS, and ADS conducted the bibliographic review. MVA, KN, JC, LRC, VS, BC, and DNS performed the screening of the papers. MVA, KN, JC, LRC, VS, BC, and DNS extracted the data of the selected studies. MVA, KN, BPCD, GG, MCC, and ASS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to data analysis and manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Marcia C. Castro .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

PECO search framework.

Additional file 2.

Descriptive system of cost components.

Additional file 3.

Items included in the quality assessment of the included articles.

Additional file 4.

Studies excluded after full-text review and reasons for exclusion.

Additional file 5.

List of included references.

Additional file 6.

Funding sources of studies included in the analysis.

Additional file 7.

Distribution of selected papers according to the type of stratification.

Additional file 8.

Quality assessment of the selected papers.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Andrade, M.V., Noronha, K., Diniz, B.P.C. et al. The economic burden of malaria: a systematic review. Malar J 21 , 283 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-022-04303-6

Download citation

Received : 20 March 2022

Accepted : 25 September 2022

Published : 05 October 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-022-04303-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Economic burden

- Cost analysis

Malaria Journal

ISSN: 1475-2875

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 08 January 2024

Global evidence on the economic effects of disease suppression during COVID-19

- Jonathan T. Rothwell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9251-0029 1 , 2 ,

- Alexandru Cojocaru 3 ,

- Rajesh Srinivasan 1 &

- Yeon Soo Kim ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7757-7858 3

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 78 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1231 Accesses

25 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Development studies

Governments around the world attempted to suppress the spread of COVID-19 using restrictions on social and economic activity. This study presents the first global analysis of job and income losses associated with those restrictions, using Gallup World Poll data from 321,000 randomly selected adults in 117 countries from July 2020 to March 2021. Nearly half of the world’s adult population lost income because of COVID-19, according to our estimates, and this outcome and related measures of economic harm—such as income loss—are strongly associated with lower subjective well-being, financial hardship, and self-reported loss of subjective well-being. Our primary analysis uses a multilevel model with country and month-year levels, so we can simultaneously test for significant associations between both individual demographic predictors of harm and time-varying country-level predictors. We find that an increase of one-standard deviation in policy stringency, averaged up to the time of the survey date, predicts a 0.37 std increase in an index of economic harm (95% CI 0.24–0.51) and a 14.2 percentage point (95% CI 8.3–20.1 ppt) increase in the share of workers experiencing job loss. Similar effect sizes are found comparing stringency levels between top and bottom-quintile countries. Workers with lower-socioeconomic status—measured by within-country income rank or education—were much more likely to report harm linked to the pandemic than those with tertiary education or relatively high incomes. The gradient between harm and stringency is much steeper for workers at the bottom quintiles of the household income distribution than it is for those at the top, which we show with interaction models. Socioeconomic status is unrelated to harm where stringency is low, but highly and negatively associated with harm where it is high. Our detailed policy analysis reveals that school closings, stay-at-home orders, and other economic restrictions were strongly associated with economic harm, but other non-pharmaceutical interventions—such as contact tracing, mass testing, and protections for the elderly were not.

Similar content being viewed by others

Effects of government policies on the spread of COVID-19 worldwide

Hye Won Chung, Catherine Apio, … Taesung Park

COVID-19 restrictions and age-specific mental health—U.S. probability-based panel evidence

Elvira Sojli, Wing Wah Tham, … Michael McAleer

A global analysis of the effectiveness of policy responses to COVID-19

Kwadwo Agyapon-Ntra & Patrick E. McSharry

Introduction

In 2020, governments around the world started putting in place extraordinary policies to mitigate the spread of the coronavirus, including stay-at-home orders, restrictions on travel and gatherings, and closures of schools and workplaces. These policies have been found to be associated with reduced economic activity, in the form of visits to workplaces, parks, restaurants, and non-grocery retail establishments, both in global analyses (Hale et al. 2021 ), and based on detailed evidence from single countries or a subset of countries (Deb et al. 2020 ; Boone and Ladreit 2021 ; Lozano Rojas et al. 2020 ; Aminjonov et al. 2021 ; Carvalho et al. 2021 ; Coibion et al. 2020 ; Gathergood et al. 2021 , including illegal economic activity (Nivette et al. 2021 )). Using U.S. data from early in the pandemic, other scholars have argued that widespread economic disruptions would have happened in the absence of restrictions (Goolsbee and Syverson 2020 ; Forsythe et al. 2020 ; Gupta et al. 2020 ).

Epidemiological theory and empirical evidence suggest that these policies likely reduced the number of deaths (Liu et al. 2021 ; Chernozhukov et al. 2021 ; Violato et al. 2021 ; Qi et al. 2022 ), although given the methodological challenges, the evidence on the causal links between mobility restrictions and COVID-19 mortality is not entirely consistent (Berry et al. 2021 ; Herby et al. 2022 ; Spiegel and Tookes 2022 ). Similarly, public health policies that do not restrict economic activity—such as contact tracing (Fetzer and Graeber 2021 ) and surgical mask use (Abaluck et al. 2022 )—have been found to reduce infections.

Regardless of the causes, pandemic-era economic distress has been widely documented. Global output contracted by 3.4% in 2020, with output contractions observed in 95% of countries, a scale that rivals that of the Great Depression (World Bank 2022 ), and global poverty increased (Mahler et al. 2021 ; Kim et al. 2021 ). Furthermore, low-income countries faced widescale income losses (Egger et al. 2021 ; Josephson et al. 2021 ). Within countries, the economic effects of the pandemic have been worse for households with relatively low socioeconomic status, as measured by income rank or educational attainment (Rothwell and Smith 2021 ; Narayan et al. 2022 ; World Bank 2022 ; Bundervoet et al. 2021 ; Kugler et al. 2021 ), which is consistent with past pandemics (Furceri et al. 2022 ).

This paper contributes to the literature by providing the most comprehensive analysis to-date on several research questions related to the pandemic: How prevalent was the economic harm related to the pandemic, and how did that harm relate to subjective well-being and financial security? What is the association between economic harm and the stringency of regulations on economic and social activity? How did harm vary by socioeconomic status within and across countries? How do estimated effects of stringency compare to alternative non-pharmaceutical interventions in terms of job loss and similar outcomes?

The analysis relies heavily on the Gallup World Poll, which used random samples of individuals in 117 countries representing nearly three-quarters of the global population. From July 2020 to March 2021, the survey collected detailed demographic data on income and education, subjective well-being measures, and information on several economic outcomes in which respondents were explicitly asked if they were caused by the pandemic. The resulting database provides the only harmonized quasi-global database available to study individual and country-level employment and income outcomes. By directly measuring forms of economic harm—rather than proxy measures such as mobility—these data provide insights that would otherwise be lost to history. Data on policy interventions, COVID deaths, and other contextual data were matched to individual responses using cumulative-to-date means, such that a respondent’s self-reported degree of harm from COVID-19 could be compared to the policy regime used up to match the month of the interview. The primary analysis uses multilevel mixed modeling to simultaneously estimate associations with individual demographic characteristics—including socioeconomic status—and time-varying country-level variables, aggregated to month-year units. The database needed to replicate our analysis will be released upon publication, allowing other scholars to use the data for their own novel analyses.

The hypotheses tested in this paper require data on three main components of our empirical models: (i) measures of economic harm or welfare impact; (ii) measures of the stringency of economic restrictions imposed by governments in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, and (iii) measures of the disease burden of COVID-19. These are described in turn in this section. Summary statistics from the country-level and individual data are available in Supplementary Table 1 . The analysis was conducted using Stata 17.0.

Economic harm measures

The main source of data supporting the analysis in this paper comes from surveys fielded by the Gallup World Poll between July 9, 2020, and March 3, 2021, with 321,386 observations of people aged 15 and older in 117 countries/territories. Footnote 1 The survey included demographic information as well as items related to health and well-being that were designed to be nationally representative for each country in the sample. Footnote 2 The relevant ethics statement is provided below.

The main focus of this analysis is on five survey items that broadly measure social or economic harm from COVID-19. The first item, fielded to all survey respondents, solicits an answer to the question, “In general, to what extent has your own life been affected by the coronavirus situation?” We recode responses as a binary variable, which takes a value of one if the response is “a lot,” and zero if respondents reply “some” or “not at all.”

The second item, applicable only to people working at the start of the pandemic, solicits whether respondents have experienced each of the following as a result of the coronavirus situation?

Temporarily stopped working at your job or business

Lost your job or business

Worked less hours at your job or business

Received LESS money than usual from your employer or business

Respondents are instructed to answer “Yes” or “No”, or “Does not apply” if they did not have a job leading up to the pandemic. The World Poll includes a large number of other respondent-level variables, which we only briefly describe below in context. On average, 42% of adults responded that they were affected a lot; 24% reported permanently losing their job; 48% reported a temporary job loss, and 47% reported lost income (see Supplementary Table 9 for full text).

The advantage of the above survey items for the purpose of assessing the welfare impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, vis-à-vis more traditional measures of economic changes, such as employment status or income, stems from the fact that the respondent is asked to attribute the severity of the overall impact, or the different aspects of job and income losses to the pandemic in a causal sense. This is important because many factors other than COVID-19 could cause people to lose their job, leave the labor force or experience emotional stress. Thus, while the analysis in this paper relies on cross-sectional variation, the framing of the key questions related to impacts help at least partially guard against common omitted variable bias concerns in such settings.

A second advantage of these items is that respondents are well-placed to know if an economic change in their life was caused by the pandemic. The event itself was highly salient and often highly disruptive to daily life, with clear time boundaries, tied to events like international and national emergency declarations and stay-at-home orders. In many cases, employers may have specifically told employees that the cause of their layoff was the pandemic, but even in the absence of that messaging, respondents would be well aware of the timing of their job loss and the circumstances leading up to it, which may include the business being shut down or customers canceling contracts or no longer showing up.

Stringency of economic restrictions measures

The analysis relates the above measures of economic harm to the stringency of restrictions on economic activity imposed by governments. We measure stringency of lockdowns by using data from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (Hale et al. 2021 ). The database evaluates national and sub-national government policies along various dimensions.

Data are coded on an ordinal scale, such that values are increasing with stringency. For business closures, 0 means no measures, 1 means recommended closing or recommended work from home, 2 requires the closing of some sectors, and 3 requires the closing of all but essential workplaces, such as healthcare offices and grocery stores. The data are collected for every day since the start of 2020, which facilitates our analysis. Since we are studying the cumulative economic effects up until the time of the survey, we want a measure of the cumulative lockdown up to that point, which we measure as the average stringency up until the month of the survey. Hale et al. ( 2021 ) constructed a “stringency index” that is the mean value of the stringency of the 8 containment policies and one health-related policy. The latter measures the degree to which public officials urged caution through coordinated efforts to promote social distancing and related behavioral changes across traditional and social media (see Supplementary Table 4 for full description). For the purposes of our analysis, we restrict the sample to data collected through March of 2021, to coincide with our sample collection period. We standardize the stringency index and its components to have mean 0 and a standard deviation of one across all 184 countries in the database.

In our decomposition analysis, we focus on these containment measures, as well as “health systems policies” which include regulations of facial coverings, contact tracing, testing, vaccination policy, and protections of the elderly. We omitted investment related policies because they are highly dependent on country budgets and GDP.

In most cases, each country has a single daily measure for each indicator. Sub-national data is available for only Brazil, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States. For these countries, we obtain population data from national statistical offices for the sub-regions and use these as weights, so that the national value is a population-weighted average of the subregional policies. Footnote 3

It should be noted that stringency measures, such as those related to social distancing and restrictions to physical mobility, need not result in economic harm if the degree of compliance is low, either because people are unable or do not want to comply with the measures and the authorities lack the capacity to enforce them. Thus, it is important to ascertain that stringency measures are actually binding and do, in fact, lead to reduced mobility and economic activity. To verify this, we rely on several sources of data that speak to physical mobility and social distancing dynamics (see Supplementary Materials).

One direct way of looking at restrictions to mobility is with the aid of data from Google Community Mobility Reports. Using mobile phone location software, these data show the percentage change in visits to various places from a pre-COVID baseline (January 3 to February 6, 2020). We focus only on visits to retail and restaurants, described by Google LLC ( 2021 ) as: “places like restaurants, cafes, shopping centers, theme parks, museums, libraries, and movie theaters.” Roughly half of the adult population in the sample reported direct contact with non-household members, and visits to restaurants and similar places were down 25% on the average day through the end of 2020.

One additional proxy measure for the degree of social distancing that is directly relevant to COVID-19 transmission is related to changes in the transmission of a parallel respiratory virus that was common before the pandemic. A large drop in the transmission of this parallel virus would suggest major behavioral changes relevant to disease transmission, whereas the absence of change in its transmission would suggest limited behavioral changes. Influenza is close to ideal in providing this analytic opportunity. The most significant problem is that flu cases are measured only based on testing, and flu testing conditional on symptoms—like COVID testing—is likely to vary by country. At the same time, by comparing pre-COVID flu rates to COVID-era flu rates, we control for unchanging country-level testing infrastructure and practices. We, therefore, believe these data provide a valid measure of changes in social distancing that include both policy-induced and non-policy-induced behaviors. These data are from the World Health Organization’s FluNet and include total positive influenza cases per week by country for each year from 2016 to the 45th week of 2021. The use of weekly data allows us to adjust for seasonal effects, which vary by hemisphere and countries within hemispheres. We are interested in the percentage change in weekly cases during flu season before and after the pandemic, ending the analysis on the 12th week of 2021 to coincide with the World Poll data collection period. To identify the flu season for each country, we calculate the weekly share of cases from 2016 to 2019 and classify any week with at least 1% of annual cases as being part of flu season. For the United States, this would include weeks 1–16 and weeks 47 through 52 of every year. For Australia, in the Southern Hemisphere, it would include weeks 20–41. Unfortunately, FluNet data are far from being comprehensive and many countries are either entirely missing or only report a few weeks out of the year. We require 90% reporting coverage during flu-season weeks before and after the pandemic. We find that flu cases in the 2020–2021 flu season were just 18% of the mean number of flu cases measured from 2016 to 2019 flu season in 74 countries.

As part of our robustness checks, we analyze the relationship between stringency and changes in flu rates at the country-month level. For this analysis, we calculate positive flu cases in the current year (2020) relative to the previous year (2019) and the year before that (2018) and take the average of these two rates before aggregating this average to months. This gives us a measure of flu rates relative to previous years that varies by month and country.

We include an additional measure of subjective social distancing. In partnership with Facebook, the University of Maryland fielded a large-scale global daily survey of Facebook users (the COVID-19 World Symptom Survey Data), reweighted to be representative of the national population (Barkay et al. 2020 ). Using the University of Maryland API (Fan et al. 2020 ), we were able to get weighted data for the percentage of respondents who have reported having had direct contact (longer than 1 min) with people not staying with them within the past 24 h. Using data aggregated across 103 countries in 2020, 46% of respondents report direct contact with a standard deviation of 10%.

Disease burden measures

The disease burden is measured in terms of deaths per capita, which is preferable to the number of COVID-19 cases. We do not claim that every national health system is equally likely to capture and correctly identify every COVID-19 death, but nearly every country has formal systems to record the causes of death. By contrast, the probability of seeking testing conditional on the experience of symptoms is highly contingent on factors that vary widely by country, such as cost, guidelines on testing priorities, and the availability of tests. Asymptomatic testing, moreover, also varies widely by country. In short, data on COVID-19 cases per capita are very noisy measures of the disease burden relative to deaths per capita.

To further guard against measurement error—and potential bias stemming from lack of reporting—we include model-based estimates of deaths from COVID-19 in our analysis from the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME 2021 ). That analysis uses actual all-cause mortality data for 56 countries, subtracts out known increases in deaths, and determines estimates of actual COVID deaths. The research team then models the ratio between reported deaths and actual deaths for every country to arrive at a measure of total COVID deaths. We regard these as credible alternative measures of disease burden, as argued by Wang et al. ( 2022 ). IHME is the source for both the official and estimate deaths used in our models.

Details of analysis

Our analysis tests models at the individual and country levels. For individual analysis, we study (1) how experiences of economic harm relate to subjective-well-being outcomes; (2) which demographic variables predict a greater risk of harm; (3) whether the relationship between low-socioeconomic status and harm is higher or lower in countries with high-stringency versus low-stringency.

Predicting well-being

The initial findings test whether our measures of economic harm predict subjective well-being at the individual level. We run linear OLS regression models of the following form, where W is the outcome of interest, θ is a vector of individual i demographic variables, C is an indicator for the country of residence (a country fixed effect) c , and the errors are clustered at the country level to account for within-country-level measurement error. Since respondents answer the survey at different times t , time periods are measured in months, and months fixed effects are included. In this setup, there are no country-level regressors, other than the fixed effect.

Predicting harm in a multilevel framework

The primary analysis combines country-level and individual-level data and therefore uses a multilevel model. We estimate the model using the mixed program in Stata v17, allowing for one unique variance parameter per random effect and maximum likelihood estimation. The variance-covariance matrix is calculated to allow intragroup correlation at the country level, where the data are structured by countries and by month-years, allowing random intercepts that vary by time and country ( \(\beta _{0,c,t}\) in Eq. 2 ). The dependent variable is economic harm H measured at the individual level i in country c during time t (Eq. 2 ). We include country-level time-varying variables, captured in X in (Eq. 4 ). These are cumulative-to-date measures of COVID-19 restrictions, economic support policies, and COVID-19 deaths per capita.

When written out formally, Eq. 2 captures the first-level individual specification. Harm varies by individual, country, and time period and so do the errors, intercepts, and predictors. Equation 3 represents level 2 (the time period). The mean outcome for individuals is modeled as a function of the time period and a random component. The time period mean varies by country, since countries faced different disease and economic trajectories during the pandemic. Level 3 is modeled in Eq. 4 . The mean outcome by country and time period is a function of the mean across all groups, a country and time-varying component, and a random country-varying component. Equation 5 combines the multiple levels into our preferred model. The fixed components are the first three terms, whereas the random components are the final three. The estimation procedure in Stata uses maximum likelihood. This exposition follows the discussion from Tascam Giorgio et al. ( 2009 ) and Oshchepkov and Shirokanova ( 2022 ).

Country-level variables are cumulative-to-date time-varying for several reasons. A single cumulative measure would include information that occurred after measurement for survey respondents who interviewed in early waves, and this would introduce unnecessary error into the model. A time-varying metric that is not cumulative-to-date would be a problem, because the outcome variable measures cumulative harm-to-date, as in “have you ever lost your job as a result of the coronavirus situation?” Since a measure that ignores the past can hardly be expected to predict the past, this approach would also introduce error.

The individual-level measures are demographic indicators for age, gender, foreign-born status, education, income, and urbanicity. We also include an indicator for whether the respondent is out of the labor force at the time of the survey. Since most of our measures of harm involve job loss, they are not usually applicable to those who were out of the labor force, whose lives were less likely to have been affected. We omit current unemployment status because many people recently harmed through job loss or one of the other measures may still be unemployed at the time of the survey.

The results from our baseline model can be used to assess the appropriateness of our multilevel modeling strategy. Both of the random intercepts are significant at 95% confidence levels (see Table 1 ). The country level explains approximately 8.8% of the total variation, whereas the time-period effect is just 0.8%. The intraclass correlations are 8% at the country level and 8.8% combined and both significant, confirming our assumption that individual-level errors are correlated with higher-level errors. The model’s results are reported in Table 1 using the harm index and job loss as the predicted outcomes; results predicting income loss, whether the respondent was affected a lot by the pandemic, temporary job loss, and loss of hours are reported in the Supplemental Materials ( ST5 , ST6 , ST7 , and ST8) .

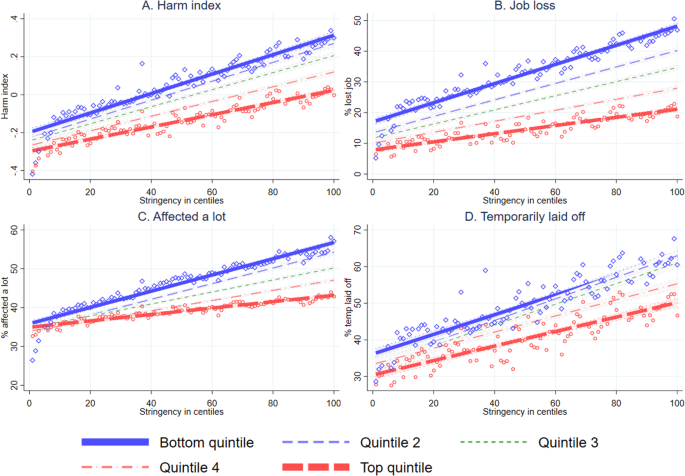

We also report the results of models that interact household income quintile with stringency (Fig. 2 ). These models are identical to our primary specification except they include additional interaction terms along the lines of

where \(\beta _2\) identifies the slope of harm for an income group as stringency increases. Figure 2 plots the mean predicted values from these models for each quintile after collapsing the data to centiles of stringency. Since we are interested in how effects vary by socioeconomic status, we drop educational attainment levels from the model (which is included in our benchmark model), so that the income effects are not conditional on education level. Standard errors are estimated in the plots by regressing the group-specific effect sizes on the stringency centile rank. These approximate the standard errors from the larger database.

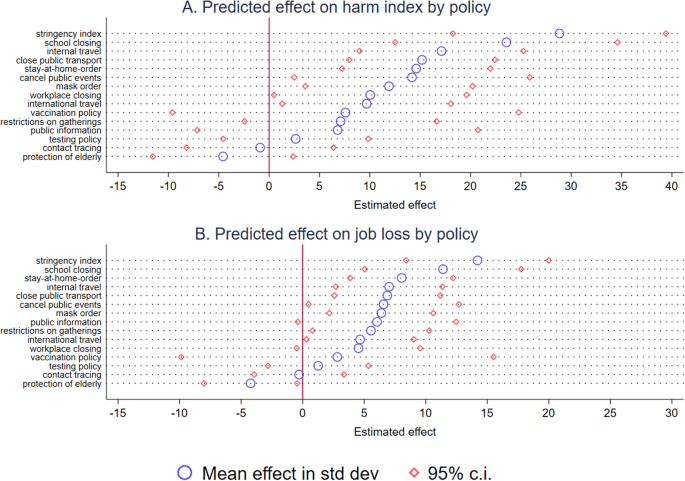

To test the differences between policies, we replicate the analysis from Eq. 5 and Table 1 using our preferred multilevel model and report the coefficients and standard errors (Fig. 3 ).

Summary data

Across the 117 countries included in the Gallup World Poll from July 2020 to March 2021, 42% of adults said they were affected a lot by the pandemic, weighting responses by population. Among those who were in the labor force leading up to the pandemic, 51% were laid off temporarily, 50% lost hours, 49% lost income, and 27% lost their job (see ST3).

These outcomes varied widely by country and continental sub-region. In Eastern Asia, Western Europe, and Northern Europe, only 4.3%, 6.4%, and 6.8% permanently lost their job, respectively, but in Southern and South-eastern Asia it was 49.0% and 44.1%, respectively. In Northern America and Western Asia, 50.1% and 57.4% said their lives were affected a lot. In Western Europe, this was just 29.5%. Meanwhile, cumulative deaths per capita were much higher in Europe and North America relative to Africa and South Asia (ST2), suggesting that the disease burden is unlikely to explain these findings.

A general pattern, found in the data, is that low-income countries experienced a relatively low disease burden from COVID-19 but a high economic burden. This mismatch between the health burden of the pandemic and its social burden suggests an important role for policy. GDP per capita measured in 2019 PPP-adjusted dollars is negatively correlated with the share of population reporting a COVID-related job loss (–0.74), but positively correlated with deaths per capita (0.35) and estimated deaths per capita (0.18), using data from (Wang et al. 2022 ). GDP per capita is also highly correlated with an economic support index (0.55). Yet, GDP per capita has no correlation with the stringency index for disease suppression policies (0.02), even though stringency predicts greater job loss (0.19) and economic support predicts less job loss (–0.40).

Importantly, these relationships would be missed using Google mobility as economic indicators. Visits to restaurants were negatively correlated with GDP per capita (–0.20) and positively correlated with job loss (0.15). In other words, Google data provides the opposite signal as survey-based data. Other Google mobility measures showed the same pattern, including use of transportation and visits to work. It seems that in rich countries, people were able to withdraw from discretionary in-person economic activity—including work—while preserving their jobs and income to a much greater extent than in low-income countries, likely because of the development of digital service markets.

Validating a novel measure of economic harm

Before describing the primary results, we establish grounds for accepting the validity of our key measures. Further information is provided in the Methods section and Supplementary Text. First, we create a “harm index” as the standardized individual-level mean of responses to five survey items about how respondents’ lives have been affected by the coronavirus situation. They are as follows: whether their lives have been affected a lot, whether they lost their job or business temporarily or permanently (two distinct items), whether they worked fewer hours, or whether they received less money. Using the global sample, each item is standardized to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one.

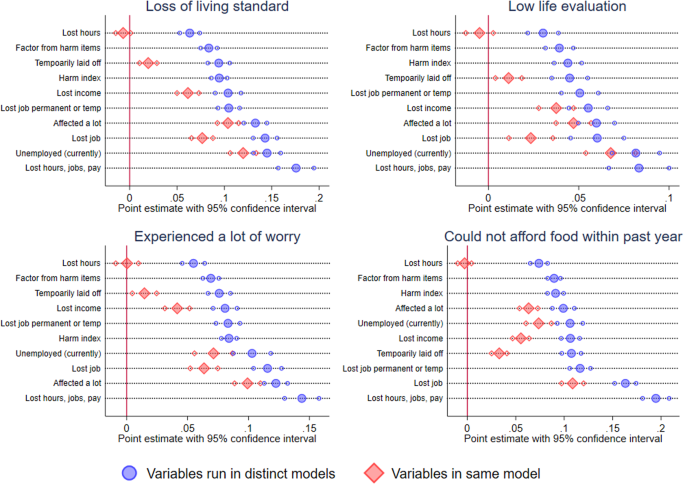

The results show that the economic harm index—and its component parts—strongly predict four measures of subjective well-being, covering (1) changes in subjective living standards, (2) current life evaluation, (3) experiences of worry, and (4) lack of money for food (wording is provided in Supplementary Table 3 ). Essentially, we regress these outcomes on the harm index, controlling for respondent demographics and country fixed effects. Each component of harm is strongly and significantly associated with lower well-being using all four measures. Moreover, when each component of harm is included in the same model, all of them are significant, except for the loss of hours, which is highly correlated with the others. Since each variable adds information, we consider the harm index to be the most comprehensive measure of several dimensions: job loss, income loss, and subjective disruption to life (Fig. 1 ).

Data are from the Gallup World Poll. Analysis includes approximately 222,000 respondents when restricted to the working population, which is used for the economic outcome measures. All models include demographic controls and country effects. The red diamonds show results when all variables, except the harm index, are used in the same model.

We considered several alternative measures of our harm index, including a factor analysis-based index, one that only uses the four labor market items (excluding whether the respondent was affected more generally), and one that combines temporary and permanent layoffs. Based on empirical investigations discussed in the Supplemental Text and summarized in Supplementary Table 10 , our preferred measure is the one used here, though the results reported in Table 1a —testing the association with stringency—are almost exactly the same, when we replace the harm index with these alternatives. Footnote 4

Next, we check the reliability and validity of World Poll data on employment losses against alternative sources. World Poll data on the job loss rate are broadly aligned with administrative data on changes in the official unemployment rate (correlation is 0.52 in 52 countries). Yet, in addition to broader coverage, the World Poll measures are superior in two respects: harmonization in measurement and a causal link with COVID-19. Note, we are not suggesting that this fact implies that our estimators are causal. The point is that respondents are asked to report on an outcome that they believe is causally linked to the pandemic. This is a different question about whether they believe it is causally linked to stringent policies, which is a much harder question. Nonetheless, this is a large conceptual advance over asking whether someone is employed or not and assuming any change from pre- to post-pandemic is caused by the pandemic.

Consider that in normal times, except in rare cases, “unemployment” requires that adults are out of work but seeking and able to work. If the latter two conditions are unmet, the person is considered out of the labor force, but not unemployed. COVID-19, however, resulted in many people losing their job but temporarily halting efforts to find a new one—for various reasons. Statistical offices around the world took different non-harmonized approaches to classifying such persons, resulting in different methodological bases for documenting unemployment rate levels and changes. Moreover, COVID-19 was not the only causal factor affecting social and economic conditions around the world, so the World Poll data also improve conceptual validity by asking respondents to attribute their economic harm to the pandemic and allowing them to express it along several dimensions (see Supplementary Text for further discussion of these issues).

Finally, we show that our primary policy measure also meets basic validity criteria, as discussed in Hale et al. ( 2021 ). Stringency is weakly and positively related to COVID death rates but more closely related to measures of social distancing, particularly those involving declines in visits to restaurants and small businesses (Supplementary Text and Supplementary Fig. 1 ). We examine two additional and related outcomes in the supplement. In more stringent countries, self-reported social contact (available from a non-representative alternative survey covering a smaller number of countries) tends to be lower and reported cases of seasonal flu fell further from baseline season-adjusted trends—for the subset of countries with high-quality flu data. This provides further evidence that the behaviors associated with respiratory disease transmission (e.g., social contact) fell further where disease-suppression policies were strongest, but flu case data are likely more informative than COVID-19 case count data, since flu surveillance systems were well-established before 2020, and COVID surveillance relied on novel tests that were neither available uniformly globally nor across regions within countries. Taken together, this evidence suggests a plausible link between stringency and economic outcomes.

Stringency measures and economic harm: main results

We now proceed with the main research question—whether more stringent restrictions are associated with a greater degree of economic harm, and what demographic factors are most strongly associated with harm. The stringency of mitigation policies is measured by the COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (Hale et al. 2021 ). Harm is aggregated from the World Poll microdata, using sample weights to ensure national representation. The analysis regresses harm on stringency (see Methods) and a vector of demographic variables in a multilevel model, with country and month-year levels.

Column (1) of Table 1a reports the regression-adjusted correlation between policy stringency and an index of economic harm, with no individual-level controls. A one standard deviation increase in the stringency index predicts a 0.31 increase in harm (0.40 for a std deviation unit of harm). Colum (2) adds individual-level demographic controls. The coefficient on harm falls—in absolute value terms—only slightly to 0.29 increase in harm (0.37 std dev). This model includes cumulative-to-date measures of reported COVID-19 deaths per capita and an index of economic support, as well as a rich list of individual-level controls, and country and month effects.