Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

125 Virtue Ethics Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

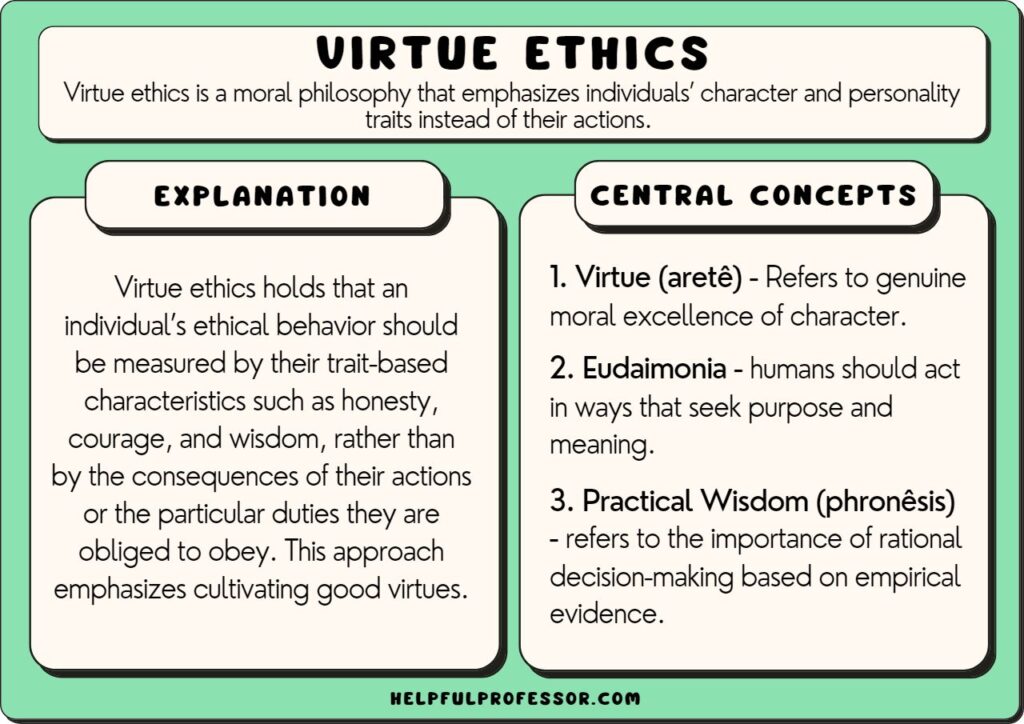

Virtue ethics is a branch of ethics that focuses on the character traits and virtues that lead to a good and fulfilling life. Unlike other ethical theories that focus on rules or consequences, virtue ethics emphasizes the importance of developing good character and cultivating virtues such as honesty, kindness, courage, and wisdom.

If you are studying virtue ethics or simply looking for some inspiration for an essay topic, we have compiled a list of 125 virtue ethics essay topic ideas and examples to help you get started.

- The role of virtue ethics in contemporary society

- The importance of moral character in Aristotle's virtue ethics

- How can virtue ethics help us navigate ethical dilemmas in the workplace?

- The relationship between virtue ethics and happiness

- Virtue ethics vs. deontological ethics: a comparative analysis

- The role of empathy in cultivating virtuous character

- How can we cultivate virtues in ourselves and others?

- The concept of eudaimonia in virtue ethics

- The virtue of courage: examples from history and literature

- How does virtue ethics inform our understanding of friendship?

- The role of practical wisdom in making ethical decisions

- The virtue of generosity: why is it important in a virtuous life?

- Can virtues be taught or are they innate qualities?

- The virtue of honesty: why is it important in personal and professional relationships?

- The ethics of care: how does it align with virtue ethics?

- The virtue of patience: why is it important in a fast-paced world?

- The role of integrity in virtuous character

- The virtue of humility: how can we cultivate it in ourselves?

- The importance of self-awareness in developing virtuous character

- The relationship between virtue ethics and environmental ethics

- The virtue of forgiveness: why is it important for personal growth?

- How can virtue ethics inform our understanding of justice?

- The role of virtue ethics in medical ethics

- The virtue of temperance: how can we practice moderation in a consumerist society?

- The virtue of compassion: why is it important in a virtuous life?

- The relationship between virtue ethics and feminist ethics

- The virtue of gratitude: how can we cultivate a sense of gratitude in our lives?

- The role of courage in facing ethical challenges

- The virtue of loyalty: why is it important in personal and professional relationships?

- The virtue of resilience: how can we bounce back from adversity?

- The virtue of integrity: why is it important in personal and professional relationships?

- The virtue of patience: how can we practice patience in a fast-paced world?

These essay topics and examples should give you a good starting point for exploring virtue ethics and its applications in various aspects of life. Whether you are writing a research paper, a reflective essay, or a case study, virtue ethics provides a rich framework for examining ethical questions and dilemmas from a character-based perspective. Happy writing!

Want to create a presentation now?

Instantly Create A Deck

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Hassle Free

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2023 Pitchgrade

141 Virtue Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best virtue topic ideas & essay examples, 💡 simple & easy virtue essay titles, 🔎 interesting topics to write about virtue, 📌 most interesting virtue topics to write about, 🥇 good research topics about virtue.

- Justice Theory: Business Ethics, Utilitarianism, Rights, Caring, and Virtue The foremost portion of business ethics understands the theory of rights as one of the core principles in the five-item ethical positions that deem essential in the understanding of moral business practices.

- Aristotle vs. Socrates: The Main Difference in the Concept of Virtue One of the main principles on which the ethical school is based is the notion of virtue as the representation of the moral perfectness of a man. We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

- Virtue Theory, Utilitarianism and Deontological Ethics The foundation of utilitarianism theory is in the principle of utility. On the other hand, the theory of deontology embraces the concept of duty.

- Plato and Aristotle’s Views of Virtue in Respect to Education Arguably, Plato and Aristotle’s views of education differ in that Aristotle considers education as a ‘virtue by itself’ that every person must obtain in order to have ‘happiness and goodness in life’, while Plato advocates […]

- Courage as an Important Virtue in Life Described by Maya Angelou as the most important of all the virtues because without courage you cannot practice any other virtue consistently”, it is composed of different types, including physical courage, moral courage, social courage, […]

- Abortion and Virtue Ethics Those who support the right of a woman to an abortion even after the final trimester makes the assertion that the Constitution does not provide any legal rights for a child that is still within […]

- Act Utilitarianism and Virtue Ethics: Pros and Cons Therefore, act utilitarianism is better than virtue ethics since it is clear, concise, and focuses on the majority. Virtue ethics’ strengths can be utilized to enhance the act-utilitarianism theory.

- Niccolo Machiavelli’s Virtue and Fortuna Machiavelli provided opportunities to scholars and readers to understand a political system purged of irrelevant influences of ethics in order to comprehend the basis of politics in useful use of power. Machiavelli introduced another principle […]

- Consequentialist, Deontological, and Virtue Ethics: Ethical Theories Ethical principles are rooted in the ethical theories, and ethicists, when trying to explain a particular action, usually refer to the principles, rather than theories.

- Philosophy: Aristotle on Moral Virtue Both virtue and vice build one’s character and therefore can contribute to the view of happiness. Therefore, character education leads to happiness that is equal to the amount of wisdom and virtue.

- “Virtue Ethics and Adultery” by Raja Halwani In my opinion, that in the context of marriage and adultery, there is a connection between love and sex. According to Halwani, adultery is permissible in situations where the partner does not demonstrate fidelity, including […]

- Machiavelli and Aristotle’s Idea of Virtue He states that for an individual to nurture a certain virtue, one ought to partake in activities that resemble the virtue.

- Desdemona as a Symbol of Christian Virtues She chooses to stay patient when the very light of her life, Othello, accuses her of being a woman of foul character and strikes her.

- “Barbarian Virtues: The United States Encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 1876-1917” by Matthew Frye Jacobson In his own words, Jacobson argues that the country’s “trumpeted greatness” during the Reconstruction and World War I periods was influenced by “the dollars, the labor, and, not least, the very image, of the many […]

- Confidential Data Access: Kantian and Virtue Ethics Governmental agencies reassured the public that all the information is encrypted, but the authors of the article state that there was a place to use confidential documents.

- Greek Manly Virtue in Epic Literature & Philosophy Thus, the manly virtue of ancient Greeks was an attribute of the male and female parts of the society that was implemented since childhood and related to the norms of ethics and aesthetics.

- Virtue Meeting and Live Events Comparison The meeting being of five employees from all over the country, delivery of the context of the meeting is crucial. The next difference is on code of dressing, where in the live events, it is […]

- Without Faith, There Can Be No True Virtue? It relates to the author of integrity and the dishonest virtue that occurs where there is no faith in God even if the qualities of an individual are the best.

- Plato and Socrates on the Ideal Leader’s Virtues In the context of a community, different factors contribute to the definition of this ultimate success. This is important, as people in the community will stand a chance to achieve the higher statuses that they […]

- Theories of Ethics: Virtue, Teleological and Deontological Theory In other words, the shooting might be ethically indefensible due to the lack of adherence to one’s virtues since it is the latter elements which make someone ethical or unethical.

- Virtue Ethics: Kantianism and Utilitarianism Despite the strengths and theoretical significance of both approaches, the theories of Aristotle and Aquinas suggest more flexibility and breadth in ethics interpretation as compared to rule-based theories.

- Difference Between Social Contract, Utilitarianism, Virtue and Deontology This essay gives a description of the differences in how ethical contractarianism, utilitarianism, virtue, and deontological ethics theories address ethics and morality.

- Oprah Winfrey’s Leadership Traits and Virtues This trait underscores the ability of a leader to create a vision on his or her intentions and communicate the same to the individuals involved in making the vision a success.

- Important Virtues in Human Life: Plato’s Protagoras and Hesiod’s Works and Days Plato and Hesiod tried to evaluate the ideas of justice in their worlds and the ways of how people prefer to use their possibilities and knowledge using the story of Prometheus; Plato focused on the […]

- The Importance of Values and Virtues To further illustrate this concept in a more detailed manner, I will refer to a couple of the values I follow, while depicting a situation when I have broken them.

- The Virtue of Courage in Theories and Experience The teachings of the old and the wise seemed buried in the annals of yesteryears. This is courage in the truest sense of the word because it leads to many other virtues.

- Utilitarian, Libertarian, Deontological, and Virtue Ethics Perspectives In deontology, morality is judged through examining the nature of the actions and the will of the individuals to do the right thing.

- Civic Virtue in Crime Commitment and Revelation In the law, as well as in the moral life of society, it is considered that concealment, non-disclosure, and connivance are the types of implications to the crime.

- Knightly Virtue in “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” Poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is an epic poem where the protagonist illustrates knightly virtues through overcoming the trials sent to him by the Green Knight.

- Virtue and Stoic Ethics in Criminal Justice The lack of ethical grounds for the behavior of criminal justice officials makes the application of the law unreliable. As an employee of a juvenile correctional colony, I will be guided by the principles of […]

- Moral Virtue and Its Relation to Happiness Furthermore, Aristotle believed that moral virtue is the primary means to happiness and the most important of all things that are really good for people.

- Leadership: Character, Competencies, and Virtues Therefore, this paper will analyze the relationship between personality and leadership and how it affects the work of other people and the company as a whole.

- Ethics, Prosperity, and Society: Virtue Ethics and Utilitarianism First, due to the heated argument of the superior on duty, they might take out their anger on the trainee, in which case the trainee might be told to either resolve the issue personally or […]

- Moral Virtue and Its Essence in Human Society Thus, moral virtues serve to reconcile individuals’ knowledge of right and wrong with their actions and ways of living. Therefore, moral virtues allow people to live in peace and assist each other to advance while […]

- Communication Skills and Caring Virtues in Nursing Eventually, I realized that the issue had to be addressed as a healthcare issue and consulted several resources in order to determine the medication to use as the means of keeping my memory functioning properly. […]

- Virtue Ethics and Private Morality It can tentatively be characterized as an approach that emphasizes virtues and moral character, as opposed to approaches that emphasize the importance of duties and rules or the consequences of actions.

- Researching the Concept of Moral Virtue As known from The Nicomachean Ethics, some teachers can be rocks that are doomed to fall, and there is no possibility of them changing that fact.

- Natural Law Theory and Virtue Ethics Theory The second step in virtue ethics theory is to look at the agent of the action. Under virtue ethics theory, the action is wrong because it falls to the extreme of excess, and Jones indulges […]

- Elon Mask: Biography and Main Virtues Elon Musk believes that the more time a person has and the smaller his plan, the weaker progress he will achieve. Musk is admired for the many positive traits he brings to his work.

- The Concept of Aristotle’s Virtue Ethics The essence of Aristotle’s doctrine of the mean is that virtue lies in between two extremes, none of which is virtuous on its own.

- Global Economic Justice: The Natural Law and Virtue Ethics Theories The concept of global economic justice presupposes distribution of recourses on account of people’s needs, allowing to avoid the situation when the most significant part of the planet’s resources is concentrated in the hands of […]

- Humility as a Divine Virtue of a Religious Person These words of wisdom imply that the success of learning is not to elevate a person’s ego, but rather teach them humility through enhancing their understanding of the world.

- Virtue Ethics in Institutional Review Boards Virtue ethics is of the view that resolution of the challenges is dependent on the character of the people making the decisions.

- Act Utilitarianism and Virtue Ethics The theory greatly neglects and ignores the happiness of individual because everyone is on the run to be accepted morally to the society and tend to make individuals do what tends to make them happy.

- Virtue and Its Importance in Current Realities Even though Aristotle and Confucius wrote in 300s BC and 400s BC, respectively, the topic of virtue is not archaic; on the contrary, it refers directly to modern realities. This concept reflects a fundamental attitude […]

- Moral Virtues of Stoicism and Early Christianity Early Christians’ demonstration of virtue which includes humility, selflessness, and mercy, also reflects Jesus’s teachings on being meek and merciful to inherit the kingdom of God.

- Organizational Virtue: An Empirical Study of Customers and Employees The initial results of the study were based on the examination of the relationships between the main organizational virtues and other variables through correlation analysis.

- Happiness in Arts: Happiness Through Virtue This way, the premise of the Marble statue resembles that of the portrait of Antisthenes, namely, that happiness is the greatest good and it can be attained by nurturing goodness.

- Virtues of the Modern Secular State The purpose of this paper is to examine the secular virtues promoted by the state in the 21st century. Therefore, the ideas of the secular state and the Christian worldview intersect with the notion of […]

- Modern Secular State and Its Main Virtues Morality is the principal condition for the emergence of the community as well as the grounds for a prosperous society regardless of the time.

- MacIntyre’s After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory Nevertheless, it is possible in the case if the efforts of a secular state and the religious community are combined for finding a compromise between the governmental needs and the Biblical wisdom.

- Hutcheson on Ideas of Beauty and Virtue Review As for the actual proof of its discernment, Hutcheson does not provide it in An Inquiry into the Original of Our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue.

- Meno’s Question About the Virtue: Response of Socrates This is not the only question Meno asks but in all the cases, he fails to begin by defining the basis of his questions.

- Healthcare Virtue and Values It is the dispositional aspect of character. It involves a mixture of emotion and decision made by the individual.

- Ethical Virtues and Vices Thus, virtues are crucial in the lives of individuals as they lead to productive, ethical, and good behaviors. Ethical vices refer to immoral behaviors that lower the integrity of a person and society.

- Virtue Ethics: One Way to Resolve an Ethical Dilemma Other members of the usability team argue that although there was a clear loophole that the external members can choose to exploit so that they can be released from the work that they need to […]

- Wu Zetian and the Ideals of Feminine Virtue Overall, her actions and character provided a contrast to the behavior of women typical for imperial China, and she was equally admired and criticized.

- Character Strengths and Virtues System Views The issues addressed by this project are related to the nature, structure, degree of integrity, dependence on cultural conditions, values, as well as opportunities and ways of developing the character in the most successful way.

- Aristotle’s and Socrates’ Account of Virtue This is manifested in their teachings where Aristotle speaks of virtue as finding a balance between two extremes while Socrates says that virtue is the desire for one to do well in one’s life.

- Generosity as a Learned Virtue The analysis of this study is aimed at studying the perception of generosity and trying to find out if generosity can be learned or it is just an inborn character trait.

- Plato’s “Meno”: On the Nature of Virtue In 95c, the author assumes that Sophists are also not qualified to teach virtue, due to the fact that one of the respected philosophers is quite critical about those who make some promises and believes […]

- Aristotle’s – The Ethics of Virtue Ethics is not a theory of discipline since our inquiry as to what is good for human beings is not just gathering knowledge, but to be able to achieve a unique state of fulfillment in […]

- Philosophy: Is Patriotism a Virtue? Hence, in the above context, patriotism is the feeling that arises from the concerns of the safety of the people of a nation.

- Five Moral Principles of ACA vs. Seven Virtues of Christian Counseling It is clear, however, that the ACA principles advocate a higher degree of autonomy while Christian counseling suggests that the counselor should suffer from the client, not just feel for them.

- Epistemological Argument, Virtue, and Knowledge The point of the paper is not to disprove the argument against descriptivism entirely, but to point out the insufficiency of the existing arguments.

- Aristotle’s Virtue Ethics Analysis When faced with the option of an apple of a muffin, a good person would choose the apple, because the part of the soul that desired the muffin would be controlled by self-control, the part […]

- Virtue Ethics for Dilemmas in Nursing Using this approach in the context of the dilemma in question gives a possibility to analyze the ability of the nurse to reason morally and to exercise the virtue of telling the truth.

- Intellectual Virtues and Cognitive Development For instance, I believe that I have the virtue of curiosity which allows me to be more active in the pursuit of truth and discoveries.

- Noble Cause Corruption and Virtue Ethics The answer lies in the purpose and the implied public image of the police. The role of the policeman is to uphold the law dictated by the government and the constitution of the country.

- Lethal Autonomous Weapons and Virtue Theory Due to the nature of technology, people are taken out of the loop of the operation of these technologies. Due to the automation of machines and their ability to change their code to adapt to […]

- Utilitarianism, Kantianism, Virtue Ethics, Egoism Quote: The amanagers of a corporation must take responsibility to fulfil their duties to their stockholders and to the public’. According to this normative theory, the utility can be described as anything that is related […]

- Ethical Naturalism in Hursthouse’s “On Virtue Ethics” Thus, Hursthouse’s approach to discussing the ethically relevant aspects in the life of human beings with the focus on ethical naturalism is convincing because the philosopher assumes the difference in people who can be good […]

- Aristotle’s Virtue Theory vs. Buddha’s Middle Path The purpose of this paper is to review each of the two theories and develop a comparison between them. This term is in contrast to the paths of extremities described by eternalism and annihilationism that […]

- Mattel Inc.’s Ethical Framework and Virtues However, if it had incorporated the virtue of honesty in its safety and quality codes, the chances are that the product recalls would not have occurred.

- Virtue Ethics, Utilitarianism, and Deontology Utilitarianism relates to the concept of value in that the quality of something which is good is measured by the value attached to it.

- Ethics in Leadership: Role, Conduct and Virtues It is important to know whether the actions of leaders are right or bad. The leader must have the moral right to act and that those actions must be for the well-being of others.

- Ethics: Egoism, Utilitarianism, Care and Virtue It is necessary to note that it is benign most of the time, but the issue is that such behavior may not be liked by other members of society, and it can lead to numerous […]

- Philosophy Terms: Justice, Happiness, Power and Virtue Socrates argues that autocratic leadership is an important structure of ensuring that the rule of law is followed and that the common good of all societal members is enhanced.

- Price Gouging and Virtue: “Justice” by Michael Sandel If one summarizes the information from the book, the virtue can be defined as a somewhat vague idealistic image of the “good” of the correct way of living.

- Ethical Leadership Rules and Virtues Ethical leadership for me is based on such virtues as justice and fidelity which are normally perceived as a part of a leader’s moral identity.

- Cardinal Virtues in The Epic of Gilgamesh The Epic of Gilgamesh enables the reader to identify the cardinal virtues that could be valued in the ancient world. The author of this poem highlights the importance of fortitude through the words of Enkidu […]

- The Confucian Ideal Person: An Introspective on Virtue and Goodness However, merely being able to relate to nature is not enough to become a truly Confucian ideal of a person; according to the postulates of the teacher, one has to reach the state of a […]

- Virtue Ethics and Moral Goods for Society This essay focuses on strengths and or, weaknesses of trying to propose moral goods for a society based on human rights, universal natural law, and claims of Christian faith.

- Is Virtue Ethics Dead in Modern Organizations? In fact, the environment of the global economy often contributes to the evolution of the phenomenon of CSR and the adoption of new responsibilities by the staff due to the cultures fusion.

- Socrates on Death and Virtue This is the purification that comes from the separation of the soul and body. The hindrance to the realization of the true virtue is corrupted by the body and its elements.

- Enhancing Organizational Performance: Virtue Teams The paper will also look at how this investment will contribute to the mission of the bank- to create an environment where the clients expectations and where our values drive the decisions of the bank.

- Business Ethics: Applying Virtue Theory On the price fixing case in question, we are not informed of the character of the major companies that engaged in this action.

- Aristotle’s Definition of Virtue In particular, he writes that virtue is “a state that decides, consisting in a mean, relative to us, which is defined by reference to a reason, that is to say, to the reason by reference […]

- The Knight Without Blemish and Without Reproach: The Color of Virtue Although there is no actual rhyme in the given piece, the way it is structured clearly shows that this is a poem; for instance, the line “At the head sat Bishop Baldwin as Arthur’s guest […]

- Divergence Between False and True Virtue The last days of the Socrates refers to a sequence of four conversations by Plato that illustrates the demise as well as the testing of the Socrates.

- Consequentialistic and Virtue Ethics Wang & Zhang notes that, “the textile industries in the Eastern countries and specifically in China have raised a lot of disputes with the Western countries”. Secondly, the production of cheap textiles by industries in […]

- Examining “The Golden Rule” and Virtue Ethics The ethical issue in this particular case is whether or not Alice should report the apparent mistake in Mark’s nutritional report to the company or whether she should tell Mark that she looked through the […]

- Healthcare Systems Marketing Elements: Sociocultural Factors, Beliefs, and Virtues of a Society In any kind of a business organization, it is very important to have good and healthy relationships with all stakeholders from the employers to employees to customers and all other parties involved in the business […]

- Aristotle’s Ideas on Civic Relationships: Happiness, the Virtues, Deliberation, Justice, and Friendship On building trust at work, employers are required to give minimum supervision to the employees in an effort to make the latter feel a sense of belonging and responsibility.

- Machiavelli and a Notion of Virtue as an Innovation The character qualities that a person has are important to themselves and the people who they are in charge of. Machiavelli wrote about this a long time ago and so, many people of the modern […]

- Montesquieu Practice of Virtue in Ancient Republic The virtue of balancing private and public interests in a republic can more or less be understood in the context of Aristotelian moderation.

- The Virtue of Moving Forward in “A Rose for Emily” by William Faulkner The misery of those who are unable to accept the reality and to get free from the influence of the past is the main theme of William Faulkner’s short story “A Rose for Emily”, where […]

- What Human Virtue Means as Explained in Plato’s Book

- Euthanasia: Perspective From Theory of Personality Virtue

- Using the VIA Classification to Advance a Psychological Science of Virtue

- Consequentialism, Non- Consequentialism, Virtue Ethics and Care Ethics

- Virtue Ethics and Its Understanding of Moral Life

- The Strengths and Weaknesses of Virtue Ethics

- Why the Enlightenment Project Had to Fail According to After Virtue by Alasdair MacIntyre

- East Meets West: Universal Ethic of Virtue for Global Business

- The Virtue Theory and the Ethical Issue of Climate Change

- Aristotle and Virtue: How People View the Virtue of Forgiveness

- Civility and Civic Virtue in Contemporary America

- Difference Between Virtue Ethics, Kantian and Utilitarianism

- Adam Smith and the Character of Virtue Adam Smith and the Economy of the Passions

- Aristotle’s Concept and Definition of Happiness and Virtue

- Utilitarianism, Deontology, and Virtue Theory

- Forms, Immortal Soul, and Defining Virtue in Phaedo and Meno by Plato

- Comparing Confucius’ and Aristotle’s Perspectives on Virtue

- How Aristotle Understands the Human Being Through Virtue Ethics

- Aristotle and Citizenship Intellectual Virtue

- The Relationship Between Desire and Virtue

- Courage, Virtue, and the Immortality of the Soul: According to Socrates

- War Theory, Utilitarianism, and Virtue Ethics

- Analyzing Preference for Virtue Ethics Theory

- Aristotole’s View That Virtue Is the Ability to Know Good and Do Good

- Dialogue Between Aristotle, Plato, and Socrates on Virtue and Vice in Daily Life

- The Meaning and Impact of Virtue From the Perspective of Plato

- Changing Attitudes Toward Virtue in Ancient Greece

- Civic Virtue, the American Founding, and Federalism

- Catholic Social Teachings and Virtue Ethics

- Virtue: Comparing the Views of Confucius and Aristotle

- Can Individual Virtue Survive Corporate Pressure

- Dante and Melville: Flawed Virtue, Truth and Justice

- Virtue Ethics and the Great Role Model of Folklore and Language

- Virtue and the Political Thinking of Niccolo Machiavelli

- Virtue Theory, Utilitarianism, and Deontological Ethics: Differences & Similarities

- Ancient Greece and Changing Attitudes Regarding Virtue

- Businesses Are Completely Incompatible With Virtue Ethics

- Modern Human Behavior and Theory of Classical Virtue

- The Philosophical and Moral Component of Virtue Ethics

- Analyzing the Style and Virtue of the Declaration of Independence

- Divine Command Theory, Deontology, and Virtue Ethics

- The Topic Animal Rights in Society as Discussed in the Virtue Theory

- Why Ethics and Virtue Are Important in Leadership

- Benjamin Franklin and the Virtue of Humility

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 2). 141 Virtue Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/virtue-essay-topics/

"141 Virtue Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 2 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/virtue-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '141 Virtue Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 2 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "141 Virtue Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/virtue-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "141 Virtue Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/virtue-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "141 Virtue Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." March 2, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/virtue-essay-topics/.

- Ethics Ideas

- Aristotle Titles

- Charity Ideas

- Altruism Ideas

- Morality Research Ideas

- Philanthropy Paper Topics

- Hope Research Topics

- Theology Topics

- Moral Development Essay Topics

- Honesty Essay Ideas

- Ethical Dilemma Titles

- Forgiveness Essay Ideas

- Tolerance Essay Ideas

- Bible Questions

- Moral Dilemma Paper Topics

- Register or Log In

- 0) { document.location='/search/'+document.getElementById('quicksearch').value.trim().toLowerCase(); }">

Chapter 10 Essay Questions

1. How does the approach of virtue ethics differ from that of the moral theories discussed in previous chapters? In what ways is this difference important to how we assess the plausibility of virtue ethics? Do you think the virtue ethical approach is the right one? Defend your answers.

2. What are virtues, and how (according to virtue ethics) do we acquire them? Do you find this story plausible? Do you think it makes sense of who the moral exemplars are, and why they are role models? Defend your answers.

3. Write an essay explaining the priority problem for virtue ethics, illustrating the problem with at least one example. Does this objection succeed in refuting virtue ethics? Why or why not?

4. What does Aristotle mean when he says that “virtue is a kind of mean”? Do you find this claim plausible? Does it help us to understand how to live our lives? Explain and defend your response.

5. Write an essay discussing Aristotle’s conception of virtue. What exactly is a virtue, according to Aristotle? Give an example of a virtue and explain why it is a virtue, in Aristotle's view. Is his account plausible? Why or why not?

Select your Country

1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Philosophy, One Thousand Words at a Time

Virtue Ethics

Author: David Merry Category: Ethics , Historical Philosophy Word Count: 1000

Listen here

Think of the (morally) best person you know. It could be a friend, parent, teacher, religious leader, thinker, or activist.

The person you thought of is probably kind, brave, and wise. They are probably not greedy, cruel, or foolish.

The first list of ‘character traits’ ( kind, brave, etc.) are virtues, and the second list ( arrogant, greedy, etc.) are vices . Virtues are ways in which people are good; vices are ways in which people are bad.

This essay presents virtue ethics, a theory that sees virtues and vices as central to understanding who we should be, and what we should do.

1. Virtue and Happiness

Virtues are excellent traits of character. [1] They shape how we act, think, and feel. They make us who we are. Virtues are acquired through good habits, over a long period of time.

1.1. Eudaimonia

According to Aristotle (384-322 BCE) virtues are those, and only those, character traits we need to be happy. [2] Many virtue ethicists today agree. [3] These virtue ethicists are called eudaimonists, after the Greek word eudaimonia, usually translated as “happiness,” “flourishing,” or “well-being . ” [4]

For eudaimonists, happiness is more than a feeling: it involves living well with others and pursuing worthwhile goals. This includes cultivating strong relationships, and succeeding at such projects as raising a family, fighting for justice, and (moderate yet enthusiastic) enjoyment of pleasure. [5]

Eudaimonists believe our happiness is not easily separated from that of other people. Many would consider the happiness of their friends and family as part of their own. Eudaimonists may extend this to complete strangers, and non-human animals. Similarly for causes or ideals: eudaimonists believe complicity in injustice and deceit reduces a person’s happiness. , [6]

If eudaimonists are right about happiness, then it is plausible that we need virtues such as honesty, kindness, gratitude and justice to be happy. This is not to say that the virtues will guarantee happiness. But eudaimonists believe we cannot be truly happy without them.

One concern is that vicious people often seem happy. For example, dictators live in palaces, apparently rather pleasantly. Eudaimonists may not think this amounts to happiness, but many would disagree. And if dictators can be happy, then we certainly can be happy without the virtues. Answering this objection is an ongoing project for eudaimonists. [7]

1.2. Emotion, Intelligence, and Developing Virtue

Eudaimonists believe emotions are essential to happiness, and that our emotions are shaped by our habits. Good emotional habits are a question of balance.

For example, eudaimonists argue that honest people habitually want to and enjoy telling the truth, but not so much that they will ignore all other considerations–a habit of enjoying pointing out other people’s shortcomings will leave us friendless, and so is not part of honesty. [8]

Because virtue requires balancing competing considerations, such as telling the truth and considering other people’s feelings, virtue also requires experience in making moral decisions. Virtue ethicists call this intellectual ability practical intelligence, or wisdom. [9]

2. Virtue and Right Action

Virtue ethicists believe we can use virtue to understand how we should act, or what makes actions right.

According to some virtue ethicists, an action is right if, and only if, it is what a virtuous person would characteristically do under the circumstances. [10] On rare occasions, virtuous people do the wrong thing. But this is not acting characteristically.

2.1. Being Specific

“Do what virtuous people would do” is not very specific, and we may be left wondering what the theory is actually saying we should do.

One way to make it more specific is to generate rules for each of the virtues and vices, called “v-rules.” Two examples of v-rules are: be kind, don’t be cruel. The v-rules give specific guidance in many cases: writing an email just to hurt someone’s feelings is cruel, so don’t do it. [11]

Unfortunately, the virtues can conflict: if a friend asks whether we like their new partner, it may be more honest to say we do not , but kinder to say we do. In this case it is hard to say what the virtuous person would do.

Virtue ethicists might respond that other ethical theories will also struggle to give clear guidance in hard cases. [12]

Second, they might try to understand how a virtuous person would think about the situation. Remember that virtuous people have practical intelligence, and habitually care about other people’s happiness and telling the truth. So they may consider a lot of particular details, including how close the friendship is, how bad the partner is, how gently the friend may be told. [13]

This may not provide a specific answer, but virtue ethicists hope they can at least provide a helpful model for thinking about hard cases. [14]

2.2. Explaining Why

We have seen how virtue ethics tells us what to do. But we also want to know why we should do it.

Virtue ethicists point out that if we ask virtuous people, they will explain why they did what they did. [15] Their reasoning results from their excellent emotional habits and practical intelligence–that is, from their virtue. And if we want to be happy, we need to cultivate virtue. So these should be our reasons too.

But in explaining their decision, the virtuous person won’t necessarily mention virtue. They might, for example, say, “I wanted to avoid hurting their feelings, so I told the truth gently.” [16]

It might then seem that something other than virtue–in our example, the importance of other people’s feelings–explains why the action is right . But then this other thing should be central to ethical theory, instead of virtue.

Virtue ethicists may respond that the moral weight of this other thing depends on which character traits are virtues. Accordingly, if kindness were not a virtue, there may be no moral reason to care about others’ feelings. [17]

3. Conclusion

Virtue ethicists recommend reflecting on the character traits we need to be happy. They hope this will help us make better moral decisions. Virtue ethics may not always yield clear answers, but perhaps acknowledging moral uncertainty is not a vice.

[1] Others may define virtue as admirable or merely good traits of character. For additional definitions of virtue and understandings of virtue ethics, see Hursthouse and Pettigrove’s “Virtue Ethics.”

[2] Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics , Book One, Chapter 9, Lines 1099b25-29. For this interpretation, see Nussbaum, The Fragility of Goodness, p. 6.

[3] Hursthouse, On Virtue Ethics , pp. 165-169, “Virtue Theory and Abortion”, p. 226, Foot, Natural Goodness , pp. 99-116.

There are many other accounts of virtue worth considering. One major alternative is sentimentalist accounts, such as that of Hume and Zagbzebski, who define virtues as those character traits that attract love or admiration. Some scholars argue that Confucian ethics is a virtue ethic, though this is debated: see Wong, “Chinese Ethics.” Also see John Ramsey’s Mengzi’s Moral Psychology, Part 1: The Four Moral Sprouts . For an African understanding of virtue, see Thaddeus Metz’s The African Ethic of Ubuntu .

[4] Hursthouse has a detailed and accessible discussion of the merits of different translations of eudaimonia in On Virtue Ethics, pp. 9-10.

[5] Some people find this account of virtue surprising because they think virtue must involve sacrificing one’s own happiness for the sake of other people, and living like a saint, a monk, or just being a really boring and miserable person. In this case it may be more helpful to think in terms of ‘good character’ than ‘virtue’. David Hume amusingly argued that some alleged virtues, such as humility, celibacy, silence, and solitude, were vices. See his Enquiry 9.1.

[6] The idea that injustice erodes everybody’s happiness is not to deny that it especially harms people who are treated unjustly. However, eudaimonists consider being unjust, or deceiving others to be bad for us.

[7] For a compelling discussion of this objection to eudaimonism, see Blackburn, Being Good, pp. 112-118 . Eudaimonists have been trying to answer this objection for a long time. Indeed, arguing that it is more beneficial to be just than unjust is one of the major themes of Plato’s Republic. For more recent attempts to make the case, see Hursthouse’s On Virtue Ethics, Chapter 8, or Foot, Natural Goodness, especially Chapter 7. See also Kiki Berk’s Happiness .

[8] The idea that the virtues involve finding a balance is called ‘the doctrine of the mean.’ See Nicomachean Ethics, Book II, Chapter 6, lines 1106b30-1107a5. For one contemporary account of the emotional aspects of virtue, see Hursthouse’s On Virtue Ethics, pp.108-121.

[9] Aristotle discusses practical intelligence in Nicomachean Ethics Book 6. For a contemporary account see Hursthouse’s On Virtue Ethics, pp. 59-62.

[10] Hursthouse, On Virtue Ethics, pp. 28-29. This is sometimes called a qualified-agent account. For some alternatives, see van Zyl’s “Virtue Ethics and Right Action”.

[11] Hursthouse, On Virtue Ethics, pp. 28-29.

[12] For other moral theories, see Deontology: Kantian Ethics by Andrew Chapman and Introduction to Consequentialism by Shane Gronholz. When reading, you might consider whether these theories would give you clearer guidance about your friend’s partner.

[13] See Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, Book 2, chapter 9, lines 1109a25-30. Hursthouse, On Virtue Ethics pp. 128-129.

[14] For two examples of how virtue ethics may be helpfully applied to tough moral decisions, see Hursthouse’s “Virtue Theory and Abortion”, and Foot’s “Euthanasia”.

[15] Hursthouse, “Virtue Ethics and Abortion”, especially p. 227, pp. 234-237. “Do what a virtuous person would do” is only supposed to tell us what we should do, not how we should think .

[16] This objection is discussed in Shafer-Landau’s The Fundamentals of Ethics, pp. 272-274.

[17] On this connection between facts about morality on facts about virtue and human happiness, see Hursthouse “Virtue Theory and Abortion”, pp. 236-238.

Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics . C. 355-322 BCE. Trans. Roger Crisp. Cambridge UP. 2014.

Blackburn, S. Being Good. Oxford UP. 2001.

Boxill, B. “How Injustice Pays.” Philosophy and Public Affairs, 9(4): 359-371. 1980.

Foot, P. Natural Goodness. Oxford UP. 2001.

Foot, P. “Euthanasia”. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 6(2): 85–112. 1977.

Foot, P. “Moral Beliefs.” Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 59: 83-104. 1958.

Hume, An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals. 1777.

Hursthouse, R. “Virtue Theory and Abortion.” Philosophy & Public Affairs . 20(3): 223-246. 1991.

Hursthouse, R. On Virtue Ethics. Oxford UP. 1999.

Hursthouse, Rosalind and Glen Pettigrove, “Virtue Ethics”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2018 Edition), Zalta, E.N (ed.). 2018,

Nussbaum, M. The Fragility of Goodness. Cambridge UP. 2nd Edition, 2001.

van Zyl, L. “Virtue Ethics and Right Action”. In Russell, D. C (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Virtue Ethics. Cambridge UP. 2013.

Plato. Republic. C. 375 BCE. Trans. Paul Shorey. Harvard UP. 1969.

Shafer-Landau, R. The Fundamentals of Ethics . Fourth Edition. Oxford UP. 2017.

Wong, D. “Chinese Ethics”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2021 Edition) . Zalta, E.N (ed). 2021.

Zagzebski, L.T. Exemplarist Moral Theory. Oxford UP. 2017.

Related Essays

Happiness by Kiki Berk

Deontology: Kantian Ethics by Andrew Chapman

Introduction to Consequentialism by Shane Gronholz

G. E. M. Anscombe’s “Modern Moral Philosophy” by Daniel Weltman

Philosophy as a Way of Life by Christine Darr

Ethical Egoism by Nathan Nobis

Why be Moral? Plato’s ‘Ring of Gyges’ Thought Experiment by Spencer Case

Situationism and Virtue Ethics by Ian Tully

Ancient Cynicism: Rejecting Civilization and Returning to Nature by G. M. Trujillo, Jr.

Mengzi’s Moral Psychology, Part 1: The Four Moral Sprouts by John Ramsey

Mengzi’s Moral Psychology, Part 2: The Cultivation Analogy by John Ramsey

The African Ethic of Ubuntu by Thaddeus Metz

PDF Download

Download this essay in PDF .

About the Author

David Merry’s research is mostly about ethics and dialectic in ancient Greek and Roman philosophy, although he also occasionally works on contemporary ethics and philosophy of medicine. He received a Ph.D. from the Humboldt University of Berlin, and an M.A in philosophy from the University of Auckland. He is co-editor of Essays on Argumentation in Antiquity . He offers interactive, discussion-based online philosophy classes and maintains a blog at Kayepos.com .

Follow 1000-Word Philosophy on Facebook and Twitter and subscribe to receive email notifications of new essays at 1000WordPhilosophy.com

Share this:, 21 thoughts on “ virtue ethics ”.

- Pingback: Philosophy as a Way of Life – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Ancient Cynicism: Rejecting Civilization and Returning to Nature – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Aristotle on Friendship: What Does It Take to Be a Good Friend? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Ursula Le Guin’s “The Ones who Walk Away from Omelas”: Would You Walk Away? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: G. E. M. Anscombe’s “Modern Moral Philosophy” – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Why be Moral? Plato’s ‘Ring of Gyges’ Thought Experiment – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Article on Virtue Ethics at 1000-Word Philosophy - Kayepos: Philosophical Capers

- Pingback: - Kayepos: Philosophical Capers

- Pingback: Online Philosophy Resources Weekly Update | Daily Nous

- Pingback: Rousseau on Human Nature: “Amour de soi” and “Amour propre” – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: What Is It To Love Someone? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Because God Says So: On Divine Command Theory – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Consequentialism and Utilitarianism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Deontology: Kantian Ethics – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Happiness: What is it to be Happy? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Indoctrination: What is it to Indoctrinate Someone? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: The African Ethic of Ubuntu – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Situationism and Virtue Ethics – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Mengzi’s Moral Psychology, Part 2: The Cultivation Analogy – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Mengzi’s Moral Psychology, Part 1: The Four Moral Sprouts – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Is it Wrong to Believe Without Sufficient Evidence? W.K. Clifford’s “The Ethics of Belief” – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Comments are closed.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Virtue Ethics

Virtue ethics is currently one of three major approaches in normative ethics. It may, initially, be identified as the one that emphasizes the virtues, or moral character, in contrast to the approach that emphasizes duties or rules (deontology) or that emphasizes the consequences of actions (consequentialism). Suppose it is obvious that someone in need should be helped. A utilitarian will point to the fact that the consequences of doing so will maximize well-being, a deontologist to the fact that, in doing so the agent will be acting in accordance with a moral rule such as “Do unto others as you would be done by” and a virtue ethicist to the fact that helping the person would be charitable or benevolent.

This is not to say that only virtue ethicists attend to virtues, any more than it is to say that only consequentialists attend to consequences or only deontologists to rules. Each of the above-mentioned approaches can make room for virtues, consequences, and rules. Indeed, any plausible normative ethical theory will have something to say about all three. What distinguishes virtue ethics from consequentialism or deontology is the centrality of virtue within the theory (Watson 1990; Kawall 2009). Whereas consequentialists will define virtues as traits that yield good consequences and deontologists will define them as traits possessed by those who reliably fulfil their duties, virtue ethicists will resist the attempt to define virtues in terms of some other concept that is taken to be more fundamental. Rather, virtues and vices will be foundational for virtue ethical theories and other normative notions will be grounded in them.

We begin by discussing two concepts that are central to all forms of virtue ethics, namely, virtue and practical wisdom. Then we note some of the features that distinguish different virtue ethical theories from one another before turning to objections that have been raised against virtue ethics and responses offered on its behalf. We conclude with a look at some of the directions in which future research might develop.

1.2 Practical Wisdom

2.1 eudaimonist virtue ethics, 2.2 agent-based and exemplarist virtue ethics, 2.3 target-centered virtue ethics, 2.4 platonistic virtue ethics, 3. objections to virtue ethics, 4. future directions, other internet resources, related entries, 1. preliminaries.

In the West, virtue ethics’ founding fathers are Plato and Aristotle, and in the East it can be traced back to Mencius and Confucius. It persisted as the dominant approach in Western moral philosophy until at least the Enlightenment, suffered a momentary eclipse during the nineteenth century, but re-emerged in Anglo-American philosophy in the late 1950s. It was heralded by Anscombe’s famous article “Modern Moral Philosophy” (Anscombe 1958) which crystallized an increasing dissatisfaction with the forms of deontology and utilitarianism then prevailing. Neither of them, at that time, paid attention to a number of topics that had always figured in the virtue ethics tradition—virtues and vices, motives and moral character, moral education, moral wisdom or discernment, friendship and family relationships, a deep concept of happiness, the role of the emotions in our moral life and the fundamentally important questions of what sorts of persons we should be and how we should live.

Its re-emergence had an invigorating effect on the other two approaches, many of whose proponents then began to address these topics in the terms of their favoured theory. (One consequence of this has been that it is now necessary to distinguish “virtue ethics” (the third approach) from “virtue theory”, a term which includes accounts of virtue within the other approaches.) Interest in Kant’s virtue theory has redirected philosophers’ attention to Kant’s long neglected Doctrine of Virtue , and utilitarians have developed consequentialist virtue theories (Driver 2001; Hurka 2001). It has also generated virtue ethical readings of philosophers other than Plato and Aristotle, such as Martineau, Hume and Nietzsche, and thereby different forms of virtue ethics have developed (Slote 2001; Swanton 2003, 2011a).

Although modern virtue ethics does not have to take a “neo-Aristotelian” or eudaimonist form (see section 2), almost any modern version still shows that its roots are in ancient Greek philosophy by the employment of three concepts derived from it. These are arête (excellence or virtue), phronesis (practical or moral wisdom) and eudaimonia (usually translated as happiness or flourishing). (See Annas 2011 for a short, clear, and authoritative account of all three.) We discuss the first two in the remainder of this section. Eudaimonia is discussed in connection with eudaimonist versions of virtue ethics in the next.

A virtue is an excellent trait of character. It is a disposition, well entrenched in its possessor—something that, as we say, goes all the way down, unlike a habit such as being a tea-drinker—to notice, expect, value, feel, desire, choose, act, and react in certain characteristic ways. To possess a virtue is to be a certain sort of person with a certain complex mindset. A significant aspect of this mindset is the wholehearted acceptance of a distinctive range of considerations as reasons for action. An honest person cannot be identified simply as one who, for example, practices honest dealing and does not cheat. If such actions are done merely because the agent thinks that honesty is the best policy, or because they fear being caught out, rather than through recognising “To do otherwise would be dishonest” as the relevant reason, they are not the actions of an honest person. An honest person cannot be identified simply as one who, for example, tells the truth because it is the truth, for one can have the virtue of honesty without being tactless or indiscreet. The honest person recognises “That would be a lie” as a strong (though perhaps not overriding) reason for not making certain statements in certain circumstances, and gives due, but not overriding, weight to “That would be the truth” as a reason for making them.

An honest person’s reasons and choices with respect to honest and dishonest actions reflect her views about honesty, truth, and deception—but of course such views manifest themselves with respect to other actions, and to emotional reactions as well. Valuing honesty as she does, she chooses, where possible to work with honest people, to have honest friends, to bring up her children to be honest. She disapproves of, dislikes, deplores dishonesty, is not amused by certain tales of chicanery, despises or pities those who succeed through deception rather than thinking they have been clever, is unsurprised, or pleased (as appropriate) when honesty triumphs, is shocked or distressed when those near and dear to her do what is dishonest and so on. Given that a virtue is such a multi-track disposition, it would obviously be reckless to attribute one to an agent on the basis of a single observed action or even a series of similar actions, especially if you don’t know the agent’s reasons for doing as she did (Sreenivasan 2002).

Possessing a virtue is a matter of degree. To possess such a disposition fully is to possess full or perfect virtue, which is rare, and there are a number of ways of falling short of this ideal (Athanassoulis 2000). Most people who can truly be described as fairly virtuous, and certainly markedly better than those who can truly be described as dishonest, self-centred and greedy, still have their blind spots—little areas where they do not act for the reasons one would expect. So someone honest or kind in most situations, and notably so in demanding ones, may nevertheless be trivially tainted by snobbery, inclined to be disingenuous about their forebears and less than kind to strangers with the wrong accent.

Further, it is not easy to get one’s emotions in harmony with one’s rational recognition of certain reasons for action. I may be honest enough to recognise that I must own up to a mistake because it would be dishonest not to do so without my acceptance being so wholehearted that I can own up easily, with no inner conflict. Following (and adapting) Aristotle, virtue ethicists draw a distinction between full or perfect virtue and “continence”, or strength of will. The fully virtuous do what they should without a struggle against contrary desires; the continent have to control a desire or temptation to do otherwise.

Describing the continent as “falling short” of perfect virtue appears to go against the intuition that there is something particularly admirable about people who manage to act well when it is especially hard for them to do so, but the plausibility of this depends on exactly what “makes it hard” (Foot 1978: 11–14). If it is the circumstances in which the agent acts—say that she is very poor when she sees someone drop a full purse or that she is in deep grief when someone visits seeking help—then indeed it is particularly admirable of her to restore the purse or give the help when it is hard for her to do so. But if what makes it hard is an imperfection in her character—the temptation to keep what is not hers, or a callous indifference to the suffering of others—then it is not.

Another way in which one can easily fall short of full virtue is through lacking phronesis —moral or practical wisdom.

The concept of a virtue is the concept of something that makes its possessor good: a virtuous person is a morally good, excellent or admirable person who acts and feels as she should. These are commonly accepted truisms. But it is equally common, in relation to particular (putative) examples of virtues to give these truisms up. We may say of someone that he is generous or honest “to a fault”. It is commonly asserted that someone’s compassion might lead them to act wrongly, to tell a lie they should not have told, for example, in their desire to prevent someone else’s hurt feelings. It is also said that courage, in a desperado, enables him to do far more wicked things than he would have been able to do if he were timid. So it would appear that generosity, honesty, compassion and courage despite being virtues, are sometimes faults. Someone who is generous, honest, compassionate, and courageous might not be a morally good person—or, if it is still held to be a truism that they are, then morally good people may be led by what makes them morally good to act wrongly! How have we arrived at such an odd conclusion?

The answer lies in too ready an acceptance of ordinary usage, which permits a fairly wide-ranging application of many of the virtue terms, combined, perhaps, with a modern readiness to suppose that the virtuous agent is motivated by emotion or inclination, not by rational choice. If one thinks of generosity or honesty as the disposition to be moved to action by generous or honest impulses such as the desire to give or to speak the truth, if one thinks of compassion as the disposition to be moved by the sufferings of others and to act on that emotion, if one thinks of courage as mere fearlessness or the willingness to face danger, then it will indeed seem obvious that these are all dispositions that can lead to their possessor’s acting wrongly. But it is also obvious, as soon as it is stated, that these are dispositions that can be possessed by children, and although children thus endowed (bar the “courageous” disposition) would undoubtedly be very nice children, we would not say that they were morally virtuous or admirable people. The ordinary usage, or the reliance on motivation by inclination, gives us what Aristotle calls “natural virtue”—a proto version of full virtue awaiting perfection by phronesis or practical wisdom.

Aristotle makes a number of specific remarks about phronesis that are the subject of much scholarly debate, but the (related) modern concept is best understood by thinking of what the virtuous morally mature adult has that nice children, including nice adolescents, lack. Both the virtuous adult and the nice child have good intentions, but the child is much more prone to mess things up because he is ignorant of what he needs to know in order to do what he intends. A virtuous adult is not, of course, infallible and may also, on occasion, fail to do what she intended to do through lack of knowledge, but only on those occasions on which the lack of knowledge is not culpable. So, for example, children and adolescents often harm those they intend to benefit either because they do not know how to set about securing the benefit or because their understanding of what is beneficial and harmful is limited and often mistaken. Such ignorance in small children is rarely, if ever culpable. Adults, on the other hand, are culpable if they mess things up by being thoughtless, insensitive, reckless, impulsive, shortsighted, and by assuming that what suits them will suit everyone instead of taking a more objective viewpoint. They are also culpable if their understanding of what is beneficial and harmful is mistaken. It is part of practical wisdom to know how to secure real benefits effectively; those who have practical wisdom will not make the mistake of concealing the hurtful truth from the person who really needs to know it in the belief that they are benefiting him.

Quite generally, given that good intentions are intentions to act well or “do the right thing”, we may say that practical wisdom is the knowledge or understanding that enables its possessor, unlike the nice adolescents, to do just that, in any given situation. The detailed specification of what is involved in such knowledge or understanding has not yet appeared in the literature, but some aspects of it are becoming well known. Even many deontologists now stress the point that their action-guiding rules cannot, reliably, be applied without practical wisdom, because correct application requires situational appreciation—the capacity to recognise, in any particular situation, those features of it that are morally salient. This brings out two aspects of practical wisdom.

One is that it characteristically comes only with experience of life. Amongst the morally relevant features of a situation may be the likely consequences, for the people involved, of a certain action, and this is something that adolescents are notoriously clueless about precisely because they are inexperienced. It is part of practical wisdom to be wise about human beings and human life. (It should go without saying that the virtuous are mindful of the consequences of possible actions. How could they fail to be reckless, thoughtless and short-sighted if they were not?)

The second is the practically wise agent’s capacity to recognise some features of a situation as more important than others, or indeed, in that situation, as the only relevant ones. The wise do not see things in the same way as the nice adolescents who, with their under-developed virtues, still tend to see the personally disadvantageous nature of a certain action as competing in importance with its honesty or benevolence or justice.

These aspects coalesce in the description of the practically wise as those who understand what is truly worthwhile, truly important, and thereby truly advantageous in life, who know, in short, how to live well.

2. Forms of Virtue Ethics

While all forms of virtue ethics agree that virtue is central and practical wisdom required, they differ in how they combine these and other concepts to illuminate what we should do in particular contexts and how we should live our lives as a whole. In what follows we sketch four distinct forms taken by contemporary virtue ethics, namely, a) eudaimonist virtue ethics, b) agent-based and exemplarist virtue ethics, c) target-centered virtue ethics, and d) Platonistic virtue ethics.

The distinctive feature of eudaimonist versions of virtue ethics is that they define virtues in terms of their relationship to eudaimonia . A virtue is a trait that contributes to or is a constituent of eudaimonia and we ought to develop virtues, the eudaimonist claims, precisely because they contribute to eudaimonia .

The concept of eudaimonia , a key term in ancient Greek moral philosophy, is standardly translated as “happiness” or “flourishing” and occasionally as “well-being.” Each translation has its disadvantages. The trouble with “flourishing” is that animals and even plants can flourish but eudaimonia is possible only for rational beings. The trouble with “happiness” is that in ordinary conversation it connotes something subjectively determined. It is for me, not for you, to pronounce on whether I am happy. If I think I am happy then I am—it is not something I can be wrong about (barring advanced cases of self-deception). Contrast my being healthy or flourishing. Here we have no difficulty in recognizing that I might think I was healthy, either physically or psychologically, or think that I was flourishing but be wrong. In this respect, “flourishing” is a better translation than “happiness”. It is all too easy to be mistaken about whether one’s life is eudaimon (the adjective from eudaimonia ) not simply because it is easy to deceive oneself, but because it is easy to have a mistaken conception of eudaimonia , or of what it is to live well as a human being, believing it to consist largely in physical pleasure or luxury for example.

Eudaimonia is, avowedly, a moralized or value-laden concept of happiness, something like “true” or “real” happiness or “the sort of happiness worth seeking or having.” It is thereby the sort of concept about which there can be substantial disagreement between people with different views about human life that cannot be resolved by appeal to some external standard on which, despite their different views, the parties to the disagreement concur (Hursthouse 1999: 188–189).

Most versions of virtue ethics agree that living a life in accordance with virtue is necessary for eudaimonia. This supreme good is not conceived of as an independently defined state (made up of, say, a list of non-moral goods that does not include virtuous activity) which exercise of the virtues might be thought to promote. It is, within virtue ethics, already conceived of as something of which virtuous activity is at least partially constitutive (Kraut 1989). Thereby virtue ethicists claim that a human life devoted to physical pleasure or the acquisition of wealth is not eudaimon , but a wasted life.

But although all standard versions of virtue ethics insist on that conceptual link between virtue and eudaimonia , further links are matters of dispute and generate different versions. For Aristotle, virtue is necessary but not sufficient—what is also needed are external goods which are a matter of luck. For Plato and the Stoics, virtue is both necessary and sufficient for eudaimonia (Annas 1993).

According to eudaimonist virtue ethics, the good life is the eudaimon life, and the virtues are what enable a human being to be eudaimon because the virtues just are those character traits that benefit their possessor in that way, barring bad luck. So there is a link between eudaimonia and what confers virtue status on a character trait. (For a discussion of the differences between eudaimonists see Baril 2014. For recent defenses of eudaimonism see Annas 2011; LeBar 2013b; Badhwar 2014; and Bloomfield 2014.)

Rather than deriving the normativity of virtue from the value of eudaimonia , agent-based virtue ethicists argue that other forms of normativity—including the value of eudaimonia —are traced back to and ultimately explained in terms of the motivational and dispositional qualities of agents.

It is unclear how many other forms of normativity must be explained in terms of the qualities of agents in order for a theory to count as agent-based. The two best-known agent-based theorists, Michael Slote and Linda Zagzebski, trace a wide range of normative qualities back to the qualities of agents. For example, Slote defines rightness and wrongness in terms of agents’ motivations: “[A]gent-based virtue ethics … understands rightness in terms of good motivations and wrongness in terms of the having of bad (or insufficiently good) motives” (2001: 14). Similarly, he explains the goodness of an action, the value of eudaimonia , the justice of a law or social institution, and the normativity of practical rationality in terms of the motivational and dispositional qualities of agents (2001: 99–100, 154, 2000). Zagzebski likewise defines right and wrong actions by reference to the emotions, motives, and dispositions of virtuous and vicious agents. For example, “A wrong act = an act that the phronimos characteristically would not do, and he would feel guilty if he did = an act such that it is not the case that he might do it = an act that expresses a vice = an act that is against a requirement of virtue (the virtuous self)” (Zagzebski 2004: 160). Her definitions of duties, good and bad ends, and good and bad states of affairs are similarly grounded in the motivational and dispositional states of exemplary agents (1998, 2004, 2010).

However, there could also be less ambitious agent-based approaches to virtue ethics (see Slote 1997). At the very least, an agent-based approach must be committed to explaining what one should do by reference to the motivational and dispositional states of agents. But this is not yet a sufficient condition for counting as an agent-based approach, since the same condition will be met by every virtue ethical account. For a theory to count as an agent-based form of virtue ethics it must also be the case that the normative properties of motivations and dispositions cannot be explained in terms of the normative properties of something else (such as eudaimonia or states of affairs) which is taken to be more fundamental.

Beyond this basic commitment, there is room for agent-based theories to be developed in a number of different directions. The most important distinguishing factor has to do with how motivations and dispositions are taken to matter for the purposes of explaining other normative qualities. For Slote what matters are this particular agent’s actual motives and dispositions . The goodness of action A, for example, is derived from the agent’s motives when she performs A. If those motives are good then the action is good, if not then not. On Zagzebski’s account, by contrast, a good or bad, right or wrong action is defined not by this agent’s actual motives but rather by whether this is the sort of action a virtuously motivated agent would perform (Zagzebski 2004: 160). Appeal to the virtuous agent’s hypothetical motives and dispositions enables Zagzebski to distinguish between performing the right action and doing so for the right reasons (a distinction that, as Brady (2004) observes, Slote has trouble drawing).

Another point on which agent-based forms of virtue ethics might differ concerns how one identifies virtuous motivations and dispositions. According to Zagzebski’s exemplarist account, “We do not have criteria for goodness in advance of identifying the exemplars of goodness” (Zagzebski 2004: 41). As we observe the people around us, we find ourselves wanting to be like some of them (in at least some respects) and not wanting to be like others. The former provide us with positive exemplars and the latter with negative ones. Our understanding of better and worse motivations and virtuous and vicious dispositions is grounded in these primitive responses to exemplars (2004: 53). This is not to say that every time we act we stop and ask ourselves what one of our exemplars would do in this situations. Our moral concepts become more refined over time as we encounter a wider variety of exemplars and begin to draw systematic connections between them, noting what they have in common, how they differ, and which of these commonalities and differences matter, morally speaking. Recognizable motivational profiles emerge and come to be labeled as virtues or vices, and these, in turn, shape our understanding of the obligations we have and the ends we should pursue. However, even though the systematising of moral thought can travel a long way from our starting point, according to the exemplarist it never reaches a stage where reference to exemplars is replaced by the recognition of something more fundamental. At the end of the day, according to the exemplarist, our moral system still rests on our basic propensity to take a liking (or disliking) to exemplars. Nevertheless, one could be an agent-based theorist without advancing the exemplarist’s account of the origins or reference conditions for judgments of good and bad, virtuous and vicious.

The touchstone for eudaimonist virtue ethicists is a flourishing human life. For agent-based virtue ethicists it is an exemplary agent’s motivations. The target-centered view developed by Christine Swanton (2003), by contrast, begins with our existing conceptions of the virtues. We already have a passable idea of which traits are virtues and what they involve. Of course, this untutored understanding can be clarified and improved, and it is one of the tasks of the virtue ethicist to help us do precisely that. But rather than stripping things back to something as basic as the motivations we want to imitate or building it up to something as elaborate as an entire flourishing life, the target-centered view begins where most ethics students find themselves, namely, with the idea that generosity, courage, self-discipline, compassion, and the like get a tick of approval. It then examines what these traits involve.

A complete account of virtue will map out 1) its field , 2) its mode of responsiveness, 3) its basis of moral acknowledgment, and 4) its target . Different virtues are concerned with different fields . Courage, for example, is concerned with what might harm us, whereas generosity is concerned with the sharing of time, talent, and property. The basis of acknowledgment of a virtue is the feature within the virtue’s field to which it responds. To continue with our previous examples, generosity is attentive to the benefits that others might enjoy through one’s agency, and courage responds to threats to value, status, or the bonds that exist between oneself and particular others, and the fear such threats might generate. A virtue’s mode has to do with how it responds to the bases of acknowledgment within its field. Generosity promotes a good, namely, another’s benefit, whereas courage defends a value, bond, or status. Finally, a virtue’s target is that at which it is aimed. Courage aims to control fear and handle danger, while generosity aims to share time, talents, or possessions with others in ways that benefit them.

A virtue , on a target-centered account, “is a disposition to respond to, or acknowledge, items within its field or fields in an excellent or good enough way” (Swanton 2003: 19). A virtuous act is an act that hits the target of a virtue, which is to say that it succeeds in responding to items in its field in the specified way (233). Providing a target-centered definition of a right action requires us to move beyond the analysis of a single virtue and the actions that follow from it. This is because a single action context may involve a number of different, overlapping fields. Determination might lead me to persist in trying to complete a difficult task even if doing so requires a singleness of purpose. But love for my family might make a different use of my time and attention. In order to define right action a target-centered view must explain how we handle different virtues’ conflicting claims on our resources. There are at least three different ways to address this challenge. A perfectionist target-centered account would stipulate, “An act is right if and only if it is overall virtuous, and that entails that it is the, or a, best action possible in the circumstances” (239–240). A more permissive target-centered account would not identify ‘right’ with ‘best’, but would allow an action to count as right provided “it is good enough even if not the (or a) best action” (240). A minimalist target-centered account would not even require an action to be good in order to be right. On such a view, “An act is right if and only if it is not overall vicious” (240). (For further discussion of target-centered virtue ethics see Van Zyl 2014; and Smith 2016).

The fourth form a virtue ethic might adopt takes its inspiration from Plato. The Socrates of Plato’s dialogues devotes a great deal of time to asking his fellow Athenians to explain the nature of virtues like justice, courage, piety, and wisdom. So it is clear that Plato counts as a virtue theorist. But it is a matter of some debate whether he should be read as a virtue ethicist (White 2015). What is not open to debate is whether Plato has had an important influence on the contemporary revival of interest in virtue ethics. A number of those who have contributed to the revival have done so as Plato scholars (e.g., Prior 1991; Kamtekar 1998; Annas 1999; and Reshotko 2006). However, often they have ended up championing a eudaimonist version of virtue ethics (see Prior 2001 and Annas 2011), rather than a version that would warrant a separate classification. Nevertheless, there are two variants that call for distinct treatment.