Systematic Reviews

- The Research Question

- Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Original Studies

- Translating

- Deduplication

- Project Management Tools

- Useful Resources

- What is not a systematic review?

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria.

Identify the criteria that will be used to determine which research studies will be included. The inclusion and exclusion criteria must be decided before you start the review. Inclusion criteria is everything a study must have to be included. Exclusion criteria are the factors that would make a study ineligible to be included. Criteria that should be considered include:

Type of studies: It is important to select articles with an appropriate study design for the research question. Dates for the studies and a timeline of the problem/issue being examined may need to be identified.

Type of participants: Identify the target population characteristics. It is important to define the target population's age, sex/gender, diagnosis, as well as any other relevant factors.

Types of intervention: Describe the intervention being investigated. Consider whether to include interventions carried out globally or just in the United States. Eligibility criteria for interventions should include things such as the dose, delivery method, and duration of the investigated intervention. The interventions that are to be excluded may also need to be described here.

Types of outcome measures: Outcome measures usually refer to measurable outcomes or ‘clinical changes in health’. For example, these could include body structures and functions like pain and fatigue, activities as in functional abilities, and participation or quality of life questionnaires.

Read Chapter 3 of the Cochrane Handbook

Exclusion criteria.

A balance of specific inclusion and exclusion criteria is paramount. For some systematic reviews, there may already be a large pre-existing body of literature. The search strategy may retrieve thousands of results that must be screened. Having explicit exclusion criteria from the beginning allows those conducting the screening process, an efficient workflow. For the final product there should be a section in the review dedicated to 'Characteristics of excluded studies.' It is important to summarize why studies were excluded, especially if to a reader the study would appear to be eligible for the systematic review.

For example, a team is conducting a systematic review regarding intervention options for the treatment of opioid addiction. The research team may want to exclude studies that also involve alcohol addiction to isolate the conditions for treatment interventions solely for opioid addiction.

- << Previous: Planning and Protocols

- Next: Searching >>

- Last Updated: Oct 12, 2023 12:30 PM

- URL: https://libguides.sph.uth.tmc.edu/SystematicReviews

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- First Online: 30 August 2019

Cite this chapter

- David Tod 2

1454 Accesses

A systematic literature search can yield hundreds or thousands of records, each a potential relevant study. Sustained attention to detail is a pre-requisite for identifying relevant research. Well-constructed, clear, and explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria assist decision making consistency. In this chapter, I focus on inclusion and exclusion criteria, explain their benefits, provide guidelines on their construction and use, and illustrate with examples from sport, exercise, and physical activity research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Abrami, P. C., Cohen, P. A., & d’Apollonia, S. (1988). Implementation problems in meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 58, 151–179. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543058002151 .

Article Google Scholar

Andersen, M. B. (2005). Coming full circle: From practice to research. In M. B. Andersen (Ed.), Sport psychology in practice (pp. 287–298). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Google Scholar

Andersen, M. B., McCullagh, P., & Wilson, G. J. (2007). But what do the numbers really tell us? Arbitrary metrics and effect size reporting in sport psychology research. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 29, 664–672. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.29.5.664 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Benzies, K. M., Premji, S., Hayden, K. A., & Serrett, K. (2006). State-of-the-evidence reviews: Advantages and challenges of including grey literature. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 3, 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6787.2006.00051.x .

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis . Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Book Google Scholar

Bruce, R., Chauvin, A., Trinquart, L., Ravaud, P., & Boutron, I. (2016). Impact of interventions to improve the quality of peer review of biomedical journals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Medicine, 14 , article 85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0631-5 .

Card, N. A. (2012). Applied meta-analysis for social science research . New York, NY: Guilford.

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. (2009). Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care . York, UK: Author.

Cooke, A., Smith, D., & Booth, A. (2012). Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 22, 1435–1443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312452938 .

Hardy, J., Oliver, E., & Tod, D. (2009). A framework for the study and application of self-talk within sport. In S. D. Mellalieu & S. Hanton (Eds.), Advances in applied sport psychology: A review (pp. 37–74). London, UK: Routledge.

Holt, N. L., Neely, K. C., Slater, L. G., Camiré, M., Côté, J., Fraser-Thomas, J., … Tamminen, K. A. (2017). A grounded theory of positive youth development through sport based on results from a qualitative meta-study. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10, 1–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2016.1180704 .

Horton, J., Vandermeer, B., Hartling, L., Tjosvold, L., Klassen, T. P., & Buscemi, N. (2010). Systematic review data extraction: Cross-sectional study showed that experience did not increase accuracy. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63, 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.04.007 .

Meline, T. (2006). Selecting studies for systematic review: Inclusion and exclusion criteria. Contemporary Issues in Communication Science and Disorders, 33, 21–27.

Munoz, S. R., & Bangdiwala, S. I. (1997). Interpretation of Kappa and B statistics measures of agreement. Journal of Applied Statistics, 24, 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/02664769723918 .

O’Connor, D., Green, S., & Higgins, J. P. T. (2011). Defining the review question and developing criteria for including studies. In J. P. T. Higgins & S. Green (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions . Version 5.1.0 [updated September 2011]: The Cochrane Collaboration. Retrieved from www.cochrane-handbook.org .

Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Roig, M., O’Brien, K., Kirk, G., Murray, R., McKinnon, P., Shadgan, B., & Reid, W. D. (2009). The effects of eccentric versus concentric resistance training on muscle strength and mass in healthy adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 43 , 556–568. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2008.051417 .

Sackett, D. L., & Wennberg, J. E. (1997). Choosing the best research design for each question. British Medical Journal, 315, 1636. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7123.1636 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tod, D., & Edwards, C. (2015). A meta-analysis of the drive for muscularity’s relationships with exercise behaviour, disordered eating, supplement consumption, and exercise dependence. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 8, 185–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2015.1052089 .

Treadwell, J. R., Singh, S., Talati, R., McPheeters, M. L., & Reston, J. T. (2011). A framework for “best evidence” approaches in systematic reviews . Plymouth Meeting, PA: ECRI Institute Evidence-based Practice Center.

Walach, H., & Loef, M. (2015). Using a matrix-analytical approach to synthesizing evidence solved incompatibility problem in the hierarchy of evidence. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 68, 1251–1260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.03.027 .

Wilkinson, L., & Task Force on Statistical Inference. (1999). Statistical methods in psychology journals: Guidelines and explanations. American Psychologist, 54 , 594–604. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.54.8.594 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Sport and Exercise Science, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to David Tod .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Tod, D. (2019). Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria. In: Conducting Systematic Reviews in Sport, Exercise, and Physical Activity. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12263-8_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12263-8_5

Published : 30 August 2019

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-12262-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-12263-8

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Evidence-Based Practice (EBP)

- The EBP Process

- Forming a Clinical Question

- Inclusion & Exclusion Criteria

- Acquiring Evidence

- Appraising the Quality of the Evidence

- Writing a Literature Review

- Finding Psychological Tests & Assessment Instruments

Selection Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are determined after formulating the research question but usually before the search is conducted (although preliminary scoping searches may need to be undertaken to determine appropriate criteria). It may be helpful to determine the inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria for each PICO component.

Be aware that you may introduce bias into the final review if these are not used thoughtfully.

Inclusion and exclusion are two sides of the same coin, so—depending on your perspective—a single database filter can be said to either include or exclude. For instance, if articles must be published within the last 3 years, that is inclusion. If articles cannot be more than 3 years old, that is exclusion.

The most straightforward way to include or exclude results is to use database limiters (filters), usually found on the left side of the search results page.

Inclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria are the elements of an article that must be present in order for it to be eligible for inclusion in a literature review. Some examples are:

- Included studies must have compared certain treatments

- Included studies must be a certain type (e.g., only Randomized Controlled Trials)

- Included studies must be located in a certain geographic area

- Included studies must have been published in the last 5 years

Exclusion Criteria

Exclusion criteria are the elements of an article that disqualify the study from inclusion in a literature review. Some examples are:

- Study used an observational design

- Study used a qualitative methodology

- Study was published more than 5 years ago

- Study was published in a language other than English

- << Previous: Forming a Clinical Question

- Next: Acquiring Evidence >>

- Last Updated: Nov 15, 2023 11:47 AM

- URL: https://libguides.umsl.edu/ebp

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria | Examples & Definition

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria | Examples & Definition

Published on September 17, 2022 by Kassiani Nikolopoulou . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria determine which members of the target population can or can’t participate in a research study. Collectively, they’re known as eligibility criteria , and establishing them is critical when seeking study participants for clinical trials.

This allows researchers to study the needs of a relatively homogeneous group (e.g., people with liver disease) with precision. Examples of common inclusion and exclusion criteria are:

- Demographic characteristics: Age, gender identity, ethnicity

- Study-specific variables: Type and stage of disease, previous treatment history, presence of chronic conditions, ability to attend follow-up study appointments, technological requirements (e.g., internet access)

- Control variables : Fitness level, tobacco use, medications used

Failure to properly define inclusion and exclusion criteria can undermine your confidence that causal relationships exist between treatment and control groups, affecting the internal validity of your study and the generalizability ( external validity ) of your findings.

Table of contents

What are inclusion criteria, what are exclusion criteria, examples of inclusion and exclusion criteria, why are inclusion and exclusion criteria important, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions.

Inclusion criteria comprise the characteristics or attributes that prospective research participants must have in order to be included in the study. Common inclusion criteria can be demographic, clinical, or geographic in nature.

- 18 to 80 years of age

- Diagnosis of chronic heart failure at least 6 months before trial

- On stable doses of heart failure therapies

- Willing to return for required follow-up (posttest) visits

People who meet the inclusion criteria are then eligible to participate in the study.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Exclusion criteria comprise characteristics used to identify potential research participants who should not be included in a study. These can also include those that lead to participants withdrawing from a research study after being initially included.

In other words, individuals who meet the inclusion criteria may also possess additional characteristics that can interfere with the outcome of the study. For this reason, they must be excluded.

Typical exclusion criteria can be:

- Ethical considerations , such as being a minor or being unable to give informed consent

- Practical considerations, such as not being able to read

If potential participants possess any additional characteristics that can affect the results, such as another medical condition or a pregnancy, these are also often grounds for exclusion.

- The patient requires valve or other cardiac surgery

- The patient is unable to carry out any physical activity without discomfort

- The patient had a stroke within three months prior to enrollment

- The patient refuses to give informed consent

- The patient is a candidate for coronary bypass surgery or something similar

People who meet one or more of the exclusion criteria must be disqualified. This means that they can’t participate in the study even if they meet the inclusion criteria.

It is important that researchers clearly define the appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria prior to recruiting participants for their experiment or trial.

Here are some examples of effective and ineffective ways to phrase your criteria:

Inclusion criteria

Bad example: “Subjects will be included in the study if they have insomnia.”

This is too vague. How are you going to establish that participants have insomnia?

Good example: “Subjects will be included in the study if they have been diagnosed with insomnia by a physician and have had symptoms (i.e., trouble falling and/or staying asleep) for at least 3 nights a week for a minimum of 3 months.”

Here, the diagnosis and symptoms are clear. Specifying the time frame ensures that the condition (insomnia) is more likely to be stable throughout the study.

Exclusion criteria

Bad example: “Subjects will be excluded from the study if they are taking medications.”

This is too broad. There are many forms of medication, and some surely will not interfere with your study results. Excluding anyone who is using any type of medication—be it painkillers, birth control, or antidepressants—makes recruitment of study participants for your sample difficult. This, in turn, affects the feasibility of your study.

Good example: “Subjects will be excluded from the study if they are currently on any medication affecting sleep, prescription drugs, or other drugs that in the opinion of the research team may interfere with the results of the study.”

Researchers review inclusion and exclusion criteria with each potential participant to determine their eligibility.

Defining inclusion and exclusion criteria is important in any type of research that examines characteristics of a specific subset of a population . This helps researchers identify the study population in a consistent, reliable, and objective manner. As a result, study participants are more likely to have the attributes that will make it possible to robustly answer the research question .

In clinical trials, establishing inclusion and exclusion criteria minimizes the likelihood of harming participants (e.g., excluding pregnant women) and safeguards vulnerable individuals from exploitation (e.g., excluding individuals who are unable to comprehend what the research entails.) Ethical considerations like these are critical in human-based research.

The main goal of clinical trials is to prove that a medication is safe and effective when used by the target population it was designed for. Therefore, ensuring that study participants are representative of the target population is crucial to the success of the study.

By applying inclusion and exclusion criteria to recruit participants, researchers can ensure that participants are indeed representative of the target population, ensuring external validity . Relatedly, defining robust inclusion and exclusion criteria strengthens your claim that causal relationships exist between your treatment and control groups , ensuring internal validity .

Strong inclusion and exclusion criteria also help other researchers, because they can follow what you did and how you selected participants, allowing them to accurately replicate or reproduce your study.

Ethnographies and a few other types of qualitative research do not usually specify exclusion criteria. However, inclusion criteria help researchers define the community of interest—for example, users of Apple watches. In this way, they can find individuals who have attributes that can help them meet the research objectives .

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

I nternal validity is the degree of confidence that the causal relationship you are testing is not influenced by other factors or variables .

External validity is the extent to which your results can be generalized to other contexts.

The validity of your experiment depends on your experimental design .

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are predominantly used in non-probability sampling . In purposive sampling and snowball sampling , restrictions apply as to who can be included in the sample .

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are typically presented and discussed in the methodology section of your thesis or dissertation .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Nikolopoulou, K. (2023, June 22). Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria | Examples & Definition. Scribbr. Retrieved April 1, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/inclusion-exclusion-criteria/

Is this article helpful?

Kassiani Nikolopoulou

Other students also liked, population vs. sample | definitions, differences & examples, external validity | definition, types, threats & examples, reproducibility vs replicability | difference & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Holiday opening hours

Opening hours for our libraries and Library Chat have been adjusted over the Easter holidays. Please check our library opening hours page before you visit.

Systematic Reviews for Health Sciences and Medicine

- Systematic Reviews

- The research question

- Common search errors

- Search translation

- Managing results

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Critical appraisal

- Updating a Review

- Resources by Review Stage

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria set the boundaries for the systematic review. They are determined after setting the research question usually before the search is conducted, however scoping searches may need to be undertaken to determine appropriate criteria. Many different factors can be used as inclusion or exclusion criteria. Information about the inclusion and exclusion criteria is usually recorded as a paragraph or table within the methods section of the systematic review. It may also be necessary to give the definitions, and source of the definition, used for particular concepts in the research question (e.g. adolescence, depression).

Other inclusion/exclusion criteria can include the sample size, method of sampling or availability of a relevant comparison group in the study. Where a single study is reported across multiple papers the findings from the papers may be merged or only the latest data may be included.

- << Previous: Managing results

- Next: Critical appraisal >>

- Last Updated: Mar 16, 2024 12:00 PM

- URL: https://unimelb.libguides.com/sysrev

- Library guides

- Book study rooms

- Library Workshops

- Library Account

Library Services

- Library Services Home

Literature searching and finding evidence

- Literature searching or literature review?

- Use the PICO or PEO frameworks

Establish your Inclusion and Exclusion criteria

- Find related search terms

- Subject Heading/MeSH Searching

- Select databases to search

- Structure your search

- Search techniques

- Search key databases

- Manage results in EBSCOhost and Ovid

- Analyse your search results

- Document your search results

- Training and support

These criteria help you decide which studies will/will not be included in your work. This will help make sure your work is as unbiased, transparent and ethical as possible.

How to establish your Inclusion and Exclusion criteria

To establish your criteria you need to define each aspect of your question to clarify what you are focusing on, and consider if there are any variations you also wish to explore. This is where using frameworks like PICO help:

Example: Alternatives to drugs for controlling headaches in children

Using the PICO structure you clarify what aspects you are most interested in. Here are some examples to consider:

The aspects of the topic you decide to focus on are the Inclusion criteria.

The aspects you don't wish to include are the Exclusion criteria.

- << Previous: Use the PICO or PEO frameworks

- Next: Find related search terms >>

- Last Updated: Mar 22, 2024 9:52 AM

- URL: https://libguides.city.ac.uk/SHS-Litsearchguide

Inclusion and exclusion criteria in research studies: definitions and why they matter

Affiliation.

- 1 Methods in Epidemiologic, Clinical, and Operations Research-MECOR-program, American Thoracic Society/Asociación Latinoamericana del Tórax, Montevideo, Uruguay.

- PMID: 29791550

- PMCID: PMC6044655

- DOI: 10.1590/s1806-37562018000000088

- Biomedical Research / standards*

- Cross-Sectional Studies

- Patient Selection*

- Treatment Adherence and Compliance*

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

Once you have a clearly defined research question, make sure you are getting precisely the right search results from searching the databases by making decisions about these items:

- Would the most recent five years be appropriate?

- Is your research from a more historical perspective?

- Where has this type of research taken place?

- Will you confine your results to the United States?

- To English speaking countries?

- Will you translate works if needed?

- Is there a particular methodology, or population that you are focused on?

- Are there adjacent fields in which this type of research has been conducted that you would like to include?

- Is there a controversy or debate in your research field that you want to highlight

- Are you creating a historical overview? Is this background reading for your research?

- Is there new technology that can shed light on an old problem or an old technology that can be used in a new way?

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2022 2:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Higher odds of periodontitis in systemic lupus erythematosus compared to controls and rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review, meta-analysis and network meta-analysis.

- 1 Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

- 2 Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore

- 3 Biostatistics Unit, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

- 4 Faculty of Dentistry, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

- 5 Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, National University Hospital, Singapore, Singapore

- 6 Department of Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

Introduction: Periodontitis as a comorbidity in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is still not well recognized in the dental and rheumatology communities. A meta-analysis and network meta-analysis were thus performed to compare the (i) prevalence of periodontitis in SLE patients compared to those with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and (ii) odds of developing periodontitis in controls, RA, and SLE.

Methods: Pooled prevalence of and odds ratio (OR) for periodontitis were compared using meta-analysis and network meta-analysis (NMA).

Results: Forty-three observational studies involving 7,800 SLE patients, 49,388 RA patients, and 766,323 controls were included in this meta-analysis. The pooled prevalence of periodontitis in SLE patients (67.0%, 95% confidence interval [CI] 57.0-77.0%) was comparable to that of RA (65%, 95% CI 55.0-75.0%) (p>0.05). Compared to controls, patients with SLE (OR=2.64, 95% CI 1.24-5.62, p<0.01) and RA (OR=1.81, 95% CI 1.25-2.64, p<0.01) were more likely to have periodontitis. Indirect comparisons through the NMA demonstrated that the odds of having periodontitis in SLE was 1.49 times higher compared to RA (OR=1.49, 95% CI 1.09-2.05, p<0.05).

Discussion: Given that RA is the autoimmune disease classically associated with periodontal disease, the higher odds of having periodontitis in SLE are striking. These results highlight the importance of addressing the dental health needs of patients with SLE.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/ , identifier CRD42021272876.

1 Introduction

Periodontitis is a microbially-associated, host-mediated hyperinflammatory condition that leads to the destruction of structures supporting the teeth, including the alveolar bone, periodontal ligament, and cementum ( 1 – 3 ). If not addressed, periodontitis can lead to early tooth loss, affecting one’s ability to chew, self-confidence, and overall well-being ( 4 – 6 ). Furthermore, periodontitis has been linked to broader health implications, contributing to conditions such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and adverse outcomes in pregnancy ( 7 ). The global prevalence of periodontitis is 20-50%, and together with gingivitis, its precursor, they collectively constitute the 11 th most prevalent condition worldwide ( 8 ). Its impact is substantial, accounting for 3.5 million years of disability and causing an estimated productivity loss of around USD$54 billion annually ( 4 ). Recent studies have also shown significant associations between rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and, to a smaller degree, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), with periodontitis ( 9 – 11 ). However, these associations remain underappreciated and warrant further investigations ( 12 ).

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic autoimmune disease that has both joint-specific and systemic manifestations ( 13 ). Its global prevalence, as estimated by the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study, stands at approximately 0.24% ( 14 , 15 ). SLE is a potentially fatal, chronic autoimmune disease that affects multiple systems. It primarily affects women, with the highest incidence during childbearing years ( 16 ). The global prevalence of SLE has been on the rise over the years, escalating from 40 cases per 100,000 individuals in the 1970s to 100 cases per 100,000 individuals since the 2000s ( 17 ).

The exact aetiopathogenesis of RA and SLE is complex, with multiple genetic, epigenetic, immunological, and environmental factors involved. These factors often culminate in immune dysregulation and autoantibody production ( 18 – 20 ). Moreover, evidence suggests that infections may contribute to the development of these diseases through mechanisms such as molecular mimicry and uncontrolled immune cell activation ( 21 ). The relationship between RA and periodontitis is better established than that between SLE and periodontitis, partly due to the process of citrullination. Citrullination involves the modification of arginine residues to citrulline by peptidyl arginine deiminases. Porphyromonas gingivalis , a key organism in periodontitis, is the sole prokaryotic organism that secretes Porphyromonas gingivalis -derived peptidyl arginine deiminase (PPAD) ( 11 , 22 ). Prolonged exposure to citrullinated proteins in the oral cavity may trigger the production of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibodies, potentially leading to the onset of RA in susceptible individuals ( 23 ). The associations between (i) periodontitis and anti-CCP seropositivity and (ii) periodontitis severity and presence of anti-CCP antibodies in patients with RA provide further support for this hypothesis ( 24 , 25 ). In addition, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs ameliorate both RA and periodontitis, suggesting shared inflammatory pathways ( 26 ). In contrast, while a connection between SLE and periodontitis is emerging, it is still in the early stages of recognition, and the relationship has not been confirmed ( 10 , 27 , 28 ). Despite the high prevalence of Porphyromonas gingivalis , this pathogen appears to have minimal involvement in the onset of periodontitis in SLE patients. Additionally, anti-CCP antibodies are infrequently detected in individuals with SLE ( 29 , 30 ). Nonetheless, both RA and SLE may overlap, causing a syndrome termed “rhupus” whereby features of both diseases appear in the same patient ( 31 ). Furthermore, a positive association between anti-CCP antibodies and erosive arthritis has been reported in rhupus ( 31 ). Consequently, while periodontitis might contribute to the onset of RA, a similar association may ostensibly also occur for SLE.

Considering the overlap between RA and SLE, the magnitude of the burden of periodontitis in SLE compared to RA patients has not been explored. Therefore, the aim of this meta-analysis and network meta-analysis (NMA) is to compare: (i) the prevalence of periodontitis in SLE patients compared to versus those with RA and (ii) the odds of developing periodontitis in controls, RA, and SLE to evaluate the magnitude of this comorbidity in SLE.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 literature search and study retrieval.

This meta-analysis adhered to the guidelines outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. Two independent investigators (P.R.T. and A.J.L.L.) conducted searches in the PubMed, Medline, Scopus, and EMBASE databases from their inception dates. The searches were repeated just before the final analyses on 9 April 2023. A combination of search terms such as “systemic lupus erythematosus” or “SLE”, “rheumatoid arthritis” or “RA”, “periodontitis” or “chronic periodontitis” or “adult periodontitis” were used ( Supplementary Table 1 ). Articles were first screened based on their titles and abstracts by two authors (P.R.T. and A.J.L.L.). Subsequently, P.R.T. and A.J.L.L. independently reviewed the full texts of eligible articles for inclusion. All disagreements during screening or data extraction were resolved were resolved through consensus between the reviewers or by consulting with the senior author (S.H.T.). The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42021272876). The Patient, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes question is the following: Is there a difference in prevalence or odds of periodontitis in SLE patients compared to RA?

2.2 Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) cross-sectional or case-control study design; (ii) the study reported a quantitative association, i.e., periodontitis events and sample size in RA/SLE and RA/SLE versus controls to calculate event rate and odds ratio (OR), respectively and (iii) the language was limited to English. If the same population was reported in multiple studies, only the most comprehensive study with the largest sample size was included. Patients with periodontitis, RA, and SLE were enrolled in the various studies either based on various definitions, classification criteria, or physician diagnoses. These details are provided in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2 .

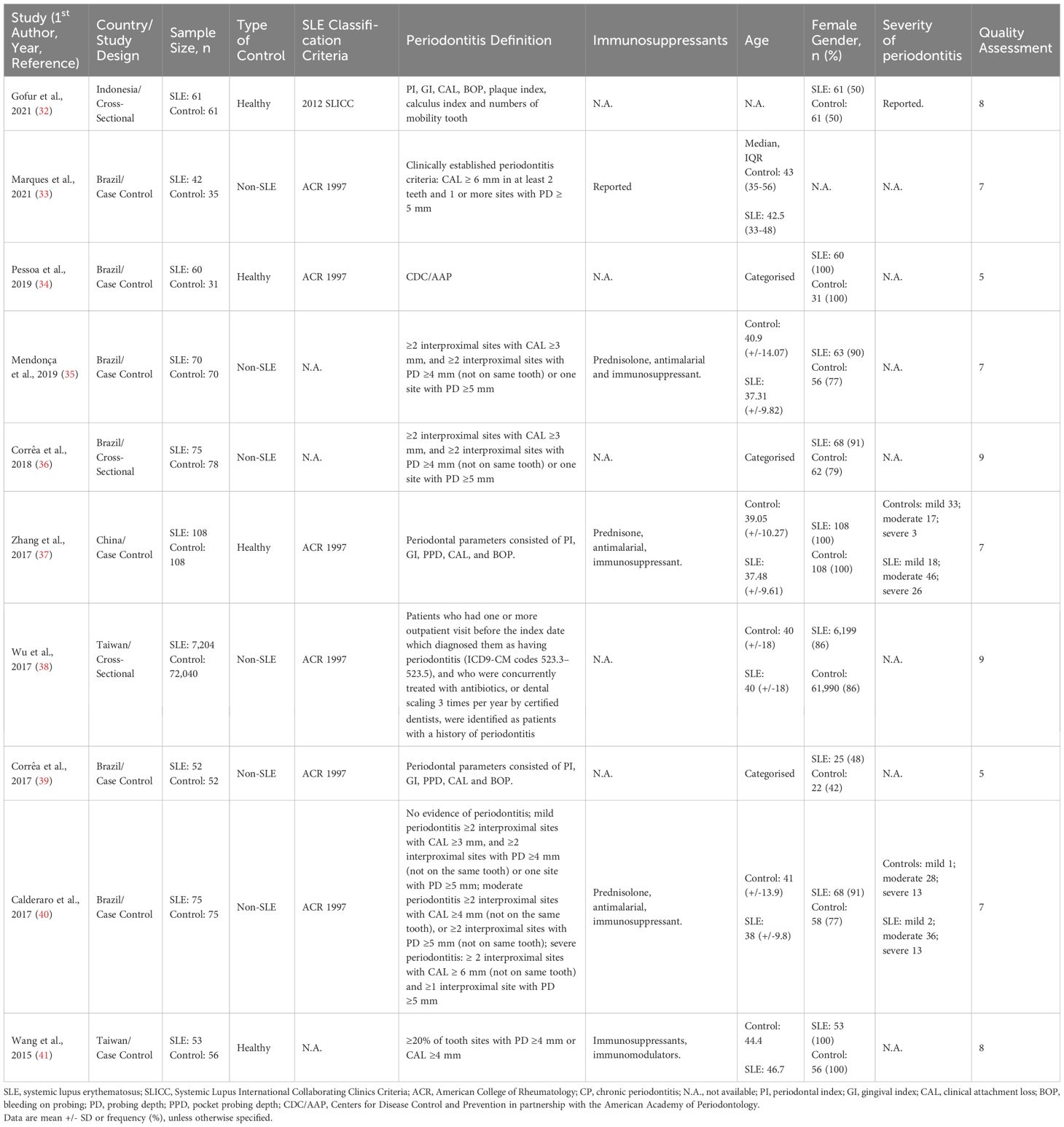

Table 1 Characteristics of the SLE studies included in the meta-analysis.

2.3 Exclusion criteria

Articles were excluded based on the following: (i) periodontal parameters were reported but a diagnosis of periodontitis was not made; (ii) diagnoses of RA or SLE were not reported; (iii) participants were enrolled based on a diagnosis of periodontitis as an entry criterion and not that of RA or SLE and (iv) animal studies, case reports and reviews.

2.4 Quality assessment

The quality assessment of case-control studies was conducted using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS), while cross-sectional studies were evaluated using the modified NOS ( 42 ). Studies with NOS scores ≤3, 4–6, and ≥7 were categorized as low, moderate, and high quality, respectively.

2.5 Data extraction

The following data were extracted from each included study: (i) study characteristics, including the first author, publication year, region, study design, sample size, RA/SLE classification criteria, periodontitis definition, inclusion and exclusion criteria for cases and controls; (ii) study participant demographics, including mean age, sex, RA/SLE duration, and smoking status; (iii) periodontal measures, including the definition of periodontitis and prevalence of periodontitis and (iv) disease activity and markers, including SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) for SLE and Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) for RA. Due to differences in the definitions of controls across studies, for the NMA, the control populations across the RA and SLE studies are homogenized under the working definition of “absence of known immune-mediated inflammatory disorders and dental diseases”. Thus, this homogenized group consists of healthy, osteoarthritis patients, non-RA and non-SLE controls.

2.6 Data synthesis

This study aimed to examine the proportion of periodontitis in patients with RA/SLE and to compare the ORs for periodontitis of RA and SLE with each other and with controls. Pooled proportions were computed using the inverse variance method with the variance-stabilising Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation. The confidence intervals (CIs) for individual studies were calculated using the Wilson score CI method with continuity correction. Subgroup analyses were conducted between patients with SLE and those with RA. Differences between pooled prevalence were evaluated using between-subgroup heterogeneity. Meta-regression was attempted using disease activity as a covariate to investigate the association between disease activity and the prevalence of periodontitis. The I 2 statistic was used to represent between-study heterogeneity, where I 2 ≤30%, between >30% and ≤50%, between >50% and <75%, and ≥75% were considered to indicate low, moderate, substantial, and considerable heterogeneity, respectively. A NMA was done to indirectly compare if periodontitis is more likely to be associated with RA or SLE. To harmonise the controls from the RA and SLE papers into a single common group, controls were defined as the absence of immune-mediated inflammatory disorders and known dental diseases before study enrollment. The networks were built with controls, RA patients, and SLE patients. As there was no closed loop in the network, inconsistency could not be evaluated in this NMA. Subgroup analyses were conducted to identify the source of heterogeneity as well as to analyze the diversity among different subgroups. Potential publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot and the Egger’s test ( 43 ). Further assessment of publication bias was done using Duval and Tweedie trim-and-fill method ( 44 ). All analyses were performed using R version 4.1.2, with metafor and netmeta packages. Statistical significance was set at two-sided p<0.05.

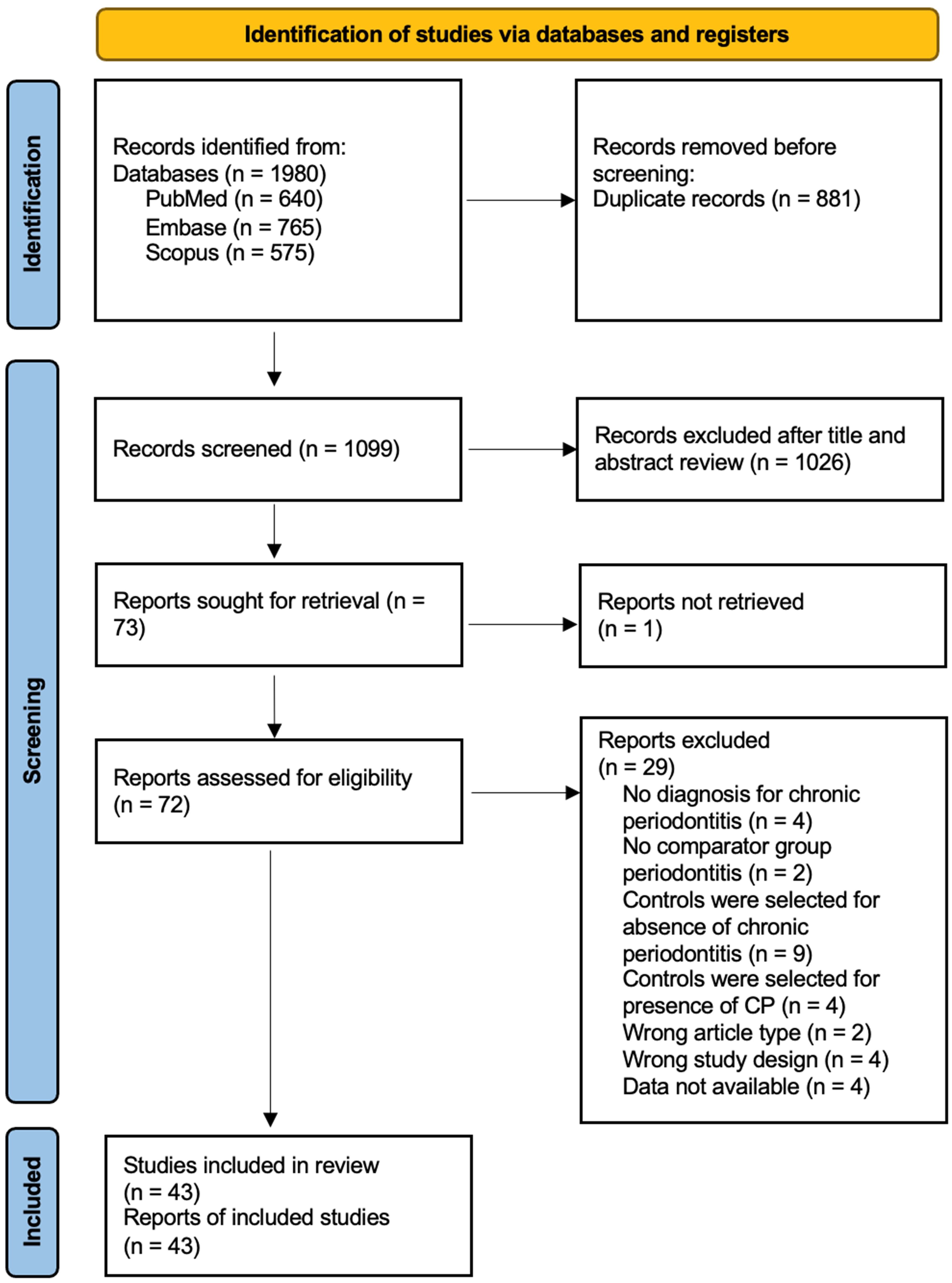

3.1 Characteristics of the selected studies

The search strategy yielded 230 and 1,751 potentially relevant SLE and RA studies, respectively. 102 SLE articles and 997 RA articles remained after duplicates were removed. Of the 1099 abstracts screened, 18 SLE and 54 RA studies met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Their full texts were reviewed. Finally, 10 SLE ( 32 – 41 ) and 33 RA ( 24 , 45 – 74 ) studies, i.e., 43 in total, were deemed eligible for the meta-analysis ( Figure 1 , Table 1 ; Supplementary Table 2 ).

Figure 1 PRISMA flow diagram for RA and SLE studies.

3.2 Quality appraisal of included studies

Of the 43 studies that underwent quality assessment using the Newcastle-Ottawa checklist, 14 (2 SLE studies and 14 RA studies) obtained a score between 4-6 (moderate quality), while the remaining 29 (8 SLE studies and 21 RA studies) obtained a score of ≥7 (high quality) ( Table 1 ; Supplementary Table 2 ). The limitations of the studies regarded as moderate quality were mainly related to the sampling methods.

3.3 Periodontitis in RA and SLE

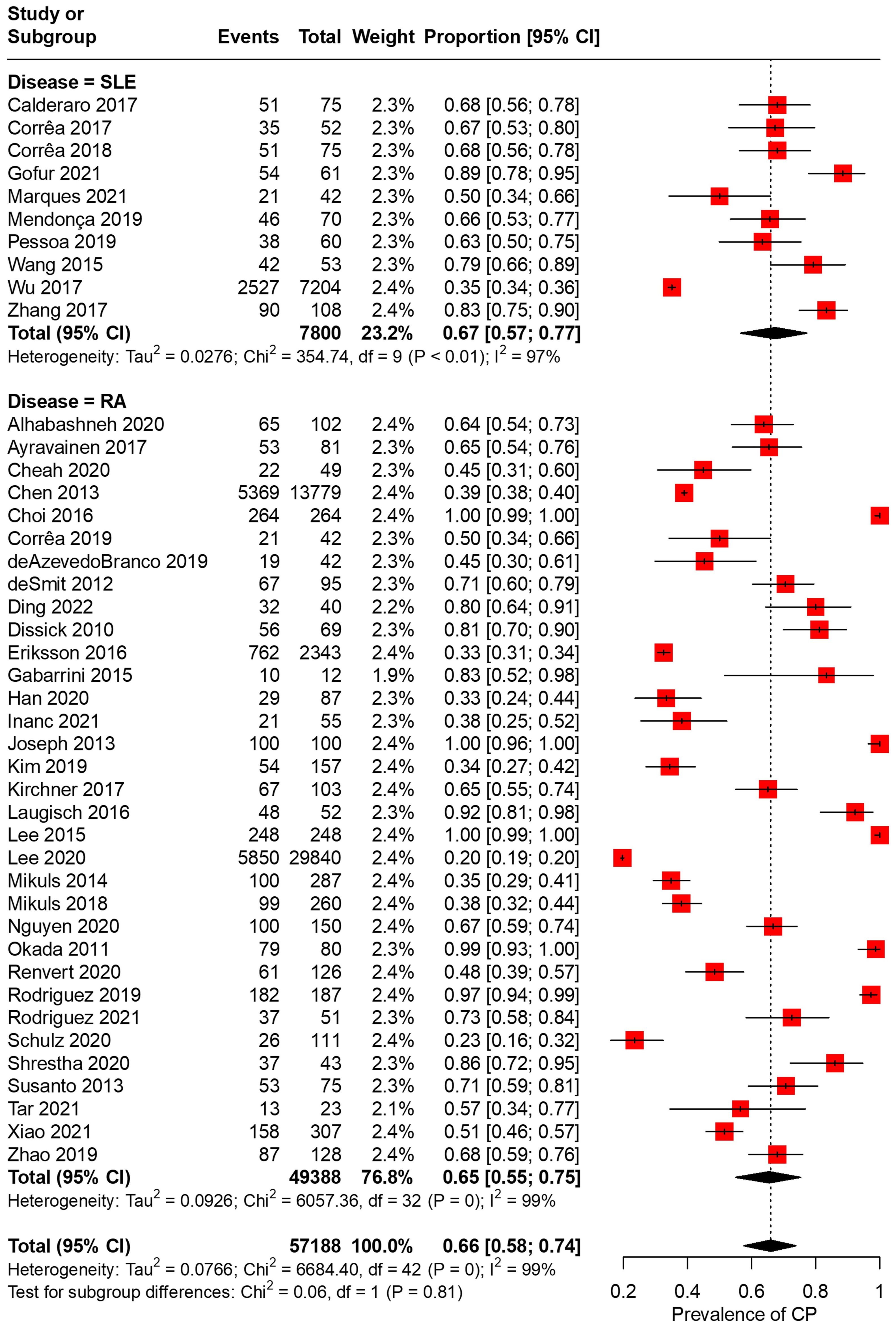

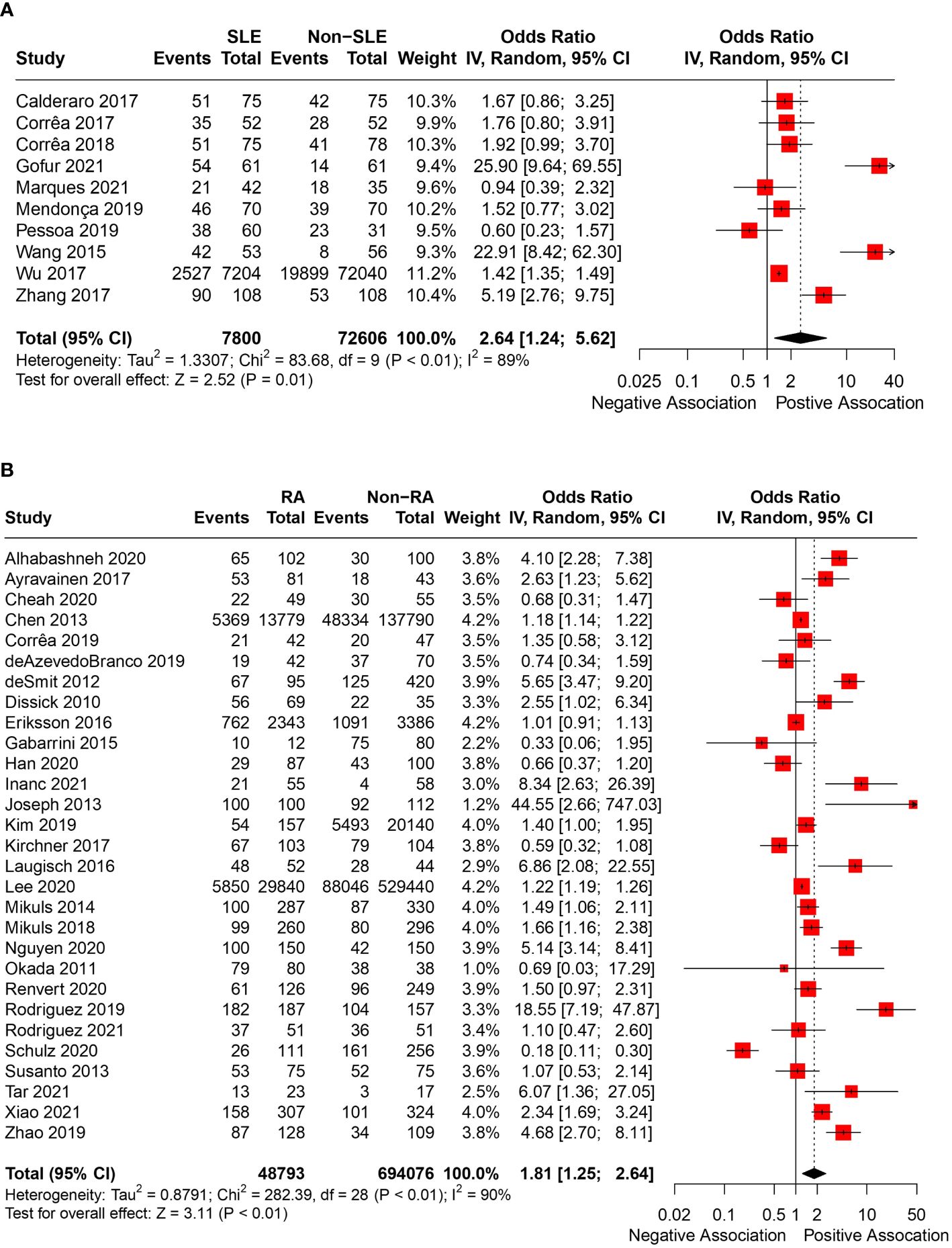

In total, 43 articles were incorporated into this meta-analysis. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the included RA and SLE studies are presented in Supplementary Table 2 and Table 1 , respectively. A total of 7,800 SLE patients and 49,388 RA patients were studied. Most of the studies originated from Brazil, Taiwan, the United States, Korea, Malaysia, and the Netherlands (in descending order). Ongoing treatment for the underlying rheumatic disease included the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, steroid sparers, and biologics such as tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors, where appropriate. Some studies reported the severity of periodontitis in RA and SLE with variability in the criteria used for mild, moderate, or severe periodontitis ascertainment. The various methods used to ascertain periodontitis are shown in Supplementary Table 3 . In total, 2,955 SLE patients and 14,189 RA patients were found to have periodontitis. The combined prevalence of periodontitis in both diseases was 66.0% (95% CI 58.0-74.0%). The pooled prevalence of periodontitis in SLE patients (67.0%, 95% CI 57.0-77.0%) was comparable to that of RA (65.0%, 95% CI 55.0-75.0%) with statistically insignificant subgroup effect (p=0.81) ( Figure 2 ). The pooled prevalence of periodontitis in SLE controls (45.0%, 95% CI 33.0-57.0%) was slightly lower compared to RA controls (52.0%, 95% CI 41.0-64.0%) (p=0.37) ( Supplementary Figure 1 ). Compared to controls, patients with SLE (OR=2.64, 95% CI 1.24-5.62, p<0.01) ( Figure 3A ) and RA (OR=1.81, 95% CI 1.25-2.64, p<0.01) ( Figure 3B ) had significantly greater odds of having periodontitis. 38 articles were included in the NMA. Four articles on RA were excluded because they lacked data on control patients, while one SLE study by Marques et al. was excluded as it enrolled patients with dental diseases as controls ( 33 , 52 , 53 , 71 , 75 ). Figure 4A depicts the network diagram. Indirect comparison through the NMA demonstrated that the odds of having periodontitis in SLE were 1.49 times higher compared to RA (OR=1.49, 95% CI 1.09-2.05, p<0.05), contributed by the lower prevalence of periodontitis in SLE controls relative to RA controls ( Figure 4B ; Supplementary Figure 1 ).

Figure 2 Pooled prevalences of periodontitis in RA and SLE.

Figure 3 (A) Pooled OR of periodontitis in SLE and controls. (B) Pooled OR of periodontitis in RA and controls.

Figure 4 (A) Network plot of the 3 populations. The size of the circles is proportional to the number of subjects in each group. The line widths are proportional to the number of studies in the comparison. (B) Network meta-analysis between harmonized controls, RA and SLE patients.

Supplementary Tables 4 , 5 depict the disease activity of each rheumatic disease and the prevalence/severity of periodontitis if reported. The disease activity indices used were SLEDAI 2000, and DAS28 calculated using erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein (CRP). Owing to the different disease activity scoring systems used and the small number of studies, meta-regression to identify associations between disease activity and periodontitis was not pursued.

3.4 Subgroups analysis

To ascertain the primary sources of heterogeneity, we performed a subgroup analysis based on the classification or diagnostic method of periodontitis, study design (cross-sectional or case-control study), publication year grouping, and whether the studies were published before or after June 2018 ( 1 ). The pooled prevalence of periodontitis in RA was significantly lower in studies published after June 2018 ( Table 2 ).

Table 2 Results of subgroups analysis.

3.5 Publication bias

There was some asymmetry observed on visual inspection of the funnel plot ( Figure 5A ). Egger’s test indicated substantial evidence of publication bias (p< 0.0001). A sensitivity analysis employing the trim-and-fill method was conducted with 22 imputed studies. The trim-and-fill method yielded a lower pooled prevalence of 32.4% (95% CI, 20.6–45.4%) in SLE and RA patients ( Figure 5B ). This suggests that the true pooled prevalence might be less compared to what was found in this study.

Figure 5 (A) Funnel plot of prevalence of periodontitis in RA and SLE patients. (B) Filled funnel plot of prevalence of periodontitis in RA and SLE patients. Solid grey circles represent the 41 studies and open circles denote “filled” studies.

4 Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this meta-analysis and NMA represent the first attempt to compare the prevalence and odds of periodontitis in SLE compared to RA. The principal findings of our meta-analysis and NMA include: (i) the prevalence of periodontitis in patients with SLE was comparable to that of RA, afflicting more than 60% of both patient groups; (ii) both RA and SLE patients exhibited higher odds of having periodontitis compared to controls and (iii) SLE patients were more likely to have periodontitis (1.49-fold higher odds) compared to RA. Similar to previously conducted meta-analyses on periodontitis in patients with RA and SLE, our study showed significantly increased odds of periodontitis in both patient groups compared to controls ( 9 , 10 , 46 , 76 ). RA is the most widely recognised rheumatic disease associated with periodontitis, partly because of the key role of citrullination induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis and the induction of anti-CCP antibodies that are specific for this disease ( 22 ). As a result, the association between RA and periodontitis, as well as dental care considerations specific to RA, have been extensively studied ( 46 , 76 , 77 ). However, the association between SLE and periodontitis is not well recognised by the dental and rheumatology communities (S.H.T., personal communication). Although our study established that there was no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of periodontitis between SLE and RA, it demonstrated that SLE patients have an increased odds of developing periodontitis. Therefore, awareness of the association between SLE and periodontitis is warranted.

The difference in awareness between the associations of periodontitis with RA and SLE may stem from variations in our understanding of their immunopathogenesis. Following the discovery that Porphyromonas gingivalis secretes PPAD ( 22 ), it was hypothesized that periodontitis may accelerate the process of citrullination within the mouth and lead to increased exposure to citrullinated proteins. Consequently, anti-CCP antibodies are produced, which have been linked to more severe RA and joint destruction ( 78 ). Additionally, smoking is known to increase the formation of citrullinated proteins, potentially leading to autoimmunity and the development of RA in susceptible individuals ( 78 ). These lines of evidence provided a clear link between periodontitis and RA. While most observational studies do not fully establish this relationship, the axiomatic understanding that periodontitis and RA share a causal relationship may have provided greater awareness of this association. On the other hand, while the possibility of a bidirectional association between periodontitis and SLE has been proposed, the evidence supporting it remains relatively weak ( 79 ). Several lines of preclinical evidence explanation have supported the association between periodontitis and SLE. First, increased expression of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4, which are involved in innate immune responses, has been observed in both periodontal disease and SLE ( 80 ). Second, the innate immune dysregulation in SLE patients with overactive phagocytic cells leads to elevated production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18, which are implicated in the pathogenesis of periodontitis ( 81 , 82 ). Third, in patients with periodontitis, B lymphocytes and plasma cells are increased in the periodontal tissues. These cells are also the adaptive immune cells implicated in the immunopathogenesis of SLE ( 82 , 83 ). Fourth, periodontal bacteria may stimulate antiphospholipid antibody production through the process of molecular mimicry between bacterial peptides and β2-glycoprotein I ( 41 ). Fifth, a recent Mendelian randomization analysis indicated that periodontitis is associated with a weak causal association with SLE ( 84 ). Lastly, immunosuppression using corticosteroids and steroid sparers leads to a reduction in host immunity and consequently repeated oral infections ( 85 , 86 ).

The most common oral manifestation observed in SLE is painless ulcers typically found in the lip and buccal mucosa ( 87 ). While oral manifestations of SLE have been estimated to vary from 9-45% ( 87 ), owing to the lack of awareness that periodontitis may be associated with SLE, its suspicion may not be entertained, resulting in delayed diagnosis and intervention ( 88 ). Consequently, this delay contributes to poorer dental outcomes, tooth loss, and diminished quality of life among SLE patients ( 4 – 6 ). Despite the burden of periodontitis in SLE, there is a dearth of literature on the awareness of medical professionals on this comorbidity. In contrast, the level of awareness regarding the relationship between periodontitis and RA has been documented in medical literature. Afilal et al. conducted a cross-sectional survey revealing that only 6% of rheumatologists routinely examined the oral cavity, while 11% acknowledged the negative impact of poor oral hygiene on RA, and 10% recommended dental consultation for RA patients ( 89 ). Similarly, Nazir et al. found that 36.2% of dentists were aware of the association between periodontal disease and rheumatoid arthritis ( 90 ). There is a pressing need for studies to explore the level of awareness regarding the association between SLE and periodontitis within the rheumatology and dental communities.

Numerous studies have demonstrated an association between disease activity in RA/SLE and the severity of periodontitis. RA patients with periodontitis categorized as level 0 or 1 exhibited significantly lower mean DAS28-CRP compared to those with level 2 periodontitis ( 62 ). Similarly, SLE patients with higher SLEDAI scores were shown to have more severe periodontal disease ( 91 , 92 ). Furthermore, a randomised controlled trial by Fabbri et al. found that treatment for periodontitis led to a notable reduction in SLEDAI scores ( 93 ). Within 3 months of treatment initiation, a notable decrease in both SLE disease activity and periodontal disease parameters was observed. In contrast, the group without treatment had persistent SLE disease activity and half of the periodontal disease parameters unchanged from baseline ( 93 ). Hence, these findings underscore the importance of raising awareness among clinicians about the association between SLE and periodontitis, as managing this modifiable comorbidity might help to modulate SLE disease activity.

The similar prevalence but increased odds of periodontitis for SLE compared to RA in our analysis deserves discussion. One possible explanation is that SLE patients included in the NMA had relatively higher disease activity compared to RA and therefore had more cases of periodontitis as a result of the bidirectional association ( 79 ). In addition, the lower pooled prevalences of periodontitis in the controls of SLE (45.0%, 95% CI 33.0-57.0%) compared to RA (52.0%, 95% CI 41.0-64.0%) ( Supplementary Figure 1 ) would have contributed to an increased odds of periodontitis for SLE compared to RA.

Rheumatoid arthritis and SLE share several risk-associated loci (e.g., HLA-DRB1 , BLK , UBE2L3 , PTPN22 , STAT4 , TNFAIP3 , FCGR2A , PRDM1 , IRF5 , PXK and COG6 ) and are characterized by the presence of autoantibodies that recognize self-antigens ( 15 , 16 , 31 , 94 ). Environmental triggers such as tobacco smoking have also been described in both diseases, although the prevalence of smoking in both RA and SLE is not well described in epidemiological studies ( 15 , 16 ). Both diseases, however, differ in many aspects such as immunopathogenesis whereby type I interferons in response to viral factors and tumor necrosis factor in relation to microbiota are operational in SLE and RA, respectively ( 15 , 16 ). Specific class II major histocompatibility molecules contain the shared epitope, a specific amino acid motif associated with the risk of developing RA ( 15 ). This epitope facilitates the presentation of arthritogenic peptides to CD4 + T cells, particularly those containing citrulline, thereby promoting the development of anti-CCP antibodies ( 31 ). The interaction between the shared epitope and smoking has been extensively studied and its interplay with Porphyromonas gingivalis in arthritis-prone B6.DR1 mice leading to increased anti-CCP production makes periodontitis an even more compelling risk factor for RA ( 95 ). RA is considered a continuum that begins with a high-risk or susceptibility state influenced by genetic factors and progresses through preclinical, early, and established disease, where environmental factors contribute to the inflammatory and destructive synovial response ( 15 ). Preclinical and early RA are different from rhupus, a disease with features that overlap between RA and SLE ( 31 ). The progression of arthritis in rhupus mirrors a pattern similar to RA, potentially advancing to typical inflammatory erosions. However, the SLE-related aspects in rhupus tend to be milder, primarily manifesting as hematological and mucocutaneous involvement. ( 31 ).

This study has several limitations that should be considered. First, a high heterogeneity was observed. However, in this analysis, heterogeneity was estimated from the I 2 statistic and it is common for proportional meta-analyses to have a high I 2 , possibly because of the nature of the proportional data ( 96 ). The high heterogeneity could also be attributed to variability in the case definition and classification of periodontitis ( 1 , 97 ). Consistent case definition and classification of periodontitis would contribute to reduced heterogeneity. Of note, prevalence of periodontitis decreased in RA patients after the 2017 World Workshop Classification of Periodontal and Peri-implant Diseases and Conditions was published ( Table 2 ), which may reflect reduced heterogeneity in the ascertainment of this odontogenic infection ( 1 ). The other possibility is the improvement of RA treatment over time resulting in decreased periodontitis due to a bidirectional effect. Diagnostic criteria for RA and SLE have not been endorsed by major rheumatology societies and only classification criteria have been developed to recruit homogenous populations for research ( 15 , 16 ). These classification criteria are not intended for use in clinical practice as the basis for establishing the diagnoses of RA and SLE. As such, some RA and SLE patients in the studies that did not specify the classification criteria used were diagnosed clinically. In addition, specific endotypes of RA (e.g., seropositive and seronegative) and SLE (e.g., organ-dominant, lupus with antiphospholipid syndrome and Sjögren’s syndrome) were not reported in the studies ( 98 , 99 ). Hence, transparent reporting of the classification criteria used for classification and any underlying endotypes would have facilitated a more accurate interpretation of our results. Second, evidence of publication bias was detected, suggesting an overestimation of prevalence in our meta-analysis due to potential unpublished studies. Third, due to the many different scoring systems used for disease activity and the limited number of studies, we were unable to perform a meta-regression to explore the relationship between rheumatological disease activity and the prevalence of periodontitis. Fourth, smoking and the use of immunosuppressants may be confounding factors that could contribute to the development of periodontitis. However, these confounding factors were not assessed in many of the included studies and should be analyzed in detail for future work. Lastly, most of the included studies were cross-sectional in design, limiting their ability to establish a causal relationship between periodontitis and SLE. Future well-designed longitudinal, case-control or cohort studies are needed to explore this relationship and determine if temporal and causal links exist between these two conditions ( 100 ). By addressing these limitations, future researchers can help to advance the understanding between periodontitis and rheumatic diseases by improving the quality of the research in this field.

This meta-analysis and NMA established that SLE patients have a significantly higher likelihood of experiencing periodontitis (1.49-fold higher odds) compared to RA, although no significant difference in the prevalence of periodontitis was found between RA and SLE. Considering that RA is traditionally linked with periodontal disease, the elevated odds of periodontitis in SLE are striking. Irrespective of the highlighted limitations, especially that of variations in periodontitis assessment criteria among the studies, these results underscore the importance of addressing the dental health needs of SLE patients. Future research should explore the extent of awareness regarding the association between SLE and periodontitis within the dental and rheumatology communities. Enhancing awareness among healthcare providers and enhancing educational efforts in both disciplines will be crucial in alleviating the considerable disease burden of periodontitis in SLE. Further clinical and translational research is warranted to advance the understanding of periodontitis and its broad impact on SLE immunopathogenesis and disease activity.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material . Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

PT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization. AL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JZ: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YC: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JF: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MM: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ST: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1356714/full#supplementary-material

1. Tonetti MS, Greenwell H, Kornman KS. Staging and grading of periodontitis: Framework and proposal of a new classification and case definition. J Periodontol . (2018) 89 Suppl 1:S159–s172. doi: 10.1002/JPER.18-0006

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Könönen E, Gursoy M, Gursoy UK. Periodontitis: A multifaceted disease of tooth-supporting tissues. J Clin Med . (2019) 8. doi: 10.3390/jcm8081135

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Van Dyke TE, Bartold PM, Reynolds EC. The nexus between periodontal inflammation and dysbiosis. Front Immunol . (2020) 11:511. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00511

4. Tonetti MS, Jepsen S, Jin L, Otomo-Corgel J. Impact of the global burden of periodontal diseases on health, nutrition and wellbeing of mankind: A call for global action. J Clin Periodontol . (2017) 44:456–62. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12732

5. Reynolds I, Duane B. Periodontal disease has an impact on patients' quality of life. Evid Based Dent . (2018) 19:14–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6401287

6. Nazir M, Al-Ansari A, Al-Khalifa K, Alhareky M, Gaffar B, Almas K. Global prevalence of periodontal disease and lack of its surveillance. ScientificWorldJournal . (2020) 2020. doi: 10.1155/2020/2146160

7. Winning L, Linden GJ. Periodontitis and systemic disease. BDJ Team . (2015) 2:15163. doi: 10.1038/bdjteam.2015.163

8. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet . (2017) 390:1211–59. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32154-2

9. Rutter-Locher Z, Smith TO, Giles I, Sofat N. Association between systemic lupus erythematosus and periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Immunol . (2017) 8:1295. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01295

10. Zhong HJ, Xie HX, Luo XM, Zhang EH. Association between periodontitis and systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis. Lupus . (2020) 29:1189–97. doi: 10.1177/0961203320938447

11. Li Y, Guo R, Oduro PK, Sun T, Chen H, Yi Y, et al. The relationship between porphyromonas gingivalis and rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol . (2022) 12:956417. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.956417

12. Aljohani K, Alzahrani AS. Awareness among medical and dental students regarding the relationship between periodontal and systemic conditions. Int J Pharm Res Allied Sci . (2017) 6:61–72.

Google Scholar

13. Park H, Bourla AB, Kastner DL, Colbert RA, Siegel RM. Lighting the fires within: the cell biology of autoinflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol . (2012) 12:570–80. doi: 10.1038/nri3261

14. Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Carmona L, Wolfe F, Vos T, et al. The global burden of rheumatoid arthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis . (2014) 73:1316–22. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204627

15. Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Barton A, Burmester GR, Emery P, Firestein GS, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers . (2018) 4:18001. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.1

16. Kaul A, Gordon C, Crow MK, Touma Z, Urowitz MB, Van Vollenhoven R, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Dis Primers . (2016) 2:16039. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.39

17. Lewis MJ, Jawad AS. The effect of ethnicity and genetic ancestry on the epidemiology, clinical features and outcome of systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology . (2017) 56:i67–77. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew399

18. Ballestar E, Li T. New insights into the epigenetics of inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol . (2017) 13:593–605. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2017.147

19. Deane KD, Demoruelle MK, Kelmenson LB, Kuhn KA, Norris JM, Holers VM. Genetic and environmental risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol . (2017) 31:3–18. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2017.08.003

20. Moulton VR, Suarez-Fueyo A, Meidan E, Li H, Mizui M, Tsokos GC. Pathogenesis of human systemic lupus erythematosus: A cellular perspective. Trends Mol Med . (2017) 23:615–35. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2017.05.006

21. Cusick MF, Libbey JE, Fujinami RS. Molecular mimicry as a mechanism of autoimmune disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol . (2012) 42:102–11. doi: 10.1007/s12016-011-8294-7

22. Olsen I, Singhrao SK, Potempa J. Citrullination as a plausible link to periodontitis, rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis and Alzheimer's disease. J Oral Microbiol . (2018) 10:1487742. doi: 10.1080/20002297.2018.1487742

23. Koziel J, Mydel P, Potempa J. The link between periodontal disease and rheumatoid arthritis: an updated review. Curr Rheumatol Rep . (2014) 16:408. doi: 10.1007/s11926-014-0408-9

24. Dissick A, Redman RS, Jones M, Rangan BV, Reimold A, Griffiths GR, et al. Association of periodontitis with rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot study. J Periodontol . (2010) 81:223–30. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090309

25. Eezammuddeen NN, Vaithilingam RD, Hassan NHM. Influence of periodontitis on levels of autoantibodies in rheumatoid arthritis patients: A systematic review. J Periodontal Res . (2023) 58:29–42. doi: 10.1111/jre.13065

26. Zhang J, Xu C, Gao L, Zhang D, Li C, Liu J. Influence of anti-rheumatic agents on the periodontal condition of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontal Res . (2021) 56:1099–115. doi: 10.1111/jre.12925

27. Rutter-Locher Z, Smith TO, Giles I, Sofat N. Association between systemic lupus erythematosus and periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Immunol . (2017) 8. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01295

28. Hussain SB, Leira Y, Zehra SA, Botelho J, MaChado V, Ciurtin C, et al. Periodontitis and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontal Res . (2022) 57:1–10. doi: 10.1111/jre.12936

29. Amezcua-Guerra LM, Springall R, Marquez-Velasco R, Gómez-García L, Vargas A, Bojalil R. Presence of antibodies against cyclic citrullinated peptides in patients with 'rhupus': a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Res Ther . (2006) 8:R144. doi: 10.1186/ar2036

30. Martínez REM, Herrera JLA, Pérez RAD, Mendoza CA, Manrique SIR. Frequency of Porphyromonas gingivalis and fimA genotypes in patients with periodontitis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus . (2021) 30:80–5. doi: 10.1177/0961203320969983

31. Antonini L, Le Mauff B, Marcelli C, Aouba A, De Boysson H. Rhupus: a systematic literature review. Autoimmun Rev . (2020) 19:102612. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102612

32. Gofur NRP, Handono K, Nurdiana N, Kalim H. Periodontal comparison on systemic lupus erythematosus patients and healthy subjects: A cross-sectional study. Pesqui Bras Odontopediatria Clín Integr . (2021) 21. doi: 10.1590/pboci.2021.108

33. Marques CPC, Rodrigues VP, De Carvalho LC, Nichilatti LP, Franco MM, Patrício FJB, et al. Expression of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 in the saliva of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and chronic periodontitis. Clin Rheumatol . (2021) 40:2727–34. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05560-z

34. Pessoa L, Aleti G, Choudhury S, Nguyen D, Yaskell T, Zhang Y, et al. Host-microbial interactions in systemic lupus erythematosus and periodontitis. Front Immunol . (2019) 10:2602. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02602

35. Mendonça SMS, Corrêa JD, Souza AF, Travassos DV, Calderaro DC, Rocha NP, et al. Immunological signatures in saliva of systemic lupus erythematosus patients: influence of periodontal condition. Clin Exp Rheumatol . (2019) 37:208–14.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

36. Corrêa JD, Branco LGA, Calderaro DC, Mendonça SMS, Travassos DV, Ferreira GA, et al. Impact of systemic lupus erythematosus on oral health-related quality of life. Lupus . (2018) 27:283–9. doi: 10.1177/0961203317719147

37. Zhang Q, Zhang X, Feng G, Fu T, Yin R, Zhang L, et al. Periodontal disease in Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int . (2017) 37:1373–9. doi: 10.1007/s00296-017-3759-5

38. Wu YD, Lin CH, Chao WC, Liao TL, Chen DY, Chen HH. Association between a history of periodontitis and the risk of systemic lupus erythematosus in Taiwan: A nationwide, population-based, case-control study. PloS One . (2017) 12:e0187075. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187075

39. Corrêa JD, Calderaro DC, Ferreira GA, Mendonça SM, Fernandes GR, Xiao E, et al. Subgingival microbiota dysbiosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: association with periodontal status. Microbiome . (2017) 5:34. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0252-z

40. Calderaro DC, Ferreira GA, Corrêa JD, Mendonça SM, Silva TA, Costa FO, et al. Is chronic periodontitis premature in systemic lupus erythematosus patients? Clin Rheumatol . (2017) 36:713–8. doi: 10.1007/s10067-016-3385-8

41. Wang CY, Chyuan IT, Wang YL, Kuo MY, Chang CW, Wu KJ, et al. β2-glycoprotein I-dependent anti-cardiolipin antibodies associated with periodontitis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Periodontol . (2015) 86:995–1004. doi: 10.1902/jop.2015.140664

42. Wells G, Shea B, O'connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses . (2009). Available at: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp .

43. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj . (1997) 315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

44. Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics . (2000) 56:455–63. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x

45. Okada M, Kobayashi T, Ito S, Yokoyama T, Komatsu Y, Abe A, et al. Antibody responses to periodontopathic bacteria in relation to rheumatoid arthritis in Japanese adults. J Periodontol . (2011) 82:1433–41. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.110020

46. De Smit M, Westra J, Vissink A, Doornbos-Van Der Meer B, Brouwer E, Van Winkelhoff AJ. Periodontitis in established rheumatoid arthritis patients: a cross-sectional clinical, microbiological and serological study. Arthritis Res Ther . (2012) 14:R222. doi: 10.1186/ar4061

47. Chen HH, Huang N, Chen YM, Chen TJ, Chou P, Lee YL, et al. Association between a history of periodontitis and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: a nationwide, population-based, case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis . (2013) 72:1206–11. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201593

48. Joseph R, Rajappan S, Nath SG, Paul BJ. Association between chronic periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis: a hospital-based case-control study. Rheumatol Int . (2013) 33:103–9. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-2284-1

49. Susanto H, Nesse W, Kertia N, Soeroso J, Huijser Van Reenen Y, Hoedemaker E, et al. Prevalence and severity of periodontitis in Indonesian patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Periodontol . (2013) 84:1067–74. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110321

50. Mikuls TR, Payne JB, Yu F, Thiele GM, Reynolds RJ, Cannon GW, et al. Periodontitis and Porphyromonas gingivalis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol . (2014) 66:1090–100. doi: 10.1002/art.38348

51. Gabarrini G, De Smit M, Westra J, Brouwer E, Vissink A, Zhou K, et al. The peptidylarginine deiminase gene is a conserved feature of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Sci Rep . (2015) 5:13936. doi: 10.1038/srep13936

52. Lee JY, Choi IA, Kim JH, Kim KH, Lee EY, Lee EB, et al. Association between anti-Porphyromonas gingivalis or anti-α-enolase antibody and severity of periodontitis or rheumatoid arthritis (RA) disease activity in RA. BMC Musculoskelet Disord . (2015) 16:190. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0647-6

53. Choi IA, Kim JH, Kim YM, Lee JY, Kim KH, Lee EY, et al. Periodontitis is associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a study with longstanding rheumatoid arthritis patients in Korea. Korean J Intern Med . (2016) 31:977–86. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2015.202

54. Eriksson K, Nise L, Kats A, Luttropp E, Catrina AI, Askling J, et al. Prevalence of periodontitis in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis: A swedish population based case-control study. PloS One . (2016) 11:e0155956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155956

55. Laugisch O, Wong A, Sroka A, Kantyka T, Koziel J, Neuhaus K, et al. Citrullination in the periodontium–a possible link between periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Oral Investig . (2016) 20:675–83. doi: 10.1007/s00784-015-1556-7

56. Äyräväinen L, Leirisalo-Repo M, Kuuliala A, Ahola K, Koivuniemi R, Meurman JH, et al. Periodontitis in early and chronic rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective follow-up study in Finnish population. BMJ Open . (2017) 7:e011916. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011916

57. Kirchner A, Jäger J, Krohn-Grimberghe B, Patschan S, Kottmann T, Schmalz G, et al. Active matrix metalloproteinase-8 and periodontal bacteria depending on periodontal status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Periodontal Res . (2017) 52:745–54. doi: 10.1111/jre.12443

58. Mikuls TR, Walker C, Qiu F, Yu F, Thiele GM, Alfant B, et al. The subgingival microbiome in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol (Oxford) . (2018) 57:1162–72. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key052

59. Corrêa JD, Fernandes GR, Calderaro DC, Mendonça SMS, Silva JM, Albiero ML, et al. Oral microbial dysbiosis linked to worsened periodontal condition in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Sci Rep . (2019) 9:8379. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44674-6

60. De Azevedo Branco LG, Oliveira SR, Corrêa JD, Calderaro DC, Mendonça SMS, De Queiroz Cunha F, et al. Oral health-related quality of life among individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol . (2019) 38:2433–41. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04555-9

61. Kim JW, Park JB, Yim HW, Lee J, Kwok SK, Ju JH, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis is associated with early tooth loss: results from Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey V to VI. Korean J Intern Med . (2019) 34:1381–91. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2018.093

62. Rodríguez-Lozano B, González-Febles J, Garnier-Rodríguez JL, Dadlani S, Bustabad-Reyes S, Sanz M, et al. Association between severity of periodontitis and clinical activity in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a case-control study. Arthritis Res Ther . (2019) 21:27. doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-1808-z

63. Zhao R, Gu C, Zhang Q, Zhou W, Feng G, Feng X, et al. Periodontal disease in Chinese patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A case-control study. Oral Dis . (2019) 25:2003–9. doi: 10.1111/odi.13176

64. Alhabashneh R, Alawneh K, Alshami R, Al Naji K. Rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis: a Jordanian case-control study. J Public Health . (2020) 28:547–54. doi: 10.1007/s10389-019-01073-5

65. Cheah CW, Al-Maleki AR, Vadivelu J, Danaee M, Sockalingam S, Baharuddin NA, et al. Salivary and serum cathelicidin LL-37 levels in subjects with rheumatoid arthritis and chronic periodontitis. Int J Rheumatic Dis . (2020) 23:1344–52. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13919

66. Han PSH, Saub R, Baharuddin NA, Sockalingam S, Bartold PM, Vaithilingam RD. Impact of periodontitis on quality of life among subjects with rheumatoid arthritis: a cross sectional study. BMC Oral Health . (2020) 20:332. doi: 10.1186/s12903-020-01275-4

67. Lee KH, Choi YY. Rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis in adults: Using the Korean National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort. J Periodontol . (2020) 91:1186–93. doi: 10.1002/JPER.19-0311

68. Nguyen VB, Nguyen TT, Huynh NC, Le TA, Hoang HT. Relationship between periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis in Vietnamese patients. Acta Odontol Scand . (2020) 78:522–8. doi: 10.1080/00016357.2020.1747635

69. Renvert S, Berglund JS, Persson GR, Söderlin MK. The association between rheumatoid arthritis and periodontal disease in a population-based cross-sectional case-control study. BMC Rheumatol . (2020) 4:31. doi: 10.1186/s41927-020-00129-4

70. Schulz S, Zimmer P, Pütz N, Jurianz E, Schaller H-G, Reichert S. rs2476601 in PTPN22 gene in rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis—a possible interface? J Trans Med . (2020) 18:389. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02548-w

71. Shrestha S, Pradhan S, Adhikari B. Prevalence of periodontitis among rheumatoid arthritis patients attending tertiary hospital in Nepal. J Nepal Health Res Counc . (2020) 17:543–7. doi: 10.33314/jnhrc.v17i4

72. Inanc N, Mumcu G, Can M, Yay M, Silbereisen A, Manoil D, et al. Elevated serum TREM-1 is associated with periodontitis and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Rep . (2021) 11:2888. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-82335-9

73. Rodríguez J, Lafaurie GI, Bautista-Molano W, Chila-Moreno L, Bello-Gualtero JM, Romero-Sánchez C. Adipokines and periodontal markers as risk indicators of early rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional study. Clin Oral Investig . (2021) 25:1685–95. doi: 10.1007/s00784-020-03469-0

74. Tar I, Csősz É., Végh E, Lundberg K, Kharlamova N, Soós B, et al. Salivary citrullinated proteins in rheumatoid arthritis and associated periodontal disease. Sci Rep . (2021) 11:13525. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93008-y

75. Ding N, Luo M, Wen YH, Li RY, Bao QY. The effects of non-surgical periodontitis therapy on the clinical features and serological parameters of patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis as well as chronic periodontitis. J Inflammation Res . (2022) 15:177–85. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S326896

76. Mercado FB, Marshall RI, Klestov AC, Bartold PM. Relationship between rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis. J Periodontol . (2001) 72:779–87. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.6.779

77. Treister N, Glick M. Rheumatoid arthritis: a review and suggested dental care considerations. J Am Dent Assoc . (1999) 130:689–98. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0279

78. Alsalahy MM, Nasser HS, Hashem MM, Elsayed SM. Effect of tobacco smoking on tissue protein citrullination and disease progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Saudi Pharm J . (2010) 18:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2010.02.002

79. Sojod B, Pidorodeski Nagano C, Garcia Lopez GM, Zalcberg A, Dridi SM, Anagnostou F. Systemic lupus erythematosus and periodontal disease: A complex clinical and biological interplay. J Clin Med . (2021) 10. doi: 10.3390/jcm10091957