Read our research on: Abortion | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Before covid-19, more mexicans came to the u.s. than left for mexico for the first time in years.

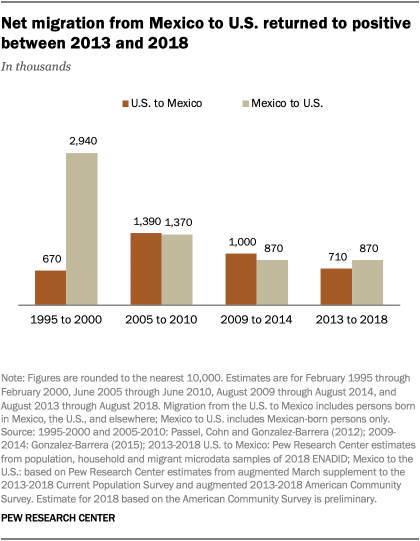

More Mexican migrants came to the United States than left the U.S. for Mexico between 2013 and 2018 – a reversal of the trend in much of the prior decade, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of the most recently available data capturing migration flows from both countries.

An estimated 870,000 Mexican migrants came to the U.S. between 2013 and 2018, while an estimated 710,000 left the U.S. for Mexico during that period. That translates to net migration of about 160,000 people from Mexico to the U.S., according to government data from both countries.

In the period from 2009 to 2014, by contrast, about a million people left the U.S. for Mexico while 870,000 Mexicans made the reverse trip, for net migration of about 130,000 people from the U.S. to Mexico. A similar trend from 2005 to 2010 resulted in effectively zero net migration between the two countries. (Due to the way the Mexican government sources report data, this analysis uses several overlapping time periods: 2005-2010, for example, and 2009-2014. In addition, migration from Mexico in this analysis includes only those who were born there, while migration to Mexico includes those born in Mexico, the U.S., and elsewhere.)

Measuring migration flows between Mexico and the U.S. is challenging because there are no official counts of how many Mexican immigrants enter and leave the U.S. each year. This analysis uses the best available government data from both countries to estimate the size of these flows. For this analysis, migration from the U.S. to Mexico includes persons born in Mexico, the U.S., and elsewhere, while migration from Mexico to the U.S. includes Mexican-born persons only.

To estimate how many people have left the U.S. for Mexico, this analysis uses data from the 2018 and 2014 Mexican National Survey of Demographic Dynamics (or ENADID) and the 2020, 2010 and 2000 Mexican decennial censuses. Respondents are asked where they had been living five years prior to the date when the survey or census was taken. The answers to this question provide an estimate of the number of people who moved from the U.S. to Mexico during the five years prior to the survey date. A separate question focuses on those who have recently left Mexico. It asks whether anyone from the household had left for another country during the previous five years; if so, additional questions are asked about whether and when that person or people came back and their reasons for returning to Mexico.

To estimate how many Mexicans left Mexico for the U.S., this analysis uses the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (2005-2019) and the Current Population Survey (1990-2019), which ask immigrants living in the U.S. about their country of birth and the year of their arrival in the U.S. Both sources are adjusted for undercount.

Other sources of information include detailed tables released by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Immigration Statistics, the U.S. Department of State, and U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

The main change in net flow between the two countries in the most recent period comes from the decreased return flow from the U.S. to Mexico – 1.0 million from 2009 to 2014 down to 710,000 from 2013 to 2018 – rather than an increase in the number of Mexican immigrants coming to the U.S. The number of Mexican immigrants going from Mexico to the U.S. stood unchanged at 870,000 for both 2009 to 2014 and 2013 to 2018.

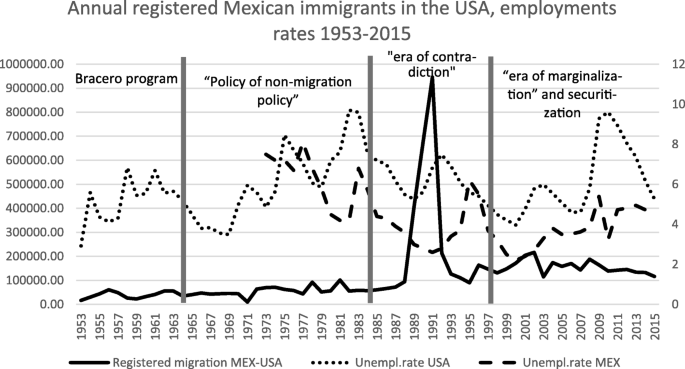

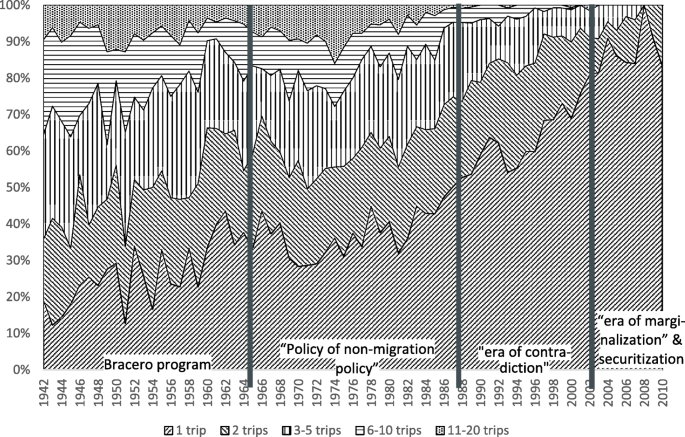

There are several potential reasons for the changing patterns of migration flows between the two nations. In the U.S., job losses during the Great Recession of 2007-2009 in industries in which immigrants tend to be heavily represented may have pushed a large number of Mexicans to migrate back to Mexico, which in the aftermath of the recession also made the U.S. less attractive to potential Mexican migrants. In addition, stricter enforcement of U.S. immigration laws both at the southwest border and within the interior of the U.S. may have contributed to the reduction in Mexican immigrants coming to the U.S. in the years leading up to 2013.

Some changing patterns in Mexico could also be behind the reduction in the number of immigrants coming to the U.S. since the Great Recession. First, growth in the working-age population of Mexicans has slowed due to a decades-long decline in the average number of births among women in Mexico. Lower fertility rates also mean smaller family sizes, which reduces the need for migration as a means of family financial support. Coupled with this, the Mexican economy over the past two decades has been more stable than in the 1980s and 1990s, when the country was hit with a number of profound economic crises.

While net migration from Mexico to the U.S. turned positive from 2013 to 2018 for the first time in more than a decade, it remained far below the levels seen in earlier decades when migration from Mexico to the U.S. was at its peak. In the five-year period between 1995 and 2000, for example, nearly 3 million immigrants came to the U.S. from Mexico, while only around 670,000 made the reverse trip, for net migration of nearly 2.3 million people from Mexico to the U.S.

Mexico is the largest country of birth among the estimated 47 million immigrants living in the U.S., according to preliminary estimates based on the 2019 American Community Survey. About 24% of all U.S. immigrants were born in Mexico.

Total number of Mexican immigrants living in the U.S. declined between 2007 and 2019

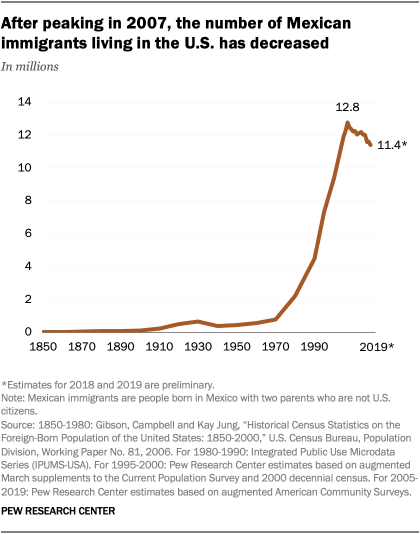

After peaking at 12.8 million in 2007, the number of Mexican immigrants living in the U.S. has declined in recent years. Preliminary estimates show that in 2019, the overall population of Mexican immigrants in the U.S. was 11.4 million, or about 1.4 million below the number at the onset of the Great Recession.

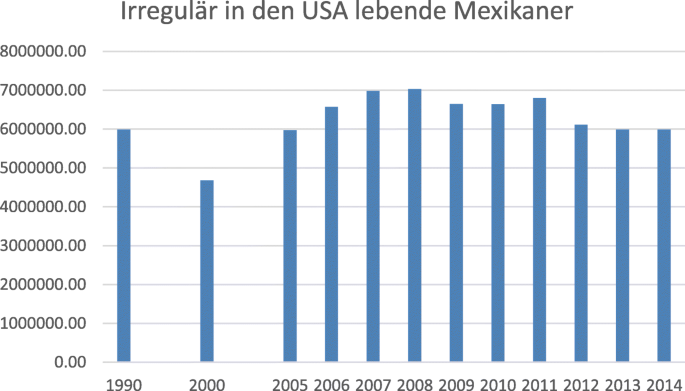

The decline in Mexican immigrants in the U.S. has been due mostly to a decrease of about 2 million unauthorized Mexican immigrants, from a peak of 6.9 million in 2007 to an estimated 4.9 million in 2017 , according to Pew Research Center’s latest estimate of the unauthorized population in the U.S.

Mexican immigrants have been at the center of one of the largest mass migrations in modern history. Between 1965 and 2015, more than 16 million Mexican immigrants migrated to the U.S. – more than from any other country.

In 1970, fewer than 1 million Mexican immigrants lived in the U.S. By 2000, that number had grown to 9.4 million, and by 2007 it peaked at 12.8 million.

The amount of Mexican migration during coronavirus outbreak remains unclear

At the start of the coronavirus pandemic , the U.S. and Mexican governments shut down their land borders to all non-essential travel, and the U.S. has yet to reopen them after more than a year. Travel in most of the world was disrupted during the pandemic and migration flows seemed to dwindle. However, it is still unclear how the coronavirus pandemic has affected migration flows from Mexico to the U.S. and vice versa. The two main sources for this kind of information, the U.S. Census Bureau’s surveys and the Mexican government’s INEGI data, are not yet available for the period covering the pandemic, while other data sources only offer a partial view. These secondary sources, however, do hint at some of the changes that might be underway since the coronavirus outbreak started.

One of these data points is the number of immigrants who entered the U.S. in fiscal 2020 through permanent legal residency , also known as a “green card.” In fiscal 2020, about 30,500 Mexican immigrants entered the U.S. this way, down 45% from the prior year. The reduction during the fiscal year, which ran from Oct. 1, 2019, to Sept. 30, 2020, was particularly notable in the months after the coronavirus outbreak began: Between April and September 2020, the number of Mexican green card recipients dropped by 90% compared with the same period in the prior year.

Another available data point is the number of Mexican immigrants who entered the U.S. through a temporary work visa , such as the H-2A visa for farmworkers, or the TN or H-1B visas for high-skilled immigrants. In fiscal 2020, Mexican farmworkers obtained about 198,000 temporary permits to come work in the U.S., up 5% from the prior fiscal year – an annual increase far lower than those seen in most years leading up to the pandemic. Meanwhile, the number of high-skilled Mexican workers who obtained a TN or H-1B visa dropped 36% in the same period, from about 24,000 to 15,000.

Another snapshot of Mexican immigration flows relates to unauthorized immigrants, including those who come to the U.S. temporarily on a visa and overstay their permit and those who cross the border without inspection and reside in the U.S. as unauthorized immigrants.

While data on visa overstays during the pandemic is not available, the number of people traveling into the U.S. during the pandemic went down and the number of non-immigrant visas issued in Mexico also declined. In fiscal 2020, the total number of non-immigrant visas processed in Mexico by the U.S. Department of State dropped 35% compared with the prior year, from about 1.5 million in 2019 to about 960,000 in 2020. Most of these temporary visas were processed for tourism, business or for crossing the border and do not include a work authorization.

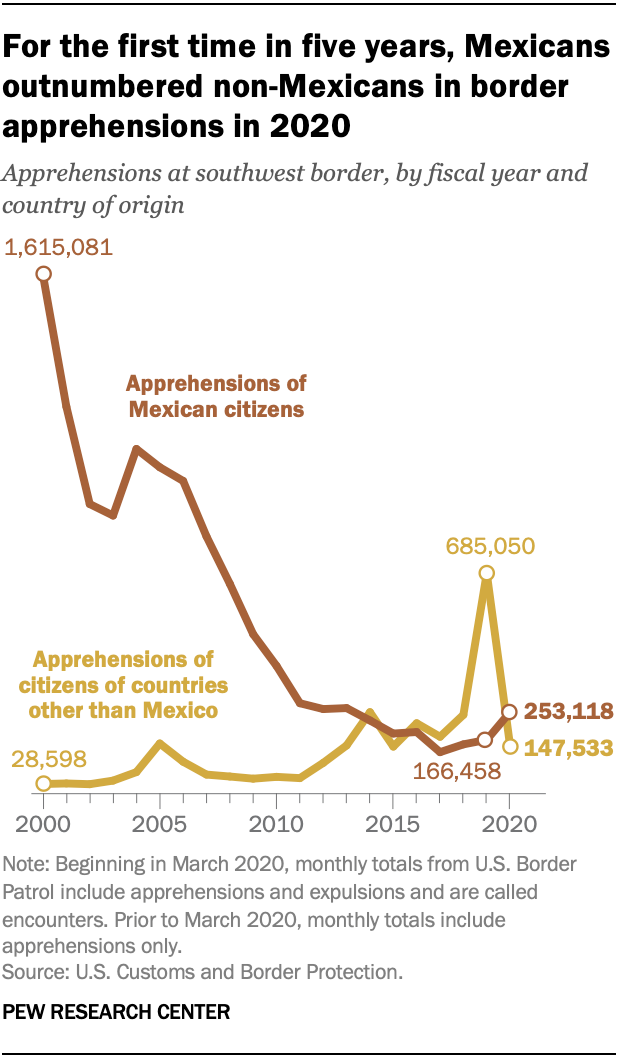

By contrast, apprehensions of unauthorized Mexican immigrants – a statistic that is often used as a proxy for measuring illegal immigration – increased considerably after the pandemic started in 2020, even as apprehensions of non-Mexicans dropped sharply . In fiscal 2020, the number of encounters or apprehensions of Mexican adults at the U.S.-Mexican border reached levels not seen since 2013 . There were 253,118 such encounters, up 52% from 166,458 the year before.

It is important to note that apprehensions at the border were handled differently in fiscal 2020 than in years immediately prior due to an executive order called Title 42 , authorized by former President Donald Trump. Under the order, Border Patrol agents did not always conduct a formal apprehension and removal, but instead sent immigrants directly back to Mexico without those steps.

Some analysts say that the new procedures have increased the number of immigrants from Mexico and elsewhere who try to enter the U.S. illegally multiple times. The number of immigrants with a prior encounter with a Border Patrol agent increased considerably in fiscal year 2020, according U.S. Customs and Enforcement data .

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

Key findings about Black immigrants in the U.S.

Recently arrived u.s. immigrants, growing in number, differ from long-term residents, facts on u.s. immigrants, 2017, immigrant share in u.s. nears record high but remains below that of many other countries, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Weekly U.S.-Mexico Border Update: Mexico crackdown, no spring migration increase, Texas, Guatemala

With this series of weekly updates, WOLA seeks to cover the most important developments at the U.S.-Mexico border. See past weekly updates here .

Support ad-free, paywall-free Weekly Border Updates. Your donation to WOLA is crucial to sustain this effort. Please contribute now and support our work.

THIS WEEK IN BRIEF:

Mexico’s intensified enforcement delays the united states’ expected spring migration increase.

Migration at the U.S.-Mexico border usually increases in springtime. That is not happening in 2024, although numbers are up in Mexico and further south. Increased Mexican government operations to block or hinder migrants are a central reason. Especially striking is migration from Venezuela, which has plummeted at the U.S. border and moved largely to ports of entry. It is unclear why Venezuelan migration has dropped more steeply than that from other nations.

Insights from CBP’s February reporting about the border

Migration at the U.S.-Mexico border increased by 8 percent from January to February; the portion that is Border Patrol apprehensions of migrants grew by 13 percent. February’s levels were still on the low end for the Biden administration. Preliminary March data indicate no further increases this month.

Is Texas’s crackdown pushing migrants to other states?

Texas’s governor, an immigration hardliner, is claiming credit for a westward shift of migration toward Arizona and California. Uncertainty over a harsh new law—currently blocked in the courts—could be leading some migrants to avoid Texas, but the overall picture is more complex. Migration declined slightly in Arizona in February and is still dropping there in March, while four out of five Texas border sectors saw some growth in February.

Migration on the agenda of Guatemalan President’s visit to Washington

President Bernardo Arévalo of Guatemala, in his third month in office, paid his first official visit to Washington, meeting separately with President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris. The White House touted $170 million in new assistance to Guatemala and the operations of a U.S.-backed “Safe Mobility Office” that seeks to steer would-be migrants toward legal pathways. In 2023, Guatemala’s previous government expelled more than 23,000 U.S.-bound migrants, most of them from Venezuela, back across its border into Honduras.

THE FULL UPDATE:

“ The spring migration increase is underway ,” read WOLA’s March 8 Border Update. This statement reflected early reports of a 13 percent increase in Border Patrol apprehensions of migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border from January to February. (Those early reports were correct, as discussed below .)

However, this increase has leveled off or may even be reversing in March . That rarely happens in spring, a season when the border usually sees a jump in migration as temperatures warm, but not to extremes.

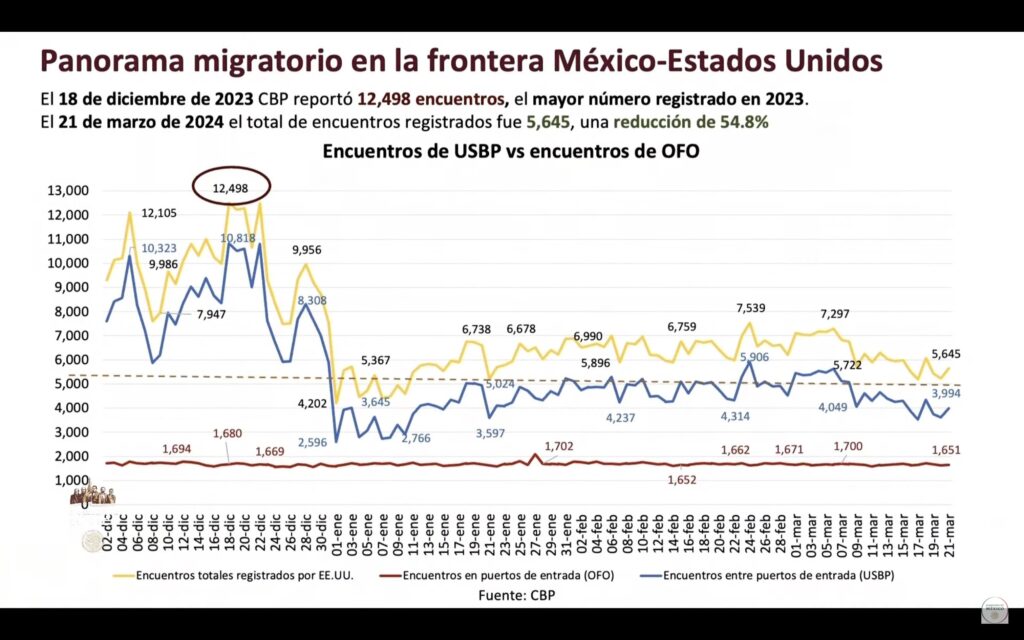

Customs and Border Protection (CBP) encountered 6,307 migrants per day at the U.S.-Mexico border during the first 21 days of March, including the approximately 1,450 per day who made CBP One appointments at border ports of entry, according to slides posted by Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, at his March 26 morning press conference .

That preliminary March average is smaller than CBP’s daily average in February (6,549, more statistics below ). If this holds—we’ll find out in the second half of April, when CBP releases final March numbers—then 2024 could be only the second year this century in which migration declined from February to March . (The other year was 2017, when migration dropped sharply in the three months after Donald Trump’s January inauguration.)

Meanwhile, on March 25 Mexico’s government published data through February showing that its migration authorities encountered almost exactly 120,000 migrants in both January and February. Before January, Mexico’s monthly record for migrant encounters was about 98,000. This is evidence that Mexico’s government has stepped up interdiction of migrants in its territory so far in 2024.

A New York Times analysis found that Mexico’s government’s ability and willingness to help control migration flows make it “a key player on an issue with the potential to sway the election” in the United States. However, “behind closed doors, some senior Biden officials have come to see López Obrador as an unpredictable partner, who they say isn’t doing enough to consistently control his own southern border or police routes being used by smugglers.”

Meanwhile, migration continues at high levels further south. Officials in Panama reported that the number of migrants crossing the Darién Gap so far in 2024 has now exceeded 101,000. At the end of February, the number stood at 73,167; this means that the March pace in the Darién Gap remains, as in January and February, at a bit over 1,200 people per day . Of this year’s migrants, nearly two thirds (64,307) are citizens of Venezuela.

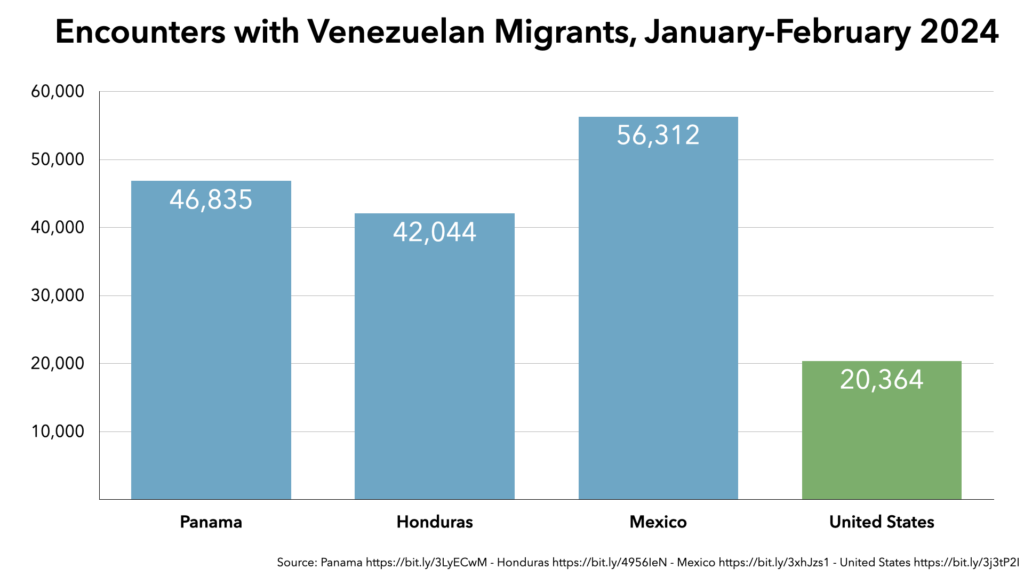

The March data show that U.S. encounters with migrants from Venezuela continue to be far fewer than the past two years’ monthly averages. Venezuelan migrants’ numbers dropped sharply in January and have not recovered: they totaled 20,364 in January and February combined, just over one-third of what they were in December alone (57,850). Meanwhile, Mexico reported 56,312 encounters with Venezuelan citizens in January and February—almost 3 times the U.S. figure .

That points to a strong likelihood that the Venezuelan population is increasing sharply within Mexico right now . The Associated Press confirmed that Mexico’s increased operations to block migrants have many Venezuelan citizens stranded in the country’s south, including in Mexico City, which is within the geographic range of the CBP One app and its limited number of available appointments.

U.S. authorities’ encounters with Venezuelan migrants haven’t just dropped in aggregate terms. The percentage of Venezuelans crossing between ports of entry has also fallen, from a strong majority to just 37 percent since January. This means that a majority of Venezuelan migrants are now making CBP One appointments .

Meanwhile, this week Mexico’s government reached an agreement with Venezuela’s government to facilitate aerial deportations to Caracas. As part of the deal, some of Mexico’s largest corporations with presences in South America would employ Venezuelan deportees, paying them a “stipend” of US$110 per month for a six-month period. “We’re sending Venezuelans back to their country because we really cannot handle these quantities,” said Foreign Minister Alicia Bárcena.

At his March 26 press conference , López Obrador added that he is seeking to expand this program to citizens of Colombia and Ecuador. Participants in a “Migrant Via Crucis” march through Mexico’s southernmost state, Chiapas, told EFE that they had no interest in this offer.

That annual Easter week march of migrants near Mexico’s southern border—not exactly a “caravan,” but an organized protest to urge the Mexican government to allow them to keep moving northward—has walked about 20 miles through Chiapas, the country’s southernmost state. By March 26, its numbers had reportedly dwindled to about half of the approximately 3,000 participants with which it began.

Customs and Border Protection (CBP) provided updated data late on March 22 about migration through February at the U.S.-Mexico border. (Search this data at cbpdata.adamisacson.com .)

It revealed that

- Border Patrol apprehended 140,644 migrants in February, up 13 percent from January but still the 7th-fewest apprehensions of the Biden administration’s 37 full months .

- 49,278 migrants came to ports of entry, 42,100 of them (1,452 per day) with CBP One appointments . This is similar to every month since July 2023, as CBP officers tightly control the flow at ports of entry.

- Combining Border Patrol and port-of-entry encounters, CBP encountered 189,922 migrants at the border in February, an 8 percent increase over January.

In late February, press reports indicated that the Biden administration was considering new executive actions at the border, like limits on access to asylum or a ban on crossings between ports of entry. (See WOLA’s February 23 Border Update .) But then nothing happened: Politico reported on March 25 that the White House has stood down “in part, [due] to the downtick in migration numbers” so far this year. (Executive actions are not off the table, however. Axios reported that “President Biden is still considering harsh executive actions at the border before November’s election.”)

The top nationalities of migrants arriving at the border in February were:

- Mexico (33 percent of the month’s total; 28 percent during the first 5 months of fiscal 2024)

- Guatemala (13 percent; 11 percent during 2024)

- Cuba (7 percent; 6 percent during 2024)

- Colombia (6 percent; 6 percent during 2024)

- Ecuador (6 percent; 5 percent during 2024)

- Haiti (6 percent; 4 percent during 2024)

The nationalities for which encounters increased the most were chiefly South American :

- Brazil (87 percent more than January)

- Peru (67 percent)

- Colombia (65 percent)

- Ecuador (50 percent)

- El Salvador (31 percent)

The nationalities for which encounters decreased the most were:

- Turkey (72 percent fewer than February)

- India (56 percent fewer)

- Venezuela (24 percent fewer—and 85 percent fewer than in December)

- Russia (15 percent fewer)

- Cuba (7 percent fewer)

The top nationalities crossing between ports of entry and ending up in Border Patrol custody were:

- Mexico (35 percent of the total; 28 percent during the first 5 months of fiscal 2024)

- Guatemala (17 percent; 14 percent during 2024)

- Ecuador (8 percent; 7 percent during 2024)

- Colombia (8 percent; 7 percent during 2024)

- Honduras (6 percent; 8 percent during 2024)

The top nationalities reporting to ports of entry were:

- Mexico (27 percent; 26 percent during the first 5 months of fiscal 2024)

- Cuba (26 percent; 24 percent during 2024)

- Haiti (23 percent; 16 percent during 2024)

- Venezuela (11 percent; 18 percent during 2024)

- Honduras (4 percent; 5 percent during 2024)

Of February’s encountered migrants, combining Border Patrol and ports of entry:

- 60 percent were single adults (55 percent during the first 5 months of fiscal 2024), principally from Mexico, Guatemala, Cuba, Haiti, Ecuador, and Colombia

- 34 percent were members of family units (40 percent), principally from Mexico, Guatemala, Colombia, Honduras, Ecuador, and Cuba

- 5 percent were unaccompanied children (5 percent), principally from Guatemala, Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador, and Haiti

Border-zone seizures of fentanyl totaled 1,186 pounds in February, the fewest fentanyl seizures at the border in any month since June 2022. After five months, fiscal year 2024 fentanyl seizures total 8,021 pounds, 27 percent fewer than the same point in fiscal year 2023. This is the first time that fentanyl seizures have declined since the drug began to appear in the mid-2010s. Ports of entry account for 85 percent of this year’s fentanyl seizures. (See WOLA’s March 8 Border Update for a more thorough exploration of drug seizure data through January.)

Border Patrol divides the U.S.-Mexico border into nine geographic sectors. Between March 2013 and June 2023, the sectors with the largest number of arriving migrants were consistently in Texas. That changed in July of last year, shortly after the end of the Title 42 policy.

Since then Tucson, Arizona, has been the Border Patrol’s busiest sector . The principal nationalities arriving there so far in fiscal 2024 have been Mexico, Guatemala, “Other Countries,” Ecuador, India, and Colombia.

As of January, San Diego, California has been the number-two sector. The principal nationalities arriving there in fiscal 2024 have been “Other Countries,” Colombia, China, Mexico, Brazil, and Ecuador. (The prominence of “Other Countries” points to a need for CBP to add more detail to its public dataset.)

Weekly data from the Twitter accounts of Border Patrol’s sector chiefs indicate that while Tucson is experiencing decreases in migration this year, San Diego has remained largely steady.

The New York Times reported on the movement of migration away from the Texas border. Though the picture is complex, it concluded, the Texas state government’s high-profile crackdown on migration is a factor. Gov. Greg Abbott (R), a pro-Trump critic of the Biden administration’s border and migration policies, has been claiming credit for the geographic shift.

In less than three years, under a framework called “Operation Lone Star,” Texas state law enforcement has carried out the following measures using state funds. Most of these face challenges in federal and state courts.

- arrested and jailed 13,000 migrants, mainly for misdemeanor trespassing

- placed 107,800 migrants released from CBP custody on buses bound for six Democratic Party-governed cities

- deployed thousands of police and national guardsmen to the border

- built dozens of miles of fencing, while placing sharp concertina wire along the Rio Grande to block asylum seekers from turning themselves in to Border Patrol

- placed a “wall of buoys” in the middle of the Rio Grande in Eagle Pass

- sought to forbid Border Patrol agents from cutting the concertina wire, and denied agents’ access to the riverfront park in Eagle Pass

- pursued legal actions against El Paso’s four-decade-old Annunciation House migrant shelter

In December, Abbott secured passage of S.B. 4, a law that would empower Texas police and guardsmen to arrest people anywhere in the state on suspicion of having crossed the border improperly. If found guilty, defendants would have the choice of prison or deportation into Mexico.

Early in the morning of March 27, a federal Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals panel decided , by a two-to-one margin, to maintain a stay on S.B. 4, preventing it from going into effect while the Court considers legal challenges from the Biden administration Justice Department and from the ACLU and partner organizations.

The court will hear arguments on S.B. 4’s constitutionality on April 3. At stake is whether states can devise and implement their own independent immigration policies, and whether there is any validity to the claims of politicians, like Abbott, that asylum seekers and other migrants meet the constitutional definition of an “invasion.”

Mexico’s government filed an amicus curiae brief in federal court in support of the ongoing challenge to S.B. 4. Mexican Foreign Minister Alicia Bárcena told the Washington Post that her government would place “increased vigilance and controls” along the Texas border to prevent Texas state authorities from carrying out their own deportations without Mexico’s permission.

Very high levels of migration into Texas through December appeared to indicate that Operation Lone Star was having no deterrent effect. It is possible, though, that the more recent shift to western states could reflect migrants and smugglers entering a “wait and see mode” amid uncertainty over S.B. 4., a law that has been “on again, off again” as courts have lifted and reimposed stays in recent weeks.

February data, and an El Paso municipal government “ dashboard ,” do show increases in migration in four out of five Texas sectors , so the lull may be fleeting.

Across from El Paso In Ciudad Juárez , the Casa del Migrante, one of the city’s principal migrant shelters, “has been filling up in recent days as families and single adults looking for an opportunity to seek asylum in the United States are again arriving in Juarez in large numbers,” according to Border Report . Rev. Francisco Bueno Guillen, the shelter’s director, said it “went from being 20 percent full a couple of weeks ago to 75 percent capacity as of Monday.” The city’s municipal shelter is also three-quarters full.

In El Paso on March 21, a group of migrants on the U.S. bank of the Rio Grande pushed their way past Texas state National Guard personnel blocking access to the border wall, where they hoped to turn themselves in to federal Border Patrol agents. Video showed a chaotic scene.

A Texas law enforcement spokesman told the New York Times that the increase in migration to Border Patrol’s El Paso sector reflects more migrants crossing into New Mexico, which is part of that sector—not Texas. There is no way to verify that with available data.

Guatemala’s reformist new president, Bernardo Arévalo, visited the White House on March 25, where he met separately with President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris . Migration—of Guatemalans, and of other nations’ citizens transiting Guatemala—was a central topic in both of Arévalo’s conversations.

This is the first presidential visit for Arévalo, who took office on January 14. He and Vice President Harris reportedly discussed “providing lawful pathways to migrants, increasing cooperation on border enforcement, and…U.S. support for Guatemala’s migration management efforts.” A White House release stated that the Biden administration plans to provide Guatemala with an additional $170 million in security and development assistance , pending congressional notification.

Vice President Harris touted the administration’s “Root Causes Strategy,” which she claimed has created 70,000 new jobs, helped up to 63,000 farmers, supported 3 million students’ education, and trained more than 18,000 police officers and 27,000 judicial operators in all of Central America.

The leaders announced no changes to the U.S.-backed “Safe Mobility Office ” (SMO) in Guatemala that links some would-be migrants to legal pathways. The prior administration of President Alejandro Giammattei (whose U.S. visa has since been revoked amid corruption allegations) had reduced the SMO’s scope to serve only citizens of Guatemala. On a visit to Guatemala the week before, Mayorkas noted that the Guatemala SMO has “already helped more than 1,500 Guatemalans safely and lawfully enter the United States” via existing programs, principally refugee admissions.

The head of Guatemala’s migration agency, who worked in the government that left power in January, resigned on March 26. The reason for Stuard Rodríguez’s departure is not known. “Rodriguez made several reports during his administration of the increase of migrant expulsions, especially of Cubans and Venezuelans,” noted the Guatemalan daily Prensa Libre .

In 2023, under the Giammattei administration, Guatemalan authorities reported pushing back into Honduras more than 23,000 migrants , more than 70 percent of them Venezuelan. As of February 13, Guatemala’s 2024 expulsions count stood at 1,754.

So far in 2024, the U.S. and Mexican governments have deported 20,018 citizens of Guatemala back to their country by air, more than 5,000 above the total at the same time in 2023. The United States has returned 18,437 people on 154 flights, while Mexico has returned 1,632 on 15 flights.

Asked during his visit to Washington whether he believes that border walls work, Arévalo told CBS News , “I think that history shows they don’t. What we need to look for is integrated solutions to a problem that is far more complex than just putting a wall to try to contain.”

- The six construction workers presumed dead in the collapse of Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge were people who had migrated from Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. CASA of Maryland is collecting donations to support their families .

- 481 organizations (including WOLA) sent a letter to President Joe Biden asking him to extend Temporary Protected Status for Haitian migrants in the United States, to halt deportation flights and maritime returns to Haiti, and to increase the monthly cap on access to humanitarian parole for people still in the country, where governance is near collapse.

- At the London Review of Books , Pooja Bhatia combined a narrative of Haiti’s deteriorating security situation with an account of the challenges that Haitian asylum seekers face at the U.S.-Mexico border. Bhatia reported from the dangerous border in Tamaulipas, Mexico, and highlighted the role of humanitarian workers and service providers, including staff of the Haitian Bridge Alliance, the principal author of the above-cited letter.

- NBC News highlighted the dilemma of migrant women who were raped by criminals in Mexico while en route to the United States, and now find themselves in states like Texas where, following the 2022 Supreme Court Dobbs decision, it is illegal to obtain an abortion. Often, the rapes occur while migrants are stranded—usually for months—in Mexican border cities as they await CBP One appointments.

- Despite a crushing backlog of cases, the number of U.S. immigration judges declined in the first quarter of fiscal 2024, from 734 to 725. That means “each judge has 3,836 cases on average,” pointed out Kathleen Bush-Joseph of the Migration Policy Institute. (That number is greater if one uses TRAC Immigration’s higher estimate of the immigration court backlog.)

- The International Organization for Migration’s (IOM) Missing Migrants Project now has 10 years of data about deaths of migrants: 63,285 known cases worldwide between 2014 and 2023, including a high of 8,542 in 2023. In its 10-year report , IOM counted more deaths in the Mediterranean (28,854 deaths), Africa (14,385), and Asia (9,956) than in the Americas (8,984).

- CBP released body-worn camera footage of the February 17 death, apparently by suicide, of a man in a holding cell at a Laredo, Texas checkpoint. The footage does not show the exact circumstances of how the man died because “the video recording system at the Border Patrol checkpoint was not fully functioning at the time of the incident.”

- In Tucson, Arizona, local authorities now believe that federal funds—made possible by Congress passing a budget over the weekend—will arrive in time to prevent the closure of shelters that receive migrants released from CBP custody. The prospect of “street releases” in Tucson and other Arizona border towns is now unlikely.

- Colleen Putzel-Kavanaugh and Muzaffar Chishti of the Migration Policy Institute explained that many of today’s proposals to restrict asylum access and otherwise crack down on migration will not work because the U.S. government can no longer “go it alone.” Reasons include the diversity of countries migrants are coming from and the policies of other governments, such as varying visa requirements, refusals to accept repatriations, and the Mexican government’s unwillingness to receive expelled migrants from third countries.

- At Lawfare , Ilya Somin of the Cato Institute dismantled an argument that has become increasingly mainstream among Republican politicians: that asylum seekers and other migrants crossing the border constitute an “invasion” and that states have a constitutional right to confront them with their own security forces. Somin warns that the “invasion” idea, if upheld, could allow border states “to initiate war anytime they want,” and permit the federal government to suspend habeas corpus rights.

- Conservative politicians and media outlets are going after the non-profit shelters that receive migrants released from CBP custody in U.S. border cities, along with other humanitarian groups, noted Miriam Davidson at The Progressive . Tucson’s Casa Alitas and El Paso’s Annunciation House have been subject to aggressive misinformation and legal attacks so far this year.

- “I think the migrants that we encounter, that are turning themselves in, yes, I think they absolutely are, by and large, good people,” Border Patrol Chief Jason Owens told CBS News’s Face the Nation . But “what’s keeping me up at night is the 140,000 known ‘got-aways’” so far this fiscal year.

- At the New York Review of Books , Caroline Tracey documented an abandoned, unpopular plan to construct a massive Border Patrol checkpoint on I-19, the highway between Tucson and the border at Nogales, Arizona. The case highlighted the tension between security concerns and economic and human rights considerations.

- As Mexican farmworkers migrate to the United States, often on temporary work visas, Mexico is facing its own farm labor shortages and is considering setting up its own guest-worker program for citizens of countries to Mexico’s south, the Washington Post reported .

Related Content

Weekly u.s.-mexico border update: migrant deaths, 2024 budget, s.b. 4, weekly u.s.-mexico border update: darién gap, 2025 budget, texas litigation, state of the union, weekly u.s.-mexico border update: spring migration increase, darién gap, drug seizure data points to less fentanyl, weekly u.s.-mexico border update: biden and trump visits, “migrant crime” narratives, shelters in peril, weekly u.s.-mexico border update: possible executive action on asylum, texas crackdown, cbp accountability issues.

Skip to navigation

Skip to main content

Migrants and the Mexico-US Border

April 3, 2024

Between January 2021 and January 2024, CBP had more than six million encounters with unauthorized migrants on the Mexico-US border. Another two million migrants were detected entering the US but were not apprehended.

Many of the foreigners who entered the US illegally sought out Customs and Border Protection officers and applied for asylum. There is a backlog of three million immigration cases, including a million asylum cases, and space to detain fewer than 50,000 foreigners who are awaiting hearings before immigration judges. As a result, solo adult migrants who pass a credible fear test, meaning they have a 10 percent probability of being persecuted at home, are typically released into the US along with families with children and unaccompanied minors under 18. Immigration judges reject most asylum claims, but the backlog ensures that migrants can work in the US for several years while their children attend K-12 schools..

A record 250,000 foreigners were encountered by CBP officers just inside the Mexico-US border in December 2023. Most were not Mexicans.

Migrant encounters reached record levels in December 2023

Most migrants come to the US for more opportunities than they have in their home countries. Smugglers advertise and urge migrants to migrate to the US now in case Donald Trump is re-elected president and closes the border. A combination of US policies, immigration case backlogs, and the low US unemployment rate mean that most migrants who get into the US can find jobs.

Context. The US has four percent of the world’s 8.1 billion people but almost 20 percent of the world’s 280 million international migrants. A quarter of the almost 50 million foreign-born US residents are unauthorized.

The US welcomed Europeans to settle the country during its first century, and introduced qualitative restrictions in the 1880s, meaning there were no quotas on how many immigrants could come, but Chinese, communists and others were barred. The US added quantitative restrictions or numerical quotas in the 1920s and changed priorities in 1965 from national origins, favoring immigrants from Western Europe, to giving priority for immigrant visas to foreigners who have family members in the US. Further changes have made US immigration law second only to tax law in complexity.

The US is in the midst of the 4th wave of immigrants that began in 1965

Most of the 1.1 million legal immigrants admitted each year are from Latin America and Asia, and 70 percent are already in the US when they are “admitted,” meaning that receiving an immigration visa often means that a US resident changes from student, temporary worker, or another non-immigrant status to immigrant.

Immigrants differ from US-born residents in the best predictor of earnings, years of education. US-born adults, when ranked by their years of schooling, form a diamond shape, with a wide bulge in the middle for the 60 percent who are high-school graduates but lack college degrees. Immigrants have more of an hourglass shape: a higher share of Asian immigrants than US natives have advanced degrees, while a higher share of Latin American immigrants did not graduate from high school.

US immigration reforms often have unintended consequences. The 1965 reforms were not expected to change immigration patterns, but they did, as Latin American and Asian immigrants replaced Europeans. The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 legalized 2.7 million unauthorized foreigners, 85 percent Mexicans, and aimed to prevent more illegal immigration by imposing sanctions on employers who knowingly hired unauthorized workers. However, false documents proliferated and, because employers were not required to verify the documents presented by newly hired, sanctions were ineffective. One result: the number of unauthorized foreigners tripled from 3 million in 1990 to 9 million in 2000 rose further to 12 million in 2007.

Mexicans are almost half of the 12 million unauthorized foreigners in the US. As unauthorized Mexicans spread throughout the US in the 1990s and early 2000s, reactions varied. Alabama, Arizona, Georgia and other states enacted laws that required employers to use the internet-based E-Verify system to check new hires to discourage illegal migrants from coming to or staying in the state. California, New York and 17 other states issue driver’s licenses, allow unauthorized foreigners to pay in-state university fees, and provide health care to poor unauthorized foreigners.

Trump. President Donald Trump (2017-21) pledged to reduce illegal migration at the border, deport unauthorized foreigners from inside the US, and reduce refugee admissions, drawing protests and suits that blocked or slowed the implementation of some of Trump’s executive orders. Trump’s efforts to build a wall on the Mexico-US border, separate parents who entered illegally from their under-18 children (who can be detained only 20 days), and invoke a public health law (Title 42) to prevent migrant entries, sent a message that the US was not open to migrants and asylum seekers.

Trump promised to build a wall on the 2,000 mile Mexico-US border

Trump’s focus on illegal immigration made migration a more partisan issue. Instead of the bipartisan IRCA of 1986, Republicans under Trump argued that illegal immigration must be halted before dealing with unauthorized foreigners who had developed an equity stake in the US. Democrats became more admissionist, arguing for the legalization of unauthorized foreigners in the US and the abolition of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency that detects and removes unauthorized foreigners from the interior of the US (“abolish ICE”).

Under Trump, the US continued to admit over a million immigrants a year. However, Trump’s efforts to separate adults from their children in a bid to discourage asylum seeking and to speed up the processing of asylum applications were challenged in court and often not fully implemented.

Despite Trump’s promise to farmers that he would make it easier for them to employ guest workers, and the employment of H-2A and H-2B workers in Trump businesses, there were no significant changes to these seasonal guest worker programs during the Trump presidency. The H-2A program is not capped, and farm employers were certified to fill almost 400,000 seasonal jobs with guest workers in 2023. Nonfarm employers complained of too few H-2B visas to fill seasonal nonfarm jobs, prompting successful efforts to allow H-2B migrants who worked previously for an employer to not count against the 66,000 a year cap.

Biden. President Biden took office in 2021 and reversed many of Trump’s policies. Biden issued over 500 executive orders on migration that, inter alia, stopped construction of the border wall and ended workplace raids aimed at detecting unauthorized workers inside the US. Biden tackled the root causes of migration by promising aid to Central American countries and more opportunities to enter the US legally to work or apply for asylum.

Biden reversed many Trump migration policies in 2021

Biden Immigration Bill:

- Allow Central American children to apply for refugee/asylum status from

- Hiring more immigration judges to handle asylum cases

- Offering "humane alternatives" to immigrant detention

- Chaning the term "alien" to "noncitizen" in immigration laws

- An expedited path to citizenship for DACA< TPS recipients

After taking office, Biden halted deportations for 100 days and ordered DHS to prioritize the deportation of foreigners convicted of US crimes and those who arrived in the US recently.

Deportations of foreigners from inside the US have been falling

Biden’s reversal of Trump policies, the end of Title 42 in May 2023 (which allowed foreigners to be returned to Mexico without an opportunity to apply for asylum), and the booming US economy sent a signal that the US border was open, leading to the largest unauthorized migration flows in US history. Mexicans are the largest nationality apprehended between US ports of entry on the Mexican border, followed by Central and South Americans.

The share of Mexicans among the unauthorized has fallen

Most non-Mexicans apply for asylum, knowing that they will be able to remain legally in the US for several years until there is a final resolution of their cases.

There are 3 million cases in immigration courts, including a million asylum applicants

The share of applicants who were granted asylum rose toward 50% under Biden

The US has special rules for children under 18 who are encountered, usually releasing them to parents or relatives in the US.

There were 20,000 unaccompanied children a month in 2021.

Most unauthorized foreigners are detected by CBP officers just inside the Mexico-US border rather than by ICE officers who enforce immigration laws in the interior of the US. Texas is a border state that tried to prevent the entry of unauthorized migrants by placing shipping containers covered with barbed wire on the banks of the Rio Grande River to make it harder for migrants to enter the US. The Biden Administration sued to obtain a court order to force Texas to remove these barriers.

Texas tried to deter migrants with shipping containers topped by barbed wire

Perspective. The stock of unauthorized foreigners in the US peaked at 12 million in 2007 and is 11 to 12 million in 2024. Additional foreigners, including those with a Temporary Protected Status and asylum applicants, are living and working legally in the US and could become unauthorized if they are not granted asylum or TPS is ended and they do not depart. The rising number of legal and unauthorized foreigners pushed net immigration above a million in 2023.

The number of illegal immigrants peaked at 12 million in 2007

Net immigration to the US was over a million in 2023

House Republicans impeached DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas in February 2024 on a 214-213 vote for “breach of trust” and “willful and systemic refusal to comply with the law” because DHS failed to prevent illegal entries. During Congressional hearings, Mayorkas was asked repeatedly if DHS had “operational control” of the border and, when he answered yes, was accused of lying to Congress.

The House impeached DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas in February 2024

Immigration promises to be a major issue in the 2024 presidential election. Senators James Lankford (R-OK), Kyrsten Sinema (I-AZ), and Chris Murphy (D-CT) negotiated a $118 billion, 370-page bill in February 2024 that included provisions to reduce illegal entries over the Mexico-US border by restricting the number of asylum applicants. The Senate bill, opposed by ex-President Trump and declared dead on arrival in the House, failed to advance in the Senate.

House Republicans approved the Secure the Border Act of 2023 (HR 2) in May 2023 on a 219-213 vote. HR 2 would build 200 miles of wall a year on the Mexico-US border, require CBP to prevent all unlawful entries into the US, and end the use of the CBP One app that allows foreigners to make appointments to apply for asylum at ports of entry.

Under HR 2, asylum applicants would have to apply in the first safe country they transit en route to the US. Once in the US, they would have to convince an asylum officer they are “more likely than not” to qualify for refugee status in the US in order to enter and wait for a hearing before an immigration judge. HR 2 would require asylum applicants to be detained or returned to Mexico until a decision on their application is made.

Polls suggest that managing migration will be a major issue in 2024 elections. Some 60 to 70 percent of respondents agree that immigration and border security are moving in the wrong direction, and that Republicans are better than Democrats at managing migration.

Most respondents disapprove of Biden’s handing of immigration and border issues

President Biden is trying to navigate between moderate Democrats who want to do more to reduce illegal migration and Democratic admissionists who believe that the US should be more open to legal immigrants, foreign visitors, and those seeking refuge and opportunity. Ex-President Trump and many Republicans argue that Trump should “finish the job” begun in his first term by completing a wall on the Mexico-US border, reducing refugee admissions, and deporting unauthorized foreigners inside the US.

Immigration was the top concern of Americans in the February 2024 Gallup poll

Subscribe via email.

Click here to subscribe to Rural Migration News via email .

I study migrants traveling through Mexico to the US, and saw how they follow news of dangers – but are not deterred

Postdoctoral Fellow, Cornell University

Disclosure statement

Angel Alfonso Escamilla García does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

The world awoke one morning in late March 2023 to the news that at least 38 Central and South American migrants had died in a fire in a migrant detention center in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico.

A widely circulated video from the closed-circuit cameras inside the detention center showed the building burning, with migrants trapped inside trying to break the metal bars of their cells – and detention center officers allegedly leaving them there.

The Mexican government has said the migrants themselves started the fire after learning they would be deported from Mexico – which is increasingly a destination for migrants and asylum seekers – back to their home countries.

The video spread quickly across social media, and many Mexican migrant advocacy groups and activists decried the event.

Another group also paid close attention to this tragedy – migrants who are in transit through Mexico.

As a sociologist , I have studied the impacts of violence against Central American migrants in Mexico for nearly a decade. I have considered questions like how migrants who are on their way to the U.S. react to news of violence against other migrants, and whether such news alters their plans.

My research has shown that migrants pay close attention to any information that can give them clues about the dangers that lie between them and the U.S.

Migrants have shared with me that they highly value information about any dangers ahead as they move north, whether it relates to criminal groups or U.S. immigration policy changes. Migrants use this knowledge to implement a variety of strategies to avoid, or at least prepare for, any suffering – and it can lead them to take different routes to the U.S. border.

Understanding migrants in Mexico

Hundreds of thousands of migrants from around the world transit through Mexico every year on their way to the U.S.-Mexico border. In April 2023 alone, the U.S. detained more than 211,000 migrants along that border. That statistic coincides with an overall rise in global migration and rise in migrants trying to reach the U.S.

The majority of migrants crossing the U.S. border come from Latin American countries other than Mexico , including Central American countries, but also Peru, Colombia, Venezuela and Cuba.

Most of these migrants are single adults , though a number of them are also families and children. People migrate through Mexico for many reasons, including political instability, lack of work opportunities and violence in their own countries.

My interviews with migrants moving through Mexico show that they tend to widely circulate tragic news, such as news of the June 2022 news of migrants found dead locked in a tractor trailer in San Antonio. Videos and photos of this and other tragic instances, like the Ciudad Juárez fire, provide real, vivid images of what can happen if migrants decide to pursue the same pathway.

And for these migrants, the images and news stories aren’t secondhand information that they can question or doubt – images can be interpreted as unchangeable truths.

How migrants get their news

Migrants don’t receive news from New York Times alerts or nightly news.

Their information-sharing largely occurs in an underground informal information exchange that circulates news and stories among migrants heading toward the U.S. through Mexico.

That information is shared, discussed, interpreted and commented on through social media platforms, chat groups and word of mouth. Within 24 hours of the Ciudad Juárez fire, every single social media outlet and migrant chat that I follow as part of my research, comprised of thousands of transit migrants moving throughout Mexico and Guatemala in real time, had posted and reposted the video and news of the incident.

Some comments and replies in social media and chat groups about the incident prayed for mercy and peace for the dead and their loved ones.

Others asked for a list of names of the dead, or about their places of origin, as people desperately sought to find out whether their family members and friends were among the dead and injured. Still others asked for tips and discussed ways to avoid suffering the same fate, such as asking about alternate routes to the border, or sharing ways to avoid ending up in Mexican migrant detention centers.

A shared response

Common among migrants’ reactions to the March 2023 fire was a deep sense of grief. Migrants recognized how close they are to those who lost their lives and expressed a sense of “that could have been me.”

And yet, in my field work, I have found that these horrific events do not deter migrants’ desire to reach the U.S. What they do is reset migrants’ expectations going forward.

Through my field work, I have heard migrants repeatedly tell stories about the dire conditions in detention centers in Mexico .

They report that these poor conditions – rotten food, fleas, lack of clothing or blankets for the cold weather – have triggered hunger strikes and protests.

Broader effects

Another of my main findings is that violent and tragic incidents tend to prompt migrants to avoid any interactions with police or any other officials, even under the guise of help or support.

For example, my research suggests that stories and images of violence like the Ciudad Juárez tragedy will generate a further lack of trust in the Mexican government. I believe that the incident will create certain expectations about the perils of spending time near the border. If they can, I think that migrants will likely avoid Ciudad Juárez and other areas where they feel they may be detained.

I believe the fire will also leave a symbolic scar on migrants in Mexico, who will collectively remember this event and construct their journeys around it.

- Social media

- Immigration

- Human rights

- Latin America

- Human rights violations

Communications and Events Officer

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Consequences of Migration to the United States for Short-term Changes in the Health of Mexican Immigrants

Noreen goldman.

Office of Population Research, Princeton University, Wallace Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA

Anne R. Pebley

California Center for Population Research, University of California Los Angeles, CA. 90095, USA

Mathew J. Creighton

Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Departament de Ciències Polítiques i Socials, Barcelona, Spain

Graciela M. Teruel

Universidad Iberoamericana, AC and CAMBS, México D.F., México

Luis N. Rubalcava

Centro de Análisis y Medición del Bienestar Social, AC and CIDE, México D.F., México

Chang Chung

Although many studies have attempted to examine the consequences of Mexico-U.S. migration for Mexican immigrants’ health, few have had adequate data to generate the appropriate comparisons. In this article, we use data from two waves of the Mexican Family Life Survey (MxFLS) to compare the health of current migrants from Mexico with those of earlier migrants and nonmigrants. Because the longitudinal data permit us to examine short-term changes in health status subsequent to the baseline survey for current migrants and for Mexican residents, as well as to control for the potential health selectivity of migrants, the results provide a clearer picture of the consequences of immigration for Mexican migrant health than have previous studies. Our findings demonstrate that current migrants are more likely to experience recent changes in health status—both improvements and declines—than either earlier migrants or nonmigrants. The net effect, however, is a decline in health for current migrants: compared with never migrants, the health of current migrants is much more likely to have declined in the year or two since migration and not significantly more likely to have improved. Thus, it appears that the migration process itself and/or the experiences of the immediate post-migration period detrimentally affect Mexican immigrants’ health.

Introduction

Large-scale Mexican-U.S. migration has changed social, economic, and cultural life on both sides of the border. Migration to the United States can offer increased earnings and savings accumulation ( Gathmann 2008 ). However, it can also be a difficult experience for migrants because of the risks and costs of border crossing; poorly paying, irregular, and hazardous jobs; crowded housing; lengthy family separation; discrimination; and a politically hostile climate ( Hovey 2000 ; Massey and Sanchez 2010 ; Ullmann et al. 2011 ).

What are the consequences of the immigrant experience for immigrants’ health? The literature suggests that Mexican immigrants are positively selected for good health and healthy behaviors (the “healthy migrant effect”) but that living in the United States may lead to deterioration in both health and healthy behaviors of migrants ( Ceballos and Palloni 2010 ; Kaestner et al. 2009 ; Oza-Frank et al. 2011 ; Riosmena and Dennis 2012 ). However, the evidence for both parts of this scenario is often contradictory and limited by available data. A study based on Mexican longitudinal data found only weak evidence of positive health selection for migrants ( Rubalcava et al. 2008 ). However, studies using binational cross-sectional data to compare Mexican immigrants in the United States with Mexican residents have argued more strongly in support of positive health selection ( Barquera et al. 2008 ; Crimmins et al. 2005 ).

Research on the effects of life in the United States on immigrant health is also problematic. Studies comparing immigrant duration cohorts cross-sectionally in the United States have generally suggested that immigrant health and health behaviors deteriorate with longer durations of residence ( Abraído-Lanza et al. 2005 ; Lara et al. 2005 ). In contrast, some studies indicate that health trajectories are not monotonically related to time spent in the United States ( Jasso et al. 2004 ; Teitler et al. 2012 ).

Many of the limitations characterizing previous research on immigrant health result from reliance on cross-sectional data. These studies did not have adequate information on premigration health, making it impossible to determine when health deterioration began. In addition, cross-sectional comparisons involve cohorts of immigrants with different characteristics that arrived in different time periods with distinct political and economic climates; comparisons are further biased by selective attrition of return migrants, who, on average, are less healthy than the stayers (i.e., the “salmon bias”; Riosmena et al. 2013 ). Moreover, cross-sectional studies cannot assess whether the observed health trajectories of immigrants differ from those of nonmigrants. Alternative strategies that compare U.S. emigrants who have returned to Mexico with those who remained in their home communities are also problematic because of potential health-selective return migration.

In this article, we use data from the two waves of the Mexican Family Life Survey (MxFLS) to explicitly examine short-term changes in health status for current migrants in the United States compared with return migrants and never migrants. Because the richness of data in the MxFLS permits extensive controls for the potential health selectivity of migrants, this article provides a significantly clearer picture of the consequences of immigration for Mexican migrant health than previous studies.

The literature suggests several reasons why immigrant health may deteriorate in the United States. The first is inadequate access to health care, particularly for undocumented migrants ( Nandi et al. 2008 ; Prentice et al. 2005 ; Vargas Bustamante et al. 2012 ). Having health insurance is a key predictor of access to health care, particularly for immigrants ( Siddiqi et al. 2009 ).

A second explanation is the detrimental effects of acculturation on health behaviors (i.e., poor diet, a sedentary lifestyle, and substance abuse) through exposure to U.S. society. In recent years, the acculturation literature has been strongly criticized ( Carter-Pokras et al. 2008 ; Creighton et al. 2012 ; Hunt et al. 2004 ; Viruell-Fuentes 2007 ; Zambrana and Carter-Pokras 2010 ) for failing to take socioeconomic status seriously and for its limited theoretical grounding in the immigrant integration literature. A more nuanced interpretation of the acculturation hypothesis, drawn from the literature on segmented assimilation, suggests that Mexican immigrants may adopt the less healthy behaviors of lower-income Americans because many involuntarily join this social class upon entering the United States ( Abraído-Lanza et al. 2006 ).

Other hypotheses focus on social inequality as causes of declines in migrant health ( Viruell-Fuentes et al. 2012 ). For example, the acculturative stress hypothesis suggests that because U.S. society views Mexican-origin immigrants as low status, immigrants face discrimination and chronic stress ( Finch and Vega 2003 ). In addition, Mexican immigrants may live and work under unhealthy conditions that expose them to infectious disease, environmental toxins, injury, and other health risks ( Acevedo-Garcia 2001 ; Kandel and Donato 2009 ; Orrenius and Zavodny 2009 ).

A related stressor is the increasingly hostile political climate for recent immigrants in the United States, including stronger border enforcement, restriction of access to welfare and Medicaid, and state anti-immigrant efforts ( Cornelius 2001 ; Massey and Sanchez 2010 ). Discrimination, family cultural conflict and lengthy separation, a hostile political climate, loss of social support, and, after the 2008 economic crisis, fewer jobs are all likely to be stressful experiences, especially for undocumented immigrants, and are likely to have a more immediate impact on immigrants’ mental and physical health than poor access to health care or acculturation mechanisms.

Despite these findings, it is possible that emigration to the United States improves Mexican migrants’ health. Residence in the United States has a consistently positive effect on the wealth of middle-aged and older Mexican return migrants ( Wong et al. 2007 ), and income and wealth are strongly associated with better health ( Marmot and Bell 2012 ). Mexican migrants, particularly documented ones, may also experience better working and housing conditions than they would have in Mexico. Previous studies have found that health care use and self-perceptions of health may improve with duration in the United States ( Hummer et al. 2004 ; Lara et al. 2005 ) and that some health outcomes are better for immigrants who have resided in the United States for several years ( Riosmena et al. 2013 ; Teitler et al. 2012 ).

In this article, we examine whether the health of Mexican immigrants deteriorates or improves after migration to the United States. We explicitly compare changes in health status of recent immigrants with those of previous immigrants and with individuals who remained in Mexico. Because these three groups are likely to differ in initial health status (e.g., because of the healthy migrant effect and salmon bias), a critical part of this analysis is the introduction of extensive controls for baseline health status.

The Mexican Family Life Survey (MxFLS) has several advantages for this analysis: it interviews respondents at closely spaced waves that permit assessment of short-term changes in health for migrants to the United States and individuals who remain in or return to Mexico; it collects objective and subjective health assessments that provide controls for potential health selectivity of migrants; and it obtains detailed migration histories that allow us to distinguish among recent, earlier, and never migrants. The baseline survey in 2002 (MxFLS-1) interviewed all adult members residing in more than 8,440 households in 147 localities of Mexico ( Rubalcava and Teruel 2006 ). Respondents in the baseline survey were reinterviewed in 2005–2006 (MxFLS-2) and 2009–2012 (MxFLS-3). MxFLS followed individuals who left their household of origin, irrespective of destination, including movers to the United States: of those sampled in MxFLS-1, more than 90% were located and interviewed again in MxFLS-2 ( Rubalcava et al. 2008 ). This analysis is based on MxFLS-1 and MxFLS-2; MxFLS-3 is not yet available.

The sample includes respondents who are 20 years and older at baseline. Of the 19,132 age-appropriate respondents, one could not be matched to a municipality and was excluded. An additional 4,874 respondents did not report one or both of the health outcomes at follow-up. After exclusion of these respondents, the analytic sample comprises 14,257 adults.

In exploratory analyses, we estimated a logistic model of the probability that a respondent was missing either of the two health outcomes. The results indicate that individuals with no previous migration history, those with more education, men, and individuals in their 20s were more likely to be missing outcomes than others. However, with these variables in the model, there were no significant differences by self-reported health status at baseline.

Outcome Variables: Self-reported Health and Change in Health

Despite the frequent use of self-reports of overall health to compare the well-being of various immigrant and native-born groups (e.g., Finch and Vega 2003 ), comparisons may be biased by differences in choice of reference group, degree of acculturation, and language of interview ( Bzostek et al. 2007 ). Because this analysis examines changes in reported health for a given individual, such biases are likely to be substantially reduced. We consider two outcomes—self-rated health (SRH) and perceived change in health—each with five possible responses: “much better,” “better,” “the same,” “worse,” and “much worse.” The SRH question in MxFLS-2 for both Mexican residents and immigrants in the United States, is as follows:

If you compare yourself with people of the same age and sex, would you say that your health is (…)?

With controls for SRH at baseline, an analysis of SRH at follow-up implicitly examines change in the respondent’s health between interviews.

The second outcome is a direct assessment of change, based on different questions for respondents in the United States and in Mexico. Respondents in Mexico were asked:

Comparing your health to a year ago, would you say your health now is (…)?

Respondents interviewed in the United States were instead asked:

Comparing your health to just before you came to the United States, would you say your health now is (…)?

Calculations indicate that the average time since migration to the United States for current migrants is 1.6 years—only slightly longer than the explicit period of 1 year used in the Mexico interviews.

Because few respondents reported the extreme categories of “much better” or “much worse,” the five response categories were collapsed into three: “much better” and “better” were combined into a single category, as were “much worse” and “worse;” “same” health is the reference category.

Migrant Status

We categorize respondents as “current,” “return,” and “never” migrants. Current migrants migrated after the baseline survey and were interviewed in the United States in MxFLS-2. Return migrants were interviewed in Mexico at Wave 2 but had previous migration experience to the United States; they include long-term and temporary migrants as well as those who migrated to the United States between survey waves but returned to Mexico before the second interview. Never migrants reported no international migration experience by Wave 2.

Control Variables

To account for potential differences in the health status of migrants, return migrants, and nonmigrants at baseline that are not captured by SRH, we include four health variables in addition to SRH, all measured at Wave 1. Obesity, anemia, and hypertension are derived from assessments conducted in the home by a trained health worker. Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥30 based on height and weight measurements ( WHO 2000 ). Individuals are classified as anemic for the following hemoglobin (Hb) levels: Hb<130 g/L for males or Hb<120 g/L for females ( WHO 2000 ). Individuals with elevated systolic (mmHg≥140) and/or diastolic (mmHg≥90) blood pressure are considered hypertensive ( WHO 2000 ). The final health measure reflects whether the respondent had been hospitalized in the past year.

Two measures of socioeconomic status provide additional controls for potential selectivity of migrants: (1) years of schooling, and (2) log per capita household expenditure. The latter measure has been used to assess household economic well-being in a broad range of contexts, including Mexico ( Contreras 2003 ; Rubalcava et al. 2009 ; Xu et al. 2009 ). All models also control for sex and age (linear and quadratic terms).

Municipal Controls

Because the literature suggests that migration decisions depend on place of origin ( Rubalcava et al. 2008 ) and migration flows at the municipality level are likely to be related to unobserved characteristics (e.g., human capital) of residents, we include three variables at the municipality level. A municipality was coded as rural if there were fewer than 2,500 residents ( INEGI 2003 ). We also include two measures based on the 2000 Mexican Census: (1) a marginalization index derived from a factor analysis of municipal-level measures of education, housing, income, and schooling ( Luis-Ávila et al. 2001 ); and (2) a measure of migration intensity based on the number of return migrants, current migrants, and amount of remittances received by households ( Tuirán et al. 2002 ). Both measures are categorized as “low,” “medium,” and “high.”

As described earlier, we classify both health outcome variables (self-rated health at Wave 2 relative to someone of the same age and sex and perceived health change over the year prior to Wave 2) as better, same, or worse health. For each of the two health outcomes, we fit multinomial regression models, with “same” health as the reference category, to estimate relative risk ratios (RRRs) for worse relative to same health and RRRs for better relative to same health. We estimate a set of three models that sequentially includes (1) migrant status, baseline SRH, age and sex; (2) objective health measures; (3) socioeconomic status and municipal-level characteristics. The estimate of primary interest pertains to current migrants: that is, is health at follow-up or perceived change in health of current migrants better, worse, or the same as that of never or return migrants?

We use multiple imputation to estimate a response for explanatory variables with missing values (see Table 1 for the frequency of missing data). We create five imputed data sets. The imputation models include all covariates with complete information as well as a variable denoting household size (to improve overall model fit). The estimated RRRs in the results section are derived from average values of the coefficients across the five imputed data sets.

Description of the outcome and explanatory variables in the analytic sample

The sample is clustered at two levels: 14,257 adults are drawn from 7,200 households and 136 municipalities. To account for the dependence of observations, we use robust standard errors clustered at the household level to calculate variances under multiple imputation. The estimates are computed in Stata 12 using the mlogit command ( StataCorp 2011 ).

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1 . At each wave, about 60 % of respondents evaluate their overall health the same as someone of the same age and sex, and only about 8 % rate their health as worse. Almost twice as many respondents note an improvement as compared with a deterioration in health over the period. About 5 % of the respondents are current or return migrants.

The relative risk ratios (RRRs, or exponentiated coefficients) in Table 2 pertain to self-rated health at follow-up. Based on Model 3, the estimated RRR for current migrants is 1.7 ( p < .05) for worse compared with the same health and 1.3 ( p < .05) for better compared with the same health (relative to a never migrant). In other words, current migrants in the United States are less likely than never migrants to rate themselves as having the same health status as someone of their age and sex: they are more apt to rate their health both worse and better—but especially worse than their peers—at the second interview. The estimates for return migrants are not significantly different from those for never migrants. Estimates for the control variables generally conform to expectation.

Relative risk ratios (RRRs) and t statistics from multinomial logistic model of self-rated health status (SRH) relative to same age and sex at MxFLS-2

Notes: Based on five multiple imputations of missing values. Standard errors are adjusted for clustering at the household level.

Because RRRs are difficult to interpret, in upcoming Table 4 , we present predicted probabilities of worse, same, or better health at follow-up by migrant status. Each estimate was determined by setting all explanatory variables except migrant status at their observed values for each individual, setting migrant status to the same value for all individuals (never, return, or current migrant) and calculating the mean prediction from the model. The first panel, which shows predictions based on Model 3 in Table 2 , underscores the results noted earlier: at follow-up, current migrants are considerably more likely (by nearly 50 %) than never migrants to rate their health as worse than someone of the same age and sex and only slightly more likely (by about 13 %) to rate their health as better.

Average predicted probabilities of self-rated health status at Wave 2 a and perceived change in health status b by migrant status

Notes: Predicted probabilities were determined by setting all explanatory variables except migrant status at their observed values for each individual, setting migrant status to the same value for all individuals (never, return, current migrants), and calculating the mean prediction from the model.

The RRRs in Table 3 are based on respondents’ assessments of the change in their health status. Consistent with the previous estimates, the RRRs for deteriorating health are large and significant for current migrants (1.9 in Model 3). In contrast, the RRRs for improving health are not significantly different from one for current migrants. As with SRH, the RRRs for return migrants are not significantly different from one for either deteriorating or improving health. The predicted probabilities in the second panel of Table 4 indicate that the health of current migrants is about 60 % more likely than that of never migrants to have worsened in the recent past and only very slightly (and insignificantly) more likely to have improved.

Relative Risk Ratios (RRRs) and t-statistics from Multinomial Model of Perceived Change in Health Status Relative to Previous Year or Prior to Migration

Note: Based on five multiple imputations of missing values. Standard errors are adjusted for clustering at the household level.

The central question of this analysis has been whether migrants from Mexico to the United States experience changes in their health after they move. This simple question has not been adequately answered by prior research because of the dearth of appropriate data. However, through data collection efforts in Mexico and the United States at the second wave, and extensive baseline information on variables potentially related to the health selectivity of migrants, the MxFLS permits us to address this issue in a methodologically appropriate way.