ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, 5 problem-solving activities for the classroom.

Problem-solving skills are necessary in all areas of life, and classroom problem solving activities can be a great way to get students prepped and ready to solve real problems in real life scenarios. Whether in school, work or in their social relationships, the ability to critically analyze a problem, map out all its elements and then prepare a workable solution is one of the most valuable skills one can acquire in life.

Educating your students about problem solving skills from an early age in school can be facilitated through classroom problem solving activities. Such endeavors encourage cognitive as well as social development, and can equip students with the tools they’ll need to address and solve problems throughout the rest of their lives. Here are five classroom problem solving activities your students are sure to benefit from as well as enjoy doing:

1. Brainstorm bonanza

Having your students create lists related to whatever you are currently studying can be a great way to help them to enrich their understanding of a topic while learning to problem-solve. For example, if you are studying a historical, current or fictional event that did not turn out favorably, have your students brainstorm ways that the protagonist or participants could have created a different, more positive outcome. They can brainstorm on paper individually or on a chalkboard or white board in front of the class.

2. Problem-solving as a group

Have your students create and decorate a medium-sized box with a slot in the top. Label the box “The Problem-Solving Box.” Invite students to anonymously write down and submit any problem or issue they might be having at school or at home, ones that they can’t seem to figure out on their own. Once or twice a week, have a student draw one of the items from the box and read it aloud. Then have the class as a group figure out the ideal way the student can address the issue and hopefully solve it.

3. Clue me in

This fun detective game encourages problem-solving, critical thinking and cognitive development. Collect a number of items that are associated with a specific profession, social trend, place, public figure, historical event, animal, etc. Assemble actual items (or pictures of items) that are commonly associated with the target answer. Place them all in a bag (five-10 clues should be sufficient.) Then have a student reach into the bag and one by one pull out clues. Choose a minimum number of clues they must draw out before making their first guess (two- three). After this, the student must venture a guess after each clue pulled until they guess correctly. See how quickly the student is able to solve the riddle.

4. Survivor scenarios

Create a pretend scenario for students that requires them to think creatively to make it through. An example might be getting stranded on an island, knowing that help will not arrive for three days. The group has a limited amount of food and water and must create shelter from items around the island. Encourage working together as a group and hearing out every child that has an idea about how to make it through the three days as safely and comfortably as possible.

5. Moral dilemma

Create a number of possible moral dilemmas your students might encounter in life, write them down, and place each item folded up in a bowl or bag. Some of the items might include things like, “I saw a good friend of mine shoplifting. What should I do?” or “The cashier gave me an extra $1.50 in change after I bought candy at the store. What should I do?” Have each student draw an item from the bag one by one, read it aloud, then tell the class their answer on the spot as to how they would handle the situation.

Classroom problem solving activities need not be dull and routine. Ideally, the problem solving activities you give your students will engage their senses and be genuinely fun to do. The activities and lessons learned will leave an impression on each child, increasing the likelihood that they will take the lesson forward into their everyday lives.

You may also like to read

- Classroom Activities for Introverted Students

- Activities for Teaching Tolerance in the Classroom

- 5 Problem-Solving Activities for Elementary Classrooms

- 10 Ways to Motivate Students Outside the Classroom

- Motivating Introverted Students to Excel in the Classroom

- How to Engage Gifted and Talented Students in the Classroom

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

Tagged as: Assessment Tools , Engaging Activities

- Online & Campus Doctorate (EdD) in Higher Edu...

- Degrees and Certificates for Teachers & Educa...

- Programming Teacher: Job Description and Sala...

Teaching problem solving: Let students get ‘stuck’ and ‘unstuck’

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, kate mills and km kate mills literacy interventionist - red bank primary school helyn kim helyn kim former brookings expert @helyn_kim.

October 31, 2017

This is the second in a six-part blog series on teaching 21st century skills , including problem solving , metacognition , critical thinking , and collaboration , in classrooms.

In the real world, students encounter problems that are complex, not well defined, and lack a clear solution and approach. They need to be able to identify and apply different strategies to solve these problems. However, problem solving skills do not necessarily develop naturally; they need to be explicitly taught in a way that can be transferred across multiple settings and contexts.

Here’s what Kate Mills, who taught 4 th grade for 10 years at Knollwood School in New Jersey and is now a Literacy Interventionist at Red Bank Primary School, has to say about creating a classroom culture of problem solvers:

Helping my students grow to be people who will be successful outside of the classroom is equally as important as teaching the curriculum. From the first day of school, I intentionally choose language and activities that help to create a classroom culture of problem solvers. I want to produce students who are able to think about achieving a particular goal and manage their mental processes . This is known as metacognition , and research shows that metacognitive skills help students become better problem solvers.

I begin by “normalizing trouble” in the classroom. Peter H. Johnston teaches the importance of normalizing struggle , of naming it, acknowledging it, and calling it what it is: a sign that we’re growing. The goal is for the students to accept challenge and failure as a chance to grow and do better.

I look for every chance to share problems and highlight how the students— not the teachers— worked through those problems. There is, of course, coaching along the way. For example, a science class that is arguing over whose turn it is to build a vehicle will most likely need a teacher to help them find a way to the balance the work in an equitable way. Afterwards, I make it a point to turn it back to the class and say, “Do you see how you …” By naming what it is they did to solve the problem , students can be more independent and productive as they apply and adapt their thinking when engaging in future complex tasks.

After a few weeks, most of the class understands that the teachers aren’t there to solve problems for the students, but to support them in solving the problems themselves. With that important part of our classroom culture established, we can move to focusing on the strategies that students might need.

Here’s one way I do this in the classroom:

I show the broken escalator video to the class. Since my students are fourth graders, they think it’s hilarious and immediately start exclaiming, “Just get off! Walk!”

When the video is over, I say, “Many of us, probably all of us, are like the man in the video yelling for help when we get stuck. When we get stuck, we stop and immediately say ‘Help!’ instead of embracing the challenge and trying new ways to work through it.” I often introduce this lesson during math class, but it can apply to any area of our lives, and I can refer to the experience and conversation we had during any part of our day.

Research shows that just because students know the strategies does not mean they will engage in the appropriate strategies. Therefore, I try to provide opportunities where students can explicitly practice learning how, when, and why to use which strategies effectively so that they can become self-directed learners.

For example, I give students a math problem that will make many of them feel “stuck”. I will say, “Your job is to get yourselves stuck—or to allow yourselves to get stuck on this problem—and then work through it, being mindful of how you’re getting yourselves unstuck.” As students work, I check-in to help them name their process: “How did you get yourself unstuck?” or “What was your first step? What are you doing now? What might you try next?” As students talk about their process, I’ll add to a list of strategies that students are using and, if they are struggling, help students name a specific process. For instance, if a student says he wrote the information from the math problem down and points to a chart, I will say: “Oh that’s interesting. You pulled the important information from the problem out and organized it into a chart.” In this way, I am giving him the language to match what he did, so that he now has a strategy he could use in other times of struggle.

The charts grow with us over time and are something that we refer to when students are stuck or struggling. They become a resource for students and a way for them to talk about their process when they are reflecting on and monitoring what did or did not work.

For me, as a teacher, it is important that I create a classroom environment in which students are problem solvers. This helps tie struggles to strategies so that the students will not only see value in working harder but in working smarter by trying new and different strategies and revising their process. In doing so, they will more successful the next time around.

Related Content

Esther Care, Helyn Kim, Alvin Vista

October 17, 2017

David Owen, Alvin Vista

November 15, 2017

Loren Clarke, Esther Care

December 5, 2017

Global Education K-12 Education

Global Economy and Development

Center for Universal Education

Ariell Bertrand, Melissa Arnold Lyon, Rebecca Jacobsen

April 18, 2024

Modupe (Mo) Olateju, Grace Cannon

April 15, 2024

Phillip Levine

April 12, 2024

New Designs for School 5 Steps to Teaching Students a Problem-Solving Routine

Jeff Heyck-Williams (He, His, Him) Director of the Two Rivers Learning Institute in Washington, DC

We’ve all had the experience of truly purposeful, authentic learning and know how valuable it is. Educators are taking the best of what we know about learning, student support, effective instruction, and interpersonal skill-building to completely reimagine schools so that students experience that kind of purposeful learning all day, every day.

Students can use the 5 steps in this simple routine to solve problems across the curriculum and throughout their lives.

When I visited a fifth-grade class recently, the students were tackling the following problem:

If there are nine people in a room and every person shakes hands exactly once with each of the other people, how many handshakes will there be? How can you prove your answer is correct using a model or numerical explanation?

There were students on the rug modeling people with Unifix cubes. There were kids at one table vigorously shaking each other’s hand. There were kids at another table writing out a diagram with numbers. At yet another table, students were working on creating a numeric expression. What was common across this class was that all of the students were productively grappling around the problem.

On a different day, I was out at recess with a group of kindergarteners who got into an argument over a vigorous game of tag. Several kids were arguing about who should be “it.” Many of them insisted that they hadn’t been tagged. They all agreed that they had a problem. With the assistance of the teacher they walked through a process of identifying what they knew about the problem and how best to solve it. They grappled with this very real problem to come to a solution that all could agree upon.

Then just last week, I had the pleasure of watching a culminating showcase of learning for our 8th graders. They presented to their families about their project exploring the role that genetics plays in our society. Tackling the problem of how we should or should not regulate gene research and editing in the human population, students explored both the history and scientific concerns about genetics and the ethics of gene editing. Each student developed arguments about how we as a country should proceed in the burgeoning field of human genetics which they took to Capitol Hill to share with legislators. Through the process students read complex text to build their knowledge, identified the underlying issues and questions, and developed unique solutions to this very real problem.

Problem-solving is at the heart of each of these scenarios, and an essential set of skills our students need to develop. They need the abilities to think critically and solve challenging problems without a roadmap to solutions. At Two Rivers Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., we have found that one of the most powerful ways to build these skills in students is through the use of a common set of steps for problem-solving. These steps, when used regularly, become a flexible cognitive routine for students to apply to problems across the curriculum and their lives.

The Problem-Solving Routine

At Two Rivers, we use a fairly simple routine for problem solving that has five basic steps. The power of this structure is that it becomes a routine that students are able to use regularly across multiple contexts. The first three steps are implemented before problem-solving. Students use one step during problem-solving. Finally, they finish with a reflective step after problem-solving.

Problem Solving from Two Rivers Public Charter School

Before Problem-Solving: The KWI

The three steps before problem solving: we call them the K-W-I.

The “K” stands for “know” and requires students to identify what they already know about a problem. The goal in this step of the routine is two-fold. First, the student needs to analyze the problem and identify what is happening within the context of the problem. For example, in the math problem above students identify that they know there are nine people and each person must shake hands with each other person. Second, the student needs to activate their background knowledge about that context or other similar problems. In the case of the handshake problem, students may recognize that this seems like a situation in which they will need to add or multiply.

The “W” stands for “what” a student needs to find out to solve the problem. At this point in the routine the student always must identify the core question that is being asked in a problem or task. However, it may also include other questions that help a student access and understand a problem more deeply. For example, in addition to identifying that they need to determine how many handshakes in the math problem, students may also identify that they need to determine how many handshakes each individual person has or how to organize their work to make sure that they count the handshakes correctly.

The “I” stands for “ideas” and refers to ideas that a student brings to the table to solve a problem effectively. In this portion of the routine, students list the strategies that they will use to solve a problem. In the example from the math class, this step involved all of the different ways that students tackled the problem from Unifix cubes to creating mathematical expressions.

This KWI routine before problem solving sets students up to actively engage in solving problems by ensuring they understand the problem and have some ideas about where to start in solving the problem. Two remaining steps are equally important during and after problem solving.

The power of teaching students to use this routine is that they develop a habit of mind to analyze and tackle problems wherever they find them.

During Problem-Solving: The Metacognitive Moment

The step that occurs during problem solving is a metacognitive moment. We ask students to deliberately pause in their problem-solving and answer the following questions: “Is the path I’m on to solve the problem working?” and “What might I do to either stay on a productive path or readjust my approach to get on a productive path?” At this point in the process, students may hear from other students that have had a breakthrough or they may go back to their KWI to determine if they need to reconsider what they know about the problem. By naming explicitly to students that part of problem-solving is monitoring our thinking and process, we help them become more thoughtful problem solvers.

After Problem-Solving: Evaluating Solutions

As a final step, after students solve the problem, they evaluate both their solutions and the process that they used to arrive at those solutions. They look back to determine if their solution accurately solved the problem, and when time permits they also consider if their path to a solution was efficient and how it compares to other students’ solutions.

The power of teaching students to use this routine is that they develop a habit of mind to analyze and tackle problems wherever they find them. This empowers students to be the problem solvers that we know they can become.

Jeff Heyck-Williams (He, His, Him)

Director of the two rivers learning institute.

Jeff Heyck-Williams is the director of the Two Rivers Learning Institute and a founder of Two Rivers Public Charter School. He has led work around creating school-wide cultures of mathematics, developing assessments of critical thinking and problem-solving, and supporting project-based learning.

Read More About New Designs for School

NGLC Invites Applications from New England High School Teams for Our Fall 2024 Learning Excursion

March 21, 2024

Bring Your Vision for Student Success to Life with NGLC and Bravely

March 13, 2024

How to Nurture Diverse and Inclusive Classrooms through Play

Rebecca Horrace, Playful Insights Consulting, and Laura Dattile, PlanToys USA

March 5, 2024

Why Every Educator Needs to Teach Problem-Solving Skills

Strong problem-solving skills will help students be more resilient and will increase their academic and career success .

Want to learn more about how to measure and teach students’ higher-order skills, including problem solving, critical thinking, and written communication?

Problem-solving skills are essential in school, careers, and life.

Problem-solving skills are important for every student to master. They help individuals navigate everyday life and find solutions to complex issues and challenges. These skills are especially valuable in the workplace, where employees are often required to solve problems and make decisions quickly and effectively.

Problem-solving skills are also needed for students’ personal growth and development because they help individuals overcome obstacles and achieve their goals. By developing strong problem-solving skills, students can improve their overall quality of life and become more successful in their personal and professional endeavors.

Problem-Solving Skills Help Students…

develop resilience.

Problem-solving skills are an integral part of resilience and the ability to persevere through challenges and adversity. To effectively work through and solve a problem, students must be able to think critically and creatively. Critical and creative thinking help students approach a problem objectively, analyze its components, and determine different ways to go about finding a solution.

This process in turn helps students build self-efficacy . When students are able to analyze and solve a problem, this increases their confidence, and they begin to realize the power they have to advocate for themselves and make meaningful change.

When students gain confidence in their ability to work through problems and attain their goals, they also begin to build a growth mindset . According to leading resilience researcher, Carol Dweck, “in a growth mindset, people believe that their most basic abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work—brains and talent are just the starting point. This view creates a love of learning and a resilience that is essential for great accomplishment.”

Set and Achieve Goals

Students who possess strong problem-solving skills are better equipped to set and achieve their goals. By learning how to identify problems, think critically, and develop solutions, students can become more self-sufficient and confident in their ability to achieve their goals. Additionally, problem-solving skills are used in virtually all fields, disciplines, and career paths, which makes them important for everyone. Building strong problem-solving skills will help students enhance their academic and career performance and become more competitive as they begin to seek full-time employment after graduation or pursue additional education and training.

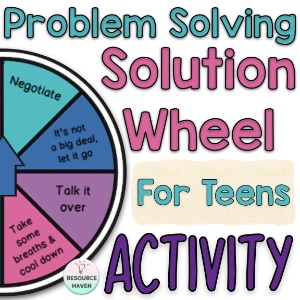

Resolve Conflicts

In addition to increased social and emotional skills like self-efficacy and goal-setting, problem-solving skills teach students how to cooperate with others and work through disagreements and conflicts. Problem-solving promotes “thinking outside the box” and approaching a conflict by searching for different solutions. This is a very different (and more effective!) method than a more stagnant approach that focuses on placing blame or getting stuck on elements of a situation that can’t be changed.

While it’s natural to get frustrated or feel stuck when working through a conflict, students with strong problem-solving skills will be able to work through these obstacles, think more rationally, and address the situation with a more solution-oriented approach. These skills will be valuable for students in school, their careers, and throughout their lives.

Achieve Success

We are all faced with problems every day. Problems arise in our personal lives, in school and in our jobs, and in our interactions with others. Employers especially are looking for candidates with strong problem-solving skills. In today’s job market, most jobs require the ability to analyze and effectively resolve complex issues. Students with strong problem-solving skills will stand out from other applicants and will have a more desirable skill set.

In a recent opinion piece published by The Hechinger Report , Virgel Hammonds, Chief Learning Officer at KnowledgeWorks, stated “Our world presents increasingly complex challenges. Education must adapt so that it nurtures problem solvers and critical thinkers.” Yet, the “traditional K–12 education system leaves little room for students to engage in real-world problem-solving scenarios.” This is the reason that a growing number of K–12 school districts and higher education institutions are transforming their instructional approach to personalized and competency-based learning, which encourage students to make decisions, problem solve and think critically as they take ownership of and direct their educational journey.

Problem-Solving Skills Can Be Measured and Taught

Research shows that problem-solving skills can be measured and taught. One effective method is through performance-based assessments which require students to demonstrate or apply their knowledge and higher-order skills to create a response or product or do a task.

What Are Performance-Based Assessments?

With the No Child Left Behind Act (2002), the use of standardized testing became the primary way to measure student learning in the U.S. The legislative requirements of this act shifted the emphasis to standardized testing, and this led to a decline in nontraditional testing methods .

But many educators, policy makers, and parents have concerns with standardized tests. Some of the top issues include that they don’t provide feedback on how students can perform better, they don’t value creativity, they are not representative of diverse populations, and they can be disadvantageous to lower-income students.

While standardized tests are still the norm, U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona is encouraging states and districts to move away from traditional multiple choice and short response tests and instead use performance-based assessment, competency-based assessments, and other more authentic methods of measuring students abilities and skills rather than rote learning.

Performance-based assessments measure whether students can apply the skills and knowledge learned from a unit of study. Typically, a performance task challenges students to use their higher-order skills to complete a project or process. Tasks can range from an essay to a complex proposal or design.

Preview a Performance-Based Assessment

Want a closer look at how performance-based assessments work? Preview CAE’s K–12 and Higher Education assessments and see how CAE’s tools help students develop critical thinking, problem-solving, and written communication skills.

Performance-Based Assessments Help Students Build and Practice Problem-Solving Skills

In addition to effectively measuring students’ higher-order skills, including their problem-solving skills, performance-based assessments can help students practice and build these skills. Through the assessment process, students are given opportunities to practically apply their knowledge in real-world situations. By demonstrating their understanding of a topic, students are required to put what they’ve learned into practice through activities such as presentations, experiments, and simulations.

This type of problem-solving assessment tool requires students to analyze information and choose how to approach the presented problems. This process enhances their critical thinking skills and creativity, as well as their problem-solving skills. Unlike traditional assessments based on memorization or reciting facts, performance-based assessments focus on the students’ decisions and solutions, and through these tasks students learn to bridge the gap between theory and practice.

Performance-based assessments like CAE’s College and Career Readiness Assessment (CRA+) and Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA+) provide students with in-depth reports that show them which higher-order skills they are strongest in and which they should continue to develop. This feedback helps students and their teachers plan instruction and supports to deepen their learning and improve their mastery of critical skills.

Explore CAE’s Problem-Solving Assessments

CAE offers performance-based assessments that measure student proficiency in higher-order skills including problem solving, critical thinking, and written communication.

- College and Career Readiness Assessment (CCRA+) for secondary education and

- Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA+) for higher education.

Our solution also includes instructional materials, practice models, and professional development.

We can help you create a program to build students’ problem-solving skills that includes:

- Measuring students’ problem-solving skills through a performance-based assessment

- Using the problem-solving assessment data to inform instruction and tailor interventions

- Teaching students problem-solving skills and providing practice opportunities in real-life scenarios

- Supporting educators with quality professional development

Get started with our problem-solving assessment tools to measure and build students’ problem-solving skills today! These skills will be invaluable to students now and in the future.

Ready to Get Started?

Learn more about cae’s suite of products and let’s get started measuring and teaching students important higher-order skills like problem solving..

- WordPress.org

- Documentation

- Learn WordPress

- Members Newsfeed

20 Problem-Solving Activities for Middle School Students

- Middle School Education

Introduction:

As students progress through middle school, it becomes increasingly important to develop their problem-solving skills. By engaging in problem-solving activities, students can enhance their critical thinking abilities, foster creativity, and become better prepared for the challenges they may face both in and out of the classroom. Here are 20 problem-solving activities that are perfect for middle school students.

1. Brainstorming Sessions: Encourage students to share their ideas on a particular topic or issue, fostering a collaborative environment that promotes creative problem solving.

2. Riddles: Challenge students with riddles that require critical thinking and lateral thinking skills to determine the answers.

3. Sudoku: Introduce sudoku puzzles as a fun and challenging math-based activity.

4. Chess Club: Encourage students to participate in chess clubs or tournaments to practice strategic thinking.

5. Escape Rooms: Plan an age-appropriate escape room activity to develop teamwork and problem-solving skills among the students.

6. Role-Playing Exercises: Use role-playing scenarios to allow students to think critically about real-life situations and practice problem-solving strategies.

7. Science Experiments: Design science experiments that require students to troubleshoot problems and test possible solutions.

8. Word Problems: Incorporate word problems in math lessons, encouraging students to use logic and math skills to solve them.

9. Puzzle Stations: Set up different puzzle stations around the classroom where students can work on spatial reasoning, logic puzzles, and other brain teasers during free time.

10. Debates: Organize debates on controversial topics, allowing students to present and argue their views while developing their critical thinking and persuasion skills.

11. Engineering Challenges: Provide engineering-based challenges such as bridge building or packaging design activities that require teamwork and creative problem solving.

12. Storytelling Workshops: Host a storytelling workshop where students collaborate to create stories from a given prompt and gradually face more complex narrative challenges.

13. Coding Clubs: Support students in learning coding basics and encourage them to develop problem-solving skills through coding projects.

14. Treasure Hunts: Create treasure hunts with clues that require problem solving, reasoning, and collaboration among the students.

15. Cooperative Games: Facilitate games that promote cooperation and communication, such as “human knot” or “cross the lava.”

16. Geocaching: Introduce geocaching as a fun activity where students use GPS devices to locate hidden objects and work as a team to solve puzzle-like tasks.

17. Exploratory Research Projects: Assign open-ended research projects that require students to investigate topics of interest and solve problems or answer questions through their research efforts.

18. Mock Trials: Set up mock trials in which students participate as lawyers, witnesses, or jury members, allowing them to analyze cases and think through legal problem-solving strategies.

19. Creative Writing Prompts: Share creative writing prompts requiring students to think critically about characters’ actions and decisions within fictional scenarios.

20. Invention Convention: Host an invention convention where students present their unique solutions to everyday problems, fostering creativity and innovative thinking.

Conclusion:

Problem-solving activities are essential for middle school students as they help in cultivating valuable life skills necessary to tackle real-world challenges. These 20 activities provide diverse and engaging opportunities for students to develop key problem-solving skills while fostering creativity, communication, critical thinking, and collaboration. Teachers and educators can easily adapt these activities to suit the individual needs of their middle school classrooms.

Related Articles

Starting at a new school can be an exciting yet nerve-wracking experience…

Introduction: As middle schoolers transition into more independence, it's crucial that they…

1. Unpredictable Growth Spurts: Middle school teachers witness students entering their classrooms…

Pedagogue is a social media network where educators can learn and grow. It's a safe space where they can share advice, strategies, tools, hacks, resources, etc., and work together to improve their teaching skills and the academic performance of the students in their charge.

If you want to collaborate with educators from around the globe, facilitate remote learning, etc., sign up for a free account today and start making connections.

Pedagogue is Free Now, and Free Forever!

- New? Start Here

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Registration

Don't you have an account? Register Now! it's really simple and you can start enjoying all the benefits!

We just sent you an Email. Please Open it up to activate your account.

I allow this website to collect and store submitted data.

- Our Mission

Guiding Students to Be Independent Problem-Solvers in STEM Classrooms

Teaching high school students how to plan to solve a problem in science, technology, engineering, and math is a crucial step.

Teaching students to become independent problem-solvers can be a challenging task, especially with virtual teaching during the pandemic. For some students, solving problems is not intuitive, and they need to learn how to think about solving problems from a general perspective. As experts, teachers often do not realize that there are implicit skills and ways of thinking that may not be obvious or known to our students.

5 Strategies to Explicitly Model and Teach Problem-Solving Skills

1. Model hidden thinking involved in solving a problem. When solving a problem, I talk about every aspect of what I am doing out loud. In fact, I over-talk, providing reasoning for every step. For example, when solving a dimensional-analysis problem, I will include descriptions like, “OK, I am going to look for any numbers that I can cancel. I know I can cancel or reduce if I see a number in the numerator and another number in the denominator that have a common factor.”

I will even include moments of vulnerability and model the fact that I don’t always know what to do, but I will discuss my options and my decision process. I sometimes intentionally make mistakes and then use methods to check my work to correct my errors. It’s essential that we explicitly show students this internal dialogue to model problem-solving.

2. Facilitate student talk during problem-solving. I do my best to never solve problems for students, even if they ask me. This includes whole-class lessons and working with students in small groups or individually. Using the Socratic method, I ask many questions of the students. The questions can be as simple as “What do we do next?” or “What are options of what we can do?”

Once during a classroom observation, I was told that in a span of 10 minutes, I asked more than 72 questions. This models the questions that the students can use in self-talk to guide them in the problem-solving process. After the first test, many students say that they could hear my voice asking them the same questions over and over, but what they’re really learning are advanced problem-solving skills they can extend to future contexts.

We can also provide deeper understanding with questions such as “Why do we do that?” These provide reasoning and value to the actions of each step in the problem-solving process, further solidifying the students’ understanding of the concepts and skills.

3. Include discussion for planning for each problem. Teachers instinctively plan problems. Students, as novice learners, often do not know how to plan a problem. They look at a problem, see it as foreign, and don’t know where to begin. They give up.

Research shows that planning how to solve the problem is an essential step for novice learners. Provide a structure or protocol for students. It can include the following: identify and write the data with units for a problem, identify equations to be used, identify and write what they’re trying to solve for, draw a relevant vector diagram, and brainstorm possible steps.

4. Emphasize the process, not final answers. Often, when checking individual work, we ask for the final answers. But what if instead of asking who has the answer, we ask who has the method to solve it? When students ask for correct answers, it’s natural to provide an immediate response. Instead, we should reply with guiding questions to facilitate the process of their solving the problems for themselves.

Often, I don’t even calculate the answer in the final step and ask if we all agree on the steps. The conversation is especially valuable when different methods are volunteered, and we can analyze the advantages of each. I want the students to check our work and not look at a simple result at the end of the problem to confirm their work. This shifts students’ attention to look at the details of the steps and not glance at the end of the work for the final answer. Further, grading can include points for steps and not the final solution.

5. Teach explicitly problem solving. After solving problems, students can create their own problem-solving strategy that they write on a note card. Collect responses from students and create a class protocol that you post on your learning management system or in your physical classroom space. Scaffold further with a two-column approach. In the left column, students show the work, and in the right column, they explain and justify what they did and why. The act of adding a justification will make students think about their actions. This will improve the connection between conceptual ideas and the problem-solving itself.

These are only a few strategies to get your students intentionally thinking about problem-solving from a general perspective beyond focusing on specific problems and memorizing steps. There are many ways to model and teach the skill of problem-solving that encourage them to think about the process explicitly.

Chapter 9: Facilitating Complex Thinking

Problem-solving.

Somewhat less open-ended than creative thinking is problem solving , the analysis and solution of tasks or situations that are complex or ambiguous and that pose difficulties or obstacles of some kind (Mayer & Wittrock, 2006). Problem solving is needed, for example, when a physician analyzes a chest X-ray: a photograph of the chest is far from clear and requires skill, experience, and resourcefulness to decide which foggy-looking blobs to ignore, and which to interpret as real physical structures (and therefore real medical concerns). Problem solving is also needed when a grocery store manager has to decide how to improve the sales of a product: should she put it on sale at a lower price, or increase publicity for it, or both? Will these actions actually increase sales enough to pay for their costs?

Example 1: Problem Solving in the Classroom

Problem solving happens in classrooms when teachers present tasks or challenges that are deliberately complex and for which finding a solution is not straightforward or obvious. The responses of students to such problems, as well as the strategies for assisting them, show the key features of problem solving. Consider this example, and students’ responses to it. We have numbered and named the paragraphs to make it easier to comment about them individually:

Scene #1: A problem to be solved

A teacher gave these instructions: “Can you connect all of the dots below using only four straight lines?” She drew the following display on the chalkboard:

The problem itself and the procedure for solving it seemed very clear: simply experiment with different arrangements of four lines. But two volunteers tried doing it at the board, but were unsuccessful. Several others worked at it at their seats, but also without success.

Scene #2: Coaxing students to re-frame the problem

When no one seemed to be getting it, the teacher asked, “Think about how you’ve set up the problem in your mind—about what you believe the problem is about. For instance, have you made any assumptions about how long the lines ought to be? Don’t stay stuck on one approach if it’s not working!”

Scene #3: Alicia abandons a fixed response

After the teacher said this, Alicia indeed continued to think about how she saw the problem. “The lines need to be no longer than the distance across the square,” she said to herself. So she tried several more solutions, but none of them worked either.

The teacher walked by Alicia’s desk and saw what Alicia was doing. She repeated her earlier comment: “Have you assumed anything about how long the lines ought to be?”

Alicia stared at the teacher blankly, but then smiled and said, “Hmm! You didn’t actually say that the lines could be no longer than the matrix! Why not make them longer?” So she experimented again using oversized lines and soon discovered a solution:

Scene #4: Willem’s and Rachel’s alternative strategies

Meanwhile, Willem worked on the problem. As it happened, Willem loved puzzles of all kinds, and had ample experience with them. He had not, however, seen this particular problem. “It must be a trick,” he said to himself, because he knew from experience that problems posed in this way often were not what they first appeared to be. He mused to himself: “Think outside the box, they always tell you. . .” And that was just the hint he needed: he drew lines outside the box by making them longer than the matrix and soon came up with this solution:

When Rachel went to work, she took one look at the problem and knew the answer immediately: she had seen this problem before, though she could not remember where. She had also seen other drawing-related puzzles, and knew that their solution always depended on making the lines longer, shorter, or differently angled than first expected. After staring at the dots briefly, she drew a solution faster than Alicia or even Willem. Her solution looked exactly like Willem’s.

This story illustrates two common features of problem solving: the effect of degree of structure or constraint on problem solving, and the effect of mental obstacles to solving problems. The next sections discuss each of these features, and then looks at common techniques for solving problems.

The effect of constraints: well-structured versus ill-structured problems

Problems vary in how much information they provide for solving a problem, as well as in how many rules or procedures are needed for a solution. A well-structured problem provides much of the information needed and can in principle be solved using relatively few clearly understood rules. Classic examples are the word problems often taught in math lessons or classes: everything you need to know is contained within the stated problem and the solution procedures are relatively clear and precise. An ill-structured problem has the converse qualities: the information is not necessarily within the problem, solution procedures are potentially quite numerous, and a multiple solutions are likely (Voss, 2006). Extreme examples are problems like “How can the world achieve lasting peace?” or “How can teachers insure that students learn?”

By these definitions, the nine-dot problem is relatively well-structured—though not completely. Most of the information needed for a solution is provided in Scene #1: there are nine dots shown and instructions given to draw four lines. But not all necessary information was given: students needed to consider lines that were longer than implied in the original statement of the problem. Students had to “think outside the box,” as Willem said—in this case, literally.

When a problem is well-structured, so are its solution procedures likely to be as well. A well-defined procedure for solving a particular kind of problem is often called an algorithm ; examples are the procedures for multiplying or dividing two numbers or the instructions for using a computer (Leiserson, et al., 2001). Algorithms are only effective when a problem is very well-structured and there is no question about whether the algorithm is an appropriate choice for the problem. In that situation it pretty much guarantees a correct solution. They do not work well, however, with ill-structured problems, where they are ambiguities and questions about how to proceed or even about precisely what the problem is about. In those cases it is more effective to use heuristics , which are general strategies—“rules of thumb,” so to speak—that do not always work, but often do, or that provide at least partial solutions. When beginning research for a term paper, for example, a useful heuristic is to scan the library catalogue for titles that look relevant. There is no guarantee that this strategy will yield the books most needed for the paper, but the strategy works enough of the time to make it worth trying.

In the nine-dot problem, most students began in Scene #1 with a simple algorithm that can be stated like this: “Draw one line, then draw another, and another, and another.” Unfortunately this simple procedure did not produce a solution, so they had to find other strategies for a solution. Three alternatives are described in Scenes #3 (for Alicia) and 4 (for Willem and Rachel). Of these, Willem’s response resembled a heuristic the most: he knew from experience that a good general strategy that often worked for such problems was to suspect a deception or trick in how the problem was originally stated. So he set out to question what the teacher had meant by the word line , and came up with an acceptable solution as a result.

Common obstacles to solving problems

The example also illustrates two common problems that sometimes happen during problem solving. One of these is functional fixedness : a tendency to regard the functions of objects and ideas as fixed (German & Barrett, 2005). Over time, we get so used to one particular purpose for an object that we overlook other uses. We may think of a dictionary, for example, as necessarily something to verify spellings and definitions, but it also can function as a gift, a doorstop, or a footstool. For students working on the nine-dot matrix described in the last section, the notion of “drawing” a line was also initially fixed; they assumed it to be connecting dots but not extending lines beyond the dots. Functional fixedness sometimes is also called response set , the tendency for a person to frame or think about each problem in a series in the same way as the previous problem, even when doing so is not appropriate to later problems. In the example of the nine-dot matrix described above, students often tried one solution after another, but each solution was constrained by a set response not to extend any line beyond the matrix.

Functional fixedness and the response set are obstacles in problem representation , the way that a person understands and organizes information provided in a problem. If information is misunderstood or used inappropriately, then mistakes are likely—if indeed the problem can be solved at all. With the nine-dot matrix problem, for example, construing the instruction to draw four lines as meaning “draw four lines entirely within the matrix” means that the problem simply could not be solved. For another, consider this problem: “The number of water lilies on a lake doubles each day. Each water lily covers exactly one square foot. If it takes 100 days for the lilies to cover the lake exactly, how many days does it take for the lilies to cover exactly half of the lake?” If you think that the size of the lilies affects the solution to this problem, you have not represented the problem correctly. Information about lily size is not relevant to the solution, and only serves to distract from the truly crucial information, the fact that the lilies double their coverage each day. (The answer, incidentally, is that the lake is half covered in 99 days; can you think why?)

Strategies to assist problem solving

Just as there are cognitive obstacles to problem solving, there are also general strategies that help the process be successful, regardless of the specific content of a problem (Thagard, 2005). One helpful strategy is problem analysis —identifying the parts of the problem and working on each part separately. Analysis is especially useful when a problem is ill-structured. Consider this problem, for example: “Devise a plan to improve bicycle transportation in the city.” Solving this problem is easier if you identify its parts or component subproblems, such as (1) installing bicycle lanes on busy streets, (2) educating cyclists and motorists to ride safely, (3) fixing potholes on streets used by cyclists, and (4) revising traffic laws that interfere with cycling. Each separate subproblem is more manageable than the original, general problem. The solution of each subproblem contributes the solution of the whole, though of course is not equivalent to a whole solution.

Another helpful strategy is working backward from a final solution to the originally stated problem. This approach is especially helpful when a problem is well-structured but also has elements that are distracting or misleading when approached in a forward, normal direction. The water lily problem described above is a good example: starting with the day when all the lake is covered (Day 100), ask what day would it therefore be half covered (by the terms of the problem, it would have to be the day before, or Day 99). Working backward in this case encourages reframing the extra information in the problem (i. e. the size of each water lily) as merely distracting, not as crucial to a solution.

A third helpful strategy is analogical thinking —using knowledge or experiences with similar features or structures to help solve the problem at hand (Bassok, 2003). In devising a plan to improve bicycling in the city, for example, an analogy of cars with bicycles is helpful in thinking of solutions: improving conditions for both vehicles requires many of the same measures (improving the roadways, educating drivers). Even solving simpler, more basic problems is helped by considering analogies. A first grade student can partially decode unfamiliar printed words by analogy to words he or she has learned already. If the child cannot yet read the word screen , for example, he can note that part of this word looks similar to words he may already know, such as seen or green , and from this observation derive a clue about how to read the word screen . Teachers can assist this process, as you might expect, by suggesting reasonable, helpful analogies for students to consider.

Bassok, J. (2003). Analogical transfer in problem solving. In Davidson, J. & Sternberg, R. (Eds.). The psychology of problem solving. New York: Cambridge University Press.

German, T. & Barrett, H. (2005). Functional fixedness in a technologically sparse culture. Psychological Science, 16 (1), 1–5.

Leiserson, C., Rivest, R., Cormen, T., & Stein, C. (2001). Introduction to algorithms. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Luchins, A. & Luchins, E. (1994). The water-jar experiment and Einstellung effects. Gestalt Theory: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 16 (2), 101–121.

Mayer, R. & Wittrock, M. (2006). Problem-solving transfer. In D. Berliner & R. Calfee (Eds.), Handbook of Educational Psychology, pp. 47–62. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Thagard, R. (2005). Mind: Introduction to Cognitive Science, 2nd edition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Voss, J. (2006). Toulmin’s model and the solving of ill-structured problems. Argumentation, 19 (3), 321–329.

- Educational Psychology. Authored by : Kelvin Seifert and Rosemary Sutton. Located at : https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/BookDetail.aspx?bookId=153 . License : CC BY: Attribution

10 Problem-Solving Scenarios for High School Students

It is certainly common to come across difficult situations including forgetting an assignment at home or overusing your phone only to miss an important project deadline. We are always surrounded by little difficulties that might become bigger problems if not addressed appropriately.

Whether it is saving your friend from the addiction to social media platforms or communicating your personal boundaries to relatives, problem-solving skills are one of the important skills you need to acquire throughout the journey of life.

Do you think these skills are in-built with other high school students? Certainly not.

It takes innovative learning methodologies just like problem-solving scenarios that help you immerse in the subject matter with precision. With problem-solving scenarios, you come across a range of problems that help you build critical thinking skills, logical reasoning, and analytical techniques.

The article will take you through scenarios that are a combination of various problems that need to be addressed strategically and carefully. As you read ahead, make sure to brainstorm solutions and choose the best one that fits the scenario.

Helpful scenarios to build a problem-solving attitude in high schoolers

Learning through scenarios helps students look at situations from a completely analytical perspective. Problem-solving scenarios offer a combination of various situations that test the thinking skills and growth mindset of high school students. The below-mentioned scenarios are perfect for implementing problem-solving skills simply by allowing open discussions and contributions by students.

1. Uninvited Guests

You have arranged a party at your home after successfully winning the competition at the Science Fair. You invite everyone involved in the project however, one of your friends brings his cousin’s brother along. However, you have limited soft drink cans considering the number of invited people. How would you manage this situation without making anyone feel left out?

2. Communication Issues

A new teacher has joined the high school to teach about environmental conservation. She often involves students in different agriculture activities and workshops. However, one of your friends, John, is not able to understand the subject matter. He is unable to communicate his doubts to the teachers. How would you motivate him to talk to the teacher without the fear of judgment?

3. Friendship or Personal Choice?

The history teacher announced an exciting assignment opportunity that helps you explore ancient civilizations. You and your friend are pretty interested in doing the project as a team. One of your other friends, Jason, wants to join the team with limited knowledge and interest in the topic. Would you respect the friendship or deny him so you can score better on the assignment?

4. Peer Pressure

It is common for high schoolers to follow what their friends do. However, lately, your friends have discovered different ways of showing off their skills. While they do all the fun things, there are certain activities you are not interested in doing. It often puts you in trouble whether to go with friends or take a stand for what is right. Would you take the help of peer mentoring activities in school or try to initiate a direct conversation with them?

5. Team Building

Mr. Jason, the science teacher, assigns different projects and forms teams with random classmates. There are 7 people in each team who need to work towards project completion. As the group starts working, you notice that some members do not contribute at all. How will you ensure that everyone participates and coordinates with the team members?

6. Conflict Resolution

The drama club and the English club are famous clubs in the school. Both clubs organize various events for the students. This time, both clubs have a tiff because of the event venue. Both clubs need the same auditorium for the venue on the same date. How would you mediate to solve the issue and even make sure that club members are on good terms with each other?

7. Stress Management

Your school often conducts different activities or asks students stress survey questions to ensure their happiness and well-being. However, one of your friends always misses them. He gets frustrated and seems stressed throughout the day. What would you do to ensure that your friend gets his issue acknowledged by teachers?

8. Time Management

Your friend is always enthusiastic about new competitions in high school. He is running here and there to enroll and get certificates. In this case, he often misses important lectures and activities in class. Moreover, his parents complain that he misses swimming class too. How would you explain to him the importance of prioritizing and setting goals to solve this issue?

9. Educational Resources

You and your friends are avid readers and often take advice from books. While most must-read books for bibliophiles are read by you, it is important to now look for other books. However, you witness that the school library lacks other important books on philosophy and the non-fiction category. How would you escalate this issue to the higher authorities by addressing the needs of students?

10. Financial Planning

Finance is an important factor and that is why your parents help you plan your pocket money and budgeting. Off lately, they have stopped doing so considering that you can manage on your own. However, after a few months, you have started spending more on games and high-end school supplies. You realize that your spending habits are leading to loss of money and reduced savings. How shall you overcome this situation?

Wrapping Up

Involving students in different learning practices and innovative ways inspires them to think out of the box and make use of imagination skills. With the usage of different problem-solving scenarios, high school students get an opportunity to delve into realistic examples and consequences of different incidents.

Such scenarios offer an excellent way to promote understanding, critical thinking skills and enhance creativity. Ensure to use different activities and games for creating a comprehensive learning environment.

Sananda Bhattacharya, Chief Editor of TheHighSchooler, is dedicated to enhancing operations and growth. With degrees in Literature and Asian Studies from Presidency University, Kolkata, she leverages her educational and innovative background to shape TheHighSchooler into a pivotal resource hub. Providing valuable insights, practical activities, and guidance on school life, graduation, scholarships, and more, Sananda’s leadership enriches the journey of high school students.

Explore a plethora of invaluable resources and insights tailored for high schoolers at TheHighSchooler, under the guidance of Sananda Bhattacharya’s expertise. You can follow her on Linkedin

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Don’t Just Tell Students to Solve Problems. Teach Them How.

The positive impact of an innovative uc san diego problem-solving educational curriculum continues to grow.

- Daniel Kane - [email protected]

Published Date

Share this:, article content.

Problem solving is a critical skill for technical education and technical careers of all types. But what are best practices for teaching problem solving to high school and college students?

The University of California San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering is on the forefront of efforts to improve how problem solving is taught. This UC San Diego approach puts hands-on problem-identification and problem-solving techniques front and center. Over 1,500 students across the San Diego region have already benefited over the last three years from this program. In the 2023-2024 academic year, approximately 1,000 upper-level high school students will be taking the problem solving course in four different school districts in the San Diego region. Based on the positive results with college students, as well as high school juniors and seniors in the San Diego region, the project is getting attention from educators across the state of California, and around the nation and the world.

{/exp:typographee}

In Summer 2023, th e 27 community college students who took the unique problem-solving course developed at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering thrived, according to Alex Phan PhD, the Executive Director of Student Success at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering. Phan oversees the project.

Over the course of three weeks, these students from Southwestern College and San Diego City College poured their enthusiasm into problem solving through hands-on team engineering challenges. The students brimmed with positive energy as they worked together.

What was noticeably absent from this laboratory classroom: frustration.

“In school, we often tell students to brainstorm, but they don’t often know where to start. This curriculum gives students direct strategies for brainstorming, for identifying problems, for solving problems,” sai d Jennifer Ogo, a teacher from Kearny High School who taught the problem-solving course in summer 2023 at UC San Diego. Ogo was part of group of educators who took the course themselves last summer.

The curriculum has been created, refined and administered over the last three years through a collaboration between the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering and the UC San Diego Division of Extended Studies. The project kicked off in 2020 with a generous gift from a local philanthropist.

Not getting stuck

One of the overarching goals of this project is to teach both problem-identification and problem-solving skills that help students avoid getting stuck during the learning process. Stuck feelings lead to frustration – and when it’s a Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) project, that frustration can lead students to feel they don’t belong in a STEM major or a STEM career. Instead, the UC San Diego curriculum is designed to give students the tools that lead to reactions like “this class is hard, but I know I can do this!” – as Ogo, a celebrated high school biomedical sciences and technology teacher, put it.

Three years into the curriculum development effort, the light-hearted energy of the students combined with their intense focus points to success. On the last day of the class, Mourad Mjahed PhD, Director of the MESA Program at Southwestern College’s School of Mathematics, Science and Engineering came to UC San Diego to see the final project presentations made by his 22 MESA students.

“Industry is looking for students who have learned from their failures and who have worked outside of their comfort zones,” said Mjahed. The UC San Diego problem-solving curriculum, Mjahed noted, is an opportunity for students to build the skills and the confidence to learn from their failures and to work outside their comfort zone. “And from there, they see pathways to real careers,” he said.

What does it mean to explicitly teach problem solving?

This approach to teaching problem solving includes a significant focus on learning to identify the problem that actually needs to be solved, in order to avoid solving the wrong problem. The curriculum is organized so that each day is a complete experience. It begins with the teacher introducing the problem-identification or problem-solving strategy of the day. The teacher then presents case studies of that particular strategy in action. Next, the students get introduced to the day’s challenge project. Working in teams, the students compete to win the challenge while integrating the day’s technique. Finally, the class reconvenes to reflect. They discuss what worked and didn't work with their designs as well as how they could have used the day’s problem-identification or problem-solving technique more effectively.

The challenges are designed to be engaging – and over three years, they have been refined to be even more engaging. But the student engagement is about much more than being entertained. Many of the students recognize early on that the problem-identification and problem-solving skills they are learning can be applied not just in the classroom, but in other classes and in life in general.

Gabriel from Southwestern College is one of the students who saw benefits outside the classroom almost immediately. In addition to taking the UC San Diego problem-solving course, Gabriel was concurrently enrolled in an online computer science programming class. He said he immediately started applying the UC San Diego problem-identification and troubleshooting strategies to his coding assignments.

Gabriel noted that he was given a coding-specific troubleshooting strategy in the computer science course, but the more general problem-identification strategies from the UC San Diego class had been extremely helpful. It’s critical to “find the right problem so you can get the right solution. The strategies here,” he said, “they work everywhere.”

Phan echoed this sentiment. “We believe this curriculum can prepare students for the technical workforce. It can prepare students to be impactful for any career path.”

The goal is to be able to offer the course in community colleges for course credit that transfers to the UC, and to possibly offer a version of the course to incoming students at UC San Diego.

As the team continues to work towards integrating the curriculum in both standardized high school courses such as physics, and incorporating the content as a part of the general education curriculum at UC San Diego, the project is expected to impact thousands more students across San Diego annually.

Portrait of the Problem-Solving Curriculum

On a sunny Wednesday in July 2023, an experiential-learning classroom was full of San Diego community college students. They were about half-way through the three-week problem-solving course at UC San Diego, held in the campus’ EnVision Arts and Engineering Maker Studio. On this day, the students were challenged to build a contraption that would propel at least six ping pong balls along a kite string spanning the laboratory. The only propulsive force they could rely on was the air shooting out of a party balloon.

A team of three students from Southwestern College – Valeria, Melissa and Alondra – took an early lead in the classroom competition. They were the first to use a plastic bag instead of disposable cups to hold the ping pong balls. Using a bag, their design got more than half-way to the finish line – better than any other team at the time – but there was more work to do.

As the trio considered what design changes to make next, they returned to the problem-solving theme of the day: unintended consequences. Earlier in the day, all the students had been challenged to consider unintended consequences and ask questions like: When you design to reduce friction, what happens? Do new problems emerge? Did other things improve that you hadn’t anticipated?

Other groups soon followed Valeria, Melissa and Alondra’s lead and began iterating on their own plastic-bag solutions to the day’s challenge. New unintended consequences popped up everywhere. Switching from cups to a bag, for example, reduced friction but sometimes increased wind drag.

Over the course of several iterations, Valeria, Melissa and Alondra made their bag smaller, blew their balloon up bigger, and switched to a different kind of tape to get a better connection with the plastic straw that slid along the kite string, carrying the ping pong balls.

One of the groups on the other side of the room watched the emergence of the plastic-bag solution with great interest.

“We tried everything, then we saw a team using a bag,” said Alexander, a student from City College. His team adopted the plastic-bag strategy as well, and iterated on it like everyone else. They also chose to blow up their balloon with a hand pump after the balloon was already attached to the bag filled with ping pong balls – which was unique.

“I don’t want to be trying to put the balloon in place when it's about to explode,” Alexander explained.

Asked about whether the structured problem solving approaches were useful, Alexander’s teammate Brianna, who is a Southwestern College student, talked about how the problem-solving tools have helped her get over mental blocks. “Sometimes we make the most ridiculous things work,” she said. “It’s a pretty fun class for sure.”

Yoshadara, a City College student who is the third member of this team, described some of the problem solving techniques this way: “It’s about letting yourself be a little absurd.”

Alexander jumped back into the conversation. “The value is in the abstraction. As students, we learn to look at the problem solving that worked and then abstract out the problem solving strategy that can then be applied to other challenges. That’s what mathematicians do all the time,” he said, adding that he is already thinking about how he can apply the process of looking at unintended consequences to improve both how he plays chess and how he goes about solving math problems.

Looking ahead, the goal is to empower as many students as possible in the San Diego area and beyond to learn to problem solve more enjoyably. It’s a concrete way to give students tools that could encourage them to thrive in the growing number of technical careers that require sharp problem-solving skills, whether or not they require a four-year degree.

You May Also Like

Breakthrough study on post-traumatic stress disorder, creating a “greener,” more connected society, electronic health records unlock genetics of tobacco use disorder, following cellular lineage, stay in the know.

Keep up with all the latest from UC San Diego. Subscribe to the newsletter today.

You have been successfully subscribed to the UC San Diego Today Newsletter.

Campus & Community

Arts & culture, visual storytelling.

- Media Resources & Contacts

Signup to get the latest UC San Diego newsletters delivered to your inbox.

Award-winning publication highlighting the distinction, prestige and global impact of UC San Diego.

Popular Searches: Covid-19 Ukraine Campus & Community Arts & Culture Voices

Problem Solving Activities: 7 Strategies

- Critical Thinking

Problem solving can be a daunting aspect of effective mathematics teaching, but it does not have to be! In this post, I share seven strategic ways to integrate problem solving into your everyday math program.

In the middle of our problem solving lesson, my district math coordinator stopped by for a surprise walkthrough.

I was so excited!

We were in the middle of what I thought was the most brilliant math lesson– teaching my students how to solve problem solving tasks using specific problem solving strategies.

It was a proud moment for me!

Each week, I presented a new problem solving strategy and the students completed problems that emphasized the strategy.

Genius right?

After observing my class, my district coordinator pulled me aside to chat. I was excited to talk to her about my brilliant plan, but she told me I should provide the tasks and let my students come up with ways to solve the problems. Then, as students shared their work, I could revoice the student’s strategies and give them an official name.

What a crushing blow! Just when I thought I did something special, I find out I did it all wrong.

I took some time to consider her advice. Once I acknowledged she was right, I was able to make BIG changes to the way I taught problem solving in the classroom.

When I Finally Saw the Light

To give my students an opportunity to engage in more authentic problem solving which would lead them to use a larger variety of problem solving strategies, I decided to vary the activities and the way I approached problem solving with my students.

Problem Solving Activities

Here are seven ways to strategically reinforce problem solving skills in your classroom.

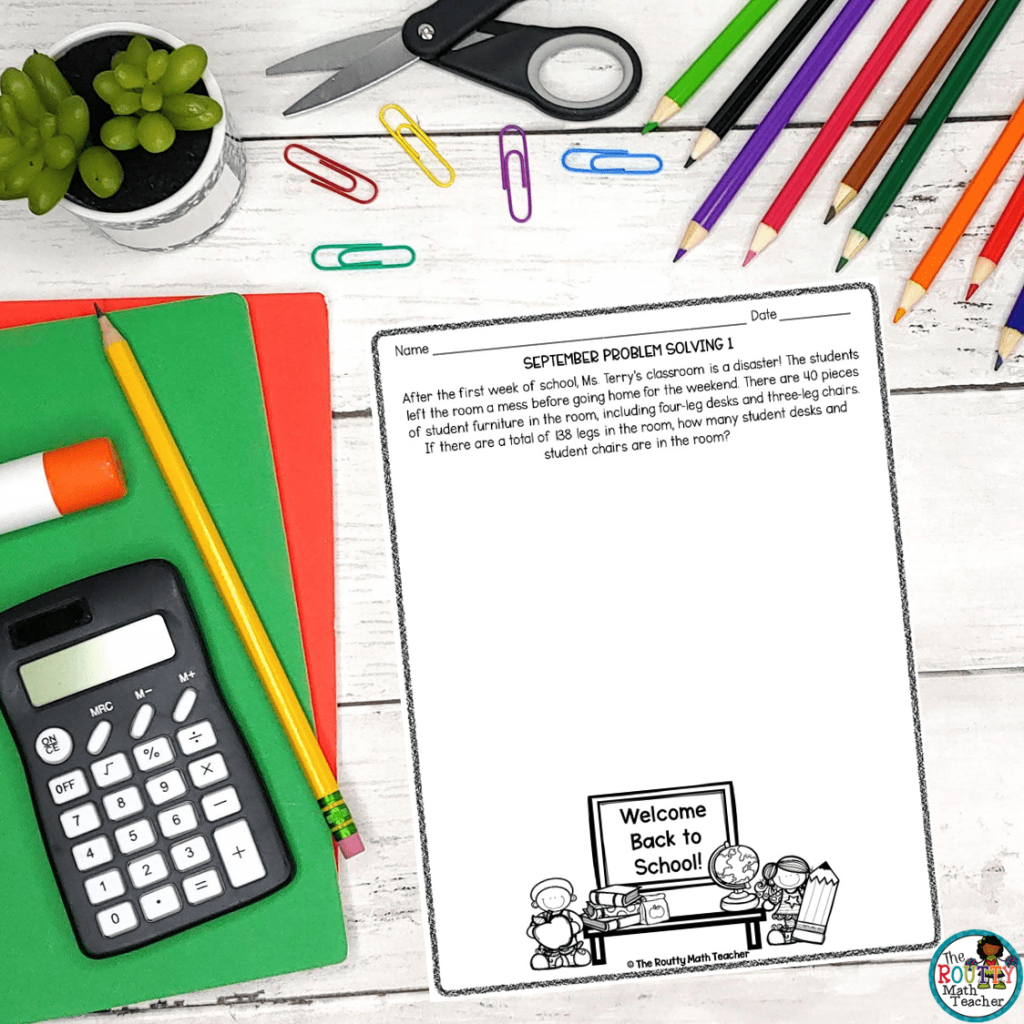

Seasonal Problem Solving

Many teachers use word problems as problem solving tasks. Instead, try engaging your students with non-routine tasks that look like word problems but require more than the use of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division to complete. Seasonal problem solving tasks and daily challenges are a perfect way to celebrate the season and have a little fun too!

Cooperative Problem Solving Tasks

Go cooperative! If you’ve got a few extra minutes, have students work on problem solving tasks in small groups. After working through the task, students create a poster to help explain their solution process and then post their poster around the classroom. Students then complete a gallery walk of the posters in the classroom and provide feedback via sticky notes or during a math talk session.

Notice and Wonder

Before beginning a problem solving task, such as a seasonal problem solving task, conduct a Notice and Wonder session. To do this, ask students what they notice about the problem. Then, ask them what they wonder about the problem. This will give students an opportunity to highlight the unique characteristics and conditions of the problem as they try to make sense of it.

Want a better experience? Remove the stimulus, or question, and allow students to wonder about the problem. Try it! You’ll gain some great insight into how your students think about a problem.

Math Starters

Start your math block with a math starter, critical thinking activities designed to get your students thinking about math and provide opportunities to “sneak” in grade-level content and skills in a fun and engaging way. These tasks are quick, designed to take no more than five minutes, and provide a great way to turn-on your students’ brains. Read more about math starters here !

Create your own puzzle box! The puzzle box is a set of puzzles and math challenges I use as fast finisher tasks for my students when they finish an assignment or need an extra challenge. The box can be a file box, file crate, or even a wall chart. It includes a variety of activities so all students can find a challenge that suits their interests and ability level.

Calculators

Use calculators! For some reason, this tool is not one many students get to use frequently; however, it’s important students have a chance to practice using it in the classroom. After all, almost everyone has access to a calculator on their cell phones. There are also some standardized tests that allow students to use them, so it’s important for us to practice using calculators in the classroom. Plus, calculators can be fun learning tools all by themselves!

Three-Act Math Tasks

Use a three-act math task to engage students with a content-focused, real-world problem! These math tasks were created with math modeling in mind– students are presented with a scenario and then given clues and hints to help them solve the problem. There are several sites where you can find these awesome math tasks, including Dan Meyer’s Three-Act Math Tasks and Graham Fletcher’s 3-Acts Lessons .

Getting the Most from Each of the Problem Solving Activities

When students participate in problem solving activities, it is important to ask guiding, not leading, questions. This provides students with the support necessary to move forward in their thinking and it provides teachers with a more in-depth understanding of student thinking. Selecting an initial question and then analyzing a student’s response tells teachers where to go next.

Ready to jump in? Grab a free set of problem solving challenges like the ones pictured using the form below.

Which of the problem solving activities will you try first? Respond in the comments below.

Shametria Routt Banks

- Assessment Tools

- Content and Standards

- Differentiation

- Math & Literature

- Math & Technology

- Math Routines

- Math Stations

- Virtual Learning

- Writing in Math

You may also like...

2 Responses

This is a very cool site. I hope it takes off and is well received by teachers. I work in mathematical problem solving and help prepare pre-service teachers in mathematics.

Thank you, Scott! Best wishes to you and your pre-service teachers this year!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

©2024 The Routty Math Teacher. All Rights Reserved. Designed by Ashley Hughes.

Privacy overview.

39 Best Problem-Solving Examples

Problem-solving is a process where you’re tasked with identifying an issue and coming up with the most practical and effective solution.

This indispensable skill is necessary in several aspects of life, from personal relationships to education to business decisions.

Problem-solving aptitude boosts rational thinking, creativity, and the ability to cooperate with others. It’s also considered essential in 21st Century workplaces.