Structured Clinical Management (SCM)

Learn about Anna Freud's Structured Clinical Management (SCM) training here.

About this training

Structured Clinical Management (SCM) is an evidence-based approach that enables generalist mental health practitioners to work effectively with people with borderline personality disorder.

SCM provides generalist mental staff with a coherent systematic approach to working with people with borderline personality disorder. It is based on a supportive approach with case management and advocacy support. There is an emphasis on problem-solving, effective crisis planning, medication review and assertive follow-up if appointments are missed.

Aims of this training

By the end of the three day training, participants will:

Understand the rationale and evidence base for SCM;

Show increased awareness of personality disorder;

Develop skills to treat people with personality disorder comorbid with affective and other disorders;

Be able to implement strategic and core processes of SCM.

Who is this training for?

The course is suitable for all mental health professionals currently working with patients who have a personality disorder or whose personality interferes with treatment. No specialist or high level psychological treatment skills are required to attend the course.

SCM has been implemented successfully by general mental health professionals without additional specialist training. It is particularly suitable for mental health nurses, graduate workers and others interested in the treatment of personality disorder.

Professor Anthony Bateman

MBT Training Consultant

David Rawlinson

Programme Director SCM

Mark Sampson

Consultant Clinical Psychologist and Clinical Lead

Tutor information

Professor Anthony W Bateman MA, FRCPsych

Prof Anthony Bateman is a Consultant Psychiatrist and Psychotherapist and MBT co-ordinator at Anna Freud; Visiting Professor University College, London; Honorary Professor in Psychotherapy University of Copenhagen.

He developed mentalization based treatment with Peter Fonagy for borderline personality disorder and wrote the manual for mental health professionals on Structured Clinical Management of Personality Disorder. He received a senior scientist award from British and Irish group for the Study of Personality Disorder in 2012 and in 2015 the annual award for “Achievement in the Field of Severe Personality Disorders” from the BPDRC in the USA.

David Rawlinson is the SCM co-ordinator and tutor at Anna Freud and Consultant Psychological Therapist; Associate Psychological Services Director - Community and Access; at West Cumbria Mental Health Community Treatment Team (CTT) and Complex Emotional Needs pathway lead in North Cumbria.

Mark Sampson is a consultant clinical psychologist and the clinical lead for personality disorder for 5bp NHS Foundation Trust.

Mark has extensive experience in personality disorder – he has been involved in local and national policy development (e.g. NICE guideline development group BPD) and is a member of the Clinical Reference Group for tier 4 personality disorder.

SCM commission

We currently run an SCM training programme funded by Health Education England for NHS England staff several times each year. We advise NHS England Staff to liaise with your service lead and HEE regional lead to request places on the HEE-funded SCM training programme. Anna Freud will deliver the SCM training programme for several cohorts of NHS England staff each year, over the next three years.

If this does not apply to you, we can deliver this training locally to organisations. The fee for the three-day programme delivered online is £750 per person and the training requires 28 - 36 participants. We charge an additional 10% fee for face-to-face delivery.

In addition to the three live days of training, attendees would be added to an online training platform to carry out 11 hours of self-guided work during the training. If you are interested in commissioning the SCM training, please email [email protected] .

Download the SCM Brochure

System requirements for online training

The online platform Zoom will be used to deliver this training. Prior to booking on, please ensure you meet the system requirements so you're able to join this training.

Before the training, please test your equipment is working by going to Zoom.us/test and follow the instructions.

Terms of booking

Upon booking, you will be asked to confirm that you have read and accept our terms and conditions and our privacy notice. Please read these documents before booking:

Terms and conditions

Privacy notice

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up-to-date with the latest training, conferences and events at Anna Freud.

Structured clinical management: general treatment strategies

Chapter 3 focuses on structured clinical management (SCM) as a treatment for borderline personality disorder (BPD). It describes the structure, pathway to assessment, process of assessment and diagnosis, crisis planning (including risk assessment, legal aspects, clinician and patient responsibilities, therapeutic alliance, substance abuse, stabilizing medication), and the treatment approach.

- Related Documents

Structured clinical management: core treatment strategies

Chapter 4 explores the core treatment strategies of structured clinical management (SCM) as a treatment for borderline personality disorder (BPD). It includes nonspecific interventions (interviewing, clinician attitude, authenticity and openness, empathy, validation, positive regard, advocacy) and specific interventions (problem-solving skills, tolerance of emotions, mood regulation, impulse control, sensitivity and interpersonal problems, self-harm).

Supplemental Material for Eight-Year Prospective Follow-Up of Mentalization-Based Treatment Versus Structured Clinical Management for People With Borderline Personality Disorder

Faculty opinions recommendation of randomized controlled trial of outpatient mentalization-based treatment versus structured clinical management for borderline personality disorder., evaluation of a novel risk assessment method for self-harm associated with borderline personality disorder.

Objectives: Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with frequent self-harm and suicidal behaviours. This study compared physician-assessed self-harm risk and intervention choice according to a (i) standard risk assessment and (ii) BPD-specific risk assessment methods. Methods: Forty-five junior and senior mental health physicians were assigned to standard or BPD-specific risk training groups. The assessment utilized a BPD case vignette containing four scenarios describing high/low lethality self-harm and chronic/new patterns of self-harm behaviour. Participants chose from among four interventions, each corresponding to a risk category. Results: Standard and BPD-specific groups were alike in their assessment of self-harm risk. Divergence occurred on intervention choice for assessments of low lethality, chronic risk ( p<.01) and high lethality, chronic risk ( p<.005). Overall, psychiatrists were more likely than their junior colleagues to correctly assess risk and management options. Conclusions: Although standard and BPD-specific methods are well aligned for assessing self harm-associated risk, BPD-specific training raised awareness of BPD-appropriate interventions, particularly in the context of chronic patterns of self-harm behaviour. Wider dissemination of BPD-specific risk training may enhance the confidence of mental health clinicians in identifying the nature of self-harm risk as well as the most clinically appropriate interventions for clients with BPD.

Borderline Personality Disorder

Until recently, borderline personality disorder (BPD) has been the stepchild of psychiatric disorders. Many researchers even questioned its existence. Clinicians have been reluctant to reveal the diagnosis to patients because of the stigma attached to it. But individuals with BPD suffer terribly and a significant proportion die by suicide and engage in nonsuicidal self-injury. The aim of this primer on BPD is to fill this void and provide clinicians with an accessible, easy-to-use, clinically oriented, evidenced-based guide for early-stage BPD. We present the most up to date data about BPD by leading experts in the field in a format accessible to trainees and professionals working with individuals with BPD and their family members. The volume is comprehensive and covers the etiology of BPD, its clinical presentation and comorbid disorders, genetics and neurobiology of BPD, effective treatment approaches to BPD, the role of advocacy, and the treatment of special subpopulations (e.g., forensic) in the clinical management of BPD.

Generalist psychiatric treatments for borderline personality disorder: the evidence base and common factors

Chapter 2 discusses generalist psychiatric treatments for borderline personality disorder (BPD). It introduces the rationale for seeking common factors in treatment and provide a brief overview of some relevant literature, outlines the four generalist treatments that have been shown to be effective (structured clinical management (SCM), general psychiatric management (GPM), good clinical care (GCC), and supportive psychotherapy (SP)), describes the outcome studies of the four treatments, and reviews commonalities of the treatments.

Differential Diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder from Bipolar Disorder

Many psychiatrists have reconceptualized borderline personality disorder (BPD) as a variant of bipolar disorder and, consistent with the treatment of bipolar disorder, emphasize the use of mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics in treatment. This change in diagnostic practice is unfortunate. BPD is a distinct diagnostic construct, and clients who fit this pattern require a fundamentally different treatment approach than what is typically recommended for bipolar disorder. The purpose of this article is to update counselors on the expansion of bipolar disorder in the psychiatric literature, present evidence for the validity of BPD, discuss strategies for the differential diagnosis of it from bipolar disorder, review proposed changes in DSM-V, and integrate the literature into a mental health counseling framework.

Stability of Borderline Personality Disorder

This study examines the course of illness and stability of borderline personality disorder (BPD) in a group of inpatients seen at a two-year follow-up. The diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, as established by the use of the Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines, did not change in 39 of the 65 subjects (60%) studied. Subjects who continued to show evidence of borderline psychopathology experienced more acute episodes of illness during the follow-up period and tended to be more involved in substance abuse. Impulsiveness and young age when first psychiatric care was received significantly predicted the presence of BPD features at follow-up.

The impact of borderline personality disorder on residential substance abuse treatment dropout among men

Gender differences in sexual preference and substance abuse of inpatients with borderline personality disorder, export citation format, share document.

- About this site

- Curricular Affairs Contact

- FID Philosophy

- Faculty Mentoring

- Educational Program Objectives

- ARiM Initiatives

- Faculty Support

- Active Learning Theory

- Curriculum Development

- Developmental Learning Theory

- Peer Review of Teaching

- Resources & Strategies

- Flipped Learning

- Teaching Guides

- Educational Strategies

- Large Group Sessions

- Team Learning

- Constructive Feedback

- Ed Tech & Training

- Med Ed Distinction Track

- Affiliate Clinical Faculty

- Faculty Instructional Development Series

- Microskills 1-Min Preceptor

- BDA for Teaching

- Med Ed Resources

- RIME Framework

- WBA in Clerkship

- About Instructional Tech

- Software Worth Using

- Apps for Learning

- Apps for Teaching

- Apps for Research

- Copyright Resources

- Application Online

- Program Goals

- Program Competence Areas

- Program Timeline

- Program Activities

- Projects & Presentations

- Participants

- SOS Series Calendar

- Presentation Tools

- Communication Tools

- Data Collection & Analysis

- Document Preparation

- Project Management Tools

You are here

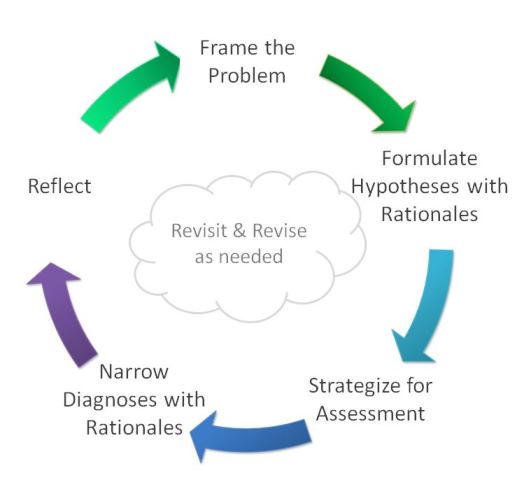

Structured approach to medical problem-solving.

To achieve the goals for the Clinical Reasoning Course, students learn a structured approach to medical problem solving that emphasizes the process skills, and combines self-regulation with collaborative/facilitated learning components. The idea is to promote deliberative self-regulation as well as the consultation of colleagues' ideas and perspectives while using a sy stematic approach to problem-solving .

The key to teaching problem-solving is effective problem-construction based on real-world situations that evince a range of cognitive dimensions and provide a framework or structure for solving them (Jonassen, 2000 ; also 2010 ).

The UA COM approach incorporates this stance in its structured approach to medical problem-solving, a hybrid of scientific method and Polya's ( 1954 ) model for problem-solving . ( Learn more about Polya's approach )

This 5-step medical problem-solving structure we use in the Clinical Reasoning Course (Figure below) is also inspired by the concept of evidence-based decision making, and is aligned with learning theory that underlies the developmental curriculum at the UA College of Medicine .

Problem-solving Step by Step

Each "step" focuses on the process of generating a desired outcome. For example, when students formulate hypotheses and articulate their reasoning for each, they are generating a list of provisional diagnoses.

We emphasize process by naming the step for how students will engage in producing that outcome, and not by the outcome itself.

By the time students work through a case they will have engaged in the kind of thinking and critical reflection highlighted by each step.

Why a structured approach?

The purpose of using a structured approach to medical problem-solving is to scaffold students' internalization of a systematic approach to clinical reasoning.

As students progress toward clinical years, they will need less scaffolding and greater challenges. The Clinical Reasoning Course is a longitudinal learning experience that expects to apply and extend what they are learning throughout the curriculum. The course is designed to increase challenges in content as well as the type of critical thinking and reflective reasoning.

Online Tools

Students use an online tool that visualizes this structure, allowing them to share what they think, and learn how peers develop their thinking in each case.

Related Resources

5-Step Guide Polya-How to Solve it Cognitive Error Dr. Putnam on the 5-steps

- Careers and training

- Accessible information

Structured Clinical Management

- South Community Services

This leaflet includes information about Structured Clinical Management (SCM). SCM is a treatment for people who have personality difficulties. SCM has been found to be as effective as other treatments such as Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT) and Mentalisation-Based Treatment (MBT) in helping people address their personality difficulties.

This leaflet may not be reproduced in whole or in part, without the permission of Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust

What is Structured Clinical Management? (SCM)

Structured Clinical Management (SCM), is a generalist treatment for people who have personality and relational difficulties. This may include problems with managing emotions, moods, triggers of distress, urge to deal with feelings and thoughts quickly and interpersonal situations that make you feel vulnerable or sensitive, such as feeling rejected being alone.

“Personality” refers to the way we think, feel and behave. Due to life experiences, difficulties can arise in these areas, particularly in how we relate to others.

If the difficulties are causing you great distress, are long-lasting and impact on many aspects of your life, over some considerable time, then help may be needed from mental health services.

SCM has been found to be as effective as other specialist treatments such as Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT) and Mentalisation-Based Treatment (MBT) in helping people address their personality and relational difficulties that are long lasting. Emotion and mood regulation, managing urges and interpersonal problems and quality of life all improve with SCM treatment, and are usually maintained over time. So, the outcomes aimed for are hopeful and good!

SCM can be accessed by people from diverse backgrounds, ages, gender and ethnicity.

Please see page seven of this leaflet for references which can provide further information about the development of SCM and its effectiveness.

Benefits and risks of SCM

The benefits of engaging and working in SCM treatment programme are described in this leaflet.

There are no significant risks associated with SCM however as with all therapies, it requires participants to think and talk about their difficulties in a collaborative way with their practitioner. This can be challenging, but you will have the opportunity to discuss any concerns you may have with your SCM practitioner. If you choose not to engage and work an SCM programme, other options will be discussed with you.

Is SCM right for me?

SCM may be helpful if you have difficulties with: • Managing your emotions and mood • Managing urges to act quickly (acting without time for thinking) • Self-harm and suicidal thoughts and actions • Making and keeping healthy and safe relationships • Problem solving in relationships and coping with emotions or urges.

What can I expect from SCM?

Your SCM practitioner (who may currently also be your care coordinator) will work with you through three SCM phases and offer you regular planned sessions so that you can learn skills in problem solving, managing emotions and urges to help you manage difficulties more effectively.

The three phases of SCM

Phase 1 – Introduction In the introductory phase you and your SCM practitioner will work on: • Understanding your difficulties and how they have developed • Setting short term and long term goals • Agreeing treatment contracts so you know what to expect and what is asked of you and what role your practioner and their team plays in your care plan • Developing a safety plan to help you in difficult times when you feel there is a crisis or ugent situation developing

Phase 2 – Intervention In the active intervention phase your SCM practitioner will help you to develop skills to address your problems and meet your goals by focusing on three key areas: • Understanding and managing emotions and moods • Understanding and managing relationships • Understanding and managing urges and behaviours that may be unsafe, including self-harm and suicidality

In this phase, you may be offered weekly group sessions as well as weekly( or less frequently as discussed with your practitioner) individual sessions, if a full programme is available in your area.

If a full programme is available, you will be given more information about this by your SCM practitioner in the introductory phase.

Phase 3 – Moving on In the moving on phase you and your SCM practitioner will review the skills you have developed, plan how you can maintain these in the future and explore any further resources you will need to maintain the changes. You may also consider exploring further therapy, gaining voluntary or paid work experience, returning to study, or developing links with different support groups in the community. Your practitioner will usually offer you some follow-up sessions to see how your are progressing within a period of around 6 months.

How long will SCM last?

The three phases of SCM typically last between 12-18 months, depending on your needs and the services available in your area.

We recommend that you attend SCM twice weekly (including one group and one individual session) if at all possible, as most people do best with a combined treatment of group plus individual sessions. However this may be changed to match your needs, local resources or your stage of recovery.

The length of time and commitment needed will be discussed with you individually as part of your goal setting and treatment contract.

Where does SCM take place?

SCM is usually delivered within community mental health settings, as this is where you will learn skills and strategies for solving life problems. Recovery happens best in the community rather than in hospital or a residential unit.

If hospital admission is necessary at any point, it is recommended that this is usually quite brief (from a few days to a couple of weeks), although at times may be longer if needed, and with a clear goal and timescales in mind.

Contact with your SCM practitioner will continue during the admission as far as possible.

No medications have been found effective for the longer term treatment of personality difficulties. If you have been prescribed medication in the past or currently, it is best if this is reviewed with you on a regular basis by your psychiatrist or pharmacist.

As part of SCM you will be offered psychiatric reviews to discuss the medications you are using, the function purpose and effectiveness of these, and any potential side effects. It may be necessary to reduce or stop any unhelpful medications. The frequency of psychiatric review will depend on your needs and will be discussed with you as part of your treatment planning.

Final Thoughts

We hope you have found this leaflet helpful in getting to know some basic information about what is involved when you consider an SCM approach to care and treatment. Please discuss the leaflet and any question you may have with your SCM practitioner. We wish you well in your SCM journey!

Useful websites

• National Institute for Health and Care Excellence www.nice.org.uk/guidance/conditions-and-diseases/mental-health-and-behavioural-conditions/personality-disorders

• The NHS website www.nhs.uk/conditions/personality-disorder

• Mind www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/personality-disorders/

• Rethink www.rethink.org/diagnosis-treatment/conditions/personality-disorders

• Bateman, A. W., & Krawitz, R. (2013). Borderline personality disorder: an evidence-based guide for generalist mental health professionals. Oxford University Press.

• Clarkin, J. F., Levy, K. N., Lenzenweger, M. F., & Kernberg, O. F. (2007). Evaluating three treatments for borderline personality disorder: A multiwave study. American journal of psychiatry, 164(6), 922-928.

• McMain, S. F., Links, P. S., Gnam, W. H., Guimond, T., Cardish, R. J., Korman, L., & Streiner, D. L. (2009). A randomized trial of dialectical behavior therapy versus general psychiatric management for borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(12), 1365-1374.

• Mitchell, S., Sampson, M. & Bateman, A. (2021). Structured Clinical Managment (SCM) for Personality Disorder: An Implementation Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Other formats, references and review

Further information about the content, reference sources or production of this leaflet can be obtained from the Patient Information Centre. If you would like to tell us what you think about this leaflet please get in touch.

This information can be made available in a range of formats on request (eg Braille, audio, larger print, easy read, BSL or other languages). Please contact the Patient Information Centre Tel: 0191 246 7288

Published by the Patient Information Centre 2022 Copyright, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust Ref, PIC/806/0122 V2 www.cntw.nhs.uk Tel: 0191 246 7288 Review date 2025

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Psychiatry

- v.16(1); 2016

A randomised controlled trial of mentalization-based treatment versus structured clinical management for patients with comorbid borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder

Anthony bateman.

1 University College London, London, UK

2 The Anna Freud Centre, London, UK

Jennifer O’Connell

3 Research Department of Clinical, Educational and Health Psychology, University College London, London, UK

Nicolas Lorenzini

Tessa gardner, peter fonagy, associated data.

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) is an under-researched mental disorder. Systematic reviews and policy documents identify ASPD as a priority area for further treatment research because of the scarcity of available evidence to guide clinicians and policymakers; no intervention has been established as the treatment of choice for this disorder. Mentalization-based treatment (MBT) is a psychotherapeutic treatment which specifically targets the ability to recognise and understand the mental states of oneself and others, an ability shown to be compromised in people with ASPD. The aim of the study discussed in this paper is to investigate whether MBT can be an effective treatment for alleviating symptoms of ASPD.

This paper reports on a sub-sample of patients from a randomised controlled trial of individuals recruited for treatment of suicidality, self-harm, and borderline personality disorder. The study investigates whether outpatients with comorbid borderline personality disorder and ASPD receiving MBT were more likely to show improvements in symptoms related to aggression than those offered a structured protocol of similar intensity but excluding MBT components.

The study found benefits from MBT for ASPD-associated behaviours in patients with comorbid BPD and ASPD, including the reduction of anger, hostility, paranoia, and frequency of self-harm and suicide attempts, as well as the improvement of negative mood, general psychiatric symptoms, interpersonal problems, and social adjustment.

Conclusions

MBT appears to be a potential treatment of consideration for ASPD in terms of relatively high level of acceptability and promising treatment effects.

Trial registration

ISRCTN ISRCTN27660668 , Retrospectively registered 21 October 2008

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) and antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) are both disorders with high levels of comorbid psychiatric illness. The most frequent comorbid psychiatric disorders in BPD are anxiety and affective disorders, with lifetime prevalence for these at approximately 85 %, followed by substance use disorders at approximately 79 % [ 1 – 4 ]. Co-existence of other psychiatric disorders in BPD has been reported as 41–83 % for major depression, 12–39 % for dysthymia [ 5 ], and 39 % for narcissistic personality disorder [ 6 , 7 ]. Regarding antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), over 90 % of those with the condition have at least one other psychiatric disorder [ 8 ], at least 50 % have co-occurring anxiety disorders [ 9 ] and 25 % have a depressive disorder [ 10 ]. Notwithstanding the varying current views in relation to the classification of categories of personality disorder [ 11 , 12 ], individuals who meet criteria for both ASPD and BPD can be considered as showing a particularly complex and severe form of personality disorder in so far as they are likely to present with particularly high levels of both DSM Axis I and Axis II comorbidity [ 13 ]. Amongst the general (UK) population, the prevalence of individuals meeting both BPD and ASPD diagnostic criteria is low (0.3 %) [ 14 ], but is increased in forensic samples with a higher degree of presumed dangerousness; it has been found to be significantly associated with a greater degree of violence [ 15 , 16 ].

There is sufficient overlap between ASPD and BPD that considering them as separate disorder entities may seem unwarranted [ 11 ]. Yet, while future classifications may do away with the distinction [ 17 ], or at least substantially modify it (as implied by Section III of DSM-5), current nosology incorporates the difference notwithstanding similarities in symptomatology [ 18 ] and trait domains (namely, antagonism and disinhibition) [ 19 ]. In particular, crossover includes marked impulsivity and unpredictability, difficulties with emotional regulation and controlling anger, disregard for safety of self, and behaviour that can be considered by others to appear manipulative (for those with BPD, such behaviour is conducted with the intention of eliciting care and concern from others; for those with ASPD, such behaviour is conducted with the intention of gaining personal profit and power over others) [ 20 – 22 ]. Nonetheless, it is easy to see why the two disorders may be considered as distinctly different from each other. The key, frequently-noted differences include the following: those diagnosed with ASPD tend to have an inflated self-image, whilst those diagnosed with BPD tend to have a negative and devalued self-image; those diagnosed with ASPD pose more of a risk to others due to their tendency towards interpersonal violence, whilst those diagnosed with BPD pose more of a risk to themselves due to their tendency to self-damaging and self-destructive behaviours; those diagnosed with ASPD tend to lack empathy and be indifferent to or contemptuous of the feelings and sufferings of others, whilst those diagnosed with BPD are likely to display reduced cognitive empathy but enhanced affective empathy (the so-called “borderline empathy paradox”) [ 23 ]. In reality, although the prototypic presentations of the two diagnoses appear to be at variance and may be almost polar opposites, the prominent symptoms appear across diagnostic groups as well as varying across time—both within and between individuals. A recent study of nearly 1,000 inpatients found a general personality disorder factor that underlies all personality disorder diagnoses [ 18 ]. Bi-factor analyses of the DSM personality disorder criteria indicated that they load on to a general factor that includes all the BPD criteria, rather than the latter representing a separate personality disorder category. It appears that BPD might be better understood as being at the core of personality pathology more generally, rather than as a type of personality disorder. This approach helps to make sense of the high levels of comorbidity with other personality disorders, including ASPD, found in BPD patients.

In line with this assumption, we suggest that there may be a common element of failures in social cognition associated with both personality disorders [ 24 ]; in particular they share deficits and distortions of mentalization (the process of making sense of the self and of others in terms of mental states—e.g. beliefs, thoughts, feelings, desires). It appears that those with BPD tend to mentalize ‘normally’ except in the context of attachment relationships, in which emotional arousal occludes the ability to accurately interpret mind states (both their own minds and those of others)—particularly when the fear of real or imagined abandonment arises. Difficulties with mentalization manifest slightly differently for antisocial individuals, who show a more general and deeper impairment, including deficits in the recognition of basic emotions [ 25 ], and perform far worse than controls on subtle tests of mentalizing [ 26 , 27 ]. Deficits in social cognition in general and the capacity to link mental states to behaviour in particular are commonly identified in association with antisocial behaviour [ 28 , 29 ]. Some (but not all [ 30 ]) individuals with ASPD show a blend of perspective-taking problems and difficulty in reading others’ mental states [ 31 – 37 ]; this is consistent with the mentalization literature’s deficit theory as well as other theories of antisocial behaviour [ 38 , 39 ]. It has been suggested that one pathway to adult antisocial personality leads from early child conduct disorder via alcohol abuse in early adolescence to compromised function (and maturational delay) of the cognitive control system, of which mentalization is a part [ 40 , 41 ], and which matures throughout adolescence and into early adulthood. Hence, deficits in the ability to mentalize could reflect compromised (i.e. delayed) development of the cognitive control system, brought about by early substance misuse.

Mentalization-Based Treatment—a manualised psychotherapeutic intervention which specifically focuses on improving the capacity to mentalize—has been shown to be effective for improving clinically significant and self-reported outcomes for patients with BPD, including reducing frequency of suicide, severe self-harm, and hospital admission as well as improving general symptomatology and social and interpersonal functioning [ 42 ]. While the presence of comorbid Axis II diagnoses appears to have a negative impact on outcomes for BPD patients undergoing standard clinical management, there has been preliminary work to suggest that MBT may be more beneficial for patients whose BPD is embedded in other Axis II personality disturbances, including that of ASPD [ 43 ]. The authors propose that the mentalization model can also be applied to ASPD and that MBT may be effective for addressing symptoms of ASPD as well as of BPD.

The mentalization model of antisocial behaviour is developmental, premised on the dysfunction of the attachment system that then temporarily inhibits affect regulation and mentalizing abilities [ 44 – 47 ]. Antisocial behaviour and violence tend to occur when an understanding of others’ mental states is developmentally compromised (fragile) and prone to being lost when the attachment system is activated by perceived threats to self-esteem, such as interpersonal rejection or disrespect [ 48 ]. Normally, mentalizing (i.e. envisioning the subjective state of the victim) precludes violence [ 49 ]; this means that individuals with vulnerable mentalizing capacities can be behaviourally volatile in moments of interpersonal stress. Supporting the capacity to identify others’ emotions and intentions may not only assist social functioning but also reduce the risk of antisocial behaviour. Indeed, mentalizing has been shown to be a protective factor against aggression in people with violent traits [ 32 ], encouraging mentalizing has also been shown to reduce school violence [ 50 , 51 ], and studies of forensic patients with personality disorder have found that participants’ views of the processes by which therapeutic change occurred identified realisations that reflected improved mentalizing [ 52 , 53 ].

This study tests the hypothesis that patients with comorbid BPD and ASPD receiving outpatient MBT would be more likely to show improvements in symptoms related to aggression than those offered an outpatient structured protocol of similar intensity but excluding MBT components. This comorbid population was selected for pragmatic reasons, as a subsample of a trial originally designed to compare MBT to Structured Clinical Management (SCM) in a sample of consecutive referrals to a personality disorder unit that specialises in BPD [ 49 ]. At the time of the original trial, MBT had not yet been indicated for ASPD and the trial was not designed with this diagnosis in mind. Nevertheless, our original design allows us to measure change in important psychological features directly related to characteristics of ASPD such as anger, hostility, impulsivity (as reflected in self-harm and suicide) and difficulty in relaxing interpersonal control related to loss of dignity, self-worth and self-respect [ 54 ]. Mood disorders, particularly anxiety and depression, are known to co-occur with ASPD [ 9 , 55 , 56 ] and to be frequent triggers for aggression [ 57 , 58 ]. The trial design also enabled us to test whether MBT may be effective in reducing negative affect states, particularly depression and anxiety. Finally, the study design enabled us to measure change due to treatment in common consequences of aggression, such as psychiatric symptoms including quality of familial and social relationships, and subjective wellbeing.

This subgroup analysis was part of a larger pragmatic randomised superiority trial that investigated MBT as a treatment for patients with BPD in an outpatient context by non-specialist mental health practitioners at a publicly funded clinical service [ 42 ]. To control for the non-specific benefits of a structured treatment, the comparison group also received a protocol-driven therapy, SCM, in an outpatient context representing best current clinical practice [ 59 ]. Practitioners in both arms received the same level of training and equivalent supervision.

Participants

Participants were recruited from consecutive referrals for personality disorder treatment from clinical services between January 2003 and February 2006. All participants were assessed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I and SCID-II) [ 60 , 61 ]. Inclusion criteria were (1) diagnosis of ASPD and comorbid BPD; (2) suicide attempt or episode of life-threatening self-harm within the past 6 months; and (3) age 18–65. Exclusion criteria were kept to a minimum. Patients were excluded if they currently (1) were in long-term psychotherapeutic treatment; (2) met DSM-IV criteria for psychotic disorder or bipolar I disorder; (3) had opiate dependence requiring specialist treatment; or (4) had mental impairment or evidence of organic brain disorder. Current psychiatric inpatient treatment, temporary residence, drug/alcohol misuse and comorbid personality disorder were not exclusion criteria.

One hundred and fifty-eight patients attended for interview. Of these, five did not have BPD, 94 did not have ASPD, two had opiate dependence, one had bipolar I disorder, one had a psychotic disorder, and three could not be contacted after the diagnostic interview. Of the 52 patients enrolled, 12 refused randomisation, leaving 40 with a dual diagnosis of ASPD and BPD, who were randomised to one of the two outpatient treatment programmes (MBT = 21, SCM = 19). Seventy-five percent of the MBT group were male, with a mean age of 31.50 (SD = 8.20) years; 8 % were employed and 76 % were receiving welfare benefits at the time. They had a mean number of 3.1 (SD = 1.3) Axis I and 3.3 (SD = 0.9) Axis II diagnoses. Of the SCM group, 62 % were males, with a mean age of 30.00 (SD = 7.10) years; 6 % were employed and 94 % were receiving benefits. They had a mean number of 3.0 (SD = 1.5) Axis I and 2.9 (SD = 1.0) Axis II diagnoses. None of the participants had ever been married 1 . We tested the relative severity of the groups in terms of the number of Axis I and II diagnoses and found no differences on the Kruskal-Wallis test on either of these variables (χ 2 = 0.05, df = 1, p = .84, and χ 2 = 0.66, df = 1, p = .41 for number of Axis I and Axis II diagnoses respectively).

Patients referred to St Ann’s Hospital’s specialist personality disorder service were randomly assigned to one of two active treatment arms and assessed at entry and over the course of an 18-month treatment at 6, 12, and 18 months. The study was approved by Barnet, Enfield and Haringey Local Research and Ethics Committee (ref: 658) and conducted at the Halliwick personality disorder service and in a community outpatient facility. Patients were provided with written information and consented only after complete description of the study. Randomisation followed consent, enrolment, and baseline assessment by a research assistant at St Ann’s Hospital. Treatment allocation was made offsite via telephone randomisation using a stochastic minimisation program (MINIM) balancing for age (blocked as 18–25, 26–30, >30 years), gender, and presence of ASPD. A study psychiatrist informed patients of their allocation. All treatments were funded by the NHS. Participants were not paid.

Both treatments were conducted within a structured framework following principles outlined elsewhere [ 62 ] and summarised in NICE guidance for BPD [ 21 ]. This included crisis contact and crisis plans, pharmacotherapy, general psychiatric review, and written information about treatment. Crisis plans were developed collaboratively within each treatment team for all patients. MBT therapists focused on helping patients reinstate mentalizing during a crisis via telephone contact. SCM therapists focused on support and problem solving. Efforts were made to keep all patients in treatment if they missed appointments. Both therapies were offered weekly to ensure equivalent therapeutic intensity in both groups. All patients were offered approximately 140 sessions of therapy in total. Seventy-five percent across the two groups met criteria for completers - at least 70 sessions attended over the first year. There was no difference in the distribution of completer categories across the groups (χ 2 = 1.87, df = 2, p = .18). We also tested the amount of treatment received by each group in terms of individual, group and total sessions and there were no differences on the Kruskall-Wallis test on any of these variables (χ 2 = 0.86, df = 1, p = .38, χ 2 = 1.51, df = 1, p = .22, χ 2 = 1.80, df = 1, p = .17 for individual, group and total sessions respectively).

Mentalization-based treatment

MBT is a manualised, structured treatment that integrates cognitive, psychodynamic and relational components of therapy, with a basis in attachment theory and a rigorous focus on improving mentalizing (the ability to understand the mental states of oneself and others). It consisted of 18 months of weekly combined individual and group psychotherapy provided by two different therapists [ 63 ].

Structured clinical management

An outpatient SCM protocol was developed through the Barnet, Enfield and Haringey Mental Health NHS Trust to reflect best generic practice for personality disorder offered by non-specialist practitioners within UK psychiatric services. Weekly individual and group sessions were offered, with appointments every 3 months for psychiatric review. Therapy was based on a counselling model closest to a supportive approach with case management, advocacy support, and problem-oriented psychotherapeutic interventions; the treatment model has been manualised [ 59 ].

Patients were prescribed medication by a member of the treatment team (MBT condition) or their consultant psychiatrist (SCM condition). All patients were offered medication reviews every 3 months. All prescribers were asked to adhere to APA guidelines [ 64 ]. Prescribing patterns and dosage were monitored by review of medical records every 6 months.

Outcomes were classified according to their relation to aggression. Anger, domineering relationships, hostility, paranoid ideation and signs of impulsivity (suicidality and self-harm) were the target outcomes as indicators of problematic aggression. Anxiety, depression, and a summary indicator of psychiatric symptomatic distress were assessed as possible drivers of overt aggression. Lastly, we addressed consequences secondary to problematic aggression: problems in interpersonal relationships, social, familial and global functioning.

Clinician-rated anger was assessed at the beginning and end of treatment by assessors blind to treatment group using SCID-II questions related to item 4 (‘irritability and aggressiveness as indicated by repeated physical fights and assaults’) of the diagnostic criteria for ASPD. Patients’ subjective experience of hostility, paranoid ideation and general symptom distress was measured using the Symptom Checklist-90—Revised (SCL-90-R) [ 65 ], and depression was assessed by using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [ 66 ]. The hostility subscale of the SCL-90 consists of 6 items (items 11, 24, 63, 67, 74, 81) measuring feelings of annoyance and irritability and urges to hurt others as well as actions such as breaking things, getting into arguments, and shouting at others or throwing things. The paranoid ideation subscale is also 6 items, identifying feelings that others are to blame and unappreciative along with a general sense of distrust in others and the world. Self-harm and suicidality were assessed at interview and confirmed from medical records. Social adjustment and interpersonal functioning were measured using the modified Social Adjustment Scale (SAS)–self-report [ 67 ], and the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP)–circumplex version [ 68 , 69 ], which provided a scale of domineering as well as general interpersonal problems. The instruments provide an assessment of an individual’s work, spare time activities, and family life, as well as difficulties with interpersonal functioning. Hospital admission statistics were based on local computerised medical records. Global functioning was rated at the beginning and end of treatment using the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), which has been found to show less improvement than diagnostic symptoms in studies of a naturalistic follow-on design [ 70 ]. Assessors were blind to treatment group, and their assessment was compared with clinician ratings to indicate reliability.

Analysis plan

Treatment group differences were assessed with t tests for independent samples. Change in continuous variables was analysed with mixed effects linear regressions as function of group treatment and time. Incidence of suicidal and severe self-injurious behaviours and episodes of hospitali s ation, assessed in 6-month periods both in terms of counts and as dichotomous data (present or absent in each period), was used to indicate the severity of life-threatening parasuicidal behaviour taken at baseline for the 6 months prior to treatment and for each 6-month period until the end of treatment at 18 months. Count data were analysed using a mixed effects Poisson regression model; for binary data a mixed effects logistic regression model was used.

Target symptoms

Table 1 shows means and standard deviations of anger, domineering interpersonal style as measured by the IIP, and hostility as assessed on the SCL-90 at all time points. Anger, measured by the presence of anger-related criteria on the SCID-II ASPD module, was collected at baseline and at the end of the 18 months of treatment. Both the MBT and SCM groups presented with similar levels of anger at the beginning of treatment, but differed significantly by 18 months ( t = 2.05, p < 0.05). Mixed effects regression revealed significant difference in the linear change observed. Neither the SCM nor the MBT group showed significant changes in domineering interpersonal style as measured by the IIP. Self-rated hostility, however, decreased in both groups. While linear decline was not statistically significantly steeper, both observed and model-predicted hostility was significantly lower in the MBT than the SCM group. Paranoia symptoms, measured by the SCL-90, and paranoid ideation, measured by the SCID-II, showed significantly more improvement in the MBT than the SCM group, and at 18 months, paranoia and paranoid ideation scores were significantly lower.

Changes in anger (SCID-II), domineering interpersonal problems (IIP), Hostility (SCL-90) and paranoia (DSM and SCL-90)

MBT Mentalization-Based Treatment, SCM Structured Clinical Management, t t -test for independent samples, χ 2 chi-squared, CI confidence interval, df degrees of freedom

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

a fixed-effects linear regression

b mixed-effects linear regression with random intercept

c mixed-effects linear regression with random intercept

d mixed-effects linear regression with random slope

Occurrence of suicide attempts, episodes of self-harm and hospital admissions during the last 6 months were registered and counted, and summary scores are displayed in Table 2 . A composite variable was created to count the number of patients free of any of these three severe clinical events in the last 6 months. Mixed effects logistic regression with random intercept confirm the significant observed end of treatment group differences (62 % vs 21 %). Although the number of patients attempting suicide was not significantly different in the logistic regression model, the number of suicide attempts modelled using mixed effects Poisson regression suggested significant superiority of MBT over SCM. For self-harm, both the mean number of self-harm attempts and the number of those who self-harmed suggested greater benefit for participants in the MBT group. Similarly, numbers of hospital admissions were lower in this group. At 18 months, both model-estimated (intention-to-treat) and observed (per protocol) self-harm frequency were significantly lower for the MBT group. Model-estimated (mixed-effects Poisson) frequency of hospital admissions was slightly lower for the MBT group at 18 months.

Changes in impulsive acts (suicidality and self-harm)

MBT Mentalization-Based Treatment, SCM Structured Clinical Management, t t -test for independent samples, χ 2 chi-squared, CI confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom

a mixed-effects logistic regression with random intercept

b mixed-effects Poisson regression with random intercept

Drivers of aggression

Anxiety and depression, as measured by the SCL-90 and the BDI, were both seen to improve significantly across both groups during treatment, following a linear pattern for depression, and both a linear and a quadratic pattern for anxiety, suggesting a fast reduction in anxiety during the first months of treatment. Table 3 shows the observed means for these two scores ordered by treatment group and follow-up time point. At the 18-month point, both anxiety and depression scores (observed and predicted by mixed-effects models) were significantly lower for the MBT group than for the SCM group. The combined symptom distress scores (Global Severity Index; GSI) similarly suggested greater ultimate benefit from MBT, although the mixed effects regression did not indicate significantly more rapid (steeper linear change) improvement.

Changes in mood (anxiety and depression) and general symptom distress (GSI)

a mixed-effects linear regression with random intercept

b mixed-effects linear regression with random slope

Secondary consequences of aggression

As indicated in Table 4 , patients showed comparable total scores on the GAF, IIP and SAS measures at baseline. Mixed-effect models showed a significantly greater linear improvement with time on GAF, and greater linear reduction on IIP and SAS adjustment problems for the MBT group, although both groups improved substantially. However, patients who received MBT showed significantly more improvements on overall functioning, interpersonal problems, and social adjustment scores at the end of treatment, in comparison to patients who received SCM.

Changes in global functioning (GAF), problems in interpersonal relationships (IIP) and social adjustment (SAS)

MBT Mentalization-Based Treatment, SCM Structured Clinical Management, t t -test for independent samples, χ 2 chi-squared, CI confidence interval, df: degrees of freedom

a mixed-effects linear regression with random slope

The aim of the study was to provide preliminary data to indicate whether MBT could reduce symptoms related to antisocial behaviour in patients with comorbid BPD and ASPD when compared with those offered an outpatient structured protocol of similar intensity, but excluding mentalizing components. The data collected is rare in its inclusivity of individuals with comorbid personality disorders, a key clinical group typically excluded from randomised controlled trials, and the results strongly suggest that MBT is an effective treatment for patients with BPD and comorbid ASPD. Patients treated with MBT showed a significantly greater reduction in the target symptoms of anger, hostility and paranoia than those in the SCM group. At the end of treatment, fewer patients in the MBT group presented with impulse control-related problems (suicidality and self-harm), and the frequency of suicide attempts and self-harm episodes was also significantly lower. Measures of negative mood and general psychiatric symptoms, which may identify a vulnerability to the aggressive acts that are a hallmark of ASPD, also showed significantly greater improvements and indicated better adjustment in the MBT group. Similarly, common sequelae of aggression—poor general functioning, interpersonal problems and social adjustment at the end of treatment—were improved following MBT in comparison with those who received SCM.

This study has a number of major limitations. A longer-term follow-up is required to ascertain whether differential effects are maintained; although a 5-year follow-up study is underway, as yet we have no data to report. The study is not adequately powered to demonstrate real differences between the two groups and we recognise that implications of the findings are restricted to the demonstration of feasibility rather than a demonstration of effectiveness [ 71 ]. The lack of specific outcome measures for indications of mentalizing ability (e.g. Reading the Mind in the Eyes Test, Movie for the Assessment of Social Cognition, Perspectives Taking Test, Reflective Functioning Questionnaire, Reflective Functioning Scale on the Adult Attachment Interview) is a major limitation that prevents us from gathering information on MBT’s purported mechanism of change. Additionally, indicators are required that are more central in the planning of services for ASPD than self-reported psychiatric symptoms and mental health diagnostic status after 18 months, including a measure of whether patients continue to meet criteria for formal diagnosis of ASPD. Furthermore, as this comorbid population was selected from a personality disorder unit that specialises in BPD for pragmatic reasons of availability, this study is significantly underpowered and unrepresentative of both the wider ASPD population and the settings in which they most commonly present.

Nevertheless, the results from this study demonstrate that randomisation and effective data collection are possible in a community setting from outpatients with ASPD. Further, we established that patients by and large adhere to the treatment protocol (dropout rates of 27 % for MBT and 26 % for SCM); additionally, qualitatively collected data (reported fully elsewhere [ 72 ]) strongly suggest that this patient group (perhaps surprisingly) value the intervention, and are particularly appreciative of the group format. MBT therefore appears to be a potential treatment of consideration for ASPD in terms of relatively high level of acceptability and promising treatment effects.

In patients with comorbid ASPD and BPD, MBT is able to reduce anger, hostility, paranoia, and frequency of self-harm and suicide attempts, as well as improve negative mood, general psychiatric symptoms, interpersonal problems, and social adjustment. The authors recommend that MBT be further investigated in a significantly powered sample size of patients with a primary diagnosis of ASPD to establish its long-term effects on symptomatology specific to ASPD (e.g. aggression, violence, offending behaviour) as well as outcomes relevant to other Axis I and Axis II disorders (e.g. impulsiveness, social functioning, general wellbeing), whether MBT has an effect on diagnostic continuity for ASPD, and whether any changes can be attributed to change in mentalizing capacity.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Borderline Personality Disorder Research Foundation for providing funding for this research; the therapists who delivered the treatments and the supervisors who oversaw their work; and above all, the patients who gave of their time, often during periods of considerable personal distress, to provide the information without which this paper could not have been written.

The authors wish to thank the Borderline Personality Disorder Research Foundation for providing funding for this research.

Availability of data and materials

Authors’ contributions.

PF and AB conceived, designed and led the research. NL and JOC performed the data cleaning. PF and NL conducted the statistical analyses. NL, JOC, and TG interpreted the data. TG drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

There are no details on individuals reported within this manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Local Research Ethics Committee for Barnet, Enfield, and Haringey Mental Health NHS Trust (ref: 658). Patients were provided with written information and provided consent to participate only after receiving a complete description of the study.

Abbreviations

1 For further demographic and clinical details of the sample please contact the corresponding author.

Contributor Information

Anthony Bateman, Email: [email protected] .

Jennifer O’Connell, Email: [email protected] .

Nicolas Lorenzini, Email: [email protected] .

Tessa Gardner, Email: [email protected] .

Peter Fonagy, Email: [email protected] .

Structured clinical management

Structured clinical management is one of the interventions we offer as part of our complex emotional and relational needs (CERN) pathway. This was established in 2022, as part of wider plans to transform our community mental health teams.

People with complex emotional and relational needs are sometimes referred to as having a personality disorder, but feedback from the people we support is that this term can be negative and unhelpful.

We have a structured clinical management team in each borough, which includes a consultant clinical psychologist and clinical lead, structured clinical management practitioners, and structured clinical management link workers. Some teams also have peer support workers from community groups such as MIND.

We work very closely with a range of services in our local communities, to provide our service users with a joined-up approach to their care.

What is structured clinical management?

Structured clinical management (SCM) is an evidenced based intervention for people who have longstanding difficulties in the below four areas. These difficulties have a significant impact upon people’s lives. Structured clinical management may be helpful for you if you have difficulties with the following:

- Making and keeping healthy relationships

- Managing emotions and mood

- Impulsivity (managing urges to act quickly)

- Self-harm and suicidal thoughts

What can I expect?

Structured clinical management allows a structured process of assessment, socialisation, treatment, and transition to ending. Assessment Initially you'll be invited to complete an assessment with the structured clinical management team. This takes between six and ten weeks to complete.

You'll have weekly one-to-one sessions with your structured clinical management worker to gain an understanding of your difficulties and how they have developed.

You'll be asked to complete some questionnaires about your difficulties and develop an individualised safety plan. You’ll also have the opportunity to discuss if structured clinical management, or another approach, may be helpful to you.

Socialisation Some people may feel ready to engage with the structured clinical management programme, or an alternative option, after completing their assessment.

However, some people may benefit from up to 12 weeks of socialisation. This time will be used to problem solve any difficulties about coming to group sessions or committing to change.

Your structured clinical management worker will work with you to set short- and long-term goals, agree a treatment contract about what to expect and what is expected of you, and develop a more in-depth safety plan to help you during difficult times.

Treatment The treatment involves a combination of weekly group work and individual sessions with your structured clinical management worker. It typically takes about 12 months to complete but can vary.

We will help you to develop skills to address your difficulties and meet your goals by focussing on four key areas:

- Problem solving

- Understanding and managing emotions and mood

- Understanding and managing behaviours that put you at risk

- Understanding and managing relationships.

The treatment phase of structured clinical management requires attendance at both group and individual sessions.

The group work is central to the structured clinical management programme and aims to give you the best opportunities and outcomes from the programme. The group sessions are held on a weekly basis and last for 1 hour and 30 minutes.

Transition to ending Once you have completed the treatment phase, you’ll have a period of one-to-one sessions with your structured clinical management worker.

You’ll use these sessions to jointly review the skills you have developed, plan how you can maintain these in the future and explore the resources and support you’ll need moving forward (e.g. linking it with local community groups and agencies).

If you think you may benefit from structured clinical management, please speak to your care co-ordinator.

Contact information

If you think you may benefit from structured clinical management, please speak to your care co-ordinator.

Opening hours

Referral methods.

Via your care co-ordinator.

Accessibility tools

- Increase text size

- Decrease text size

- Reset text size

- Black and white

- Blue contrast

- Beige contrast

- High contrast

- Reset contrast

Website created by

- Departments and Centers

Main Specialists

- Main Manipulations

- Certificates

- Our Success Stories

Online Consultation

Moscow city clinical hospital after v.m. buyanov.

Solve many of Your questions by using the online consultation service

You can consult with any of the doctors on the areas of healthcare that You are interested in the online consultation format. Our medical specialists have exceptionally high competence and, beyond all doubt, can help You.

Patient Guide

Medical tourism.

Patient action algorithm for getting medical care:

All medical care are provided to foreign citizens on a fee basis (under the Policy of VMI (Voluntary Medical Insurance) or in cash).

Dear Patients! Our experts are ready to offer You a meeting at the airport, transfer, Your accommodation in a hospital as well as accommodation of persons accompanying You.

Patients Testimonials

- I would like to write this review after the successful deviated septum surgery that was performed at the V.M.Buyanov Moscow City Clinical Hospital by Rozhdestvenskaya Olga Nikolaevna. Few days after the surgery I started breathing normally and could get good night sleep breathing through my nose. I couldn't do that for a long time before the surgery. I'd like to thank Rozhdestvensksya Olga and her team for doing such an amazing job. I also had pleasure to share my experience with the head of the hospital Salikov Aleksandr Viktorovich. He politely asked how the surgery went and was very welcoming towards me. Overall I had great experience at the V.M.Buyanov Moscow City Clinical Hospital and highly recommend that place as the first choice for any medical treatments in Moscow.

- I got into that clinic when my heart suddenly fell ill. It turned out that I needed an operation for stenting. I agreed, and the operation was done. I was very pleased, two years ago my problem disappeared.

Batyr Chikmenov Kazakhstan

The Role of Environmental NGOs: Russian Challenges, American Lessons: Proceedings of a Workshop (2001)

Chapter: 14 problems of waste management in the moscow region, problems of waste management in the moscow region.

Department of Natural Resources of the Central Region of Russia

The scientific and technological revolution of the twentieth century has turned the world over, transformed it, and presented humankind with new knowledge and innovative technologies that previously seemed to be fantasies. Man, made in the Creator’s own image, has indeed become in many respects similar to the Creator. Primitive thinking and consumerism as to nature and natural resources seem to be in contrast to this background. Drastic deterioration of the environment has become the other side of the coin that gave the possibility, so pleasant for the average person, to buy practically everything that is needed.

A vivid example of man’s impact as “a geological force” (as Academician V. I. Vernadsky described contemporary mankind) is poisoning of the soil, surface and underground waters, and atmosphere with floods of waste that threaten to sweep over the Earth. Ecosystems of our planet are no longer capable of “digesting” ever-increasing volumes of waste and new synthetic chemicals alien to nature.

One of the most important principles in achieving sustainable development is to limit the appetite of public consumption. A logical corollary of this principle suggests that the notion “waste” or “refuse” should be excluded not only from professional terminology, but also from the minds of people, with “secondary material resources” as a substitute concept for them. In my presentation I would like to dwell on a number of aspects of waste disposal. It is an ecological, economic, and social problem for the Moscow megalopolis in present-day conditions.

PRESENT SITUATION WITH WASTE IN MOSCOW

Tens of thousand of enterprises and research organizations of practically all branches of the economy are amassed over the territory of 100,000 hectares: facilities of energy, chemistry and petrochemistry; metallurgical and machine-building works; and light industrial and food processing plants. Moscow is occupying one of the leading places in the Russian Federation for the level of industrial production. The city is the greatest traffic center and bears a heavy load in a broad spectrum of responsibilities as capital of the State. The burden of technogenesis on the environment of the city of Moscow and the Moscow region is very considerable, and it is caused by all those factors mentioned above. One of the most acute problems is the adverse effect of the huge volumes of industrial and consumer wastes. Industrial waste has a great variety of chemical components.

For the last ten years we witnessed mainly negative trends in industrial production in Moscow due to the economic crisis in the country. In Moscow the largest industrial works came practically to a standstill, and production of manufactured goods declined sharply. At the same time, a comparative analysis in 1998–99 of the indexes of goods and services output and of resource potential showed that the coefficient of the practical use of natural resources per unit of product, which had been by all means rather low in previous years, proceeded gradually to decrease further. At present we have only 25 percent of the industrial output that we had in 1990, but the volume of water intake remains at the same level. Fuel consumption has come down only by 18 percent, and the amassed production waste diminished by only 50 percent. These figures indicate the growing indexes of resource consumption and increases in wastes from industrial production.

Every year about 13 million tons of different kinds of waste are accumulated in Moscow: 42 percent from water preparation and sewage treatment, 25 percent from industry, 13 percent from the construction sector, and 20 percent from the municipal economy.

The main problem of waste management in Moscow city comes from the existing situation whereby a number of sites for recycling and disposal of certain types of industrial waste and facilities for storage of inert industrial and building wastes are situated outside the city in Moscow Region, which is subject to other laws of the Russian Federation. Management of inert industrial and building wastes, which make up the largest part of the general volume of wastes and of solid domestic wastes (SDW), simply means in everyday practice their disposal at 46 sites (polygons) in Moscow Region and at 200 disposal locations that are completely unsuitable from the ecological point of view.

The volume of recycled waste is less than 10–15 percent of the volume that is needed. Only 8 percent of solid domestic refuse is destroyed (by incineration). If we group industrial waste according to risk factor classes, refuse that is not

dangerous makes up 80 percent of the total volume, 4th class low-hazard wastes 14 percent, and 1st-3rd classes of dangerous wastes amount to 3.5 percent. The largest part of the waste is not dangerous—up to 32 percent. Construction refuse, iron and steel scrap, and non-ferrous metal scrap are 15 percent. Paper is 12 percent, and scrap lumber is 4 percent. Metal scrap under the 4th class of risk factor makes up 37 percent; wood, paper, and polymers more than 8 percent; and all-rubber scrap 15 percent. So, most refuse can be successfully recycled and brought back into manufacturing.

This is related to SDW too. The morphological composition of SDW in Moscow is characterized by a high proportion of utilizable waste: 37.6 percent in paper refuse, 35.2 percent in food waste, 10 percent in polymeric materials, 7 percent in glass scrap, and about 5 percent in iron, steel, and non-ferrous metal scrap. The paper portion in commercial wastes amounts to 70 percent of the SDW volume.

A number of programs initiated by the Government of Moscow are underway for the collection and utilization of refuse and for neutralization of industrial and domestic waste. A waste-recycling industry is being developed in the city of Moscow, mostly for manufacturing recycled products and goods. One of the most important ecological problems is the establishment in the region of ecologically safe facilities for the disposal of dangerous wastes of 1st and 2nd class risk factors.

Pre-planned industrial capacities for thermal neutralization of SDW will be able to take 30 percent of domestic waste and dangerous industrial waste. Construction of rubbish-burning works according to the old traditional approach is not worthwhile and should come to an end. Waste-handling stations have been under construction in the city for the last five years. In two years there will be six such stations which will make it possible to reduce the number of garbage trucks from 1,156 to 379 and to reduce the amount of atmospheric pollution they produce. In addition the switch to building stations with capacity of briquetting one ton of waste into a cubic meter will decrease the burden on waste disposal sites and prolong their life span by 4–5 fold. Trash hauling enterprises will also make profit because of lower transportation costs.

Putting into operation waste-segregation complexes (10–12 sites) would reduce volumes of refuse to disposal sites by 40 percent—that is 1,200,000 tons per year. The total volume of burned or recycled SDW would reach 2,770,000 tons a year. A total of 210,000 tons of waste per year would be buried. So, in the course of a five year period, full industrial recycling of SDW could be achieved in practice.

Collection of segregated waste is one of the important elements in effective disposal and utilization of SDW. It facilitates recycling of waste and return of secondary material into the manufacturing process. Future trends in segregation and collection of SDW will demand wide popularization and improvement of the ecological culture and everyday behavior of people.

In recent years the high increase in the number of cars in Moscow has brought about not only higher pollution of the atmosphere, but also an avalanche-like accumulation of refuse from vehicles. Besides littering residential and recreation areas, cars represent a source for toxic pollution of land and reservoirs. At the same time, automobile wastes are a good source for recycled products. In the short-term outlook, Moscow has to resolve the problem of collection and utilization of decommissioned vehicles and automobile wastes with particular emphasis on activities of the private sector. Setting up a system for collection and utilization of bulky domestic waste and electronic equipment refuse is also on the priority list.

In 1999 in Moscow the following volumes of secondary raw materials were produced or used in the city or were recycled: 300,000 tons of construction waste, 296,000 tons of metal scrap, 265 tons of car battery lead, 21,000 tons of glass, 62,500 tons of paper waste, 4,328 tons of oil-bearing waste, and 306 tons of refuse from galvanizing plants.

Such traditional secondary materials as metal scrap and paper waste are not recycled in Moscow but are shipped to other regions of Russia.

The worldwide practice of sorting and recycling industrial and domestic wastes demands the establishment of an industry for secondary recycling. Otherwise segregation of waste becomes ineffective.

There are restraining factors for the development of an effective system of assorted selection, segregation, and use of secondary raw resources, namely lack of sufficient manufacturing capacities and of suitable technologies for secondary recycling.

The problem of utilization of wastes is closely linked with the problem of modernization and sometimes even demands fundamental restructuring of industries. The practical use of equipment for less energy consumption and a smaller volume of wastes and a transition to the use of alternative raw materials are needed. Large enterprises—the main producers of dangerous wastes—are in a difficult financial situation now, which is an impediment for proceeding along these lines.

Private and medium-size enterprises are becoming gradually aware of the economic profitability in rational use of waste. For example, the firm Satory started as a transportation organization specialized in removal of scrap from demolished buildings and those undergoing reconstruction. It now benefits from recycling of waste, having developed an appropriate technology for the dismantling of buildings with segregation of building waste. So, as it has been already mentioned above, the first task for Moscow is to establish a basis for waste recycling.

HOW TO CHANGE THE SITUATION WITH WASTE

Transition to modern technologies in the utilization of wastes requires either sufficient investments or a considerable increase in repayment for waste on the part of the population. Obviously, these two approaches are not likely to be realized in the near future.

The recovery of one ton of SDW with the use of ecologically acceptable technology requires not less than $70–100.

Given the average per capita income in 1999 and the likely increase up to the year of 2005, in 2005 it will be possible to receive from a citizen not more than $14 per year. This means that the cost of technology should not exceed $40 per ton of recycled waste. Unfortunately, this requirement can fit only unsegregated waste disposal at the polygons (taking into account an increase in transportation costs by the year 2005).

Such being the case, it looks like there is only one acceptable solution for Russia to solve the problem of waste in an up-to-date manner: to introduce trade-in value on packaging and on some manufactured articles.

In recent years domestic waste includes more and more beverage containers. Plastic and glass bottles, aluminium cans, and packs like Tetrapak stockpiled at disposal sites will soon reach the same volumes as in western countries. In Canada, for example, this kind of waste amounts to one-third of all domestic waste.

A characteristic feature of this kind of waste is that the packaging for beverages is extremely durable and expensive. Manufactured from polyethylene terephthalate (PTA) and aluminum, it is sometimes more expensive than the beverage it contains.

What are the ways for solving the problem? Practically all of them are well-known, but most will not work in Russia in present conditions. The first problem relates to collection of segregated waste in the urban sector and in the services sector. A number of reasons make this system unrealistic, specifically in large cities. Sorting of waste at waste-briquetting sites and at polygons is possible. But if we take into account the present cost of secondary resources, this system turns out to be economically unprofitable and cannot be widely introduced.

The introduction of deposits on containers for beverages is at present the most acceptable option for Russia. This system turned out to be most effective in a number of countries that have much in common with Russia. In fact this option is not at all new for us. Surely, all people remember the price of beer or kefir bottles. A system of deposit for glass bottles was in operation in the USSR, and waste sites were free from hundreds of millions of glass bottles and jars. We simply need to reinstate this system at present in the new economic conditions according to new types and modes of packaging. Deposits could be introduced also on glass bottles and jars, PTA and other plastic bottles, aluminium cans, and Tetrapak packing.

Let us investigate several non-ecological aspects of this problem, because the ecological impact of secondary recycling of billions of bottles, cans, and packs is quite obvious.