Research & Reviews: A Journal of Health Professions (rrjoph)

About the journal

Research & Reviews: A Journal of Health Professions [2277-6192(e)] is a peer-reviewed hybrid open access journal of engineering and scientific journals launched in 2018 and focused on the rapid publication of fundamental research papers in all areas concerning various current and forthcoming radical new health professions across the globe and the latest cutting edge advancements in healthcare.

Journal Specification

Editor spotlight.

Meet Editorial Board

Special Issues

About journal

Journal specification….

Last updated: 2022-07-01

WEBSITE DISCLAIMER

The information provided by Journal Library (“Company”, “we”, “our”, “us”) on https://journalslibrary.com/ (the “Site”) is for general informational purposes only. All information on the Site is provided in good faith, however we make no representation or warranty of any kind, express or implied, regarding the accuracy, adequacy, validity, reliability, availability, or completeness of any information on the Site.

UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCE SHALL WE HAVE ANY LIABILITY TO YOU FOR ANY LOSS OR DAMAGE OF ANY KIND INCURRED AS A RESULT OF THE USE OF THE SITE OR RELIANCE ON ANY INFORMATION PROVIDED ON THE SITE. YOUR USE OF THE SITE AND YOUR RELIANCE ON ANY INFORMATION ON THE SITE IS SOLELY AT YOUR OWN RISK.

EXTERNAL LINKS DISCLAIMER

The Site may contain (or you may be sent through the Site) links to other websites or content belonging to or originating from third parties or links to websites and features. Such external links are not investigated, monitored, or checked for accuracy, adequacy, validity, reliability, availability or completeness by us.

WE DO NOT WARRANT, ENDORSE, GUARANTEE, OR ASSUME RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE ACCURACY OR RELIABILITY OF ANY INFORMATION OFFERED BY THIRD-PARTY WEBSITES LINKED THROUGH THE SITE OR ANY WEBSITE OR FEATURE LINKED IN ANY BANNER OR OTHER ADVERTISING. WE WILL NOT BE A PARTY TO OR IN ANY WAY BE RESPONSIBLE FOR MONITORING ANY TRANSACTION BETWEEN YOU AND THIRD-PARTY PROVIDERS OF PRODUCTS OR SERVICES.

PROFESSIONAL DISCLAIMER

The Site can not and does not contain medical advice. The information is provided for general informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Accordingly, before taking any actions based upon such information, we encourage you to consult with the appropriate professionals. We do not provide any kind of medical advice.

Content published on https://journalslibrary.com/ is intended to be used and must be used for informational purposes only. It is very important to do your own analysis before making any decision based on your own personal circumstances. You should take independent medical advice from a professional or independently research and verify any information that you find on our Website and wish to rely upon.

THE USE OR RELIANCE OF ANY INFORMATION CONTAINED ON THIS SITE IS SOLELY AT YOUR OWN RISK.

AFFILIATES DISCLAIMER

The Site may contain links to affiliate websites, and we may receive an affiliate commission for any purchases or actions made by you on the affiliate websites using such links.

TESTIMONIALS DISCLAIMER

The Site may contain testimonials by users of our products and/or services. These testimonials reflect the real-life experiences and opinions of such users. However, the experiences are personal to those particular users, and may not necessarily be representative of all users of our products and/or services. We do not claim, and you should not assume that all users will have the same experiences.

YOUR INDIVIDUAL RESULTS MAY VARY.

The testimonials on the Site are submitted in various forms such as text, audio and/or video, and are reviewed by us before being posted. They appear on the Site verbatim as given by the users, except for the correction of grammar or typing errors. Some testimonials may have been shortened for the sake of brevity, where the full testimonial contained extraneous information not relevant to the general public.

The views and opinions contained in the testimonials belong solely to the individual user and do not reflect our views and opinions.

ERRORS AND OMISSIONS DISCLAIMER

While we have made every attempt to ensure that the information contained in this site has been obtained from reliable sources, Journal Library is not responsible for any errors or omissions or for the results obtained from the use of this information. All information in this site is provided “as is”, with no guarantee of completeness, accuracy, timeliness or of the results obtained from the use of this information, and without warranty of any kind, express or implied, including, but not limited to warranties of performance, merchantability, and fitness for a particular purpose.

In no event will Journal Library, its related partnerships or corporations, or the partners, agents or employees thereof be liable to you or anyone else for any decision made or action taken in reliance on the information in this Site or for any consequential, special or similar damages, even if advised of the possibility of such damages.

GUEST CONTRIBUTORS DISCLAIMER

This Site may include content from guest contributors and any views or opinions expressed in such posts are personal and do not represent those of Journal Library or any of its staff or affiliates unless explicitly stated.

LOGOS AND TRADEMARKS DISCLAIMER

All logos and trademarks of third parties referenced on https://journalslibrary.com/ are the trademarks and logos of their respective owners. Any inclusion of such trademarks or logos does not imply or constitute any approval, endorsement or sponsorship of Journal Library by such owners.

Should you have any feedback, comments, requests for technical support or other inquiries, please contact us by email: [email protected] .

Research & Reviews: A Journal of Health Professions

ISSN: 2277-6192.

Research & Reviews: A Journal of Health Professions (RRJoHP) is an international eJournal focused towards the rapid publication of fundamental research papers on all areas of concerning various current and forthcoming radical new health professions across the globe due to cutting edge advancements in healthcare.

- Research & Reviews: A Journal of Health Professions website (full text articles available online)

- Medicine - Miscellaneous

Identifiers

Linking ISSN (ISSN-L): 2277-6192

URL http://www.stmjournals.com/index.php?journal=RRJoHP

Google https://www.google.com/search?q=ISSN+%222277-6192%22

Bing https://www.bing.com/search?q=ISSN+%222277-6192%22

Yahoo https://search.yahoo.com/search?p=ISSN%20%222277-6192%22

National Library of India http://nationallibraryopac.nvli.in/cgi-bin/koha/opac-search.pl?advsearch=1&idx=ns&q=2277-6192&weight_search=1&do=Search&sort_by=relevance

Resource information

Title proper: Research and reviews: a journal of health professions.

Country: India

Medium: Online

Record information

Last modification date: 29/05/2023

Type of record: Confirmed

ISSN Center responsible of the record: ISSN National Centre for India

downloads requested

Discover all the features of the complete ISSN records

Display mode x.

Labelled view

MARC21 view

UNIMARC view

- STM Journals

- Special Issues

- Conferences

Editorial Board Members

- Reviewers Board Members

- Advisory Panel

- Indexing Bodies

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Advisory Board

- Special Issue Guidelines

- Peer-Review Policy

- Manuscript Submission Guidelines

- Publication Ethics and Virtue

Article Processing Charge

- Editorial Policy

- Advertising Policy

- STM Website and Link Policy

- Distribution and dessemination of Research

- Informed consent Policy

"Connect with colleagues and showcase your academic achievements."

"Unleashing the potential of your words"

"Explore a vast collection of books and broaden your horizons."

"Empower yourself with the knowledge and skills needed to succeed."

"Collaborate with like-minded professionals and share your knowledge."

"Learn from experts and engage with a community of learners."

- ICDR Group of Companies

- Training Programs

Research & Reviews: A Journal of Health Professions

ISSN: 2277-6192

Journal Menu

Journal menu, focus and scope.

About the Journal

Research & Reviews: A Journal of Health Professions [2277-6192(e)] is a peer-reviewed hybrid open access journal of engineering and scientific journals launched in 2018 and focused on the rapid publication of fundamental research papers in all areas concerning various current and forthcoming radical new health professions across the globe and the latest cutting edge advancements in healthcare.

Papers Published

- Audiology: Audiologic/aural rehabilitation; balance and balance disorders; cultural and linguistic diversity; detection, diagnosis, prevention, habilitation, rehabilitation, and monitoring of hearing loss; hearing aids; cochlear implants; hearing assistive technology; hearing disorders; lifespan perspectives on auditory function, speech perception, and tinnitus.

- Cardiovascular technology: Implantable medical devices, hemodynamics, tissue biomechanics, functional imaging, surgical devices, electrophysiology, antiarrhythmic drugs, anticoagulation, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, atrial tachycardia, atrioventricular block, electrocardiography, electrocardiogram, epicardial, heart rhythm disorders.

- Clinical chiropractic: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of mechanical disorder of musculoskeletal system; spine adjustment; chiropractic treatment techniques; electrical muscles stimulations; therapeutic ultrasound; vertebral subluxation, dry needling, mobilisation, physical therapies.

- Clinical laboratory technology: Immunochemistry; toxicology; hematopathology; immunopathology; molecular diagnostics; genetic testing; immunohematology; clinical chemistry; microbiology; clinical pathology; medical genetics; physiology and clinical research; clinical chemistry; transfusion and cell therapy; laboratory informatics, general laboratory medicine, anatomic pathology, urinalysis.

- Health economics: production and supply of health services; demand and utilization of health services; financing of health services; determinants of health, such as investments in health and risky health behaviors; economic consequences of ill health; behavioral models of demanders, suppliers, and other health care agencies; evaluation of policy interventions; economic insights; efficiency and distributional aspects of health policy; health insurance and reimbursement; health economic evaluation; health services research; health policy analysis.

- Healthcare System and Health Policy: Individual and institutional aspects of health care management; the importance of health care in developing countries; consumer health informatics and mobile health; group modeling and facilitation in healthcare; health quality and evaluation; healthcare design science; operations management; precision healthcare and soft OR; technical architecture of health IT; healthcare management in general, both at an operational and strategic level; the organization and structuring of healthcare services; cultural and behavioral issues; questions about ethics and quality of life; human resource issues like training and deployment; patient safety and risk; health disparities modeling; system dynamics; human-computer interaction in the healthcare system.

- Interdisciplinary clinical studies, assessment, and outcomes: Multidisciplinary rehabilitation; biopsychosocial pain rehabilitation; pain management program; interdisciplinary pain rehabilitation program; outcomes domains; data management; trial logistics; design and conduct of trials; statistical methods; the impact of trials on practice and policy; ethics; law and regulation; clinical trial design; management, legal, ethical and regulatory issues; case record form design; data auditing methodologies; clinical or policy impact of all types of the clinical trial; clinical trials/treatment strategies in occupational therapy; clinical trials of drugs; clinical trial management.

- Medical Laboratory Sciences: Biomedical Sciences and Laboratory Medicine; Medical Microbiology; Medical Parasitology; Clinical Chemistry; Haematology; Blood group serology; cytogenetics; exfoliation cytology; medical virology; medical mycology; histopathology; laboratory diagnostic reagents; fabricated laboratory hardware; clinical pathology; urinalysis; transfusion medicine; molecular diagnostics; histology; laboratory administration and management.

- Nutrition and dietetics: dietetic practice; medical nutrition therapy, community, and public health nutrition; food and nutrition service management; dietetic education; Nutrition across the lifespan; nutritional support and assessment; obesity and weight management; principles of nutrition and dietetics, dietary surveys; Nutritional epidemiology; nutrigenomics and molecular nutrition research; cancer diet; clinical nutrition; bioactive dietary components; dietary supplement; nutrients; nutrition therapy; nutritional policies; human and clinical nutrition; immuno-nutrition; endocrine nutrition.

- Occupational therapy: Reliability and validity of clinical instruments used by occupational therapists; assistive technology; community rehabilitation; cultural issues related to occupational therapy practice or education; occupational therapy interventions at the population level; surveys related to occupational therapy practice and education; historical reviews of occupational therapy practice; meta-analysis demonstrating the efficacy of interventions related to occupational therapy; scoping reviews of areas of occupational therapy practice; knowledge translation projects in occupational therapy; professional issues in OT; pilot studies of new approaches to OT practice.

- Osteopathy: principles and practice of osteopathic medicine; basic science research, clinical epidemiology, and social science concerning osteopathy; neuromusculoskeletal medicine; pain management; practice management; medical education; neuromusculoskeletal medicine; osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT); public health and primary care.

- Physician: international medicines, randomized controlled trials, prospective cohort studies, health, and clinical practices; case-control studies; Phase I, phase II, and phase III studies, physiological or pharmacological studies.

- Psychology: addictive behavior, auditory cognitive neuroscience, cognition, cognitive science, comparative psychology, consciousness research, cultural psychology, decision neuroscience, developmental psychology, eating behavior, educational psychology, emotion science, environmental psychology, evolutionary psychology, forensic and legal psychology, gender, sex and sexualities, health psychology, media psychology, movement science, sport psychology, neuropsychology, organizational psychology, pediatric psychology, perception science, performance science, personality, and social psychology, psycho-oncology, psychology of aging, psychology of clinical settings, psychopathology, quantitative psychology and measurement, theoretical and philosophical psychology,

- Radiology and ultrasound technology: Breast imaging, Cardiovascular imaging, Chest radiology, computed tomography, diagnostic imaging, gastrointestinal imaging, head and neck imaging, magnetic resonance imaging, musculoskeletal imaging, nuclear medicine, pediatric imaging, positron emission tomography, radiation oncology, x-ray radiography, echocardiography, sonography, theoretical and experimental aspects of advanced methods and technologies in instrumentation for imaging, doppler measurements, signal processing, pattern recognition, clinical evaluation of new techniques, tissue-parameter measures, mechanism of ultrasound- tissue interactions, transducer technology, calibration and standardization, tissue-mimicking phantoms, elasticity measurement, photoacoustic and acousto-optic technologies, radiation oncology, Elastography, high frequency clinical and pre-clinical imaging, neurosonology, point-of-care ultrasound, public policy, therapeutic ultrasound, Ultrasound education, ultrasound in global health, urologic ultrasound, vascular ultrasound.

- Speech and language therapy: speech production and perception; anatomy and physiology of speech and voice; genetics, biomechanics, and other basic sciences of human communication; chewing and swallowing; speech disorders; voice disorders; development of speech and language; hearing in children; normal language processes; language disorders; disorders of hearing and balance; psychoacoustics; anatomy and physiology of hearing.

- Surgical technology: General Surgery, Ophthalmic Surgery, Transplantation Surgery, Endocrine Surgery, Cardiothoracic Surgery, Obstetric Surgery, Neurosurgery, Plastic Surgery, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Orthopaedic Surgery, Acute Care Surgery, Gynecological Surgery, Urological Surgery, Robotic Surgery, Perioperative Care, Anesthesiology, innovation and development in instrumentation, surgical technological methods, surgical training and performance metrics, surgical simulation, telemedicine, history of surgical innovation and innovators.

WEBSITE DISCLAIMER

Last updated: 2022-06-15

The information provided by STM Journals (“Company”, “we”, “our”, “us”) on https://journals.stmjournals.com / (the “Site”) is for general informational purposes only. All information on the Site is provided in good faith, however, we make no representation or warranty of any kind, express or implied, regarding the accuracy, adequacy, validity, reliability, availability, or completeness of any information on the Site.

UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCE SHALL WE HAVE ANY LIABILITY TO YOU FOR ANY LOSS OR DAMAGE OF ANY KIND INCURRED AS A RESULT OF THE USE OF THE SITE OR RELIANCE ON ANY INFORMATION PROVIDED ON THE SITE. YOUR USE OF THE SITE AND YOUR RELIANCE ON ANY INFORMATION ON THE SITE IS SOLELY AT YOUR OWN RISK.

EXTERNAL LINKS DISCLAIMER

The Site may contain (or you may be sent through the Site) links to other websites or content belonging to or originating from third parties or links to websites and features. Such external links are not investigated, monitored, or checked for accuracy, adequacy, validity, reliability, availability, or completeness by us.

WE DO NOT WARRANT, ENDORSE, GUARANTEE, OR ASSUME RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE ACCURACY OR RELIABILITY OF ANY INFORMATION OFFERED BY THIRD-PARTY WEBSITES LINKED THROUGH THE SITE OR ANY WEBSITE OR FEATURE LINKED IN ANY BANNER OR OTHER ADVERTISING. WE WILL NOT BE A PARTY TO OR IN ANY WAY BE RESPONSIBLE FOR MONITORING ANY TRANSACTION BETWEEN YOU AND THIRD-PARTY PROVIDERS OF PRODUCTS OR SERVICES.

PROFESSIONAL DISCLAIMER

The Site can not and does not contain medical advice. The information is provided for general informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Accordingly, before taking any actions based on such information, we encourage you to consult with the appropriate professionals. We do not provide any kind of medical advice.

Content published on https://journals.stmjournals.com / is intended to be used and must be used for informational purposes only. It is very important to do your analysis before making any decision based on your circumstances. You should take independent medical advice from a professional or independently research and verify any information that you find on our Website and wish to rely upon.

THE USE OR RELIANCE OF ANY INFORMATION CONTAINED ON THIS SITE IS SOLELY AT YOUR OWN RISK.

AFFILIATES DISCLAIMER

The Site may contain links to affiliate websites, and we may receive an affiliate commission for any purchases or actions made by you on the affiliate websites using such links.

TESTIMONIALS DISCLAIMER

The Site may contain testimonials by users of our products and/or services. These testimonials reflect the real-life experiences and opinions of such users. However, the experiences are personal to those particular users, and may not necessarily be representative of all users of our products and/or services. We do not claim, and you should not assume that all users will have the same experiences.

YOUR RESULTS MAY VARY.

The testimonials on the Site are submitted in various forms such as text, audio, and/or video, and are reviewed by us before being posted. They appear on the Site verbatim as given by the users, except for the correction of grammar or typing errors. Some testimonials may have been shortened for the sake of brevity, where the full testimonial contained extraneous information not relevant to the general public.

The views and opinions contained in the testimonials belong solely to the individual user and do not reflect our views and opinions.

ERRORS AND OMISSIONS DISCLAIMER

While we have made every attempt to ensure that the information contained in this site has been obtained from reliable sources, STM Journals is not responsible for any errors or omissions or the results obtained from the use of this information. All information on this site is provided “as is”, with no guarantee of completeness, accuracy, timeliness, or of the results obtained from the use of this information, and without warranty of any kind, express or implied, including, but not limited to warranties of performance, merchantability, and fitness for a particular purpose.

In no event will STM Journals, its related partnerships or corporations, or the partners, agents, or employees thereof be liable to you or anyone else for any decision made or action taken in reliance on the information in this Site or for any consequential, special or similar damages, even if advised of the possibility of such damages.

GUEST CONTRIBUTORS DISCLAIMER

This Site may include content from guest contributors and any views or opinions expressed in such posts are personal and do not represent those of STM Journals or any of its staff or affiliates unless explicitly stated.

LOGOS AND TRADEMARKS DISCLAIMER

All logos and trademarks of third parties referenced on https://journals.stmjournals.com / are the trademarks and logos of their respective owners. Any inclusion of such trademarks or logos does not imply or constitute any approval, endorsement, or sponsorship of STM Journals by such owners.

Should you have any feedback, comments, requests for technical support, or other inquiries, please contact us by email: [email protected] .

Effect of Continuing Professional Development on Health Professionals' Performance and Patient Outcomes: A Scoping Review of Knowledge Syntheses

Affiliations.

- 1 A. Samuel is assistant professor, Department of Medicine and Center for Health Professions Education, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9488-9565 .

- 2 R.M. Cervero is professor, Department of Medicine, and deputy director, Center for Health Professions Education, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland.

- 3 S.J. Durning is professor, Department of Medicine, and director, Center for Health Professions Education, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland.

- 4 L.A. Maggio is associate professor, Department of Medicine, and associate director, Center for Health Professions Education, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland; ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2997-6133 .

- PMID: 33332905

- DOI: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003899

Purpose: Continuing professional development (CPD) programs, which aim to enhance health professionals' practice and improve patient outcomes, are offered to practitioners across the spectrum of health professions through both formal and informal learning activities. Various knowledge syntheses (or reviews) have attempted to summarize the CPD literature; however, these have primarily focused on continuing medical education or formal learning activities. Through this scoping review, the authors seek to answer the question, What is the current landscape of knowledge syntheses focused on the impact of CPD on health professionals' performance, defined as behavior change and/or patient outcomes?

Method: In September 2019, the authors searched PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Scopus, ERIC, and PsycINFO for knowledge syntheses published between 2008 and 2019 that focused on independently practicing health professionals and reported outcomes at Kirkpatrick's level 3 and/or 4.

Results: Of the 7,157 citations retrieved from databases, 63 satisfied the inclusion criteria. Of these 63 syntheses, 38 (60%) included multicomponent approaches, and 29 (46%) incorporated eLearning interventions-either standalone or in combination with other interventions. While a majority of syntheses (n = 42 [67%]) reported outcomes affecting health care practitioners' behavior change and/or patient outcomes, most of the findings reported at Kirkpatrick level 4 were not statistically significant. Ten of the syntheses (16%) mentioned the cost of interventions though this was not their primary focus.

Conclusions: Across health professions, CPD is an umbrella term incorporating formal and informal approaches in a multicomponent approach. eLearning is increasing in popularity but remains an emerging technology. Several of the knowledge syntheses highlighted concerns regarding both the financial and human costs of CPD offerings, and such costs are being increasingly addressed in the CPD literature.

Publication types

- Education, Continuing*

- Patient Outcome Assessment

- Patient Satisfaction

- Professional Competence*

- Professional Practice / standards*

- Quality Improvement*

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Foundations

Conclusions, critical reviews in health professions education research.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Guest Access

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Renate Kahlke , Mark Lee , Kevin W. Eva; Critical Reviews in Health Professions Education Research. J Grad Med Educ 1 April 2023; 15 (2): 180–185. doi: https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-23-00154.1

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Health professions education (HPE) has been framed as a field that is not entirely theoretical or practical, as well as one that is not constrained by the worldviews of a single discipline. 1 As such, HPE scholars often need to synthesize knowledge from diverse disciplines or theoretical perspectives to advance thinking about difficult problems. As a result, critical reviews have a robust and valuable history in HPE. Such reviews are methodologically flexible, which enables scholars to advance understanding of complex issues by appraising theory and evidence from an array of sources, rather than prioritizing systematic reporting of everything written within a single discipline.

Within the taxonomy of literature reviews, 2 critical reviews fall under the broad umbrella of narrative reviews. 3 A key feature that often distinguishes critical reviews from other narrative reviews is that they draw on literature and theory from different domains, which enables investigators to reenvision ways of interpreting a problem. Those domains can include multiple disciplines, such as when the fields of psychology, organizational behavior, and behavioral economics were used to help rethink the role of incentives in recruiting and retaining medical clinician educators. 4 Critical reviews can pertain to a specific theory, such as when conversation analysis theory was used to offer a new perspective on the patient-doctor relationship. 5 Or they can be built around a particular empirical finding, such as when patients' priorities for clinical communication were found to not match assumptions about “good” communication. 6 Authors of critical reviews bring an interpretive lens to bear on knowledge synthesis, either through their methods (by designing their review from a specific orientation or theoretical perspective) or analyses (through the development of a new perspective about the focal problem). Thus, in critical reviews, researchers act as research instruments by using their perspectives to appraise and interpret the literature uncovered, rather than primarily acting to describe or summarize it. For this reason, critical reviews are particularly useful for problems that may require a new way of thinking or that require reviewers to use their unique expertise and judgement to take a stance on the information uncovered and where the field ought to go as a result ( Box ).

Dr. Smith, a program director, has been tasked to develop an interprofessional education (IPE) experience for the residency program. She decides that conducting a literature review would be a savvy way to examine the existing evidence and generate a publication potentially useful to others.

After running a Google search using the term “interprofessional education,” Dr. Smith finds more than 11 million hits. Turning to PubMed and using a general subject search with the same term, she identifies 24 000 matches. Dr. Smith randomly samples a few articles and notes the huge diversity of types and approaches, including randomized trials, qualitative investigations, and critical perspectives.

Dr. Smith notices that many of these reports do not always reflect the realities of working with other health professionals. Her experiences suggest that there are often more differences within a “profession” than between professions: she often experiences greater feelings of commonality with social work and health care aide colleagues than with others in her specialty. Dr. Smith wonders how authors within the IPE literature are defining and distinguishing between “professions” and thinks that siloing may do damage by reinforcing interprofessional differences and hierarchies that do not feel real or necessary.

Dr. Smith has an MBA and wonders if any insights can be gleaned from the business literature, where professional roles are more fluid and less defined. She also recalls an introductory psychology course in which the notion of in-groups and out-groups was used to explain social proclivities. Therefore, Dr. Smith decides to conduct a “critical review” as a way to explore, critique, and expand the IPE literature through efforts to draw insights from other fields and paradigms. Dr. Smith's goal is to help reshape the way IPE researchers and educators think about “professions” in a way that might help the field move beyond some of the barriers that have hampered effective IPE for decades.

An additional distinction is that many forms of narrative review focus on exploring how a relatively defined topic has been addressed within a single literature (eg, burnout in medical education 7 or the learning environments experienced by underrepresented minority medical students). 8 In contrast, critical reviewers most often work across multiple disciplines to explore whether each provides unique explanatory value and if comparison between them generates new insights. As an example, Ilgen et al 9 aimed to “define and elaborate the concept of ‘comfort with uncertainty'… in clinical settings by juxtaposing a variety of frameworks and theories in ways that generate more deliberate ways of thinking about, and researching, this phenomenon.” We argue that HPE research has benefited substantially from such engagement with various lenses, by generating insights into multifaceted problems that are unlikely to have simple solutions. 10

Despite the strength of alignment between critical reviews and the complex problems that drive the HPE field, limited methodological guidance is available, and reporting is highly variable. That state leaves researchers, reviewers, and readers with more questions than answers regarding best practices. 11 To fill this gap, we offer an overview and practical guidance by drawing on existing methodological literature, a scan of recently published critical reviews in HPE journals, and our own experiences reading, writing, and reviewing critical reviews. We began by examining 19 articles that stated a “critical review” methodology and were published within the past 10 years in 4 HPE journals with the highest impact factors: Academic Medicine , Medical Education , Advances in Health Sciences Education , and Medical Teacher . We examined introductions and methods sections to extract and compare authors' stated intents and reported procedures. To offer best practice advice for those reading and conducting critical reviews, we then integrated our findings with the limited methodological literature about critical reviews in HPE and other relevant fields. Modeling the goal of critical reviews, our discussion extends beyond reporting “how others have done it” to offer an argument, grounded in the literature, regarding why certain features or strategies should take precedence. In doing so, we sought to offer best practices on critical review design while maintaining the flexibility needed to tailor these reviews to research questions that do not fit well within more structured methods of knowledge synthesis.

Authors of critical reviews generally adopt a constructivist stance, which acknowledges and capitalizes on their background, expertise, and perspectives. Such is the basis for judgements about the quality and relevance of literature along with how it might be interpreted to build understanding in relation to the focal phenomenon. 12 Thus, critical reviews engage with interpretive qualitative research traditions. The goal is not to create generalizable truth, eliminate bias, or produce perfectly replicable methods; instead, it is to capitalize on the unique outlooks developed by researchers during the review process. Rather than seeking to describe or define “what worked,” the purpose of these reviews is to reconceptualize and question assumptions, which often culminates in a proposal for a new theoretical perspective or model. 2 , 12 , 13

The necessarily loose boundaries around critical reviews that this approach creates can cause frustration because others exploring the same issues in the same way may not draw upon the same literature or replicate a specific search strategy. More than a necessary evil, that is a strength of critical reviews because the review team and their unique interpretations and methodological decisions are considered valuable components of the research process. Thus, critical reviews are not the right review type for those seeking (as authors or readers) a definitive or final solution to a specific problem.

As with all research processes it is important for authors to try to avoid only marshaling evidence that supports their claims while ignoring contradictory data; doing so does not mean one should attempt to include everything to avoid “biased” selection. Instead, critical reviewers must be reflexive 14 and transparent about how research decisions were made. Rather than seeing disagreements among team members with different expertise or perspectives as problematic, differences can be an opportunity to challenge assumptions and ensure that decisions are well thought out. 15 Determining how literature or theories from fields outside HPE may inform the problem under review requires a deep understanding of how the phenomenon of interest has been understood in HPE. Hence, most critical review tasks cannot be turned over to a research assistant with instructions to follow a particular process.

Despite these complexities, critical reviews are indispensable when established theoretical and methodological approaches have come up short. They allow investigators to experiment by creatively and organically exploring what insights can be drawn from the juxtaposition of broad and diverse literature, to reflect on assumptions that have been built into conceptions of the problem, to consider how perspectives might change when adopting different disciplinary lenses, and to enable the development of new ideas that may “unstick” thinking.

In our analysis of recent critical reviews, methods sections varied widely. In fact, about a third included no discernible methods section at all. Nonetheless, we were able to identify several hallmarks of critical review methods that appear to illustrate best practices. We would urge caution with respect to treating these elements as linear because, in our experience and among the reviews we examined, literature search and analysis in critical reviews are most often concurrent and iterative processes.

As noted, critical reviewers take a constructivist stance. While authors of these reviews rarely state an explicit epistemological or theoretical perspective, many draw on methodological tools from other established review types or from general qualitative research to support their process. As a rare example of explicit methodological blending or borrowing, Pedersen et al drew on philosophical hermeneutics to frame the interpretive processes underlying their review on empathy in medical education. 16 We believe that offering an explicit guiding rationale for the study and evidence of efforts made to extend the authors' thinking beyond their original assumptions is more important than using a specific frame. Labels noting a particular epistemological perspective or theory should not take the place of rich descriptions of what was actually done and why. Addressing the assumptions and logic underlying the methodological decisions not only acknowledges the role of the researcher in the development of their data and interpretations, but also offers the reader more information with which to evaluate the adequacy of the arguments.

As with other review methods, reviewers should explicitly state their research questions or study objectives, 17 to provide clarity of purpose and the opportunity to judge alignment between aims and methodological choices. In the case of critical reviews, research questions are more often explorative than definitive; as such, they tend to evolve over the course of the review. 18 Research questions generally focus on integrating new literature from a variety of disciplinary perspectives to develop a new approach, understanding, or framework for thinking about the focal phenomenon or topic. For example, in striving to understand assessment practices common to graduate medical education, Gingerich et al 19 sought to develop a “synthesis of related research domains focused on understanding the source of variance in social judgments,” with the intent to “stimulate different ways of asking questions about the limitations of rater-based assessments prior to negotiating potential solutions.”

Data Generation

Literature searches conducted for a critical review should focus on identifying sources of particular relevance rather than capturing everything that has been written on the subject. This may mean finding seminal articles, such as highly cited literature reviews, that offer trustworthy overviews of the theory, assumptions, and evidence cited by researchers from several disciplines. Unlike other narrative reviewers, critical reviewers often utilize methodological tools that go beyond standard database searches to ensure exposure to unfamiliar terms and literature. Consultation with individuals with relevant content as well as theoretical or methodological expertise not represented on the review team can guide searches and ensure that the most relevant sources and key features of unfamiliar literature are captured. 16 , 20 Hand-searching reference lists and citations can prove vital in finding central texts from other fields.

In the critical reviews we examined, some authors offered no description of their search approach, while others offered exhaustive lists of search terms and databases. We suggest that reporting should offer a sense of how the search strategy was crafted, who and what resources were consulted, and what the search was (and wasn't) intended to achieve. This information can provide readers with evidence of the review's strengths and limitations. However, given that critical reviews are not intended to be exhaustive or comprehensive, the focus should be on whether the authors are likely to have uncovered valuable and insight-provoking information, not whether others can replicate the search; as such, extensive lists of search algorithm information are rarely necessary.

Appraisal and Sampling

Rather than using predefined, clear-cut inclusion and exclusion criteria, critical reviewers generally use their unique expertise and perspectives to appraise articles for inclusion based on their sense of a source's relevance to the research question and the value added by its information. As in all reviews, many resources uncovered will lack relevance or fail to meet rigor expectations, which will allow them to be easily excluded. However, critical reviewers must also make nuanced and individualized judgments to appraise the literature for quality and relevance. In doing so they will often purposively sample a small subset of the richest and/or most relevant articles gathered from their searches. Quality and information value are more important than quantity. The proximate goal is to reflect the literature well, not to stake claim to a comprehensive description, because the ultimate goal is to gain insight into the topic, not offer conclusive evidence of how often or to what magnitude something is likely to occur. For example, among the reviews we examined, authors determined inclusion in their sample based on their assessment of an article's “representativeness” of a particular discourse or approach, 21 trustworthiness of the evidence it provided, 22 , 23 conceptual contribution to the field, 9 relevance to the problem, 20 or potential for shifting discourse. 7 , 20

These abstract and subjective evaluations can be difficult to describe concisely. We suggest that authors of critical reviews should strive to define the criteria for their judgements about inclusion and how or if they were guided by concepts such as saturation 24 , 25 or theoretical sufficiency, 26 as commonly applied in qualitative research. In other words, rigor can be demonstrated by showing that the generation of data (through expert consults, searches, and sampling) and analyses appear to do justice to the literature such that continued exploration offers lessening return. This requires investigators to reach a point where they see redundancies in the articles encountered and be able to generate a cohesive representation of the phenomenon under study. Strategies such as regular discussion among team members with diverse backgrounds and combining multiple search approaches (eg, databases, expert consultation, hand-searches) can support reflexivity, which ensures that the review team challenged their own thinking and that their stated results represent a robust picture of relevant concepts.

Analysis methods for critical reviews can align well with, and borrow from, other qualitative research methodologies. For example, in one study the authors drew on content analysis to structure the development of themes from their data. 27 Other authors used forms of discourse analysis to examine how included articles described the concepts under review, rather than focusing on the primary literature's findings or discussion. 28 , 29 Qualitative analytic approaches have great potential to enhance the rigor of critical reviews by offering structure and focus in a way that is familiar to those conducting the review and their readers. It is important that investigators be thoughtful about selecting analytical methods that are congruent with their objectives and other aspects of their methods. For example, discourse analysis might be more appropriate for examining how included sources discuss the phenomenon, whereas other techniques, such as content or thematic analysis, might be more helpful for focusing on what was discussed.

We agree with Grant and Booth that, regardless of analysis methods, a critical review's “product perhaps most easily identifies it” because critical reviews “typically manifest in a hypothesis or a model, not an answer.” 2 The result should leave the reader with a new way of thinking that is coherent and credible, resonates in their context, and has potential to shift their practice. Given that critical reviews are diverse in focus and scope—which is one of their selling points—we found no specific reporting guidelines. To ensure transparent and credible reporting, we direct investigators to general reporting guidelines for qualitative research, such as the article on standards for reporting qualitative research from O'Brien et al, 30 rather than suggesting reporting guidelines for other review types. The latter tend to focus on exhaustive reporting of search methods, rather than articulating the logic used to guide sampling strategies and analysis. Transparency in reporting is critical as there is no absolute roadmap. 18

The most interesting research questions in HPE, in our opinion, are not “What was done?” or “Does it work?” 31 , 32 but those that instead challenge accepted assumptions about concepts and practices. To better understand the phenomena of interest and, in turn, better direct practice, HPE researchers need to be open to new ways of understanding and thinking. To this end critical reviews offer an invaluable tool for interrogating the boundaries of our approaches and knowledge and for generating novel insights that can yield creative solutions with the potential to shift both research directions and practices.

Recipient(s) will receive an email with a link to 'Critical Reviews in Health Professions Education Research' and will not need an account to access the content.

Subject: Critical Reviews in Health Professions Education Research

(Optional message may have a maximum of 1000 characters.)

Citing articles via

Never miss an issue, get new journal tables of contents sent right to your email inbox.

- Submit an Article

Affiliations

- eISSN 1949-8357

- ISSN 1949-8349

- Privacy Policy

- Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

- Open access

- Published: 30 August 2022

Barriers and facilitators to clinical behaviour change by primary care practitioners: a theory-informed systematic review of reviews using the Theoretical Domains Framework and Behaviour Change Wheel

- Melissa Mather ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9746-0131 1 ,

- Luisa M. Pettigrew 2 , 3 &

- Stefan Navaratnam 4

Systematic Reviews volume 11 , Article number: 180 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

6741 Accesses

10 Citations

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

Understanding the barriers and facilitators to behaviour change by primary care practitioners (PCPs) is vital to inform the design and implementation of successful Behaviour Change Interventions (BCIs), embed evidence-based medicine into routine clinical practice, and improve quality of care and population health outcomes.

A theory-led systematic review of reviews examining barriers and facilitators to clinical behaviour change by PCPs in high-income primary care contexts using PRISMA. Embase, MEDLINE, PsychInfo, HMIC and Cochrane Library were searched. Content and framework analysis was used to map reported barriers and facilitators to the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) and describe emergent themes. Intervention functions and policy categories to change behaviour associated with these domains were identified using the COM-B Model and Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW).

Four thousand three hundred eighty-eight reviews were identified. Nineteen were included. The average quality score was 7.5/11. Reviews infrequently used theory to structure their methods or interpret their findings. Barriers and facilitators most frequently identified as important were principally related to ‘ Knowledge ’, ‘ Environmental context and resources ’ and ‘ Social influences ’ TDF domains. These fall under the ‘Capability’ and ‘Opportunity’ domains of COM-B, and are linked with interventions related to education, training, restriction, environmental restructuring and enablement. From this, three key areas for policy change include guidelines, regulation and legislation. Factors least frequently identified as important were related to ‘Motivation’ and other psychological aspects of ‘Capability’ of COM-B. Based on this, BCW intervention functions of persuasion, incentivisation, coercion and modelling may be perceived as less relevant by PCPs to change behaviour.

Conclusions

PCPs commonly perceive barriers and facilitators to behaviour change related to the ‘Capability’ and ‘Opportunity’ domains of COM-B. PCPs may lack insight into the role that ‘Motivation’ and aspects of psychological ‘Capability’ have in behaviour change and/or that research methods have been inadequate to capture their function. Future research should apply theory-based frameworks and appropriate design methods to explore these factors. With no ‘one size fits all’ intervention, these findings provide general, transferable insights into how to approach changing clinical behaviour by PCPs, based on their own views on the barriers and facilitators to behaviour change.

Systematic review registration

A protocol was submitted to the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine via the Ethics and CARE form submission on 16.4.2020, ref number 21478 (available on request). The project was not registered on PROSPERO.

Peer Review reports

Known as the “second translational gap” [ 1 ], a gap in translation between evidence-based interventions and everyday clinical practice has been shown across different clinical areas and international settings [ 2 , 3 , 4 ], with numerous organisational and individual factors influencing clinical behaviour. Existing literature has shown that there is particularly wide variation in clinical behaviour in the primary care setting, which cannot be explained by case mix and clinical factors alone [ 5 , 6 ]. This variation is of particular concern, as it is widely accepted that primary care is the cornerstone of a strong healthcare system [ 7 ], and stronger primary care systems are generally associated with better and more equitable population health outcomes [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]. With an ageing population and unique evolving challenges faced in primary care, understanding the contextual barriers and facilitators to successful behaviour change by primary care practitioners (PCPs) is vital to inform the design and implementation of successful behaviour change interventions (BCIs), and is likely to offer the greatest potential improvement in quality of care and population health outcomes.

Behaviour change interventions

Changing behaviour of healthcare professionals is not easy, but has been shown to be easier when evidence-based theory informs intervention development [ 12 ]. BCIs aimed at healthcare professionals have traditionally been related to incentivisation schemes, guidelines, educational outreach, audit and feedback, printed materials and reminders [ 13 , 14 ]. These have often emerged from approaches to understanding behaviour change, focused on individual attitude-intention processes [ 15 ] and theories emphasising self-interest [ 16 , 17 ]. However, the impact of these interventions on changing clinicians’ behaviour has been found to variable [ 18 ]. Within the context of primary care, attitude-intention processes may not fully explain (lack of) behaviour change, where PCPs face competing pressures, such as caring for multiple patients with limited time, identifying pathology among undifferentiated symptoms, coping with emotional situations, managing uncertainty and keeping up-to-date with substantial volumes of new evidence. Similarly, theories of self-interest may not fully translate to PCPs. BCIs are often implemented through collective action across teams or based on financial levers [ 19 , 20 , 21 ]; however, the organisational context where PCPs work can vary from a single or group community-based practices with variable payment systems [ 22 ]. Therefore, while other healthcare professionals, patients and carers are likely to offer valuable insights, understanding PCPs’ own perspectives on the barriers and facilitators to behaviour change by PCPs is a vital starting point.

Theoretical Domains Framework and Behaviour Change Wheel

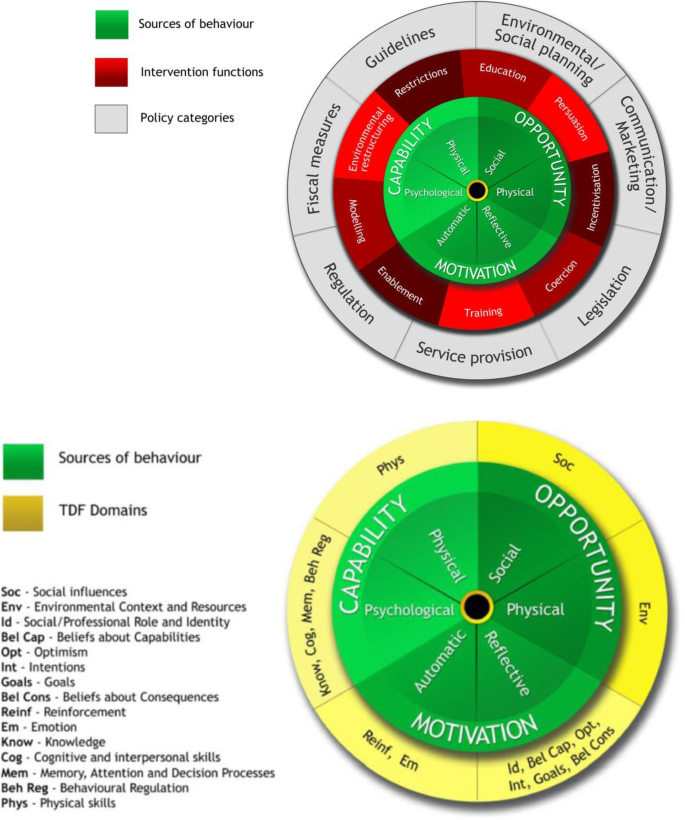

The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) of behaviour change [ 23 ] simplifies and integrates 33 theories and 128 key theoretical constructs related to behaviour change into a single framework for use across multiple disciplines. Theoretical constructs are grouped into 14 domains in the final paper by Michie et al. [ 24 ], encompassing individual, social and environmental factors, with the majority relating to individual motivation and capability factors [ 25 ] (Fig. 1 ). Skills can be subcategorised into cognitive and interpersonal, and physical, although cognitive and inter-personal skills are more relevant to primary care (Table 1 ).

The Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) [ 26 ] (above) and the relationship with the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [ 25 ] (below)

The TDF has been widely used to examine clinical behaviour change in healthcare settings [ 25 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. Key advantages of the TDF include a comprehensive range of domains useful for synthesising large amounts of data [ 24 ] and the domains can be used to identify the types of interventions and policy strategies necessary to change those mechanisms of behaviour, using the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) [ 26 ]. Developed by Michie et al., the BCW can be used to characterise interventions by their “functions” and link these to behavioural targets, categorised in terms of capability (individual capacity to engage in the activity concerned), opportunity (all the factors that lie outside the individual that make the behaviour possible or prompt it) and motivation (brain processes that energize and direct behaviour), known as the COM-B System. Capability encompasses not only individual physical capability, but also psychological capability, defined as the capacity to engage in the necessary thought processes using comprehension, reasoning etc. Strategies to modify behaviour can be identified based on salient TDF and COM-B domains [ 35 ].

The evidence gap

Never having been done before, the aims of this systematic review of reviews were to:

Identify barriers and facilitators to clinical behaviour change by PCPs through the theoretical lenses of the TDF and BCW, from the perspective of PCPs.

Help inform the future development and implementation of theory-led BCIs, to embed EBM into routine clinical practice, improve quality of care and population health outcomes.

A systematic review of reviews was deemed an appropriate method to address these aims, as the literature is substantial and heterogeneous. Existing reviews of reviews have looked at different types of effective BCIs, both in primary care [ 36 , 37 ] and in healthcare in general [ 18 ], however none have looked at barriers and facilitators to PCPs’ behaviour change, using both the TDF and BCW models as a theoretical basis.

We aimed to answer the following questions:

Which TDF domains are most frequently identified as important by PCPs when barriers and facilitators to clinical behaviour change by PCPs are mapped to the TDF framework?

What important themes emerge within these TDF domains?

What intervention functions and policy strategies from the COM-B Model and BCW link to these TDF domains, and what are the implication of this?

Guidance presented in the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual for Evidence Synthesis [ 38 ] was used as methodological guidance to conduct the review, which provides guidance for umbrella reviews synthesising qualitative and quantitative data on topics other than intervention effectiveness. This guidance, alongside a modified version of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [ 39 ], were used for reporting (Additional file 1 ).

A comprehensive database search strategy was devised by MM with assistance from a librarian from LSHTM. The search was conducted by MM on April 16th 2020 without date restriction, using the following databases: Embase (1947 to 2020 April 14), MEDLINE (1946 to April week 1 2020), PsychInfo (1806 to April week 1 2020), Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) (1979 to March 2020) and Cochrane Library (inception to April 2020). The full search strategies are shown in Additional file 2 .

In addition, grey literature was hand-searched by MM on the following websites: Public Health England [ 40 ], the University College London (UCL) Centre for Behaviour Change [ 41 ] and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Evidence Search [ 42 ]. After screening and selection, reference lists of the included reviews were screened for additional relevant reviews.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included, articles had to be reviews of qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods empirical studies examining barriers and facilitators to clinical behaviour change by PCPs. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined using the PICo framework (Population, phenomena of Interest, Context) [ 43 ], to enable transparency and reproducibility. The element of ‘types of studies’ was added to specify types of evidence included (Table 2 ).

In most HIC settings, general practitioners/family doctors are the main providers of primary care, however often included a mix of PCPs (healthcare professionals working in primary care).

PCPs usually provide the mainstay of care in high-income settings. Common barriers and facilitators across a wide range of high-income settings provides stronger evidence for context-specific recommendations.

Types of studies:

The inclusion of all types of reviews (including but not limited to narrative and realist reviews, meta-ethnography and meta-aggregation) allows for a broader review of available literature and they are not bound by the specificity of systematic reviews [ 44 , 45 ].

Only reviews published in English were included.

Screening and selection

Results from database searches were exported to EndNote X9 software and deduplicated. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two reviewers (MM and SN). If the abstract contained insufficient information to determine eligibility, a copy of the full text was obtained. The full texts of articles meeting the inclusion criteria were obtained and reviewed. A standardised form including elements of the PICo framework was used at the full text review stage to identify relevant articles in a consistent way. Articles which could not be accessed online were obtained by contacting authors. Authors were also contacted to obtain clarification where eligibility was unclear. Reference lists of included articles were hand searched by MM and SN to identify additional relevant articles, subject to the same screening and selection processes described.

Quality appraisal

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses [ 38 ] was used for quality appraisal, conducted independently by MM and SN. This tool was applicable to reviews of observational studies, which constituted the majority of the included articles; therefore, all reviews, regardless of their type, were subject to quality appraisal using the JBI checklist. This also allowed for consistency in scoring and easier comparison between the reviews. A scoring system was pre-defined using a small sample of five articles and guidance in the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis [ 38 ]. Some articles fulfilled some but not all of the criteria for each question, which was believed to be reasonable, therefore an additional ‘partial yes’ response was added to reflect this (Additional file 3 ). With a maximum score of 11, scores were used to indicate low (≤ 4 points), moderate (> 4 and < 8 points) and high (≥ 8 points) quality. As outlined by Pope and Mays [ 46 ], the value of specific pieces of qualitative research may only emerge during the synthesis process and may still offer valuable insights despite low quality. No articles were therefore excluded on the basis of low quality scores.

Data extraction

The JBI Data Extraction Form for Reviews of Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses [ 38 ] was adapted to extract relevant data from included reviews. A citation matrix was created to map the included empirical studies of each review and identify duplicate references.

Data analysis and synthesis

Data analysis was conducted independently by MM and SN. Previously reported analysis methods [ 25 , 47 ] were used to guide data analysis and synthesis methods. A combination of content and framework analysis was used, described in five steps:

Data extraction: full-text versions of the included articles were imported into NVivo software and data were extracted from results and discussion sections and supplementary files. Data included barriers, facilitators and factors which could be both barriers and facilitators.

Deductive analysis: extracted barriers, facilitators and factors were mapped to relevant TDF domains using component constructs of each domain, outlined by Cane et al. [ 24 ]. Almost all reported barriers and facilitators related to skills were cognitive and interpersonal, therefore the TDF domain ‘skills: physical’ was removed.

Counts were used to identify the most frequently-reported TDF domains. Owing to the vast amount of information across the included reviews, counts were also used to identify the TDF domains most frequently reported as important by authors. This was done in three ways: where authors explicitly stated they were important or salient, where they were most frequently reported where authors used frequency counts, and where authors highlighted or focused on them in the discussion section to draw main conclusions.

Inductive analysis: thematic analysis was conducted to identify emergent themes within the TDF domains most frequently identified as important to provide context to the role each barrier, facilitator and factor plays in hindering or facilitating clinical behaviour change. Owing to the vast amount of information across the included reviews, themes reported as important or salient by five or more reviews were labelled as important overall.

TDF domains most frequently identified as important were mapped to the COM-B model of the BCW to identify the associated intervention functions and policy categories.

Discrepancies between reviewers at the screening, selection, quality appraisal and analysis stages were discussed until a consensus was reached.

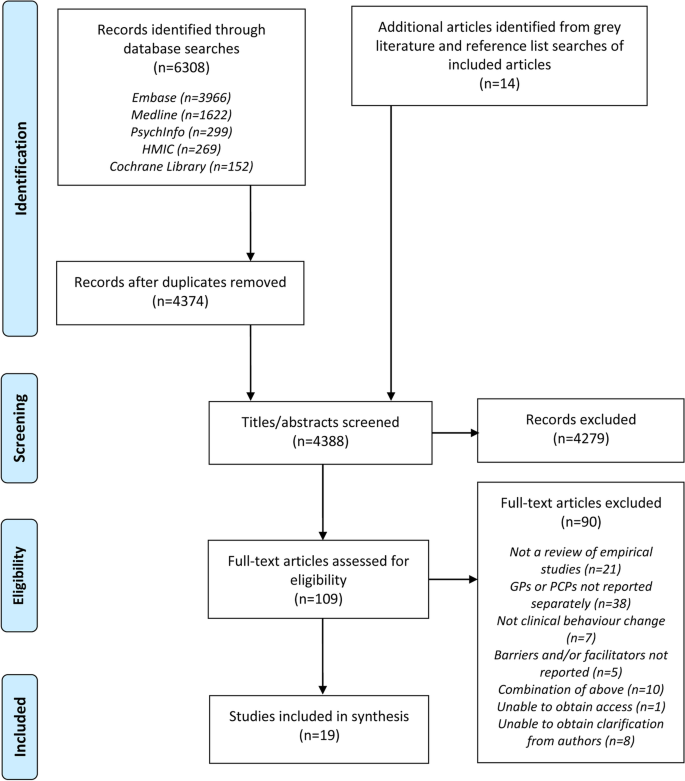

Search results and selection

Database searches identified 6308 records. After duplicates were removed, there were 4374 records remaining. An additional 14 articles were identified from grey literature and reference list searches. The vast majority of these articles were either not a review of empirical studies, or they did not focus on behaviour change. Where they did focus on behaviour change, they focused on patient behaviour change, rather than that of PCPs. One hundred and nine full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Clarification was sought from 19 authors on participant roles, search strategies and synthesis methods, and was obtained from 11 authors. Nineteen reviews [ 33 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 ] were included in the data synthesis (Fig. 2 ).

Flow chart [ 66 ] of review process

Characteristics of included reviews

Of the 19 included reviews, 17 [ 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 64 , 65 ] were systematic reviews and 2 [ 33 , 63 ] were narrative reviews. The reviews were all published between 2005 and 2020. Four hundred and one empirical studies were included in total across a wide range of settings and healthcare systems. Almost all studies were conducted in high-income countries, the majority of which were conducted in Europe, USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Five studies (1%) were conducted in upper-middle-income countries, including Jordan, Turkey, South Africa and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Seven reviews [ 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 65 ] only included qualitative studies, two [ 54 , 55 ] only included quantitative studies, and 10 [ 33 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 ] included qualitative, quantitative and/or mixed methods studies. Most studies were observational, utilising qualitative interviews and/or focus groups, or cross-sectional surveys. A minority of observational studies from six [ 55 , 58 , 59 , 62 , 63 , 64 ] reviews were part of larger intervention studies.

More than 72,000 PCPs were included in total. Seven [ 33 , 48 , 49 , 52 , 55 , 63 , 64 ] reviews only reported general practitioner (GP) or family physician (FP) data and 12 [ 50 , 51 , 53 , 54 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 65 ] reported a mix of PCP data, the majority of which were GPs, FPs, and community paediatrics and obstetrics and gynaecology physicians. Of these, five reviews [ 51 , 56 , 60 , 62 , 65 ] included primary care non-physicians, including nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants. Seven reviews [ 50 , 52 , 53 , 56 , 58 , 61 , 65 ] examined behaviour related to clinical management of a range of topics, of which three specifically examined prescribing behaviour; four reviews [ 33 , 51 , 59 , 63 ] examined diagnostic processes; two [ 49 , 54 ] examined prevention; two [ 55 , 57 ] examined communication and engagement with patients; two [ 48 , 64 ] examined the practice of EBM in general; one [ 62 ] examined collaborative practice; and one [ 60 ] examined service provision. Eighteen studies were referenced by two reviews each due to overlapping phenomena of interest. The most common data synthesis methods were thematic/narrative synthesis and meta-ethnography, used by 13 reviews [ 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 55 , 56 , 58 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 65 ]. Six reviews [ 33 , 54 , 57 , 59 , 63 , 64 ] used framework synthesis; only three reviews [ 33 , 59 , 64 ] used existing theoretical frameworks or models, such as the TDF and COM-B. A summary of review characteristics is shown in Table 3 . Additional information is shown in Additional file 4 .

Quality of empirical studies

Three reviews [ 33 , 55 , 63 ] did not conduct quality appraisal, two of which [ 33 , 63 ] were narrative reviews. The remaining reviews used a wide range of appraisal tools to suit the type of data they included, which were primarily existing tools in their original or adapted forms. Five reviews [ 56 , 57 , 60 , 62 , 64 ] used more than one tool. The most common appraisal tools used were CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) Checklists [ 67 ] for qualitative and quantitative research, used by seven reviews [ 48 , 52 , 53 , 56 , 57 , 59 , 65 ]. There was large variation in how authors used the appraisal tools, therefore quality of studies could not be reliably compared between reviews. Detailed information is shown in Additional file 3 .

Quality of reviews

Ten reviews were of high quality, seven were of moderate-quality and two were of low quality using the JBI checklist. The highest score was 10.5/11 and the lowest was 3/11. The average score was 7.5/11, which is considered moderate quality. Reviews generally included well-evidenced recommendations for policy and practice and appropriate directives for future research. On validity, reviews scored highest on appropriate inclusion criteria for the review question, and appropriate methods used to combine studies. Reviews scored poorly on using an appropriate search strategy and assessing for publication bias. Most reviews did not justify search limits and/or did not provide evidence of a search strategy. Scores for each of the criteria are shown in Additional file 3 .

Main findings

A large number of barriers, facilitators and factors were identified by authors, often interacting with each other in a complex way (Table 4 ). As a result, some barriers and facilitators were mapped to more than one TDF domain. All TDF domains were identified. All reviews identified ‘environmental context and resources’ as important, and all but two reviews identified ‘knowledge’ and ‘social influences’ as important. TDF domains identified least frequently as important were ‘goals’, ‘intentions’ and ‘optimism’. Although ‘social/professional role and identity’, ‘skills’ and ‘emotion’ TDF domains were frequently identified, they were less frequently highlighted as important by authors. Table 4 shows how each TDF domain and COM-B domains were mapped to each of the included reviews, as well as which domains were identified as important.

Forty-two themes were identified in total across all TDF domains, 12 of which were labelled as important overall. A theme was labelled as important overall if five or more reviews identified it as important or salient. Within the ‘Knowledge’, ‘Environmental context and resources’, and ‘Social influences’ TDF domains, nine important themes emerged, of which the most frequently cited as important were ‘knowledge, awareness and uncertainty’ and ‘time, workload and general resources’. Across the remaining TDF domains, other important themes included ‘skills and competence’, ‘roles and responsibilities’, and ‘confidence in own ability’. Additional file 5 shows how themes were mapped to each TDF domain and each review, with corresponding quotes.

Capability: psychological (COM-B domain)

Knowledge (tdf domain).

Knowledge, awareness and uncertainty (theme)

Identified as important by 13 reviews [ 33 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 54 , 55 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 65 ] (average quality score 7.2/11).

Inadequate knowledge and awareness and uncertainty were identified as important barriers to depression diagnosis and management [ 51 , 56 ], recognition of insomnia [ 33 ], antibiotic prescribing in childhood infections [ 50 ] and acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs) [ 65 ], engagement in cancer care [ 58 ], integration of genetics services [ 60 ], discussing smoking cessation [ 55 ], collaborative practice [ 62 ], management of multimorbidity [ 52 ], breast and colorectal screening in older adults [ 54 ] and chlamydia testing [ 59 , 63 ]. This varied from a lack of knowledge of the topic as a whole, to more specific skills or outcomes. For example, PCPs reported a lack of knowledge around the epidemiology and presentation of chlamydia, benefits of testing, how to take specimens, and treatment options [ 59 ]. When prescribing antibiotics for childhood infections and ARTIs, PCPs reported they tend to prescribe “just in case” when they are uncertain of the consequences of not prescribing, such as when the diagnosis is unclear, or where there is no established doctor-patient relationship [ 50 , 65 ]. There was widespread lack of knowledge within the field of genetics, including uncertainty around cancer genetics, genetic testing, genetic discrimination legislation, and local genetics service provision [ 60 ]. As well as a lack of knowledge of national guidelines and strategy [ 60 , 63 ], inadequate guidelines were reported to exacerbate a lack of knowledge. For example, a lack of attention in guidelines on how social problems affect response to depression management was reported to exacerbate PCPs’ uncertainty around their role in managing depression [ 56 ]. Lack of knowledge and uncertainty were frequently reported to cause discomfort, low confidence, and reluctance to fill certain roles.

Opportunity: physical (COM-B domain)

Environmental context and resources (tdf domain).

Time, workload and general resources (theme)

Identified as important by 13 reviews [ 33 , 48 , 50 , 51 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 63 , 64 ] (average quality score 7.3/11).

A lack of time to implement a variety of different tasks and clinical behaviours was reported, compounded by a large and complex workload and lack of general resources. A prominent barrier was time-pressured consultations, where PCPs reported difficulty in ensuring the clinician and parents are satisfied with the outcome when treating childhood infections [ 50 ], offering alternative interventions [ 53 ], listening to patients with depression [ 56 ], discussing emotions in cancer care [ 58 ] or smoking cessation with patients [ 55 ], introducing chlamydia testing and addressing sexual health-related concerns [ 63 ], recognising, diagnosing and managing child and adolescent mental health problems [ 61 ], and negotiating with patients [ 48 ]. PCPs also reported a lack of time to read and assess evidence and guidelines and reflect on their own practice [ 48 , 64 ].

Guidelines, evidence and decision-making tools (theme)

Identified as important by five reviews [ 48 , 52 , 58 , 64 , 65 ] (average quality score 7.8/11).

Guidelines were a common factor reported to affect clinical behaviour, including a lack of guidelines/guidance, questionable evidence-base, and a disjunction between guidelines and personal experience. For example, PCPs reported difficulty in adapting recommendations to individual patient circumstances and practical constraints of the consultation [ 48 , 51 , 52 ]. PCPs felt that some guidelines lack the necessary flexibility when taking patient preferences and multi-morbidity into account, which can add to complexity and even cause harm in some cases [ 52 , 64 ]. PCPs questioned the evidence-base of the guidelines due to low generalisability and narrow inclusion criteria of trials [ 48 , 64 ] and potential biased sources of research, such as pharmaceutical companies [ 64 ]. The validity of criteria used for depression diagnosis was also questioned, with national guideline criteria defining depressive disorders using symptom counts, as opposed to viewing it as a syndrome requiring aetiological and conceptual thinking [ 51 ]. For non-English PCPs, access to evidence and guidelines in their native language was reported as a major barrier to implementing EBM [ 64 ].

Financial resources and insurance coverage (theme)

Identified as important by 6 reviews [ 49 , 54 , 58 , 61 , 62 , 64 ] (average quality score 8/11).

Poor remuneration and increasing costs were common barriers reported in areas such as PCP involvement in cancer care [ 58 ], child and adolescent mental health [ 61 ] and use of EBM [ 64 ]. A major barrier to recognition and management of child and adolescent mental health problems and cancer in older adults was inadequate insurance coverage, including inadequate coverage of screening tests [ 54 ], restrictions on the number of funded therapy visits, and lack of psychiatrists [ 61 ]. As a result, increased reimbursement was identified as a potential facilitator that could increase child and adolescent mental health diagnoses [ 61 ].

Education and training (theme)

Identified as important by five reviews [ 33 , 59 , 63 , 64 , 65 ] (average quality score 5.7/11).

A lack of education and training was highlighted as an important barrier to chlamydia testing [ 59 , 63 ], recognition of insomnia [ 33 ], antibiotic prescribing [ 65 ], and use of EBM [ 64 ]. PCPs reported that undergraduate sexual health teaching is inadequate [ 63 ] and that they have a lack of appropriate training and skills to discuss sexual health, take a sexual history, offer a test, manage treatment and notify partners. This has led to a reduction in knowledge and confidence to offer testing and discuss sexual health [ 59 ]. More education and training for PCPs and undergraduate students was frequently cited as a facilitator, as PCPs felt this would increase knowledge and confidence to change behaviour. Older male PCPs were identified as potentially in need of specific education on sexual health due to cultural differences with some patients receiving chlamydia testing [ 59 ]. Some PCPs reported that trustworthy and knowledgeable educational sources are important for PCPs to feel added value, with peer-led educational meetings given as an example [ 65 ].

Opportunity: social (COM-B domain)

Social influences (tdf domain).

PCP-patient relationship and patient-centred care (theme)

Identified as important by nine reviews [ 48 , 49 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 65 ] (average quality score 8.2/11).

Some PCPs reported that preservation of the PCP-patient relationship is prioritised over adherence to guidelines, particularly if guidelines recommend rationing services, or if PCPs feel empathetic towards anxious patients [ 48 ]. This dilemma was described as unpleasant and against the principles of patient-centred medicine, but sometimes necessary to avoid the potential litigation that rationing might bring [ 48 ] and loss of patients to other practices [ 53 ]. Similarly, the desire to maintain a good relationship is sometimes in competition with the PCP’s rationing role, leading some PCPs to give patients a “quick fix” when prescribing benzodiazepines [ 53 ]. Although not always reported as important, sensitive and emotive areas of medicine appear to be particularly affected, with PCPs reporting a concern for depriving patients of hope and/or damaging the relationship if they engage in the process of ACP [ 57 ], cancer care [ 58 ], or offer chlamydia testing [ 63 ]. Specifically, PCPs worried about appearing discriminatory and judgemental towards patients by offering chlamydia testing [ 63 ], and being too intrusive and paternalistic in recommending behaviour change to patients to prevent CVD [ 49 ]. This appears to be compounded by different religious and cultural norms between the PCP and patient, particularly if patients are of non-heteronormative orientation [ 63 ].

Establishing a rapport with patients and developing a long-standing, trusting doctor-patient relationship was identified as a facilitator for information-sharing, depression diagnosis [ 51 ], multimorbidity management [ 52 ], changing prescribing behaviour of benzodiazepines [ 53 ] and PCP engagement in ACP [ 57 ].

Patient/carer characteristics (theme)