Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and confidence in the Philippines and Malaysia: A cross-sectional study of sociodemographic factors and digital health literacy

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Clinical Informatics Research Unit, Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom

Roles Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Community Medicine, International Medical School, Management and Science University, Shah Alam, Malaysia, Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Asia Metropolitan University, Johor Bahru, Malaysia, Global Public Health, Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Malaysia, Bandar Sunway, Malaysia

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Cyberjaya, Cyberjaya, Malaysia

Roles Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department: School of Criminal Justice Education, Institution: J.H. Cerilles State College, Caridad, Dumingag, Zamboanga del Sur, Philippines

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Global Public Health, Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Malaysia, Bandar Sunway, Malaysia, South East Asia Community Observatory (SEACO), Jeffrey Cheah School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Monash University Malaysia, Bandar Sunway, Malaysia

- Ken Brackstone,

- Roy R. Marzo,

- Rafidah Bahari,

- Michael G. Head,

- Mark E. Patalinghug,

- Published: October 19, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

With the emergence of the highly transmissible Omicron variant, large-scale vaccination coverage is crucial to the national and global pandemic response, especially in populous Southeast Asian countries such as the Philippines and Malaysia where new information is often received digitally. The main aims of this research were to determine levels of hesitancy and confidence in COVID-19 vaccines among general adults in the Philippines and Malaysia, and to identify individual, behavioural, or environmental predictors significantly associated with these outcomes. Data from an internet-based cross-sectional survey of 2558 participants from the Philippines ( N = 1002) and Malaysia ( N = 1556) were analysed. Results showed that Filipino (56.6%) participants exhibited higher COVID-19 hesitancy than Malaysians (22.9%; p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences in ratings of confidence between Filipino (45.9%) and Malaysian (49.2%) participants ( p = 0.105). Predictors associated with vaccine hesitancy among Filipino participants included women (OR, 1.50, 95% CI, 1.03–1.83; p = 0.030) and rural dwellers (OR, 1.44, 95% CI, 1.07–1.94; p = 0.016). Among Malaysian participants, vaccine hesitancy was associated with women (OR, 1.50, 95% CI, 1.14–1.99; p = 0.004), social media use (OR, 11.76, 95% CI, 5.71–24.19; p < 0.001), and online information-seeking behaviours (OR, 2.48, 95% CI, 1.72–3.58; p < 0.001). Predictors associated with vaccine confidence among Filipino participants included subjective social status (OR, 1.13, 95% CI, 1.54–1.22; p < 0.001), whereas vaccine confidence among Malaysian participants was associated with higher education (OR, 1.30, 95% CI, 1.03–1.66; p < 0.028) and negatively associated with rural dwellers (OR, 0.64, 95% CI, 0.47–0.87; p = 0.005) and online information-seeking behaviours (OR, 0.42, 95% CI, 0.31–0.57; p < 0.001). Efforts should focus on creating effective interventions to decrease vaccination hesitancy, increase confidence, and bolster the uptake of COVID-19 vaccination, particularly in light of the Dengvaxia crisis in the Philippines.

Citation: Brackstone K, Marzo RR, Bahari R, Head MG, Patalinghug ME, Su TT (2022) COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and confidence in the Philippines and Malaysia: A cross-sectional study of sociodemographic factors and digital health literacy. PLOS Glob Public Health 2(10): e0000742. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742

Editor: Nnodimele Onuigbo Atulomah, Babcock University, NIGERIA

Received: June 12, 2022; Accepted: September 20, 2022; Published: October 19, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Brackstone et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: Data are available on the OSF repository: https://osf.io/ncwjq/ .

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

While many high-income settings have achieved relatively high coverage with their COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, almost 32.1% of the world’s population have not received a single dose of any COVID-19 vaccine as of July 2022 [ 1 ]. The Philippines and Malaysia are among two of the most populous countries in Southeast Asia with an estimated population of 110 million and 32 million people, respectively. To date, Malaysia has seen over 4.6 million cases with a mortality rate of 0.77%, while approximately 3.7 million cases of COVID-19 were detected in the Philippines with a mortality rate of 1.60% [ 2 ]. Malaysia is doing considerably well with their vaccination efforts, with 84.8% of the population currently considered fully vaccinated as of July 2022. However, vaccination campaigns in the Philippines have been more difficult, with 65.6% of the population fully vaccinated [ 3 ]. With the emergence of the highly transmissible Omicron variant across the world [ 4 ], large-scale vaccination coverage remains fundamental to the national and global pandemic response. Regular scientific assessments of factors that may impede the success of COVID-19 vaccination coverage will be critical as vaccination campaigns continue in these nations.

A key factor for the success of vaccination campaigns is people’s willingness to be vaccinated once doses become accessible to them personally. Vaccine hesitancy is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the delay in the acceptance, or blunt refusal of, vaccines. In fact, vaccine hesitancy was described by the WHO as one of the top 10 threats to global health in 2019 [ 5 ]. Conversely, vaccine confidence relates to individuals’ beliefs that vaccines are effective and safe. In general, a loss of trust in health authorities is a key determinant of vaccine confidence, with misconceptions about vaccine safety being among the most common reasons for low confidence in vaccines [ 6 ].

Previously, vaccination in Southeast Asia has been associated with mistrust and fear, particularly in the Philippines, who are still suffering the consequences of the Dengvaxia (dengue) vaccine controversy in 2017 [ 7 ]. Studies suggest that this highly political mainstream event, in which anti-vaccination campaigns linked dengue vaccines with autism spectrum disorder and with corrupt schemes of pharmaceutical companies, continue to erode the population’s trust in vaccines. For example, a survey conducted on over 30,000 Filipinos in early 2021 showed that 41% of respondents would refuse the COVID-19 vaccine once it became available, whereas Malaysia reported 27% hesitancy [ 8 ]. Researchers predict that the controversy surrounding Dengvaxia may have prompted severe medical mistrust and subsequently weakened the public’s attitudes toward vaccines [ 7 , 9 ]. However, there may be many additional factors that weaken confidence in vaccines. For example, incompatibility with religious beliefs is one key driver of weakened confidence in vaccines [ 10 , 11 ], whereas living in urbanised (vs. rural) areas predicts COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in some countries [ 12 – 14 ], possibly due to being more connected to the internet and social media and being more exposed to COVID-19-related misinformation.

Other predictors of vaccine hesitancy and confidence may include digital health literacy–one’s ability to seek, find, understand, and appraise health information from digital resources–and social media use. Research has shown that beliefs in available information is integral to perceptions of the vaccine safety and effectiveness [ 15 – 17 ]. Previous studies, for example, have associated higher vaccine hesitancy with misinformation about the virus and vaccines, particularly if they relied on social media as a key source of information [ 18 , 19 ]. Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) is a widely accepted theory which may explain individual behaviors, including digital health literacy [ 20 ]. SCT consists of three factors–environmental, personal, and behavioural–and any two of these components interact with each other and influence the third. As such, SCT can assist in establishing a link between one’s behaviour (e.g., information-seeking–one form of digital health literacy) and environmental factors (e.g., availability of information online), which may interact to promote medical mistrust and influence vaccine hesitancy and confidence (personal) [ 21 ]. Thus, health behaviours are often influenced by social systems as well as personal behaviours.

Although vaccine hesitancy and confidence are related concepts (e.g., people who express low confidence in vaccines are more likely to be vaccine-hesitant [ 6 ]), they are also distinct [ 22 ]. Thus, the main aims of this research were to determine levels of hesitancy and confidence in COVID-19 vaccines among general adults in the Philippines and Malaysia, and to identify behavioural or environmental predictors that are significantly associated with both outcomes. Thus, developing a deeper understanding of the factors associated with vaccine hesitancy and confidence will provide insight into how specific population groups may respond to health threats and public health control measures.

Design, subjects, and procedure

This was an internet-based cross-sectional survey conducted from May 2021 to September 2021 in the Philippines and Malaysia. Snowball sampling methods were used for the data collection using social media, including research networks of universities, hospitals, friends, and relatives. Filipino and Malaysian residents aged 18 years or older were invited to take part. The inclusion criteria for participants’ eligibility included 18 years or older, and an understanding of the English language. All invited participants consented to the online survey before completion. Consented participants could only respond to questions once using a single account. The voluntary survey contained a series of questions which assessed sociodemographic variables, social media use, digital literacy skills in health, and attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine.

Ethical approval

The study received ethical approval from Asia Metropolitan University’s Medical Research and Ethics Committee (Ref: AMU/FOM/MREC 0320210018). All participants provided informed consent. All study information was written and provided on the first page of the online questionnaire, and participants indicated consent by selecting the agreement box and proceeding to the survey.

Demographics.

Filipino and Malaysian participants indicated their age category (18–24, 25–34, or 35–44), gender (man, woman), community type (rural, urban), educational level (no formal education, primary, secondary, tertiary), employment (unemployed, part-time, full-time), religion (Christian, Buddhism, Muslim, Hinduism, Other, None), income (1 = very insufficient ; 4 = very sufficient ; M = 1.84, SD = 0.81), whether they were permanently impaired by a health problem (no vs. yes), and whether they were social media users (no vs. yes).

Subjective social status.

Participant then rated their own perceived social status using the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status scale [ 23 ]. Participants viewed a drawing of a ladder with 10 rungs, and read that the ladder represented where people stand in society. They read that the top of the ladder consists of people who are best off, have the most money, highest education, and best jobs, and those at the bottom of the ladder consists of people who are worst off, have the least money, lowest education, and worst or no jobs. Using a validated single-item measure, participants placed an ‘X’ on the rung that best represented where they think they stood on the ladder (1 = lowest ; 10 = highest; M = 6.23, SD = 1.86).

Vaccine confidence and hesitancy.

Participants were also asked about their perceived level of confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine (“I am completely confident that the COVID-19 vaccine is safe,” 1 = strongly disagree ; 7 = strongly agree; M = 4.57, SD = 1.48). Then, participants were asked about their level of hesitancy to the COVID-19 vaccine (“I think everyone should be vaccinated according to the national vaccination schedule”; no, I don’t know, yes). These questions were adapted from the World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe survey [ 24 ]. The tool underwent evaluation by multidisciplinary panel of experts for necessity, clarity, and relevance.

Digital health literacy.

Finally, participants completed the Digital Health Literacy Instrument (DHLI) [ 25 ], which was adapted in the context of the COVID-HL Network. The scale measures one’s ability to seek, find, understand, and appraise health information from digital resources. A total of 12 items (three per each dimension) were asked, and answers were recorded on a four-point Likert scale (1 = very difficult ; 4 = very easy; α = .92; M = 2.15, SD = 0.59). While the original DHLI is comprised of 7 subscales, we used the following four domains, including: (1) information searching or using appropriate strategies to look for information (e.g., “When you search the internet for information on coronavirus virus or related topics, how easy or difficult is it for you to find the exact information you are looking for?”; α = .87; M = 2.15, SD = 0.65), (2) adding self-generated content to online-based platforms (e.g., “When typing a message on a forum or social media such as Facebook or Twitter about the coronavirus a related topic, how easy or difficult is it for you to express your opinion, thought, or feelings in writing?”; α = .74; M = 2.15, SD = 0.65), (3) evaluating reliability of online information (e.g., “When you search the internet for information on the coronavirus or related topics, how easy or difficult is it for you to decide whether the information is reliable or not?”; α = .86; M = 2.20, SD = 0.69), and (4) determining relevance of online information (e.g., “When you search the internet for information on the coronavirus or related topics, how easy or difficult is it for you to use the information you found to make decisions about your health [e.g., protective measures, hygiene regulations, transmission routes, risks and their prevention?”]; α = .87; M = 2.09, SD = 0.68). The reliability statistics for the overall DHL score was 0.92, while the alpha coefficients for the four subscales ranged from 0.74 to 0.87, suggesting acceptable to good internal consistency.

Data analysis

Data were examined for errors, cleaned, and exported into IBM SPSS Statistics 28 for further analysis. All hypotheses were tested at a significance level of 0.05. χ 2 tests were conducted for group differences of categorical variables, and Mann-Whitney tests for continuous variables. Subgroup analyses were performed for Filipino and Malaysian participants.

COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and confidence were treated as separate dependent variables in a logistic regression model providing the strictest test of potential associations with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and confidence among Filipino and Malaysian participants. Low vaccine confidence was operationalised by dichotomising participants’ responses to the statement: “I am completely confident that the COVID-19 vaccine is safe” into those who disagreed or neither agreed nor disagreed (1–4), whereas high vaccine confidence was operationalised by dichotomising participants’ responses into those who agreed to some extent (5–7). Vaccine hesitancy was operationalised by dichotomising responses to the statement: “I think everyone should be vaccinated according to the National vaccination schedule” into those indicating ‘no’ or ‘I don’t know,’ whereas no vaccine hesitancy was operationalized by dichotomising participants’ response into those who indicated ‘yes.’

Independent variables were: age (18–24 vs. 25–34 vs. 35–44 [ref]), gender (women vs. men [ref]), community type (rural vs. urban [ref]), educational level (tertiary vs. secondary or less [ref]), employment (employed to some degree vs. unemployed [ref]), religion (Philippines: Christianity vs. Islam [ref]; Malaysia: Christianity vs. Buddhism vs. Hinduism vs. Islam [ref]), income (low (1–2) vs. high (3–4 [ref])), whether they were permanently impaired by a health problem (yes vs. no [ref]), whether they were social media users [yes vs. no [ref]), their perceived ranking on the MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status (continuous variable), and finally the four domains of the DHLI scale (all continuous variables).

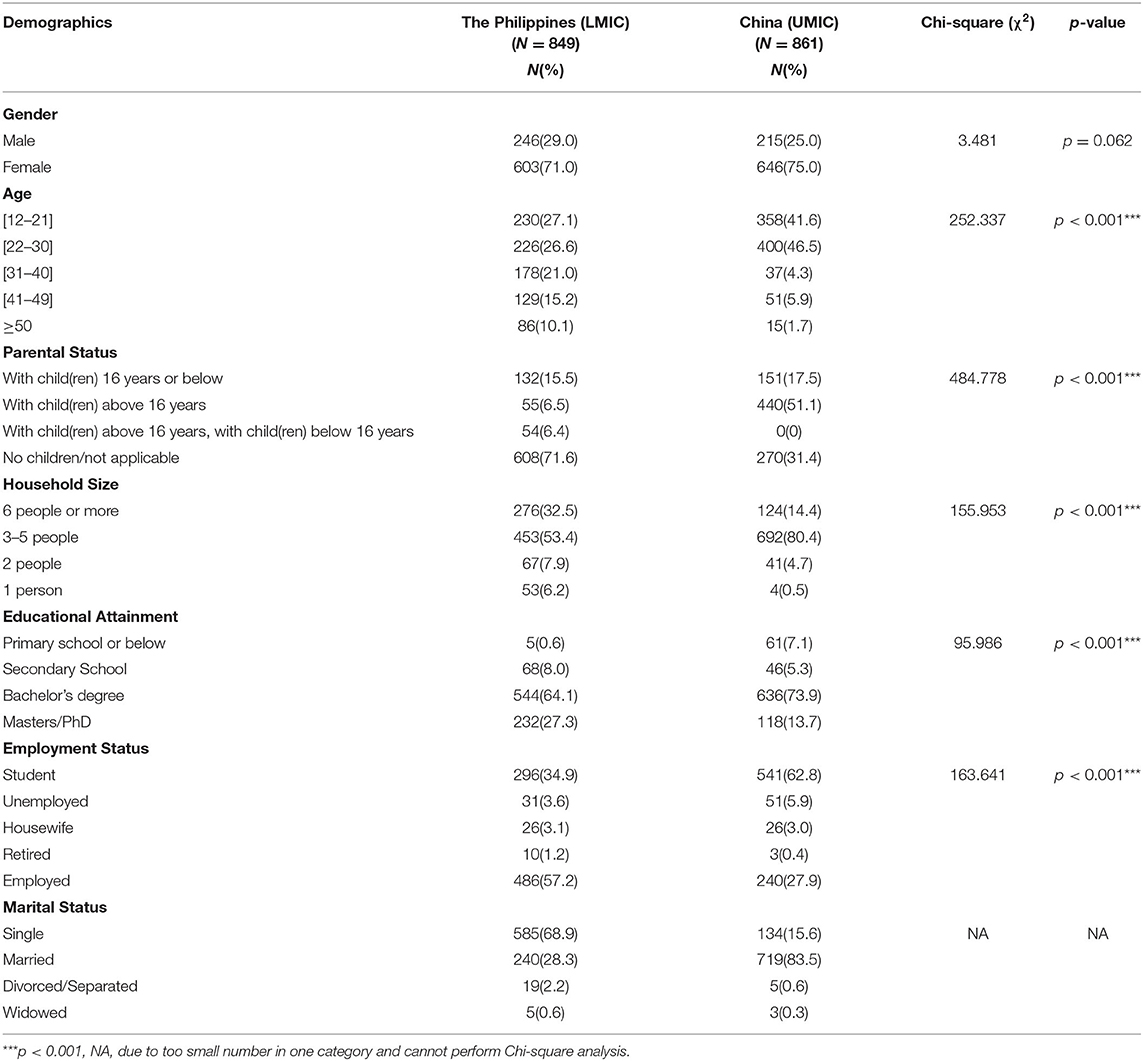

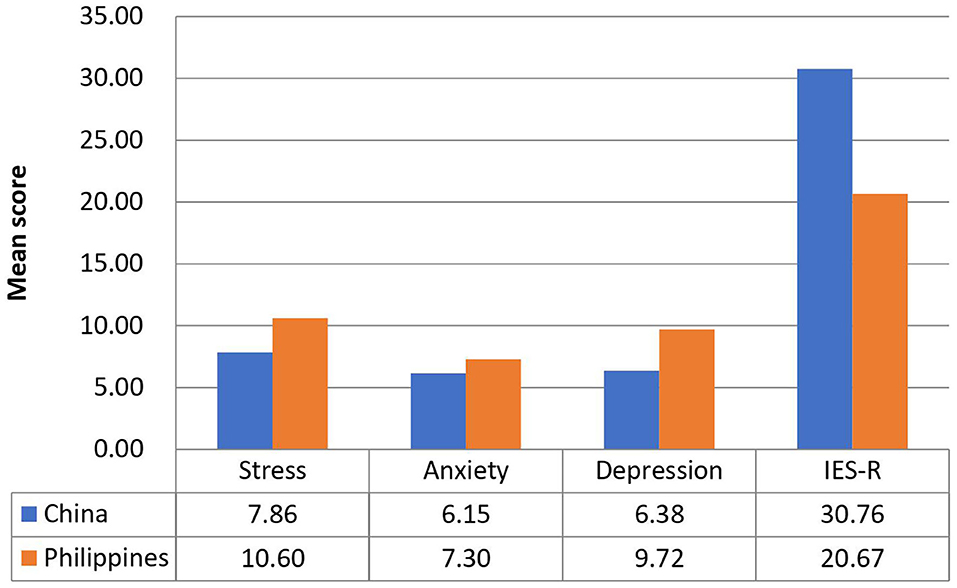

A total of 2558 participants completed the online survey. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics of participants from the Philippines ( N = 1002) vs. Malaysia ( N = 1556). Filipino (vs. Malaysian) participants indicated higher rates of education ( p < 0.001), but were more likely to be unemployed ( p < 0.001). Further, Filipino (vs. Malaysian) participants were also more likely to indicate lower income ( p < 0.001) and rate themselves lower on subjective social status ( p < 0.001). Malaysian (vs. Filipino) participants were more likely to live in urban areas ( p < 0.001). Most notably, Filipino participants (56.6%) indicated higher prevalence of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy compared to Malaysian participants (22.9%; p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between Filipino (45.9%) and Malaysian (49.2%) participants in ratings of vaccine confidence ( p = 0.105). Malaysian (vs. Filipino) participants were also more likely to report using social media (96.6 vs. 89.8%; < 0.001).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Values are presented as percent (n) or means ± SD.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742.t001

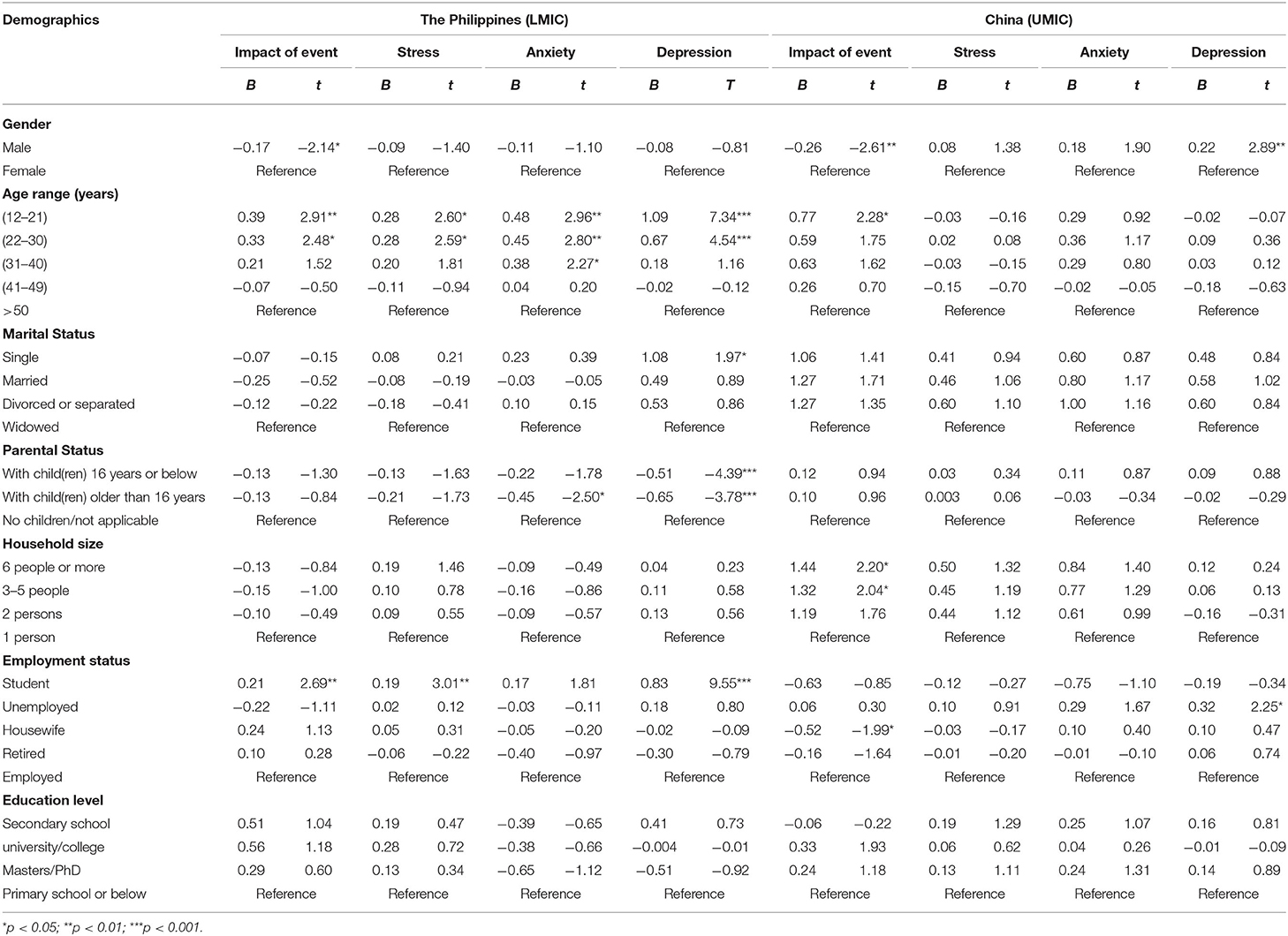

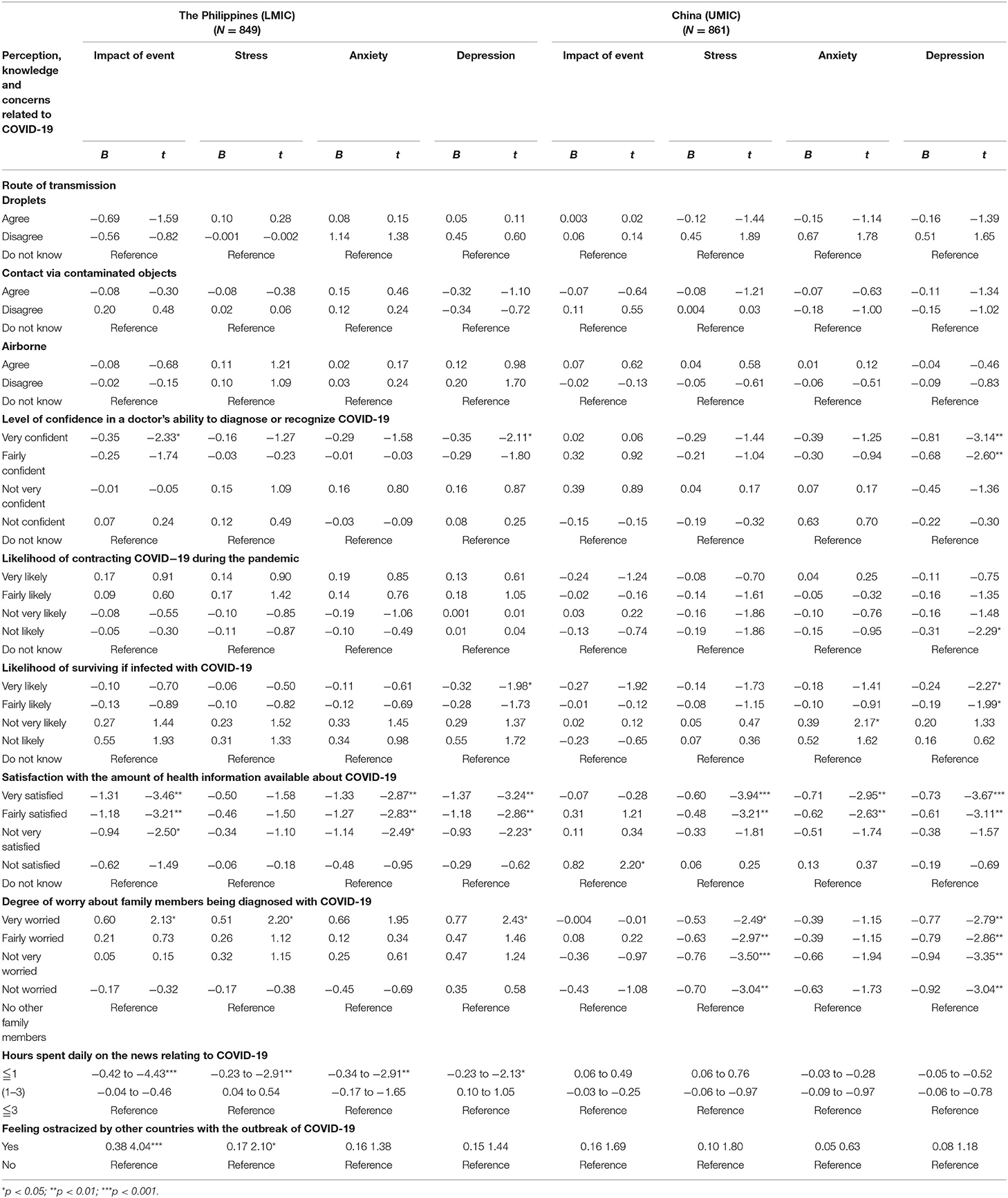

Table 2 shows significant predictors of vaccine hesitancy in both Filipino and Malaysian samples. Among Filipino participants, multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that factors associated with higher vaccine hesitancy included women (OR, 1.51, 95% CI, 1.14–2.00; p = 0.004), residing in a rural community (OR, 1.45, 95% CI, 1.07–1.95; p = 0.015), and having lower income (OR, 1.62, 95% CI, 1.20–2.19; p = 0.001). Among Malaysian participants, women (OR, 1.51, 95% CI, 1.14–2.00; p = 0.004), being aged 25–34 (vs. 18–24; OR, 1.52, 95% CI, 1.48–2.21; p = 0.027), Christians (OR, 2.45, 95% CI, 1.66–3.62; p < 0.001), completing tertiary education (OR, 2.17, 95% CI, 1.63–2.88; p < 0.001), social media use (OR, 11.59, 95% CI, 5.63–23.84; p < 0.001), and information-seeking behaviours (OR, 2.50, 95% CI, 1.74–3.61; p < 0.001) were predictors of higher vaccine hesitancy, whereas having a health impairment (OR, 0.49, 95% CI, 0.30–0.78; p = 0.003) and higher self-reported ratings on subjective social status (OR, 0.82, 95% CI, 0.75–0.89; p < 0.001) were associated with lower vaccine hesitancy.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742.t002

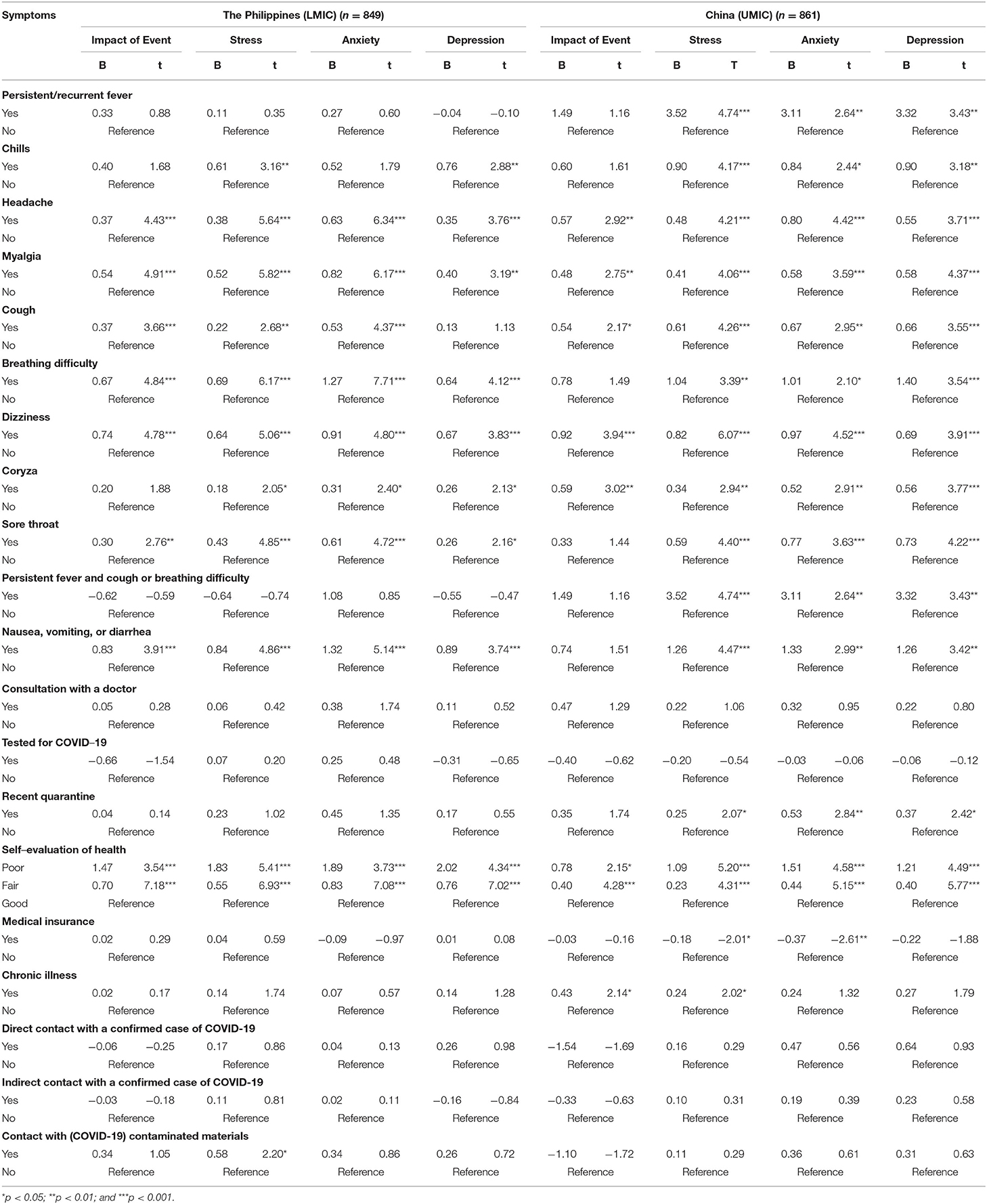

Table 3 shows significant predictors of vaccine confidence in both Filipino and Malaysian samples. Factors positively associated with higher vaccine confidence among Filipino participants included higher self-reported ratings on subjective social status (OR, 1.16, 95% CI, 1.07–1.25; p < 0.001), whereas factors associated with lower vaccine confidence included women (OR, 0.72, 95% CI, 0.54–0.96; p = 0.026) and information-seeking behaviours (OR, 0.63, 95% CI, 0.49–0.81; p < 0.001). Among Malaysian participants, factors positively associated with higher vaccine confidence included women (OR, 1.27, 95% CI, 1.18–1.60; p = 0.035), completing tertiary education (OR, 1.31, 95% CI, 1.03–1.66; p = 0.026), and higher self-reported ratings on subjective social status (OR, 1.08, 95% CI, 1.00–1.16; p = 0.036). Factors negatively associated with lower vaccine confidence included residing in a rural community (OR, 0.63, 95% CI, 0.47–0.87; p = 0.004), Christians (OR, 0.50, 95% CI, 1.20–2.24; p < 0.001), Buddhists (OR, 0.15., 95% CI, 0.10–0.22; p < 0.001), Hindus (OR, 0.24., 95% CI, 0.17–0.34; p = 0.004), information-seeking behaviours (OR, 0.42, 95% CI, 0.31–0.58; p < 0.001), and determining relevance of online information (OR, 0.68, 95% CI, 0.51–0.92; p = 0.013).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742.t003

Malaysia and the Philippines are among the most populous countries in Southeast Asia. While the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been permanent in the Philippines, it has been shown thus far to be temporary in Malaysia [ 26 ]. Between January and October 2020, around 30,000 Malaysians had been infected by the virus with a mortality rate of 0.79%, while approximately 380,000 cases of COVID-19 were detected in the Philippines with a mortality rate of 1.9% [ 2 ]. Further, 61.8% of Malaysians had completed their vaccination up until September 2021, while the percentage of completed vaccinations during the same period in the Philippines was only 19.2% [ 27 ]. Vaccine uptake is likely to be a key determining factor in the outcome of a pandemic. Knowledge around factors which predict vaccine hesitancy and confidence is of the utmost important in order to improve vaccination rates. Thus, the core aims of this research were to determine levels of hesitancy and confidence in COVID-19 vaccines among general adults in the Philippines and Malaysia, and to identify behavioural or environmental predictors that are significantly associated with these outcomes.

First, while there were no significant differences in ratings of confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine between Filipino and Malaysian participants, Filipino (compared to Malaysian) participants expressed greater vaccine hesitancy. This may be a consequence of previous vaccine scares in the years leading up to the pandemic, including the Dengvaxia controversy in 2016 [ 7 , 9 ]. Systematic reviews demonstrated that, by the end of 2020, the highest vaccine acceptance was in China, Malaysia, and Indonesia [ 28 , 29 ]. The authors postulated that this elevated awareness was due to being among the first countries affected by the virus, hence resulting in greater confidence in vaccines [ 28 ].

Next, this study shows that women expressed greater vaccine hesitancy in both countries. The evidence base shows mixed findings, with other studies reporting higher hesitancy in women [ 30 ] or in men [ 31 ]. In some countries, the gender gap is not as substantial as others. In a large global study conducted in countries such as Russia and the United States, it was found that there is greater gender gap in vaccine hesitancy among men and women compared to countries such as Nepal and Sierra Leone [ 32 , 33 ]. Unsurprisingly, what drives this hesitancy is the inclusion of pregnant women, where studies have consistently demonstrated that this population is more hesitant toward vaccination due to concerns for their babies [ 34 ]. Hence, after taking all consideration into account, gender differences in vaccine hesitancy cannot be supported with certainty. This also emphasises the need for tailored health promotion towards the key populations at risk.

There are clear differences in predictors of vaccine hesitancy in the Philippines and Malaysia. However, when results for both countries were combined, women, urban dwellers, those of Christian faith, those with higher educational attainment, higher self-reported social class, social media use, and information-seeking tendencies remained as predictors of hesitancy. Urban-dwellers and individuals with more years of education have previously been demonstrated as predictors for vaccine hesitancy [ 35 ], but contradictory results have also previously been shown [ 36 , 37 ]. Urban residents are typically more connected to the internet and social media and, thus, may be more exposed to vaccine-related misinformation than rural inhabitants who have fewer sources of information available to them [ 12 – 14 ]. Nevertheless, reports have shown higher vaccine refusals among those with strong religious beliefs such as the Amish Community in the United States and the Orthodox Protestants in the Netherlands [ 38 ], as well as some Muslim groups in Pakistan [ 18 ].

Frequent social media use is the only strong predictor for vaccine hesitancy in this study, followed by information-seeking behaviours. Research has identified that the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine is the primary concern that people have, including beliefs in available information [ 15 – 17 ]. Unfortunately, high internet literacy is a double-edged sword, since participants in this study preferred to seek information through social media, and thus may have been exposed to inaccurate information regarding COVID-19 vaccine. Previous studies have associated higher vaccine hesitancy with misinformation about the virus and vaccines [ 18 ], particularly if they relied heavily on social media as a key source of vaccine-related information [ 19 ]. A 2022 systematic review discovered that high social media use is the main driver of vaccine hesitancy across all countries around the globe, and is especially prominent in Asia [ 39 ]. Furthermore, vaccine acceptance and uptake improved among those who obtained their information from healthcare providers compared to relatives or the internet [ 40 ].

In terms of vaccine confidence, our findings show that those with higher subjective social status have higher confidence in vaccination, consistent with previous studies describing how those with a higher income had expressed willingness to pay for their COVID-19 vaccination if necessary [ 32 , 41 , 42 ]. Further, those of Christian, Buddhist, and Hindu faiths, as well as those with a tendency to seek out information, were associated with lower vaccine confidence. This is in keeping with the previous findings demonstrating that strong religious convictions are often tied to mistrust of authorities and beliefs about the cause of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is fuelled by social media [ 43 ]. Furthermore, concern on the permissibility of these vaccines in their religion reduces its acceptability [ 10 ]. However, it is interesting to note that, while the majority in Malaysia are Muslims, it did not reduce the rate of vaccine acceptance and confidence in the country.

These findings have important implications for health authorities and governments in areas focusing on improving vaccination uptake. Misinformation about vaccination greatly hampers vaccination efforts. Thus, not only is it important to understand how specific population groups are influenced by digital platforms such as social media, but it is imperative to provide the right information driven by governmental and non-governmental organisations [ 39 ]. This could be achieved by having community-specific public education and role modelling from local health and public officials, which has been shown to increase public trust [ 44 ]. Since the primary reason for hesitancy is concern about the safety of vaccines, it is crucial that education programmes stress the effectiveness and importance of COVID-19 vaccinations [ 45 ]. Participants in this study coped with the pandemic by seeking out new information, but they sought information from social media when information from the authorities was lacking or were viewed as untrustworthy, which may have contained erroneous information. One way to deter this is to empower information-technology companies to monitor vaccine-related materials on social media, remove false information, and create correct and responsible content [ 44 ].

Furthermore, behavioural change techniques have been found to be useful in stressing the consequences of rejecting the vaccine on physical and mental health [ 46 ]. The most effective “nudging” interventions included offering incentives for parents and healthcare workers, providing salient information, and employing trusted figures to deliver this information [ 47 ]. Finally, since religious concerns have been prominent in reducing vaccine confidence and increasing hesitancy in this study, it is important to tailor messages to include information related to religion, and the use of religious leaders to spread these messages [ 48 ]. These are all important factors for increasing uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine, but also may be relevant in acceptability of routine immunisations as countries look to transition towards a post-pandemic delivery of healthcare.

A limitation of this study includes its cross-sectional design and the heterogeneity among participants, which meant that temporal changes in attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines across time were not captured. Further, the need for internet access among Filipino and Malaysian participants limited the representativeness of the sample population. Thus, certain demographic were under-represented, including Filipino and Malaysian individuals over the age of 45, and people of lower socio-economic status. The surveys were also implemented in English, which may have limited the participation of target participants who were not fluent in English. In addition, due to space limitations, vaccine hesitancy and confidence were each captured using one item, which raises concerns of the items’ validity and reliability. Finally, not all independent variables were accounted for, including medical mistrust [ 49 ], vaccine knowledge [ 50 ], and specific social media platforms used [ 11 ]. We also did not assess whether participants had received any doses of the COVID-19 vaccine previously. Future research should include more important predictors to build a broader picture of vaccine-related hesitancy and confidence in the Philippines and Malaysia, and more items should be utilised to tap into these concepts more comprehensively. Despite these limitations, the core strength of this study relates to its relatively large number of participants from both countries, and its comprehensive analysis of predictors to provide as a starting point going forward.

Conclusions

The main aims of this research were to determine levels of hesitancy and confidence in COVID-19 vaccines among unvaccinated individuals in the Philippines and Malaysia, and to identify predictors significantly associated with these outcomes. Predictors of vaccine hesitancy in this study included the use of social media, information-seeking, and Christianity. Higher socioeconomic status positively predicted vaccine confidence. However, being Christian, Buddhist or Hindu, and the tendency to seek information online, were predictors of hesitancy. Efforts to improve uptake of COVID-19 vaccination must be centred upon providing accurate information to specific communities using local authorities, health services and other locally-trusted voices (such as religious leaders), and for the masses through social media. Further studies should focus on the development of locally-tailored health promotion strategies to improve vaccination confidence and increase the uptake of vaccination–especially in light of the Dengvaxia crisis in the Philippines.

Supporting information

S1 file. inclusivity in global research questionnaire..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000742.s001

- 1. Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, Appel C, Giattino C, Ortiz-Ospina E, et al. Coronavirus pandemic. Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Available from https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations .

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 3. Ritchie H, Mathieu E, Rodés-Guirao L, Appel C, Giattino C,Ortiz-Ospina E, et al. Philippines: Coronavirus pandemic country profile. Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Available from https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus/country/philippines .

- 9. Mendoza RU, Valenzuela, S, Dayrit, M. A Crisis of Confidence: The Case of Dengvaxia in the Philippines. SSRN: doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3519736.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 30 March 2022

OCTA as an independent science advice provider for COVID-19 in the Philippines

- Benjamin M. Vallejo Jr 1 &

- Rodrigo Angelo C. Ong 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 9 , Article number: 104 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

6010 Accesses

4 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health humanities

- Science, technology and society

- Social science

We comment on science advice in the political context of the Philippines during the COVID 19 pandemic. We focus on the independent science advisor OCTA Research, whose publicly available epidemiological forecasts have attracted media and government attention. The Philippines government adopted a COVID-19 suppression or “flattening of the curve” policy. As such, it required epidemiological forecasts from science advisors as more scientific information on SARS CoV 2 and COVID 19 became available from April to December 2020. The independent think-tank, OCTA Research has emerged the leading independent science information advisor for the public and government. The factors that made OCTA Research as the dominant science advice source are examined, the diversity of scientific evidence, processes of evidence synthesis and, of evidence brokerage for political decision makers We then describe the dynamics between the government, academic science research and science advisory actors and the problem of science advice role conflation. We then propose approaches for a largely independent government science advisory system for the Philippines given these political dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Dutch see Red: (in)formal science advisory bodies during the COVID-19 pandemic

Janne Aarts, Eva Gerth, … Phil Macnaghten

An evaluation of North Carolina science advice on COVID-19 pandemic response

Jessica Weinkle

Mobilization of science advice by the Canadian federal government to support the COVID-19 pandemic response

Dominika Bhatia, Sara Allin & Erica Di Ruggiero

Introduction

Pandemic science before COVID 19 presumed “predictable challenges” (Lipsitch et al., 2009 ) that informs government response especially in planning for containment interventions such as lockdowns. The success of government response is in the public perception of a positive outcome and this is reducing the number of infections. The COVID 19 pandemic is a crisis in which the orderly functioning of social and political institutions are placed into disorder and uncertainty (Boin et al., 2016 ). In political institutions this may be a threat to accepted political power arrangements and requires a response which because of their urgency, are occasions for political leaders to demonstrate leadership. However, to do so they will have to rely on actors who provide science, economic and social information and advice. In many cases these actors are within the government bureaucracy itself, as specialized agencies. Academic research institutions also provide advice. Civil society organizations with science and technology advocacies may provide advice. Science advice provided by civil society organizations, citizen science advocacy organizations and non-government think tanks are independent science advice providers. These organizations are a feature of the technical and science advice ecosystems of liberal democracies.

How governments use science advice and decide in a crisis strengthens political legitimacy. In the United Kingdom with its formal structures of government science advice such as the Science Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) a key outcome is lowering SARS CoV 2 transmission (R) rate and the way this can be achieved is to institute a lockdown. SAGE was placed in a high degree of public, media and political scrutiny in its recommendations. While formal science advice structures may work well in countries with a large and well-established science community, in countries with small science communities, independent science advice actors may be more effective than formal science advice actors.

Previous studies on the use of science advice by governments have revealed a dichotomy. Knowledge producers (e.g., academic science community) perceive high uncertainty in scientific results and consequentially become guarded in their science advice or even dispense with it in recognition of their political costs. In contrast knowledge users (e.g. politicians and science advisors in government) perceive less uncertainty in science advice and require assurances in outcomes (MacKenzie, 1993 ). This present challenges for science advice practitioners since differentiating the roles of science knowledge generation and science knowledge users, both of which can be played by academic scientists, can be conflated, and may result in political risks and opportunities.

To remedy this conflation, science advice mechanisms emphasizing independent knowledge brokerage (Gluckman, 2016a ) define a particular role for scientists in listing down science informed options for politicians and policy makers. These roles have their theoretical basis from post-normal science approaches (Funtowicz and Ravetz, 1993 , 1994 ; Ravetz, 1999 ) which place a premium on managing uncertainty in crises through consensus building and identifying of science informed policy options. The science advice “knowledge broker” will not be functioning as part of the knowledge generation constituency but in a purely advisory capacity identifying policy options. This is the model promoted by the International Network for Government Science Advice (INGSA). This also insulates the science advisor from undue political interference.

However, in countries where the science community is small and politically underrepresented, performing these well-defined functions will be difficult due to a lack of experts and the range of scientific expertise they can provide. In small science communities, the problems of role conflation become more apparent and may place the science advisor prone to political pressure. Vallejo and Ong ( 2020 ) reviewed the Philippines government response and science advice for COVID 19 from when the World Health Organization (WHO) advised UN member states of a pandemic health emergency on January 6 to April 30, 2020 when the Philippines government began relaxing quarantine regulations. They noted the roles of various science advice knowledge generation actors such as individual scientists, academe, national science academies and organizations and how these were eventually considered by the Inter Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF-EID) which is the government’s policy recommending body for COVID 19 suppression. Of these advisory actors, the private and independent OCTA Research Group hereafter referred to as OCTA, which consists of a multi-disciplinary team of academics from the medical, social, economic, environmental, and mathematical sciences mostly from the University of the Philippines, became the most prominent source of government science advice with its proactive but unsolicited provision of government science advice.

Because of this engagement, like SAGE in the UK, OCTA became a focus of intense media, public, and political interest and could represent an effective modality for independent science advice especially in newly industrialized countries where the science community is small but gaining a larger base of expertise. While science advice in this context may involve a conflation of science advice roles, we look into this conflation and their political dynamics in pandemic uncertainty and how consensus was formed in COVID 19 policy advice. This paper explores on how independent science advice has proved to be the chief source science advice in a polarized political environment in a Southeast Asian nation from the start of the pandemic in January 2020–October 2021.

The Philippine science advice ecosystem

Science advice in the Philippines takes on formal (with government mandate), informal (without government mandate) solicited and unsolicited modalities. Formal science advice to the President of the Philippines is provided by the National Academy of Science and Technology (NAST) by virtue of Presidential Executive Order Number 812. The government solicits science advice from the NAST which provides advice as position or white papers to cabinet for consideration. The NAST is not a wholly independent body from government. It is attached to the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) for administrative and fiscal purposes.

Other sources of science advice are from the universities such as the University of the Philippines (UP). The UP is designated by charter (Republic Act Number 8500) as the national, research and graduate university. This mandates it to provide science advice to the government. Academics in their individual capacities, as members of think-tanks or civil society organizations provide unsolicited and informal science advice to government through the publication of scientific and position papers as well as technical reports. Academics who are part of non-government science academies such as the Philippine American Academy of Science and Engineering (PAASE) provide similar advice. The science advice system in the Philippines is diverse with each actor having its own political and development advocacy. The system is largely ad hoc and informal, and science advice are largely unsolicited. This dynamic determines its role with the government. Also, when these science advice actors are consulted by the government, they are all primuses inter pares in dealing with political actors in government. Members of the science advisory bodies are mostly active academics. They are all knowledge producers and users at the same time.

There are few studies that directly examine the politics of science advice and uncertainty in the Philippines, and these are in disaster risk reduction management (DRRM). This can serve as a template for analysis for the COVID 19 pandemic in the Philippines which has been construed by government and the public as a global disaster. The strengths and weaknesses of the present science advisory system may be seen in DRRM advice.

DRRM as a framework for government science advice in the Philippines

Disasters which have affected the Philippines in the first decade of the 21st century such as Typhoon Ketsana (Philippine name “Ondoy”) in 2009 which flooded much of the National Capital Region, have resulted in several studies investigating the resilience of urban communities and how science advice is used in crafting urban resilience policies and governance. This disaster was also the major impetus for disaster legislation with enactment of the DRRM law (Republic Act Number 10121). This law institutionalizes and mainstream the development of capacities in disaster management at every level of governance, disaster risk reduction in physical and land-use planning, budget, infrastructure, education, health, environment, housing, and other sectors. The law also institutes the establishment of DRRM councils at each level of government. The councils are composed of members from government departments, the armed forces and police, civil society, humanitarian agencies but most notably, does not include academic research scientists. Science advice is given by CSOs but that is in accordance with their particular advocacies and their political objectives.

A study commissioned by the independent think tank Odi.org and by researchers of De La Salle University in Manila (Pellini et al., 2013 ) concluded that there is a “low uptake of research and analysis” to inform local decision in DRRM. It also identified a reactionary response to disasters rather than a response to disaster risks. Formal and informal science advice is most effective in local government if local executives prioritize risk reduction with consensus building at the local level. In general, formal, and informal science advice is less effective at the national level. The Philippine science advisory ecosystem is focused on formal science advice at the national level and thus the effectiveness of science advice is placed into question. The disaster-prone province of Albay is held as an example where science advice is more effective at a devolved level from the national (Bankoff and Hilhorst, 2009 ; Pellini et al., 2013 ).

At the lower levels of governance, informal science advice is predominant and is provided by science advice actors such as non-government organizations (NGO) or by civil society organizations (CSO). While NGOs, CSOs and, the government communicate using a consensus vocabulary (Funtowicz and Ravetz, 1994 ) in DRRM, differing risk perceptions have resulted in different domains of political engagement (Bankoff and Hilhorst, 2009 ) tied to different interpretations of the risk vocabulary in terms of political costs. And so the dominant paradigm remains disaster reactive with a general trend in “dampening uncertainties” (Pearce, 2020 ) in order to come up with positive political outcomes for the science advisors and the government.

While the present DRRM law institutionalizes consultation and collaboration, the law does not mandate a science or technical advisor to sit on DRRM councils at each level of governance. This is one possible reason for the “low uptake of research and analysis” at higher levels of governance while at lower levels of governance, science advice is provided by CSO and other advocacy organizations in an independent and ad hoc manner as they are more effective in establishing collaborative relationships with local government executives and councils.

IATF-EID and OCTA Research as an independent science advisor

Vallejo and Ong ( 2020 ) review the timeline for the Philippines government COVID 19 response, the formation of the Inter-agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF-EID), the science advisory ecosystem, and how the science community began to dispense informal science advice for consideration by IATF-EID. IATF-EID is the government’s policy recommending body for COVID 19 suppression and is composed of members from the cabinet and health agencies of the government. Informal science advice initially came from individual or groups of academics modeling the initial epidemiological trajectory of COVID 19. The IATF-EID is not a science evidence synthesizing or peer review body. It must rely on many science advisory actors as consultants. The University of the Philippines COVID 19 Pandemic Response Team is a major actor as its scientists are well known in the medical and disaster sciences. But it was OCTA which is composed mainly of academics from the University of the Philippines and the University of Santo Tomas. OCTA that has emerged as the leading government science advice actor for COVID 19.

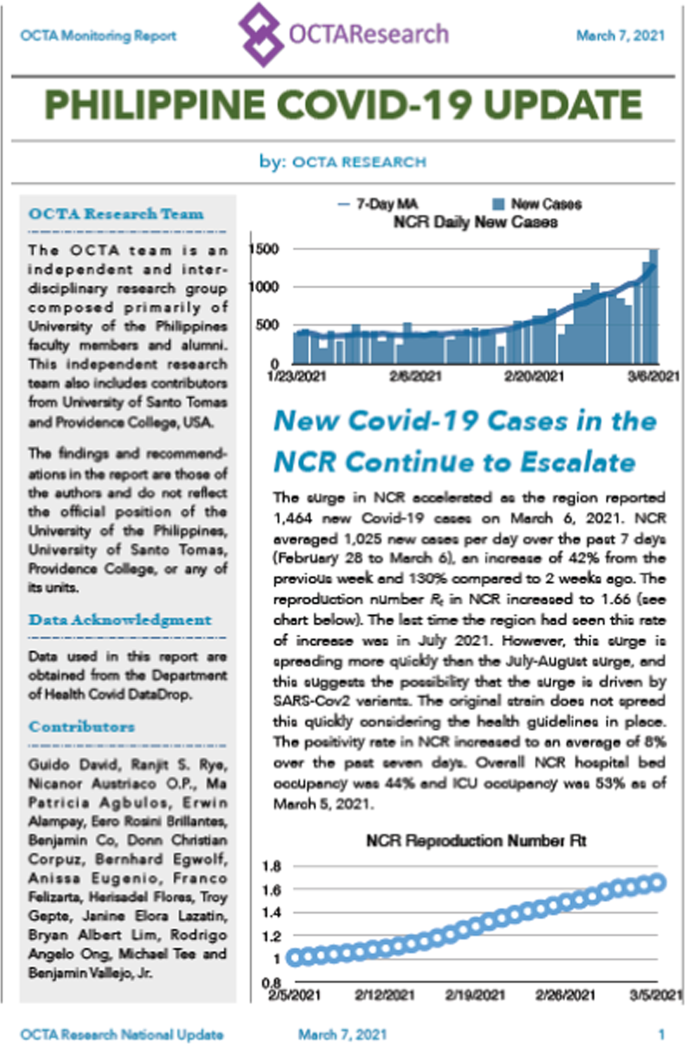

OCTA bills itself as a “polling, research and consultancy firm”(Fig. 1 ). That OCTA has been identified in media reports as the “University of the Philippines OCTA Research group” is to be expected as academic credibility is a premium in the Philippines as like in other countries (Doubleday and Wilsdon, 2012 ). This however can constrain its political relationship with government science advice actors and so OCTA had to publish disclaimers that while it is composed of mostly University of the Philippines academics, it claims to be an independent entity. OCTA’s polling function is separate from its science advice advocacy which is performed by volunteer scientists as testified by OCTA President Ranjit S Rye to the Philippine Congress Committee on Public Accountability on 3 October 2021. The polling function is supported by paid subscribers while the science advice advocacy is supported by unpaid volunteers. Volunteer OCTA epidemiological modelers and policy analysts have provided robust estimates on the COVID 19 reproductive number R0, positivity rates, hospital capacity and attack rates at the national, provincial, and local government levels every fortnight beginning April 27, 2020. It has since issued 76 advisories and updates (Fig. 2 ). Local and provincial governments have used their forecasts in deciding quarantine and lockdown policies in their jurisdictions. OCTA publicly released these forecasts in academic websites, institutional media and social media. This allowed for public vetting and extended peer review with other independent scientists validating its forecast estimates. Some independent scientists contest methodologies and OCTA has appropriately responded to these.

OCTA is a primarily polling organization but has taken on COVID-19 monitoring, forecasting and advice services.

An OCTA COVID-19 forecast update (7 March 2021).

OCTA like other science advice actors, based its epidemiological analyses on the Philippines Department of Health (DOH) Data Drop whose data quality was publicly perceived as poor even though steps have been taken to improve data quality. The DOH in the interest of transparency began Data Drop on April 15, 2020. Data Drop has information on the number of active cases, recovered cases, and hospital admissions. With Data Drop, OCTA was able to issue its first epidemiological forecast.

OCTA does not belong to the formal structures of science advice in the Philippines but is part of the informal science advice community. Its volunteer experts are publicly known. OCTA has emerged as the leading information and science advice provider for the public. How did it become the leading source of science advice and often cited by social and mainstream media and acknowledged by government?

Uncertainty perception in COVID-19 suppression and the political context of role conflation

OCTA became the leading source of science advice when by publishing weekly forecasts on COVID-19 epidemiological trends, it reduced public perception of uncertainty of the pandemic. The bulletins estimated national and regional R0, attack rates, hospital capacity and ICU bed capacity. While most countries worldwide have adopted suppression as the main strategy (Allen et al., 2020 ) a few countries most notably New Zealand, adopting a COVID 19 elimination strategy. The Philippines decided on a suppression policy or a strategy of “flattening the curve” which necessitated lockdowns with the outcome of reducing R0 and COVID-19 hospital admissions.

The most socially and economically disruptive intervention is lockdown with is tied with the uncertainty of lifting quarantine (Caulkins et al., 2020 ). The Philippines instituted a national lockdown beginning 14 March 2020 and instituted a graded system of “community quarantine” which allowed for almost cessation of economic activity and mobility in enhanced community quarantine (ECQ), a modified enhanced community quarantine (MECQ) which allows for the opening of critical services and a limited operation of public transport, to a near open economy and unimpeded local mobility in modified general community quarantine (MGCQ) and a low risk general community quarantine (GCQ) which allows for most economic activities subject to health protocols (Vallejo and Ong, 2020 ) which regulated mobility between quarantine zones.

It is in lockdown policies that uncertainty perception takes on a large political dimension (Gluckman, 2016b ; Pearce, 2020 ). Science advisors have to provide forecasts on the trajectory of R0 for politicians to make a decision on tightening or relaxing of quarantine. In this manner OCTA has provided not only the quarantine grade option but the best option while recognizing that the constraint to lessening the perception of uncertainty lies on data quality itself (Johns, 2020 ). OCTA has raised this concern questions on the accuracy and timeliness of DOH’s Data Drop. In doing so, it has done multiple scenario models to assess the accuracy of data. If the government takes on lockdown as the main strategy for COVID 19 suppression, then it must ensure that science advisory actors are able to deal with the multiple uncertainties that data quality will generate. Science advisory actors can be both knowledge generators and users and this conflation has several consequences such as a tension between knowledge production and use which is called as the “uncertainty monster” (Van der Sluijs, 2005 ).

OCTA it its business model has role conflation. While its polling services are paid for by subscribers, the science advice advocacy function in COVID-19 is volunteer based. This conflation was questioned by members of Congress. Thus, the political context for OCTA is within the problem of role conflation in science in a particular political and academic context which may be the norm in developing countries. The politics of conflation in science advice in the UK was demonstrated when two esteemed epidemiologists belonging to two research groups, Professor Neil Ferguson of the Imperial College London (ICL) and Professor John Edmunds of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) released R0 estimates to the public. ICL and LSHTM provided advisories to media and the UK government SAGE, with two different estimates for R0. The ICL estimate (2.0–2.6) were earlier made known to media while the LSHTM estimate (2.7–3.99) underwent peer review and was published in Lancet Public Health (Davies et al., 2020 ). The two estimates became the focus of controversy as the UK Chief Science Advisor Professor Patrick Vallance echoed Edmund’s claim of a case doubling time of 5–6 days. The SAGE consensus was 3–4 days, thus necessitating a sooner rather than later lockdown. The question on when to impose a lockdown is also a political matter. This placed SAGE and its established protocols of keeping experts anonymous under public criticism and scrutiny.

Pearce ( 2020 ) reviews the problem of role conflation of knowledge providers (the modelers) and the knowledge users (government) if they occupy both positions at the same time. Edmunds is a SAGE member (knowledge user) as well as a producer of science information as an academic. This conflation of roles resulted in the “dampening of uncertainties” for political reasons. The government is not acutely aware that this ultimately stems from poor data quality and the resulting scientific uncertainty has great political costs (UP COVID-19 Pandemic Response Team, 2020 ).

Similarly, OCTA has faced questions in its R0 estimates which differs from estimates by other scientists. OCTA’s estimates are higher (2.3) than what government initially used (2.1) in characterizing the surge in cases beginning Feb 2021. With R0 and positivity rates increasing, OCTA recommended an ECQ for the 2021 Easter break which was extended to a MECQ until 30 April 2021 (CNN Philippines, 2021 ). Like in the UK, this will affect policy decision making based on doubling time and the allocation of health resources. But unlike in the UK where there is a formal process of science peer review, in the ad hoc nature of science advice review in the Philippines, much of this “open peer review” by academics was on social media thus giving a polarizing political environment in policy decision.

OCTA has long been aware of the problem of role conflation which is a problem in a country with a small national science community. The national science community is small with only 189 scientists per million people. It thus has sought the expertise of overseas Filipino scientists to expand its advisory bench and to reduce possible role conflation. The overseas scientists are not associated with government health research agencies and so could act more independently. This was a strategy to deal with the possibility of “dampening of evidence”. The Presidential Spokesperson Mr. Harry Roque said that OCTA should cease reporting results to the public and rather send these “privately” to government (Manila Bulletin, 2020 ; Philippine Star, 2020 ). Roque is misconstruing the role of OCTA as a formal government science advisory body when it is not. The statements of the government spokesman may reflect debates in cabinet about the necessity and role of government science advice in and outside of government and their political costs. IATF-EID has its own experts as internal government science advisors. However, their advice must still be subject to peer review and so a mechanism must be found for these experts to compare forecasts with independent advisors such as OCTA. This will minimize public perception that the government silencing OCTA to dampen uncertainties for political outcomes. Public trust in government science advice has always been low if there is no transparency (Dommett and Pearce, 2019 ).

OCTA forecasts have been criticized by government economic planners especially in tourism (Philippine Daily Inquirer, 2020 ) as the forecasts directly affect plans to reopen important economic sectors. Some criticism is apparently political (Manila Times, 2020 ) and implies alienation of OCTA from its academic institutional linkage base. OCTA forecasts have been more and more adopted by the IATF-EID (ABS-CBN, 2021 ) This is a political dynamic for science advice actors sitting in government. Internal science advice actors will have to deal with populist interests in government and their advice may be “written off” (Boin et al., 2016 ). Independent science advice actors do not want their government science advice to be written off and so are likely to take the public route in presenting their synthesis of evidence and options.

Pandemic policy response is all about the management of multiple epidemiological uncertainties. This is when inability of government to manage it became apparent when doctors through the Healthcare Professionals Alliance Against COVID-19 (HPAAC), an organization which is comprised of the component and affiliate societies of the Philippine Medical Association admonished the government to increase quarantine restrictions from General Community Quarantine to Modified Enhanced Community Quarantine for a period of 2 weeks in August to allow the health workers to recover from exhaustion (One News, 2020 ). This is due to the surge in new cases and the overburdening of the healthcare capacity which OCTA earlier forecasted (David et al., 2020 ). The threat of a “doctors strike” would have been politically damaging to the government and the President decided to heed the doctors’ request.

The Philippines response is not very different from response of the majority of 22 countries examined by INGSA’s COVID 19 policy tracker (Allen et al., 2020 ), where these countries embarked on a monitoring and surveillance policy from January to March 2020. The INGSA study also shows that few countries have utilized internal and external formal science advisory bodies in the first 3 months of the pandemic. The Philippines is not one of the countries which INGSA tracked but similarly it started to seek the advice of individual experts by March 2020. Many of these experts posted their unsolicited science advice on social media.

Like most of the 22 INGSA tracked countries, after the 3rd month of the pandemic, the Philippines enacted legislation to deal with the social and economic impact of lockdowns. But this has not yet resulted in legislation passed in the Philippines Congress to deal with developing and improving systems for pandemic response through research and development initiatives although the late Senator Miriam Defensor Santiago filed Senate Bill 1573 “Pandemic and All Hazards Act” in September 2013 (Senate of the Philippines 16th Congress, 2013 ) in response to MERS and Senator Manny Villar in April 2008 filed Senate Bill 2198 “The Pandemic Preparedness Act” (Senate of the Philippines 14th Congress, 2008 ). Both bills institute a Pandemic Emergency Fund and mandates a Pandemic Emergency Council or Task Force, roughly along the lines of the DRRM Law. Defensor-Santiago’s bill was refiled by Senator Grace Poe as Senate Bill 1450 “An Act Strengthening National Preparedness and Response to Public Health Emergencies by Creating a Center for Disease Control” during the first session of the 18th Congress on 27 April 2020 (Senate of the Philippines 18th Congress, 2020 ). Poe’s bill updates Defensor-Santiago’s bill by proposing the creation of Center for Disease Control

These bills have not been enacted into law. The Philippines also did not enact legislation or executive on creating or strengthening science advisory capacity which 12 of the 22 countries INGSA tracked did. However, a senator has recently approached OCTA for policy input in developing formal crisis science advice legislation.

Prospects for independent government science advice in the Philippines

The Philippines government’s COVID 19 suppression policy is based on science informed advice. However, this has been provided informally by individual experts consulted by IATF-EID and this advice is not subjected to formal peer review. This has exposed experts to political criticism and attack as their identities and roles have been spun by media and government media spokespersons as integral to IATF-EID. At least one expert has resigned from providing science advice due to possible conflicts of interests. In this science advice gap, entered OCTA Research in the second quarter of 2020 and continued to 2021 and 2022.

The informal science advice actors more often give their forecasts directly to the media while the formal actors give it to the government agency that commissioned it. The government uses the evidence in determining what quarantine status to implement nationally and regionally through the recommendation of the IATF-EID.

The government’s policy decisions on COVID 19 suppression are chiefly based on a single statistical estimate, R0 but more recently has included positivity rate and hospital capacity. Science advisory bodies must defend R0 and the other estimates to the government and in the public sphere. The estimates will have incorporated all statistical uncertainties in this number. OCTA has done this by publicly reporting low, moderate and high R0 scenarios and the consequent projections for new cases, hospital utilization and attack rates at the national, regional and local government level. The government has used these estimates in its monthly policy responses.

Considering that both use the same DOH Data Drop dataset, dissonance between OCTA and government scientists’ recommendations have been reported in print, broadcast, and social media. This involves largely the differences in interpreting the framework of quarantine status and risks, with government experts tending to question OCTA’s projections with a very conservative precautionary interpretation of evidence. One doctor with the IATF-EID has accuses OCTA of using “erroneous” and “incomplete” data (Kho, 2021 ). This dissonance has led politicians to label OCTA as “alarmist” (David, 2021 ).

OCTA is a knowledge producer in science advice since it constructs DOH epidemiological data into models informed by epidemiological theory. Even if OCTA has decided to remain completely independent as a science advisory body, it is not completely insulated from political attack. Political attack is a result of perceived role conflation in the science advice ecosystem and process which is exacerbated by the nature of uncertainty in science advice leading to accusations of OCTA being “alarmist. OCTA was misconstrued by the government as its own knowledge producer and its critics demanded that it be completely alienated from its academic institutional linkages. OCTA’s weakness and the weakness of the Philippines crisis science advisory system overall, is the lack of external and extended peer review. This is a consequence of a small science community where there are few actors who can perform this role with citizen scientists. In a postnormal science advisory environment, the role of extended peer review is important in validating policy options and creating public consensus.

OCTA has recently partnered with Go Negosyo, a small and medium business entrepreneurship (SME) advocacy, headed by Presidential advisor for entrepreneurship, Joey Concepcion. Mr. Concepcion has a minister’s portfolio. OCTA in this arrangement will provide data analytics services and science advice for SMEs for a business friendly COVID exit policy with a safe reopening of the economy based on vaccination prioritization strategies (Cordero, 2021 ). This move also evidences OCTA’s influence in setting new policy directions in government’s adoption of a new quarantine classification system of Alert Levels, an idea first proposed by OCTA Fellow and medical molecular biologist Rev Dr. Nicanor Austriaco OP and mathematical modeler Dr. Fredegusto Guido David. This is a political move on OCTA’s part to deflect critics in Congress as the business sector has a large political clout in government.

While a pandemic crisis like COVID 19 gives political leaders an advantageous occasion to demonstrate personal leadership, their constituencies will tend to expect a more personalistic crisis management. In this independent science advice plays a crucial political dynamic by building public trust, ensuring reliable statistical estimates reviewed by the academic science community, and managing political advantages and risks. These are all in the context of epidemiological uncertainties. In the Philippines, public criticism of the pandemic response is fierce due to the primarily law and order policing approach which raised concerns on human rights violations (Hapal, 2021 ) as well as those cases began to rise in the first quarter of 2021 (Robles and Robles, 2021 ). The failure to deal with uncertainties in science without effective science advice may entail large political costs. Managing public perception and the use of government scientific and technical advice is a delicate balancing act in liberal democracies. The press and media will report and scrutinize science informed decisions while shaping public opinion of crisis decisions. Academic science and civil society organizations not part of the advisory system provide another level of scrutiny and critique. Social media has extremely broadened the venue for public scrutiny and, open or extended peer review of crisis decisions.

These realities were not faced by political leaders as recently as 30 years ago. However unfair or unrealistic the critique by constituencies and the press, public expectation is real in political terms. And while politicians can “write off” certain social and political sectors in deciding which crisis response is best, this is no longer tenable in democracies in the 21st century.

In these realities emerge new actors of engaged independent academic science advisors such as OCTA. It has certainly played the role of a knowledge generator and to some extent a knowledge broker. And like any science advice actor, OCTA was not immune to political attack, and this would suggest that SAGE with its embeddedness in the administrative and ministerial structures in the UK, largely missing in the Philippines (Berse, 2020 ), will be subject to great political interference which may limit its effectiveness. Political interference may masquerade as technical in nature (Smallman, 2020 ).

The Philippines government response to COVID 19 has been described as “deficient in strategic agility” (Aguilar Jr, 2020 ) partly due to its inability to mobilize scientific expertise and synthesize science informed advice options in governance. Thus, a plausible proposal to strengthen science advice is in reframing the DRRM policy and advisory structures and applying these to crisis in order to strengthen science advice capacity at all levels of governance. As Berse ( 2020 ) suggests “tweaking the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council structure, which has a seat for an academic representative, might do the trick. This national set-up is replicated by law at the provincial, city and municipal levels”.

Berse also suggests that an academic should be appointed to sit at each of these councils. The major constraint is that there are very few academics willing to sit as this will expose them to political criticism and interference. If academics are appointed, then their expertise should not be unduly constrained by political interference. They should be backed by several researchers and citizen scientists coming from multiple disciplines in reviewing science informed policies. More and more citizen scientists have come up with science advice which for consistency of policy should be reviewed in extended consensus by scientists and stakeholders (Funtowicz and Ravetz, 1993 ; Marshall and Picou, 2008 ).

The closed and elitist system of science advice in the Philippines with its handful of actors, mainly appointed by government, are inordinately prone to political pressure. This necessitates the role of independent science advisors. Independent science advisors can act as a “challenge function” to government experts whose recommendation if ignored contributes to further erosion of public trust in government (Dommett and Pearce, 2019 ). Independent science advice when framed in the context of parliamentary democracy can be likened to “shadow cabinets” in this way they provide a check, balance and review of science evidence and is called “shadow science advice” (Pielke, 2020 )

As pandemics and other environmentally related public health emergencies are expected to be more frequent in the 21st century, the public will be less tolerant of social and political instability and demand a clear science informed response from their politicians. However, most politicians do not have enough scientific and technical competency to do so and so will have to rely on science informed advice which has degrees of outcome uncertainty (Gluckman, 2016b ). If science informed options are ignored for political gains, this is not a result of broken science advice and knowledge generation systems but a dysfunctional political and governance system. The huge cost in life and economic opportunity left by the pandemic demands functional government informed by science advice.

Furthermore, any government to cement its legacy must find a COVID 19 crisis exit strategy after the operational aspects such as a mass vaccination strategy have been met and the social, health (Dickens et al., 2020 ), economic and political situation has been stabilized (Gilbert et al., 2020 ). In COVID 19, this is a gradual relaxation of lockdown and quarantine (Leung and Wu, 2020 ) with the roll out of vaccines.

Vaccination is the main COVID-19 exit strategy of the government (Congress of the Philippines, 2021 ) and given the large existing vaccine hesitancy of 46% as OCTA estimated in February 2021 (Tomacruz, 2021 ), there is a need to increase public confidence on vaccines (Vergara et al., 2021 ). Public distrust of vaccines became a major public health concern due to the Dengvaxia vaccine rollout controversy in November 2017 when Sanofi publicly released a warning that vaccination posed a risk if given to people who never had a dengue infection (Larson et al., 2019 ). The political impact was damaging to the Benigno Aquino III presidential administration, which rolled out the vaccine in 2016 before Aquino III’s term ended. The drop in vaccine confidence was significant, from 93% in 2015 to 32% in 2018. The new presidential administration of Rodrigo Duterte placed the blame on Aquino III, and this resulted in social and political polarization, loss of trust in the public health system which have continued in the COVID-19 pandemic. The “blame game” is political risk in any liberal democracy. This can be a long drawn out affair where government will have to establish accountability and the “blame game” is expected with various independent boards and blue ribbon committees setting the narrative (Boin et al., 2016 ). In the Philippines, several hearings in the House and Senate in which Sanofi and previous Department of Health leadership were called to give testimonies, further worsened political and social polarization to vaccination. These independent boards, blue ribbon committees and fact-finding investigations, however, are prone to agency capture by ruling party politics. This is evident in the Philippines. The government exit strategy for COVID-19 is clouded by these polarizations. OCTA will be expected by the public to provide government science advice on vaccination policies, and this will have great political costs for independent science advice. As vaccination in the Philippines has become a political issue more than as a public health issue, other think tanks and academic research institutions which have investigated Dengvaxia, and vaccine compliance have been more guarded as not to attract undue negative political comment. OCTA to its credit, has successfully navigated political risks in its COVID-19 forecasts and in a political move, has allied with a SME advocacy headed by a close Presidential advisor on economic affairs. OCTA can continue to maintain its credibility by periodically issuing forecasts and policy option recommendations and reducing social and political polarizations through consensus building with the public, government, and science community. Here is where the independent science advice actors will have a place, and that is to set the objective bases for science informed policy decisions while recognizing the political dynamic. How independent science advice will result in lasting policy impacts in the Philippines remains to be seen. The government and the public have relied on OCTA forecasts because of OCTA’s increasing presence in broadcast, print, and social media. This is evidence of the effective science communication strategy of the organization. But with the Government increasingly using OCTA’s forecasts and policy recommendations, this is evidence that government science advice has political dividends and risks which may affect politicians’ political standing with the electorate in the 2022 election.

Data availability

COVID-19 open data cited in this paper can be accessed through the Philippines Department of Health Data Drop https://doh.gov.ph/covid19tracker and through OCTA Research https://www.octaresearch.com/ .

ABS-CBN (2021) Metro Manila COVID-19 surge begins ahead of Christmas: OCTA Research. https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/12/22/20/metro-manila-covid-19-surge-begins-ahead-of-christmas-octa-research . Accessed 3 Jan 2021

Aguilar Jr FV (2020) Preparedness, agility, and the Philippine response to the Covid-19 pandemic the early phase in comparative Southeast Asian perspective. Philipp Stud Hist Ethnogr Viewp 68(3):373–421

Article Google Scholar

Allen K, Buklijas T, Chen A, Simon-Kumar N, Cowen L, Wilsdon J, Gluckman P (2020) Tracking global knowledge-to-policy pathways in the coronavirus crisis: a preliminary report from ongoing research. INGSA. https://www.ingsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/INGSA-Evidence-to-Policy-Tracker_Report-1_FINAL_17Sept.pdf

Bankoff G, Hilhorst D (2009) The politics of risk in the Philippines: comparing state and NGO perceptions of disaster management. Disasters. 33(4):686–704

Berse K (2020) In science we trust? Science advice and the COVID-19 response in the Philippines https://www.ingsa.org/covidtag/covid-19-commentary/berse-philippines/ . Accessed 3 Jan 2021.

Boin A, Stern E, Sundelius B (2016) The politics of crisis management: Public leadership under pressure. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book Google Scholar

Caulkins J, Grass D, Feichtinger G, Hartl R, Kort PM, Prskawetz A, Seidl A, Wrzaczek S (2020) How long should the COVID-19 lockdown continue? PLoS ONE 15(12):e0243413

Article CAS Google Scholar

CNN Philippines (2021) OCTA Research: four-week MECQ to “knock out” COVID-19 case surge. https://cnnphilippines.com/news/2021/3/24/OCTA-Research-4-week-MECQ-knock-out-surge.html . Accessed 16 Apr 2021

Congress of the Philippines (2021) An act establishing the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination program expediting the vaccine procurement and administration. Providing Funds Therefor, and for Other Purposes, Manila. https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/downloads/2021/02feb/20210226-RA-11525-RRD.pdf . Accessed 16 Apr 2021

Cordero T (2021) Go Negosyo, OCTA Research ink partnership on data-sharing, proposals to reopen economy. GMA News Online. https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/money/companies/807569/go-negosyo-octa-research-ink-partnership-on-data-sharing-proposals-to-reopen-economy/story/ . Accessed 25 Oct 2021.

David G, Rye R, Agbulos M, Alampay E, Brillantes E, Lallanam R, Ong R, Vallejo B, Tee M (2020) COVID-19 forecasts in the Philippines: NCR, Cebu and COVID-19 hotspots as of June 25, 2020. OCTA Research, Quezon City, Philippines

Google Scholar

David R (2021) Probing OCTA. Philippine Daily Inquirer https://opinion.inquirer.net/142869/probing-octa . Accessed 25 Oct 2021.

Davies NG, Kucharski AJ, Eggo RM, Gimma A, Edmunds WJ, Jombart T, O’Reilly K, Endo A, Hellewell J, Nightingale ES et al. (2020) Effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 cases, deaths, and demand for hospital services in the UK: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health 5(7):e375–e385. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30133-X

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Dickens BL, Koo JR, Lim JT, Park M, Quaye S, Sun H, Sun Y, Pung R, Wilder-Smith A, Chai LYA et al. (2020) Modelling lockdown and exit strategies for COVID-19 in Singapore. Lancet Reg Health-West Pac 1:100004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100004