About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets & Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Social Impact

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

On a Mission to Teach the World the Basics of Personal Finance

Annamaria Lusardi has found high rates of financial illiteracy in the U.S. and around the globe. She’s determined to turn them around.

December 12, 2023

“Developing personal finance skills is as important as learning how to read and write.” | iStock/jemastock

Americans aren’t good at managing their money — and there are signs that the problem is getting worse.

Already saddled with record levels of student debt, young adults, for example, are even more unlikely to monitor their credit card debt and bank balances. Some people trick themselves into thinking that store refunds or anything less than $5 amount to free money. And too many people pay for online subscriptions they don’t use.

Thanks to the pioneering work of Stanford economist Annamaria Lusardi , numerous studies show how little people know about money. For two decades, Lusardi has been tracking financial literacy rates using three basic questions that she helped design and are now used as a standard measure around the world.

Her latest analysis of how Americans responded to those three questions in 2021 underscores their lack of financial know-how. In all, just 29% percent of survey participants answered all three questions correctly, while the rest either got them wrong or indicated they didn’t know.

Only 53% of respondents demonstrated an understanding of how inflation works as prices on everything from cereal and cars were spiking. About two-thirds (69%) knew how to do a simple interest-rate calculation, but only 42% understood how, when it comes to investment risks, mutual funds are generally safer investments than a single company’s stock.

Quote I’m not talking about expecting people to become Warren Buffet. I’m talking about teaching people, especially the young, how to make savvy financial decisions. Attribution Annamaria Lusardi

The results are especially troubling as methods of managing money have evolved, says Lusardi, a globally recognized expert on personal finance who joined Stanford in September as a senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) and as the director of the new Initiative for Financial Decision-Making. Workers now shoulder more of their retirement planning; consumers quickly and easily move money using their mobile phones; and investors make increasingly complex decisions.

“The world is changing really fast and we just expect people to have the skills to make financial decisions that have critical lifelong impacts,” says Lusardi, who is also a professor of finance (by courtesy) at Stanford Graduate School of Business.

High rates of financial illiteracy are also problematic, she says, given today’s heightened economic uncertainty and growing wealth inequality. Respondents who were young, less educated, female, or not employed scored the lowest. Black Americans and Hispanics were also among the least financially literate.

A Global Phenomenon

Financial illiteracy, it turns out, is pervasive around the world, according to a newly published global analysis in the Journal of Financial Literacy and Wellbeing . Whether they are in a Nordic country with strong education systems, like Finland, or in a Latin American country, like Peru, which experienced inflation in 1990 upwards of 10,000%, most people don’t understand how money works, says Lusardi. And just like in the United States, the least knowledgeable tend to be women, racial minorities, the least educated, and the unemployed.

Lusardi’s latest U.S. analysis — co-authored with Jialu Streeter , the executive director and a senior research scholar at SIEPR — is part of a special edition of the journal that includes analyses of 16 countries. Each study in the issue is based on the results of the “Big Three” questions that Lusardi and her longtime collaborator, economist Olivia Mitchell of the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, crafted 20 years ago.

Quote The continuous surprise is just how low financial literacy is in the United States and around the world. Attribution Annamaria Lusardi

In 2011, Lusardi oversaw and contributed to a similar series of country comparisons — which yielded similar results and appeared in the Journal of Pension Economics & Finance .

“Financial illiteracy has been and continues to be a global phenomenon,” says Lusardi, who is one of the founders and inaugural editors of the Journal of Financial Literacy and Wellbeing , published by Cambridge University Press .

Beyond measuring and analyzing financial literacy rates, Lusardi’s extensive research has found that people who understand basic financial concepts are better at managing money. They save more for retirement, make smarter investment decisions, and manage their debts more effectively. Lusardi’s latest study shows that people who are financially literate are more likely to have money on hand to weather at least the early stages of an economic shock like a pandemic.

Lusardi has also shown that people think they know more about personal finance than they actually do, which she says makes them even more vulnerable to poor decision-making.

Dollars and Sense

Stanford’s commitment to improving financial literacy is a key reason Lusardi says she joined The Farm. In addition to the Initiative for Financial Decision-Making — a collaboration between SIEPR, Stanford GSB, and the department of economics in the School of Humanities and Sciences — Lusardi continues to serve as academic director of the Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center , which she founded in 2011. Prior to Stanford, Lusardi was the University Professor of Economics and Accountancy at the George Washington University.

In Lusardi, Stanford gains a leader in establishing financial literacy as a specialty within the field of economics. Her contributions to the field began in 2004, when the University of Michigan’s closely watched Health and Retirement Study added the so-called Big Three to a module dedicated to financial literacy and retirement planning. Then, in 2009, the financial education arm of the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, which helps provide oversight of registered securities brokers and brokerage firms, began incorporating the same measures in its triennial survey of roughly 25,000 Americans.

Since then, other organizations, including central banks around the world, have integrated the Big Three into their respective assessments of household finances.

The underlying datasets in these surveys differ, but the results have uniformly shown that most people don’t understand how money, or financial systems broadly, functions, Lusardi says. In the U.S., this remained the case even after the Great Recession of 2008 and 2009 — the most severe economic downturn since the Great Depression — buffeted household finances.

“The continuous surprise is just how low financial literacy is in the United States and around the world,” says Lusardi, whose policy work includes advising the U.S. Treasury, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and chairing the Italian Financial Education Committee in charge of designing a national strategy for financial literacy.

The ABCs of Personal Finance

To Lusardi, the answer to financial illiteracy lies in providing people with a basic education on the ABCs of personal finance.

“Developing personal finance skills is as important as learning how to read and write,” says Lusardi, who has been teaching financial literacy to undergraduate and graduate students for more than a decade. In fact, her move to Stanford is rooted in her experience working with SIEPR’s Michael Boskin and John Shoven to organize the first annual Teaching Personal Finance Conference in 2022.

“I’m not talking about expecting people to become Warren Buffet,” she says. “I’m talking about teaching people, especially the young, how to make savvy financial decisions. For first-generation or low-income students, it often means talking about topics they seldom discuss with their parents.”

Even as personal finance education has become somewhat of a cottage industry, results are mixed at best. Instructors, Lusardi says, often lack training, and students tend to forget what they learn. In a 2014 journal publication , Lusardi and Mitchell noted that a lack of sufficient funding or teacher training in financial education is still an issue; in a follow-up paper published this past fall, however, they said there’s reason for optimism.

More than half of U.S. states, for example, have added personal finance instruction as a high school graduation requirement. Universities, including Stanford, are now offering personal finance courses. Employers, too, are recognizing that financial anxiety hurts employee productivity and are sponsoring personal finance lessons in the workplace.

“Financial literacy education is really accelerating,” Lusardi says. “We’re finally seeing things turn around and, to me, that’s a very positive result.”

A version of this story was originally published on November 28, 2023, by the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR).

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom .

Explore More

Flashback: raising capital in africa, it’s not just about the money, quick study: how to think like a venture capitalist, how ceos-in-waiting buy the companies they want to run, editor’s picks.

The Importance of Financial Literacy: Opening a New Field Annamaria Lusardi Olivia S. Mitchell

The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence Annamaria Lusardi Olivia S. Mitchell

Financial Literacy Around the World: An Overview Annamaria Lusardi Olivia S. Mitchell

May 22, 2023 When Is It Too Late to Give Up Control of Your Finances? Investors know the risks of making financial mistakes as they get older, but also want to oversee their money for as long as possible.

January 12, 2023 Love & Money: How to Talk About Big Decisions Together In this podcast episode, Myra Strober and Abby Davisson share a framework to help us communicate professional goals with those we care about most.

- Priorities for the GSB's Future

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Get Involved

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Reading Materials

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Personal Finances

- Filtering by:

Methodology: 2023 focus groups of Asian Americans

Pew Research Center created and designed this focus groups plan to understand the experiences and perspectives of Asians living with economic hardship in the United States.

1 in 10: Redefining the Asian American Dream (Short Film)

Of the 24 million Asians living in the United States, about 2.3 million live in poverty. This short film explores their diverse stories and experiences.

The Hardships and Dreams of Asian Americans Living in Poverty

About one-in-ten Asian Americans live in poverty. Pew Research Center conducted 18 focus groups in 12 languages to explore their stories and experiences.

Black Americans’ Views on Success in the U.S.

While Black adults define personal and financial success in different ways, most see these measures of success as major sources of pressure in their lives.

Parents, Young Adult Children and the Transition to Adulthood

Most U.S. young adults are at least mostly financially independent and happy with their parents’ involvement in their lives. Parent-child relationships are mostly strong.

Older Workers Are Growing in Number and Earning Higher Wages

Roughly one-in-five Americans ages 65 and older were employed in 2023 – nearly double the share of those who were working 35 years ago.

Key facts about the wealth of immigrant households during the COVID-19 pandemic

The median wealth of immigrant households increased by 42% from December 2019 to December 2021.

Tipping Culture in America: Public Sees a Changed Landscape

72% of U.S. adults say tipping is expected in more places today than it was five years ago. But even as Americans say they’re being asked to tip more often, only about a third say it’s extremely or very easy to know whether (34%) or how much (33%) to tip for various services.

Most Black adults in the U.S. are optimistic about their financial future

68% of Black adults in the U.S. say they do not have enough income to lead the kind of life they want, but a majority are optimistic that they will one day.

Majority of Americans aren’t confident in the safety and reliability of cryptocurrency

Concern among U.S. adults about cryptocurrency is broad, but some groups are more concerned than others. Only 18% are somewhat confident in crypto.

REFINE YOUR SELECTION

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

Theories of Personal Finance

- Personal Financial Planning

Research output : Chapter in Book/Report/Conference proceeding › Chapter › peer-review

This chapter provides an overview of the theories used in personal finance research, practice, and education. Personal finance encompasses financial planning, financial counseling, financial psychology, and financial therapy resulting in a diverse set of theoretical perspectives underpinning personal finance. This chapter highlights the theories unique to financial planning, financial counseling, financial psychology, and financial therapy, in addition to the theories that span across these areas. Lastly, this chapter addresses opportunities, challenges, and future directions for theoretical development within personal finance.

- Financial Counseling

- Financial Planning

- Financial Psychology

- Financial Therapy

- Personal Finance Theory

Access to Document

- 10.1515/9783110727692-005

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

Fingerprint

- Personal Finance Business & Economics 100%

- Financial Planning Business & Economics 42%

- Counseling Business & Economics 36%

- Psychology Business & Economics 32%

- Therapy Business & Economics 28%

- Future Directions Business & Economics 17%

- Education Business & Economics 10%

T1 - Theories of Personal Finance

AU - Asebedo, Sarah D.

N1 - Publisher Copyright: © 2022 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston.

PY - 2022/1/1

Y1 - 2022/1/1

N2 - This chapter provides an overview of the theories used in personal finance research, practice, and education. Personal finance encompasses financial planning, financial counseling, financial psychology, and financial therapy resulting in a diverse set of theoretical perspectives underpinning personal finance. This chapter highlights the theories unique to financial planning, financial counseling, financial psychology, and financial therapy, in addition to the theories that span across these areas. Lastly, this chapter addresses opportunities, challenges, and future directions for theoretical development within personal finance.

AB - This chapter provides an overview of the theories used in personal finance research, practice, and education. Personal finance encompasses financial planning, financial counseling, financial psychology, and financial therapy resulting in a diverse set of theoretical perspectives underpinning personal finance. This chapter highlights the theories unique to financial planning, financial counseling, financial psychology, and financial therapy, in addition to the theories that span across these areas. Lastly, this chapter addresses opportunities, challenges, and future directions for theoretical development within personal finance.

KW - Financial Counseling

KW - Financial Planning

KW - Financial Psychology

KW - Financial Therapy

KW - Personal Finance Theory

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=85134907968&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1515/9783110727692-005

DO - 10.1515/9783110727692-005

M3 - Chapter

AN - SCOPUS:85134907968

SN - 9783110727494

BT - De Gruyter Handbook of Personal Finance

PB - de Gruyter

Financial planning behaviour: a systematic literature review and new theory development

- Original Article

- Open access

- Published: 03 October 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Kingsley Hung Khai Yeo 1 ,

- Weng Marc Lim 1 , 2 , 3 &

- Kwang-Jing Yii 1

8353 Accesses

Explore all metrics

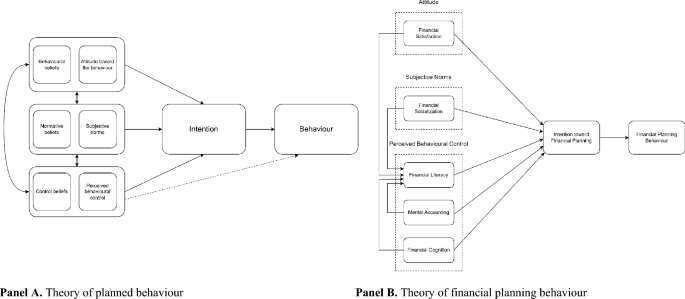

Financial resilience is founded on good financial planning behaviour. Contributing to theorisation efforts in this space, this study aims to develop a new theory that explains financial planning behaviour. Following an appraisal of theories, a systematic literature review of financial planning behaviour through the lens of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) is conducted using the SPAR-4-SLR protocol. Thirty relevant articles indexed in Scopus and Web of Science were identified and retrieved from Google Scholar. The content of these articles was analysed using the antecedents, decisions, and outcomes (ADO) and theories, contexts, and methods (TCM) frameworks to obtain a fundamental grasp of financial planning behaviour. The results provide insights into how the financial planning behaviour of an individual can be understood and shaped by substituting the original components of the TPB with relevant concepts from behavioural finance, and thus, leading to the establishment of the theory of financial planning behaviour, which posits that (a) financial satisfaction (attitude), (b) financial socialisation (subjective norms), and (c) financial literacy, mental accounting, and financial cognition (perceived behavioural controls) directly affect (d) the intention to adopt and indirectly shape, (e) the actual adoption of financial planning behaviour, which could manifest in six forms (i.e. adoption of cash flow, tax, investment, risk, estate, and retirement planning). The study contributes to establishing the theory of financial planning behaviour, which is an original theory that explains how different concepts in behavioural finance could be synthesised to parsimoniously explain financial planning behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Influence of Attitude to Money on Individuals’ Financial Well-Being

Sandra Castro-González, Sara Fernández-López, … David Rodeiro-Pazos

Financial Socialisation and Personal Financial Management Behaviour of Millennials in India: The Role of Attitude Towards Money and Financial Literacy

Conducting Research in Financial Planning

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Background of financial planning.

Personal financial planning is critical to maintaining a healthy financial status and fulfilling future financial needs (Mahapatra et al. 2019 ). In essence, personal financial planning is a process of managing personal wealth to obtain economic satisfaction (Kapoor et al. 2014 ). This encompasses six areas of financial planning, namely cash flow planning, tax planning, investment planning, risk management, estate planning, and retirement planning (Altfest 2004 ). Ideally, comprehensive financial planning should involve all six areas. However, the specific life stage of an individual, such as retirees, and life realities, such as retrenchment, may dictate the primary focus and/or relevance of these areas. For example, retirees might not be actively engaged in tax planning, and a retrenched worker might not be in a position to engage in investment planning. More importantly, personal financial planning is a profound concept that theoretically reflects and practically safeguards individuals’ financial resilience, and thus, it can be understood from two unique lenses: academic and practice.

From an academic perspective, the field of personal finance is interdisciplinary; it covers a wide range of areas, including economics, family studies, finance, information technology, psychology, and sociology (Schuchartdt et al. 2007 ). Different disciplines have varied theories that play a supporting role in understanding individuals’ financial behaviour and money management (Copur and Gutter 2019 ). However, the theories explaining personal finance are often borrowed rather than created, a situation that is common for emerging interdisciplinary fields (Murray and Evers 1989 ) such as personal finance (Lyons and Neelakantan 2008 ), which encompasses close to 250 publications only in Scopus by the end of 2022. Footnote 1

From a practice standpoint, Palmer et al. ( 2009 ) argued that it is necessary to develop financial planning for each individual that can deal with the uncertainty of the economic environment. Hanna and Lindamood ( 2010 ) echoed that personal financial planning can provide individuals sufficient economic benefits such as increasing wealth, preventing financial loss, and smooth consumption. Footnote 2 However, many individuals lack sufficient financial capability, skills, and knowledge to be able to effectively manage their personal finances (Chen and Volpe 1998 ).

Problems and importance of financial planning

Over time, the society is facing increasing challenges of high living expenses and various financial difficulties given the constant development of complexity in financial matters (Baker et al. 2023 ; Mahapatra et al. 2019 ). Individuals’ ability to manage their personal finances and financial affairs has been gaining attention across the world, wherein being financially healthy gets prioritised by individuals in their lives (e.g. changing investment approach and contributing more to retirement savings to hedge against inflation; Personal Capital 2022 ).

Birari and Patil ( 2014 ) state that individuals should practice and gain basic financial skills to manage their expenditures and acquire well-developed planning to avoid being in financial difficulties. Many factors may lead to irrational financial behaviours from individuals—for example, excess consumption, aggressive trading, lack of savings, and retirement planning. However, one of the major root causes that propels irrational financial behaviour as well as the many financial difficulties that people encounter is inarguably the lack of financial literacy (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development 2020 ).

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development ( 2013 ), financial literacy consists of financial knowledge, skill, attitude, awareness, and behaviour to make a rational financial decision and achieve individual financial well-being. In other words, financial literacy is the ability to utilise knowledge and skills to manage financial matters effectively (Pailella, 2016 ; Tavares et al. 2023 ).

Noteworthily, financial behaviour in individuals’ daily lives cannot be separated from financial literacy. Tan et al. ( 2011 ) state that the process of personal financial planning requires individuals to acquire not only cognitive ability but also financial literacy. According to Ali et al. ( 2014 ), financial literacy should be given serious attention from individuals because it is able to affect their welfare. Indeed, financial literacy has been proven to have a positive impact on financial planning. Specifically, individuals who lack financial literacy will often end up in debt (Lusardi and Tufano 2009 ) and will most likely increase their financial burden (Gathergood 2012 ). By having sufficient relevant information, individuals can analyse their financial situation and make decisions wisely.

Gaps and necessity to theorise financial planning behaviour

As mentioned, extant understanding of financial planning is mainly derived from borrowed theories. While this practice remains acceptable, it is important that new theories are developed to enrich understanding of financial planning, particularly from a behavioural perspective, as the issue of good or poor financial planning is dependent on the individual and his or her financial planning behaviour. With the maturity of the literature on financial planning, the time is now opportune to engage in new theory development (Kumar et al. 2022 ).

The need for theory development is further accentuated as there is a notable lack of theory development in explaining financial planning behaviour. Noteworthily, existing frameworks and models remain piecemeal and do not fully cover the whole spectrum of financial planning. After an appraisal of theories related to financial planning (“ Evolution of theories ” Section), the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) has been found to be the most suitable theory on parsimonious grounds (i.e. the capability and capacity of the theory’s core components to act as an organising frame) and its track record of theory spinoffs (e.g. the theory of behavioural control; Lim and Weissmann 2023 ) to explain an individual’s financial planning behaviour. Therefore, an integration of the respective antecedents, decisions, and outcomes (ADO) to form a new, holistic theory is required to document the complexity and the extent of considerations required to explain financial planning behaviour. Such an integration can and will be pursued via a systematic literature review (Lim et al. 2022a , b ).

Goals and contributions of this study

The goal of this study is to establish a formal theory to explain financial planning behaviour. To do so, a systematic literature review is conducted, wherein the SPAR-4-SLR protocol is adopted to guide the review process, whereas the antecedents, decisions, and outcomes (ADO) framework (Paul and Benito 2018 ) and the theories, contexts, and methods (TCM) framework (Paul et al. 2017 ) are adopted and integrated to analyse the findings of the review—a best practice demonstrated and recommended by Lim et al. ( 2021 ). In doing so, this study makes two noteworthy contributions.

From a theoretical perspective, the integrated framework contributes to integrate fragmented knowledge and reduce the production of isolated knowledge on financial planning behaviour. In addition, the framework clarifies the state of existing insights and empowers the discovery of new insights on financial planning behaviour. Certainly, insights gathered from a well-structured framework can provide a better start to add to existing knowledge and increase growth in the field (Kumar et al. 2019 ; Lim et al. 2022a , b ). More importantly, the nomological structure of the framework also enables the study to establish a new theory called the theory of financial planning behaviour , which can act as a multi-dimensional behavioural guideline that involves planning, developing, and assessing the operation of cash flow, tax efficiency, investment planning, risk management, estate planning, and retirement planning within an individual.

From a practical standpoint, the insights from the study are expected to contribute to future financial service professionals gaining advantages in the understanding of financial planning behaviour in catering to the future needs of the public. Additionally, policymakers would benefit from utilising the information to effectively provide financial education programs to enhance individuals’ financial well-being. Further implications for this study focusing on consumers and managers are also discussed towards the end of this study.

Theoretical background

Evolution of theories.

Over the past decades, several theories have been used by researchers on financial planning and the determining factors that influence it. The evolution of theories relating to financial planning is based on the concept of behavioural finance. These theories remain important in financial planning research (Asebedo 2022 ; Overton 2008 ). The most well-known theory related to behavioural finance is the TPB (Ajzen 1991 ). It has been widely used on different research topics to predict and explain individuals’ behaviour or the insufficient control of their behaviour (Ajzen 1985 , 1991 , 2002 ). Noteworthily, the TPB is an extension of the theory of reasoned action, which suggested that human behaviour is determined by the intention to perform a certain behaviour, whereby the intention can be determined by attitudes and subjective norms (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975 ).

In addition, Maslow’s ( 1943 ) hierarchy of needs has been used by Chieffe and Rakes ( 1999 ) to identify and rate the different segments of financial services best suited to each level of income group. The hierarchical approach of this theory provides a framework that explains different financial planning services related to each income group. According to Xiao and Noring ( 1994 ) and Xiao and Anderson ( 1997 ), the notion of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs clearly explains an individual’s financial needs in the form of a hierarchy. The framework of a hierarchical form of financial planning indicates that individuals would only strive for a high level of financial needs after a lower level of financial needs is met. It is recommended for individuals to fulfil their needs step by step to avoid facing financial difficulties.

Another theory that has been applied to financial planning is the life-cycle hypothesis (Modigliani and Brumberg 1954 ), which is an economic theory that explains an individual’s saving and spending behaviour throughout their lifetime. The theory also points out that individuals want to have smooth consumption by saving more if their income increases and borrowing more when their income ceases. Shefrin and Thaler ( 1988 ) state that individuals mentally place their assets into three different accounts, which are current income, current assets, and future income. According to Modigliani and Brumberg ( 1954 ), this theory assumes that individuals will fully utilise their utility for future consumption and aim to accumulate savings and resources for future consumption after retiring. The model explains that individuals’ consumption and saving decisions are formed from a life-cycle perspective. Such individuals will begin with low income when they start working, and their income will slowly increase until it reaches a peak level. Taking a behavioural enrichment (or behaviourally realistic) perspective of the life-cycle theory, Shefrin and Thaler ( 1988 ) state that the behavioural life-cycle hypothesis includes mental accounting, self-control, and framing, which represent three important behavioural features that are usually missing in the economic perspective of the traditional life-cycle theory. The authors mention that individuals use mental accounting to control their propensity to spend on their assets. The willingness to spend is usually related to their current income. According to Warneryd ( 1999 ), individuals usually have a specific method to mentally allocate their expenditures into different accounts. In addition, the marginal propensity to save and consume will be different in each account. According to Shefrin and Thaler ( 1988 ), individuals may face difficulties in controlling their spending, and thus, these individuals may form personal behavioural incentives and constraints. For example, individuals would possess the intention to save and create assets when constraints are available. They also explain that individuals’ preferences are not fixed but vary depending on the constantly changing economic environment and social stimuli (Duesenberry and Turvey 1950 ; Katona 1975 ). Furthermore, the life-cycle theory faces some challenges while explaining individuals’ behaviour, such as assuming that individuals will act rationally, be consistent, and make wise intertemporal choices throughout their lifetime (Deaton 2005 ). The life-cycle theory explains that individuals’ saving decisions are based on their preferences for either present or future consumption. The theory also assumes that individuals determine a desirable age of retirement and level of consumption to fully utilise their utility throughout their lifetime.

Prospect theory is an economic theory that assumes individuals treat losses and gains differently, showing how an individual decides among several choices that involve uncertainties (Kahneman and Tversky 1979 ). This theory explains that their decisions are easily affected by psychological factors and that they are logical decision-makers. However, when individuals decide on whether to purchase or not, they are most likely affected by their cognitive biases. The theory also postulates that making losses will cause a larger emotional impact on individuals rather than a comparable amount of gain. Thus, individuals will prefer choosing the option with perceived gains. For example, individuals would prefer the option of a sure gain instead of a riskier option with a chance of receiving nothing or making a loss. Hence, the theory summarises that individuals are mostly loss averse when they face several choices. Individuals are more sensitive towards losses and would most likely prefer avoiding losses and prefer sure wins. This can be explained by the fact that the emotional impact of losses on an individual is greater than an equivalent gain.

The financial capability model is another prominent theory. Financial capability, which has been gaining prominence across the globe, is defined as the capability and skills of individuals to make rational and effective judgements on managing their financial resources (Noctor et al. 1992 ). Nowadays, individuals have been urged to ensure that they acquire sufficient resources for their retirement and provide a financial safeguard for any sudden occurrence. According to Atkinson et al. ( 2007 ), the financial capability model has been studied and is related to individuals’ financial behaviour, attitude, and knowledge. The researchers identified five different components under the financial capability model: (1) making ends meet (managing personal financial resources, i.e. individuals who have acquired financial knowledge skill sets can finance their resources well and meet financial goals); (2) keeping track (managing money, i.e. planning and recording personal daily expenses to avoid overspending); (3) planning ahead (this helps individuals to be future oriented, i.e. always planning and managing their financial resources to be prepared for any financial uncertainties in the future); (4) choosing products (accumulating resources and managing different assets’ risks, i.e. making a rational decision in choosing financial products and diversifying risks); and (5) staying informed (being updated and studying financial matters in the current market and economy, i.e. individuals have to be eager to keep track on financial matters happening in the market, such as changes in the overnight policy rate (OPR) and stock market movement).

After a review of all the theories (Table 1 ), the TPB has been found to be the most suitable theory to serve as a foundational lens for a review on financial planning behaviour with the aim of establishing a new theory in this field. Unlike the other theories (e.g. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, life-cycle hypothesis including behavioural life-cycle hypothesis, financial capability model, prospect theory), the TPB is an adaptable yet parsimonious theory that has a track record of spinning off new theories (e.g. the theory of behavioural control; Lim and Weissmann 2023 ). Noteworthily, the TPB can be applied to financial behaviours (Bansal and Taylor 2002 ; East 1993 ; Xiao and Wu 2006 ), wherein the three antecedents of the TPB (attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control) are found to be associated with intention and contribute to financial behaviour (Shim et al. 2007 ; Xiao et al. 2007 ). Unlike other theories, the mediating effect of financial literacy, which provides an important lens to understand good and poor financial planning, can be applied to the TPB to explain an individual’s intention on financial behaviour. More importantly, it is necessary to understand how the TPB can further explain individuals’ behaviour before examining financial literacy through a behavioural approach. The theory assumes that intention is the best factor to predict an individual’s behaviour, which, in turn, is examined by attitude and social normative perceptions towards an individual’s behaviour (Montano and Kasprzyk 2015 ). Furthermore, individuals’ experiences normally affect their financial decision-making and the way they manage their personal finances. Therefore, financial literacy can be explained as an individual’s confidence and capability to make full use of their financial knowledge (Huston 2010 ) and manage financial matters (Lusardi and Mitchell 2014 ), which they would have perceived control over. In this regard, the theory can be applied to examine how the financial literacy process works on each individual. Moreover, Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2014 ) explain that the favour of financial literacy is more than that of financial capability, where individuals are responsible for their own financial decisions. Hence, financial literacy acknowledges the perceived control of individuals on their financial decisions. That being said, an individual will only show positive financial behaviour when they perceive the value of their behaviour based on their attitude. Therefore, financial behaviour will not be decided based on their financial knowledge but based on their attitude, which is the main component of this theory. In other words, the evaluation of financial knowledge will be better captured through the components of the TPB (e.g. perceived behavioural control), though conceptual contextualisation is necessary to better resonate with the financial planning behaviour of individuals. To aid this task, the next section provides a deeper discussion to understand the fundamental tenets of the TPB.

Theorisation of the theory of planned behaviour

According to Xiao ( 2008 ), the TPB is one of the best and most suitable theories related to financial behaviour that studies and predicts human behaviour. In essence, the TPB is an extension of the theory of reasoned action, which initially posits that attitude and subjective norms shape the intention to perform a behaviour, which, in turn, predicts the actual performance of that behaviour (Ajzen 1991 ). However, behavioural intention does not always translate into behavioural performance (Lim and Weissmann 2023 ), which is the main reason why the TPB was proposed to overcome the limitation of the theory of reasoned action, with the inclusion of perceived behavioural control in the TPB as a mechanism to recognise the volitional control that individuals possess in translating or not translating behavioural intention into behavioural performance (Ajzen 1991 , 2002 ).

Perceived behavioural control can be expressed as follows: Given an individual’s available resources and choices, how easy or hard it is to display a certain behaviour or act in a certain way? In this regard, the performance of an individual’s behaviour depends on his or her ability to act on said behaviour (Ajzen 1991 ). The TPB posits that the perceived control on certain behaviour will be greater when the individual has greater resources (social media, money, time) and choices (Lim and Weissmann 2023 ). Indeed, several researchers have found that perceived behavioural control has a positive relationship with intention and behaviour (Fu et al. 2006 ; Lee-Patridge and Ho 2003 ; Mathieson 1991 ; Shih and Fang 2004 ; Teo and Pok 2003 ).

Subjective norms can also be used to predict individual behavioural intention. As one of the original components of the theory of reasoned action, subjective norms refer to social influence and the social environment affecting an individual’s behavioural intention (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975 ). It is defined as an individual’s perception of the possibility that social agents approve or disapprove a behaviour (Ajzen 1991 ; Fishbein and Ajzen 1975 ). It focuses on everything around individuals, such as social networks, cultural norms, and group beliefs. This is known as a direct determinant of behavioural intention in the theory of reasoned action and the TPB. Through the lens of subjective norms, an individual is said to be willing to perform a certain behaviour even though he or she does not favour performing such behaviour while being under social pressure and social influence (Venkatesh and Davis 2000 ). Kuo and Dai ( 2012 ) state that as subjective norms become more positive, an individual’s behavioural intention to perform or act on a certain behaviour becomes more positive. Several studies have shown a significant relationship between subjective norms and intention (Chan and Lu 2004 ; May 2005 ; Teo and Pok 2003 ; Venkatesh and Davis 2000 ). Sharif and Naghavi’s ( 2020 ) research on family financial socialisation also finds that the behaviour of acquiring relevant norms and information on financial socialisation is associated with subjective norms. The informational subjective norms are known to predict perceived information. Ameliawati and Setiyani ( 2018 ) mention that subjective norms in the TPB represent financial socialisation. Their study describes subjective norms as financial socialisation to research the influence of financial management behaviour. In addition, the research of Jamal et al. ( 2015 ) on the effects of social influence and financial literacy on students’ saving behaviour used the TPB to develop the model. The author uses subjective norms to represent the social pressures influencing students’ intentions to save. It analyses the influences of parents and peers on the impact on the students’ saving behaviour. Hence, subjective norms have a significant effect on the intentions of individuals towards financial planning behaviour.

Attitude has been identified as a construct that guides an individual’s intention, which results in them acting on a particular behaviour. In essence, attitude can be defined as the evaluation of the positive and negative effects on individuals performing an act or behaviour (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975 ), and by extension, reflects the individual’s belief in certain behaviours or acts that contribute positively or negatively to a person’s life (Ajzen and Fishbein 2000 ). There are two components of attitude: the attitude towards a physical object (money, savings, pension) and the attitude towards behaviour or performing a certain act (using savings or money to practice financial planning). Keynes ( 2016 ) and Katona ( 1975 ) state that most individuals possess positive attitudes towards personal saving. Many studies have determined a significant relationship between attitudes and intention (Lu et al. 2003 ; Ramayah et al. 2020 ; Wu and Chen 2005 ). Therefore, attitude can be one of the most important factors to determine and predict human behaviour (Ajzen 1987 ). According to Xiao ( 2008 ), the more favourable the attitude of an individual on performing a behaviour, the easier it is for the individual to perform the behaviour and the stronger the behavioural intention. Further understanding of an individual’s attitude can help to predict their intention and behaviour.

Intention can be defined as an individual’s perception of performing a particular act or behaviour (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975 ). In this regard, intention is said to produce a direct effect on an individual’s behaviour as it signals the willingness of an individual to act (Ajzen 1991 ). The TPB explains that the degree of intentions that are converted into behaviour is determined by the amount of volitional control. Behaviour such as saving money is not considered as full volitional control given the lack of resources and opportunities able to affect the capability to perform the behaviour. While individuals can control their behaviour, their actual behaviour can easily be predicted by their intention accurately, but this does not prove that the measure of correlation is perfect between intention and behaviour (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975 ). Moreover, strong bias always exists in individuals, where they will overestimate the possibility of acting on desired behaviour and underestimate the possibility of acting on undesired behaviour. This can cause inconsistencies between intention and behaviour (performing an actual action) (Ajzen et al. 2004 ). Behaviour and intention will show high correlation whenever the interval time between them is low (Fishbein and Ajzen 1981 ). Yet, intention is known to change over time, and thus, if the interval between intention and behaviour is greater, the possibility of change in intention is higher (Ajzen 1985 ).

Behaviour refers to an observable response to a specific target (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975 ). In essence, the performance of a given behaviour is a direct outcome of the intention to perform that behaviour as well as an indirect result of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control (Ajzen 1991 ), as discussed above.

The TPB has been widely used in different fields of research over the past decades: medicine (Hagger and Chatzisarantis 2009 ; McEachan et al. 2011 ), marketing and advertising (King et al. 2008 ; Yaghoubi and Bahmani 2010 ), tourism and hospitality (Han 2015 ; Quintal et al. 2010 ), information science (Lee 2009 ; Shih and Fang 2004 ), and, last but not least, human behaviour (Kobbeltvedt and Wolff 2009 ; Perugini and Bagozzi 2001 ). All the studies listed above have concluded on the positive and significant effect of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control on an individual’s intention to act on behaviour. In the financial context, Shih and Fang ( 2004 ) apply the TPB to an individual’s financial decisions regarding internet banking. The study concludes that the TPB can be successfully applied to understand an individual’s intention to use internet banking. Lau et al. ( 2001 ) and Lee ( 2009 ) also apply the TPB to study investors’ intentions on online banking and trading online. To provide a more accurate account for financial planning behaviour, a systematic literature review is conducted and reported in the next sections.

Methodology

Study approach: systematic literature review.

This study conducts a systematic literature review to develop comprehensive insights into financial planning behaviour based on the TPB. As mentioned above, the TPB is the extension of the theory of reasoned action, and it strongly posits that an individual’s behaviour is determined by the three factors (attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control) and is backed by their behavioural intention (Ajzen 1991 ).

A systematic literature review is known as a ‘research synthesis’, an extensive process of summarising primary research based on an explicit research question, where it attempts to identify, select, synthesise, and assess all the evidence by providing answers to the research question (Donthu et al. 2021 ; Lim et al. 2022a , b ). In this regard, systematic literature reviews not only summarise and synthesise existing knowledge but also facilitate knowledge creation (Kraus et al. 2022 ; Mukherjee et al. 2022 ). Moreover, systematic literature reviews gathered eligible and pertinent evidence based on a preset criterion to answer a specific research question, and thus, a transparent and explicit systematic methodology can be used for systematic literature reviews to analyse and reduce biases (Harris et al. 2014 ; Paul et al. 2021 ).

Systematic literature reviews can be conducted through various methods. Generally, systematic literature reviews can be domain-based, theory-based, and method-based (Palmatier et al. 2017 ; Paul et al. 2021 ). In this study, a theory-based review was used for new theory development. Specifically, the theory-based review is chosen over the other approaches because it serves the purpose of analysing a specific role played by a theory in a given field. One of the examples given by Hassan et al. ( 2015 ) is the role of the TPB in the field of consumer behaviour. In this study, the TPB was applied to financial planning behaviour.

Study procedure: SPAR-4-SLR

Few protocols exist for systematic literature reviews. The most common protocol used by researchers in conducting systematic literature reviews is the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) by Moher et al. ( 2009 ). PRISMA is a comprehensive protocol that helps researchers to develop systematic literature reviews. It gathers and reports decisions that researchers have justified from their reviews. However, an uprising protocol was proposed by Paul et al. ( 2021 ) to address the existing limitations of PRISMA, namely the Scientific Procedures and Rationales for Systematic Literature Reviews protocol or the SPAR-4-SLR protocol. As shown in Fig. 1 , the protocol consists of three stages and six sub-stages, followed by sequences.

Assembling This stage constitutes the (1a) identification and (1b) acquisition of literature that is yet to be synthesised.

Arranging This stage entails the (2a) organisation and (2b) purification of literature in the stage of being synthesised.

Assessing This stage reflects the (3a) evaluation and (3b) reporting of literature that has been synthesised.

Review process

Systematic reviews assembling, arranging, and assessing the literature according to the SPAR-4-SLR protocol are expected to: (1) provide significant insights and (2) stimulate nuanced agendas for knowledge advancement in the review domain. Substantially, by providing such significant insights and agendas using the SPAR-4-SLR protocol, (1) the review is comprehensively justified for logical and pragmatic reasons, and (2) each stage and sub-stage is reported with full transparency.

The researchers begin with assembling in the (1a) identification stage, identifying the research domain and research question. The research domain of this study is behavioural finance with a specific focus on financial planning. The research question of this study is ‘How can the TPB be contextualised to develop a theory of financial planning behaviour?’ Thus, academic articles selected should focus on financial planning (i.e. the focus of this review) and the TPB (i.e. the theory contextualised for this review). The source quality was established based on Scopus or Web of Science indexing in line with Paul et al. ( 2021 ). Moving on to the (1b) acquisition stage, the search mechanism will rely on Google Scholar, which is free and can be easily accessed for article search. Footnote 3 The search period will begin from 2000 to 2020 (20 years) as most articles on the TPB and financial planning behaviour started to appear in the early 2000s. Related articles searched between these years are included in this study. The search was conducted multiple times with different keywords based on American and British spelling as well as different combinations: (1) ‘financial planning’ + ‘theory of planned behavior’, (2) ‘financial planning’ + ‘theory of planned behaviour’, (3) ‘personal financial planning’ + ‘theory of planned behavior’, and (4) ‘personal financial planning’ + ‘theory of planned behaviour’. Footnote 4

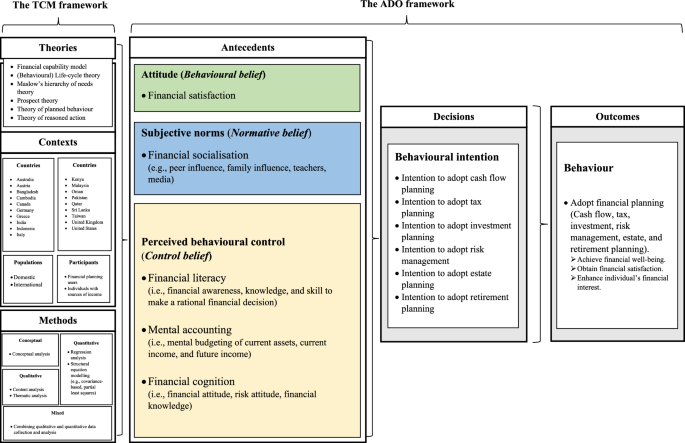

Next, the researchers move onto arranging in the (2a) organisation stage, wherein the organising code for this study is ADO and TCM, which rely on the suggested frameworks used, the ADO framework (Paul and Benito 2018 ; Pansari and Kumar 2017 ) and the TCM framework (Paul et al. 2017 ). Refer to Fig. 2 for the overview of ADO on the insights of the TPB on financial planning behaviour and its supporting TCM. In the (2b) purification stage, the articles gathered are filtered in this process. The researchers decided which articles to include and exclude from the study. The criteria to exclude articles in this stage include duplicate articles, irrelevant articles, inaccessible articles, and lastly, non-journal-title articles; 41 articles were excluded based on the criteria, and 30 articles proceeded to the next stage.

The state of the art of the antecedents, decisions, and outcomes of financial planning behaviour and its supporting theories, contexts, and methods

Finally, the researchers move into assessing in the (3a) evaluation stage, which involves the analysis and the agenda proposal. The study utilised content analysis, a methodical approach for coding and interpreting textual data from the selected articles to draw meaningful conclusions (Kraus et al. 2022 ). This systematic technique, which was executed by one author (a doctoral scholar) and cross-validated by another author (a senior academic) with an intercoder reliability of ± 95% and differences clarified and resolved, enabled the researchers to identify, categorise, and analyse patterns within the text, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter (Patil et al. 2022 ). The theory development and future research agenda were formulated through conceptual extrapolation and sensemaking (i.e. scanning, sensing, and substantiating) (Lim and Kumar 2023 ). This process entailed critically examining the existing theories, extracting key concepts, and extrapolating these to propose new research directions. Thus, this study provided a roadmap for future studies, fostering further evolution in the field of financial planning behaviour. In the (3b) reporting stage, the reporting conventions used include figures, tables, and words. No ethical approval is required since the review is based on accessible secondary data (journal articles), which can be accessed by anyone with subscription (Lim et al. 2022a , b ).

Profile of TPB and financial planning behaviour research

The systematic review of 30 articles covered different insights into the existing research of the TPB and financial planning behaviour, covering the six components of financial planning (i.e. cash flow planning, tax planning, risk management, investment planning, estate planning, and retirement planning) (Fig. 2 ). Appendix 1 summarises the articles in Appendix 2 based on the approaches of Paul and Mas ( 2019 ) and Harmeling et al. ( 2016 ). The articles are classified based on author citations, years, number of citations, methods, sample, related financial planning components and variables, and lastly findings. The findings of each article briefly explained how the construct of the TPB is a predictor or shows a significant effect on financial planning behaviour.

Based on this review, which begins from 2000 to 2020, the past two decades of research in the field of behavioural economics (later known as behavioural finance) have been on continuously identifying and explaining an individual's finances from an extended social science perspective, which includes psychology and sociology. Behavioural finance can be defined as the field of study where psychological factors affect an individual's financial behaviour (Shiller 2003 ). The combination of the TPB and financial planning has proven to be impactful with over 3000 citations among the 30 articles. The articles utilised four different methods: the quantitative approach ( n = 24), the qualitative approach ( n = 3), the mixed method approach ( n = 1), and the conceptual approach ( n = 2).

Lastly, the TPB (i.e. attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and behavioural intention) has been found to be a good predictor of financial planning behaviour (i.e. cash flow planning, tax planning, risk management, investment planning, estate planning, and retirement planning) and possesses positive relationships with each component of financial planning. For example, the TPB was found to be positively related to the intention to invest, mental budgeting behavioural intention, influencing savings and investment, and the intention to prevent risky credit behaviour, among others.

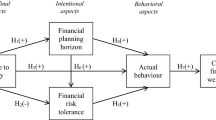

Contextualising the TPB for financial planning behaviour

Table 2 and Fig. 3 show the contextualisation of the TPB for financial planning behaviour, leading to the establishment of the theory of financial planning behaviour. Pansari and Kumar ( 2017 ) suggest the use of such a table to compare and explain each construct of the framework. The table, which leverages the findings from the review depicted in Fig. 2 , clearly illustrates how the TPB can be contextualised to explain financial planning behaviour. Attitude can manifest as financial satisfaction, wherein individuals who are dissatisfied, not fully satisfied, or wish to be more satisfied with their financial state will develop a positive disposition towards financial planning. Subjective norms can manifest as financial socialisation, wherein individuals learn about societal expectations of financial planning when they socialise with others (e.g. family, friends, work colleagues). Perceived behavioural control can manifest as financial literacy, mental accounting, and financial cognition, wherein the effect of financial satisfaction and financial socialisation is mediated through financial literacy, which may be shaped by the capability to perform mental accounting and the capacity for financial cognition. These factors can collectively shape the individual's intention to engage in financial planning, which, in turn, motivates the actual behaviour of engaging in financial planning, which can take six forms, namely cash flow planning, tax planning, investment planning, risk management, estate planning, and retirement planning.

Visual representation of contextualising the TPB into the theory of financial planning behaviour

Reflections and ways forward

Behavioural decision-making has been one of the most significant research interests for economists over the past decades. Past researchers (Xiao and Wu 2006 ; East 1993 ; Bansal and Taylor 2002 ) have applied the TPB to financial behaviour. The three antecedents of the TPB (attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control) were found to be associated with the intention of an individual and contribute to financial behaviour (Shim et al. 2007 ; Xiao et al. 2007 ). Unlike other theories, the mediating effect of financial literacy can be applied to the TPB to explain financial behaviour intentions. The variables of mental accounting and financial cognition were not frequently used by the researchers in the study of financial planning, while in this study, both variables are positioned as relevant components of perceived behavioural control in the TPB.

The concept of mental accounting has been extensively studied in the research area of psychology on financial decisions (Mahapatra and Mishra 2020 ). However, past studies on mental accounting in financial planning are insufficient. The formation and influences of mental accounting as a cognitive process—which consists of the concepts of current income, current assets, and future income as well as mental budgeting—play an important role in the personal financial planning process to each individual. It serves as a guideline in the process of financial planning and provides useful insights. Budgeting plays a key role in managing the financial life of an individual in terms of short-term (e.g. prioritising spending in different categories) and long-term (e.g. setting aside money for investment and future use) financial planning.

Previous research has applied mental accounting with the theory of the behavioural life-cycle model. Shefrin and Thaler ( 1988 ) mentioned that people mentally divide their incomes into current income, current assets, and future income, where the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) for each account is relatively different. Mental accounting is helpful and crucial for individuals to plan for their future financial needs so that they can deal with any unexpected financial difficulties in the future. However, there are still gaps to fill to come out with optimal financial decisions. Therefore, given the need of individuals for personal financial planning, it is necessary to apply mental accounting to each individual by determining their spending and saving tendencies.

Moreover, the 2008 global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic have also taught the world painful lessons; the need for financial literacy and cash flow control has been highlighted and considered by the public. A study conducted by Shahrabani ( 2012 ) on the effect of financial literacy and intention to control personal budget concludes that individuals with high levels of financial knowledge and literacy can influence the intention to have budgetary control. The study shows a positive relationship between the intention to budget and financial knowledge. Selvadurai and Siraj ( 2018 ) study financial literacy education and retirement planning in Malaysia. The authors mention that mental accounting is closely related to financial literacy education. Financial literacy can enhance mental accounting as it affects the behaviour of an individual in planning their savings and expenditure. In particular, individuals who acquire financial literacy education are most likely able to control their expenditure by not spending more than their income, which results in having sufficient savings in the long run. The relationship between mental accounting and financial literacy has been proven to be indispensable.