Yearly paid plans are up to 65% off for the spring sale. Limited time only! 🌸

- Form Builder

- Survey Maker

- AI Form Generator

- AI Survey Tool

- AI Quiz Maker

- Store Builder

- WordPress Plugin

HubSpot CRM

Google Sheets

Google Analytics

Microsoft Excel

- Popular Forms

- Job Application Form Template

- Rental Application Form Template

- Hotel Accommodation Form Template

- Online Registration Form Template

- Employment Application Form Template

- Application Forms

- Booking Forms

- Consent Forms

- Contact Forms

- Donation Forms

- Customer Satisfaction Surveys

- Employee Satisfaction Surveys

- Evaluation Surveys

- Feedback Surveys

- Market Research Surveys

- Personality Quiz Template

- Geography Quiz Template

- Math Quiz Template

- Science Quiz Template

- Vocabulary Quiz Template

Try without registration Quick Start

Read engaging stories, how-to guides, learn about forms.app features.

Inspirational ready-to-use templates for getting started fast and powerful.

Spot-on guides on how to use forms.app and make the most out of it.

See the technical measures we take and learn how we keep your data safe and secure.

- Integrations

- Help Center

- Sign In Sign Up Free

- 20 Amazing health survey questions for questionnaires

Surveys are an excellent approach to acquiring data that isn't revealed by lab results or spoken in casual conversation. Patients can be reluctant to offer you personal feedback, but surveys allow them to do so confidently. Online surveys encourage communication with the patient by collecting opinions from clients and employees.

The health assessment of a person plays a significant role in determining and assessing their health status . Healthcare organizations frequently use health assessment survey questions to gather patient data more effectively, quickly, and conveniently. This article will explain a health survey, how you can create it quickly and promptly on forms.app , and examples of health survey questions you can use in your excellent survey.

- What is a health survey?

Health surveys are a crucial and practical decision-making tool when creating a health plan. Health studies provide detailed information about the chronic illnesses that patients have, as well as about patient perspectives on health trends, way of life, and use of healthcare services .

A patient satisfaction survey is a collection of questions designed to get feedback from patients and gauge their satisfaction with the service and quality of their healthcare provider . The patient satisfaction survey questionnaire assists in identifying critical indicators for patient care that aid medical institutions in understanding the quality of treatment offered and potential service issues.

- How to write better questions in your health survey

The proper application of a health survey is its most crucial component. The timing is critical to health surveys. Patients in the hospital typically need a certain amount of uninterrupted time to complete the survey questions without interruption; instead, they should complete the surveys after their visit. Here are some tips on how to create a good health survey question:

1. Ask clear questions

In general, people avoid solving long and obscure surveys. Patients want to understand the questions clearly when sharing their views and ideas. If you keep the health survey questions clear and short , you can increase the number of respondents and get more effective results. To make your questions clear, you can add descriptions under question titles.

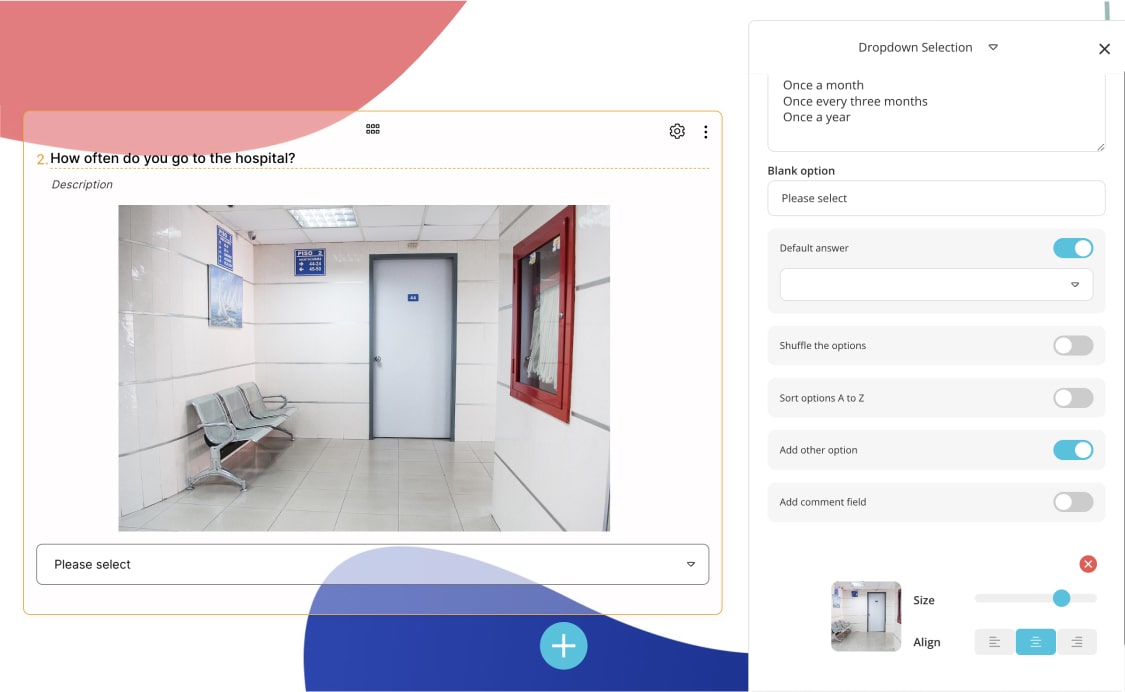

2. Use visual power

The use of visuals in surveys positively affects the number of participants. By using some images in health surveys, you can enable patients to respond more quickly and accurately . For example, in a health survey question asking the patient which region he has pain, you can make it easier for patients to answer by using visuals.

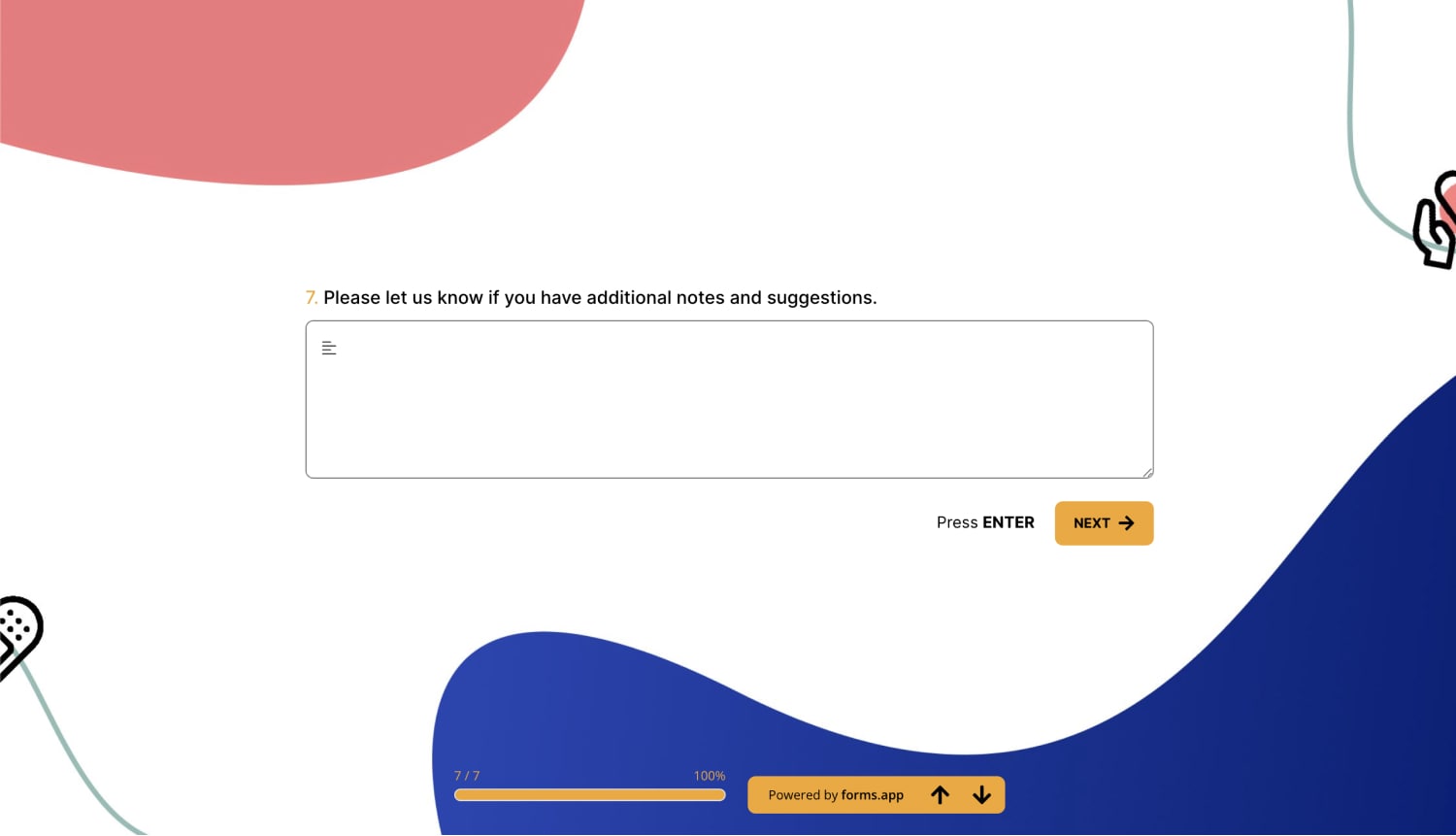

3. Reserve a section in the questionnaire for patient suggestions

Opinions and suggestions of patients are essential to improving the treatment, health, and hospital systems. In the last part of the questionnaire, you can ask the patients to present their opinions and suggestions . In this way, the patient can feel more important , and you can reach the patient's views more effectively .

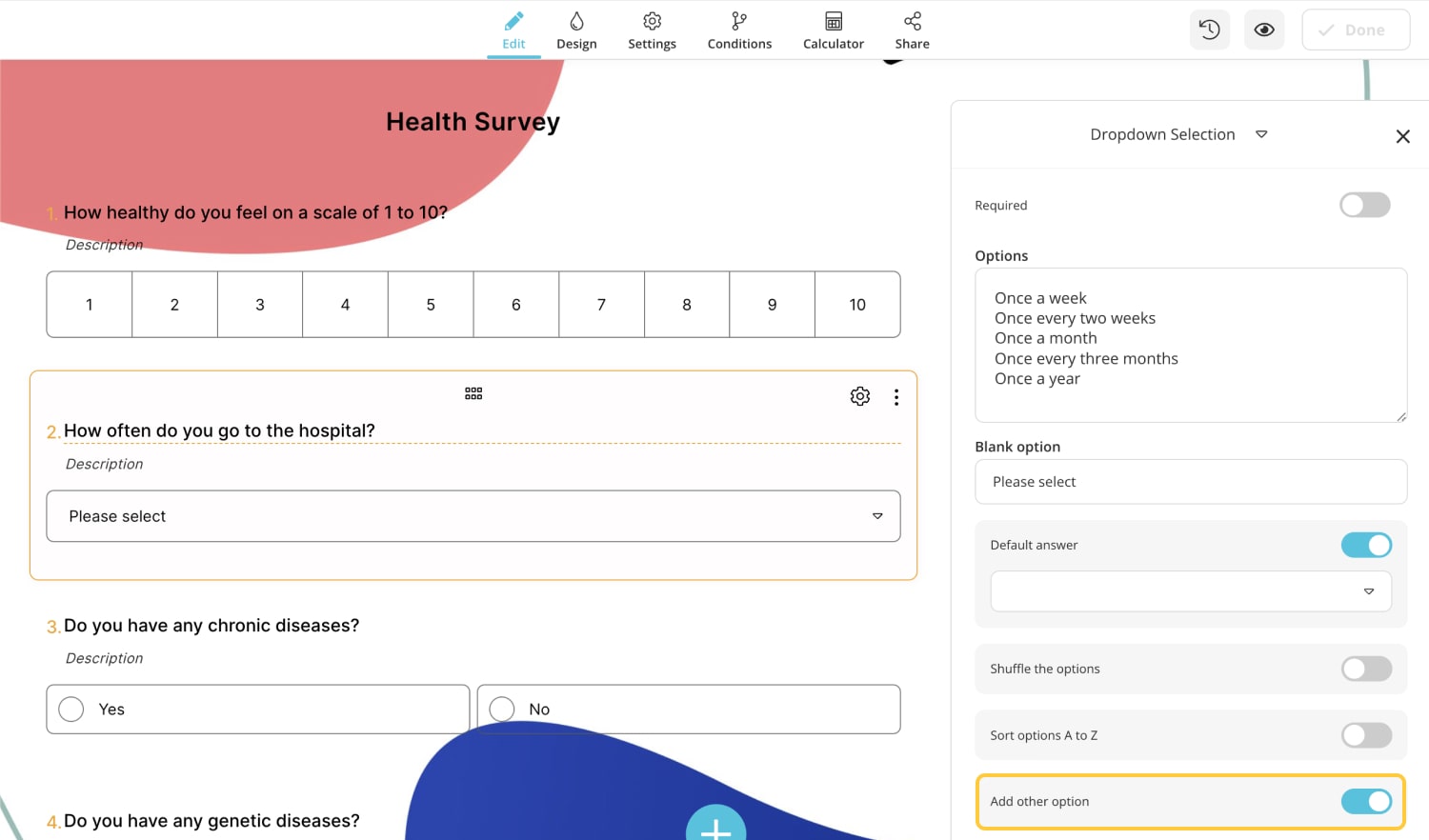

4. Include the 'other' option in the answer choices.

There may not be an option suitable for the patients in the answer choice. This may cause the patient to leave the question blank or give an incorrect answer. In this case, you can ask the patient to write their reply by adding the ' other ' option to the options .

- 20 excellent health survey question examples

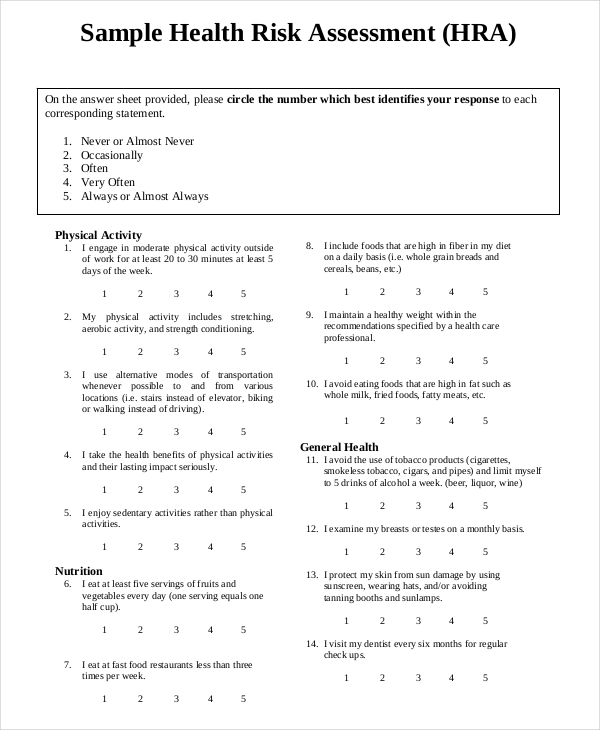

A health survey question asks respondents about their general health and condition. Researchers can use these questions to gather data about a patient's public health, disease risk factors, feelings about their medical care, and other relevant information .

A health survey effectively gathers information from a large population or a specific target group. You can collect critical data from the patient by asking the appropriate questions at the right time. Below, this article has shared 20 Great health care survey question examples for surveys:

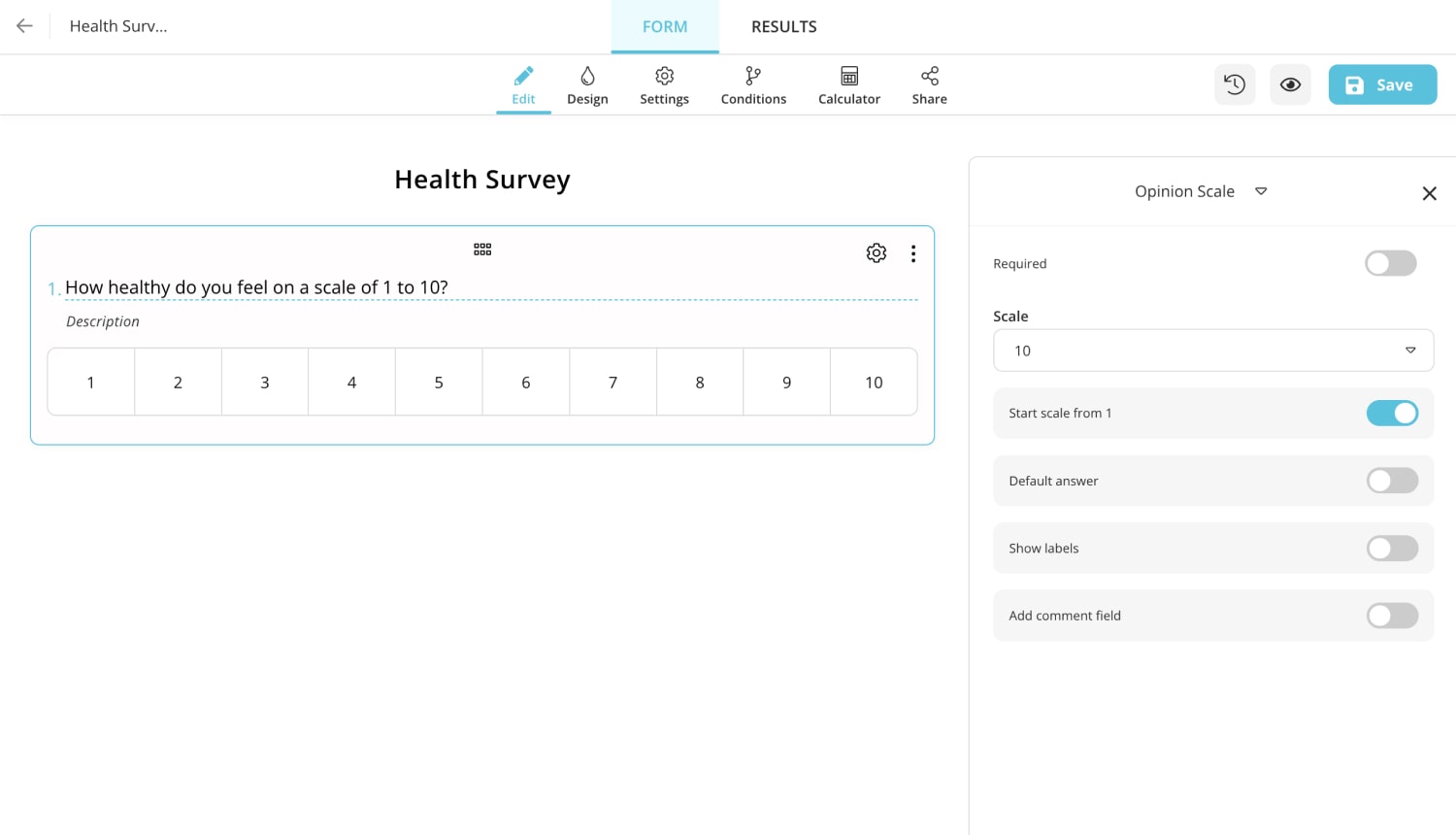

1 - How healthy do you feel on a scale of 1 to 10?

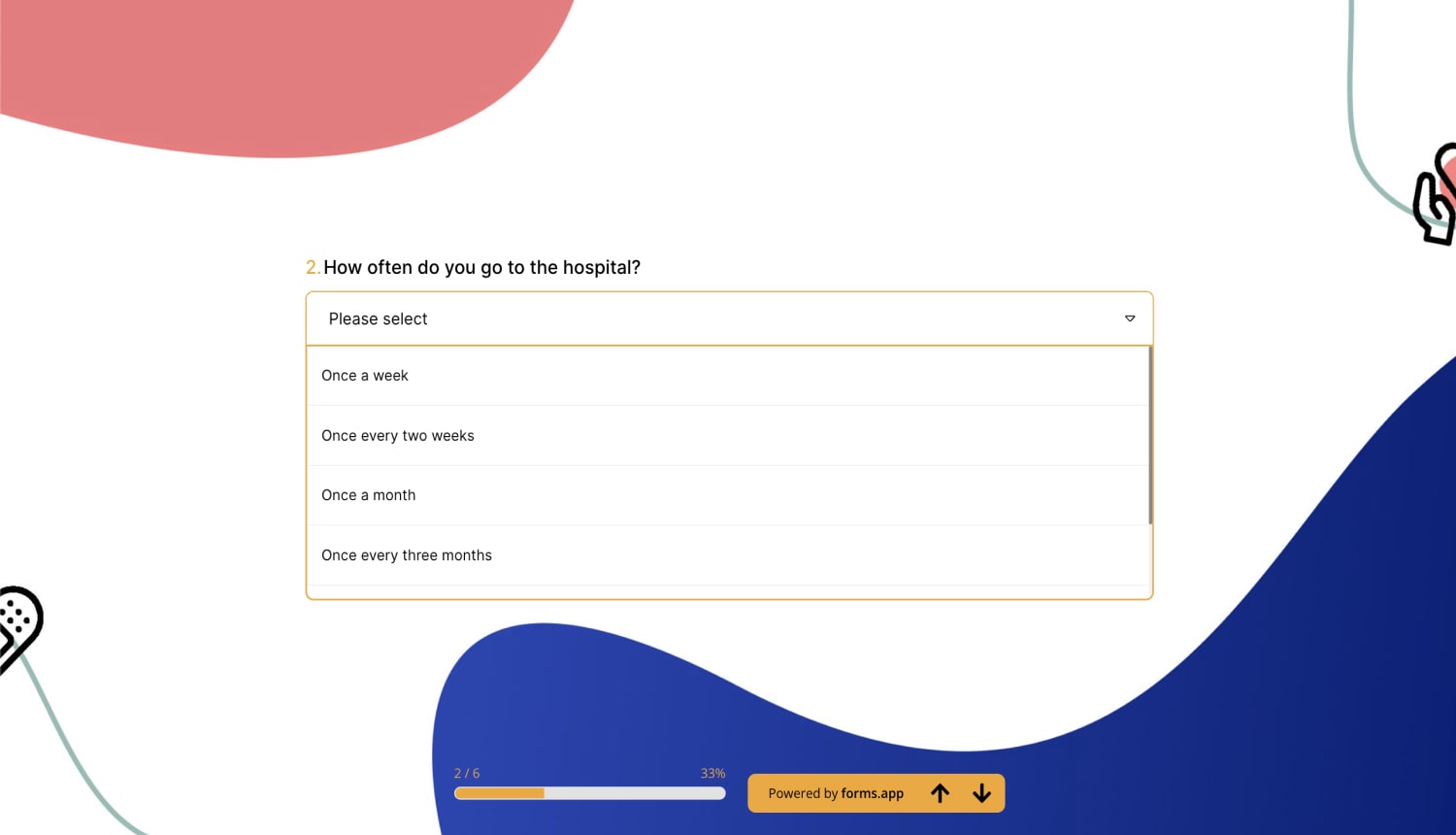

2 - How often do you go to the hospital?

a) Once a week

b) Once every two weeks

c) Once a month

d) Once every three months

e) Once a year

f) Other (Please write your answer)

3 - Do you have any chronic diseases?

a) Yes

b) No

4 - Do you have any genetic diseases?

a) Diabetes

b) High blood pressure

c) Huntington

d) Thalassemia

e) Hemophilia

f) Other (Please specify)

5 - Do you regularly use alcohol and/or drugs?

a) Yes to both

b) Only to drugs

c) Only to alcohol

d) No

6 - How frequently do you get your health checkup?

a) Once in 2 months

b) Once in 6 months

c) Once a year

d) Only when needed

e) Never get it done

7 - Does anyone in your family members have a hereditary disease?

a) Yes

b) No

8 - How often do you exercise?

a) Every day

b) Once in two days

c) Once a week

d) Once a month

e) Never

9 - Have you had an allergic reaction or received treatment for it?

a) Yes, I did. I also received treatment.

b) I had it but did not receive treatment

c) I've never had one.

10 - What level of function can you carry out routine tasks?

a) Excellent level

b) Good level

c) Intermediate level

d) Bad level

e) Terrible level

11 - Have you experienced depression or psychological distress in the last four weeks?

a) Yes very much

b) Sometimes

c) Never

12 - How much have your emotional issues impacted your interactions with friends and family over the past four weeks?

a) It didn't affect me at all

b) Very little

c) Moderate

d) Quite a few

e) Too much

13 - How would you rate your treatment process?

a) Wonderful

b) Above average

c) Average

d) Below average

e) Very poor

14 - Do you use any medication regularly?

15 - What various medications have you used over the last 24 hours?

16 - How was the doctor's attitude towards you on a scale of 1 to 10?

17 - How do you rate the local hospitals in your area?

a) Excellent

b) Good

d) Poor

18 - Please rate (1-10) your agreement with the following: Health insurance is affordable.

19 - Which of the following have you experienced pain in the past month?

a) Heart

b) Kidney

c) Lung

d) Stomach

e) Other (Please specify)

20 - Do you recommend this health facility to your family and friends?

a) Definitely yes

b) Yes

c) No

d) Definitely not

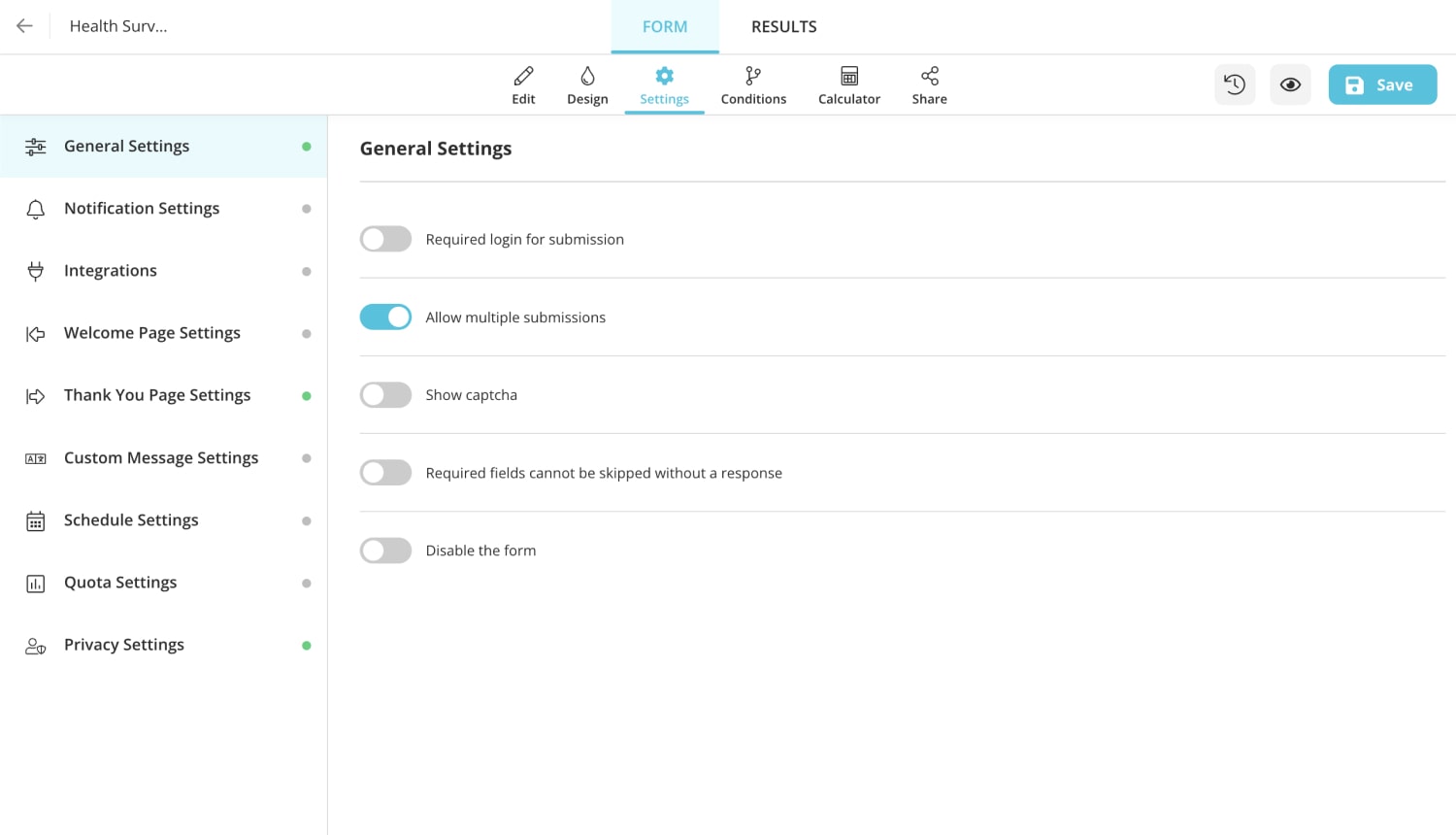

- How to create a health survey on forms.app

forms.app is one of the best survey makers . It offers its users a wide variety of ready-to-use forms, surveys, and quizzes. The free template for health survey on forms.app is easy to use. It will be explained step by step how to use the forms.app to create the health questionnaire.

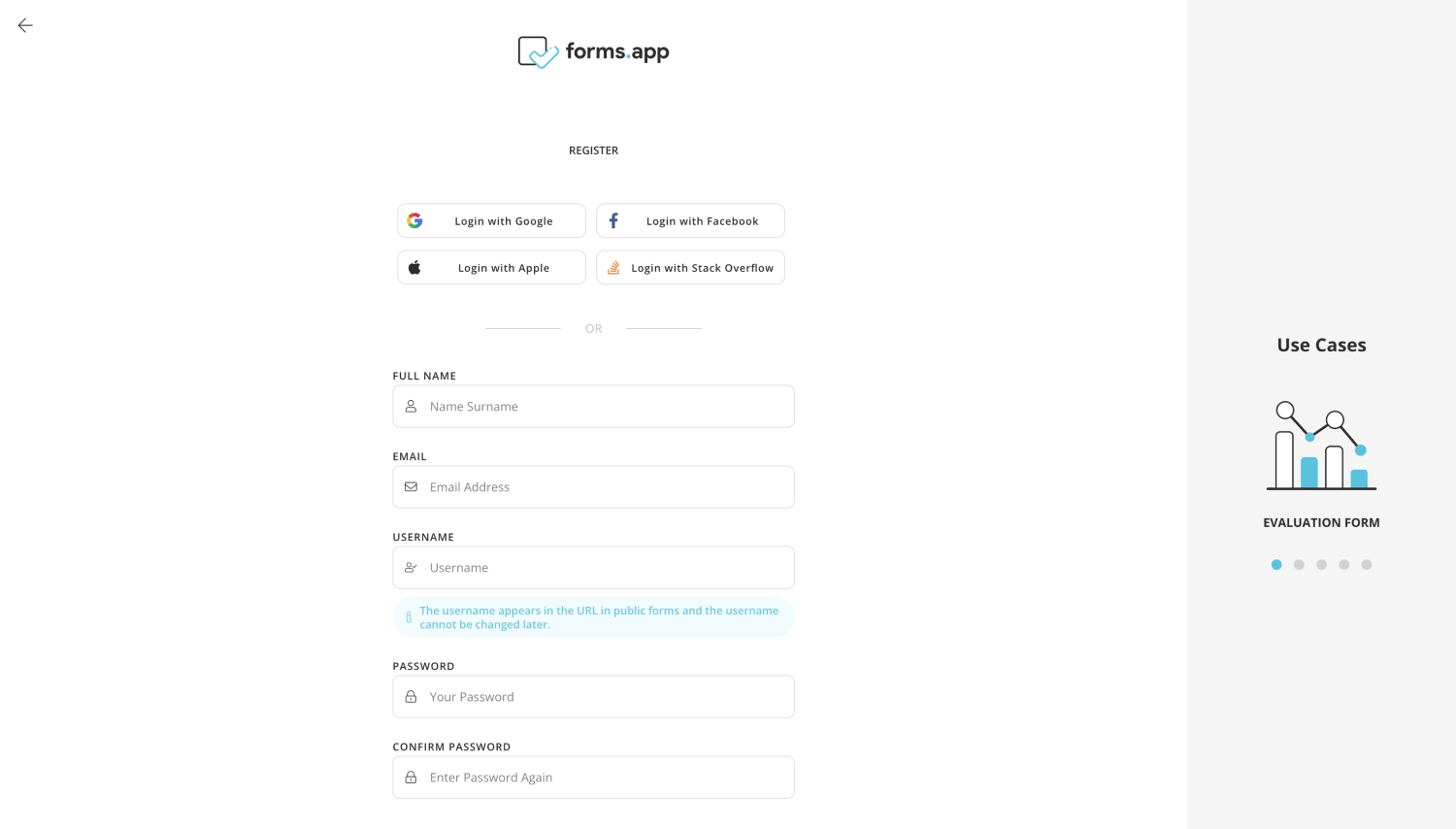

1 - Sign up or log in to forms.app : For health surveys that you can create quickly and easily on forms.app, you must first log in to forms.app. You can register for free and quickly if you do not have an existing account.

2 - Choose a sample or start from scratch : On forms.app, you can select from a wide selection of templates covering a wide range of topics. You can edit an existing survey template on forms.app by selecting it and making the necessary changes, or you can start with a blank form and add fields as you see fit.

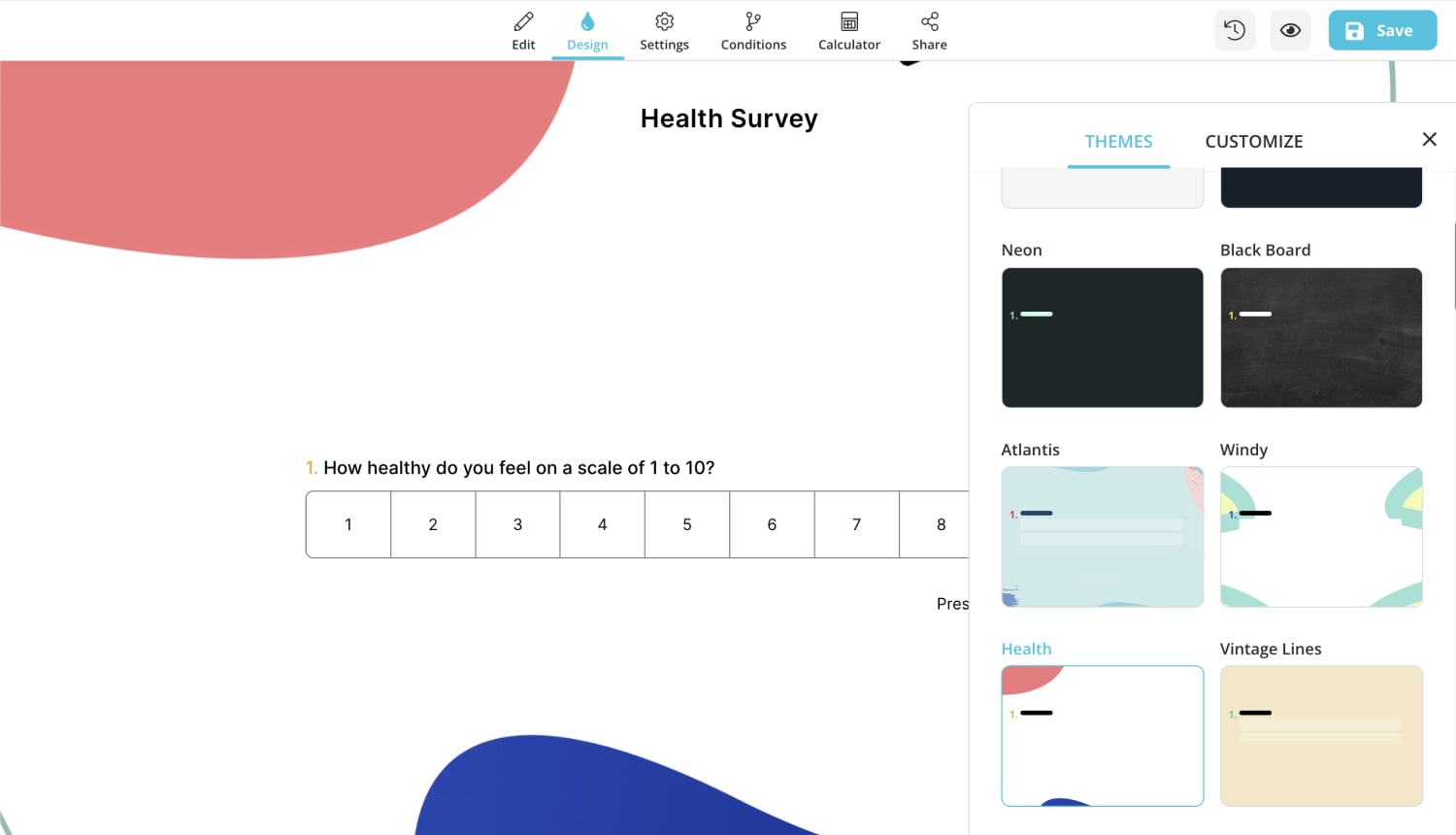

3 - Select a theme or manually customize your form : You can also select a different theme from the many options offered by form.app.

4 - Complete the settings : Finish the settings, and save. After completing all the sets, the test is ready to use! It can be used to save and share with attendees.

Free health survey templates

A hospital or health center can find patients' feedback on their care and services by conducting a health survey. You can quickly and efficiently get the answers from the patients using the forms.app questionnaire you created. This survey tool enables medical professionals to pinpoint risk factors in the neighborhood surrounding hospitals or healthcare facilities, including prevalent health practices like drug usage, smoking, poor dietary choices, and inactivity .

Hospitals can determine whether patients' diagnoses are accurate and whether their medications are enough to treat them. These surveys will undoubtedly move more quickly and contribute to improving health services if they ask each patient the right questions. You can get started using the free templates below.

Mental Health Quiz

Mental Health Evaluation Form

Telemental Health Consent Form Template

Sena is a content writer at forms.app. She likes to read and write articles on different topics. Sena also likes to learn about different cultures and travel. She likes to study and learn different languages. Her specialty is linguistics, surveys, survey questions, and sampling methods.

- Form Features

- Data Collection

Table of Contents

Related posts.

55+ excellent in-app survey questions to ask in your software

Şeyma Beyazçiçek

55 Amazing parent survey questions for your next questionnaire

Defne Çobanoğlu

Market research surveys: Types and examples

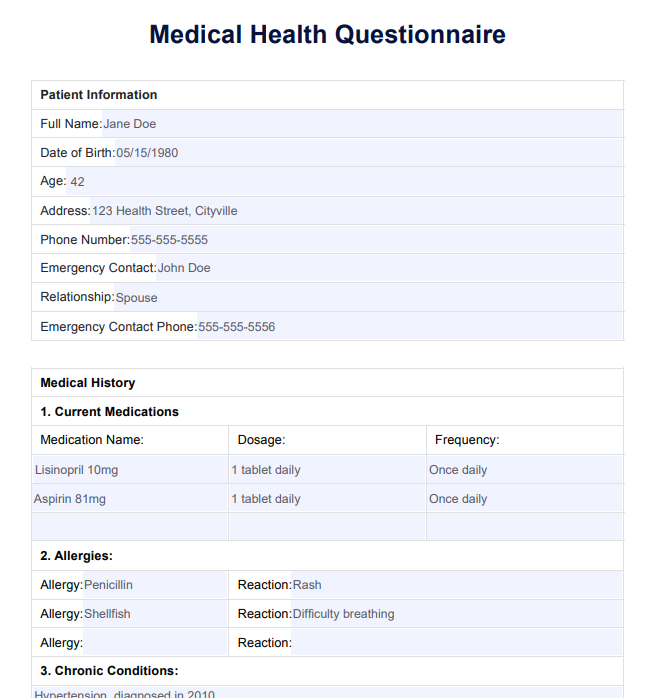

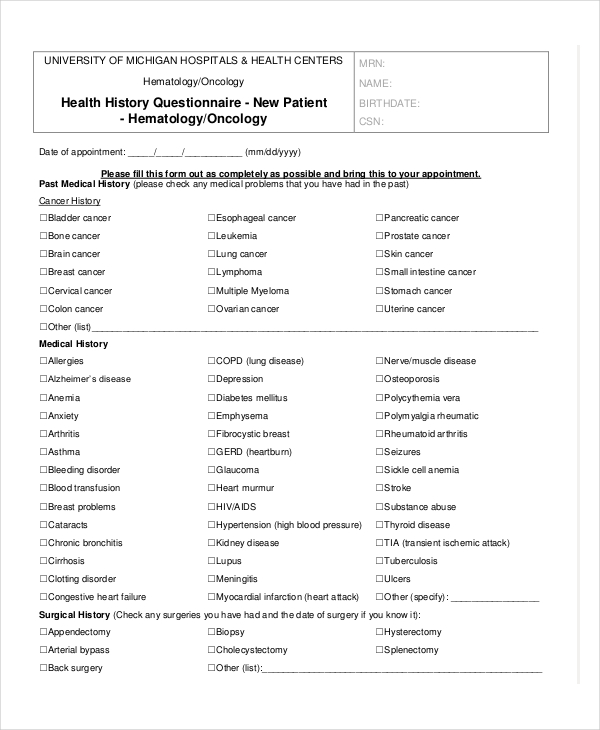

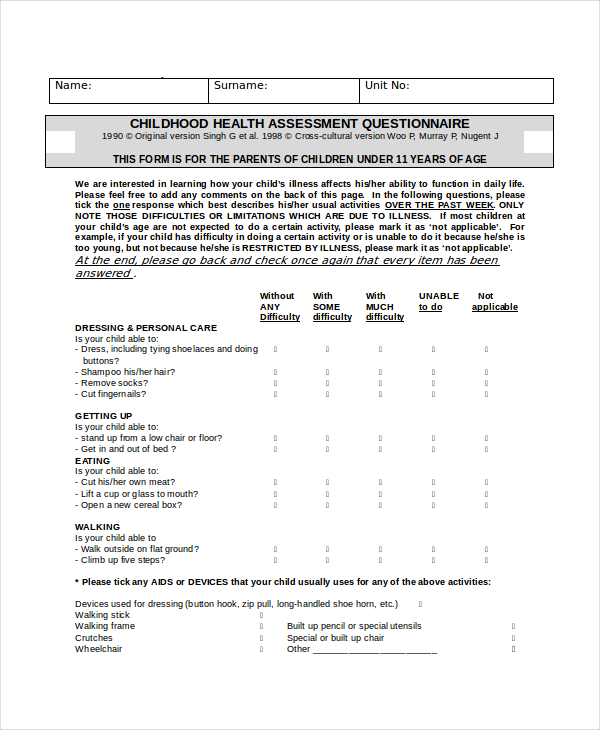

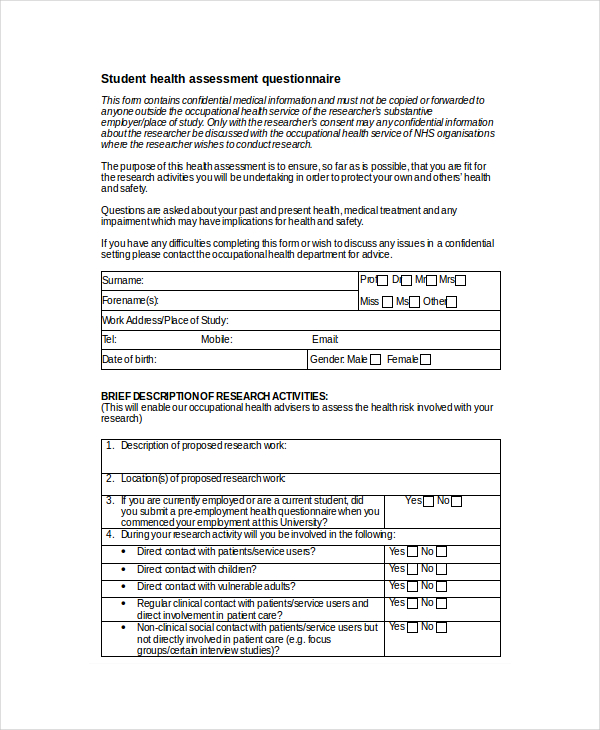

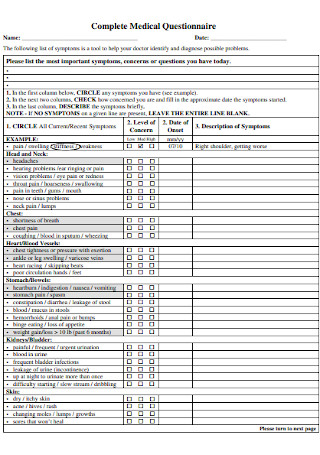

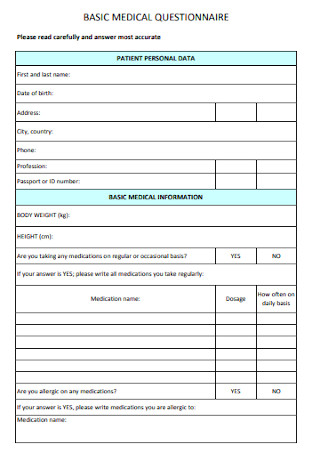

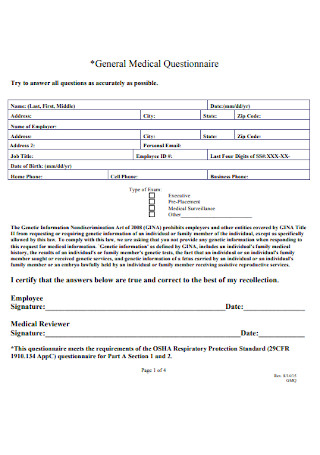

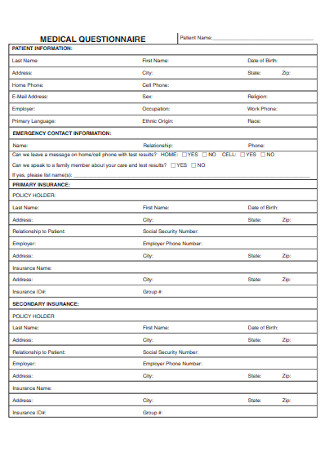

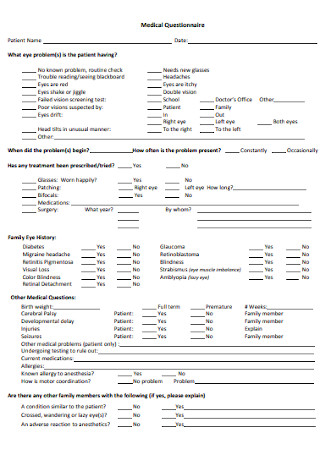

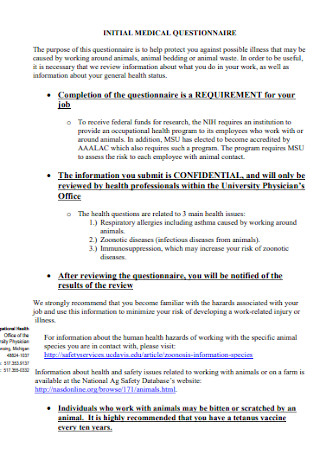

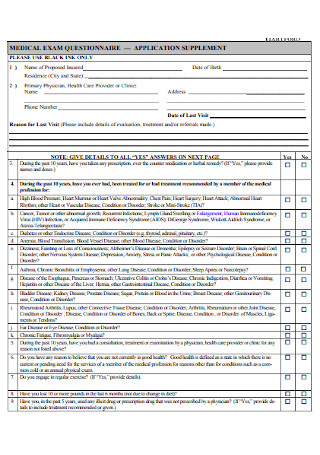

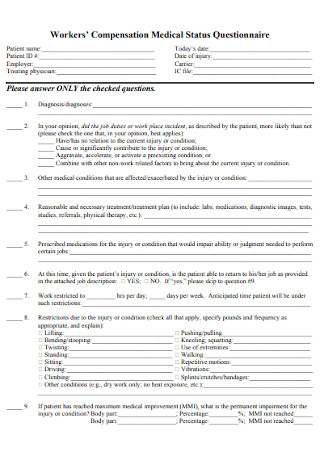

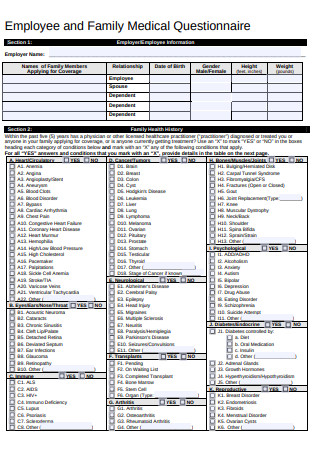

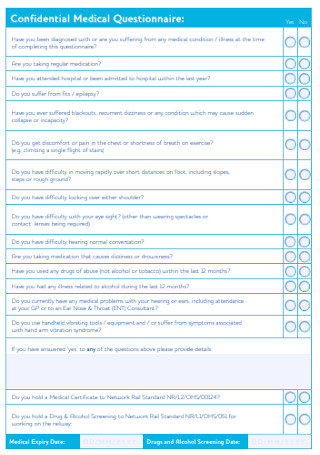

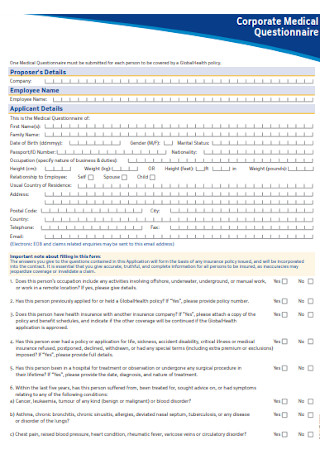

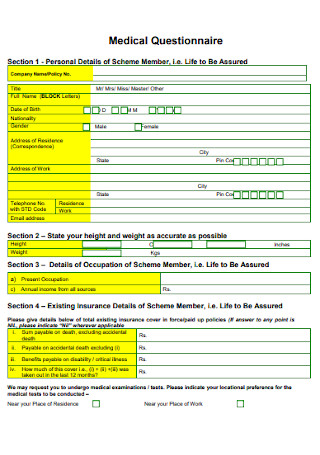

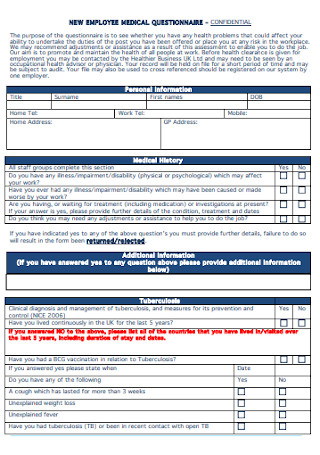

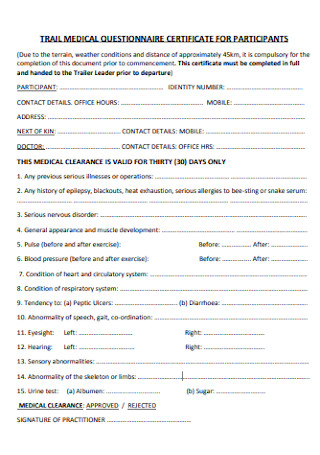

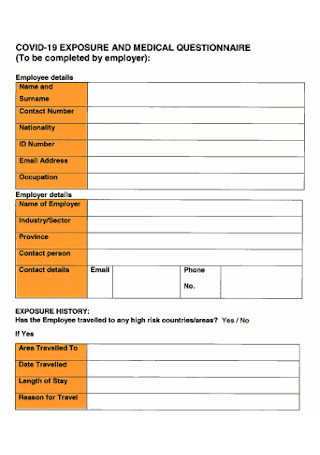

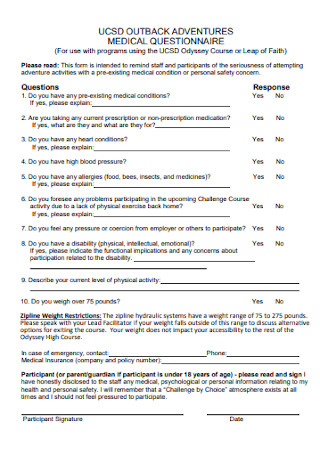

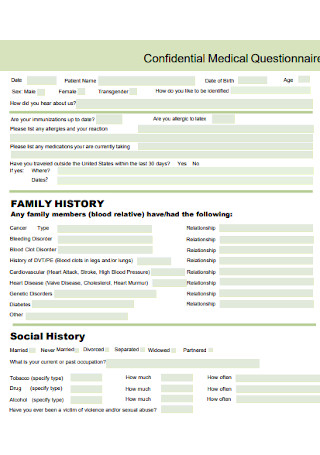

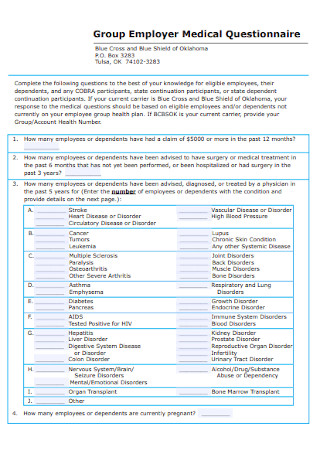

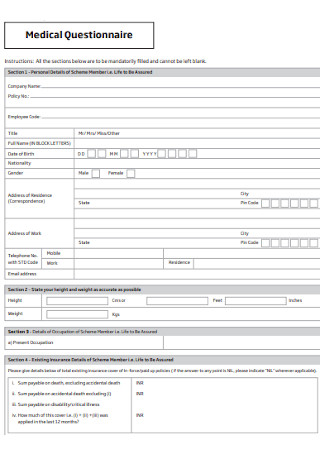

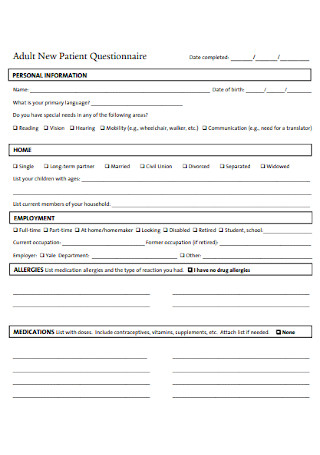

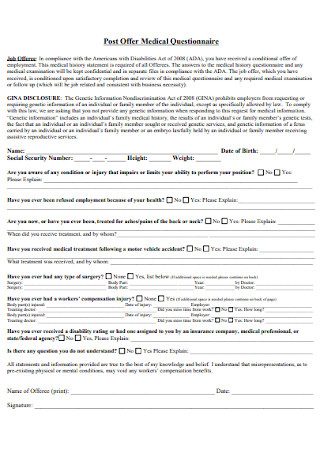

Medical Health Questionnaire

Streamline health assessments with our Medical Health Questionnaire to ensure accurate and efficient patient information gathering.

By Joshua Napilay on Apr 08, 2024.

Fact Checked by Nate Lacson.

Why is the Medical Health Questionnaire essential for accurate patient assessment?

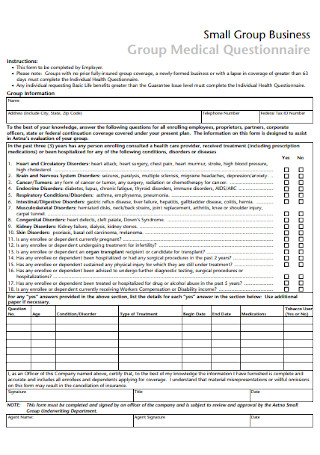

The Medical Health Questionnaire is indispensable for precise patient evaluation, particularly about high blood pressure, general health, and diabetes. This crucial form assists hospitals in determining the overall health of clients, ensuring accurate data on blood pressure, diabetes status, and the presence of conditions like depression. Respondents, including employees and regular clients, are prompted to complete the form regularly, providing a comprehensive snapshot of their health.

By incorporating fields such as age, birth date, tobacco use, and job-related details, the form helps gauge users' average health levels. The data collected aids in the early detection of conditions like high blood pressure and diabetes, enabling hospitals to offer timely interventions. Moreover, assessing the number of days people experience conditions like depression or heart-related issues allows medical professionals to tailor care plans accordingly.

Efficiently organized sections save time for respondents and medical staff, promoting ease of use. Users can easily share relevant information about their health status, ensuring that hospitals can read and interpret the data promptly. This form is an essential tool in the healthcare system, offering a systematic approach to gathering crucial health data, ultimately contributing to better patient outcomes.

Printable Medical Health Questionnaire

Download this Medical Health Questionnaire for precise patient evaluation, particularly about high blood pressure, general health, and diabetes.

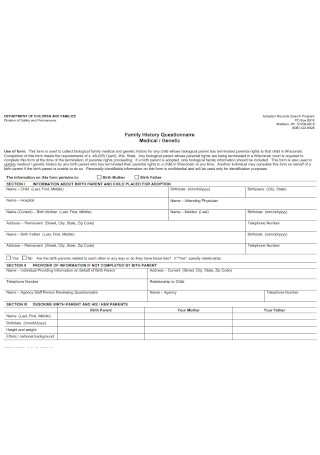

What key details should be gathered to establish a comprehensive medical profile?

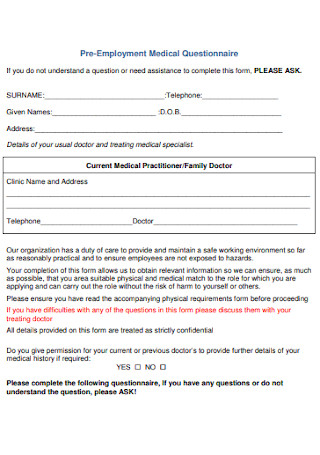

To establish a comprehensive medical profile, it is crucial to gather critical details systematically. The process begins by determining the person's basic information, such as name, age, and address. The following step involves eliciting information about their medical history, starting with the year they started seeking medical attention regularly. This information is essential to assess the progression of their health over time.

The person's present condition is a focal point, requiring a detailed exploration of ongoing health issues or concerns. Understanding the day-to-day impact of these conditions is essential, as it provides insights into their daily life and activities. Additionally, inquiring about the week-to-week variations in their health allows for a more nuanced understanding of their overall well-being.

In the section dedicated to work, it's essential to determine the level of physical activity and any occupational hazards that may contribute to their medical profile. Adding details about their home environment further enriches the understanding of factors influencing their health.

As you gather information, consider incorporating a section on lifestyle factors, including habits, diet, and exercise routines. This holistic approach ensures that the medical profile is comprehensive and offers a more nuanced understanding of the person's overall health. Starting with basic information and systematically adding pertinent details, this approach allows healthcare professionals to create a thorough and accurate medical profile.

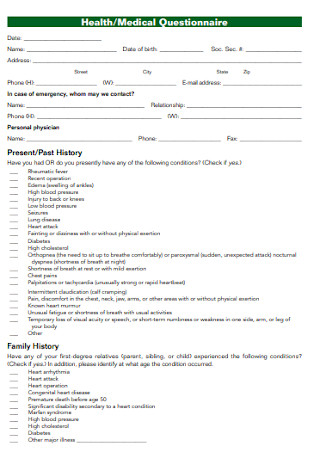

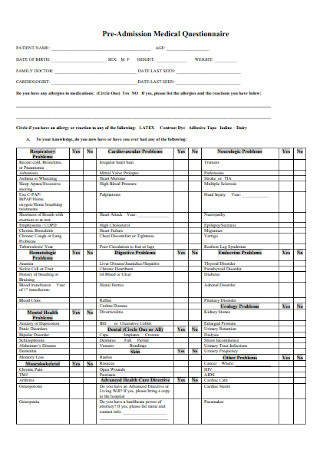

Have any significant medical events or conditions been in the patient's history?

When delving into a patient's medical history, the quest for significant events or conditions is paramount for a comprehensive understanding of their health trajectory. The inquiry begins with meticulously examining the patient's past, aiming to identify any noteworthy occurrences that may have left a lasting impact. This involves exploring major medical events, such as surgeries, hospitalizations, or significant illnesses that have shaped the patient's health narrative.

Chronic conditions are central to this investigation, as they often play a defining role in a patient's overall well-being. Uncovering conditions like diabetes, hypertension, or cardiovascular issues provides essential context for current health concerns. A detailed exploration of significant injuries, accidents, or allergic reactions also contributes valuable insights into the patient's medical history.

It is crucial to inquire about hereditary factors that might influence the patient's health, as a family history of certain conditions can significantly contribute to the overall risk assessment. Moreover, lifestyle-related events, such as changes in habits, diet, or exercise routines, are vital to understanding the patient's holistic health approach.

Pursuing significant medical events or conditions in a patient's history is integral to crafting a thorough medical profile. This comprehensive exploration enables healthcare professionals to tailor their approach, offering personalized care and interventions based on the patient's unique health journey.

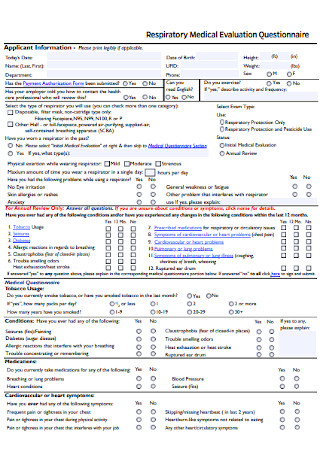

How do the patient's daily habits, such as diet and exercise, impact their health?

The patient's daily habits, including diet and exercise, profoundly influence their health and well-being. Diet, as a cornerstone of health, significantly shapes the body's nutritional intake, playing a pivotal role in various physiological functions.

A balanced and nutritious diet fosters optimal organ function, immune system strength, and energy levels. Conversely, poor dietary choices may contribute to nutritional deficiencies, obesity, or the development of chronic conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.

Exercise, another crucial component, contributes not only to physical fitness but also to mental health. Regular physical activity promotes cardiovascular health, muscular strength, and flexibility. It aids in weight management, reduces the risk of chronic diseases, and enhances overall mood by releasing endorphins. Conversely, a sedentary lifestyle may lead to weight gain, muscle atrophy, and an increased susceptibility to health issues.

The symbiotic relationship between diet and exercise further underscores the importance of a holistic approach to health. Healthy dietary choices synergize with regular exercise to create a robust foundation for overall wellness.

Healthcare professionals consider these daily habits when crafting personalized care plans, emphasizing the significance of lifestyle modifications in preventive healthcare. Recognizing the impact of diet and exercise empowers individuals to make informed choices, fostering a proactive approach to maintaining and enhancing their health.

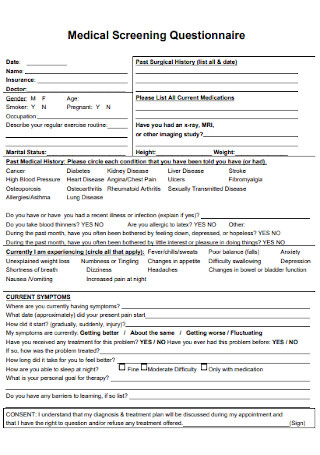

Medical Health Questionnaire example (sample)

Empower your healthcare practice with our free Medical Health Questionnaire example to enhance patient care and streamline information gathering. Download now to access a user-friendly template that prioritizes accuracy and efficiency, ensuring a seamless healthcare experience for providers and patients.

Take a proactive step towards comprehensive health assessments and improved medical outcomes. Your journey to enhanced patient care starts with a simple click – download your free guide today.

Download this free Medical Health Questionnaire example here

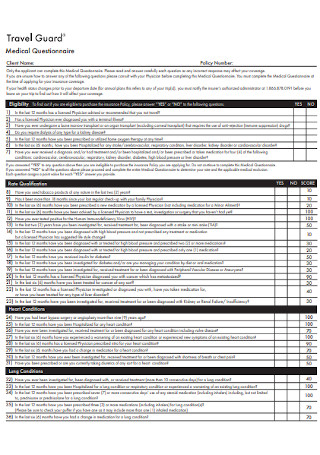

How does the family's medical history contribute to understanding the patient's health?

The family's medical history is a valuable lens through which healthcare professionals gain insights into the patient's health predispositions, potential risks, and genetic susceptibilities. Examining the health trajectory of close relatives aids in understanding familial patterns of certain conditions, offering crucial information for risk assessment and preventive care.

Genetic factors play a significant role in determining an individual's susceptibility to various illnesses. A family history of diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, or certain cancers can highlight potential genetic links, informing healthcare providers about the patient's inherent risk factors. This knowledge enables a proactive approach to preventive measures, early screenings, and targeted interventions.

Furthermore, understanding the family's medical history aids in identifying hereditary conditions or genetic disorders that may affect the patient's health. This information allows healthcare professionals to tailor their care plans, screenings, and diagnostic approaches to account for the familial context.

A comprehensive understanding of the family's medical history contributes to a more holistic and personalized approach to healthcare. It empowers healthcare providers to proactively anticipate and address potential health issues, emphasizing the importance of integrating genetic and familial factors into assessing a patient's health and well-being.

What role do habits like smoking and alcohol consumption play in the patient's health?

Habits such as smoking and alcohol consumption play a pivotal role in shaping the patient's overall health, exerting both immediate and long-term impacts. Smoking, a well-established health risk, is linked to a myriad of detrimental health outcomes.

It significantly increases the risk of respiratory conditions like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and lung cancer, cardiovascular diseases and compromises overall lung function. The harmful effects extend beyond the respiratory system, affecting nearly every organ in the body.

Alcohol consumption similarly influences health outcomes. While moderate alcohol intake may have certain cardiovascular benefits, excessive or chronic consumption poses serious health risks. Long-term alcohol abuse is associated with liver diseases, cardiovascular issues, increased susceptibility to infections, and mental health disorders.

Both smoking and excessive alcohol consumption contribute to the development of chronic conditions, compromising the immune system and overall well-being. These habits are often intertwined, amplifying their collective impact on health. Moreover, they can exacerbate existing health conditions and hinder the efficacy of medical treatments.

Understanding the role of these habits is crucial for healthcare providers to develop targeted interventions and counseling strategies. Addressing smoking and alcohol consumption within the context of a patient's health allows for a more comprehensive and tailored approach to preventive care and health management. Encouraging lifestyle modifications forms an integral part of promoting overall well-being and preventing the onset of severe health conditions.

Who should be contacted in case of a medical emergency, and what are their details?

In the event of a medical emergency, it is imperative to have immediate access to individuals who can provide crucial information and make decisions on behalf of the patient. The primary contact is typically the patient's designated emergency contact person. This individual should be someone close to the patient, aware of their medical history, and capable of making prompt decisions in critical situations. It is vital to provide the emergency contact person's name, relationship to the patient, and a reachable phone number.

Additionally, their details should be included if the patient has a designated healthcare proxy or power of attorney. These individuals can make healthcare decisions for the patient if they cannot do so themselves. Providing the healthcare proxy's name, relationship, and contact information ensures a seamless emergency communication channel.

For minors, it is essential to list the contact details of parents or legal guardians. Schools, childcare providers, or relevant institutions should have this information readily available.

Ensuring that emergency contacts are well-informed and easily reachable is paramount for swift and effective medical intervention. These details are crucial in facilitating communication between healthcare providers and the patient's support network during critical moments.

Research and evidence

The Medical Health Questionnaire has a rich history rooted in the evolution of healthcare practices and the growing recognition of the importance of comprehensive patient assessments (Bhat, 2023). Over the years, medical professionals and researchers have continually refined and expanded the scope of health questionnaires to enhance diagnostic accuracy, treatment planning, and overall patient care (Akman, 2023).

The development of medical questionnaires can be traced back to early efforts to systematize patient information. As medical science progressed, clinicians recognized the need for standardized tools to collect relevant data efficiently. This led to the creating of the first health questionnaires to capture a holistic view of an individual's health status, medical history, and lifestyle factors.

The evolution of these questionnaires has been heavily influenced by ongoing research in various medical disciplines (Cowley et al., 2022). Evidence-based practices and clinical studies have played a crucial role in shaping the questions included in health assessments, ensuring that they align with the latest medical knowledge and diagnostic criteria. The constant feedback loop between research findings and questionnaire refinement has resulted in more accurate and insightful tools for healthcare practitioners.

Today, the Medical Health Questionnaire is a testament to the collaboration between medical professionals, researchers, and technological advancements. Incorporating evidence-based elements ensures that the questionnaire remains a dynamic and reliable resource, adapting to the ever-changing healthcare landscape. As a result, healthcare providers can trust the historical foundation and ongoing research supporting the Medical Health Questionnaire as an invaluable instrument in promoting proactive and personalized patient care.

Why use Carepatron as your Medical Health Questionnaire software?

Elevate your healthcare practice with Carepatron, the ultimate solution for streamlined practice management . Our Medical Health Questionnaire software boasts a user-friendly interface, ensuring accessibility for all, regardless of technical expertise.

Benefit from customizable templates catering to various health questionnaires, including daily symptom surveys, medical assessments, and health risk evaluations. The platform's robust features, such as Electronic Health Record (EHR) integration , secure messaging, and automated appointment reminders, enhance practice efficiency and compliance with HIPAA regulations.

Experience unparalleled support and guidance from the team, assisting healthcare providers in interpreting results and developing personalized care plans. Revolutionize your clinical workflows, improve care delivery efficiency, and boost patient engagement.

Choose Carepatron as your go-to Medical Health Questionnaire software and embark on a journey towards optimized care and proactive patient well-being.

Akman, S. (2023, May 25). 35+ essential questions to ask in a health history questionnaire . 35+ Essential Questions to Ask in a Health History Questionnaire - forms. App. https://forms.app/en/blog/health-history-questionnaire-questions

Bhat, A. (2023, June 30). Health History questionnaire: 15 Must-Have Questions . QuestionPro. https://www.questionpro.com/blog/health-history-questionnaire/

Cowley, D. S., Burke, A., & Lentz, G. M. (2022). Additional considerations in gynecologic care. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 148-187.e6). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-323-65399-2.00018-8

Commonly asked questions

The specific questions on a health questionnaire vary but generally cover medical history, lifestyle, and current health status.

A medical questionnaire is a document that gathers information about an individual's medical history, conditions, and lifestyle for healthcare assessment.

Health assessment questions typically inquire about an individual's overall health, symptoms, lifestyle choices, and any relevant medical history.

Related Templates

Popular templates.

Shame Resilience Theory Template

Download a free resource that clients can use for a more goal-directed approach to building shame resilience.

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder Treatment Plan

Unlock efficient anxiety care with Carepatron's software, featuring patient management tools, secure communication, and streamlined billing.

Multiple Sclerosis Test

Discover the symptoms, causes, diagnosis, and treatment options for Multiple Sclerosis and understand comprehensive care approaches.

MCL Injury Test

Discover key insights on MCL injuries, from symptoms and diagnosis to recovery. Get expert advice for effective treatment and healing.

Dermatomyositis Diagnosis Criteria

Learn about the diagnostic criteria for dermatomyositis and see an example with Carepatron's free PDF download. Get the information you need to understand this condition.

Hip Mobility Test

Learn how to assess your hip mobility with a simple test. Download Carepatron's free PDF guide with examples to improve hip flexibility and function.

Massage Chart

Explore our comprehensive Massage Chart for holistic healthcare solutions and techniques. Perfect for practitioners and enthusiasts alike!

Occupational Therapy Acute Care Cheat Sheet

Streamline patient recovery with key strategies for enhancing independence in acute settings. Download our free Occupational Therapy Acute Care Cheat Sheet.

Neck Pain Chart

Explore our comprehensive Neck Pain Chart for insights into causes, symptoms, and treatments. Find relief and understanding today.

School Readiness Assessment

Discover the benefits of our School Readiness Assessment template with a free PDF download to ensure children are prepared for kindergarten through grade three.

Sedation Scale Nursing (Ramsay Sedation Scale)

Discover key sedation scales used in nursing, including RASS and Ramsay Scale, for accurate patient sedation assessment in critical care settings.

Blood Tests for Lupus

Download a free Blood Tests for Lupus template. Learn the various types of tests used to diagnose this disease.

Neurological Exam Template

Discover the importance of neurological assessments for diagnosing and monitoring conditions with our comprehensive guide and template. templates

Homeopathic Dosage Chart

Discover the principles of homeopathy, dosage guidelines, and effectiveness, with references and a downloadable chart for practical use.

Gout Diagnosis Criteria

Uncover the essential Gout Diagnosis Criteria here, including symptoms, diagnostic tests, and the American College of Rheumatology guidelines.

Peroneal Tendon Tear Test

Learn about the Peroneal Tendon Tear Test and use our template to record results!

Ear Seeds Placement Chart

Learn what ear seeds are and download our Ear Seeds Placement Chart template!

Global Rating of Change Scale

Explore the Global Rating of Change Scale, a key tool to assess the clinical significance of patient-reported outcomes. Get your free PDF template now.

Physical Therapy Initial Evaluation

Unlock the benefits of Physical Therapy Initial Evaluation: a key step in personalized treatment planning for improved mobility and pain relief.

8-Week Group Counseling Plan

Discover a flexible template for creating effective 8-Week Group Counseling Plans, tailored to meet diverse needs and foster growth.

Osteoarthritis Treatment Guidelines

Learn about the management of osteoarthritis, treatments, causes, and care strategies. Access tips for managing symptoms and improving quality of life in our guide.

Prone Knee Bend Test

Learn about the Prone Knee Bend Test and how it assesses radicular pain.

PTSD Treatment Guidelines

Download our PTSD Treatment Guidelines template to access evidence-based treatment plans, diagnostic tools, and personalized care strategies.

Assess alcohol use with AUDIT-C: quick, accurate alcohol screening tests for hazardous drinking. Learn your risk level in minutes. Download our free template now!

Cincinnati Stroke Scale Scoring

Learn to quickly identify stroke symptoms with the Cincinnati Stroke Scale Scoring guide, which is essential for emergency responders and healthcare professionals.

Lupus Diagnosis Criteria

Download a helpful checklist tool to help diagnose lupus among patients for early identification and intervention. Access your free resource here!

Quadriceps Strain Test

Get access to a free Quadriceps Strain Test template. Learn how to interpret results and streamline your documentation with a free PDF.

Dysarthria Treatment Exercises

Discover effective dysarthria exercises to improve speech clarity. Download our free guide for tailored speech therapy techniques.

Antisocial Personality Disorder Test

Use a helpful evidence-based Antisocial Personality Disorder Test to identify ASPD symptoms among clients and improve health outcomes.

Persistent Depressive Disorder Test

Explore an evidence-based screening tool to help diagnose persistent depressive disorder among clients.

Thinking Traps Worksheet

Unlock a healthier mindset with our Thinking Traps Worksheet, designed to identify and correct cognitive distortions. Download your free example today.

Coping Cards

Coping Cards can aid clients in managing distressing emotions. Explore examples, download a free sample, and learn how to integrate them into therapy effectively.

EFT Cycle Worksheet

Download our free EFT Cycle Worksheet example and discover the benefits of integrating it into your practice.

Torn Meniscus Self Test

Discover how to identify a torn meniscus with our self-test guide. Learn about meniscus function and symptoms, and download our free self-test template today.

Prediabetes Treatment Guidelines

Download a free Prediabetes Treatment Guidelines and example to learn more about managing prediabetes effectively.

Nurse Practitioner Performance Evaluation

Enhance clinical performance, communication, and patient satisfaction in your healthcare system. Download our Nurse Practitioner Performance Evaluation today!

Psychophysiological Assessment

Explore Psychophysiological Assessments with our free template. Understand the link between mental processes and physical responses. Download now.

Occupational Therapy Pediatric Evaluation

Learn about the process of pediatric occupational therapy evaluation. Download Carepatron's free PDF example to assist in understanding and conducting assessments for children.

Dementia Treatment Guidelines

Explore comprehensive dementia treatment guidelines and use Carepatron's free PDF download of an example plan. Learn about effective strategies and interventions for dementia care.

Coping with Auditory Hallucinations Worksheet

Use our Coping with Auditory Hallucinations Worksheet to help your patients manage and differentiate real sensations from hallucinations effectively.

Tight Hip Flexors Test

Assess the tightness of your patient's hip flexor muscles with a tight hip flexors test. Click here for a guide and free template!

Gender Dysphoria DSM 5 Criteria

Explore the DSM-5 criteria for Gender Dysphoria with our guide and template, designed to assist with understanding and accurate diagnosis.

Bronchitis Treatment Guidelines

Explore bronchitis treatment guidelines for both acute and chronic forms, focusing on diagnosis, management, and preventive measures.

Patient Safety Checklist

Enhance safety in healthcare processes with the Patient Safety Checklist, ensuring comprehensive adherence to essential safety protocols.

Fatigue Assessment

Improve workplace safety and employee well-being with this valuable resource. Download Carepatron's free PDF of a fatigue assessment tool here to assess and manage fatigue in various settings.

AC Shear Test

Get access to a free AC Shear Test. Learn how to perform this assessment and record findings using our PDF template.

Hip Flexor Strain Test

Access our Hip Flexor Strain Test template, designed for healthcare professionals to diagnose and manage hip flexor strains, complete with a detailed guide.

Integrated Treatment Plan

Explore the benefits of Integrated Treatment for dual diagnosis, combining care for mental health and substance abuse for holistic recovery.

Nursing Assessment of Eye

Explore comprehensive guidelines for nursing eye assessments, including techniques, common disorders, and the benefits of using Carepatron.

Nursing Care Plan for Impaired Memory

Discover our Nursing Care Plan for Impaired Memory to streamline your clinical documentation. Download a free PDF template here.

Clinical Evaluation

Explore the process of conducting clinical evaluations and its importance in the therapeutic process. Access a free Clinical Evaluation template to help you get started.

Finger Prick Blood Test

Learn how to perform the Finger Prick Blood Test in this guide. Download a free PDF and sample here.

Discover PROMIS 29, a comprehensive tool for measuring patient-reported health outcomes, facilitating better healthcare decision-making.

Criteria for Diagnosis of Diabetes

Streamline diabetes management with Carepatron's templates for accurate diagnosis, early treatment, care plans, and effective patient strategies.

Psych Nurse Report Sheet

Streamline patient care with our comprehensive Psych Nurse Report Sheet, designed for efficient communication and organization. Download now!

Promis Scoring

Introduce a systematic approach to evaluating patient health through the PROMIS measures and learn how to interpret its scores.

Chronic Illnesses List

Access this helpful guide on chronic illnesses you can refer to when working on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment planning.

List of Tinctures and Uses

Discover the power of herbal tinctures with our List of Tinctures and Uses, detailing their uses, benefits, and ways to incorporate them into your life.

Ankle Bump Test

Learn how to do an Ankle Bump Test and how to interpret the results. Download a free PDF template here.

Workout Form

Master the proper way to exercise with the Workout Form. Avoid serious injury and achieve your fitness goals effectively. Start your journey now!

Critical Thinking Worksheets

Unlock the power of critical thinking with our expertly crafted Critical Thinking Worksheets, designed to foster analytical skills and logical reasoning in students.

Therapy Letter for Court

Explore our guide on writing Therapy Letters for Court, offering templates and insights for therapists to support clients' legal cases effectively.

Nursing Nutrition Assessment

Learn about nursing nutrition assessments, including examples and Carepatron's free PDF download to help you understand the process and improve patient care.

Facial Massage Techniques PDF

Unlock the secrets of rejuvenating facial massage techniques with Carepatron's comprehensive PDF guide. Learn how to enhance your skincare routine and achieve a radiant, glowing complexion.

Blood Test for Heart Attack

Learn about the importance of blood tests for detecting heart attacks and download Carepatron's free PDF example for reference. Find crucial information to help you understand the process.

Substance Use Disorder DSM 5 Criteria

Understanding substance use disorder, its symptoms, withdrawal symptoms, causes, and diagnosis through DSM 5 criteria. Download our free Substance Use Disorder DSM 5 Criteria

Mental Health Handout

Learn key insights into mental health conditions, warning signs, and resources. Access a free Mental Health Handout today!

SNAP Assessment

Learn more about SNAP Assessment, its purpose, and how to use it effectively. Download a free example and learn about scoring, interpretation, and next steps.

Procedure Note Template

Ensure patient identity, consent, anesthesia, vital signs, and complications are documented. Download our accessible Procedure Note Template today!

Nursing Home Report Sheet

Discover a comprehensive guide on creating a Nursing Home Report Sheet. Includes tips, examples, and a free PDF download to streamline healthcare reporting.

Obesity Chart

Explore our free Obesity Chart and example, designed to help practitioners and patients monitor overall health risks associated with obesity.

Cognitive Processing Therapy Worksheets

Download our free CPT Worksheet to tackle traumatic beliefs and foster recovery with structured exercises for emotional well-being.

Charge Nurse Duties Checklist

Take charge with our comprehensive Charge Nurse Duties Checklist. Free PDF download available!

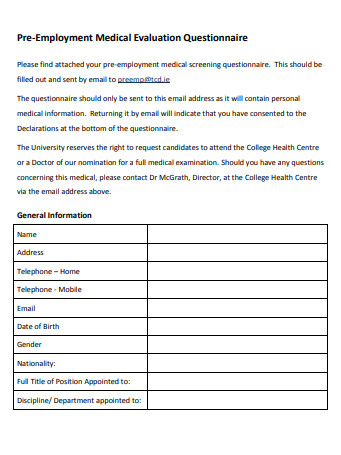

Pre-employment Medical Exam

Ensure job applicants' fitness for duty with our Pre-Employment Medical Exam Template. Comprehensive guide for thorough health assessments.

Medical Clearance Form

Get your health clearance certificate easily with our Medical Clearance Form. Download for free for a streamlined process and hassle-free experience.

Whipple Test

Access a free Whipple Test PDF template for your physical therapy practice. Streamline your documentation with our free form.

Shoulder Mobility Test

Get access to a free Shoulder Mobility Test PDF. Learn how to assess your patient's shoulder mobility and streamline your clinical documentation.

Level of Care Assessment

Discover what a Level of Care Assessment entails and access Carepatron's free PDF download with an example to help you better understand the process.

Standard Intake Questionnaire Template

Access a standard intake questionnaire tool to help you enhance the initial touchpoint with patients in their healthcare process.

Patient Workup Template

Optimize patient care with our comprehensive Patient Workup Template. Streamline assessments and treatment plans efficiently.

Stroke Treatment Guidelines

Explore evidence-based Stroke Treatment Guidelines for effective care. Expert recommendations to optimize stroke management.

Counseling Theories Comparison Chart

Explore a tool to differentiate counseling theories and select approaches that can work best for each unique client.

Long Term Care Dietitian Cheat Sheet

Discover how a Long-Term Care Dietitian Cheat Sheet can streamline nutritional management to ensure personalized and efficient dietary planning for patients.

Perio Chart Form

Streamline patient care with detailed periodontal assessments, early disease detection, and personalized treatment plans. Download our Perio Chart Forms.

Nursing Registration Form

Learn what a nurse registry entails, its significance to registered nurses, and the application process completed through a Nursing Registration Form.

Straight Leg Test for Herniated Disc

Download a free Straight Leg Test for Herniated Disc template. Learn how to perform the test and streamline your clinical documentation.

Physical Therapy Plan of Care

Download Carepatron's free PDF example of a comprehensive Physical Therapy Plan of Care. Learn how to create an effective treatment plan to optimize patient outcomes.

ABA Intake Form

Access a free PDF template of an ABA Intake Form to improve your initial touchpoint in the therapeutic process.

Safety Plan for Teenager Template

Discover our comprehensive Safety Plan for Teenagers Template with examples. Download your free PDF!

Speech Language Pathology Evaluation Report

Get Carepatron's free PDF download of a Speech Language Pathology Evaluation Report example to track therapy progress and communicate with team members.

Home Remedies for Common Diseases PDF

Explore natural and effective Home Remedies for Common Diseases with our guide, and educate patients and caretakers to manage ailments safely at home.

HIPAA Policy Template

Get a comprehensive HIPAA policy template with examples. Ensure compliance, protect patient privacy, and secure health information. Free PDF download available.

Health Appraisal Form

Download a free Health Appraisal Form for young patients. Streamline your clinical documentation with our PDF template and example.

Consent to Treat Form for Adults

Discover the importance of the Consent to Treat Form for adults with our comprehensive guide and example. Get your free PDF download today!

Nursing Skills Assessment

Know how to evaluate nursing skills and competencies with our comprehensive guide. Includes an example template for a Nursing Skills Assessment. Free PDF download available.

Medical Record Request Form Template

Discover how to streamline medical record requests with our free template & example. Ensure efficient, compliant processing. Download your PDF today.

Personal Training Questionnaire

Access a comprehensive Personal Training Questionnaire to integrate when onboarding new clients to ensure a personalized fitness plan.

Agoraphobia DSM 5 Criteria

Explore a helpful documentation tool to help screen for the symptoms of agoraphobia among clients. Download a free PDF resource here.

Dental Inventory List

Streamline your dental practice's inventory management with our Dental Inventory List & Example, available for free PDF download.

Personal Trainer Intake Form

Discover how to create an effective Personal Trainer Intake Form with our comprehensive guide & free PDF example. Streamline your fitness assessments now.

Join 10,000+ teams using Carepatron to be more productive

- Open access

- Published: 11 January 2010

Questionnaires in clinical trials: guidelines for optimal design and administration

- Phil Edwards 1

Trials volume 11 , Article number: 2 ( 2010 ) Cite this article

73k Accesses

107 Citations

25 Altmetric

Metrics details

A good questionnaire design for a clinical trial will minimise bias and maximise precision in the estimates of treatment effect within budget. Attempts to collect more data than will be analysed may risk reducing recruitment (reducing power) and increasing losses to follow-up (possibly introducing bias). The mode of administration can also impact on the cost, quality and completeness of data collected. There is good evidence for design features that improve data completeness but further research is required to evaluate strategies in clinical trials. Theory-based guidelines for style, appearance, and layout of self-administered questionnaires have been proposed but require evaluation.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

With fixed trial resources there will usually be a trade off between the number of participants that can be recruited into a trial and the quality and quantity of information that can be collected from each participant [ 1 ]. Although half a century ago there was little empirical evidence for optimal questionnaire design, Bradford Hill suggested that for every question asked of a study participant the investigator should be required to answer three himself, perhaps to encourage the investigator to keep the number of questions to a minimum [ 2 ].

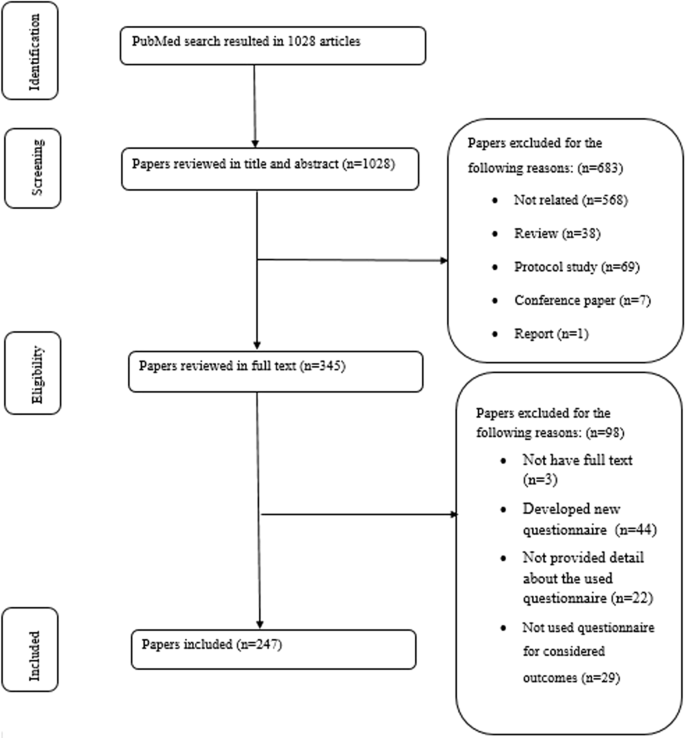

To assess the empirical evidence for how questionnaire length and other design features might influence data completeness in a clinical trial, a systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) was conducted, and has recently been updated [ 3 ]. The strategies found to be effective in increasing response to postal and electronic questionnaires are summarised in the section on increasing data completeness below.

Clinical trial investigators have also relied on principles of questionnaire design that do not have an established empirical basis, but which are nonetheless considered to present 'good practice', based on expert opinion. The section on questionnaire development below includes some of that advice and presents general guidelines for questionnaire development which may help investigators who are about to design a questionnaire for a clinical trial.

As this paper concerns the collection of outcome data by questionnaire from trial participants (patients, carers, relatives or healthcare professionals) it begins by introducing the regulatory guidelines for data collection in clinical trials. It does not address the parallel (and equally important) needs of data management, cleaning, validation or processing required in the creation of the final clinical database.

Regulatory guidelines

The International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) of technical requirements for registration of pharmaceuticals for human use states:

'The collection of data and transfer of data from the investigator to the sponsor can take place through a variety of media, including paper case record forms, remote site monitoring systems, medical computer systems and electronic transfer. Whatever data capture instrument is used, the form and content of the information collected should be in full accordance with the protocol and should be established in advance of the conduct of the clinical trial. It should focus on the data necessary to implement the planned analysis, including the context information (such as timing assessments relative to dosing) necessary to confirm protocol compliance or identify important protocol deviations. 'Missing values' should be distinguishable from the 'value zero' or 'characteristic absent'...' [ 4 ].

This suggests that the choice of variables that are to be measured by the questionnaire (or case report form) is constrained by the trial protocol, but that the mode of data collection is not. The trial protocol is unlikely, however, to list all of the variables that may be required to evaluate the safety of the experimental treatment. The choice of variables to assess safety will depend on the possible consequences of treatment, on current knowledge of possible adverse effects of related treatments, and on the duration of the trial [ 5 ]. In drug trials there may be many possible reactions due to the pharmacodynamic properties of the drug. The Council for International Organisations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) advises that:

'Safety data that cannot be categorized and succinctly collected in predefined data fields should be recorded in the comment section of the case report form when deemed important in the clinical judgement of the investigator' [ 5 ].

Safety data can therefore initially be captured on a questionnaire as text responses to open-ended questions that will subsequently be coded using a common adverse event dictionary, such as the Medical Dictionary for Drug Regulatory Activities (MEDRA). The coding of text responses should be performed by personnel who are blinded to treatment allocation. Both ICH and CIOMS warn against investigators collecting too much data that will not be analysed, potentially wasting time and resources, reducing the rate of recruitment, and increasing losses to follow-up.

Before questionnaire design begins, the trial protocol should be available at least in draft. This will state which outcomes are to be measured and which parameters are of interest (for example, percentage, mean, and so on). Preferably, a statistical analysis plan will also be available that makes explicit how each variable will be analysed, including how precisely each is to be measured and how each variable will be categorised in analysis. If these requirements are known in advance, the questionnaire can be designed in such a way that will reduce the need for data to be coded once questionnaires have been completed and returned.

Questionnaire development

If a questionnaire has previously been used in similar trials to the one planned, its use will bring the added advantage that the results will be comparable and may be combined in a meta-analysis. However, if the mode of administration of the questionnaire will change (for example, questions developed for administration by personal interview are to be included in a self-administered questionnaire), the questionnaire should be piloted before it is used (see section on piloting below). To encourage the consistent reporting of serious adverse events across trials, the CIOMS Working Group has prepared an example of the format and content of a possible questionnaire [ 5 ].

If a new questionnaire is to be developed, testing will establish that it measures what is intended to be measured, and that it does so reliably. The validity of a questionnaire may be assessed in a reliability study that assesses the agreement (or correlation) between the outcome measured using the questionnaire with that measured using the 'gold standard'. However, this will not be possible if there is no recognised gold standard measurement for outcome. The reliability of a questionnaire may be assessed by quantifying the strength of agreement between the outcomes measured using the questionnaire on the same patients at different times. The methods for conducting studies of validity and reliability are covered in depth elsewhere [ 6 ]. If new questions are to be developed, the reading ease of the questions can be assessed using the Flesch reading ease score. This score assesses the number of words in sentences, and the number syllables in words. Higher Flesch reading scores indicate material that is easier to read [ 7 ].

Types of questions

Open-ended questions offer participants a space into which they can answer by writing text. These can be used when there are a large number of possible answers and it is important to capture all of the detail in the information provided. If answers are not factual, open-ended questions might increase the burden on participants. The text responses will subsequently need to be reviewed by the investigator, who will (whilst remaining blind to treatment allocation) assign one or more codes that categorise the response (for example, applying an adverse event dictionary) before analysis. Participants will need sufficient space so that full and accurate information can be provided.

Closed-ended questions contain either mutually exclusive response options only, or must include a clear instruction that participants may select more than one response option (for example, 'tick all that apply'). There is some evidence that answers to closed questions are influenced by the values chosen by investigators for each response category offered and that respondents may avoid extreme categories [ 8 ]. Closed-ended questions where participants are asked to 'tick all that apply' can alternatively be presented as separate questions, each with a 'yes' or 'no' response option (this design may be suitable if the analysis planned will treat each response category as a binary variable).

Asking participants subsidiary questions (that is, 'branching off') depending on their answers to core questions will provide further detail about outcomes, but will increase questionnaire length and could make a questionnaire harder to follow. Similarly 'matrix' style questions (that is, multiple questions with common response option categories) might seem complicated to some participants, adding to the data collection burden [ 9 ].

Style, appearance and layout

The way that a self-administered questionnaire looks is considered to be as important as the questions that are asked [ 9 , 10 ]. There is good evidence that in addition to the words that appear on the page (verbal language) the questionnaire communicates meaning and instructions to participants via symbols and graphical features (non-verbal language). The evidence from several RCTs of alternative question response styles and layouts suggests that participants view the middle (central) response option as the one that represents the midpoint of an outcome scale. Participants then expect response options to appear in an order of increasing or decreasing progression, beginning with the leftmost or uppermost category; and they expect response options that are closer to each other to also have values that are 'conceptually closer'. The order, spacing and grouping of response options are therefore important design features, as they will affect the quality of data provided on the questionnaire, and the time taken by participants to provide it [ 10 ].

Some attempts have been made to develop theory-based guidelines for self-administered questionnaire design [ 11 ]. Based on a review of psychological and sociological theories about graphic language, cognition, visual perception and motivation, five principles have been derived:

'Use the visual elements of brightness, colour, shape, and location in a consistent manner to define the desired navigational path for respondents to follow when answering the questionnaire;

When established format conventions are changed in the midst of a questionnaire use prominent visual guides to redirect respondents;

Place directions [instructions] where they are to be used and where they can be seen;

Present information in a manner that does not require respondents to connect information from separate locations in order to comprehend it;

Ask people to answer only one question at a time' [ 11 ].

Adherence to these principles may help to ensure that when participants complete a questionnaire they understand what is being asked, how to give their response, and which question to answer next. This will help participants to give all the information being sought and reduce the chances that they become confused or frustrated when completing the questionnaire. These principles require evaluation in RCTs.

Font size and colour may further affect the legibility of a questionnaire, which may also impact on data quality and completeness. Questionnaires for trials that enrol older participants may therefore require the use of a larger font (for example, 11 or 12 point minimum) than those for trials including younger participants. The legibility and comprehension of the questionnaire can be assessed during the pilot phase (see section on piloting below).

Perhaps most difficult to define are the factors that make a questionnaire more aesthetically pleasing to participants, and that may potentially increase compliance. The use of space, graphics, underlining, bold type, colour and shading, and other qualities of design may affect how participants react and engage with a questionnaire. Edward Tufte's advice for achieving graphical excellence [ 12 ] might be adapted to consider how to achieve excellence in questionnaire design, viz : ask the participant the simplest, clearest questions in the shortest time using the fewest words on the fewest pages; above all else ask only what you need to know.

Further research is therefore needed (as will be seen in the section on increasing data completeness) into the types of question and the aspects of style, appearance and layout of questionnaires that are effective in increasing data quality and completeness.

Mode of administration

Self-administered questionnaires are usually cheaper to use as they require no investigator input other than that for their distribution. Mailed questionnaires require correct addresses to be available for each participant, and resources to cover the costs of delivery. Electronically distributed questionnaires require correct email addresses as well as access to computers and the internet. Mailed and electronically distributed questionnaires have the advantage that they give participants time to think about their responses to questions, but they may require assistance to be available for participants (for example, a telephone helpline).

As self-administered questionnaires have least investigator involvement they are less susceptible to information bias (for example, social desirability bias) and interviewer effects, but are more susceptible to item non-response [ 8 ]. Evidence from a systematic review of 57 studies comparing self-reported versus clinically verified compliance with treatment suggests that questionnaires and diaries may be more reliable than interviews [ 13 ].

In-person administration allows a rapport with participants to be developed, for example through eye contact, active listening and body language. It also allows interviewers to clarify questions and to check answers. Telephone administration may still provide the aural dimension (active listening) of an in-person interview. A possible disadvantage of telephone interviews is that participants may become distracted by other things going on around them, or decide to end the call [ 9 ].

A mixture of modes of administration may also be considered: for example, participant follow-up might commence with postal or email administration of the questionnaire, with subsequent telephone calls to non-respondents. The offer of an in-person interview may also be necessary, particularly if translation to a second language is required, or if participants are not sufficiently literate. Such approaches may risk introducing selection bias if participants in one treatment group are more or less likely than the other group to respond to one mode of administration used (for example, telephone follow-up in patients randomised to a new type of hearing aid) [ 14 ].

An advantage of electronic and web-based questionnaires is that they can be designed automatically to screen and filter participant responses. Movement from one question to the next can then appear seamless, reducing the data collection burden on participants who are only asked questions relevant to previous answers. Embedded algorithms can also check the internal consistency of participant responses so that data are internally valid when submitted, reducing the need for data queries to be resolved later. However, collection of data from participants using electronic means may discriminate against participants without access to a computer or the internet. Choice of mode of administration must therefore take into account its acceptability to participants and any potential for exclusion of eligible participants that may result.

Piloting is a process whereby new questionnaires are tested, revised and tested further before they are used in the main trial. It is an iterative process that usually begins by asking other researchers who have some knowledge and experience in a similar field to comment on the first draft of the questionnaire. Once the questionnaire has been revised, it can then be piloted in a non-expert group, such as among colleagues. A further revision of the questionnaire can be piloted with individuals who are representative of the population who will complete it in the main trial. In-depth 'cognitive interviewing' might also provide insights into how participants comprehend questions, process and recall information, and decide what answers to give [ 15 ]. Here participants are read each question and are either asked to 'think aloud' as they consider what their answer will be, or are asked further 'probing' questions by the interviewer.

For international multicentre trials it will be necessary to translate a questionnaire. Although a simple translation to, and translation back from the second language might be sufficient, further piloting and cognitive interviews may be required to identify and correct for any cultural differences in interpretation of the translated questionnaire. Translation into other languages may alter the layout and formatting of words on the page from the original design and so further redesign of the questionnaire may be required. If a questionnaire is to be developed for a clinical trial, sufficient resources are therefore required for its design, piloting and revision.

Increasing data completeness

Loss to follow-up will reduce statistical power by reducing the effective sample size. Losses may also introduce bias if the trial treatment is an effect modifier for the association between outcome and participation at follow-up [ 16 ].

There may be exceptional circumstances for allowing participants to skip certain questions (for example, sensitive questions on sexual lifestyle) to ensure that the remainder of the questionnaire is still collected; the data that are provided may then be used to impute the values of variables that were not provided. Although the impact of missing outcome data and missing covariates on study results can be reduced through the use of multiple imputation techniques, no method of analysis can be expected to overcome them completely [ 17 ].

Longer and more demanding tasks might be expected to have fewer volunteers than shorter, easier tasks. The evidence from randomised trials of questionnaire length in a range of settings seems to support the notion that when it comes to questionnaire design 'shorter is better' [ 18 ]. Recent evidence that a longer questionnaire achieved the same high response proportion as that of a shorter alternative might cast doubt on the importance of the number of questions included in a questionnaire [ 19 ]. However, under closer scrutiny the results of this study (96.09% versus 96.74%) are compatible with an average 2% reduction in odds of response for each additional page added to the shorter version [ 18 ]. The main lesson seems to be that when the baseline response proportion is very high (for example, over 95%) then few interventions are likely to have effects large enough to increase it further.

There is a trade off between increased measurement error from using a simplified outcome scale and increased power from achieving measurement on a larger sample of participants (from fewer losses to follow-up). If a shorter version of an outcome scale provides measures of an outcome that are highly correlated with the longer version, then it will be more efficient for the trial to use the shorter version [ 1 ]. A moderate reduction to the length of a shorter questionnaire will be more effective in reducing losses to follow-up than a moderate change to the length of a longer questionnaire [ 18 ].

In studies that seek to collect information on many outcomes, questionnaire length will necessarily be determined by the number of items required from each participant. In very compliant populations there may be little lost by using a longer questionnaire. However, using a longer questionnaire to measure more outcomes may also increase the risk of false positive findings that result from multiple testing (for example, measuring 100 outcomes may produce 5 that are significantly associated with treatment by chance alone) [ 4 , 20 ].

Other strategies to increase completeness

A recently updated Cochrane systematic review presents evidence from RCTs of methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires in a range of health and non-health settings [ 3 ]. The review includes 481 trials that evaluated 110 different methods for increasing response to postal questionnaires and 32 trials that evaluated 27 methods for increasing response to electronic questionnaires. The trials evaluate aspects of questionnaire design, the introductory letter, packaging and methods of delivery that might influence the tendency for participants to open the envelope (or email) and to engage with its contents. A summary of the results follows.

What participants are offered

Postal questionnaires.

The evidence favours offering monetary incentives and suggests that money is more effective than other types of incentive (for example, tokens, lottery tickets, pens, and so on). The relationship between the amount of monetary incentive offered and questionnaire response is non-linear with diminishing marginal returns for each additional amount offered [ 21 ]. Unconditional incentives appear to be more effective, as are incentives offered with the first rather than a subsequent mailing. There is less evidence for the effects of offering the results of the study (when complete) or offering larger non-monetary incentives.

Electronic questionnaires

The evidence favours non-monetary incentives (for example, Amazon.com gift cards), immediate notification of lottery results, and offering study results. Less evidence exists for the effect of offering monetary rather than non-monetary incentives.

How questionnaires look

The evidence favours using personalised materials, a handwritten address, and printing single sided rather than double sided. There is also evidence that inclusion of a participant's name in the salutation at the start of the cover letter increases response and that the addition of a handwritten signature on letters will further increase response [ 22 ]. There is less evidence for positive effects of using coloured or higher quality paper, identifying features (for example, identity number), study logos, brown envelopes, coloured ink, coloured letterhead, booklets, larger paper, larger fonts, pictures in the questionnaire, matrix style questions, or questions that require recall in order of time period.

The evidence favours using a personalised approach, a picture in emails, a white background for emails, a simple header, and textual rather than a visual presentation of response categories. Response may be reduced when 'survey' is mentioned in the subject line. Less evidence exists for sending emails in text format or HTML, including a topic in email subject lines, or including a header in emails.

How questionnaires are received or returned

The evidence favours sending questionnaires by first class or recorded delivery, using stamped return envelopes, and using several stamps. There is less evidence for effects of mailing soon after discharge from hospital, mailing or delivering on a Monday, sending to work addresses, using stamped outgoing envelopes (rather than franked), using commemorative or first class stamps on return envelopes, including a prepaid return envelope, using window or larger envelopes, or offering the option of response by internet.

Methods and number of requests for participation

The evidence favours contacting participants before sending questionnaires, follow-up contact with non-responders, providing another copy of the questionnaire at follow-up and sending text message reminders rather than postcards. There is less evidence for effects of precontact by telephone rather than by mail, telephone follow-up rather than by mail, and follow-up within a month rather than later.

Nature and style of questions included

The evidence favours placing more relevant questions and easier questions first, user friendly and more interesting or salient questionnaires, horizontal orientation of response options rather than vertical, factual questions only, and including a 'teaser'. Response may be reduced when sensitive questions are included or when a questionnaire for carers or relatives is included. There is less evidence for asking general questions or asking for demographic information first, using open-ended rather than closed questions, using open-ended questions first, including 'don't know' boxes, asking participants to 'circle answer' rather than 'tick box', presenting response options in increasing order, using a response scale with 5 levels rather than 10 levels, or including a supplemental questionnaire or a consent form.

The evidence favours using a more interesting or salient e-questionnaire.

Who sent the questionnaire

The evidence favours questionnaires that originate from a university rather than government department or commercial organisation. Less evidence exists for the effects of precontact by a medical researcher (compared to non-medical), letters signed by more senior or well known people, sending questionnaires in university-printed envelopes, questionnaires that originate from a doctor rather than a research group, names that are ethnically identifiable, or questionnaires that originate from male rather than female investigators.

The evidence suggests that response is reduced when e-questionnaires are signed by male rather than female investigators. There is less evidence for the effectiveness of e-questionnaires originating from a university or when sent by more senior or well known people.

What participants are told

The evidence favours assuring confidentiality and mentioning an obligation to respond in follow-up letters. Response may be reduced when endorsed by an 'eminent professional' and requesting participants to not remove ID codes. Less evidence exists for the effects of stating that others have responded, a choice to opt out of the study, providing instructions, giving a deadline, providing an estimate of completion time, requesting a telephone number, stating that participants will be contacted if they do not respond, requesting an explanation for non-participation, an appeal or plea, requesting a signature, stressing benefits to sponsor, participants or society, or assuring anonymity rather than participants being identifiable.

The evidence favours stating that others have responded and giving a deadline. There is less evidence for the effect of an appeal (for example, 'request for help') in the subject line of an email.

So although uncertainty remains about whether some strategies increase data completeness there is sufficient evidence to produce some guidelines. Where there is a choice, a shorter questionnaire can reduce the size of the task and burden on respondents. Begin a questionnaire with the easier and most relevant questions, and make it user friendly and interesting for participants. A monetary incentive can be included as a little unexpected 'thank you for your time'. Participants are more likely to respond with advance warning (by letter, email or phone call in advance of being sent a questionnaire). This is a simple courtesy warning participants that they are soon to be given a task to do, and that they may need to set some time aside to complete it. The relevance and importance of participation in the trial can be emphasised by addressing participants by name, signing letters by hand, and using first class postage or recorded delivery. University sponsorship may add credibility, as might the assurance of confidentiality. Follow-up contact and reminders to non-responders are likely to be beneficial, but include another copy of the questionnaire to save participants having to remember where they put it, or if they have thrown it away.

The effects of some strategies to increase questionnaire response may differ when used in a clinical trial compared with a non-health setting. Around half of trials included in the Cochrane review were health related (patient groups, population health surveys and surveys of healthcare professionals). The other included trials were conducted among business professionals, consumers, and the general population. To assess whether the size of the effects of each strategy on questionnaire response differ in health settings will require a sufficiently sophisticated analysis that controls for covariates (for example, number of pages in the questionnaire, use of incentives, and so on). Unfortunately, these details are seldom included by investigators in the published reports [ 3 ].

However, a review of 15 RCTs of methods to increase response in healthcare professionals and patients found evidence for using some strategies (for example, shorter questionnaires and sending reminders) in the health-related setting [ 23 ]. There is also evidence that incentives do improve questionnaire response in clinical trials [ 24 , 25 ]. The offer of monetary incentives to participants for completion of a questionnaire may, however, be unacceptable to some ethics committees if they are deemed likely to exert pressure on individuals to participate [ 26 ]. Until further studies establish whether other strategies are also effective in the clinical trial setting, the results of the Cochrane review may be used as guidelines for improving data completeness. More discussion on the design and administration of questionnaires is available elsewhere [ 27 ].

Risk factors for loss to follow-up

Irrespective of questionnaire design it is possible that some participants will not respond because: (a) they have never received the questionnaire or (b) they no longer wish to participate in the study. An analysis of the information collected at randomisation can be used to identify any factors (for example, gender, severity of condition) that are predictive of loss to follow-up [ 28 ]. Follow-up strategies can then be tailored for those participants most at risk of becoming lost (for example, additional incentives for 'at risk' participants). Interviews with a sample of responders and non-responders may also identify potential improvements to the questionnaire design, or to participant information. The need for improved questionnaire saliency, explanations of trial procedures, and stressing the importance of responding have all been identified using this method [ 29 ].

Further research

Few clinical trials appear to have nested trials of methods that might increase the quality and quantity of the data collected by questionnaire, and of participation in trials more generally. Trials of alternative strategies that may increase the quality and quantity of data collected by questionnaire in clinical trials are needed. Reports of these trials must include details of the alternative instruments used (for example, number of items, number of pages, opportunity to save data electronically and resume completion at another time), mean or median time to completion of electronic questionnaires, material costs and the amount of staff time required. Data collection in clinical trials is costly, and so care is needed to design data collection instruments that will provide sufficiently reliable measures of outcomes whilst ensuring high levels of follow-up. Whether shorter 'quick and dirty' outcome measures (for example, a few simple questions) are better than more sophisticated questionnaires will require assessment of the costs in terms of their impact on bias, precision, trial completion time, and overall costs.

A good questionnaire design for a clinical trial will minimise bias and maximise precision in the estimates of treatment effect within budget. Attempts to collect more data than will be analysed may risk reducing recruitment (reducing power) and increasing losses to follow-up (possibly introducing bias). Questionnaire design still does remain as much an art as a science, but the evidence base for improving the quality and completeness of data collection in clinical trials is growing.

Armstrong BG: Optimizing power in allocating resources to exposure assessment in an epidemiologic study. Am J Epidemiol. 1996, 144: 192-197.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hill AB: Observation and experiment. N Engl J Med. 1953, 248: 995-1001. 10.1056/NEJM195306112482401.

Edwards PJ, Roberts I, Clarke MJ, DiGuiseppi C, Wentz R, Kwan I, Cooper R, Felix LM, Pratap S: Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009, 3: MR000008-

PubMed Google Scholar

International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use: ICH harmonised tripartite guideline, statistical principles for clinical trials E9. http://www.ich.org/LOB/media/MEDIA485.pdf

CIOMS: Management of safety information from clinical trials: report of CIOMS working group VI. 2005, Geneva, Switzerland: Council for International Organisations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS)

Google Scholar