- Videreuddannelse og kurser

- Biblioteket

- Studiestart pædagogisk assistent

- Sådan finder du din uddannelse

- Ledige studiepladser den 26. juli

- Ledige studiepladser

- Studiestart

- Uddannelser

- Administrationsbachelor

- Bioanalytiker

- Ergoterapeut

- Ernæring og sundhed

- Fysioterapeut

- Grafisk kommunikation

- Pædagogisk assistent

- Socialrådgiver

- Sundhedsadministrativ koordinator

- Sygeplejerske

- Det kan du også

- Online uddannelser

- Merituddannelser

- Deltid: Socialrådgiver

- Ambulancebehandler

- Elitesport og uddannelse

- Videreuddannelse

- Offentlig administration

- Ledelse og projektledelse

- Vejledning og beskæftigelse

- Socialområdet

- Undervisning og pædagogik

- Ungdoms-, voksen- og erhvervspædagogik

- Andre muligheder

- Korte forløb og konsulentydelser

- Søg efter uddannelser, moduler m.m.

- Videnstemaer

- Forskningsprogrammer

- Barndomspædagogik, bevægelse og sundhedsfremme

- Skole og undervisning

- Socialt arbejde, forvaltning og socialpædagogik

- Sundhedsfaglig praksis

- Om UC SYD Forskning

- Center for Mindretalspædagogik

- Job ved UC SYD

- Find en medarbejder

- Videnstemaer UC SYD Forskning sætter fokus på særlige videnstemaer. Mød vores eksperter. Læs om vores forskning og hvordan du kan bruge den i praksis.

- Om UC SYD Hvem er vi? Læs alt om UC SYD her.

- Job ved UC SYD Find ledige stillinger, og hør hvordan det er at arbejde på UC SYD.

- Presse Vi giver dig oversigten over alle vores pressehistorier.

- Find en medarbejder Leder du efter en af vores medarbejdere? Søg og find personen her.

International

Explore. Exchange. Experience. Bring the world home

- Teacher Education

Challenge yourself and shift your expectations

- 01 Introduction

- 02 What will you learn?

- 03 Admission

- 05 Study environment

- 06 Language

- 07 Become a student for a day

- 08 Contact us

Introduction

We invite you to Denmark to accomplish an international BA in Education in a wide variety of subjects.

Combine your study with unforgettable cultural experiences:

- meet new friends from all over the world

- learn new languages to broaden your career opportunities

- gain independence and confidence while living away from home

- challenge yourself and shift expectations of what you are able to achieve!

Open International counselling via zoom

We invite you to open online counselling It is important that you participate from the start, as there will be a joint presentation.

If you have any log-in problems, you can send an email to [email protected]

- 23 April 2.30-4.00 PM

- 12 June 2.30-4.00 PM

- 25 June 2.30-4.00 PM

- 7th August 2.30-4.00 PM

Click here to attend a meeting (opens a Zoom meeting)

Why Denmark?

If you are still considering whether you should choose Denmark as the country of your international study experience, we would advise you to research on the Danish Educational System and consider the following statements:

- Our qualifications are recognized all over the world

- We concentrate on your unique personality and talents

- We promote creativity and innovation

- We provide a fair balance between theory and practical experience

- You are safe here (Denmark is the safest country in Europe)

Four students experiences of Denmark

International student

Meet Melina: ‘Living abroad has made me realise I am more German than I thought I was’

Meet Marcus: ‘I feel happier than I have been in a very long time’

Meet Priya: ‘I can’t help but ask myself, “why do I deserve a better life than the schoolchildren I left behind in India?”’

Meet Flóra: ‘When my Slovak friends told me about life in Denmark, I didn’t believe them’

What will you learn?

Structure and curriculum.

If you would like some more general information about the Bachelor of Education programme, please check here .

For our specific programme, there will be a specially designed syllabus for the incoming international students. Here is an overview of the structure.

Bachelor of Education is a four-year program, which qualifies you to be a teacher of primary and lower secondary levels in Denmark (see facts on Danish educational system) in three subjects of your choice. This program is a mixture of theoretical instruction and educational studies combined with the practical experience of teaching.

During your first year you are taught to become an English teacher. You will be integrated in a class of Danish students.

You may have heard of former students who had German as their first subject. There have been new rules, and from August 2023 you must start with English. You can then choose German as your second or third subject.

You will also be studying subjects in psychology and education taught in English, as well as participating in the first period of teaching practice at a school. During the first year, you will receive intensive training in the Danish language at the local language center, planned in cooperation with the college (read more about language). As a student at this international teacher education, you must live in Denmark. For all living in Denmark, you have free Danish Lessons at the local language center. UC SYD will pay the deposit for you at the Haderslev Language center. Living in Denmark supports your learning of the Danish language. In addition, it is free for you to study Danish. However, you must have lived in Denmark for a maximum of two years before starting the teacher training course if you are not good at Danish.

From the second year and onwards you will follow most of the curriculum in Danish; however, you will still have English as a teaching subject at second year. Furthermore, you are to choose two more subjects as your teaching subjects: science, physics/chemistry, geography, biology, German, art, music, home economics, sports (PE), history, social science, religion (RE). (Read more about the Structure and Curriculum).

The academic year runs from Mid-August to January (autumn semester) and from Mid-January to Mid-June (spring semester). Exams take place in June and January.

Teacher education in Haderslev has a strong profile in using new technologies in teaching and learning, thus, for example, the use of interactive boards, blended learning. One of the characteristics for the Danish way of teaching and learning is a friendly and informal atmosphere, which is highly appreciated by our international students. The syllabus is a mixture of lectures, group work, student presentations, and project-oriented learning. Read more here.

Florence and Julia interned at Starup School

Florence from Kenya and Julia from Finland interned at Starup School

Post-graduation opportunities

After graduating the Danish Bachelor of Education, you have a great variety of job possibilities. First of all, you are fully prepared to be a teacher in Danish primary and lower secondary schools: public, private and international. Moreover, as a native language speaker you have even better chances to get employed as a foreign language teacher compared to Danish students.

A Danish Bachelor of Education Degree is fully recognized and accepted in Europe and all over the world. However, you might need to take some additional courses or practical lessons connected with teacher education, according to the requirements of the country in question. In case you are not planning to work straight after graduation, you can apply for Master's Degree based on your Bachelor of Education at Universities in Denmark or other countries.

No matter what you choose to do after graduation, you can be sure you are well prepared for a future full of new horizons and opportunities!

Admission requirements

The admission requirements for international students can include one of the following certificates:

- The European Baccalaureate (EB)

- The International Baccalaureate (IB)

- Zeugnis der Allgemeinen Hochschulreife (Abitur)

- The Option Internationale du Baccalauréat (OIB)

- Baccalauréat Français International (BFI)

- Another foreign qualifying examination certificate that can be equated with a Danish upper secondary school leaving certificate.

You are also welcome to apply if you are in the final year at secondary school.

To see if your qualifications fulfill the requirements for Higher Education programmes in Denmark, please check the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Higher Education .

In addition to these high school requirements, you must also

- Take up residence in Denmark

Specific requirements

Applicants applying for the International Teacher Education Programme must have an average mark of 7,0 according to the Danish grading scale.

If the average mark is below 7,0, or if you come from a high school not recognized by us, you will have to participate in an online admission interview. Furthermore, if you are just finishing your upper-secondary school in June and do not have the final results yet, you will also have to participate in an online admission interview.

The purpose of the admission interview is an individual screening of your suitability for study in relation to both academics and profession.

When we have assessed your application, you will receive more information on how to book an online admission interview on nemStudie.dk.

Just for information, you also have to attend a guidance interview in addition to the admission interview

English language requirements:

The International Teacher Education Programme is taught in English the first year, therefore it is required for applicants to submit proof of English proficiency equivalent at least to English B level in Denmark to enter the program.

We need your school leaving certificate with a specialization document of English or certificates in one of the following English tests:

- ets.org : minimum score 83

- coe.int : minimum score B2 (for students studying to become English teacher)

- ielts.org : minimum score 6,5

If you haven´t completed one of the above tests, you must submit a verification form from your school. The verification form must show how many English lessons you have or will completed during the final three years of your high school.

You can use the following verification form if your school doesn’t provide one.

- Verification form

1) Login to www.optagelse.dk (open from February 1st) and apply under the red arrow “Søg videregående uddannelse” (apply for higher education). Remember to upload all your documents.

You can read a guide here .

2) Send your signature page no later than 15 March at 12:00 noon to [email protected]

3) Upload a brief letter of motivation for applying to become a teacher in Denmark and your CV to your application.

If you have any questions you can write an e-mail to [email protected] or [email protected]

Facing an online admission interview?

If your average grades are under 7, or if you do not know your final average grades yet, you will have to attend an online admission interview. You might think that sounds a bit scary. But an entrance interview is not an exam. It’s an interview and a discussion in which you can tell us why you want to apply for teacher training.

Most interviewees (over 90%) are offered a place after attending an admission interview, which means there is every good chance of you being accepted.

You will be issued a case for the first part of the interview and an article for the second part. You will attend two different interview rounds, each lasting 15 minutes, plus preparation time.

One interview will focus on your personal motivation for applying to teacher training and for wanting to become a teacher. It will be based on a case with dilemmas that common in the work of a teacher. These can be a conflict from the playground, or a situation in the classroom. You will take the role of the teacher to deal with the problems in the case.

The second interview, which follows straight after the first one, focuses on your ability to read texts that address aspects from school. What you need to demonstrate is that you can identify key points in those texts. Your ability to analyse will be in focus here.

You will be assessed based on your:

- Cognitive ability

- Ability to work with others, and your personal integrity

- Communication ability

- Ethical approach

- Understanding of vocation-related texts, and how you deal with them

The admission interview will be conducted in English, and the texts will be in English.

All interviews will be carried out online.

The admission interviews usually take approximately one hour and 15 minutes overall, you may experience extended time for example if there are connection problems.

Make sure your webcam and audio are working and that you have a stable Internet connection before your online admission interview.

The day before the admission interview, you will receive an e-mail with a link to participate the online admission interview.

Please note that the invitation will be send to the e-mail you have given when you applied on optagelse.dk .

Furthermore, think about why you want to be a teacher. What is it that attracts you? What kind of teacher do you want to become? What challenges are you prepared to tackle?

The interviewer will not tell you whether you have passed or failed. After the interview you will receive a notification e-mail informing you that your score is ready. In order to see your total score, you must use the link you received when you booked your online admission interview. You cannot use the notification e-mail.

To bed admitted to the teacher training programme, you must score a minimum of 30 points.

All applicants who have been accepted to the teacher training programme will be notified of this on 26th July at nemStudie.dk.

If you have been to an online admission interview and your score was below 30 points, you will prior to the above date be informed that your application has been rejected.

Our concept for pre- and onboarding

Read more about our pre- and onboarding of all accepted students here.

Students within the EU/EAA/Switzerland are not required to pay tuition.

There is a tuition fee for all full-time degree students who hold a citizenship from outside EU/EAA/Switzerland. The tuition fee is approx EUR 5000 per semester.

If you want to learn more about the cost of living in Denmark and accommodation we have collected this information on our page for incoming students. Click here if you want to learn more.

Study environment

The college campus is situated in the centre of Haderslev. The oldest buildings date back to mid 19th century, and our campus is a charming mixture of old and new. You will have around 650 fellow education students.

Haderslev is a medieval town with about 30,000 inhabitants, beautifully situated at the east coast of Southern Jutland on a 12-kilometer-long fjord and surrounded by an extensive lake system, 50 km north of the Danish-German border. There are many leisure time possibilities like sports, concerts, cinema, cafés, etc.

Read more about Haderslev.

Alongside the usual course offered to all teacher students, you will receive intensive training in the Danish language. The Danish language training is free of charge if you reside in Denmark.

During the first year, all lessons are taught in English.

As part of the degree course, you must choose 3 teaching subjects (your specialized subjects).

First teaching subject, English

During the teacher education, you must choose 3 teaching subjects (your specialized subjects).

All our international students must choose English as the first teaching subject. You must be sufficiently fluent to participate in classes where English is the language and be able to become a teacher of English. During the first year, all lessons are taught in English.

An intensive course in Danish

During the first year you must take an intensive course in Danish alongside your other studies, preparing you to be taught in Danish from your second year.

If you already live in Denmark, you must be aware if you can be offered free Danish lessons, as it is only free for up to 5 years after you have arrived in Denmark. At study start you must have at least 3 years left of this offer, in order to finish learning Danish for free. After 5 years you must pay for your lessons yourself and the price is app. 20,000 DKK per semester. If you have any questions in relation to the above, you can contact Haderslev Sprogcenter - Dansk i centrum as your training in the Danish language will be held here. For more information on Danish language education, you can visit Danskuddannelse til voksne udlændinge m.fl. | UddannelsesGuiden (ug.dk). At speakdanish.dk you will find a few links to online Danish lessons so you can start in advance.

If you need further information which is not provided in English, you can use the automatic translator from online translations.

Become a student for a day

Take the opportunity to visit us at Campus Haderslev and follow an ordinary study day along with the current students, so you can get a sense of what the lectures and the educational environment are really like. During the day students and teachers are available for a chat. You can ask all the questions you need answers to.

For more information about your options, please do contact us (email [email protected] ). We are always ready to help. We look forward to meeting you!

Do you have any questions? Please contact us

Contact our international department.

Contact our team of counselors

[email protected] 7266 2250

Press enter to search

Teacher Education

Profession- and development-oriented primary and lower secondary teaching

About the BA teacher education

Our full degree programme at bachelor level is taught in Danish. If you are fluent in Danish, Swedish or Norwegian, you may study our full degree programme.

The BA in Teacher Education at KP offers an open and inviting study environment both academically and socially. The teaching incorporates different methods, including group work, innovative project work, discussions and lectures, and its primary focus is to provide you with the skills to plan both the academic as well as the educational aspects of your future teaching.

If you want to become a teacher, you must be skillful and knowledgeable within your subject area, authoritative, empathetic and compassionate in your actions and most importantly wanting to see others succeed.

Each semester, we welcome exchange students from our partner institutions.

Courses are offered both at Campus Carlsberg and Nyelandsvej in Copenhagen. The two addresses are close to each other.

Please be aware that only students who apply for 30 ECTS will be accepted

Autumn semester 2024

Courses for exchange students:

Courses taught in English

- Processes in language acquisition and communication skills (English)

- Cultural Studies

- Creativity and Experimental processes (Arts and Crafts, Visual Arts)

- Didactics of dialogue and reconciliation (History, Religious studies)

- Integration of physical activity in everyday teaching practice

- Musical expression in Teaching and Learning

- International practicum*

KP does not guarantee admission to the courses. Module availability is dependent on a minimum and maximum number of registered participants.

*Notes about International Practicum

The practicum takes place in Danish public schools, in which the main language of teaching is Danish. Exchange students will teach in either English, German or French. Students may teach a wide range of different subjects. Due to language barriers, international students can only teach children between the ages of 9 and 16 (3 rd to 9 th grade). The practicum takes place in groups of international students. The group members go to the practicum school together and plan and perform their teaching activities collaboratively. Please note that the practicum schools are situated in the Greater Copenhagen area, which means student must expect some travel time and transportation expenses.

Course taught in German:

- Deutsch als Fremdsprache: Sprachlehr- und Lernprozesse in Deutsch als Fremdsprache

Courses taught in Danish

- Please find course descriptions on our website

Spring Semester 2025

Courses are subject to change. An updated course list will be available in August 2024 at the latest.

KP does not guarantee admission to the courses. Module availability is dependent on a minimum and maximum number of registered participants

- Processes in language acquisition and communication skills (english)

- International practicum

Application for exchange students

Students must get nominated by their home institution. Please nominate your students through our online nomination survey.

If you haven’t received a link for that survey, please write to [email protected] .

Nominated students will receive an e-mail with information about application and accommodation.

Autumn Semester 2024

Deadline for nomination.

15 th March 2024

Deadlines for application

Students who need a study visa: 1 st April 2024 Students who do not need a study visa: 1 st May 2024

Semester dates

Mid August – end of December 2024 (including welcoming week)

September 15th 2024

Students who need a study visa: October 1st 2024

Students who do not need a study visa: November 1st 2024

Start date: In mid -January 2025

End date: At the beginning of June 2025

- How to apply

Please find information about application, accommodation, visa, insurance etc. on our How to apply-page.

International coordinator: Sabine Lam [email protected]

Teacher Education in the Nordic Region pp 195–208 Cite as

Teacher Education in Denmark

- Lis Madsen 4 &

- Elsebeth Jensen 5

- Open Access

- First Online: 14 March 2023

1870 Accesses

Part of the book series: Evaluating Education: Normative Systems and Institutional Practices ((ENSIP))

One recurrent feature of the four-year Danish teacher education programme at university colleges is the challenge of attracting and retaining qualified student teachers. Many changes have been implemented to address this and other challenges. To gain a better understanding of the developments from the recent reforms and the subsequent solutions to educational issues, the authors of this chapter examine the various teacher education laws written during this period. The purpose is to explore changes in Danish teacher education, primarily after the turn of the millennium. The main trends are (1) a more profession-oriented teacher education and (2) an increased focus on academic subjects, reflected in the demand for a stronger knowledge base throughout teacher education. However, the development of Danish teacher education must also be viewed in light of several major national and international societal changes. Several areas of teacher education are intended to be developed in the coming years, including improvements in teaching methods in teacher education, better collaboration with practice schools, improvements in student teachers’ opportunities for in-depth studies in subject areas, and a renewed focus on Bildung in education and teacher education.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

1 Introduction

The development of Danish teacher education cannot be understood in isolation but must be viewed in light of several major national and international societal changes. In this chapter, we focus on the changes in Danish teacher education, primarily after the turn of the millennium. These changes are part of a long historical development, and in many ways, they reflect trends that are also seen in other countries. Educational policy development is described elsewhere in this edited volume, so we touch upon this aspect only briefly. First, we examine the characteristics of the changes in Danish teacher education effected through recent reforms. One recurrent feature in several Nordic countries is the challenge of attracting and retaining qualified student teachers. We therefore highlight the enrolment and retention challenges over several years, along with the political initiatives for the past two reforms to address these challenges. Finally, we investigate the current situation and discuss possible further steps.

2 The External Framework for Teacher Education

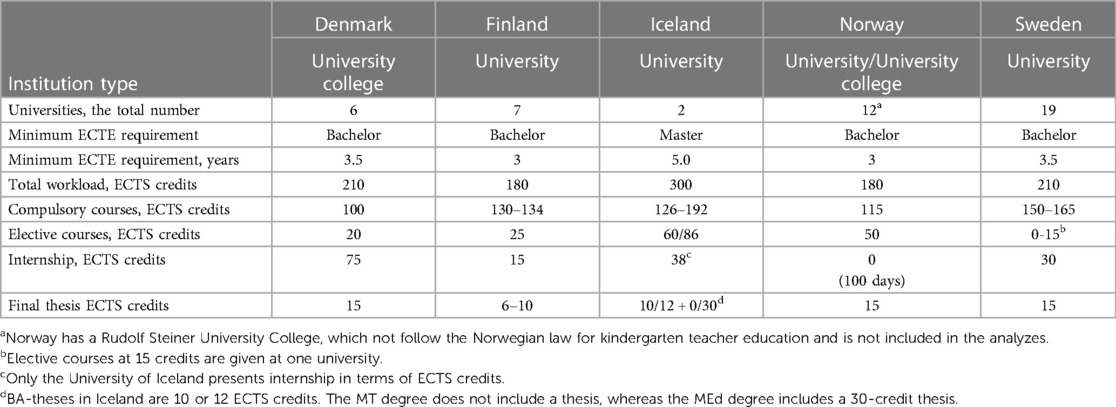

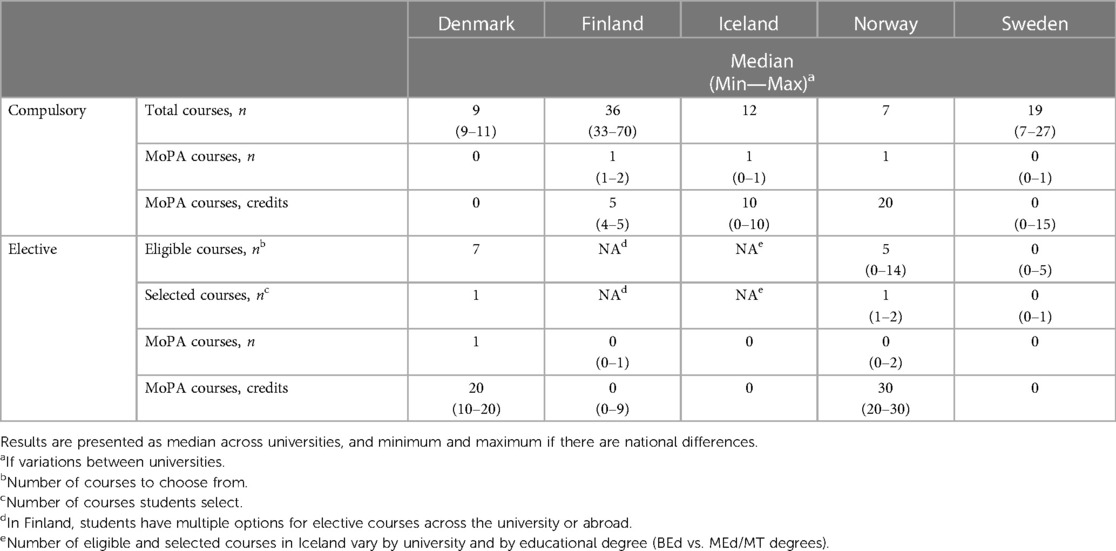

Chapters 1 and 2 present several issues of major importance for the development of teacher education in Nordic countries. In Denmark, it is crucial that education policy has become ‘highly political’ and is perceived as central to the country’s competitiveness in the global market. In this context, international assessments and comparisons have become key factors for understanding which countries have exemplary education systems and which have inadequate systems. Political demands for uniformity expressed in the Bologna Process with the introduction of a European qualification framework had a decisive influence on the development of teacher education in Denmark. New measures included the common European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) from 2001, which emphasized management according to clear and measurable objectives and a focus on output rather than outcomes.

Over the past 30 years, the Teacher Education Act has been amended four times: in 1991, 1997, 2006 and 2012 (with subsequent implementations in 1992, 1998, 2007 and 2013, respectively). During the same period, the Act on the Folkeskole, covering Danish primary and lower secondary schools, underwent major changes in 1993, 2003, 2006 and 2014, and in this area, there were several major and minor adjustments at the executive order level as well.

These frequent reforms of teacher education have been part of a major reform of the public sector in Denmark since the beginning of the 2000s. Thus, they are not special to teacher education but can be regarded as indicators of the major changes that characterise the public sector, which is currently being reinvented (as discussed by Pedersen et al., 2008 ). To gain a better understanding of the developments during the recent reforms and the subsequent solutions to educational issues, we will examine the content of the various teacher education laws during this period more closely.

3 The Struggle for the Professional and Educational Content of Teacher Education

The issue of what teacher education should comprise is reflected in the tension between the academic mission and the professional mission. Since 1930, teacher education has had a four-year duration but has changed from a teacher training college programme to a professional bachelor’s degree (2000) for primary and lower secondary school teachers. In parallel with this development at the structural level, a similar development has occurred in the content areas. The two developmental strings are interrelated in that they both entail a shift to a more academic orientation and a clearer professional line of education. A review of the past four laws clearly shows that education has been evolving and that the various reforms can be viewed as steps in this constant process of change.

Denmark participated in the first large international literacy survey in 1991. Politicians lost their confidence in schools, as Denmark unexpectedly received a rating very close to the bottom, whereas the other Nordic countries were at the top. The author, Mejding ( 1994 ), aptly called the survey Den grimme ælling og svanerne ( The Ugly Duckling and the Swans ). Since then, politicians have paid close attention to schools’ national and international evaluations and comparisons to document the extent to which they deliver the quality and standards of education required. Over the same period, an overhaul of teacher education has also been underway, motivated by the assumption that if learners fail in literacy and numeracy, something might also be wrong with teacher education. In particular, the reforms have focused on three key issues:

Should a teacher primarily be a generalist who is competent in many school subjects or a specialist who can teach only a few subjects?

What is the range of teaching practice in teacher education? What is the proper ratio between theory and practice in student teachers’ professional development?

What is the proper ratio between academic school subjects and pedagogical subjects (general teaching qualifications)?

However, this is not a straightforward account of the reforms or changes that are explicitly based on research knowledge of teaching skills. Rather, it is a study of different notions of what it takes to educate qualified teachers (e.g. whether to focus on school subjects or on teaching pedagogy in general). The reforms clearly reflect different political attitudes towards the requirements for qualified teachers. This means that the various reforms have been characterised by political compromises instead of a settled pedagogical approach. Moreover, they have primarily emphasised structural and academic content elements rather than pedagogical changes in teaching and work methods. Below, we take a closer look at how the three issues have been weighted in recent reforms.

4 The Teacher as a Generalist (with Teaching Competence in Many School Subjects) or a Specialist (with Teaching Competence in a Few Subjects)?

In the late 1990s, there was a shift in views on whether curriculum of teacher education should be broad or deep, basic or specialised. Until 1997, teachers were trained as unit teachers who could teach various subjects at the primary school level and two subjects in lower secondary school. Teacher training was divided into two parts: a basic part and a specialisation part. In the basic part, student teachers took a number of basic subjects, which qualified them to teach primary school classes. In the specialisation part, they took two majors, which qualified them for lower secondary education. With the 1997 Act, a break with the former unit schoolteacher concept occurred, with student teachers taking four school subjects named majors but no subjects for primary school.

With the 2007 reform, the number of majors was reduced to two or three (typically two). In 2013, the number of majors remained the same, but with a shift towards qualifying in three subjects. With the 2007 Act, grade specification was introduced in the two majors (Danish and mathematics), and in 2013, it was expanded to include English and sports. This development can be considered an example of the change in views on teacher and teaching skills and as part of a shift towards increased specialisation and a more academic orientation in teacher education.

5 Teaching Practice and the Role of the Profession in Teacher Education

The proportion of practice in teacher education has not changed considerably in the past four teacher education laws. The duration of internships has been approximately half a year’s work (30 ECTS), divided into three to four internship periods. Despite this steady theory-to-practice ratio, there have been changes in internship placements, the length of individual obligatory practice periods and the interrelation between academic school subjects, pedagogical subjects and internships.

With the most recent amendment of the teacher education programme in 2013, internships received a boost, not in proportion but in formal requirements, namely the introduction of final teaching practice exams after all internship periods. In addition to teaching practice in all modules, practice tasks must be included in the curriculum of each module. Such tasks can be anything from observation of classes taught by professional teachers to student teachers practising their own academic subjects in schools or participating in specific school activities. Thus, there is now a sharper focus on various opportunities for student teachers to perform teaching practice tasks throughout their education and, therefore, on increased collaboration with schools, even though the internships have not been extended.

6 Basic Subjects: The Pedagogical Area

In the 1991 law, the pedagogical field was weighted to comprise approximately an entire year’s studies. This was almost halved in the 1997 law and then adjusted in 2007 and again slightly more in 2013. However, it is more important to examine the content of the subject area than its scope. Before examining the shifts in various laws, we will take a brief look at the pedagogical subject area of teacher education as a whole. Over time, it has been difficult to determine a concise content and knowledge base for this area. Several issues have been the subject of constant debate: Should it preferably consist of philosophical and ethical approaches to learners’ upbringing and general formation? Should it include political and sociological analyses of the school’s function in society? Should it introduce psychological issues related to children’s general development and various learning theories? Should it primarily comprise pedagogical approaches and methods for effective teaching?

In his PhD dissertation, Hans Harryson asks, ‘What is the purpose of the pedagogical subjects in teacher education in the 2010s? How do the pedagogical subjects contribute to the development of student teachers’ teaching competences?’ ( 2018 , p. 17; translated by the authors). The questions are examined, among other ways, through a comparative analysis of the subject area in Denmark, Norway and Iceland. Although it is impossible to present an in-depth discussion of all the results here, we would like to emphasise that we are far from finding a clear answer regarding the content and purpose of the pedagogical subject area. Teacher educators view it primarily as a theoretical subject which should preferably keep some distance from practice (p. 198), whereas student teachers mainly expect to acquire tools and methodologies that they can use in practice. Another interesting result is that, to a great extent, both student teachers and teacher educators see the justification of the subject area as ‘closely linked to (1) the inadequacy of the academic subjects and (2) the inadequacy of teaching practice’ (p. 191). According to Harryson ( 2018 ), it remains somewhat unclear what the subject teachers’ purpose and content are. Teacher educators use words and phrases such as the following: ‘The subject area helps shape the student teachers’, ‘DNA, backbone, identity’, ‘Professional maturation’, ‘Professional vocabulary’, ‘Grasp of the profession’, and ‘Student teachers’ ability to view teaching and learning in nuanced ways and from different perspectives’ (p. 203).

Harryson’s thesis ( 2018 , p. 45) shows that: (1) There are few (and scattered) studies focusing on pedagogical subjects in teacher education, (2) There are even fewer studies focusing on pedagogical subjects in integrated teacher education, and (3) Most available studies are based on educational psychology and not on other ‘non-specific courses’ (Lohse-Bossenz et al., 2013 , p. 546).

Just as it has been difficult to grasp and clearly define the pedagogical subject areas, it has also been difficult to clearly define the subject area’s knowledge base. These difficulties have been a recurring theme in the recent changes to the subject area. The greatest change took place between the 2006 Act and the 2013 Executive Order, namely the replacement of traditional subject pedagogy, psychology and general methodology. The teacher’s foundational competences are subdivided into two clusters: ‘Pedagogy and the teaching profession’ and ‘General education’. ‘Pedagogy and the teaching profession’ consists of four areas of competence: (1) pupils’ learning and development, (2) general teaching proficiency, (3) special needs and remedial training, and (4) Danish as a second language. The other cluster, ‘General education’ (‘almen dannelse’ in Danish) consists of the study of Christianity/philosophy of life/citizenship and prepares student teachers to implement the mission statement of the Danish school system: to develop professional ethics and deal with complex challenges in the teaching profession in the context of cultural, value-based and religious pluralism.

The shift to a competence–goal orientation in school practice has challenged the Danish pedagogical field, which has been characterised by a tradition of philosophical–analytical and sociological–critical perspectives on school and teaching and a lesser emphasis on student teachers’ specific competence development in relation to the teacher’s work. For example, a comparative analysis of the content of teacher education programmes in Canada, Denmark, Finland and Singapore found that normative philosophical literature was considerably more prominent in Denmark than in the other countries (Rasmussen et al., 2010 ).

With each amendment of the law, there have been new and more time-consuming problems for any new teacher education to solve. Along with the aforementioned shift to a more academic orientation, teacher education has become increasingly oriented towards the profession. In the majors, and subsequently in the teaching subjects, methodology has increasingly become an integral part of the academic subjects, which have moved away from being mini university studies. The 1992 Act on teacher education primarily focused on theoretical and analytical approaches to education. In the subsequent changes, the future profession of the student teachers gradually came into focus. In 2007, as a concrete result of this movement, a compulsory pedagogical element was introduced into the academic majors. As mentioned above, the 2013 Executive Order also requires continuous collaboration with schools for school practice in all disciplines. At the same time, there has been a shift from content-driven to goal-driven education in terms of the competencies that a qualified teacher needs.

7 Enrolment in Teacher Education

During the period in question, it has been challenging to attract the most talented students to teacher education and to reduce the dropout rate. Furthermore, there has been a shortage of qualified teachers during some years. Currently (2022), 10–17% of the permanent teachers in Danish schools do not go through the regular teacher education channel. In 2002, people with different degrees and work experiences were given the opportunity to qualify as teachers in a shorter time by pursuing merit teacher education. Initially, there was great concern about this new type of schoolteacher, not least on the part of The Danish Union of Teachers. However, merit teacher education has now a good reputation. Merit teachers are older when they graduate than those with an ordinary teacher education and have experience from other areas, which they bring into the school. Merit teacher education does not lead to a professional bachelor’s degree but is supplementary education of 150 ECTS, pursued under the Law on Open Education. The programme consists of academic and pedagogical subjects and an internship period of 10 ECTS. The number of applicants has varied over time. During periods of teacher shortages, political pressure to train more merit teachers has intensified. For instance, there is currently strong political interest in recruiting more people to become merit teachers (for instance, by developing attractive education models that combine studies and employment). However, merit teacher education can reduce but not solve the enrolment problem.

Ordinary teacher education is dimensioned to ensure (among other things) a balance between training sites and a balance of teacher education located in urban and rural areas. However, at the national level, the required dimensions have not been achieved, and few university colleges (in Danish: professionshøjskoler) have had more applicants than could be admitted. To meet the challenge of attracting the best students and reducing the dropout rate, the past two reforms have paid attention to tightening the teacher education admission requirements.

8 Admission Requirements

With the 2007 reform, changes to the admission requirements for teacher education courses were introduced despite problems with enrolment. The then-Minister of Education, Bertel Haarder, argued that the reform might initially lead to a decline in the number of applicants but would make teacher education more attractive in the long term. One admission requirement was linked to the academic majors, not to the pedagogical subjects. There were also requirements for a minimum grade in a particular subject in upper secondary school to take the corresponding academic subject in teacher education programmes. For example, to take Danish literature and language, a student should have an A-level grade of 7 in that subject. (A-level is the highest secondary school level, and 7 is an average grade on a 7-step scale from −3 to 12).

The most recent reform of 2013 was still aimed at raising the admission level, but this time, the requirement was changed to a grade of 7 as the minimum average of the total upper secondary school grades. Students who do not have an average grade of 7 can apply for admission in ‘quota 2’ and be admitted through an admission interview. The admission interviews drew inspiration (among others) from the University of Southern Denmark and the so-called multiple mini-interview concept, in which the applicants visit two stations as part of the admission interview. The applicants are tested qualitatively, and the interviewers assess their answers in six content domains: motivation, ethical ability, cooperative ability and integrity, communicative ability, cognitive ability, and text comprehension and word processing.

An evaluation of the admission interviews by the Danish Evaluation Institute ( 2013 ) drew the following overall conclusions:

The dropout rate among those admitted through quota 2 has fallen slightly.

The average grade for admitted students has risen, and more students with high grades are recruited and retained than before.

There is a significant inverse correlation between the content domain of motivation and the likelihood of a student dropping out.

Another evaluation of the admission interviews (The Danish Evaluation Institute, 2017 , p. 5) draws these conclusions:

The admission interviews have helped reduce the dropout rate among students admitted via quota 2.

Of the six interview content domains, only motivation indicates the probability of a student dropping out with some certainty.

Following the introduction of admission interviews as part of the new quota 2 admission requirements in 2013, students with high grades have increasingly been recruited and retained.

After the introduction of the new admission system in 2013, nationwide intake decreased by approximately 25% but subsequently rose again. In 2012, 3660 students enrolled nationally. In 2013, the number dropped to 2936. Later the number of applicants increased, but not since 2014 have so few applied for teacher education via quota 2 as in 2022. Compared to 2021, 17% fewer have applied for teacher education (Bjerril, 2022 ). Although the introduction of the new admission system cannot fully explain the decline, it has certainly been a contributing factor. For example, we find that some applicants do not show up for the interviews. One of the reasons for the introduction of the new admission system was the assumption that better and more competent students would mean better retention. However, this assumption has been supported only partially (see the next section).

9 Dropout from Teacher Education Programmes

The dropout rate in teacher education remains high. Moreover, it remains high throughout the course of teacher education, whereas in other professional programmes, it falls significantly after the first year. The reasons for dropping out vary widely among students, and it is rarely possible to identify a decisive factor. However, a study conducted by the Danish Evaluation Institute ( 2013 ) found slightly different reasons for dropping out of teacher education programmes depending on when students chose to drop out. Early dropouts cited a wide variety of reasons, such as poor introductory courses, lack of knowledge about the education provided, parallel employment and distance to the educational institutions. For late dropouts, the distance to practice schools and the perceived low academic level appeared to be important factors.

10 Current Status of Teacher Education in Denmark

The discussion about teacher education has been ongoing for a long time but has intensified with the recent reforms. One of the problems is politicians’ disagreements over what kind of education they want. This means that laws and regulations are the result of compromises between competing goals (e.g. more or fewer academic subjects or pedagogical subjects). The rationale behind the teacher education reform of 2007 was the desire for in-depth academic studies, especially in the major school subjects (mathematics and Danish) and science. At the same time, there was a recognition of the sharp difference between teaching primary and lower secondary school classes. This difference led to the division of the major subjects into two levels so that they became broader in scope. An evaluation of the 2007 reform by a follow-up group (The Danish Evaluation Institute, 2011 ) identified several strengths (e.g. the in-depth academic studies) and weaknesses (e.g. a lack of opportunities for internationalisation). Although the group’s criticism was not particularly harsh, a new reform followed in 2013.

The 2013 reform marked a new break in several areas and is perhaps best understood in light of international calls for governance according to competence goals and a modular structure, as was known from other educational programmes in Denmark and abroad. At the same time, the shift towards more profession-oriented education initiated with the 2007 reform continued. Moreover, the trend towards an increased focus on academic subjects (which started in 2001, when formal education became a professional bachelor’s degree programme) was strongly reflected in the demand for a stronger knowledge base throughout the programme.

Interestingly, neither the evaluation of the 2007 reform nor that of the 2013 reform identified challenges in education sufficiently serious to call for major revisions. Nevertheless, the teacher education programme introduced in 2013 broke with previous programmes in essential areas. An expert group’s evaluation of the 2013 reform (Danish Agency for Higher Education and Science, 2018 ) highlighted five strengths and three weaknesses. The general conclusion was: ‘Teacher education is thus well underway but will require continued development in several areas to ensure that, as a whole, it lives up to the goals of high quality and clear relevance to the Danish school’ (p. 10, translated by the authors).

Despite the predominantly positive evaluations, there is general dissatisfaction with teacher education, both among politicians and more broadly in the public debate. In March 2019, the government formed a commission whose mission is to look fundamentally at whether Danish teacher education is appropriately structured, has a sufficiently high professional level and whether teacher education is otherwise in line with and follows international developments. The goal was for Denmark to have a long-term sustainable teacher education. Teachers should obtain a strong academic and methodological foundation to both deliver high-quality education and be equipped to apply and evaluate new approaches and methods in line with the development of the primary and lower secondary school in Denmark. Further, the government declared that it is not necessary to make amendments according to the changing trends in primary and lower secondary school (The Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science, 2019 ). This complex mission reflects the dual focus on academic subjects and professionalism that has become increasingly pronounced throughout the recent reforms.

In summer 2019, there was a change in government, the new government dissolved the commission before it began its work. However, the new government started in 2020 a revision of teacher education. The focus is on development within the frame of a four-year bachelor’s degree:

The government has a high level of ambition for teacher education in Denmark. There are a number of challenges that must be taken care of to make sure that teacher education will attract more talented and motivated students from all over the country. At the same time, it is necessary to develop concrete solutions in order to ensure better coherence and a higher professional level. It is also important to push students to study harder and establish a closer connection with practice in schools. Based on this, the government is starting a process of development in order to rethink teacher education (The Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science, 2020 ).

The development work was centred on three main themes:

Strengthened practice training and connection to practice.

Increased study intensity, better professional progression, and a better retention and enrolment

Stronger knowledge base for teacher education.

11 What Will the Next Steps Be?

The current political discussions partly concern the duration of education. The discussion on the level of education (Bachelor’s degree or Master’s degree) has more or less been put on hold, and the focus is now on how to make teacher education more oriented towards the profession. The debate is taking place on many levels and in many contexts, and politicians, professionals, unions, universities and university colleges are contributing their own perspectives. A development group consisted of members from the University Colleges Denmark, The Danish Union of Teachers and their students’ organisation and KL - Local Government Denmark. This group has finished their work (The development group for teacher education, 2021 ). The development group for teacher education ( 2021 ) delivered its recommendations in November 2021, and the headlines are:

A more ambitious and professional demanding teacher education.

Extended and integrated internships and more exercise-based studies. The intention is to strengthen the coherence between the campus teaching and mentoring in the practice schools.

A renewed focus on so-called Bildung (‘dannelse’ or self-formation) in education and teacher education.

A teacher education with strong progression and coherence, which will ensure more professional teachers.

A reduction in the number of goals, and another way of formulating goals, so there will be more open frames to ensure local engagement and different profiles.

Since November 2021, The Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science has held meetings with the political parties about central themes, but when this is written (May 2022) negotiations have not started. Meanwhile, there are also political discussions about raising the funding of teacher education to increase student teachers’ time on task. There will be no new teacher education programme in 2022, but perhaps in 2023.

We are in the middle of a particularly important process: We have the chance to develop teacher education in various ways, and hopefully, we will be given the freedom, as professionals, to realise it in everyday practice. In our opinion, there is no contradiction between the academic and the profession-oriented content; on the contrary, the two areas must go hand in hand. With the last two reforms, we have seen the contours of an education that is finding its own professionalism and identity. Nonetheless, we have not yet reached the target. Several areas should be developed in the coming years, and there is a need to conduct research and develop a teacher education pedagogy that addresses the specific task of educating adults to teach children.

We are in the middle of a particularly important process: We have the chance to develop teacher education in various ways, and hopefully, we will be given the freedom, as professionals, to realise it in everyday practice. In our opinion, there is no contradiction between the academic and the profession-oriented content; on the contrary, the two areas must go hand in hand. With the last two reforms, we have seen the contours of an education that is finding its own professionalism and identity. Nonetheless, we have not yet reached the target. Several areas should be developed in the coming years, and there is a need to conduct research and develop a teacher education pedagogy that addresses the specific task of educating adults to teach children. Below, we list a few suggestions for four key areas that require further work.

Teaching and study methods in teacher education (on campus and in internships). Teaching and studying in teacher education are subject to the so-called double pedagogic gaze or second-order pedagogy (see, e.g., Goodwin & Kosnik, 2013 ), where students learn to teach others through teaching. Situated learning processes are of particular importance because of the immediate comparison between being taught as a student and being taught to teach. Thus, teaching in teacher education must be exemplary in the sense that teachers and students must be able to reflect, justify and often show in practice the connection between teaching aims, content and work methods. Therefore, a wide variety of work methods must be developed. Student teachers should not only become observant, reflective practitioners who can collect data and work empirically to develop their own practice (cf. the more research-oriented and academic competencies). Student teachers should also acquire and practise skills to deal with conflicts and facilitate diverse dialogues ranging from professional academic discussions in class to communication on pupils’ well-being at parent meetings (the more immediate practice and profession-oriented skills). University Colleges Denmark have formulated 10 ambitions for better teacher education. The tenth ambition focuses on ‘teacher education as a development laboratory’. (University Colleges Denmark, 2018 ).

Collaboration with practice schools. Many studies (e.g. Darling-Hammond & Baratz-Snowden, 2005 ) have shown that continuous collaboration and exchange between theoretical studies and a given professional practice offer considerable benefits. The 2013 reform has increased our focus on this aim, and we have made significant progress, but some aspects are still missing. We may need to further develop the internship model and ensure qualified internship counsellors to enhance both benefits and quality. Moreover, we need to develop a more diverse continuous collaboration with practice schools. This collaboration can be developed into short courses, such as teaching in a given grade for one or more days after careful preparation. The student teacher can later consider and process the teaching in collaboration with both the school teacher and the teacher educator. The collaboration with practice schools can also be developed into longer courses—for example, each student teacher can be assigned to a class during a year (e.g. for English) and provide feedback on the pupils’ written assignments, while the school teacher and the teacher educator can provide the student teacher with feedback on his/her feedback.

In Denmark, although internships in teacher education are also viewed as integrated, in most cases, they have taken place as long-term (e.g. six-week) courses only in practice schools. Therefore, integration primarily takes place in the preparation and post-processing phases in collaboration between campus and school. We believe that this is an important area for development to strengthen cooperation between schools and teacher education through the development of even better internship models and models for integrated practice and collaboration.

Students’ opportunities for in-depth studies in subject areas (both teaching subjects and basic pedagogical subjects), including strengthened collaboration regarding academic subjects, the pedagogical field and internships. In a highly specialised education with many subjects and modules, there is a need to develop models that enable students to immerse themselves in specific subject areas. It is also important to ensure collaboration regarding academic subjects, the pedagogical field and practice, since, for example, the integration of classroom management and inclusion strategies in academic subjects provides better opportunities for student teachers to apply it in practice (see, e.g., Hedegaard-Sørensen & Grumløse, 2016 ).

A renewed focus on so-called Bildung (‘dannelse’ or self-formation) in education and teacher education .

To increase enrolment in teacher education, continued effort is needed not only to enhance teacher status but also to develop clear career paths for teachers. Moreover, to retain qualified teachers, work must be done on transitional arrangements to ensure good jobs for new teachers (see, e.g., Lunde et al., 2017 ). Unfortunately, there are no formal requirements for teacher induction programmes in Denmark. The frequent reforms, along with the fact that the evaluations of the two most recent programmes did not identify alarming issues, indicate that the reforms must (also) be viewed in a broader context as expressions of general developments in society. From one point of view, the globalisation and international trends together with the need for European standards, call for development, while from the another point of view, there is a political need for immediate action.

Bjerril, S. (2022). Laveste kvote-2-tilslutning til læreruddannelsen siden 2014. [Lowest quota-2 applicants to teacher education since 2014]. Folkeskolen 15. March 2022.

Google Scholar

Danish Agency for Higher Education and Science. (2018). Kvalitet og relevans i læreruddannelsen. Ekspertgruppens evaluering og vurdering af læreruddannelsen af 2013 . [Quality and relevance in teacher education. The expert group's evaluation and assessment of the teacher education of 2013].

Darling-Hammond, L., & Baratz-Snowden, J. (2005). A good teacher in every classroom: Preparing the highly qualified teachers our children deserve . Jossey-Bass.

Goodwin, L., & Kosnik, C. (2013). Quality teacher educators = quality teachers? Conceptualizing essential domains of knowledge for those who teach teachers. Teacher Development, 17 (3), 334–346.

Article Google Scholar

Harryson, H. (2018). Den pædagogiske diskurs i Læreruddannelsen – formål, indhold og undervisningsmetoder [The pedagogical discourse in teacher education – purpose, content and teaching methods]. Aarhus Universitet, Phd-thesis.

Hedegaard-Sørensen, L., & Grumløse, S. P. (2016). Lærerfaglighed, inklusion og differentiering: Pædagogiske lektionsstudier i praksis [Teaching professionalism, inclusion and differentiation: Pedagogical lesson studies in practice]. Samfundslitteratur.

Lohse-Bossenz, H., Kunina-Habenicht, O., & Kunter, M. (2013). The role of educational psychology in teacher education: Expert opinions on what teachers should know about learning, development, and assessment. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28 (4), 1543–1565.

Lunde, L., Krøjgaard, F., Andersen, B. B., Mølgaard, D., & Rosholm, K. (2017). Lærerstart og fodfæste i et livslangt karriereforløb. [Teachers’ start and foothold in a lifelong career]. VIA University College.

Mejding, J. (1994). Den grimme ælling og svanerne? Om danske elevers læsefærdigheder [The ugly duckling and the swans? About Danish students' reading skills]. Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

Pedersen, D., Greve, C. & Højlund, H. (2008). Genopfindelsen af den offentlige sektor: Ledelsesudfordringer i reformernes tegn [The reinvention of the public sector: Management challenges in the spirit of reform]. Forlaget Børsen Offentlig.

Rasmussen, J., Bayer, M., & Brodersen, M. (2010). Komparativt studium af indholdet i læreruddannelserne i Canada, Danmark, Finland og Singapore: Rapport til regeringens rejsehold , [Comparative study of the content of teacher education in Canada, Denmark, Finland and Singapore: Report to the government's travel team]. Danish School of Education.

The Danish Evaluation Institute. (2011). Ny lærer. En evaluering af nyuddannede læreres møde med folkeskolen . [New teacher. An evaluation of newly qualified teachers’ meeting with the primary school]. https://www.eva.dk/sites/eva/files/2017-07/Ny%20l%C3%A6rer.pdf

The Danish Evaluation Institute. (2013). Frafald på læreruddannelsen . [Dropouts in teacher education] https://www.eva.dk/videregaaende-uddannelse/frafald-paa-laereruddannelsen-undersoegelse-aarsager-frafald

The Danish Evaluation Institute. (2017). Evaluering af effekten af optagelsessamtaler . [Evaluation of the effect of admissions interviews] https://www.eva.dk/sites/eva/files/2018-01/Effekten%20af%20optagelsessamtaler%20p%C3%A5%20l%C3%A6reruddannelsen_endelig.pdf

The Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science. (2019). Kommissorium for Kommission om fremtidens læreruddannelse [The Commissioner of the Commission on the Teacher Education of the Future] https://ufm.dk/.../kommissorium-for-kommission-om-fremtidens-laereruddannelse.pdf

The Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science. (2020). Udviklingsgruppens notater med uddybning af forslag til en nytænkt læreruddannelse [The development group’s notes with elaboration of proposals for a new teacher education]. https://ufm.dk/uddannelse/videregaende-uddannelse/professionshojskoler/professionsbacheloruddannelser/laereruddannelsen/faglige-anbefalinger-til-ny-laereruddannelse/udviklingsgruppens-notater.pdf

The development group for teacher education (2021). Løsningsforslag til en nytænkt læreruddannelse [Solution proposal for a new teacher education]. https://ufm.dk/uddannelse/videregaende-uddannelse/professionshojskoler/professionsbacheloruddannelser/laereruddannelsen/faglige-anbefalinger-til-ny-laereruddannelse/slides-fagligt-udviklingsarbejde-lu.pdf

University Colleges Denmark. (2018). Handleplan til en bedre læreruddannelse. 10 ambitioner . [Action plan for a better teacher education. 10 ambitions]. https://xn%2D%2Ddanskeprofessionshjskoler-xtc.dk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Handleplan-til-en-bedre-laereruddannelse-159772.pdf

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Teacher Education, Copenhagen University College, Copenhagen, Denmark

Faculty of Education, VIA University College, Aarhus, Denmark

Elsebeth Jensen

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Elsebeth Jensen .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Teacher Education and School Research, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Eyvind Elstad

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Madsen, L., Jensen, E. (2023). Teacher Education in Denmark. In: Elstad, E. (eds) Teacher Education in the Nordic Region. Evaluating Education: Normative Systems and Institutional Practices. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-26051-3_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-26051-3_7

Published : 14 March 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-26050-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-26051-3

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

News & Articles

Denmark: Agreement on a reform of the primary and lower secondary school teacher education programme

On 13 th September 2022, the Danish government and a broad majority of the Danish Parliament agreed on a new and better primary and lower secondary school teacher education programme. In 2020, the government had set up a committee whose recommendations on how to improve the teacher education programme now form the basis of the agreement.

The agreement comprises three objectives for the new teacher education programme:

- higher quality, enhanced professional standards, and an increased depth of studies;

- more teaching practice and an improved interaction between the teacher education programme and a teacher’s day-to-day life in the classroom;

- greater autonomy to implement the education programme at the local level, and less regulation from the national level.

To achieve higher quality, enhanced professional standards, and an increased depth of studies, the agreement includes the following initiatives, among others, for the benefit of student teachers:

- up to four more hours of instruction per week;

- more practice-based instruction, for example through training in classroom management, inclusion, home-school collaboration, etc.;

- more academic feedback and guidance, including via an annual status meeting that aims to give students individual feedback and guide them in relation to their professional development and motivation;

- more opportunities to complete part of one’s education abroad.

Initiatives to increase the amount of teaching practice and improve the interaction between the teacher education programme and a teacher’s day-to-day life in the classroom include:

- more extended time dedicated to teaching practice, so that students can acquire teaching experience in school settings during all four years of the education programme;

- more focus on practice in the final examination, which consists of a written examination and an oral examination;

- the reintroduction of Special Needs Education and Danish as a Second Language as core subjects in the teacher education programme.

Initiatives to ensure that the education programme is implemented with greater autonomy at the local level, and that there is less regulation from the national level, include the following actions:

- the many and detailed objectives presently listed in the course descriptions will be simplified and replaced with clearer objectives, so that each individual institution’s curricula and lecturers can enjoy greater autonomy;

- the current modules-based system will be replaced by one where students will all follow the same courses, in order to ensure professional progression, improved coherence, and stronger social integration.

The new primary and lower secondary school teacher education programme is scheduled to be launched in August 2023.

M ore information (in Danish)

Please consult the agreement at the following link: En ambitiøs læreruddannelse tæt på folkeskolen og til gavn for folkeskolen .

Source : Eurydice Unit Denmark

Latest News and Articles

The Research Institute of Child Psychology and Pathopsychology launched a national project entitled “Systemic Support of Mental Health and Prevention of Children, Pupils, and Students”

A new groundbreaking scheme was recently announced which provides free schoolbooks to Junior Cycle students in post-primary schools in the Free Education Scheme.

In February, the Portuguese government launched a programme for qualified young people, with the aim of benefiting recent graduates living in Portugal by providing them

To better prepare students for the demands of the modern workforce and to foster interest in STEM fields, Estonia has launched a strategic initiative focused

International Class in Teacher Education

If you are interested in acquiring relevant professional competences, studying new innovative teaching approaches in an international study environment and doing fieldwork in Danish Schools, then International Class in Teacher Education is perfect for you!

From 2025, this exchange programme will only be available in the spring semester.

1 semester (30 ECTS)

Campus city

Aarhus C

Study start

August and February

About the exchange programme International Class in Teacher Education

Structure and content, application deadlines:.

Spring semester: 1 November

Fall semester: 1 May

The programme is taught in English

The semester consists of one mandatory module, plus two modules chosen by you. You can take maximum three modules equivalent of 30 ECTS in total.

You will be studying in an international study environment at VIA University College at Campus Aarhus C. The Campus is new and located in the city centre of Aarhus.

The international students come from many different countries. Most come from Europe.

Teaching methods

Our teaching methods consist of different and varied work and study forms, such as lectures, dialogue-based communication, discussions, student presentations and group activities. The innovative teaching approaches are all process-based.

Collaboration between teachers and students is partly based on student initiative and independent work. We see active student participation and fieldwork as valuable and important components of studying a profession.

The practical perspective: Danish school culture

As an international student, you will study Danish school culture close up as a part of your semester. We consider the practical perspective of the teaching profession to be very important.

We will allocate you to a Danish primary or lower secondary school or a boarding school for a two week period.

The stay will give you the opportunity to see how Danish students learn in various learning environments. There will also be opportunities for you to visit classes with a focus on specific aspects of teaching.

More information

- We provide tutors and buddies for the international class, in order to welcome you and help you settle in your new study environment. Read more here .

- See a description of the modules

- Read about the aims and learning outcomes

- Good reasons for choosing this course

The minimum requirement to apply for the course is to have passed the first two semesters at bachelor’s level at your relevant university or another institute of higher education.

With regards to language proficiency, it is required to have an English level, spoken and written, equivalent to B2, according to the Common European Framework.

A maximum of 30 students will be admitted per semester.

Who can apply?

The programme is targeted towards students who are interested in becoming teachers in primary and lower secondary education.

- How to apply

Your home institution must have an inter-institutional agreement with VIA University College in order for you to be able to apply for an exchange programme at VIA.

If an agreement exists, you will be able to fill in the application form. Please be aware that VIA must receive a nomination from your home institution as well.

Go to the application portal to apply now

Fees and tuition

Exchange students do not pay tuition fees.

Per definition, exchange stays are an exchange of one or more students between partner universities and therefore, exchange students do not pay tuition fees.

If you do not know, if your institution is a partner of VIA, please contact the international office at your home institution. If your institution is not a partner of VIA and you would like us to discuss the possibility of establishing an exchange agreement with your home institution, please contact us at [email protected] .

Accommodation

If you are studying for a semester in The International Class in Teacher Education, you can rent a room in Aarhus for students.

Read about the accommodation in Aarhus for students studying at VIA.

Contact our Incoming team at [email protected] if you have questions about the exchange programme or how to apply.

Campus address

VIA University College Ceresbyen 24 DK - 8000 Aarhus C

Søren Iversen Hansen International Coordinator T: +45 87 55 31 37 E: [email protected]

Meet students

Julia and Melina study International Class and Teacher Education

Need to know more.

- Practical information for new exchange students

- Meet the students

Where to study?

- Campus Aarhus C

Ser via.dk underlig ud?

A long text

Teach in Denmark

There are a number of opportunities to teach English overseas in Denmark, particularly in the country’s numerous private language schools and international schools. Education is a huge priority in Danish society and the education system is held to a very high standard as a result, making Denmark a valuable opportunity for teachers looking to hone their skills and develop their teaching career abroad.

Top English teaching jobs in Denmark

Online Bilingual Tutor

Online elementary education tutor, online english tutor, teaching in denmark, options for teaching in denmark.

In Denmark, the public education system is strictly regulated. Teachers with non-Danish teaching credentials looking for teaching jobs in the primary and secondary school systems will need to first apply to the Danish Agency for Higher Education and request that their international qualifications be formally recognized. If necessary, expat teachers may be required to undergo further training.

Alternatively, Denmark offers a number of English teaching job opportunities for expat teachers outside of the mainstream public school system, either in bilingual international schools or private language schools. These schools are, for the most part, concentrated in the main urban cities Denmark like Copenhagen, Fredericia, Glostrup, and Hellerup.

Language schools

There are a large number of English language schools in Denmark offering opportunities for qualified teachers to teach subjects like Advanced English and Business English. Business English teaching jobs are in huge demand and previous business experience is often considered an advantage for these positions, along with relevant qualifications and previous experience teaching.

International schools

Denmark has more than 24 international schools across the country, primarily for children of expats, that regularly employ native English-speaking teaching staff. In Danish international schools, teachers are often in high demand and, consequently, the requirements for teachers looking for jobs at these schools are often more advanced.

Salary and benefits while teaching in Denmark

Salary and benefits for teaching jobs in international schools and language schools in Denmark vary greatly across schools. Having, at minimum, a Bachelor’s degree as well as a relevant English teaching qualification such as a TEFL certificate offers teachers the best chance to maximize their salary and benefit packages.

Teaching in Denmark – Hiring

Qualifications to teach in denmark.

Visas for teachers in Denmark

Living in denmark.

Things for teachers to do in Denmark

Register for a teacher account to apply for teaching jobs in Denmark.

Denmark at a glance

Country information.

Capital: Copenhagen

Language: Danish

Population: 5.614 million

Currency: Danish krone

Government: Constitutional monarchy

Major religion: Evangelical Lutheran

Climate: Temperate

Quick facts

Copenhagen is home to more Michelin-starred restaurants than the rest of Scandinavia combined.

Want to teach English in Denmark?

Start your journey with a TEFL Certification.

Apply to teach in Denmark

Teaching jobs in Denmark open regularly, with start dates throughout the year.

Want to become a licensed teacher?

Earn a US teaching license with our Teacher Certification Program (TCP).

Popular Destinations

Countries Nearby

Related Articles

Useful Links

Teachers with non-Danish qualifications

The following teaching professions are regulated by law in Denmark:

- Teacher in municipal primary and lower secondary school

- Teacher in general upper secondary education

- Pedagogue in municipal primary school (preschool class to grade 3 educator)

- Teacher of Danish for adult foreigners

That means that you must have your non-Danish qualifications recognised in order to apply for a permanent position. You apply to the Danish Agency for Higher Education and Science, which is an authority under the Ministry of Higher Education and Science.

On the following pages, you can read more about the requirements for having your teaching qualifications recognised or about other types of teaching jobs that are not regulated:

- Primary and Lower Secondary School Teacher

- Upper Secondary School Teacher

- Pedagogue in Primary School, i.e. preschool class to grade 3 educator