- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

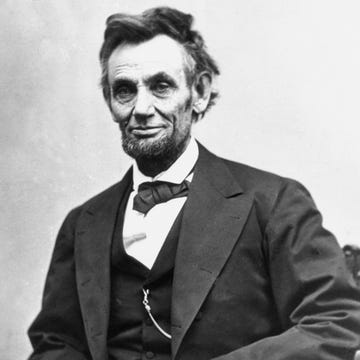

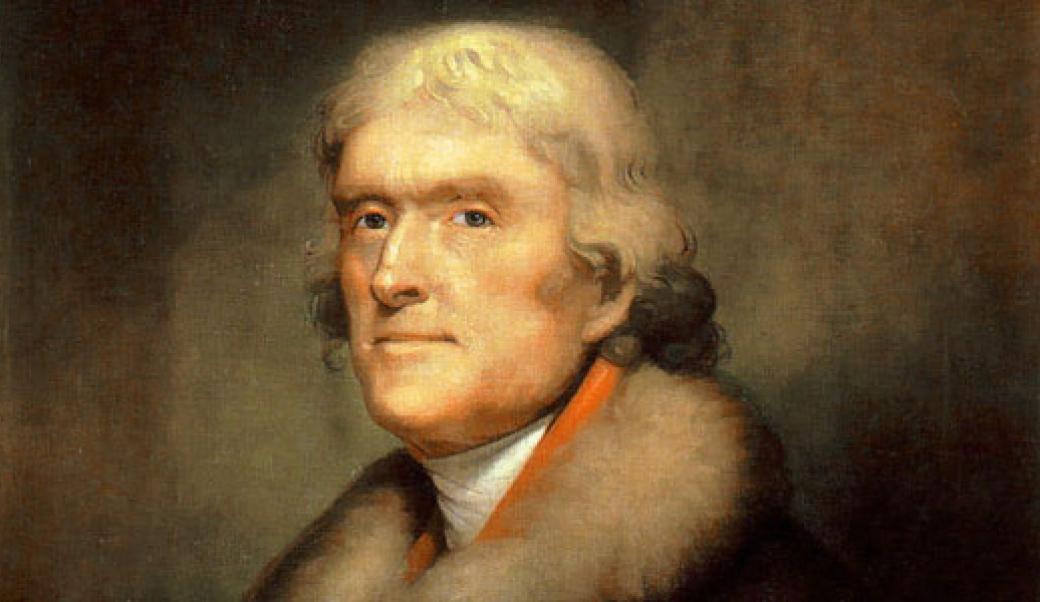

Thomas Jefferson

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 22, 2022 | Original: October 29, 2009

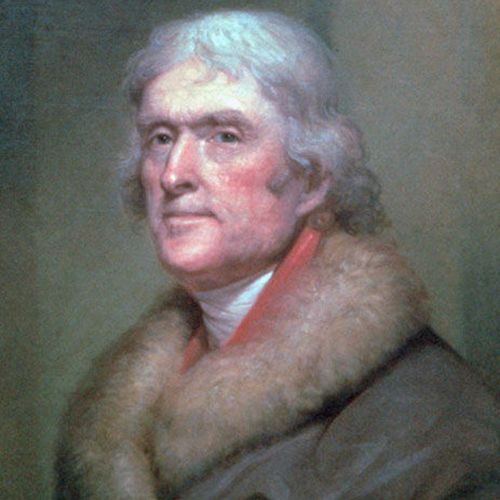

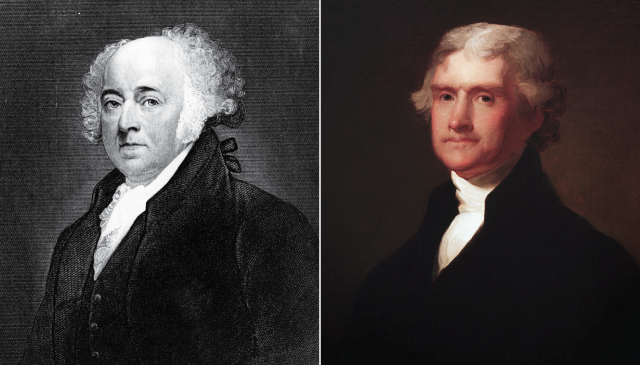

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), author of the Declaration of Independence and the third U.S. president, was a leading figure in America’s early development. During the American Revolutionary War (1775-83), Jefferson served in the Virginia legislature and the Continental Congress and was governor of Virginia. He later served as U.S. minister to France and U.S. secretary of state and was vice president under John Adams (1735-1826).

Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican who thought the national government should have a limited role in citizens’ lives, was elected president in 1800. During his two terms in office (1801-1809), the U.S. purchased the Louisiana Territory and Lewis and Clark explored the vast new acquisition. Although Jefferson promoted individual liberty, he also enslaved over six hundred people throughout his life. After leaving office, he retired to his Virginia plantation, Monticello, and helped found the University of Virginia.

Thomas Jefferson’s Early Years

Thomas Jefferson was born on April 13, 1743, at Shadwell, a plantation on a large tract of land near present-day Charlottesville, Virginia . His father, Peter Jefferson (1707/08-57), was a successful planter and surveyor and his mother, Jane Randolph Jefferson (1720-76), came from a prominent Virginia family. Thomas was their third child and eldest son; he had six sisters and one surviving brother.

Did you know? In 1815, Jefferson sold his 6,700-volume personal library to Congress for $23,950 to replace books lost when the British burned the U.S. Capitol, which housed the Library of Congress, during the War of 1812. Jefferson's books formed the foundation of the rebuilt Library of Congress's collections.

In 1762, Jefferson graduated from the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, where he reportedly enjoyed studying for 15 hours, then practicing violin for several more hours on a daily basis. He went on to study law under the tutelage of respected Virginia attorney George Wythe (there were no official law schools in America at the time, and Wythe’s other pupils included future Chief Justice John Marshall and statesman Henry Clay ).

Jefferson began working as a lawyer in 1767. As a member of colonial Virginia’s House of Burgesses from 1769 to 1775, Jefferson, who was known for his reserved manner, gained recognition for penning a pamphlet, “A Summary View of the Rights of British America” (1774), which declared that the British Parliament had no right to exercise authority over the American colonies .

Marriage and Monticello

After his father died when Jefferson was a teen, the future president inherited the Shadwell property. In 1768, Jefferson began clearing a mountaintop on the land in preparation for the elegant brick mansion he would construct there called Monticello (“little mountain” in Italian). Jefferson, who had a keen interest in architecture and gardening, designed the home and its elaborate gardens himself.

Over the course of his life, he remodeled and expanded Monticello and filled it with art, fine furnishings and interesting gadgets and architectural details. He kept records of everything that happened at the 5,000-acre plantation, including daily weather reports, a gardening journal and notes about his slaves and animals.

On January 1, 1772, Jefferson married Martha Wayles Skelton (1748-82), a young widow. The couple moved to Monticello and eventually had six children; only two of their daughters—Martha (1772-1836) and Mary (1778-1804)—survived into adulthood. In 1782, Jefferson’s wife Martha died at age 33 following complications from childbirth. Jefferson was distraught and never remarried. However, it is believed he fathered more children with one of his enslaved women, Sally Hemings (1773-1835), who was also his wife’s half-sister .

Slavery was a contradictory issue in Jefferson’s life. Although he was an advocate for individual liberty and at one point promoted a plan for the gradual emancipation of slaves in America, he enslaved people throughout his life. Additionally, while he wrote in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal,” he believed African Americans were biologically inferior to whites and thought the two races could not coexist peacefully in freedom. Jefferson inherited some 175 enslaved people from his father and father-in-law and owned an estimated 600 slaves over the course of his life. He freed only a small number of them in his will; the majority were sold following his death.

Thomas Jefferson and the American Revolution

In 1775, with the American Revolutionary War recently underway, Jefferson was selected as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. Although not known as a great public speaker, he was a gifted writer and at age 33, was asked to draft the Declaration of Independence (before he began writing, Jefferson discussed the document’s contents with a five-member drafting committee that included John Adams and Benjamin Franklin ). The Declaration of Independence , which explained why the 13 colonies wanted to be free of British rule and also detailed the importance of individual rights and freedoms, was adopted on July 4, 1776.

In the fall of 1776, Jefferson resigned from the Continental Congress and was re-elected to the Virginia House of Delegates (formerly the House of Burgesses). He considered the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which he authored in the late 1770s and which Virginia lawmakers eventually passed in 1786, to be one of the significant achievements of his career. It was a forerunner to the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution , which protects people’s right to worship as they choose.

From 1779 to 1781, Jefferson served as governor of Virginia, and from 1783 to 1784, did a second stint in Congress (then officially known, since 1781, as the Congress of the Confederation). In 1785, he succeeded Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) as U.S. minister to France. Jefferson’s duties in Europe meant he could not attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787; however, he was kept informed of the proceedings to draft a new national constitution and later advocated for including a bill of rights and presidential term limits.

Jefferson's Path to the Presidency

After returning to America in the fall of 1789, Jefferson accepted an appointment from President George Washington (1732-99) to become the new nation’s first secretary of state. In this post, Jefferson clashed with U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton (1755/57-1804) over foreign policy and their differing interpretations of the U.S. Constitution. In the early 1790s, Jefferson, who favored strong state and local government, co-founded the Democratic-Republican Party to oppose Hamilton’s Federalist Party , which advocated for a strong national government with broad powers over the economy.

In the presidential election of 1796, Jefferson ran against John Adams and received the second-highest amount of votes, which, according to the law at the time, made him vice president.

Jefferson ran against Adams again in the presidential election of 1800, which turned into a bitter battle between the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. Jefferson defeated Adams; however, due to a flaw in the electoral system, Jefferson tied with fellow Democratic-Republican Aaron Burr (1756-1836). The House of Representatives broke the tie and voted Jefferson into office. In order to avoid a repeat of this situation, Congress proposed the Twelfth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which required separate voting for president and vice president. The amendment was ratified in 1804.

Jefferson Becomes Third U.S. President

Jefferson was sworn into office on March 4, 1801; he was the first presidential inauguration held in Washington, D.C. ( George Washington was inaugurated in New York in 1789; in 1793, he was sworn into office in Philadelphia, as was his successor, John Adams, in 1797.) Instead of riding in a horse-drawn carriage, Jefferson broke with tradition and walked to and from the ceremony.

One of the most significant achievements of Jefferson’s first administration was the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France for $15 million in 1803. At more than 820,000 square miles, the Louisiana Purchase (which included lands extending between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains and the Gulf of Mexico to present-day Canada) effectively doubled the size of the United States. Jefferson then commissioned explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to explore the uncharted land, plus the area beyond, out to the Pacific Ocean. (At the time, most Americans lived within 50 miles of the Atlantic Ocean.) Lewis and Clark’s expedition , known today as the Corps of Discovery, lasted from 1804 to 1806 and provided valuable information about the geography, American Indian tribes and animal and plant life of the western part of the continent.

In 1804, Jefferson ran for re-election and defeated Federalist candidate Charles Pinckney (1746-1825) of South Carolina with more than 70 percent of the popular vote and an electoral count of 162-14. During his second term, Jefferson focused on trying to keep America out of Europe’s Napoleonic Wars (1803-15). However, after Great Britain and France, who were at war, both began harassing American merchant ships, Jefferson implemented the Embargo Act of 1807.

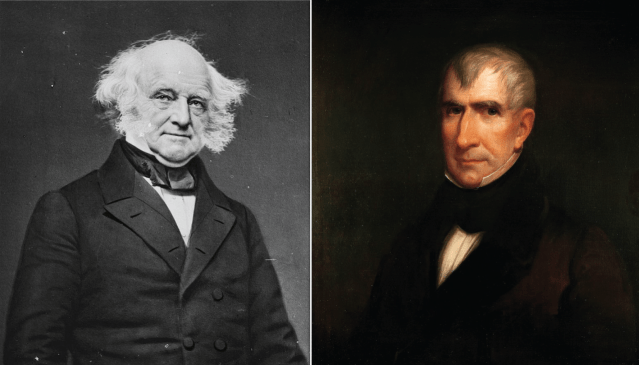

The act, which closed U.S. ports to foreign trade, proved unpopular with Americans and hurt the U.S. economy. It was repealed in 1809 and, despite the president’s attempts to maintain neutrality, the U.S. ended up going to war against Britain in the War of 1812. Jefferson chose not to run for a third term in 1808 and was succeeded in office by James Madison (1751-1836), a fellow Virginian and former U.S. secretary of state.

Thomas Jefferson’s Later Years and Death

Jefferson spent his post-presidential years at Monticello, where he continued to pursue his many interests, including architecture, music, reading and gardening. He also helped found the University of Virginia, which held its first classes in 1825. Jefferson was involved with designing the school’s buildings and curriculum and ensured that unlike other American colleges at the time, the school had no religious affiliation or religious requirements for its students.

Jefferson died at age 83 at Monticello on July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. Coincidentally, John Adams, Jefferson’s friend, former rival and fellow signer of the Declaration of Independence, died the same day . Jefferson was buried at Monticello. However, due to the significant debt the former president had accumulated during his life, his mansion, furnishing and enslaved people were sold at auction following his death. Monticello was eventually acquired by a nonprofit organization, which opened it to the public in 1954.

Jefferson remains an American icon. His face appears on the U.S. nickel and is carved into stone at Mount Rushmore . The Jefferson Memorial, near the National Mall in Washington, D.C., was dedicated on April 13, 1943, the 200th anniversary of Jefferson’s birth.

HISTORY Vault: U.S. Presidents

Stream U.S. Presidents documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

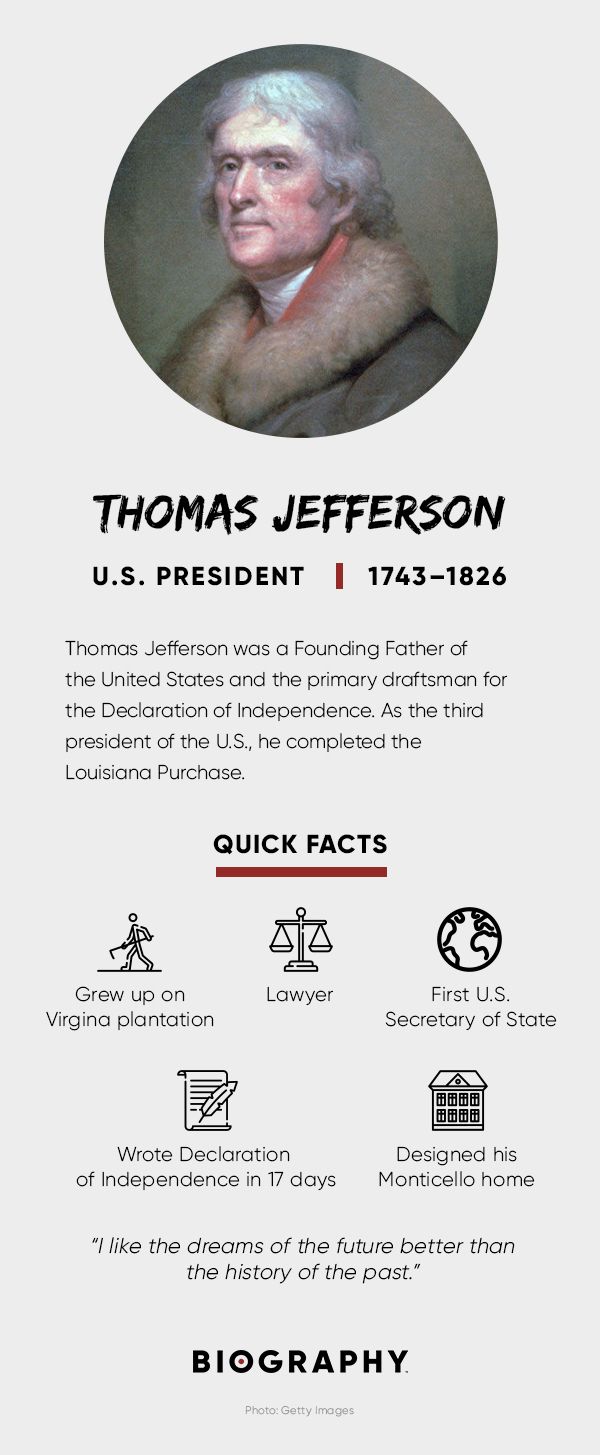

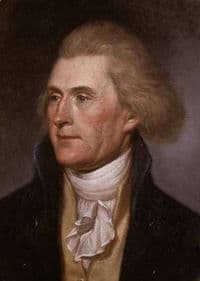

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was a Founding Father of the United States who wrote the Declaration of Independence. As U.S. president, he completed the Louisiana Purchase.

(1743-1826)

Who Was Thomas Jefferson?

Jefferson was born on April 13, 1743, at the Shadwell plantation located just outside of Charlottesville, Virginia. Jefferson was born into one of the most prominent families of Virginia's planter elite. His mother, Jane Randolph Jefferson, was a member of the proud Randolph clan, a family claiming descent from English and Scottish royalty.

His father, Peter Jefferson, was a successful farmer as well as a skilled surveyor and cartographer who produced the first accurate map of the Province of Virginia. The young Jefferson was the third born of 10 siblings.

As a boy, Jefferson's favorite pastimes were playing in the woods, practicing the violin and reading. He began his formal education at the age of nine, studying Latin and Greek at a local private school run by the Reverend William Douglas.

In 1757, at the age of 14, he took up further study of the classical languages as well as literature and mathematics with the Reverend James Maury, whom Jefferson later described as "a correct classical scholar."

- College of William and Mary

In 1760, having learned all he could from Maury, Jefferson left home to attend the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia's capital.

Although it was the second oldest college in America (after Harvard ), William and Mary was not at that time an especially rigorous academic institution. Jefferson was dismayed to discover that his classmates expended their energies betting on horse races, playing cards and courting women rather than studying.

Nevertheless, the serious and precocious Jefferson fell in with a circle of older scholars that included Professor William Small, Lieutenant Governor Francis Fauquier and lawyer George Wythe, and it was from them that he received his true education.

Becoming a Lawyer

After three years at William and Mary, Jefferson decided to read law under Wythe, one of the preeminent lawyers of the American colonies. There were no law schools at this time; instead aspiring attorneys "read law" under the supervision of an established lawyer before being examined by the bar.

Wythe guided Jefferson through an extraordinarily rigorous five-year course of study (more than double the typical duration); by the time Jefferson won admission to the Virginia bar in 1767, he was already one of the most learned lawyers in America.

In 1770, Jefferson began construction of what was perhaps his greatest labor of love: Monticello , his house atop a small rise in the Piedmont region of Virginia. The house was built on land his father had owned since 1735.

In keeping with the interests of one of America's greatest "Renaissance Men" — Jefferson's interests ranged from botany and archaeology to music and birdwatching — Jefferson himself drafted the blueprints for Monticello’s neoclassical mansion, outbuildings and gardens.

More than just a residence, Monticello was also a working plantation, where Jefferson kept roughly 130 African Americans in slavery. Their duties included tending gardens and livestock, plowing fields and working at the on-site textile factory.

Thomas Jefferson's Children

From 1767 to 1774, Jefferson practiced law in Virginia with great success, trying many cases and winning most of them. During these years, he also met and fell in love with Martha Wayles Skelton, a recent widow and one of the wealthiest women in Virginia.

The pair married on January 1, 1772. Thomas and Martha Jefferson had six children together, but only two survived into adulthood: Martha, their firstborn, and Mary, their fourth. Only Martha survived her father.

His six children with Martha, however, were not the only children Jefferson fathered.

Sally Hemings

History scholars and a significant body of DNA evidence indicate that Jefferson had an affair – and at least one child – with one of his enslaved people, a woman named Sally Hemings, who was in fact Martha Jefferson's half-sister.

Sally's mother, Betty Hemings, was an enslaved owned by Jefferson's father-in-law, John Wayles, who was the father of Betty's daughter Sally. It is overwhelmingly likely, if not absolutely certain, that Jefferson fathered all six of Sally Hemings' children.

Most compelling is DNA evidence showing that some male member of the Jefferson family fathered Hemings' children, and that it was not Samuel or Peter Carr, the only two of Jefferson's male relatives in the vicinity at the relevant times.

Political Career

The beginning of Jefferson's professional life coincided with great changes in Great Britain's 13 colonies in America.

The conclusion of the French and Indian War in 1763 left Great Britain in dire financial straits; to raise revenue, the Crown levied a host of new taxes on its American colonies. In particular, the Stamp Act of 1765, imposing a tax on printed and paper goods, outraged the colonists, giving rise to the American revolutionary slogan, "No taxation without representation."

Eight years later, on December 16, 1773, colonists protesting a British tea tax dumped 342 chests of tea into the Boston Harbor in what is known as the Boston Tea Party . In April 1775, American militiamen clashed with British soldiers at the Battles of Lexington and Concord , the first battles in what developed into the Revolutionary War .

Jefferson was one of the earliest and most fervent supporters of the cause of American independence from Great Britain. He was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1768 and joined its radical bloc, led by Patrick Henry and George Washington .

In 1774, Jefferson penned his first major political work, A Summary View of the Rights of British America , which established his reputation as one of the most eloquent advocates of the American cause.

A year later, in 1775, Jefferson attended the Second Continental Congress , which created the Continental Army and appointed Jefferson's fellow Virginian, George Washington, as its commander-in-chief. However, the Congress' most significant work fell to Jefferson himself.

Declaration of Independence

In June 1776, the Congress appointed a five-man committee (Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin , Roger Sherman and Robert Livingston) to draft a Declaration of Independence .

The committee then chose Jefferson to author the declaration's first draft, selecting him for what Adams called his "happy talent for composition and singular felicity of expression." Over the next 17 days, Jefferson drafted one of the most beautiful and powerful testaments to liberty and equality in world history.

The document opened with a preamble stating the natural rights of all human beings and then continued on to enumerate specific grievances against King George III that absolved the American colonies of any allegiance to the British Crown.

Although the version of the Declaration of Independence adopted on July 4, 1776, had undergone a series of revisions from Jefferson's original draft, its immortal words remain essentially his own: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights; that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness."

After authoring the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson returned to Virginia, where, from 1776 to 1779, he served as a member of the Virginia House of Delegates. There he sought to revise Virginia's laws to fit the American ideals he had outlined in the Declaration of Independence.

Jefferson successfully abolished the doctrine of entail, which dictated that only a property owner's heirs could inherit his land, and the doctrine of primogeniture, which required that in the absence of a will a property owner's oldest son inherited his entire estate.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S THOMAS JEFFERSON FACT CARD

Separation of Church and State

In 1777, Jefferson wrote the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which established freedom of religion and the separation of church and state.

Although the document was not adopted as Virginia state law for another nine years, it was one of Jefferson's proudest life accomplishments.

Governor of Virginia

On June 1, 1779, the Virginia legislature elected Jefferson as the state's second governor. His two years as governor proved the low point of Jefferson's political career. Torn between the Continental Army's desperate pleas for more men and supplies and Virginians' strong desire to keep such resources for their own defense, Jefferson waffled and pleased no one.

As the Revolutionary War progressed into the South, Jefferson moved the capital from Williamsburg to Richmond, only to be forced to evacuate that city when it, rather than Williamsburg, turned out to be the target of British attack.

On June 1, 1781, the day before the end of his second term as governor, Jefferson was forced to flee his home at Monticello (located near Charlottesville, Virginia), only narrowly escaping capture by the British cavalry. Although he had no choice but to flee, his political enemies later pointed to this inglorious incident as evidence of cowardice.

Jefferson declined to seek a third term as governor and stepped down on June 4, 1781. Claiming that he was giving up public life for good, he returned to Monticello, where he intended to live out the rest of his days as a gentleman farmer surrounded by the domestic pleasures of his family, his farm and his books.

Notes on the State of Virginia

To fill his time at home, in late 1781, Jefferson began working on his only full-length book, the modestly titled Notes on the State of Virginia .

While the book's ostensible purpose was to outline the history, culture and geography of Virginia, it also provides a window into Jefferson's political philosophy and worldview.

Contained in Notes on the State of Virginia is Jefferson's vision of the good society he hoped America would become: a virtuous agricultural republic, based on the values of liberty, honesty and simplicity and centered on the self-sufficient yeoman farmer.

Jefferson's Enslaved People

Jefferson's writings also shed light on his contradictory, controversial and much-debated views on race and slavery . Jefferson owned enslaved people through his entire life, and his very existence as a gentleman farmer depended on the institution of slavery.

Like most white Americans of that time, Jefferson held views we would now describe as nakedly racist: He believed that Black people were innately inferior to white people in terms of both mental and physical capacity.

Nevertheless, he claimed to abhor slavery as a violation of the natural rights of man. He saw the eventual solution of America's race problem as the abolition of slavery followed by the exile of formerly enslaved people to either Africa or Haiti, because, he believed, formerly enslaved could not live peacefully alongside their former masters.

As Jefferson wrote, "We have the wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other."

Minister to France

Jefferson was spurred back into public life by private tragedy: the untimely death of his beloved wife, Martha, on September 6, 1782, at the age of 34.

After months of mourning, in June 1783, Jefferson returned to Philadelphia to lead the Virginia delegation to the Confederation Congress. In 1785, that body appointed Jefferson to replace Benjamin Franklin as U.S. minister to France.

Although Jefferson appreciated much about European culture — its arts, architecture, literature, food and wines — he found the juxtaposition of the aristocracy's grandeur and the masses' poverty repellant. "I find the general fate of humanity here, most deplorable," he wrote in one letter.

In Europe, Jefferson rekindled his friendship with John Adams, who served as minister to Great Britain, and Adams' wife, Abigail Adams . The educated and erudite Abigail, with whom Jefferson maintained a lengthy correspondence on a wide variety of subjects, was perhaps the only woman he ever treated as an intellectual equal.

Jefferson's official duties as minister consisted primarily of negotiating loans and trade agreements with private citizens and government officials in Paris and Amsterdam.

After nearly five years in Paris, Jefferson returned to America at the end of 1789 with a much greater appreciation for his home country. As he wrote to his good friend, James Monroe , "My God! How little do my countrymen know what precious blessings they are in possession of, and which no other people on earth enjoy."

Secretary of State

Jefferson arrived in Virginia in November 1789 to find George Washington waiting for him with news that Washington had been elected the first president of the United States of America, and that he was appointing Jefferson as his secretary of state.

Besides Jefferson, Washington's most trusted advisor was Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton . A dozen years younger than Jefferson, Hamilton was a New Yorker and war hero who, unlike Jefferson and Washington, had risen from humble beginnings.

Jefferson's Political Party

Rancorous partisan battles emerged to divide the new American government during Washington's presidency.

On one side, the Federalists , led by Hamilton, advocated for a strong national government, broad interpretation of the U.S. Constitution and neutrality in European affairs.

On the other side, the Republican political party, led by Jefferson, promoted the supremacy of state governments, a strict constructionist interpretation of the Constitution and support for the French Revolution .

Washington's two most trusted advisors thus provided nearly opposite advice on the most pressing issues of the day: the creation of a national bank, the appointment of federal judges and the official posture toward France.

On January 5, 1794, frustrated by the endless conflicts, Jefferson resigned as secretary of state, once again abandoning politics in favor of his family and farm at his beloved Monticello.

Jefferson as Vice President

In 1797, despite Jefferson's public ambivalence and previous claims that he was through with politics, the Republicans selected Jefferson as their candidate to succeed George Washington as president.

In those days, candidates did not campaign for office openly, so Jefferson did little more than remain at home on the way to finishing a close second to then-Vice President John Adams in the electoral college , which, by the rules of the time, made Jefferson the new vice president.

Besides presiding over the U.S. Senate , the vice president had essentially no substantive role in government. The long friendship between Adams and Jefferson had cooled due to political differences (Adams was a Federalist), and Adams did not consult his vice president on any important decisions.

To occupy his time during his four years as vice president, Jefferson authored A Manual of Parliamentary Practice , one of the most useful guides to legislative proceedings ever written, and served as the president of the American Philosophical Society .

John Adams' presidency revealed deep fissures in the Federalist Party between moderates such as Adams and Washington and more extreme Federalists like Alexander Hamilton.

In the presidential election of 1800, the Federalists refused to back Adams, clearing the way for the Republican candidates Jefferson and Aaron Burr to tie for first place with 73 electoral votes each. After a long and contentious debate, the House of Representatives selected Jefferson to serve as the third U.S. president, with Burr as his vice president.

The election of Jefferson in 1800 was a landmark of world history, the first peacetime transfer of power from one party to another in a modern republic.

Delivering his inaugural address on March 4, 1801, Jefferson spoke to the fundamental commonalities uniting all Americans despite their partisan differences. "Every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle," he stated. "We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists."

Accomplishments

President Jefferson's accomplishments during his first term in office were numerous, remarkably successful and productive.

In keeping with his Republican values, Jefferson stripped the presidency of all the trappings of European royalty, reduced the size of the armed forces and government bureaucracy and lowered the national debt from $80 million to $57 million in his first two years in office.

Nevertheless, Jefferson's most important achievements as president all involved bold assertions of national government power and surprisingly liberal readings of the U.S. Constitution.

Louisiana Purchase

Jefferson's most significant accomplishment as president was the Louisiana Purchase. In 1803, he acquired land stretching from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains from cash-strapped Napoleonic France for the bargain price of $15 million, thereby doubling the size of the nation in a single stroke.

He then devised the wonderfully informative Lewis and Clark Expedition to explore, map out and report back on the new American territories.

Tripoli Pirates

Jefferson also put an end to the centuries-old problem of Tripoli pirates from North Africa disrupting American shipping in the Mediterranean. During the Barbary War, Jefferson forced the pirates to capitulate by deploying new American warships.

Notably, both the Louisiana Purchase and the undeclared war against the Barbary pirates conflicted with Jefferson's much-avowed Republican values. Both actions represented unprecedented expansions of national government power, and neither was explicitly sanctioned by the Constitution.

Second Term as President

Although Jefferson easily won re-election in 1804, his second term in office proved much more difficult and less productive than his first. He largely failed in his efforts to impeach the many Federalist judges swept into government by the Judiciary Act of 1801.

However, the greatest challenges of Jefferson's second term were posed by the war between Napoleonic France and Great Britain. Both Britain and France attempted to prevent American commerce with the other power by harassing American shipping, and Britain in particular sought to impress American sailors into the British Navy.

In response, Jefferson passed the Embargo Act of 1807, suspending all trade with Europe. The move wrecked the American economy as exports crashed from $108 million to $22 million by the time he left office in 1809. The embargo also led to the War of 1812 with Great Britain after Jefferson left office.

Post Presidency

On March 4, 1809, after watching the inauguration of his close friend and successor James Madison , Jefferson returned to Virginia to live out the rest of his days as "The Sage of Monticello."

Jefferson's primary pastime was endlessly rebuilding, remodeling and improving his home and estate, at considerable expense.

A Frenchman, Marquis de Chastellux, quipped, "it may be said that Mr. Jefferson is the first American who has consulted the Fine Arts to know how he should shelter himself from the weather."

University of Virginia

Jefferson also dedicated his later years to organizing the University of Virginia , the nation's first secular university. He personally designed the campus, envisioned as an "academical village," and hand-selected renowned European scholars to serve as its professors.

The University of Virginia opened its doors on March 7, 1825, one of the proudest days of Jefferson's life.

Jefferson also kept up an outpouring of correspondence at the end of his life. In particular, he rekindled a lively correspondence on politics, philosophy and literature with John Adams that stands out among the most extraordinary exchanges of letters in history.

Nevertheless, Jefferson's retirement was marred by financial woes. To pay off the substantial debts he incurred over decades of living beyond his means, Jefferson resorted to selling his cherished personal library to the national government to serve as the foundation of the Library of Congress .

Jefferson died on July 4, 1826 — the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence — only a few hours before John Adams passed away in Massachusetts.

In the moments before he passed, Adams spoke his last words, eternally true if not in the literal sense in which he meant them, "Thomas Jefferson survives."

As the author of the Declaration of Independence, the foundational text of American democracy and one of the most important documents in world history, Jefferson will be forever revered as one of the great American Founding Fathers. However, Jefferson was also a man of many contradictions.

Jefferson was the spokesman of liberty and a racist enslaved people owner, a champion of the common people and a man with luxurious and aristocratic tastes, a believer in limited government and a president who expanded governmental authority beyond the wildest visions of his predecessors, a quiet man who abhorred politics and arguably the most dominant political figure of his generation.

The tensions between Jefferson's principles and practices make him all the more apt a symbol for the nation he helped create, a nation whose shining ideals have always been complicated by a complex history.

Jefferson is buried in the family cemetery at his beloved Monticello, in a grave marked by a plain gray tombstone. The brief inscription it bears, written by Jefferson himself, is as noteworthy for what it excludes as what it includes.

The inscription suggests Jefferson's humility as well as his belief that his greatest gifts to posterity came in the realm of ideas rather than the realm of politics: "Here was buried Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of American Independence of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, and father of the University Of Virginia."

Sally Hemmings

"],["

George Washington

James Monroe

James Madison

Benjamin Franklin

"]]" tml-render-layout="inline">

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Thomas Jefferson

- Birth Year: 1743

- Birth date: April 13, 1743

- Birth State: Virginia

- Birth City: Shadwell

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Thomas Jefferson was a Founding Father of the United States who wrote the Declaration of Independence. As U.S. president, he completed the Louisiana Purchase.

- U.S. Politics

- Astrological Sign: Aries

- Death Year: 1826

- Death date: July 4, 1826

- Death State: Virginia

- Death City: Monticello (near Charlottesville)

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Thomas Jefferson Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/political-figures/thomas-jefferson

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: January 25, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- We have the wolf by the ears, and we can neither hold him nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.

- All tyranny needs to gain a foothold is for people of good conscience to remain silent.

- ...How little do my countrymen know what precious blessings they are in possession of, and which no other people on earth enjoy.

- Every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle. We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.

- The natural progress of things is for liberty to yield and government to gain ground.

- I hold it that a little rebellion now and then is a good thing, and as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical.

- I find friendship to be like wine, raw when new, ripened with age, the true old man's milk and restorative cordial.

- I cannot live without books; but fewer will suffice where amusement, and not use, is the only future object.

- The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.

- All, too, will bear in mind this sacred principle, that though the will of the majority is in all cases to prevail, that will to be rightful must be reasonable; that the minority possess their equal rights, which equal law must protect, and to violate would be oppression.

- I like the dreams of the future better than the history of the past.

- [A] wise and frugal government, which shall restrain men from injuring one another, shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, and shall not take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned.

- I know well that no man will ever bring out of that office the reputation which carries him into it.

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

U.S. Presidents

Oppenheimer and Truman Met Once. It Went Badly.

Who Killed JFK? You Won’t Believe Us Anyway

John F. Kennedy

Jimmy Carter

Inside Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter’s 77-Year Love

Abraham Lincoln

Who Is Walt Nauta, the Man Indicted with Trump?

Hunter Biden and Other Presidential Problem Kids

Controversial Judge Aileen Cannon Not Out Just Yet

Barack Obama

10 Celebrities the Same Age as President Joe Biden

Biography Online

Biography Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743–July 4, 1826) was a leading Founding Father of the United States, the author of the Declaration of Independence (1776) and he served as the third President of the US (1801–1809). Jefferson was a committed Republican – arguing passionately for liberty, democracy and devolved power. Jefferson also wrote the Statute for Religious Freedom in 1777 – it was adopted by the state of Virginia in 1786. Jefferson was also a noted polymath with wide-ranging interests from architecture to gardening, philosophy, literature and education. Although a slave owner himself, Jefferson sought to introduce a bill (1800) to end slavery in all Western territories. As President, he signed a bill to ban the importation of slaves into the US (1807).

Jefferson’s Childhood

“Still less let it be proposed that our properties within our own territories shall be taxed or regulated by any power on earth but our own. The God who gave us life gave us liberty at the same time; the hand of force may destroy, but cannot disjoin them. This, sire, is our last, our determined resolution;”

Thomas Jefferson – A Summary View of the Rights of British America (1774). ( Wikisource )

Thomas Jefferson and The Declaration of Independence (1776)

Thomas Jefferson was the primary author in drafting the American Declaration of Independence. The act was adopted on July 4th, 1776 and was a symbolic statement of the aims of the American Revolution.

“We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness…”

– Thomas Jefferson, Declaration of Independence , July 4th, 1776. Jefferson received suggestions from others such as James Madison. He was also influenced by the writings of the British Empiricists, in particular, John Locke and Thomas Paine . The importance of the Declaration of Independence was summed up in The Gettysburg address of Abraham Lincoln in 1863.

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

However, Jefferson was disappointed that a reference to the evil of slavery was removed at the request of delegates from the South. From 1785 to 1789 Jefferson served as minister to France, succeeding Benjamin Franklin . In France, Jefferson became immersed in Paris society. He was a noted host and came into contact with many of the great thinkers of the age. Jefferson also saw the social and political turmoil which resulted in the French Revolution. On 26 August 1789, the French Assembly published the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen , which was directly influenced by Jefferson’s US Declaration of Independence. On his return to America Jefferson served under George Washington as first Secretary of State. Here he began debating with the Hamilton factions over the size of government spending. Jefferson was an advocate of minimal government. At the end of his term 1783, he retired temporarily to Monticello, where he spent time amongst his gardens and with his family.

Jefferson – President in 1800

In 1796 Jefferson stood for President but lost narrowly to John Adams ; however, under the terms of the constitution, this was sufficient for him to become Vice President. In the run-up to the next election of 1800 Jefferson fought a bitter campaign. In particular, the Alien and Sedition Act of 1798 led to the imprisonment of many newspaper editors who supported Jefferson and were critical of the existing government. However, Jefferson was narrowly elected and this allowed him to promote open and representative government. On being elected, he offered a hand of friendship to his former political enemies. He also allowed the Sedition Act to expire and promoted the practical existence of free speech. The Presidency of Jefferson was eventful, but importantly he was able to preside over a period of relative stability and generally kept America out of conflict.

“I love peace, and am anxious that we should give the world still another useful lesson, by showing to them other modes of punishing injuries than by war, which is as much a punishment to the punisher as to the sufferer.”

At the time American neutrality was imperilled by the British-French wars, which raged around Canada. In 1803 Jefferson was able to double the size of the US, through the Louisiana Purchase, which gave America many states to the west. He also commissioned the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which crossed America seeking to explore and create friendships with the Native American populations.

Jefferson’s Retirement in Monticello

Thomas Jefferson’s Personal Life

Thomas Jefferson married Martha Wayles Skelton in 1772. Together they had six children, including one stillborn son. Martha Jefferson Randolph (1772–1836), Jane Randolph (1774–1775), a stillborn or unnamed son (1777), Mary Wayles (1778–1804), Lucy Elizabeth (1780–1781), and Lucy Elizabeth (1782–1785). Martha died only 10 years later. Thomas Jefferson remained single for the rest of his life. It was alleged that Jefferson fathered some of Sally Hemings’ daughters. Jefferson never denied it in public, but he did deny it private correspondence. There has never been any conclusive proof that this occurred.

Personal qualities

Jefferson was over 6’2″; this was very tall for his age. He didn’t relish public speaking, he preferred to express his opinions through his writings. His friends and family remarked on Jefferson’s many fine qualities. He was sympathetic and engaging in conversation. Never bored, he always found different avenues of interest to explore. Thomas Jefferson left a profound mark on America, through his influential shaping of the American constitution and political practices. Jefferson died at the age of 84 on the afternoon of July 4; it was the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. A few hours later on the same day, his longtime friend and fellow Founding Father John Adams also passed away. On his tombstone, Jefferson had inscribed three achievements he was proudest of:

HERE WAS BURIED THOMAS JEFFERSON AUTHOR OF THE DECLARATION OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE OF THE STATUTE OF VIRGINIA FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM AND FATHER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Biography of Thomas Jefferson ”, Oxford, UK – www.biographyonline.net . Published 22 June 2014 Last updated 22 October 2019.

Thomas Jefferson: A Life

Thomas Jefferson: A Life at Amazon

Light and Liberty – Quotes of Thomas Jefferson

Light and Liberty – Quotes of Thomas Jefferson at Amazon

Related pages

- Thomas Jefferson – Achievements

- Thomas Jefferson – minor accomplishments

- Thomas Jefferson’s views on religion

External Links

- Thomas Jefferson – Light and Liberty

- Monticello – The home of Thomas Jefferson

Mobile Menu Overlay

The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Ave NW Washington, DC 20500

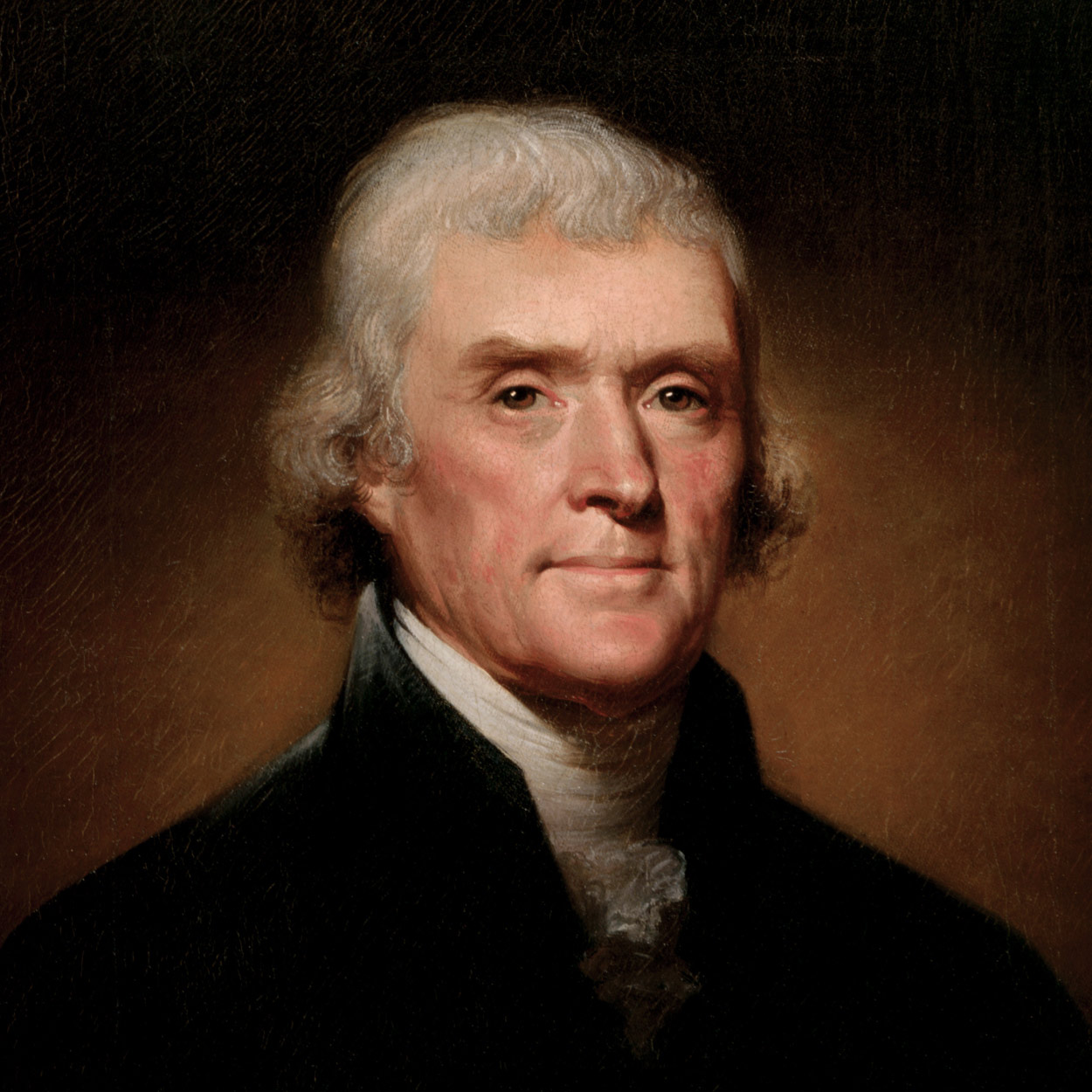

Thomas Jefferson

The 3rd President of the United States

The biography for President Jefferson and past presidents is courtesy of the White House Historical Association.

Thomas Jefferson, a spokesman for democracy, was an American Founding Father, the principal author of the Declaration of Independence (1776), and the third President of the United States (1801–1809).

In the thick of party conflict in 1800, Thomas Jefferson wrote in a private letter, “I have sworn upon the altar of God eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.”

This powerful advocate of liberty was born in 1743 in Albemarle County, Virginia, inheriting from his father, a planter and surveyor, some 5,000 acres of land, and from his mother, a Randolph, high social standing. He studied at the College of William and Mary, then read law. In 1772 he married Martha Wayles Skelton, a widow, and took her to live in his partly constructed mountaintop home, Monticello.

Freckled and sandy-haired, rather tall and awkward, Jefferson was eloquent as a correspondent, but he was no public speaker. In the Virginia House of Burgesses and the Continental Congress, he contributed his pen rather than his voice to the patriot cause. As the “silent member” of the Congress, Jefferson, at 33, drafted the Declaration of Independence. In years following he labored to make its words a reality in Virginia. Most notably, he wrote a bill establishing religious freedom, enacted in 1786.

Jefferson succeeded Benjamin Franklin as minister to France in 1785. His sympathy for the French Revolution led him into conflict with Alexander Hamilton when Jefferson was Secretary of State in President Washington’s Cabinet. He resigned in 1793.

Sharp political conflict developed, and two separate parties, the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans, began to form. Jefferson gradually assumed leadership of the Republicans, who sympathized with the revolutionary cause in France. Attacking Federalist policies, he opposed a strong centralized Government and championed the rights of states.

As a reluctant candidate for President in 1796, Jefferson came within three votes of election. Through a flaw in the Constitution, he became Vice President, although an opponent of President Adams. In 1800 the defect caused a more serious problem. Republican electors, attempting to name both a President and a Vice President from their own party, cast a tie vote between Jefferson and Aaron Burr. The House of Representatives settled the tie. Hamilton, disliking both Jefferson and Burr, nevertheless urged Jefferson’s election.

When Jefferson assumed the Presidency, the crisis in France had passed. He slashed Army and Navy expenditures, cut the budget, eliminated the tax on whiskey so unpopular in the West, yet reduced the national debt by a third. He also sent a naval squadron to fight the Barbary pirates, who were harassing American commerce in the Mediterranean. Further, although the Constitution made no provision for the acquisition of new land, Jefferson suppressed his qualms over constitutionality when he had the opportunity to acquire the Louisiana Territory from Napoleon in 1803.

During Jefferson’s second term, he was increasingly preoccupied with keeping the Nation from involvement in the Napoleonic wars, though both England and France interfered with the neutral rights of American merchantmen. Jefferson’s attempted solution, an embargo upon American shipping, worked badly and was unpopular.

Jefferson retired to Monticello to ponder such projects as his grand designs for the University of Virginia. A French nobleman observed that he had placed his house and his mind “on an elevated situation, from which he might contemplate the universe.”

He died on July 4, 1826.

Learn more about Thomas Jefferson’s spouse, Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson .

Stay Connected

We'll be in touch with the latest information on how President Biden and his administration are working for the American people, as well as ways you can get involved and help our country build back better.

Opt in to send and receive text messages from President Biden.

Help inform the discussion

U.S. Presidents / Thomas Jefferson

1743 - 1826

Thomas jefferson.

…some honest men fear that a republican government can not be strong, that this Government is not strong enough; but would the honest patriot…abandon a government which has so far kept us free and firm…? I trust not. I believe this, on the contrary, the strongest Government on earth. First Inaugural Address

Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, spent his childhood roaming the woods and studying his books on a remote plantation in the Virginia Piedmont. Thanks to the prosperity of his father, Jefferson had an excellent education. After years in boarding school, where he excelled in classical languages, Jefferson enrolled in William and Mary College in his home state of Virginia, taking classes in science, mathematics, rhetoric, philosophy, and literature. He also studied law, and by the time he was admitted to the Virginia bar in April 1767, many considered him to have one of the nation's best legal minds.

Life In Depth Essays

- Life in Brief

- Life Before the Presidency

- Campaigns and Elections

- Domestic Affairs

- Foreign Affairs

- Life After the Presidency

- Family Life

- The American Franchise

- Impact and Legacy

Chicago Style

Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “Thomas Jefferson.” Accessed April 24, 2024. https://millercenter.org/president/jefferson.

Professor of History

Professor Peter Onuf is the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation Professor of History at the University of Virginia.

- -The Mind of Thomas Jefferson

- -Jefferson's Empire: The Language of American Nationhood

- -Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson: History, Memory, and Civic Culture (editor…

Featured Insights

US Presidents and Slavery

Before the Civil War, many US presidents, including Jefferson, owned enslaved people, and all of them had to deal with slavery as a political issue

Thomas Jefferson’s electoral revolution of 1800

Alan Taylor, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Professor at the University of Virginia, talks about the transfer of power to President Jefferson during the election of 1800

Thomas Jefferson and the problem of Union

History professors Gary Gallagher and Peter Onuf discuss Thomas Jefferson as part of the Miller Center’s Historical Presidency series

American Gospel: God, the founding fathers, and the making of a nation

Jon Meacham discusses America's ongoing struggle between politics and religion and looks at how our founding fathers' views on faith shaped religion's place in American public life

March 4, 1801: First Inaugural Address

June 20, 1803: instructions to captain lewis, december 6, 1805: special message to congress on foreign policy, featured video.

Redeeming Thomas Jefferson?

This American Forum episode examines Thomas Jefferson with two of America’s most esteemed Jefferson scholars.

Featured Publications

U.S. Presidents

Thomas jefferson.

Third president of the United States

Thomas Jefferson was born near the Blue Ridge Mountains of the British-ruled colony of Virginia on April 13, 1743. From the age of nine, Jefferson studied away from home and lived with his tutor. His father—a landowner, surveyor, and government official—died when his son was 14. Later Jefferson enrolled at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. His education included science, mathematics, philosophy, law, English language and literature, Latin, Greek, French, and dancing.

"LIFE, LIBERTY, AND THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS"

After college, Jefferson became a lawyer. By age 26 he was a member of Virginia’s colonial legislature, or government. Like George Washington , Jefferson spoke out against Great Britain’s rule over the 13 North American colonies. When the colonists decided to demand their independence from Great Britain , Jefferson was chosen to write a document explaining why the colonies should be free. The document became known as the Declaration of Independence. It’s still admired today for its call for freedom, equality, and its demand that all citizens deserve "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness."

Before he became president, Jefferson was governor of Virginia before the Revolutionary War. After the war, he served as U.S. minister to France , secretary of state for President George Washington , and vice president for President John Adams, the country’s second president.

GO WEST, YOUNG NATION

When Jefferson became the third president of the United States in 1801, the country basically ended at the Mississippi River; France controlled much of what was west. That included the Port of New Orleans, in what is now Louisiana . It’s coastal location made it a key spot for trade—and Jefferson wanted it. In 1803, he made what’s known as one of the greatest real estate deals in history: the Louisiana Purchase .

France agreed to sell the entire city of New Orleans, which included the port, to the United States for $10 million; they threw in the rest of the territory they owned for an additional $5 million. The agreement—which gave the United States about 828,000 square miles of land—almost doubled the size of the nearly 30-year-old nation. Jefferson selected his personal secretary, Meriwether Lewis, to join William Clark in leading an expedition to the West Coast to explore the country’s new land. The Louisiana Purchase is thought by many to be Jefferson’s greatest accomplishment as president.

LASTING LEGACY

Jefferson retired to Monticello, his home in Charlottesville, Virginia, at the end of his second term. He designed and founded the University of Virginia in Charlottesville during his retirement.

Jefferson left a complicated legacy: The man who wrote the Declaration of Independence—which states that "all men are created equal"—also enslaved more than 600 people during his lifetime. But according to his writings, Jefferson knew that future generations would have to end the enslavement of people, and that it would be a long, terrible process.

Like his friend John Adams, Jefferson died 50 years to the day after the approval of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1826.

• Jefferson is credited with first introducing french fries to the United States.

• As secretary of state, Jefferson organized a contest to design the White House. Historians think he secretly entered—and lost.

• Jefferson loved cheese so much, a Massachusetts farmer once gifted him with a 1,300-pound piece.

From the Nat Geo Kids books Our Country's Presidents by Ann Bausum and Weird But True Know-It-All: U.S. Presidents by Brianna Dumont, revised for digital by Avery Hurt

(AD) "Weird But True Know-It-All: U.S. Presidents"

Independence day, (ad) "our country's presidents".

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your California Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell My Info

- National Geographic

- National Geographic Education

- Shop Nat Geo

- Customer Service

- Manage Your Subscription

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Skip to global NPS navigation

- Skip to this park navigation

- Skip to the main content

- Skip to this park information section

- Skip to the footer section

Exiting nps.gov

Alerts in effect, thomas jefferson.

Last updated: April 10, 2015

Park footer

Contact info, mailing address:.

11 North 4th Street St. Louis, MO 63102

314 655-1600

Stay Connected

President Thomas Jefferson

- The Louisiana Purchase - He bought a large section of land to the west of the original 13 colonies from Napoleon of France. Although much of this land was unsettled, it was so large it nearly doubled the size of the United States. He also made a really good deal buying all this land for only 15 million dollars.

- Lewis and Clark Expedition - Once he had bought the Louisiana Purchase, Jefferson needed to map the area and find out what was west of the country's land. He appointed Lewis and Clark to explore the western territory and report back on what was there.

- Battling Pirates - He sent American Navy ships to battle pirate ships on the coast of North Africa. These pirates had been attacking American merchant vessels, and Jefferson was determined to put a stop to it. This caused a minor war called the First Barbary War.

- Jefferson was also an accomplished architect. He designed his famous home at Monticello as well as buildings for the University of Virginia.

- He had nine brothers and sisters.

- The White House was called the Presidential Mansion at the time when he lived there. He kept things informal, often answering the front door himself.

- The U.S. Congress purchased Jefferson's book collection in order to help him get out of debt. There were approximately 6000 books which became the start of the Library of Congress.

- He wrote his own epitaph for his tombstone. On it he listed what he considered his major accomplishments. He did not include becoming president of the United States.

- Take a ten question quiz about this page.

- Listen to a recorded reading of this page:

Local Histories

Tim's History of British Towns, Cities and So Much More

A Brief Biography of Thomas Jefferson

By Tim Lambert

His Early Life

Thomas Jefferson was the third president of the USA. He was born on 13 April 1743 in Albemarle County, Virginia. His father Peter was a wealthy landowner. His mother was called Jane. However, his father died when he was 14 leaving him a substantial amount of land. In 1760 Thomas Jefferson went to the College of William and Mary.

Then in 1762, he began studying law. He was admitted to the bar in 1767. From 1769 to 1775 Jefferson was a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. In 1774 he wrote A Summary View of the Rights of British America. He argued that the British parliament had no authority over the American colonies who were bound to Britain only by loyalty to the king.

Meanwhile, in 1772 he married a woman named Martha Wayles Skelton. The couple had 6 children but only two (a daughter named Martha and another named Maria) survived childhood. Sadly Martha Senior died in 1782 aged only 33. Jefferson also had children by his slave, Sally Hemings.

The Statesman

In 1775 Jefferson became a member of the Second Continental Congress. He became one of 5 men appointed to write a declaration of independence and he was asked to write the first draft. It was edited by John Adams and Benjamin Franklin and also by the Continental Congress but the final version was adopted on 4 July 1776.

In 1776 Jefferson entered the Virginia House of Delegates where he worked to reform the laws. He drafted the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which was not passed till 1786. In 1779 he was elected governor of Virginia for a one-year term. He was elected again in 1780. However, in 1781, the British invaded Virginia. Jefferson was nearly captured but he fled to his estate at Poplar Forest. In 1783 Jefferson became a member of the Confederation Congress. He drafted the ordinance of 1784 which organized the western territories.

In 1784 he was sent to France to help negotiate trade treaties. In 1785 he became US minister to France. The same year, 1785 he published a book in Paris called Notes on the State of Virginia. The first English version was published in London in 1787. Jefferson returned to the USA in 1789.

The same year, 1789 Jefferson became US Secretary of State. However, he resigned in 1793. In 1796 he ran for the presidency but lost against John Adams. He did however become vice president. Jefferson ran for the presidency again in 1800. This time he was elected.

Jefferson is best remembered for the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. He was reelected in 1804. He retired in 1809. Jefferson helped to found the University of Virginia in 1819. Thomas Jefferson died on 4 July 1826. He was 83 years old.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

My Journey Through the Best Presidential Biographies

The Best Biographies of Thomas Jefferson

16 Thursday May 2013

Posted by Steve in Best Biographies Posts , President #03 - T Jefferson

≈ 62 Comments

American history , best biographies , book reviews , Dumas Malone , John Boles , Jon Meacham , Joseph Ellis , Kevin Hayes , Merrill Peterson , presidential biographies , Presidents , Thomas Jefferson , Willard Sterne Randall

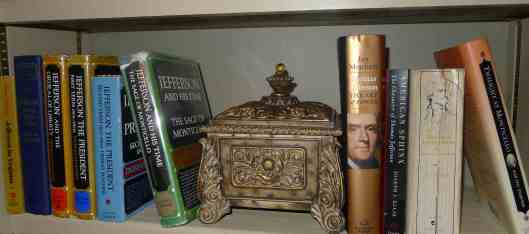

After nearly two months with Thomas Jefferson involving five biographies (ten books in total) and over 5,000 pages of reading, I still feel I know Jefferson less well than many other revolutionary-era figures…including some like Alexander Hamilton who I’ve only encountered through his numerous appearances in various presidential biographies.

But that’s part of the intriguing mystery that Jefferson presents – even the most dedicated Jefferson scholars such as Malone and Peterson have admitted difficulty in getting to know our third president on a personal level. In his biography of Jefferson, Merrill Peterson acknowledged being mortified in confessing he still found Jefferson “impenetrable” after years of study.

Part of what seems to make Jefferson so complex is that he is not merely a two-dimensional figure. The set of internal rules governing his behavior resembles a multi-variable differential equation whose output seems maddeningly inconsistent at times. But on a basic level, Jefferson is no different than most of us – guided by a small number of core convictions, steered by a larger set of general principles, and influenced by a broad group of more nebulous forces.

Only that smallest group of convictions seemed to guide Jefferson as if they were immutable laws of physics. His other principles and beliefs were more maleable, able to change under great strain, competing forces, or compelling circumstances of the moment. He was a passionately private man, yet ended up in public office for most of his adult life. He professed the evils of slavery, yet owned slaves (and may have even had a long-term relationship with one). He was intensely afraid of the power of a broad federal government under the direction of a strong president, yet as president did very little to curb that power and in many instances did just the opposite.

* Dumas Malone’s six-volume series (“Jefferson and His Time”) took over three decades to complete – it was begun when my parents were not old enough to walk, and finished when I was almost entering middle school. This series, to which Malone dedicated a huge chunk of his adult life, took me just five (rather intense) weeks to read.

Although this series does not receive high marks as a means of “entertainment” it receives the very best marks for its content and scholarship. The first five volumes won the Pulitzer Prize in 1975.

Volume 1 (“Jefferson the Virginian”) covers the first four decades of Jefferson’s life, up to the point when became a diplomat in Europe. Volume 2 (“Jefferson and the Rights of Man”) covers the years 1784-1792 which Jefferson spent in Europe as a diplomat and as George Washington’s first Secretary of State.

Volume 3 (“Jefferson and the Ordeal of Liberty”) covers the last year of Jefferson’s tenure as Secretary of State, his three-year retirement at Monticello, his years as John Adams’ Vice President and his election to the presidency in 1800. Volumes 4 and 5 (“Jefferson the President”) cover his eight year presidency while Volume 6 (“The Sage of Monticello”) covers the final seventeen years of Jefferson’s life.

As thorough and comprehensive as any biography on Jefferson could possibly be, the series suffers only from being less “readable” than more recent biographies which are written in modern, well-flowing verse, and perhaps for not addressing the Hemings controversy with evidence that has only recently come to light.

Malone’s series on Thomas Jefferson reminds me of Thomas Flexner’s series on Washington and Page Smith’s on John Adams – together, these three great works are in a class all to themselves. (Full reviews: Vol 1 , Vol 2 , Vol 3 , Vol 4 , Vol 5 , Vol 6 )

Merrill Peterson’s “ Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation, ” published in 1970, was written while Malone was about halfway through his series on Jefferson. In no other single-volume biography of any of our first three presidents can a reader find a more comprehensive book, chock-a-block with such an impressive level of relevant detail. Yet compared to Malone’s series, while it seems to contain proportionately similar granularity, it also seems to contain relatively fewer interesting conclusory remarks and insights.

Without a doubt, no serious library would be complete without a copy of Peterson’s classic. But with the benefit of hindsight, if I were forced to choose between reading Malone’s six-volume series or Peterson’s single-volume biography, I would not hesitate to invest the additional time required to experience Malone’s series. ( Full review here )

Joseph Ellis’s “ American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson ” was published in 1996, three years after he published his biography of John Adams. This is by far my favorite of Ellis’s books, and the second most “enjoyable” read among the Jefferson biographies.

Like each of Ellis’s works I’ve read so far, this book is not quite a biography and should not be read as such. In my opinion, the best way to enjoy “American Sphinx” is to first read either Malone’s series or Peterson’s biography. Ellis not only observes Jefferson’s behavior throughout life, as have other authors, but also synthesizes his observations into a set of characteristics that seems to have defined Jefferson’s personality. This book comes as close to getting into Jefferson’s mind as any book I’ve read. ( Full review here )

“ Twilight at Monticello: The Final Years of Thomas Jefferson ” by Alan Pell Crawford was published in 2008 and, despite a number of imperfections, proves quite an enjoyable and easy read. Although it exudes a slight tabloid “feel” Crawford has exploited a niche never before fully explored – even Malone’s last volume focusing on Jefferson’s retirement years seems slightly incomplete in hindsight.

By the end of the book, though, it feels as thought the author may have tried too hard to make his case. Rather than coming across as insightful and revealing, the book finally beings to feel hyperbolic and melodramatic. Nonetheless, as my next-to-last book on Jefferson, it was perfectly timed and absorbingly provocative. ( Full review here )

“ Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power ” by Jon Meacham was published in 2012 and is currently the most popular of the Jefferson biographies. As I’ve discovered from readers of this site, Meacham is a polarizing author. Those who love him do so because his primary mission seems to be to entertain and, only secondarily, to inform. Others find him distressing for exactly the same reason, sensing that he merely puts new wrapping paper on an old treasure.

But no matter your take on Meacham, “The Art of Power” is both easy and enjoyable to read. At times it is thoroughly engrossing and contains its own interesting perspective on Jefferson’s life. Although it is lighter on penetrating, recently-uncovered insights and heavier on clever one-liners than previous Jefferson biographies, it probably serves as the perfect “second” biography of Jefferson. ( Full review here )

– – – – – – –

[ Added January 2020 ]

* In 2013, I read four single-volume biographies of Jefferson and the six-volume series described above. Since then I’ve had the chance to read a biography of Jefferson I missed on that first trip through Jefferson: Willard Sterne Randall’s “ Thomas Jefferson: A Life ” which was published in 1993. But while it is uniquely valuable as a study of Jefferson’s legal studies and career, it covers most of the remainder of his life – including his presidency – with less dexterity and it turned out to be my least-favorite biography of Jefferson thus far. ( Full review here )

[ Added October 2021 ]

* I’ve also now read John Boles’s 2017 biography “ Jefferson: Architect of American Liberty .” With 520 pages of text, this biography proves uncommonly thoughtful, thorough and revealing. Boles expends no small effort in attempting to unravel Jefferson’s complexity and perplexing contradictions – including the large gap between his attitude toward slavery and his actions – and here the book is quite successful. Less ideal is the relative lack of focus on understanding and revealing Jefferson’s friendships with figures such as James Madison and John Adams. And Boles’s writing style, while crisp and articulate, is rarely particularly colorful or engrossing. But overall this is perhaps the best modern, single-volume introduction to Jefferson’s life and times. ( Full review here )

[ Added August 2022 ]

* Published in 2008, Kevin Hayes’s “ The Road to Monticello: The Life and Mind of Thomas Jefferson ” is a dense, detailed 644-page intellectual biography of the third president focused on the literature he read, wrote and collected. Although it provides much of the framework of a traditional biography, it is decidedly not one and cannot serve as an adequate substitute for anyone seeking a thorough and broad introduction to Jefferson. The natural audience for this book is quite limited, but for someone already familiar with T.J. who is interested in exploring his intellectual evolution through an analysis of the words that shaped his world, this book may prove ideal. ( Full review here )

[ Added December 2022 ]

* Published two weeks ago, Fred Kaplan’s “ His Masterly Pen: A Biography of Jefferson the Writer ” resembles Kevin Hayes’s “The Road to Monticello” – in spirit . However, the two books are quite different in approach. This book by Kaplan looks deceptively like a traditional biography – its chapters proceed chronologically and the narrative includes large chunks of Jefferson’s non -literary life. But it’s focus is on understanding Jefferson’s character, contradictions and philosophy as revealed by his letters, speeches, declarations and books (and not by the books he bought, borrowed or merely read). As a supplemental text for readers acquainted with Jefferson, this book may prove uniquely intellectual and insightful. For readers seeking a traditional biography of Jefferson it is not ideal. ( Full review here )

Best Overall: Dumas Malone’s six-volume series

Most Enjoyable Biography: “ Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power ”

Best Single-Volume Biography: “ Jefferson: Architect of American Liberty ”

Share this:

62 thoughts on “the best biographies of thomas jefferson”.

May 25, 2013 at 9:24 pm

It’s sad how so many modern “scholars” now dismiss Malone’s work.

May 26, 2013 at 4:33 pm

Reblogged this on Practically Historical .

May 17, 2020 at 6:21 pm

Great website. Fantastic overviews of presidential historiography.

I believe you are a bit easy perhaps on Malone re: the Hemmings issue with “and perhaps for not addressing the Hemings controversy with evidence that has only recently come to light.”

Malone, of course did not have DNA, however, if you look closely at the evidence he did have, he systematically approached what was available to reach a preconceived conclusion. Malone knew that Sally’s children were TJ’s and wrote it otherwise. He simply could not abandon his position as the pied piper of the TJ cult.

And while his work is masterful. It is important to understand his limitations in being objective.

October 15, 2013 at 12:59 pm

Unfortunately I started my book on TJ – “In Pursuit of Reason” by Noble Cunningham – before discovering your blog, and stupidly chose it only because it was $1 in my library’s bookstore. It wasn’t awful, just not terribly well written or compelling. I’ll happily admit that I’m interested in the presidents’ family lives as well as their political lives, and this was one shortcoming in Cunningham’s book, though not the only one. I think it’s a problem that the author did not even mention the Sally Hemings scandal, since it did come out during TJ’s presidency, via a man who had turned against TJ. The scandal was discussed in McCullough’s book on John Adams, and in the book I just finished on Madison (by Brookhiser). To have it ignored in a TJ bio seemed disingenuous, to put it nicely. I honestly feel I learned more about TJ the man (not the pol) from the Adams bio than from Cunningham’s book!

April 5, 2014 at 9:17 am

Just discovered your site — really good work. In your work on Jefferson did you run into any assessment of Fawn Brodie’s controversial bio?

May 24, 2014 at 5:46 am

Not in the biographies themselves, but there were numerous references to Fawn Brodie’s work in reviews I later read of the books I had read, and one of my frequent visitors makes no secret of his views: http://practicallyhistorical.net/?s=fawn+brodie

April 5, 2014 at 9:39 am

In your readings on Jefferson, did you ever run into any assessments of Fawn Brodie’s controversial biography?

April 5, 2014 at 1:42 pm

None of the books I read referenced Brodie’s biography in a substantive way (not that I remember, anyway) though I recall thee book being referenced in the bibliography of a few. I shied away from Brodie when I was selecting Jefferson bios to read given the overwhelming and consistently negative feedback I saw, but it’s on my “must read” list for my second pass through the presidents – out of curiosity, if nothing else.

April 5, 2014 at 1:51 pm

I also found the following assessment of Brodie’s biography thought-provoking (so much so that it convinced me to add the book to my follow-up list on Jefferson: http://practicallyhistorical.net/2013/03/06/classic-historical-takedowns-pt-1-2/

April 14, 2015 at 2:31 pm

I’d also toss into the mix Henry Wiencek’s “Master of the Mountain.” Like American Sphinx, not a full bio, and even less complimentary. But a fully documented dismantling of many of the myths that surround Jefferson and much Jefferson scholarship.

June 13, 2015 at 1:09 pm

I have also been reading presidential bios in order and am just finishing Trefousse’s Andrew Johnson. I’m wondering if you read Willard Sterne Randall’s Jefferson: A Life and what your thoughts were. So glad to find your blog….onto Grant!

June 14, 2015 at 6:21 pm

Good luck finishing up the A Johnson bio(!) I have not read Willard Sterne Randall’s bio of Jefferson – if you have, let me know what you thought. I seem to remember looking it up and finding it got mixed reviews, and since I had what I thought was a full plate of Jefferson bios I didn’t add it into the mix.

June 17, 2015 at 7:38 am

Randall did a very good job of detailing Jefferson’s early life. His Presidency was not emphasized as much, but there are plenty of other great books that do that as you have pointed out. The focus is more on his early life and his years in France. It was a nice insight into the man. Randall’s writing style can be a bit meandering and repetitive, something that he corrects in his Alexander Hamilton bio, but overall I felt It was a worthy read.

November 5, 2015 at 4:29 pm

One short bio that merits attention is RB Bernstein’s very fine study for Oxford’s series of shorter biographies. I recall a lot of insight in a very little space (<300 pages) in this volume. Felt like I had a better understanding of the man and his legacy than Meacham.

November 6, 2015 at 7:27 am

Thanks, I’ve had a couple people tell me I need to read that one (as sort of a turbo-charged substitute for an American President Series bio of Jefferson) so I’ll probably add it to my follow-up list.

September 22, 2017 at 5:37 pm

I agree enthusiastically with you about the brief R.B. Bernstein biography of Thomas Jefferson.

March 3, 2016 at 7:19 pm

not even a mention of Henry Adams’s work on the jefferson administration?

March 10, 2016 at 3:37 pm