- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of essay

(Entry 1 of 2)

Definition of essay (Entry 2 of 2)

transitive verb

- composition

attempt , try , endeavor , essay , strive mean to make an effort to accomplish an end.

attempt stresses the initiation or beginning of an effort.

try is often close to attempt but may stress effort or experiment made in the hope of testing or proving something.

endeavor heightens the implications of exertion and difficulty.

essay implies difficulty but also suggests tentative trying or experimenting.

strive implies great exertion against great difficulty and specifically suggests persistent effort.

Examples of essay in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'essay.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Middle French essai , ultimately from Late Latin exagium act of weighing, from Latin ex- + agere to drive — more at agent

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 4

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 2

Phrases Containing essay

- essay question

- photo - essay

Articles Related to essay

To 'Essay' or 'Assay'?

You'll know the difference if you give it the old college essay

Dictionary Entries Near essay

Cite this entry.

“Essay.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/essay. Accessed 25 Mar. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of essay.

Kids Definition of essay (Entry 2 of 2)

More from Merriam-Webster on essay

Nglish: Translation of essay for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of essay for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about essay

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

8 grammar terms you used to know, but forgot, homophones, homographs, and homonyms, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - mar. 22, 12 words for signs of spring, 9 superb owl words, 'gaslighting,' 'woke,' 'democracy,' and other top lookups, fan favorites: your most liked words of the day 2023, games & quizzes.

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of essay in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- I want to finish off this essay before I go to bed .

- His essay was full of spelling errors .

- Have you given that essay in yet ?

- Have you handed in your history essay yet ?

- I'd like to discuss the first point in your essay.

- boilerplate

- composition

- dissertation

- essay question

- peer review

- go after someone

- go all out idiom

- go down swinging/fighting idiom

- go for it idiom

- go for someone

- shoot the works idiom

- smarten (someone/something) up

- smarten up your act idiom

- square the circle idiom

- step on the gas idiom

essay | Intermediate English

Examples of essay, collocations with essay.

These are words often used in combination with essay .

Click on a collocation to see more examples of it.

Translations of essay

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

doctor's orders

used to mean that you must do something because your doctor has told you to do it

Paying attention and listening intently: talking about concentration

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Noun Verb

- Intermediate Noun

- Collocations

- Translations

- All translations

Add essay to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

What an Essay Is and How to Write One

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

Essays are brief, non-fiction compositions that describe, clarify, argue, or analyze a subject. Students might encounter essay assignments in any school subject and at any level of school, from a personal experience "vacation" essay in middle school to a complex analysis of a scientific process in graduate school. Components of an essay include an introduction , thesis statement , body, and conclusion.

Writing an Introduction

The beginning of an essay can seem daunting. Sometimes, writers can start their essay in the middle or at the end, rather than at the beginning, and work backward. The process depends on each individual and takes practice to figure out what works best for them. Regardless of where students start, it is recommended that the introduction begins with an attention grabber or an example that hooks the reader in within the very first sentence.

The introduction should accomplish a few written sentences that leads the reader into the main point or argument of the essay, also known as a thesis statement. Typically, the thesis statement is the very last sentence of an introduction, but this is not a rule set in stone, despite it wrapping things up nicely. Before moving on from the introduction, readers should have a good idea of what is to follow in the essay, and they should not be confused as to what the essay is about. Finally, the length of an introduction varies and can be anywhere from one to several paragraphs depending on the size of the essay as a whole.

Creating a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is a sentence that states the main idea of the essay. The function of a thesis statement is to help manage the ideas within the essay. Different from a mere topic, the thesis statement is an argument, option, or judgment that the author of the essay makes about the topic of the essay.

A good thesis statement combines several ideas into just one or two sentences. It also includes the topic of the essay and makes clear what the author's position is in regard to the topic. Typically found at the beginning of a paper, the thesis statement is often placed in the introduction, toward the end of the first paragraph or so.

Developing a thesis statement means deciding on the point of view within the topic, and stating this argument clearly becomes part of the sentence which forms it. Writing a strong thesis statement should summarize the topic and bring clarity to the reader.

For informative essays, an informative thesis should be declared. In an argumentative or narrative essay, a persuasive thesis, or opinion, should be determined. For instance, the difference looks like this:

- Informative Thesis Example: To create a great essay, the writer must form a solid introduction, thesis statement, body, and conclusion.

- Persuasive Thesis Example: Essays surrounded around opinions and arguments are so much more fun than informative essays because they are more dynamic, fluid, and teach you a lot about the author.

Developing Body Paragraphs

The body paragraphs of an essay include a group of sentences that relate to a specific topic or idea around the main point of the essay. It is important to write and organize two to three full body paragraphs to properly develop it.

Before writing, authors may choose to outline the two to three main arguments that will support their thesis statement. For each of those main ideas, there will be supporting points to drive them home. Elaborating on the ideas and supporting specific points will develop a full body paragraph. A good paragraph describes the main point, is full of meaning, and has crystal clear sentences that avoid universal statements.

Ending an Essay With a Conclusion

A conclusion is an end or finish of an essay. Often, the conclusion includes a judgment or decision that is reached through the reasoning described throughout the essay. The conclusion is an opportunity to wrap up the essay by reviewing the main points discussed that drives home the point or argument stated in the thesis statement.

The conclusion may also include a takeaway for the reader, such as a question or thought to take with them after reading. A good conclusion may also invoke a vivid image, include a quotation, or have a call to action for readers.

- How To Write an Essay

- The Ultimate Guide to the 5-Paragraph Essay

- An Introduction to Academic Writing

- Definition and Examples of Body Paragraphs in Composition

- How to Structure an Essay

- How to Help Your 4th Grader Write a Biography

- What Is Expository Writing?

- Write an Attention-Grabbing Opening Sentence for an Essay

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- How to Write a Solid Thesis Statement

- Unity in Composition

- How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

- An Essay Revision Checklist

- 6 Steps to Writing the Perfect Personal Essay

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- The Five Steps of Writing an Essay

What is an Essay?

10 May, 2020

11 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

Well, beyond a jumble of words usually around 2,000 words or so - what is an essay, exactly? Whether you’re taking English, sociology, history, biology, art, or a speech class, it’s likely you’ll have to write an essay or two. So how is an essay different than a research paper or a review? Let’s find out!

Defining the Term – What is an Essay?

The essay is a written piece that is designed to present an idea, propose an argument, express the emotion or initiate debate. It is a tool that is used to present writer’s ideas in a non-fictional way. Multiple applications of this type of writing go way beyond, providing political manifestos and art criticism as well as personal observations and reflections of the author.

An essay can be as short as 500 words, it can also be 5000 words or more. However, most essays fall somewhere around 1000 to 3000 words ; this word range provides the writer enough space to thoroughly develop an argument and work to convince the reader of the author’s perspective regarding a particular issue. The topics of essays are boundless: they can range from the best form of government to the benefits of eating peppermint leaves daily. As a professional provider of custom writing, our service has helped thousands of customers to turn in essays in various forms and disciplines.

Origins of the Essay

Over the course of more than six centuries essays were used to question assumptions, argue trivial opinions and to initiate global discussions. Let’s have a closer look into historical progress and various applications of this literary phenomenon to find out exactly what it is.

Today’s modern word “essay” can trace its roots back to the French “essayer” which translates closely to mean “to attempt” . This is an apt name for this writing form because the essay’s ultimate purpose is to attempt to convince the audience of something. An essay’s topic can range broadly and include everything from the best of Shakespeare’s plays to the joys of April.

The essay comes in many shapes and sizes; it can focus on a personal experience or a purely academic exploration of a topic. Essays are classified as a subjective writing form because while they include expository elements, they can rely on personal narratives to support the writer’s viewpoint. The essay genre includes a diverse array of academic writings ranging from literary criticism to meditations on the natural world. Most typically, the essay exists as a shorter writing form; essays are rarely the length of a novel. However, several historic examples, such as John Locke’s seminal work “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding” just shows that a well-organized essay can be as long as a novel.

The Essay in Literature

The essay enjoys a long and renowned history in literature. They first began gaining in popularity in the early 16 th century, and their popularity has continued today both with original writers and ghost writers. Many readers prefer this short form in which the writer seems to speak directly to the reader, presenting a particular claim and working to defend it through a variety of means. Not sure if you’ve ever read a great essay? You wouldn’t believe how many pieces of literature are actually nothing less than essays, or evolved into more complex structures from the essay. Check out this list of literary favorites:

- The Book of My Lives by Aleksandar Hemon

- Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

- Against Interpretation by Susan Sontag

- High-Tide in Tucson: Essays from Now and Never by Barbara Kingsolver

- Slouching Toward Bethlehem by Joan Didion

- Naked by David Sedaris

- Walden; or, Life in the Woods by Henry David Thoreau

Pretty much as long as writers have had something to say, they’ve created essays to communicate their viewpoint on pretty much any topic you can think of!

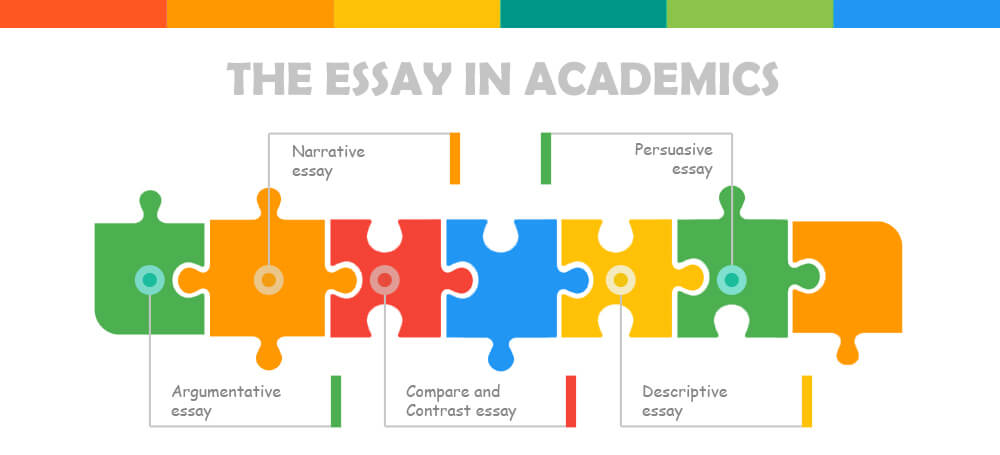

The Essay in Academics

Not only are students required to read a variety of essays during their academic education, but they will likely be required to write several different kinds of essays throughout their scholastic career. Don’t love to write? Then consider working with a ghost essay writer ! While all essays require an introduction, body paragraphs in support of the argumentative thesis statement, and a conclusion, academic essays can take several different formats in the way they approach a topic. Common essays required in high school, college, and post-graduate classes include:

Five paragraph essay

This is the most common type of a formal essay. The type of paper that students are usually exposed to when they first hear about the concept of the essay itself. It follows easy outline structure – an opening introduction paragraph; three body paragraphs to expand the thesis; and conclusion to sum it up.

Argumentative essay

These essays are commonly assigned to explore a controversial issue. The goal is to identify the major positions on either side and work to support the side the writer agrees with while refuting the opposing side’s potential arguments.

Compare and Contrast essay

This essay compares two items, such as two poems, and works to identify similarities and differences, discussing the strength and weaknesses of each. This essay can focus on more than just two items, however. The point of this essay is to reveal new connections the reader may not have considered previously.

Definition essay

This essay has a sole purpose – defining a term or a concept in as much detail as possible. Sounds pretty simple, right? Well, not quite. The most important part of the process is picking up the word. Before zooming it up under the microscope, make sure to choose something roomy so you can define it under multiple angles. The definition essay outline will reflect those angles and scopes.

Descriptive essay

Perhaps the most fun to write, this essay focuses on describing its subject using all five of the senses. The writer aims to fully describe the topic; for example, a descriptive essay could aim to describe the ocean to someone who’s never seen it or the job of a teacher. Descriptive essays rely heavily on detail and the paragraphs can be organized by sense.

Illustration essay

The purpose of this essay is to describe an idea, occasion or a concept with the help of clear and vocal examples. “Illustration” itself is handled in the body paragraphs section. Each of the statements, presented in the essay needs to be supported with several examples. Illustration essay helps the author to connect with his audience by breaking the barriers with real-life examples – clear and indisputable.

Informative Essay

Being one the basic essay types, the informative essay is as easy as it sounds from a technical standpoint. High school is where students usually encounter with informative essay first time. The purpose of this paper is to describe an idea, concept or any other abstract subject with the help of proper research and a generous amount of storytelling.

Narrative essay

This type of essay focuses on describing a certain event or experience, most often chronologically. It could be a historic event or an ordinary day or month in a regular person’s life. Narrative essay proclaims a free approach to writing it, therefore it does not always require conventional attributes, like the outline. The narrative itself typically unfolds through a personal lens, and is thus considered to be a subjective form of writing.

Persuasive essay

The purpose of the persuasive essay is to provide the audience with a 360-view on the concept idea or certain topic – to persuade the reader to adopt a certain viewpoint. The viewpoints can range widely from why visiting the dentist is important to why dogs make the best pets to why blue is the best color. Strong, persuasive language is a defining characteristic of this essay type.

The Essay in Art

Several other artistic mediums have adopted the essay as a means of communicating with their audience. In the visual arts, such as painting or sculpting, the rough sketches of the final product are sometimes deemed essays. Likewise, directors may opt to create a film essay which is similar to a documentary in that it offers a personal reflection on a relevant issue. Finally, photographers often create photographic essays in which they use a series of photographs to tell a story, similar to a narrative or a descriptive essay.

Drawing the line – question answered

“What is an Essay?” is quite a polarizing question. On one hand, it can easily be answered in a couple of words. On the other, it is surely the most profound and self-established type of content there ever was. Going back through the history of the last five-six centuries helps us understand where did it come from and how it is being applied ever since.

If you must write an essay, follow these five important steps to works towards earning the “A” you want:

- Understand and review the kind of essay you must write

- Brainstorm your argument

- Find research from reliable sources to support your perspective

- Cite all sources parenthetically within the paper and on the Works Cited page

- Follow all grammatical rules

Generally speaking, when you must write any type of essay, start sooner rather than later! Don’t procrastinate – give yourself time to develop your perspective and work on crafting a unique and original approach to the topic. Remember: it’s always a good idea to have another set of eyes (or three) look over your essay before handing in the final draft to your teacher or professor. Don’t trust your fellow classmates? Consider hiring an editor or a ghostwriter to help out!

If you are still unsure on whether you can cope with your task – you are in the right place to get help. HandMadeWriting is the perfect answer to the question “Who can write my essay?”

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Grammar Coach ™

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

a short literary composition on a particular theme or subject, usually in prose and generally analytic, speculative, or interpretative.

anything resembling such a composition: a picture essay.

an effort to perform or accomplish something; attempt.

Philately . a design for a proposed stamp differing in any way from the design of the stamp as issued.

Obsolete . a tentative effort; trial; assay.

to try; attempt.

to put to the test; make trial of.

Origin of essay

Other words from essay.

- es·say·er, noun

- pre·es·say, verb (used without object)

- un·es·sayed, adjective

- well-es·sayed, adjective

Words that may be confused with essay

- assay , essay

Words Nearby essay

- essay question

Dictionary.com Unabridged Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2024

How to use essay in a sentence

As several of my colleagues commented, the result is good enough that it could pass for an essay written by a first-year undergraduate, and even get a pretty decent grade.

GPT-3 also raises concerns about the future of essay writing in the education system.

This little essay helps focus on self-knowledge in what you’re best at, and how you should prioritize your time.

As Steven Feldstein argues in the opening essay , technonationalism plays a part in the strengthening of other autocracies too.

He’s written a collection of essays on civil engineering life titled Bridginess, and to this day he and Lauren go on “bridge dates,” where they enjoy a meal and admire the view of a nearby span.

I think a certain kind of compelling essay has a piece of that.

The current attack on the Jews,” he wrote in a 1937 essay , “targets not just this people of 15 million but mankind as such.

The impulse to interpret seems to me what makes personal essay writing compelling.

To be honest, I think a lot of good essay writing comes out of that.

Someone recently sent me an old Joan Didion essay on self-respect that appeared in Vogue.

There is more of the uplifted forefinger and the reiterated point than I should have allowed myself in an essay .

Consequently he was able to turn in a clear essay upon the subject, which, upon examination, the king found to be free from error.

It is no part of the present essay to attempt to detail the particulars of a code of social legislation.

But angels and ministers of grace defend us from ministers of religion who essay art criticism!

It is fit that the imagination, which is free to go through all things, should essay such excursions.

British Dictionary definitions for essay

a short literary composition dealing with a subject analytically or speculatively

an attempt or endeavour; effort

a test or trial

to attempt or endeavour; try

to test or try out

Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition © William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

Cultural definitions for essay

A short piece of writing on one subject, usually presenting the author's own views. Michel de Montaigne , Francis Bacon (see also Bacon ), and Ralph Waldo Emerson are celebrated for their essays.

The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Third Edition Copyright © 2005 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Tips for Writing an Effective Application Essay

How to Write an Effective Essay

Writing an essay for college admission gives you a chance to use your authentic voice and show your personality. It's an excellent opportunity to personalize your application beyond your academic credentials, and a well-written essay can have a positive influence come decision time.

Want to know how to draft an essay for your college application ? Here are some tips to keep in mind when writing.

Tips for Essay Writing

A typical college application essay, also known as a personal statement, is 400-600 words. Although that may seem short, writing about yourself can be challenging. It's not something you want to rush or put off at the last moment. Think of it as a critical piece of the application process. Follow these tips to write an impactful essay that can work in your favor.

1. Start Early.

Few people write well under pressure. Try to complete your first draft a few weeks before you have to turn it in. Many advisers recommend starting as early as the summer before your senior year in high school. That way, you have ample time to think about the prompt and craft the best personal statement possible.

You don't have to work on your essay every day, but you'll want to give yourself time to revise and edit. You may discover that you want to change your topic or think of a better way to frame it. Either way, the sooner you start, the better.

2. Understand the Prompt and Instructions.

Before you begin the writing process, take time to understand what the college wants from you. The worst thing you can do is skim through the instructions and submit a piece that doesn't even fit the bare minimum requirements or address the essay topic. Look at the prompt, consider the required word count, and note any unique details each school wants.

3. Create a Strong Opener.

Students seeking help for their application essays often have trouble getting things started. It's a challenging writing process. Finding the right words to start can be the hardest part.

Spending more time working on your opener is always a good idea. The opening sentence sets the stage for the rest of your piece. The introductory paragraph is what piques the interest of the reader, and it can immediately set your essay apart from the others.

4. Stay on Topic.

One of the most important things to remember is to keep to the essay topic. If you're applying to 10 or more colleges, it's easy to veer off course with so many application essays.

A common mistake many students make is trying to fit previously written essays into the mold of another college's requirements. This seems like a time-saving way to avoid writing new pieces entirely, but it often backfires. The result is usually a final piece that's generic, unfocused, or confusing. Always write a new essay for every application, no matter how long it takes.

5. Think About Your Response.

Don't try to guess what the admissions officials want to read. Your essay will be easier to write─and more exciting to read─if you’re genuinely enthusiastic about your subject. Here’s an example: If all your friends are writing application essays about covid-19, it may be a good idea to avoid that topic, unless during the pandemic you had a vivid, life-changing experience you're burning to share. Whatever topic you choose, avoid canned responses. Be creative.

6. Focus on You.

Essay prompts typically give you plenty of latitude, but panel members expect you to focus on a subject that is personal (although not overly intimate) and particular to you. Admissions counselors say the best essays help them learn something about the candidate that they would never know from reading the rest of the application.

7. Stay True to Your Voice.

Use your usual vocabulary. Avoid fancy language you wouldn't use in real life. Imagine yourself reading this essay aloud to a classroom full of people who have never met you. Keep a confident tone. Be wary of words and phrases that undercut that tone.

8. Be Specific and Factual.

Capitalize on real-life experiences. Your essay may give you the time and space to explain why a particular achievement meant so much to you. But resist the urge to exaggerate and embellish. Admissions counselors read thousands of essays each year. They can easily spot a fake.

9. Edit and Proofread.

When you finish the final draft, run it through the spell checker on your computer. Then don’t read your essay for a few days. You'll be more apt to spot typos and awkward grammar when you reread it. After that, ask a teacher, parent, or college student (preferably an English or communications major) to give it a quick read. While you're at it, double-check your word count.

Writing essays for college admission can be daunting, but it doesn't have to be. A well-crafted essay could be the deciding factor─in your favor. Keep these tips in mind, and you'll have no problem creating memorable pieces for every application.

What is the format of a college application essay?

Generally, essays for college admission follow a simple format that includes an opening paragraph, a lengthier body section, and a closing paragraph. You don't need to include a title, which will only take up extra space. Keep in mind that the exact format can vary from one college application to the next. Read the instructions and prompt for more guidance.

Most online applications will include a text box for your essay. If you're attaching it as a document, however, be sure to use a standard, 12-point font and use 1.5-spaced or double-spaced lines, unless the application specifies different font and spacing.

How do you start an essay?

The goal here is to use an attention grabber. Think of it as a way to reel the reader in and interest an admissions officer in what you have to say. There's no trick on how to start a college application essay. The best way you can approach this task is to flex your creative muscles and think outside the box.

You can start with openers such as relevant quotes, exciting anecdotes, or questions. Either way, the first sentence should be unique and intrigue the reader.

What should an essay include?

Every application essay you write should include details about yourself and past experiences. It's another opportunity to make yourself look like a fantastic applicant. Leverage your experiences. Tell a riveting story that fulfills the prompt.

What shouldn’t be included in an essay?

When writing a college application essay, it's usually best to avoid overly personal details and controversial topics. Although these topics might make for an intriguing essay, they can be tricky to express well. If you’re unsure if a topic is appropriate for your essay, check with your school counselor. An essay for college admission shouldn't include a list of achievements or academic accolades either. Your essay isn’t meant to be a rehashing of information the admissions panel can find elsewhere in your application.

How can you make your essay personal and interesting?

The best way to make your essay interesting is to write about something genuinely important to you. That could be an experience that changed your life or a valuable lesson that had an enormous impact on you. Whatever the case, speak from the heart, and be honest.

Is it OK to discuss mental health in an essay?

Mental health struggles can create challenges you must overcome during your education and could be an opportunity for you to show how you’ve handled challenges and overcome obstacles. If you’re considering writing your essay for college admission on this topic, consider talking to your school counselor or with an English teacher on how to frame the essay.

Related Articles

Home — Essay Samples — Life — House — What Does Home Mean to You

What Does Home Mean to You

- Categories: Hometown House Positive Psychology

About this sample

Words: 1251 |

Updated: 6 November, 2023

Words: 1251 | Pages: 3 | 7 min read

“What I love most about my home is who I share it with.” “There is nothing more important than a good, safe, secure home.” “Home is a place you grow up wanting to leave, and grow old wanting to get back to.”

You may also be interested Essay Fixer

Works Cited

- Bachelard, G. (1994). The Poetics of Space. Beacon Press.

- Boyd, H. W., & Ray, M. J. (Eds.). (2019). Home and Identity in Late Life: International Perspectives. Policy Press.

- Casey, E. S. (2000). Remembering: A Phenomenological Study. Indiana University Press.

- Clark, C., & Murrell, S. A. (Eds.). (2008). Laughter, Pain, and Wonder: Shakespeare's Comedies and the Audience in the Playhouse. University of Delaware Press.

- Heidegger, M. (2010). Building, Dwelling, Thinking. In Poetry, Language, Thought (pp. 145-161). Harper Perennial Modern Classics.

- Kusenbach, M. (2003). Street Phenomenology: The Go-Along as Ethnographic Research Tool. Ethnography, 4(3), 455-485.

- Moore, L. J. (2000). Space, Text, and Gender: An Anthropological Study of the Marakwet of Kenya. Routledge.

- Rapport, N., & Dawson, A. (Eds.). (1998). Migrants of Identity: Perceptions of Home in a World of Movement. Berg Publishers.

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Basic Books.

- Seamon, D. (Ed.). (2015). Place Attachment and Phenomenology: The Synergistic Dynamism of Place. Routledge.

Video Version

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life Psychology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 830 words

3 pages / 1466 words

1 pages / 380 words

2 pages / 844 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on House

Home, sweet home. Each one of us has the place, which brings back good memories, is the symbol of comfort and wellness, revokes memories related to music, objects, colors, people, and dishes. This place is called home. It is [...]

"Cavity wall insulation is method used to reduce heat loss through the walls filling the air space with material that inhibits heat transfer. Cavity walls are constructed in houses. It is an outside wall and an [...]

Any house can be a home. To us, a house is a home that includes the pieces of community, family, memories, culture, and laughter. A home is a place where people help each other to overcome anxieties, find comfort through [...]

House could be a put where able to protect and it gives us a security from rain, warm storm, and more over to go. Everybody has their possess concept or choice on what sort of house they feel comfortable to live in for occasion [...]

This report investigates the current concept of home being used by different hotels to market their business. In the discussion, a business plan has been proposed to develop a new marketing style to promote the hotel business by [...]

There was this time when solar panels we meant only for buildings that provided for the energy consumption without having to borrow from power supply grids. The use of natural solar power to create energy is something that a lot [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Amazon bestsellers to upgrade your cleaning routine, bras and more — starting at $7

- TODAY Plaza

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Music Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

I’m going boysober for a month. Here’s what that means and why I’m doing it

I’m listening to my favorite podcast, “Savage Love,” as I churn the elliptical machine at my gym.

Exercise is an effort. I’ve just endured the first sexual encounter I’ve had since ending a long-term relationship six months ago, and I’m still shaken from the ick of it. As I try to redirect my angst into my workout, Dan Savage introduces his guest, comedian Hope Woodard, who’s created a stir by coining a new dating phenomenon: boysober.

My interest piqued, I up my pace and turn up the volume. Both my blood and my brain are pumped as I take in the idea.

What does 'boysober' mean?

Boysober is a yearlong decision to abstain from all-things dating as an act of self-care — including sex.

The conversation between Savage and Woodard is lively and meandering, so the exact definition of boysober is fuzzy. But what is clear: Boysober centers on women reclaiming autonomy over their bodies and reallocating their lost time, energy and mental space from dating into more meaningful pursuits. Of course, it’s not just cisgender women who can benefit from the boysober movement — Woodard has explained that the term is inclusive of people of any gender or sexual orientation.

A boysober year gives space to reflect, heal, and focus on what one wants next — from a relationship and for oneself. The movement began as a monthly comedy show in Brooklyn run by Woodard, and has expanded into a social media movement, especially among Gen Z women.

Woodard explained that while she consented to all the sex she’s had — a lot of it, according to her — she often said yes because she “was never really given the permission to say no.” Boysober is an antidote to the false narrative that it was her responsibility to validate men’s emotions, thoughts and feelings with sex.

“I’m a little bit angry at myself and angry at all the sex that I’ve had that I feel like I didn’t choose,” Woodard said in a New York Times interview .” For the first time ever, I just feel like I have ownership over my body.”

But don’t call it celibacy.

“I hate ‘celibacy’ so much, because I don’t want to give credence to anyone saying you’re more lovable or respectable or better if you’re not having sex,” Woodard said. “Boysober is about taking time to pause, reflect and reprioritize — not to gain male approval.”

Celibacy comes with religious overtones of purity culture, and it’s often involuntary. Boysober? That’s a choice.

And loads of women are choosing it.

Including me, sort of.

Why I’m going boysober

Boysober is a Gen Z’s version of sex positivity, and I’m here for it. Young women are looking up from lifetimes of unfulfilling sexual and romantic encounters, and they’re opting out.

But at 53 years old, the term itself feels … disingenuous for me. I choose man sober as my mission instead. I’ve lived through decades of dating norms, and that affords me a perspective I think these 20-something women still need to gain.

I remember that dating is supposed to be fun .

It hasn’t been, for them or me.

After coming out of a long-term relationship, I expected my re-entry into the world of dating would be bumpy. But I’ve been jostled so hard, I’ve lost my center of gravity, immersed in a landscape of dating vocabulary I never wanted to grasp. I’ve been love bombed , benched, breadcrumbed , ghosted , and given the ick , without knowing what many of these terms were until they happened.

Add to this mess a seemingly endless drone of “hellos” and “hi beautifuls” in my dating app inbox, and me spending thankless hours trying to find a semblance of spark within a miasma of men.

I became a dopamine addict, feral for the rush of another new message, only to be disappointed yet again. Most of my energy and focus got sucked into a dating vortex.

I wanted it to stop, but feared if I gave up, it might be for good. By my age, many women opt out, determining the proverbial juice isn’t worth the search for a squeeze. In my experience, one rarely meets a suitable suitor in the wild over 50. So it’s do the work, or resign oneself to never finding a partner.

I’m not handing in my resignation.

But a mansober month made it OK to take a break.

A month seemed sufficient to regain my sense of buoyancy, and shift focus back to the things that make me, me. I vowed to write, sing, organize, exercise, go to shows, read books, cook and spend time with friends. I’d pushed these pastimes aside in favor of endless swiping, countless lackluster conversations, and a few mostly miserable dating experiences.

March 1 rolled around and I joyously jumped back into myself.

How’s my mansober month going?

I’m three weeks into my mansober journey. No conclusions so far, but I do feel a clarity, and with it, a calmer heart and clearer headspace.

I feel more connected to my own desires and what I want from relationships. Woodward spoke of this sensation in her “Savage Love” interview, stating, “I’m really enjoying living with desire and not so quickly acting on it. Instead I’m asking, what does it look like, to let yourself think and desire and wonder?” Observing my own has helped me see how destabilizing it was to share desire with a partner who didn’t share my values.

And best of all, I’m having so much fun. My life is abuzz with activities. I’ve been to birthday parties, live shows, karaoke, a play, even a gala. I’ve been more present as a parent. I’ve mentored new writers. It’s been amazing. I still haven’t exercised much, though. Even this was illuminating; taking a mansober month clarified that I can’t blame everything on dating. I’m better at making time for things I want to do versus things I should do. That one’s on me.

Woodard concluded her "Savage Love" interview with a slightly paradoxical message: Unlike alcohol sobriety, boysober isn’t an absolute. “You’re not sober if someone is taking up your brain space,” she said. But she sees a distinction between “taking up brain space” and putting yourself out there and flirting. That’s because the goal isn’t to quit dating forever. It’s to discover how to show up best in the world, including as a romantic or sexual partner.

“I’m not so interested in cutting men or love completely out. I want to find a way to navigate it better,” she said.

Yes, this. It’s where I’m heading once my mansober month ends.

I’m not ready to jump back into dating apps, maybe ever. But I do think I’ll try new ways to meet men. I even signed up for a speed dating event on the day my sobriety ends. I nearly didn’t do it, because it seemed like jumping in too quickly. But I decided I should, as a show of optimism.

I still believe romantic love and partnership is out there for me.

Being mansober has given me the tools to seek it, without sacrificing the best parts of myself to the quest.

Dana DuBois is a GenX word nerd living in the Pacific Northwest who enjoys storytelling at the intersection of relationships, music, and parenting. She’s the founder and editor of Pink Hair & Pronouns , a pub for parents of gender-nonconforming kids, and Three Imaginary Girls , a music ‘zine. Em-dashes, Oxford commas, and well-placed semicolons make her heart happy. You can read her work on Medium and Substack .

I fell in love. Then I found out he was a celebrity

I went viral for being childless and happy at 37, and it was terrifying

I took my fiancé wedding dress shopping — and he hated everything

I asked my fiancé to surprise me with our honeymoon destination. Here's how it went

Divorce is having a moment. And I wish it had happened 10 years ago

A Black woman’s ode to nail art

What living in Singapore taught me about making friends as an adult

Relationships.

Bobbie Thomas opens up about experiencing her first breakup after her husband's death

We broke it off for years. Then we found each other again — and it’s true love

Pop culture.

People pay me to be a bridesmaid at their wedding — yes, really

You may opt out or contact us anytime.

Zócalo Podcasts

In Ukraine, No Election Doesn’t Mean the Electorate Is Happy

President zelensky is an international star. at home, it’s more complicated.

In wartime Ukraine, regular elections will not be held this year. Journalist Daria Badior reflects on the country’s recent political struggles and how Ukrainians can maintain democracy amid the ongoing war. People gathered at Maidan Nezalezhnosti (“Independence Square”) in Kyiv in 2013. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

by Daria Badior | March 25, 2024

Regular presidential elections should have taken place in Ukraine this month.

But on day one of Russia’s full-scale invasion of our country, Ukraine’s government introduced martial law, under which presidential, parliamentary, and local elections are all suspended. Instead of getting to vote, my peers and I are stuck with a president we did not vote for, but whose image has changed drastically since February 24, 2022.

Has Ukraine’s democracy become another victim of war?

Though our country’s democracy has roots dating back to practices instituted by the ancient Greeks who arrived to the territory of today’s Ukraine in the sixth century BCE, its modern instantiation of democratic rule is still in the making.

In May 2014, I stood in a queue outside a school in a post-industrial residential Kyiv neighborhood on the left bank of the Dnipro River . Inside were voting booths for the presidential election, which had been announced several months after the previous president fled the country. I remember the mood well: there was a consensus in the air that we needed to have a fast, transparent election.

The president who had fled, Viktor Yanukovych, had won office in a 2010 run-off election in which the opposition claimed there was systematic vote fraud. In office, Yanukovych had gone against the wish of most Ukrainians by declining to join the European Union. Instead, in 2013, he had announced intentions to join the Russia-backed Eurasian Economic Union. This would have made Ukraine economically dependent on its imperial neighbor.

In November 2013, hundreds of people, mostly students and activists, gathered at the Maidan Nezalezhnosti (“Independence Square”) in Kyiv to protest his decision. The protests swelled. On the last day of November, police brutally beat protestors, and the next day, even more people came to the square, turning it into a protest camp with stages, broadcasting facilites, first aid posts, and self-defense units. It was the largest amount of people to ever gather there. In February, when police attacked, violent clashes sparked and killed 100 protestors, known as the Heavenly Hundred.

Their actions made history. This was the Revolution of Dignity, the moment when Ukrainian society resolutely separated itself from Russia. The country wanted change. The elections that followed were supposed to provide it.

Though we are fans of fast political changes that resemble spectacular sprints, we’ve come to a moment at which we need to learn how to run a marathon.

Those elections resulted in the victory of Petro Poroshenko, an old-school politician- businessman. There was no runoff: He won the first round with more than 50% of the vote. This was the second time that this had happened. The first was in 1991, when Leonid Kravchuk got 61% at the elections held simultaneously with the referendum for Ukrainian independence. (90% of the populace voted in favor of independence.)

Thinking about 1991 and 2014, I ask myself: Do these decisive victories demonstrate that Ukrainian society has an ability to mobilize quickly again in times of radical transformation? Such major upheavals seem to happen here every 10 years—and we’re living in one now. What happens next? Can we keep hold of the democracy we’ve made?

Looking back to 2014 with hindsight, I can see that Poroshenko seemed to be the best-equipped candidate to lead the country: He was a diplomat by education, had experience in state finance and was a businessman, which meant—at that time—that he had a lot to lose . Russian troops were in the country then, as now. Crimea, as well as parts of Donetsk and Luhansk regions in the east of the country, were already occupied by Russia. And back then, many Ukrainians volunteered to go fight on the newly formed frontline.

In 2014, the starting war was a reason to hold elections. Sensing the upcoming turmoil, everyone wanted to at least secure the names of those who would govern the country in the near future. Parliamentary elections were held that year, too, and with them the process of government formation began. It was bumpy and imperfect, but fueled by an eagerness for a democratic transformation.

Ukrainian voters value the ability to bring about regular changes of power. Winning one election—even if, like Poroshenko, you win on a wave of post-revolutionary adrenaline—does not guarantee that you’ll remain in your comfy chair for longer than one term.

With Poroshenko, this was the case. In 2019, he lost by nearly a 50% margin to an ambitious, young candidate who had appeared straight from show business. You may know him: Volodymyr Zelensky.

The majority of my generational and political bubble, people between 30 and 40 years old who had devoted our most energetic years to secure post-Maidan transformations, did not vote for Zelensky. We took his promises to fight the corruption and nepotism of the country with skepticism. They mirrored too much his onscreen alter ego in the popular TV series Servant of the People , a history teacher who becomes president after a passionate anti-corruption rant that goes viral. Our universe of “highbrow” intellectual and political culture clashed with “lowbrow” TV that apparently had broken into the real world.

Under the banner of an ambitious effort for “efficiency,” Zelensky and the head of his administration gradually concentrated political power in the executive office even before the full-scale war started in 2022. Because the majority of seats in parliament are held by Zelensky’s party, Servant of the People (yes, it’s named after his TV show), his office had the backing to initiate a number of reforms, many of which were criticized by civil society institutions.

After Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine’s resistance catapulted Zelensky to heroism. He gained the stardom he had once wanted from show biz. It wasn’t undeserved: Skeptics from 2019, including me, were touched and proud on February 25, 2022, when he released a video from Bankova Street proving that he hadn’t left the country and was going to stay and fight.

But two years later, our adrenaline and feelings of pride have waned. Society needs more than just powerful speeches that finish with “Glory to Ukraine!” The dilemma that many journalists initially faced in 2022—whether or not to criticize the country’s governing figures in wartime—has been resolved, and not in the leaders’ favor. Journalists have brought back their anti-corruption investigations, while citizens are holding some civil demonstrations, even despite their prohibition under martial law.

Despite this, most Ukrainians don’t feel an urgent need to hold elections. In a country of 43 million, 6 million have fled the country, 4 million are internally displaced, and hundreds of thousands are serving in the army. Almost 20% of Ukrainian territory is currently occupied by Russia and significantly more is being constantly shelled. Elections, at least on the national level, don’t feel crucial at the moment.

With two revolutions in the last 20 years behind us, we are instead strengthening our skills of maintaining democracy by challenging our leaders. Though we are fans of fast political changes that resemble spectacular sprints, we’ve come to a moment at which we need to learn how to run a marathon.

What does that look like? This means fighting against unjust governmental decisions in courts, organizing advocacy campaigns for the rightful legislation, monitoring (via NGOs) all spheres of social and political life, and taking action when something is not right. It also means planning for the future by adopting the laws necessary to enter the European Union.

Our president may be an international star with multiple Time magazine covers, but he still must serve his people. We are not voting this spring, but we will not miss a chance to remind him of that.

Send A Letter To the Editors

Please tell us your thoughts. Include your name and daytime phone number, and a link to the article you’re responding to. We may edit your letter for length and clarity and publish it on our site.

(Optional) Attach an image to your letter. Jpeg, PNG or GIF accepted, 1MB maximum.

By continuing to use our website, you agree to our privacy and cookie policy . Zócalo wants to hear from you. Please take our survey !-->

Get More Zócalo

No paywall. No ads. No partisan hacks. Ideas journalism with a head and a heart.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Has Putin’s Invasion of Ukraine Improved His Standing in Russia?

By Joshua Yaffa

On its face, the reëlection of Vladimir Putin as Russia’s President seems a superfluous oddity, a ritual devoid of substance. Putin has ruled the country for nearly a quarter century, just a few years shy of Stalin’s epoch-spanning grip on the Soviet Union. No genuine opposition candidates have been allowed on the Presidential ballot in two decades. Since the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, in February, 2022, Putin’s authoritarian drift has accelerated into something resembling a full-blown military dictatorship. This February, the one credible outsider politician with a genuine, nationwide following, Alexei Navalny, died in a prison in the Russian Arctic.

Still, the latest election, which concludes on Sunday, provides an occasion to assess the state of Putin’s rule and how it has weathered two years of war. For much of its existence, the Putin system depended upon a disengaged citizenry. People stayed out of politics, and, unless you were one of the few people foolish enough to challenge the state directly, politics stayed out of your life. The war, in theory, could have been a pretext to galvanize Russian society. According to Western estimates, around three hundred and fifty thousand Russian troops have been killed or wounded in Ukraine. In September, 2022, Putin launched what he called “partial mobilization”—a military draft that, so far, has called up some three hundred thousand Russian men. Meanwhile, a series of repressive laws criminalized not only publicly criticizing the war but speaking truthfully about the invasion. Sanctions left the Russian economy isolated. In the wake of the invasion, the ruble crashed, inflation spiked, and real wages fell.

Yet, two years into the war, Russia’s position in Ukraine looks as advantageous as it’s ever been, and Putin’s hold on power feels, at least for the moment, entirely assured. A member of the country’s political élite told me that, during the Ukrainian Army’s counter-offensive last year, Putin was worried. “He couldn’t be sure that the front wouldn’t collapse like it did in the Kharkiv and Kherson regions,” the person said, referring to Ukraine’s retaking of its territory in the summer and early fall of 2022. But, in 2023, the Russian lines largely held, and Putin came to the conclusion that, given wobbly Western support, Ukraine was unlikely to achieve more on the battlefield in the near future. “He’s in a great mood,” the member of the élite said of Putin. “He’s waiting for the moment when the West says, ‘That’s enough, let’s stop this war,’ but he believes there’s no rush. Every month, the situation will get worse for Ukraine.”

In Russia, the shock of the invasion has long passed. Konstantin Remchukov, a newspaper publisher close to the Kremlin, told me that “there’s no more wavering” among the country’s ruling class: “Everyone understood it’s better to do as you’re told.” After the West sanctioned scores of prominent businessmen and severed economic ties with Russian companies, the country’s business élite saw their overseas prospects shrink, or disappear entirely. In Russia, however, the war effort created new money-making opportunities: assets as diverse as auto plants, formerly owned by Toyota and Renault, and Starbucks and IKEA franchises have been either seized outright or forcibly sold at steep discounts and parcelled out to loyal insiders. “Putin was clever,” one influential Russian businessman told me. “His message was, ‘See, they don’t accept you, but you’re welcome here.’ ” The businessman went on, “Many in my circle tell themselves, ‘If we’re going to be outcasts, better to be victorious outcasts than losers.’ ”

The response to the war among the Russian élite may not be all that remarkable—“This is not a very reflective class of people,” Remchukov said—but the evolution of the wider public’s attitude has been more complicated and surprising. A research project run by a group called the Public Sociology Laboratory has tracked public sentiment since the start of the war. One report asked respondents—educated, professional Russians from big cities—if they were troubled by the invasion. “I believed that we were making a terrible mistake, that we were evil,” a Russian I.T. specialist said, describing her emotions in the days after the war began. But, speaking eight months later, she said, “I see it as something inevitable, and very painful, a very difficult decision, but inevitable.” She justified Russia’s invasion as just the latest in a long line of human conflicts: “It turns out that there is always war, it always exists somewhere on the planet.”

A female business owner initially said that she tried to avoid news from Ukraine. “If I had the opportunity to somehow influence the situation, if something depended on me, of course I would do everything to stop it,” she said. “But tying yourself in knots, watching everything, discussing it with everyone—I don’t want to do that either. What’s the point? My duty is very simple—take care of myself, my family, and my close circle.” Half a year later, her views had hardened. “I get the feeling that my country is being unfairly bullied,” she said. “Now I am even more patriotic than ever.”

Russia’s G.D.P. grew more than the global average last year, even as an outsized portion of its economic activity was directed toward the war: in 2024, it is estimated that the state will spend more than eight per cent of its G.D.P. on the military and on national security, more than double the percentage of G.D.P. that the U.S. had allocated to defense during the Iraq War. At the same time, a bonanza of state spending has created a large-scale redistribution of resources which has strengthened Putin’s base of support among the poorer and more peripheral sectors of society. These groups have benefitted from populist measures, such as increased subsidies and other payments to families, and the expansion of wartime industry. In its dependence on state largesse, this rising middle class is distinct from the one that appeared during the past decade, which tended to be more educated, more urban, more likely to work in the private sector, and, it turned out, more mobile—its members were overrepresented among the hundreds of thousands of Russians who left the country after the invasion. (Putin may have had such a process in mind when, in March of 2022, he spoke of a “self-cleansing” of Russian society.)

For an upcoming paper, Alexandra Prokopenko, a former adviser to Russia’s Central Bank, calculated that, since the start of the war, the average monthly salary for a welder in a manufacturing plant has risen from twenty-five thousand rubles—around two hundred and seventy U.S. dollars—to a hundred thousand rubles today. Those working similar jobs in Russian-occupied Ukraine can earn three hundred thousand rubles a month. “These people have never seen such money in their lives,” Prokopenko told me. She added that the Kremlin can only afford to maintain such an economic policy for another year or so, at which point it will face some hard choices: will the state bring down wages for those in the military and the security services, or will it reduce shifts at factories that are working overtime to produce arms and equipment for the war? “That’s impossible to imagine politically,” Prokopenko told me. “But, in the long term, economic imbalances will only grow, as will the prospect of a real crisis.”

But for now, as Denis Volkov, the director of the Levada Center, an independent polling agency, told me, survey data suggest that Russians have a more positive outlook for their country than in any previous period of Putin’s Presidency. The share of Russians who report being able to make discretionary purchases, such as televisions and household appliances, is growing. The portion of respondents who think Russia’s economic prospects will continue to improve in the next five years has risen by some thirty-five percentage points since 2022. Even the number of those who said that the distribution of wealth has become more equitable rose by a record percentage. “If you look at the data,” Volkov said, “you’re left with the feeling that people believe they’ve never lived so well.”

The darker aspects of the war, including the deaths of tens of thousands of soldiers, are largely kept private, dealt with individually, out of the public sphere. The Kremlin has promised to send payments of five million rubles, around fifty-five thousand U.S. dollars, to the families of those killed in action—a significant sum, especially in the poorer regions from which most of Russia’s recruits are drawn. In a stage-managed meeting with mothers of Russian soldiers, Putin revealed his own attitude toward the country’s war dead. “Some people die of vodka, and their lives go unnoticed,” he told a woman whose son was killed in Luhansk. “But your son really lived and achieved his goal. He didn’t die in vain.”

Putin, for his part, sees himself not as an autocrat holding the country hostage but as a steward of Russia’s historical destiny. After decades in power, Putin’s logic functions as a tautology, a closed loop in which he never has to question or doubt the virtue of his political choices. As he sees it, he acts in the nation’s interests and therefore has the nation’s support; he has the right to rule however he wants because, in fact, he is serving and protecting the state. “Of course, that’s a very convenient position for Putin,” Abbas Gallyamov, a former speechwriter for Putin who is now a Putin critic, told me. “Seeing as that, by this point, he is the state.”

Still, in the past few months, Russia has seen two mass-scale, unscripted political events and, tellingly, neither was in support of Putin or the war. The first came in January, when lines of people spontaneously appeared across the country to provide their signatures in support of the candidacy of Boris Nadezhdin, a milquetoast, unthreatening, and unknown liberal politician. Nadezhdin made ending the “special military operation” the centerpiece of his campaign and called for freeing political prisoners. The Kremlin ultimately refused to put him on the Presidential ballot—a sign that it was rattled by images of people standing in the freezing cold to register their support for an alternative to Putin. According to reporting by Meduza, a Russian news outlet based abroad, internal Kremlin metrics forecast that Nadezhdin would have won as much as ten per cent of the vote. That would have clashed with Putin’s rhetoric of a unified country. A source close to the Kremlin told Meduza that such an outcome would “suddenly give the impression that a sizable share of the population is eager for the special military operation to end.”

The second event was Navalny’s funeral. Navalny was not necessarily popular in an electoral sense. His approval rating in Russia peaked at twenty per cent, in 2021, shortly after he was poisoned by Kremlin agents. But he had a powerful resonance in Russian society. With his plainspoken criticism of official corruption, his sense of humor, and his remarkable lack of fear, he became an avatar for an alternative, more optimistic future. He built a nationwide network of field offices and consistently drew thousands to protests across the country. “Autocracies like Russia’s don’t like the idea of progress,” Ekaterina Schulmann, a Russian political scientist based in Berlin, told me. “They are intently focussed on the past, maintain a cult of history, and use these ideas to try and keep the present forever.” Navalny represented the opposite, which made his existence unbearable to the state. “His entire stance centered on how tomorrow can be different from today if only we all follow some consistent action,” Schulmann said.

On March 1st, crowds lined a street in Moscow as the hearse carrying Navalny’s body drove past. Thousands more flocked to Borisovsky Cemetery, where they covered Navalny’s grave in a bulging mound of flowers. People chanted “Russia without Putin,” “No to war,” and even “Ukrainians are good people”—a remarkable display of civic courage given that, during the past two years, police have arrested people holding posters with asterisks in place of the words “No war,” and even those with blank posters with no words at all. Analysis of the Moscow metro system by Mediazona, an independent news site, showed a surge of twenty-seven thousand passengers to the station nearest to the cemetery. I spoke to a friend who had attended. “We hadn’t been among so many people who think like us in years,” the friend said. “The occasion was terrible, but the mood felt energized.”

The Russian investigative site Proekt, which the Russian state has labelled “undesirable,” recently tallied the number of people who have faced criminal prosecution in politically motivated cases in the course of Putin’s current six-year Presidential term. It was more than ten thousand, surpassing the comparable figures under the Soviet leaders Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev. “In addition to the widely discussed repression of oppositionists and anti-war activists, Russia has a system of social pressure where citizens are severely punished for the most insignificant misdemeanors,” the Proekt report said. Still, the current repressions are tough enough for everyone to get the message, but not so tough that they infringe on the public’s sense of normalcy. Aleksei Miniailo, an activist and co-founder of a sociological research project called Chronicles, who has chosen to remain in Moscow, told me, “If these were really Stalinist times, I would have been shot a year ago.” He went on, “This regime relies on one per cent repressions, ninety-nine per cent propaganda.”

One should not confuse the absence of dissent with heartfelt support. The Kremlin cannot fill stadiums with rabid, committed supporters. (It can bus them in or otherwise twist the arms of state employees, but genuine passion is exceedingly hard to muster.) Tatiana Stanovaya, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center, referenced Putin’s annual state-of-the-nation address from late February, during which he spoke of people who “send letters and parcels, warm clothes, and camouflage nets to the front; they donate money from their savings.” Putin, she said, needs to see the war not as something he alone launched—as is the case—but as an endeavor supported and demanded by the people. Stanovaya quoted the Soviet battle hymn, “Sacred War,” known for its opening line: “Arise great country!” But now, Stanovaya said, “The country doesn’t feel like rising.”

Last fall, in a moment of rare candor, Valery Fedorov, the head of a state-run polling agency, admitted that the so-called party of war—hawks who advocate for victory at any price—represents only ten to fifteen per cent of society. “The majority of Russians do not demand to take Kyiv or Odesa,” he said. “They don’t enjoy the fighting. If it were up to them, they would not have started a military operation, but since the situation has already developed this way, then we must win.” This is not quite opposition to the war, but it’s certainly something far less than enthusiasm for it.

Putin has largely accepted this reality. His government has set out to rewrite school history textbooks to portray Russia as perpetually defending itself against outside enemies and to link the war in Ukraine to the Soviet Union’s victory in the Second World War. Now Russian troops are fighting for “goodness and truth” just like their grandfathers. But, on the whole, as Volkov, of the Levada Center, put it, “The state lets people live as they want.” Putin has attempted to calm fears of another mass-mobilization order. “There is no such need,” he said last summer. If people are so moved, as he noted, to sew camouflage nets for the soldiers at the front, the state will celebrate their efforts. But if people want to busy themselves with children’s playgroups and Moscow restaurants—Remchukov, the newspaper publisher, spoke of new supply chains that provide exquisite crab legs and sea urchins from Murmansk, on the Barents Sea—that’s fine, too.

There is no great strategy or vision; unlike the ideology of the Soviet period, Putinism offers no sweeping values against which particular actions or policies can be measured. This fact, along with Putin’s disinterest in the nitty-gritty of governance, means there is ever more room for improvisation and freelancing at all levels of the state apparatus. Many high-profile arrests and criminal cases are launched without Putin’s direct awareness—the F.S.B. long ago received carte blanche to act as it pleases. Last fall, Putin ended up in a mildly awkward position when regional governments moved to restrict abortion rights and Putin, aware of the general discomfort in society with such restrictions, stepped in to block them.

But, when the system faces a real crisis, the state’s institutions and would-be protectors go silent. Such was the case, for example, last June, during the short-lived mutiny led by Yevgeny Prigozhin and his Wagner mercenaries. Many officials in regional government and the security services froze and watched as Prigozhin and his men sped toward Moscow. A similar dynamic played out last October, when an antisemitic mob ran wild through an airport in Dagestan, and it took hours to chase them off the tarmac. In such situations, no one wants to claim responsibility or rush to the regime’s defense. “How can you claim to have total control,” the member of the élite said, “and yet look so powerless.”

To the extent that wartime Putinism has an identifiable doctrine, it’s that Russia is engaged in a protracted struggle with the West. In Putin’s address in February, he said, “The so-called West, with its colonial practices and penchant for inciting ethnic conflicts around the world, not only seeks to impede our progress but also envisions a Russia that is a dependent, declining, and dying space where they can do as they please.” Remchukov told me, “He’s made up his mind. If earlier on in the conflict there were different scenarios and time lines for how things might be resolved, now we see a qualitative change: he’s decided the confrontation between Russia and the West is here for a while—several decades at least.” Now, Remchukov went on, the state has to explain to the public the ways in which Russia is not the West, thus the emphasis on traditional values and Putin’s increasing interest in culture-war topics such as gay marriage and trans rights.

Schulmann, the political scientist, told me, “We see a picture of the world in which the West hates Russia and always attacks it because their values are incompatible.” She went on, “And those values are innate and unchanging. The West will never stop attacking. Russia will never be defeated. Confrontation is eternal.” Conveniently for Putin, unlike a “special military operation,” this kind of struggle has no end. It continues forever, meaning his rule must, too.

Putin will surely be inaugurated for a fifth term in the spring. But is he popular? And does it even matter? Recent Levada Center polling shows his approval rating is above eighty per cent. But Miniailo, of the Chronicles project, cautioned against taking such figures too seriously. “It makes little sense to try to understand what people want solely by asking which candidate they will vote for,” he said. “Politics simply doesn’t exist in Russia, so this question has little relevance.”

Miniailo relayed the results of a recent survey that his group conducted which showed a growing disparity between which policies people would like to see (more spending on social programs) and which policies they expect Putin to enact (more spending on the military). The same was true for the question of reaching a truce with Ukraine, for example, or restoring relations with the West; some twenty per cent more respondents favor these policies for Russia’s future than expect Putin to carry them out. For now, these data suggest only a latent, passive dissatisfaction that may or may not turn into something larger.

The continued stability of Putin’s rule rests not on his popularity but, rather, on the lack of mechanisms people have to act on their malaise, discontent, and frustrations. In the past two decades, the Kremlin has dismantled those instruments: there is no longer a muckraking independent media to hold the state accountable; there are no credible opposition parties to channel dissatisfaction into real politics; and there is no judicial system capable of acting as a check on power. And, so, if feelings of resistance have no credible outlet, then the feelings themselves are repressed. “I always hear at my talks in the West: if people aren’t happy, then there should be crowds in the streets,” Greg Yudin, a Russian political philosopher at Princeton, told me. “But what are these crowds going to do?”

Yudin mentioned Navalny’s funeral and the crowds that keep coming, day after day, to lay flowers. “Of course, in a country of a hundred and forty million there are plenty of brave people,” he said. “But that was never the problem. The more relevant point is that it’s entirely unclear what to do with this bravery, where to direct it, and for what end.” People are neither foolish nor suicidal, he noted; moreover, this is not an exclusively Russian condition.

The future of the Putin system, then, in large measure depends on the appearance—or continued absence—of instruments or avenues to challenge it in any meaningful way. “It’s not that you change your attitude and then take action,” Yudin said. “If you see an opportunity for action, then you might rethink your attitude.” Yudin and I discussed the idea, widely accepted by most Russian sociologists and political scientists, that the Russian public would react with relief, even joy, if Putin declared tomorrow that he was ending the war. (The member of the élite noted that Putin could do so rather easily: “He will say we gained four new territories, secured a land bridge to Crimea, and defeated NATO . It’s easy to sell.”) But if Putin were to appear on television to announce, say, that the West left him no choice but to launch nuclear warheads aimed at Washington, London, and Berlin, “People would also take this in stride,” Yudin said. A CNN report revealed that, in the summer of 2022, the Biden Administration was “preparing rigorously” for a Russian nuclear strike in Ukraine.