Responsible Consumption and Production Essay

Consumption and production worldwide are the driving force of the global economy. However, this process is based on using the natural environment and resources and still has a devastating impact on the planet. The socio-economic progress achieved over the past century has been accompanied by environmental degradation, which threatens the very systems on which our future development depends and, in fact, our very survival. Consumption and production are also aimed at overcoming the direct relationship between economic growth and environmental degradation, increasing resource use efficiency.

Encouraging industries, enterprises, and consumers to implement recycling and waste reduction and the principles of a cyclical economy is one of the main necessary changes that can have a significant impact on society as a whole. The number of people in the world belonging to the middle class is expected to grow over the next two decades. This situation is favorable for the prosperity of individuals, but it will lead to an increase in demand for already limited natural resources. There are several aspects of consumption whose simple changes can significantly impact society as a whole. For example, every year, about a third of all food produced, which amounts to 1.3 billion tons’ worth about $1 trillion, ends up in garbage containers of consumers and shops or spoils due to poorly organized harvesting (Tseng et al., 2018). Therefore, the situation must change before it leads to more disastrous consequences.

Rebuilding a business in accordance with the concept of sustainable development and making a profit from it is a feasible task, says Senior Vice President, Director of Environmental Affairs at Schneider Electric (provides digital solutions in the field of power management and automation) Xavier Wo. In his opinion, ambitious goals to combat climate change contribute to the innovative development of the company itself, as well as its suppliers and customers (Robert et al., 2020). According to the head of the company, with the help of reasonable consumption, it is possible to extend the life of products up to 10-15 years. Consequently, in business, this approach has a considerable number of advantages

Socio-economic inequality is an uneven distribution of income and opportunities between different groups of society. However, the principle of reasonable consumption can reduce social inequality and poverty. With the help of moderate consumption and processing of goods, their prices are significantly reduced. Such goods will be beneficial to families living below the poverty line. Therefore, sustainable consumption and production can make a significant contribution to poverty reduction.

In conclusion, sustainable consumption and production aim to “do more and better with less,” increasing the net benefits of economic activity to maintain a level of well-being by reducing resource use, reducing degradation and pollution. The idea of responsible consumption is that consumers will create demand for more “green” alternatives in different industries, thereby provoking the development of new solutions and the gradual replacement of goods on the market. Thus, the implementation of the responsible consumption program helps to fulfill overall development plans, reduce future economic, environmental, and social costs, increase economic competitiveness and reduce poverty.

Works Cited

Robert, Marc, Philippe Giuliani, and Calin Gurau. “Implementing industry 4.0 real-time performance management systems: the case of Schneider Electric.” Production Planning & Control (2020): 1-17.

Tseng, Ming-Lang, et al. “Responsible consumption and production (RCP) in corporate decision-making models using soft computation.” Industrial Management & Data Systems (2018).

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, November 9). Responsible Consumption and Production. https://ivypanda.com/essays/responsible-consumption-and-production/

"Responsible Consumption and Production." IvyPanda , 9 Nov. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/responsible-consumption-and-production/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Responsible Consumption and Production'. 9 November.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Responsible Consumption and Production." November 9, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/responsible-consumption-and-production/.

1. IvyPanda . "Responsible Consumption and Production." November 9, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/responsible-consumption-and-production/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Responsible Consumption and Production." November 9, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/responsible-consumption-and-production/.

- Soil Degradation as an Issue Facing Agriculture

- Environmental Degradation Impacts of Concrete Use in Construction

- Marine Degradation and Solutions in the Pacific Region

- Much Lighter: Talking to Andrew McAfee

- How COVID-19 Is Changing Business Processes

- Gas Prices in the United States: Supply and Demand

- This American Life Episode: “Giant Pool of Money”

- Health Sector Reversal Strategies

Responsible consumption & production

Responsible use of natural resources: essential for sustainable growth.

[goal: 12] calls for the sustainable production and consumption of goods and services. Countries have demonstrated it’s possible to achieve economic growth without depleting natural resources: on average, countries have increased their natural capital by 26.8 percent since the mid-1990s. Yet, for many countries, growth continues to come at the expense of natural resources.

↓ Read the full story

Unsustainable production

Sustainable production, many countries have grown unsustainably, growth in natural capital per capita and gdp per capita (%), 1996-2018.

Source: [link: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/changing-wealth-of-nations World Bank (2021)].

How governments, the private sector, and citizens can increase sustainability

In the SDG framework, [emphasis: the responsibility] to ensure sustainable production and consumption patterns is shared by governments, the private sector, and citizens.

Actions by governments

Most countries subsidize fossil-fuel industries, fossil-fuel subsidies as a share of gdp (%).

Source: [link: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/dataportal Global SDG Indicators Data Platform].

Actions by the private sector

Sdg indicators explicitly targeted the private sector, companies in low- and lower middle-income countries rarely publish sustainability reports, number of sustainability reports registered, actions by private citizens, wealthier regions lose more food in the consumption stage, share of food lost in consumption stage (%).

Source: [link: https://www.wri.org/research/reducing-food-loss-and-waste-setting-global-action-agenda Flanagan et al. (2019).]

Learn more about SDG 12

In the charts below you can find more facts about SDG {activeGoal} targets, which are not covered in this story. The data for these graphics is derived from official UN data sources.

SDG target 12.3

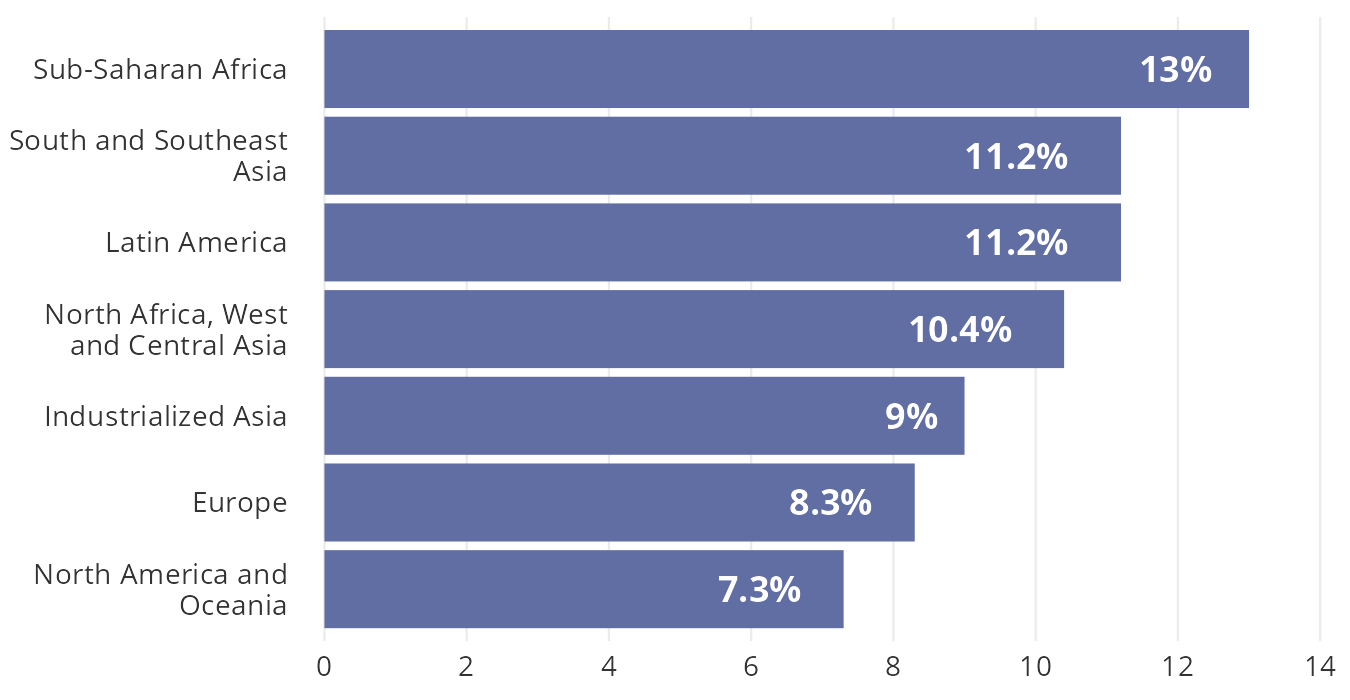

In sub-Saharan Africa, 13% of food loss and waste happen in production stage.

Share of food lost in production stage (%).

Source: Flanagan, Katie, K. A. I. Robertson, and Craig Hanson. 2019. "Reducing food loss and waste: Setting a Global Action Agenda." World Resource Institute, Washington DC. DOWNLOAD

SDG target 12.5

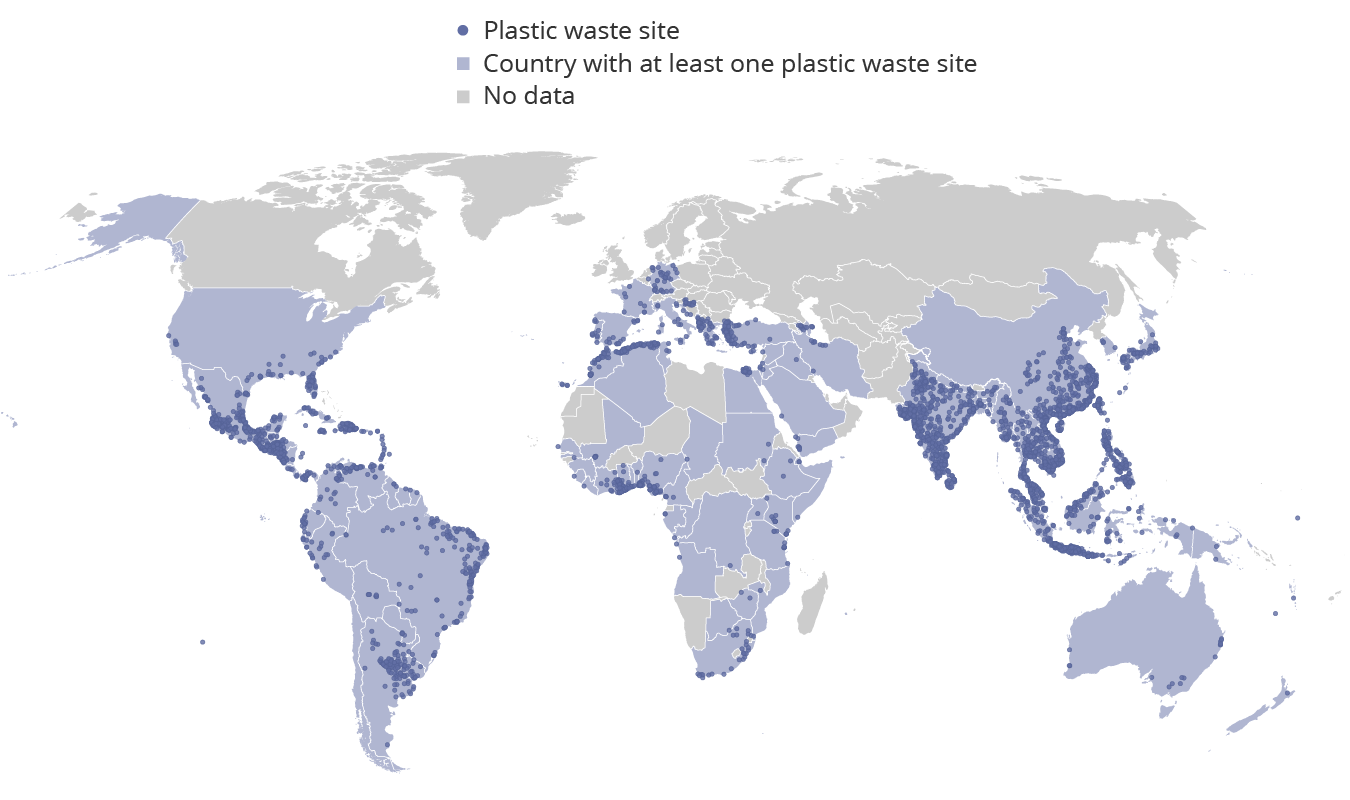

Most identified plastic waste sites are in South and East Asia

Plastic waste sites identified..

Source: Minderoo Foundation, [link: https://dev.plastic.watch.earthrise.media/faqs Global Plastic Watch], electronic dataset access date: February, 2023. DOWNLOAD

Sustainable Development Goal 12

Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns.

Sustainable Development Goal 12 is to “ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns”, according to the United Nations.

The visualizations and data below present the global perspective on where the world stands today and how it has changed over time.

The UN has defined 11 targets and 13 indicators for SDG 12. Targets specify the goals and indicators represent the metrics by which the world aims to track whether these targets are achieved. Below we quote the original text of all targets and show the data on the agreed indicators.

Target 12.1 Implement the 10-year sustainable consumption and production framework

Sdg indicator 12.1.1 sustainable consumption and production action plans.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 12.1.1 is the “number of countries developing, adopting, or implementing policy instruments aimed at supporting the shift to sustainable consumption and production” in the UN SDG framework .

The UN defines sustainable production and consumption as: “the use of services and related products, which respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life while minimising the use of natural resources and toxic materials as well as the emissions of waste and pollutants over the life cycle of the service or product so as not to jeopardise the needs of future generation.”

This does not measure the quality or ambition of these plans, only whether a country has one.

Data for this indicator is shown in the interactive visualization.

Target: “Implement the 10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns” with all countries taking action by 2030. 1

Target 12.2 Sustainable management and use of natural resources

Sdg indicator 12.2.1 material footprint.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 12.2.1 is “material footprint, material footprint per capita, and material footprint per GDP” in the UN SDG framework .

Material Footprint (MF) is the attribution of global material extraction to domestic final demand of a country. The total material footprint is the sum of the weight of the used biomass, fossil fuels, metal ores and non-metal ores.

It is measured on the basis of consumption , which means that it is a country’s domestic material footprint adjusted for trade.

Data on this indicator for material footprint per capita and per unit of GDP is shown in the interactive visualizations. This is currently only available as global estimates.

Target: “By 2030, achieve the sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources.”

SDG Indicator 12.2.2 Domestic material consumption

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 12.2.2 is “domestic material consumption, domestic material consumption per capita, and domestic material consumption per GDP” in the UN SDG framework .

Domestic Material Consumption measures the total amount of material directly used in an economy. It measures material production , rather than consumption because it is not adjusted for trade.

“Materials” include biomass, fossil fuels, metal ores and non-metallic minerals.

Data on this indicator for domestic material consumption per capita and per unit of GDP is shown in the interactive visualizations.

Target 12.3 Halve global per capita food waste

Sdg indicator 12.3.1 global food loss.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 12.3.1 is the “(a) global food loss index and (b) food waste index” in the UN SDG framework .

The ‘Food Loss Index’ measures how losses in the food supply chain have changed relative to 2015.

Food ‘losses’ are defined as the loss or wastage of food from the farm up to the retail level. Pre-harvest losses, and retail and consumer waste are not included.

Data for this metric is shown in the interactive visualization.

Target: By 2030 “halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses.”

Target 12.4 Responsible management of chemicals and waste

Sdg indicator 12.4.1 international agreements on hazardous waste.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 12.4.1 is the “number of parties to international multilateral environmental agreements on hazardous waste, and other chemicals that meet their commitments and obligations in transmitting information as required by each relevant agreement” in the UN SDG framework .

There are a number of international multilateral agreements on hazardous waste and other chemicals (including the Montreal Protocol, Basel Convention, Rotterdam Convention and Stockholm Convention).

This metric shows the share of required information that has been submitted to international organizations as part of each agreement.

Target: “Achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes throughout their life cycle, in accordance with agreed international frameworks” by 2020. 2

Unlike most SDG targets which are set for the year 2030, this indicator is set for 2020.

SDG Indicator 12.4.2 Hazardous waste generation

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 12.4.2 is “(a) hazardous waste generated per capita; and (b) proportion of hazardous waste treated, by type of treatment” in the UN SDG framework .

Hazardous waste is defined as waste that is harmful to human health, or the environment. This indicator captures how much hazardous waste is generated, and how it is treated or disposed of.

Target 12.5 Substantially reduce waste generation

Sdg indicator 12.5.1 recycling rates.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 12.5.1 is the “national recycling rate, tons of material recycled” in the UN SDG framework .

This includes various types of material recycling such as municipal (household) waste and electronic waste.

Limited data is available for recycling rates globally.

The first visualization shows the total quantity of municipal waste – that is, waste from households and businesses, that would be collected by local authorities – that is recycled.

The second visualization shows the percentage of electronic waste that is recycled in each region.

Target: “By 2030, substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse.”

Target 12.6 Encourage companies to adopt sustainable practices and sustainability reporting

Sdg indicator 12.6.1 companies publishing sustainability reports.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 12.6.1 is the “number of companies publishing sustainability reports” in the UN SDG framework .

These metrics are split by the number of countries that meet the minimum requirements for reporting, at least.

Target: “Encourage companies, especially large and transnational companies, to adopt sustainable practices and to integrate sustainability information into their reporting cycle” by 2030.

Target 12.7 Promote sustainable public procurement practices

Sdg indicator 12.7.1 national sustainable procurement plans.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 12.7.1 is the “number of countries implementing sustainable public procurement policies and action plans” in the UN SDG framework .

Data on this indicator is shown in the interactive visualization.

Target: “Promote public procurement practices that are sustainable, in accordance with national policies and priorities” by 2030.

Target 12.8 Promote universal understanding of sustainable lifestyles

Sdg indicator 12.8.1 understanding of sustainable lifestyles.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 12.8.1 is the “extent to which (i) global citizenship education and (ii) education for sustainable development are mainstreamed in (a) national education policies; (b) curricula; (c) teacher education; and (d) student assessment” in the UN SDG framework .

Data for this indicator is shown in the interactive visualizations.

Target: “Ensure that people everywhere have the relevant information and awareness for sustainable development and lifestyles in harmony with nature” by 2030.

Target 12.a Support developing countries' scientific and technological capacity for sustainable consumption and production

Sdg indicator 12.a.1 support for developing countries' capacity for sustainable production.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 12.a.1 is the “installed renewable energy-generating capacity in developing countries (in watts per capita)” in the UN SDG framework .

Renewable energy is defined as hydropower; marine (ocean, tidal and wave); wind; solar (photovoltaic and thermal energy); bioenergy; and geothermal energy.

Target: “Support developing countries to strengthen their scientific and technological capacity to move towards more sustainable patterns of consumption and production” through 2030.

Target 12.b Develop and implement tools to monitor sustainable tourism

Sdg indicator 12.b.1 monitoring sustainable tourism.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 12.b.1 is the “implementation of standard accounting tools to monitor the economic and environmental aspects of tourism sustainability” in the UN SDG framework .

Target: By 2030 “Develop and implement tools to monitor sustainable development impacts for sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products.”

Target 12.c Remove market distortions that encourage wasteful consumption

Sdg indicator 12.c.1 removing fossil fuel subsidies.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 12.c.1 is the “Amount of fossil-fuel subsidies (production and consumption) per unit of GDP” in the UN SDG framework .

This includes pre-tax subsidies for both production and consumption of fossil fuels, as a share of total gross domestic product. Production subsidies reduce the cost of producing coal, oil or gas. Consumption subsidies cut fuel prices for the end user, such as by fixing the price at the petrol pump so that it is less than the market rate.

Target: By 2030 “rationalize inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption by removing market distortions, in accordance with national circumstances, including by restructuring taxation and phasing out those harmful subsidies, where they exist, to reflect their environmental impacts, taking fully into account the specific needs and conditions of developing countries and minimizing the possible adverse impacts on their development in a manner that protects the poor and the affected communities.”

Full text: “Implement the 10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns, all countries taking action, with developed countries taking the lead, taking into account the development and capabilities of developing countries.”

Full text: “By 2020, achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes throughout their life cycle, in accordance with agreed international frameworks, and significantly reduce their release to air, water and soil in order to minimize their adverse impacts on human health and the environment.”

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

BibTeX citation

Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license . You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

Introductory essay

Written by the educators who created Reworking the Western Diet, a brief look at the key facts, tough questions and big ideas in their field. Begin this TED Study with a fascinating read that gives context and clarity to the material.

Sweet and salty, meaty and mega-sized: Introducing the Western diet

If you live in a Western culture, chances are good that your food is quite different from anything your forebears put on a dinner plate. Thanks to the industrialization of food production and procurement, citizens of Western societies (and the affluent members of developing nations) are shopping for, cooking and consuming a seemingly endless supply of relatively inexpensive, high-calorie, highly processed food.

What are the staples in this stream of plenty? Westerners are eating enormous quantities of sugar, beef, chicken, wheat and dairy products, and washing it all down with an amazing array of caffeinated and alcoholic beverages. Americans in particular consume over twice the amount of solid fats and added sugars recommended for daily intake, and they consume far fewer fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains than those who lived in earlier eras — and less than experts recommend for optimal health.

Because of its ubiquity, this particular approach to eating has been dubbed the Western Diet — or, as it's known in some circles, the Standard American Diet, with its condemnatory acronym, S.A.D. And increasingly, it's coming under fire for how it's affecting human health, community life, and the environment.

Check, please: Calculating the costs of our food choices

Although the industrialized food system eliminated historical patterns of frequent food shortages, its ultimate legacy may be a toxic food environment that's degrading the health of people and the planet. Industrialized agriculture and the government policies that encouraged the mass production of food were intended to facilitate better overall nutrition and health around the globe, but they've also encouraged excess and — ironically — poor health in many societies.

We've become particularly adept at producing huge amounts of food, and those of us in Western cultures eat a lot more of it than we used to. The result: A range of troubling health concerns sweeping America and other countries that adopt the American diet. Chief among these, as chef and TED speaker Ann Cooper observes, is the startling rise in diabetes, especially among children.

Yet, as food scholars Chris Otter and Raj Patel have pointed out, a serious paradox exists in today's world: while approximately 1.6 billion people are suffering from conditions resulting from too much food (obesity, diabetes, atherosclerosis), another billion are suffering from conditions resulting from not enough food (hunger, malnutrition, vitamin deficiency diseases).(i) For these people, food is too expensive, too scarce, or the supply too erratic because of government greed or warfare which prevents equitable distribution. Most of the "stuffed" reside in Global North, while most of the "starved" dwell in the Global South. The financial crisis of the last decade, coupled with skyrocketing oil prices, created in some countries severe food shortages that led to riots.

We must reckon with the reality of finite resources, including the water, oil, and arable land that have driven the modern agricultural revolution. Paul Roberts, in his ominously titled book The End of Food , focuses on the degradation of resources and the devastating damage that results from industrialized farming, especially from livestock operations. Because meat figures so prominently in the Western diet, our "ecological footprint" exceeds by a quarter the planet's biocapacity. Additionally, as journalist Graham Hill describes in his TEDTalk, meat production is a significant driver of climate change.

On top of these thorny environmental, political, humanitarian and health-related problems, there's also evidence that our diet may be damaging the basic social fabric of our communities. The rise of fast food, combined with other social and cultural phenomena (from the rise of more single-parent and two-income families, to the creation of cars with built-in cup holders and food trays) have led to changes in how we eat as families. And many observers see this as damaging to family life and even civil society.

How did we get here, anyway? Feeding an army

In a number of important ways, the modern-day Western diet owes its existence to World War II, which changed the way we produce, prepare, and market food. Doing their part for the war effort, North American farmers delivered record-breaking crop yields, in some measure due to their liberal use of manufactured fertilizers and pesticides (including the new miracle insect killer, DDT). After the war the farmers escalated their use of these chemicals; this, combined with increasingly sophisticated farm equipment and hybrid seed engineering, led to even greater production, much of which was subsidized by long-held government parity agreements.

During the post-war era, the farmers, government officials and agricultural scientists hoped that this increased food production would help meet the needs of a rapidly growing global population. Rockefeller Foundation scientists engineered new seeds designed to produce significantly more grain in countries all over the world, and in doing so ushered in a "Green Revolution." The Green Revolution seemed to work miracles, vastly increasing the amount of food available to people in developing countries. However, it also put a severe strain on local economies, endangered subsistence farmers and indigenous cultures, and accelerated the advance toward large, corporate-type style farming in the United States and elsewhere.

Just as World War II was a watershed era in food production, it also ushered in significant changes in food processing. Military quartermaster departments pounded, dried, stretched and shrunk food in every imaginable way in order to reduce bulk and weight to ship it overseas efficiently and in large quantities. Frozen orange juice, instant coffee and potatoes, powdered eggs and milk, ready-trimmed and packaged meats, and even the ubiquitous TV dinner all either got their start or were perfected with wartime research and technology.

After the war, manufacturers quickly adapted and began producing foods for household consumers. Advertisers and enthusiastic journalists deemed the new preservation techniques "a modern miracle in the kitchen." Marketers and manufacturers were so successful in their efforts that eventually "high quality food" became synonymous with a long shelf life and low spoilage. Subtly at first, and more dramatically later, there occurred a shift in the traditional, seasonal approach to eating in developed countries.

Drive-thru dining: Fast foods and convenience marts

At the same time that home cooking was changing, a new type of restaurant revolutionized the way that Westerners dined out. New chain restaurants like McDonald's and Carl's Jr. could accomplish what locally- and individually-owned operations had difficulty doing: providing food fast and cheap. Emphasis on economies of scale — purchasing large quantities of supplies and preparing the food in a centralized kitchen to be warmed and assembled at the chain — enabled "fast food," even as such cost- and time-saving techniques lessened the food's quality and nutritional value.

The fast food pioneers standardized a "fast food taste" that endures today: soft white buns, flat hamburger patties, milkshakes made with increasingly less milk and more added preservatives, prepared in exactly the same way at every location in the chain to appeal to the broadest customer base possible. This formula proved successful, and fast food restaurants gained an enormous following, becoming to many a beloved, permanent fixture in mainstream culture. Convenience became the watchword: convenience allowed speedy delivery, which led to speedy consumption.

By the 1960s, industrially produced American "fast food" franchises appeared around the globe. While some countries, particularly in Asia, adopted and absorbed the basic concept and menu onto their gustatory landscape, others, especially in Europe, protested it as an affront to national culture and cuisine.

A healthier way: The search for alternatives

During the last few decades, we've witnessed an emerging food "revolution" that has attempted to counter, or at least moderate, the worst aspects of the industrialization of food. Those involved in the food movement aim to demonstrate the connection between good food and sustainable agricultural practices, and to create better-tasting, higher-quality food for restaurants and consumption at home.

Since the late 1990s, scholarly attention to food matters has deepened as the academic field of food studies came into its own. Public and political scrutiny of the Western diet has been fueled by popular books by Eric Schlosser ( Fast Food Nation ), Marion Nestle ( Food Politics and Safe Food ), and Michael Pollan ( The Omnivore's Dilemma ), as well as films such as Supersize Me , Food, Inc , and King Corn , which have exposed the questionable practices of the food industry and the government's willingness to accommodate food-industry demands. The list is long, and the titles themselves revealing, including: Food, Inc. : Mendel to Monsanto—The Promises and Perils of the Biotech Harvest (Peter Pringle), The End of Food (Paul Roberts), and The End of Overeating: Taking Control of the Insatiable American Appetite (David Kessler).

Taken together, these works draw our attention to deep problems in the global food supply, problems ranging from health and nutrition, to economics and environment, to corporate control of food production and advertising, to the peril of people and the planet. What emerges is the realization that seemingly disparate and unrelated topics (obesity, environment, flavor, family meals, hunger) are indeed interconnected.

In light of these interconnections, it makes sense that food issues figure prominently in our modern public discourse, and that many are calling for a return to more humane, more harmonious methods of growing, cooking, and eating.

In some sense, this is old news: thinkers from Thomas Jefferson to Wendell Berry have been extolling a closer connection to agriculture for centuries. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many people felt alienated by modernism and the industrialization that severed the connection between producer and consumer, an alienation that is still palpable in our relationship to mass-produced, industrial food. For some people, preparing meals from scratch for one's family, using ingredients bought at a local farmer's market, signifies self-reliance, a sense of simplicity, and a voluntary disconnect from the fast pace of our postindustrial, digital era. It can also result in less wastefulness.

Many producers and sellers of food items capitalize on and cater to this alternative vision of food. Indeed, marketers have learned that while the new food culture may not appeal to everybody, it does appeal to a sizable, influential minority. Within this target audience, however, there's considerable disagreement about what exactly constitutes the healthiest, most sustainable approach to food production and consumption: Organic? Locally grown? Vegetarian? Responsibly raised? Grow-your-own? Even this terminology is hotly contested, as food writer and TED speaker Mark Bittman demonstrates:

Let me pose you a question. Can farm-raised salmon be organic, when its feed has nothing to do with its natural diet, even if the feed itself is supposedly organic, and the fish themselves are packed tightly in pens, swimming in their own filth? And if that salmon's from Chile, and it's killed down there and then flown 5,000 miles, whatever, dumping how much carbon into the atmosphere? I don't know. Packed in Styrofoam, of course, before landing somewhere in the United States, and then being trucked a few hundred more miles. This may be organic in letter, but it's surely not organic in spirit.

Other critics of the Western diet like activist and TED speaker Ron Finley have little patience for what they consider 'elitist' debates about the relative merits of locally-grown or organic goods; for them, healthy food is about social justice. They point out that many people can't even access affordable, conventionally-grown fresh fruits, vegetables and proteins at food stores or markets in their communities. Those who live in these "food deserts" must rely heavily on fast food restaurants and convenience stores, and often suffer a higher rate of diabetes, obesity and other food-related health problems as a result.

The TED speakers featured in Reworking the Western Diet tackle the topic from different angles, occasionally contradictory — but all can agree with Mark Bittman when he says, "Now here is where we all meet. The locavores, the organivores, the vegetarians, the vegans, the gourmets and those of us who are just plain interested in good food. Even though we've all come to this from different points, we all have to act on our knowledge to change the way that everyone thinks about food. We need to start acting. And this is not only an issue of social justice...but it's also one of global survival."

Let's begin with Carolyn Steel, who sets the stage by demonstrating the symbiotic relationship between food procurement and the development of cities throughout history. How should we feed an increasingly urban global population? Steel argues that the answer lies not in our modern, unsustainable food system, but in reworking communities so that food can, once again, become part of the social core of a city.

Carolyn Steel

How food shapes our cities.

i. See Otter, C. (2010). Feast and famine: The global food crisis. Origins, 3(6), 1-6, and Patel, R. (2009). Stuffed and Starved: The Hidden Battle for the World Food System New York: Melville House Publishing. http://origins.osu.edu/article/feast-and-famine-global-food-crisis https://itunes.apple.com/us/book/stuffed-and-starved/id466320253?mt=11

Relevant talks

Britta Riley

A garden in my apartment.

A guerrilla gardener in South Central LA

What's wrong with school lunches

Mark Bittman

What's wrong with what we eat.

Graham Hill

Why i'm a weekday vegetarian.

A foie gras parable

Marcel Dicke

Why not eat insects.

Goal 12: Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns

Goal 12 is about ensuring sustainable consumption and production patterns, which is key to sustain the livelihoods of current and future generations.

Our planet is running out of resources, but populations are continuing to grow. If the global population reaches 9.8 billion by 2050, the equivalent of almost three planets will be required to provide the natural resources needed to sustain current lifestyles.

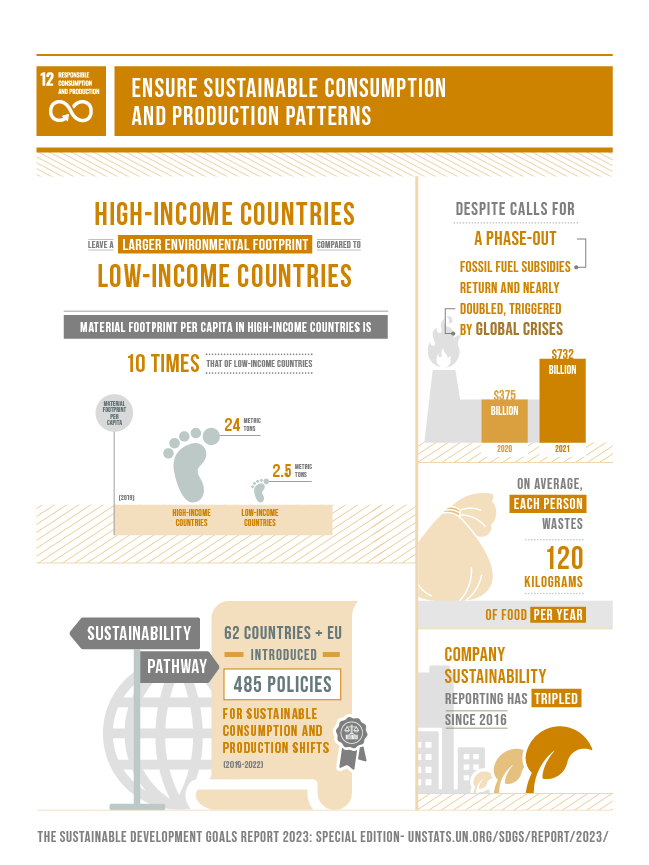

We need to change our consumption habits, and shifting our energy supplies to more sustainable ones are one of the main changes we must make if we are going to reduce our consumption levels. However, global crises triggered a resurgence in fossil fuel subsidies, nearly doubling from 2020 to 2021.

We are seeing promising changes in industries, including the trend towards sustainability reporting being on the rise, almost tripling the amount of published sustainability over just a few years, showing increased levels of commitment and awareness that sustainability should be at the core of business practices.

Food waste is another sign of over consumption, and tackling food loss is urgent and requires dedicated policies, informed by data, as well as investments in technologies, infrastructure, education and monitoring. A staggering 931 million tons of food is wasted a year, despite a huge number of the global population going hungry.

Why do we need to change the way we consume?

Economic and social progress over the last century has been accompanied by environmental degradation that is endangering the very systems on which our future development and very survival depend.

A successful transition will mean improvements in resource efficiency, consideration of the entire life cycle of economic activities, and active engagement in multilateral environmental agreements.

What needs to change?

There are many aspects of consumption that with simple changes can have a big impact on society as a whole.

Governments need to implement and enforce policies and regulations that include measures such as setting targets for reducing waste generation, promoting circular economy practices, and supporting sustainable procurement policies

Transitioning to a circular economy involves designing products for longevity, repairability, and recyclability. It also involves promoting practices such as reusing, refurbishing, and recycling products to minimize waste and resource depletion.

Individuals can also adopt more sustainable lifestyles – this can involve consuming less, choosing products with lower environmental impacts, and reducing the carbon footprint of day-to-day activities.

How can I help as a business?

It’s in businesses’ interest to find new solutions that enable sustainable consumption and production patterns. A better understanding of environmental and social impacts of products and services is needed, both of product life cycles and how these are affected by use within lifestyles.

Innovation and design solutions can both enable and inspire individuals to lead more sustainable lifestyles, reducing impacts and improving well-being.

How can I help as a consumer?

There are two main ways to help:

- Reducing your waste and

- Being thoughtful about what you buy and choosing a sustainable option whenever possible.

Ensure you don’t throw away food, and reduce your consumption of plastic—one of the main pollutants of the ocean. Carrying a reusable bag, refusing to use plastic straws, and recycling plastic bottles are good ways to do your part every day.

Making informed purchases also helps. By buying from sustainable and local sources you can make a difference as well as exercising pressure on businesses to adopt sustainable practices.

Facts and figures

Goal 12 targets.

- The material footprint per capita in high-income countries is 10 times the level of low-income countries. The world is also seriously off track in its efforts to halve per capita food waste and losses by 2030.

- Global crises triggered a resurgence in fossil fuel subsidies, nearly doubling from 2020 to 2021.

- Reporting has increased on corporate sustainability and on public procurement policies, but has fallen when it comes to sustainable consumption and monitoring sustainable tourism.

- Responsible consumption and production must be integral to recovery from the pandemic and to acceleration plans of the Sustainable Development Goals. It is crucial to implement policies that support a shift towards sustainable practices and decouple economic growth from resource use.

Source: The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023

12.1 Implement the 10-year framework of programmes on sustainable consumption and production, all countries taking action, with developed countries taking the lead, taking into account the development and capabilities of developing countries

12.2 By 2030, achieve the sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources

12.3 By 2030, halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses

12.4 By 2020, achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes throughout their life cycle, in accordance with agreed international frameworks, and significantly reduce their release to air, water and soil in order to minimize their adverse impacts on human health and the environment

12.5 By 2030, substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse

12.6 Encourage companies, especially large and transnational companies, to adopt sustainable practices and to integrate sustainability information into their reporting cycle

12.7 Promote public procurement practices that are sustainable, in accordance with national policies and priorities

12.8 By 2030, ensure that people everywhere have the relevant information and awareness for sustainable development and lifestyles in harmony with nature

12.A Support developing countries to strengthen their scientific and technological capacity to move towards more sustainable patterns of consumption and production

12.B Develop and implement tools to monitor sustainable development impacts for sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products

12.C Rationalize inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption by removing market distortions, in accordance with national circumstances, including by restructuring taxation and phasing out those harmful subsidies, where they exist, to reflect their environmental impacts, taking fully into account the specific needs and conditions of developing countries and minimizing the possible adverse impacts on their development in a manner that protects the poor and the affected communities

The 10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production

UN Environment Programme – Resource efficiency

FAO website for Sustainable Production

International Telecommunications Union

UNDP page for Sustainable Production & Consumption

Fast Facts: Responsible Consumption and Production

Infographic: Responsible Consumption and Production

Related news

ActNow for Zero-Waste Fashion

2019-08-15T10:34:53-04:00 15 Aug 2019 |

Climate action, at the individual level, involves changing habits and routines by making choices that have less harmful effects on the environment.

Goal of the Month | Exclusive Interview With Michelle Yeoh, UNDP Goodwill Ambassador

2019-06-12T15:49:48-04:00 07 Jun 2019 |

10,000 litres of water are required to make a single pair of jeans. UNDP Goodwill Ambassador Michelle Yeoh gives us tips on how we can adopt sustainable fashion in our daily lives.

Why Waste Water?

Martin 2019-05-31T12:41:23-04:00 30 May 2019 |

UN-Water coordinates the efforts of UN entities and international organizations working on water and sanitation issues. Together, we are the ‘UN-Water family’ and SDG 6 - to ensure the availability and sustainable management of [...]

Related videos

Targeting Plastics: Using nuclear techniques to tackle global challenges

UNDP Goodwill Ambassador Michelle Yeoh follows the sustainable fashion trail

SDG Media Zone: Sustainable Fashion

Watch: how we treat our waste affects our health, environment and even our economies, share this story, choose your platform.

Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns

Related Topics

Chemicals and waste, sustainable consumption and production, sustainable tourism, targets and indicators, progress and info.

Implement the 10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns, all countries taking action, with developed countries taking the lead, taking into account the development and capabilities of developing countries

Number of countries developing, adopting or implementing policy instruments aimed at supporting the shift to sustainable consumption and production

By 2030, achieve the sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources

Material footprint, material footprint per capita, and material footprint per GDP

Domestic material consumption, domestic material consumption per capita, and domestic material consumption per GDP

By 2030, halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses

( a ) Food loss index and ( b ) food waste index

By 2020, achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes throughout their life cycle, in accordance with agreed international frameworks, and significantly reduce their release to air, water and soil in order to minimize their adverse impacts on human health and the environment

Number of parties to international multilateral environmental agreements on hazardous waste, and other chemicals that meet their commitments and obligations in transmitting information as required by each relevant agreement

( a ) Hazardous waste generated per capita; and ( b ) proportion of hazardous waste treated, by type of treatment

By 2030, substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse

National recycling rate, tons of material recycled

Encourage companies, especially large and transnational companies, to adopt sustainable practices and to integrate sustainability information into their reporting cycle

Number of companies publishing sustainability reports

Promote public procurement practices that are sustainable, in accordance with national policies and priorities

Number of countries implementing sustainable public procurement policies and action plans

By 2030, ensure that people everywhere have the relevant information and awareness for sustainable development and lifestyles in harmony with nature

Extent to which (i) global citizenship education and (ii) education for sustainable development are mainstreamed in ( a ) national education policies; ( b ) curricula; ( c ) teacher education; and ( d ) student assessment

Support developing countries to strengthen their scientific and technological capacity to move towards more sustainable patterns of consumption and production

Installed renewable energy-generating capacity in developing and developed countries (in watts per capita)

Develop and implement tools to monitor sustainable development impacts for sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products

Implementation of standard accounting tools to monitor the economic and environmental aspects of tourism sustainability

Rationalize inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption by removing market distortions, in accordance with national circumstances, including by restructuring taxation and phasing out those harmful subsidies, where they exist, to reflect their environmental impacts, taking fully into account the specific needs and conditions of developing countries and minimizing the possible adverse impacts on their development in a manner that protects the poor and the affected communities

Amount of fossil-fuel subsidies (production and consumption) per unit of GDP

The world is seriously off track in its effort to halve per-capita food waste and losses by 2030.The COVID-19 pandemic has had significant impacts on consumption and production patterns, with disruptions to global supply chains and changes in consumer behaviour. Responsible consumption and production must be an integral part of the recovery from the pandemic. But the global economy also needs to speed up the decoupling of economic growth from resource use by maximizing the socio-economic benefits of resources while minimizing their negative impacts. Reporting on corporate sustainability has tripled since the beginning of the SDG period, but the private sector will need to significantly improve reporting on activities that contribute to the SDGs. To deliver SDG12, it is crucial to implement policies that support the shift to sustainable practices and decouple economic growth from resource use.

Target 12.1: Between 2019 and 2022, 484 policy instruments supporting the shift to sustainable consumption and production were reported by 62 countries and the European Union, with increasing linkages with global environmental commitments on climate, biodiversity, pollution and waste, as well as a particular attention to high-impact sectors. Yet, reporting has been decreasing by 30% on average every year since 2019 and continues to reflect great regional imbalances with more than 50% of policy instruments reported from Europe and Central Asia.

Target 12.2: In 2019, the total material footprint was 95.9 billion tonnes, close to the world’s domestic material consumption of 95.1 billion tonnes. In Northern America and Europe, the material footprint was about 14% higher than domestic material consumption, while in Latin America and the Caribbean and sub-Saharan Africa, the material footprint was lower than domestic material consumption by 17% and 32%, respectively.

Target 12.3: The percentage of food lost globally after harvest on farm, transport, storage, wholesale, and processing levels, usually attributed to structural inadequacies in the countries, is estimated at 13.2% in 2021, unchanged from 2016 and far from the target of halving post-harvest food losses by 2030.

Target 12.6: A preliminary analysis shows that around 70% of companies monitored publish sustainability reports in 2022, tripling since 2016. The sustainability indicators that are most widely disclosed by companies include policies on water and energy and CO2 emission, occupational health and safety, as well as board diversity. Companies continue to address their activities in attaining the SDGs, however, only 10% report on all 17 SDGs.

Target 12.7: In 2022, 67 national governments reported to UNEP on the implementation of Sustainable Public Procurement policies and action plans, up 50% from 2020.

Target 12.c: Global data showed a rise in fossil fuel subsidies in 2021, after a brief fall in 2020 which was largely caused by a drop in energy prices. In 2021, Governments spent an estimated $732 billion on subsidies to coal, oil, and gas, against $375 billion in 2020. This brings the subsidies back to pre-2015 levels. High oil and gas prices in 2022 will likely bring a new increase, as subsidies are often linked to the price of energy.

Developing countries bear a large part of the climate, biodiversity and pollution impacts of resource-intensive production processes, without reaping their benefits. This situation has been made worse by the impacts of the pandemic. As part of sustainable global pandemic recovery strategies, the implementation of sustainable consumption and production will maximize the socioeconomic benefits of resource use while minimizing the impacts.

In 2021, 83 policy instruments supporting the shift to sustainable consumption and production were reported by 26 countries, bringing the total number of policies developed, adopted and/or implemented up to 438 (as reported by 59 countries and the European Union for 2019–2021). However, the distribution of reported sustainable consumption and production policies has so far been uneven, with 79 per cent of policies reported by high-income and upper middle income countries, 0.5 per cent by low-income countries and only 7.7 per cent by least developed countries, landlocked developing countries and small island developing States.

The global material footprint continues to grow, although the pace has slowed. The average annual growth rate of the global material footprint for 2015–2019 was 1.1 per cent, compared with 2.8 per cent for 2000–2014, indicating a slowdown in the growth of economic pressure on the environment.

The proportion of food lost globally after harvest on farm, transport, storage, wholesale and processing levels is estimated at 13.3 per cent in 2020, with no visible trend since 2016, suggesting that structural patterns of food losses have not changed. At the regional level, sub-Saharan Africa has the highest proportion of losses at 21.4 per cent, with food being lost in large quantities between the farm and retail levels.

In addition to food loss, it is estimated that 931 million tons of food, or 17 per cent of total food available to consumers in 2019, was wasted at the household, food service and retail levels. Subsequent evidence suggests that household food waste declined during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns but has since returned to pre-pandemic levels.

The COVID-19 pandemic aggravated the global pollution crisis, in particular plastics pollution, making the effective implementation of the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal, the Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade and the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants so much more urgent and important. The year 2021 was marked by the establishment of a new global regime for controlling trade of plastic wastes for better transparency and tracing, following the adoption of the plastic waste amendments to the Basel Convention in 2019.

A preliminary analysis from a sample of over 10,000 public companies around the world shows that over 60 per cent of large companies published sustainability reports in 2021, a twofold increase from 2016. The sustainability indicators that are most widely disclosed by companies include direct CO2 emissions, board diversity E/2022/55 22-06472 19/25 and number of board meetings, while the least disclosed indicators include ozone depleting substances, gender pay gap and bribery and fraud controversies.

By December 2020, 40 countries had reported on sustainable public procurement policies and action plans (or equivalent legal dispositions) to encourage the procurement of environmentally sound, energy-efficient products and to promote more socially responsible purchasing practices and sustainable supply chains.

In 2020, Governments spent $375 billion on subsidies and other support for fossil fuels. While consumer subsidies decreased compared with 2019, this has been due largely to low oil prices and decreased demand during the pandemic rather than to structural reforms.

Source: Progress Towards Sustainable Development Goals- Report of the Secretary-General

For more information, please, check: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/

For decades, scientists have been explaining the ways in which humanity is driving the three planetary crises of climate, biodiversity and pollution, all of which are linked to unsustainable production and consumption. Changes in consumption and production patterns can help to promote the decoupling of economic growth and human well-being from resource use and environmental impact. They can also trigger the transformations envisaged in global commitments on biodiversity, the climate, and sustainable development in general. The COVID-19 pandemic provides a window of opportunity for exploring more inclusive and equitable development models that are underpinned by sustainable consumption and production.

From 2017 to 2020, 83 countries, territories and the European Union shared information on their contribution to the implementation of the 10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns. In 2020, 136 policies and 27 implementation activities were reported, bringing the total number to over 700. While specific actions have been taken to improve resource use efficiency in a specific industry or area, this has not resulted in their widespread adoption across sectors and industries.

Data indicate a rise of almost 40 per cent in the global material footprint per capita, from 8.8 metric tons in 2000 to 12.2 metric tons in 2017. Similarly, domestic material consumption per capita increased by more than 40 per cent, from 8.7 metric tons in 2000 to 12.2 metric tons in 2017.

Although limited data are available, as of 2016, almost 14 per cent of food produced globally was lost before reaching the retail sector. Estimates vary across regions, from 20.7 per cent in Central and Southern Asia to 5.8 per cent in Australia and New Zealand.

In 2019, the amount of e-waste generated was 7.3 kg per capita, with only 1.7 kg per capita documented to be managed in an environmentally sustainable manner. E-waste generation is expected to grow by 0.16 kg per capita annually to reach 9 kg per capita in 2030. The annual rate of growth in e-waste recycling over the past decade was 0.05 kg per capita, which will need to increase more than tenfold if all e-waste is to be recycled by 2030.

A pilot review conducted in 2020 on a random sample of about 4,000 companies in the United Nations Global Compact database and the Sustainability Disclosure database of the Global Reporting Initiative indicates that 85 per cent of companies reported on minimum requirements for sustainability issues and 40 per cent on advanced requirements for such issues.

As of December 2020, 40 countries and territories had reported on sustainable public procurement policies and action plans or equivalent legal dispositions aimed at encouraging the procurement of environmentally sound, energy-efficient products and promoting more socially responsible purchasing practices and sustainable supply chains.

Fossil fuel subsidies declined in 2019 to $431.6 billion as a result of lower fuel prices, reversing the upward trend from 2017 to 2018. Fossil fuel subsidies are expected to fall sharply owing to the collapse in demand caused by COVID-19 mitigation efforts and the oil price shock experienced in 2020.

Source : Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals – E/2021/58

Worldwide consumption and production, a driving force of the global economy, rely on the use of the natural environment and resources in a model that continues to lead to destructive impacts on the planet. The pandemic offers countries an opportunity to build a recovery plan that will reverse current trends and change consumption and production patterns towards a sustainable future.

As at 2019, 79 countries and the European Union reported on at least one national policy instrument that contributed to sustainable consumption and production in their efforts towards the implementation of the 10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns.

Global domestic material consumption per capita rose by 7 per cent, from 10.8 metric tons per capita in 2010 to 11.7 metric tons in 2017, with increases in all regions except Northern America and Africa. However, domestic material consumption per capita in Europe and Northern America is still 40 per cent higher than the global average, indicating the need to enhance resource efficiency and practices to reduce consumption in the future.

The global material footprint rose, from 73.2 billion metric tons in 2010 to 85.9 billion metric tons in 2017, a 17.4 per cent increase since 2010 and a 66.5 per cent increase from 2000. The world’s reliance on natural resources continued to accelerate in the past two decades.

The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer has been universally ratified by 198 parties, and, as a result of its implementation, the overall abundance of ozone-depleting substances in the atmosphere has decreased over the past two decades, with projections to return to 1980 values in the 2030s for northern hemisphere mid-latitude ozone.

From 2010 to 2019, global e-waste generation grew continuously, from 5.3 kg per capita to 7.3 kg per capita, while the environmentally sound recycling of e‑waste increased at a slower pace, from 0.8 kg per capita to 1.3 kg per capita.

Global fossil fuel subsidies amounted to more than $400 billion in 2018. The continued prevalence of such subsidies, more than double the estimated subsidies for renewables, adversely affects the task of achieving an early peak in global carbon dioxide emissions.

Source: Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals, Report of the Secretary-General, https://undocs.org/en/E/2020/57

Worldwide material consumption has expanded rapidly, as has material footprint per capita, seriously jeopardizing the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 12 and the Goals more broadly. Urgent action is needed to ensure that current material needs do not lead to the overextraction of resources or to the degradation of environmental resources, and should include policies that improve resource efficiency, reduce waste and mainstream sustainability practices across all sectors of the economy.

- In 2017, worldwide material consumption reached 92.1 billion tons, up from 87 billion in 2015 and a 254 per cent increase from 27 billion in 1970, with the rate of extraction accelerating every year since 2000. This reflects the increased demand for natural resources that has defined the past decades, resulting in undue burden on environmental resources. Without urgent and concerted political action, it is projected that global resource extraction could grow to 190 billion tons by 2060.

- Material footprint per capita has increased considerably as well: in 1990 some 8.1 tons of natural resources were used to satisfy a person’s need, while in 2015, almost 12 tons of resources were extracted per person.

- Well-designed national policy frameworks and instruments are necessary to enable the fundamental shift towards sustainable consumption and production patterns. In 2018, 71 countries and the European Union reported on a total of 303 policy instruments.

- Parties to the Montreal Protocol and the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions are required to transmit information on the implementation of their obligations under those agreements. However, the rate of transmission varies, with the average compliance rate across these four agreements at approximately 70 per cent.

Source: Report of the Secretary-General, Special edition: progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals

Decoupling economic growth from resource use is one of the most critical and complex challenges facing humanity today. Doing so effectively will require policies that create a conducive environment for such change, social and physical infrastructure and markets, and a profound transformation of business practices along global value chains.

- The per capita “material footprint” of developing countries grew from 5 metric tons in 2000 to 9 metric tons in 2017, representing a significant improvement in the material standard of living. Most of the increase is attributed to a rise in the use of non-metallic minerals, pointing to growth in the areas of infrastructure and construction.

- For all types of materials, developed countries have at least double the per capita footprint of developing countries. In particular, the material footprint for fossil fuels is more than four times higher for developed than developing countries.

- By 2018, a total of 108 countries had national policies and initiatives relevant to sustainable consumption and production.

- According to a recent report from KPMG, 93 per cent of the world’s 250 largest companies (in terms of revenue) are now reporting on sustainability, as are three quarters of the top 100 companies in 49 countries.

Source: Report of the Secretary-General, The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2018

- Economic growth and development require the production of goods and services that improve the quality of life. Sustainable growth and development require minimizing the natural resources and toxic materials used, and the waste and pollutants generated, throughout the entire production and consumption process.

- Two measures, material footprint and domestic material consumption, provide an accounting of global material extraction and use, as well as flows or consumption of materials in countries. The material footprint reflects the amount of primary materials required to meet a country’s needs. It is an indicator of the material standard of living or level of capitalization of an economy. Domestic material consumption measures the amount of natural resources used in economic processes.

- In 2010, the total material footprint in developed regions was significantly higher than that of developing regions, 23.6 kg per unit of GDP versus 14.5 kg per unit of GDP, respectively. The material footprint of developing regions increased from 2000 to 2010, with non-metallic minerals showing the largest increase.

- Domestic material consumption in developed regions has diminished slightly, from 17.5 tonnes per capita in 2000 to 15.3 tonnes per capita in 2010. It remains significantly higher than the value for developing regions, which stood at 8.9 tonnes per capita in 2010. Domestic material consumption per capita increased in almost all developing regions from 2000 to 2010, except in Africa, where it remained relatively stable (around 4 tonnes per capita), and Oceania, where it decreased from around 10.7 to 7.7 tonnes per capita. The rise in domestic material consumption per capita in Asia during that period is primarily a result of rapid industrialization.

- The Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal, the Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade and the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants established international frameworks to achieve the environmentally sound management of hazardous wastes, chemicals and persistent organic pollutants. With six exceptions, all Member States are party to at least one of those conventions. The number of parties to those conventions rose significantly from 2005 to 2015, particularly in Africa and Oceania. There are now 183 parties to the Basel Convention, 180 to the Stockholm Convention and 155 to the Rotterdam Convention.

Source: Report of the Secretary-General, "Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals", E/2016/75

Bridging the Ambition Gap for the Future We Want through Climate and SDGs Synergy

Seventh plenary meeting, final closing plenary, a moment of declaration - reporting back from special events, publications, synergy solutions for a world in crisis: tackling climate and sdg action together, third global conference on strengthening synergies between the paris agreement and the 2030 agenda for sustainable development, sdg good practices-a compilation of success stories and lessons learned in sdg implementation (first edition), exploring youth entrepreneurship.

Governments must seek win-win synergies by tackling climate and sustainable development crises together, urges expert group report

Expert Group to Prepare Report Analysing Climate and SDG Synergies, Aiming to Maximize Action Impact

Call for Inputs for the Global Sustainable Development Report 2023

Search the site

Links to social media channels

Doing More with Less: Ensuring Sustainable Consumption and Production

Still Only One Earth: Lessons from 50 years of UN sustainable development policy

Ensuring sustainable consumption and production patterns has been one of the greatest global challenges over the past fifty years. With the adoption of Sustainable Development Goal 12, “Ensure sustainable consumption and production,” and rising interest in the circular economy model, there is an opportunity to set systems-wide goals for all societies, recognizing that key drivers and solutions lie in our economic, financial and governance decision-making. ( Download PDF ) ( See all policy briefs ) ( Subscribe to ENB )

Every year, about one third of all food produced—about 1.3 billion tonnes—is wasted while 1 billion people remain undernourished and another 1 billion go to bed hungry. Households consume 29% of global energy contributing to 21% of carbon dioxide emissions (UNEP, 2020), pointing to the significant linkage between sustainable consumption and production (SCP) and the climate change challenge of ensuring access to renewable energy and the regulation of building standards to reflect best practice in green architecture.

A family in the Global North throws away an average of 30 kg of clothing each year. Only 15% is recycled or donated, and the rest goes directly to the landfill or is incinerated. Every year, 70 million trees in endangered and ancient forests are cut down and replaced by plantations of trees used to make wood-based fabrics, such as rayon, viscose, and modal (Sustain Your Style, 2020).

Sustainable consumption and production: The use of services and related products, which respond to basic needs and bring a better quality of life while minimizing the use of natural resources and toxic materials as well as the emissions of waste and pollutants over the life cycle of the service or product so as not to jeopardise the need of future generations. Norwegian Ministry of Environment, Oslo Symposium on SCP, 1994

Should the global population reach 9.6 billion by 2050, the equivalent of almost three planets would be required to provide the natural resources needed to sustain current lifestyles (UNEP, 2020). Ensuring SCP has been one of the greatest global challenges over the past fifty years.

Evolution of the “Sustainable Consumption and Production” Theme at the UN

Declarations and plans to take responsibility for sustainable consumption and production patterns have been part and parcel of the United Nations cycle of sustainable development conferences stretching back to the 1972 UN Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm. The conferences continue trying to respond to scientific and civil society demands to recognize “Spaceship Earth” (Fuller, 1968; Ward, 1966) is a closed system with limited capacity to fuel economic growth and absorb its by-products, including pollution and greenhouse gases.

A ground-breaking initiative came in 1972 with the publication of the report, Limits to Growth , by a network of scientists and industrialists known as the Club of Rome (Meadows et. al., 1972). They commissioned the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to use computer simulations to dramatically demonstrate the futility of the human race we cannot win: the race between our capacity to sustain static stocks of resources and satisfy geometric growth rates in population and consumption.

Arguments for restraints in consumption and a steady-state economy followed with Herman Daly’s Toward a Steady-State Economy (1973). This swell of concern had little impact on mainstream debates until 1987 and the publication of the World Commission on Sustainable Development’s report, Our Common Future (Brundtland Commission report). This report stressed that meeting essential human needs requires not only a new era of economic growth for nations where the majority remain in poverty, but an assurance that those living in poverty get their fair share of the resources. Equally, the report called on the affluent to adopt lifestyles within the planet’s ecological means. It has become increasingly well understood that economic growth as an ideology has been used to disguise and defer tackling the persistent problem of inequality.

Sustainable global development requires that those who are more affluent adopt life-styles within the planet's ecological means—in their use of energy, for example... sustainable development can only be pursued if population size and growth are in harmony with the changing productive potential of the ecosystem. Our Common Future , Paragraph 29

Five years later, the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Earth Summit) adopted the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, which called on states to reduce and eliminate unsustainable patterns of production and consumption. After another ten years, the World Summit on Sustainable Development convened in Johannesburg, South Africa, and called for fundamental changes in the way societies produce and consume. This call was accompanied by a mandate for a ten-year framework of programmes (10YFP) to support regional and national initiatives to accelerate the shift toward SCP. This mandate was developed through what was known as the Marrakech Process, launched in 2003, which led to the adoption of the Framework at the 2012 UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20).

In 2015, the UN adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim to end poverty and set the world on a path to peace, prosperity, and opportunity on a healthy planet. SDG 12 , “Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns,” links worldwide consumption and production—a driving force of the global economy—to the use of the natural environment and resources in a way that has destructive impacts on the planet.

Yet with all this attention, the Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020 warned the global material footprint is increasing faster than population growth and economic output. It also notes how improvements in resource efficiency in some countries are offset by increases in intensity in others. Fossil fuel subsidies are also cited as a serious concern, as is the high proportion of food waste lost in long supply chains.

Despite decades of multilateral commitments, the world’s reliance on natural resources has accelerated. The SDG Report 2020 observes the material footprint (primary materials required to meet basic needs for food, clothing, water, shelter, infrastructure and other aspects of life) grew from 73.2 billion metric tons in 2010 to 85.9 billion metric tons in 2017, a 17.4% increase in just seven years. In addition, while 79 countries and the European Union reported on at least one national policy instrument contributing to the implementation of the 10YFP between 2017 and 2019, only 10% of all policies reported in 2019 related to economic and financial instruments, reflecting a limited operationalization of the 10YFP vision.

A shift has taken place in the UN discourse on SCP. While the Brundtland Commission focused on inter-generational equity, consumption volumes, and norms, and made an important distinction between addressing justified universal human “needs” and the “felt wants” of elite consuming classes, the language has changed. Now there is a different and more business-friendly focus on innovation and design in methods of production. This has steered the conversation away from norms and new regulations, enshrining the belief that economic growth can be decoupled from environmental degradation and resource depletion (Gasper et al., 2019, p.84) and created a significant blind spot around the role of corporate power to manufacture desire and elite consumer demands using ever more refined tools in the service of the attention economy.

Sustainable Consumption and Production Timeline

Key debates about the un approach and conceptual developments.

The fundamental terms of reference for the institutional debates on SCP can be traced back to a challenge to dominant assumptions in neo-classical economic theories that depend on notions of infinite growth and a planet without ecological boundaries. These early debates are populated by a colourful cast of pioneering thinkers and campaigners, notably Andre Gorz, Herman Daly, and Serge Latouche. They have their counterparts today in figures such as Kate Raworth , the author of Doughnut Economics , and the thought leaders on sustainable prosperity and growth, Tim Jackson and Peter Victor . None issued a more formative challenge than Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, the intellectual pioneer of ecological economics and bioeconomics. In his Entropy Law and the Economic Process (1971), Georgescu-Roegen performed for economics the intellectual equivalent of colliding two high-energy particle beams at the speed of light . He did this by bringing physics and the natural sciences into a conversation (or collision) with conventional economics. His writing exposed how the fundamental aim of economic activity—the unlimited growth of production and consumption based on finite sources of matter/energy—is incompatible with the laws of nature. His key contributions to the laws of energy conversion, including the concept of “entropy,” explain the degradation of those vital qualities of matter/energy that make them valuable for production and consumption, namely concentration and organization. Matter and energy degradation is countered by a constant inflow of solar energy and other renewable sources of heat and tidal momentum, which explains the current global transition to new sources of energy infrastructure.

Georgescu-Roegen’s ideas helped give rise to the degrowth movement—at first focused in the 1970s on resource limits, then re-emerging in the 2000s as a fundamental assault on what Serge Latouche and others have described as the “oxymoron” concept of “sustainable development.” The degrowth movement is also associated with the birth of political ecology and attempts to re-locate our environmental challenges within dominant institutional and cultural ideas, including capitalism. Advocates call for the decolonization of public debate and the abolition of economic growth as a primary social objective. Instead, they support alternative social practices of sharing, simplicity, conviviality, care, and commoning that are consistent with equitable downscaling of production and consumption, leading to a reduced societal throughput of energy and raw materials. These practices are pursued in new forms of collaborative consumption and ecovillage communities.

SDG 12–Toward a Systems Approach?

The SCP concept is prominently recognized in the 2030 Agenda. SDG 12 recognizes production and consumption habits are at the root of the planet’s sustainability problems and places them at the centre of the sustainable development agenda. Implementation of SDG 12 is linked to the achievement of overall development plans, the reduction of future economic, environmental, and social costs, strengthening economic competitiveness, and the reduction of poverty.

The SDG 12 targets cover a full range of issues, including:

- 12.1: Implement the 10YFP

- 12.2: Sustainable management and use of natural resources

- 12.3: Halve global per capita food waste

- 12.4: Responsible management of chemicals and waste

- 12.5: Substantially reduce waste generation

- 12.6: Encourage companies to adopt sustainable practices and sustainability reporting

- 12.7: Promote sustainable public procurement practices

- 12.8: Promote universal understanding of sustainable lifestyles

- 12.A: Support developing countries’ scientific and technological capacity for SCP

- 12.B: Develop and implement tools to monitor sustainable tourism

- 12.C: Remove market distortions that encourage wasteful consumption