2 Chapter 2. A Crash Course in Linguistics

Adapted from Hagen, Karl. Navigating English Grammar. 2020. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

Language is an extremely complex system consisting of many interrelated components. As a result, learning how to analyze language can be challenging because to understand one part you often need to know about something else. In general, this book works on describing English sentence structure, which largely falls under the category of syntax, but there are other components to language, and to understand syntax, we will need to know a few basics about those other parts.

This chapter has two purposes: first, to give you an overview of the major structural components of language; second, to introduce some basic concepts from areas other than syntax that we will need to make sense of syntax itself.

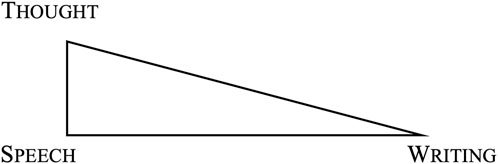

We can think of language both in terms of a message and a medium by which that message is transmitted. These two aspects are partly independent of one another. For example, the same message can be conveyed through speech or through writing. Sound is one medium for transmitting language; writing is another. A third medium, although not one that occurs to most people immediately, is gesture, in other words, sign language. The message is only partly independent of the medium because while it is certainly possible to express the same message through different media, the medium has a tendency to shape the message by virtue of its peculiarities.

When we look at the content of the message, we find it consists of a variety of building blocks. Sounds (or letters) combine to make word parts, which combine to make words, which combine to make sentences, which combine to make a discourse. Indeed, language is often said to be a combinatorial system, where a small number of basic building blocks combine and recombine in different patterns. A small number of blocks can account for a very large variety indeed. DNA, another combinatorial system, uses only four basic blocks, and combinations of these four blocks give rise to all the biological diversity we see on earth today. With language, different combinations of a small number of sounds yield hundreds of thousands of words, and different combinations of those words yield an essentially infinite number of utterances.

The major components that have traditionally been considered the ‘core’ areas of linguistics are the following:

- Phonology : The patterns of sounds in language.

- Morphology : Word formation.

- Syntax : The arrangement of words into larger structural units such as phrases and sentences.

- Semantics : Meaning. Semantics sometimes refers to meaning independent of any particular context, and is distinguished from pragmatics , or how meaning is affected by the context in which it is uttered. For the purposes of this book, we will work under the assumption that there really is no such thing as completely decontextualized meaning.

Section contributors: Saul De Leon, Jodiann N. Samuels and an anonymous ENG 270 student.

Language varieties sound different from one another because they have different inventories of speech sounds. The sounds that you hear—combined into words that make sense—is called phonology . There is no clear limit to the number of distinct sounds that can be constructed by the human vocal apparatus. To that end, this unlimited variety is harnessed by human language into sound systems that are comprised of a few dozen language-specific categories known as phonemes (Szczegielniak). Phonology is the systemic study of sounds used in language, their internal structure, and their composition into syllables, words, and phrases. Sounds are made by pushing air from the lungs out through the mouth, sometimes by way of the nasal cavity (Kleinman). Think about this: All humans have a different way of pronouncing words that produce various sounds. Tongue movement, tenseness, and lip rounding (rounded or unrounded) are some examples in which sounds or even words are produced in different ways. Consider, for example, the sound of the consonant /ð/ represented by the written <th> in the English word <the>—this sound does not exist in French, but we can understand someone whose first language is French when they pronounce the same word with a /z/. Phonology seeks to explain the patterns of sounds that are used and how different rules interact with each other. Phonology is concerned more about the structure of sound instead of the sound itself; “Phonology focuses on the ‘function’ or ‘organization’ or patterning of the sound” (Aarts & McMahon pg. 360)

Every language variety has an inventory of sounds (essentially, they have different numbers of phonemes) and rules for those sounds. By way of illustration, in English, the phoneme /ŋ/, the last sound in the word sing , will never appear at the beginning of a word, but in some other languages, words can begin with /ŋ/.

Throughout this section, we will use the conventional / / slashes to indicate International Phonetic Alphabet representations of phonemes (the sounds of language) and < > brackets to indicate orthography (the way things are spelled in the standardized English writing system).

Say the following out loud: Vvvv. It has a “buzz” sound that ffff does not have, right? Keep in mind that the “buzz” sound is caused by the vibration of your vocal folds. Speech sounds are produced by moving air from the lungs through your larynx, the vocal cords that open to allow breathing—the noise made by the larynx is changed by the tongue, lips, and gums to generate speech. Most importantly, however, sounds are different from letters that are in a word. For example, a world like English has seven letters (<English>), six sounds (/ɪŋɡlɪʃ/), and two syllables (eng·lish). We often tend to think of English as a written language, but when studying phonology, it’s important not to conflate sounds and letters. This is more often true in English than in many other languages that use alphabets for their scripts; not only are the correspondences between sounds and letters not always one-to-one, sounds are often pronounced in many ways by different people. When you are speaking to someone, you automatically ignore nonlinguistic differences in speech (i.e., someone’s pitch level, rate of speed, coughs) (Szczegielniak).

Phonemes are a vital part of speech because they are what dictates how a sound of letter or word is distinguished which differentiates the meaning of words. Sometimes a letter represents more than one phoneme (<x> is often pronounced /ks/) and sometimes two or three letters are used to represent a single sound (like <sh> for the phoneme /ʃ/ ).

The sounds of a word can be broken down into phonemes , the smallest units of sound that distinguish meaning. These basic sounds can be arranged into syllables and a metrical phonological tree can be used to simplify breaking up a syllable (AAL Alumnae, Gussenhoven & Haike).

There are about 200 phonemes across all known languages; however, there are about forty-four in the English language and the forty-four phonemes are represented by the twenty-six letters of the alphabet (individually and in combination). The forty-four English sounds are thus divided into two distinct categories: consonants and vowels. A consonant gives off a basic speech sound in which the airflow is cut off or restrained in some way—when a sound is produced. On the other hand, if the airflow is unhindered when a sound is made, the speaker is producing a vowel. (DSF Literary Resources). Even with diphthongs, or sequences of two vowels, your tongue changes when you say a different vowel.

A syllable consists of an initial sound or onset and followed by another sound called a rhyme. A rhyme is further split into a nucleus which are the vowel sounds and the coda which are the consonants that come after the nucleus. The onset is simply the consonants before the rhyme. These aspects are all brought together to identify the differences of languages due to each language’s unique phonemes and syllable structures. (AAL Alumnae, n.d.).

Phonology and Phonetics

The study of phonology is closely related to another field, phonetics . Phonetics involves the study of the way sound is produced by certain parts of the body. The synchronous use of body parts like the mouth, teeth, tongue, voice box or larynx, and pharynx are involved with making speech sounds and what sounds exist in a language, and in sign languages, the shape and position of fingers and hands serves a similar purpose. Phonology and phonetics together can even analyze the distinction between distinctive accents or challenges native speakers may face attempting to acquire another language when facing phonemes that are not a part of their language (FSI, n.d.; Gussenhoven & Haike, 2017, p. 17).

Minimal Pairs and Allophones

Understanding how to pronounce and to make a clear distinction of letters is essential to the structure of a language sound system. In English and other languages, there are many words that sound similar to one another, but differ in a single sound, like ‘pit’ and ‘bit’, or like ‘leap’ and ‘leave’. Linguists call these minimal pairs. “Minimal pairs are word that differs in one phoneme” (McArthur Oxford Reference). Even though they end identically both words are completely unrelated to each other in meaning. Minimal pairs are useful for linguists because they provide comprehension into how sounds and meanings coexist in language. They tell us which sounds (phones) are distinct phonemes, and which are allophones of the same phoneme.

Allophones are a related concept, in which a single phoneme can be produced differently in different circumstances. For example, the phoneme /k/ in the word ‘kite’ is aspirated, meaning it’s accompanied by a puff of air. But in the word ‘sky’ there is no puff of air along with the /k/ sound. We still think of these as the same sound, and they don’t occur in the same positions, which makes them allophones of a single phoneme.

Allophones are determined by their position in the word or by their phonetic environment. Speakers often have issues hearing the phonetic differences between allophones of the same phoneme because these differences do not serve to distinguish one word from another. In English, the /t/ sounds in the words “hit,” “tip,” and “little” are all allophones (Britannica)—they are all realizations the same phoneme, though they are different phonetically in terms of how they are produced.

The relationship between syntax and phonology

Syntax and phonology are both structural components of language, but it is common to think of them as parallel levels of structure that do not often interact. What they both address at their core is the structure of the language, but we could consider morphology (described in the next section) to mediate between the two.

Citations and Further Reading:

- AAL Alumnae. “Why Study Phonology”. University of Sheffield. 2012a. https://sites.google.com/a/sheffield.ac.uk/aal2013/branches/phonology/why-study-phonology Accessed 09 September 2020.

- Anderson, Catherine. “4.2 Allophones and Predictable Variation.” Essentials of Linguistics, McMaster University, 15 Mar. 2018, https://essentialsoflinguistics.pressbooks.com/chapter/4-3-allophones-and-predictable-variation Accessed: 21 September 2020.

- Bromberger, Sylvain, and Morris Halle. “Why Phonology Is Different.” Linguistic Inquiry , vol. 20, no. 1, 1989, pp. 51–70. JSTOR , www.jstor.org/stable/4178613 Accessed 7 Sept. 2020.

- Collier, Katie, et al. “Language Evolution: Syntax before Phonology?” Proceedings: Biological Sciences , vol. 281, no. 1788, 2014, pp. 1–7. JSTOR , www.jstor.org/stable/43600561. Accessed 7 Sept. 2020 .

- Coxhead, P. “Natural Language Processing & Applications Phones and Phonemes.” University of Birmingham (UK) , 2006, www.cs.bham.ac.uk/~pxc/nlp/NLPA-Phon1.pdf

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Allophone.” Encyclopædia Britannica , Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 26 Feb. 2018, www.britannica.com/topic/allophone .

- FIS. “Phonetics and Phonology.” Language Differences – Phonetics and Phonology . Frankfurt International School. https://esl.fis.edu/grammar/langdiff/phono.htm Accessed 09 September 2020.

- Goswami, Usha. “Phonological Representation.” SpringerLink , Springer, Boston, MA. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6 Accessed: 21 September 2020.

- Gussenhoven, Carlos, and Haike, Jacobs. Understanding phonology . London New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017. https://salahlibrary.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/understanding-phonology-4th-ed.pdf Accessed: 05 September 2020.

- Hayes, Bruce. Introductory Phonology . John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

- Hellmuth, Sam, and Ian Cushing. “Grammar and Phonology.” Oxford Handbooks Online , 14 Nov. 2019, www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198755104.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780198755104-e-2

- Honeybone, Patrick, and Bermudez-Otero, Ricardo. “Phonology and Syntax: A Shifting Relationship.” Lingua, 22 Oct. 2004, pp. 543-561. www.lel.ed.ac.uk/homes/patrick/lingua.pdf Accessed 21 September 2020 .

- K12 Reader. “Phonemic Awareness vs. Phonological Awareness Explained.” Phonemic Awareness vs Phonological Awareness. K12 Reader Reading Instruction Resources, 29 Mar. 2019. www.k12reader.com/phonemic-awareness-vs-phonological-awareness/ Accessed 21 September 2020.

- Kirchner, Robert. “Chapter 1 – Phonetics and Phonology: Understanding the Sounds of Speech.” University of Alberta , https://sites.ualberta.ca/~kirchner/Kirchner_on_Phonology.pdf .

- American Speech-Language Hearing Association. “Language in Brief.” American Speech-Language-Hearing Association , www.asha.org/Practice-Portal/Clinical-Topics/Spoken-Language-Disorders/Language-In–Brief/

- Kleinman, Scott. 2006. “Phonetics and Phonology.” California State University, Northridge , www.csun.edu/~sk36711/WWW/engl400/phonol.pdf

- Szczegielniak, Adam. “Phonology: The Sound Patterns of Language.” Harvard University , https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/adam/files/phonology.ppt.pdf

- Aarts, Bas, and April McMahon. The Handbook of English Linguistics. 1. Aufl. Williston: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. Print.

- De Lacy, Paul V. The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology. Cambridge University Press, 2007. Print.

- McArthur, Tom, Jacqueline Lam-McArthur, and Lise Fontaine. Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press USA – OSO, 2018. Print.

- Philipp Strazny. Encyclopedia of Linguistics. 1st ed. Chicago: Taylor and Francis, 2013. Web.

Contributors: Paul Junior Prudent and an anonymous ENG 270 student

Morphology is a branch of linguistics that deals with the structure and form of the words in a language (Hamawand 2). In grammar, morphology differs from syntax, though both are concerned with structure. Syntax is the field that studies the structure of sentences, which are composed of words, while morphology is the field that studies the structure of the words themselves (Julien 8). Unlike phonology, covered earlier, morphology is more directly related to syntax, and will see some coverage in this textbook.

In language, some words are made up of one indivisible part, but many other words are made up of more than one component, and these components (whether a word has one or more) are called morphemes. A morpheme is a minimal unit of lexical meaning (Hamawand 3). So, while some words can consist of one morpheme and thus be minimal units of meaning in and of themselves, many words consist of more than one morpheme. For example, the word peace has one morpheme and cannot be broken down into smaller units of meaning. Peaceful has two morphemes, peace the state of harmony that exists during the absence of war, plus -ful , a suffix, meaning full of something. Peacefully has three morphemes: peace + – ful + – ly , with the final morpheme – ly indicating ‘in the manner of’. So really, peacefully contains three units of meaning that, when combined, give us the meaning of the word as a whole. Words can have a lot more than three morphemes, however (Kurdi 90).

Comparative Morphology

In some languages, there are only simple words and straightforward compounds, and therefore very little morphology—most of the grammatical complexity is syntactic in these languages. Languages like these are referred to as having an isolating morphology . On the other end of the scale, languages that combine many morphemes to produce words are referred to as polysynthetic . Polysynthetic essentially means that the language is characterized by complex words consisting of several morphemes, in which a single word may function as a whole sentence. Other types of language morphology in between are fusional (where morphemes often encode multiple meanings or grammatical categories at once) and agglutinative (where morphemes are added on to each other to create long words, but generally have individual meanings). Modern English is closer to the isolating end of the spectrum, while still having a productive morphology on some morphemes. Languages like this are known as analytic languages, in which sentences are constructed by following a specific word order.

Types of morphemes

Morphemes can be further divided into several types: free and bound. Free morphemes are the morphemes that can be used by themselves. They’re not dependent on any other morpheme to complete their meaning. Open-class content words (generally speaking, nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs) such as girl , fish , tree , and love are all considered free morphemes, as are closed-class function words (prepositions, determiners, conjunctions, etc.) such as the , and , for , or it (Hamawand 5). Bound morphemes are another class of morphemes that cannot be used by themselves and are dependent on other morphemes, like the -er in worker .

Bound morphemes are further divided into two categories: affixes and bound roots (Kurdi 93). Bound roots are roots that cannot not be used by themselves. For example, the morpheme -ceive in receive , conceive , and deceive cannot stand on its own (Aarts et al. 398). Affixes occur in English primarily as prefixes and suffixes. Prefixes are morphemes that can be added to the front of a word such as pre- in preoccupation , re- in redo , dis- in disapprove or un – in unemployment . Morphemes that can be added to the end of a word (a suffix) such as – an , -ize , -al ,or -ly . In other languages, there are morphemes that can be added to the middle of a word called infixes, and morphemes that can be added to both sides of a word called circumfixes. English also has limited infixation, usually in casual speech and involving taboo language: consider abso-goddamn-lutely or un-fucking-believable . In terms of function, affixes can be divided into two categories of their own: derivational affixes and inflectional affixes (Hamawand 10).

Types of affixes

Derivational affixes are affixes that when added to a word create a new word with a new meaning. They’re called derivational precisely because a new word is derived when they’re added to the original word, and often, but not always, these newly created words belong to a new grammatical category. Some affixes turn nouns into adjectives like beauty to beautiful , some change verbs into nouns like sing to singer , and some change adjectives to adverbs, like precise to precisely . Still others turn nouns to verbs, adjectives to nouns, and verbs to adjectives. Other affixes do not change the grammatical category of the word they’re added to. Adding -dom to king yields kingdom , which is still a noun, and adding re- to do yields redo , still a verb. We use derivational affixes constantly and they’re a very important part of English because they help us to form the majority of words that exist in our language (Aarts et al. 527-529).

In English, the other type of affix, inflectional affixes, are suffixes that when added to the end of the word don’t change its meaning radically. Instead, they change things like the person, tense, and number of a word. English has a total of eight inflectional affixes:

- (on verbs) the third person singular – s as in Anakin kill s younglings ,

- (on verbs) the preterite (and participial) -ed as in Ron kiss ed Hermione ,

- (on verbs) the progressive – ing as in Han is fall ing into the sarlacc pit ,

- (on verbs) the past participle – en in the Emperor has fall en and cannot get up ,

- (on nouns) the plural – s in vampire s make the worst boyfriend s ,

- (on nouns) the possessive -‘s in that’s Luke’ s hand isn’t it ,

- (on adjectives) the comparative – er in the car is cool er than Kirk , and

- (on adjectives) the superlative – est in that’s the sweet est thing I’ve ever seen.

Compared to other languages English has very few inflectional affixes. (Aarts et al. 510), but they’re a common point where confusion emerges, particularly in writing. For example, the third person singular -s, the plural -s, and the possessive -‘s are all pronounced identically, but the possessive often uses an apostrophe.

The Relationship between Morphology and Syntax

Morphology and Syntax are closely related fields in English grammar. Syntax studies the structure of sentences, while morphology studies the formation of words. However, both domains must interact with each other at a certain level. On one level, the morpheme should fit a syntactic representation or a syntactic structure. And on another level, the morpheme can have its syntactic representation. That notion is called “the syntactic approach to morphology” by Marit Julien (8).

- Aarts, Bas, and April McMahon. “The Handbook of English Linguistics.” The Handbook of English Linguistics , 1. Aufl., Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.

- Hamawand, Zeki. Morphology in English Word Formation in Cognitive Grammar. Continuum, 2011.

- Julien, Marit. Syntactic Heads and Word Formation A Study of Verbal Inflection . Oxford University Press, USA, 2002.

- Kurdi, Mohamed Zakaria. “Natural Language Processing and Computational Linguistics 1: Speech, Morphology and Syntax.” Natural Language Processing and Computational Linguistics 1 , John Wiley & Sons (US), 2016.

Speech vs. Writing

Section contributors: Terrell McLean and two anonymous ENG 270 students.

We first learn to speak when we are children, and we do this for at least five years of our lives before we learn to write. Once we learn to do both of these, we think we have mastered the ways of communicating, forgetting that: 1) these two are not the only ways we communicate, and 2) the line, in some cases, is blurred concerning the difference between speech and writing.

Linguists have given more attention to oral communication, giving it more authority and validation, which suggests that written communication is secondary—we learn to speak before we learn to write. However, both speech and writing are forms of language use and deserve equal amounts of recognition.

Differences between Speech and Writing

Let’s take a deeper look at writing and speech. What are some of the distinctions between them? Writing is edited; we can more easily delete or rewrite something over again to make sure how we want to come across is shown in our writing. We can prewrite and brainstorm, which is an effective way of writing (Sadiku 31). This is something we cannot do as we speak. Another reason writing is different from speech because writing is not something everyone can do. Literacy, or the ability to read and write, is not universal, though it is more common today than in previous eras. In some communities today, there are individuals who do not have the skill of writing amongst their neighbors who can. Among the 7000+ languages that exist in the world, more than 3,000 do not have a written language (“How Many Languages in the World Are Unwritten?”) and only 23 languages are spoken by half the population of the world (“Languages in the World”). Written language has historically been seen as a mark of prestige.

The majority of people learn how to speak by the time they are two years old. As we communicate through speech, we have the option of speaking informally or formally. Someone who only speaks formally might find that others say, “You talk like a book” (Bright 1); the book being a textbook or some form of an academic book. However, we all lean towards informal speech when we are surrounded by people we are comfortable with or when we want to be casual.

A greater range of expression is available when using speech because you can use the tone of your voice to express how you feel when you talk about a certain topic. However, the way you use your voice can have many meanings. For example, shouting can mean that you are angry, excited, or surprised. Sometimes you might have to use an extra sentence to connect your tone of voice to how you feel. With writing, a lot of this paralinguistic content (pitch contours, tone of voice) is not available to the reader, but there are strategies writers use like writing in all capital letters or using various forms of punctuation (not a feature available in speech) to compensate.

Finally, a distinction of writing is its durability. Composed messages are passed on through time as well as through space. With writing, we can keep in touch with somebody nearby or on the opposite side of the world (although advances in communication technology have made this true of speech as well).

Similarities between Speech and Writing

In the sections above, we’ve examined differences between speech and writing, but these two forms of language and communication do have similarities as well. Let’s take the example of formal and informal writing and speech. As mentioned before, we can talk informally—talking casually in conversations, or when you’re talking to someone close to you—and this can be done by using slang, short words, and a casual tone of voice. While writing is often thought of as formal by nature, informal writing can also be acceptable in a number of contexts, like freewriting. This is one of the ways we can write informally. In this form of writing, we can write down all the things that come to mind, however we want to write it; it doesn’t matter the quality of the writing or how we produce sentence structure (Elbow 290). Informal writing can also be found in much of what is called Computer-Mediated Communication, or CMC. One example is personal blogs, which are often different from more formal news articles. Blog posts have more flexibility to be informal because most people write with a conversational tone to appeal to their audience.

Writing has often been differentiated from speech by the nature of its participation. According to classical views, when we write, we write by ourselves; writing is done independently. Speech on the other hand is understood to take more than one person because we need at least two people to hold a conversation; therefore, speech is dependent on another person. However, technology has blurred the lines here as well. For example, take the CMC mode of the internet forum (Elbow 291). This media is a form of constant writing where we can continuously respond to people without interruption. This has been set in place since the 70s and one that is popular today that has a collection of forums pertaining to different topics is Reddit. YouTube is also a great example of this because while we watch a video on a particular topic, we can then respond in the comment section immediately and give our own opinions. This conversation can continue with the person in the video and other people that may agree or disagree with you.

Speech, Writing, and Syntax

Syntax is the way words are arranged to form sentences, and is a part of all linguistic communication, regardless of whether it is written or spoken. However, there can be differences in the syntax of speech vs. writing. In a study with 45 students, Gibson found that speech “has fewer words per sentence, fewer syllables per word, a higher degree of interest, and less diversity of vocabulary” (O’Donnell, 102). In another study that Drieman did in Holland, he found that speech, compared to writing, has “longer texts, shorter words, more words of one syllable, fewer attributive adjectives, and a less varied vocabulary” (O’Donnell, 102).

While many think of prescriptive rules applying primarily to written grammar, speech is seen as more lenient, allowing for fluidity nor replicated in written works. However, it comes with own fair share of complexities and rules that need to be managed, one of them being syntax. Syntax is the structuring of words and their overall arrangement in relation to each other. Even though grammar isn’t as strict when it comes to writing a lot of the same principles follow, words need to flow in a cohesive manner that is understandable to others. Even with slang and regional dialect coming into play, syntax creates a cohesive use of language during a conversation. Even in complex usages of language such as code-switching (the use of multiple language varieties in a single discourse event) the necessity for clear structure and communication lies under all of that. In Code Switching and Grammatical Theory the idea is presented that even with code switching in the middle of a sentence, there is a grammatical structure: “In individual cases, intra-sentential code switching is not distributed randomly in the sentence, but rather it occurs at specific points” (Muysken, 155).

Even though both speech and writing require the use of syntax to remain cohesive, the differences between writing and speech are clear and abundant; as Casey Cline writes, “Speech is generally more spontaneous than writing and more likely to stray from the subject under discussion.” (Cline, Verblio ). Written works, on the other hand, are usually seen as something that must stay grammatically correct, thus not being able to always mimic the freedom of speech. As put in Grammar for Writing? “… Grammar is frequently presented as a remediation tool, a language corrective.” (Debra Myhill, 4). However, formal speech and informal writing have existed for a long time, and new communications technologies have increasingly challenged the distinctions between speech and writing.

- Bailey, Trevor. Jones, Susan. Myhill Debra A. “Grammar for Writing? An investigation of the effects of contextualized grammar teaching on students’ writing”. University of Exeter , 2012.

- Brewer, Robert L. “63 Grammar Rules for Writers”. Writer’s Digest , 2020, pp. 4. https://www.writersdigest.com/write-better-fiction/grammar-rules-for-writers/

- Bright, William. “What’s the Difference Between Speech and Writing.” Linguistic Society of America . https://www.linguisticsociety.org/resource/whats-difference-between-speech-and-writing . Accessed 22 September 2020.

- Chafe, Wallace, and Deborah Tannen. “The Relation between Written and Spoken Language.” Annual Review of Anthropology , vol. 16, 1987, pp. 383–407. JSTOR , www.jstor.org/stable/2155877 . Accessed 22 September 2020.

- Cline, Casey. “Do You Write the Way You Speak? Here’s Why Most Good Writer’s Don’t”. Verblio , 2017. https://www.verblio.com/blog/write-the-way-you-speak/ .

- Elbow, Peter. “The Shifting Relationships between Speech and Writing.” College Composition and Communication , vol. 36, no. 3, 1985, pp. 283–303. JSTOR , www.jstor.org/stable/357972 . Accessed 22 September 2020.

- “How Many Languages Are There in the World?” Ethnologue: Languages of the World. https://www.ethnologue.com/guides/how-many-languages

- “How Many Languages in the World Are Unwritten?” Ethnologue: Languages of the World. https://www.ethnologue.com/enterprise-faq/how-many-languages-world-are-unwritten-0. Accessed 6 October 2020.

- Muysken, Pieter. “Code-Switching and Grammatical Theory”. One Speaker, Two Languages: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Code-Switching . Cambridge: Cambridge University Text, 1995 pp.155.

- O’Donnell, Roy C. “Syntactic Differences Between Speech and Writing.” American Speech , vol. 29, no. ½, 1974, pp. 102–110. JSTOR , https://www-jstor-org.york.ezproxy.cuny.edu/stable/3087922 . Accessed 22 September 2020.

Semantics, or the study of meaning in language, is one of the most complex subfields of lingusitics. Semantics can be approached on the word level, examining the meanings of particular words ( lexical semantics ), or on the level of compositionality , in which the way in which meanings interact and compose larger meanings is examined.

Lexical Semantics

Adapted from Anderson, Katherine. Essentials of Linguistics. 10.1 Elements of Word Meaning: Intensions and Extensions

One way to define the meaning of a word is to point to examples in the world of things the word refers to; these examples are the word’s denotation , or extension . Another component of a word’s meaning is the list of attributes in our mind that describe the things the word can refer to; this list is the intension of a word.

If someone asked you, “What’s the meaning of the word pencil ?” you’d probably be able to describe it — it’s something you write with, it has graphite in it, it makes a mark on paper that can be erased, it’s long and thin and doesn’t weigh much. Or you might just hold up a pencil and say, “This is a pencil”. Pointing to an example of something or describing the properties of something, are two pretty different ways of representing a word meaning, but both of them are useful.

One part of how our minds represent word meanings is by using words to refer to things in the world. The denotation of a word or a phrase is the set of things in the world that the word refers to. So one denotation for the word pencil is this pencil right here. All of these things are denotations for the word pencil . Another word for denotation is extension .

If we look at the phrase, the Prime Minister of Canada , the denotation or extension of that phrase right now in 2017 is Justin Trudeau. So does it make sense to say that Trudeau is the meaning of that phrase the Prime Minister of Canada ? Well, only partly: in a couple of years, that phrase might refer to someone else, but that doesn’t mean that its entire meaning would have changed. And in fact, several other phrases, like, the eldest son of former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, and the husband of Sophie Grégoire Trudeau , and the curly-haired leader of the Liberal Party all have Justin Trudeau as their current extension, but that doesn’t mean that all those phrases mean the same thing, does it? Along the same lines, the phrase the President of Canada doesn’t refer to anything at all in the world, because Canada doesn’t have a president, so the phrase has no denotation, but it still has meaning. Clearly, denotation or extension is an important element of word meaning, but it’s not the entire meaning.

We could say that each of these images is one extension for the word bird , but in addition to these particular examples from the bird category, we also have in our minds some list of attributes that a thing needs to have for us to label it as a bird. That mental definition is called our intension . So think for a moment: what is your intension for the word bird ? Probably something like a creature with feathers, wings, claws, a beak, it lays eggs, it can fly. If you see something in the world that you want to label, your mental grammar uses the intension to decide whether that thing in the word is an extension of the label, to decide if it’s a member of the category.

One other important element to the meaning of a word is its connotation : the mental associations we have with the word, some of which arise from the kinds of other words it tends to co-occur with. A word’s connotations will vary from person to person and across cultures, but when we share a mental grammar, we often share many connotations for words. Look at these example sentences:

(1) Dennis is cheap and stingy.

(2) Dennis is frugal and thrifty.

Both sentences are talking about someone who doesn’t like to spend much money, but they have quite different connotations. Calling Dennis cheap and stingy suggests that you think it’s kind of rude or unfriendly that he doesn’t spend much money. But calling him frugal and thrifty suggests that it’s honorable or virtuous not to spend very much. Try to think of some other pairs of words that have similar meanings but different connotations.

To sum up, our mental definition of a word is an intension, and the particular things in the world that a word can refer to are the extension or denotation of a word. Most words also have connotations as part of their meaning; these are the feelings or associations that arise from how and where we use the word.

Compositionality and Ambiguity

Adapted from Anderson, Katherine. Essentials of Linguistics. 9.1 Ambiguity

One core idea in linguistics is that the meaning of some combination or words (that is, of a compound, a phrase or a sentence) arises not just from the meanings of the words themselves, but also from the way those words are combined. This idea is known as compositionality : meaning is composed from word meanings plus morphosyntactic structures.

If structure gives rise to meaning, then it follows that different ways of combining words will lead to different meanings. When a word, phrase, or sentence has more than one meaning, it is ambiguous . The word ambiguous is another of those words that has a specific meaning in linguistics: it doesn’t just mean that a sentence’s meaning is vague or unclear. Ambiguous means that there are two or more distinct meanings available.

In some sentences, ambiguity arises from the possibility of more than one syntactic structure for the sentence. Think about this example:

Hilary saw the pirate with the telescope.

There are two interpretations available here: one is that Hilary has the telescope, and the other is that the pirate has the telescope. Later in this course, you will be able to explain the difference by showing that the prepositional phrase (don’t worry about what that is yet) with the telescope is connected to a structure controlled by either pirate or by saw . This single string of words has two distinct meanings, which arise from two different grammatical ways of combining the words in the sentence. This is known as structural ambiguity or syntactic ambiguity . Structural ambiguity can sometimes lead to some funny interpretations. This often happens in news headlines, where function words get omitted. For example, in December 2017, several news outlets reported, “Lindsay Lohan bitten by snake on holiday in Thailand”, which led a few commentators to express surprise that snakes take holidays.

Another source of ambiguity in English comes not from the syntactic possibilities for combining words, but from the words themselves. If a word has more than one distinct meaning, then using that word in a sentence can lead to lexical ambiguity . In this sentence:

Heike recognized it by its unusual bark.

It’s not clear whether Heike recognizes a tree by the look of the bark on its trunk, or if she recognizes a dog by the sound of its barking. In many cases, the word bark would be disambiguated by the surrounding context, but in the absence of contextual information, the sentence is ambiguous.

This chapter, excepting the sections under ‘Semantics’, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.

Chapter 2. A Crash Course in Linguistics Copyright © 2022 by Matt Garley; Karl Hagen; and The Students of ENG 270 at York College / CUNY is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous

- Next chapter >

Introduction: “Speech” and “Writing”

- Published: March 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This section explores the various advantages of both speech and writing as ways of using language. It considers three realms or dimensions in which speaking and writing operate: speaking and writing as different physical activities, as different physical modalities or media, and as different linguistic products.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, the third dimension. on the dichotomy between speech and writing.

- Faculté des Lettres, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

This paper introduces a more complex and refined articulated view than the classic and simple dichotomy of linguistic production. According to the traditional doxa, what is linguistically articulated is either spoken or written. Forms of written language have previously been considered a secondary representation of spoken forms and, at least in the alphabetic system, the only properly linguistic form. I argue that there exists a third dimension of language, which is internal. This internal form is lexically, phonetically and grammatically articulated, without being spoken in a proper sense, but which can be seen as the pre-condition for both spoken and written production. In other words, linguistic production does not necessarily imply the presence of two interacting speakers (or writers/readers). Production can be seen as the simple effect of an internal activity, and can be described without reduction to spoken or written forms. A consideration of this third dimension in a systematic way could enrich and strengthen approaches to many types of texts and help to productively integrate the traditional schemes adopted in Sociolinguistics, Historical Linguistics, Philology, Literary Criticism, and Pragmatics.

Introduction

Speech in classical linguistic doctrine: saussure.

According to Saussure’s Cours de linguistique générale (from here on CLG , 27 Saussure, 1967 ), the act of parole is an individual one, but is realized as the minimum requirement of two “people who are speaking”:

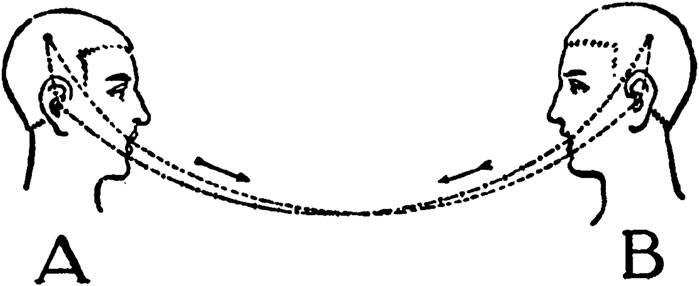

“Pour trouver dans l’ensemble du langage la sphère qui correspond à la langue, il faut se placer devant l’acte individuel qui permet de reconstituer le circuit de la parole. Cet acte suppose au moins deux individus; c’est le minimum exigible pour que le circuit soit complet. Soient donc deux personnes, A et B, qui s’entretiennent”: Figure 1 .

FIGURE 1 . “Le circuit du langage” (from Saussure 1967 : CLG 60).

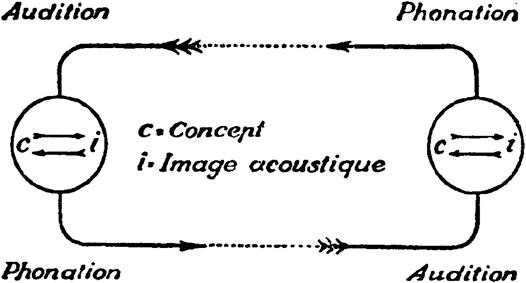

Thus, ideographic systems of writing directly represent the idea of words, and phonetic systems represent their sound ( CLG 47 ss.). Consequently (alphabetic) writing is the representation of the sounds of words, which is manifested in the act of a closed circuit shown above, which assumes two interlocutors. According to Saussure, there exists a connection from a concept to an acoustic image, then to phonation, and finally in inverse order, from a reassociation of the sound to an acoustic image, and then back to the concept Figure 2 .

FIGURE 2 . Phases of saussurean Circuit ( Saussure 1967 : CLG 60).

The written dimension is subordinated, both ontogenetically and phylogenetically, with respect to speech (the latter is identified with language tout court , with an almost imperceptible but crucial deviation). One reads in the CLG 45:

‘Langue et écriture sont deux systèmes de signes distincts; l’unique raison d’être du second est de représenter le premier; l’objet linguistique n’est pas défini par la combinaison du mot écrit et du mot parlé; ce dernier constitue à lui seul cet objet. Mais le mot écrit se mêle si intimement au mot parlé dont il est l’image, qu’il finit par usurper le rôle principal; on en vient à donner autant et plus d’importance à la représentation du signe vocal qu’à ce signe lui-même. C’est comme si l’on croyait que, pour connaître quelqu’un, il vaut mieux regarder sa photographie que son visage ( CLG 45).’

Typical of pre-nineteenth century linguistics was the centrality of writing and written language. Twentieth-century linguistics, then, pushed writing to one side, focusing on the only other perceived dimension, speech. Bloomfield’s famous statement (1935, p. 21) “Writing is not language” became necessarily integrated, in the American structuralist’s perspective, with the notion that the spoken dimension is the only one which duly qualifies as language .

From CLG 45 one can read an entire history of twentieth-century linguistics, which appears to have always taken for granted the dependence of written language on spoken language. This perspective is succinctly highlighted by Martinet, (1972) , p. 70): “a graphic code exists, writing, but apart from this there is no other code: there is language”, obviously referring to speech. There exists almost no twentieth-century treatize which does not define spoken and written language in terms of a dichotomy, and as being the primary (originally, only) and secondary (derived from the first) dimensions of linguistic activity respectively. And there is no work, even among the most recent and attentive studies to questions of the relationship between writing and speech, which does not tend to consider speech simply as the motor of innovation of writing, excluding interference or the role of any other dimension.

Ultimately, according to the model hypothesized by Saussure, spoken language is crucially super-individual. It presupposes at least two individuals, as discussed above. Alphabetic written language is simply a secondary (and often distorted) representation of spoken language, which constitutes the only object of linguistics properly understood (that is, the linguistics of langue , as per the explanation in CLG 38–39).

Twentieth-Century Criticism of the Dichotomy Between Speech and Writing

The dichotomy between speech and writing is discussed at several points during the 20th century. Strictly speaking, this dichotomy is not one of the greatest Saussurian dichotomies, given that Saussure does not theorize it with the same articulation with which he outlines other oppositions, such as those between Langue and Parole, or even Diachrony and Synchrony etc. One reason may be due to the fact that, from his point of view, the written dimension is simply external to the field of linguistics. Already from a structuralist perspective à la Hjelmslev (1966, pp. 131–32), in fact, we see how written and spoken language are not derived from each other, but are simply two manifestations of the same form. In this account, the priority for speech over writing had already been questioned—not from a historical point of view, but from an axiological and epistemological one.

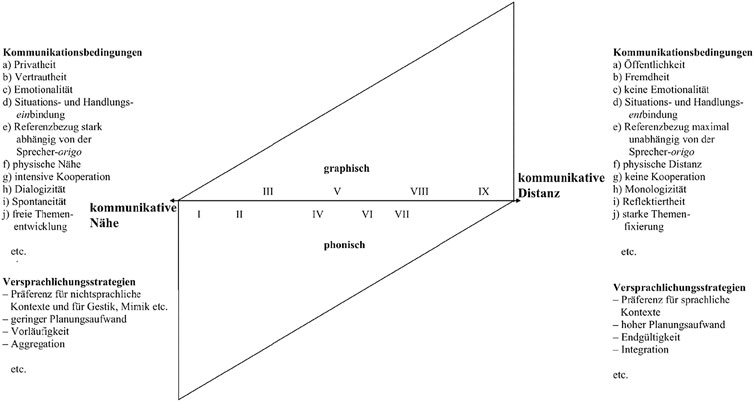

Among the most important discussions, there has been some attempt to refine the sharpness of the boundary between the two fields, highlighting the elements of continuity and, in part, intersection. This is the case of the Koch-Österreicher (1990) model: to the simple distinction between written language vs. spoken language, the two German Romanists oppose a model based on the concepts of distance vs. closeness. These concepts allow, on the one hand, a further realization of the sociolinguistic aspect of situations devoid of writing, and on the other hand, allow us to frame those phenomena which are clearly mixed or hybrid.

The Koch-Österreicher model proposes a scale of distance (and of the quantity of interlocutors included by the single linguistic act) whose minimum value is in fact 1. The conditions of communication are identified, in the first instance, in the Grad der Öffentlichkeit («für den die Zahl der Rezipienten—vom Zweiengespräch bis zum hin zur Massenkommunikation», Koch-Österreicher 2011, p. 7, Italics mine). In short, as in the Saussurian model, there does not appear to be an inferior degree with respect to communication when two are present.

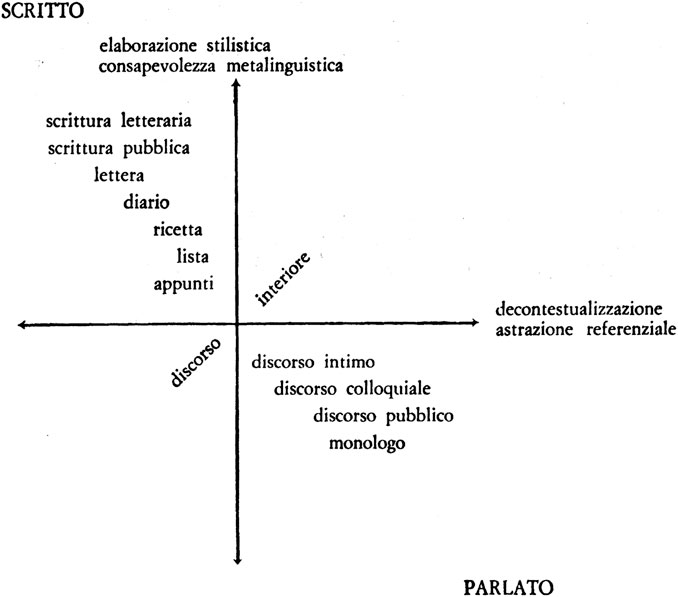

Linguistics in the late 20th century elaborated the concept of diamesic variation (a term invented by Mioni 1983 , extending a series of analogous categories from Coseriu). But it struggled to demonstrate that there exist various “intermediate” positions between these two poles. Apparently, the poles are not united (as instead occurs for similar polarities, such as the classic dimensions of sociolinguistic variation).

A further contribution to overcoming the exclusive and rigid dichotomy between writing and speech was provided by the twentieth-century development of studies on sign language (SL). It is thanks to this line of research and the continued appreciation of SL as an alternative channel to spoken and written language, that traditional expressions such as “spoken or written language” are often substituted with other ones. In recent studies, a trinomial “spoken, signed or written language” (for example, as recently as in Haspelmath 2020 , p. 2) has entered the literature. In short, one finds an all-encompassing category of verbal language in addition to the traditional dichotomy of spoken/written language. This category synthesizes, rather than supersedes, the old contraposition (notwithstanding the distinct nature of signed languages, which can be acquired spontaneously, with respect to writing, and which are the fruit of cultural transmission and learning).

In sum, twentieth-century linguistics approaches the polarities of written vs. spoken language both in a theoretical perspective as well as in a specifically sociolinguistic perspective. Linguistics aimed to overcome this conception as an exclusive dichotomy, placing greater emphasis on those elements of continuity which overlap. This approach was favored also by the emergence of new methodologies of communication. A further contribution to superseding the written/spoken duality was provided by research on sign language: dealing, as it does, with phenomena that cannot be reduced to either category, nor to either one of the polarities.

The Internal Text of G. R. Cardona

Among the few contributions which properly highlighted the linguistic question posed by an internal text, and taking inspiration from both literary and non-literary texts, is the work of Giorgio Raimondo Cardona, (1986 , reprinted Cardona, 1990 ). Published 2 years before his unexpected and premature death, the article deals with “mental text” as an indispensable premise for the production of any oral, but especially written, text.

Let us consider in particular one of the crucial passages of Cardona’s essay: “There is no analytic thread (whatever its itinerary may be) that can be exempt from choosing internal discourse as a point of departure: apart from some cases of automatic writing or trance or similar, no external communicative activity can be disregarded from endophasic, mental and communicative discourse”.