Thesis Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout describes what a thesis statement is, how thesis statements work in your writing, and how you can craft or refine one for your draft.

Introduction

Writing in college often takes the form of persuasion—convincing others that you have an interesting, logical point of view on the subject you are studying. Persuasion is a skill you practice regularly in your daily life. You persuade your roommate to clean up, your parents to let you borrow the car, your friend to vote for your favorite candidate or policy. In college, course assignments often ask you to make a persuasive case in writing. You are asked to convince your reader of your point of view. This form of persuasion, often called academic argument, follows a predictable pattern in writing. After a brief introduction of your topic, you state your point of view on the topic directly and often in one sentence. This sentence is the thesis statement, and it serves as a summary of the argument you’ll make in the rest of your paper.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement:

- tells the reader how you will interpret the significance of the subject matter under discussion.

- is a road map for the paper; in other words, it tells the reader what to expect from the rest of the paper.

- directly answers the question asked of you. A thesis is an interpretation of a question or subject, not the subject itself. The subject, or topic, of an essay might be World War II or Moby Dick; a thesis must then offer a way to understand the war or the novel.

- makes a claim that others might dispute.

- is usually a single sentence near the beginning of your paper (most often, at the end of the first paragraph) that presents your argument to the reader. The rest of the paper, the body of the essay, gathers and organizes evidence that will persuade the reader of the logic of your interpretation.

If your assignment asks you to take a position or develop a claim about a subject, you may need to convey that position or claim in a thesis statement near the beginning of your draft. The assignment may not explicitly state that you need a thesis statement because your instructor may assume you will include one. When in doubt, ask your instructor if the assignment requires a thesis statement. When an assignment asks you to analyze, to interpret, to compare and contrast, to demonstrate cause and effect, or to take a stand on an issue, it is likely that you are being asked to develop a thesis and to support it persuasively. (Check out our handout on understanding assignments for more information.)

How do I create a thesis?

A thesis is the result of a lengthy thinking process. Formulating a thesis is not the first thing you do after reading an essay assignment. Before you develop an argument on any topic, you have to collect and organize evidence, look for possible relationships between known facts (such as surprising contrasts or similarities), and think about the significance of these relationships. Once you do this thinking, you will probably have a “working thesis” that presents a basic or main idea and an argument that you think you can support with evidence. Both the argument and your thesis are likely to need adjustment along the way.

Writers use all kinds of techniques to stimulate their thinking and to help them clarify relationships or comprehend the broader significance of a topic and arrive at a thesis statement. For more ideas on how to get started, see our handout on brainstorming .

How do I know if my thesis is strong?

If there’s time, run it by your instructor or make an appointment at the Writing Center to get some feedback. Even if you do not have time to get advice elsewhere, you can do some thesis evaluation of your own. When reviewing your first draft and its working thesis, ask yourself the following :

- Do I answer the question? Re-reading the question prompt after constructing a working thesis can help you fix an argument that misses the focus of the question. If the prompt isn’t phrased as a question, try to rephrase it. For example, “Discuss the effect of X on Y” can be rephrased as “What is the effect of X on Y?”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? If your thesis simply states facts that no one would, or even could, disagree with, it’s possible that you are simply providing a summary, rather than making an argument.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? Thesis statements that are too vague often do not have a strong argument. If your thesis contains words like “good” or “successful,” see if you could be more specific: why is something “good”; what specifically makes something “successful”?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? If a reader’s first response is likely to be “So what?” then you need to clarify, to forge a relationship, or to connect to a larger issue.

- Does my essay support my thesis specifically and without wandering? If your thesis and the body of your essay do not seem to go together, one of them has to change. It’s okay to change your working thesis to reflect things you have figured out in the course of writing your paper. Remember, always reassess and revise your writing as necessary.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? If a reader’s first response is “how?” or “why?” your thesis may be too open-ended and lack guidance for the reader. See what you can add to give the reader a better take on your position right from the beginning.

Suppose you are taking a course on contemporary communication, and the instructor hands out the following essay assignment: “Discuss the impact of social media on public awareness.” Looking back at your notes, you might start with this working thesis:

Social media impacts public awareness in both positive and negative ways.

You can use the questions above to help you revise this general statement into a stronger thesis.

- Do I answer the question? You can analyze this if you rephrase “discuss the impact” as “what is the impact?” This way, you can see that you’ve answered the question only very generally with the vague “positive and negative ways.”

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not likely. Only people who maintain that social media has a solely positive or solely negative impact could disagree.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? No. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? No. Why are they positive? How are they positive? What are their causes? Why are they negative? How are they negative? What are their causes?

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? No. Why should anyone care about the positive and/or negative impact of social media?

After thinking about your answers to these questions, you decide to focus on the one impact you feel strongly about and have strong evidence for:

Because not every voice on social media is reliable, people have become much more critical consumers of information, and thus, more informed voters.

This version is a much stronger thesis! It answers the question, takes a specific position that others can challenge, and it gives a sense of why it matters.

Let’s try another. Suppose your literature professor hands out the following assignment in a class on the American novel: Write an analysis of some aspect of Mark Twain’s novel Huckleberry Finn. “This will be easy,” you think. “I loved Huckleberry Finn!” You grab a pad of paper and write:

Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is a great American novel.

You begin to analyze your thesis:

- Do I answer the question? No. The prompt asks you to analyze some aspect of the novel. Your working thesis is a statement of general appreciation for the entire novel.

Think about aspects of the novel that are important to its structure or meaning—for example, the role of storytelling, the contrasting scenes between the shore and the river, or the relationships between adults and children. Now you write:

In Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain develops a contrast between life on the river and life on the shore.

- Do I answer the question? Yes!

- Have I taken a position that others might challenge or oppose? Not really. This contrast is well-known and accepted.

- Is my thesis statement specific enough? It’s getting there–you have highlighted an important aspect of the novel for investigation. However, it’s still not clear what your analysis will reveal.

- Does my thesis pass the “how and why?” test? Not yet. Compare scenes from the book and see what you discover. Free write, make lists, jot down Huck’s actions and reactions and anything else that seems interesting.

- Does my thesis pass the “So what?” test? What’s the point of this contrast? What does it signify?”

After examining the evidence and considering your own insights, you write:

Through its contrasting river and shore scenes, Twain’s Huckleberry Finn suggests that to find the true expression of American democratic ideals, one must leave “civilized” society and go back to nature.

This final thesis statement presents an interpretation of a literary work based on an analysis of its content. Of course, for the essay itself to be successful, you must now present evidence from the novel that will convince the reader of your interpretation.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ramage, John D., John C. Bean, and June Johnson. 2018. The Allyn & Bacon Guide to Writing , 8th ed. New York: Pearson.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Developing a Thesis Statement

Many papers you write require developing a thesis statement. In this section you’ll learn what a thesis statement is and how to write one.

Keep in mind that not all papers require thesis statements . If in doubt, please consult your instructor for assistance.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement . . .

- Makes an argumentative assertion about a topic; it states the conclusions that you have reached about your topic.

- Makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of your paper.

- Is focused and specific enough to be “proven” within the boundaries of your paper.

- Is generally located near the end of the introduction ; sometimes, in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or in an entire paragraph.

- Identifies the relationships between the pieces of evidence that you are using to support your argument.

Not all papers require thesis statements! Ask your instructor if you’re in doubt whether you need one.

Identify a topic

Your topic is the subject about which you will write. Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic; or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper.

Consider what your assignment asks you to do

Inform yourself about your topic, focus on one aspect of your topic, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts, generate a topic from an assignment.

Below are some possible topics based on sample assignments.

Sample assignment 1

Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II.

Identified topic

Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis

This topic avoids generalities such as “Spain” and “World War II,” addressing instead on Franco’s role (a specific aspect of “Spain”) and the diplomatic relations between the Allies and Axis (a specific aspect of World War II).

Sample assignment 2

Analyze one of Homer’s epic similes in the Iliad.

The relationship between the portrayal of warfare and the epic simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64.

This topic focuses on a single simile and relates it to a single aspect of the Iliad ( warfare being a major theme in that work).

Developing a Thesis Statement–Additional information

Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic, or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper. You’ll want to read your assignment carefully, looking for key terms that you can use to focus your topic.

Sample assignment: Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II Key terms: analyze, Spain’s neutrality, World War II

After you’ve identified the key words in your topic, the next step is to read about them in several sources, or generate as much information as possible through an analysis of your topic. Obviously, the more material or knowledge you have, the more possibilities will be available for a strong argument. For the sample assignment above, you’ll want to look at books and articles on World War II in general, and Spain’s neutrality in particular.

As you consider your options, you must decide to focus on one aspect of your topic. This means that you cannot include everything you’ve learned about your topic, nor should you go off in several directions. If you end up covering too many different aspects of a topic, your paper will sprawl and be unconvincing in its argument, and it most likely will not fulfull the assignment requirements.

For the sample assignment above, both Spain’s neutrality and World War II are topics far too broad to explore in a paper. You may instead decide to focus on Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis , which narrows down what aspects of Spain’s neutrality and World War II you want to discuss, as well as establishes a specific link between those two aspects.

Before you go too far, however, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts. Try to avoid topics that already have too much written about them (i.e., “eating disorders and body image among adolescent women”) or that simply are not important (i.e. “why I like ice cream”). These topics may lead to a thesis that is either dry fact or a weird claim that cannot be supported. A good thesis falls somewhere between the two extremes. To arrive at this point, ask yourself what is new, interesting, contestable, or controversial about your topic.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times . Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Derive a main point from topic

Once you have a topic, you will have to decide what the main point of your paper will be. This point, the “controlling idea,” becomes the core of your argument (thesis statement) and it is the unifying idea to which you will relate all your sub-theses. You can then turn this “controlling idea” into a purpose statement about what you intend to do in your paper.

Look for patterns in your evidence

Compose a purpose statement.

Consult the examples below for suggestions on how to look for patterns in your evidence and construct a purpose statement.

- Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis

- Franco turned to the Allies when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from the Axis

Possible conclusion:

Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: Franco’s desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power.

Purpose statement

This paper will analyze Franco’s diplomacy during World War II to see how it contributed to Spain’s neutrality.

- The simile compares Simoisius to a tree, which is a peaceful, natural image.

- The tree in the simile is chopped down to make wheels for a chariot, which is an object used in warfare.

At first, the simile seems to take the reader away from the world of warfare, but we end up back in that world by the end.

This paper will analyze the way the simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64 moves in and out of the world of warfare.

Derive purpose statement from topic

To find out what your “controlling idea” is, you have to examine and evaluate your evidence . As you consider your evidence, you may notice patterns emerging, data repeated in more than one source, or facts that favor one view more than another. These patterns or data may then lead you to some conclusions about your topic and suggest that you can successfully argue for one idea better than another.

For instance, you might find out that Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis, but when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from them, he turned to the Allies. As you read more about Franco’s decisions, you may conclude that Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: his desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power. Based on this conclusion, you can then write a trial thesis statement to help you decide what material belongs in your paper.

Sometimes you won’t be able to find a focus or identify your “spin” or specific argument immediately. Like some writers, you might begin with a purpose statement just to get yourself going. A purpose statement is one or more sentences that announce your topic and indicate the structure of the paper but do not state the conclusions you have drawn . Thus, you might begin with something like this:

- This paper will look at modern language to see if it reflects male dominance or female oppression.

- I plan to analyze anger and derision in offensive language to see if they represent a challenge of society’s authority.

At some point, you can turn a purpose statement into a thesis statement. As you think and write about your topic, you can restrict, clarify, and refine your argument, crafting your thesis statement to reflect your thinking.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Compose a draft thesis statement

If you are writing a paper that will have an argumentative thesis and are having trouble getting started, the techniques in the table below may help you develop a temporary or “working” thesis statement.

Begin with a purpose statement that you will later turn into a thesis statement.

Assignment: Discuss the history of the Reform Party and explain its influence on the 1990 presidential and Congressional election.

Purpose Statement: This paper briefly sketches the history of the grassroots, conservative, Perot-led Reform Party and analyzes how it influenced the economic and social ideologies of the two mainstream parties.

Question-to-Assertion

If your assignment asks a specific question(s), turn the question(s) into an assertion and give reasons why it is true or reasons for your opinion.

Assignment : What do Aylmer and Rappaccini have to be proud of? Why aren’t they satisfied with these things? How does pride, as demonstrated in “The Birthmark” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” lead to unexpected problems?

Beginning thesis statement: Alymer and Rappaccinni are proud of their great knowledge; however, they are also very greedy and are driven to use their knowledge to alter some aspect of nature as a test of their ability. Evil results when they try to “play God.”

Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main idea: The reason some toys succeed in the market is that they appeal to the consumers’ sense of the ridiculous and their basic desire to laugh at themselves.

Make a list of the ideas that you want to include; consider the ideas and try to group them.

- nature = peaceful

- war matériel = violent (competes with 1?)

- need for time and space to mourn the dead

- war is inescapable (competes with 3?)

Use a formula to arrive at a working thesis statement (you will revise this later).

- although most readers of _______ have argued that _______, closer examination shows that _______.

- _______ uses _______ and _____ to prove that ________.

- phenomenon x is a result of the combination of __________, __________, and _________.

What to keep in mind as you draft an initial thesis statement

Beginning statements obtained through the methods illustrated above can serve as a framework for planning or drafting your paper, but remember they’re not yet the specific, argumentative thesis you want for the final version of your paper. In fact, in its first stages, a thesis statement usually is ill-formed or rough and serves only as a planning tool.

As you write, you may discover evidence that does not fit your temporary or “working” thesis. Or you may reach deeper insights about your topic as you do more research, and you will find that your thesis statement has to be more complicated to match the evidence that you want to use.

You must be willing to reject or omit some evidence in order to keep your paper cohesive and your reader focused. Or you may have to revise your thesis to match the evidence and insights that you want to discuss. Read your draft carefully, noting the conclusions you have drawn and the major ideas which support or prove those conclusions. These will be the elements of your final thesis statement.

Sometimes you will not be able to identify these elements in your early drafts, but as you consider how your argument is developing and how your evidence supports your main idea, ask yourself, “ What is the main point that I want to prove/discuss? ” and “ How will I convince the reader that this is true? ” When you can answer these questions, then you can begin to refine the thesis statement.

Refine and polish the thesis statement

To get to your final thesis, you’ll need to refine your draft thesis so that it’s specific and arguable.

- Ask if your draft thesis addresses the assignment

- Question each part of your draft thesis

- Clarify vague phrases and assertions

- Investigate alternatives to your draft thesis

Consult the example below for suggestions on how to refine your draft thesis statement.

Sample Assignment

Choose an activity and define it as a symbol of American culture. Your essay should cause the reader to think critically about the society which produces and enjoys that activity.

- Ask The phenomenon of drive-in facilities is an interesting symbol of american culture, and these facilities demonstrate significant characteristics of our society.This statement does not fulfill the assignment because it does not require the reader to think critically about society.

Drive-ins are an interesting symbol of American culture because they represent Americans’ significant creativity and business ingenuity.

Among the types of drive-in facilities familiar during the twentieth century, drive-in movie theaters best represent American creativity, not merely because they were the forerunner of later drive-ins and drive-throughs, but because of their impact on our culture: they changed our relationship to the automobile, changed the way people experienced movies, and changed movie-going into a family activity.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast-food establishments, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize America’s economic ingenuity, they also have affected our personal standards.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast- food restaurants, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize (1) Americans’ business ingenuity, they also have contributed (2) to an increasing homogenization of our culture, (3) a willingness to depersonalize relationships with others, and (4) a tendency to sacrifice quality for convenience.

This statement is now specific and fulfills all parts of the assignment. This version, like any good thesis, is not self-evident; its points, 1-4, will have to be proven with evidence in the body of the paper. The numbers in this statement indicate the order in which the points will be presented. Depending on the length of the paper, there could be one paragraph for each numbered item or there could be blocks of paragraph for even pages for each one.

Complete the final thesis statement

The bottom line.

As you move through the process of crafting a thesis, you’ll need to remember four things:

- Context matters! Think about your course materials and lectures. Try to relate your thesis to the ideas your instructor is discussing.

- As you go through the process described in this section, always keep your assignment in mind . You will be more successful when your thesis (and paper) responds to the assignment than if it argues a semi-related idea.

- Your thesis statement should be precise, focused, and contestable ; it should predict the sub-theses or blocks of information that you will use to prove your argument.

- Make sure that you keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Change your thesis as your paper evolves, because you do not want your thesis to promise more than your paper actually delivers.

In the beginning, the thesis statement was a tool to help you sharpen your focus, limit material and establish the paper’s purpose. When your paper is finished, however, the thesis statement becomes a tool for your reader. It tells the reader what you have learned about your topic and what evidence led you to your conclusion. It keeps the reader on track–well able to understand and appreciate your argument.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- Mission, Vision, and Inclusive Language Statement

- Locations & Hours

- Undergraduate Employment

- Graduate Employment

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Newsletter Archive

- Support WTS

- Schedule an Appointment

- Online Tutoring

- Before your Appointment

- WTS Policies

- Group Tutoring

- Students Referred by Instructors

- Paid External Editing Services

- Writing Guides

- Scholarly Write-in

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Journal Article Writing Groups

- Early Career Graduate Student Writing Workshop

- Workshops for Graduate Students

- Teaching Resources

- Syllabus Information

- Course-specific Tutoring

- Nominate a Peer Tutor

- Tutoring Feedback

- Schedule Appointment

- Campus Writing Program

Writing Tutorial Services

How to write a thesis statement, what is a thesis statement.

Almost all of us—even if we don’t do it consciously—look early in an essay for a one- or two-sentence condensation of the argument or analysis that is to follow. We refer to that condensation as a thesis statement.

Why Should Your Essay Contain a Thesis Statement?

- to test your ideas by distilling them into a sentence or two

- to better organize and develop your argument

- to provide your reader with a “guide” to your argument

In general, your thesis statement will accomplish these goals if you think of the thesis as the answer to the question your paper explores.

How Can You Write a Good Thesis Statement?

Here are some helpful hints to get you started. You can either scroll down or select a link to a specific topic.

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is not Assigned How to Tell a Strong Thesis Statement from a Weak One

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is Assigned

Almost all assignments, no matter how complicated, can be reduced to a single question. Your first step, then, is to distill the assignment into a specific question. For example, if your assignment is, “Write a report to the local school board explaining the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class,” turn the request into a question like, “What are the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class?” After you’ve chosen the question your essay will answer, compose one or two complete sentences answering that question.

Q: “What are the potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class?” A: “The potential benefits of using computers in a fourth-grade class are . . .”

A: “Using computers in a fourth-grade class promises to improve . . .”

The answer to the question is the thesis statement for the essay.

[ Back to top ]

How to Generate a Thesis Statement if the Topic is not Assigned

Even if your assignment doesn’t ask a specific question, your thesis statement still needs to answer a question about the issue you’d like to explore. In this situation, your job is to figure out what question you’d like to write about.

A good thesis statement will usually include the following four attributes:

- take on a subject upon which reasonable people could disagree

- deal with a subject that can be adequately treated given the nature of the assignment

- express one main idea

- assert your conclusions about a subject

Let’s see how to generate a thesis statement for a social policy paper.

Brainstorm the topic . Let’s say that your class focuses upon the problems posed by changes in the dietary habits of Americans. You find that you are interested in the amount of sugar Americans consume.

You start out with a thesis statement like this:

Sugar consumption.

This fragment isn’t a thesis statement. Instead, it simply indicates a general subject. Furthermore, your reader doesn’t know what you want to say about sugar consumption.

Narrow the topic . Your readings about the topic, however, have led you to the conclusion that elementary school children are consuming far more sugar than is healthy.

You change your thesis to look like this:

Reducing sugar consumption by elementary school children.

This fragment not only announces your subject, but it focuses on one segment of the population: elementary school children. Furthermore, it raises a subject upon which reasonable people could disagree, because while most people might agree that children consume more sugar than they used to, not everyone would agree on what should be done or who should do it. You should note that this fragment is not a thesis statement because your reader doesn’t know your conclusions on the topic.

Take a position on the topic. After reflecting on the topic a little while longer, you decide that what you really want to say about this topic is that something should be done to reduce the amount of sugar these children consume.

You revise your thesis statement to look like this:

More attention should be paid to the food and beverage choices available to elementary school children.

This statement asserts your position, but the terms more attention and food and beverage choices are vague.

Use specific language . You decide to explain what you mean about food and beverage choices , so you write:

Experts estimate that half of elementary school children consume nine times the recommended daily allowance of sugar.

This statement is specific, but it isn’t a thesis. It merely reports a statistic instead of making an assertion.

Make an assertion based on clearly stated support. You finally revise your thesis statement one more time to look like this:

Because half of all American elementary school children consume nine times the recommended daily allowance of sugar, schools should be required to replace the beverages in soda machines with healthy alternatives.

Notice how the thesis answers the question, “What should be done to reduce sugar consumption by children, and who should do it?” When you started thinking about the paper, you may not have had a specific question in mind, but as you became more involved in the topic, your ideas became more specific. Your thesis changed to reflect your new insights.

How to Tell a Strong Thesis Statement from a Weak One

1. a strong thesis statement takes some sort of stand..

Remember that your thesis needs to show your conclusions about a subject. For example, if you are writing a paper for a class on fitness, you might be asked to choose a popular weight-loss product to evaluate. Here are two thesis statements:

There are some negative and positive aspects to the Banana Herb Tea Supplement.

This is a weak thesis statement. First, it fails to take a stand. Second, the phrase negative and positive aspects is vague.

Because Banana Herb Tea Supplement promotes rapid weight loss that results in the loss of muscle and lean body mass, it poses a potential danger to customers.

This is a strong thesis because it takes a stand, and because it's specific.

2. A strong thesis statement justifies discussion.

Your thesis should indicate the point of the discussion. If your assignment is to write a paper on kinship systems, using your own family as an example, you might come up with either of these two thesis statements:

My family is an extended family.

This is a weak thesis because it merely states an observation. Your reader won’t be able to tell the point of the statement, and will probably stop reading.

While most American families would view consanguineal marriage as a threat to the nuclear family structure, many Iranian families, like my own, believe that these marriages help reinforce kinship ties in an extended family.

This is a strong thesis because it shows how your experience contradicts a widely-accepted view. A good strategy for creating a strong thesis is to show that the topic is controversial. Readers will be interested in reading the rest of the essay to see how you support your point.

3. A strong thesis statement expresses one main idea.

Readers need to be able to see that your paper has one main point. If your thesis statement expresses more than one idea, then you might confuse your readers about the subject of your paper. For example:

Companies need to exploit the marketing potential of the Internet, and Web pages can provide both advertising and customer support.

This is a weak thesis statement because the reader can’t decide whether the paper is about marketing on the Internet or Web pages. To revise the thesis, the relationship between the two ideas needs to become more clear. One way to revise the thesis would be to write:

Because the Internet is filled with tremendous marketing potential, companies should exploit this potential by using Web pages that offer both advertising and customer support.

This is a strong thesis because it shows that the two ideas are related. Hint: a great many clear and engaging thesis statements contain words like because , since , so , although , unless , and however .

4. A strong thesis statement is specific.

A thesis statement should show exactly what your paper will be about, and will help you keep your paper to a manageable topic. For example, if you're writing a seven-to-ten page paper on hunger, you might say:

World hunger has many causes and effects.

This is a weak thesis statement for two major reasons. First, world hunger can’t be discussed thoroughly in seven to ten pages. Second, many causes and effects is vague. You should be able to identify specific causes and effects. A revised thesis might look like this:

Hunger persists in Glandelinia because jobs are scarce and farming in the infertile soil is rarely profitable.

This is a strong thesis statement because it narrows the subject to a more specific and manageable topic, and it also identifies the specific causes for the existence of hunger.

Produced by Writing Tutorial Services, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN

Writing Tutorial Services social media channels

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Thesis Statements

Basics of thesis statements.

The thesis statement is the brief articulation of your paper's central argument and purpose. You might hear it referred to as simply a "thesis." Every scholarly paper should have a thesis statement, and strong thesis statements are concise, specific, and arguable. Concise means the thesis is short: perhaps one or two sentences for a shorter paper. Specific means the thesis deals with a narrow and focused topic, appropriate to the paper's length. Arguable means that a scholar in your field could disagree (or perhaps already has!).

Strong thesis statements address specific intellectual questions, have clear positions, and use a structure that reflects the overall structure of the paper. Read on to learn more about constructing a strong thesis statement.

Being Specific

This thesis statement has no specific argument:

Needs Improvement: In this essay, I will examine two scholarly articles to find similarities and differences.

This statement is concise, but it is neither specific nor arguable—a reader might wonder, "Which scholarly articles? What is the topic of this paper? What field is the author writing in?" Additionally, the purpose of the paper—to "examine…to find similarities and differences" is not of a scholarly level. Identifying similarities and differences is a good first step, but strong academic argument goes further, analyzing what those similarities and differences might mean or imply.

Better: In this essay, I will argue that Bowler's (2003) autocratic management style, when coupled with Smith's (2007) theory of social cognition, can reduce the expenses associated with employee turnover.

The new revision here is still concise, as well as specific and arguable. We can see that it is specific because the writer is mentioning (a) concrete ideas and (b) exact authors. We can also gather the field (business) and the topic (management and employee turnover). The statement is arguable because the student goes beyond merely comparing; he or she draws conclusions from that comparison ("can reduce the expenses associated with employee turnover").

Making a Unique Argument

This thesis draft repeats the language of the writing prompt without making a unique argument:

Needs Improvement: The purpose of this essay is to monitor, assess, and evaluate an educational program for its strengths and weaknesses. Then, I will provide suggestions for improvement.

You can see here that the student has simply stated the paper's assignment, without articulating specifically how he or she will address it. The student can correct this error simply by phrasing the thesis statement as a specific answer to the assignment prompt.

Better: Through a series of student interviews, I found that Kennedy High School's antibullying program was ineffective. In order to address issues of conflict between students, I argue that Kennedy High School should embrace policies outlined by the California Department of Education (2010).

Words like "ineffective" and "argue" show here that the student has clearly thought through the assignment and analyzed the material; he or she is putting forth a specific and debatable position. The concrete information ("student interviews," "antibullying") further prepares the reader for the body of the paper and demonstrates how the student has addressed the assignment prompt without just restating that language.

Creating a Debate

This thesis statement includes only obvious fact or plot summary instead of argument:

Needs Improvement: Leadership is an important quality in nurse educators.

A good strategy to determine if your thesis statement is too broad (and therefore, not arguable) is to ask yourself, "Would a scholar in my field disagree with this point?" Here, we can see easily that no scholar is likely to argue that leadership is an unimportant quality in nurse educators. The student needs to come up with a more arguable claim, and probably a narrower one; remember that a short paper needs a more focused topic than a dissertation.

Better: Roderick's (2009) theory of participatory leadership is particularly appropriate to nurse educators working within the emergency medicine field, where students benefit most from collegial and kinesthetic learning.

Here, the student has identified a particular type of leadership ("participatory leadership"), narrowing the topic, and has made an arguable claim (this type of leadership is "appropriate" to a specific type of nurse educator). Conceivably, a scholar in the nursing field might disagree with this approach. The student's paper can now proceed, providing specific pieces of evidence to support the arguable central claim.

Choosing the Right Words

This thesis statement uses large or scholarly-sounding words that have no real substance:

Needs Improvement: Scholars should work to seize metacognitive outcomes by harnessing discipline-based networks to empower collaborative infrastructures.

There are many words in this sentence that may be buzzwords in the student's field or key terms taken from other texts, but together they do not communicate a clear, specific meaning. Sometimes students think scholarly writing means constructing complex sentences using special language, but actually it's usually a stronger choice to write clear, simple sentences. When in doubt, remember that your ideas should be complex, not your sentence structure.

Better: Ecologists should work to educate the U.S. public on conservation methods by making use of local and national green organizations to create a widespread communication plan.

Notice in the revision that the field is now clear (ecology), and the language has been made much more field-specific ("conservation methods," "green organizations"), so the reader is able to see concretely the ideas the student is communicating.

Leaving Room for Discussion

This thesis statement is not capable of development or advancement in the paper:

Needs Improvement: There are always alternatives to illegal drug use.

This sample thesis statement makes a claim, but it is not a claim that will sustain extended discussion. This claim is the type of claim that might be appropriate for the conclusion of a paper, but in the beginning of the paper, the student is left with nowhere to go. What further points can be made? If there are "always alternatives" to the problem the student is identifying, then why bother developing a paper around that claim? Ideally, a thesis statement should be complex enough to explore over the length of the entire paper.

Better: The most effective treatment plan for methamphetamine addiction may be a combination of pharmacological and cognitive therapy, as argued by Baker (2008), Smith (2009), and Xavier (2011).

In the revised thesis, you can see the student make a specific, debatable claim that has the potential to generate several pages' worth of discussion. When drafting a thesis statement, think about the questions your thesis statement will generate: What follow-up inquiries might a reader have? In the first example, there are almost no additional questions implied, but the revised example allows for a good deal more exploration.

Thesis Mad Libs

If you are having trouble getting started, try using the models below to generate a rough model of a thesis statement! These models are intended for drafting purposes only and should not appear in your final work.

- In this essay, I argue ____, using ______ to assert _____.

- While scholars have often argued ______, I argue______, because_______.

- Through an analysis of ______, I argue ______, which is important because_______.

Words to Avoid and to Embrace

When drafting your thesis statement, avoid words like explore, investigate, learn, compile, summarize , and explain to describe the main purpose of your paper. These words imply a paper that summarizes or "reports," rather than synthesizing and analyzing.

Instead of the terms above, try words like argue, critique, question , and interrogate . These more analytical words may help you begin strongly, by articulating a specific, critical, scholarly position.

Read Kayla's blog post for tips on taking a stand in a well-crafted thesis statement.

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Introductions

- Next Page: Conclusions

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

How to Write a Strong Thesis Statement: 4 Steps + Examples

What’s Covered:

What is the purpose of a thesis statement, writing a good thesis statement: 4 steps, common pitfalls to avoid, where to get your essay edited for free.

When you set out to write an essay, there has to be some kind of point to it, right? Otherwise, your essay would just be a big jumble of word salad that makes absolutely no sense. An essay needs a central point that ties into everything else. That main point is called a thesis statement, and it’s the core of any essay or research paper.

You may hear about Master degree candidates writing a thesis, and that is an entire paper–not to be confused with the thesis statement, which is typically one sentence that contains your paper’s focus.

Read on to learn more about thesis statements and how to write them. We’ve also included some solid examples for you to reference.

Typically the last sentence of your introductory paragraph, the thesis statement serves as the roadmap for your essay. When your reader gets to the thesis statement, they should have a clear outline of your main point, as well as the information you’ll be presenting in order to either prove or support your point.

The thesis statement should not be confused for a topic sentence , which is the first sentence of every paragraph in your essay. If you need help writing topic sentences, numerous resources are available. Topic sentences should go along with your thesis statement, though.

Since the thesis statement is the most important sentence of your entire essay or paper, it’s imperative that you get this part right. Otherwise, your paper will not have a good flow and will seem disjointed. That’s why it’s vital not to rush through developing one. It’s a methodical process with steps that you need to follow in order to create the best thesis statement possible.

Step 1: Decide what kind of paper you’re writing

When you’re assigned an essay, there are several different types you may get. Argumentative essays are designed to get the reader to agree with you on a topic. Informative or expository essays present information to the reader. Analytical essays offer up a point and then expand on it by analyzing relevant information. Thesis statements can look and sound different based on the type of paper you’re writing. For example:

- Argumentative: The United States needs a viable third political party to decrease bipartisanship, increase options, and help reduce corruption in government.

- Informative: The Libertarian party has thrown off elections before by gaining enough support in states to get on the ballot and by taking away crucial votes from candidates.

- Analytical: An analysis of past presidential elections shows that while third party votes may have been the minority, they did affect the outcome of the elections in 2020, 2016, and beyond.

Step 2: Figure out what point you want to make

Once you know what type of paper you’re writing, you then need to figure out the point you want to make with your thesis statement, and subsequently, your paper. In other words, you need to decide to answer a question about something, such as:

- What impact did reality TV have on American society?

- How has the musical Hamilton affected perception of American history?

- Why do I want to major in [chosen major here]?

If you have an argumentative essay, then you will be writing about an opinion. To make it easier, you may want to choose an opinion that you feel passionate about so that you’re writing about something that interests you. For example, if you have an interest in preserving the environment, you may want to choose a topic that relates to that.

If you’re writing your college essay and they ask why you want to attend that school, you may want to have a main point and back it up with information, something along the lines of:

“Attending Harvard University would benefit me both academically and professionally, as it would give me a strong knowledge base upon which to build my career, develop my network, and hopefully give me an advantage in my chosen field.”

Step 3: Determine what information you’ll use to back up your point

Once you have the point you want to make, you need to figure out how you plan to back it up throughout the rest of your essay. Without this information, it will be hard to either prove or argue the main point of your thesis statement. If you decide to write about the Hamilton example, you may decide to address any falsehoods that the writer put into the musical, such as:

“The musical Hamilton, while accurate in many ways, leaves out key parts of American history, presents a nationalist view of founding fathers, and downplays the racism of the times.”

Once you’ve written your initial working thesis statement, you’ll then need to get information to back that up. For example, the musical completely leaves out Benjamin Franklin, portrays the founding fathers in a nationalist way that is too complimentary, and shows Hamilton as a staunch abolitionist despite the fact that his family likely did own slaves.

Step 4: Revise and refine your thesis statement before you start writing

Read through your thesis statement several times before you begin to compose your full essay. You need to make sure the statement is ironclad, since it is the foundation of the entire paper. Edit it or have a peer review it for you to make sure everything makes sense and that you feel like you can truly write a paper on the topic. Once you’ve done that, you can then begin writing your paper.

When writing a thesis statement, there are some common pitfalls you should avoid so that your paper can be as solid as possible. Make sure you always edit the thesis statement before you do anything else. You also want to ensure that the thesis statement is clear and concise. Don’t make your reader hunt for your point. Finally, put your thesis statement at the end of the first paragraph and have your introduction flow toward that statement. Your reader will expect to find your statement in its traditional spot.

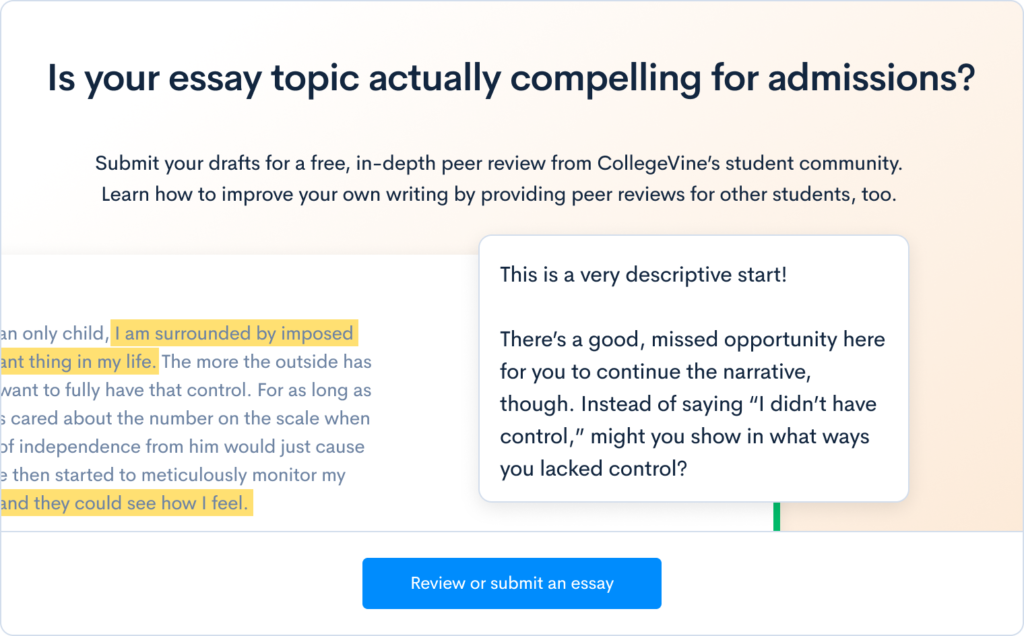

If you’re having trouble getting started, or need some guidance on your essay, there are tools available that can help you. CollegeVine offers a free peer essay review tool where one of your peers can read through your essay and provide you with valuable feedback. Getting essay feedback from a peer can help you wow your instructor or college admissions officer with an impactful essay that effectively illustrates your point.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a thesis statement + examples

What is a thesis statement?

Is a thesis statement a question, how do you write a good thesis statement, how do i know if my thesis statement is good, examples of thesis statements, helpful resources on how to write a thesis statement, frequently asked questions about writing a thesis statement, related articles.

A thesis statement is the main argument of your paper or thesis.

The thesis statement is one of the most important elements of any piece of academic writing . It is a brief statement of your paper’s main argument. Essentially, you are stating what you will be writing about.

You can see your thesis statement as an answer to a question. While it also contains the question, it should really give an answer to the question with new information and not just restate or reiterate it.

Your thesis statement is part of your introduction. Learn more about how to write a good thesis introduction in our introduction guide .

A thesis statement is not a question. A statement must be arguable and provable through evidence and analysis. While your thesis might stem from a research question, it should be in the form of a statement.

Tip: A thesis statement is typically 1-2 sentences. For a longer project like a thesis, the statement may be several sentences or a paragraph.

A good thesis statement needs to do the following:

- Condense the main idea of your thesis into one or two sentences.

- Answer your project’s main research question.

- Clearly state your position in relation to the topic .

- Make an argument that requires support or evidence.

Once you have written down a thesis statement, check if it fulfills the following criteria:

- Your statement needs to be provable by evidence. As an argument, a thesis statement needs to be debatable.

- Your statement needs to be precise. Do not give away too much information in the thesis statement and do not load it with unnecessary information.

- Your statement cannot say that one solution is simply right or simply wrong as a matter of fact. You should draw upon verified facts to persuade the reader of your solution, but you cannot just declare something as right or wrong.

As previously mentioned, your thesis statement should answer a question.

If the question is:

What do you think the City of New York should do to reduce traffic congestion?

A good thesis statement restates the question and answers it:

In this paper, I will argue that the City of New York should focus on providing exclusive lanes for public transport and adaptive traffic signals to reduce traffic congestion by the year 2035.

Here is another example. If the question is:

How can we end poverty?

A good thesis statement should give more than one solution to the problem in question:

In this paper, I will argue that introducing universal basic income can help reduce poverty and positively impact the way we work.

- The Writing Center of the University of North Carolina has a list of questions to ask to see if your thesis is strong .

A thesis statement is part of the introduction of your paper. It is usually found in the first or second paragraph to let the reader know your research purpose from the beginning.

In general, a thesis statement should have one or two sentences. But the length really depends on the overall length of your project. Take a look at our guide about the length of thesis statements for more insight on this topic.

Here is a list of Thesis Statement Examples that will help you understand better how to write them.

Every good essay should include a thesis statement as part of its introduction, no matter the academic level. Of course, if you are a high school student you are not expected to have the same type of thesis as a PhD student.

Here is a great YouTube tutorial showing How To Write An Essay: Thesis Statements .

- University of Pennsylvania

- School of Arts and Sciences

- Penn Calendar

Search form

On Thesis Statements

The thesis statement.

This is not an exhaustive list of bad thesis statements, but here're five kinds of problems I've seen most often. Notice that the last two, #4 and #5, are not necessarily incorrect or illegitimate thesis statements, but, rather, inappropriate for the purposes of this course. They may be useful forms for papers on different topics in other courses.

A thesis takes a position on an issue. It is different from a topic sentence in that a thesis statement is not neutral. It announces, in addition to the topic, the argument you want to make or the point you want to prove. This is your own opinion that you intend to back up. This is your reason and motivation for writing.

Bad Thesis 1

Bad Thesis 2 : This paper will consider the advantages and disadvantages of certain restrictions on free speech.

Better Thesis 1 : Stanley Fish's argument that free speech exists more as a political prize than as a legal reality ignores the fact that even as a political prize it still serves the social end of creating a general cultural atmosphere of tolerance that may ultimately promote free speech in our nation just as effectively as any binding law.

Better Thesis 2 : Even though there may be considerable advantages to restricting hate speech, the possibility of chilling open dialogue on crucial racial issues is too great and too high a price to pay.

A thesis should be as specific as possible, and it should be tailored to reflect the scope of the paper. It is not possible, for instance, to write about the history of English literature in a 5 page paper. In addition to choosing simply a smaller topic, strategies to narrow a thesis include specifying a method or perspective or delineating certain limits.

Bad Thesis 2 : The government has the right to limit free speech.

Better Thesis 1 : There should be no restrictions on the 1st amendment if those restrictions are intended merely to protect individuals from unspecified or otherwise unquantifiable or unverifiable "emotional distress."

Better Thesis 2 : The government has the right to limit free speech in cases of overtly racist or sexist language because our failure to address such abuses would effectively suggest that our society condones such ignorant and hateful views.

A thesis must be arguable. And in order for it to be arguable, it must present a view that someone might reasonably contest. Sometimes a thesis ultimately says, "we should be good," or "bad things are bad." Such thesis statements are tautological or so universally accepted that there is no need to prove the point.

Bad Thesis 2 : There are always alternatives to using racist speech.

Better Thesis 1 : If we can accept that emotional injuries can be just as painful as physical ones we should limit speech that may hurt people's feelings in ways similar to the way we limit speech that may lead directly to bodily harm.

Better Thesis 2 : The "fighting words" exception to free speech is not legitimate because it wrongly considers speech as an action.

A good argumentative thesis provides not only a position on an issue, but also suggests the structure of the paper. The thesis should allow the reader to imagine and anticipate the flow of the paper, in which a sequence of points logically prove the essay's main assertion. A list essay provides no such structure, so that different points and paragraphs appear arbitrary with no logical connection to one another.

Bad Thesis 2 : None of the arguments in favor of regulating pornography are persuasive.

Better Thesis 1 : Among the many reasons we need to limit hate speech the most compelling ones all refer to our history of discrimination and prejudice, and it is, ultimately, for the purpose of trying to repair our troubled racial society that we need hate speech legislation.

Better Thesis 2 : None of the arguments in favor of regulating pornography are persuasive because they all base their points on the unverifiable and questionable assumption that the producers of pornography necessarily harbor ill will specifically to women.

In an other course this would not be at all unacceptable, and, in fact, possibly even desirable. But in this kind of course, a thesis statement that makes a factual claim that can be verified only with scientific, sociological, psychological or other kind of experimental evidence is not appropriate. You need to construct a thesis that you are prepared to prove using the tools you have available, without having to consult the world's leading expert on the issue to provide you with a definitive judgment.

Bad Thesis 2 : Hate speech can cause emotional pain and suffering in victims just as intense as physical battery.

Better Thesis 1 : Whether or not the cultural concept of free speech bears any relation to the reality of 1st amendment legislation and jurisprudence, its continuing social function as a promoter of tolerance and intellectual exchange trumps the call for politicization (according to Fish's agenda) of the term.

Better Thesis 2 : The various arguments against the regulation of hate speech depend on the unspoken and unexamined assumption that emotional pain is either trivial.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Thesis Statement

A thesis is simply an expression of the main idea of what you are writing about. The thesis will be determined by the kind or genre of paper you are asked to write, but even a summary assignment—a paper in which you summarize the ideas of another writer without adding your thoughts—must have a thesis. A thesis for a summary would be your expression of the main idea of the work you are summarizing. The presence of a thesis, and paragraphs to support that thesis, is what distinguishes a summary from a list.

A thesis statement is a sentence that expresses the main claim of the entire essay. This means that every paragraph, every major point, every supporting detail, and every source must somehow relate to and support the thesis.

Essentially, when readers want to know what your point is, what they want to know is your thesis. And all college writing assignments expect you to make a point of some kind or another. This means that every one of your college essays should have a thesis. Some assignments emphasize argumentation more than others, so this need for a thesis might be less obvious to you in an essay that focuses more on reporting information, but it’s still there: your audience always expects you to make a point. An essay that has a good thesis has a good chance of succeeding. An essay that has a bad thesis, no matter what other strengths it may display, has a very poor chance of succeeding.

A common thesis statement is capable of being expressed in a single sentence. Much more information will be added to it in later sentences and paragraphs as support, but the primary idea itself will be focused and decisive enough to be stated in one sentence. However, there are times when a thesis statement should be multiple sentences, nevertheless, it should always be concise and clear.

A good thesis takes the form of a declarative sentence . This means that a good thesis is never a question. A question cannot state a point directly, but a thesis is a directly stated point, which means it won’t be a question but instead a possible answer to a question.

Three Characteristics of a Good Thesis

A good thesis statement has three characteristics:

- This means that it focuses on clearly defined ideas, often narrow enough to be discussed in a single essay. Within a thesis, referring to “sports” is not specific, but referring to “combat sports during the COVID-19 pandemic” is.

- This means that equally reasonable, intelligent, and educated readers could hold differing positions on the matter, and that the issues in the thesis can’t be answered with any kind of general certainty. “Bullying is bad” is not arguable for academic audiences, but what schools should do about bullying is. Keep in mind that arguable does not necessarily mean controversial. Academic arguments can be claims of analysis, observation, or other typically non-controversial modes. For example, a thesis claiming that “horror stories function through four primary motifs” is not controversial, but academically it is arguable. See more in the section Rhetoric and Argumentation.

- This means that it has some meaningful bearing on others and/or society. “I think Disney movies are terrible” is not significant, but exploring how “Disney movies have negatively affected the unrealistic worldview of children” is.

Common Errors: Bad Thesis Statements

It is possible for a thesis to be a single, declarative sentence yet still be bad. Often, this is because the thesis fails to display the three characteristics explained above. Here are some examples of bad thesis statements, along with brief explanations:

Bad Example 1: “Drugs have harmful effects on the community .”

Example 1 is bad because it is not specific. It does not indicate what drugs, specific effects, communities, or any other useful information.

Bad Example 2: “Racism should not be tolerated in school because it makes students feel alienated and harms the learning environment.”

Although Example 2 is specific and has good intentions, it is a bad thesis statement because it is not arguable. No one in a modern, rationally-minded audience would disagree and say that racism should be promoted in school. Therefore this thesis tells its readers what they already know, which makes it useless.

Bad Example 3: “Blue ink pens are better than black ink pens.”

Although Example 3 is specific and arguable, it is a bad thesis because it is not significant as is. Nobody cares, or at least it has no important effect on people’s lives or in society.

Good Thesis Statements

Now here are some good thesis statements with brief explanations.

“We should stop experimenting on animals and start experimenting on prisoners because the findings would be more accurate for humans and because prisoners aren’t innocent like animals are.”

This is highly arguable (you might disagree with it already), and that is a good thing: it is arguable while still being rationally able to defend itself (by offering at least two reasons as support). It is also good because it is very specific and because it is significant—it would matter whether America incorporates this idea.

“Divisions in America are getting worse because social media amplifies the voice of a minority of radicals, whom the majority of reasonable people are afraid to speak out against.”

This is a special type of thesis called a “causal analysis.” It argues why something is the way it is, and it is specific (it says exactly what and why), significant (it matters to many), and arguable (this might not be the reason, or at least not a main one—or it might be).

“The original iPhone was the most important invention in the past 20 years.”

Although this may be a bit challenging to support (because of the words “the most”), it is still a good thesis because it is arguable, it is specific (although the word “important” will have to be explained), and it would be significant if it proves to be a viable claim.

How to Build a Thesis

The way you build a thesis is to do the following in the order listed, making sure to use pre-writing strategies (whichever you prefer) to log your ideas each step of the way.

- Pick a broad subject that interests you.

- Pick some issue or controversy within that subject that interests you.

- Develop a guiding question about that issue or controversy, a question that is difficult or impossible for anyone to ever answer for certain.

(Warning: This is where lesser writers stop. They think this guiding question is what their essay is about—its thesis—but they are wrong because questions do not state points and cannot be argued. Do not stop here. Keep going until you have an actual thesis.)

- Make some sort of claim, comment, or point about that issue or controversy.

Improving the Thesis Statement

Early argument thesis statement.

People can’t seem to live without their phones, but spending that time online is detrimental.

- In bold we can see the writer’s opinion.

You’re already off to a good start: this thesis makes a claim, it demonstrates some knowledge or authority, and includes two sides to the issue. How can you make it better? Remember, you have to be able to write a paper in support of your thesis, so the more detailed, concrete, and developed your thesis is, the better. Here are a couple of suggestions for improving any thesis:

- Define your terms

- Develop the parts of your thesis so it answers as many who, what, when, where, how, and why questions as possible

Defining your terms

In your draft or working thesis above, are there any terms that would benefit from more definition? What do you mean by people , for example? Can that word be replaced with young people , teenagers, or young adults ? If you replaced people with these more specific terms, couldn’t you also then write your paper with more authority, as you are one of the people you’re writing about?

You might also define “can’t seem to live without,” which sounds good initially but is too general without explanation, with something more exact that appeals to your reader and can be supported with evidence or explained at greater length in your paragraphs: people “use their phones in the classrooms, at the dinner table, and even in restroom stalls.”

Teenagers and young adults seem to use their phones everywhere – in the classroom, at the dinner table, and even in restroom stalls , but spending that time online is detrimental.

- In bold we can see more definition and specificity in the terms.

Make sure your thesis statement answers questions

Your thesis is a snapshot or summary of your paper as a whole. Thus, you want your thesis to be something you can unfold or unpack or develop into a much longer work. And if your thesis makes a claim, that means it also answers a question. Thus, you want your thesis to answer or discuss the question as deeply and fully as possible. You can do this grammatically by adding prepositional phrases and “because” clauses that bring out the specifics of your thinking and tell your reader who, what, when, where, how, and/or why:

“Teenagers and young adults seem to use their phones everywhere—in the classroom, at the dinner table, even in restroom stalls— because they want to stay connected to their friends and peers at all times , but I think spending that much time online is detrimental to their social skills and mental health .”

Notice that this thesis, while not substantially different from the draft or working thesis you began with, has been substantially revised to be more specific, supported, and authoritative. It lays out an organized argument for a convincing paper. Because it is so complete and specific it can be easily changed if you find research that contradicts your claim or if you change your mind about the topic as you write and reflect:

“Teenagers and young adults seem to use their phones everywhere—in the classroom, at the dinner table, even in restroom stalls—because they want to stay connected to their friends and peers at all times, and research suggests that this connection has primarily positive psychological and emotional benefits .”

Teenagers and young adults seem to use their phones everywhere—in the classroom, at the dinner table, even in restroom stalls — because they want to stay connected to their friends and peers at all times , but spending that much time online is detrimental to their social skills and mental health.

- In italics we see the “who” and the “when/where.”

- In bold we can see the potential counterargument.

- Underlined we see points the writer will support to prove their point and make their argument. These can be referred to as a “roadmap.”

Common Errors

Although constructing a thesis according to the above characteristics and steps will help you avoid the biggest problems, it’s still possible to run into a few common errors.

One such error is confusing an essay’s subject with a thesis , which is a claim or position about that subject. This is particularly problematic when students focus on arguing for the existence of what they believe to be facts. Some are easy enough to identify and revise, such as “America still allows the death penalty in some places.” This does not yet take a position on that subject, but a student could easily enough reach one once this error is noticed. Others create more complicated problems. Consider these examples: “Aliens exist.” Or: “Ghosts are real.” These might seem to fit the characteristics of good thesis statements above, but they do not. That is because these are merely subjects for the writer. The writer who has asserted these as facts in the world has, by doing so, not yet claimed them and has failed to take a position on them. Such a position might be what the writer thinks universities or research institutions should do with their budgets based on evidence of the existence of aliens, or ghosts. But taking such positions and supporting them often becomes quite complex and shaky, especially when directed toward academic audiences, which is why these kinds of “secret facts about the universe” subjects are too problematic for student writers to handle successfully. Some professors simply ban them to help students avoid inevitable trouble.

Another such error is confusing a self-referential announcement with a thesis . This kind of announcement often looks something like, “My essay will be about…,” or, “I think that…,” or, “For this assignment, I will tell you about…,” or something in the essay that similarly refers to itself as an essay. Sometimes the revision is simple: eliminate the needless phrase. Consider this example: “I think that the teaching of Shakespeare should be banned in American schools.” As it stands, it is not a thesis because it is a simple announcement about the writer, but simply removing “I think that” makes it a thesis, for it then makes an arguable, specific, and significant claim that would need to be supported. In other cases, needless self-referential announcements such as “my essay will be about” hide the fact that the student has just confused the subject with a thesis, as noted above. So, “My essay will be about the death penalty” is only a subject, not yet a thesis.

Another common error is confusing the role of personal opinion in a thesis . Some students come to believe that personal opinions are banned in English class essays, or college writing in general, but this is self-evidently wrong. The only way to make a thesis arguable is to take some opinion-based position on a matter. Opinions are therefore required in constructing a good thesis. But the simple statement of a personal opinion is rarely sufficient for a thesis; instead, it often becomes a mere statement of taste, which is neither arguable nor significant. “I love pineapple on pizza, no matter what anyone else says,” is just a statement of personal opinion, which means it can’t be arguable, nor is it significant. “I hate that Americans only get two options when voting for president” is just a personal opinion as it stands, but this one has the potential for a good thesis with just a little more revision.