History of Research

- First Online: 24 March 2020

Cite this chapter

- Julie Hall 2

1526 Accesses

Current clinical practice must be evidence-based. Evidence should, ideally, be based on research findings. A research process allows practitioners to justify existing practice and to develop new areas of practice. Practitioners involved in research must employ methodologies that are appropriate for the issue that they wish to address. They must also acknowledge the assumptions upon which their choice of methodology is based. Whatever research approach is chosen, the process must be transparent, rigorous, and systematic.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

SCoR. Education and professional development strategy: new directions. 2010.

Google Scholar

Harré R. The philosophies of science. London: Oxford University Press; 1972.

Peltonen M, editor. The Cambridge companion to bacon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996.

Cassirer E. The philosophy of the enlightenment. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1968.

Kuhn TS. The structure of scientific revolutions. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1970.

Feyerabend P. Against method. 3rd ed. London: New Left Books; 1975.

Jarvis P, Holford J, Griffin C. The theory and practice of learning. 2nd ed. London: Kogan Page; 2003.

Book Google Scholar

Parahoo K. Nursing research: principles, process and issues. 3rd ed. London: Macmillan; 2014.

Miller S. Analysis of phenomenological data generated with children as research participants. Nurse Res. 2003;10:70–3.

Article Google Scholar

Glaser B, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson; 1967.

Jolley J. Introducing research and evidence-based practice for nursing and healthcare professionals. 2nd ed. London: Taylor & Francis; 2013.

Van Dijk TA, Kintsch W. Strategies of discourse comprehension. London: Academic; 1983.

Habermas J. Knowledge and human interests. London: Heinemann; 1972. p. 209.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/reviews . Accessed 27 June 2019.

Swee-Lin Tan S, Goonawardene N. Internet health information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(1):e9.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Radiography, Birmingham City University, Birmingham, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Julie Hall .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Diagnostic Radiography and Imaging, School of Health and Social Work, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, Hertfordshire, UK

Aarthi Ramlaul

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Hall, J. (2020). History of Research. In: Ramlaul, A. (eds) Medical Imaging and Radiotherapy Research: Skills and Strategies. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37944-5_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37944-5_1

Published : 24 March 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-37943-8

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-37944-5

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- University of Wisconsin–Madison

- University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Research Guides

- Introduction to Historical Research

Introduction to Historical Research : Home

- Archival sources

- Multimedia sources

- Newspapers and other periodicals

- Biographical Information

- Government documents

Subject-Specialist Librarians

There are librarians on campus that can help you with your specific area of research.

Subject Librarian Directory Subject-specialist/ liaison librarians are willing to help you with anything from coming up with research strategies to locating sources.

Ask a Librarian

or click for more options ...

This guide is an introduction to selected resources available for historical research. It covers both primary sources (such as diaries, letters, newspaper articles, photographs, government documents and first-hand accounts) and secondary materials (such as books and articles written by historians and devoted to the analysis and interpretation of historical events and evidence).

"Research in history involves developing an understanding of the past through the examination and interpretation of evidence. Evidence may exist in the form of texts, physical remains of historic sites, recorded data, pictures, maps, artifacts, and so on. The historian’s job is to find evidence, analyze its content and biases, corroborate it with further evidence, and use that evidence to develop an interpretation of past events that holds some significance for the present.

Historians use libraries to

- locate primary sources (first-hand information such as diaries, letters, and original documents) for evidence

- find secondary sources (historians’ interpretations and analyses of historical evidence)

- verify factual material as inconsistencies arise"

( Research and Documentation in the Electronic Age, Fifth Edition, by Diana Hacker and Barbara Fister, Bedford/St. Martin, 2010)

This guide is meant to help you work through these steps.

Other helpful guides

This is a list of other historical research guides you may find helpful:

- Learning Historical Research Learning to Do Historical Research: A Primer for Environmental Historians and Others by William Cronon and his students, University of Wisconsin A website designed as a basic introduction to historical research for anyone and everyone who is interested in exploring the past.

- Reading, Writing, and Researching for History: A Guide for College Students by Patrick Rael, Bowdoin College Guide to all aspects of historical scholarship—from reading a history book to doing primary source research to writing a history paper.

- Writing Historical Essays: A Guide for Undergraduates Rutgers History Department guide to writing historical essays

- History Study Guides History study guides created by the Carleton College History Department

- Next: Books >>

- Last Updated: Mar 4, 2024 12:48 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.wisc.edu/introhist

The Princeton Guide to Historical Research

- Zachary Schrag

50% off with code FIFTY

Before you purchase audiobooks and ebooks

Please note that audiobooks and ebooks purchased from this site must be accessed on the Princeton University Press app. After you make your purchase, you will receive an email with instructions on how to download the app. Learn more about audio and ebooks .

Support your local independent bookstore.

- United States

- United Kingdom

The essential handbook for doing historical research in the twenty-first century

- Skills for Scholars

- Look Inside

- Request Exam Copy

- Download Cover

The Princeton Guide to Historical Research provides students, scholars, and professionals with the skills they need to practice the historian’s craft in the digital age, while never losing sight of the fundamental values and techniques that have defined historical scholarship for centuries. Zachary Schrag begins by explaining how to ask good questions and then guides readers step-by-step through all phases of historical research, from narrowing a topic and locating sources to taking notes, crafting a narrative, and connecting one’s work to existing scholarship. He shows how researchers extract knowledge from the widest range of sources, such as government documents, newspapers, unpublished manuscripts, images, interviews, and datasets. He demonstrates how to use archives and libraries, read sources critically, present claims supported by evidence, tell compelling stories, and much more. Featuring a wealth of examples that illustrate the methods used by seasoned experts, The Princeton Guide to Historical Research reveals that, however varied the subject matter and sources, historians share basic tools in the quest to understand people and the choices they made.

- Offers practical step-by-step guidance on how to do historical research, taking readers from initial questions to final publication

- Connects new digital technologies to the traditional skills of the historian

- Draws on hundreds of examples from a broad range of historical topics and approaches

- Shares tips for researchers at every skill level

Skills for Scholars: The new tools of the trade

Awards and recognition.

- Winner of the James Harvey Robinson Prize, American Historical Association

- A Choice Outstanding Academic Title of the Year

- Introduction: History Is for Everyone

- History Is the Study of People and the Choices They Made

- History Is a Means to Understand Today’s World

- History Combines Storytelling and Analysis

- History Is an Ongoing Debate

- Autobiography

- Everything Has a History

- Narrative Expansion

- From the Source

- Public History

- Research Agenda

- Factual Questions

- Interpretive Questions

- Opposing Forces

- Internal Contradictions

- Competing Priorities

- Determining Factors

- Hidden or Contested Meanings

- Before and After

- Dialectics Create Questions, Not Answers

- Copy Other Works

- History Big and Small

- Pick Your People

- Add and Subtract

- Narrative versus Thematic Schemes

- The Balky Time Machine

- Local and Regional

- Transnational and Global

- Comparative

- What Is New about Your Approach?

- Are You Working in a Specific Theoretical Tradition?

- What Have Others Written?

- Are Others Working on It?

- What Might Your Critics Say?

- Primary versus Secondary Sources

- Balancing Your Use of Secondary Sources

- Sets of Sources

- Sources as Records of the Powerful

- No Source Speaks for Itself

- Languages and Specialized Reading

- Choose Sources That You Love

- Workaday Documents

- Specialized Periodicals

- Criminal Investigations and Trials

- Official Reports

- Letters and Petitions

- Institutional Records

- Scholarship

- Motion Pictures and Recordings

- Buildings and Plans

- The Working Bibliography

- The Open Web

- Limits of the Open Web

- Bibliographic Databases

- Full-Text Databases

- Oral History

- What Is an Archive?

- Archives and Access

- Read the Finding Aid

- Follow the Rules

- Work with Archivists

- Types of Cameras

- How Much to Shoot?

- Managing Expectations

- Duck, Duck, Goose

- Credibility

- Avoid Catastrophe

- Complete Tasks—Ideally Just Once, and in the Right Order

- Maintain Momentum

- Kinds of Software

- Word Processors

- Means of Entry

- A Good Day’s Work

- Word Count Is Your Friend

- Managing Research Assistants

- Research Diary

- When to Stop

- Note-Taking as Mining

- Note-Taking as Assembly

- Identify the Source, So You Can Go Back and Consult if Needed

- Distinguish Others’ Words and Ideas from Your Own

- Allow Sorting and Retrieval of Related Pieces of Information

- Provide the Right Level of Detail

- Notebooks and Index Cards

- Word Processors for Note-Taking

- Plain Text and Markdown

- Reference Managers

- Note-Taking Apps

- Relational Databases

- Spreadsheets

- Glossaries and Alphabetical Lists

- Image Catalogs

- Other Specialized Formats

- The Working Draft

- Variants: The Ten- and Thirty-Page Papers

- Thesis Statement

- Historiography

- Sections as Independent Essays

- Topic Sentences

- Answering Questions

- Invisible Bullet Points

- The Perils of Policy Prescriptions

- A Model (T) Outline

- Flexibility

- Protagonists

- Antagonists

- Bit Players

- The Shape of the Story

- The Controlling Idea

- Alchemy: Turning Sources to Stories

- Turning Points

- Counterfactuals

- Point of View

- Symbolic Details

- Combinations

- Speculation

- Is Your Jargon Really Necessary?

- Defining Terms

- Word Choice as Analysis

- Period Vocabulary or Anachronism?

- Integrate Images into Your Story

- Put Numbers in Context

- Summarize Data in Tables and Graphs

- Why We Cite

- Citation Styles

- Active Verbs

- People as Subjects

- Signposting

- First Person

- Putting It Aside

- Reverse Outlining

- Auditing Your Word Budget

- Writing for the Ear

- Conferences

- Social Media

- Coauthorship

- Tough, Fair, and Encouraging

- Manuscript and Book Reviews

- Journal Articles

- Book chapters

- Websites and Social Media

- Museums and Historic Sites

- Press Appearances and Op-Eds

- Law and Policy

- Graphic History, Movies, and Broadway Musicals

- Acknowledgments

"This volume is a complete and sophisticated addition to any scholar’s library and a boon to the curious layperson. . . . [A] major achievement."— Choice Reviews

"This book is quite simply a gem. . . . Schrag’s accessible style and comprehensive treatment of the field make this book a valuable resource."—Alan Sears, Canadian Journal of History

"A tour de force that will help all of us be more capable historians. This wholly readable, delightful book is packed with good advice that will benefit seasoned scholars and novice researchers alike."—Nancy Weiss Malkiel, author of "Keep the Damned Women Out": The Struggle for Coeducation

"An essential and overdue contribution. Schrag's guide offers a lucid breakdown of what historians do and provides plenty of examples."—Jessica Mack, Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, George Mason University

"Extraordinarily useful. If there is another book that takes apart as many elements of the historian's craft the way that Schrag does and provides so many examples, I am not aware of it."—James Goodman, author of But Where Is the Lamb?

"This is an engaging guide to being a good historian and all that entails."—Diana Seave Greenwald, Assistant Curator of the Collection, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

"Impressive and engaging. Schrag gracefully incorporates the voices of dozens, if not hundreds, of fellow historians. This gives the book a welcome conversational feeling, as if the reader were overhearing a lively discussion among friendly historians."—Sarah Dry, author of Waters of the World: The Story of the Scientists Who Unraveled the Mysteries of Our Oceans, Atmosphere, and Ice Sheets and Made the Planet Whole

"This is a breathtaking book—wide-ranging, wonderfully written, and extremely useful. Every page brims with fascinating, well-chosen illustrations of creative research, writing, and reasoning that teach and inspire."—Amy C. Offner, author of Sorting Out the Mixed Economy

historyprofessor.org website, maintained by Zachary M. Schrag, Professor of History at George Mason University

Stay connected for new books and special offers. Subscribe to receive a welcome discount for your next order.

50% off sitewide with code FIFTY | May 7 – 31 | Some exclusions apply. See our FAQ .

- ebook & Audiobook Cart

Search form

Cuneiform commentaries project.

- About the Project

- Citation guidelines

- The CCP Numbers

- History of the Genre

- Typology of the Commentaries

- Hermeneutic Techniques

- Sources of the Commentaries

- Technical terms and signs

- Cities and Libraries

History of Research

- Akkadian and Hebrew Exegesis

- Complete Bibliography

- Basic Bibliography

- Literary Prayer to Marduk 2

- Literary Others

- Udughul, Marduk’s address

- Šurpu, Maqlû, Tummu bītu

- Astrological. Enūma Anu Enlil

- Astrological. Sîn ina tāmartīšu

- Astrological Miscelanea

- Extispicy (Bārûtu)

- Terrestrial omens (Šumma Ālu)

- Teratological Omens

- Physiognomic

- Divination Other / Uncertain

- Diagnostic and prognostic

- Therapeutic texts

- Medical Other / Uncertain

- Laws of Hammurapi

- Lion's Blood

- Grammatical texts

- Lexical Other

- Proper Nouns

You are here

This page reviews the history of research on Mesopotamian commentaries, from the earliest publications in the late 19 th century to the Cuneiform Commentaries Project . 1

Early History of Research

The first publications of cuneiform commentaries appeared in the foundational period of Assyriology. As early as 1866, E. Norris provided in 2 R , 44 (no. 7) CCP 3.1.u73 and 47 CCP 3.1.u72 autographs of two Nineveh commentaries, one astrological, the other commenting on several different texts. However, cuneiform studies were at that time still so much in their infancy that Norris, unaware of what the texts actually represented, characterized them simply as bilingual lists. Progress in the analysis of the genre was slow. But when C. Bezold, between 1889 and 1899, published his catalogue of cuneiform tablets found by the British excavators at Nineveh, he was already able to distinguish in his index a large number of “commentaries” from texts that were merely “explanatory lists” ( Bezold, 1889/1899 C. Bezold , Catalogue of the Cuneiform Tablets in the Kouyunjik Collection of the British Museum. Vol. I-V . British Museum Press, 1889. : 2098-2100). In an introductory work on Babylonian and Assyrian culture from 1903, Bezold C. Bezold , Ninive und Babylon . Velhagen & Klasing, 1903. “Besondere Hervorhebung verdienen ... die Kommentare ... Man hat solche Kommentare zu einigen Tafeln einer Serie von Omentexten und zu mehreren Stücken des großen alten astrologischen Werkes ... gefunden. Da von diesen Stücken selbst noch mehrere Fragmente in der Bibliothek [Assurbanipals] erhalten sind, so läßt sich nun Zeile für Zeile des Textes mit dem Kommentar vergleichen und ersehen, mit welchen Schwierigkeiten schon 2600 Jahre vor unserer Zeit die berufsmäßigen Erklärer jener alten astrologischen Sammlungen zu kämpfen hatten. Auch einige religiöse Texte wurden von den Assyrern mit erläuternden Bemerkungen versehen und zwar in der Weise, daß nur gelegentlich ein einzelnes Wort oder ein selteneres Wortzeichen eine Erklärung erhält, ähnlich wie das heute noch in den Bemerkungen zu unseren Schulausgaben der alten Klassiker geschieht” (Bezold, 1903: 136-37). also provided one of the earliest brief general descriptions of the genre. Another significant step forward was made when L. W. King, in his book on the Babylonian Epic of Creation, presented a full edition of an important text commentary alongside the text to which it referred ( King, 1902 L. W. King , The Seven Tablets of Creation. Or the Babylonian and Assyrian Legends Concerning the Creation of the World and of Mankind . Luzac, 1902. : 157-75). Additional autograph copies of commentaries, both from Nineveh and from Babylonian cities, were published in subsequent decades by C. Virolleaud ( ACh , 1905-1912 C. Virolleaud , L'Astrologie Chaldéenne: le livre intitulé "Enuma (Anu) ilu.Bel" . Librairie Paul Gauthner, 1910. ), T. Meek ( 1920 T. J. Meek , “ Some Explanatory Lists and Grammatical Texts ” , Revue d'Assyriologie , vol. 17, pp. 117-206, 1920. ), C. J. Gadd ( CT 41 = Gadd, 1931 C. J. Gadd , Cuneiform Texts from Babylonian Tablets in the British Museum. Part XLI . British Museum Press, 1931. : nos. 25-50), and many others.

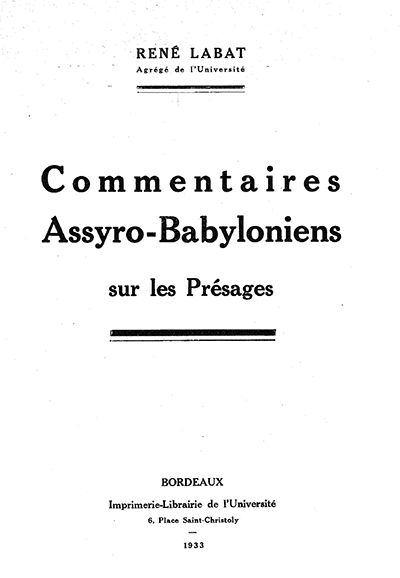

Labat’s Commentaires

Gadd’s CT volume inspired what until 2011 remained the only monographic treatment of Mesopotamian text commentaries, R. Labat’s Commentaires assyro-babyloniens sur les presages ( Labat, 1933 R. Labat , Commentaires assyro-babyloniens sur les présages . Imprimerie-Librairie de l’Université, 1933. ), a book that offers editions of altogether twenty-two commentaries as well as an introduction that attempts to define the genre. Labat’s work deserves praise because of its pioneering character and many valuable insights, but its usefulness is limited by the small number of commentaries considered. Moreover, some of the author’s conclusions seem unjustified. When Labat claims, for example, that the commentaries “manifestent très rarement un effort intelligent d’interprétation” ( Labat, 1933 R. Labat , Commentaires assyro-babyloniens sur les présages . Imprimerie-Librairie de l’Université, 1933. : 22), his judgement may reflect more of the author’s own ability to understand the commentaries than their actual exegetical potential.

The Modern Era

With the exception of J. Krecher’s useful but brief entry on “Kommentare” in RlA 6 ( Krecher, 1980/1983 J. Krecher , “ Kommentare ” , Reallexikon der Assyriologie , vol. 6, pp. 188-191, 1980. Like Labat, Krecher pays comparatively little attention to the vast body of mukallimtu -commentaries on astrological and extispicy texts. ), there have been no comprehensive treatments of Mesopotamian commentaries since Labat’s book, but several important studies of individual commentaries and commentary groups have appeared. The number of commentaries available in form of autographs or editions has radically increased over the past decades, with the series Spätbabylonische Texte aus Uruk , authored by H. Hunger H. Hunger , Spätbabylonische Texte aus Uruk. Teil I . Gebr. Mann Verlag, 1976. and E. von Weiher E. von Weiher , Spätbabylonische Texte aus Uruk. Teil II . Gebr. Mann Verlag, 1983. E. von Weiher , Spätbabylonische Texte aus Uruk. Teil III . Gebr. Mann Verlag, 1988. E. von Weiher , Spätbabylonische Texte aus dem Planquadrat U 18 . Gebr. Mann Verlag, 1993. E. von Weiher , Spätbabylonische Texte aus dem Planquadrat U 18 . Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1998. and a number of publications by U. Koch(-Westenholz) ( 1999 U. Koch-Westenholz , “ The Astrological Commentary Šumma Sîn ina tāmartīšu Tablet 1 ” , Res Orientales , vol. 12, pp. 149-165, 1999. , 2000b U. Koch-Westenholz , Babylonian Liver Omens. The Chapters Manzāzu, Padānu and Pān Tākalti of the Babylonian Extispicy Series mainly from Aššurbanipal's Library . Museum Tusculanum, 2000. , 2005 U. S. Koch , Secrets of Extispicy. The Chapter Multābiltu of the Babylonian Extispicy Series and Niṣirti bārûti Texts mainly from Aššurbanipal's Library . Ugarit-Verlag, 2005. ) providing the bulk of the new material In addition, many astrological commentaries have been published in the BPO volumes authored by E. Reiner and D. Pingree: E. Reiner and Pingree, D. , Babylonian Planetary Omens. Part Two. Enūma Anu Enlil Tablets 50-51 . Undena Publications, 1985. E. Reiner and Pingree, D. , Babylonian Planetary Omens. Part Three . Styx, 1998. E. Reiner and Pingree, D. , Babylonian Planetary Omens. Part Four . Brill, Styx, 2005. . Particular attention has been paid to the hermeneutical techniques used in the commentaries ( Civil, 1974a M. Civil , “ Medical Commentaries from Nippur ” , Journal of Near Eastern Studies , vol. 33, pp. 329-338, 1974. , Cavigneaux, 1976 A. Cavigneaux , Die sumerisch-akkadischen Zeichenlisten. Überlieferungsprobleme . PhD thesis, 1976. : 151-160, Bottéro, 1977 J. Bottéro , “ Les noms de Marduk, l'écriture et la 'logique' en Mésopotamie Ancienne ” , in Essays on the Ancient Near East in memory of Jacob Joel Finkelstein , deJ. M. Ellis, Ed. Archon Books, 1977, pp. 5-28. , Cavigneaux, 1987 A. Cavigneaux , “ Aux sources du Midrash: L'herméneutique babylonienne ” , Aula Orientalis , vol. 5, pp. 243-255, 1987. , Limet, 1982 H. Limet , “ De la philologie à la mystique en Babylonie ” , in Studia Paulo Naster oblata II: Orientalia Antiqua , J. Quaergebeur, Ed. Peeters, 1982. , George, 1991 A. R. George , “ Babylonian Texts from the folios of Sidney Smith. Part Two: Prognostic and Diagnostic Omens, Tablet I ” , Revue d'Assyriologie , vol. 85, pp. 137-167, 1991. , Hunger, 1995 H. Hunger , “ Ein Kommentar zu Mond-Omina ” , in Vom Alten Orient zum Alten Testament. Festschrift für Wolfram Freiherrn von Soden zum 85. Geburtstag am 19. Juni 1993 , W. Dietrich and Loretz, O. , Eds. Butzon & Kevelaer, 1995, pp. 105-118. , Seminara, 2001 S. Seminara , La versione accadica del Lugal-e. La tecnica babilonese della traduzione dal sumerico e le sue "regole" . Dipartimento di Studi Orientali, 2001. : 546-48), and some authors have compared these techniques to those employed in rabbinical exegesis ( Lambert, 1954/1956 W. G. Lambert , “ An Address of Marduk to the Demons ” , Archiv für Orientforschung , vol. 17, pp. 310-321, 1954. : 311, Cavigneaux, 1987 A. Cavigneaux , “ Aux sources du Midrash: L'herméneutique babylonienne ” , Aula Orientalis , vol. 5, pp. 243-255, 1987. , Lieberman, 1987 S. J. Lieberman , “ A Mesopotamian Background for the So-Called Aggadic 'Measures' of Biblical Hermeneutics? ” , Hebrew Union College Annual , vol. 58, pp. 157-225, 1987. ). Less work has been done to illuminate the socio-cultural context of the commentaries ( Meier, 1937/1939b G. Meier , “ Kommentare aus dem Archiv der Tempelschule in Assur ” , Archiv für Orientforschung , vol. 12, pp. 237-246, 1937. and 1942 G. Meier , “ Ein Kommentar zu einer Selbstprädikation des Marduk aus Assur ” , Zeitschrift für Assyriologie , vol. 47, pp. 241-246, 1942. , George, 1991 A. R. George , “ Babylonian Texts from the folios of Sidney Smith. Part Two: Prognostic and Diagnostic Omens, Tablet I ” , Revue d'Assyriologie , vol. 85, pp. 137-167, 1991. , Frahm, 2004 E. Frahm , “ Royal Hermeneutics: Observations on the Commentaries from Ashurbanipal's Libraries at Nineveh ” , Iraq , vol. 66, pp. 45-50, 2004. ), but a number of studies of the milieu in which first millennium Babylonian and Assyrian scribes operated have paved the ground to tackle this issue in greater depth ( Parpola, 1983b S. Parpola , Letters from Assyrian Scholars to the Kings Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal, Part II: Commentary and Appendices . Butzon & Bercker, 1983. , Pongratz-Leisten, 1999 B. Pongratz-Leisten , Herrschaftwissen in Mesopotamien. Formen der Kommunikation zwischen Gott und König im 2. und 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr. The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project, 1999. , Brown, 2000 D. Brown , Mesopotamian Planetary Astronomy-Astrology . Styx, 2000. , Frahm, 2002 E. Frahm , “ Zwischen Tradition und Neuerung: Babylonische Priestergelehrte im achämenidenzeitlichen Uruk ” , in Religion und Religionskontakte im Zeitalter der Achämeniden , R. G. Kratz, Ed. Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 2002, pp. 74-108. , Clancier, 2009 P. Clancier , Les bibliothèques en Babylonie dans le deuxième moitié du 1er millénaire av. J.-C. Ugarit-Verlag, 2009. ). Our understanding of the emergence of canonical texts in Mesopotamia, a phenomenon intimately linked to the birth of the commentary, has also received considerable attention in the past years ( Rochberg-Halton, 1984 F. Rochberg , “ Canonicity in Cuneiform Texts ” , Journal of Cuneiform Studies , vol. 36, pp. 127-144, 1984. , Finkel, 1988 I. L. Finkel , “ Adad-apla-iddina, Esagil-kin-apli, and the series SA.GIG ” , in A scientific humanist: studies in memory of Abraham Sachs , E. Liechty, Ellis, MdeJ. , Gerardi, P. , and Gingerich, O. , Eds. University Museum, 1988, pp. 143-159. , Veldhuis 2003 N. Veldhuis , “ Mesopotamian Canons ” , in Homer, the Bible, and Beyond. Literary and Religious Canons in the Ancient World , M. Finkelberg and Stroumsa, G. G. , Eds. Brill, 2003. , Heeßel, 2010a N. P. Heeßel , “ Neues von Esagil-kīn-apli. Die ältere Version der physiognomischen Omenserie alamdimmû ” , in Assur-Forschungen. Arbeiten aus der Forschungsstelle »Edition literarischer Keilschrifttexte aus Assur« der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften , S. M. Maul and Heeßel, N. P. , Eds. Harrassowitz, 2010, pp. 139-187. ).

Because no synthesis of the information gathered in these studies is available at present, recent works that analyze the history and typology of the commentary from a multi-disciplinary perspective have paid little attention to commentaries from Babylonia and Assyria. Assmann & Gladigow, 1995 J. Assmann and Gladigow, B. , Text und Kommentar . Fink, 1995. , the broadest and intellectually most stimulating recent treatment of the commentary tradition, with discussions of exegetical texts from Egypt, the classical world, Jewish, Christian, and Islamic tradition, India, China, and the West, ignores them altogether. Most, 1999 G. W. Most , Commentaries - Kommentare . 1999. includes an important article on cuneiform “etymography” by Maul S. M. Maul , “ Das Wort im Worte, Orthographie und Etymologie als hermeneutische Verfahren babylonischer Gelehrter ” , in Commentaries/Kommentare , G. W. Most, Ed. Göttingen: , 1999, pp. 1-18. , but it, too, fails to discuss the cuneiform commentaries.

Frahm’s Origins and the Cuneiform Commentaries Project

It took several more years, however, before the first comprehensive study of the corpus appeared. In 2011, Eckart Frahm, the Principal Investigator of the Cuneiform Commentaries Project , published his monograph Babylonian and Assyrian Text Commentaries: Origins of Interpretation , in the series Guides to the Mesopotamian Textual Record (Münster). The book, based on several years of research, provides a complete catalog of nearly 900 cuneiform commentaries scattered among museums and private collections around the world, discusses the scribes who copied and collected them, and analyzes the principal hermeneutical techniques, their self-designations, and their intertextual references.

Frahm’s study did not aim to publish large numbers of commentaries. In fact, it presents only two commentaries, one from Assyria ( Frahm, 2011 E. Frahm , Babylonian and Assyrian Text Commentaries. Origins of Interpretation . Ugarit-Verlag, 2011. : 384-396) and one from Babylonia ( Frahm, 2011 E. Frahm , Babylonian and Assyrian Text Commentaries. Origins of Interpretation . Ugarit-Verlag, 2011. : 396-404), in complete, annotated editions. But with its comprehensive catalog, the book provided a starting point for the more ambitious goal of editing all the commentaries in full, including those that have never been properly studied before. 2 Important studies on Mesopotamian commentaries have appeared after the publication of this monograph, especially Gabbay, 2012 U. Gabbay , “ Akkadian Commentaries from Ancient Mesopotamia and Their Relation to Early Hebrew Exegesis ” , Dead Sea Discoveries , vol. 19, pp. 267-312, 2012. and Gabbay, 2014 U. Gabbay , “ Actual Sense and Scriptural Intention: Literal Meaning and Its Terminology in Akkadian and Hebrew Commentaries ” , in Encounters by the Rivers of Babylon: Scholarly Conversations between Jews, Iranians, and Babylonians , U. Gabbay and Secunda, S. , Eds. Mohr Siebeck, 2014, pp. 335-370. .

The main goal of the Cuneiform Commentaries Project is to provide full editions of all known text commentaries from ancient Mesopotamia. As outlined in the section About the Project , the project started in Fall 2013. Eckart Frahm, Principal Investigator, and Enrique Jiménez, Postdoctoral Associate, have created an electronic database of all known commentaries and built a searchable website that makes the database available to a global audience. In cooperation with the Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus ( Oracc ), Frahm and Jiménez have also created online editions of several dozen commentary tablets and fragments. The available editions (50 as of January 2015) are accessible in the section Catalog of Commentaries . Editions of all remaining texts will be prepared and made available on the project’s website during the next few years.

- 1. The first paragraphs of this page have been adapted from E. Frahm , Babylonian and Assyrian Text Commentaries. Origins of Interpretation . Ugarit-Verlag, 2011. Pp. 4-6

- 2. Published reviews of E. Frahm’s Babylonian and Assyrian Text Commentaries: Origins of Interpretation include: Couto, 2013 É. Couto , “ Review of Frahm Babylonian and Assyrian Text Commentaries (GMTR 5) ” , Historiae , vol. 10, pp. 149-150, 2013. , Gertz, 2012 J. C. Gertz , “ Review of Frahm Babylonian and Assyrian Text Commentaries (GMTR 5) ” , Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft , vol. 124, pp. 137-138, 2012. , Glassner, In Press J. - J. Glassner , “ Review of Frahm Babylonian and Assyrian Text Commentaries (GMTR 5) ” , Archiv für Orientforschung , vol. 53, pp. 137-138, Submitted. , and Livingstone, 2012 A. Livingstone , “ Review of Frahm Babylonian and Assyrian Text Commentaries (GMTR 5) ” , Theologische Literaturzeitung , vol. 137, pp. 1179–1180, 2012. .

- Privacy Policy

Home » Historical Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Historical Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Table of Contents

Historical Research

Definition:

Historical research is the process of investigating and studying past events, people, and societies using a variety of sources and methods. This type of research aims to reconstruct and interpret the past based on the available evidence.

Types of Historical Research

There are several types of historical research, including:

Descriptive Research

This type of historical research focuses on describing events, people, or cultures in detail. It can involve examining artifacts, documents, or other sources of information to create a detailed account of what happened or existed.

Analytical Research

This type of historical research aims to explain why events, people, or cultures occurred in a certain way. It involves analyzing data to identify patterns, causes, and effects, and making interpretations based on this analysis.

Comparative Research

This type of historical research involves comparing two or more events, people, or cultures to identify similarities and differences. This can help researchers understand the unique characteristics of each and how they interacted with each other.

Interpretive Research

This type of historical research focuses on interpreting the meaning of past events, people, or cultures. It can involve analyzing cultural symbols, beliefs, and practices to understand their significance in a particular historical context.

Quantitative Research

This type of historical research involves using statistical methods to analyze historical data. It can involve examining demographic information, economic indicators, or other quantitative data to identify patterns and trends.

Qualitative Research

This type of historical research involves examining non-numerical data such as personal accounts, letters, or diaries. It can provide insights into the experiences and perspectives of individuals during a particular historical period.

Data Collection Methods

Data Collection Methods are as follows:

- Archival research : This involves analyzing documents and records that have been preserved over time, such as government records, diaries, letters, newspapers, and photographs. Archival research is often conducted in libraries, archives, and museums.

- Oral history : This involves conducting interviews with individuals who have lived through a particular historical period or event. Oral history can provide a unique perspective on past events and can help to fill gaps in the historical record.

- Artifact analysis: This involves examining physical objects from the past, such as tools, clothing, and artwork, to gain insights into past cultures and practices.

- Secondary sources: This involves analyzing published works, such as books, articles, and academic papers, that discuss past events and cultures. Secondary sources can provide context and insights into the historical period being studied.

- Statistical analysis : This involves analyzing numerical data from the past, such as census records or economic data, to identify patterns and trends.

- Fieldwork : This involves conducting on-site research in a particular location, such as visiting a historical site or conducting ethnographic research in a particular community. Fieldwork can provide a firsthand understanding of the culture and environment being studied.

- Content analysis: This involves analyzing the content of media from the past, such as films, television programs, and advertisements, to gain insights into cultural attitudes and beliefs.

Data Analysis Methods

- Content analysis : This involves analyzing the content of written or visual material, such as books, newspapers, or photographs, to identify patterns and themes. Content analysis can be used to identify changes in cultural values and beliefs over time.

- Textual analysis : This involves analyzing written texts, such as letters or diaries, to understand the experiences and perspectives of individuals during a particular historical period. Textual analysis can provide insights into how people lived and thought in the past.

- Discourse analysis : This involves analyzing how language is used to construct meaning and power relations in a particular historical period. Discourse analysis can help to identify how social and political ideologies were constructed and maintained over time.

- Statistical analysis: This involves using statistical methods to analyze numerical data, such as census records or economic data, to identify patterns and trends. Statistical analysis can help to identify changes in population demographics, economic conditions, and other factors over time.

- Comparative analysis : This involves comparing data from two or more historical periods or events to identify similarities and differences. Comparative analysis can help to identify patterns and trends that may not be apparent from analyzing data from a single historical period.

- Qualitative analysis: This involves analyzing non-numerical data, such as oral history interviews or ethnographic field notes, to identify themes and patterns. Qualitative analysis can provide a rich understanding of the experiences and perspectives of individuals in the past.

Historical Research Methodology

Here are the general steps involved in historical research methodology:

- Define the research question: Start by identifying a research question that you want to answer through your historical research. This question should be focused, specific, and relevant to your research goals.

- Review the literature: Conduct a review of the existing literature on the topic of your research question. This can involve reading books, articles, and academic papers to gain a thorough understanding of the existing research.

- Develop a research design : Develop a research design that outlines the methods you will use to collect and analyze data. This design should be based on the research question and should be feasible given the resources and time available.

- Collect data: Use the methods outlined in your research design to collect data on past events, people, and cultures. This can involve archival research, oral history interviews, artifact analysis, and other data collection methods.

- Analyze data : Analyze the data you have collected using the methods outlined in your research design. This can involve content analysis, textual analysis, statistical analysis, and other data analysis methods.

- Interpret findings : Use the results of your data analysis to draw meaningful insights and conclusions related to your research question. These insights should be grounded in the data and should be relevant to the research goals.

- Communicate results: Communicate your findings through a research report, academic paper, or other means. This should be done in a clear, concise, and well-organized manner, with appropriate citations and references to the literature.

Applications of Historical Research

Historical research has a wide range of applications in various fields, including:

- Education : Historical research can be used to develop curriculum materials that reflect a more accurate and inclusive representation of history. It can also be used to provide students with a deeper understanding of past events and cultures.

- Museums : Historical research is used to develop exhibits, programs, and other materials for museums. It can provide a more accurate and engaging presentation of historical events and artifacts.

- Public policy : Historical research is used to inform public policy decisions by providing insights into the historical context of current issues. It can also be used to evaluate the effectiveness of past policies and programs.

- Business : Historical research can be used by businesses to understand the evolution of their industry and to identify trends that may affect their future success. It can also be used to develop marketing strategies that resonate with customers’ historical interests and values.

- Law : Historical research is used in legal proceedings to provide evidence and context for cases involving historical events or practices. It can also be used to inform the development of new laws and policies.

- Genealogy : Historical research can be used by individuals to trace their family history and to understand their ancestral roots.

- Cultural preservation : Historical research is used to preserve cultural heritage by documenting and interpreting past events, practices, and traditions. It can also be used to identify and preserve historical landmarks and artifacts.

Examples of Historical Research

Examples of Historical Research are as follows:

- Examining the history of race relations in the United States: Historical research could be used to explore the historical roots of racial inequality and injustice in the United States. This could help inform current efforts to address systemic racism and promote social justice.

- Tracing the evolution of political ideologies: Historical research could be used to study the development of political ideologies over time. This could help to contextualize current political debates and provide insights into the origins and evolution of political beliefs and values.

- Analyzing the impact of technology on society : Historical research could be used to explore the impact of technology on society over time. This could include examining the impact of previous technological revolutions (such as the industrial revolution) on society, as well as studying the current impact of emerging technologies on society and the environment.

- Documenting the history of marginalized communities : Historical research could be used to document the history of marginalized communities (such as LGBTQ+ communities or indigenous communities). This could help to preserve cultural heritage, promote social justice, and promote a more inclusive understanding of history.

Purpose of Historical Research

The purpose of historical research is to study the past in order to gain a better understanding of the present and to inform future decision-making. Some specific purposes of historical research include:

- To understand the origins of current events, practices, and institutions : Historical research can be used to explore the historical roots of current events, practices, and institutions. By understanding how things developed over time, we can gain a better understanding of the present.

- To develop a more accurate and inclusive understanding of history : Historical research can be used to correct inaccuracies and biases in historical narratives. By exploring different perspectives and sources of information, we can develop a more complete and nuanced understanding of history.

- To inform decision-making: Historical research can be used to inform decision-making in various fields, including education, public policy, business, and law. By understanding the historical context of current issues, we can make more informed decisions about how to address them.

- To preserve cultural heritage : Historical research can be used to document and preserve cultural heritage, including traditions, practices, and artifacts. By understanding the historical significance of these cultural elements, we can work to preserve them for future generations.

- To stimulate curiosity and critical thinking: Historical research can be used to stimulate curiosity and critical thinking about the past. By exploring different historical perspectives and interpretations, we can develop a more critical and reflective approach to understanding history and its relevance to the present.

When to use Historical Research

Historical research can be useful in a variety of contexts. Here are some examples of when historical research might be particularly appropriate:

- When examining the historical roots of current events: Historical research can be used to explore the historical roots of current events, practices, and institutions. By understanding how things developed over time, we can gain a better understanding of the present.

- When examining the historical context of a particular topic : Historical research can be used to explore the historical context of a particular topic, such as a social issue, political debate, or scientific development. By understanding the historical context, we can gain a more nuanced understanding of the topic and its significance.

- When exploring the evolution of a particular field or discipline : Historical research can be used to explore the evolution of a particular field or discipline, such as medicine, law, or art. By understanding the historical development of the field, we can gain a better understanding of its current state and future directions.

- When examining the impact of past events on current society : Historical research can be used to examine the impact of past events (such as wars, revolutions, or social movements) on current society. By understanding the historical context and impact of these events, we can gain insights into current social and political issues.

- When studying the cultural heritage of a particular community or group : Historical research can be used to document and preserve the cultural heritage of a particular community or group. By understanding the historical significance of cultural practices, traditions, and artifacts, we can work to preserve them for future generations.

Characteristics of Historical Research

The following are some characteristics of historical research:

- Focus on the past : Historical research focuses on events, people, and phenomena of the past. It seeks to understand how things developed over time and how they relate to current events.

- Reliance on primary sources: Historical research relies on primary sources such as letters, diaries, newspapers, government documents, and other artifacts from the period being studied. These sources provide firsthand accounts of events and can help researchers gain a more accurate understanding of the past.

- Interpretation of data : Historical research involves interpretation of data from primary sources. Researchers analyze and interpret data to draw conclusions about the past.

- Use of multiple sources: Historical research often involves using multiple sources of data to gain a more complete understanding of the past. By examining a range of sources, researchers can cross-reference information and validate their findings.

- Importance of context: Historical research emphasizes the importance of context. Researchers analyze the historical context in which events occurred and consider how that context influenced people’s actions and decisions.

- Subjectivity : Historical research is inherently subjective, as researchers interpret data and draw conclusions based on their own perspectives and biases. Researchers must be aware of their own biases and strive for objectivity in their analysis.

- Importance of historical significance: Historical research emphasizes the importance of historical significance. Researchers consider the historical significance of events, people, and phenomena and their impact on the present and future.

- Use of qualitative methods : Historical research often uses qualitative methods such as content analysis, discourse analysis, and narrative analysis to analyze data and draw conclusions about the past.

Advantages of Historical Research

There are several advantages to historical research:

- Provides a deeper understanding of the past : Historical research can provide a more comprehensive understanding of past events and how they have shaped current social, political, and economic conditions. This can help individuals and organizations make informed decisions about the future.

- Helps preserve cultural heritage: Historical research can be used to document and preserve cultural heritage. By studying the history of a particular culture, researchers can gain insights into the cultural practices and beliefs that have shaped that culture over time.

- Provides insights into long-term trends : Historical research can provide insights into long-term trends and patterns. By studying historical data over time, researchers can identify patterns and trends that may be difficult to discern from short-term data.

- Facilitates the development of hypotheses: Historical research can facilitate the development of hypotheses about how past events have influenced current conditions. These hypotheses can be tested using other research methods, such as experiments or surveys.

- Helps identify root causes of social problems : Historical research can help identify the root causes of social problems. By studying the historical context in which these problems developed, researchers can gain a better understanding of how they emerged and what factors may have contributed to their development.

- Provides a source of inspiration: Historical research can provide a source of inspiration for individuals and organizations seeking to address current social, political, and economic challenges. By studying the accomplishments and struggles of past generations, researchers can gain insights into how to address current challenges.

Limitations of Historical Research

Some Limitations of Historical Research are as follows:

- Reliance on incomplete or biased data: Historical research is often limited by the availability and quality of data. Many primary sources have been lost, destroyed, or are inaccessible, making it difficult to get a complete picture of historical events. Additionally, some primary sources may be biased or represent only one perspective on an event.

- Difficulty in generalizing findings: Historical research is often specific to a particular time and place and may not be easily generalized to other contexts. This makes it difficult to draw broad conclusions about human behavior or social phenomena.

- Lack of control over variables : Historical research often lacks control over variables. Researchers cannot manipulate or control historical events, making it difficult to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

- Subjectivity of interpretation : Historical research is often subjective because researchers must interpret data and draw conclusions based on their own biases and perspectives. Different researchers may interpret the same data differently, leading to different conclusions.

- Limited ability to test hypotheses: Historical research is often limited in its ability to test hypotheses. Because the events being studied have already occurred, researchers cannot manipulate variables or conduct experiments to test their hypotheses.

- Lack of objectivity: Historical research is often subjective, and researchers must be aware of their own biases and strive for objectivity in their analysis. However, it can be difficult to maintain objectivity when studying events that are emotionally charged or controversial.

- Limited generalizability: Historical research is often limited in its generalizability, as the events and conditions being studied may be specific to a particular time and place. This makes it difficult to draw broad conclusions that apply to other contexts or time periods.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Documentary Research – Types, Methods and...

Scientific Research – Types, Purpose and Guide

Original Research – Definition, Examples, Guide

Humanities Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Artistic Research – Methods, Types and Examples

- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Faculty of Arts & Sciences Libraries

Library Research Guide for History

Getting what you need, general information.

- Newsletter February 2024

- Exploring Your Topic

- HOLLIS (and other) Catalogs

- Document Collections/Microfilm

- Outline of Primary Sources for History

- Finding Online Sources: Detailed Instructions

- Religious Periodicals

- Personal Writings/Speeches

- Oral History and Interviews

- News Sources

- Archives and Manuscripts

- Government Archives (U.S.)

- U.S. Government Documents

- Foreign Government & International Organization Documents

- French Legislative Debates/Documents

- State and City Documents

- Historical Statistics/Data

- GIS Mapping

- Public Opinion

- City Directories

- Policy Literature, Working Papers, Think Tank Reports (Grey Literature)

- Technical Reports (Grey Literature)

- Country Information

- Corporate Annual Reports

- US Elections

- Travel Writing/Guidebooks

- Missionary Records

- Reference Sources

- Harvard Museums

- Boston-Area Repositories

- Citing Sources & Organizing Research

- Newsletter January 2011

- Newsletter June 2012

- Newsletter August 2012

- Newsletter December 2012

- Newsletter June 2013

- Newsletter August 2013

- Newsletter January 2014

- Newsletter June 2014

- Newsletter August 2014

- Newsletter January 2015

- Newsletter June 2015

- Newsletter August 2015

- Newsletter January 2016

- Newsletter June 2016

- Newsletter August 2016

- Newsletter January 2017

- Newsletter June 2017

- Newsletter August 2017

- Newsletter January 2018

- Newsletter June 2018

- Newsletter August 2018

- Newsletter August 2019

- Newsletter December 2019

- Newsletter March 2021

- Newsletter October 2021

- Newsletter June 2019

- Newsletter May 2022

- Newsletter February2023

- Newsletter October 2023

- Exploring Special Collections at Harvard

Fred Burchsted & Anna Assogba

Research Librarians

We are always happy to give you a tour of Widener and an orientation to our catalog, HOLLIS, and our other resources. Our emails are below.

This guide is intended as a point of departure for research in history. We also have a more selective guide with major resources only: Introductory Library Research Guide for History .

- Finding Primary Sources Online offers methods for finding digital libraries and digital collections on the open Web and for finding Digital Libraries/Collections by Region or Language .

- Online Primary Source Collections for History lists digital collections at Harvard and beyond by topic

Please feel free to email us with questions. We can make an appointment for you to come in, and we can talk at length about your project.

- Anna Assogba ([email protected]) Research Librarian and Liaison to the Department of History, Lamont Library (With particular knowledge of Zotero and other citation management systems).

- Fred Burchsted ([email protected]) Research Librarian and Liaison to the Department of History, Widener Library.

How can you get your hands/eyes on material?

HOLLIS is the center of the Library ecosystem. This is often the best first step to see if we have something. In HOLLIS, click on "Online Access" or open the record and scroll down to the "Access Options" section. Check the HOLLIS section of this guide for more guidance.

Browser Plugins for Library Access

Harvard Library Bookmark and Lean Library plugins can help you find out if we have access to books and articles online.

Off-Site Storage

Books and other materials stored in facilities not on Harvard's main campus. Request this material through HOLLIS:

- Select "Request Pick Up" in the Access section of the HOLLIS Record, then enter your Harvard Key.

- A drop down menu will allow you to choose delivery location. Sometimes there is a single delivery option. Submit your request.

- You will receive an email usually next business day (not weekends or holidays) morning. Item is usually ready for pick-up in mid-afternoon.

Sometimes Offsite storage material is in-library use only. For Widener, this is the Widener secure reading room on the 1st floor (formerly the Periodicals Room). Most Offsite storage material is available for scanning via Scan & Deliver (see below).

Scan & Deliver/Interlibrary Loan

Use Scan & Deliver/Interlibrary Loan to request PDFs of articles and book chapters from HOLLIS when you cannot get online access. Limit: 2 chapters from a book or 2 articles from a journal.

Interlibrary Loan

Request materials from other libraries via InterLibrary Loan :

- Some non-Harvard special collections may be willing and able to scan material (usually for a fee). Our Interlibrary Loan department will place the request and help with the cost (there is a cap).

- Contact the other repository to see if they're able to scan what you need. Get a price estimate for the material and the exact details (such as: Box 77 folder 4. This information is often available in Finding Aids).

- Fill in what you can (put in N/A if the field is inapplicable) with the price and other information in the Comments box.

- This will get the process going and ILL will get back to you if they need more information or to discuss the price.

BorrowDirect

Borrow Direct allows Harvard students, faculty, and staff to request items from other libraries for delivery to Harvard within 4 business days. If the item you need is not available, try searching our partner institutions' collections in BorrowDirect.

Purchase Request

If there are materials you'd like to see added to the library's collections, submit a purchase request and we will look into acquiring it. We can buy both physical and electronic copies of materials; specify if have a preference.

Special Collections

Special Collections are rare, unique, primary source materials in the library's collections. To access, look for "Request to Scan or Visit" in HOLLIS (to place a scanning request) or contact the repository directly. Most of our larger archival collections are able to provide scans.

Carrels at Widener Library

Graduate students and visiting scholars are eligible to have a carrel in the Widener Library stacks. Start the process with the carrel request form . (If you do this right at the start of the semester, it may take a few weeks before you receive confirmation.) Materials from the Widener stacks, including non-circulating materials like bound periodicals, can be checked out to your carrel.

Ivy Plus Privileges

Our partnership with BorrowDirect allows physical access to libraries of fellow Ivy Plus institutions: Brown University, Columbia University, Cornell University, Dartmouth College, Duke University, Johns Hopkins University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Princeton University, Stanford University, University of Chicago, University of Pennsylvania, and Yale University.

Help with Digital Projects

The Digital Scholarship Group offers workshops and support to faculty, students, and staff interested in digital research methods. See also GIS Mapping Resources and Visualization Support .

- Other Subject Guides

- Current Awareness Resources

More guides are available via the Harvard Library Research Guides site

Finding Book Reviews

Finding Dissertations and Theses

Finding Harvard Library's Unique or Distinctive Primary Sources: Original and Digital

Guide to Research in History of Art & Architecture

Library Research Guide for Book History

Library Research Guide for British Colonial and Foreign Relations Sources

Research Guide for Primary Sources on Civil Rights

Inter Libros: Research Guide for Classics, Byzantine, & Medieval Studies

Literary Research in Harvard Libraries

Library Research Guide for American Material Culture (This is in an early stage of development)

Middle East and Islamic Studies Library Resources

Music 219r: American Music , Library Guide

Library Research Guide for HIST 1006: Native American and Indigenous Studies

Library Research Guide for the History of Science

Library Research Guide for History 97g: "What is Legal History ?"

Library Research Guide for U.S. Foreign Relations

Library Research Guide for Global History

Library Research Guide for HIST 2256: Digital Archives: Europe and European Empires

Library Research Guide for Educating for American Democracy

Library Research Guide for American Studies

Library Research Guide for Latin American Studies

Germanic Languages and Literatures

Slavic and Eurasian Studies at Harvard (See Research Contacts at bottom of left hand column)

Library Research Guide for South Asian Studies

Library Research Guide for HIST 1037: Modern Southeast Asia

Research Guides at Other Institutions

Go to Google Advanced Search

- all of these words: Sociology library

- any of these words: guides research resources

- site or domain: edu (or ac.uk for Britain, etc.)

To find new Harvard E-Resources.Go to Cross-Search in Harvard Libraries E-Resources and choose the Quick Set: New E-Resources. This operates oddly, you sometimes have to select one of the E-Resources displayed, then close the resulting page to see the whole list of new E-Resources. This list displays some but not all new E-Resources.

The following history library blogs list new history resources:

- Reviews in History

- University of Washington

- Next: Newsletter February 2024 >>

- Last Updated: May 13, 2024 1:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/history

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

Historical Associations

Professional associations and academic communities are often a good place to start for scholarly information and materials on methods and research.

- American Historical Association The professional and academic organization of academic historians, this organization has a wealth of information about careers in history as well as a directory of historians and historical programs

- H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online H-Net "creates and coordinates Internet networks with the common objective of advancing teaching and research in the arts, humanities, and social sciences." Contains public discussion lists related to numerous disciplines.

- National Council on Public History The professional association for public historians, the NCPH serves practitioners by "building community among historians, expanding professional skills and tools, fostering critical reflection on historical practice, and publicly advocating for history and historians."

- Organization of American Historians Less focused on academic history, the OAH nonetheless provides quite a bit of information about the profession, jobs, and current topics in history.

Historical Research and Methods

Guides and major works.

The following is a list of works on Historical methods, philosophy, and subfields of history.

Writing Guide

A series of guides on reading, researching and writing history by Patrick Rael, professor of History at Bowdoin College can be found on this link

Source: Patrick Rael, Reading, Writing, and Researching for History: A Guide for College Students (Brunswick, ME: Bowdoin College, 2004).

Research Methods

The Shapiro Library subscribes to the SAGE Research Methods database, a resource designed for those who are doing research or who are learning how to do research. Methods and practices covered include writing research questions and literature reviews, choosing research methods, conducting oral histories, and more.

- << Previous: Primary Sources

- Next: Citing Your Sources >>

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Write a History Research Paper

In my last post, I shared some tips on how to conduct research in history and emphasized that researchers should keep in mind a source’s category (transcript, court document, speech, etc.). This post is something of a sequel to that, as I will share some thoughts on what often follows primary-source research: a history research paper.

1. Background Reading The first step to a history research paper is of course, background reading and research. In the context of a class assignment, “background reading” might simply be course readings or lectures, but for independent work, this step will likely involve some quality time on your own in the library. During the background reading phase of your project, keep an eye out for intriguing angles to approach your topic from and any trends that you see across sources (both primary and secondary).

2. T hemes and Context Recounting the simple facts about your topic alone will not make for a successful research paper. One must grasp both the details of events as well as the larger, thematic context of the time period in which they occurred. What’s the scholarly consensus about these themes? Does that consensus seem right to you, after having done primary and secondary research of your own?

3. Develop an Argument Grappling with answers to the above questions will get you thinking about your emerging argument. For shorter papers, you might identify a gap in the scholarship or come up with an argumentative response to a class prompt rather quickly. Remember: as an undergraduate, you don’t have to come up with (to borrow Philosophy Professor Gideon Rosen’s phrase) ‘a blindingly original theory of everything.’ In other words, finding a nuanced thesis does not mean you have to disprove some famous scholar’s work in its entirety. But, if you’re having trouble defining your thesis, I encourage you not to worry; talk to your professor, preceptor, or, if appropriate, a friend. These people can listen to your ideas, and the simple act of talking about your paper can often go a long way in helping you realize what you want to write about.

4. Outline Your Argument With a history paper specifically, one is often writing about a sequence of events and trying to tell a story about what happened. Roughly speaking, your thesis is your interpretation of these events, or your take on some aspect of them (i.e. the role of women in New Deal programs). Before opening up Word, I suggest writing down the stages of your argument. Then, outline or organize your notes to know what evidence you’ll use in each of these various stages. If you think your evidence is solid, then you’re probably ready to start writing—and you now have a solid roadmap to work from! But, if this step is proving difficult, you might want to gather more evidence or go back to the thesis drawing board and look for a better angle. I often find myself somewhere between these two extremes (being 100% ready to write or staring at a sparse outline), but that’s also helpful, because it gives me a better idea of where my argument needs strengthening.

5. Prepare Yourself Once you have some sort of direction for the paper (i.e. a working thesis), you’re getting close to the fun part—the writing itself. Gather your laptop, your research materials/notes, and some snacks, and get ready to settle in to write your paper, following your argument outline. As mentioned in the photo caption, I suggest utilizing large library tables to spread out your notes. This way, you don’t have to constantly flip through binders, notebooks, and printed drafts.

In addition to this step by step approach, I’ll leave you with a few last general tips for approaching a history research paper. Overall, set reasonable goals for your project, and remember that a seemingly daunting task can be broken down into the above constituent phases. And, if nothing else, know that you’ll end up with a nice Word document full of aesthetically pleasing footnotes!

— Shanon FitzGerald, Social Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Policy

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Why Publish with Historical Research?

- About Historical Research

- About the Institute of Historical Research

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Sara Charles Claire Langhamer

About the journal

Published since 1923, Historical Research , flagship publication of the Institute of Historical Research , is a leading generalist history journal, covering the global history of the early middle ages to the twenty-first century...

Classic articles from the recent archives

The new virtual issue from Historical Research shines a light on some of the classic articles from the journal’s recent archive. It features some of the most read and most cited articles from the journal’s archives and covers a wide range of topics of perennial interest to both historians and to a wider readership.

Browse the virtual issue

2020 Historical Research lecture, video now available

The video of this year's lecture -- 'Writing histories of 2020' -- held on 29 July, is now available. With panellists Professors Jo Fox, Claire Langhamer, Kevin Siena and Richard Vinen who discuss historians' responses to COVID-19 and Black Lives Matter.

Watch the video of the 2020 lecture

Never miss an issue

Register for email alerts to receive a notification straight to your inbox each time a new issue publishes.

Join the mailing list

IHR guide to free research resources

From April 2020, the Institute of Historical Research has created a listing of free research materials for historians currently unable to access libraries and archives. The list is regularly extended as researchers offer new suggestions.

Access the resources

Latest articles

Latest posts on x, on history blog, the victoria county history at 125: now and the future , a fanfare for garden history, invitation: bibliography of british and irish history (bbih) editorial board membership, call for section editors: bibliography of british and irish history (bbih), laurence swarfeld of antwerp and london: cross channel connections in the 15th century customs accounts, the annual pollard prize, about the prize.

The Pollard Prize is awarded annually for the best paper presented at an Institute of Historical Research seminar by a postgraduate student or by a researcher within one year of completing the PhD. The prize is supported by Oxford University Press.

Find out more about the prize and eligibility requirements on the IHR website .

2021 prize winners

Congratulations to Merve Fejzula for winning the Annual Pollard Prize for 2021 with their paper 'Toward a History of Intellectual Labor: Gender, Negritude, and the Black Public Sphere.' Congratulations also to runner up Lucy Clarke for their paper '"I say I must for I am the King’s shrieve": magistrates invoking the monarch’s name in 1 Henry VI (1592) and The Downfall of Robert Earl of Huntingdon (1598)'.

Both papers will be published in Historical Research in due course.

Institute of Historical Research

The Institute of Historical Research is the UK's national centre for history, dedicated to supporting historians of all kinds.

Find out more about IHR

Reviews in History

Launched in 1996, Reviews in History now contains more than 2200 reviews, published monthly and are freely accessible as Open Access. Reviews are written by specialists in the field and all authors reviewed have an opportunity to respond.

Explore the latest reviews

On History blog

Explore news, articles, and research from On History , a digital magazine curated and published by the Institute of Historical Research.

View the latest posts

The IHR’s new mission and strategy, 2020-2025

The IHR is pleased to launch its new mission and strategy, setting out the values and vision for the IHR in the coming years.

Read the strategy

Related Titles

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-2281

- Print ISSN 0950-3471

- Copyright © 2024 Institute of Historical Research

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Evolution of Nursing Research

Jacqueline m. stolley.

Trinity College of Nursing, Moline, Illinois

THE RESEARCH CULTURE in nursing has evolved in the last 150 years, beginning with Nightingale’s work in the mid-1850s and culminating in the creation of the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) at the National Institues of Health (NIH). This article highlights nursing’s efforts to facilitate the growth of the research culture by developing theory, establishing the importance of a research-based practice, advancing education, and providing avenues for dissemination of research. Similarities with the chiropractic profession are discussed, along with a commentary by Cheryl Hawk, D.C, Ph.D.

EVOLUTION OF NURSING RESEARCH

The development of a research culture in nursing in many ways parallels that of chiropractic, and by reviewing key aspects of the evolution of the science of nursing, there are lessons to be learned, and mistakes to be avoided. Nursing research has changed dramatically in the past 150 years, beginning with Florence Nightingale in the 19th century. Clearly, nursing research has not always had the influence and significance it holds today. In fact, for a number of years after Nightingale’s work, little is found in the literature concerning nursing research. This is perhaps due to the past perception of nursing as an apprenticeship in a task-oriented caring profession ( 1 ). Although research was conducted with respect to nursing education and administration in the first half of the 20th century, it was not until the 1950s that nursing research began the advancement that has been seen in the past three decades. This is due to many factors: an increase in the number of nurses with advanced academic preparation, the establishment of vehicles for dissemination of nursing research, federal funding and support for nursing research, and the upgrading of research skills in faculty and students. This article provides a brief review of the development of research in nursing, and along with it, the theory that has guided that process.

NURSING THEORY DEVELOPMENT