Social Problem Solving

- Reference work entry

- pp 1399–1403

- Cite this reference work entry

- Molly Adrian 3 ,

- Aaron Lyon 4 ,

- Rosalind Oti 5 &

- Jennifer Tininenko 6

807 Accesses

4 Altmetric

Interpersonal cognitive problem solving ; Interpersonal problem solving ; Social decision making ; Social information processing

Social problem solving is the process by which individuals identify and enact solutions to social life situations in an effort to alter the problematic nature of the situation, their relation to the situation, or both [ 7 ].

Description

In D’Zurilla and Goldfried’s [ 6 ] seminal article, the authors conceptualized social problem solving as an individuals’ processing and action upon entering interpersonal situations in which no immediately effective response is available. One primary component of social problem solving is the cognitive-behavioral process of generating potential solutions to the social dilemma. The steps in this process were posited to be similar across individuals despite the wide variability of observed behaviors. The revised model [ 7 ] is comprised of two interrelated domains: problem orientation and problem solving style....

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: Vol 1: Attachment (2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books.

Google Scholar

Chen, X., & French, D. C. (2008). Children’s social competence in cultural context. Annual Review of Psychology, 59 , 591–616.

PubMed Google Scholar

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115 , 74–101.

Dodge, K. A., & Coie, J. D. (1987). Social-information-processing factors in reactive and proactive aggression in children’s peer groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53 , 1146–1158.

Downey, G., & Coyne, J. C. (1990). Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 108 , 50–76.

D’Zurilla, T. J., & Goldfried, M. R. (1971). Problem solving and behavior modification. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 78 , 107–126.

D’Zurilla, T. J., & Nezu, A. M. (1999). Problem solving therapy: A social competence approach to clinical intervention (2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

Lochman, J. E., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). Social-cognitive processes of severely violent, moderately aggressive, and nonaggressive boys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62 , 366–374.

Pettit, G. S., Dodge, K. A., & Brown, M. M. (1988). Early family experience, social problem solving patterns, and children’s social competence. Child Development, 59 , 107–120.

Quiggle, N. L., Garber, J., Panak, W. F., & Dodge, K. A. (1992). Social information processing in aggressive and depressed children. Child Development, 63 , 1305–1320.

Rubin, K. H., & Krasnor, L. R. (1986). Social-cognitive and social behavioral perspectives on problem solving. In M. Perlmutter (Ed.), Cognitive perspectives on children’s social and behavioral development. The Minnesota symposia on child psychology (Vol. 18, pp. 1–68). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rubin, K. H., & Rose-Krasnor, L. (1992). Interpersonal problem-solving and social competence in children. In V. B. van Hasselt & M. Hersen (Eds.), Handbook of social development: A lifespace perspective . New York: Plenum.

Shure, M. B., & Spivack, G. (1980). Interpersonal problem solving as a mediator of behavioral adjustment in preschool and kindergarten children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 1 , 29–43.

Spivack, G., & Shure, M. B. (1974). Social adjustment of young children . San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Box 354920, Seattle, WA, 98195, USA

Molly Adrian

Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Health, Seattle Children's Hospital, 4800 Gand Point way NE, Seattle, WA, 98125, USA

Rosalind Oti

Evidence Based Treatment Center of Seattle, 1200 5th Avenue, Suite 800, Seattle, WA, 98101, USA

Jennifer Tininenko

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Neurology, Learning and Behavior Center, 230 South 500 East, Suite 100, Salt Lake City, Utah, 84102, USA

Sam Goldstein Ph.D.

Department of Psychology MS 2C6, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA, 22030, USA

Jack A. Naglieri Ph.D. ( Professor of Psychology ) ( Professor of Psychology )

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2011 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Adrian, M., Lyon, A., Oti, R., Tininenko, J. (2011). Social Problem Solving. In: Goldstein, S., Naglieri, J.A. (eds) Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-79061-9_2703

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-79061-9_2703

Publisher Name : Springer, Boston, MA

Print ISBN : 978-0-387-77579-1

Online ISBN : 978-0-387-79061-9

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

1.2 Defining a Social Problem

Figure 1.2 Sociologist Anna Leon-Guerrero. We use her definition of a social problem.

When you think about the current issues facing our society and our planet, you might name war, addiction, climate change, houselessness, or the global pandemic as social problems. You would be right, sort of. Sociologists need to be more specific than that. Because they are trying to explain what social problems are or how to fix them, they need a much more precise definition. Sociology professor and author Anna Leon-Guerrero (figure 1.2) defines a social problem as “a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world.”(2018:4).

More concretely, it is not just that one person gets sick from COVID-19. The social problem is that our healthcare systems are overwhelmed with sick patients. People are experiencing different rates of exposure to COVID-19. Their health outcomes differ because of their race, class, and gender. Because social problems affect people across the social and physical worlds, the solutions to social problems must be collectively created. It is not enough for one person to get well, although that may really matter to you. Instead, we must act collectively, as groups, governments, or systems to identify and implement solutions. Our health is personal, but getting well depends on all of us.

To talk effectively about social problems, we must understand their characteristics. In this text, we will explore five important dimensions of a social problem :

- A social problem goes beyond the experience of an individual.

- A social problem results from a conflict in values.

- A social problem arises when groups of people experience inequality.

- A social problem is socially constructed but real in its consequences.

- A social problem must be addressed interdependently, using both individual agency and collective action.

In the following section, we examine each of these five characteristics. Where these characteristics exist, social problems follow. Each component provides an additional layer of explanation about why any human problem is a social problem.

1.2.1 Social Problems: Beyond Individual Experience

Individuals have problems. Social problems, though, go beyond the experience of one individual. They are experienced by groups, nations, or people around the world. An individual experiences job loss, but the wider social problem may be rising unemployment rates. An individual may experience a divorce, but the wider social problem may be changing expectations around marriage and long-term partnerships. Solving a social problem is a collective task, outside of the capability of one individual or group.

Figure 1.3 Sociologist C. Wright Mills, pictured on the left wrote about the Sociological Imagination

In his book The Sociological Imagination , American sociologist C. Wright Mills helps us understand the difference between individual problems and social problems, and connects the two concepts (figure 1.3). Mills (1959) uses the term personal troubles to describe troubles that happen both within and to an individual. He contrasts these personal troubles with social problems, which he calls public issues . Public issues transcend the experience of one individual, impacting groups of people over time.

To illustrate, a recent college graduate may be several hundred thousand dollars in debt because of student loans. They may have trouble paying for living expenses because of this debt. This would be a personal trouble. If we look for larger social patterns, however, we see that as of 2021 about 1 in 8 Americans have student loan debt, owing about 1.6 trillion dollars (Federal Reserve Bank of New York 2021). The volume of this debt, the related laws, policies, and practices, and the harm that is being caused stretch far beyond the experience of a few individuals, resulting in student loan debt becoming a public issue.

In addition to differentiating personal troubles and public issues, Mills also connects them using the sociological imagination , a quality of mind that connects individual experience and wider social forces. He writes, “The sociological imagination enables us to grasp history and biography and the relations between the two within society. This is its task and its promise” (Mills 1959:6).

In other words, when we use our own sociological imaginations, we connect our own lives with the experiences of other people. We consider how our own past actions and the historical actions of others may have contributed to our current reality. We use our sociological imaginations to consider what the outcomes of our actions or of social policies might be. When you use your sociological imagination, complicated social problems begin to make sense. When Mills linked personal troubles and public issues, he emphasized that individuals are acted upon by wider social forces.

Figure 1.4 A society consists of more than individual people, just like a forest consists of more than just individual trees: The forest around Cougar Hot Springs, Oregon—More than just individual trees. Tokyo, Japan—More than individual people.

Building on Mills’s concepts, current sociologists highlight the complex relationships of the social world. In the 2019 Society for the Study of Social Problems Presidential Address, Society president Nancy Mezey explores the topic of climate change as a social problem. Understanding and solving climate change requires a deep understanding of the relationship of people and systems. She emphasizes that “society is not just a collection of unrelated individuals, but rather a collection of people who live in relationship with each other” (Mezey 2020: 606). To make this point, she uses the work of sociologist Allan Johnson. In his book The Forest and the Trees, Johnson compares the physical world to our social world:

In one sense, a forest is simply a collection of individual trees, but it is more than that. It is also a collection of trees that exist in particular relation to one another, and you cannot tell what that relation is by looking at the individual trees. Take a thousand trees and scatter them across the Great Plains of North America and all you have is a thousand trees. But take those same trees and put them close together, and now you have a forest. The same individual trees in one case constitute a forest and in another are just a lot of trees. The “empty space” that separates individual trees from one another is not a characteristic of any one tree or the characteristics of all the individual trees somehow added together. It is something more than that, and it is crucial to understand the relationships among trees that make a forest what it is. Paying attention to that “something more” — whether it is a family or a society or the entire world – and how people are related to it lies at the heart of what it means to practice sociology . (Johnson 2014: 11-12, emphasis added)

Using this comparison, Mezey reminds us human society is made up of interdependent individuals, groups, institutions, and systems, similar to the living ecosystem of the forest. This similarity is illustrated in figure 1.4. The reach of a social problem can also be planet-wide. As the response to COVID-19 demonstrates, migrations between countries, vaccination policies and implementations for any nation, and the responses of health systems in local areas can all impact whether any individual is likely to get COVID-19 or to recover from it. A social problem, then, is one that involves a wider scope of groups, institutions, nations, or global populations.

1.2.2 Social Problems: A Conflict in Values

Social problems can also be defined as issues in which social values conflict. A value is an ideal or principle that determines what is correct, desirable, or morally proper. A society may share common values. For example, a society may value universal education, the ideal that all children should learn to read and write or, at minimum, be in school until they are 18. A different society may value practical experience, focusing on teaching children skills related to farming, hunting, or raising children. When core values are shared, there is no basis for conflict.

Social problems may begin to arise if people cannot agree on values. For example, some groups may value business growth and expansion. They oppose restrictions on pollution or emissions because following these regulations would cost money. In contrast, other groups might value sustaining the environment. They support regulations that limit industrial pollution, even when they cost more money. This conflict in values provides a rich soil from which a social problem may grow.

1.2.3 Social Problems: Inequality

A social problem can arise if there is a conflict between a widely shared value and a society’s success in meeting expectations around that value. For example, to sustain life, people need sufficient water, food, and shelter. To work well, a society values human life and creates infrastructure so that all members have water, food, and shelter. However, even at this most basic level, people experience significant inequality in their access to these resources.

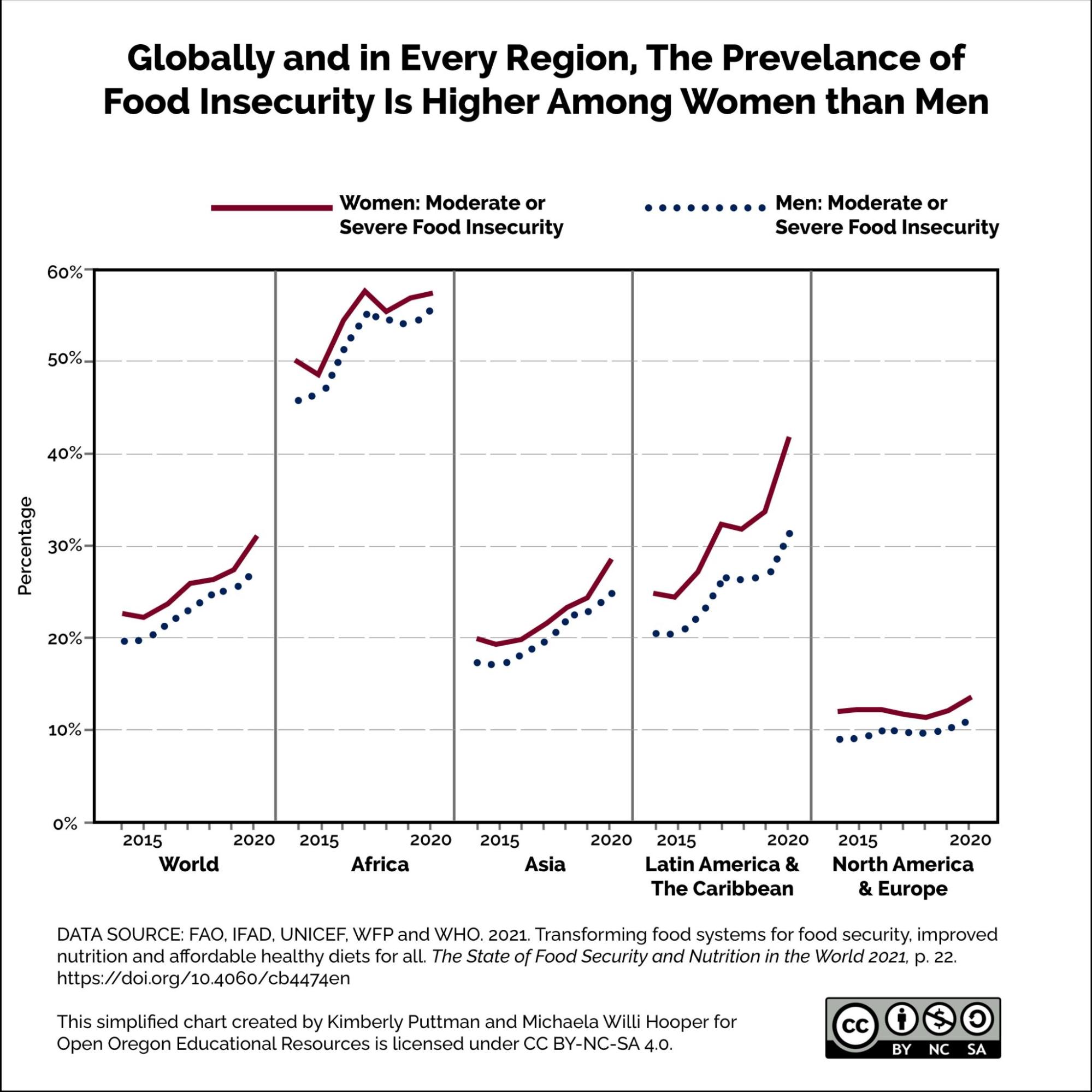

Figure 1.5 In this chart, we see that women experience more food insecurity than men, in every region of the world. In Africa, more than half of all people experience hunger. This rate of food insecurity has also increased around the world between 2015 and 2020. How do you think COVID-19 might have impacted world hunger? Figure 1.5 Image Description

For example, the United Nations reports that one in three people worldwide do not have access to adequate food. That number is rising (United Nations 2020). As we can see in the chart in figure 1.5, women are more likely than men to experience hunger in all regions of the world. The related report also notes that 22 percent of all children worldwide are stunted because they do not have enough to eat (FAO 2021).

In another example at the local level, the Oregon Food Bank explicitly defines hunger as a social problem. They write, “Hunger isn’t just an individual experience; it’s a symptom of barriers to employment, housing, health care and more—and a result of unfair systems that continue to keep these barriers in place” (Oregon Food Bank 2021). In exploring who is hungry in Oregon, they note that communities of color experience greater housing instability and therefore greater food insecurity than White families (Oregon Food Bank 2019). Unequal access and unequal outcomes are both common in our world and fundamental to social problems.

1.2.4 Social Problems: A Social Construction with Real Consequences

Figure 1.6: This 10 minute video on social construction explores what it means to jointly create our social reality. What else do you see that is socially constructed? Note to Reviewers: This 10 minute video on social construction is under construction. The final version will be included with the final version of the book. At the same time, we welcome comments on this draft.

Sociologists delight in statistics, those numbers that measure rates, patterns, and trends. You might think that a social problem exists when things get measurably worse—unemployment rises, food prices increase, deaths from AIDS skyrocket, or gender-related hate crimes explode. Changes in the numbers, or objective measures, provide only part of the story. Sometimes these changes go unnoticed in the wider society and don’t result in conflict or action. Other times a local community takes action, but another local community with similar statistics does not.

To explain this difference, we turn to the fundamental sociological concept of social construction , the idea that we create meaning through interaction with others. This concept asserts that while material objects and biological processes exist, it is the meaning that we give to them that creates our shared social reality. The video in figure 1.6 provides more examples of this concept.

The term social construction was used in 1966 by sociologists Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann. They wrote a book called The Social Construction of Reality . In it, they argued that society is created by humans and human interaction. These interactions are often habits. They use the term habitualization to describe how “any action that is repeated frequently becomes cast into a pattern, which can then be … performed again in the future in the same manner and with the same economical effort” (Berger and Luckmann 1966). Not only do we construct our own society but we also accept it as it is because others have created it before us. Society is, in fact, habit .

For example, a school building exists as a school and not as a generic building because you and others agree that it is a school. If your school is older than you are, it was created by the agreement of others before you. In a sense, it exists by consensus, both prior and current. This is an example of the process of institutionalization, the act of implanting a convention or social expectation into society. By employing the convention of naming a building as a school , the institution, while socially constructed, is made real and assigned specific expectations as to how it will be used.

Another way of looking at the social construction of reality is through an idea developed by American sociologist W. I. Thomas. The Thomas theorem states, “If [people] define situations as real, they are real in their consequences” (Thomas and Thomas 1928). In other words, people’s behavior can be determined by their subjective construction of reality rather than by objective reality. For example, a teenager who is repeatedly given a label—rebellious, emo, goth—often lives up to the term even though it initially wasn’t a part of their character.

Figure 1.7 What do you think the person in the photo, gesturing “Thumbs up” is trying to say? Depending on his country, he may be saying great , on e, or five . Even our gestures are socially constructed.

Sociologists who study how we interact also recognize that language and body language reflect our values. One has only to learn a foreign language to know that not every English word can be easily translated into another language. The same is true for gestures. What does the gesture in figure 1.7 mean? While Americans might recognize a thumbs-up as meaning great , in Germany it would mean one , and in Japan, it would mean five . Thus, our construction of reality is influenced by our symbolic interactions. When we apply this idea of the social construction of reality to social problems, then, we say that a social problem only exists when people say they have one.

Figure 1.8 In this picture of social protest, the protester is holding a sign “Whatever we wear, wherever we go, Yes means Yes and No means No” Over time our ideas about bodily autonomy, consent, and gender based violence are changing.

Let’s look at the crime of rape to understand this concept more clearly. Initially, rape was defined as a property crime. This view of women’s bodies is profoundly disturbing to us today but was common in seventeenth-century English law. Legally, women were considered the property of their fathers or their husbands. Therefore, rape was legally understood as decreasing the value of their property. Taking this model further, married women could not be raped by their husbands because consent was implied as part of the marriage contract.

When feminists in the 1970s challenged this legal definition, laws related to rape began to change. Rape, which included marital rape, became defined as a crime of violence and social control against an individual person (Rose 1977). In a more recent study, researchers examined how rape was defined in a college community between 1955 and 1990. Early descriptions of rape in school and community newspapers painted the picture that White women students were safe on campus. If they ventured beyond campus to predominantly Black neighborhoods, they risked being raped. Rape was considered a crime committed by a racialized other, a Black or Brown stranger rather than a member of a White student community. This perspective saw police as responsible for keeping women safe (Abu-Odeh, Khan, and Nathanson 2020).

With the work of feminist activists, the concept of rape and the response to rape changed. In the 1970s and 1980s, women’s centers and health professionals defined rape as an act of sexual violence that supported the structural power of men and an issue that threatened women’s health. The person who experienced rape began to be called a survivor rather than a victim . Men who raped or committed other kinds of sexual harassment could be identified as part of the campus community rather than being defined as a stranger or an outsider. The changes in the social construction of rape allowed for more effective community responses in preventing rape, prosecuting rape, and supporting the healing of rape survivors (Abu-Odeh, Khan, and Nathanson 2020).

Feminist activists continue this work. Black activist Tarana Burke founded the #MeToo movement in 2006 so that survivors of sexual violence could tell their stories. These stories highlight how common sexual violence is for women, men, and nonbinary people. It expands our conversation about rape to a wider discussion around the causes and consequences of sexual violence. If you would like to learn more about #MeToo from Burke herself, please watch this TED Talk, “ Me Too Is a Movement, Not a Moment .” Actor Alyssa Milano drew attention to this movement when she tweeted #MeToo in 2017. This movement has resulted in some changes in the law (Beitsch 2018) and in stronger prosecution of perpetrators of sexual violence, in some cases (Carlsen et al. 2018).

In this constructionist view, the definition of rape, the actors in the crime, and the responsibility for fixing the problem changed over time, with significant consequences to the people involved. Even concepts like consent, active agreement to sexual activity (see figure 1.8), are taught and learned. A Cup of Tea and Consent [YouTube] teaches the concept (some explicit language). We will see the usefulness of the social construction of a social problem as we explore each social problem raised in this book.

1.2.5 Social Problems: Interdependent Solutions of Individual Agency and Collective Action

All life is interelated. We are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied into a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. We are made to live together because of the interrelated structure of reality. This is the way our universe is structured, this is its interrelated quality. We aren’t going to have peace on earth until we recognize this basic fact of the interrelated structure of all reality.

—Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., activist, sociologist, and minister

Figure 1.9 Video: Martin Luther King Jr. A Christmas Speech: . Martin Luther King Jr. asserts that we are all interrelated, another word for interdependence in his Christmas Speech from 1967. While watching the whole speech is optional, you may want to view from minutes 7:10-7:12 to listen to the quote that begins this section.

Our diversity can be a source of innovative solutions to social problems. At the same time, the ways in which we are different divide us. We see bullying, hate crimes, war, gender based violence, and other patterns of treating each other differently based on our social location. At the same time, many of us go to school, raise families, live in neighborhoods, and die of old age. How is it that we are able to maintain our sense of community?

We begin to answer this question by reminding ourselves that the sociological imagination helps us see that there are wider social forces at play in our individual lives. Interdependence is the concept that people rely on each other to survive and thrive (Schwalbe 2018). Martin Luther King Jr. asserts that we are all interrelated, another word for interdependence, in his Christmas Speech from 1967 in figure 1.9. While watching the whole speech is optional, you may want to view from minutes 7:10-7:12 to listen to the quote that begins this section.

Interdependence is everywhere, but specific examples of social, economic, and physical interdependence may help us see it more clearly. With social interdependence, we rely on other people to cooperate to support our life. We give the same cooperation to others in turn. For example, when you consider your own life, you might notice how many people helped you become the person you are. When you were very young, you relied on a parent or caregivers to feed you, to clothe you, to keep you warm, and maybe to read you bedtime stories. As we widen this picture, we see that your caregivers relied on store owners and doctors, farmers and truckers, business people, and friends to support the work of caring for you. You may not have had a happy life, yet you lived long enough to read these words. This book was brought to you by authors, editors, artists, videographers, designers, musicians, librarians, and other students like you. These relationships demonstrate our social interdependence.

In addition to social interdependence, we experience economic interdependence. As we shop for groceries this week, we see empty shelves and rising food prices. COVID-19 is disrupting the global supply chain. Farmers growing oranges in Mexico can’t find laborers to pick the fruit. U.S. car manufacturers can’t get electronic chips manufactured in China. Even when people in Vietnam sew T-shirts or factory workers in Korea build TVs, the ships that carry these products from one country to another wait for dock workers to unload them. Our experiences with COVID-19 underline the truth of our economic interdependence.

We express this economic interdependence in relationships that describe the power of workers and the power of business owners. In 2017, Francis Fox Piven, the president of the American Sociological Association, defined interdependent power, arguing that while wealth and privilege create power, workers, tenants, and voters also have the power of participation. We see interdependent power today in the Great Resignation, with people deciding to resign from their jobs rather than return to work. We see it in restaurants reducing hours or closing down because they can’t find workers to wait tables and bus dishes. We see this in frontline workers becoming even more critical in providing basic services to a quarantined public. We live in a globally interdependent economy.

Finally, and maybe foundationally, we are physically interdependent. I remember being on a boat in a glacial lake in Alaska. The tour guide, a biologist, was asking the people on the tour about how many oceans there were in the world. All of us were desperately trying to remember fifth-grade geography, and counting the various oceans we remembered. Atlantic, Pacific, Indian . . . wait did the Arctic and Antarctic count as oceans? Maybe five? Maybe six? Maybe seven? At each answer, the biologist shook her head, “No.” We were stumped.

Figure 1.10 The Pacific Ocean at Lincoln City, Oregon, or maybe just one view of our planet’s one ocean.

She revealed that scientists who study the ocean now say that we have just one ocean (even though the ocean in figure 1.10 happens to be the Pacific Ocean, a few blocks from my house). It contains all the ocean water across our entire planet. Debris from a tsunami in Japan washed up on beaches from the tip of Alaska to the Baja peninsula and Hawaii. Rivers contribute up to 80 percent of the plastics pollution found in the ocean. We see that the COVID-19 virus travels with people around the world as infections move from place to place. As we cross the globe on our feet, bikes, camels, trains, cars, and airplanes, our diseases travel with us. We are physically interdependent.

Figure 1.11 When do we comply with the social norms of mask-wearing and elbow bumping?

Each of these ways of considering our interdependence matters when it comes to studying social problems and creating change. Because our actions affect one another, any social problem or solution ripples through our social world. For example, social scientists are examining mask-wearing during COVID-19.

In the video “ The Importance of Social Norms” (episode 8 on the website) , researcher Dr. Vera te Velde from the University of Queensland explores mask-wearing behavior around the world. She wanted to find out what would make mask wearing a social norm. Social norms are the rules or expectations that determine and regulate appropriate behavior within a culture, group, or society.

Dr. de Velde finds that when people trust each other and their government, they are much more likely to wear masks. Trust and shared agreement around social norms encourage consistent behavior. In other words, when we notice our interdependence and trust that others will follow social norms, we are more likely to follow them too. Sociologist Michael Schwalbe, in The Sociologically Examined Life, calls this mindfulness of interdependence. When we are aware, or mindful, of how our actions impact others, we are noticing our interdependence. We then often act for the good of all.

The interdependent nature of social problems also requires interdependent solutions. For this, we look at individual agency and collective action. The discipline of sociology always asks why? , but the sociologists who study social problems are particularly committed to taking action. They try to understand why a problem occurs to inform policy decisions, create community coalitions, or support healthy families. In the best cases, they seek to know their own biases and work to remediate them, so their research is used to create change. This challenge is explicitly stated by SSSP President Mezey:

The theme for the 2019 SSSP [Society for the Study of Social Problems] meeting is a call to sociologists and social scientists in general to draw deeply and widely on sociological roots to illuminate the social in all social problems with an eye to solving those problems. The theme calls us to speak broadly and widely, so that our discipline becomes a central voice in larger public discourses. I am calling on you, the reader, through this presidential address to focus on what is perhaps the largest social problem: climate change. Indeed, because we have been focusing on individual rather than social solutions regarding climate change—we are now facing grave and imminent danger. (Mezey 2020:606)

Society president Mezey tells us that studying problems is not enough. We must focus on the most critical social problem—climate change, to support all of us in taking action.

Addressing social problems requires individuals to act. Social agency is the capacity of an individual to actively and independently choose and to affect change. In other words, any individual can choose to vote, to protest, to parent well, or to be authentic about who they are in the world. Each act of positive social agency matters to that person and their community, even if the small waves of change are hard to see in the wider world.

Collective action refers to the actions taken by a collection or group of people, acting based on a collective decision. whose goal is to enhance their condition and achieve a common objective (Sekiwu and Okan 2022). These kinds of actions people take are creative responses to local issues. We typically think of collective action as a protest march or a social movement. Collective action can also be setting up the Salmon River Grange as the distribution center for food, clothes, and pizza for survivors of the Echo Mountain Fire. It could also be reinvigorating an Indigenous language or connecting businesses and nonprofits so you can provide digital literacy skills training. People, communities, and organizations imagine the future they want to see, and take organized action to make it happen.

To confront the social problems of our world, we need a both/and approach to their resolution. We act with individual agency to create a life that is healthy and nurturing and we act collectively to address interdependent issues.

1.2.6 Licenses and Attributions for Defining a Social Problem

1.2.6.1 open content, shared previously.

“Social Construction of Reality” is adapted from “ Social Construction of Reality ” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e , Openstax , which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 . Modifications: Summarized some content and applied it specifically to social problems. License Terms: Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-3e/pages/1-introduction

Figure 1.3. “ Sociologist C Wright Mills ” by Institute for Policy Studies is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .

Figure 1.4a. Photo by Deric is licensed under the Unsplash License .

Figure 1.4b. Photo by Chris Chan is licensed under the Unsplash License .

Figure 1.7. Photo by Aziz Acharki is licensed under the Unsplash License .

Figure 1.8. Photo by Raquel García is licensed under the Unsplash License .

Figure 1.11. Photo by Maxime is licensed under the Unsplash License .

1.2.6.2 All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 1.2. “ Anna Leon-Guerrero ” © Pacific Lutheran University is included under fair use.

Figure 1.9 “ Martin Luther King, Jr., Christmas Sermon ” by Mapping Minds is licensed under the Standard YouTube License .

1.2.6.3 Open Content, Original

“Defining a Social Problem” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

Figure 1.5. “Chart of World Hunger” by Kim Puttman and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

Figure 1.6. “ Social Construction Video (Draft) ” by Liz Pearce, Kim Puttman and Colin Stapp, Open Oregon Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

Figure 1.10. Photo by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

Image Description for Figure 1.5:

Globally, and in every region, the prevalence of food insecurity is higher among women than men

A line chart shows moderate or severe food insecurity for both women and men in different regions of the world from 2015 to 2020. The lines are often close, but women are always more food insecure than men. Throughout the world, food insecurity has risen for both women and men (from around 20% in 2015 to over 30% for women in 2020). The two lines diverge the most for Latin America and the Caribbean, where food insecurity went from approximately 25% in 2015 to over 40% in 2020. Food insecurity rates for both men and women are highest in Africa (almost 60% for both men and women in 2020) and lowest in North America (between 10 and 15% in 2020).

Data source: State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021, prepared by FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO.

This simplified version created by Michaela Willi Hooper and Kimberly Puttman and licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

[Return to Figure 1.5]

Social Problems Copyright © by Kim Puttman. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

- INTERPERSONAL SKILLS

- Problem Solving and Decision Making

- Social Problem Solving

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Interpersonal Skills:

- A - Z List of Interpersonal Skills

- Interpersonal Skills Self-Assessment

- Communication Skills

- Emotional Intelligence

- Conflict Resolution and Mediation Skills

- Customer Service Skills

- Team-Working, Groups and Meetings

- Decision-Making and Problem-Solving

- Effective Decision Making

- Decision-Making Framework

- Introduction to Problem Solving

- Identifying and Structuring Problems

- Investigating Ideas and Solutions

- Implementing a Solution and Feedback

- Creative Problem-Solving

Social Problem-Solving

- Negotiation and Persuasion Skills

- Personal and Romantic Relationship Skills

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

The SkillsYouNeed Guide to Interpersonal Skills

Social problem-solving might also be called ‘ problem-solving in real life ’. In other words, it is a rather academic way of describing the systems and processes that we use to solve the problems that we encounter in our everyday lives.

The word ‘ social ’ does not mean that it only applies to problems that we solve with other people, or, indeed, those that we feel are caused by others. The word is simply used to indicate the ‘ real life ’ nature of the problems, and the way that we approach them.

Social problem-solving is generally considered to apply to four different types of problems:

- Impersonal problems, for example, shortage of money;

- Personal problems, for example, emotional or health problems;

- Interpersonal problems, such as disagreements with other people; and

- Community and wider societal problems, such as litter or crime rate.

A Model of Social Problem-Solving

One of the main models used in academic studies of social problem-solving was put forward by a group led by Thomas D’Zurilla.

This model includes three basic concepts or elements:

Problem-solving

This is defined as the process used by an individual, pair or group to find an effective solution for a particular problem. It is a self-directed process, meaning simply that the individual or group does not have anyone telling them what to do. Parts of this process include generating lots of possible solutions and selecting the best from among them.

A problem is defined as any situation or task that needs some kind of a response if it is to be managed effectively, but to which no obvious response is available. The demands may be external, from the environment, or internal.

A solution is a response or coping mechanism which is specific to the problem or situation. It is the outcome of the problem-solving process.

Once a solution has been identified, it must then be implemented. D’Zurilla’s model distinguishes between problem-solving (the process that identifies a solution) and solution implementation (the process of putting that solution into practice), and notes that the skills required for the two are not necessarily the same. It also distinguishes between two parts of the problem-solving process: problem orientation and actual problem-solving.

Problem Orientation

Problem orientation is the way that people approach problems, and how they set them into the context of their existing knowledge and ways of looking at the world.

Each of us will see problems in a different way, depending on our experience and skills, and this orientation is key to working out which skills we will need to use to solve the problem.

An Example of Orientation

Most people, on seeing a spout of water coming from a loose joint between a tap and a pipe, will probably reach first for a cloth to put round the joint to catch the water, and then a phone, employing their research skills to find a plumber.

A plumber, however, or someone with some experience of plumbing, is more likely to reach for tools to mend the joint and fix the leak. It’s all a question of orientation.

Problem-Solving

Problem-solving includes four key skills:

- Defining the problem,

- Coming up with alternative solutions,

- Making a decision about which solution to use, and

- Implementing that solution.

Based on this split between orientation and problem-solving, D’Zurilla and colleagues defined two scales to measure both abilities.

They defined two orientation dimensions, positive and negative, and three problem-solving styles, rational, impulsive/careless and avoidance.

They noted that people who were good at orientation were not necessarily good at problem-solving and vice versa, although the two might also go together.

It will probably be obvious from these descriptions that the researchers viewed positive orientation and rational problem-solving as functional behaviours, and defined all the others as dysfunctional, leading to psychological distress.

The skills required for positive problem orientation are:

Being able to see problems as ‘challenges’, or opportunities to gain something, rather than insurmountable difficulties at which it is only possible to fail.

For more about this, see our page on The Importance of Mindset ;

Believing that problems are solvable. While this, too, may be considered an aspect of mindset, it is also important to use techniques of Positive Thinking ;

Believing that you personally are able to solve problems successfully, which is at least in part an aspect of self-confidence.

See our page on Building Confidence for more;

Understanding that solving problems successfully will take time and effort, which may require a certain amount of resilience ; and

Motivating yourself to solve problems immediately, rather than putting them off.

See our pages on Self-Motivation and Time Management for more.

Those who find it harder to develop positive problem orientation tend to view problems as insurmountable obstacles, or a threat to their well-being, doubt their own abilities to solve problems, and become frustrated or upset when they encounter problems.

The skills required for rational problem-solving include:

The ability to gather information and facts, through research. There is more about this on our page on defining and identifying problems ;

The ability to set suitable problem-solving goals. You may find our page on personal goal-setting helpful;

The application of rational thinking to generate possible solutions. You may find some of the ideas on our Creative Thinking page helpful, as well as those on investigating ideas and solutions ;

Good decision-making skills to decide which solution is best. See our page on Decision-Making for more; and

Implementation skills, which include the ability to plan, organise and do. You may find our pages on Action Planning , Project Management and Solution Implementation helpful.

There is more about the rational problem-solving process on our page on Problem-Solving .

Potential Difficulties

Those who struggle to manage rational problem-solving tend to either:

- Rush things without thinking them through properly (the impulsive/careless approach), or

- Avoid them through procrastination, ignoring the problem, or trying to persuade someone else to solve the problem (the avoidance mode).

This ‘ avoidance ’ is not the same as actively and appropriately delegating to someone with the necessary skills (see our page on Delegation Skills for more).

Instead, it is simple ‘buck-passing’, usually characterised by a lack of selection of anyone with the appropriate skills, and/or an attempt to avoid responsibility for the problem.

An Academic Term for a Human Process?

You may be thinking that social problem-solving, and the model described here, sounds like an academic attempt to define very normal human processes. This is probably not an unreasonable summary.

However, breaking a complex process down in this way not only helps academics to study it, but also helps us to develop our skills in a more targeted way. By considering each element of the process separately, we can focus on those that we find most difficult: maximum ‘bang for your buck’, as it were.

Continue to: Decision Making Creative Problem-Solving

See also: What is Empathy? Social Skills

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.1 What Is a Social Problem?

Learning objectives.

- Define “social problem.”

- Explain the objective and subjective components of the definition of a social problem.

- Understand the social constructionist view of social problems.

- List the stages of the natural history of social problems.

A social problem is any condition or behavior that has negative consequences for large numbers of people and that is generally recognized as a condition or behavior that needs to be addressed. This definition has both an objective component and a subjective component.

The objective component is this: For any condition or behavior to be considered a social problem, it must have negative consequences for large numbers of people, as each chapter of this book discusses. How do we know if a social problem has negative consequences? Reasonable people can and do disagree on whether such consequences exist and, if so, on their extent and seriousness, but ordinarily a body of data accumulates—from work by academic researchers, government agencies, and other sources—that strongly points to extensive and serious consequences. The reasons for these consequences are often hotly debated, and sometimes, as we shall see in certain chapters in this book, sometimes the very existence of these consequences is disputed. A current example is climate change : Although the overwhelming majority of climate scientists say that climate change (changes in the earth’s climate due to the buildup of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere) is real and serious, fewer than two-thirds of Americans (64 percent) in a 2011 poll said they “think that global warming is happening”(Leiserowitz, et. al., 2011).

This type of dispute points to the subjective component of the definition of social problems: There must be a perception that a condition or behavior needs to be addressed for it to be considered a social problem. This component lies at the heart of the social constructionist view of social problems (Rubington & Weinberg, 2010). In this view, many types of negative conditions and behaviors exist. Many of these are considered sufficiently negative to acquire the status of a social problem; some do not receive this consideration and thus do not become a social problem; and some become considered a social problem only if citizens, policymakers, or other parties call attention to the condition or behavior.

Sometimes disputes occur over whether a particular condition or behavior has negative consequences and is thus a social problem. A current example is climate change: although almost all climate scientists think climate change is real and serious, more than one-third of the American public thinks that climate change is not happening.

Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

The history of attention given to rape and sexual assault in the United States before and after the 1970s provides an example of this latter situation. These acts of sexual violence against women have probably occurred from the beginning of humanity and certainly were very common in the United States before the 1970s. Although men were sometimes arrested and prosecuted for rape and sexual assault, sexual violence was otherwise ignored by legal policymakers and received little attention in college textbooks and the news media, and many people thought that rape and sexual assault were just something that happened (Allison & Wrightsman, 1993). Thus although sexual violence existed, it was not considered a social problem. When the contemporary women’s movement began in the late 1970s, it soon focused on rape and sexual assault as serious crimes and as manifestations of women’s inequality. Thanks to this focus, rape and sexual assault eventually entered the public consciousness, views of these crimes began to change, and legal policymakers began to give them more attention. In short, sexual violence against women became a social problem.

Before the 1970s, rape and sexual assault certainly existed and were very common, but they were generally ignored and not considered a social problem. When the contemporary women’s movement arose during the 1970s, it focused on sexual violence against women and turned this behavior into a social problem.

Women’s e News – Placards at the Rally To Take Rape Seriously – CC BY 2.0.

The social constructionist view raises an interesting question: When is a social problem a social problem? According to some sociologists who adopt this view, negative conditions and behaviors are not a social problem unless they are recognized as such by policymakers, large numbers of lay citizens, or other segments of our society; these sociologists would thus say that rape and sexual assault before the 1970s were not a social problem because our society as a whole paid them little attention. Other sociologists say that negative conditions and behaviors should be considered a social problem even if they receive little or no attention; these sociologists would thus say that rape and sexual assault before the 1970s were a social problem.

This type of debate is probably akin to the age-old question: If a tree falls in a forest and no one is there to hear it, is a sound made? As such, it is not easy to answer, but it does reinforce one of the key beliefs of the social constructionist view: Perception matters at least as much as reality, and sometimes more so. In line with this belief, social constructionism emphasizes that citizens, interest groups, policymakers, and other parties often compete to influence popular perceptions of many types of conditions and behaviors. They try to influence news media coverage and popular views of the nature and extent of any negative consequences that may be occurring, the reasons underlying the condition or behavior in question, and possible solutions to the problem.

Sometimes a condition or behavior becomes a social problem even if there is little or no basis for this perception. A historical example involves women in college. During the late 1800s, medical authorities and other experts warned women not to go to college for two reasons: they feared that the stress of college would disrupt women’s menstrual cycles, and they thought that women would not do well on exams while they were menstruating.

CollegeDegrees360 – College Girls – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Social constructionism’s emphasis on perception has a provocative implication: Just as a condition or behavior may not be considered a social problem even if there is strong basis for this perception, so may a condition or behavior be considered a social problem even if there is little or no basis for this perception. The “issue” of women in college provides a historical example of this latter possibility. In the late 1800s, leading physicians and medical researchers in the United States wrote journal articles, textbooks, and newspaper columns in which they warned women not to go to college. The reason? They feared that the stress of college would disrupt women’s menstrual cycles, and they also feared that women would not do well in exams during “that time of the month” (Ehrenreich & English, 2005)! We now know better, of course, but the sexist beliefs of these writers turned the idea of women going to college into a social problem and helped to reinforce restrictions by colleges and universities on the admission of women.

In a related dynamic, various parties can distort certain aspects of a social problem that does exist: politicians can give speeches, the news media can use scary headlines and heavy coverage to capture readers’ or viewers’ interest, businesses can use advertising and influence news coverage. News media coverage of violent crime provides many examples of this dynamic (Robinson, 2011; Surette, 2011). The news media overdramatize violent crime, which is far less common than property crime like burglary and larceny, by featuring so many stories about it, and this coverage contributes to public fear of crime. Media stories about violent crime also tend to be more common when the accused offender is black and the victim is white and when the offender is a juvenile. This type of coverage is thought to heighten the public’s prejudice toward African Americans and to contribute to negative views about teenagers.

The Natural History of a Social Problem

We have just discussed some of the difficulties in defining a social problem and the fact that various parties often try to influence public perceptions of social problems. These issues aside, most social problems go through a natural history consisting of several stages of their development (Spector & Kitsuse, 2001).

Stage 1: Emergence and Claims Making

A social problem emerges when a social entity (such as a social change group, the news media, or influential politicians) begins to call attention to a condition or behavior that it perceives to be undesirable and in need of remedy. As part of this process, it tries to influence public perceptions of the problem, the reasons for it, and possible solutions to it. Because the social entity is making claims about all these matters, this aspect of Stage 1 is termed the claims-making process . Not all efforts to turn a condition or behavior into a social problem succeed, and if they do not succeed, a social problem does not emerge. Because of the resources they have or do not have, some social entities are more likely than others to succeed at this stage. A few ordinary individuals have little influence in the public sphere, but masses of individuals who engage in protest or other political activity have greater ability to help a social problem emerge. Because politicians have the ear of the news media and other types of influence, their views about social problems are often very influential. Most studies of this stage of a social problem focus on the efforts of social change groups and the larger social movement to which they may belong, as most social problems begin with bottom-up efforts from such groups.

A social problem emerges when a social change group successfully calls attention to a condition or behavior that it considers serious. Protests like the one depicted here have raised the environmental consciousness of Americans and helped put pressure on businesses to be environmentally responsible.

ItzaFineDay – Financing Climate Change – CC BY 2.0.

Stage 2: Legitimacy

Once a social group succeeds in turning a condition or behavior into a social problem, it usually tries to persuade the government (local, state, and/or federal) to take some action—spending and policymaking—to address the problem. As part of this effort, it tries to convince the government that its claims about the problem are legitimate—that they make sense and are supported by empirical (research-based) evidence. To the extent that the group succeeds in convincing the government of the legitimacy of its claims, government action is that much more likely to occur.

Stage 3: Renewed Claims Making

Even if government action does occur, social change groups often conclude that the action is too limited in goals or scope to be able to successfully address the social problem. If they reach this conclusion, they often decide to press their demands anew. They do so by reasserting their claims and by criticizing the official response they have received from the government or other established interests, such as big businesses. This stage may involve a fair amount of tension between the social change groups and these targets of their claims.

Stage 4: Development of Alternative Strategies

Despite the renewed claims making, social change groups often conclude that the government and established interests are not responding adequately to their claims. Although the groups may continue to press their claims, they nonetheless realize that these claims may fail to win an adequate response from established interests. This realization leads them to develop their own strategies for addressing the social problem.

Key Takeaways

- The definition of a social problem has both an objective component and a subjective component. The objective component involves empirical evidence of the negative consequences of a social condition or behavior, while the subjective component involves the perception that the condition or behavior is indeed a problem that needs to be addressed.

- The social constructionist view emphasizes that a condition or behavior does not become a social problem unless there is a perception that it should be considered a social problem.

- The natural history of a social problem consists of four stages: emergence and claims making, legitimacy, renewed claims making, and alternative strategies.

For Your Review

- What do you think is the most important social problem facing our nation right now? Explain your answer.

- Do you agree with the social constructionist view that a negative social condition or behavior is not a social problem unless there is a perception that it should be considered a social problem? Why or why not?

Allison, J. A., & Wrightsman, L. S. (1993). Rape: The misunderstood crime . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Ehrenreich, B., & English, D. (2005). For her own good: Two centuries of the experts’ advice to women (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., Roser-Renouf, C., & Smith, N. (2011). Climate change in the American mind: Americans’ global warming beliefs and attitudes in May 2011 . New Haven, CT: Yale Project on Climate Change Communication.

Robinson, M. B. (2011). Media coverage of crime and criminal justice . Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

Rubington, E., & Weinberg, M. S. (2010). The study of social problems: Seven perspectives (7th ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Spector, M., & Kitsuse, J. I. (2001). Constructing social problems . New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction.

Surette, R. (2011). Media, crime, and criminal justice: Images, realities, and policies (4th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Social Problems Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

© 2024 Insights – Integrative Psychotherapy Group

What is Social Problem-Solving and Why Is it Important?

- Post date November 29, 2021

We all face social problems. You can be a well-adjusted person and, without fail, you will still come across situations that seem problematic or challenging.

The neighbor above plays loud music late into the evening, keeping you awake.

The boss requests you to take on a project in which you have little to no experience, causing you a high level of anxiety.

You overdraw your bank account after forgetting to account for a new bill.

How we approach these, and other social situations can significantly affect our experiences with others, our world, and our general happiness.

What is Social Problem-Solving?

When you hear “social problem-solving,” do you instantly think about issues you have with others? Do your emotionally distant partner, an overprotective parent, or a supervisor who disagrees with everything you do come to mind?

Certainly, some social problems are people problems. However, many social problems are simply issues we come across in our everyday lives.

To start let’s break down social problems into four simple categories and examples

- Impersonal Problems: You get a flat tire on your way to work.

- Personal Problems: Your depression is affecting your performance at work.

- Interpersonal Problems: Your friend frequently cancels plans on you with little to no notice.

- Community/Societal Problems: The city you live in has increasing levels of poverty and homelessness.

These problems require real-world problem-solving skills. For instance, how would you handle the flat tire? You might call for a tow, stand next to the car trying to flag someone down, or you might get out and change the tire yourself.

Or, you might do something entirely different. We all approach social problems based on our past experiences, wellness, resources, confidence, and support system.

Why is Social Problem-Solving Important?

Think about a problem you had in which you felt you made the wrong decision.

For example, maybe a solution you came up with at work failed to be effective, or you decided not to address a friend who has been distant and now they are angry with you. Making the wrong decision can make you feel shame or hurt, while making the right one can boost feelings of confidence and competence.

But it goes deeper than that. Practical problem-solving skills increase our situational coping, reduce emotional distress, and improve our relationships with others.

Conversely, maladaptive problem-solving skills such as making careless decisions or avoiding decision-making altogether can lead to interpersonal difficulties in relationships, depression, anxiety, and even suicidal ideation.

How Can I Improve My Social Problem-Solving?

Having the skills to approach social problems is critical. There are four crucial steps to social problem-solving.

- Being able to define the problem.

- Finding solutions.

- Choosing a solution.

- Implementing your solution.

Sounds easy enough, right? It can be, but you also need the right mindset. People with positive social problem-solving skills exhibit the following behaviors:

- View problems as challenges or opportunities. It is not always easy to see the positive in a negative situation, but try to see it as an opportunity for growth.

- Belief in themselves. Having self-confidence is crucial. Try to surround yourself with a support system that also believes in your abilities.

- Believe there are solutions to problems. The alternative is giving up. You deserve better.

- Understanding that helpful solutions sometimes take time. Most issues cannot be fixed overnight, and therefore it may take a certain level of resilience on your part to get through the situation.

- Implement solutions promptly. Putting off decisions can only make the problem worse, and it rarely, if ever, solves the issue.

This sounds relatively easy, but our past experiences heavily influence our ability to approach problems and implement solutions. Maybe you are not even sure what the problem is, making it feel impossible to understand and come up with helpful solutions. Therapy can help you work through the decision-making steps, identify any roadblocks and address them in a supportive environment.

If you’re struggling with social problem-solving, Integrative Psychotherapy Group is here to help. Please read more about anxiety therapy and call our office to learn more.

Contact Us About Social Problems

Email Address*

Phone Number*

Message / Concerns

Related Posts

Channeling Your Inner Child: The Importance of Play, Even for Adults

- Post date July 21, 2020

Seasonal Affective Disorder: How to Cope Effectively

- Post date December 21, 2020

- Skip to main content

Teaching SEL

Social Emotional Learning Lessons for Teachers and Counselors

Social Decision Making and Problem Solving

Enhancing social-emotional skills and academic performance.

The approach known as Social Decision Making and Social Problem Solving (SDM/SPS) has been utilized since the late 1970s to promote the development of social-emotional skills in students, which is now also being applied in academic settings. This approach is rooted in the work of John Dewey (1933) and has been extensively studied and implemented by Rutgers University in collaboration with teachers, administrators, and parents in public schools in New Jersey over several decades.

SDM/SPS focuses on developing a set of skills related to social competence, peer acceptance, self-management, social awareness, group participation, and critical thinking.

The curriculum units are structured around systematic skill-building procedures, which include the following components:

- Introducing the skill concept and motivation for learning; presentation of the skill in concrete behavioral components

- Modeling behavioral components and clarifying the concept by descriptions and behavioral examples of not using the skill

- Offering opportunities for practice of the skill in “student-tested,” enjoyable activities, providing corrective feedback and reinforcement until skill mastery is approached

- Labeling the skill with a prompt or cue, to establish a “shared language” that can be used for future situations

- Assigning skill practice outside of structured lessons

- Providing follow-through activities and integrating prompts in academic content areas and everyday interpersonal situations

Connection to Academics

Integrating SDM/SPS into students’ academic work enhances their social-emotional skills while enriching their academic performance. Research consistently supports the benefits of social-emotional learning (SEL) instruction.

Readiness for Decision Making

This aspect of SDM/SPS targets the development of skills necessary for effective social decision making and interpersonal behavior across various contexts. It encompasses self-management and social awareness. A self-management unit focuses on skills such as listening, following directions, remembering, taking turns, and maintaining composure in the classroom. These skills help students regulate their emotions, control impulsivity, and develop social literacy. Students learn to recognize physical cues and situations that may trigger high-arousal, fight-or-flight reactions or dysregulated behavior. Skills taught in this domain should include strategies to regain control and engage clear thinking, such as breathing exercises, mindfulness, or techniques that activate the parasympathetic nervous system.

A social awareness unit emphasizes positive peer relationships and the skills necessary for building healthy connections. Students learn to respond positively to peers who offer praise, compliments, and express positive emotions and appreciation. Skills in this unit also include recognizing when peers need help, understanding when they should seek help from others, and learning how to ask for help themselves. Students should develop the ability to provide and receive constructive criticism and collaborate effectively with diverse peers in group settings.

Decision Making Framework – FIG TESPN

To equip students with a problem-solving framework, SDM/SPS introduces the acronym FIG TESPN. This framework guides students when faced with problems or decisions and aims to help them internalize responsible decision making. The goal is for students to apply this framework academically and personally, even in challenging and stressful situations.

FIG TESPN stands for:

- (F)eelings are my cue to problem solve.

- (I) have a problem.

- (G)oals guide my actions.

- (T)hink of many possible things to do.

- (E)nvision the outcomes of each solution.

- (S)elect your best solution, based on your goal.

- (P)lan, practice, anticipate pitfalls, and pursue your best solution.

- (N)ext time, what will you do – the same thing or something different?

Integration of FIG TESPN into academics

Once students have become familiar with the FIG TESPN framework, there are limitless opportunities for them to apply and practice these skills. Many of the texts students read involve characters who make decisions, face conflicts, deal with intense emotions, and navigate complex interpersonal situations. By applying the readiness skills and FIG TESPN framework to these assignments, students can meet both academic and social-emotional learning (SEL) state standards.

Teachers and staff play a crucial role in modeling readiness skills and the use of FIG TESPN. They can incorporate these skills into their questioning techniques, encouraging individual students and groups to think critically when confronted with problems. This approach helps students internalize the problem-solving framework and develop their decision-making abilities.

By integrating social decision making and problem-solving skills into academic subjects such as social studies, social justice, ethics, and creative writing, students gain a deeper understanding of the FIG TESPN framework. The framework becomes an integral part of their learning experience and supports their growth in both academic and social-emotional domains.

SDM/SPS Applied to Literature Analysis

- Think of an event in the section of the book assigned. When and where did it happen? Put the event into words as a problem.

- Who were the people that were involved in the problem? What were their different feelings and points of view about the problem? Why did they feel as they did? Try to put their goals into words.

- For each person or group of people, what are some different decisions or solutions to the problem that he,she, or they thought of that might help in reaching their goals?

- For each of these ideas or options, what are all of the things that might happen next? Envision and write both short- and long-term consequences.

- What were the final decisions? How were they made? By whom? Why? Do you agree or disagree? Why?

- How was the solution carried out? What was the plan? What obstacles were met? How well was the problem solved? What did you read that supports your point of view?

- Notice what happened and rethink it. What would you have chosen to do? Why?

- What questions do you have, based on what you read? What questions would you like to be able to ask one or more of the characters? The author? Why are these questions important to you?

a simplified version…

- I will write about this character…

- My character’s problem is…

- How did your character get into this problem?

- How does the character feel?

- What does the character want to happen?

- What questions would you like to be able to ask the character you picked, one of the other characters, or the author?

SDM/SPS Applied to Social Studies

- What is the event that you are thinking about? When and where is it happening? Put the event into words as a problem, choice, or decision.

- What people or groups were involved in the problem? What are their different feelings? What are their points of view about the problem?

- What do each of these people or groups want to have happen? Try to put their goals into words.

- For each person or group, name some different options or solutions to the problem that they think might help them reach their goals. Add any ideas that you think might help them that they might not have thought of.

- For each option or solution you listed, picture all the things that might happen next. Envision long- and short-term consequences.

- What do you think the final decision should be? How should it be made? By whom? Why?

- Imagine a plan to help you carry out your solution. What could you do or think of to make your solution work? What obstacles or roadblocks might keep your solution from working? Who might disagree with your ideas? Why? What else could you do?

- Rethink it. Is there another way of looking at the problem that might be better? Are there other groups, goals, or plans that come to mind?

Applying FIG TESPN to Emigration

- What countries were they leaving?

- How did they feel about leaving their countries?

- What problems were going on that made them want to leave?

- What problems would leaving the country bring about?

- What would have been their goals in leaving or staying?

- What were their options and how did they envision the results of each possibility?

- What plans did they have to make? What kinds of things got in their way at the last minute? How did they overcome the roadblocks?

- Once they arrived in a new country, how did they feel? What problems did they encounter at the beginning? What were their first goals?

Adapted from: Fostering Social-Emotional Learning in the Classroom

Teach social problem solving

For student year, helps students to.

- solve social problems

- become independent

Helps teachers to

- support students

- model strategies

Social problem solving is a skill that develops during the early years of school. It is the process and strategies used to analyse, understand, and respond to everyday problems, decision making, and conflicts.

Social problem solving is often fostered intuitively through interactions with others. Some students, including those on the autism spectrum, may benefit from systematic instruction in helpful strategies for social problem solving.

Social problems can be as simple as turn-taking, and as complex as bullying.

Instruction helps students to understand:

- what a social problem is

- how to recognise a social problem

- the process to follow when a social problem occurs, and

- the strategies they could use to solve a social problem.

How the practice works

Watch this video to learn more about this practice.

Duration: 03:49

Australian Professional Standards for Teachers related to this practice

1.6 - strategies to support the full participation of students with disability

4.1 - support student participation

4.2 - manage classroom activities

4.3 - manage challenging behaviour

For further information, see Australian Professional Standards for Teachers AITSL page

Join the inclusionED community

View this content in full by creating a free account..

Already have an account? Log in

Preparing to teach

Be proactive.

- Identify barriers to learning and social demands and put these strategies in place to reduce the likelihood of problems occurring in the first place.

- Use observations to develop a clear and comprehensive understanding of the problem(s) that the student is experiencing.

- understand possible triggers

- be alert to any potentially challenging situations throughout the day.

- Identify the specific strategy to teach students how to find a solution. There are several strategies available in the Resources section below.

- as a whole class

- in small groups

- individually

- a mix of above.

Use supports

- Identify and develop the visual supports required to explicitly and systematically teach a social problem solving process and keep these handy. These can be social stories, routine charts, or emotion cards for self-regulation.

- Identify appropriate storybooks and visual supports that you can incorporate in your explicit teaching to enhance student understanding.

- role-play/rehearsal

- puppet play (check the students aren’t frightened of puppets)

- social stories

- visual prompts.

How will you:

- embed problem solving scenarios

- model the problem solving process

- positively encourage, support, and reinforce students to use the process to solve real-life social problems

- share the social problem solving process with families.

Communicate

Communicating with families will encourage generalisation of the associated strategy at home. You can also communicate the types of language used so families can use similar language at home if they like.

The turtle technique

When you have a clear and understanding of the problem the student is experiencing, you can then identify and use a specific intervention process to teach the student how to find a solution. One such process is the turtle technique. This which involves teaching students the steps of how to control feelings and calm down (i.e., think like a turtle).

You will find further templates in the resource section of this practice.

It works better if:

- the social problem solving strategy has a small number of set steps

- teachers model these steps

- students are encouraged to use to the strategy to solve their social problems whenever they occur

- language is used consistently and modelled throughout the day and at home

- visual supports are used to enhance student understanding of the strategy.

It doesn’t work if:

- the student is expected to solve a social problem when distressed or overloaded

- the student hasn’t understood the problem solving strategy (so it will need re-teaching)

- the problem solving strategy has too many steps.

In the classroom