Language Barrier in Education and Social Life Research Paper

Immigration causes differences in language and lifestyle. Language barriers refer to challenges experienced when one tries to communicate with an individual or people who speak a different language. This phenomenon is common in areas where there is a conglomeration of people from diverse backgrounds like culture and nationality. The term is also used to refer to problems encountered by immigrants when learning a foreign language (Kim & Mattila, 2011).

Due to these challenges, there have been efforts to eliminate or reduce the impact of these differences especially in international learning institutions. Differences in language cause difficulties in education and even social life and can be solved in many ways to become less problematic. Consequently, immigrants should be aware of language differences before moving, and this problem can be solved in a short period of time.

Language differences cause a major barrier in communication. Under normal circumstances, communication can only take place if there is a common language to be used as a link between the communicating parties.

It is quite common among immigrants, who find themselves in a foreign country, which uses a different language from his or her home language (Kim & Mattila, 2011). Because of this barrier, affected immigrants are prone to misunderstanding, since the information passed across cannot be accurately interpreted. What are some of these language differences?

As an element of cultural identity, human language is diverse and unique. For instance, English speakers are likely to encounter communication problems when interacting with Frenchmen because of the disjoint nature of the languages being used. Besides language uniqueness, the difference in accent affects the attainment of effective communication.

It is not surprising that some English-speaking students find the American accent to be a barrier to effective communication (Kim & Mattila, 2011). This problem arises from the fact that British English is more preferred by most international students and other immigrants. While this is the case, there are distinctive features, which define language accent.

These include pronunciations, stress and intonations. For the case of these immigrants, the problem of accent is usually complicated because of the diverse nature of the American culture. This is to mean that people from certain regions within the country may not understand one another, and the problem worsens when a third party from a different country is included (Green, 2009).

Another language difference that acts as a communication barrier is the presence of phrases and idioms. In the case of American English, communication involves the usage of an array of phrases and idioms, which carry meanings that are different from the literal meaning of the root words used (Green, 2009).

This can be a major communication problem, especially when immigrants do not have exposure to the phrases and idioms, which are commonly used. Many would get confused and misunderstood because of these distinctive differences.

Language structure also creates differences among world languages, thus affecting immigrants. A good example is the universally recognized sentence structure of subject-verb-object in English (Green, 2009). This broadly differs from Japanese sentence structure, subject-object-verb. Additionally, some international languages contain suffixes, which cannot be converted into another language, say English.

As a result, immigrants from such language backgrounds are likely to experience communication difficulties. Other factors include but not limited to culture, slang and language style. However, these barriers shouldn’t be problems when adapting new environments. This can be realized through familiarization of another country’s language before immigrating (Cronjé, 2009).

Language differences shouldn’t be a barrier in education because of the essence of learning, language is one of the things people learn. As an immigrant, it is important to have the willingness to learn new culture, which includes language, behavior and even lifestyle. While one may decide not to conform to a new country’s behavior, it is never optional to learn a new language in a foreign country (Cronjé, 2009).

In fact, it is believed that the process of learning a new language ought to be considered as an adaptive approach in overcoming a wide range of barriers encountered by immigrants. For one to be comfortable with learning a new language, it is essential to understand the pronunciation. As mentioned before, people from different countries pronounce words differently.

It is therefore, crucial for foreign students to identify difficult sounds for daily practice until confidence is gained. Additionally, learning preference should be given to words that are commonly used together with short phrases. For this to be successful, the learner needs to have an educated speaker who can help in correcting pronunciation mistakes (Cronjé, 2009).

Besides pronunciation, immigrants need to understand rhythm, intonation and stress, commonly used by native speakers of the foreign language. The simplest way of learning these elements is through imitation of native people that are educated. One can listen to some statements repetitively using audio and video tools (Cronjé, 2009).

This can be followed by trying to say the same phrases using a recording machine. In order for this to work, one has to repeat the process severally with an educated speaker for corrections. Skills gained from pronunciation lessons are essential in eliminating chances of misunderstandings during communication. Another way of learning a foreign language with ease is through borrowing or purchasing relevant materials, which are used by language learners.

These may include but not limited to dictionaries, audio textbooks and translation dictionaries (Sherry, Thomas & Wing, 2010). These tools help in minimizing language differences and communication barriers within a short period of time.

Although language differences could be a communication barrier, there are several methods of communication, which have been developed to overcome these challenges. In other words, there are numerous ways of conversing smoothly without acquiring foreign language proficiency (Sherry, Thomas & Wing, 2010).

For instance, it is possible to pass across information through written communication, which is a common method applied when dealing with figures and facts. Additionally, this method of communication is the most preferred when making presentations. Although it may have limitations to a person learning a new language, it is easy to keep record and make corrections where necessary.

Another commonly used method of communication today by language learners is nonverbal communication. This does not make use of oral communication skills and one may find it relevant, especially when he or she is still new in a foreign country. Nonverbal communication is also referred to as body language. It encompasses an array of elements, including gestures, actions and facial expressions (Smitherman, 2003).

With this approach, it is possible to communicate without necessarily speaking. In cases where both oral and nonverbal communication is used, harmony is essential to avoid misunderstanding and confusion. Nonetheless, variation and understanding of the sign language may pose a challenge, especially when the other party is new to it.

Although some people view language differences lightly, it is regarded as a major communication issue. This is based on the fact that poor communication has a wide range of negative effects, which are experienced in schools, health centers and in other settings (Smitherman, 2003). The most detrimental effect of language barriers is misunderstandings, arising from communication gaps.

Misunderstandings emanate from several instances, including, the use of slang or jargons, which are not universally recognized. Additionally, misunderstandings may arise from variation in accents due to diverse backgrounds and culture. It is doubtless that most conflicts in schools, families and even offices arise from misunderstandings. In essence, misunderstandings can breed frustrations and stress when a person is new in a foreign country.

In some cases, these misunderstandings have been closely linked to emerging cases of stress among foreign students (Smitherman, 2003). One may feel out of place when he or she can neither get what is being communicated nor share ideas effectively. As a result of stress and disconnection from the surrounding immigrants, they may opt to be alone by excluding themselves from joint activities like playing and academic group discussions.

Language barriers are also a major problem in written communication. Foreign students who do not understand the native language used in learning institutions find hardships in understanding lecture notes and other study materials (Roush, 2008). This is also experienced in written exams where students may have a correct idea, expressed wrongly due to ineffective communication.

In extreme cases of such misunderstandings in written communications, students may end up failing their exams or scoring low grades. The negative impact of language barriers can also be experienced in the corporate world. Oftentimes, immigrants looking for employment in foreign countries fail interview tests because of language barriers.

Due to communication gaps, employers might not see the value in a foreign applicant. This may emanate from language mistakes or wrong answering of questions caused by poor understanding of the language being used (Roush, 2008). Foreign students seeking admissions in learning institutions may also be less considered because of their ineffective communication skills.

Language barriers may also trigger cultural conflicts. For instance, different cultures have different ways of greeting each other or expressing gratitude. Based on such variations, it is possible for miscommunications to arise when certain things are not done the way they have been done before in one’s home country (Sherry, Thomas & Wing, 2010). This is therefore, a major challenge, which immigrants need to beware of before going to study or work a foreign country.

As globalization takes center stage and countries get smaller every day, there are new ways of communication that are being adopted. One of these approaches is language. The role played by any language, whether local or international is always immeasurable (Green, 2009). As discussed above, the purpose of a language gets undermined when there are differences, which breed communication barriers.

These barriers are common in settings, which have immigrants, who do not understand the native language of the foreign country. In fact, it is believed that poor communication stems from a plethora of issues, language barrier being one of them. It is highly advisable for immigrants to beware of language differences before moving, and this problem can be solved in a short period of time.

Cronjé, J. C. (2009). Qualitative assessment across language barriers: An action research study. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 12 (2), 69-85.

Green, D. A. (2009). New academics’ perceptions of the language of teaching and learning: identifying and overcoming linguistic barriers. International Journal for Academic Development, 14 (1), 33-45.

Kim, E. & Mattila, A. (2011). The Impact of Language Barrier & Cultural Differences on Restaurant Experiences: A Grounded Theory Approach. University of Massachusetts Amherst . Web.

Roush, V. (2008). A Rational Approach to Race Relations: A Guide to Talking Straight about Contemporary Race Issues . Indiana: iUniverse.

Sherry, M., Thomas, P., & Wing, C. (2010). International students: a vulnerable student population. Higher Education, 60 (1), 33-46.

Smitherman, G. (2003). Talking that Talk: Language, Culture and Education in African America. London: Routledge.

- Teaching Speaking and Pronunciation

- Ratatouille 2007: Animation Accent

- P and B Pronunciation Among Arab Learners

- Foreign Language and Communication

- How Cultural Beliefs, Values, Norms and Practices Influence Communication

- Online Social Networks and Deontology

- Social Networks From Utilitarian Perspective

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Using Facebook in Modern Society

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, April 3). Language Barrier in Education and Social Life. https://ivypanda.com/essays/language-barrier-in-education-and-social-life/

"Language Barrier in Education and Social Life." IvyPanda , 3 Apr. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/language-barrier-in-education-and-social-life/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Language Barrier in Education and Social Life'. 3 April.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Language Barrier in Education and Social Life." April 3, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/language-barrier-in-education-and-social-life/.

1. IvyPanda . "Language Barrier in Education and Social Life." April 3, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/language-barrier-in-education-and-social-life/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Language Barrier in Education and Social Life." April 3, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/language-barrier-in-education-and-social-life/.

About . Click to expand section.

- Our History

- Team & Board

- Transparency and Accountability

What We Do . Click to expand section.

- Cycle of Poverty

- Climate & Environment

- Emergencies & Refugees

- Health & Nutrition

- Livelihoods

- Gender Equality

- Where We Work

Take Action . Click to expand section.

- Attend an Event

- Partner With Us

- Fundraise for Concern

- Work With Us

- Leadership Giving

- Humanitarian Training

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Donate . Click to expand section.

- Give Monthly

- Donate in Honor or Memory

- Leave a Legacy

- DAFs, IRAs, Trusts, & Stocks

- Employee Giving

Language barriers in the classroom: From mother tongue to national language

Sep 23, 2019 | By: Kieran McConville

Back to school has a whole new meaning when it’s not taking place in your mother tongue. We're working to break down language barriers in the classroom. One solution? Give children more time to transition from their mother tongue to their national language.

Picture it: You show up for your first day at school, and the teacher starts talking to you in a language you don’t understand. You’re now expected to learn to read and write in this language. Imagine if there were two new languages for you to learn. One more thing: You're only 4 years old.

For most kids in Kenya , that’s exactly the scenario they face when starting school. Language barriers in the classroom are ubiquitous in a country that has 2 official languages and 66 local languages. In Marsabit, the first language for most children is Borana. Once they start school, they must learn two new languages to understand their teachers: Swahili and English..

From an educational perspective, the results are disastrous. UNESCO estimates that 40% of school-aged children don’t have access to education in a language that they understand.

If all students had basic literacy skills, UNESCO estimates that 171 million people could escape extreme poverty. Language barriers mean that, despite years of schooling, many students end up essentially illiterate.

Language Barriers In The Classroom Leave Kids Behind From The Start

Despite years of schooling, many language minority students end up essentially illiterate.

“What we learned [from carrying out assessments] is that, by the time they’re in grades six, seven, and eight, children still can’t read and can’t write,” said Concern Kenya Country Director Wendy Erasmus. “They can recite what’s in a book — but they don’t understand it.”

Of course, it’s not just a Kenyan problem. Thousands of miles across the Atlantic in Haiti, classes are taught in French and Haitian Creole. However, either or both of these are foreign languages for many Haitian children. A World Bank-supported study showed that 76% of first graders, 49% of second graders, and 29% of third graders could not read a single word of Haitian Creole. Similar results were found when the same students were tested in French.

How Language Barriers Keep Language Minority Families In Poverty

For any student, basic literacy and numeracy skills are key to building a quality education. Even with just basic reading skills in place, UNESCO estimates that 171 million people could escape extreme poverty. Imagine the waste of going through an entire childhood worth of schooling, and still be unable to read.

Students learning a second language often struggle to express themselves if they don’t have a full command of that language, notes John Schumann of UCLA’s Department of Applied Linguistics. This can lead to emotional stress and affect their ability to learn.

Parents may also not speak the language used in school. This hinders progress even further when they can't understand their children’s homework in order to help them complete it.

As UNESCO notes, language is a double-edged sword. “While it strengthens an ethnic group’s social ties and sense of belonging, it can also become a basis for their marginalization.”

Rewriting The Rules — In The Mother Tongue

One solution to these language barriers is the concept of teachers leading earlier grades in the students’ first language. Tests in both Kenya and Haiti , as well as Liberia and Niger , showed promising results.

“Children can get comfortable with reading and writing in a language that they know,” explains Wendy Erasmus in Kenya. “Then over year three and four they phase into English and Swahili.What we’ve seen is terribly exciting… an impressive increase in these children’s ability to read and write.”

This method is in line with UNESCO’s recommendation for early teaching in the mother tongue. Gains from this early education will be sustained as students transition into classes taught in a national language. Bilingual training for teachers is also a critical element for success.

Concern has been supporting these initiatives with curriculum design, training classroom teachers, and providing learning materials.

“A Continuation Of What They Have Learned At Home.”

Meanwhile, in the second grade classroom of St. Peter’s Primary School in Sagante, Kenya, teacher Mr. Sode asks a question in Borana. In response, 6–year-old Daki Guyo enthusiastically leaps to her feet. It’s plain to see that she knows the topic and is eager to show off her knowledge.

Watching on, Concern’s Benson Thuku remarks, “This really enables children to learn in school more effectively, because it is a continuation of what they have learned at home… and what they learn in school is also reinforced at home.”

Add Impact to Your Inbox

11 Unexpected barriers to education around the world

What does Quality Education mean? Breaking down SDG #4

How does education affect poverty? It can help end it.

Sign up for our newsletter.

Get emails with stories from around the world.

You can change your preferences at any time. By subscribing, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

Advertisement

Language and communication in international students’ adaptation: a bibliometric and content analysis review

- Open access

- Published: 12 July 2022

- Volume 85 , pages 1235–1256, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Michał Wilczewski ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7650-5759 1 &

- Ilan Alon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6927-593X 2 , 3

17k Accesses

15 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This article systematically reviews the literature (313 articles) on language and communication in international students’ cross-cultural adaptation in institutions of higher education for 1994–2021. We used bibliometric analysis to identify the most impactful journals and articles, and the intellectual structure of the field. We used content analysis to synthesize the results within each research stream and suggest future research directions. We established two major research streams: second-language proficiency and interactions in the host country. We found inconclusive results about the role of communication with co-nationals in students’ adaptation, which contradicts the major adaptation theories. New contextualized research and the use of other theories could help explain the contradictory results and develop the existing theories. Our review suggests the need to theoretically refine the interrelationships between the interactional variables and different adaptation domains. Moreover, to create a better fit between the empirical data and the adaptation models, research should test the mediating effects of second-language proficiency and the willingness to communicate with locals. Finally, research should focus on students in non-Anglophone countries and explore the effects of remote communication in online learning on students’ adaptation. We document the intellectual structure of the research on the role of language and communication in international students’ adaptation and suggest a future research agenda.

Similar content being viewed by others

A systematic narrative synthesis review of the effectiveness of genre theory and systemic functional linguistics for improving reading and writing outcomes within K-10 education

Teacher-Student Interactions: Theory, Measurement, and Evidence for Universal Properties That Support Students’ Learning Across Countries and Cultures

Cultural Implications in Educational Technology: A Survey

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the consequences of globalization is the changing landscape of international higher education. Over the past two decades, there has been a major increase in the number of international students, that is, those who have crossed borders for the purpose of study (OECD, 2021a ), from 1.9 million in 1997 to over 6.1 million in 2019 (UIS Statistics, 2021 ). Even students who are motivated to develop intercultural competence by studying abroad (Jackson, 2015 ) face several challenges that prevent them from benefitting fully from that experience. Examples of these challenges include language and communication difficulties, cultural and educational obstacles affecting their adaptation, socialization, and learning experiences (Andrade, 2006 ), psychological distress (Smith & Khawaja, 2011 ), or social isolation and immigration and visa extension issues caused by Covid-19 travel restrictions (Hope, 2020 ).

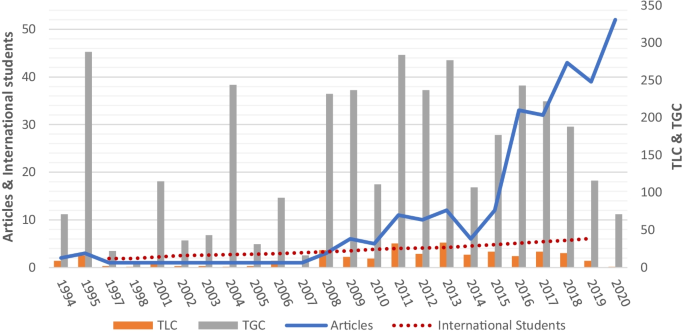

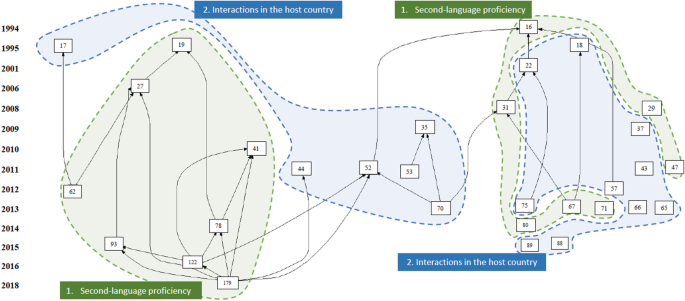

Cross-cultural adaptation theories and empirical research (for reviews, see Andrade, 2006 ; Smith & Khawaja, 2011 ) confirm the critical importance of foreign-language and communication skills and transitioning to the host culture for a successful academic and social life. Improving our understanding of the role of foreign-language proficiency and communication in students’ adaptation is important as the number of international students in higher education worldwide is on the rise. This increase has been accompanied by a growing number of publications on this topic over the last decade (see Fig. 1 ). Previous reviews of the literature have identified foreign-language proficiency and communication as predictors of students’ adaptation and well-being in various countries (Smith & Khawaja, 2011 ). The most recent reviews (Jing et al., 2020 ) list second-language acquisition and cross-cultural adaptation as among the most commonly studied topics in international student research. However, to date, there are no studies specifically examining the role of language and communication in international students’ adaptation (henceforth “language and communication in student adaptation”). This gap is especially important given recent research promoting students’ self-formation (Marginson, 2014 ) and reciprocity between international and domestic students (Volet & Jones, 2012 ). The results challenge the traditional “adjustment to the host culture” paradigm whereby international students are treated as being out of sync with the host country’s norms (Marginson, 2014 ). Thus, this article differs from prior research by offering a systematic and in-depth review of the literature on language and communication in student adaptation using bibliometric co-citation analysis and qualitative content analysis. Our research has a methodological advantage in using various bibliometric tools, which should improve the validity of the results.

Source: HistCite). Note . TLC, total local citations received; TGC, total global citations received; Articles, number of articles published in the field; International Students, number (in millions) of international students worldwide (UIS Statistics, 2021 )

Yearly publication of articles on language and communication in student adaptation (

We focus on several questions:

What are the most impactful journals and articles about the role of language and communication in student adaptation?

What is the thematic structure of the research in the field?

What are the leading research streams investigating language and communication in student adaptation?

What are the effects of language and communication on student adaptation?

What are the future research directions?

After introducing the major concepts related to language and communication in student adaptation and the theoretical underpinnings of the field, we present our methodology. Using bibliometric and content analysis, we track the development of the field and identify the major themes, research streams, and studies that have shaped the state-of-the art and our current knowledge about the role of language and communication in student adaptation. Finally, we suggest avenues for future research.

Defining the concepts and theories related to language and communication in student adaptation

Concepts related to language and communication.

Culture is a socially constructed reality in which language and social practices interact to construct meanings (Burr, 2006 ). In this social constructionist perspective, language is viewed as a form of social action. Intertwined with culture, it allows individuals to communicate their knowledge about the world, as well as the assumptions, opinions, and viewpoints they share with other people (Kramsch, 1998 ). In this sense, people identify themselves and others through the use of language, which allows them to communicate their social and cultural identity (Kramsch, 1998 ).

Intercultural communication refers to the process of constructing shared meaning among individuals with diverse cultural backgrounds (Piller, 2007 ). Based on the research traditions in the language and communication in student adaptation research, we view foreign or second-language proficiency , that is, the skill allowing an individual to manage communication interactions in a second language successfully (Gallagher, 2013 ), as complementary to communication (Benzie, 2010 ).

Cross-cultural adaptation

The term adaptation is used in the literature interchangeably with acculturation , adjustment , assimilation , or integration . Understood as a state, cultural adaptation refers to the degree to which people fit into a new cultural environment (Gudykunst and Hammer, 1988 ), which is reflected in their psychological and emotional response to that environment (Black, 1990 ). In processual terms, adaptation is the process of responding to the new environment and developing the ability to function in it (Kim, 2001 ).

The literature on language and communication in student adaptation distinguishes between psychological, sociocultural, and academic adaptation. Psychological adaptation refers to people’s psychological well-being, reflected in their satisfaction with relationships with host nationals and their functioning in the new environment. Sociocultural adaptation is the individual’s ability to fit into the interactive aspects of the new cultural environment (Searle and Ward, 1990 ). Finally, academic adaptation refers to the ability to function in the new academic environment (Anderson, 1994 ). We will discuss the results of the research on language and communication in student adaptation with reference to these adaptation domains.

Theoretical underpinnings of language and communication in student adaptation

We will outline the major theories used in the research on international students and other sojourners, which has recognized foreign-language skills and interactions in the host country as critical for an individual’s adaptation and successful international experience.

The sojourner adjustment framework (Church, 1982 ) states that host-language proficiency allows one to establish and maintain interactions with host nationals, which contributes to one’s adaptation to the host country. In turn, social connectedness with host nationals protects one from psychological distress and facilitates cultural learning.

The cultural learning approach to acculturation (Ward et al., 2001 ) states that learning culture-specific skills allows people to handle sociocultural problems. The theory identifies foreign-language proficiency (including nonverbal communication), communication competence, and awareness of cultural differences as prerequisites for successful intercultural interactions and sociocultural adaptation (Ward et al., 2001 ). According to this approach, greater intercultural contact results in fewer sociocultural difficulties (Ward and Kennedy, 1993 ).

Acculturation theory (Berry, 1997 , 2005 ; Ward et al., 2001 ) identifies four acculturation practices when interacting with host nationals: assimilation (seeking interactions with hosts and not maintaining one’s cultural identity), integration (maintaining one’s home culture and seeking interactions with hosts), separation (maintaining one’s home culture and avoiding interactions with hosts), and marginalization (showing little interest in both maintaining one’s culture and interactions with others) (Berry, 1997 ). Acculturation theory postulates that host-language skills help establish supportive social and interpersonal relationships with host nationals and, thus, improve intercultural communication and sociocultural adjustment (Ward and Kennedy, 1993 ).

The anxiety/uncertainty management (AUM) theory (Gudykunst, 2005 ; Gudykunst and Hammer, 1988 ) states that intercultural adjustment is a function of one’s ability to cope with anxiety and uncertainty caused by interactions with hosts and situational processes. People’s ability to communicate effectively depends on their cognitive resources (e.g., cultural knowledge), which helps them respond to environmental demands and ease their anxiety.

The integrative theory of communication and cross-cultural adaptation (Kim, 2001 ) posits that people’s cultural adaptation is reflected in their functional fitness, meaning, the degree to which they have internalized the host culture’s meanings and communication symbols, their psychological well-being, and the development of a cultural identity (Kim, 2001 ). Communication with host nationals improves cultural adaptation by providing opportunities to learn about the host country’s society and culture, and developing intercultural communication competence that includes the ability to receive and interpret comprehensible messages in the host environment.

The intergroup contact theory (Allport, 1954 ; Pettigrew, 2008 ) states that contact between two distinct groups reduces mutual prejudice under certain conditions: when groups have common goals and equal status in the social interaction, exhibit intergroup cooperation, and have opportunities to become friends. Intercultural contact reduces prejudice toward and stereotypical views of the cultural other and provides opportunities for cultural learning (Allport, 1954 ).

These theories provide the theoretical framework guiding the discussion of the results synthesized through the content analysis of the most impactful articles in the field.

Methodology

Bibliometric and content analysis methods.

We used a mixed-method approach to review the research on language and communication in student adaptation for all of 1994–2021. This timeframe was informed by the data extraction process described in the next section. Specifically, we conducted quantitative bibliometric analyses such as co-citation analysis, keyword co-occurrence analysis, and conceptual thematic mapping, as well as qualitative content analysis to explore the research questions (Bretas & Alon, 2021 ).

Bibliometric methods use bibliographic data to identify the structures of scientific fields (Zupic and Čater, 2015 ). Using these methods, we can create an objective view of the literature by making the search and review process transparent and reproducible (Bretas and Alon, 2021 ). First, we measured the impact of the journals and articles by retrieving data from HistCite concerning the number of articles per journal and citations per article. We analyzed the number of total local citations (TLC) per year, that is, the number of times an article has been cited by other articles in the same literature (313 articles in our sample). We then analyzed the total global citations (TGC) each article received in the entire Web of Science (WoS) database. We also identified the trending articles in HistCite by calculating the total citation score (TLCe) at the end of the year covered in the study (mid-2021). This score rewards articles that received more citations within the last three years (i.e., up to the beginning of 2018). Using this technique, we can determine the emerging topics in the field because it considers not only articles with the highest number of citations received over a fixed period of time, but also those that have been cited most frequently in recent times (Alon et al., 2018 ).

Second, to establish a general conceptual structure of the field, we analyzed the co-occurrence of authors’ keywords using VOS software. Next, based on the authors’ keywords, we plotted a conceptual map using Biblioshiny (a tool for scientific mapping analysis that is part of the R bibliometrix-package) to identify motor, basic, niche, and emerging/declining themes in the field (Bretas and Alon, 2021 ).

Third, to determine specific research streams and map patterns within the field (Alon et al., 2018 ), we used the co-citation mapping techniques in HistCite that analyze and visualize citation linkages between articles (Garfield et al., 2006 ) over time.

Next, we used content analysis to synthesize the results from the 31 most impactful articles in the field. We analyzed the results within each research stream and discussed them in light of the major adaptation theories to suggest future research directions and trends within each research stream (Alon et al., 2018 ). Content analysis allows the researcher to identify the relatively objective characteristics of messages (Neuendorf, 2002 ). Thus, this technique enabled us to verify and refine the results produced by the bibliometric analysis, with the goal of improving their validity.

Data extraction

We extracted the bibliographic data from Clarivate Analytics’ WoS database that includes over 21,000 high-quality, peer-reviewed scholarly journals (as of July 2020 from clarivate.libguides.com). We adopted a two-stage data extraction approach (Alon et al., 2018 ; Bretas and Alon, 2021 ). Table 1 describes the data search and extraction processes.

First, in June 2021, we used keywords that would best cover the researched topic by searching for the following combinations of terms: (a) “international student*” OR “foreign student*” OR “overseas student*” OR “study* abroad” OR “international education”—to cover international students as a specific sojourner group; (b) “language*” and “communicat*”—to cover research on foreign-language proficiency as well as communication issues; and (c) “adapt*” OR “adjust*” OR “integrat*” OR “acculturat*”—to cover the adaptation aspects of the international students’ experience. However, given that cross-cultural adaptation is reflected in an individual’s functional fitness, psychological well-being, and development of a cultural identity (Kim, 2001 ), we included two additional terms in the search: “identit*” OR “satisf*”—to cover the literature on the students’ identity issues and satisfaction in the host country. Finally, based on a frequency analysis of our data extracted in step 2, we added “cultur* shock” in step 3 to cover important studies on culture shock as one of critical aspects of cross-cultural adaptation (Gudykunst, 2005 ; Pettigrew, 2008 ; Ward et al., 2001 ). After refining the search by limiting the data to articles published in English, the extraction process yielded 921 sources in WoS.

In the second stage, we refined the extraction further through a detailed examination of all 921 sources. We carefully read the articles’ abstracts to identify those suitable for further analysis. If the abstracts did not contain one or more of the three major aspects specified in the keyword search (i.e., international student, language and communication, adaptation), we studied the whole article to either include or exclude it. We did not identify any duplicates, but we removed book chapters and reviews of prior literature that were not filtered out by the search in WoS. Moreover, we excluded articles that (a) reported on students’ experiences outside of higher education contexts; (b) dealt with teaching portfolios, authors’ reflective inquiries, or anecdotal studies lacking a method section; (c) focused on the students’ experience outside the host country or on the experience of other stakeholders (e.g., students’ spouses, expatriate academics); (d) used the terms “adaptation,” “integration,” or “identity” in a sense different from cultural adaptation (e.g., adaptation of a syllabus/method/language instruction; integration of research/teaching methods/technology; “professional” but not “cultural” identity); or (e) used language/communication as a dependent rather than an independent variable. This process yielded 313 articles relevant to the topic. From them, we extracted the article’s title, author(s) names and affiliations, journal name, number, volume, page range, date of publication, abstract, and cited references for bibliometric analysis.

In a bibliometric analysis, the article is the unit of analysis. The goal of the analysis is to demonstrate interconnections among articles and research areas by measuring how many times the article is (co)cited by other articles (Bretas & Alon, 2021 ).

- Bibliometric analysis

Most relevant journals and articles

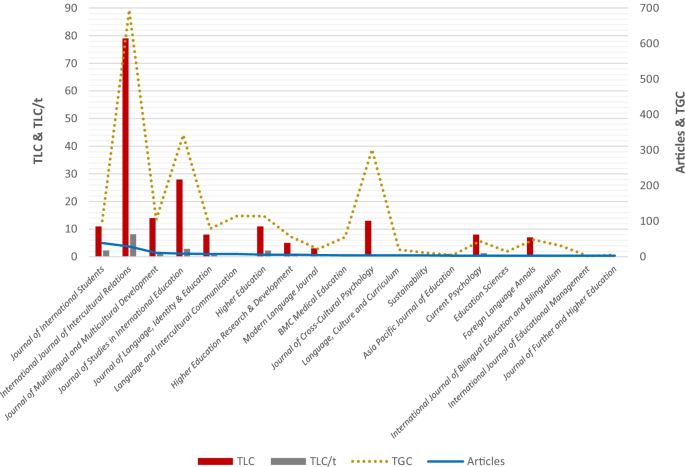

We addressed research question 1 regarding the most impactful journals and articles about the role of language and communication in student adaptation by identifying the most relevant journals and articles. Figure 2 lists the top 20 journals publishing in the field. The five most influential journals in terms of the number of local and global citations are as follows: International Journal of Intercultural Relations (79 and 695 citations, respectively), Journal of Studies in International Education (28 and 343 citations, respectively), Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development (14 and 105 citations, respectively), Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology (13 and 302 citations, respectively), and Higher Education (11 and 114 citations, respectively),

Source: HistCite). Note . TLC, total local citations received; TLC/t, total local citations received per year; TGC, total global citations received; Articles, number of articles published in the field

Top 20 journals publishing on language and communication in student adaptation (

Table 2 lists the 20 most influential and trending articles as measured by, respectively, local citations (TLC) and trending local citations at the end of the period covered (TLCe), that is, mid-2021. The most locally cited article was a qualitative study of Asian students’ experiences in New Zealand by Campbell and Li ( 2008 ) (TLC = 12). That study, which linked host-language proficiency with student satisfaction and effective communication in academic contexts, also received the highest number of global citations per year (TGC/t = 7.86). The most influential article in terms of total local citations per year was a quantitative study by Akhtar and Kröner-Herwig ( 2015 ) (TLC/t = 1.00) who linked students’ host-language proficiency, prior international experience, and age with acculturative stress among students in Germany. Finally, Sam’s ( 2001 ) quantitative study, which found no relationship between host-language and English proficiency and having a local friend on students’ satisfaction with life in Norway, received the most global citations (TGC = 115).

The most trending article (TLCe = 7) was a quantitative study by Duru and Poyrazli ( 2011 ) who considered the role of social connectedness, perceived discrimination, and communication with locals and co-nationals in the sociocultural adaptation of Turkish students in the USA. The second article with the most trending local citations (TLCe = 5) was a qualitative study by Sawir et al. ( 2012 ) who focused on host-language proficiency as a barrier to sociocultural adaptation and communication in the experience of students in Anglophone countries.

Keyword co-occurrence analysis

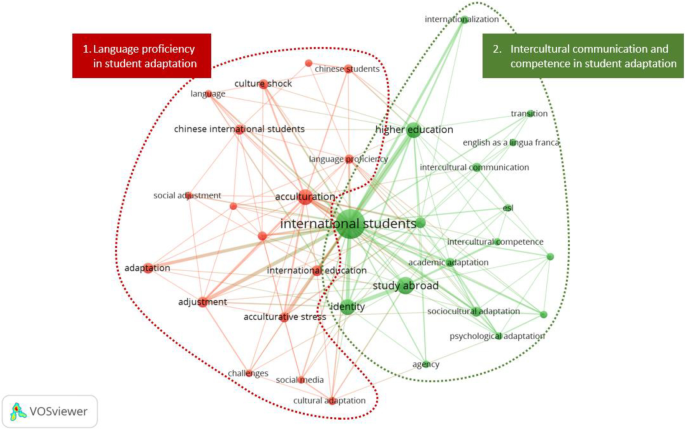

We addressed research question 2 regarding the thematic structure of the research in the field by analyzing the authors’ keyword co-occurrences to establish the thematic structure of the field (Bretas and Alon, 2021 ; Donthu et al., 2020 ). Figure 3 depicts the network of keywords that occurred together in at least five articles between 1994 and 2021. The nodes represent keywords, the edges represent linkages among the keywords, and the proximity of the nodes and the thickness of the edges represent how frequently the keywords co-occurred (Donthu et al., 2020 ). The analysis yielded two even clusters with 17 keywords each. Cluster 1 represents the primary focus on the role of language proficiency in student adaptation. It includes keywords such as “language proficiency,” “adaptation,” “acculturative stress,” “culture shock,” and “challenges.” Cluster 2 represents the focus on the role of intercultural communication and competence in student adaptation. It includes keywords such as “intercultural communication,” “intercultural competence,” “academic/psychological/sociocultural adaptation,” and “transition.”

Source: VOS)

Authors’ keyword co-occurrence analysis (

Conceptual thematic map

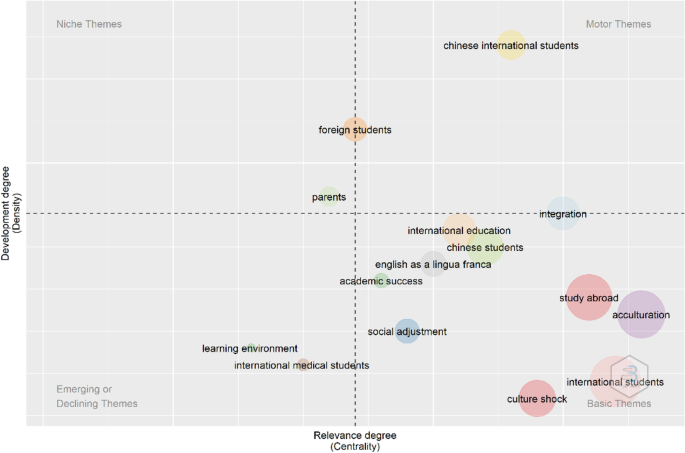

Based on the authors’ keywords, we plotted a conceptual map (see Fig. 4 ) using two dimensions. The first is density , which indicates the degree of development of the themes as measured by the internal associations among the keywords. The second is centrality , which indicates the relevance of the themes as measured by the external associations among the keywords. The map shows four quadrants: (a) motor themes (high density and centrality), (b) basic themes (low density and high centrality), (c) niche themes (high density and low centrality), and (d) emerging/declining themes (low density and centrality) (Bretas & Alon, 2021 ). The analysis revealed that motor themes in the field are studies of Chinese students’ experiences and student integration. Unsurprisingly, the basic themes encompass most topics related to language in student adaptation. Research examining the perspective of the students’ parents with regard to their children’s overseas experience exemplifies a niche theme. Finally, “international medical students” and “learning environment” unfold as emerging/declining themes. To determine if the theme is emerging or declining, we analyzed bibliometric data on articles relating to medical students’ adaptation and students’ learning environment. We found that out of 19 articles on medical students published in 13 journals (10 medicine/public health-related), 15 (79%) articles were published over the last five years (2016–2021), which clearly suggests an emerging trend. The analysis of authors’ keywords yielded only three occurrences of the keyword “learning environment” in articles published in 2012, 2016, and 2020, which may suggest an emerging trend. To further validate this result, we searched for this keyword in titles and abstracts and identified eight relevant articles published between 2016 and 2020, which supports the emerging trend.

Source: Biblioshiny)

Conceptual thematic map (

Citation mapping: research streams

We addressed research question 3 regarding the leading research streams investigating language and communication in student adaptation by using co-citation mapping techniques to reveal how the articles in our dataset are co-cited over time. To produce meaningful results that would not trade depth for breadth in our large dataset (313 articles), we limited the search to articles with TGC ≥ 10 and TLC ≥ 3. These thresholds yielded the 31 articles (10% of the dataset) that are most frequently cited within and outside the dataset, indicating their driving force in the field. We analyzed these 31 articles further because their number corresponds with the suggested range of the most-cited core articles for mapping in HistCite (Garfield et al., 2006 ).

Figure 5 presents the citation mapping of these 31 articles. The vertical axis shows how the articles have been co-cited over time. Each node represents an article, the number in the box represents the location of the article in the entire dataset, and the size of the box indicates the article’s impact in terms of TLCs. The arrows indicate the citing direction between two articles. A closer distance between two nodes/articles indicates their similarity. Ten isolated articles in Fig. 5 have not been co-cited by other articles in the subsample of 31 articles.

Source: HistCite)

Citation mapping of articles on language and communication in student adaptation (

A content analysis of these 31 articles points to two major and quite even streams in the field: (a) “ second-language proficiency ” (16 articles) and (b) “ interactions in the host country ” involving second-language proficiency, communication competence, intercultural communication, and other factors (15 articles). We clustered the articles based on similar conceptualizations of language and communication and their role in student adaptation. As Fig. 5 illustrates, the articles formed distinct but interrelated clusters. The vertical axis indicates that while studies focusing solely on second-language proficiency and host-country interactions have developed relatively concurrently throughout the entire timespan, a particular interest in host-country interactions occurred in the second decade of research within the field (between 2009 and 2013). The ensuing sections present the results of the content analysis of the studies in each research stream, discussing the results in light of the major theories outlined before.

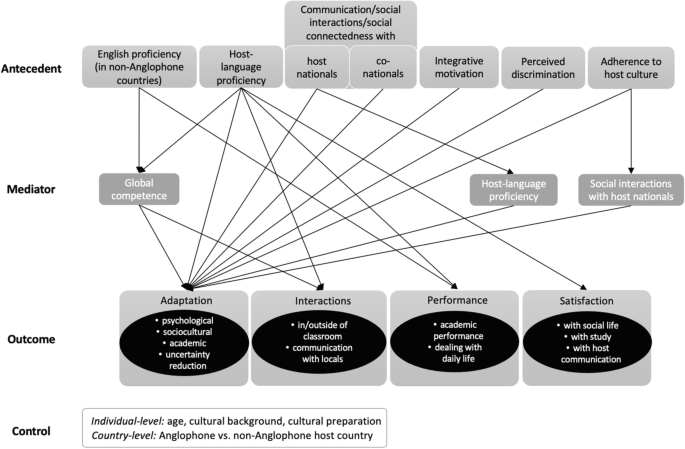

Content analysis

We sought to answer research question 4 regarding the effects of language and communication on student adaptation by synthesizing the literature within the previously established two research streams. The concept map in Fig. 6 illustrates the predictive effects of second-language proficiency and host-country interactions on various adaptation domains. Table 4 in the Appendix presents a detailed description of the synthesis and lists studies reporting these effects, underscoring inconclusive results.

A concept map synthesizing research on language and communication in student adaptation

Second-language proficiency

This research stream focuses on language barriers and the role of foreign-language proficiency in student adaptation. Having host-language proficiency predicts less acculturative stress (Akhtar and Kröner-Herwig, 2015 ), while limited host-language proficiency inhibits communication with locals and academic integration (Cao et al., 2016 ). These results are in line with the acculturation theory (Berry, 1997 , 2005 ; Ward et al., 2001 ) and the communication and cross-cultural adaptation theory (Kim, 2001 ). Cross ( 1995 ) suggested that social skills predict sociocultural rather than psychological (perceived stress, well-being) adaptation (Searle and Ward, 1990 ). Indeed, several qualitative studies have explained that the language barrier affects sociocultural adaptation by preventing students from establishing contacts with host nationals (Wang and Hannes, 2014 ), developing meaningful relationships (Sawir et al., 2012 ), and limiting occasions for cultural learning (Trentman, 2013 ), supporting the acculturation theory (Anderson, 1994 ; Church, 1982 ; Searle and Ward, 1990 ).

Moreover, insufficient host-language proficiency reduces students’ satisfaction by hampering their communication, socialization, and understanding of lectures in academic contexts (Campbell and Li, 2008 ). Similarly, language affects academic adaptation in students who have difficulty communicating with domestic students (Young and Schartner, 2014 ) or when used as a tool in power struggles, limiting students’ opportunities to speak up in class and participate in discussions or decision-making (Shi, 2011 ). Students who have limited host-language proficiency tend to interact with other international students, which exacerbates their separation from domestic students (Sawir et al., 2012 ). These findings again confirm the theories of acculturation (Berry, 1997 ; Ward et al., 2001 ) and communication and cross-cultural adaptation (Kim, 2001 ).

With regard to the acculturation theory (Berry, 1997 ; Ward and Kennedy, 1999 ), we found inconclusive results concerning the impact of foreign-language skills on students’ satisfaction and adaptation. Specifically, some studies (e.g., Sam, 2001 ; Ying and Liese, 1994 ) found this effect to be non-significant when tested in regression models. One explanation for this result might be the indirect effect of language on adaptation. For instance, Yang et al. ( 2006 ) established that host-language proficiency mediated the relationship between contact with host nationals and the psychological and sociocultural adjustment of students in Canada. Swami et al. ( 2010 ) reported that better host-language skills among Asian students in Britain predicted their adaptation partly because they had more contacts with host nationals. In turn, Meng et al. ( 2018 ) found that the relationship between foreign-language proficiency and social and academic adaptation was fully mediated by global competence (understood as “intercultural competence” or “global mindset”) in Chinese students in Belgium.

Interactions in the host country

The second research stream comprises studies taking a broader look at language and communication in student adaptation by considering both individual and social interaction contexts: second-language (host-language and English) proficiency; willingness to communicate in the second language; communication interactions with domestic and international students, host nationals, and co-nationals; social connectedness (i.e., a subjective awareness of being in a close relationship with the social world; Lee and Robbins, 1998 ; and integrative motivation (i.e., a positive affective disposition towards the host community; Yu, 2013 .

Host-language proficiency predicts academic (Hirai et al., 2015 ; Yu, 2013 ), psychological (Hirai et al., 2015 ; Rui and Wang, 2015 ), and sociocultural adaptation (Brown, 2009 ; Duru and Poyrazli, 2011 ), confirming the acculturation theory (Ward et al., 2001 ). However, although some studies (Hirai et al., 2015 ; Yu, 2013 ) confirmed the impact of host-language proficiency on academic adaptation, they found no such impact on sociocultural adaptation. Yu’s ( 2013 ) study reported that sociocultural adaptation depends on academic adaptation rather than on host-language proficiency. Moreover, host-language proficiency increases the students’ knowledge of the host culture, reduces their uncertainty, and promotes intercultural communication (Gallagher, 2013 ; Rui and Wang, 2015 ), supporting the central aspects of the AUM theory (Gudykunst, 2005 ).

In turn, by enabling communication with academics and peers, second-language proficiency promotes academic (Yu and Shen, 2012 ) and sociocultural adaptation, as well as social satisfaction (Perrucci and Hu, 1995 ). It also increases the students’ willingness to communicate in non-academic contexts. This willingness mediates the relationship between second-language proficiency and cross-cultural difficulties among Asian students in England (Gallagher, 2013 ). This finding may explain inconclusive results concerning the relationship between second-language proficiency and cultural adaptation. It appears that second-language proficiency alone is insufficient for successful adaptation. This proficiency should be coupled with the students’ willingness to initiate intercultural communication to cope with communication and cultural difficulties, which is compatible with both the AUM theory and Kim’s ( 2001 ) communication and cross-cultural adaptation theory.

As mentioned before, host-language proficiency facilitates adaptation through social interactions. Research demonstrates that communication with domestic students predicts academic satisfaction (Perrucci and Hu, 1995 ) and academic adaptation (Yu and Shen, 2012 ), confirming Kim’s ( 2001 ) theory. Moreover, the frequency of interaction (Zimmermann, 1995 ) and direct communication with host nationals (Rui and Wang, 2015 ) predict adaptation and reduce uncertainty, supporting the AUM theory. Zhang and Goodson ( 2011 ) found that social interactions with host nationals mediate the relationship between adherence to the host culture and sociocultural adaptation difficulties, confirming the acculturation theory (Berry, 1997 ), the intergroup contact theory (Allport, 1954 ; Pettigrew, 2008 ), and the culture learning approach in acculturation theory (Ward et al., 2001 ).

In line with the intergroup contact theory, social connectedness with host nationals predicts psychological and sociocultural adaptation (e.g., Hirai et al., 2015 ; Zhang and Goodson, 2011 ), confirming the sojourner adjustment framework (Church, 1982 ) and extending the acculturation framework (Ward and Kennedy, 1999 ) that recognizes the relevance of social connectedness for sociocultural adaptation only.

Research on interactions with co-nationals has produced inconclusive results. Some qualitative studies (Pitts, 2009 ) revealed that communication with co-nationals enhances students’ sociocultural adaptation and psychological and functional fitness for interacting with host nationals. Consistent with Kim’s ( 2001 ) theory, such communication may be a source of instrumental and emotional support for students when locals are not interested in contacts with them (Brown, 2009 ). Nonetheless, Pedersen et al. ( 2011 ) found that social interactions with co-nationals may cause psychological adjustment problems (e.g., homesickness), contradicting the acculturation theory (Ward and Kennedy, 1994 ), or increase their uncertainty (Rui and Wang, 2015 ), supporting the AUM theory.

Avenues for future research

We addressed research question 5 regarding future research directions through a content analysis of the 31 most impactful articles in the field. Importantly, all 20 trending articles listed in Table 1 were contained in the set of 31 articles. This outcome confirms the relevance of the results of the content analysis. We used these results as the basis for formulating the research questions we believe should be addressed within each of the two research streams. These questions are listed in Table 3 .

Research has focused primarily on the experience of Asian students in Anglophone countries (16 out of 31 most impactful articles), with Chinese students’ integration being the motor theme. This is not surprising given that Asian students account for 58% of all international students worldwide (OECD, 2021b ). In addition, Anglophone countries have been the top host destinations for the last two decades. The USA, the UK, and Australia hosted 49% of international students in 2000, while the USA, the UK, Canada, and Australia hosted 47% of international students in 2020 (Project Atlas, 2020 ). This fact raises the question of the generalizability of the research results across cultural contexts, especially given the previously identified cultural variation in student adaptation (Fritz et al., 2008 ). Thus, it is important to study the experiences of students in underexplored non-Anglophone host destinations that are currently gaining in popularity, such as China, hosting 9% of international students worldwide in 2019, France, Japan, or Spain (Project Atlas, 2020 ). Furthermore, future research in various non-Anglophone countries could precisely define the role of English as a lingua franca vs. host-language proficiency in international students’ experience.

The inconsistent results concerning the effects of communication with co-nationals on student adaptation (e.g., Pedersen et al., 2011 ; Pitts, 2009 ) indicate that more contextualized research is needed to determine if such communication is a product of or a precursor to adaptation difficulties (Pedersen et al., 2011 ). Given the lack of confirmation of the acculturation theory (Ward and Kennedy, 1994 ) or the communication and cross-cultural adaptation theory (Kim, 2001 ) in this regard, future research could cross-check the formation of students’ social networks with their adaptation trajectories, potentially using other theories such as social network theory to explain the contradictory results of empirical research.

Zhang and Goodson ( 2011 ) showed that social connectedness and social interaction with host nationals predict both psychological and sociocultural adaptation. In contrast, the sojourner adjustment framework (Ward and Kennedy, 1999 ) considered their impact on sociocultural adaptation only. Thus, future research should conceptualize the interrelationships among social interactions in the host country and various adaptation domains (psychological, sociocultural, and academic) more precisely.

Some studies (Brown, 2009 ; Gallagher, 2013 ; Rui and Wang, 2015 ) confirm all of the major adaptation theories in that host-language proficiency increases cultural knowledge and the acquisition of social skills, reduces uncertainty and facilitates intercultural communication. Nevertheless, the impact of language on sociocultural adaptation appears to be a complex issue. Our content analysis indicated that sociocultural adaptation may be impacted by academic adaptation (Yu, 2013 ) or does not occur when students do not engage in meaningful interactions with host nationals (Ortaçtepe, 2013 ). To better capture the positive sociocultural adaptation outcomes, researchers should take into account students’ communication motivations, together with other types of adaptation that may determine sociocultural adaptation.

Next, in view of some research suggesting the mediating role of second-language proficiency (Yang et al., 2006 ), contacts with host nationals (Swami et al., 2010 ), and students’ global competence (Meng et al., 2018 ) in their adaptation, future research should consider other non-language-related factors such as demographic, sociocultural, and personality characteristics in student adaptation models.

Finally, the conceptual map of the field established the experiences of medical students and the learning environment as an emerging research agenda. We expect that future research will focus on the experience of other types of students such as management or tourism students who combine studies with gaining professional experience in their fields. In terms of the learning environment and given the development and growing importance of online learning as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, future research should explore the effects of remote communication, both synchronous and asynchronous, in online learning on students’ adaptation and well-being.

This article offers an objective approach to reviewing the current state of the literature on language and communication in student adaptation by conducting a bibliometric analysis of 313 articles and a content analysis of 31 articles identified as the driving force in the field. Only articles in English were included due to the authors’ inability to read the identified articles in Russian, Spanish, or Chinese. Future research could extend the data search to other languages.

This review found support for the effects of language of communication on student adaptation, confirming major adaptation theories. Nevertheless, it also identified inconsistent results concerning communication with co-nationals and the complex effects of communication with host nationals. Thus, we suggested that future research better captures the adaptation outcomes by conducting contextualized research in various cultural contexts, tracking the formation of students’ social networks, and precisely conceptualizing interrelations among social interactions in the host country and different adaptation domains. Researchers should also consider students’ communication motivations and the mediating role of non-language-related factors in student adaptation models.

Akhtar, M., & Kröner-Herwig, B. (2015). Acculturative stress among international students in context of socio-demographic variables and coping styles. Current Psychology, 34 (4), 803–815. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9303-4

Article Google Scholar

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice . Perseus Books.

Alon, I., Anderson, J., Munim, Z. H., & Ho, A. (2018). A review of the internationalization of Chinese enterprises. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 35 (3), 573–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-018-9597-5

Anderson, L. E. (1994). A new look at an old construct: Cross-cultural adaptation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 18 (3), 293–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(94)90035-3

Andrade, M. S. (2006). International students in English-speaking universities. Journal of Research in International Education, 5 (2), 131–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240906065589

Benzie, H. J. (2010). Graduating as a “native speaker”: International students and English language proficiency in higher education. Higher Education Research and Development, 29 (4), 447–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294361003598824

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 46 (1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x

Berry, J. W. (2005). Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29 (6), 697–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013

Black, J. S. (1990). The relationship of personal characteristics with the adjustment of Japanese expatriate managers. Management International Review, 30 (2), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.2307/40228014

Bretas, V. P. G., & Alon, I. (2021). Franchising research on emerging markets: Bibliometric and content analyses. Journal of Business Research, 133 , 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.067

Brown, L. (2009). Using an ethnographic approach to understand the adjustment journey of international students at a university in England. Advances in Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 3 , 101–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1871-3173(2009)0000003007

Burr, V. (2006). An introduction to social constructionism . Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Campbell, J., & Li, M. (2008). Asian students’ voices: An empirical study of Asian students’ learning experiences at a New Zealand University. Journal of Studies in International Education, 12 (4), 375–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315307299422

Cao, C., Zhu, C., & Meng, Q. (2016). An exploratory study of inter-relationships of acculturative stressors among Chinese students from six European union (EU) countries. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 55 , 8–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2016.08.003

Church, A. T. (1982). Sojourner adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 91 (3), 540–572. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.91.3.540

Cross, S. E. (1995). Self-construals, coping, and stress in cross-cultural adaptation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 26 (6), 673–697. https://doi.org/10.1177/002202219502600610

Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Ranaweera, C., Sigala, M., & Sureka, R. (2020). Journal of Service Theory and Practice at age 30: Past, present and future contributions to service research. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 31 (3), 265–295. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-10-2020-0233

Duru, E., & Poyrazli, S. (2011). Perceived discrimination, social connectedness, and other predictors of adjustment difficulties among Turkish international students. International Journal of Psychology, 46 (6), 446–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2011.585158

Fritz, M. V., Chin, D., & DeMarinis, V. (2008). Stressors, anxiety, acculturation and adjustment among international and North American students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32 (3), 244–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.01.001

Gallagher, H. C. (2013). Willingness to communicate and cross-cultural adaptation: L2 communication and acculturative stress as transaction. Applied Linguistics, 34 (1), 53–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/ams023

Garfield, E., Paris, S. W., & Stock, W. G. (2006). HistCite™ : A software tool for informetric analysis of citation linkage. Information, 57 (8), 391–400.

Google Scholar

Gudykunst, W. B., & Hammer, M. R. (1988). Strangers and hosts—An uncertainty reduction based theory of intercultural adaptation. In Y. Y. Kim & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Cross-cultural adaptation: Current approaches (Vol. 11, pp. 106–139). Sage.

Gudykunst, W. B. (2005). An anxiety/uncertainty management (AUM) theory of strangers’ intercultural adjustment. In W. B. Gudykunst (Ed.), Theorizing about intercultural communication (pp. 419–457). Sage.

Hirai, R., Frazier, P., & Syed, M. (2015). Psychological and sociocultural adjustment of first-year international students: Trajectories and predictors. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62 (3), 438–452. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000085

Hope, J. (2020). Be aware of how COVID-19 could impact international students. The Successful Registrar, 20 (3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/tsr.30708

Hotta, J., & Ting-Toomey, S. (2013). Intercultural adjustment and friendship dialectics in international students: A qualitative study. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37 (5), 550–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.06.007

Jackson, J. (2015). Becoming interculturally competent: Theory to practice in international education. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 48 , 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.03.012

Jing, X., Ghosh, R., Sun, Z., & Liu, Q. (2020). Mapping global research related to international students: A scientometric review. Higher Education, 80 (3), 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10734-019-00489-Y

Khawaja, N. G., & Stallman, H. M. (2011). Understanding the coping strategies of international students: A qualitative approach. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools, 21 (2), 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1375/ajgc.21.2.203

Kim, Y. Y. (2001). Becoming intercultural: An integrative theory of communication and cross-cultural adaptation . Sage.

Kramsch, C. (1998). Language and culture . Oxford University Press.

Lee, R. M., & Robbins, S. B. (1998). The relationship between social connectedness and anxiety, self-esteem, and social identity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 45 (3), 338–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.45.3.338

Marginson, S. (2014). Student self-formation in international education. Student Self-Formation in International Education, 18 (1), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315313513036

Meng, Q., Zhu, C., & Cao, C. (2018). Chinese international students’ social connectedness, social and academic adaptation: The mediating role of global competence. Higher Education, 75 (1), 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0129-x

Neuendorf, K. A. (2002). The content analysis guidebook (2nd ed.). Sage.

OECD (2021a). Education at a Glance 2021: OECD indicators . Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/b35a14e5-en .

OECD (2021b). What is the profile of internationally mobile students? https://doi.org/10.1787/5A49E448-EN

Ortaçtepe, D. (2013). “This is called free-falling theory not culture shock!”: A narrative inquiry on second language socialization. Journal of Language, Identity and Education, 12 (4), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2013.818469

Pedersen, E. R., Neighbors, C., Larimer, M. E., & Lee, C. M. (2011). Measuring sojourner adjustment among American students studying abroad. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35 (6), 881–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.06.003

Perrucci, R., & Hu, H. (1995). Satisfaction with social and educational experiences among international graduate students. Research in Higher Education, 36 (4), 491–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02207908

Pettigrew, T. F. (2008). Future directions for intergroup contact theory and research. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32 (3), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJINTREL.2007.12.002

Piller, I. (2007). Linguistics and Intercultural Communication. Language and Linguistics Compass, 1 (3), 208–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-818X.2007.00012.x

Pitts, M. J. (2009). Identity and the role of expectations, stress, and talk in short-term student sojourner adjustment: An application of the integrative theory of communication and cross-cultural adaptation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33 (6), 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.07.002

Project Atlas . (2020). https://iie.widen.net/s/rfw2c7rrbd/project-atlas-infographics-2020 . Accessed 15 September 2021.

Ruble, R. A., & Zhang, Y. B. (2013). Stereotypes of Chinese international students held by Americans. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37 (2), 202–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2012.12.004

Rui, J. R., & Wang, H. (2015). Social network sites and international students’ cross-cultural adaptation. Computers in Human Behavior, 49 , 400–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.041

Sam, D. L. (2001). Satisfaction with life among international students: An exploratory study. Social Indicators Research, 53 (3), 315–337. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007108614571

Sawir, E., Marginson, S., Forbes-Mewett, H., Nyland, C., & Ramia, G. (2012). International student security and English language proficiency. Journal of Studies in International Education, 16 (5), 434–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315311435418

Searle, W., & Ward, C. (1990). The prediction of psychological and sociocultural adjustment during cross-cultural transitions. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 14 (4), 449–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(90)90030-Z

Shi, X. (2011). Negotiating power and access to second language resources: A study on short-term Chinese MBA students in America. Modern Language Journal, 95 (4), 575–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01245.x

Smith, R. A., & Khawaja, N. G. (2011). A review of the acculturation experiences of international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35 (6), 699–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.08.004

Swami, V., Arteche, A., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2010). Sociocultural adjustment among sojourning Malaysian students in Britain: A replication and path analytic extension. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45 (1), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0042-4

Trentman, E. (2013). Imagined communities and language learning during study abroad: Arabic Learners in Egypt. Foreign Language Annals, 46 (4), 545–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12054

UIS Statistics . (2021). http://data.uis.unesco.org/Index.aspx?queryid=172# . Accessed 10 December 2021.

Volet, S., & Jones, C. (2012). Cultural transitions in higher education: Individual adaptation, transformation and engagement. Advances in Motivation and Achievement, 17 , 241–284. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0749-7423(2012)0000017012

Wang, Q., & Hannes, K. (2014). Academic and socio-cultural adjustment among Asian international students in the Flemish community of Belgium: A photovoice project. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 39 (1), 66–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.09.013

Ward, C., Bochner, S., & Furnham, A. (2001). The psychology of culture shock (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Ward, C., & Kennedy, A. (1993). Where’s the “culture” in cross-cultural transition? Comparative studies of sojourner adjustment. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 24 (2), 221–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022193242006

Ward, C., & Kennedy, A. (1994). Acculturation strategies, psychological adjustment, and sociocultural competence during cross-cultural transitions. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 18 (3), 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(94)90036-1

Ward, C., & Kennedy, A. (1999). The measurement of sociocultural adaptation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 23 (4), 659–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-1767(99)00014-0

Yang, R. P. J., Noels, K. A., & Saumure, K. D. (2006). Multiple routes to cross-cultural adaptation for international students: Mapping the paths between self-construals, English language confidence, and adjustment. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30 (4), 487–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.11.010

Ying, Y., & Liese, L. H. (1994). Initial adjustment of Taiwanese students to the United States: The impact of postarrival variables. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 25 (4), 466–477. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022194254003

Young, T. J., & Schartner, A. (2014). The effects of cross-cultural communication education on international students’ adjustment and adaptation. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 35 (6), 547–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2014.884099

Yu, B. (2013). Asian international students at an Australian university: Mapping the paths between integrative motivation, competence in L2 communication, cross-cultural adaptation and persistence with structural equation modelling. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 34 (7), 727–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.796957

Yu, B., & Shen, H. (2012). Predicting roles of linguistic confidence, integrative motivation and second language proficiency on cross-cultural adaptation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36 (1), 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.12.002

Zhang, J., & Goodson, P. (2011). Acculturation and psychosocial adjustment of Chinese international students: Examining mediation and moderation effects. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35 (5), 614–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.11.004

Zimmermann, S. (1995). Perceptions of intercultural communication competence and international student adaptation to an American campus. Communication Education, 44 (4), 321–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529509379022

Zupic, I., & Čater, T. (2015). Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organizational Research Methods, 18 (3), 429–472. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114562629

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions.

This research is supported by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange grant “Exploring international students’ experiences across European and non-European contexts” [grant number PPN/BEK/2019/1/00448/U/00001] to Michał Wilczewski.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Applied Linguistics, University of Warsaw, Dobra 55, 00-312, Warsaw, Poland

Michał Wilczewski

Department of Economics and Business Administration, University of Ariel, 40700, Ariel, Israel

School of Business and Law, University of Agder, Gimlemoen 25, 4630, Kristiansand, Norway

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Both authors contributed to the study conception and design. Michał Wilczewski had the idea for the article, performed the literature search and data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Ilan Alon critically revised the work, suggested developments and revisions, and edited the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Michał Wilczewski .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Wilczewski, M., Alon, I. Language and communication in international students’ adaptation: a bibliometric and content analysis review. High Educ 85 , 1235–1256 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00888-8

Download citation

Accepted : 14 June 2022

Published : 12 July 2022

Issue Date : June 2023