If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Europe 1300 - 1800

Course: europe 1300 - 1800 > unit 4.

- Michelangelo: Sculptor, Painter, Architect and Poet

- Who was Michelangelo?

- Michelangelo and his early drawings

- Pietà (marble sculpture)

- Michelangelo's David and the Florentine Republic

- Unfinished business—Michelangelo and the Pope

- Moses (marble sculpture)

- Carving marble with traditional tools

- Slaves (marble sculptures)

- Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel

- Studies for the Battle of Cascina and the Creation of Adam

- Studies for the Libyan Sibyl and a small Sketch for a Seated Figure (verso)

- Studies for the Libyan Sibyl (recto); Studies for the Libyan Sibyl and a small Sketch for a Seated Figure (verso)

Last Judgment, Sistine Chapel

- Last Judgment (altar wall, Sistine Chapel)

- Studies for the Last Judgment and a late crucifixion drawing

- Michelangelo, Medici Chapel (New Sacristy)

- Laurentian Library

- Replicating Michelangelo

“He will come to judge the living and the dead”

from the Apostle’s Creed, an early statement of Christian belief

Historical & pictorial contexts

The composition, the elect (those going to heaven), the damned (those going to hell), in the company of christ, critical response: masterpiece or scandal, a self-portrait, an epic painting, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

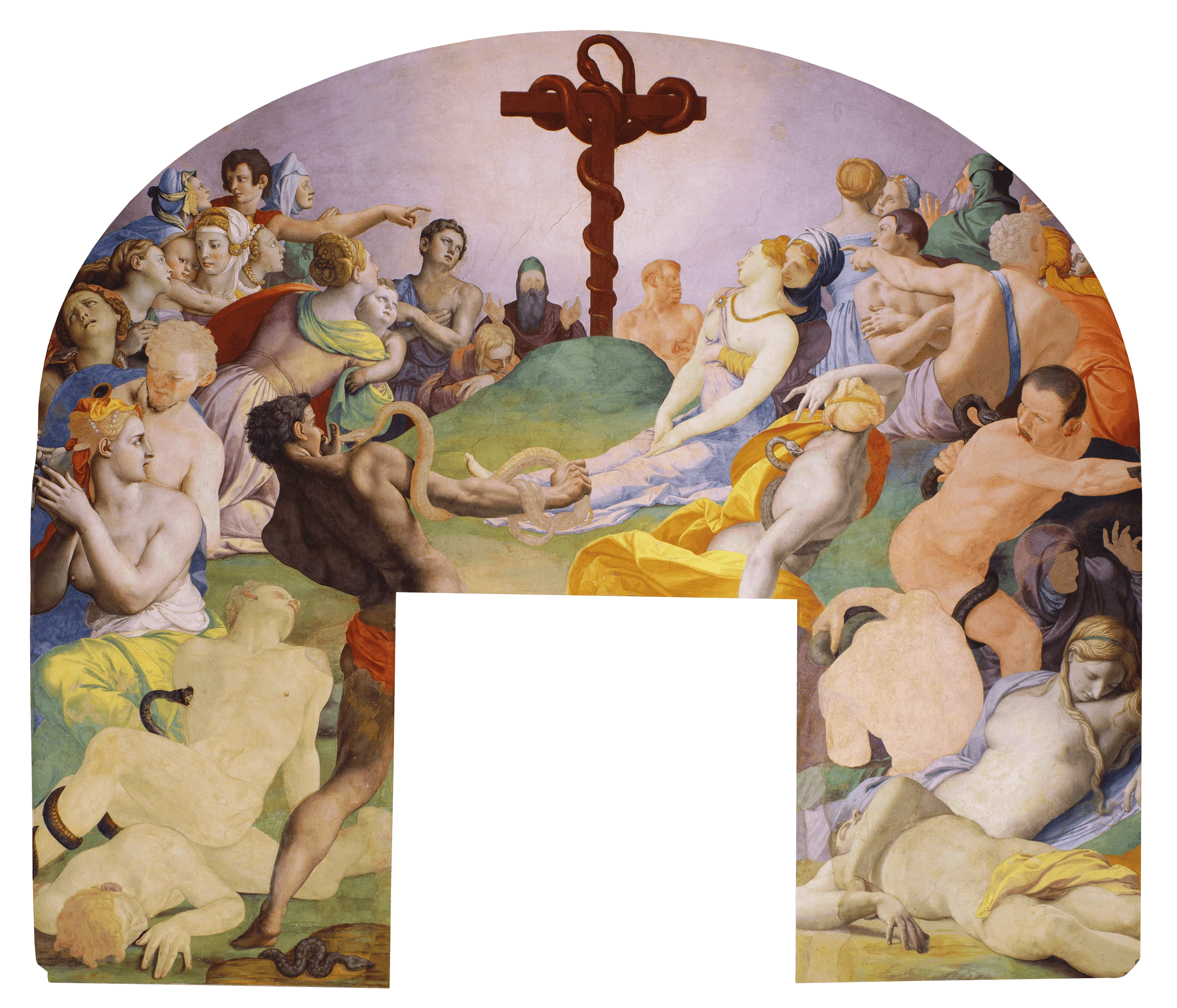

Michelangelo, Last Judgment , Sistine Chapel

Michelangelo, Last Judgment , Sistine Chapel, fresco, 1534–41 (Vatican City, Rome). Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

Video transcript

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:03] More than 20 years after Michelangelo finished painting the frescoes on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, he was asked to do another fresco, this time on the altar wall.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:14] On the altar wall, Michelangelo painted “The Last Judgment.” This is an old subject in art history from the New Testament, from the Book of Revelation.

Dr. Zucker: [0:23] It’s not possible to overestimate how important this location is. This is the high altar of the Sistine Chapel. This is where the pope led mass. This is still the room where the College of Cardinals selects the next pope.

Dr. Harris: [0:35] Michelangelo paints Christ in the top center. On either side of Christ are saints and Old Testament figures, but below Christ we have the separation of the blessed from the damned: on Christ’s left, the damned who are going to hell, and on Christ’s right, the blessed who are going to heaven.

Dr. Zucker: [0:53] There is no more dramatic, no more powerful an image in the Catholic tradition. This is the end of time. We see Christ as a powerful judge who’s facing towards the damned, smiting them.

Dr. Harris: [1:06] He seems to be pointing to the wounds that he received on the cross. Beside him is the Virgin Mary, who crouches, powerless. She seems no longer to be able to intercede for mankind.

Dr. Zucker: [1:17] Although she looks down towards the blessed and seems to give over to Christ the damned.

Dr. Harris: [1:22] On Christ’s right, the blessed rise up to heaven from their graves. They’re pulled by angels who seem to assist them in their ascent to heaven.

Dr. Zucker: [1:32] I love these images because Michelangelo’s bodies are so dense. They’re so powerful. They’re so muscular. Even the spirits that are being resurrected, that they have to be lifted up with great effort. You can see one angel pulling up the blessed by a rosary.

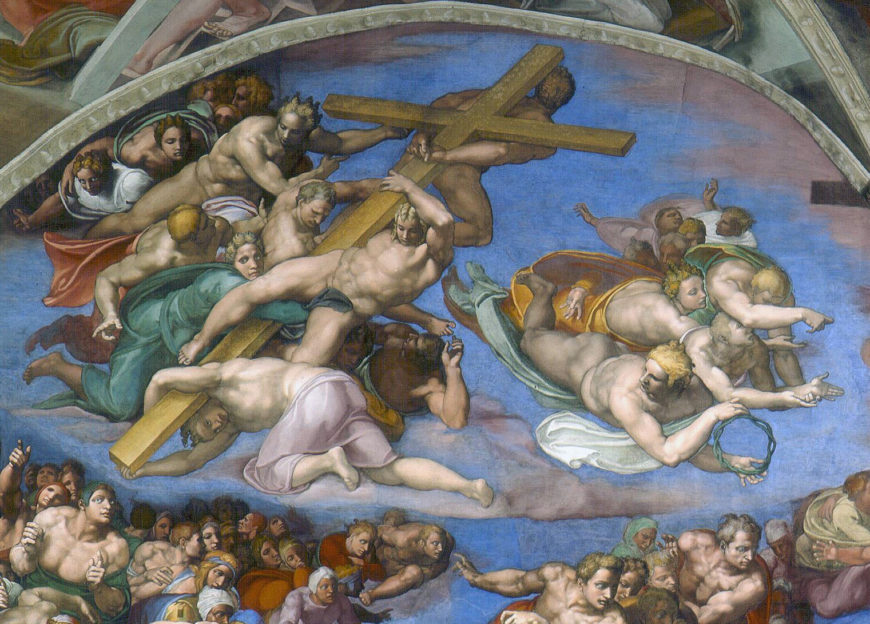

Dr. Harris: [1:46] That’s right, a couple who’s literally being helped to ascend to heaven on the strength of their prayer, represented by the rosary beads. Directly below Christ, we see angels blowing their trumpets, awakening the dead from their graves.

Dr. Zucker: [1:59] Look at those long golden trumpets. This is in the Book of Revelation. It is made explicit here.

Dr. Harris: [2:04] But those angels don’t look very much like what we expect of angels. They are clearly male and powerful. Their heads are too small for their bodies. In blowing the trumpets, they look almost as though they’re going to explode with the power that that takes.

Dr. Zucker: [2:21] Well, they have to wake the dead, and that’s exactly what they’re doing. We can see crypts opening up. We can see graves. We can see these spirits that seem to emerge from the earth. It’s so unexpected, the physicality that Michelangelo has rendered the spirits [with].

[2:35] You would think that they would be incorporeal — they would have no mass, they would have no gravity, they would have no weight. But the opposite is true here. We feel the struggle, the difficulty of saving those souls, of bringing those souls into heaven.

Dr. Harris: [2:47] There’s no shying away from the body here. It is typical of Michelangelo that there’s this interest in the physicality of the body, the musculature of the body.

Dr. Zucker: [2:57] We see the emphasis on the body even more so perhaps on the right side, with the damned.

Dr. Harris: [3:02] Where on one side we see the blessed rising up toward heaven, on the opposite side we see the fires of hell and the damned being delivered there.

Dr. Zucker: [3:13] They’re being delivered on a boat. You can see the oarsman. This would be Charon, swinging his great oar to kick them off, and the demons are helping with their pitchforks and they’re actually harvesting the new souls for hell. It’s a pretty nasty scene.

Dr. Harris: [3:27] There are demons everywhere, pulling the figures off the boat and into hell.

Dr. Zucker: [3:31] It’s not just the demons that are doing their part. It’s also the angels. Just above this scene, we can see the damned who are being pushed down into hell. They seem to be striving desperately to get out, and they’re being punched by angels who are above them.

[3:45] Probably most arresting of all is the representation of a single figure. He’s got a devil that’s pulling at him from below, but it’s his psychological intensity that has given him the name the “Damned Man.”

Dr. Harris: [3:57] He seems to have just realized that he’s going to spend eternity in hell. There are demons also wrapped around his legs, pulling him down toward hell.

Dr. Zucker: [4:06] Look at his face. The hand is covering one eye as if he can’t believe, he can’t bear to see his fate. On the other hand, his other eye is open wide as if this is the moment of recognition.

Dr. Harris: [4:15] When we look at this scene here in the Sistine Chapel, we can look at Michelangelo’s early work on the ceiling right above us, where we see figures with bodies that are elegant and noble and have a sense of dignity.

[4:28] Here on the altar wall, in the scene of the Last Judgment, the figures look intentionally ugly, intentionally awkward. Their proportions are all wrong. Their heads are too small for their bodies. Their muscles look overdrawn.

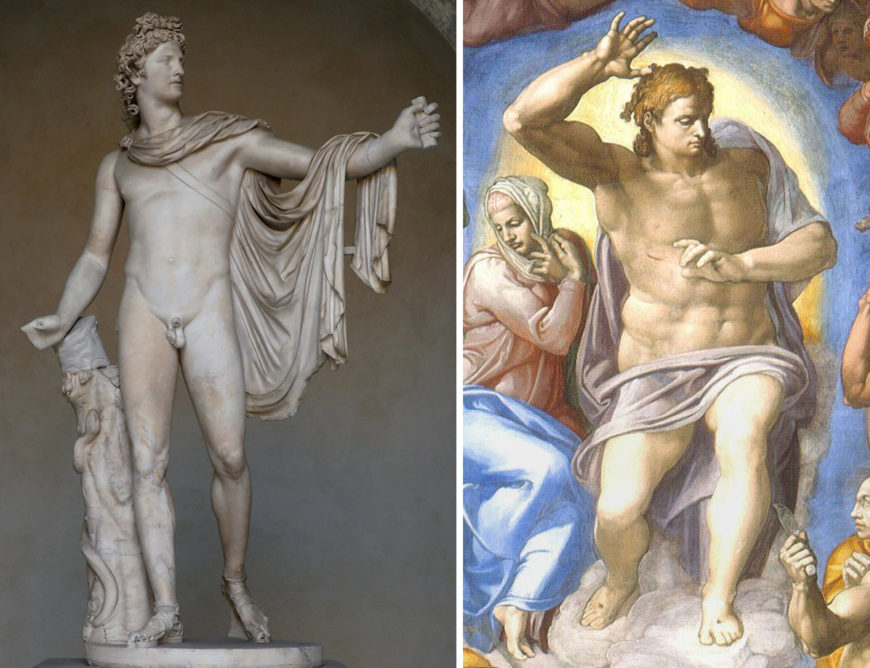

Dr. Zucker: [4:42] That’s especially true of the representation of Christ. Look at the size of that torso. It’s completely out of scale, with his head and with his height. Michelangelo is looking at the human body not in the way that one might have in the High Renaissance, that is, as a reference back to the classical tradition and a kind of ideal proportion.

[5:01] Instead, he’s looking at the body as full of symbolic value. He’s willing to distort the body for the power of the painting itself.

Dr. Harris: [5:09] Right, the religious message is key here and the body is in the service of that message. In the intervening years, the Church has been challenged by Martin Luther and the beginnings of the Protestant Reformation.

Dr. Zucker: [5:23] This was a moment of great turmoil, and as Michelangelo gets older his earlier optimism seems to have been replaced by a deep pessimism.

Dr. Harris: [5:32] That might be best seen in the figure of Saint Catherine, who holds a wheel — which is her attribute, since she was martyred on a wheel — but here, she looks so ungainly. If we compare her to the beauty of Eve on the ceiling, the difference in the way Michelangelo is treating the body is clear.

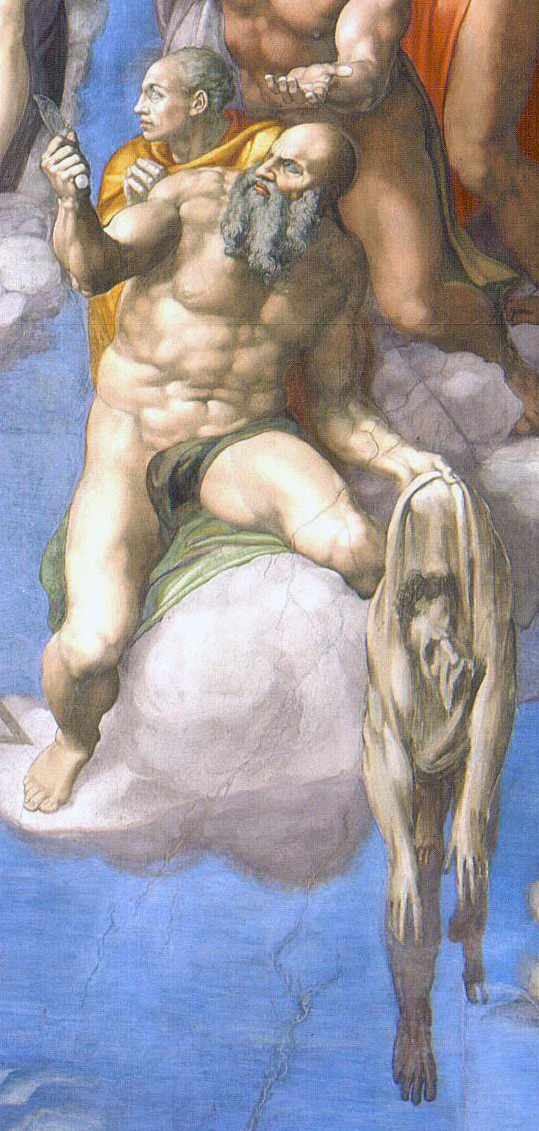

Dr. Zucker: [5:48] Another figure that represents the profound pessimism of this fresco can be seen just to the right and below Christ. We see there a very large figure on a cloud, nude, who is looking up at Christ, holding a knife in one hand and a skin in the other. This is Saint Bartholomew, who was martyred by having his skin removed while he was alive.

Dr. Harris: [6:09] Saints are always identified by their attributes, often by the instrument of their martyrdom. Here, it makes sense that Bartholomew holds a knife.

Dr. Zucker: [6:18] But art historians noticed one curious decision by Michelangelo in the representation of Bartholomew. The face that we see in the skin is actually a self-portrait by the artist.

Dr. Harris: [6:29] So that means we must ask the question, why would Michelangelo put his own face, his own likeness, on the skin of Saint Bartholomew? Here in the middle between Christ, the savior, and the Damned Man?

Dr. Zucker: [6:44] Worse than that, Bartholomew seems to be holding the skin ever so lightly, as if his fingers might open and he might simply let it fall into the boat of Charon on its way to hell.

Dr. Harris: [6:54] This seems to express Michelangelo’s concern for the fate of his own soul, something that we also see in his poetry from this period.

[7:02] In fact, we can draw a diagonal line from the upper left, from the cross in the lunette, through the crown of thorns, through Christ, through the skin of Saint Bartholomew, the Damned Man, and then down to the fires of hell.

[7:17] [music]

Michelangelo, Last Judgment , Sistine Chapel, altar wall, fresco, 1534–41 (Vatican City, Rome) (photo: Francisco Anzola , CC BY 2.0)

He will come to judge the living and the dead from the Apostle’s Creed, an early statement of Christian belief

This is it. The moment all Christians await with both hope and dread. This is the end of time, the beginning of eternity when the mortal becomes immortal, when the elect join Christ in his heavenly kingdom and the damned are cast into the unending torments of hell. What a daunting task: to visualize the endgame of earthly existence—and furthermore, to do so in the Sistine Chapel, the private chapel of the papal court, where the leaders of the Church gathered to celebrate feast day liturgies, where the pope’s body was laid in state before his funeral, and where—to this day—the College of Cardinals meets to elect the next pope.

Historical & pictorial contexts

Titian, Portrait of Pope Paul III , c. 1543, oil on canvas, 113.3 x 88.8 cm (Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples)

The Last Judgment was one of the first art works Paul III commissioned upon his election to the papacy in 1534. The church he inherited was in crisis; the Sack of Rome (1527) was still a recent memory. Paul sought to address not only the many abuses that had sparked the Protestant Reformation , but also to affirm the legitimacy of the Catholic Church and the orthodoxy of its doctrines (including the institution of the papacy). The visual arts would play a key role in his agenda, beginning with the message he directed to his inner circle by commissioning the Last Judgment.

The decorative program of the Sistine Chapel encapsulates the history of salvation. It begins with God’s creation of the world and his covenant with the people of Israel (represented in the Old Testament scenes on the ceiling and south wall), and continues with the earthly life of Christ (on the north wall). The addition of the Last Judgment completed the narrative. The papal court, representatives of the earthly church, participated in this narrative; it filled the gap between Christ’s life and his Second Coming .

The composition

Michelangelo’s Last Judgment is among the most powerful renditions of this moment in the history of Christian art. Over 300 muscular figures, in an infinite variety of dynamic poses, fill the wall to its edges. Unlike the scenes on the walls and the ceiling, the Last Judgment is not bound by a painted border. It is all encompassing and expands beyond the viewer’s field of vision. Unlike other sacred narratives, which portray events of the past, this one implicates the viewer. It has yet to happen and when it does, the viewer will be among those whose fate is determined.

Michelangelo, Last Judgment , Sistine Chapel, altar wall, fresco, 1534–41 (Vatican City, Rome; photo: Alonso de Mendoza )

Despite the density of figures, the composition is clearly organized into tiers and quadrants, with subgroups and meaningful pairings that facilitate the fresco’s legibility. As a whole, it rises on the left and descends on the right, recalling the scales used for the weighing of souls in many depictions of the Last Judgment.

Christ, Mary, and Saints (detail), Michelangelo, Last Judgment , Sistine Chapel, altar wall, fresco, 1534–41 (Vatican City, Rome; photo: Alonso de Mendoza )

Angels (detail), Michelangelo, Last Judgment , Sistine Chapel, altar wall, fresco, 1534–41 (Vatican City, Rome; photo: Alonso de Mendoza )

Christ is the fulcrum of this complex composition. A powerful, muscular figure, he steps forward in a twisting gesture that sets in motion the final sorting of souls (the damned on his left, and the blessed on his right). Nestled under his raised arm is the Virgin Mary. Michelangelo changed her pose from one of open-armed pleading on humanity’s behalf seen in a preparatory drawing , to one of acquiescence to Christ’s judgment. The time for intercession is over. Judgment has been passed.

Directly below Christ a group of wingless angels (left), their cheeks puffed with effort, sound the trumpets that call the dead to rise, while two others hold open the books recording the deeds of the resurrected. The angel with the book of the damned emphatically angles its down to show the damned that their fate is justly based on their misdeeds.

The dead rise from their graves and float to heaven, some assisted by angels. In the upper right, a couple is pulled to heaven on rosary beads, and just below that a risen body is caught in violent tug of war (detail), Michelangelo, Last Judgment , Sistine Chapel, altar wall, fresco, 1534–41 (Vatican City, Rome; photo: Alonso de Mendoza )

The elect (those going to heaven)

Demons drag the damned to hell, while angels beat down those who struggle to escape their fate (detail), Michelangelo, Last Judgment , Sistine Chapel, altar wall, fresco, 1534–41 (Vatican City, Rome; photo: Alonso de Mendoza )

The damned (those going to hell)

Charon drives the damned onto hell’s shores and in the lower right corner stands the ass-eared Minos (detail), Michelangelo, Last Judgment , Sistine Chapel, altar wall, fresco, 1534–41 (Vatican City, Rome; photo: Alonso de Mendoza )

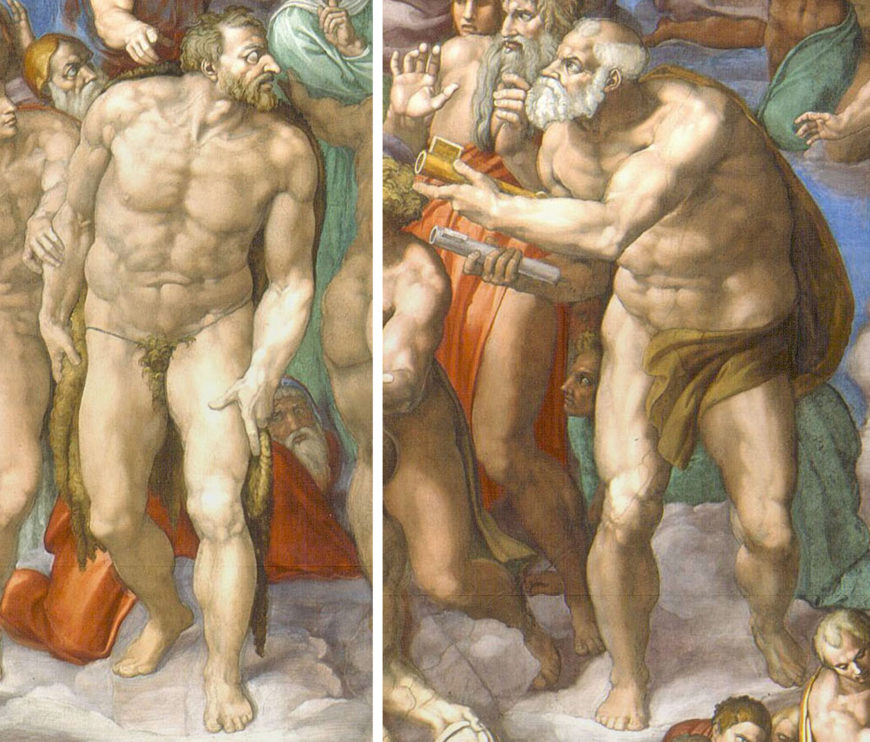

Left: St. John the Baptist; right: St. Peter (detail), Michelangelo, Last Judgment , altar wall, Sistine Chapel, fresco, 1534–41 (Vatican City, Rome; photo: Tetraktys )

In the company of Christ

While such details were meant to provoke terror in the viewer, Michelangelo’s painting is primarily about the triumph of Christ. The realm of heaven dominates. The elect encircle Christ; they loom large in the foreground and extend far into the depth of the painting, dissolving the boundary of the picture plane. Some hold the instruments of their martyrdom: Andrew the X-shaped cross, Lawrence the gridiron, St. Sebastian a bundle of arrows, to name only a few.

Especially prominent are St. John Baptist and St. Peter who flank Christ to the left and right and share his massive proportions (above). John, the last prophet, is identifiable by the camel pelt that covers his groin and dangles behind his legs; and, Peter, the first pope, is identified by the keys he returns to Christ. His role as the keeper of the keys to the kingdom of heaven has ended. This gesture was a vivid reminder to the pope that his reign as Christ’s vicar was temporary—in the end, he too will to answer to Christ.

In the lunettes (semi-circular spaces) at the top right and left, angels display the instruments of Christ’s Passion , thus connecting this triumphal moment to Christ’s sacrificial death. This portion of the wall projects one foot forward, making it visible to the priest at the altar below as he commemorates Christ’s sacrifice in the liturgy of the Eucharist.

Lunette with angels carrying the instruments of the Passion of Christ, (detail), Michelangelo, Last Judgment , Sistine Chapel, fresco, 1534–41 (Vatican City, Rome; photo: Alonso de Mendoza )

Critical response: masterpiece or scandal?

Shortly after its unveiling in 1541, the Roman agent of Cardinal Gonzaga of Mantua reported: “The work is of such beauty that your excellency can imagine that there is no lack of those who condemn it. . . . [T]o my mind it is a work unlike any other to be seen anywhere.” Many praised the work as a masterpiece. They saw Michelangelo’s distinct figural style, with its complex poses, extreme foreshortening, and powerful (some might say excessive) musculature, as worthy of both the subject matter and the location. The sheer physicality of these muscular nudes affirmed the Catholic doctrine of bodily resurrection (that on the day of judgment, the dead would rise in their bodies, not as incorporeal souls).

Left: Apollo Belvedere (Roman copy of a Greek(?) original), original late 4th century B.C.E. marble, 2.3 m high (Vatican Museums, Rome; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Christ (detail), Michelangelo, Last Judgment , Sistine Chapel, fresco, 1534–41 (Vatican City, Rome; photo: Tetraktys )

A self-portrait

St. Bartholomew (detail), Michelangelo, Last Judgment , Sistine Chapel, fresco, 1534–41 (Vatican City, Rome; photo: Alonso de Mendoza )

Even more poignant is Michelangelo’s insertion of himself into the fresco. His is the face on the flayed skin held by St. Bartholomew, an empty shell that hangs precariously between heaven and hell. To his learned audience, the flayed skin would bring to mind not only the circumstances of the saint’s martyrdom but also the flaying of Marsyas by Apollo. In his foolish arrogance, Marsyas challenged Apollo to a musical contest, believing his skill could surpass that of the god of music himself. His punishment for such hubris was to be flayed alive. That Michelangelo should identify with Marsyas is not surprising. His contemporaries had dubbed him the “divine” Michelangelo for his ability to rival God himself in giving form to the ideal body. Often he lamented his youthful pride, which had led him to focus on the beauty of art rather than the salvation of his soul. So, here, in a work done in his mid sixties, he acknowledges his sin and expresses his hope that Christ, unlike Apollo, will have mercy upon him and welcome him into the company of the elect.

An epic painting

Like Dante in his great epic poem, The Divine Comedy , Michelangelo sought to create an epic painting, worthy of the grandeur of the moment. He used metaphor and allusion to ornament his subject. His educated audience would delight in his visual and literary references.

Clockwise: Saint Blaise, Saint Catherine and Saint Sebastian (detail), Michelangelo, Last Judgment , Sistine Chapel, fresco, 1534–41 (Vatican City, Rome; photo: Alonso de Mendoza )

Bibliography

The Last Judgment from the Vatican Museums

Michelangelo’s Last Judgment—uncensored

Bernardine Barnes, Michelangelo’s Last Judgment: The Renaissance Response (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998).

Marcia Hall, ed., Michelangelo’s Last Judgment (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Loren Partridge, Michelangelo The Last Judgment: A Glorious Restoration (New York: Abrams, 1997).

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

The Last Judgment

The Last Judgment is an Italian Renaissance Fresco Painting created by Michelangelo from 1536 to 1541 . It lives at the Vatican Museums in Italy . The image is in the Public Domain , and tagged God , Angels , Saints and Apocalypse . Download See The Last Judgment in the Kaleidoscope

What is The Last Judgment about?

“Then Christ will come “in his glory, and all the angels with him... Before him will be gathered all the nations, and he will separate them one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats, and he will place the sheep at his right hand, but the goats at the left... And they will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life.” — Catechism of the Catholic Church (Mt 25:31,32,46).

The Last Judgment depicts the day when everyone gets what’s coming to them. Final judgment is a popular theme in many religions, and each puts its own spin on it. The Zoroastrians called it Frashokereti , a kind of renovation of our corrupted universe. In Islam it’s yawm al-qiyāmah , where archangel Israfil blows a trumpet, killing all of humanity, then blows it again to resurrect every person to have ever lived for simultaneous judgment. This universal resurrection for judgment was also the doctrine of the Catholic church in Michelangelo’s day, and has changed little in the five hundred years since. In the Catholic visual tradition, the last judgment was a common trope with artists spanning centuries tackling the apocalyptic scene described in Revelation 20:11-15:

“And I saw a great white throne and the one sitting on it. The earth and sky fled from his presence, but they found no place to hide. I saw the dead, both great and small, standing before God’s throne. And the books were opened, including the Book of Life. And the dead were judged according to what they had done, as recorded in the books. The sea gave up its dead, and death and the grave gave up their dead. And all were judged according to their deeds. Then death and the grave were thrown into the lake of fire. This lake of fire is the second death. And anyone whose name was not found recorded in the Book of Life was thrown into the lake of fire.”

Who was The Last Judgment for?

The last judgment was commissioned by Pope Paul III, part of a flailing attempt to pull the Catholic Church out of a burgeoning crisis. Rome had been sacked and the Protestant Reformation kicked off by Martin Luther and his bunch of radicals was getting super popular. Paul III was a new Pope, too. Elected in 1534, one of his first moves was to hire the greatest living artist to continue the brilliant work he'd emblazoned on the ceiling of the Sistine chapel nearly twenty years before. But Paul wasn't buying any old masterpiece, he commissioned a scene of devastating awe. The final act—when Christ himself descends in glory to levy final judgment on mankind, separating the wheat from the chaff.

And remember, while the Sistine chapel sees thousands of tourists through its doors each week, in the sixteenth century it was a private sanctum, the altar room was where the Pope led mass for a select group of religious elites, and new popes were elected by the College of Cardinals. I doubt Paul III was concerned for the salvation of his inner circle, but the imagery reinforced the seriousness of their task in shepherding the world towards God, and illustrated their wet dream of divine judgment against the Protestant upstarts.

The Self-portrait

Yikes. While artists often painted themselves into their artworks, rendering some second-rate disciple in the background as a self-portrait , Michelangelo’s hidden selfie is a grim one. See the shockingly toned old man below and to the right of the radiant Christ in the center of the composition? That’s not Michelangelo—the buff guy holds a drooping, empty skin-suit in his left hand, recently removed from the flayed body of St. Bartholomew—that’s Michelangelo.

Wow. So, why? Most speculation into Michelangelo’s gristly self-portrait is surprisingly dull. The historian and iconology expert Edgar Wind thought it was a reference to a kind of Neoplatonic resurrection, “a prayer for redemption, that through the ugliness the outward man might be thrown off, and the inward man resurrected pure.” Ok, makes sense. Bernadine Barnes, a professor of Renaissance art history who literally wrote the book on Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, cites a more contemporary view that Michelangelo was worried for his soul, since his windblown exterior dangles over the flames of hell. My own thought is, as usual, decidedly less ecumenical. Michelangelo was an opinionated dude, often speaking his mind through his brush. During the long creation of The Last Judgment, the Papal Master of Ceremonies was scandalized by Michelangelo’s many nude forms, and campaigned for them to be censored. In stone-cold revenge, the artist painted the prudish official as a judge presiding over demons, replete with donkey’s ears and a large snake biting him on the penis. All to say that subtlety was optional for Michelangelo. I suspect that after four years of work, burocratic delay, a frustrating patron, and impatient, nosey critics, Michelangelo felt hollowed out by the project, exhausted, empty, and longing for his preferred artistic format—three dimensional sculpture.

Criticism and Controversy

On its completion in 1541 the Last Judgment triggered a tsunami of criticism and debate. Even before the Council of Trent’s moratorium on nudity (spoilers!) Michaelango was pushing the limits of what society and the church was willing to accept and I suspect intentionally antagonizing some of the more conservative players in the Vatican.

The nudity was a huge issue. Even before the work was finished, the papal master of ceremonies Biagio da Cesena stopped by with Pope Paul III and complained “it was most disgraceful that in so sacred a place there should have been depicted all those nude figures, exposing themselves so shamefully, and that it was no work for a papal chapel but rather for the public baths and taverns.” If this was the first complaint directed to Paul III it certainly wasn't the last.

A lot of traditional religious iconography the church had taken for granted for centuries, Michelangelo just skipped. He painted the angels without wings, Christ’s throne—a fixture of previous judgment day depictions—is nowhere to be found, and Christ himself is beardless! One spectacularly pedantic critic cited Revelations 7:1, “After this I saw four angels standing at the four corners of the earth, holding back its four winds so that no wind would blow on land or sea or on any tree” and pointed out garments that look to be flapping in a stiff breeze. Sacrilege!

Pissing off hidebound clergy is delightful, but some of the more nuanced criticisms still resonate. One concern was the legibility of the artwork for lay people. If everyone’s naked, and the angel’s don't have wings, and Jesus doesn't have a beard, how do we know who anyone is? Renaissance art was becoming seen as overworked, self-referential, and Michaelango’s absurdly maximalist flesh party played right into it. A most comprehensive examination of the Last Judgment was published the year of the artist’s death, by the cleric Giovanni Andrea Gilio. Gilio’s Dialogue on the Errors and Abuses of Painters was a good deal more even handed than the title suggests, describing the complexities an artist faces when trying to balance the truth (vero) , the truth-like (finto) , and the fabulous (favoloso) —elements that are all necessary, but when used out of proportion distract from the intended message of the work.

The Censorship

For centuries the artists of the Italian Renaissance looked back to the Greek and Roman obsession with the perfect human body, and painted an absolutely heroic number of nudes in the middle of a stridently Catholic society. But in 1563, the party was over. A massive Catholic council was called to order in response to the growing Protestant Reformation. It was called the Council of Trent, and it was a thorough and conservative house-cleaning of the Catholic Church. Among decrees on the ‘excellence of the celibate state’ and affirmations of transubstantiated sacraments was this prudish little gem: “figures shall not be painted or adorned with a beauty exciting to lust, ... there be nothing seen that is disorderly, or that is unbecomingly or confusedly arranged, nothing that is profane, nothing indecorous, seeing that holiness becometh the house of God.” What a bummer.

With The Last Judgment’s history of controversy and prominent location in the Vatican itself, it became a central battleground in the call to ‘reform art.’ We, the viewers of this work centuries later, got unimaginably lucky. In 1565, a year after Michelangelo’s death, the papacy hired the Mannerist painter Daniele da Volterra to “fix” The Last Judgment. But Volterra had worked in the old master’s circle, and the two got along so well that Michelangelo helped Volterra sketch out his commissions, and pulled strings to get the young artist employed within the Vatican. So Volterra, bless his heart, did his best to keep his changes to a minimum. Adding a robe here, a fold of cloth there to cover the bold bodies from their fragile audience. The only truly massive change Volterra was forced to commit was a scraping and repainting of Saint Catherine and Saint Blaise, who in the original image were positioned such that very little imagination was required to suppose the two actively engaged in intercourse. Volterra, the reluctant revisionist, was quickly dubbed Il Braghettone, the breeches-maker, and in the end wasn't even able to finish his modifications when the pope-of-the-moment Pius IV died. In the years that followed, the Mannerist upstart El Greco offered to replace the entire wall with something “modest and decent, and no less well painted than the other,” and while his offer was refused eventually more than 40 figures were fig-leafed or haphazardly clothed.

The Experience

I visited The Last Judgment. Fifteen years ago I was stumbling around the Vatican, more interested in flirting with fellow students than the incalculable density of history, power, religion and art that surrounded me. The Last Judgment snuck up on me. What I hadn't realized from my dog-eared copy of Janson’s History of Art was that this artwork is not flat. It’s convex, painted into a curved wall and up into two partial domes. It surrounds you, more massive than a billboard and infinitely more personal. The characters vary in size but they acknowledge human scale, they acknowledge you. Bodies rise, saints elevated to paradise and the twisting wicked fall toward the flames. Far above but rendered in bold outline a hot, beardless Jesus raises his hand like a superhero about to let fly an earth-shattering blow, you, little you, are right in his firing line.

And there are too many people in this painting. The absolute compositional excess I suspect to be a clever and intentional device to overwhelm the viewer. Are you familiar with Dunbar’s number? It’s the theoretical limit to how many people at a time you can maintain a relationship with, and the general consensus is that it’s about 150 people. The Last Judgment features 300 figures. 300 saints, martyrs, angels, and demons with twisty little horns grappling the screaming damned. There’s a skeleton wearing the helmet of a Spanish knight. An angel blows his trumpet so hard his immortal eyes have rolled back into his head. And Charon’s there! Ported over from Greek mythology to ferry wicked souls and he looks like he’s ready to whup some ass.

The Last Judgment is what Richard Wagner later termed a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art. The composer had a more formal definition in mind, art synthesizing visual media, stagecraft, costuming and music—but Michelangelo accomplishes totality in one medium, using scale to absorb the viewer, remove them from their life and its many concerns, and drop them into humanity’s last moment—the eschaton. It’s a nightmare, it’s beautiful, it’s horrifying. It doesn't feel good or uplifting, it feels inevitable.

As a bored, horny, distracted student in 2007, it was like putting on a VR headset for the first time. A second before I was annoyed by the Vatican guards shout-whispering “shush!” at the press of gawping turistas, mouths slung open to look at the famous ceiling overhead, and suddenly my world was stolen out from under me. Hello, welcome to the End of days. I fled. I wasn't ready. It was too much. I pushed my way between khaki shorts and polo shirts and heavy DSLR cameras full of images no one would ever look at and left the chapel. I suspect that’s precisely what Michelangelo intended.

Reed Enger, "The Last Judgment," in Obelisk Art History , Published May 17, 2020; last modified November 08, 2022, http://www.arthistoryproject.com/artists/michelangelo/the-last-judgment/.

Assumption of the Virgin

Portrait of a Lady

Christ disputing in the Temple

The Adoration of the Bronze Snake

Jupiter, Neptune and Pluto

La Parisienne

Temptations of St Jerome

By continuing to browse Obelisk you agree to our Cookie Policy

“The Last Judgement” by Michael Angelo Research Paper

Introduction, context of work, historical background, content of work, formal elements. principles of work, works cited.

The Last Judgement by Michael Angelo is the masterpiece that strikes people with its beauty and deep philosophical approach towards the theme. The painting conveys the act of the second come of Christ, and the apocalypse. It is a fresco that is situated in the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City. It is known that it took Michael Angelo four years to complete his work of art somewhere between 1537 and 1541. It has to be said that the entire work is so massive that it covers the back wall of altar of Sistine Chapel. The plot of the painting is that Christ is judging the dead, who in their turn rise from the tombs, recall their fates and now have to answer before the son of God for every deed they carried out. The ones who help Christ are the people of exceptional holiness – the saints. The painting itself is the world’s masterpiece reflecting the times and culture it was painted in (Fiero, p. 4). This paper will disclose the intrinsic and extrinsic meanings of The Last Judgement and their relation.

The work itself is a wonderful reflection of all the religious issues that took place in Europe those times. However, not all the issues are presented in the painting. Namely, those were the times of utmost disagreeing of people with the church’s order. When Pope Julius ordered to rebuild St.Peter’s Cathedral more fees had to be taken for funerals, marriages, and baptism. People did not like it. Moreover, those were the times of permitted sale of indulgence, which is not described within the painting. However, there are those issues in the work that prevailed within the society: the church’s attempts to make changes, and using of information from the Bible. The painting suggests that Jesus is coming in order to set apart the evil and the good. Therefore, the context of The Last Judgement is all about the importance of following the faith.

It is important to mention that the Pope Clement VII was studying the work of Copernicus concerning heliocentric system. This is believed to change the work’s perception by Michelangelo due to Pope’s instructions. The Last Judgement does not convey common description of heaven: the horizontal lines that distinguish earth, heaven, and hell. It is explicitly seen the way Christ is depicted – in the light, in the middle of the painting; just the way all planets spin around the Sun. This proves the fact the painting may be an explanation of the new cosmology.

The Last Judgement forced Cardibal Carafa and Michelangelo to resort to heavy debates due to naked bodies depicted in the painting, which was unacceptable according to the set of society morality. Namely, the obscenity was regarded in the genitals painted right inside the most essential temple of Christianity. Moreover, in regard to the outrageous painting the ‘Fig-Leaf Campaign’ was designed by Carafa and Monsignor Sernini in order to put the work through censorship and with an utmost desire to get rid of fresco. Moreover, within these debates there occurred another controversial situation when pontiff had to extricate himself from a difficult situation because the example of Minos painting was put forward in comparison to Michelangelo’s nude figures. So, he said that in was not his jurisdiction to handle hell’s depiction (Barnes, p. 76).

However, the fresco was restored in 1993, hence unbelievable discoveries were made. Once the half of fig-leaves were removed, it appeared that the character directly below and to the right of St. Bartholomew was a female, though for centuries she considered to be a man.

It is remarkable that the theme chosen by Michelangelo for his work is not the last judgment as traditionally, but its beginning. The content of the painting is interesting due to the beardless Christ and wingless angels; also it is unusual to see the theme of passion of Christ within the last judgment topic. However, still the basic elements of the iconography are well observed. The work is divided in two main perspectives: the sky with Christ and his mother and the earth – with the scenes of arising dead and their further division in righteous and sinner men. The angels trumpet about the beginning of the last judgment, in the right lower corner is St. Lawrence with the grid on which he was burnt later, the dead people are opening their eyes with horror and fear and appear before Christ. The artist skillfully depicts various sinners who, according to their sins, arise easily or slowly. (Angelo, n.p.)

The work is remarkable for its close tonal line and the restrained palette. However, this does not make The Last Judgement less breath taking. The lines and colors determine the power and energy which is, of course, evidently apparent to all the viewers and admirers. It is remarkable that the painting presents one of the first works exposing the three-dimensionality of the forms. The bodies are luminous, the garments are separate elements though they add distinctness to the bodies of the persons. Each color is very distinct though successfully and powerfully pierced through with other hues. Michelangelo painted the perfect muscled bodies in flawless lines and balance. Moreover, the figures of The Last Judgement are considered to be the implementation of feelings (Partridge, p.81).

It is decidedly that the symmetry in the painting by Michael Angelo is thoroughly kept to. The entire piece of art represents proportional picture of souls and other characters approaching Christ. And this symmetry is somewhat fearful, enhanced by the flame emerging from beneath the Earth, from Hell. The focal area is the center, of course, Christ with his helpers – angels, and his mother. The entire painting seems to stream in the center to Christ. However, there is definitely a unity observed due to symmetrically depicted images of people on the left side and right side of the fresco.

The analysis of the representation of The Last Judgment provides deep understanding of the context and content of work, which are inherently interrelated immensely. The intrinsic and extrinsic meanings relate to each other through the desire to provide and willingness to acquire the religious education depicted in the painting. The Last Judgment reveals spoken and unspoken sets of social rules inherent in medieval urban life, moreover, they happen to be presented in the painting as legalized divine judgment. Although the painting had to undergo serious changes through centuries and misunderstandings due to religious belief, it is still situated in Sistine Chapel in order to remind viewers about the attempts of Michelangelo’s contemporaries to reach God and give us an opportunity not to lose faith.

Angelo, Michael. The Last Judgement. 1537 – 1541. Sistine Chapel, Vatican City. Web.

Barnes, Bernadine. Michelangelo’s Last Judgment: The Renaissance Response. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1998. Print.

Fiero, Gloria. The Humanistic Tradition Volume II: The Early Modern World to the Present. Desoto: McGraw-Hill, 2010. Print.

Partridge, Loren. Michelangelo: The Last Judgement – A Glorious Restoration. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, January 8). "The Last Judgement" by Michael Angelo. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-last-judgement-by-michael-angelo/

""The Last Judgement" by Michael Angelo." IvyPanda , 8 Jan. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/the-last-judgement-by-michael-angelo/.

IvyPanda . (2022) '"The Last Judgement" by Michael Angelo'. 8 January.

IvyPanda . 2022. ""The Last Judgement" by Michael Angelo." January 8, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-last-judgement-by-michael-angelo/.

1. IvyPanda . ""The Last Judgement" by Michael Angelo." January 8, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-last-judgement-by-michael-angelo/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . ""The Last Judgement" by Michael Angelo." January 8, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-last-judgement-by-michael-angelo/.

- Richard Angelo: A Serial Killer and His Ethical Dilemma

- Social Inequalities in HBO’s "The Wire"

- The Sistine Chapel Painting by Buonarroti Michelangelo

- Da Vinci's and Michelangelo's Paintings Comparison

- Rent Laws: Violation & Justification

- Management Issues: "Organizational Behavior" by Robert Kreitner and Angelo Kinicki

- Growing Up with Hearing Loss

- Fundamentals Law in Australia

- Lease Contract With Different Terms

- Michelangelo’s “Sistine Chapel Ceiling” Artwork

- Modernism in Delacroix's "Liberty Leading the People" and Lichtenstein's "Drowning Girl"

- Virgin and Child', 1360 by Barnaba da Modena

- The Evolution of the Chinese Brush Painting

- Anger by Hans-Siebert Von Heister

- Romantic Landscape with Ruined Tower' by Thomas Cole

- Featured Essay The Love of God An essay by Sam Storms Read Now

- Faithfulness of God

- Saving Grace

- Adoption by God

Most Popular

- Gender Identity

- Trusting God

- The Holiness of God

- See All Essays

- Best Commentaries

- Featured Essay Resurrection of Jesus An essay by Benjamin Shaw Read Now

- Death of Christ

- Resurrection of Jesus

- Church and State

- Sovereignty of God

- Faith and Works

- The Carson Center

- The Keller Center

- New City Catechism

- Publications

- Read the Bible

- TGC Pastors

U.S. Edition

- Arts & Culture

- Bible & Theology

- Christian Living

- Current Events

- Faith & Work

- As In Heaven

- Gospelbound

- Post-Christianity?

- TGC Podcast

- You're Not Crazy

- Churches Planting Churches

- Help Me Teach The Bible

- Word Of The Week

- Upcoming Events

- Past Conference Media

- Foundation Documents

- Church Directory

- Global Resourcing

- Donate to TGC

To All The World

The world is a confusing place right now. We believe that faithful proclamation of the gospel is what our hostile and disoriented world needs. Do you believe that too? Help TGC bring biblical wisdom to the confusing issues across the world by making a gift to our international work.

The Final Judgment

Other essays.

Final Judgment primarily refers to the eschatological judgment that will take place when Jesus returns to judge the living and the dead, and the recompense (reward or retribution) that day will bring.

This article explores the biblical expectation of eschatological judgment, the significance of faith and works on that final day, and the result of God’s judgment for both the righteous and the wicked. The discussion addresses relevant contemporary debate on justification, the exclusivity of “heaven,” and the enduring nature of eschatological punishment, demonstrating that the biblical evidence supports a conservative evangelical perspective.

The timing of Christ’s return remains unknown to us (Matt 24:36), but attendant events of that final day are plainly disclosed in Scripture: the dead will be raised (John 5:28–29; Acts 24:15) and all humanity — along with rebellious angels (2Pet 2:4; Jude 6) — will be divinely judged (Rom 2:5–16; 2Cor 5:10a; Rev 20:11–13); consequently, everyone will receive the appropriate reward or punishment (2Cor 5:10b; Rev 20:14–21:8). These basic facts are clear, but there is considerable debate over the finer details, such as the significance of final judgment for Christians, how their final destiny should be understood, and the enduring nature of eschatological punishment.

The Biblical Expectation of Eschatological Judgment

While the Old Testament portrays God as the righteous judge of all the earth (cf. Gen 18:25; 1Sam 2:10; 1Chr 16:33) who holds both individuals and nations accountable for their actions (e.g., Deut 32:41; Psa 110:6; Job 19:29; Eccl 3:17; 11:9; Ezek 33:20; Jer 25:31; Joel 3:2), such divine judgment — often referred to as “the day of the LORD” or simply “that day” — is usually confined to the historical realm (i.e., military overthrow, physical curse and/or death); seldom, if ever, does it refer to a final, eschatological or eternal judgment. Some texts may arguably allude to such (e.g., Psa 1:5; Eccl 3:17; 11:9; 12:14), but the closest we get to a final assize in the Old Testament is the scene in Daniel 7, where the Ancient of Days presides over a heavenly court at which books are opened, the terrifying fourth beast is destroyed in blazing fire, and the eternal kingdom is given to God’s holy people. Arguably the same scenario is portrayed somewhat differently in Daniel 12, where those sleeping in the dust of the earth awake — some to glory and everlasting life, others to shame and everlasting contempt. In any case, there is little doubt that both these texts inform the New Testament’s portrayal of the ultimate Day of the Lord and the final judgment.

Such a climactic “day of judgment,” culminating in eternal reward or punishment, is much more prominent in the New Testament, as with most Jewish apocalyptic literature around the first century. The prospect of a final judgment is very clear in the teaching of Jesus, especially in the First Gospel (e.g., Matt 7:21–23; 10:15; 11:22, 24; 12:36, 41–42; 13:40–43, 49–50; 16:27; 18:35; 19:28–29; 25:31–46), and the rest of the New Testament reflects a similar emphasis (e.g., Acts 10:42; 17:31; 24:25; Rom 2:5, 16; 14:10; 1Cor 4:5; 2Cor 5:10; 2Tim 4:1, 8; Heb 6:2; 2Pet 3:7; Rev 11:18; 20:11–15).

Even though Jesus has fully borne God’s wrath for those who believe (1Thess 1:10), Christians are not exempt from this final assize (cf. 2Cor 5:10; Rom 14:10–11; Heb 10:30; Jas 3:1l; 1Pet 4:5). However, they can anticipate this day confidently (1John 4:17; cf. Rom 8:1), knowing that they will not “come into judgment” in the sense of eternal condemnation (John 5:24). Even so, it is clear that on this day Jesus as Judge will distinguish between genuine believers and those who have merely claimed to be his followers and servants (Matt 7:21–23; Luke 12:46). As these and other biblical texts underline, a righteous verdict at the final judgment requires more than just mental assent or verbal commitment to Christ as king. This raises one of the controversial issues in contemporary discussion; namely, the significance of works for a righteous verdict on the last day.

The Role of Faith and Works in Eschatological Judgment

While the relationship between faith and works has been debated from apostolic times (cf. Rom 3–4; Gal 3; Jas 2:14–26), more recently it has become a bone of contention among evangelicals. This is chiefly due to “new perspective” approaches which challenge the Reformation idea of justification by faith alone . Some now distinguish between “first” or “present” justification (being declared righteous by faith) and “second” or “final” justification (being declared righteous by works), seeing these as two distinct stages of salvation rather than as two sides of a single coin. According to traditional Reformed thinking, Christian “good works” are simply evidence of the faith through which God has already declared us righteous — an irrevocable verdict that will simply be confirmed by the divine Judge on the last day. Critics of this traditional Protestant viewpoint understand such works as a crucial factor in an ongoing process — confusing justification with sanctification — and perceive works to play an indispensable and, for some, an instrumental role in securing a righteous verdict on the last day.

It is clear from the New Testament that God justifies us by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone (Rom 5:1–2; Eph 2:8–9). However, it is equally clear that on the last day God will judge us according to works (Rom 14:10–12; 2Cor 5:10). Both these truths must therefore be held in tension, rather than emphasizing one at the expense of the other. God declares us righteous by faith, but it is crucial to understand what genuine faith entails: such faith not only trusts in God, but is given concrete expression through love (e.g., Gal 5:6; 1Jn 4:16–17) and perseverance in doing good (e.g., Matt 5:16; Eph 2:10; Titus 2:14). Accordingly, with the Reformers we can embrace both the scriptural assurances of justification by faith alone and the scriptural exhortations to produce good works as testimony to God’s transforming grace. It would be mistaken to think that such “good works,” imperfect as they are, could ever justify us before God. But it would be equally presumptuous to assume, without such evidence of genuine faith (cf. Phil 2:12), that our names are recorded in the all-important book of life (cf. Rev 20:12; 21:27).

The Eschatological Reward of the Righteous

Popularly referred to simply as “heaven,” the eternal destiny of the righteous is more accurately understood in terms of the kingdom of God, eternal life, and new creation — each of which is experienced in part now, but most fully in the age to come. Despite what several Christian hymns suggest, the final state for Christians will not be in some metaphysical or distant realm, but rather in God’s renovated and perfected creation, “in which righteousness dwells” (2Pet 3:13). Depictions of such eschatological bliss in the Old Testament (e.g., Isa 11:6–9; 65:17–25; 66:18) are very much in keeping with this; rather than a heavenly scenario set in the wild blue yonder, it is a very earthly portrayal, albeit one that is markedly different from the situation in the present world. Such transformation in the New Testament’s portrayal of the new heaven and the new earth is even more striking, for even death itself has been eradicated (Rev 21:4), but once again the dominant picture is of bliss on earth rather than some kind of other-worldly existence in heaven. Thus the eschatological hope for Christians is to enjoy God’s presence and reign on the perfected earth (Rev 21:2–3; 22:3–5) — an earth that is “new” in quality rather than in time (Rev 21:5). It is in this sense of radical transformation that John speaks of the first earth having “passed away” (Rev 21:1), and that Peter speaks of cosmic dissolution (2Pet 3:1–11). Everything that would ruin or corrupt this perfected creation will be eradicated.

However, this wonderful picture of final bliss is one of the things that has led some to question the traditional understanding of final judgment. Until fairly recently, nearly all evangelicals — whether conservative or progressive — would have considered God’s verdict on the last day to be final, and thus the fate of the wicked to be irreversible. In recent decades, however, a small but increasing number have maintained that this is not the case, suggesting that the punishment meted out to the wicked in hell is not simply retributive, but has a restorative purpose. Thus understood, those condemned to hell may still repent of their sin and call on the Lord to be saved; and when they do so — however long that may take — they will join the rest of the redeemed in eternal bliss. However, one of the major problems with such “evangelical universalism” is the fact that Scripture explicitly rejects the possibility of post-mortem repentance or an exit from hell (Luke 13:24–28; 14:24; cf. 16:26), and insists that none can enter the holy city, the new Jerusalem, except for “those who are written in the Lamb’s book of life” (Rev 21:27; cf. 20:15) — something determined before creation (Rev 17:8). Given the serious deficiencies with their theological and exegetical assumptions, universalism is unlikely to gain widespread acceptance among evangelicals.

The Eschatological Punishment of the Wicked

The eschatological fate of the reprobate is never explicitly addressed in the Old Testament. Sheol and related terminology refers to the anticipated post-mortem “afterlife” or underworld, rather than to the final punishment of the wicked in hell. However, the latter is clearly foreshadowed in cataclysmic judgments such as befell Sodom and Gomorrah (cf. 2Pet 2:6; Jude 7; cf. Luke 17:26–30). But the closest the Old Testament explicitly gets to everlasting punishment is in Isaiah 66:24 and Daniel 12:2, where the focus is on the ignominious fate of the wicked and the revulsion or contempt it arouses. However, while both these texts inform subsequent portrayals of hell, unlike the latter, they say little to imply eternal conscious torment.

The final destiny of the wicked is variously portrayed in the New Testament. Drawing from the Old Testament, Jesus most often describes it as Hell/Gehenna (Matt 23:33) — a fate worse than extreme physical loss (Matt 5:29–30) or death (Matt 10:28; Luke 12:4–5), and explicitly associated with unquenchable or eternal fire (Matt 5:22; 18:8; cf. 13:39–40; Jas 3:6). It is difficult to see the necessity of the latter unless the punishment itself is construed as unending. Moreover, the fact that it will induce “weeping and gnashing of teeth” (Matt 13:42, 50; cf. 8:12; 22:13; 24:51; 25:30; Luke 13:28) suggests conscious punishment or torment (cf. Luke 16:23–25; Matt 8:29; Rev 20:10).

Paul never uses the word “Hell/Gehenna” to describe the fate of the wicked; rather, he employs a range of overlapping ideas such as wrath, condemnation, death, perishing, destruction, and being cursed — prompting some to conclude that he had annihilation primarily in mind. However, this is not necessarily what Paul intended, and is difficult to square with his most detailed discussion of God’s coming wrath (2Thess 1:6–9). Here he speaks in terms of “repaying with affliction,” “flaming fire,” “inflicting vengeance,” and “ eternal destruction” — a qualification quite unnecessary if “destruction” just means being annihilated. The same applies to the following phrase (“away from the presence of the Lord …”), which is equally redundant unless there is more to such destruction than simply being consumed by fire. Accordingly, Paul’s thinking seems more aligned with the traditional concept of hell than some have inferred.

The same is true of the General Epistles and Revelation. For example, the author of Hebrews understands the final destruction of the wicked as “much worse punishment” than death — the penalty meted out under the old covenant (Heb 10:29). In a similar vein Peter portrays hell in terms of Tartarus, a mythological subterranean realm where the wicked experienced punishment and torment (2Pet 2:4). But by far the most graphic depictions of hell are recorded in Revelation, where chapters 14 and 19–20 stand out especially. Chapter 14:10–11 speaks of the wicked being “tormented with fire and sulfur in the presence of the holy angels and in the presence of the Lamb,” “the smoke of their torment” ascending forever, and the having “no rest, day or night” (vv.10–11) — imagery that most obviously suggests unending agony. Likewise, chapters 19 and 20 depict the beast, the false prophet, and the devil being thrown into a fiery lake of burning sulphur (19:20; 20:10), where they too “will be tormented day and night forever and ever” (20:10b). Significantly, this same fate awaits the ungodly (Rev 20:14–15; 21:8; cf. Matt 25:41). Attempts to interpret these texts more palatably — in terms of an unquenchable fire that finally consumes its victims — are far from convincing; the wicked are not depicted in the closing chapters of this book as eradicated, but excluded (cf. Rev 21:27; 22:15, 19). Accordingly, while some biblical texts can be used to support the idea of terminal punishment (i.e., annihilationism), others stubbornly resist such interpretation.

Further Reading

In relation to Biblical Theology

- Purchase: Amazon

- Review: TheScriptureSays

- Anthony Hoekema

- Reviews: MatGilbertBlog

In relation to contemporary debates on the role of works in the final judgment

- “ Justified by Faith, judged according to works: Another look at a Pauline Paradox ”

- Alan Stanley

- Review: GraceEvangelicalSociety

- Alan Stanley (ed.)

- Review: TGC

- Paul R. Williamson

- Author interview: Books At a Glance

- Review: Themelios

In relation to contemporary debates on heaven and hell

- Christopher Morgan and Robert A. Peterson (eds)

- Review: WordPress

- Preston Sprinkle (ed.)

- Reviews: Apologetics315, MJTM

This essay is part of the Concise Theology series. All views expressed in this essay are those of the author. This essay is freely available under Creative Commons License with Attribution-ShareAlike, allowing users to share it in other mediums/formats and adapt/translate the content as long as an attribution link, indication of changes, and the same Creative Commons License applies to that material. If you are interested in translating our content or are interested in joining our community of translators, please reach out to us .

- Free Samples

- Premium Essays

- Editing Services Editing Proofreading Rewriting

- Extra Tools Essay Topic Generator Thesis Generator Citation Generator GPA Calculator Study Guides Donate Paper

- Essay Writing Help

- About Us About Us Testimonials FAQ

- Studentshare

- Visual Arts & Film Studies

- Art History: Michelangelo's The Last Judgement

Art History: Michelangelo's The Last Judgement - Essay Example

- Subject: Visual Arts & Film Studies

- Type: Essay

- Level: Ph.D.

- Pages: 5 (1250 words)

- Downloads: 2

- Author: seth29

Extract of sample "Art History: Michelangelo's The Last Judgement"

The sixteenth-century was a turbulent period for Western Europe (Hammer 3). Both France and Spain, two newly formed Imperial powers, saw Italy as a threat. As a result, France invaded Italy first and Spain followed suit shortly after that. A decade-long power struggle ensued that left much of northern Italy devastated. In 1525, Spain drove France out of Italy and single-handedly concentrated on destroying Italy. In 1527, Spain took its attack on Italy a notch higher when it sent twelve thousand mercenaries to Rome.

Within eight days, the solders left the city in ruins. Everything in Rome and the whole of Italy, including artistic life, came to a halt. It appeared as though Spain had destroyed the foundation of the Renaissance culture. Besides the political turmoil, Europe was also experiencing an economic upheaval. More than ever before, political power had become tied to economic power and the political elite had become heavily dependent on bankers (Hammer 3). Thus, when most bankers became bankrupt because of the political upheaval, so did the ruling classes.

Social unrest ensued. The unrest encompassed the poor as well as religious and intellectual dissidents. At this time, the influence of religion on people’s lives was heavy. Thus, religion easily became the unifying factor for the various revolutionary forces of the period. At the same time corruption was rampant in the Church and the clergy were considered highly materialistic, accumulating personal wealth at the expense of Christians. It was this period of revolutionary unrest that historians later termed the Protestant Reformation or Protestantism (Hammer 3).

In essence, Protestantism was a period of spiritual rebirth (Sokstad and Cothren 633). Throughout Western Europe, and especially in Italy, idealists and intellectuals were preoccupied with the notions of anti-materialism, a direct

- Cited: 0 times

- Copy Citation Citation is copied Copy Citation Citation is copied Copy Citation Citation is copied

CHECK THESE SAMPLES OF Art History: Michelangelo's The Last Judgement

Michelangelo's last judgement, luca signorelli and his work at orvieto, vision of an art museum, artist report paper, anatomical interpretation of the concept of mind, the significance of main religious buildings, jos clemente orozcos la trinchera and michelangelos fresco.

- TERMS & CONDITIONS

- PRIVACY POLICY

- COOKIES POLICY

- Environment

- Information Science

- Social Issues

- Argumentative

- Cause and Effect

- Classification

- Compare and Contrast

- Descriptive

- Exemplification

- Informative

- Controversial

- Exploratory

- What Is an Essay

- Length of an Essay

- Generate Ideas

- Types of Essays

- Structuring an Essay

- Outline For Essay

- Essay Introduction

- Thesis Statement

- Body of an Essay

- Writing a Conclusion

- Essay Writing Tips

- Drafting an Essay

- Revision Process

- Fix a Broken Essay

- Format of an Essay

- Essay Examples

- Essay Checklist

- Essay Writing Service

- Pay for Research Paper

- Write My Research Paper

- Write My Essay

- Custom Essay Writing Service

- Admission Essay Writing Service

- Pay for Essay

- Academic Ghostwriting

- Write My Book Report

- Case Study Writing Service

- Dissertation Writing Service

- Coursework Writing Service

- Lab Report Writing Service

- Do My Assignment

- Buy College Papers

- Capstone Project Writing Service

- Buy Research Paper

- Custom Essays for Sale

Can’t find a perfect paper?

- Free Essay Samples

Michelangelo's Last Judgment

Updated 04 August 2023

Downloads 33

Category Art , Religion

Topic Michelangelo , Painting

The Last Judgment - Background

The Last Judgment, done between 1536 and 1541 by Michelangelo, covers the whole altar wall of the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City. The time of the painting came shortly after two significant happenings in the history of Catholicism. One was the surge of the Protestant Reformation, inspired by the insights of Martin Luther King, while the second one was the sacking of Rome by the armies of King Charles V. The Protestant Reformation was a break from the Catholic Church by some European countries due to the continued decadence of the papacy. This was especially during the reigns of Popes Leo X and Clement VII who were both descendants of the Florentine Medici Family. One of the main reasons for the Protestant Reformation was the Pope's dependence on the sale of indulgences to fund their earthly exploits such as art commissions, as opposed to free grace through faith espoused in the gospels (Leffler and Jones 102).

The Commission and Intentions

Initially commissioned by Pope Clement VII and later confirmed by Pope Paul III, the painting served to communicate the Catholic Church's response to the wave of Protestantism spreading through Europe, the onslaught from the pillaging armies, and the citizenry that chose to abandon Catholicism. Through the painting, the papacy sought to reestablish the paramount position of the Catholic Church in the second coming of Christ and the ensuing judgment. The art in the chapel further served to reinforce the Pope as the only true temporal conduit to salvation from doom. Clement VII commissioned the painting of the altar wall under the theme of resurrection, but upon his death, Pope Paul redefined the subject to the last judgment, since it resonated well with the 1530s Rome. The vivid depiction of the last judgment would help jolt the citizenry and remind them of the dire consequences of disregarding Catholicism as earlier embodied in the Protestant Reformation and the sack of Rome. Papal propaganda and Catholic dogma manifested themselves in the painting, given its time context (Leader 106).

Political Context

Significant political developments in Europe preceded and set the stage for the painting of the Last Judgement. The political ambitions of Pope Julius II, his expansion of the Papal States, and his foreign policy positioned the Catholic Church at odds with the Roman Empire, led by Emperor Charles. To make it worse, the Papal States sided with King Francis of France in his defeat to the Empire. The Empire's disregard of the Pope's primacy culminated in the sack of Rome in 1527. The painting, therefore, helped to invigorate the Catholic Church and to affirm the rule of the papacy (Leader 106).

Artistic Style

The picture's composition is indicative of the late Renaissance, also known as Mannerism. This is the period in art between the death of Raphael and the rise of the baroque style in the early 1600s. As opposed to the high Renaissance that enjoyed the lavish patronage of the arts by the papacy, the late Renaissance occurred when the forces of reform held that indulgence in art was secular. In the Last Judgment, the depiction of disquieting, overly emotional figures goes against the traditional norm. The artist's use of vivid colors in the skin tones, the blue color of the sky, and orange tones indicate its mannerist composition and a clear departure from the earlier instances of the Renaissance. The bizarre nature of themes, borrowed from Christianity, mythology, and classicism, further illustrates the mannerist leanings of the masterpiece. Michelangelo combined the biblical narrative of the second coming of Christ, the classical Dante's Divine Comedy, and figures from Greek mythology, such as the figure of Minos. Moreover, the interest in the human anatomy and its detailing also strongly links the Last Judgment to the late Renaissance period. Michelangelo arranges the human forms in postures that help to illustrate the elegance of the human body. As opposed to the serenity, symmetry, and observance of classical proportions epitomized by early and high Renaissance compositions, late Renaissance compositions featured dynamism, asymmetry, and distortion, as evident in the Last Judgment (Bodart 176).

Religious Themes

The primary religious theme in the painting is the second coming of Jesus, with the resurrection of the dead and final judgments. In the artwork, Michelangelo depicts Jesus as the dominant figure at the center, with the Virgin Mary beside him, surrounded by recognizable biblical characters. The resurrection of the dead happens on the bottom left of the fresco, where skeletons and entire bodies emerge from their graves and rise towards Christ for Judgement. The Virgin Mary seems to look aside from the impending wrath of her son, seemingly unable to intercede for the sinful souls any longer. The condemnation of sinners, seen descending to their fates to the bottom right of the fresco, is a vivid image meant to remain with the observer and possibly remind them to be better persons. The agony etched on the face of the sole damned man, descending to hell aided by two demons, is a cause for self-interrogation for any observer, who has to ponder their final destination and act accordingly (Bambach 211).

In conclusion, the Last Judgment is one of the most famous yet controversial paintings of all time. The piece was commissioned by Pope Clement VII and confirmed by Pope Paul III. Furthermore, the artwork was a reaction to the broader raft of issues happening around the Vatican, Rome, and Europe.

Works Cited

Bambach, Carmen. Michelangelo. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2017. Print.

Bodart, Diane. Renaissance & Mannerism. New York: Sterling Pub. Co., 2008. Print.

Leader, Anne. Michelangelo’S Last Judgment: The Culmination of Papal Propaganda in the Sistine Chapel. 2006. Web. 9 Mar. 2018.

Leffler, William J, and Paul H Jones. The Structure of Religion. Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 2005. Print.

Deadline is approaching?

Wait no more. Let us write you an essay from scratch

Related Essays

Related topics.

Find Out the Cost of Your Paper

Type your email

By clicking “Submit”, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy policy. Sometimes you will receive account related emails.

- Subscriber Login

Since 1900, the Christian Century has published reporting, commentary, poetry, and essays on the role of faith in a pluralistic society.

© 2023 The Christian Century.

Contact Us Privacy Policy

Last Judgment , by Gislebertus (ca. 1130)

Art selection and commentary by Heidi J. Hornik and Mikeal C. Parsons

The medieval Cathedral of St. Lazare in Autun, France, constructed in about 1120, contained relics of St. Lazarus. Pilgrims to the church were greeted at the entrance by a sculpture of the last judgment. The sculpture is signed “Gislebertus hoc fecit” (Gislebertus made this), confirming the sculptor’s identity in a way that is uncommon in the medieval era. Christ is in the center of the composition in a mandorla , or almond-shaped frame. Below Christ, the dead are rising, and they line up to have their souls weighed. An angel with a trumpet summons all creatures to judgment. Angels and demons fight at the scales where souls are being weighed, as each tries to manipulate the scale for or against a soul. In 1766, the apocalyptic imagery was considered offensive, and the tympanum was covered with plaster. The head of Christ, which projected outward, was broken off to facilitate a flat surface. The head was rediscovered and restored to its position in the recovered work in 1948.

We would love to hear from you. Let us know what you think about this article by emailing our editors .

Most Recent

Psalm 23 in conversation (acts 4:5-12; psalm 23; 1 john 3:16-24; john 10:11-18).

by Austin Shelley

Centering Chloe and decentering Paul

Border encounters, a novel driven by kindness, most popular.

Early Christianity, fragment by fragment

How might God bless a divided America?

The buddy-cop feminist detective series I didn’t know I needed

In praise of church musicians

ESSAY SAUCE

FOR STUDENTS : ALL THE INGREDIENTS OF A GOOD ESSAY

Essay: ‘The Last Judgement’ by John Martin

Essay details and download:.

- Subject area(s): Photography and arts essays

- Reading time: 3 minutes

- Price: Free download

- Published: 19 September 2022*

- File format: Text

- Words: 889 (approx)

- Number of pages: 4 (approx)

Text preview of this essay:

This page of the essay has 889 words. Download the full version above.

‘The Last Judgement’ was painted in 1853 by John Martin. It is oil on canvas and has the measurements, including the frame, of 240 x 368.5 x 17.5cm. The painting is part of a triptych, including ‘The Great Day of His Wrath’ and ‘The Plains of Heaven’. It is held at the Tate Britain in the Display Room of The Art of Ray Harryhausen, with the theme of Spotlights. The paintings were produced at the end of Martin’s career and before his death in 1854. He had the intention of touring them as popular spectacles. The paintings travelled from America to Australia, being shown in a wide range of countries. They were also reproduced as engravings, which extended their reach even further. Their influence, created by their fame, helped break ground for modern forms of popular entertainment – including blockbuster cinema. ‘The Last Judgement’ and the two other paintings of the triptych are considered to be Martin’s most influential achievements and his masterpiece. Martin was above all ambitious, he is widely quoted declaring “I will bring before the eye the vast and magnificent edifices of the ancient world”, and that is what he did.

The subjects of the paintings are taken from ‘The Book of Revelation’, the painting represents the centred event of the Book and is a composition of various passages from the narrative. ‘The Book of Revelation’ is a book of the New Testament that dominates a place in Christian eschatology. The initial sketches of The Last Judgement were of specific sections, that featured in the painting. The most famous sketch is of the lower half of the painting. This sketch illustrates the centred event of the Book of Revelation and shows the striking detail of the painting. This included a railway train plunging into the bottomless pit. The painting displays God, in Heaven, sat on a throne in judgement. Before him sits the four and twenty elders. The trumpets of the four angels sounded after the Seventh Seal was opened. As the last bridge over the Valley of Jehoshaphat is collapsing, many race across it to Jerusalem and its safety. Beneath to the right, Satan’s forces of evil are conquered and the armies of Gog and Magog, God’s people’s enemy nations, fall into the bottomless pit. On Mount Zion, to the left, are the good who are already in the ‘plains of heaven’, waiting to be called upon to appear before the throne. The main figures were later identified in 1855 when an engraved key to accompany the picture was published by Leggatt, Haward and Leggatt. The richly dressed woman, primarily Herodias’s daughter and the whore of Babylon, churchmen and lawyers who only strived for wealth were amongst the damned to the left of God. On the other side, are the saved. These are anonymous figures consisting of innocent children, honourable women and people of worthy morals. Together with the good, Martin incorporated numerous artists and poets, in addition to philosophers and statesmen. Included was, Dante, Newton, Shakespeare, Michelangelo and many others. These notable men are varied in a montage of a timeless fashion. The pictorial language used by Martin to render visible this new paradise was the wholly conventional and familiar one of classical landscape painting on the model of the seventeenth-century French artist Claude Lorrain (1600–1682), pursued in the modern age most influentially by J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851) (Myrone (2012) provided this statement).

Your eyes are directly drawn to the focus point. This is God on the throne, just off the centre of the painting. This is because it is the brightest part and is emphasised due to the contrast of being surrounded by dark colours. But as you begin to study the painting, you then come across other details, such as the good in the ‘plains of heaven’ and Satan’s forces of evil, in the bottom corners. Below God in the throne, at the centre of the painting, the features of the painting begins to merge into the bottomless pit, as if falling into the darkness. This factor shows symmetrical balance. As you start at the focal point you then begin to go clockwise as one of the angels is facing to the right of the painting. You are then drawn to a figure in the bottom right corner, part of the forces of evil, to which you follow to the abyss and the see the good, on the ‘plains of heaven’, in the bottom left corner. The throne and its surroundings are placed on a horizontal ‘ledge’ as if raised above the goings-on below. This also links to the colour palette of the painting, there is a clear divide between light and dark colours as if signifying ‘heaven and hell’. A dark foreground with dense foliage rising to the left and to the right in a balanced formation gives way to an expansive landscape view with rivers, lakes and waterfalls, characterised by bands of warm and cool colour and dissolving into a blinding golden light which consumes the towering mountain scenery in the far distance (Myrone (2012) provided this statement). The triptych was the pivotal attraction of the first of many exhibitions of Martin’s work, which was held at the Tate Britain in 2011-12. The exhibition was accompanied by a theatrical son et lumière show which dramatized the approach of the exhibition.

...(download the rest of the essay above)

About this essay:

If you use part of this page in your own work, you need to provide a citation, as follows:

Essay Sauce, ‘The Last Judgement’ by John Martin . Available from:<https://www.essaysauce.com/photography-arts-essays/the-last-judgement-by-john-martin/> [Accessed 13-04-24].

These Photography and arts essays have been submitted to us by students in order to help you with your studies.

* This essay may have been previously published on Essay.uk.com at an earlier date.

Essay Categories:

- Accounting essays

- Architecture essays

- Business essays

- Computer science essays

- Criminology essays

- Economics essays

- Education essays

- Engineering essays

- English language essays

- Environmental studies essays

- Essay examples

- Finance essays

- Geography essays

- Health essays

- History essays

- Hospitality and tourism essays

- Human rights essays

- Information technology essays

- International relations

- Leadership essays

- Linguistics essays

- Literature essays

- Management essays

- Marketing essays

- Mathematics essays

- Media essays

- Medicine essays

- Military essays

- Miscellaneous essays

- Music Essays

- Nursing essays

- Philosophy essays

- Photography and arts essays

- Politics essays

- Project management essays

- Psychology essays

- Religious studies and theology essays

- Sample essays

- Science essays

- Social work essays

- Sociology essays

- Sports essays

- Types of essay

- Zoology essays

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS