Does Government Spending Cause Investment?: A Panel Data Analysis

- Conference paper

- First Online: 01 April 2021

- Cite this conference paper

- Nihal Bayraktar 3

Part of the book series: Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics ((SPBE))

Included in the following conference series:

- International Conference on Applied Economics

566 Accesses

1 Citations

Government spending has increased recently in almost all countries to ease the severely negative economic impacts of the current health crisis. Similar expansionary fiscal and monetary policies were observed during other economic downturns too. The effectiveness of expansionary policies, especially in terms of their effects on investment, has been discussed widely. Thanks to the possible multiplier effect of higher government expenditures, it is expected that government spending would generate a higher amount of income and therefore consumption in economies. At some point, this higher government spending with glowing economic activities is expected to increase private investment—an important item to promote job creations and improvements in production. Although one of the direct or indirect expected outcome of higher government spending is larger investment, many empirical studies in the literature cannot observe this positive expected effect of government spending on investment. As a result, even the necessity of increased government expenditures during economic crisis has been questioned. In this paper, the causal and correlation relationship between government spending and investment is investigated in a panel data setting to better evaluate the importance of higher government spending during economic downturns. The findings show that country classifications based on income, time periods covered in the analysis, measures of government spending and investment, and the time lag of government policies can make a difference. There are cases where government spending highly significantly causes private investment, and high correlations between two variables are observed. Therefore, accurate evaluations of the impacts of government spending on investment may require detailed data analysis.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Afonso, A., & Jalles, J. T. (2015). How does fiscal policy affect investment? Evidence from a large panel. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 20 (4), 310–327.

Article Google Scholar

Afonso, A., & Sousa, R. M. (2009). The macroeconomic effects of fiscal policy . European Central Bank Working Paper 991.

Google Scholar

Afonso, A., & Sousa, R. M. (2011). The macroeconomic effects of fiscal policy in Portugal: A Bayesian SVAR analysis. Portuguese Economic Journal, 10 (1), 61–82.

Alesina, A., Ardagna, S., Perotti, R., & Schiantarelli, F. (2002). Fiscal policy, profits, and investment. American Economic Review, 92 (3), 571–589.

Barro, R. J., & Redlick, C. J. (2011). Macroeconomic effects from government purchases and taxes. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126 (1), 51–102.

Bayraktar, N., & Fofack, H. (2011). Capital accumulation in sub-Saharan Africa: Income-group and sector differences. Journal of African Economies, 20 (4), 531–561.

Bayraktar, N., & Fofack, H. (2018). A model for gender analysis with informal production and financial sectors. Journal of African Development, 20 (2), 1–20.

Bayraktar, N., & Moreno-Dodson, B. (2015). How can public spending help you grow? An empirical analysis for developing countries. Bulletin of Economic Research, 67 (1), 30–64.

Bayraktar, N., & Moreno-Dodson, B. (2018). Public expenditures and growth in a Monetary Union: The case of WAEMU. Eurasian Journal of Economics and Finance, 6 (1), 107–132.

Furceri, D., & Sousa, R. M. (2011). The impact of government spending on the private sector: Crowding-out versus crowding-in effects. Kyklos, 64 (4), 516–533.

Granger, C. W. J. (1969, July). Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica, 37 , 424–38.

Laopodis, N. T. (2001). Effects of government spending on private investment. Applied Economics, 33 (12), 1563–1577.

Mackintosh, J. (2020, March 29). After Coronavirus, we will have to reckon with the debt. The Wall Street Journal . Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/after-coronavirus-we-will-have-to-reckon-with-the-debt-11585494002

Şen, H., & Kaya, A. (2014). Crowding-out or crowding-in? Analyzing the effects of government spending on private investment in Turkey. Panoeconomicus, 61 (6), 631–651.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Penn State University—Harrisburg, Middletown, PA, USA

Nihal Bayraktar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nihal Bayraktar .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Laboratory of Applied Economics, Department of Economics, University of Western Macedonia, Kastoria, Greece

Nicholas Tsounis

Aspasia Vlachvei

Appendix: List of Countries

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Bayraktar, N. (2021). Does Government Spending Cause Investment?: A Panel Data Analysis. In: Tsounis, N., Vlachvei, A. (eds) Advances in Longitudinal Data Methods in Applied Economic Research. ICOAE 2020. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63970-9_13

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63970-9_13

Published : 01 April 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-63969-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-63970-9

eBook Packages : Economics and Finance Economics and Finance (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets & Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Social Impact

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Get Involved

- Reading Materials

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

Estimating the Incidence of Government Spending

This paper analyzes the economic incidence of sustained changes in federal government spending at the local level. We use a new identification strategy to isolate geographical variation in formula-based federal spending and develop three sets of results. First, we find that sustained changes in federal spending have significant effects on migration, income, wages, and rents, as well as on local government revenues and expenditures. Second, we show that the effects of a government spending shock are qualitatively different from those of a local labor demand shock. We develop a spatial equilibrium model to show that when workers value publicly-provided goods, a change in government spending at the local level will affect equilibrium wages through shifts in both the labor demand and supply curves. We test the reduced-form predictions of the model and show that workers value government services as amenities. Finally, we estimate workers’ marginal valuation of government services and find that unskilled workers have a higher valuation of government services than skilled workers. We use these estimates to decompose the demand and supply components of a government spending shock and to evaluate the impacts on welfare that are produced by increasing government spending in a given area. Our estimates conclude that an additional dollar of government spending increases welfare by $1.45 in the median county.

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

Read our research on: Gun Policy | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

6 facts about americans’ views of government spending and the deficit.

As President Joe Biden and congressional Republicans continue to negotiate on raising the U.S. debt ceiling , the public has nuanced views on related issues such as the preferred size of government, the amount of government assistance to the poor, and the priority of reducing the budget deficit. Here are six facts about Americans’ views of the government, spending and the deficit based on Pew Research Center surveys from this year.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to provide insight into the public’s views about the size of government and aspects of government spending and revenue as President Joe Biden and Congress continue negotiations around the debt ceiling. For this analysis, we included data from two surveys in 2023: one with 5,152 U.S. adults conducted Jan. 18-24 and the second with 5,079 U.S. adults conducted March 27-April 2.

Everyone who took part in these surveys is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Here is the question from the Jan. 18-24 survey used in this analysis, along with responses, and its methodology . Here are materials for the questions on taxes and government size and role from the March 27-April 2 survey, along with its methodology .

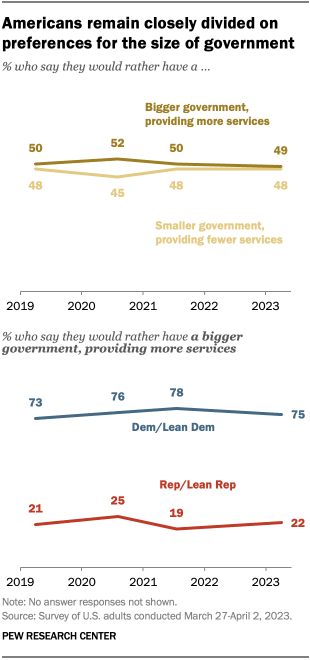

The public remains split on what the government’s size should be. About half of Americans (49%) say they would rather have a bigger government providing more services, while a similar share (48%) would prefer a smaller government providing fewer services, according to a Center survey conducted March 27-April 2. These views have remained relatively stable since 2019. Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are more than three times as likely as Republicans and Republican leaners to say they would prefer a bigger government (75% vs. 22%).

The public is also divided on the role of government. While 52% say government should be doing more to solve problems, 46% say government is doing too many things that would be better left to businesses and individuals. These attitudes are also deeply divided along partisan lines: While about three-quarters of Democrats (77%) say the government should do more to solve problems, a similar share of Republicans (75%) say the government is doing too many things.

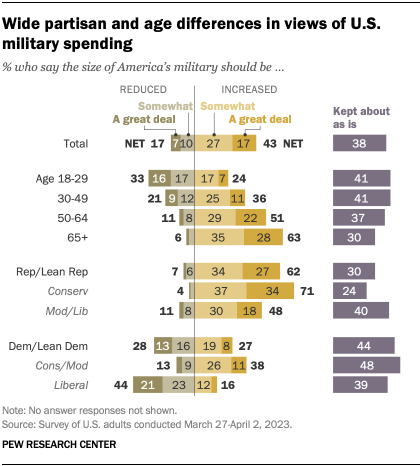

Americans are more likely to want to increase than reduce the size of the U.S. military. About four-in-ten Americans (43%) say that the size of the U.S. military should be increased, compared with 17% who say it should be reduced; 38% say it should be kept about as is. The share of the public saying the military should expand has risen 6 percentage points since July 2021. Currently, military spending makes up about 12% of the overall federal budget but nearly half of so-called discretionary spending, which excludes entitlement programs such as Social Security and Medicare.

Republicans are far more likely than Democrats (62% vs. 27%) to favor increasing the size of the military. There also are age differences: Older adults are more supportive than younger adults when it comes to expanding the size of the military.

More Americans also favor increasing, rather than reducing, government aid to the poor. While 43% favor increasing aid to the poor, 26% say the government should provide less assistance, and 30% say the current level of aid is about right. Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to say the government should provide more assistance to those in need, but Republicans’ views vary by age and income. Younger and lower-income Republicans are more likely than older and higher-income Republicans to say that the government should provide more assistance to those in need.

Majorities favor raising taxes on large companies and high earners. About two-thirds of Americans (65%) say that tax rates on large businesses and corporations should be raised. A somewhat similar share (61%) support raising tax rates on household incomes over $400,000. On both questions, Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to say that tax rates should be increased.

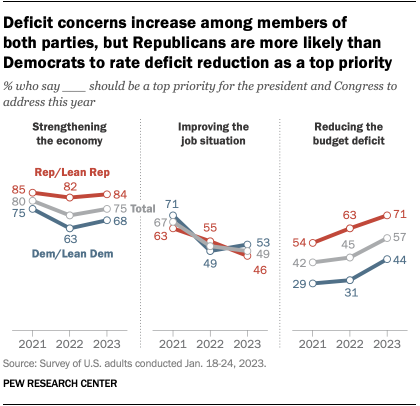

Reducing the budget deficit is a higher priority for the public than it was last year. The share of the public saying that reducing the budget deficit should be a top priority for the president and Congress this year has increased by 12 points since 2022, according to a January 2023 Center survey . Today, 57% say that reducing the budget deficit should be a top priority, compared with 45% in 2022. Both Republicans and Democrats are more likely now than in 2022 to say this should be a top priority, but Republicans are still much more likely to prioritize this than Democrats are (71% vs. 44%).

Note: Here is the question from the Jan. 18-24 survey used in this analysis, along with responses, and its methodology . Here are materials for the questions on taxes and government size and role from the March 27-April 2 survey, along with its methodology .

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

Congress has long struggled to pass spending bills on time

What the data says about food stamps in the u.s., inflation, health costs, partisan cooperation among the nation’s top problems, 5 facts about the u.s. national debt, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- Election Integrity

- Immigration

Political Thought

- American History

- Conservatism

- Progressivism

International

- Global Politics

- Middle East

Government Spending

Budget and Spending

Energy & Environment

- Environment

Legal and Judicial

- Crime and Justice

- Second Amendment

- The Constitution

National Security

- Cybersecurity

Domestic Policy

- Government Regulation

- Health Care Reform

- Marriage and Family

- Religious Liberty

- International Economies

- Markets and Finance

The Impact of Government Spending on Economic Growth

Key takeaways.

Most government spending has a negative economic impact.

The deficit is not the critical variable. The key is the size of government, not how it is financed.

There is overwhelming evidence that government spending is too high and that America's economy could grow much faster if the burden of government was reduced.

Select a Section 1 /0

For more on government spending, read Brian Reidl's new paper "Why Government Does Not Stimulate Economic Growth" ------

For more information, see the supplemental appendix to this paper. Policymakers are divided as to whether government expansion helps or hinders economic growth. Advocates of bigger government argue that government programs provide valuable "public goods" such as education and infrastructure. They also claim that increases in government spending can bolster economic growth by putting money into people's pockets.

Proponents of smaller government have the opposite view. They explain that government is too big and that higher spending undermines economic growth by transferring additional resources from the productive sector of the economy to government, which uses them less efficiently. They also warn that an expanding public sector complicates efforts to implement pro-growth policies-such as fundamental tax reform and personal retirement accounts- because critics can use the existence of budget deficits as a reason to oppose policies that would strengthen the economy.

Which side is right?

This paper evaluates the impact of government spending on economic performance. It discusses the theoretical arguments, reviews the international evidence, highlights the latest academic research, cites examples of countries that have significantly reduced government spending as a share of national economic output, and analyzes the economic consequences of those reforms. 1 The online supplement to this paper contains a comprehensive list of research and key findings.

This paper concludes that a large and growing government is not conducive to better economic performance. Indeed, reducing the size of government would lead to higher incomes and improve America's competitiveness. There are also philosophical reasons to support smaller government, but this paper does not address that aspect of the debate. Instead, it reports on-and relies upon-economic theory and empirical research. [1]

The Theory: Economics of Government Spending

Economic theory does not automatically generate strong conclusions about the impact of government outlays on economic performance. Indeed, almost every economist would agree that there are circumstances in which lower levels of government spending would enhance economic growth and other circumstances in which higher levels of government spending would be desirable.

If government spending is zero, presumably there will be very little economic growth because enforcing contracts, protecting property, and developing an infrastructure would be very difficult if there were no government at all. In other words, some government spending is necessary for the successful operation of the rule of law. Figure 1 illustrates this point. Economic activity is very low or nonexistent in the absence of government, but it jumps dramatically as core functions of government are financed. This does not mean that government costs nothing, but that the benefits outweigh the costs.

Costs vs. Benefits. Economists will generally agree that government spending becomes a burden at some point, either because government becomes too large or because outlays are misallocated. In such cases, the cost of government exceeds the benefit. The downward sloping portion of the curve in Figure 1 can exist for a number of reasons, including:

- The extraction cost. Government spending requires costly financing choices. The federal government cannot spend money without first taking that money from someone. All of the options used to finance government spending have adverse consequences. Taxes discourage productive behavior, particularly in the current U.S. tax system, which imposes high tax rates on work, saving, investment, and other forms of productive behavior. Borrowing consumes capital that otherwise would be available for private investment and, in extreme cases, may lead to higher interest rates. Inflation debases a nation's currency, causing widespread economic distortion.

- The displacement cost. Government spending displaces private-sector activity. Every dollar that the government spends necessarily means one less dollar in the productive sector of the economy. This dampens growth since economic forces guide the allocation of resources in the private sector, whereas political forces dominate when politicians and bureaucrats decide how money is spent. Some government spending, such as maintaining a well-functioning legal system, can have a high "rate-of-return." In general, however, governments do not use resources efficiently, resulting in less economic output.

- The negative multiplier cost. Government spending finances harmful intervention. Portions of the federal budget are used to finance activities that generate a distinctly negative effect on economic activity. For instance, many regulatory agencies have comparatively small budgets, but they impose large costs on the economy's productive sector. Outlays for international organizations are another good example. The direct expense to taxpayers of membership in organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is often trivial compared to the economic damage resulting from the anti-growth policies advocated by these multinational bureaucracies.

- The behavioral subsidy cost. Government spending encourages destructive choices. Many government programs subsidize economically undesirable decisions. welfare programs encourage people to choose leisure over work. Unemployment insurance programs provide an incentive to remain unemployed. Flood insurance programs encourage construction in flood plains. These are all examples of government programs that reduce economic growth and diminish national output because they promote misallocation or underutilization of resources.

- The behavioral penalty cost. Government spending discourages productive choices. Government programs often discourage economically desirable decisions. Saving is important to help provide capital for new investment, yet the incentive to save has been undermined by government programs that subsidize retirement, housing, and education. Why should a person set aside income if government programs finance these big-ticket expenses? Other government spending programs-Medicaid is a good example-generate a negative economic impact because of eligibility rules that encourage individuals to depress their incomes artificially and misallocate their wealth.

- The market distortion cost. Government spending distorts resource allocation. Buyers and sellers in competitive markets determine prices in a process that ensures the most efficient allocation of resources, but some government programs interfere with competitive markets. In both health care and education, government subsidies to reduce out-of-pocket expenses have created a "third-party payer" problem. When individuals use other people's money, they become less concerned about price. This undermines the critical role of competitive markets, causing significant inefficiency in sectors such as health care and education. Government programs also lead to resource misallocation because individuals, organizations, and companies spend time, energy, and money seeking either to obtain special government favors or to minimize their share of the cost of government.

- The inefficiency cost. Government spending is a less effective way to deliver services. Government directly provides many services and activities such as education, airports, and postal operations. However, there is evidence that the private sector could provide these important services at a higher quality and lower cost. In some cases, such as airports and postal services, the improvement would take place because of privatization. In other cases, such as education, the economic benefits would accrue by shifting to a model based on competition and choice.

- The stagnation cost. Government spending inhibits innovation. Because of competition and the desire to increase income and wealth, individuals and entities in the private sector constantly search for new options and opportunities. Economic growth is greatly enhanced by this discovery process of "creative destruction." Government programs, however, are inherently inflexible, both because of centralization and because of bureaucracy. Reducing government-or devolving federal programs to the state and local levels-can eliminate or mitigate this effect.

Spending on a government program, department, or agency can impose more than one of these costs. For instance, all government spending imposes both extraction costs and displacement costs. This does not necessarily mean that outlays-either in the aggregate or for a specific program-are counterproductive. That calculation requires a cost-benefit analysis.

Do deficits Matter?

The Keynesian Controversy. The Economics of government spending is not limited to cost-benefit analysis. There is also the Keynesian debate. In the 1930s, John Maynard Keynes argued that government spending-particularly increases in government spending-boosted growth by injecting purchasing power into the economy. [2] According to Keynes, government could reverse economic downturns by borrowing money from the private sector and then returning the money to the private sector through various spending programs.

This "pump priming" concept did not necessarily mean that government should be big. Instead, Keynesian theory asserted that government spending-especially deficit spending-could provide short-term stimulus to help end a recession or depression. The Keynesians even argued that policymakers should be prepared to reduce government spending once the economy recovered in order to prevent Inflation, which they believed would result from too much economic growth. They even postulated that there was a tradeoff between Inflation and unemployment (the Phillips Curve) and that government officials should increase or decrease government spending to steer the economy between too much of one or too much of the other.

Keynesian economics was very influential for several decades and dominated public policy from the 1930s-1970s. The theory has since fallen out of favor, but it still influences policy discussions, particularly on whether or not changes in government spending have transitory economic effects. For instance, some lawmakers use Keynesian analysis to argue that higher or lower levels of government spending will stimulate or dampen economic growth.

The "Deficit Hawk" Argument. Another related policy issue is the role of budget deficits. Unlike Keynesians, who argue that budget deficits boost growth by injecting purchasing power into the economy, some economists argue that budget deficits are bad because they allegedly lead to higher interest rates. Since higher interest rates are believed to reduce investment, and because investment is necessary for long-run economic growth, proponents of this view (sometimes called "deficit hawks") assert that avoiding deficits should be the primary goal of fiscal policy.

While deficit hawks and Keynesians have very different views on budget deficits, neither school of thought focuses on the size of government. Keynesians are sometimes associated with bigger government but, as discussed above, have no theoretical objection to small government as long as it can be increased temporarily to jump-start a sluggish economy. By contrast, the deficit hawks are sometimes associated with smaller government but have no theoretical objection to large government as long as it is financed by Taxes rather than borrowing.

The deficit hawk approach to fiscal policy has always played a role in economic policy, but politics sometimes plays a role in its usage. During much of the post-World War II era, Republicans complained about deficits because they disapproved of the spending policies of the Democrats who controlled many of the levers of power. In more recent years, Democrats have complained about deficits because they disapprove of the tax policies of the Republicans who control many of the levers of power. Presumably, many people genuinely care about the impact of deficits, but politicians often use the issue as a proxy when fighting over tax and spending policies in Washington.

The Evidence: Government Spending and Economic Performance

Economic theory is important in providing a framework for understanding how the world works, but evidence helps to determine which economic theory is most accurate. This section reviews global comparisons and academic research to ascertain whether government spending helps or hinders economic performance.

Worldwide Experience. Comparisons between countries help to illustrate the impact of public policy. One of the best indicators is the comparative performance of the United States and Europe. The "old Europe" countries that belong to the European Union tend to have much bigger governments than the United States. While there are a few exceptions, such as Ireland, many European governments have extremely large welfare states.

As Chart 1 illustrates, government spending consumes almost half of Europe's economic output-a full one-third higher than the burden of government in the U.S. Not surprisingly, a large government sector is associated with a higher tax burden and more government debt. Bigger government is also associated with sub-par economic performance. Among the more startling comparisons:

- Per capita economic output in the U.S. in 2003 was $37,600-more than 40 percent higher than the $26,600 average for EU-15 nations. [3]

- Real economic growth in the U.S. over the past 10 years (3.2 percent average annual growth) has been more than 50 percent faster than EU-15 growth during the same period (2.1 percent). [4]

- The U.S. unemployment rate is significantly lower than the EU-15 unemployment rate, and there is a stunning gap in the percentage of unemployed who have been without a job for more than 12 months-11.8 percent in the U.S. versus 41.9 percent in EU-15 nations. [5]

- Living standards in the EU are equivalent to living standards in the poorest American states-roughly equal to Arkansas and Montana and only slightly ahead of West Virginia and Mississippi, the two poorest states. [6]

Blaming excessive spending for all of Europe's economic problems would be wrong. Many other policy variables affect economic performance. For instance, over-regulated labor markets probably contribute to the high unemployment rates in Europe. Anemic growth rates may be a consequence of high tax rates rather than government spending. Yet, even with these caveats, there is a correlation between bigger government and diminished economic performance.

The Academic Research. Even in the United States, there is good reason to believe that government is too large. Scholarly research indicates that America is on the downward sloping portion of the Rahn Curve -- as are most other industrialized nations. In other words, policymakers could enhance economic performance by reducing the size and scope of government. The supplement to this paper includes a comprehensive review of the academic literature and a discussion of some of the methodological issues and challenges. This section provides an excerpt of the literature review and summarizes the findings of some of the major economic studies.

The academic literature certainly does not provide all of the answers. Isolating the precise effects of one type of government policy-such as government spending-on aggregate economic performance is probably impossible. Moreover, the relationship between government spending and economic growth may depend on factors that can change over time.

Other important methodological issues include whether the model assumes a closed economy or allows international flows of capital and labor. Does it measure the aggregate burden of government or the sum of the component parts? These are all critical questions, and the answers help drive the results of various studies.

The effort is further complicated by the challenge of identifying the precise impact of government spending:

- Does spending hinder economic performance because of the Taxes used to finance government?

- Would the economic damage be reduced if government had some magical source of free revenue?

- How do academic researchers measure the adverse economic impact of government consumption spending versus government infrastructure spending?

- Is there a difference between military and domestic spending or between purchases and transfers?

There are no "correct" answers to these questions, but the growing consensus in the academic literature is persuasive. Regardless of the methodology or model, government spending appears to be associated with weaker economic performance. For instance:

- A European Commission report acknowledged: "[B]udgetary consolidation has a positive impact on output in the medium run if it takes place in the form of expenditure retrenchment rather than tax increases." [7]

- The IMF agreed: "This tax induced distortion in economic behavior results in a net efficiency loss to the whole economy, commonly referred to as the 'excess burden of taxation,' even if the government engages in exactly the same activities-and with the same degree of efficiency-as the private sector with the tax revenue so raised." [8]

- An article in the Journal of Monetary Economics found: "[T]here is substantial crowding out of private spending by government spending.…[P]ermanent changes in government spending lead to a negative wealth effect." [9]

- A study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas also noted: "[G]rowth in government stunts general economic growth. Increases in government spending or Taxes lead to persistent decreases in the rate of job growth." [10]

- An article in the European Journal of Political Economy found: "We find a tendency towards a more robust negative growth effect of large public expenditures." [11]

- A study in Public Finance Review reported: "[H]igher total government expenditure, no matter how financed, is associated with a lower growth rate of real per capita gross state product." [12]

- An article in the Quarterly Journal of Economics reported: "[T]he ratio of real government consumption expenditure to real GDP had a negative association with growth and investment," and "Growth is inversely related to the share of government consumption in GDP, but insignificantly related to the share of public investment." [13]

- A study in the European Economic Review reported: "The estimated effects of GEXP [government expenditure variable] are also somewhat larger, implying that an increase in the expenditure ratio by 10 percent of GDP is associated with an annual growth rate that is 0.7-0.8 percentage points lower." [14]

- A Public Choice study reported: "[A]n increase in GTOT [total government spending] by 10 percentage points would decrease the growth rate of TFP [total factor productivity] by 0.92 percent [per annum]. A commensurate increase of GC [government consumption spending] would lower the TFP growth rate by 1.4 percent [per annum]." [15]

- An article in the Journal of Development Economics on the benefits of international capital flows found that government consumption of economic output was associated with slower growth, with coefficients ranging from 0.0602 to 0.0945 in four different regressions. [16]

- A Journal of Macroeconomics study discovered: "[T]he coefficient of the additive terms of the government-size variable indicates that a 1% increase in government size decreases the rate of economic growth by 0.143%." [17]

- A study in Public Choice reported: "[A] one percent increase in government spending as a percent of GDP (from, say, 30 to 31%) would raisethe unemployment rate by approximately .36 of one percent (from, say, 8 to 8.36 percent)." [18]

- A study from the Journal of Monetary Economics stated: "We also find a strong negative effect of the growth of government consumption as a fraction of GDP. The coefficient of -0.32 is highly significant and, taken literally, it implies that a one standard deviation increase in government growth reduces average GDP growth by 0.39 percentage points." [19]

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development acknowledged: "Taxes and government expenditures affect growth both directly and indirectly through investment. An increase of about one percentage point in the tax pressure-e.g. two-thirds of what was observed over the past decade in the OECD sample- could be associated with a direct reduction of about 0.3 per cent in output per capita. If the investment effect is taken into account, the overall reduction would be about 0.6-0.7 per cent." [20]

- A National Bureau of Economic Research paper stated: "[A] 10 percent balanced budget increase in government spending and taxation is predicted to reduce output growth by 1.4 percentage points per annum, a number comparable in magnitude to results from the one-sector theoretical models in King and Robello." [21]

- Another National Bureau of Economic Research paper stated: "A reduction by one percentage point in the ratio of primary spending over GDP leads to an increase in investment by 0.16 percentage points of GDP on impact, and a cumulative increase by 0.50 after two years and 0.80 percentage points of GDP after five years. The effect is particularly strong when the spending cut falls on government wages: in response to a cut in the public wage bill by 1 percent of GDP, the figures above become 0.51, 1.83 and 2.77 per cent respectively." [22]

- An IMF article confirmed: "Average growth for the preceding 5-year period…was higher in countries with small governments in both periods. The unemployment rate, the share of the shadow economy, and the number of registered patents suggest that small governments exhibit more regulatory efficiency and have less of an inhibiting effect on the functioning of labor markets, participation in the formal economy, and the innovativeness of the private sector." [23]

- Looking at U.S. evidence from 1929-1986, an article in Public Choice estimated: "This analysis validates the classical supply-side paradigm and shows that maximum productivity growth occurs when government expenditures represent about 20% of GDP." [24]

- An article in Economic Inquiry reported: "The optimal government size is 23 percent (+/-2 percent) for the average country. This number, however, masks important differences across regions: estimated optimal sizes range from 14 percent (+/-4 percent) for the average OECD country to…16 percent (+/-6 percent) in North America." [25]

- A Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland study reported: "A simulation in which government expenditures increased permanents from 13.7 to 22.1 percent of GNP (as they did over the past four decades) led to a long-run decline in output of 2.1 percent. This number is a benchmark estimate of the effect on output because of permanently higher government consumption." [26]

Spending Control Success Stories

Both economic theory and empirical evidence suggest that government should be smaller. Yet is it possible to translate good economics into public policy? Even though many policymakers understand that government spending undermines economic performance, some think that special-interest groups are too politically powerful and that reducing the size of government is an impossible task. Since the burden of government has relentlessly increased during the post- World War II era, this is a reasonable assumption.

Moreover, there is a concern that the transition to smaller government may be economically harmful. In other words, the economy may be stronger in the long run if the burden of government is reduced, but the short-run consequences of spending reductions could make such a change untenable. This Keynesian analysis is much less prevalent today than it was 30 years ago, but it is still part of the debate.

There are examples of nations that have successfully reduced the burden of government during peacetime. [27] They show that it is possible to reduce government spending-sometimes by dramatic amounts. In all of these examples, policymakers enjoyed political and economic success. For instance:

- Ronald Reagan dramatically reversed the direction of public policy in the United States. Government-especially domestic spending-was growing rapidly when he took office. Measured as a share of national output, President Reagan reduced domestic discretionary spending by almost 33 percent, down from 4.5 percent of GDP in 1981 to 3.1 percent of GDP in 1989.

Reagan's track record on entitlements was also impressive. When he took office, entitlement spending was on a sharp upward trajectory, peaking at 11.6 percent of GDP in 1983. By the time he left office, entitlement spending consumed 9.8 percent of economic output.

As a result of these dramatic improvements, Reagan was able to reduce the total burden of government spending as a share of economic output during his presidency while still restoring the nation's military strength. [28] Table 1 shows Reagan's impressive performance compared to other Presidents, measured by the real (inflation-adjusted) growth of federal spending.

- Bill Clinton was surprisingly successful in controlling the burden of government, particularly during his first term. His record was greatly inferior to Ronald Reagan's, and some of the credit probably belongs to the Republicans in Congress, but Clinton managed to preside over the second most frugal record of any President in the post-World War II era. Domestic discretionary spending fell from 3.4 percent of GDP to 3.1 percent of GDP, and entitlement spending dropped from 10.8 percent of GDP to 10.5 percent of GDP. [29]

These were modest reductions compared to Ronald Reagan, and many of them evaporated during Clinton's second term once a budget surplus materialized and undermined fiscal discipline. Nonetheless, when combined with reasonable economic growth and the "peace dividend" made possible by President Reagan's victory in the Cold War, the total burden of federal spending fell as low as 18.4 percent of GDP in 2000, the lowest level since 1966. [30]

- Ireland has dramatically changed its fiscal policy in the past 20 years. In the 1980s, government spending consumed more than 50 percent of economic output, and high tax rates penalized productive behavior. This led to economic stagnation, and Ireland became known as the "sick man of Europe." However, the government decided to act. As one economist explained, "After a stagnant 13-year period with less than 2 percent growth, Ireland took a more radical course of slashing expenditures, abolishing agencies and toppling tax rates and regulations." [31]

The reductions in government were especially impressive. A Joint Economic Committee report explained: "This situation was reversed during the 1987-96 period. As a share of GDP, government expenditures declined from the 52.3 percent level of 1986 to 37.7 percent in 1996, a reduction of 14.6 percentage points." [32] As Chart 2 illustrates, Ireland has been able to keep government from creeping back in the wrong direction. Little wonder that a writer for the Financial Post wrote that "Ireland's biggest export was people until the country adopted enlightened trade, tax and education policies. Now it is the Celtic Tiger." [33]

- New Zealand has an equally impressive record of fiscal rejuvenation. Government spending has plunged from more than 50 percent of GDP to less than 40 percent of economic output. One former government minister justifiably bragged:

When we started this process with the Department of Trans-portation, it had 5,600 employees. When we finished, it had 53. When we started with the Forest Service, it had 17,000 employees. When we finished, it had 17. When we applied it to the Ministry of Works, it had 28,000 employees. I used to be Minister of Works, and ended up being the only employee.… We achieved an overall reduction of 66 percent in the size of government, measured by the number of employees. [34]

It is especially amazing that New Zealand was able to accomplish so much is such a short period of time. In the first half of the 1990s, "Real spending per capita fell by 12 percent." [35] This fiscal reform, combined with other free-market policies, helped New Zealand recover from economic stagnation.

- Slovakia is a more recent success story, but it may prove to be the most dramatic. After suffering from decades of communist oppression and socialist mismanagement, Slovakia is becoming the Hong Kong of Europe. With a 19 percent flat tax and a private social security system, Slovak leaders have charted a bold course that includes significant reductions in the burden of government. As Chart 3 demonstrates, government spending has plummeted in just seven years from 65 percent of GDP to 43 percent of GDP.

Policymakers in the United States should seek to replicate these successes. A smaller government will lead to better economic performance, and it also is the only pro-growth way to deal with the politically sensitive issue of budget deficits.

Even a modest degree of discipline can quickly generate a balanced budget. As Chart 4 illustrates, a spending freeze balances the budget in two to three years, and limiting the growth of spending to the rate of Inflation balances the budget in four to five years. Even if spending is allowed to grow by 4 percent each year, the budget deficit quickly shrinks-even if the Bush tax cuts are made permanent.

Other Economic Policy Choices Matter

The size of government has a major impact on economic performance, but it is just one of many important variables. The Index of Economic Freedom , published annually by The Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal , thoroughly examines the factors that are correlated with prosperity, finding that the following policy choices also have important effects independent of the level of government spending:

- Tax Policy. The tax system has a pronounced impact on economic performance. For instance, the federal tax burden in the U.S. is about 17 percent of GDP, which is less than the aggregate tax burden in Hong Kong. Yet, since Hong Kong has a low-rate flat tax that generally does not penalize saving and investment, it raises revenue in a much less destructive manner. Similarly, the current U.S. tax system raises about the same level of revenue as it did 25 years ago, but the associated economic costs are lower because marginal tax rates have been reduced on work, saving, investment, and entrepreneurship.

- Monetary Policy. The monetary regime will help or hinder a nation's economy. Inflation can quickly destroy economic confidence and cripple investment. By contrast, a stable monetary system provides an environment that is conducive to economic activity.

- Trade Policy. A nation's openness to trade exerts a powerful impact on economic prosperity. Governments that restrict trade with protectionist policies saddle their nations with high costs and economic inefficiencies. Conversely, free trade improves economic efficiency and boosts living standards.

- Regulatory Policy. Bureaucracy and red tape have a considerable effect on a country's economy. Deregulated markets encourage the efficient allocation of resources since decisions are based on economic factors. Excessive regulation, by contrast, can result in needlessly high costs and inefficient behavior.

- Private Property. Independent of the level of government spending, the presence of private property rights plays a crucial role in an economy's performance. If government owns or controls resources, political forces are likely to dominate economic forces in determining how those resources are allocated. Likewise, if private property is not secured by both tradition and law, owners will be less likely to utilize resources efficiently. In other words, for any particular level of government spending, the security of private property rights will have a strong effect on economic performance.

These five factors are certainly not an exhaustive list. Other factors that determine a nation's economic performance include the level of corruption, openness of capital markets, competitiveness of financial system, and flexibility of prices. The 2005 Index of Economic Freedom contains a thorough analysis of the role of all these factors in promoting economic growth. [36]

Government spending should be significantly reduced. It has grown far too quickly in recent years, and most of the new spending is for purposes other than homeland security and national defense. Combined with rising entitlement costs associated with the looming retirement of the baby-boom generation, America is heading in the wrong direction. To avoid becoming an uncompetitive European-style welfare state like France or Germany, the United States must adopt a responsible fiscal policy based on smaller government.

Budgetary restraint should be viewed as an opportunity to make an economic virtue out of fiscal necessity. Simply stated, most government spending has a negative economic impact. To be sure, if government spends money in a productive way that generates a sufficiently high rate of return, the economy will benefit, but this is the exception rather than the rule. If the rate of return is below that of the private sector-as is much more common-then the growth rate will be slower than it otherwise would have been. There is overwhelming evidence that government spending is too high and that America's economy could grow much faster if the burden of government was reduced.

The deficit is not the critical variable. The key is the size of government, not how it is financed. Taxes and deficits are both harmful, but the real problem is that government is taking money from the private sector and spending it in ways that are often counterproductive. The need to reduce spending would still exist-and be just as compelling-if the federal government had a budget surplus. Fiscal policy should focus on reducing the level of government spending, with particular emphasis on those programs that yield the lowest benefits and/or impose the highest costs.

Controlling federal spending is particularly important because of globalization. Today, it is becoming increasingly easy for jobs and capital to migrate from one nation to another. This means that the reward for good policy is greater than ever before, but it also means that the penalty for bad policy is greater than ever before.

This may be cause for optimism. A study published by the IMF, which certainly is not a free-market institution, has stated:

As the international economy becomes more competitive, and as capital and labor become more mobile, countries with big and especially inefficient governments risk falling behind in terms of growth and welfare. When voters and industries realize the long-term benefits of reform in such an environment, they and their representatives may push their governments toward reform. In these circumstances, policymakers find it easier to overcome the resistance of special-interest groups. [37]

For most of America's history, the aggregate burden of government was below 10 percent of GDP. [38] This level of government was consistent with the beliefs of the America's founders. As the IMF has explained, "classical economists and political philosophers generally advocated the minimal state-they saw the government's role as limited to national defense, police, and administration." [39] America's policy of limited government certainly was conducive to economic expansion. In the days before income tax and excessive government, America moved from agricultural poverty to middle-class prosperity.

Reducing government to 10 percent of GDP might be a very optimistic target, but shrinking the size of government should be a major goal for policymakers. The economy certainly would perform better, and this would boost prosperity and make America more competitive.

Daniel J. Mitchell, Ph.D. , is McKenna Senior Research Fellow in the Thomas A. Roe Institute for Economic Policy Studies at The Heritage Foundation.

[1] Daniel J. Mitchell, "Academic Evidence: A Growing Consensus Against Big Government," supplement to Daniel J. Mitchell, "The Impact of Government Spending on Economic Growth," Heritage Foundation Backgrounder No. 1831, at www.heritage.org/research/budget/bg1831_suppl.cfm . The supplement is available only on the Web. [2] John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936), in The General Theory , Vol. 7 of Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes , ed. Donald Moggridge (London: Macmillan for the Royal Economic Society, 1973), at cepa.newschool.edu/het/essays/keynes/gtcont.htm (February 2, 2005).

[3] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD in Figures , 2004 ed. (Paris: OECD Publications, 2004), at www1.oecd.org/publications/e-book/0104071E.pdf (February 2, 2005). The EU-15 are the 15 member states of the European Union prior to enlargement in 2004: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

[6] Fredrik Bergström and Robert Gidehag, "EU Versus USA," Timbro , June 2004, at www.timbro.com/euvsusa/pdf/EU_vs_USA_English.pdf (February 2, 2005).

[7] European Commission, Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs, "Public Finances in EMU, 2003," European Economy , No. 3, 2003, at e uropa.eu.int/comm/economy_finance/publications/european_economy/2003/ ee303en.pdf (February 2, 2005).

[8] Vito Tanzi and Howell H. Zee, "Fiscal Policy and Long-Run Growth," International Monetary Fund Staff Papers , Vol. 44, No. 2 (June 1997), p. 5.

[9] Shaghil Ahmed, "Temporary and Permanent Government Spending in an Open Economy," Journal of Monetary Economics , Vol. 17, No. 2 (March 1986), pp. 197-224.

[10] Dong Fu, Lori L. Taylor, and Mine K. Yücel, "Fiscal Policy and Growth," Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Working Paper 0301, January 2003, p. 10.

[11] Stefan Fölster and Magnus Henrekson, "Growth and the Public Sector: A Critique of the Critics," European Journal of Political Economy , Vol. 15, No. 2 (June 1999), pp. 337-358.

[12] S. M. Miller and F. S. Russek, "Fiscal Structures and Economic Growth at the State and Local Level," Public Finance Review , Vol. 25, No. 2 (March 1997).

[13] Robert J. Barro, "Economic Growth in a Cross Section of Countries," Quarterly Journal of Economics , Vol. 106, No. 2 (May, 1991), p. 407.

[14] Stefan Fölster and Magnus Henrekson, "Growth Effects of Government Expenditure and Taxation in Rich Countries," European Economic Review , Vol. 45, No. 8 (August 2001), pp. 1501-1520.

[15] P. Hansson and M. Henrekson, "A New Framework for Testing the Effect of Government Spending on Growth and Productivity," Public Choice , Vol.81 (1994), pp. 381-401.

[16] Jong-Wha Lee, "Capital Goods Imports and Long-Run Growth," Journal of Development Economics , Vol. 48, No. 1 (October 1995), pp. 91-110.

[17] James S. Guseh, "Government Size and Economic Growth in Developing Countries: A Political-Economy Framework," Journal of Macroeconomics , Vol. 19, No. 1 (Winter 1997), pp. 175-192.

[18] Burton Abrams, "The Effect of Government Size on the Unemployment Rate," Public Choice , Vol. 99 (June 1999), pp. 3-4.

[19] Kevin B. Grier and Gordon Tullock, "An Empirical Analysis of Cross-National Economic Growth, 1951-80," Journal of Monetary Economics , Vol. 24, No. 2 (September 1989), pp. 259-276.

[20] Andrea Bassanini and Stefano Scarpetta, "The Driving Forces of Economic Growth: Panel Data Evidence for the OECD Countries," Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Economic Studies No. 33, February 2002, at www.oecd.org/dataoecd/26/2/18450995.pdf (February 2, 2005).

[21] Eric M. Engen and Jonathan Skinner, "Fiscal Policy and Economic Growth," National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 4223, 1992, p. 4.

[22] Alberto Alesina, Silvia Ardagna, Roberto Perotti, and Fabio Schiantarelli, "Fiscal Policy, Profits, and Investment," National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 7207, July 1999, p. 4.

[23] Vito Tanzi and Ludger Shuknecht, "Reforming Government in Industrial Countries," International Monetary Fund Finance & Development , September 1996, at www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/1996/09/pdf/tanzi.pdf (February 2, 2005).

[24] E. A. Peden , "Productivity in the United States and Its Relationship to Government Activity: An Analysis of 57 Years, 1929-1986," Public Choice , Vol. 69 (1991), pp. 153-173.

[25] Georgios Karras, "The Optimal Government Size: Further International Evidence on the Productivity of Government Services," Economic Inquiry , Vol. 34, (April 1996), p. 2.

[26] Charles T. Carlstrom and Jagadeesh Gokhale, "Government Consumption, Taxation, and Economic Activity," Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Economic Review , 3rd Quarter, 1991, p. 28.

[27] Spending reductions following a war are quite common but tend not to be very instructive since government is almost always bigger after a war than it was before hostilities began.

[28] Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2005: Historical Tables (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2004), p. 128, Table 8.4, at www.gpoaccess.gov/usbudget/fy05/pdf/hist.pdf (February 2, 2005).

[30] Ibid. , p. 23, Table 1.2.

[31] Benjamin Powell, "Markets Created a Pot of Gold in Ireland," Cato Institute Daily Commentary , April 21, 2003, at www.cato.org/dailys/04-21-03.html (February 2, 2005). This article was previously published by Fox News on April 15, 2003.

[32] James Gwartney, Robert Lawson, and Randall Holcombe, The Size and Functions of Government and Economic Growth , Joint Economic Committee, U.S. Congress, April 1998, p. 20, at www.house.gov/jec/growth/function/function.pdf (February 2, 2005).

[33] Diane Francis, "Ireland Shows Its Stripes," Financial Post , October 9, 2003.

[34] Maurice McTigue, "Rolling Back Government: Lessons from New Zealand," Imprimis , April 2004, at www.hillsdale.edu/newimprimis/2004/april/default.htm (February 2, 2005).

[35] Bryce Wilkinson, "Restraining Leviathan: A Review of the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1994," New Zealand Business Roundtable, November 2004, a www.nzbr.org.nz/documents/publications/publications-2004/restraining_leviathan.pdf (February 2, 2005).

[36] Marc A. Miles, Edwin J. Feulner, and Mary Anastasia O'Grady, 2005 Index of Economic Freedom (Washington, D.C.: The Heritage Foundation and Dow Jones & Company, Inc., 2005).

[37] Tanzi and Shuknecht, "Reforming Government in Industrial Countries."

[38] See U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1975).

[39] Tanzi and Shuknecht, "Reforming Government in Industrial Countries."

Former McKenna Senior Fellow in Political Economy

Federal spending has grown rapidly over the last decade, leading to substantial budget deficits that have crippled the economy and financially harmed Americans.

Learn more about policies that rein in spending and strengthen the economy with Solutions .

COMMENTARY 3 min read

Subscribe to email updates

© 2024, The Heritage Foundation

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Can J Public Health

- v.112(2); 2021 Apr

Language: English | French

With great inequality comes great responsibility: the role of government spending on population health in the presence of changing income distributions

Department of Community Health & Epidemiology, Dalhousie University, 100 Tucker Park Road, Saint John, NB E2K 5E2 Canada

Daniel J. Dutton

To determine the association between provincial government health and social spending and population health outcomes in Canada, separately for men and women, and account for the potential role of income inequality in modifying the association.

We used data for nine Canadian provinces, 1981 to 2017. Health outcomes and demographic data are from Statistics Canada; provincial spending data are from provincial public accounts. We model the ratio of social-to-health spending (“the ratio”) on potentially avoidable mortality (PAM), life expectancy (LE), potential years of life lost (PYLL), infant mortality, and low birth weight baby incidence. We interact the ratio with the Gini coefficient to allow for income inequality modification.

When the Gini coefficient is equal to its average (0.294), the ratio is associated with desirable health outcomes for adult men and women. For example, among women, a 1% increase in the ratio is associated with a 0.04% decrease in PAM, a 0.05% decrease in PYLL, and a 0.002% increase in LE. When the Gini coefficient is 0.02 higher than average, the relationship between the ratio and outcomes is twice as strong as when the Gini is at its average, other than for PAM for women. Infant-related outcomes do not have a statistically significant association with the ratio.

Overall, outcomes for men and women have similar associations with the ratio. Inequality increases the return to social spending, implying that those who benefit the most from social spending reap higher benefits during periods of higher inequality.

Résumé

Déterminer l’association entre les dépenses sociales et de santé du gouvernement provincial et les conditions de santé de la population du Canada, séparément pour hommes et femmes, et expliquer le role que l’inégalité salariale pourrait jouer dans la modification de cette association.

Méthodes

Nous avons utilisé les données pour neuf provinces canadiennes, de 1981 à 2017. Les conditions de santé et les données démographiques parviennent de Statistiques Canada, les données sur les dépenses provinciales parviennent de comptes publiques provinciaux. Nous avons modélisé le rapport de dépenses social-à-santé (« le rapport ») sur la mortalité potentiellement évitable (MPE), l’espérance de vie (EV), les années de vie potentielles perdues (AVPP), la mortalité d’enfant et l’incidence d’un poids à la naissance faible. Nous interagissons le rapport avec le coefficient de Gini pour permettre la modification d’inégalité salariale.

Résultats