About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Stanford Innovation and Entrepreneurship Certificate

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets & Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Social Impact

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Get Involved

- Reading Materials

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

The Knowledge Economy

We define the knowledge economy as production and services based on knowledge-intensive activities that contribute to an accelerated pace of technical and scientific advance, as well as rapid obsolescence. The key component of a knowledge economy is a greater reliance on intellectual capabilities than on physical inputs or natural resources. We provide evidence drawn from patent data to document an upsurge in knowledge production and show that this expansion is driven by the emergence of new industries. We then review the contentious literature that assesses whether recent technological advances have raised productivity. We examine the debate over whether new forms of work that embody technological change have generated more worker autonomy or greater managerial control. Finally, we assess the distributional consequences of a knowledge-based economy with respect to growing inequality in wages and high-quality jobs.

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Dean’s Remarks

- Keynote Address

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Firsthand (Vault)

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is the Knowledge Economy?

- Knowledge and Human Capital

- Knowledge Economy FAQs

What Is the Knowledge Economy? Definition, Criteria, and Example

Adam Hayes, Ph.D., CFA, is a financial writer with 15+ years Wall Street experience as a derivatives trader. Besides his extensive derivative trading expertise, Adam is an expert in economics and behavioral finance. Adam received his master's in economics from The New School for Social Research and his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in sociology. He is a CFA charterholder as well as holding FINRA Series 7, 55 & 63 licenses. He currently researches and teaches economic sociology and the social studies of finance at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/adam_hayes-5bfc262a46e0fb005118b414.jpg)

The knowledge economy is a system of consumption and production that is based on intellectual capital . In particular, it refers to the ability to capitalize on scientific discoveries and applied research.

The knowledge economy represents a large share of the activity in most highly developed economies . In a knowledge economy, a significant component of value may consist of intangible assets such as the value of its workers' knowledge or intellectual property.

Key Takeaways

- The knowledge economy describes the contemporary commercialization of science and academic scholarship.

- In the knowledge economy, innovation based on research is commodified via patents and other forms of intellectual property.

- The knowledge economy lies at the intersection of private entrepreneurship, academia, and government-sponsored research.

- Knowledge-related industries represent a large share of the activity in most highly developed countries.

- A knowledge economy depends on skilled labor and education, strong communications networks, and institutional structures that incentivize innovation.

Understanding the Knowledge Economy

Developing economies tend to be heavily focused on agriculture and manufacturing, while highly developed countries have a larger share of service-related activities. This includes knowledge-based economic activities such as research, technical support, and consulting.

The knowledge economy is the marketplace for the production and sale of scientific and engineering discoveries. This knowledge can be commodified in the form of patents or other intellectual property protections. The producers of such information, such as scientific experts and research labs, are also considered part of the knowledge economy.

The Bayh-Dole Act of 1980 was a major turning point in the treatment of intellectual property in the U.S. because it allowed universities to retain title to inventions or discoveries made with federal R&D funding and to negotiate exclusive licenses.

Thanks to globalization, the world economy has become more knowledge-based, bringing with it the best practices from each country's economy. Also, knowledge-based factors create an interconnected and global economy where human expertise and trade secrets are considered important economic resources.

However, it is important to note that generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) do not allow companies to include these assets on their balance sheets.

The modern commercialization of academic research and basic science has its roots in governments seeking military advantage.

Knowledge Economy and Human Capital

The knowledge economy addresses how education and knowledge—that is, " human capital "— can serve as a productive asset or business product to be sold and exported to yield profits for individuals, businesses, and the economy.

This component of the economy relies greatly on intellectual capabilities instead of natural resources or physical contributions. In the knowledge economy, products, and services that are based on intellectual expertise advance technical and scientific fields, encouraging innovation in the economy as a whole.

The World Bank defines knowledge economies according to four pillars:

- Institutional structures that provide incentives for entrepreneurship and the use of knowledge

- Availability of skilled labor and a good education system

- Access to information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructures

- A vibrant innovation landscape that includes academia, the private sector, and civil society.

Example of a Knowledge Economy

Academic institutions, companies engaging in research and development (R&D), programmers developing new software and search engines for data, and health workers using digital data to improve treatments are all components of a knowledge economy.

These economy brokers pass on the results of their research to workers in more traditional fields, such as farmers who use software applications and digital solutions to manage their crops better, advanced technological-based medical procedures such as robot-assistant surgeries, or schools that provide digital study aids and online courses for students.

How Big Is the Knowledge Economy?

Because it is not a clearly-defined category such as manufacturing, it is difficult to put an exact price tag on the global knowledge economy. However, it is possible to gain a rough estimate by gauging some of the major components of the knowledge economy. In the United States, the total intellectual property market is worth $6.6 trillion, according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, and IP-intensive industries account for over a third of GDP. The market size of the country's higher education institutions accounts for an additional $568 billion.

What Are the Most Valuable Skills in the Knowledge Economy?

While higher education and technical training are obvious assets, communication and teamwork are also essential skills for a knowledge-based economy, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development . Since it is unlikely that any single knowledge worker can generate groundbreaking innovations alone, these interpersonal and workplace competencies are essential to surviving in a knowledge-based workplace.

Which Country Has the Biggest Knowledge Economy?

The factors of a knowledge economy are measured by the United Nations Development Program's Global Knowledge Index, which replaced the World Bank Knowledge Economy Index after 2012. This metric scores each country based on "enabling factors" for the knowledge economy, such as education levels, technical and vocational training, innovation, and communications technology. According to the latest issue, Switzerland is the top-ranked knowledge economy with a total score of 71.5%. The next two are Sweden and the United States with scores of 70.0 each.

GovTrack. " H.R. 6933 (96th): Government Patent Policy Act of 1980 ."

The World Bank. " The Knowledge Economy, The Kam Methodology, and World Bank Operations ," Pages 5-8.

Ibis World. " Colleges and Universities in the US ."

Global Innovation Policy Center. " Why Is IP Important ?"

OECD. " Competencies for the Knowledge Economy ," Page 1.

Knoema. " Global Knowledge Index ."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/investing2-5bfc2b8fc9e77c005143f176.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

Articles on Knowledge economy

Displaying all articles.

Encyclopedia Britannica once published a catalogue of humanity’s ‘102 Great Ideas’ – and it created more questions than answers

Mike Ryder , Lancaster University

Jobs deficit drives army of daily commuters out of Western Sydney

Phillip O'Neill , Western Sydney University

As big cities get even bigger, some residents are being left behind

Sajeda Tuli , University of Canberra and Shakil Bin Kashem , University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Digital training can help supervisors lift PhD output

Jan Botha , Stellenbosch University ; Gabriele Vilyte , Stellenbosch University , and Miné de Klerk , Stellenbosch University

New creatives are remaking Canberra’s city centre, but at a social cost

Richard Hu , University of Canberra and Sajeda Tuli , University of Canberra

What it takes for Indonesia to create, share and use knowledge to grow its economy

Arnaldo Pellini , Tampere University

How the SKA telescope is boosting South Africa’s knowledge economy

Nishana Bhogal , University of Cape Town

Science in Africa: homegrown solutions and talent must come first

Alan Christoffels , University of the Western Cape

Why big projects like the Adani coal mine won’t transform regional Queensland

John Cole , University of Southern Queensland

Why openness, not technology alone, must be the heart of the digital economy

Rufus Pollock , University of Cambridge

The Knowledge City Index: Sydney takes top spot but Canberra punches above its weight

Lawrence Pratchett , University of Canberra ; Michael James Walsh , University of Canberra ; Richard Hu , University of Canberra , and Sajeda Tuli , University of Canberra

How access to knowledge can help universal health coverage become a reality

Stevan Bruijns , University of Cape Town

From ‘white flight’ to ‘bright flight’ – the looming risk for our growing cities

Jason Twill , University of Technology Sydney

When ‘innovation’ fails to fix our finances

Usman W. Chohan , UNSW Sydney

Queensland’s budget puts it back on track to be a smart state

Chris Salisbury , The University of Queensland

Budget week reveals an appetite for government but not to govern

Travers McLeod , The University of Melbourne

Measuring the value of science: it’s not always about the money

Rod Lamberts , Australian National University

The East-West Link is dead – a victory for 21st-century thinking

Peter Newman , Curtin University

African Americans place a great value in postsecondary education

Kinder Institute

Related Topics

- Cities & Policy

- Developing a knowledge economy

- Global perspectives

- Knowledge workers

- South Africa

- Tony Abbott

- Urban planning

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Data and Reporting Analyst

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

Top contributors.

Fulbright Scholar, Institute for Governance and Policy Analysis, University of Canberra

Professor, University of Canberra

Pro Vice-Chancellor (Engagement), University of Southern Queensland

Honorary Fellow in the School of Social and Political Sciences, The University of Melbourne

Innovation Fellow and Senior Lecturer, School of Architecture, University of Technology Sydney

Professor, Centre for Research on Evaluation, Science and Technology (CREST), Stellenbosch University

Director, Centre for Western Sydney, Western Sydney University

Lecturer, The University of Queensland

Associate Professor in Social Sciences, University of Canberra

Economist, UNSW Sydney

Dean of Business, Government and Law, University of Canberra

Senior lecturer in the Division of Emergency Medicine, University of Cape Town

Member of EduKnow Research Group at the University of Tampere (Finland), Tampere University

Associate Fellow, University of Cambridge

Senior Lecturer: Entrepreneurship Stellenbosch Business School, University of Cape Town

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

The Connectedness Knowledge from Investors’ Sentiments, Financial Crises, and Trade Policy: An Economic Perspective

- Mubeen Abdur Rehman

- Saeed Ahmad Sabir

- Haider Mahmood

Sustainable Poverty Reduction in Nigeria: Does Process Innovation Matter?

- Fisayo Fagbemi

- John Oluwasegun Ajibike

Is the Relationship Between Clean/Non-clean Energy Consumption and Economic Growth Time-Varying? Non-parametric Evidence for MENA Region

- Tarek Ghazouani

Managerial Time Orientation, Corporate Resource Allocation, and Firm Resilience

- Xiaolong Wang

- Yanmin Zhao

Immigration, Growth and Unemployment: Panel VAR Evidence From Ε.U. Countries

- Melina Dritsaki

- Chaido Dritsaki

Ownership Structure and Firm Performance: A Comprehensive Review and Empirical Analysis

- Sanjana Bhakar

- Priti Sharma

- Sanjiv Kumar

Exploring Knowledge Dynamics and Change Management in Diverse Corporate Entrepreneurship Ecosystems

- Xiaoxian Zhu

The Attitude and Intention to Purchase Halal Cosmetic Products: A Study of Muslim Consumers in Saudi Arabia

- Abdulwahab S. Shmailan

- Abdullah Abdulmohsen Alfalih

Digital Innovation and Urban Resilience: Lessons from the Yangtze River Delta Region

- Nengjie Pan

Corporation Participation in Poverty Alleviation: A Bibliometric Analysis and Content Review

Cultivation of College Students’ Legal Literacy Under Entrepreneurship from the Perspective of Sustainable Development

- Yuanyuan Xu

Cultivating Entrepreneurial Minds: Unleashing Potential in Pakistan’s Emerging Entrepreneurs Using Structural Equational Modeling

- Ahmad Bilal

- Shahzad Ali

- Sayyed Zaman Haider

Does Demographic Dividend Enhance Economic Complexity: the Mediating Effect of Human Capital, ICT, and Foreign Direct Investment

- Stéphane Mbiankeu Nguea

Unraveling Enterprise Persistent Innovation: Connotation, Research Context and Mechanism

Boundary-Spanning Knowledge Search and Absorptive Capacity in Cooperative Innovation: A Study on Non-Core Firms in the Context of Sustainable Development

- Dongping Yu

- Tongyue Zhao

Convergence and Contrast: An Investigation into the Psychological Attributes of Budding Entrepreneurs

- Parwinder Singh

- Ankita Mishra

Strategic Talent Development in the Knowledge Economy: A Comparative Analysis of Global Practices

Rpa as a challenge beyond technology: self-learning and attitude needed for successful rpa implementation in the workplace.

- José Andrés Gómez Gandía

- Sorin Gavrila Gavrila

- Maria Teresa del Val Núñez

Human Capital, Income Inequality and Energy Demand Nexus in sub-Sahara Africa: Insights from Asymmetric Approach

- Olufemi Gbenga Onatunji

- Olusola Joel Oyeleke

- Rasaki Stephen Dauda

Innovative Approaches to Assessing Urban Space Quality: A Multi-Source Big Data Perspective on Knowledge Dynamics

Knowledge Workers, Innovation Linkages and Knowledge Absorption: An Interactive Mechanism Study

- Zongjun Wang

- Maping Zhang

Radical Change and Dominant Character of Digital Transformation in Artificial Intelligence Entrepreneurship in Less Innovative Economies

- Rafael Palacios Bustamante

- Xochitl Margarita Cruz Pérez

- María del Pilar Escott-Mota

Beauty and Flexible Employment in the Digital Age: The Mediating Role of Social Capital

Entrepreneurship Development as a Tool for Employment Creation, Income Generation, and Poverty Reduction for the Youth and Women

- Abdijabbar Ismail Nor

Effects of People Equity and Entrepreneurial Orientation on Firm Performance: The Mediation Role of Social Capital

- Shabeeb Ahmad Gill

- Salem Handhal Al Marri

Navigating Environmental Governance in China’s Hog Sector: Unraveling the “Race to the Bottom” Phenomenon and Spatial Dynamics

Dynamic Relationship Between Social Factors and Poverty: A Panel Data Analysis of 23 Selected Developing Countries

- Syed Muhammad Muddassir Abbas Naqvi

- Iftikhar Yasin

Digital Integration and Entrepreneurial Success: Examining Causation and Effectuation in Rural South China

- Liebing Cao

Effects of Information and Communication Technologies on Structural Change in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Nzepang Fabrice

- Nguenda Anya Saturnin Bertrand

- Ntieche Adamou

How Digital Technology Reduces Carbon Emissions: From the Perspective of Green Innovation, Industry Upgrading, and Energy Transition

- Jiangang Huang

Connecting Human and Information Resources in the Generation of Competitive Advantage

- Sergio Camisón-Haba

- José Antonio Clemente-Almendros

- Tomás Gonzalez-Cruz

Barriers and Strategies for Digital Marketing and Smart Delivery in Urban Courier Companies in Developing Countries

- Efrain Boom-Cárcamo

- Schneyder Molina-Romero

- María del Mar Restrepo

Discussion on the Relationship Between Chinese Government’s Investment in Health Human Capital and Economic Growth

- Miyeseer Maimaituxun

Dynamic Innovation Collaboration Based on Complex Network Analysis: Evidence from the “Belt and Road” Initiative

- Kangjuan Lyu

Has Digital Financial Inclusion Curbed Carbon Emissions Intensity? Considering Technological Innovation and Green Consumption in China

Enterprise Innovation, Government Subsidies, and Bank Loans: an Empirical Analysis from the Science and Technology Innovation Board of China

- Yongmei Fang

Social Disengagements Among Retired Pensioners

- K. Arockiam

The Dynamics of Digitalization and Urban Development on the Growth of the Economy: A Panel Data Analysis

- Muhammad Noshab Hussain

- Shaohua Yang

Enhancing a Business Recommendation System: Leveraging Blockchain Technology with a Differentiated Scoring Incentive Mechanism

- Zhijian Lan

Knowledge Dynamics in Rural Tourism Supply Chains: Challenges, Innovations, and Cross-Sector Applications

- Wenming Liu

- Jingjing Li

Integration of Informatization and Industrialization and Corporate Innovation: Empirical Evidence from China

- Xinjian Huang

Nexus Between Life Expectancy, Education, Governance, and Carbon Emissions: Contextual Evidence from Carbon Neutrality Dream of the USA

- Suleman Sarwar

- Irum Shahzadi

The Role of Entrepreneurship in Changing the Employment Rate in the European Union

- Dimitrios Komninos

- Zacharias Dermatis

- Christos Papageorgiou

The Inheritance Imperative: A Game-Theoretic Analysis of Reverse Tacit Knowledge Transfer

- Yuhan Zhang

Balancing Innovation and Efficiency: The Impact of Mixed Ownership Reform on Total Factor Productivity in Monopolized and Competitive Industries

- Hongduo Yan

Unpacking Antecedents of Knowledge Management Success: A Key to Firm Performance in the Banking Sector

- Samuel Godadaw Ayinaddis

Addressing Wicked Problems (SDGs) Through Community Colleges: Leveraging Entrepreneurial Leadership for Economic Development Post-COVID

- Samantha Bryant Steidle

- Christopher Glass

- Dale A Henderson

Empowering Rural Revitalization: Unleashing the Potential of E-commerce for Sustainable Industrial Integration

- Yun’an Long

Exploring the Current Landscape of Primary School Physical Education Within the Framework of the New Curriculum Reform: A Quality Evaluation Model Perspective

- Chengquan Li

Communication as a Transmitter of Trust in Healthcare Network During Pandemic

- Agata Kocia

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Grow Your Business

What is the knowledge economy (and why should you care), share this article.

It’s no secret that the economy has changed since the beginning of the pandemic. Closures of brick and mortar businesses, shifts to online work and education, and labour shortages have all contributed to a different world than pre-COVID. But with change comes new opportunities – especially for entrepreneurs.

- What is the knowledge economy?

Where is the knowledge economy going?

- Course creators

Technology companies, agencies, and consultants

- How can you benefit from the knowledge economy?

What is the knowledge economy?

T he knowledge economy is an economic system where the main commodity is knowledge, not physical goods .

This means that instead of only placing value on buying and selling physical products (like shoes or cars), value is also placed on expertise, innovation, discovery, and any other intellectual capital (like IT support, branding, research, or consulting).

The term “knowledge economy” has been around since the late 1950s, but started to become most prominent in the late 1980s to the early 2000s . This knowledge economy was primarily focused on research and technology, with an increased demand for science-based innovation.

One indicator of this emphasis on innovation was the growth of total patents granted by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). In 1981 the USPTO granted 71,114 patents, compared to 187,053 in 2003. Most recently in 2021, 374,006 patents were granted, showing no sign of innovation slowing down into the present.

Today, the knowledge economy is a massive part of the overall global economy with millions of people employed in disciplines such as marketing, customer experience, engineering, design, and education – to name a few. Value is highly placed on intangible assets like brand recognition, software, and patented designs.

The World Bank Institute outlines four pillars that must be present for the knowledge economy to thrive.

1. Institutional structures that provide incentives for entrepreneurship and the use of knowledge

For example, the US government supports small business innovation through the Small Business Innovation Research program . This program supports entrepreneurship and research through monetary grants from $150,000 – $1,000,000. The goal of the program is to stimulate high-tech innovation and help the “United States gain entrepreneurial spirit as it meets its specific research and development needs.”

2. Availability of skilled labor and a good education system

This could mean good universities and school systems, but this definition is changing. There are increasingly online learning options to acquire the necessary skills to join the knowledge economy. For example, creators such as Miss Excel on Thinkific, make learning in-demand skills such as Microsoft Excel accessible from anywhere in the world .

3. An effective innovation system of firms, research centers, universities, consultants, and other organizations

This could be any non-governmental organization that contributes to innovation, like research labs or think tanks. For example, the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) houses 12,200 scientists from 70 countries and is the largest physics laboratory in the world. CERN contributes to innovation globally and created the world’s most powerful particle accelerator in 2018.

4. Access to information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructures

One example that comes to mind here is Google . With Google, people have the means to answer any question at the tip of their fingers through phones, tablets, and computers. They also have the ability to communicate through chat and email. The internet and search engines make access to information infrastructures accessible worldwide.

Currently, more than 70% of patenting and production of scientific and technical papers happens in developed countries. There is clearly a large disparity between developing and developed countries when it comes to the knowledge economy.

But that doesn’t mean developing countries can’t profit from the knowledge economy. With the internet and a multitude of ways to learn and make money online, there is greater opportunity than ever. Entrepreneurs in developing countries can tap into global knowledge to bolster their own success.

That isn’t to say industrial and agricultural economies are going anywhere. We still need cars, shoes, furniture, appliances, and more. And of course, we still need food. But tapping into the knowledge economy is a fantastic way for entrepreneurs to make money – and sometimes help others in the process.

As information becomes more widely available the knowledge economy will keep growing, making this an optimal time to jump in and benefit.

The knowledge economy in action

So we’ve defined what the knowledge economy is, and where it might be headed. But who are knowledge entrepreneurs, and what are they doing?

You’ve probably heard of the biggest companies that operate in the knowledge economy. We previously mentioned Google , but Amazon and Apple are also great examples. All of these companies leverage the knowledge economy to deliver exceptional innovation: from revolutionizing online shopping to virtual assistants Siri, Alexa, and Google Home, to ebooks and digital reading.

But, it’s pretty hard to relate to these massive companies where hundreds of thousands of people are working towards the corporation’s success and innovation. There are many smaller entrepreneurs and companies benefitting from the knowledge economy, and building their own success. Here are a few examples:

Course creators

Tonya Rapley, founder of myfabfinance

Tonya created myfabfinance to teach financial concepts to millennials. She now has an award-winning blog and highly successful financial course masterclass – all stemming from her desire to share knowledge with others. She credits her success with establishing herself as the go-to subject matter expert for finance. Because she demonstrates clear understanding and expertise, her audience and customers place value on that expertise and knowledge as well.

Suzana Somers, founder of BachelorData Academy

Suzana taught herself how to analyze data using the TV show The Bachelor . This fun project led to her creating an Instagram account to share her data analysis. Her account became so popular Suzana decided to launch a data analysis course on Thinkific to share her knowledge. Her course has been featured in publications like Vanity Fair, and she’s helped her students learn data visualization all without any formal training in the area. Because she positioned her knowledge in such a unique way students i mmediately saw the value and were willing to pay for it.

These two entrepreneurs are far from the exception – millions of companies and individuals are finding success within the knowledge economy. Look at fitness studios and yoga instructors switching to teaching online, or photographers and creatives sharing their knowledge through courses and videos.

Part of the growth of knowledge entrepreneurship is the fact that it’s open to anyone; a knowledge entrepreneur doesn’t have to be an expert, a celebrity or have the backing of an established business. They simply have a skill, knowledge, or passion that they want to share as part of creating or scaling a business. – Greg Smith, Co-Founder & CEO, Thinkific

While we know creating online courses is an excellent way to cash in, there are other options too.

Take a look at e-commerce company Shopify . They’ve created a one-stop-shop for selling online, much in the same way Thinkific has created a one-stop-shop for teaching online . Much of Shopify’s success comes from their ability to anticipate customer needs and release features that meet them.

For example, Shopify’s customers needed help marketing their online shops, so Shopify released email marketing and Facebook Ad integrations to make that easier. The company has completely changed e-commerce. Their innovation and technology has made Shopify a market leader, showing the knowledge economy in action.

Agencies that provide consulting, design, or marketing services are also participating in the knowledge economy by selling their expertise to businesses. This could mean anything from helping businesses refine their organizational processes, to designing logos, to creating whole marketing plans.

Another clear example are tech startups that create apps or software. There is value placed on the coding and infrastructure that exists to create the software or application, as well as the brand and idea. These are all products of expertise and innovation – part of the knowledge economy.

These examples are in no way the only options for participating in the knowledge economy. The possibilities are nearly endless when it comes to ways to capitalize.

How you can benefit from the knowledge economy

The knowledge economy benefits people worldwide. More value placed on knowledge = incentive to invent, create, and share knowledge. But how can you personally benefit from the knowledge economy?

Well, it depends on what you want to do.

Read more: Find Your Niche in 5 Simple Steps

A great first step is to assess what you’re interested in and what you’re already knowledgeable about. Good at writing? Sell your skills through a course, or by freelancing on Fiverr or Upwork . Good at cooking? Write an online cookbook, or create videos on how to cook. Maybe you know how to create software and want to teach others how to code, so you start a bootcamp, or you sell a patent to your latest planning software.

Or maybe you’ve successfully run a marathon. There’s a market out there of people looking for tips and tricks on how to start running marathons. Perhaps you start a blog catering to them and monetize it , or maybe you start a running online community where people can ask you questions and help each other.

You get the point. Once you assess what your skill and knowledge set is, you just have to monetize it. A proven first step to do that is creating an online course.

Creating an online course with related products such as ebooks, live lessons, and memberships is a great way to break into the knowledge economy. If you know how to do something successfully, there’s an audience that’s willing to pay for the value your knowledge will bring them.

Why not try it out and join the knowledge economy?

Maddie is a content marketer at Thinkific. When she isn't zealously writing about all things online learning, you can find her glued to a good book or exploring the great outdoors.

- How To Use Webinars To Promote Your Courses (Complete Guide)

- How to Create a Sales Funnel to Sell Online Courses (Sales Funnel Template)

- Udemy’s Pricing Model: How To Use It To Your Advantage As An Online Course Creator

- How to Build a Personal Brand (Complete Guide)

Related Articles

Building your personal brand & audience online (ani alexander interview).

Teach Online TV interview with podcast host & best-selling author Ani Alexander on how to build a strong personal brand and build your audience online.

The 3 Steps To Creating A Powerful Presentation (Julia Wojnar Interview)

Thinkific Teach Online TV interview with public speaking expert Julia Wojnar on the 3 steps to creating a powerful presentation.

How To Host Joint Venture Webinars to Sell More Online Courses

Hosting a webinar with a Joint Venture partner is an effective way to increase your online course sales. In this article, we show you how to do it.

Try Thinkific for yourself!

Accomplish your course creation and student success goals faster with thinkific..

Download this guide and start building your online program!

It is on its way to your inbox

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 03 April 2024

Circular design strategies and economic sustainability of construction projects in china: the mediating role of organizational culture

- You Chen 1 ,

- Xiaomin Yin 2 &

- Chunwei Lyu 3

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 7890 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

39 Accesses

Metrics details

- Energy science and technology

- Engineering

This research aims to elucidate the relationship between circular design strategies (CDS) and the economic sustainability of construction projects (ESCP), examining the mediating role of organizational culture (OC). Motivated by the imperative to develop a sustainable circular economy (CE) model in the building industry, our study focuses on a crucial dimension of CE processes. Specifically, we investigate how construction firms’ organizational values shape their pursuit of desired economic outcomes within CE theory. Through a comprehensive analysis of 359 responses from a cross-sectional survey of Chinese construction firms employing Partial Least Squares-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), our findings reveal a positive albeit weakly impactful association between CDS and ESCP. Simultaneously, OC is identified as a factor detrimental to ESCP. Notably, this study unveils the influential roles of hierarchical culture (HC) and group culture (GC) in shaping the current state of ESCP in China. Emphasizing the significance of CDS, we propose that contract administrators proactively reposition their organizations to adopt strategies conducive to achieving the necessary economic output for construction projects. The originality aspect lies in this research contributes to the existing body of knowledge by offering empirical insights into the theoretical framework, marking the first such empirical study in northern China. We conclude by critically examining research outcomes and limitations while providing insightful recommendations for future research to foster sustainable construction practices in the Chinese context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Analysis of influencing factors for housing construction technology in Desakota Village and town communities in China

Zhixing Li, Xin He, … Yafei Zhao

Design-driven regional industry transformation and upgrading under the perspective of sustainable development

Lisi You, Tie Ji, … Lei Shi

Mechanism of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control influence the green development behavior of construction enterprises

Xingwei Li, Jiachi Dai, … Qiong Shen

Introduction

Current and upcoming trends point to the necessity for a fundamental shift in how resources are used to avoid ecological breakdown and significant interruptions in production 1 . The rate at which the human population grows, accompanied by a growth in the population’s purchasing power, always results in the depletion of additional material resources. Yin et al 2 . discussed how the world’s population is quickly urbanizing, with a 70% urbanization rate expected by 2050. China, one of the fastest-urbanizing countries in Asia, today has nearly half its population living in urban areas 3 , signalling the need for more infrastructure 4 . Linear material use is depleting scarce resources and accumulating global waste problems 5 . Given the costs of extracting, refining, and creating materials, maximizing the material’s value is critical to ensuring that it is kept in circulation (in terms of function and service) for as long as possible. A material flow paradigm, in which the flows are inverse, is more likely to solve the dilemma of an unsustainable universal linear flow economy 6 . The idea of the circular economy (CE) is a growing method that is increasingly frequently explored to overcome the existing quandary of product lifecycles to achieve a more sustainable, workable economic structure. The already prevalent topic of sustainable development, which has captivated worldwide consciousness and execution, bolsters the circularity mentality 7 . Transitioning to a working CE rule necessitates a multi-level transformation that includes technical modernization, new business models, and, most crucially, unwavering stakeholder cooperation 8 .

Policymakers and other stakeholders have recently expressed an interest in developing a circular economy model in the building industry 9 . According to the UK Green Building Council (UKGBC, 2019), CE must be viewed as a commercial strategy, not only a sustainability consideration, if economic opportunities are to be achieved. The building sector consumes 40% of processed timber globally and accounts for 16% of total water energy, yielding 40% of all raw materials and 25% of all resources mined in industrialized countries 10 , 11 . This vital figure highlights the extent to which the building industry is involved in the environment. Construction materials are becoming increasingly scarce in many parts of the world. Shifting to CE and other sustainability-driven business models necessitates a significant transformation that affects the entire construction company and its employees. This shift necessitates creative solutions that replace present systems with ones that are more circular in nature. To identify strategies for organizations to regulate this disruptive transformation, it is necessary to start from within the organization to understand the challenges and barriers they face 12 . Firms’ initiatives to shift to CE are insufficient 9 , 13 . A CE’s essential concept must reach every level of any organization wanting to operate according to its standards for it to be fully implemented 14 . The globally recognized idea of Organizational Culture (OC) of these organizations is at the heart of this argument. The impact of OC on a company’s operations and production has been recognized in the literature for a while now 15 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 . Prior research has shown OC as a background element or social context that impacts a firm’s learning processes in acquiring and applying specialized knowledge 22 .

The construction industry is a pivotal sector in the global economy, especially in rapidly urbanizing nations like China 23 , 24 . As the industry evolves, an increasing emphasis is on integrating sustainable practices to mitigate its environmental impact and promote economic viability. This study delves into the nuanced interplay between Circular Design Strategies (CDS) and the Economic Sustainability of Construction Projects (ESCP) 9 , 25 , with a particular focus on the mediating role of OC in this dynamic. The concept of a circular economy, characterized by reduced waste and continual use of resources, offers a promising pathway to sustainability in the construction sector 22 , 26 . However, the transition to a circular economy involves adopting innovative design strategies and a fundamental shift in the organizational culture within construction firms 19 , 27 .

The primary objective of this research is to unravel the complexities of implementing Circular Design Strategies in the construction industry and their impact on the economic sustainability of projects. We aim to understand how organizational culture influences this relationship, potentially acting as a catalyst or a barrier. By examining the specific context of the Chinese construction industry, this research seeks to contribute valuable insights into how firms can navigate the transition towards a circular economy, highlighting the critical role of organizational values and practices in this transformative journey.

Specifically, the research questions are refined and consolidated into a cohesive inquiry: How do Circular Design Strategies influence the Economic Sustainability of Construction Projects in the Chinese construction industry, and to what extent does Organizational Culture mediate this relationship? This question encapsulates the essence of our investigation, aiming to provide a holistic understanding of the interdependencies between design strategies, economic sustainability, and the underlying organizational ethos within the construction industry in China.

Literature review

Organizational culture in china.

Organizational culture has been defined in various ways, capturing its essence as a set of shared values, beliefs, and assumptions within an organization 2 , 15 , which defined as a set of “values, beliefs and salient assumptions that members of organizations have in common” 3 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 28 , 29 . The earliest specific definition of OC is “a pattern of basic assumptions—invented, discovered, or developed by a given group as it learns to cope with its problems of external adoption and internal integration—that has worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel concerning those problems” 30 .

Organizational culture shapes an organization’s behaviour, practices, and outcomes. Examining corporate culture in China is particularly insightful given its unique historical, social, and economic context, deeply rooted in its rich history, Confucian philosophy, and rapid socio-economic transformations. While the general definition of organizational culture applies, the Chinese context adds cultural nuances, emphasizing collectivism, hierarchy, and the significance of relationships 15 , 16 . Understanding guanxi, the intricate network of personal connections is crucial for grasping the intricacies of organizational dynamics in China 2 , 16 .

The dimensions of organizational culture in China reflect a blend of traditional values and modern influences 4 , 7 , 25 . Collectivism, harmony, and a strong sense of social hierarchy are prominent cultural dimensions, aligning with Confucian principles 17 , 17 , 19 . The influence of these dimensions can be observed in workplace dynamics, decision-making processes, and the emphasis on group cohesion over individual achievement.

Measuring organizational culture in China requires culturally sensitive instruments. The Hofstede Cultural Dimensions Model, with dimensions such as power distance, individualism-collectivism, and uncertainty avoidance, has been adapted to assess organizational culture in the Chinese context 20 , 21 . Additionally, instruments like the Chinese Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument (COCAI) have been developed to capture the unique aspects of organizational culture in Chinese enterprises 15 , 16 , 19 .

Organizational culture significantly influences employee behaviour in Chinese organizations. The emphasis on harmony and group cohesion fosters a collaborative and team-oriented work environment 3 , 15 , 21 . Leadership is crucial, with leaders often embodying Confucian values of benevolence and moral integrity 9 . This cultural backdrop influences Chinese organizations’ communication styles, decision-making processes, and conflict-resolution approaches. That’s the justification for this research selected this aspect to shed light on the mediating role among circular design strategies and economic sustainability of construction projects.

The relationship between organizational culture and performance in China is complex. The emphasis on collective goals can enhance teamwork and employee engagement, positively impacting organizational outcomes 3 , 17 , 18 , 21 . However, challenges arise when traditional cultural values clash with the demands of a rapidly evolving business landscape, requiring organizations to navigate a delicate balance between tradition and modernity 7 , 31 .

Their unique cultural context influences innovation within Chinese organizations. While traditional values may emphasize stability and conformity, there is a growing recognition of the need for innovative thinking 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 . Companies in China are increasingly adopting a more flexible and open organizational culture to encourage creativity and adaptability 33 , 34 , 35 .

Navigating change within Chinese organizations requires understanding the cultural dynamics at play. The cultural preference for stability and respect for authority may challenge rapid organizational transformation 34 . Successful change initiatives often involve aligning corporate culture with innovation and global competitiveness goals, requiring leaders to manage cultural shifts 7 , 31 , 34 .

Generally, every existing organization has its distinct cultural characteristics. In this context, culture refers to how groups, including companies, interact internally and externally. As a result, the cultural coherence of a specific organization is determined by the sufficiency of the group’s artistic mission, strategies, and processes 37 . These cultural techniques are referred to as “macro dimensions,” which are characterized by the dynamic nature of organizations, in which numerous forces interact and impact one another and are thus sensitive to changes that may alter the structure of the organization 37 .

To effectively empirically analyze the effects of OC in line with the stated objectives, this study adopts the Competing Values Framework (CVF) model advanced by Quinn and his co-researchers in the eighties 38 , 36 , 37 , 41 . The CVF is the most recurrently engaged tool in theoretical and experimental studies relating OC to organizational performance 19 and, hence, the most suitable to address CE-related activities. The CVF reveals the multifaceted compositions of OC specifically relating to submission, drive, management, choices and efficacy in an organization 15 .

Additionally, in light of variables that affect Circular Design Strategies (CDS) and Economic Sustainability of Construction Projects in China in the literature review, consider including variables like technological innovation, government regulations, market demand for green building, and supply chain practices. These factors significantly impact the adoption and effectiveness of CDS in contributing to economic sustainability.

In terms of justification for selecting organizational culture as a research variable, it fundamentally shapes how strategies are interpreted, implemented, and integrated within a company’s operations 19 , 38 , 41 . The Competing Values Framework (CVF) provides a multidimensional model to assess organizational culture, making it a robust tool for understanding the cultural underpinnings that influence CDS adoption 39 . Organizational culture affects every aspect of CDS implementation, from decision-making processes to employee engagement and resource allocation. This focus is particularly relevant in the Chinese construction industry, where rapid development and unique cultural factors necessitate a deep understanding of how organizational culture can facilitate or hinder the transition to more sustainable and economically viable construction practices.

Circular design strategies

With the building industry consuming a significant quantity of finite resources, it is critical to use an appropriate structural strategy from the start (design), paying attention to the circularity and reusability of the different materials and components within it. Furthermore, it is critical to concentrate on the packaging that these components are wrapped in; this circularity-by-design approach is essential to creating a zero-waste circular economy in both production and consumption. If the construction industry is an example of how crucial steps of circularity can be achieved through design, then it is critical to plan for reuse and recovery 42 , 43 . This refers to determining if an existing structure could be entirely or partially reused and incorporated into the new design. Materials, components, packaging, and other items that can be reused, remanufactured, returned, or repurposed would be included in the design 44 . Design for flexibility and deconstruction is a vital feature here, with the goal of creating a process and a structured system that decreases the life of waste while simultaneously designing a model for reuse and repurposing. The flexibility option in design is a significant tool for promoting the adoption of a CE system in various businesses and sectors 45 . On the one hand, the sustainability and Circular Economy (CE) paradigms 46 enhanced awareness of natural resource scarcity among customers and providers. Manufacturers have been forced to change their business strategies to pursue this transformation 47 by detecting and avoiding associated 48 and exploring potential advantages 43 .

Economic sustainability of construction projects

Practices supporting long-term economic growth without negatively harming the community’s social, environmental, or cultural components are called “Economic Sustainability (ES)” 49 . Financial aspects in construction refer to all costs and benefits associated with construction-related functions, from the initial capital investment to operating gains and final return proceeds 23 , 50 . Clients and owners naturally prioritize these issues, especially when breakthroughs or technology are introduced into the sector. Apart from that, how CE adoption leads to ES, which reduces building lifespan maintenance costs, is also demonstrated 51 . They stated that ES is guaranteed when circular design techniques are used, as they promise profitability without compromising people’s demands. Standardization of circular design and construction approaches reduces costs by minimizing repeats while saving on long-term operational costs due to fewer repairs and replacements 52 . They also discovered that ES is reached due to the ease with which materials may be retrieved, lowering material End-of-Life (EoL) costs. ES is thought to be attained when a client receives a good return on their investment by using CE processes and maintaining the quality of the end goods using modular building approaches that reduce waste and increase productivity. Another point of view is that the local economy is bolstered by the development of jobs in recycling and repair procedures, assuring the economy’s long-term viability 53 . Overall, the client’s economy improves due to the lower cost of acquiring new materials, a more sophisticated and consistent product quality and reliable performance achieved through repetitive design and production of modular components 54 .

Hypothesis development

Circular design strategies and organisational culture.

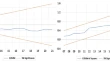

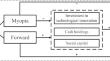

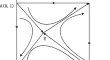

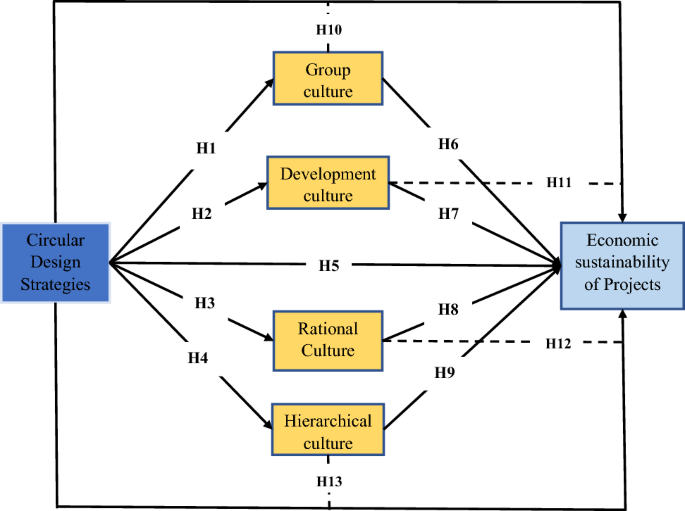

As more businesses employ design thinking techniques to address organizational problems, the need to establish corporate cultures that support the effective use of these tools may become more significant 55 . At the same time, past research has shown that cultural changes usually happen in stages due to organizational life cycle elements, demographic shifts, and members’ exposure to broader societal or professional culture shifts 56 . When rapid changes in corporate values and assumptions are required (for example, in the case of firms adopting circular design strategies), the role of organizational leaders, supported by company-wide initiatives (for example, training, coaching, and role modelling), may be critical in overcoming corporate culture’s natural inertia 57 . Construction companies must build a culture that nurtures creativity and promotes innovation to succeed and “remain externally flexible.” Ismail 58 claims that “innovation will be fostered when culture and way of thinking mix to create new ideas” 59 . Employees will be motivated to take an active role in decision-making and share their innovative ideas with management to improve organizational performance if the company has a strong culture 60 . As such, the following hypotheses were formulated to examine the extent of the relationship between the independent variable (circular design strategies) and the mediating variable (the CVF of group, developmental, rational, and hierarchical cultures). For this section, four hypotheses were developed for the relationship between the IV and each of the dimensions of the MV. The hypotheses were grown, therefore, to assess the relationship based on the proposed research framework shown (Fig. 1 ).

Research conceptual and hypothetical framework.

Circular Design Strategies have a significant positive effect on Group Culture.

Circular Design Strategies have a significant positive effect on Development Culture.

Circular Design Strategies have a significant positive effect on Rational Culture.

Circular Design Strategies have a significant positive effect on Hierarchical Culture.

Circular design strategies and economic sustainability

Sustainable and flexible ideas are crucial characteristics of a good building design 57 ; architects are expected to design robust and long-lasting structures; otherwise, they are fundamentally untenable. The idea is to encourage architects to consider designs for reducing waste generation, as considering waste minimization measures before generating waste is less expensive. For instance, modular construction and design can reduce waste generation on construction sites because fabrication is carried out at factories where production is controllable, thereby improving the economic sustainability of construction 36 . Additionally, empirical evidence that aids in evaluating sustainable methods will tremendously assist clients and can pave the way for future sustainable products 61 . Hence, the following hypothesis was formulated to examine the extent of the relationship between the independent variable (circular design strategies) and the dependent variable (the Economic sustainability of construction projects). The hypothesis was developed, therefore, to assess the relationship based on the proposed research framework shown (Fig. 1 ).

Circular Design Strategies have a significant positive effect on Economic sustainability.

Organisational culture and economic sustainability

According to Isensee et al 62 ., firms that do well in sustainability have a distinct organizational culture. Construction firms are also part of the business sector, and focusing on sustainability can help them compete more effectively. Offering sustainable products and services allows segmentation and customization to satisfy specific needs 63 . There appears to be no single approach to explain how innovations will develop or how culture can be maintained in a building industry with such a diversified and multileveled nature. To be competitive, businesses must continuously develop fresh ideas to improve operations and become more inventive. This is critical for industries like construction as they migrate to more sustainable practices 64 .

Consequently, the following hypotheses were formulated to examine the extent of the relationship between the four dimensions of the MV (group, development, rational and hierarchical cultures) and the DV (ES of construction projects). For this section, four hypotheses were developed for the relationship between the dimensions of the MV (CVF of OC) and the DV (ES of construction projects). The hypotheses were grown, therefore, to assess the relationship based on the proposed research framework shown (Fig. 1 ).

Group Culture has a significant favourable influence on Economic Sustainability

Development Culture has a significant favourable influence on Economic Sustainability

Rational Culture has a significant favourable influence on Economic Sustainability

Hierarchical Culture has a significant favourable influence on Economic Sustainability

The mediating role of OC between CDS and ES

Based on those mentioned earlier, the following hypotheses were also formulated to examine the mediating effect of the four dimensions of the MV (group, development, rational and hierarchical cultures) between the IV (CDS) and the DV (ES of construction projects) in line with RQ4. For this section, four hypotheses were developed to assess the mediating relationship based on the proposed research framework shown (Fig. 1 ).

Group Culture mediates the relationship between CDS and Economic Sustainability of projects

Development Culture mediates the relationship between CDS and Economic Sustainability of projects

Rational Culture mediates the relationship between CDS and Economic Sustainability of projects

Hierarchical Culture mediates the relationship between CDS and Economic Sustainability of projects

Theoretical background

The circular economy idea underpins this research. The CE was first introduced in the 1970s by the Swiss architect and economist Walter Stahel, who recommended that materials be managed in a ‘closed loop’, thereby turning waste into resources. Stahel defined this as a ‘Cradle-to-Cradle’ system and the Linear model as Cradle-to-Grave 65 . The need to stretch out product life through restoration and remanufacture was also emphasized 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 . Consequently, the Cradle to Cradle method was designed by William McDonough (architect) and Michael Braungart (environmental chemist), who stated that it would facilitate ‘design for abundance’ 70 as a result of which they developed the Cradle-2-Cradle (C2C) benchmark to approve and endorse products that justify such standards 44 . CE has evolved and continues to gain traction 71 . The mutual instituting ideologies are based on more outstanding resource organization and waste minimization 71 , 71 , 73 .

Research framework

The current study is unique in that it examines the link between CDS and ESCP mediated by the competing values framework of OC governed by the Circular Economy theory. Figure 1 illustrates the hypothetical research framework proposed for the study.

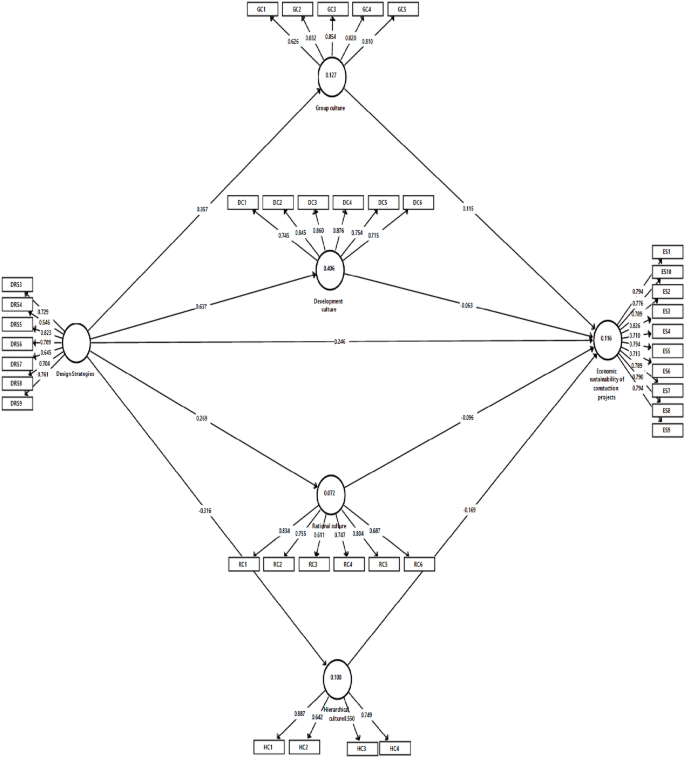

Methodology

Statement: This study confirms that all methods were carried out per relevant guidelines and regulations. Wuhan University’s institutional and licensing committee approved all experimental protocols. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and legal guardian(s).

Survey and data collection

For this study, the Positivist approach and Quantitative techniques were adopted as philosophy and design, respectively, to ascertain the mediating effects of OC on the relationship between CDS and ESCP in the Chinese construction industry. This is to effectively analyze the causal relations and demonstrate the level of direct and indirect relationships among all variables. Given the study’s predefined philosophy and design, a survey technique was used to satisfy the stated goals. As a result of the background and scope provided, the target population for this study was all contracting and consulting firms in the study area. Only northern China was considered for this study, and the reasons were not far-fetched. So far, the southern region of China has hosted many studies on CE implementation and processes 7 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , leaving no clear indices on the subject matter for the northern part. The north area currently consists of three geopolitical zones: North-west, North-Central and North-East. Two provinces from each zone will be picked for the study for appropriate spread, with Shanxi and Qinghai Province representing the North-west, the Inner Mongolia and Hebei provinces representing the North-central zone and Heilongjiang and Jilin Province representing the North-east. These provinces were carefully chosen since they represent areas with a high tendency for construction-related activities.

The total research population is 1535 obtained from https://libguides.library.cityu.edu.hk/busChina/comp-dir (an online directory of registered firms in China, December 2023 version) because of a dearth of data on available construction entities in the industry. However, the population for the selected province was found to be 778 . This was rounded to 800 to attain a research sample 260 based on the Shanxi and Qinghai Province 1970 rule of thumb 74 . The study adopted the proportionate stratified random sampling technique for its suitability in ensuring adequate representation of respondent elements 75 . The data was collected for six months, from June 2019 until November 2023. E-mails and WeChat messages attached with an online link for Google Forms were sent to respondents to complete. Follow-up calls and gentle reminders were sent to research assistants via phone for quick responses and full cooperation. The questionnaires were accompanied by cover letters that included a brief description of the research and assurance of anonymity and confidentiality. In total, 550 survey questionnaires were distributed to Construction Contracting and Consulting Companies in Northern China, of which 390 were returned. Out of the returned questionnaires, 359 were used for data analysis. Data were obtained from Principal partners, Partners, Management staff, Project Managers and Regular staff of these organizations through the survey instruments. Table 1 highlights the statistics of questionnaires distributed, including return and response rates.

Measurements