England Reformation Essay

Rebellions and the english reformation, catherine of aragon.

Bibliography

It is clear to historians that the process of the English Reformation was primarily guided by the nobility and highest ranks of the English government. The decisions of Henry VIII were titular in both the political and theological worlds of the country. Therefore, the reforms accepted and implemented by the government did not originate from the ordinary residents of England in any way. The increased tension between the papal authority and the crown confused people who were not ready for various changes that Protestantism brought along with the onset of Royal Supremacy. 1

The revolts, nonetheless, were not large or significant in their organization, although they often inspired many people to assemble. Arguably, one of the most impactful rebellions was the Pilgrimage of Grace which happened in 1536 and 1537, after the previous Lincolnshire Rising was disbanded. 2

Similar to the majority of all uprisings that happened during the English Reformation, the Pilgrimage of Grace was started by people who were largely affected by the political and economic reforms. Major conflicts between the pope and the King of England started in 1527 when Henry VIII, unsatisfied with his current marriage, sought the Church’s support in a divorce. 3 The focus on religious inconsistencies and the king’s personal desire to have offspring quickly affected other parts of the country’s life.

The enforcement of Protestantism brought changes to the process of worship, and Royal Supremacy started targeting local religious houses to make them repudiate the Catholic authority. 4 This activity provoked violence from the commoners who, while not realizing a direct change in the system before, have understood that the nobility is actively discouraging their beliefs.

In October 1536, the Lincolnshire Rising included almost 40,000 people who wanted to put an end to the suppression of their monasteries and the heresy in the country. 5 Most importantly, they also wished for the king to repeal the laws that limited their use of the land. This initial uprising, while considerably large, was ineffective in persuading the noble family. However, it inspired more people to join, and the Pilgrimage of Grace in Yorkshire was a direct product of the previous rebellion. 6 This event also culminated thousands of people to revolt against the religious disruptions in the state.

In the end, this uprising did not lead to the outcomes how which its members have hoped. First of all, it did not result in the reunification of England with the Catholic Church, as both the king and the pope continued to denounce each other’s authority over the country. The rebellion also did not stop the Protestants from dissolving the monasteries. 7

The nobility was interested in the lands that the church possessed, and the control over large pieces of land was a crucial source of revenue that Henry VIII could not negotiate. Most importantly, the rising did not stop Protestantism from spreading and becoming the official religion of the state. However, it can still be considered an impactful event in the history of the Reformation because it had shown that people denounced Protestantism and saw the actions of their king as heretical. Furthermore, the people convinced the Crown to change the Ten Articles and the Statute of Uses to address some of the religious and land ownership concerns, respectively. 8

Catherine of Aragon was the first wife of Henry VIII, the King of England, and the first ruler who was a part of the English Reformation. She married Henry VIII after her previous husband and Henry’s older brother, Arthur, died before ascending to the English throne. 9 Thus, she became the Queen of England in 1509, becoming a significant figure in the country’s history. However, her marriage was burdened by the fact that her health did not allow her to produce future successors to the throne.

In fact, her only surviving child was a girl, Mary, which dissatisfied Henry VIII. 10 At that time, women never acted as sole rulers in England, thus making Mary’s future uncertain and the relationship between Henry VIII and Catherine – strained. The king, becoming increasingly interested in another woman, Anne Boleyn, decided that the current marriage would not bring him any sons. 11 Thus, he sought the annulment of the marriage, which could only be granted by the Church.

The following events played a substantial role in the formation of the England Reformation. The refusal of the pope to annul the union has led Henry VIII to announce that England was splitting from the Catholic Church and the influence of the latter was no longer official. 12 However, other factors should also be analyzed because the interest in Protestantism did not appear out of this conflict alone. At the same time, the English territory was introduced to the wave of Bible translations – Protestant reformers wanted to spread the word about the New Testament. 13

In 1525, William Tyndale presented an English version of the New Testament, which showed an unseen before interpretation of the Christian thought. 14 The influence of this Bible was significant, and its translation denounced Catholicism and its primary aspects. 15 It is probable that Protestants used the conflict between the papacy and the King to further their ideas. However, they could have succeeded without Catherine’s impact, as they also were supportive of Henry VIII’s royal supremacy ideas. 16 Overall, Catherine’s health was one of the significant factors that impacted the Reformation movement, but the spread of Protestantism was also exacerbated by Henry VIII’s desire for power and independence from the Catholic Church.

Galli, Mark. “What the English Bible Cost One Man.” Christian History , 13, no. 3 (1994): 12-15.

Hoyle, Richard W. The Pilgrimage of Grace and the Politics of the 1530s . Oxford: Oxford, 2001.

Ng, Su Fang. “Translation, Interpretation, and And Heresy: The Wycliffite Bible, Tyndale’s Bible, and the Contested Origin.” Studies in Philology 98, no. 3 (2001): 315-338.

Rockett, William. “Wolsey, More, and the Unity of Christendom.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 35, no. 1(2004): 133-153.

Walsham, Alexandra. “Unclasping the Book? Post-Reformation English Catholicism and the Vernacular Bible.” Journal of British Studies 42, no. 2 (2003): 141-166.

- Richard W. Hoyle, The Pilgrimage of Grace and the Politics of the 1530s (Oxford: Oxford, 2001), 40.

- Ibid., 293.

- William Rockett, “Wolsey, More, and the Unity of Christendom,” The Sixteenth Century Journal 35, no. 1(2004): 136.

- Alexandra Walsham, “Unclasping the Book? Post-Reformation English Catholicism and the Vernacular Bible,” Journal of British Studies 42, no. 2 (2003): 141.

- Hoyle, The Pilgrimage of Grace , 56.

- Rockett, “Wolsey, More,” 134.

- Mark Galli, “What the English Bible Cost One Man,” Christian History , 13, no. 3 (1994): 13.

- Su Fang Ng, “Translation, Interpretation, and And Heresy: The Wycliffite Bible, Tyndale’s Bible, and the Contested Origin,” Studies in Philology 98, no. 3 (2001): 334.

- Hoyle, The Pilgrimage of Grace , 65.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, July 20). England Reformation. https://ivypanda.com/essays/england-reformation/

"England Reformation." IvyPanda , 20 July 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/england-reformation/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'England Reformation'. 20 July.

IvyPanda . 2021. "England Reformation." July 20, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/england-reformation/.

1. IvyPanda . "England Reformation." July 20, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/england-reformation/.

IvyPanda . "England Reformation." July 20, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/england-reformation/.

- Henry VIII and His Sociopolitical Decisions

- Importance of the Renaissance and the Reformation for the European Society

- Chapters 3-4 of Global Women's Issues by Aragon & Miller

- Thomas More and King Henry VIII, their Relationship

- Computing and Cybercrimes

- “The Bull Unam Sanctam” by Pope Boniface VIII

- Chapter 12 of "Global Women's Issues" by Aragon & Miller

- Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” Analysis

- Chapters 1-2 of Global Women's Issues by Aragon & Miller

- The Reformation Era of 1517-1648

- Late Middle Ages as a Stage in Social Development

- Turmoil in the Church During the Middle Ages

- Islam Empire of Faith - The Awakening Documentary

- Chronicling the 14th Century in England and France

- Middle Ages: Churches and Book Illustration

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

The reformation.

Erasmus of Rotterdam

Hans Holbein the Younger (and Workshop(?))

Martin Luther (1483–1546)

Workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder

- The Last Supper

Designed by Bernard van Orley

The Fifteen Mysteries and the Virgin of the Rosary

Netherlandish (Brussels) Painter

Albrecht Dürer

Four Scenes from the Passion

Follower of Bernard van Orley

Friedrich III (1463–1525), the Wise, Elector of Saxony

Lucas Cranach the Elder and Workshop

Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Johann I (1468–1532), the Constant, Elector of Saxony

The Last Judgment

Joos van Cleve

Chancellor Leonhard von Eck (1480–1550)

Barthel Beham

Anne de Pisseleu (1508–1576), Duchesse d'Étampes

Attributed to Corneille de Lyon

Virgin and Child with Saint Anne

Christ and the Adulteress

Lucas Cranach the Younger and Workshop

The Calling of Saint Matthew

Copy after Jan Sanders van Hemessen

Christ Blessing the Children

Satire on the Papacy

Melchior Lorck

Christ Blessing, Surrounded by a Donor Family

German Painter

Jacob Wisse Stern College for Women, Yeshiva University

October 2002

Unleashed in the early sixteenth century, the Reformation put an abrupt end to the relative unity that had existed for the previous thousand years in Western Christendom under the Roman Catholic Church . The Reformation, which began in Germany but spread quickly throughout Europe, was initiated in response to the growing sense of corruption and administrative abuse in the church. It expressed an alternate vision of Christian practice, and led to the creation and rise of Protestantism, with all its individual branches. Images, especially, became effective tools for disseminating negative portrayals of the church ( 53.677.5 ), and for popularizing Reformation ideas; art, in turn, was revolutionized by the movement.

Though rooted in a broad dissatisfaction with the church, the birth of the Reformation can be traced to the protests of one man, the German Augustinian monk Martin Luther (1483–1546) ( 20.64.21 ; 55.220.2 ). In 1517, he nailed to a church door in Wittenberg, Saxony, a manifesto listing ninety-five arguments, or Theses, against the use and abuse of indulgences, which were official pardons for sins granted after guilt had been forgiven through penance. Particularly objectionable to the reformers was the selling of indulgences, which essentially allowed sinners to buy their way into heaven, and which, from the beginning of the sixteenth century, had become common practice. But, more fundamentally, Luther questioned basic tenets of the Roman Church, including the clergy’s exclusive right to grant salvation. He believed human salvation depended on individual faith, not on clerical mediation, and conceived of the Bible as the ultimate and sole source of Christian truth. He also advocated the abolition of monasteries and criticized the church’s materialistic use of art. Luther was excommunicated in 1520, but was granted protection by the elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise (r. 1483–1525) ( 46.179.1 ), and given safe conduct to the Imperial Diet in Worms and then asylum in Wartburg.

The movement Luther initiated spread and grew in popularity—especially in Northern Europe, though reaction to the protests against the church varied from country to country. In 1529, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V tried, for the most part unsuccessfully, to stamp out dissension among German Catholics. Elector John the Constant (r. 1525–32) ( 46.179.2 ), Frederick’s brother and successor, was actively hostile to the emperor and one of the fiercest defenders of Protestantism. By the middle of the century, most of north and west Germany had become Protestant. King Henry VIII of England (r. 1509–47), who had been a steadfast Catholic, broke with the church over the pope’s refusal to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, the first of Henry’s six wives. With the Act of Supremacy in 1534, Henry was made head of the Church of England, a title that would be shared by all future kings. John Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536) codified the doctrines of the new faith, becoming the basis for Presbyterianism. In the moderate camp, Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam (ca. 1466–1536), though an opponent of the Reformation, remained committed to the reconciliation of Catholics and Protestants—an ideal that would be at least partially realized in 1555 with the Religious Peace of Augsburg, a ruling by the Diet of the Holy Roman Empire granting freedom of worship to Protestants.

With recognition of the reformers’ criticism and acceptance of their ideology, Protestants were able to put their beliefs on display in art ( 17.190.13–15 ). Artists sympathetic to the movement developed a new repertoire of subjects, or adapted traditional ones, to reflect and emphasize Protestant ideals and teaching ( 1982.60.35 ; 1982.60.36 ; 71.155 ; 1975.1.1915 ). More broadly, the balance of power gradually shifted from religious to secular authorities in western Europe, initiating a decline of Christian imagery in the Protestant Church. Meanwhile, the Roman Church mounted the Counter-Reformation, through which it denounced Lutheranism and reaffirmed Catholic doctrine. In Italy and Spain, the Counter-Reformation had an immense impact on the visual arts; while in the North , the sound made by the nails driven through Luther’s manifesto continued to reverberate.

Wisse, Jacob. “The Reformation.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/refo/hd_refo.htm (October 2002)

Further Reading

Coulton, G. G. Art and the Reformation . 2d ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1953.

Koerner, Joseph Leo. The Reformation of the Image . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Additional Essays by Jacob Wisse

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Northern Mannerism in the Early Sixteenth Century .” (October 2002)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Prague during the Rule of Rudolf II (1583–1612) .” (November 2013)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) .” (October 2002)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Burgundian Netherlands: Court Life and Patronage .” (October 2002)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Burgundian Netherlands: Private Life .” (October 2002)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Pieter Bruegel the Elder (ca. 1525–1569) .” (October 2002)

Related Essays

- Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

- Baroque Rome

- Elizabethan England

- The Papacy and the Vatican Palace

- The Papacy during the Renaissance

- Abraham and David Roentgen

- Ceramics in the French Renaissance

- The Crucifixion and Passion of Christ in Italian Painting

- European Tapestry Production and Patronage, 1400–1600

- Genre Painting in Northern Europe

- The Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburgs, 1400–1600

- How Medieval and Renaissance Tapestries Were Made

- Late Medieval German Sculpture: Images for the Cult and for Private Devotion

- Monasticism in Western Medieval Europe

- Music in the Renaissance

- Northern Mannerism in the Early Sixteenth Century

- Painting the Life of Christ in Medieval and Renaissance Italy

- Pastoral Charms in the French Renaissance

- Patronage at the Later Valois Courts (1461–1589)

- Pieter Bruegel the Elder (ca. 1525–1569)

- Portrait Painting in England, 1600–1800

- Portraiture in Renaissance and Baroque Europe

- Profane Love and Erotic Art in the Italian Renaissance

- Sixteenth-Century Painting in Lombardy

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of Europe

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1400–1600 A.D.

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1600–1800 A.D.

- Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, 1400–1600 A.D.

- France, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Low Countries, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Rome and Southern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Venice and Northern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- 16th Century A.D.

- 17th Century A.D.

- The Annunciation

- Baroque Art

- Central Europe

- Central Italy

- Christianity

- The Crucifixion

- Gilt Silver

- Great Britain and Ireland

- High Renaissance

- Holy Roman Empire

- Literature / Poetry

- Madonna and Child

- Monasticism

- The Nativity

- The Netherlands

- Northern Italy

- Printmaking

- Religious Art

- Renaissance Art

- Southern Italy

- Virgin Mary

Artist or Maker

- Beham, Barthel

- Cranach, Lucas, the Elder

- Cranach, Lucas, the Younger

- Daucher, Hans

- De Lyon, Corneille

- De Pannemaker, Pieter

- Dürer, Albrecht

- Holbein, Hans, the Younger

- Tom Ring, Ludger, the Younger

- Van Cleve, Joos

- Van Der Weyden, Goswijn

- Van Hemessen, Jan Sanders

- Van Orley, Bernard

Join our Mailing List

The English Reformation: Tradition and Change

- August 1, 2017

- 16th Century , Collection Essays

Introduction

The English Reformation was part of a European-wide phenomenon to reform the church which began in 1517 when legend has it that the German monk and theologian Martin Luther nailed 95 theses (propositions for discussion) to the door of the castle church at Wittenberg to be debated publicly. Chief among these was the church doctrine on indulgences. Indulgences were grants of a remission of punishment for sins committed. In the later Middle Ages indulgences became connected to the doctrine of purgatory, an in-between place in the afterlife where the souls of those who died in state of venial sin could be purged by the prayers and good works of the living. Luther’s objection to the doctrine was based on his reading of the letters of St Paul from which he concluded that no performance of rituals nor acts of piety could guarantee salvation and that no intermediary authority, priest, bishop, or pope of the church could stand between a human being and God.

Like reformers before him, Luther hoped to reform the church from within. His dispute, however, grew into a challenge to the church’s authority to determine legitimate interpretations of scripture and rituals of worship. Sola fide (“by faith alone”) and sola scriptura (“by scripture alone”) became the watchwords of Lutheran reform that salvation was based on faith and Biblical authority was the only standard for determining correct doctrine. By the early 1520s, Luther and his supporters had broken with the papal authorities, Luther was excommunicated, and German principalities had become embroiled in the conflict. By the middle of the sixteenth century, this protest, “Protestantism,” had three main doctrinal centers: the Lutherans in Germany; Zwinglians in Switzerland; and Calvinists in Geneva. Although the reformers were divided on many specific issues, they shared three common points of view: the removal of the papacy and the religious system he oversaw, an emphasis on a Bible-centered theology and spirituality, and the need for laity to be able to read Sacred Scriptures in the vernacular.

The Reformation in England was not removed from these events on the continent. Until the mid-twentieth century, the narrative of England’s Protestant nationalist triumph answered very neatly the question of how England became Protestant. Historians have since moved away from thinking in terms of the Reformation as a single, linear process that was inevitable. Most historians now accept that there was a “begrudging conformity” in public in England throughout the sixteenth century, as church legislation swung from the long reign of Henry VIII and his break with Rome, to Edward VI’s and Mary I’s relatively short reigns and their swings from radical Protestantism to Catholic restoration respectively. The Reformation as it unfolded in England can be understood as a tension between continuity and change.

What is a Protestant? What is a Catholic? Royal legislation made for quick changes in religious practice, but belief and acceptance of those changes occurred much more slowly. Compulsion and compliance by law by either a Protestant or Catholic prince did not equal assent or conversion by the population. As Protestant identity developed over time, so too Catholic identity was transformed. Historians have argued that practicality describes the response of most people toward the reformation. What was most practical for people to do—conform to the new ways or resist them? Not all Protestants nor all Catholics became martyrs for their faith. Everywhere there are elements of a lingering continuity with what had come before. The passage of time was in many ways as significant as the legislation mandated from on high.

All European rulers and states of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries used terror and torture as a tool of authority. Though Mary I is known in history and popular culture as “bloody Mary” for her execution of 284 Protestant martyrs, her father, brother and sister did not shy away from starving, beheading, hanging in chains, drawing and quartering their enemies, and burning heretics. Did the brutality of religious wars on the continent in the sixteenth century and in England in the seventeenth century lead to calls for religious toleration and a pluralistic society later in the seventeenth and eighteenth century? Some historians argue that a new attitude took root and people eventually came to live with the notion that universality and religious unity was not possible. Not that people became tolerant per se, but that they became tolerant of the fact that there would always be differences. In the sixteenth century religion and conformity to religion was a matter of public concern. By the eighteenth century, religion as a matter of private concern had taken root. The Protestant Reformation questioned and eventually uprooted the idea of a united Christendom and a universal church under the authority of the papacy that had been maintained by the western Church throughout the middle ages. The loss of unity splintered Christianity. In England, the break with Rome created a state church that was not independent of royal control. However, the state church splintered and could not maintain a unified religious identity, nor did it become part of a wider community of “international protestantism.”

As you explore the primary sources in this collection, here are some things to keep in mind when examining the documents.

- Pay attention to the language in which a work was published. Was a document printed in English or Latin? Language could help determine a work’s audience. A work in English would reach those who were not classically educated in Latin or Greek, but a document published in Latin did not necessarily mean it would be of interest only to an elite readership. Latin was not a dead language in the sixteenth century, all professional and educated men and women would have known Latin. Publication in Latin may have excluded some readers, but it also would allow for a broader international reading public outside of England.

- Notice the place of publication of books and documents. London was late in developing a publishing industry and before the 1550s most works were imported. English authors often sent their works to the continent to be published. This supports the argument of transnational influences on the English Reformation.

Essential Questions:

- What is the English Reformation?

- Was the Reformation in England a success? Is this a valid question?

Spirituality and Popular Piety in the English Church c. 1500

The English church at the end of the Middle Ages has been characterized as both vital and vulnerable. While there is a long-standing tradition of popular anti-clericalism in medieval England, glimpsed in literary works such as Langland’s Piers Ploughman and Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales , historians generally concur that there was a sense of satisfaction with the institutional church in the early sixteenth century.

The church in England was vast and it pervaded all aspects of life. As in other parts of medieval Europe, English life revolved around the church calendar and the liturgical seasons of preparation and feast: Advent, Christmas, and Epiphany; Lent, Easter, and Pentecost. Formal worship was centered on Sunday’s Mass and Eucharist, but daily prayer and rituals were knit tightly into the fabric of society. An individual’s life was marked out by church sacraments and rituals—baptism, communion, marriage, and death.

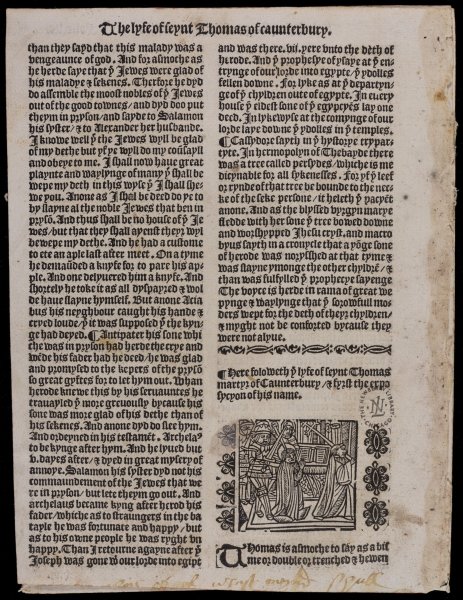

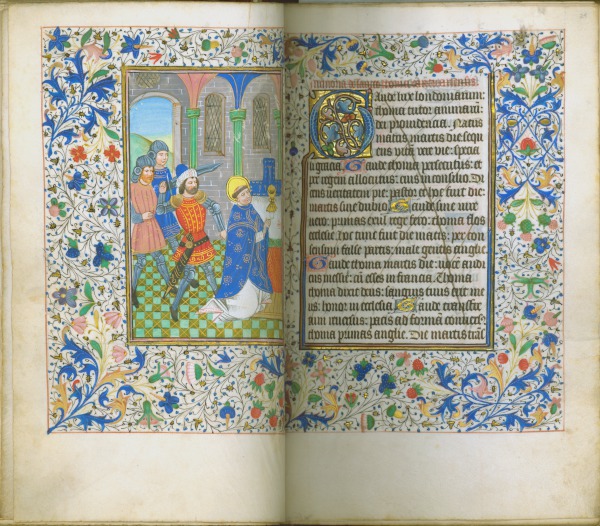

St Thomas of Canterbury was perhaps the most popular English saint in the later middle ages. His shrine and the pilgrimage to it were immortalized in Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales . Thomas Becket (1118-1170) had been the archbishop of Canterbury under Henry II (1133-1189) in the twelfth century. According to the “Lyfe of St. Thomas” in Caxton’s 1509 “englyshed” edition of Jacques Voragine’s Golden Legend (c. 1260), Thomas had blocked the king’s actions in a series of contests over royal control of the English Church, and the jurisdiction of royal and ecclesiastical courts. Thomas used the papacy to thwart Henry’s slights to church prerogative and traditional rights. After one episode, Henry uttered words in anger against Becket in the company of his knights that led them to murder the archbishop on the altar of Canterbury cathedral.

Henry did public penance for the anger that prompted the killing. One of acts of penance was to establish an order of Carthusian monks to England. In 1215, his son, King John, in a failed contest with the nobles and churchmen of England signed the Magna Carta whose first article declares the liberty of the church of England.

In general historians agree that the majority of English men and women were content with the spirituality, piety, church apparatus and structure. Contentment, however, did not mean people were uncritical. Popular anti-clericalism that existed throughout the middle ages concerned resentment over tithes and the wealth of the church in general, but there was no widespread violence in England against its clergy.

Questions to Consider:

- Consider how medieval devotional practices fulfilled spiritual needs by habitual practice.

- According to the “Life of St Thomas Becket,” what makes him a saint?

- How does the “Life of St Thomas Becket” articulate the tensions between king and church?

Why Reform the Church? Henry VIII and the “First” English Reformation

The English Reformation did not come about because a mass of the population was dissatisfied with the church. At the outbreak of Luther’s challenge to the church in 1517, Henry VIII did not embrace Luther’s reform. In 1521, Henry VIII was granted the title “Defender of the Faith” by Pope Leo X for his Defense of the Seven Sacrament s against Martin Luther’s continued attacks on the church’s theology and governance structures.

England’s Reformation was set in motion by Tudor dynastic problems. In the 1520s, Henry VIII had no legitimate male heir. Two sons born to him by his wife, Catherine of Aragon, did not survive infancy. Their only surviving child was a daughter, Mary, born in 1516. The Tudors were a new monarchy that emerged out of the chaos of the War of the Roses in the late fifteenth century. Dynastic stability and securing the throne, were central concerns to any kingship. Although medieval England had had powerful royal women, the purview of governance according to ancient and medieval philosophers and theologians belonged to men. For Henry VIII, security of the kingdom was not a theoretical problem, but a serious threat. Henry was not alone in his fear that the Lutheran challenge to the church could result in social, religious, and political disruption leading to violence in England as it had in Germany. Henry’s succession crisis, referred to then and now as the “King’s Great Matter,” became the catalyst for England’s break with the Church.

In 1527, Henry began his petitions to the pope for an annulment of his marriage to Catherine so he could marry a younger woman, Anne Boleyn, in the hope that she would give him the male heir that Catherine could not. By 1529, Henry’s impatience for a papal annulment grew as Rome delayed the king’s petition. Between 1527 and 1541 three important actions moved England toward a national church: the Submission of the Clergy (1532); the Act of Supremacy (1534) which ended papal jurisdiction in England; and the destruction of the monasteries in England which uprooted centuries of monastic culture. By 1535 Henry had created an absolutist monarchy and oversaw a national church. Yet Henry never committed England to Luther’s theological positions and upheld the episcopal church structure and many Catholic theological doctrines.

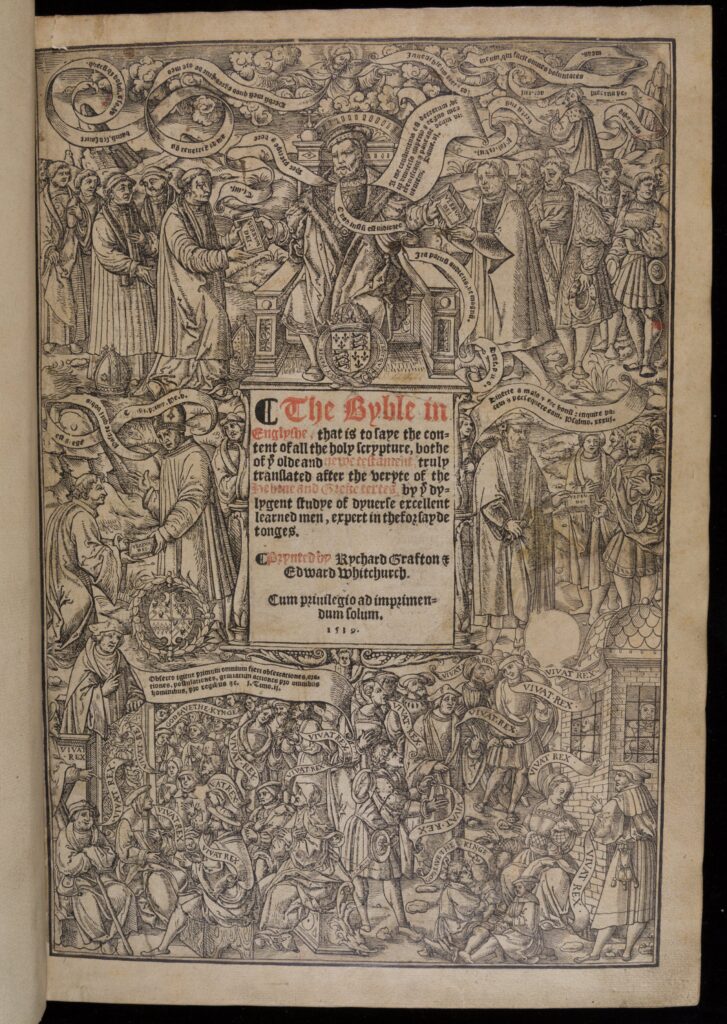

One reformist goal to which Henry did subscribe was to authorize the translation and publication of a bible in English. Until the printing press of the mid-fifteenth century, bibles in the Middle Ages were handwritten often on animal skin parchment (vellum) which was difficult and expensive to produce. Henry’s Great Bible of 1539 and 1540 became the royal authorized editions. The title page image from the Great Bible shows the dissemination of the book to the grateful people of England. Henry commanded that the book be placed prominently in all English churches. Yet not long after this, Henry enacted legislation to restrict its reading. In May 1543, The Act for the Advancement of True Religion forbade the reading of the Bible in English by “women, artificers, apprentices, journeymen, serving-men of the rank of yeoman and under, husbandmen (peasant) and laborers.”

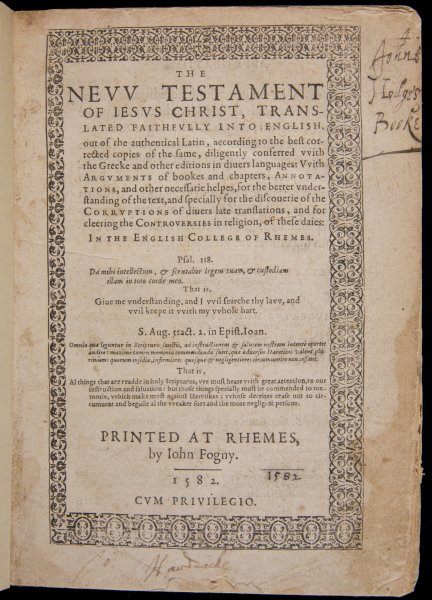

Henry’s was not the last version of the bible in English. By the late sixteenth century new versions had appeared including an authorized Catholic translation, the Douay-Rheims translation of the New Testament (1582). This work, along with other translations, would be used to create what one historian calls the emblem of the English Reformation: the King James Bible of 1611.

Selection: The Book of Hours, Use of Salisbury (1455).

Questions to Consider

- How would Reformers on the continent view/respond to Henry VIII’s Reform of the Church?

- Consider the power of print, image, and pilgrimage that lead Henry VIII to de-canonize St. Thomas of Canterbury. What made this such a powerful story for Henry that he had to suppress the cult of St Thomas of Canterbury?

- How does the title page of the Great Bible literally illustrate Henry’s Act of Supremacy? How does the visual support the written text?

- Does the fact that Henry later on placed restrictions on reading the English Bible diminish his action in authorizing its translation and distributing it?

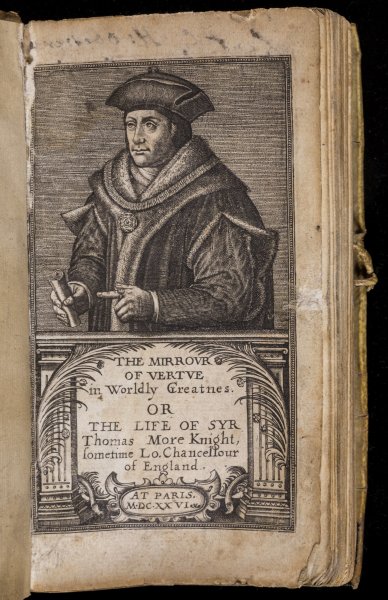

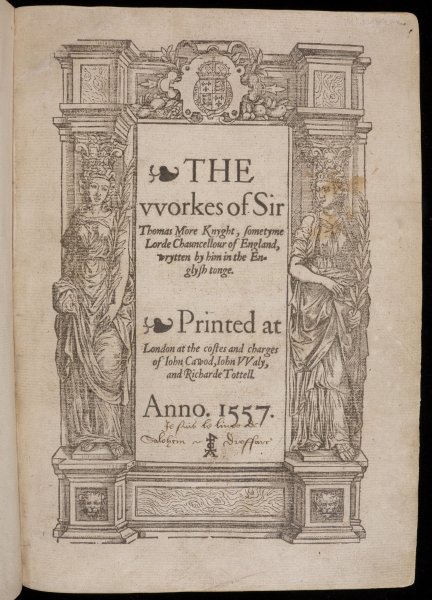

Thomas More: A Man for All Seasons or a Man of His Time?

Many authors over four centuries have hoped to capture the true Thomas More and his place in England’s Reformation. The binary of More the humanist and More the persecutor of heretics stymies us. It might be less problematic if we consider the context in which both Mores existed. More was part of an international humanist circle. More, like other humanists, satirized society, politics, the church and its clergy and monks even as he remained steadfast in his commitment to the traditional view of salvation from Christ through the Church, the legitimacy of Christian unity under the pope, and that “outside the Church there is no salvation.”

More’s Utopia and other humanist writings predated the challenge of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses (1517). But the world that More inhabited, that allowed him to produce the Utopia , had changed by the 1520s. In 1521 Pope Leo X excommunicated Luther. Henry VIII authorized his Chancellor and Archbishop Thomas Wolsey to begin a campaign to prevent the Lutheran heresy from spreading in England. In 1524-25 Germany erupted into violence. Henry and Wolsey feared that England would succumb to violence as Germany had. Thomas More was enlisted to counter Lutheran pamphlets in English and engaged in raiding publishers’ warehouses that imported books from Europe. This is the context for More’s turn from the tolerance he wrote of in 1516 in Utopia to the suppression of dissent and heresy that he took seriously.

Question to Consider:

- Comment on the statement: “Who the real Thomas More is matters less than who he became for posterity.”

The Power of Image and Word: Constructing Religious Identity in the English Reformations 1547-1570

Henry VIII’s reforms in the 1530s and 1540s had undercut long-standing religious practices and doctrines such as pilgrimage and the cult of the saints, but it was not entirely divorced from all aspects of the traditional church. Henry viewed the results of his reforms as setting the true church back on course.

Recent scholarship on the English Reformation has been focused on how the mass of the population who were neither radical reformers nor radical dissenters were turned either toward support for reform or support for the traditional religion. Two ways in which religious identity in the English Reformations was shaped was in the construction of national histories along confessional lines, and in revisions to such texts as the Prymer and Prayerbooks. Printing was not a new technology in the 1540s, but England had far fewer publishing houses than continental Europe. It was one of the most important tools of the Reformation era, as printing helped stimulate a “wider public discussion of evangelical issues” and reinforce religious ideas.

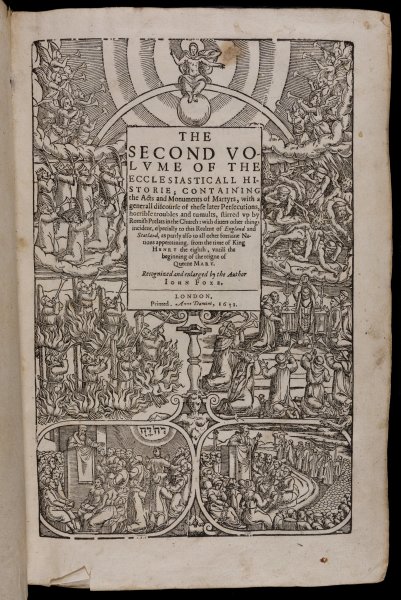

Selection: John Foxe, Ecclesiastical History Containing the Acts and Monuments of Martyrs (1631).

Henry’s legislation in the 1530s and 1540s had overturned 1000 years of Christian practice in less than a 15 year period. The lack of clarity over the new doctrines and rituals caused public confusion. To explain, defend, and especially to denounce resistance to changes in the reform of the English church, Henry’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, utilized the printed word and image to promote and propagandize.

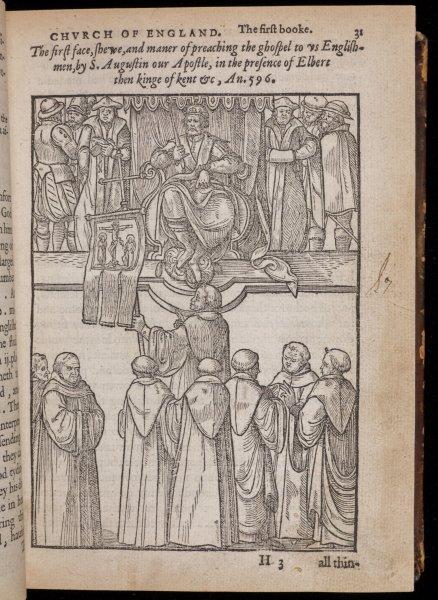

Catholics challenged the Lutherans with the question: “where was your Church before Luther?” The question implied the antiquity of the Roman church tradition against the parvenu status of Protestantism and the origins of Christianity. If England owed its Christianity to missionizing efforts of the papacy, how could they break with Rome? When and how was England converted to Christianity? More importantly, Catholic histories in the sixteenth century argued that the spiritual identity of England predated its political identity.

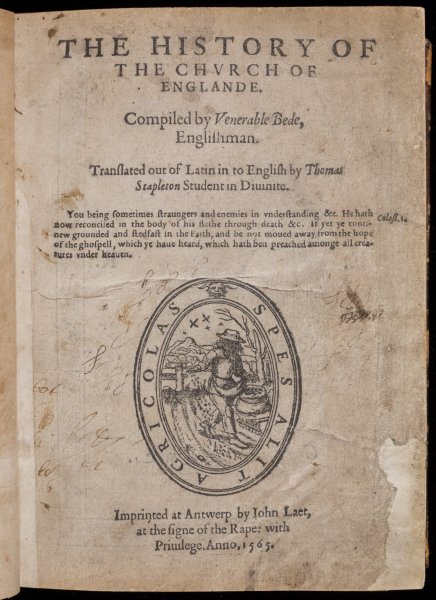

Selection: Bede, The History of the Church of England , translated by Thomas Stapleton (1565).

The documents in this section illustrate how English reformers were engaged with the broader religious debates on the continent and built on traditional images to put forth and convince their audiences to a new point of view. They are examples of the use of history and prayer books and show the fine line between propaganda and education.

- When and how did England become Protestant? When do the terms Catholic and Protestant become meaningful in sixteenth-century England?

- How did a minority reform movement become the majority? How did a majority Catholic nation become a minority?

Emblems of the English Reformations

Alexandra Walsham notes that Catholicism and anti-Catholicism, Protestantism and anti-Protestantism are linked bodies of opinion and practice that “exerted powerful reciprocal influence upon each other.” To understand the internal history of Catholics and Protestants in England one cannot exclude the lateral connections the churches, congregations, and sects had with each other. She describes certain devotional and symbolic objects of the English Protestant and Catholic Reformations that become emblems of faith and religious identity by the late sixteenth-century.

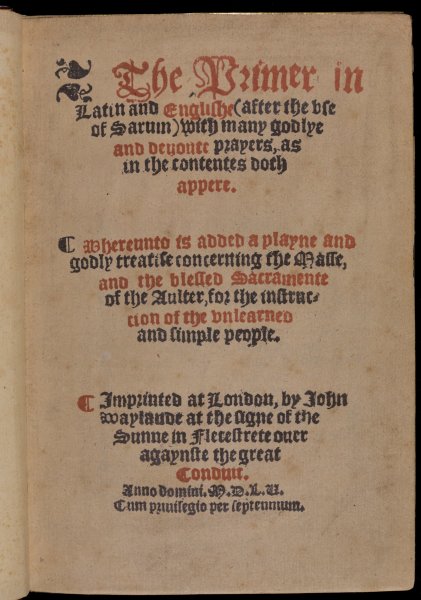

Selection: The Prymer in Englysh and Latyn (after the use of Sarum) (1555).

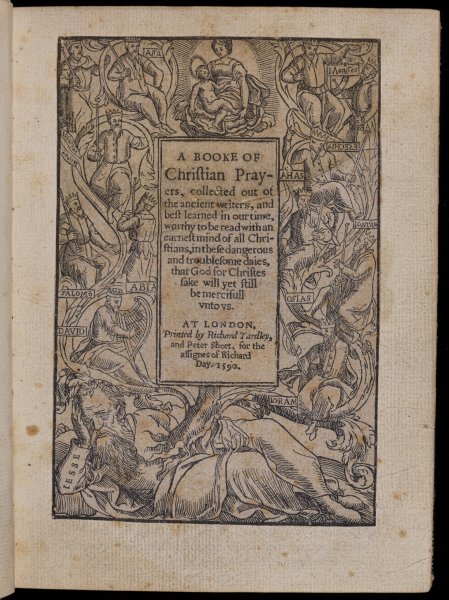

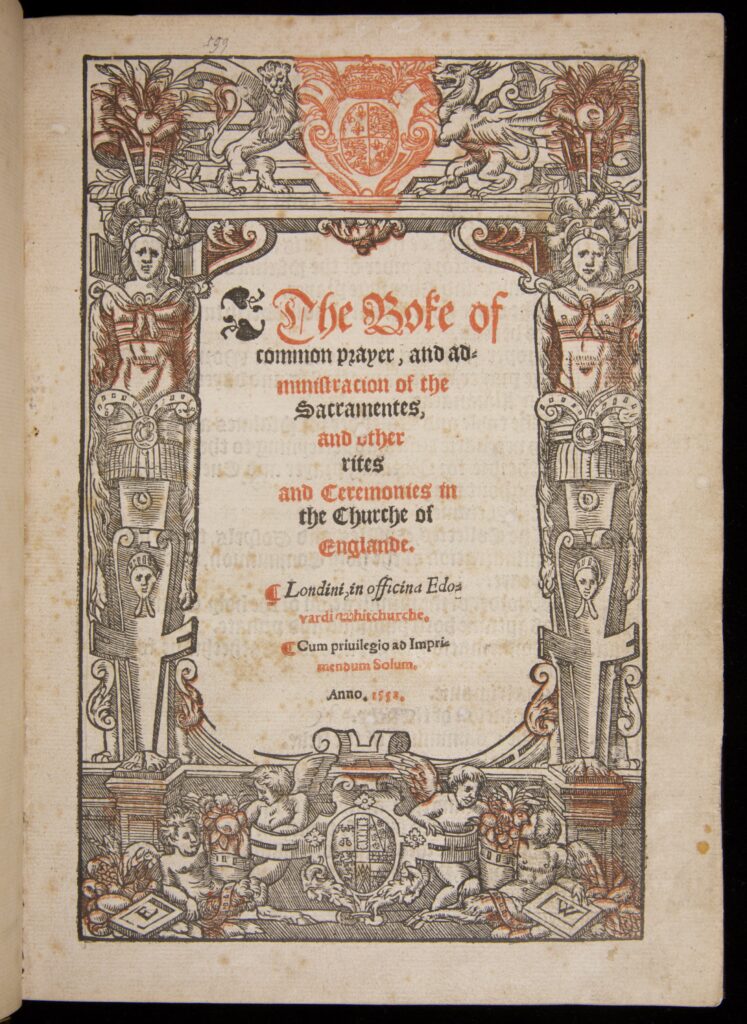

Three important emblems of the English Protestant Reformation are confirmed by several generations of use: the Book of Common Prayer; the Bible in English, and the English hymnal. Although aspects of the Church of England will be challenged by dissenting voices of Puritanism, the Bible, the Book of Common Prayer and the English hymnal will unify the faithful and sustain Protestant religious identity in England into the twentieth century.

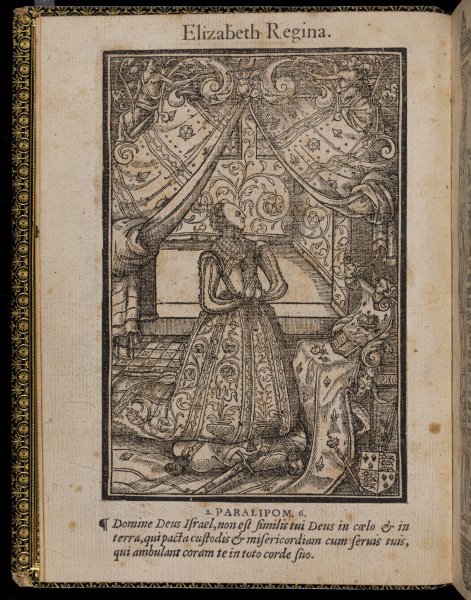

Selection: A Booke of Christian Prayers (1590).

For Catholics in England in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Pope Pius V’s excommunication of Elizabeth in 1570 made a difficult situation worse. In the document, the pope released English Catholics from obedience to Elizabeth whom he declared a heretic. This triggered further proscriptions on Catholics in England and made them a persecuted minority. Walsham points out that the need to practice the faith in secret, to avoid the authorities, and to cope with exclusion from public life paradoxically acted as a catalyst for Catholic religious identity-building. The private Catholic home became a substitute for the ecclesiastical buildings taken over by the Protestants. Reliance on the sacraments (which were outlawed) gave way to the use of “sacramentals,” blessed objects, medallions, scapulars, crucifixes, but especially the rosary. The rosary became an emblem of Catholicism, “the unlearned man’s book,” solitary piety defying institutional control. All these consecrated objects were portable and could be used without the mediation of a priest. They became symbols of a persistent resistance to Protestantism.

- Compare the calendars of Mary’s Prymer of 1555 with the calendar in the 1577 edition of the Book of Common Prayer. How do these calendars compare to the 1611 online edition of the calendar in the King James Bible?

- One historian has said the Book of Common Prayer was intended as an instrument of social and political control. Can a book be both a religious work and an instrument of social and political control?

- Compare the passages from the Vulgate Bible to passages from the King James Version of the Bible. Are the content and language of the passages similar?

Primers and Prayer Books: A Primer (or Prymer) is a book of devotion and instruction. It is generally a prayer book to be used by ordinary people on a daily basis that contains “prime texts” such as the Creed and the Lord’s Prayer. The Primer and prayer book cited here are examples of how traditional books continued to be the medium to transmit theology and religious heritage. The books also stand as examples of the shifting doctrinal messages the English population received in the reigns of Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I.

Book of Common Prayer: Centrally-regulated worship was something that Protestants and Catholics both experienced in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Elizabeth outlawed the Mass and priests and compelled all her subjects to attend Protestant services or face fine or imprisonment. Since 1549, the Book of Common Prayer approved by the state and church was the only authorized book of worship in the church in England.

Selection: The Booke of Common Prayer and the Administration of the Sacraments, and other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church of England (1552 and 1577).

The Bible in English: The vernacular Bible is one of the major achievements of the Protestant Reformation. In spite of specific theological differences, the major reformers shared the goal of making the Bible available for a literate laity to read and for the illiterate to hear, in a language they understood. The vernacular Bible is an emblem of the Protestant Reformation. The King James Version of the Bible is an emblem of the English Reformation. The Bible in use through most of the Middle Ages was called the Vulgate, a translation made by St. Jerome from Greek and Hebrew into Latin (the vulgar, i.e. common language) in the fourth century. At that time, Latin was a language that was more accessible than either Greek or Hebrew. By the later Middle Ages, the numerous hand-written volumes of Jerome’s Vulgate, copied over and over, were often filled with errors. The Vulgate is famously the first book printed on the Gutenberg printing press.

Selection: The New Testament of Jesus Christ (1582).

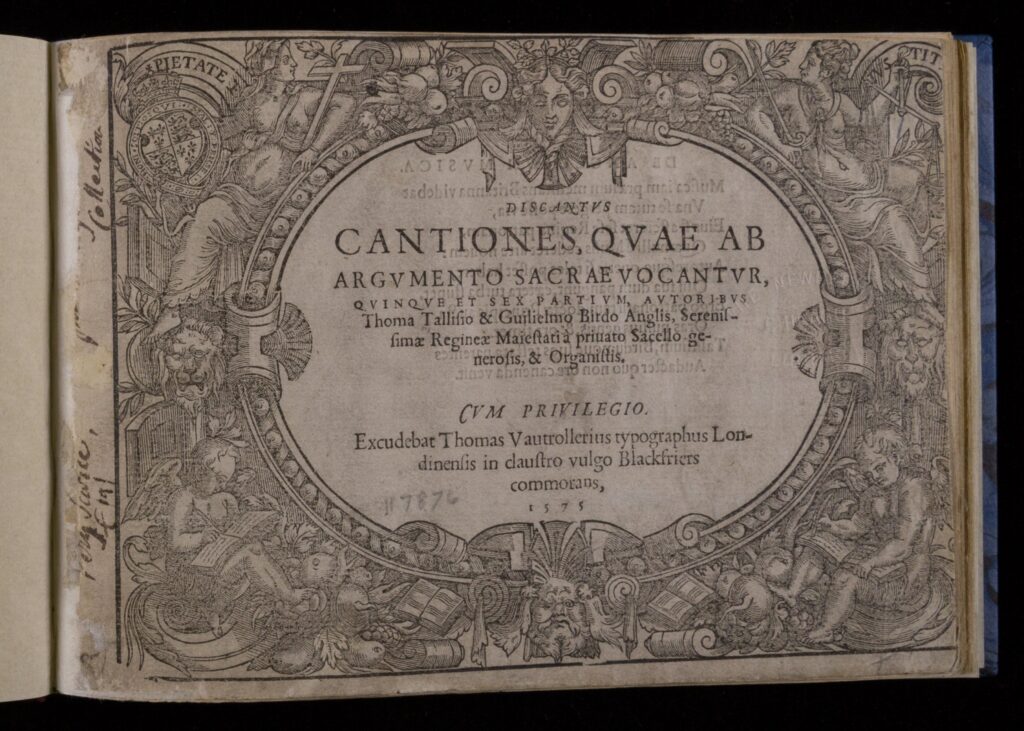

The English Hymnal: Henry VIII’s destruction of the monasteries, the visual monuments of Catholicism that peppered the landscape of medieval England and his son Edward’s whitewashing of church interiors and destruction of centuries of English Catholic art–painting and sculpture, conformed England to a Protestant idea of Catholicism as idolatry. It also turned English worship away from the visual to the aural. The word of God was to be read, preached, and heard. There is no monumental church art or architecture in England in this period, but there is a great emphasis on liturgical music especially in the works of William Byrd and Thomas Tallis.

Selection: Thomas Tallis, Discantus Cantiones, quae ab Argumento Sacrae Vocantur (1575).

Selected Sources

The Beginnings of English Protestantism . Eds. Peter Marshall and Alec Ryrie. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Duffy, Eamon. Reformation Divided: Catholics, Protestants, and the Conversion of England . London, Oxford, New York, New Delhi, Sydney: Bloomsbury Press, 2017.

Gunther, Karl. Reformation Unbound: Protestant Visions of Reform in England 1529-1559 . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

MacCulloch, Diarmaid. Thomas Cranmer: A Life . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

Heal, Felicity. “Appropriating History: Catholic and Protestant Polemic and the National Past.” Huntingdon Library Quarterly , v. 68, no. 1-2 (March, 2005), 109-132.

Highley, Christopher. Catholics Writing the Nation in Early Modern Britain and Ireland . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Hyatt Mayor, A. “Queen Elizabeth’s Prayers,” The Metropolitan Museum Art Bulletin , N.S. v. 1, no. 8 (April, 1943), 327-242.

King, John N. Tudor Royal Iconography: Literature and Art in an Age of Religious Crisis . Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

Parish, Helen. Monks, Miracles and Magic: Reformation Representations of the Medieval Church . New York: Routledge, 2005.

Pettegree, Andrew. “Illustrating the Book: a Protestant Dilemma,” in John Foxe and His World . Eds. Christopher Highley and John N. King. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002, 133-44

Quantin, Jean-Louis. The Church of England and Christian Antiquity. The Construction of Confessional Identity in the 17th Century . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Shagan, Ethan. Popular Politics and the English Reformation . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Walsham, Alexandra. Catholic Reformation in Protestant Britain . Farnham, UK & Burlington, VT: Ashgate Press, 2015.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

ESSAY: English Reformation Historiography

Related Papers

This paper explores the similarities and differences between reforming movements in England and the rest of Europe. Please note: If you are a student at any University, and you wish to cite my essay, do so prudently. It has not been published in any journal or paper, and will not be considered a properly peer-reviewed source by your teachers. Instead, I would advise you to bounce off my ideas; use them to deepen your own inquiries into the topic.

An essay comparing the historiography of A. G. Dickens, Eamon Duffy, and Diarmaid MacCulloch

Joseph Cotter

The Catholic Historical Review

Lawrence Siwan

Erik DiVietro

The popular perspective on the English Reformation is often superficial, without consideration of the political and ecclesiastic forces that formed the events of the Reformation as well as the results of it. There is a need to establish the narrative within the context of canon law and international diplomacy in order to understand the symbiotic relationship between these forces and ecclesiastic reform, especially in England.

Peter B Nockles

Irish Historical Studies

Henry A Jefferies

Renaissance and Reformation

Diarmaid MacCulloch

The Journal of Ecclesiastical History

debora shuger

RELATED PAPERS

Jean-Yves Fortin

Mahmoud Abdel-Dayem

Uche A Dike

Central European Journal of Medicine

Filomena Pierri

John Cairns

Garcia Palominos

Gonzalo García Palominos

… and abstracts of the …

Robert Ferris

Márcia Falcão

HAPPY SINGH

Cancer research

Recep Serdar Alpan

Muhammad Tohirin

Biomolecules

Elias Christoforides

Bogusław Wowrzeczka

Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia

Adriano Gomes Páscoa

Salvador Mercado

Jacob Perez

Microwave and Optical Technology Letters

Dedi Irawan

The Middle East and its neighbors: a collection of articles dedicated to the 70th anniversary of Professor Nikolai Nikolaevich Dyakov

Angelika O. Pobedonostseva-Kaya

Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs

Zhongqi CHENG

The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America

Jin-Meng Ho

ACM SIGMETRICS Performance Evaluation Review

Jeremy Munday

Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science

Vicente Urios

Hydrogeology Journal

Gerfried Winkler

Digestive and Liver Disease

Ilaria Tarantino

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section English Poetry

Introduction, general overviews.

- Reference Works

- Tudor and Stuart Verse

- 16th-Century Verse

- 17th-Century Verse

- Bibliographies

- Tudor-Stuart Criticism

- Criticism of 16th-Century Poetry

- Criticism of 17th-Century Poetry

- Christopher Marlowe

- John Milton

- William Shakespeare

- Sir Philip Sidney

- Edmund Spenser

- Poet, Patronage, and Politics

- Poetry, Gender, and Sexuality

- Poetry and Science

- Poetry and Religion

- Classical Influences

- Continental Influences

- Poetry, Manuscript, and Print

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- English Renaissance Drama

- George Buchanan

- George Herbert

- Hester Pulter

- Katherine Philips

- Literary Criticism

- Lyric Poetry

- Ovid in Renaissance Thought

- Thomas Wyatt

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Mining and Metallurgy

- Pilgrimage in Early Modern Catholicism

- Racialization in the Early Modern Period

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

English Poetry by James P. Bednarz LAST REVIEWED: 25 April 2019 LAST MODIFIED: 26 November 2019 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195399301-0209

The English Renaissance, the age of William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, Sir Philip Sidney, Ben Jonson, John Donne, and John Milton, was one of the most brilliant periods in Western literary history for the production of great poetry. Yet the scope of its achievement is so varied that any effort to account for its multiplicity is inordinately challenging. Between 1509, with the reign of Henry VIII, until the end of the Commonwealth in 1660, nondramatic poetry of the most varied kind—from epic to ballad—found a voice and an audience in recitation, manuscript circulation, and print. The period’s ideals were inscribed in the heroic narratives of Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene and John Milton’s Paradise Lost , in a culture that embraced the epic as a means of political and theological reflection. But just as Renaissance poets looked outward at the turbulent world of early modern history, which they measured in terms of a mythic glorious past, they simultaneously gazed inward to focus on basic issues of identity and subjectivity, being especially attentive to the intricate trajectories of human desire. Beginning with the lyric poetry of John Skelton and Sir Thomas Wyatt, the blending of native, classical, and Continental influences added richness to verse that easily moved from the high to low, from earnest self-scrutiny and entreaty to mockery, play, disdain, and detachment. These qualities would mature in Shakespeare’s Sonnets . English Renaissance poetry is customarily divided chronologically in two ways. Scholars distinguish between either the 16th and 17th centuries or between Tudor (1485–1603) and Stuart (1603–1649) periods. The division between Tudor and Stuart poetry is useful, for instance, in tracing how different poetic concerns, such as satire and religious poetry, challenged sonnet and epic. It helps account for how a growing insistence on “strong lines” of condensed poetic thought found expression in both the measured Augustan style of Ben Jonson and the mannered wit of John Donne. But these divisions can also obscure significant similarities as well between writers such as Spenser and Jonson or Sidney and Milton, who share surprisingly similar attitudes on a variety of literary, political, and social issues. For quality, rhetorical genius, emotional complexity, depth, and variety, the poetry of the English Renaissance is unsurpassed.

One of the scholarly rituals that anyone interested in understanding the breadth of Renaissance poetry must perform is to read the historical overviews Lewis 1954 and Bush 1945 (the third and fifth volumes of the Oxford History of English Literature series ) on 16th-century and 17th-century verse. You will probably find grounds for disagreement with their surveys, but you also will have to admire their skill in covering an immense number of works in different genres, while presenting a literary transition that takes readers from the late Middle Ages to the Restoration. Although, by turns, quaint, quirky, and weathered, Lewis was a voracious reader who still provides the best comprehensive study of the development of English Renaissance poetry in the 16th century: and he does this in alternating chapters that parallel philosophical and stylistic changes in verse and prose. He also successfully grounds the period’s poetic forms in the work of the late Middle Ages, providing an excellent context for assessing their native antecedents. Nevertheless, his division of the century between an earlier “Drab” and a later “Golden” style, as Winters 1967 has shown, is too pejorative and simplistic to account for the patent merits of the so-called plain style in the work of poets such as George Gascoigne. In line with Lewis’s estimation, however, Waller 1993 is an especially impressive treatment of the literary genius of Spenser and Sidney. Bush’s command of the field is equally impressive. He recognizes, from the start, the need not to insist too firmly on a difference between “cavalier” and “metaphysical” poets, since these conceptual modes and their resulting styles shared a more fluid interrelation in 17th-century verse. And he does not neglect the towering figure of Milton or the age’s heroic verse. Of the many more recent guides, Waller 1993 and Cheney 2011 provide excellent introductions to the earlier Renaissance, while Parfitt 1995 , with a few questionable evaluations, renders a similarly comprehensive account of later developments.

Bush, Douglas. English Literature in the Earlier Seventeenth Century, 1600–1660 . Oxford History of English Literature. 2d ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1945.

Bush provides an expert analysis of how Renaissance poetry was shaped by the concerns of its age, as he situates poetic form within the literary, social, political, and religious tendencies of Stuart culture. The period’s major poets are each considered in a separate chapter.

Cheney, Patrick. Reading Sixteenth-Century Poetry . Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

DOI: 10.1002/9781444396560

Cheney divides his study among Henrician, Edwardian, and Marian poetry from 1500 to 1588 and Elizabethan poetry from 1588 to 1603. Focusing on the pleasures and uses of poetry, he organizes his book around a series of historical changes that can be seen in the key categories of voice, perception, world, form, and career. A helpful bibliography is appended.

Lewis, C. S. English Literature in the Sixteenth Century, Excluding Drama . Oxford History of English Literature. Oxford: Clarendon, 1954.

This is an excellent starting point for students who want to secure a firmer knowledge of 16th-century English verse in its various permutations. Lewis is nevertheless at his best when considering the “Golden” period realized by the masterpieces of Sidney and Spenser.

Parfitt, George. English Poetry of the Seventeenth Century . Longman Literature in English. 2d ed. London: Longman, 1995.

Parfitt’s book complements Waller 1993 in the same series. He analyzes lyric, the poetry of place, poems of occasion, satire, and epic. It has a chronology, a general bibliography, and bibliographies of individual writers. Together Waller and Parfitt furnish a set of intelligent and wide-ranging introductions that emphasize the political and social conditions that shaped the writing of poetry.

Waller, Gary. English Poetry of the Sixteenth Century . Longman Literature in English. 2d ed. London: Longman, 1993.

Waller’s informative account of the period extends from Dunbar and Wyatt to Shakespeare and Donne, and it is organized into chapters devoted to contemporary engagements with the period. Chapter 8, “Gendering the Muse: Women’s Poetry, Gay Voices,” and chapter 9, “Conclusion—Reopening the Canon,” typify the author’s interest in producing a more inclusive evaluation. The volume features a chronology, general bibliographies, and notes on individual authors.

Winters, Yvor. Forms of Discovery: Critical and Historical Essays on the Forms of the Short Poem in English . Chicago: A. Swallow, 1967.

“The 16th Century Lyric in England” was originally written in 1939 and then revised for this book. In his assault on the English Renaissance canon, Winters responds to Lewis 1954 by dividing 16th-century lyric between the “plain” and “sugared” styles to suggest the superiority of such unappreciated authors as Barnabe Googe, Nicholas Grimald, Jasper Heywood, Thomas Nashe, and George Turberville, who were capable of direct, forceful, and moving verse. The “sugared” style is too sweet for Winters’s taste.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Renaissance and Reformation »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Aemilia Lanyer

- Agrippa d’Aubigné

- Alberti, Leon Battista

- Alexander VI, Pope

- Andrea del Verrocchio

- Andrea Mantegna

- Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt

- Anne Boleyn

- Anne Bradstreet

- Aretino, Pietro

- Ariosto, Ludovico

- Art and Science

- Art, German

- Art in Renaissance England

- Art in Renaissance Florence

- Art in Renaissance Siena

- Art in Renaissance Venice

- Art Literature and Theory of Art

- Art of Poetry

- Art, Spanish

- Art, 16th- and 17th-Century Flemish

- Art, 17th-Century Dutch

- Artemisia Gentileschi

- Ascham, Roger

- Askew, Anne

- Astell, Mary

- Astrology, Alchemy, Magic

- Augustinianism in Renaissance Thought

- Autobiography and Life Writing

- Avignon Papacy

- Bacon, Francis

- Banking and Money

- Barbaro, Ermolao, the Younger

- Barbaro, Francesco

- Baron, Hans

- Baroque Art and Architecture in Italy

- Barzizza, Gasparino

- Bathsua Makin

- Beaufort, Margaret

- Bellarmine, Cardinal

- Bembo, Pietro

- Benito Arias Montano

- Bernardino of Siena, San

- Beroaldo, Filippo, the Elder

- Bessarion, Cardinal

- Biondo, Flavio

- Bishops, 1550–1700

- Bishops, 1400-1550

- Black Death and Plague: The Disease and Medical Thought

- Boccaccio, Giovanni

- Bohemia and Bohemian Crown Lands

- Borgia, Cesare

- Borgia, Lucrezia

- Borromeo, Cardinal Carlo

- Bosch, Hieronymous

- Bracciolini, Poggio

- Brahe, Tycho

- Bruegel, Pieter the Elder

- Bruni, Leonardo

- Bruno, Giordano

- Bucer, Martin

- Budé, Guillaume

- Buonarroti, Michelangelo

- Burgundy and the Netherlands

- Calvin, John

- Camões, Luís de

- Cardano, Girolamo

- Cardinal Richelieu

- Carvajal y Mendoza, Luisa De

- Cary, Elizabeth

- Casas, Bartolome de las

- Castiglione, Baldassarre

- Catherine of Siena

- Catholic/Counter-Reformation

- Catholicism, Early Modern

- Cecilia del Nacimiento

- Cellini, Benvenuto

- Cervantes, Miguel de

- Charles V, Emperor

- China and Europe, 1550-1800

- Christian-Muslim Exchange

- Christine de Pizan

- Church Fathers in Renaissance and Reformation Thought, The

- Ciceronianism

- Cities and Urban Patriciates

- Civic Humanism

- Civic Ritual

- Classical Tradition, The

- Clifford, Anne

- Colet, John

- Colonna, Vittoria

- Columbus, Christopher

- Comenius, Jan Amos

- Commedia dell'arte

- Concepts of the Renaissance, c. 1780–c. 1920

- Confraternities

- Constantinople, Fall of

- Contarini, Gasparo, Cardinal

- Convent Culture

- Conversos and Crypto-Judaism

- Copernicus, Nicolaus

- Cornaro, Caterina

- Cosimo I de’ Medici

- Cosimo il Vecchio de' Medici

- Council of Trent

- Crime and Punishment

- Cromwell, Oliver

- Cruz, Juana de la, Mother

- Cruz, Juana Inés de la, Sor

- d'Aragona, Tullia

- Datini, Margherita

- Davies, Eleanor

- de Commynes, Philippe

- de Sales, Saint Francis

- de Valdés, Juan

- Death and Dying

- Decembrio, Pier Candido

- Dentière, Marie

- Des Roches, Madeleine and Catherine

- d’Este, Isabella

- di Toledo, Eleonora

- Dolce, Ludovico

- Donne, John

- Drama, English Renaissance

- Dürer, Albrecht

- du Bellay, Joachim

- Du Guillet, Pernette

- Dutch Overseas Empire

- Ebreo, Leone

- Edmund Campion

- Edward IV, King of England

- Elizabeth I, the Great, Queen of England

- Emperor, Maximilian I

- England, 1485-1642

- English Overseas Empire

- English Puritans, Quakers, Dissenters, and Recusants

- Environment and the Natural World

- Epic and Romance

- Europe and the Globe, 1350–1700

- European Tapestries

- Family and Childhood

- Fedele, Cassandra

- Federico Barocci

- Female Lay Piety

- Ferrara and the Este

- Ficino, Marsilio

- Filelfo, Francesco

- Fonte, Moderata

- Foscari, Francesco

- France in the 17th Century

- France in the 16th Century

- Francis Xavier, St

- Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros

- French Law and Justice

- French Renaissance Drama

- Fugger Family

- Galilei, Galileo

- Gallicanism

- Gambara, Veronica

- Garin, Eugenio

- General Church Councils, Pre-Trent

- Geneva (1400-1600)

- Genoa 1450–1700

- George of Trebizond

- Georges de La Tour

- Giambologna

- Ginés de Sepúlveda, Juan

- Giustiniani, Bernardo

- Góngora, Luis de

- Gournay, Marie de

- Greek Visitors

- Guarino da Verona

- Guicciardini, Francesco

- Guilds and Manufacturing

- Hamburg, 1350–1815

- Hanseatic League

- Henry VIII, King of England

- Herbert, George

- Hispanic Mysticism

- Historiography

- Hobbes, Thomas

- Holy Roman Empire 1300–1650

- Homes, Foundling

- Humanism, The Origins of

- Hundred Years War, The

- Hungary, The Kingdom of

- Hutchinson, Lucy

- Iconology and Iconography

- Ignatius of Loyola, Saint

- Inquisition, Roman

- Isaac Casaubon

- Isabel I, Queen of Castile

- Italian Wars, 1494–1559

- Ivan IV the Terrible, Tsar of Russia

- Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples

- Japan and Europe: the Christian Century, 1549-1650

- Jeanne d’Albret, queen of Navarre

- Jewish Women in Renaissance and Reformation Europe

- Jews and Christians in Venice

- Jews and the Reformation

- Jews in Amsterdam

- Jews in Florence

- Joan of Arc

- Jonson, Ben

- Joseph Justus Scaliger

- Juan de Torquemada

- Juana the Mad/Juana, Queen of Castile

- Kepler, Johannes

- King of France, Francis I

- King of France, Henri IV

- Kristeller, Paul Oskar

- Labé, Louise

- Landino, Cristoforo

- Last Wills and Testaments

- Laura Cereta

- Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Leoni, Leone and Pompeo

- Leto, Giulio Pomponio

- Letter Writing and Epistolary Culture

- Literature, French

- Literature, Italian

- Literature, Late Medieval German

- Literature, Penitential

- Literature, Spanish

- Locke, John

- Lorenzo de' Medici

- Lorenzo Ghiberti

- Louis XI, King of France

- Louis XIII, King of France

- Louis XIV, King of France

- Lucas Cranach the Elder

- Lucretius in Renaissance Thought

- Luther, Martin

- Machiavelli, Niccolo

- Macinghi Strozzi, Alessandra

- Malatesta, Sigismondo

- Manetti, Giannozzo

- Mantovano (Battista Spagnoli), Battista

- Manuel Chrysoloras

- Manuzio, Aldo

- Margaret Clitherow

- Margaret Fell Fox

- Margery Kempe

- Marinella, Lucrezia

- Marino Sanudo

- Marlowe, Christopher

- Marriage and Dowry

- Mary Stuart (Mary, Queen of Scots)

- Mary Tudor, Queen of England

- Masculinity

- Medici Bank

- Medici, Catherine de'

- Medici Family, The

- Mediterranean

- Memling, Hans

- Merici, Angela

- Milan, 1535–1706

- Milan to 1535

- Milton, John

- Mirandola, Giovanni Pico della

- Monarchy in Renaissance and Reformation Europe, Female

- Montaigne, Michel de

- More, Thomas

- Morone, Cardinal Giovanni

- Naples, 1300–1700

- Navarre, Marguerite de

- Netherlandish Art, Early

- Netherlands (Dutch Revolt/ Dutch Republic), The

- Netherlands, Spanish, 1598-1700, the

- Nettesheim, Agrippa von

- Newton, Isaac

- Niccoli, Niccolò

- Nicholas of Cusa

- Nicolas Malebranche

- Ottoman Empire

- Panofsky, Erwin

- Paolo Veronese

- Parr, Katherine

- Patronage of the Arts

- Perotti, Niccolò

- Persecution and Martyrdom

- Peter the Great, Tsar of Russia

- Petrus Ramus and Ramism

- Philip Melanchthon

- Philips, Katherine

- Piccolomini, Aeneas Sylvius

- Piero della Francesca

- Pierre Bayle

- Plague and its Consequences

- Platonism, Neoplatonism, and the Hermetic Tradition

- Poetry, English

- Pole, Cardinal Reginald

- Polish Literature: Baroque

- Polish Literature: Renaissance

- Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, The

- Political Thought

- Poliziano, Angelo

- Polydore Vergil

- Pontano, Giovanni Giovano

- Pope Innocent VIII

- Pope Nicholas V

- Pope Paul II

- Portraiture

- Poulain de la Barre, Francois

- Poverty and Poor Relief

- Prince Henry the Navigator

- Printing and the Book

- Printmaking

- Pulter, Hester

- Purity of Blood

- Quirini, Lauro

- Rabelais, François

- Reformation and Hussite Revolution, Czech

- Reformation and Wars of Religion in France, The

- Reformation, English

- Reformation, German

- Reformation, Italian, The

- Reformation, The

- Reformations and Revolt in the Netherlands, 1500–1621

- Renaissance, The

- Reuchlin, Johann

- Revolutionary England, 1642-1702

- Ricci, Matteo

- Richard III

- Rienzo, Cola Di

- Roman and Iberian Inquisitions, Censorship and the Index i...

- Ronsard, Pierre de

- Roper, Margeret More

- Royal Regencies in Renaissance and Reformation Europe, 140...

- Rubens, Peter Paul

- Russell, Elizabeth Cooke Hoby

- Russia and Muscovy

- Ruzante Angelo Beolco

- Saint John of the Cross

- Saints and Mystics: After Trent

- Saints and Mystics: Before Trent

- Salutati, Coluccio

- Sandro Botticelli

- Sarpi, Fra Paolo

- Savonarola, Girolamo

- Scandinavia

- Scholasticism and Aristotelianism: Fourteenth to Seventeen...

- Schooling and Literacy

- Scientific Revolution

- Scève, Maurice

- Sephardic Diaspora

- Sforza, Caterina

- Sforza, Francesco

- Shakespeare, William

- Ships/Shipbuilding

- Sidney Herbert, Mary, Countess of Pembroke

- Sidney, Philip

- Simon of Trent

- Sir Robert Cecil

- Sixtus IV, Pope

- Skepticism in Renaissance Thought

- Slavery and the Slave Trade, 1350–1650

- Southern Italy, 1500–1700

- Southern Italy, 1300–1500

- Spanish Inquisition

- Spanish Islam, 1350-1614

- Spenser, Edmund

- Sperone Speroni

- Spinoza, Baruch

- Stampa, Gaspara

- Stuart, Elizabeth, Queen of Bohemia

- Switzerland

- Tarabotti, Arcangela

- Tasso Torquato

- Tell, William

- Teresa of Avila

- Textiles: 1400 to 1700

- The Casa of San Giorgio, Genoa

- The Radical Reformation

- The Sack of Rome (1527)

- Thirty Years War, The

- Tornabuoni, Lucrezia

- Trade Networks

- Tragedy, English

- Translation

- Transylvania, The Principality of

- Traversari, Ambrogio

- Universities

- Valeriano, Pierio

- Valla, Lorenzo

- van Eyck, Jan

- van Schurman, Anna Maria

- Vasari, Giorgio

- Vega, Lope de

- Vegio, Maffeo

- Venice, Maritime

- Vergerio, Pier Paolo, The Elder

- Vermeer, Johannes

- Vernacular Languages and Dialects

- Vida, Marco Girolamo

- Virgil in Renaissance Thought

- Visitors, Italian

- Vives, Juan Luis

- Walter Ralegh

- War and Economy, 1300-1600

- Warfare and Military Organizations

- Weyden, Rogier van der

- Wolsey, Thomas, Cardinal

- Women and Learning

- Women and Medicine

- Women and Science

- Women and the Book Trade

- Women and the Reformation

- Women and the Visual Arts

- Women and Warfare

- Women and Work: Fourteenth to Seventeenth Centuries

- Women Writers in Ireland

- Women Writers of the Iberian Empire

- Women Writing in Early Modern Spain

- Women Writing in English

- Women Writing in French

- Women Writing in Italy

- Wroth, Mary

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.180.204]

- 81.177.180.204

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The English Reformation began with Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547 CE) and continued in stages over the rest of the 16th century CE. The process witnessed the break away from the Catholic Church headed by the Pope in Rome.The Protestant Church of England was thus established and the English monarch became its supreme head. Other consequences included the dissolution of the monasteries, the ...

Catherine of Aragon. Catherine of Aragon was the first wife of Henry VIII, the King of England, and the first ruler who was a part of the English Reformation. She married Henry VIII after her previous husband and Henry's older brother, Arthur, died before ascending to the English throne. 9 Thus, she became the Queen of England in 1509 ...

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England was forced by its monarchs and elites to break away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Reformation , a religious and political movement that affected the practice of Christianity in Western and ...

"The Recent Historiography of the English Reformation" is an essay written by Christopher Haigh that appears in The English Reformation Revised. It begins by stating that the English Reformation was a long and complex process with many revisionist disputes over the causes and chronology of the new religious development.54 Haigh says it ...

The English Reformation. By Professor Andrew Pettegree. Last updated 2011-02-17. Despite the zeal of religious reformers in Europe, England was slow to question the established Church. During the ...

Reformation was a historic movement that transformed the Western church and society in the 16th century. Learn about its definition, history, summary, reformers, and facts from Britannica, the trusted source of knowledge. Explore how Reformation challenged the authority of the pope, sparked the rise of Protestantism, and shaped the modern world.

October 2002. Unleashed in the early sixteenth century, the Reformation put an abrupt end to the relative unity that had existed for the previous thousand years in Western Christendom under the Roman Catholic Church. The Reformation, which began in Germany but spread quickly throughout Europe, was initiated in response to the growing sense of ...

Introduction. The English Reformation produced a vibrant literature, which entertained and consoled readers and audiences, and attempted to influence the direction of religious change. Scholars long overlooked this literature because they clung to assumptions of canon-formation by which the medieval poet Chaucer and his imitators were thought ...

1 The recent historiography of the English Reformation; 2 Church courts and the Reformation in the diocese of Chichester, 1500-58; ... in ready-mixed meals needing only to be warmed in the moderate oven of a mediocre essay or lecture: with such fast-foods to hand, the over-worked cook need not formulate his own recipe or cope with his own ...

Footnote 2 England's Long Reformation, a major collection of essays edited by Nicholas Tyacke and published in 1998, ... Reformation to the major religious upheavals of sixteenth-century England and Europe and almost none now confine the English Reformation to the few decades between 1529 and 1559. As the work of Anne Hudson on Wycliffite ...

The nine essays (one printed here for the first time) provide detailed studies of particular problems in Reformation history, and general surveys of the progress of religious change. The new Conclusion tries to plug some of the remaining gaps, and suggests how the Reformation came to divide the English nation.

Essay on The English Reformation. Though there was no driving force like Luther, Zwingli or Calvin during the English Reformation, it succeeded because certain people strived for political power and not exactly for religious freedom. People like Queen Elizabeth I and Henry VIII brought the Reformation in England much success, however their ...

Introduction Bede, History of the English Church, translated by Thomas Stapleton, 31 (1565).Full excerpt below. The English Reformation was part of a European-wide phenomenon to reform the church which began in 1517 when legend has it that the German monk and theologian Martin Luther nailed 95 theses (propositions for discussion) to the door of the castle church at Wittenberg to be debated ...

7 See 'Focal point on the Protestant Reformation and the middle ages', Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte/Archiv for Reformation History, 101 (2010), esp. Mark Greengrass and Matthew Phillpott, 'John Bale, John Foxe, and the Reformation of the English past', pp. 275-87; Felicity Heal, 'Appropriating history: Catholic and Protestant polemics and the national past', in Paulina ...

See also Ann Hughes's essay in this issue, and the concerns raised by Peter Marshall in explaining the English Ref-ormation "in any of its long, longer, and longest variants": "(Re)Defining the English Reformation," 568-9. ... These comments, published over twenty years ago, preserve a historiographical moment when the notion of ...

The notable part played by women in the Reformation has rarely been given its due recognition in English historical studies. In recent years Professor Wallace Notestein has written with characteristic authority and grace on 'The English Woman, 1580-1650,' but one does not learn from this essay that the English women of this age had any religious propensities at all.

The popular perspective on the English Reformation is often superficial, without consideration of the political and ecclesiastic forces that formed the events of the Reformation as well as the results of it. ... Steven Foster January 2013 Historiography Essay: The English Reformation The recent English Reformation scholarship has seen a shift ...

English Renaissance poetry is customarily divided chronologically in two ways. Scholars distinguish between either the 16th and 17th centuries or between Tudor (1485-1603) and Stuart (1603-1649) periods. The division between Tudor and Stuart poetry is useful, for instance, in tracing how different poetic concerns, such as satire and ...

The fact that both the English Reformation (which took place in England) and the Protestant Reformation (which took place in the rest of continental Europe) broke away from the Pope and the ...

The Protestant and English reformation were both reforms that took place in the 16th century against the Roman Catholic Church. Comparatively these reformations are alike and different in some sense. For example, Two leaders led these reforms and went against the church's beliefs for different purposes.For personal reasons , King Henry VIII ...

English Reformations. Patrick Collinson, Patrick Collinson. Search for more papers by this author. Patrick Collinson, Patrick Collinson. Search for more papers by this author. Book Editor(s): Michael Hattaway, Michael Hattaway. Search for more papers by this author. First published: 01 January 2003.

4. Elton, G. R., Reform and Reformation: England, 1508-1558 (London, 1977), 371 Google Scholar. 5. "Revisionism" became firmly established as the appropriate term of art with the publication of a volume of essays edited by Haigh, Christopher: The English Reformation Revised (Cambridge, 1987) CrossRef Google Scholar. 6.

The evidence analysed in this investigation suggests that Thomas Cranmer established various aims to help further the English Reformation. He met with both successes and failures. The extent to which his successes outweighed his failures will determine how important he was for the progress of the Reformation. A careful analysis will be made of ...