A brief history of capital punishment in Britain

Between the late 17th and early 19th century, Britain’s ‘Bloody Code’ made more than 200 crimes – many of them trivial – punishable by death. Writing for History Extra , criminologist and historian Lizzie Seal considers the various ways in which capital punishment has been enforced throughout British history and investigates the timeline to its abolition in 1965

- Share on facebook

- Share on twitter

- Share on whatsapp

- Email to a friend

British forms of punishment

From as early as the Anglo-Saxon era, right up to 1965 when the death penalty was abolished, the main form of capital punishment in Britain was hanging. Initially, this involved placing a noose around the neck of the condemned and suspending them from the branch of a tree. Ladders and carts were used to hang people from wooden gallows, which entailed death by asphyxiation.

In the late 13th century the act of hanging morphed into the highly ritualised practice of ‘drawing, hanging and quartering’ – the severest punishment reserved for those who had committed treason. In this process, ‘drawing’ referred to the dragging of the condemned to the place of execution. After they were hanged, their body was punished further by disembowelling, beheading, burning and ‘quartering’ – cutting off the limbs. The perpetrator’s head and limbs were often publicly displayed following the execution.

Later, the ‘New Drop’ gallows – first used at London’s Newgate Prison in 1783 – could accommodate two or three prisoners at a time and were constructed on platforms with trapdoors through which the condemned fell. The innovation of the ‘long drop’ [a method of hanging which considered the weight of the condemned, the length of the drop and the placement of the knot] in the later 19th century caused death by breaking the condemned’s neck, which was deemed quicker and less painful than strangling.

Burning at the stake was another form of capital punishment, used in England from the 11th century for heresy and the 13th century for treason. It was also used specifically for women convicted of petty treason (the charge given for the murder of her husband or employer). Though hanging replaced burning as the method of capital punishment for treason in 1790, the burning of those suspected of witchcraft was practiced in Scotland until the 18th century.

For other – perhaps luckier – souls and for those of noble birth who were condemned to die, execution by beheading (which was considered the least brutal method of execution) was used until the 18th century. Death by firing squad was also used as form of execution by the military.

More like this

- A brief history of witches by Suzannah Lipscomb

- Were ducking stools ever used as punishment for crimes other than witchcraft during the Middle Ages?

- Witchcraft through the ages (podcast)

The ‘Bloody Code’

Britain’s ‘Bloody Code’ was the name given to the legal system between the late-17th and early-19th century which made more than 200 offences – many of them petty – punishable by death. Statutes introduced between 1688 and 1815 covered primarily property offences, such as pickpocketing, cutting down trees and shoplifting.

Nevertheless, despite the ‘mushrooming’ of capital crimes, fewer people were actually executed in the 18th century than during the preceding two centuries. This paradox can be explained by the specificity of the capital statutes, which meant it was often possible to convict people of lesser crimes. For example, theft of goods above a certain value carried the death penalty, so the jury could circumvent this by underestimating the value of said goods.

Certain regions with more autonomy, including Scotland, Wales and Cornwall, were particularly reluctant to implement the Bloody Code and, by the 1830s, executions for crimes other than murder had become extremely rare.

Vocal critics of the Bloody Code included early 19th-century MP Sir Samuel Romilly, who worked for its reform. A barrister by profession, he was appointed solicitor general [a senior law officer of the crown] and entered the House of Commons in 1806. He succeeded in repealing the death penalty for some minor crimes and in ending the use of disembowelling convicted criminals while alive. Later, liberal MP William Ewart brought bills which abolished hanging in chains (in 1834) and ended capital punishment for cattle stealing and other minor offences (in 1837).

In the 1840s, prominent figures including writers Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray highlighted what they believed to be the brutalising effects of public hanging. Far from encouraging solemnity, hangings were entertaining spectacles that whipped up the crowd’s passions, they argued – and the presence of the crowd was a potential source of unruliness. Dickens attended the executions of Maria and Frederick Manning at Horsemonger Lane Gaol, south London, in 1849. The pair had been convicted of the murder of a customs official named Patrick O’Connor, whom they had killed and buried under the kitchen floorboards at their London home. Their case was nicknamed by the press: “the Bermondsey Horror”. Dickens later wrote to The Times expressing his distaste for the “levity of the immense crowd” and the “thieves, low prostitutes, ruffians, and vagabonds of every kind” who flocked there to watch the execution.

- Surviving the gallows: the Georgian hangings that didn't go to plan

- Was there ever an execution where rain saved someone from being burned at the stake?

There was also an ongoing, more general campaign for the abolition of the death penalty on moral and humanitarian grounds. Many campaigners argued that the infliction of pain was interpreted as corrupting and uncivilised, and that the death penalty did not allow for the redemption of the criminal.

In 1861, the death penalty was abolished for all crimes except murder; high treason; piracy with violence; and arson in the royal dockyards. The ending of public execution in 1868 (by the Capital Punishment Act) further dampened abolitionism. But although anti-death penalty sentiment was not widespread, certain cases aroused public sympathy, especially those of women. Such cases included Florence Maybrick, who was reprieved from the gallows in 1889 amid doubts about the strength of evidence against her for poisoning her husband. Meanwhile, in 1899 a press campaign was launched on behalf of Mary Ann Ansell, who was accused of murdering her sister, which highlighted concerns about her mental soundness. Ansell was nevertheless hanged that year.

- What is gaol fever and how was it caused and spread?

- Murder, conspiracy and execution: six centuries of scandalous royal deaths

- The astronomer and the witch: Johannes Kepler’s fight to save his mother from execution

Capital punishment in the 20th century

From the first half of the 20th century, legislation further limited the application of capital punishment. The Infanticide Act of 1922 made the murder of a newborn baby by its mother a separate offence from murder and one which was not a capital crime. The death sentence for pregnant women was abolished in 1931. Both these changes brought the law into line with long-existing practice of not executing pregnant women or women convicted of infanticide, as did abolishing the death penalty for under-18s in 1933: no-one below this age had been executed in Britain since 1887.

Campaigns for the abolition of the death penalty once again gathered speed in the 1920s, in part galvanised by the execution of Edith Thompson in 1923. Thompson and her lover, Freddie Bywaters, were hanged for the murder of Edith’s husband, Percy. The case was controversial because there was doubt surrounding the veracity of the evidence against Thompson (Bywaters had carried out the murder by stabbing Percy), and also because there were rumours that Edith’s hanging had been botched.

- America’s ‘Mrs Holmes’: how one woman took on the cases the NYPD couldn’t solve

- How many executions was Henry VIII responsible for?

Later that year (1923) the Howard League – a penal reform group that campaigned for humane prison conditions and for a reformatory approach to criminals – turned its attention to the abolition of the death penalty. The National Council for the Abolition of the Death Penalty joined the campaign in 1925. Then, in 1927 the Labour Party published its abolitionist ‘Manifesto on Capital Punishment’ under the leadership of Ramsay MacDonald.

A few years later, in the 1930s, a wealthy businesswoman named Violet van der Elst became a well-known campaigner for abolition. She argued that capital punishment was uncivilised and harmful to society and that it was applied disproportionately to poor people. Her campaigns included organising the flight of aeroplanes trailing banners over the respective prison on the morning of an execution while she addressed crowds outside the prison gates through a loudhailer and leading them in prayer and song.

The first full parliamentary debate on capital punishment in the 20th century took place in 1929 and resulted in the establishment of a Select Committee on the issue. The committee reported its findings in 1930 and advocated an experimental five-year suspension of the death penalty; however, the report was largely ignored, as the issue was deemed to be low on the political agenda as other social issues took priority.

Calls for post-war reform

After the end of the Second World War in 1945, capital punishment became an increasingly prominent political and social issue. The election of the Labour government in 1945 was highly significant, as a higher proportion of Labour MPs supported abolition than Conservatives. Sydney Silverman, Labour MP for Nelson and Colne, led the parliamentary campaign to end the death penalty and attempted (ultimately unsuccessfully) to get abolition included in the Criminal Justice Act of 1948. However, the Act did end penal servitude, hard labour and flogging, and established a reformist system for punishing and treating offenders.

During this period of increased attention to capital punishment, certain contentious cases generated public disquiet. The executions of John Christie and Derek Bentley in 1953, to name but two, were pivotal.

The first case concerns the murder of a woman and child: in 1950, Timothy Evans, a 25-year-old van driver originally from Merthyr Tydfil and living in London, was hanged for murdering his wife, Beryl, and their baby daughter, Geraldine. It remained a relatively low-profile case until 1953, when the remains of seven women were found at 10 Rillington Place, a multi-occupancy house in Notting Hill. The home, it transpired, had been shared concurrently by Evans and his family with a man named John Christie, whom Evans had insisted throughout his trial had been responsible for the murder of Beryl and Geraldine. Following Christie’s conviction and execution in 1953, it seemed indisputable that Evans had been innocent.

The second case concerns that of 19-year-old Derek Bentley, who was hanged in January 1953 for the murder of a police officer, Sidney Miles. In fact it was his friend Christopher Craig who had shot Miles during the pair’s bungled break-in in Croydon, Surrey, while Bentley was detained by another officer. However, Craig was only 16 years old at the time of the crime and was therefore ineligible for the death penalty. Doubts about the justice of Bentley’s execution were intensified by his reported low intelligence and his tender age of 19 years. Bentley was posthumously pardoned in 1998.

- Historical fiction and a US murder scandal (podcast)

- Arsenic: a brief history of Agatha Christie’s favourite murder weapon

- The Victorians’ grisly fascination with murder (exclusive to The Library)

Ruth Ellis, the last woman to be executed in Britain, is rightly remembered as having had an important influence upon views on the death penalty. Ellis was hanged in 1955 for the murder of her boyfriend, David Blakely, whom she shot outside a pub in Hampstead, London. Blakely had been violent and abusive towards Ellis and there was much public sympathy for the emotional strain that she had been under at the time. The murder was widely seen as a ‘crime of passion’ and therefore understandable, if not necessarily excusable.

- Ruth Ellis and the hanging that rocked a nation

- Ruth Ellis: the last woman to be hanged in Britain (podcast)

Until then women had almost always been reprieved from the death penalty, so there was widespread shock when Ellis was not. Her case attracted a huge amount of press attention and remains a highly-significant case connected to the abolition of the death penalty today, due to the emotional debate her case generated and its impact on British sentiment in the 1950s.

Labour MP Sydney Silverman’s continued attempts to pass abolitionist legislation in 1956 foundered, but the following year the Homicide Act of 1957 restricted the death penalty’s application to certain types of murder, such as in the furtherance of theft or of a police officer. Up until this point, death had been the mandatory sentence for murder and could only be mitigated via reprieve – a political rather than legal decision. This change in legislation reduced hangings to three or four per year, but capital punishment still remained highly contested.

On 13 August 1964, Peter Allen and Gwynne Evans became the last people to be hanged in Britain. They had murdered a taxi driver and doing so “in the furtherance of theft” made it a capital crime.

In 1965, the Murder (Abolition of the Death Penalty) Act suspended the death penalty for an initial five-year period and was made permanent in 1969. The act had originally started as a private members’ bill introduced by Silverman and was sponsored by MPs from all three main parties, including Michael Foot and Shirley Williams from Labour; Conservative Chris Chataway and Liberal Jeremy Thorpe.

Capital punishment was in 1998 abolished for treason and piracy with violence, making Britain fully abolitionist, both in practice and in law, and enabling ratification of the European Convention on Human Rights.

Lizzie Seal is a reader in criminology at the University of Sussex. Her books include Capital Punishment in 20th-Century Britain: Audience, Justice, Memory (Routledge, 2014).

This article was first published by History Extra in March 2018

JUMP into SPRING! Get your first 6 issues for £9.99

+ FREE HistoryExtra membership (special offers) - worth £34.99!

Sign up for the weekly HistoryExtra newsletter

Sign up to receive our newsletter!

By entering your details, you are agreeing to our terms and conditions and privacy policy . You can unsubscribe at any time.

JUMP into SPRING! Get your first 6 issues for

USA Subscription offer!

Save 76% on the shop price when you subscribe today - Get 13 issues for just $45 + FREE access to HistoryExtra.com

HistoryExtra podcast

Listen to the latest episodes now

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Reviewer Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Journal of Human Rights Practice

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Imperatives, acknowledgements.

- < Previous

A Factful Perspective on Capital Punishment

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

David T Johnson, A Factful Perspective on Capital Punishment, Journal of Human Rights Practice , Volume 11, Issue 2, July 2019, Pages 334–345, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhuman/huz018

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Substantial progress has been made towards worldwide abolition of capital punishment, and there are good reasons to believe that more progress is possible. Since 2000, the pace of abolition has slowed, but by several measures the number of executions in the world has continued to decline. Several causes help explain the decline, including political leadership from the front and an increased tendency to regard capital punishment as a human rights issue rather than as a matter of domestic criminal justice policy. There are significant obstacles in the movement to eliminate state killing in the world, but some strategies could contribute to additional decline in the years to come.

People tend to notice the bad more than the good, and this ‘negativity instinct’ is apparent when it comes to capital punishment ( Rosling et al. 2018 : 48). For example, two decades ago, Leon Radzinowicz (1999 : 293), the founder of Cambridge University’s Institute of Criminology, declared that he ‘did not expect any substantial further decrease’ in the use of capital punishment because ‘most of the countries likely to embrace the abolitionist cause’ had already done so. In more recent years, other analysts have claimed that the human rights movement is in crisis, and that ‘nearly every country seems to be backsliding’ ( Moyn 2018 ). If this assessment is accurate, it should be cause for concern for opponents of capital punishment because a heightened regard for human rights is widely regarded as the key cause of abolition since the 1980s ( Hood and Hoyle 2009 ).

To be sure, everything is not fine with respect to capital punishment. Most notably, the pace of abolition has slowed in recent years, and executions have increased in several countries, including Iran and Taiwan (in the 2010s), Pakistan (2014–15), and Japan (2018). But too much negativity will not do. I adopt a factful perspective about the future of capital punishment: I see substantial progress toward worldwide abolition, and this gives me hope that further progress is possible ( Rosling et al. 2018 ).

This article builds on Roger Hood’s seminal study of the movement to abolish capital punishment, which found ‘a remarkable increase in the number of abolitionist countries’ in the 1980s and 1990s ( Hood 2001 : 331). It proceeds in four parts. Section 1 shows that in the two decades or so since 2000 the pace of abolition has slowed but not ceased, and the total number of executions in the world has continued to decline. Section 2 explains how death penalty declines have been achieved in recent years. Section 3 identifies obstacles in the movement toward elimination of state killing in the modern world. And Section 4 suggests some priorities and strategies that could contribute to additional decline in the death penalty in the third decade of the third millennium.

These examples exclude estimates for the People’s Republic of China, which does not disclose reliable death penalty figures, but which probably executes more people each year than the rest of the world combined.

Table 1 displays the number of countries with each of these four death penalty statuses in five years: 1988, 1995, 2000, 2007, and 2017. Overall, the percentage of countries to retain capital punishment has declined by half over that period, from 56 per cent in 1988 to 28 per cent in 2017. But Table 2 shows that the pace of abolition has slowed since the 1990s, when 37 countries abolished. By comparison, only 23 countries abolished in the 2000s, with 11 more countries abolishing in the first eight years of the 2010s. The pace of abolition has declined partly because much of the lowest hanging fruit has already been picked.

Number of abolitionist and retentionist countries, 1988–2017

Note : Figures in parentheses show the percentage of the total number of countries in the world in that year.

Sources : Hood 2001 : 334 (for 1988, 1995, and 2000); Amnesty International annual reports (for 2007 and 2017).

Number of Countries That Abolished the Death Penalty by Decade, 1980s – 2010s

Sources : Death Penalty Information Center; Amnesty International annual reports.

Table 3 uses Hood’s figures for 1980 to 1999 ( Hood 2001 : 335) and figures from Hands Off Cain and Amnesty International to report the estimated number of executions and death sentences worldwide from 1980 to 2017. Because several countries (including China, the world’s leading user of capital punishment) do not disclose reliable death penalty statistics, the figures in Table 3 cannot be considered precise measures of death sentencing and execution trends over time, but the numbers do suggest recent declines. For instance, the average number of death sentences per year in the 2010s (2,220) was less than half the annual average for the 2000s (4,576). Similarly, the average number of executions per year in the 2010s (867) was less than half the annual average for the 2000s (1,762). Moreover, while the average number of countries per year to impose a death sentence remained fairly flat in the four decades covered in Table 3 (58 countries in the 1980s, 68 in the 1990s, 56 in the 2000s, and 58 in the 2010s), the average number of countries per year which carried out an execution declined by about one-third, from averages of 37 countries in the 1980s and 35 countries in the 1990s, to 25 countries in the 2000s and 23 countries in the 2010s. In short, fewer countries are using capital punishment, and fewer people are being condemned to death and executed.

Number of death sentences and executions worldwide, 1980–2017

Notes : (a) The numbers of reported and recorded death sentences and executions are minimum figures, and the true totals are substantially higher. (b) In 2009, Amnesty International stopped publishing estimates of the minimum number of executions per year in China.

Sources : Hood 2001 : 335 (1980–1999); Hands Off Cain (2001); Amnesty International annual reports (2002–2017).

In 2001, Hood (2001 : 336) reported that 26 countries had executed at least 20 persons in the five-year period 1994–1998. Table 4 compares those figures with figures for the same 26 countries in 2013–2017, and it also presents the annual rate of execution per million population for each country (in parentheses). The main pattern is striking decline. In 2009, Amnesty International stopped publishing estimates of the minimum number of executions per year in the People’s Republic of China, so trend evidence from that source is unavailable, but other sources indicate that executions in China have declined dramatically in the past two decades, from 15,000 or more per year in the late 1990s and early 2000s ( Johnson and Zimring 2009 : 237), to approximately 2,400 in 2013 ( Grant 2014 ) and 2,000 or so in 2016. Of the other 25 countries in Hood’s list of heavy users of capital punishment in the 1990s, 11 saw executions disappear (Ukraine, Turkmenistan, Russia, Kazakhstan, Congo, Sierra Leone, Kyrgyzstan, South Korea, Libya, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe), eight had the execution rate decline by half or more (USA, Nigeria, Singapore, Belarus, Taiwan, Yemen, Jordan, Afghanistan), and two experienced more modest declines (Saudi Arabia and Egypt). Altogether, 22 of the 26 heavy users of capital punishment in the latter half of the 1990s have experienced major declines in executions. Of the remaining four countries, one (Japan) saw its execution rate remain stable until executions surged when 13 former members of Aum Shinrikyo were hanged in July 2018 (for murders and terrorist attacks committed in the mid-1990s), while three (Iran, Pakistan, and Viet Nam) experienced sizeable increases in both executions and execution rates.

Executions and execution rates by country, 1994–1998 and 2013–2017

a The figure of 429 executions for Viet Nam is for the three years from August 2013 to July 2016.

Notes: Countries reported to have executed at least 20 persons in 1994–1998, and execution figures for the same countries in 2013–2017 (with annual rates of execution per million population for both periods in parentheses).

As explained in the text, in addition to the 26 countries that appeared in Table 3 of Hood (2001 : 336), India had at least 24 judicial executions in 1994–1998, Indonesia had four, and Iraq had an unknown number. The comparable figures for these countries in 2013–2017 (with the execution rate per million population in parentheses) are India = 2 (0.0003), Indonesia = 23 (0.09), and Iraq = 469 (2.78).

Sources : Hood 2001 : 336 (1994–1998); Amnesty International (2013–2017); the Death Penalty Database of the Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide (for India, Indonesia, and Iraq); Johnson and Zimring 2009 : 430 (for India 1994–1998).

The execution rate increases in Table 4 are striking but exceptional. In Iran, the fourfold increase in the execution rate gives it the highest per capita execution rate in the world for 2013–2017, with 6.68 executions per million population per year. This is approximately four times higher than the estimated execution rate for China (1.5) in the same period. The increase in Viet Nam is also fourfold, from 0.38 executions per million population per year to 1.5, while the increase in Pakistan is tenfold, from 0.05 to 0.49. Nonetheless, Viet Nam’s substantially increased execution rate in the 2010s would not have ranked it among the top ten executing nations in the 1990s, while Pakistan’s increased rate in the 2010s would not have ranked it among the top 15 nations in the 1990s. Even among the heaviest users of capital punishment, times have changed.

At least two countries that did not appear on Hood’s heavy user list for the 1990s executed more than 20 people in 2013–2017. The most notable newcomer is Iraq, which executed at least 469 persons in this five-year period, with an execution rate of 2.78 per million population per year. And then there is Indonesia. In the five years from 1994 to 1998, this country (with the world’s largest Muslim population) executed a total of four people, while in 2013–2017 the number increased to 23, giving it an execution rate of 0.09 per year per million population—about the same as the (low) execution rates in Japan and Taiwan.

When Iraq and Indonesia are added to the heavy user list for 2013–2017, only five countries out of 28 have execution rates that exceed one execution per year per million population, giving them death penalty systems that can be deemed ‘operational’ in the sense that ‘judicial executions are a recurrent and important part’ of their criminal justice systems ( Johnson and Zimring 2009 : 22). By contrast, in 1994–1998, 14 of these 28 countries had death penalty systems that were ‘operational’.

India is a country with a large population that does not appear on the frequent executing list for either the 1990s or the 2010s. In 2013–2017, this country of 1.3 billion people executed only two people, giving it what is probably the lowest execution rate (0.0003) among the 56 countries that currently retain capital punishment. India has long used judicial execution infrequently, but its police and security forces continue to kill in large numbers. In the 22 years from 1996 through 2017, India’s legal system hanged only four people, giving it an annual rate of execution that is around 1/25,000th the rate of executions in China. But over the same period, India’s police and security forces have killed thousands illegally and extrajudicially, many in ‘encounters’ that officials try to justify with the lie that the bad guy fired first.

Two fundamental forces have been driving the death penalty down in recent decades ( Johnson and Zimring 2009 : 290–304). First, while prosperity is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for abolition, economic development does tend to encourage declines in judicial execution and steps toward the cessation of capital punishment. Second, the general political orientation of government often has a strong influence on death penalty policy, at both ends of the execution spectrum. High-execution rate nations tend to be authoritarian, as in China, Viet Nam, North Korea, Singapore, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Iraq. Conversely, low-execution rate nations tend to be democracies with institutionalized limits on governmental power, as in most of the countries of Europe and in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, South Korea, and India. Of course, these are tendencies, not natural laws. Exceptions exist, including the USA at the high end of the execution spectrum, and Myanmar and Nepal at the low end.

In addition to economic development and democratization, concerns about wrongful convictions and the execution of innocents have made some governments more cautious about capital punishment. In the USA, for example, the discovery of innocence has led to historic shifts in public opinion and to sharp declines in the use of capital punishment by prosecutors and juries across the country ( Baumgartner et al. 2008 ; Garrett 2017 ). In China, too, wrongful convictions and executions help explain both declines in the use of capital punishment and legal reforms of the institution ( He 2016 ).

The question of capital punishment is fundamentally a matter of human rights, not an isolated issue of criminal justice policy.

Death penalty policy should not be governed by national priorities but by adherence to international human rights standards.

Since capital punishment is never justified, a national government may demand that other nations’ governments end executions. ( Zimring 2003 : 27)

As the third premise of this orthodoxy suggests, political pressure has contributed to the decline of capital punishment. This influence has been especially striking in Europe, where abolition of capital punishment is an explicit and absolute condition for becoming a member of the European Union. In other countries, too, from Singapore and South Korea to Rwanda and Sierra Leone, the missionary zeal of European governments committed to abolition has led to the elimination of capital punishment or to major declines in its usage.

Political leadership has also fostered the death penalty’s decline. There are few iron rules of abolition, but one seems to be that when the death penalty is eliminated, it invariably happens despite the fact of majority public support for the institution at the time of abolition. This—‘leadership from the front’—is such a common pattern, and public resistance to abolition is so stubborn, that some analysts believe ‘the straightest road to abolition involves bypassing public opinion entirely’ ( Hammel 2010 : 236). There appear to be at least two political circumstances in which the likelihood of leadership from the front rises and the use of capital punishment falls ( Zimring 2003 : 22): after the collapse of an authoritarian government, when new leaders aim to distance themselves from the repressive practices of the previous regime (as in West Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Romania, Cambodia, and Timor Leste); and after a left-liberal party gains control of government (as in Austria, Great Britain, France, South Korea, and Taiwan).

Although use of the death penalty continues to decline, there are countervailing forces that continue to present obstacles to abolition, as they have for decades. First and foremost, there is an argument about national sovereignty made by many states, that death penalty policy and practice are not human rights issues but rather matters of criminal justice policy that should be decided domestically, according to the values and traditions of each individual country. There is the role of religion—especially Islamic beliefs, where in some countries and cultures it is held that capital punishment must not be opposed because it has been divinely ordained. There are claims that capital punishment deters criminal behaviour and drug trafficking, though there is little evidence to support this view ( National Research Council 2012 ; Muramatsu et al. 2018 ). And there is the continued use of capital punishment in the USA, which helps to legitimate capital punishment in other countries ( Hood 2001 : 339–44).

The death penalty also survives in some places because it performs welcome functions for some interests. For instance, following the Arab Spring movements of 2010–2012, Egypt and other Middle Eastern governments employed capital punishment against many anti-government demonstrators and dissenters. In other retentionist countries, capital punishment has little to do with its instrumental value for government and crime control and much to do with the fact that it is ‘productive, performative, and generative—that it makes things happen—even if much of what happens is in the cultural realm of death penalty discourse rather than the biological realm of life and death’ or the penological realms of retribution and deterrence ( Garland 2010 : 285). For elected officials, the death penalty is a political token to be used in electoral contests. For prosecutors and judges, it is a practical instrument that enables them to harness the rhetorical power of death in the pursuit of professional objectives. For the mass media, it is an arena in which dramas can be narrated about the human condition. And for the onlooking public, it is a vehicle for moral outrage and an opportunity for prurient entertainment.

In addition to these long-standing obstacles to abolition, several other impediments have emerged in recent years. Most notably, as populism spreads ( Luce 2017 ) and democracy declines in many parts of the world ( Levitsky and Ziblatt 2018 ), an ‘anti-human rights agenda’ is forcing human rights proponents to rethink their assumptions and re-evaluate their strategies ( Alston 2017 ). Much of the new populist threat to democracy is linked to post-9/11 concerns about terrorism, which have been exploited to justify trade-offs between democracy and security. Of course, we are not actually living in a new age of terrorism. If anything, we have experienced a decline in terrorism from the decades in which it was less of a big deal in our collective consciousness ( Pinker 2011 : 353). But emotionally and rhetorically, terrorism is very much a big deal in the present moment, and the cockeyed ratio of fear to harm that is fostered by its mediated representations has been used to buttress support for capital punishment in many countries, including the USA (the Oklahoma City bombings in 1995), Japan (the sarin gas attacks of 1994 and 1995), China (in Xinjiang and Tibet), India (the Mumbai attacks of 1993 and 2008 and the 2001 attack on the Parliament in New Delhi), and Iraq (where executions surged after the post-9/11 invasion by the USA, and where most persons executed have been convicted of terrorism). More broadly, the present political resonance of terrorism has resulted in some abolitionist states assisting with the use of capital punishment in retentionist nations ( Malkani 2013 ).

Some analysts believe that the ‘abolition of capital punishment in all countries of the world will ensure that the killing of citizens by the state will no longer have any legitimacy and so even more marginalize and stigmatize extra-judicial executions’ ( Hood and Hoyle 2008 : 6). Others claim that the abolition of capital punishment is ‘one of the great, albeit unfinished, triumphs of the post-Second World War human rights movement’ ( Hodgkinson 2004 : 1). But states kill extrajudicially too, and sometimes the scale so far exceeds the number of judicial executions that death penalty reductions and abolitions seem like small potatoes. The most striking example is occurring under President Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines: thousands of extrajudicial executions in a country that abolished capital punishment (for the second time!) in 2006.The case of the Philippines illustrates a pattern that has been seen before and will be seen again in polities with weak law, strong executives, and fearful and frustrated citizens ( Johnson and Fernquest 2018 ). State killing often survives and sometimes thrives after capital punishment is abolished (as in Mexico, Brazil, Nepal, and Cambodia, among other countries). And in countries where capital punishment has not been abolished, extrajudicial executions are frequently carried out even after the number of judicial executions has fallen to near zero (as in Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, and Thailand).

Despite these obstacles to abolition, the decline of capital punishment seems likely to continue in the years to come. The trajectory of this institution is shaped by political and cultural processes over which human rights practices have little influence ( Garland 2010 : Chapter 5), but priorities and strategies do matter. In this section I suggest five imperatives for the future.

First, opponents of capital punishment should recognize the limited importance of public opinion and the generally disappointing results of public education campaigns. There is in fact ‘no real evidence of a public relations campaign ever having had a significant, sustained effect on mass public opinion on capital punishment’ ( Hammel 2010 : 39). Such campaigns are not useless ( Singer 2016 ), but when they make a difference they usually do so by influencing the views of elites. To put the point a little differently, cultural change can stimulate death penalty reform, but the cultural shifts that matter most are those that operate ‘on and through state actors’ ( Garland 2010 : 143). This is where abolitionists should focus their efforts at persuasion.

Second, legal challenges to capital punishment should continue, for they have been effective in Africa, the former British colonies of the Caribbean, the USA, and many other countries (see the Death Penalty Project, https://www.deathpenaltyproject.org ). Moreover, legal challenges tend to be most effective when they come not from individual attorneys but from teams of attorneys and their non-attorney allies—social workers, scholars, mitigation investigators, and the like ( Garrett 2017 : Chapters 5–6). The basic strategy of successful teams is to ‘Make the law do what it promises. Make it be perfect’ ( Von Drehle 2006 : 196). One result is the growing recognition that state killing is incompatible with legal values. Another is a shift in focus from what the death penalty does for people to what it does to them. The evidence of the death penalty’s decline summarized in the first section of this article suggests that country after country has realized that retaining capital punishment breeds disrespect for law by exposing many of its shortcomings ( Sarat 2001 ). In some contexts, this recognition is best cultivated not by invoking ‘human rights’ as a ‘rhetorical ornament’ for anti-death penalty claims ( Dudai 2017 : 18), but simply by concentrating on what domestic law promises—and what it fails to deliver.

Third, research has contributed to the decline of capital punishment, both by undermining claims about its purported deterrent effects and by documenting flaws in its administration. In these ways, a growing empirical literature highlights ‘the lack of benefits associated with capital punishment and the burgeoning list of problems with its use’ ( Donohue 2016 : 53). Unfortunately, much of the available research concentrates on capital punishment in one country—the USA—which provides ‘a rather distorted and partial view of the death penalty’ worldwide ( Hood and Hoyle 2015 : 3). Going forward, scholars should explore questions about capital punishment in the many under-researched retentionist nations of Asia and the Middle East, and they should focus their dissemination efforts on the legal teams and governmental elites that have the capacity to challenge and change death penalty policy and practice, as described above in the first and second imperatives.

Fourth, abolition alone is not enough, in two senses. For one, it is not acceptable to replace capital punishment with a sentence of life without parole which is itself a cruel punishment that represents ‘life without hope’ and disrespect for human rights and human dignity ( Hood 2001 : 346). Moreover, when life without parole sentences are established, far more offenders tend to receive them than the number of offenders actually condemned to death. Overall, the advent of life without parole sometimes results in small to modest reductions in execution, but its main effect on the criminal process is ‘penal inflation’ ( Zimring and Johnson 2012 ). For most human rights practitioners, this is hardly a desirable set of outcomes. In addition, abolition is a hollow victory when extrajudicial executions continue or increase afterwards, yet this occurs often. The nexus between judicial and extrajudicial executions is poorly understood and much in need of further study, but the available evidence from countries such as Mexico and the Philippines suggests that ending judicial executions may do little to diminish state killing. In the light of this legal realism, a single-issue stress on abolishing capital punishment because it is inconsistent with human rights might well be considered more spectacle than substance ( Nagaraj 2017 : 23).

Finally, while the present moment is in some ways an ‘extraordinarily dangerous time’ for human rights advocates ( Alston 2017 : 14), there is room for optimism that the death penalty may be nearing the ‘end of its rope’ ( Garrett 2017 ). Overall, a factful consideration of contemporary capital punishment suggests that the situation in the world today is both bad and better ( Rothman 2018 ). A factful perspective on capital punishment also makes it reasonable to be a ‘possibilist’ about the future of this form of state killing ( Rosling et al. 2018 : 69). Substantial progress has been made toward worldwide abolition, and there are good reasons to believe that more progress is possible.

Special thanks to Professor Roger Hood for his foundational studies of the death penalty worldwide.

Alston P. 2017 . The Populist Challenge to Human Rights . Journal of Human Rights Practice 9 ( 1 ): 1 – 15 .

Google Scholar

Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en (referenced 15 July 2018).

Baumgartner F. R. , De Boef S. L. , Boydstun A. E. . 2008 . The Decline of the Death Penalty and the Discovery of Innocence . New York : Cambridge University Press .

Google Preview

Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide. Cornell Law School, Ithaca, NY. http://www.deathpenaltyworldwide.org (referenced 28 May 2019).

Death Penalty Information Center. The Death Penalty: An International Perspective. https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/death-penalty-international-perspective (referenced 15 July 2018).

Donohue J. J. 2016 . Empirical Analysis and the Fate of Capital Punishment . Duke Journal of Constitutional Law and Public Policy 11 ( 1&2 ): 51 – 106 .

Dudai R. 2017 . Human Rights in the Populist Era: Mourn then (Re)Organize . Journal of Human Rights Practice 9 ( 1 ): 16 – 21 .

Garland D. 2010 . Peculiar Institution: America’s Death Penalty in an Age of Abolition . Cambridge, MA : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press .

Garrett B. L. 2017 . End of Its Rope: How Killing the Death Penalty Can Revive Criminal Justice . Cambridge, MA : Harvard University Press .

Grant M. 2014 . China Executed 2,400 Prisoners Last Year Says Human Rights Group. Newsweek . 21 October. https://www.newsweek.com/china-executed-2400-prisoners-2013-says-human-rights-group-278733 (referenced 29 May 2019).

Hammel A. 2010 . Ending the Death Penalty: The European Experience in Global Perspective . Palgrave Macmillan .

Hands Off Cain. http://www.handsoffcain.info (referenced 28 May 2019).

He J. 2016 . Back from the Dead: Wrongful Convictions and Criminal Justice in China . University of Hawaii Press .

Hodgkinson P. 2004 . Capital Punishment: Improve It or Remove It? In Hodgkinson P. , A. Schabas W. (eds), Capital Punishment: Strategies for Abolition , pp. 1 – 35 . New York : Cambridge University Press .

Hood R. 2001 . Capital Punishment: A Global Perspective . Punishment & Society 3 ( 3 ): 331 – 54 .

Hood R. , Hoyle C. . 2008 . The Death Penalty: A Worldwide Perspective (4th ed.). New York : Oxford University Press .

Hood R. , Hoyle C. . 2009 . Abolishing the Death Penalty Worldwide: The Impact of a ‘New Dynamic’ . Crime and Justice 38 ( 1 ): 1 – 63 .

Hood R. , Hoyle C. . 2015 . The Death Penalty: A Worldwide Perspective (5th ed.). New York : Oxford University Press .

Johnson D. T. , Fernquest J. . 2018 . Governing through Killing: The War on Drugs in the Philippines . Asian Journal of Law & Society 5 ( 2 ): 359 – 90 .

Johnson D. T. , Zimring F. E. . 2009 . The Next Frontier: National Development, Political Change, and the Death Penalty in Asia . New York : Oxford University Press .

Levitsky S. , Ziblatt D. . 2018 . How Democracies Die . New York : Crown .

Luce E. 2017 . The Retreat of Western Liberalism . New York : Atlantic Monthly Press .

Malkani B. 2013 . The Obligation to Refrain from Assisting the Use of the Death Penalty . International & Comparative Law Quarterly 62 ( 3 ): 523 – 56 .

Moyn S. 2018 . How the Human Rights Movement Failed. New York Times . 23 April.

Muramatsu K. , Johnson D. T. , Yano K. . 2018 . The Death Penalty and Homicide Deterrence in Japan . Punishment & Society 20 ( 4 ): 432 – 57 .

Nagaraj V. K. 2017 . Human Rights and Populism: Some More Questions in Response to Philip Alston . Journal of Human Rights Practice 9 ( 1 ): 22 – 4 .

National Research Council. 2012 . Deterrence and the Death Penalty . Washington, DC : The National Academies Press .

Pinker S. 2011 . The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined . New York : Viking .

Radzinowicz L. 1999 . Adventures in Criminology . Routledge .

Rosling H. , Rosling O. , Rosling Ronnlund A. . 2018 . Factfulness: Ten Reasons We’re Wrong about the World—and Why Things Are Better than You Think . New York : Flatiron Books .

Rothman J. 2018 . The Big Question: Are Things Getting Better or Worse? The New Yorker . 23 July.

Sarat A. 2001 . When the State Kills: Capital Punishment and the American Condition . Princeton University Press .

Singer P. 2016 . Is There Moral Progress? In Ethics in the Real World: 82 Brief Essays on Things that Matter , pp. 9 – 11 . Princeton University Press .

Von Drehle D. 2006 . Among the Lowest of the Dead: The Culture of Capital Punishment . University of Michigan Press .

Zimring F. E. 2003 . The Contradictions of American Capital Punishment . New York : Oxford University Press .

Zimring F. E. , Johnson D. T. . 2012 . The Dark at the Top of the Stairs: Four Destructive Influences of Capital Punishment on American Criminal Justice. In Peterselia J. , R. Reitz K. (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Sentencing and Corrections , pp. 737 – 52 . New York : Oxford University Press .

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1757-9627

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Find Study Materials for

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- English Literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Social Studies

- Browse all subjects

- Read our Magazine

Create Study Materials

Did you know that the last execution in the UK took place in the 1960s? Capital punishment was used in the UK for centuries. The last execution in the UK was on 13 August 1964. Capital punishment for murder was suspended in 1965 and eventually abolished for murder in 1969. Then in 1998, capital punishment for treason and piracy with violence was abolished, making Britain fully abolitionist both in practice and in law.

Explore our app and discover over 50 million learning materials for free.

- Capital Punishment in UK

- Explanations

- StudySmarter AI

- Textbook Solutions

- Birth of the USA

- Crime and Punishment in Britain

- Democracy and Dictatorship in Germany

- Early Modern Spain

- Elizabethan Era

- Emergence of USA as a World Power

- European History

- 1969 Divorce Reform Act

- 1983 General Election

- 1997 General Election

- Abortion Act 1967

- Alec Douglas-Home

- Anthony Eden

- Anti-establishment

- Britain 20th Century

- Britain in the Cold War

- British Youth Culture

- Cambridge Five

- Clement Atlee

- Devaluation of the Pound

- Edward Heath

- End of British Empire

- European Free Trade Association Efta

- Falklands War

- Feminism in Britain

- General Election 1979

- Good Friday Agreement

- Gordon Brown

- Harold Macmillan

- Harold Wilson

- Housing Act 1980

- James Callaghan

- LGBTQ Rights UK

- Miners' Strike

- North-South Divide

- Notting Hill Riots

- Permissive Society

- Post War Consensus

- Profumo Affair

- Referendum 1975

- Scottish Devolution

- Sir John Major

- Social Class in the United Kingdom

- Stop Go Economics

- Suez Canal Crisis

- Test Ban Treaty

- Thatcherism

- The Swinging Sixties

- The Welfare State

- Tory Sleaze And Scandals

- Troubles in Northern Ireland

- UK Economic Growth History

- UK Immigration

- UK Nuclear Deterrent

- UK and NATO

- Winston Churchill

- Modern World History

- Political Stability In Germany

- Protestant Reformation

- Public Health In UK

- Spread of Islam

- The Crusades

- The French Revolution

- The Mughal Empire

- Tsarist and Communist Russia

- Viking History

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Nie wieder prokastinieren mit unseren Lernerinnerungen.

History of capital punishment in the UK

Although the death penalty is mentioned in the fifth century BC in the code of the Babylonian king Hammurabi, it was not applied in Great Britain until the fifth century AD.

Capital punishment , also called the death penalty, is the execution of an offender (criminal) sentenced to death after being convicted of a crime by a court of law.

A brief timeline of the death penalty in Great Britain:

British forms of punishment throughout history

As mentioned above, the main form of punishment was hanging. However, over the centuries, other methods have been used.

Some convicts were somewhat ‘luckier’ and were executed by decapitation. This method was considered the least brutal and was used until the 18th Century. Nobles and kings were often executed by using this method.

If you were in the military, the main form of execution was death by firing squad.

Reform of capital punishment

Death penalty reform began in the 19th Century, but it would take until the end of the 20th Century for capital punishment to be abolished entirely.

19th Century

Sir Samuel Romilly (Figure 1), a British lawyer, politician, and legal reformer, initiated the reform of capital punishment that eventually led to its complete abolition. In 1808, Romilly succeeded in abolishing the death penalty for lesser offences. This began a reform that would continue for the next 50 years. In 1810, Romilly addressed the House of Commons on the death penalty and said:

“[there is] no country on the face of the earth in which there [have] been so many different offences according to law to be punished with death as in England” 1

Several laws were enacted in the 19th century:

While these laws ensured that many crimes were no longer punishable by death, the death penalty remained mandatory for treason and murder unless there was a royal pardon.

20th Century

The 20th Century saw an even greater reform of the death penalty when the following laws were enacted.

There are two other notable wartime events in Britain involving the death penalty:

Ten German agents were executed during World War I under the Defence of the Realm Act of 1914.

Sixteen spies were executed during World War II under the Treachery Act of 1940.

At this point, there was no real support for the complete abolition of the death penalty, but activists were gaining momentum.

Campaigns for the abolition of capital punishment

In the 19th Century, prominent figures in Britain began to speak out against the death penalty, such as Sir Samuel Romilly, Charles Dickens, and William Makepeace Thackeray.

Campaigns against capital punishment usually focused on specific cases that aroused public sympathy. Examples include:

One of the most prominent and well-known campaigners for abolition in the 20th Century was the wealthy businesswoman Violet van der Elst (Figure 2).Although the first full parliamentary debate of the 20th Century on capital punishment took place in 1929, the reports were largely ignored. The issue was considered a low priority on the political agenda.

Reasons for the abolition of capital punishment

Campaigns against capital punishment were based on moral and humanitarian grounds. Many activists believed that the infliction of pain was considered corrupting and uncivilised and that the death penalty did not provide redemption for the criminal.Violet van der Elst argued that capital punishment was uncivilised and harmful to society. She also argued that it is disproportionately applied to poor people.

Capital punishment became an increasingly important political and social issue. In 1948, the Criminal Justice Act was passed. This act abolished penal servitude, prison divisions, and flogging.

Penal servitude was the punishment of being sent to prison and forced to do hard physical labour.

The public increasingly drew their attention to capital punishment in the postwar period. The following three cases were crucial in influencing views on the death penalty:

Abolition of capital punishment

Sydney Silverman was a British Labour politician, elected as a Member of Parliament (MP) in 1933, and for over 20 years, he committed himself to the abolition of capital punishment. In 1965 he introduced the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act . This act suspended the death penalty for 5 years, and it was replaced with a mandatory life sentence.

Abolition is the action of officially ending or stopping something

- On 16 December 1969, the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act was made permanent, and with it, capital punishment for murder was abolished.

It was, however, not until 25 July 1973, with the Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act , that capital punishment was abolished in Northern Ireland.

The last execution in the UK took place on 13 August 1964, with the hanging of Peter Allen and Gwynne Evans. Even though the Homicide Act was already in place, considering they murdered a taxi driver and doing so ‘in the furtherance of theft’, it made it a capital crime.

Final abolition

While the abolition of capital punishment for murder had been in place since 1969, and no capital punishment in any sense had been carried out in the UK, there was no full abolition yet. The following events led to full abolition of capital punishment:

In 1998, with the Human Rights Act and the Crime and Disorder Act, the death penalty was now fully abolished.

End of capital punishment in Europe

Capital punishment has been completely abolished in all European countries, with the exception of Belarus and Russia.

The complete ban on capital punishment is enacted in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (EU) , as well as in the adopted protocols of the European Convention of Human Rights of the Council of Europe .

Some facts about the abolition of capital punishment in Europe:

San Marino, Portugal, and the Netherlands were the first countries to abolish capital punishment.

Belarus, not a party of the European Convention on Human Rights, still practises capital punishment carried out by shooting, with the most recent two executions carried out in 2019

Russia has suspended capital punishment indefinitely since 1996. It is, however, still incorporated in its law

In 2012, Latvia became the last EU member to abolish capital punishment in wartime.

Capital punishment has been constitutionally abolished in Bosnia and Herzegovina since 1995, but it was not until 4 October 2019 that capital punishment was erased entirely from the Constitution of Republika Srpska, 1 entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Capital Punishment in UK - Key takeaways

- Capital punishment in the UK dates back to at least the 5th Century.

- Sir Samuel Romilly started capital punishment reform in the early 19th Century.

- Judgement of Death Act 1823.

- Substitution of Punishment of Death Act 1841.

- Capital Punishment Amendment Act 1868.

- While the three acts ensured many crimes were no longer punishable by death, capital punishment remained mandatory for treason and murder unless there was a royal pardon.

- In 1957, the Homicide Act was established. This act brought in the distinction between capital and non-capital murder . Only the former carried an automatic death sentence.

- In 1998, with the Human Rights Act and the Crime and Disorder Act, the death penalty was fully abolished.

- Inside Time Reports. Death penalty abolished. Insidetime. 27 November 2020

- Infanticide Act 1938. Legislation.gov.uk.

Frequently Asked Questions about Capital Punishment in UK

--> when did capital punishment of children end in the uk.

In 1908 with the Children Act.

--> When was the end of capital punishment?

The complete abolition of capital punishment was in 1998 with the Human Rights Act 1998 and the Crime and Disorder Act 1998.

--> Who abolished the death penalty?

The abolishment of the death penalty began with Sydney Silverman, which started with the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act of 1965.

--> Has capital punishment been abolished in Europe?

Capital punishment has been completely abolished in all European countries, with the exception of Belarus and Russia.

--> Why should capital punishment be abolished?

Campaigns against capital punishment have called it morally wrong and inhumane. It was uncivilised and harmful to society. Violet van der Elst also argued that it was applied disproportionally to poor people.

What is the definition of capital punishment?

Capital punishment, also called the death penalty, is the execution of an offender (criminal) sentenced to death after being convicted of a crime by a court of law.

What was the Bloody Code?

In the 1700s, the number of capital crimes rose to 222. This legal system is called the Bloody Code. It led to reform on capital punishment in 1823–1837 when capital crimes were reduced to 100.

He was a British lawyer, politician and legal reformer. He was also the person who started the reform of capital punishment, eventually ending capital punishment altogether.

It ensured that many crimes were no longer punishable by death. However, capital punishment remained mandatory for treason and murder unless there was a royal pardon.

Which acts and events of the 20th Century saw an even bigger reform of capital punishment?

- Children Act 1908.

- Infanticide Act 1922 and 1937.

- Death sentence for pregnant women was abolished in 1931.

- Children and Young Persons Act 1933.

- Infanticide Act (Northern Ireland) 1939.

Learn with 20 Capital Punishment in UK flashcards in the free StudySmarter app

Already have an account? Log in

of the users don't pass the Capital Punishment in UK quiz! Will you pass the quiz?

How would you like to learn this content?

Free history cheat sheet!

Everything you need to know on . A perfect summary so you can easily remember everything.

Join over 22 million students in learning with our StudySmarter App

The first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

- Flashcards & Quizzes

- AI Study Assistant

- Study Planner

- Smart Note-Taking

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

This is still free to read, it's not a paywall.

You need to register to keep reading, create a free account to save this explanation..

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

By signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Entdecke Lernmaterial in der StudySmarter-App

Privacy Overview

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

The research on capital punishment: Recent scholarship and unresolved questions

2014 review of research on capital punishment, including studies that attempt to quantify rates of innocence and the potential deterrence effect on crime.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Alexandra Raphel and John Wihbey, The Journalist's Resource January 5, 2015

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/criminal-justice/research-capital-punishment-key-recent-studies/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

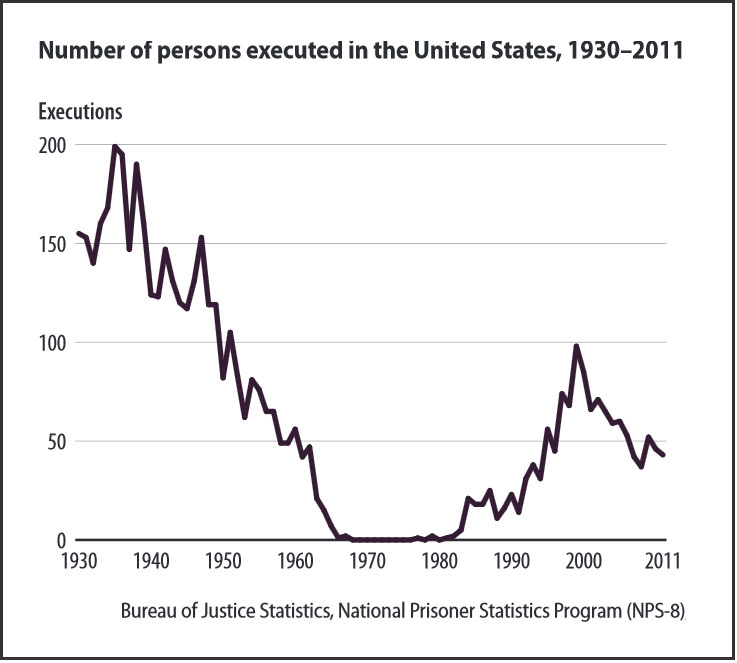

Over the past year the death penalty has again come into focus as a major public policy and political issue, catalyzed by several high-profile events.

The botched execution of convicted murderer and rapist Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma in 2014 was seen as a potential turning point in the debate, bringing increased attention to the mechanisms by which persons are executed. That was followed by a number of other closely scrutinized cases, and the year ended with few executions relative to years past. On December 31, 2014, Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley commuted the sentences of the remaining four prisoners on death row in that state. In 2013, Maryland became the 18th state to abolish the death penalty after Connecticut in 2012 and New Mexico in 2009.

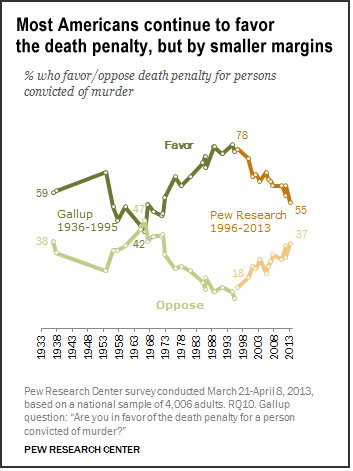

Meanwhile, polling data suggests some softening of public attitudes, though the majority Americans continue to support capital punishment. Gallop noted in October 2014 that the level of public support (60%) is at its lowest in 40 years. A Washington Post -ABC News poll in mid-2014 found that more Americans support life sentences, rather than the death penalty, for convicted murderers. Further, recent polls from the Pew Research Center indicate that only a bare majority of Americans now support capital punishment, 55%, down from 78% in 1996.

Scholarly research sheds light on a number of important aspects of this issue:

False convictions

One key reason for the contentious debate is the concern that states are executing innocent people. How many people are unjustly facing the death penalty? By definition, it is difficult to obtain a reliable answer to this question. Presumably if judges, juries, and law enforcement were always able to conclusively determine who was innocent, those defendants would simply not be convicted in the first place. When capital punishment is the sentence, however, this issue takes on new importance.

Some believe that when it comes to death-penalty cases, this is not a huge cause for concern. In his concurrent opinion in the 2006 Supreme Court case Kansas v. Marsh , Justice Antonin Scalia suggested that the execution error rate was minimal, around 0.027%. However, a 2014 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that the figure could be higher. Authors Samuel Gross (University of Michigan Law School), Barbara O’Brien (Michigan State University College of Law), Chen Hu (American College of Radiology) and Edward H. Kennedy (University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine) examine data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics and the Department of Justice relating to exonerations from 1973 to 2004 in an attempt to estimate the rate of false convictions among death row defendants. (Determining innocence with full certainty is an obvious challenge, so as a proxy they use exoneration — “an official determination that a convicted defendant is no longer legally culpable for the crime.”) In short, the researchers ask: If all death row prisoners were to remain under this sentence indefinitely, how many of them would have eventually been found innocent (exonerated)?

Interestingly, the authors also note that advances in DNA identification technology are unlikely to have a large impact on false conviction rates because DNA evidence is most often used in cases of rape rather than homicide. To date, only about 13% of death row exonerations were the result of DNA testing. The Innocence Project , a litigation and public policy organization founded in 1992, has been deeply involved in many such cases.

Death penalty deterrence effects: What do we know?

A chief way proponents of capital punishment defend the practice is the idea that the death penalty deters other people from committing future crimes. For example, research conducted by John J. Donohue III (Yale Law School) and Justin Wolfers (University of Pennsylvania) applies economic theory to the issue: If people act as rational maximizers of their profits or well-being, perhaps there is reason to believe that the most severe of punishments would serve as a deterrent. (The findings of their 2009 study on this issue, “Estimating the Impact of the Death Penalty on Murder,” are inconclusive.) In contrast, one could also imagine a scenario in which capital punishment leads to an increased homicide rate because of a broader perception that the state devalues human life. It could also be possible that the death penalty has no effect at all because information about executions is not diffused in a way that influences future behavior.

In 1978 — two years after the Supreme Court issued its decision reversing a previous ban on the death penalty ( Gregg v. Georgia ) — the National Research Council (NRC) published a comprehensive review of the current research on capital punishment to determine whether one of these hypotheses was more empirically supported than the others. The NRC concluded that “available studies provide no useful evidence on the deterrent effect of capital punishment.”

Researchers have subsequently used a number of methods in an effort to get closer to an accurate estimate of the deterrence effect of the death penalty. Many of the studies have reached conflicting conclusions, however. To conduct an updated review, the NRC formed the Committee on Deterrence and the Death Penalty, comprised of academics from economics departments and public policy schools from institutions around the country, including the Carnegie Mellon University, University of Chicago and Duke University.

In 2012, the Committee published an updated report that concluded that not much had changed in recent decades: “Research conducted in the 30 years since the earlier NRC report has not sufficiently advanced knowledge to allow a conclusion, however qualified, about the effect of the death penalty on homicide rates.” The report goes on to recommend that none of the reviewed reports be used to influence public policy decisions on the death penalty.

Why has the research not been able to provide any definitive answers about the impact of the death penalty? One general challenge is that when it comes to capital punishment, a counter-factual policy is simply not observable. You cannot simultaneously execute and not execute defendants, making it difficult to isolate the impact of the death penalty. The Committee also highlights a number of key flaws in the research designs:

- There are both capital and non-capital punishment options for people charged with serious crimes. So, the relevant question on the deterrent effect of capital punishment specifically “is the differential deterrent effect of execution in comparison with the deterrent effect of other available or commonly used penalties.” None of the studies reviewed by the Committee took into account these severe, but noncapital punishments, which could also have an effect on future behaviors and could confound the estimated deterrence effect of capital punishment.

- “They use incomplete or implausible models of potential murderers’ perceptions of and response to the capital punishment component of a sanction regime”

- “The existing studies use strong and unverifiable assumptions to identify the effects of capital punishment on homicides.”

In a 2012 study, “Deterrence and the Dealth Penalty: Partial Identificaiton Analysis Using Repeated Cross Sections,” authors Charles F. Manski (Northwestern University) and John V. Pepper (University of Virginia) focus on the third challenge. They note: “Data alone cannot reveal what the homicide rate in a state without (with) a death penalty would have been had the state (not) adopted a death penalty statute. Here, as always when analyzing treatment response, data must be combined with assumptions to enable inference on counterfactual outcomes.”

However, even though the authors do not arrive at a definitive conclusion, the National Research Council Committee notes that this type of research holds some value: “Rather than imposing the strong but unsupported assumptions required to identify the effect of capital punishment on homicides in a single model or an ad hoc set of similar models, approaches that explicitly account for model uncertainty may provide a constructive way for research to provide credible albeit incomplete answers.”

Another strategy researchers have taken is to limit the focus of studies on potential short-term effects of the death penalty. In a 2009 paper, “The Short-Term Effects of Executions on Homicides: Deterrence, Displacement, or Both?” authors Kenneth C. Land and Hui Zheng of Duke University, along with Raymond Teske Jr. of Sam Houston State University, examine monthly execution data (1980-2005) from Texas, “a state that has used the death penalty with sufficient frequency to make possible relatively stable estimates of the homicide response to executions.” They conclude that “evidence exists of modest, short-term reductions in the numbers of homicides in Texas in the months of or after executions.” Depending on which model they use, these deterrent effects range from 1.6 to 2.5 homicides.

The NRC’s Committee on Deterrence and the Death Penalty commented on the findings, explaining: “Land, Teske and Zheng (2009) should be commended for distinguishing between periods in Texas when the use of capital punishment appears to have been erratic and when it appears to have been systematic. But they fail to integrate this distinction into a coherently delineated behavioral model that incorporates sanctions regimes, salience, and deterrence. And, as explained above, their claims of evidence of deterrence in the systematic regime are flawed.”

A more recent paper (2012) from the three authors, “The Differential Short-Term Impacts of Executions on Felony and Non-Felony Homicides,” addresses some of these concerns. Published in Criminology and Public Policy , the paper reviews and updates some of their earlier findings by exploring “what information can be gained by disaggregating the homicide data into those homicides committed in the course of another felony crime, which are subject to capital punishment, and those committed otherwise.” The results produce a number of different findings and models, including that “the short-lived deterrence effect of executions is concentrated among non-felony-type homicides.”

Other factors to consider

The question of what kinds of “mitigating” factors should prevent the criminal justice system from moving forward with an execution remains hotly disputed. A 2014 paper published in the Hastings Law Journal , “The Failure of Mitigation?” by scholars at the University of North Carolina and DePaul University, investigates recent executions of persons with possible mental or intellectual disabilities. The authors reviewed 100 cases and conclude that the “overwhelming majority of executed offenders suffered from intellectual impairments, were barely into adulthood, wrestled with severe mental illness, or endured profound childhood trauma.”

Two significant recommendations for reforming the existing process also are supported by some academic research. A 2010 study by Pepperdine University School of Law published in Temple Law Review , “Unpredictable Doom and Lethal Injustice: An Argument for Greater Transparency in Death Penalty Decisions,” surveyed the decision-making process among various state prosecutors. At the request of a state commission, the authors first surveyed California district attorneys; they also examined data from the other 36 states that have the death penalty. The authors found that prosecutors’ capital punishment filing decisions remain marked by local “idiosyncrasies,” meaning that “the very types of unfairness that the Supreme Court sought to eliminate” beginning in 1972 may still “infect capital cases.” They encourage “requiring prosecutors to adhere to an established set of guidelines.” Finally, there has been growing support for taping interrogations of suspects in capital cases, so as to guard against the phenomenon of false confessions .

Related reading: For an international perspective on capital punishment, see Amnesty International’s 2013 report ; for more information on the evolution of U.S. public opinion on the death penalty, see historical trends from Gallup .

Keywords: crime, prisons, death penalty, capital punishment

About the Authors

Alexandra Raphel

John Wihbey

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

student opinion

Should the Death Penalty Be Abolished?

In its last six months, the United States government has put 13 prisoners to death. Do you think capital punishment should end?

By Nicole Daniels

Students in U.S. high schools can get free digital access to The New York Times until Sept. 1, 2021.

In July, the United States carried out its first federal execution in 17 years. Since then, the Trump administration has executed 13 inmates, more than three times as many as the federal government had in the previous six decades.

The death penalty has been abolished in 22 states and 106 countries, yet it is still legal at the federal level in the United States. Does your state or country allow the death penalty?

Do you believe governments should be allowed to execute people who have been convicted of crimes? Is it ever justified, such as for the most heinous crimes? Or are you universally opposed to capital punishment?

In “ ‘Expedited Spree of Executions’ Faced Little Supreme Court Scrutiny ,” Adam Liptak writes about the recent federal executions:

In 2015, a few months before he died, Justice Antonin Scalia said he w o uld not be surprised if the Supreme Court did away with the death penalty. These days, after President Trump’s appointment of three justices, liberal members of the court have lost all hope of abolishing capital punishment. In the face of an extraordinary run of federal executions over the past six months, they have been left to wonder whether the court is prepared to play any role in capital cases beyond hastening executions. Until July, there had been no federal executions in 17 years . Since then, the Trump administration has executed 13 inmates, more than three times as many as the federal government had put to death in the previous six decades.

The article goes on to explain that Justice Stephen G. Breyer issued a dissent on Friday as the Supreme Court cleared the way for the last execution of the Trump era, complaining that it had not sufficiently resolved legal questions that inmates had asked. The article continues:

If Justice Breyer sounded rueful, it was because he had just a few years ago held out hope that the court would reconsider the constitutionality of capital punishment. He had set out his arguments in a major dissent in 2015 , one that must have been on Justice Scalia’s mind when he made his comments a few months later. Justice Breyer wrote in that 46-page dissent that he considered it “highly likely that the death penalty violates the Eighth Amendment,” which bars cruel and unusual punishments. He said that death row exonerations were frequent, that death sentences were imposed arbitrarily and that the capital justice system was marred by racial discrimination. Justice Breyer added that there was little reason to think that the death penalty deterred crime and that long delays between sentences and executions might themselves violate the Eighth Amendment. Most of the country did not use the death penalty, he said, and the United States was an international outlier in embracing it. Justice Ginsburg, who died in September, had joined the dissent. The two other liberals — Justices Sotomayor and Elena Kagan — were undoubtedly sympathetic. And Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, who held the decisive vote in many closely divided cases until his retirement in 2018, had written the majority opinions in several 5-to-4 decisions that imposed limits on the death penalty, including ones barring the execution of juvenile offenders and people convicted of crimes other than murder .