- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

Case Study: Cystic Fibrosis - CER

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 26446

This page is a draft and is under active development.

Part I: A Case of Cystic Fibrosis

Dr. Weyland examined a six month old infant that had been admitted to University Hospital earlier in the day. The baby's parents had brought young Zoey to the emergency room because she had been suffering from a chronic cough. In addition, they said that Zoey sometimes would "wheeze" a lot more than they thought was normal for a child with a cold. Upon arriving at the emergency room, the attending pediatrician noted that salt crystals were present on Zoey's skin and called Dr. Weyland, a pediatric pulmonologist. Dr. Weyland suspects that baby Zoey may be suffering from cystic fibrosis.

CF affects more than 30,000 kids and young adults in the United States. It disrupts the normal function of epithelial cells — cells that make up the sweat glands in the skin and that also line passageways inside the lungs, pancreas, and digestive and reproductive systems.

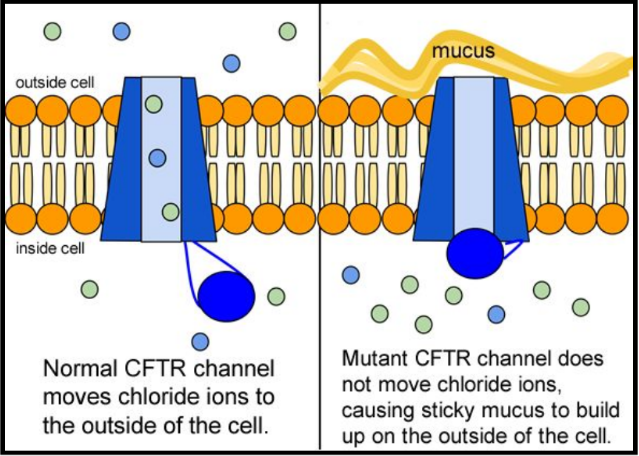

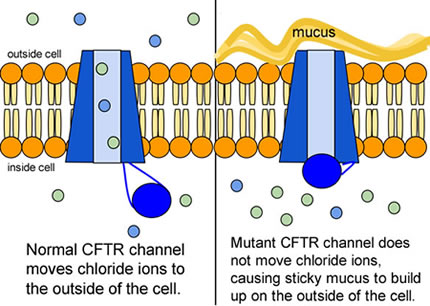

The inherited CF gene directs the body's epithelial cells to produce a defective form of a protein called CFTR (or cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator) found in cells that line the lungs, digestive tract, sweat glands, and genitourinary system.

When the CFTR protein is defective, epithelial cells can't regulate the way that chloride ions pass across cell membranes. This disrupts the balance of salt and water needed to maintain a normal thin coating of mucus inside the lungs and other passageways. The mucus becomes thick, sticky, and hard to move, and can result in infections from bacterial colonization.

- "Woe to that child which when kissed on the forehead tastes salty. He is bewitched and soon will die" This is an old saying from the eighteenth century and describes one of the symptoms of CF (salty skin). Why do you think babies in the modern age have a better chance of survival than babies in the 18th century?

- What symptoms lead Dr. Weyland to his initial diagnosis?

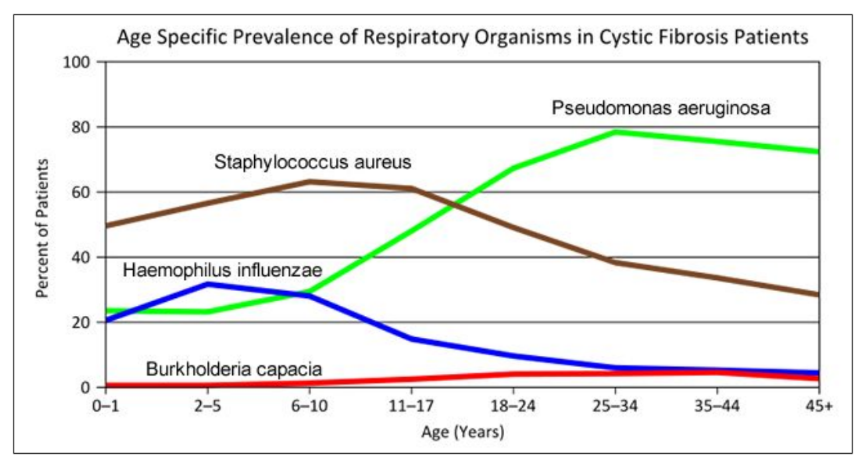

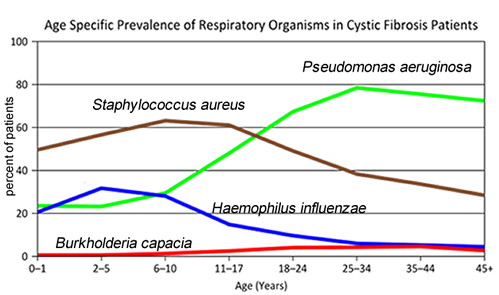

- Consider the graph of infections, which organism stays relatively constant in numbers over a lifetime. What organism is most likely affecting baby Zoey?

- What do you think is the most dangerous time period for a patient with CF? Justify your answer.

Part II: CF is a disorder of the cell membrane.

Imagine a door with key and combination locks on both sides, back and front. Now imagine trying to unlock that door blind-folded. This is the challenge faced by David Gadsby, Ph.D., who for years struggled to understand the highly intricate and unusual cystic fibrosis chloride channel – a cellular doorway for salt ions that is defective in people with cystic fibrosis.

His findings, reported in a series of three recent papers in the Journal of General Physiology, detail the type and order of molecular events required to open and close the gates of the cystic fibrosis chloride channel, or as scientists call it, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR).

Ultimately, the research may have medical applications, though ironically not likely for most cystic fibrosis patients. Because two-thirds of cystic fibrosis patients fail to produce the cystic fibrosis channel altogether, a cure for most is expected to result from research focused on replacing the lost channel.

5. Suggest a molecular fix for a mutated CFTR channel. How would you correct it if you had the ability to tinker with it on a molecular level?

6. Why would treatment that targets the CFTR channel not be effective for 2⁄3 of those with cystic fibrosis?

7. Sweat glands cool the body by releasing perspiration (sweat) from the lower layers of the skin onto the surface. Sodium and chloride (salt) help carry water to the skin's surface and are then reabsorbed into the body. Why does a person with cystic fibrosis have salty tasting skin?

Part III: No cell is an island

Like people, cells need to communicate and interact with their environment to survive. One way they go about this is through pores in their outer membranes, called ion channels, which provide charged ions, such as chloride or potassium, with their own personalized cellular doorways. But, ion channels are not like open doors; instead, they are more like gateways with high-security locks that are opened and closed to carefully control the passage of their respective ions.

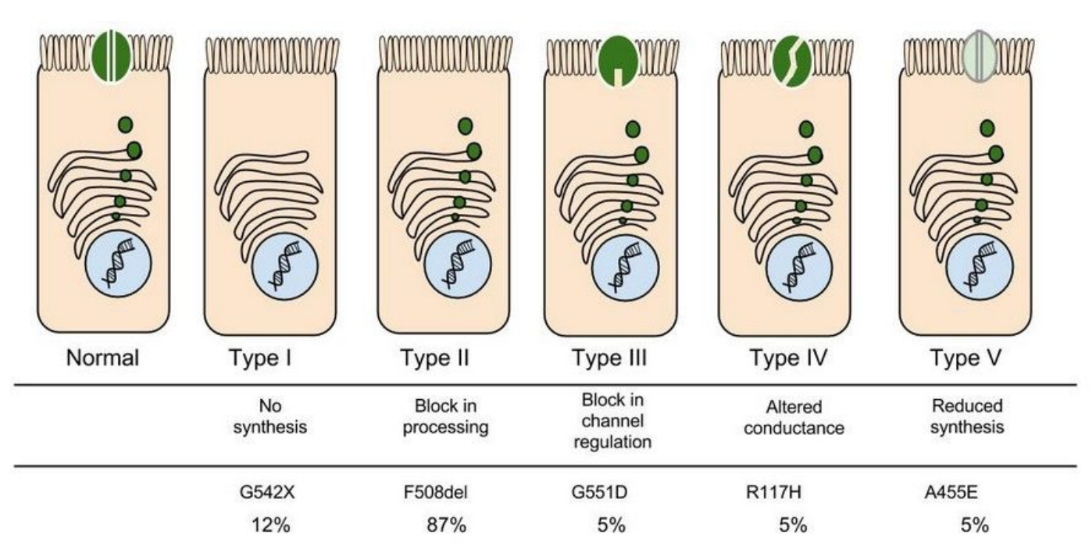

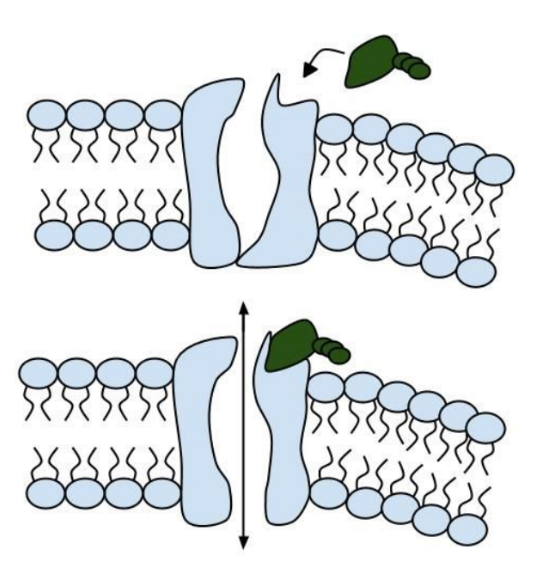

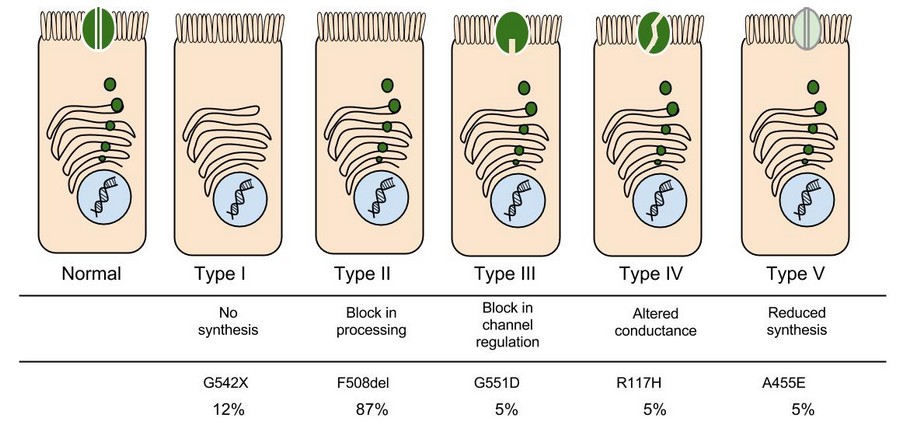

In the case of CFTR, chloride ions travel in and out of the cell through the channel’s guarded pore as a means to control the flow of water in and out of cells. In cystic fibrosis patients, this delicate salt/water balance is disturbed, most prominently in the lungs, resulting in thick coats of mucus that eventually spur life-threatening infections. Shown below are several mutations linked to CFTR:

8. Which mutation do you think would be easiest to correct. Justify your answer. 9. Consider what you know about proteins, why does the “folding” of the protein matter?

Part IV: Open sesame

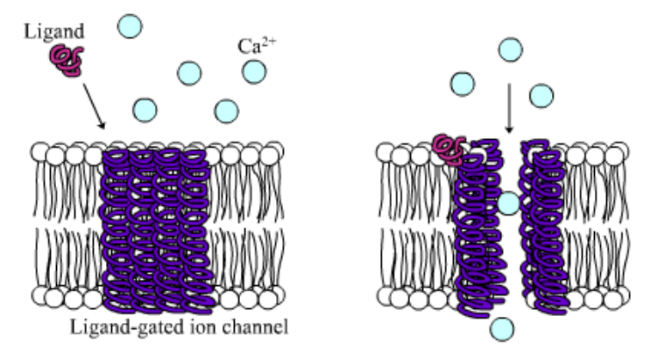

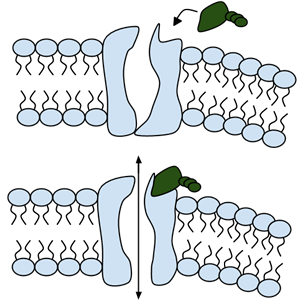

Among the numerous ion channels in cell membranes, there are two principal types: voltage-gated and ligand-gated. Voltage-gated channels are triggered to open and shut their doors by changes in the electric potential difference across the membrane. Ligand-gated channels, in contrast, require a special “key” to unlock their doors, which usually comes in the form of a small molecule.

CFTR is a ligand-gated channel, but it’s an unusual one. Its “key” is ATP, a small molecule that plays a critical role in the storage and release of energy within cells in the body. In addition to binding the ATP, the CFTR channel must snip a phosphate group – one of three “P’s” – off the ATP molecule to function. But when, where and how often this crucial event takes place has remains obscure.

10. Compare the action of the ligand-gated channel to how an enzyme works.

11. Consider the model of the membrane channel, What could go wrong to prevent the channel from opening?

12. Where is ATP generated in the cell? How might ATP production affect the symptoms of cystic fibrosis?

13. Label the image below to show how the ligand-gated channel for CFTR works. Include a summary.

Part V: Can a Drug Treat Zoey’s Condition?

Dr. Weyland confirmed that Zoey does have cystic fibrosis and called the parents in to talk about potential treatments. “Good news, there are two experimental drugs that have shown promise in CF patients. These drugs can help Zoey clear the mucus from his lungs. Unfortunately, the drugs do not work in all cases.” The doctor gave the parents literature about the drugs and asked them to consider signing Zoey up for trials.

The Experimental Drugs

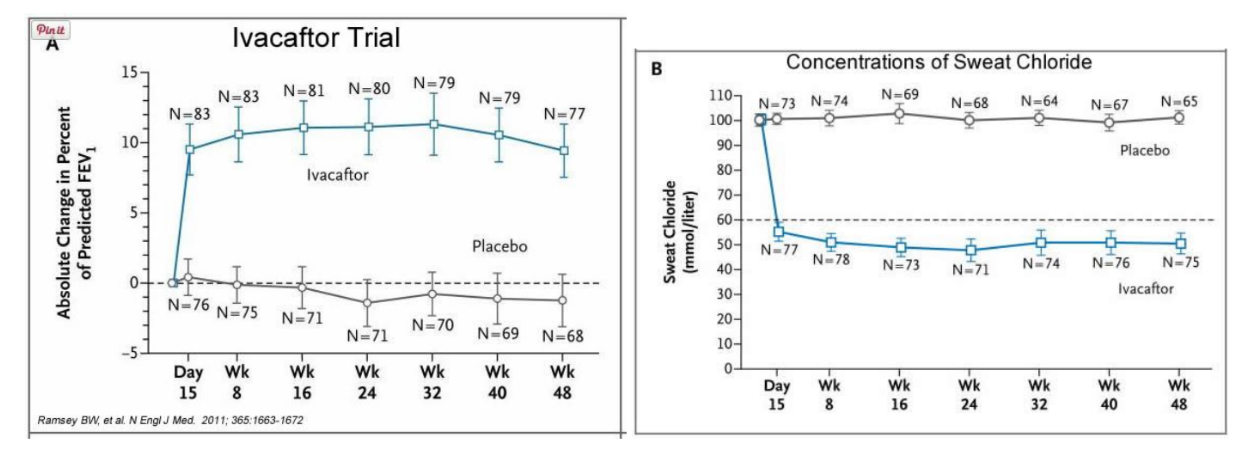

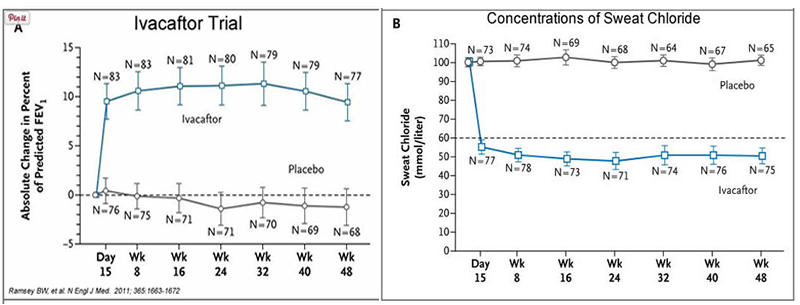

Ivacaftor TM is a potentiator that increases CFTR channel opening time. We know from the cell culture studies that this increases chloride transport by as much as 50% from baseline and restores it closer to what we would expect to observe in wild type CFTR. Basically, the drug increases CFTR activity by unlocking the gate that allows for the normal flow of salt and fluids.

In early trials, 144 patients all of whom were age over the age of 12 were treated with 150 mg of Ivacaftor twice daily. The total length of treatment was 48 weeks. Graph A shows changes in FEV (forced expiratory volume) with individuals using the drug versus a placebo. Graph B shows concentrations of chloride in patient’s sweat.

14. What is FEV? Describe a way that a doctor could take a measurement of FEV.

15. Why do you think it was important to have placebos in both of these studies?

16. Which graph do you think provides the most compelling evidence for the effectiveness of Ivacafor? Defend your choice.

17. Take a look at the mutations that can occur in the cell membrane proteins from Part III. For which mutation do you think Ivacaftor will be most effective? Justify your answer.

18. Would you sign Zoey up for clinical trials based on the evidence? What concerns would a parent have before considering an experimental drug?

Part VI: Zoey’s Mutation

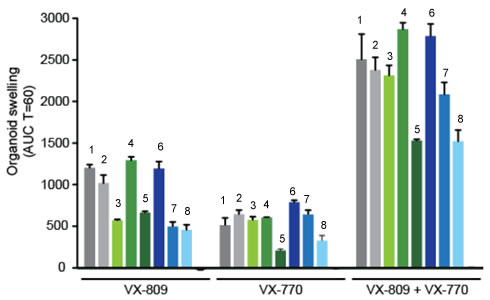

Dr. Weyland calls a week later to inform the parents that genetic tests show that Zoey chromosomes show that she has two copies of the F508del mutation. This mutation, while the most common type of CF mutation, is also one that is difficult to treat with just Ivacaftor. There are still some options for treatment.

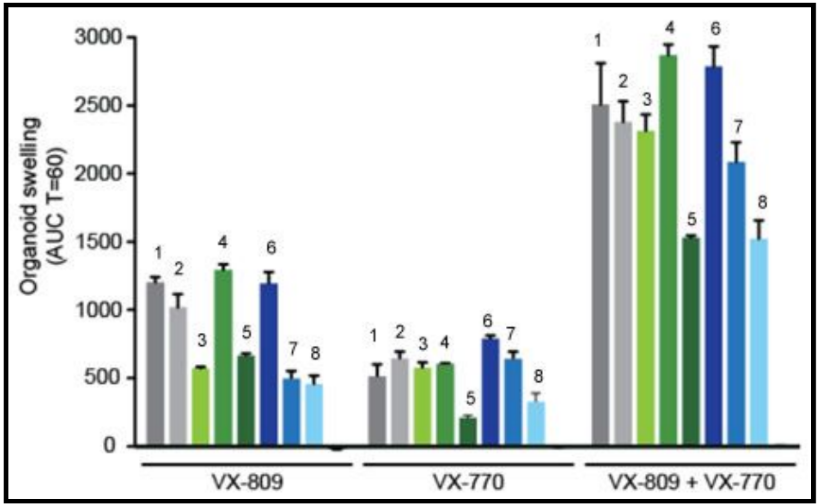

In people with the most common CF mutation, F508del, a series of problems prevents the CFTR protein from taking its correct shape and reaching its proper place on the cell surface. The cell recognizes the protein as not normal and targets it for degradation before it makes it to the cell surface. In order to treat this problem, we need to do two things: first, an agent to get the protein to the surface, and then ivacaftor (VX-770) to open up the channel and increase chloride transport. VX-809 has been identified as a way to help with the trafficking of the protein to the cell surface. When added VX-809 is added to ivacaftor (now called Lumacaftor,) the protein gets to the surface and also increases in chloride transport by increasing channel opening time.

In early trials, experiments were done in-vitro, where studies were done on cell cultures to see if the drugs would affect the proteins made by the cell. General observations can be made from the cells, but drugs may not work on an individual’s phenotype. A new type of research uses ex-vivo experiments, where rectal organoids (mini-guts) were grown from rectal biopsies of the patient that would be treated with the drug. Ex-vivo experiments are personalized medicine, each person may have different correctors and potentiators evaluated using their own rectal organoids. The graph below shows how each drug works for 8 different patients (#1-#8)

19. Compare ex-vivo trials to in-vitro trials.

20. One the graph, label the group that represents Ivacaftor and Lumacaftor. What is the difference between these two drugs?

21. Complete a CER Chart. If the profile labeled #7 is Zoey, rank the possible drug treatments in order of their effectiveness for her mutation. This is your CLAIM. Provide EVIDENCE to support your claim. Provide REASONING that explains why this treatment would be more effective than other treatments and why what works for Zoey may not work for other patients. This is where you tie the graph above to everything you have learned in this case. Attach a page.

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 19 January 2022

Malignancies in patients with cystic fibrosis: a case series

- Dorothea Appelt 1 ,

- Teresa Fuchs 1 ,

- Gratiana Steinkamp 1 , 2 &

- Helmut Ellemunter 1

Journal of Medical Case Reports volume 16 , Article number: 27 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

3413 Accesses

11 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Previous reports have shown an increased number of colorectal cancers in patients with cystic fibrosis. We assessed the database of our cystic fibrosis center to identify patients with all kinds of cancer retrospectively. All patients visiting the Cystic Fibrosis Centre Innsbruck between 1995 and 2019 were included.

Case presentation

Among 229 patients with cystic fibrosis treated at the Cystic Fibrosis Centre in Innsbruck between 1995 and 2019, 11 subjects were diagnosed with a malignant disease. The median age at diagnosis was 25.2 years (mean 24.3 years). There were four gynecological malignancies (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer), two hematological malignancies (acute lymphocytic leukemia), one gastrointestinal malignancy (peritoneal mesothelioma), and four malignancies from other origins (malignant melanoma, neuroblastoma, adrenocortical carcinoma, and thyroid cancer). One malignancy occurred after lung transplantation. There was a strong preponderance of females, with 10 of the 11 cases occurring in women. Six deaths were attributed to cancer.

Conclusions

Most diagnoses were made below 30 years of age, and half of the subjects died from the malignant disease. Awareness of a possible malignancy is needed in patients with atypical symptoms. Regular screenings for cancer should also be considered, not only for gastrointestinal tumors.

Peer Review reports

Improvements in the management of cystic fibrosis (CF) have resulted in better survival of patients, with increasing numbers of patients reaching adulthood. It also seems to be more common that patients with CF suffer from cancer [ 1 , 2 ]. An increased risk of gastrointestinal cancers among CF patients is known [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ], whereas other types of cancer have rarely been reported. A few studies showed differing results with similar [ 7 , 8 ] or higher risk of cancer [ 3 , 9 ] compared with non-CF cohorts. To assess the prevalence of malignant disease in our patients, we collected data from the patient database at the CF Centre Innsbruck from 1995 to 2019, including diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of the malignant condition. Among 229 patients with CF, we observed 11 cases with cancer over a period of 24 years.

A 9-month-old Caucasion girl, who had been diagnosed with CF at the age of 1 month with an abnormal newborn screening, had a routine abdominal ultrasound, where a neuroblastoma stage 4s was diagnosed. At the time of diagnosis, no symptoms were present. The entire tumor was surgically removed, and she received chemotherapy according to the European HR-NBL-1/ESIOP protocol followed by an autologous bone-marrow stem-cell transplantation. At 6 years, the patient presented with pain in the left proximal tibia. Osteomyelitis was suspected, but antibiotic treatment showed no improvement in symptoms. The suspicion of a systemic relapse of the neuroblastoma was confirmed histologically. Chemotherapy according to protocol ESIOP TVD was started. After the fourth cycle, the tumor cells showed resistance to treatment and the disease progressed with changes in the bone marrow. Therapy was intensified with chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Under this therapy, the patient was clinically stable with recurring aplasia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia. Just after her ninth birthday, she presented with a pulmonary exacerbation, which improved only after discontinuation of immunosuppression. The patient and her parents decided to continue with palliative therapy with fractionated low-dose 131I-metaiodobenzylguanidine. Three years after stem cell transplantation, the patient died at home surrounded by family.

A 14-year-old Caucasion girl with CF presented with fever, urticaria, joint pain, fatigue, and reduced general condition. She was diagnosed with c-ALL B-II and admitted for treatment. Chemotherapy was started under protocol AIEOP-BFM ALL 2000. Three weeks after diagnosis, she was discharged. Two days later, she presented with symptoms of a distal intestinal obstruction syndrome (DIOS) with constipation, weakness, hypoglycemia, and hypotonic dehydration. Her condition improved slightly after enema and antibiotic treatment, but she soon developed fever. Chest x-ray showed several peripheral infiltrates in the lungs, so antifungal therapy with amphotericin B was started according to local standard procedures. Despite decreasing inflammatory parameters, her general condition worsened with dyspnea, vertigo, and scintillating scotoma. A head CT scan showed seven brain abscesses. The girl died 1 month and 4 days after diagnosis of c-ALL. The autopsy showed endocarditis with septic abscesses in the brain, lungs, liver, kidney, and spleen. Microbiological examination of blood detected Saccharomyces cerevisiae , sensitive to itraconazole and resistant to amphotericin B.

A 17-year-old Caucasion girl with CF was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) with strong suspicion of leukemia. She was diagnosed with acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) B-II without central nervous system (CNS) involvement. She received chemotherapy under protocol AIEOP-BFM 2009. The ALL was classified as “intermediate risk.” For aplasia, the patient received antibiotic and antifungal prophylaxis and erythrocyte and platelet concentrates. She developed abdominal pain due to Clostridium difficile -associated colitis and considerable accumulation of ascites. With abdominal paracentesis, 6 L of ascites was removed. Then she developed constipation that did not improve with Macrogol therapy. Endoscopic stool removal was performed. Two months after beginning treatment, the patient had peritonitis with Staphylococcus hominis . Antibiotic treatment was started. Chemotherapy was discontinued due to the high risk of infection. She then developed hepatorenal syndrome with a known liver fibrosis and decreasing urine output. Intermittent hemodiafiltration and hemodialysis were necessary. In addition, the patient had deteriorating liver function values. A bone marrow biopsy showed no progression of the leukemia. Infection parameters increased nonetheless. There were multiple possible foci such as colitis with Clostridium difficile , peritonitis with Staphylococcus hominis , detection of atypical nontuberculosis mycobacteria in sputum, and a local infection of the central venous catheter. Two months and 9 days after diagnosis of ALL, the patient developed multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and died.

A 21-year-old Caucasion woman had an excision of a malign melanoma on her back. Histology showed a Breslow thickness of 1.9 mm and Clark level IV. A re-excision with 1 cm safety margin and a biopsy of sentinel lymph nodes were performed, showing no sign of metastases. Seven years after diagnosis of the melanoma, the patient remains tumor free.

A 22-year-old Caucasion woman presented with Cushing’s syndrome. Further investigations showed an adrenal carcinoma. The patient underwent surgery where the entire tumor was removed. The staging showed no metastases, so chemotherapy was not added to the treatment. Ten months after the first symptoms, the woman had a local tumor relapse with metastases in the lung, femur, and tibia. The tumor was unresectable, and the patient refused further chemotherapy. She started palliative therapy with radiation of the painful metastases in the femur and tibia. The disease progressed, and the patient showed psychological alterations. Airway clearance therapy became more difficult and less effective, and the respiratory status of the patient worsened. Fifteen months after diagnosis, the patient died due to respiratory insufficiency.

A 25-year-old Caucasion woman had an abnormal Pap smear (PAP IV) followed by a cervical conization and fractional abrasion. Histology showed a cervical glandular intraepithelial neoplasia (CGIN II) with a positive resection margin. The patient refused a hysterectomy at that time. The gynecological follow-ups with Pap smear and abrasion showed no residuum. Over the years, the pulmonary condition of the woman constantly declined with severe pulmonary hemorrhage at age 29. An angiographic coiling was performed that stabilized the condition for some time. She had to be ventilated and received extracorporeal membrane oxygenation but, despite an emergency lung transplantation, died due to organ failure.

A 28-year-old Caucasion woman with CF liver disease had a decompensation with increasing amounts of ascites. Diuretic therapy was unsatisfactory, so an ascites puncture was done. Laboratory investigation of the ascites showed a high cell count and high protein concentrations suggestive of an inflammatory cause with no sign of malignancy. In addition, the bacteriological cultures of ascites, blood, and urine were sterile. Only the sputum showed a known infection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa . An intravenous suppressive antibiotic treatment was started. A positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) scan showed changes in the lungs consistent with CF and liver cirrhosis with portal hypertension and severe peritonitis with mesentery thickening.

The patient developed severe hypoglycemia and increasing anemia. Gastroscopy showed small esophageal varices without any sign of bleeding. She received intravenous glucose and erythrocyte concentrates. An X-ray of the lung showed growing consolidations in the inferior lobes of the lung. She was transferred to the intensive care unit. Hemofiltration was started because of increasing metabolic acidosis and anuria. The antibiotic treatment was adapted several times, but inflammatory parameters did not improve. No other focus except for the known pulmonary infection could be found. About 1 month after admission to hospital, the patient had more abdominal pain despite permanent analgesic therapy. A CT scan of the abdomen showed a toxic mega colon and a massive growth of the mesentery bulk. A fine-needle biopsy showed a malignant deciduoid mesothelioma. Based on the diagnosis, a multidisciplinary team suggested palliative care, to which the patient and her family agreed. Six weeks after admission to the hospital, the patient died.

On a screening examination in the 15th week of pregnancy, a 28-year-old Caucasion woman had an abnormal Pap smear (PAP IV). Cervical conization showed an adenocarcinoma that had a positive resection margin histologically. The patient had two more conizations, which had a positive resection margin again in histology, and a Shirodkar cerclage was placed. At 32 weeks of pregnancy, fetal lung maturity was induced and a healthy child was born via cesarean section. In the same operation, a radical Wertheim hysterectomy was performed. Histology showed an adenocarcinoma grade 2 with negative resection margins and micrometastases in one of 22 examined lymph nodes. Combined treatment with chemotherapy (cisplatin) and radiation was performed. Six years after diagnosis, the patient is still in remission.

Due to an abnormal Pap smear (PAP IV), a 31-year-old Caucasion woman had a cervical conization and fractional abrasion with CGIN grade II. All resection margins were negative. The patient then developed menometrorrhagia and dyspareunia. A hysterectomy was performed 4 years after diagnosis because of discomfort. The patient is still in remission 15 years after diagnosis.

A 36-year-old Caucasion woman presented with recurring vaginal bleeding. Further gynecological examination with a biopsy showed a cervix carcinoma grade II b. The histology after laparoscopic lymphadenectomy was tumor free. Two weeks after diagnosis, radiochemotherapy was initiated. Five months after diagnosis, a biopsy of the cervix showed mostly necrotic tumor tissue with 10% vital tissue. The woman had surgery with hysterectomy, salpingectomy, and iliac lymphadenectomy. Histology showed an invasive, low-differentiated, nonkeratinized squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix and three of five lymph nodes with metastases. After surgery, a PET-CT scan showed complete remission. Seven months after diagnosis, the woman presented with fever and pain in the groin. A CT scan showed a lymphocele that was punctured, streptococcus was detected, and treatment with antibiotics was started. The check-up examination 12 months after diagnosis with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and PET-CT scans showed an extensive vaginal stump relapse. Chemotherapy was started, but the disease progressed despite therapy. A multidisciplinary team suggested to continue with palliative care, to which the patient and her family agreed. Seventeen months after diagnosis, the patient died.

A 40-year-old Caucasion man with CF who had a lung transplant at 23, was admitted with a multinodular goiter for an operation. During the operation, an immediately frozen section showed bilateral papillary thyroid cancer (right 0.9 cm, left 1 cm). A total thyroidectomy with excision of local lymph nodes was performed. After the operation, a PET-CT-scan showed multiple glucose-metabolizing lesions in lymph nodes from neck to mediastinum. A neck dissection was performed. Histology showed multiple metastases in the lymph nodes. Thyroid hormones as suppression therapy were administered. Three months after diagnosis, therapy with radioactive iodine was started. In total, the man received five cycles with radioactive iodine. Five years after diagnosis, the patient still has a stable disease. The last PET-CT scan showed no glucose-metabolizing lesions.

Malignancies in patients with Cystic Fibrosis at the CF Centre Innsbruck

- n number, CFTR cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator, ppFEV1 percent predicted forced expiratory volume in one second, CIN Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

In total, we report ten female patients and one male patient with CF and cancer. The patients had a mean age of 24.3 years, about half of the patients were phe508del homozygous, and more than half had died by the end of our observation. The mean of the most recent lung function before cancer diagnosis showed a forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV 1 ) of 78.6% of predicted normal value.

Among 229 patients with cystic fibrosis visiting our CF Centre between 1995 and 2019, 11 cases of cancer were diagnosed, mainly in the third decade of life. Ten patients were female, four of whom had cervical cancer or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Six women died from cancer. Cancer screening could potentially prevent early deaths and should be included in routine diagnostics for adults with cystic fibrosis.

This is the largest case series of CF patients with cancer diagnoses. Previous reports show that patients with CF carry an increased risk for gastrointestinal cancer, and they appear to have an earlier onset of cancer than otherwise healthy adults [ 6 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. The patients in our case series had a mean age of only 24.3 years at cancer diagnosis. For cervical cancer, the average age at diagnosis worldwide in 2018 was 53 years, while our four patients were much younger when diagnosed at 25–39 years of age [ 16 ].

The lung function of the patients before malignancy diagnosis was mostly normal despite cystic fibrosis, with a mean forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV 1 ) of 78.6 % of the predicted normal value. According to recent European CF Registry data, mean FEV 1 % predicted for patients aged 18 years or older without a transplant is 68.5% [ 17 ]. Only one death (case 6) was associated with severe CF lung disease and pulmonary hemorrhage. Thus, cancer shortened life considerably in half of the patients.

The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation recommends to start colonoscopy as a screening for colorectal cancer in patients with CF starting at the age of 40 years [ 18 ]. In our patient group, only one patient was diagnosed with gastrointestinal cancer (peritoneal mesothelioma, case 7), while more patients had gynecological or hematological malignancies. The low number of colorectal cancers in our subgroup may be due to the screening programme at our center, with colonoscopy and therapeutic polypectomy on a regular basis starting at the age of 40 years.

From a total of 11 cases, we report 4 cases of cervical cancer or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in 229 CF patients over a period of 24 years (mean age 30.6 years). This corresponds to a rate of 0.073% of patients per year. The incidence rate of cervical cancer per year (mean of 1995–2018) in the general population in Tyrol, Austria, where the CF Centre Innsbruck is located, is 0.0015% for the same age range [ 19 ]. This is a 49-times-higher incidence of cervical cancer in our collective compared with the general population in the same region for the same age range. Significant expression of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene in the cervical epithelium has been reported [ 20 ]. An analysis of Pap smear tests in women with CF also showed a high proportion of abnormal tests and cervical dysplasia [ 21 ]. Considerably higher expression of CFTR in ovarian cancer was seen in vitro and in vivo , so downregulation of CFTR or dysfunctional CFTR should suppress aggressive malignant biological behaviors of ovarian cancer cells [ 22 ]. However, compared with cells from normal endometrium, the expression of CFTR was significantly upregulated in endometrial carcinoma cells, which could result in increased proliferation and transfer of endometrial carcinoma cells [ 23 ]. Due to CFTR dysfunction in the cervix, women with CF have an abnormally thick and dense cervical mucus [ 24 ]. The squamocolumnar junction is prone to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and cell dysfunction [ 24 ].

The CFTR plays a role in multiple cellular processes, such as development, epithelial differentiation and polarization, regeneration, migration, proliferation, and epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Several studies suggest that CFTR exerts variable effects in different tissues and in different cancer types. Especially downregulation of CFTR seems to lead to tumorigenesis and invasiveness of tumors, but the exact mechanisms are still unknown [ 25 ]. The correlation between CF and a higher risk for gastrointestinal cancer may be explained by chronic inflammation, dysmotility, and altered fecal microbiome in the gut [ 7 , 15 , 26 ].

Another potential risk factor for cancers in cystic fibrosis is transplantation. After organ replacement, CF patients were shown to have an overall increased risk of cancer and specifically an elevated risk of gastrointestinal malignancy and lymphoma. This has largely been attributed to the intense, long-term immunosuppressive medication [ 5 ]. In our case series, only 1 of 11 patients had received a lung transplant.

Frequent exposure to radiation could be an additional reason for increased cancer risk. In most centers, patients receive chest X-rays on a yearly basis and further imaging in case of pulmonary exacerbations. At our center, we perform ultra-low-dose high-resolution chest tomography to document any progression of lung disease. Nevertheless, we are very aware of the fact that routine use of computed tomography needs to be done with great care for future implications [ 27 ]. In the future, CT may be replaced by MRI imaging for monitoring of pulmonary structural changes and inflammation [ 28 ].

Only a few studies record the occurrence of cancer in patients with CF over a longer period of time, and through our database we had access to 24 years of patient data. However, this is a retrospective study with a small patient collective, during a time where the treatment of CF is constantly developing. Since the association of some cancer types such as gastrointestinal cancer with CF is clear, other cancers such as neuroblastoma or leukemia may appear coincidental. No association between neuroblastoma and CF is known; only three cases of CF and neuroblastoma have been reported in literature [ 29 , 30 ], and no causality is assumed.

Further studies about cancer risk in patients with CF and a larger patient collective are needed. Ideally, the data could be obtained from national patient registries. Improvement of life expectancy in patients with CF increases the expected absolute risk of malignancies; therefore, it is necessary to integrate screening in the care of patients with CF.

Our data suggest an increased risk for gynecological malignancies. Considering the role of CFTR in endometrial carcinoma cells [ 31 ] and in the cervical epithelium, intensified screening for women with CF, compared with healthy women, may be reasonable, as well as routine HPV vaccination. In light of this, we recommend screening for gastrointestinal and gynecological malignancies. Special alertness for malignant diseases is obviously needed in patients after transplantation due to long-term immunosuppression. Screening for other types of malignant tumors should be included in the regular follow-up of adult patients. The role of CFTR in risk of cancer may change considering the effect of new CFTR modulator therapies on CFTR, and this needs to be investigated in further studies.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Acute lymphocytic leukemia

Common acute lymphoblastic leucemia Type II B

- Cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

Cervical glandular intraepithelial neoplasia

Central nervous system

Computer tomography

Distal intestinal obstruction syndrome

Human papillomavirus

Intensive care unit

Magnetic resonance imaging

Positron emission tomography

Parkins MD, Parkins VM, Rendall JC, Elborn S. Changing epidemiology and clinical issues arising in an ageing cystic fibrosis population. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2011;5(2):105–19.

Article Google Scholar

Neglia JP, Wielinski CL, Warwick WJ. Cancer risk among patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 1991;119(5):764–6.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Johannesson M, Askling J, Montgomery SM, Ekbom A, Bahmanyar S. Cancer risk among patients with cystic fibrosis and their first-degree relatives. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(12):2953–6.

Schöni MH, Maisonneuve P, Schöni-Affolter F, Lowenfels AB. Cancer risk in patients with cystic fibrosis: the European data. CF/CSG Group. J R Soc Med. 1996;89(Suppl 27):38–43.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Maisonneuve P, FitzSimmons SC, Neglia JP, Campbell PW, Lowenfels AB. Cancer risk in nontransplanted and transplanted cystic fibrosis patients: a 10-year study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(5):381–7.

Hough NE, Chapman SJ, Flight WG. Gastrointestinal malignancy in cystic fibrosis. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2020;35:90–2.

PubMed Google Scholar

Maisonneuve P, Marshall BC, Knapp EA, Lowenfels AB. Cancer risk in cystic fibrosis: a 20-year nationwide study from the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(2):122–9.

Neglia JP, FitzSimmons SC, Maisonneuve P, Schöni MH, Schöni-Affolter F, Corey M, et al. The risk of cancer among patients with cystic fibrosis. Cystic Fibrosis and Cancer Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(8):494–9.

Sheldon CD, Hodson ME, Carpenter LM, Swerdlow AJ. A cohort study of cystic fibrosis and malignancy. Br J Cancer. 1993;68(5):1025–8.

Abraham JM, Taylor CJ. Cystic fibrosis & disorders of the large intestine: DIOS, constipation, and colorectal cancer. J Cyst Fibros. 2017;16(Suppl 2):S40–9.

Garg M, Ooi CY. The enigmatic gut in cystic fibrosis: linking inflammation, dysbiosis, and the increased risk of malignancy. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19(2):6.

Hegagi M, Aaron SD, James P, Goel R, Chatterjee A. Increased prevalence of colonic adenomas in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2017;16(6):759–62.

McKenna PB, Mulcahy E, Waldron D. Early onset of colonic adenocarcinoma associated with cystic fibrosis—a case report. Ir Med J. 2006;99(10):310–1.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Meyer KC, Francois ML, Thomas HK, Radford KL, Hawes DS, Mack TL, et al. Colon cancer in lung transplant recipients with CF: increased risk and results of screening. J Cyst Fibros. 2011;10(5):366–9.

Yamada A, Komaki Y, Komaki F, Micic D, Zullow S, Sakuraba A. Risk of gastrointestinal cancers in patients with cystic fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(6):758–67.

Arbyn M, Weiderpass E, Bruni L, de Sanjosé S, Saraiya M, Ferlay J, et al. Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(2):e191–203.

Zolin A, Orenti A, Naehrlich L, Jung A, van Rens J, et al. ECFSPR Annual Report 2018; 2020.

Hadjiliadis D, Khoruts A, Zauber AG, Hempstead SE, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB. Cystic fibrosis colorectal cancer screening consensus recommendations. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(3):736-745.e14.

Statistik Austria. Österreichisches Krebsregister (Stand:17.12.2021) [cited 2021 Mar 22]. https://www.statistik.at .

Tizzano EF, Silver MM, Chitayat D, Benichou JC, Buchwald M. Differential cellular expression of cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator in human reproductive tissues. Clues for the infertility in patients with cystic fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 1994;144(5):906–14.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rousset-Jablonski C, Reynaud Q, Nove-Josserand R, Ray-Coquard I, Mekki Y, Golfier F, et al. High proportion of abnormal pap smear tests and cervical dysplasia in women with cystic fibrosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;221:40–5.

Wu Z, Peng X, Li J, Zhang Y, Hu L. Constitutive activation of nuclear factor κB contributes to cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator expression and promotes human cervical cancer progression and poor prognosis. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23(5):906–15.

Xia X, Wang J, Liu Y, Yue M. Lower cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) promotes the proliferation and migration of endometrial carcinoma. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:966–74.

Edenborough FP. Women with cystic fibrosis and their potential for reproduction. Thorax. 2001;56(8):649–55.

Amaral MD, Quaresma MC, Pankonien I. What role does CFTR play in development, differentiation, regeneration and cancer? Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(9):3133.

Slae M, Wilschanski M. Cystic fibrosis: a gastrointestinal cancer syndrome. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(6):719–20.

de González BA, Mahesh M, Kim K-P, Bhargavan M, Lewis R, Mettler F, et al. Projected cancer risks from computed tomographic scans performed in the United States in 2007. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(22):2071–7.

Woods JC, Wild JM, Wielpütz MO, Clancy JP, Hatabu H, Kauczor H-U, et al. Current state of the art MRI for the longitudinal assessment of cystic fibrosis. J Magn Reson Imag. 2019;52:1306–20.

Naselli A, Cresta F, Favilli F, Casciaro R. A long-term follow-up of residual mass neuroblastoma in a patient with cystic fibrosis. BMJ Case Rep 2015; 2015.

Moss RB, Blessing-Moore J, Bender SW, Weibel A. Cystic fibrosis and neuroblastoma. Pediatrics. 1985;76(5):814–7.

Xu J, Yong M, Li J, Dong X, Yu T, Fu X, et al. High level of CFTR expression is associated with tumor aggression and knockdown of CFTR suppresses proliferation of ovarian cancer in vitro and in vivo . Oncol Rep. 2015;33(5):2227–34.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Johannes Eder, M.D. for assistance with data collection, Katharina Niedermayr, M.D. for reviewing the manuscript, and Nikelwa Theileis, M.A. for proofreading.

There were no sources of funding for this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Medical University of Innsbruck, Cystic Fibrosis Centre Innsbruck, 6020, Innsbruck, Austria

Dorothea Appelt, Teresa Fuchs, Gratiana Steinkamp & Helmut Ellemunter

Clinical Research and Medical Scientific Writing, Schwerin, Germany

Gratiana Steinkamp

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Dorothea Appelt .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's legal guardian or next of kin for publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Appelt, D., Fuchs, T., Steinkamp, G. et al. Malignancies in patients with cystic fibrosis: a case series. J Med Case Reports 16 , 27 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-03234-1

Download citation

Received : 05 February 2021

Accepted : 19 December 2021

Published : 19 January 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-03234-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mucoviscidosis

Journal of Medical Case Reports

ISSN: 1752-1947

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Global health

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 14, Issue 11

- Cystic fibrosis: a diagnosis in an adolescent

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9674-0879 Monica Bennett 1 ,

- Andreia Filipa Nogueira 1 ,

- Maria Manuel Flores 2 and

- Teresa Reis Silva 1

- 1 Pediatric , Centro Hospitalar e Universitario de Coimbra EPE , Coimbra , Portugal

- 2 Pediatric , Centro Hospitalar do Baixo Vouga EPE , Aveiro , Aveiro , Portugal

- Correspondence to Dr Monica Bennett; acinomaicila{at}gmail.com

Most patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) develop multisystemic clinical manifestations, the minority having mild or atypical symptoms. We describe an adolescent with chronic cough and purulent rhinorrhoea since the first year of life, with diagnoses of asthma, allergic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis. Under therapy with long-acting bronchodilators, antihistamines, inhaled corticosteroids, antileukotrienes and several courses of empirical oral antibiotic therapy, there was no clinical improvement. There was no reference to gastrointestinal symptoms. Due to clinical worsening, extended investigations were initiated, which revealed Pseudomonas aeruginosa in sputum culture, sweat test with a positive result and heterozygosity for F508del and R334W mutations in genetic study which allowed to confirm the diagnosis of CF. In this case, heterozygosity with a class IV mutation can explain the atypical clinical presentation. It is very important to consider this diagnosis when chronic symptoms persist, despite optimised therapy for other respiratory pathologies and in case of isolation of atypical bacterial agents.

- cystic fibrosis

- pneumonia (respiratory medicine)

https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2021-245971

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

A high degree of diagnostic suspicion is of fundamental importance when chronic symptoms persist, despite optimised therapy for previous diagnoses and in case of isolation of atypical bacterial agents in microbiological studies.

This case describes an adolescent with a chronic cough since the first year of life, adequate weight gain and normal pubertal development, without improvement with optimised therapy for other respiratory pathologies. There was no reference to gastrointestinal symptoms. There was clinical worsening at 13 years of age and isolation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in sputum culture. After extensive investigation, including sweat test and genetic study, it was possible to confirm the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis (CF).

Case presentation

A 13-year-old female teenager presented with chronic cough and purulent rhinorrhoea with periods of intermittent clinical worsening with associated fever since the first year of life. This was accompanied by various medical specialties, with diagnoses of asthma, allergic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis. She was under therapy with long-acting bronchodilators, antihistamines, inhaled corticosteroids, and antileukotrienes and submitted to several courses of empirical oral antibiotic therapy, without sustained and effective clinical improvement. She presented an adequate height–weight evolution, with a body mass index (BMI) at 50th−85th percentile and normal pubertal development, no reference to gastrointestinal symptoms or previous hospitalisations. Her family background was irrelevant. Due to clinical worsening, with emetising cough associated with intermittent fever and night sweats, a pulmonary CT scan was performed, which revealed parenchymal densification, air bronchogram, thickened bronchi, mucoid impaction and mediastinal adenopathies. Observed in the emergency department, the objective examination highlighted bibasal crackles on pulmonary auscultation, without other alterations. She was treated with clarithromycin, later associated with co-amoxiclav. An extended investigation was initiated, which revealed erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 52 mm/hour, C reactive protein test of 4.10 mg/dL, negative BK and interferon gamma release assay test, and isolation of P. aeruginosa in sputum culture. The antibiotic therapy was changed to ciprofloxacin and sweat tests were performed with positive results on two occasions (102 and 110 mmol/L). Later, a genetic study revealed heterozygosity for the F508del and R334W mutations, which confirmed the diagnosis of CF. Faecal elastase was performed, and the result was normal (>500 µg/g).

After antimicrobial therapy with ciprofloxacin, she maintained P. aeruginosa, and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) was now discovered in the sputum. For this reason, she was hospitalised for intravenous eradication. After 2 weeks of antibiotic therapy with meropenem, gentamicin and teicoplanin, P. aeruginosa was eradicated but not MSSA. Linezulide was prescribed for 2 weeks, with a good response, and the microbiological study was negative.

Outcome and follow-up

During the follow-up period (2 years), she continued having frequent respiratory infections, with isolation of P. aeruginosa and MSSA in respiratory secretions intermittently, requiring the need for several courses of antibiotic therapy. The antibiogram of P. aeruginosa has remained sensible. Currently, she continues follow-up in a specialised fibrosis cystic centre, under inhaled therapy with colistin/tobramycin, hypertonic saline, salbutamol, dornase alfa, budesonide/formoterol, chest physiotherapy and oral azithromycin prophylaxis. Her pulmonary function is normal with a currently forced expiratory volume in 1 s of 87% and she shows adequate height−weight evolution, with BMI maintained at P50–85. The sweat chloride test was not repeated after confirmed diagnosis.

CF is one of the most commonly diagnosed genetic disorders 1 and the most common life-shortening autosomal recessive disease among Caucasian populations, with a frequency of 1 in 2000–3000 live births. 2 CF is caused by mutations in a single large gene on chromosome 7 that encodes the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator ( CFTR ) protein.

There are more than 2000 mutations/variations of the CFTR gene reported and listed in the CFTR mutation database. A small subset are CF disease-causing mutations, of which the majority are associated with pancreatic insufficiency and a smaller subset are associated with pancreatic sufficiency. Most of the known mutations/variations related to CF are described in the CFTR2 database (Clinical and Functional Translation of CFTR). This website provides information about what is currently known about specific genetic variants or variant combination and is a useful resource to correlate clinical measures to the large number of variants identified to date. 3 4

Clinical disease requires disease-causing mutations in both copies of the CFTR gene. Mutations of the CFTR gene have been divided into five different classes. The most common mutation is F508del which is included in category class II mutations—defective protein processing. Approximately 50% of patients with CF are homozygous for this mutation, and 90% will carry at least one copy of this gene. In general, mutations in classes I−III cause more severe disease than those in classes IV and V. Class IV and V mutations are associated with moderate phenotypes and pancreatic sufficiency. 5 The R334W is a rare mutation included in class IV—defective conduction and associated with pancreatic sufficiency. 5 6 Those with less severe mutations present with pancreatic sufficiency and single organ manifestations of CF. Some of these patients would fulfil the diagnostic criteria for CF and some would be classified as having a CFTR-related disorder if the diagnosis of CF cannot be fulfilled. 7

The phenotypic expression of disease varies widely, based on CFTR-related (genotype-related) and non-CFTR-related factors (environmental and other genetic modifiers). Genotype–phenotype correlations are weak for pulmonary disease in CF and somewhat stronger for the pancreatic insufficiency phenotype. 5

Many studies in different individuals heterozygous for CFTR gene mutation have been performed to find out the association of CFTR gene mutation with asthma. The results are inconclusive, as some of the studies have shown positive association, whereas other could find either protective or no association. 8 Also, at this time, there is no evidence for a specific association between CFTR gene mutation and other allergic manifestations.

Clinical manifestations are multisystemic and heterogeneous. 9 The first symptoms of the disease usually appear in the first years of life, and most patients develop a multisystem disease, with predominantly respiratory and digestive symptoms. 2 5 10 The usual presenting symptoms and signs include persistent pulmonary infection, pancreatic insufficiency and elevated sweat chloride levels. However, many patients demonstrate mild or atypical symptoms, and clinicians should remain alert to the possibility of CF even when only a few of the usual features are present. 2 Progressive pulmonary involvement is the main cause of morbidity and mortality. Clinically significant pancreatic insufficiency eventually develops in approximately 85% of individuals with CF. The remaining 10%–15% of patients with CF remain pancreatic sufficient throughout childhood and early adulthood, but these individuals are at risk of pancreatitis. Pancreatic exocrine function may be evaluated indirectly by measurement of faecal elastase, which is clinically practical but has limited accuracy. Low levels of faecal elastase suggest pancreatic insufficiency and support a diagnosis of CF. 2 5 11–13

The diagnosis of CF is based on compatible clinical findings with biochemical or genetic confirmation. The sweat chloride test is the mainstay of laboratory confirmation, although tests for specific mutations, nasal potential difference (NPD), immunoreactive trypsinogen, stool faecal fat or pancreatic enzyme secretion may also be useful in some cases.

Both of the following criteria must be met to diagnose CF: (1) clinical symptoms consistent with CF in at least one organ system, or positive newborn screen or having a sibling with CF; and (2) evidence of cystic CFTR dysfunction (any of the following): elevated sweat chloride ≥60 mmol/L; presence of two disease-causing mutations in the CFTR gene, one from each parental allele; abnormal NPD.

Sweat chloride test ≥60 mmol/L is considered abnormal. If confirmed on a second occasion, this is sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of CF in patients with clinical symptoms of CF. Positive results of sweat testing should be further evaluated by CFTR sequencing. Determining the CFTR genotype is important because the results may affect treatment choices as well as confirm the diagnosis. For patients with inconclusive results of sweat chloride and DNA testing, measurement of NPD can be used to further evaluate for CFTR dysfunction. 5 14

Newborn screening programmes for CF are now performed routinely in several countries, which contributed to a dramatic increase in the number of CF cases identified before presenting with symptoms. The rationale for this screening is that early detection of CF may lead to earlier intervention and improved outcomes because the affected individuals are diagnosed, referred and treated earlier in life compared with individuals who are diagnosed after presenting with symptomatic CF. In Portugal and some other European countries, this programme was implemented less than 10 years ago, contributing to a late diagnosis in older children.

There are different neonatal screening programmes that include biochemical screening and/or DNA assays with panels to test for the most common CFTR mutations in the local population. Most programmes test for between 23 and 40 mutations, and some programmes even perform adjunctive full gene sequencing. Screening for a greater number of mutations increases the likelihood of identifying infants with CF and also increases the identification of rare or unique sequence mutations, making interpretation of the result more complicated. As only a limited number of mutations are evaluated on the genetic screens, it is possible to miss the diagnosis. Thus, it is important to follow such children closely, with particular attention to weight gain and recurrent respiratory infections. Clinicians should consider CF in individuals with suggestive symptoms, even when results of the newborn screen are negative or equivocal. 5 14

In the case described here, heterozygosity with a class IV mutation, usually associated with an intermediate phenotype and pancreatic sufficiency, may explain the atypical clinical presentation and consequent diagnosis only in adolescents. We also hypothesise that this child’s allergic manifestations may have delayed the diagnosis.

As the spectrum of clinical presentation is very variable, it is very important for clinicians from multiple specialties to be vigilant and suspect this diagnosis in conditions such as recurrent pulmonary infection, male infertility, pancreatitis, nasal polyposis and malabsorption even in patients with negative newborn screening. 2 10 13

Learning points

There is a wide spectrum of manifestations of cystic fibrosis (CF). These variations and wide spectrum are based on cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)-related (genotype-related) and non-CFTR-related factors (environmental and other genetic modifiers).

Most patients with CF develop multisystemic and heterogeneous clinical manifestations, with predominantly respiratory and digestive symptoms.

A minority have mild or atypical symptoms.

Heterozygosity with a class IV mutation usually is associated with an intermediate phenotype and pancreatic sufficiency and can explain the atypical clinical presentation.

It is very important to consider this diagnosis when chronic symptoms persist, despite optimised therapy for other respiratory pathologies and in case of isolation of atypical bacterial agents in microbiological studies.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Consent obtained from parent(s)/guardian(s)

- Dickinson KM ,

- ↵ Cystic fibrosis mutation database . Available: http://www.genet.sickkids.on.ca/Home.html

- ↵ Clinical and functional translation of CFTR . Available: https://cftr2.org/

- Ellis L , et al

- Awasthi S ,

- Gartner S ,

- Salcedo Posadas A ,

- García Hernández G

- Castellani C ,

- Linnane B ,

- Pranke I , et al

- Farrell PM ,

- Ren CL , et al

- Kharrazi M ,

- Bishop T , et al

Contributors MB cared for study patient, planned and wrote the article. AFN collected data. MMF provided and cared for study patient, served as scientific advisors and critically reviewed the study proposal. TRS cared for study patient, served as scientific advisors and critically reviewed the study proposal.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 19: Case Study: Cystic Fibrosis

Julie M. Skrzat; Carole A. Tucker

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Introduction.

- Examination: Age 2 Months

- Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Prognosis

- Intervention

- Conclusion of Care

- Examination: Age 8 Years

- Examination: Age 16 Years

- Recommended Readings

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

C ystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive condition affecting approximately 30,000 Americans and 70,000 people worldwide. According to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation ( Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, 2019a ), approximately 1,000 new cases are diagnosed yearly in the United States, with a known incidence of 1 per 3,900 live births. The disease prevalence varies greatly by ethnicity, with the highest prevalence occurring in Western European descendants and within the Ashkenazi Jewish population.

The CF gene, located on chromosome 7, was first identified in 1989. The disease process is caused by a mutation to the gene that encodes for the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein. This mutation alters the production, structure, and function of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), a dependent transmembrane chloride channel carrier protein found in the exocrine mucus glands throughout the body. The mutated carrier protein is unable to transport chloride across the cell membrane, resulting in an electrolyte and charge imbalance. Diffusion of water across the cell membrane is thus impaired, resulting in the development of a viscous layer of mucus. The thick mucus obstructs the cell membranes, traps nearby bacteria, and incites a local inflammatory response. Subsequent bacterial colonization occurs at an early age and ultimately this repetitive infectious process leads to progressive inflammatory damage to the organs involved in individuals with CF.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Case report article, case report: cystic fibrosis with kwashiorkor: a rare presentation in the era of universal newborn screening.

- Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado Denver Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, United States

Background: Universal newborn screening changed the way medical providers think about the presentation of cystic fibrosis (CF). Before implementation of universal screening, it was common for children with CF to present with failure to thrive, nutritional deficiencies, and recurrent infections. Now, nearly all cases of CF are diagnosed by newborn screening shortly after birth before significant symptoms develop. Therefore, providers often do not consider this illness in the setting of a normal newborn screen. Newborn screening significantly decreases the risk of complications in early childhood, yet definitive testing should be pursued if a patient with negative newborn screening presents with symptoms consistent with CF, including severe failure to thrive, metabolic alkalosis due to significant salt losses, or recurrent respiratory infections.

Case presentation: We present a case of a 6-month-old infant male with kwashiorkor, severe edema, multiple vitamin deficiencies, hematemesis secondary to coagulopathy, and diffuse erythematous rash, all secondary to severe pancreatic insufficiency. His first newborn screen had an immunoreactive trypsinogen (IRT) value below the state cut-off value, so additional testing was not performed, and his growth trajectory appeared reassuring. He was ultimately diagnosed with CF by genetic testing and confirmatory sweat chloride testing, in the setting of his parents being known CF carriers and his severe presentation being clinically consistent with CF. Acutely, management with supplemental albumin, furosemide, potassium, and vitamin K was initiated to correct the presenting hypoalbuminemia, edema, and coagulopathy. Later, pancreatic enzyme supplementation and additional vitamins and minerals were added to manage ongoing deficiencies from pancreatic insufficiency. With appropriate treatment, his vitamin deficiencies and edema resolved, and his growth improved.

Conclusion: Due to universal newborn screening, symptomatic presentation of CF is rare and presentation with kwashiorkor is extremely rare in resource-rich communities. The diagnosis of CF was delayed in our patient because of a normal newborn screen and falsely reassuring growth, which after diagnosis was determined to be secondary to severe edematous malnutrition. This case highlights that newborn screening is a useful but imperfect tool. Clinicians should continue to have suspicion for CF in the right clinical context, even in the setting of normal newborn screen results.

Introduction

Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis (CF) in the United States was adopted in the early 1980s and became standard in all fifty states by 2010 ( 1 , 2 ). Prior to the implementation of universal newborn screening and in countries where newborn screening is not performed, many children were diagnosed with CF after developing symptoms including malnutrition, growth faltering, chronic cough, recurrent respiratory infections/pneumonias, rectal prolapse, and/or electrolyte and other nutritional abnormalities ( 1 ). Due to the success of newborn screening, clinicians in high resource settings have never seen a child present with symptomatic CF and may not consider CF when these symptoms occur.

Early diagnosis of CF has been shown to improve outcomes due to optimized nutrition and targeted interventions ( 3 ). Numerous studies over the years continually reconfirm that patients do better when diagnosis happens earlier ( 3 – 5 ). Improved growth, presumably secondary to early initiation of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy and other vitamin supplementation, leads to better pulmonary function throughout life as well as improved neurological outcomes into adolescence. Malnutrition in children with CF tends to lead to increased lung disease ( 3 ). Seventy percent of infants that were symptomatic at presentation had more hospitalizations in the first year of life and more complications, including growth faltering, positive Pseudomonas aeruginosa culture results, and electrolyte abnormalities when compared to patients diagnosed prenatally or via newborn screening ( 6 , 7 ). Decreased chronic infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa has also been observed since implementation of universal newborn screening ( 1 ) which leads to improved lung function.

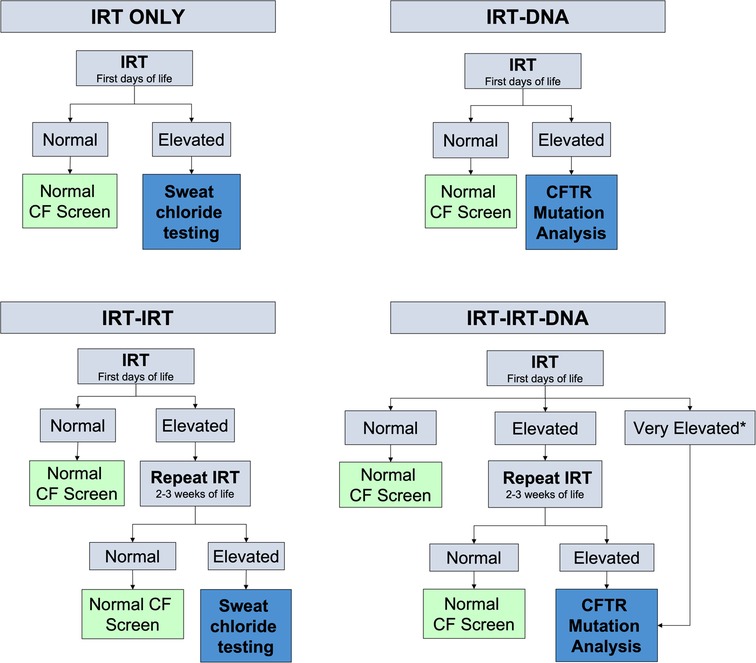

Newborn screening is performed with measurements of immunoreactive trypsinogen (IRT) and genetic testing but testing protocols vary from state to state ( 8 ) ( Figure 1 ). IRT is a pancreatic precursor enzyme that is elevated in patients with CF due to pancreatic duct blockage ( 9 ). An elevated IRT is not specific to CF and can be elevated in the absence of CF, particularly when infants are born premature, have low Apgar scores, or experience perinatal stress ( 3 ). In all states, an IRT level above a certain threshold is indicative of a positive screen; however, the cutoff varies and is not specified in the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics guidelines ( 10 ), allowing states to set their own threshold. Different procedures for newborn screening for CF include IRT-only, IRT-IRT, IRT-DNA, and IRT-IRT-DNA ( 8 , 9 , 11 ). IRT-only states measure IRT levels in blood samples from newborns collected around 2 weeks of life and if elevated, proceed directly to sweat testing. In IRT-IRT states, the first IRT sample is collected in the first few days of life and if abnormal, a repeat IRT will be collected. If the repeat IRT remains elevated, the next step is sweat chloride testing ( 11 ). In IRT-DNA states, the sample is typically collected in the first days of life and the sample is reflexively sent for DNA testing if the IRT level is above a particular threshold. In IRT-IRT-DNA states, the first sample is collected within 24 h of life, and if negative, no further testing is done. If the initial IRT is elevated in these states, IRT testing will be repeated on the second screen, sent around 2 weeks of life. If the IRT remains elevated, then reflex testing for mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene occurs, either with a panel of common genetic variants seen in that state or full genetic sequencing ( 12 ). For all states, patients flagged with abnormal newborn screens have a protocol for confirmatory testing with sweat chloride testing, which remains the gold standard for diagnosing cystic fibrosis ( 9 ). All states have varying, non-zero false negative rates, meaning that all states will intermittently miss true cases of CF on the screen. It is estimated that newborn screening with any IRT process identifies approximately 95%–99% of newborns with CF ( 13 ).

Figure 1 . Different algorithms for newborn screening processes measuring newborn IRT levels in blood spot testing. Levels for normal or elevated also vary depending on the state. *Some states have automatic CFTR mutation analysis if the IRT level is above a certain threshold.

Case presentation

A 6-month-old Caucasian male presented with 2 weeks of fussiness, fever, and decreased activity and one episode of hematochezia and hematemesis in the setting of 1 month of a progressively worsening rash that started in his diaper area and spread to the extremities, neck, and trunk ( Figure 2 ). There was no change in his rash with emollients or topical steroid use.

Figure 2 . Patient's lower extremities on presentation demonstrating edema and diffuse rash with scaly plaques and bullous areas.

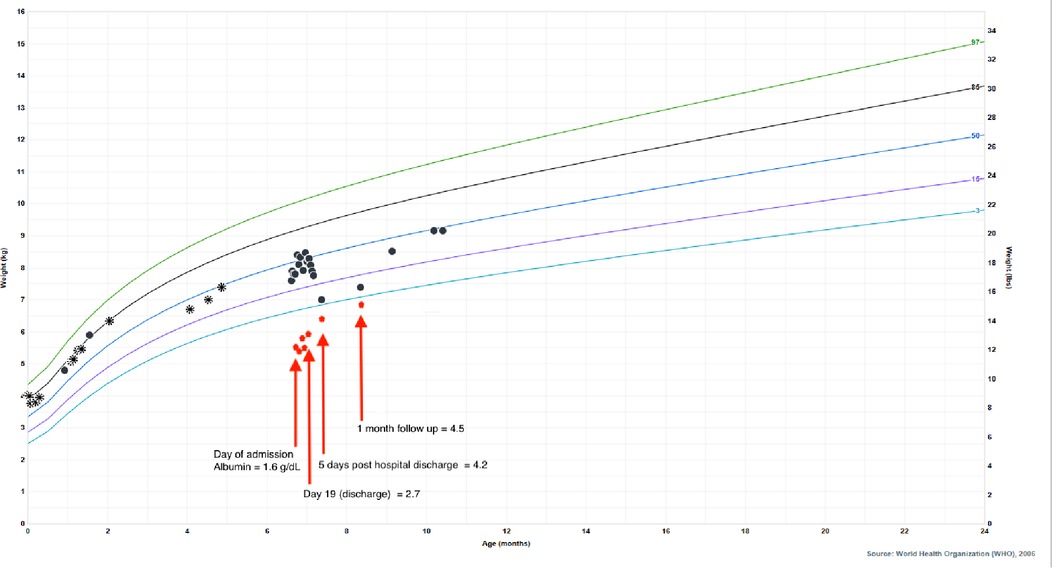

He was born full term without complications, passed meconium in the first 24 h of life, and had a normal newborn screen. His initial IRT was 59.3 ng/ml (normal <60 ng/ml), so no further testing was performed according to the state protocol. Parents were both identified as CF carriers during the pregnancy. His weight dropped from the 85th percentile at 2 months of age to the 33rd percentile at 4 months of age which coincided with a transition from exclusive direct breastfeeding to mostly bottle feeding of expressed breast milk. Weight gain from that point forward was consistent around the 35th percentile. His length, however, dropped from the 73rd percentile at 2 months of age to less than 3rd percentile at presentation at 6 months of age ( Figure 3 ). He was taking adequate volumes of breastmilk on demand about every 3–4 h with occasional reflux episodes. He was taking minimal solid foods at the time of admission. Vitamin D supplementation was inconsistent. His stooling pattern was reported as 3–4 times per day, soft consistency without malodor, discoloration, or oil droplets except for one episode of bright red blood per rectum immediately prior to admission. His mother reported she had concerns about constipation due to crying and fussiness with stooling. He had no respiratory symptoms such as cough or history of pneumonia.

Figure 3 . Patient's growth chart for weight from birth to present day with superimposed albumin values to highlight the impact of hypoalbuminemia on his falsely reassuring growth curve. Circle points indicate hospital system measurements, asterisk points indicate outside of hospital measurements. Albumin normal lab value range: 3.4–4.2 g/dl.

Physical examination on admission was remarkable for generalized edema (facial, periorbital, peripheral) with a diffuse, reddish-brown in color, serpiginous, rash with scaly plaques at his extremities and perineal area ( Figure 2 ). The rash was most prominent in the flexural surfaces with darker purple appearance in the intertriginous areas. There was an approximately three centimeter left inguinal mass with overlying purpura. His breathing was comfortable without any adventitious breath sounds, and his abdomen was soft, nontender, and without appreciable organomegaly, though this was difficult to assess due to his anasarca. His hair was thin and reddish in color.

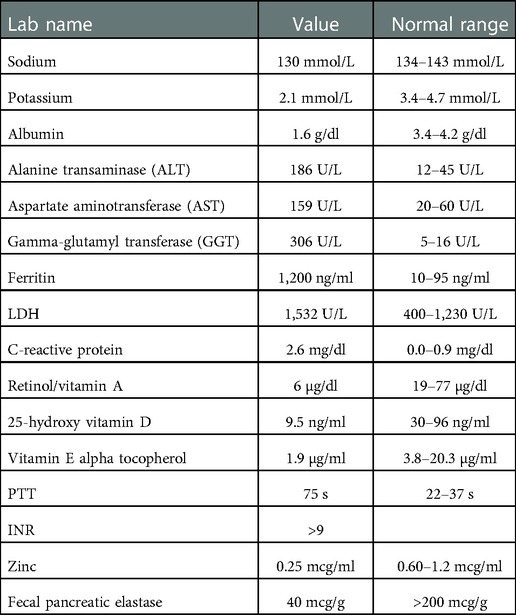

Labs were notable for coagulopathy, hypoalbuminemia, hyponatremia, elevated liver enzymes, elevated ferritin, elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), elevated c-reactive protein, decreased 25-hydroxy vitamin D level, decreased retinol/vitamin A level, decreased vitamin E alpha tocopherol level, and decreased zinc level ( Table 1 ). Stool was positive for occult blood. Due to multiple fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies, fecal pancreatic elastase was assessed and was low. His potassium was initially normal, but quickly dropped to 2.1 mmol/L on the second day of his hospitalization. He also tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on admission. Of note, his father had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 approximately 1 week prior to admission.

Table 1 . Labs values at the time of presentation with normal reference ranges.

He was admitted and diagnosed with kwashiorkor with prompt and cautious initiation of treatment for severe malnutrition, electrolyte derangements, and coagulopathy. Consultants involved included gastroenterology, hepatology, genetics/metabolism, allergy/immunology, cardiology, hematology, nutrition physicians, pulmonology, infectious disease, and dermatology. He received intravenous vitamin K and was initially started on continuous nasogastric feeds with breastmilk fortified with a high-protein extensively hydrolyzed formula. He received intravenous antibiotics for inguinal lymphadenopathy and cellulitis with intravenous antibiotics. Based on his very low fecal elastase measurements without diarrhea and his persistent edema and electrolyte derangements, he was started on empiric pancreatic enzymes on hospital day 10 pending a unifying diagnosis. Given the severity of his presentation and the broad differential diagnosis, rapid whole exome sequencing was pursued which identified two mutations in CFTR: F508del and 1717-1G->A, leading to a diagnosis of CF. No other genetic mutations were identified. A sweat chloride test was not obtained during his hospitalization due to the severity of his rash and electrolyte derangements but was performed about 1 month after hospitalization. One month after discharge, his sweat chloride levels were elevated at 86 and 90 mmol/L (normal <60 mmol/L) on his right and left arms respectively, confirming a diagnosis of CF.

Ultimately, his presenting diagnoses of kwashiorkor and coagulopathy were considered secondary to chronic CF-associated pancreatic insufficiency and malabsorption. Kwashiorkor explained his edema, hypoalbuminemia, elevated liver enzymes, hypoglycemia, malabsorption, thin and reddish hair, and rash. He demonstrated improvement with continuous nasogastric feeds of fortified breastmilk, supplemental fat-soluble vitamins, pancreatic enzymes, and electrolyte replacements. He was discharged home on 24 kcal/oz fortified oral and nasogastric feeds, DEKA vitamins, supplemental vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) and zinc, and pancreatic enzymes. Additionally, he was started on twice daily respiratory treatments with albuterol and chest physiotherapy. After diuresis, his weight dropped to the 4th percentile, which correlated with normalization of his albumin ( Figure 3 ), indicating that the appearance of his reassuring growth prior to presentation was weight gain secondary to edema and not true growth. After interventions, his weight appropriately increased and his stunted length began to normalize, signaling improved absorption and adequate nutrition. Growth measurements 5 months after hospitalization demonstrate significant recovery with weight at the 45th percentile, length at the 11th percentile, and weight-for-length at the 75th percentile.

Discussion and conclusion

Prior to newborn screening for CF, the average age at diagnosis was 2.9 years (in 1995) and children typically presented with malnutrition and growth faltering ( 14 ). Additionally, a symptomatic presentation could include dehydration, steatorrhea or abnormal stools, electrolyte abnormalities, recurrent respiratory infections and sinus disease, or meconium ileus at birth. Electrolyte derangements most commonly included hyponatremic, hypochloremic, and hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis along with hypoproteinemia and edema ( 15 ). Fat soluble vitamin deficiencies were common due to pancreatic insufficiency. It is now well-known that CF outcomes are improved in patients who are diagnosed earlier in life ( 1 , 14 ). In the early 1990s, Farrell et al. demonstrated that patients diagnosed earlier had significantly higher height and weight percentiles not only at the time of diagnosis, but also during the 10-year follow up period. They also found that patients diagnosed by newborn screening rather than symptoms had less severe lung disease during childhood ( 14 ). Today, most individuals with CF are diagnosed through newborn screening and subsequent confirmatory testing. The 2021 United States Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Registry Annual Data Report, as expected, reports that the majority of those diagnosed with CF in the first year of life are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic due to newborn screening, DNA analysis, and prenatal testing ( 16 ). This means that the current generation of providers, particularly general practitioners, are not familiar with symptomatic presentation. Being unable to recognize symptomatic presentation of CF means that questionable symptoms may go unnoticed for longer in the setting of a normal newborn screen. Cases of CF presenting with kwashiorkor secondary to severe pancreatic insufficiency were documented prior to newborn screening and continue to be reported occasionally in low-resource communities ( 17 – 19 ). Kwashiorkor is a form of severe protein energy malnutrition seen in infants and young children and is more prevalent in low resource communities ( 20 , 21 ). Manifestations can involve all body systems and are notable for peripheral pitting edema, marked muscle atrophy, depletion of fat stores, low weight-for-height, reduced mid-upper arm circumference, thin and dry skin, rash, dry hypopigmented hair, hepatomegaly from fatty liver infiltrates with abdominal distention, bradycardia, hypotension, and hypothermia ( 20 ). Other less commonly seen features include elevated liver enzymes, low serum concentrations of trace metals, and elevated ferritin concentrations ( 20 ). With implementation of universal newborn screening in the United States, CF presenting with kwashiorkor is now rarely seen, and as such, providers may not consider CF on the differential. According to the 2021 CF Registry Annual Data Report, no infants with CF have presented with edema at the time of diagnosis, highlighting the rarity of kwashiorkor ( 16 ). Our patient was receiving adequate intake by volume as assessed by parent report, leading to the concern that his kwashiorkor had an underlying cause rather than chronic inadequate intake.

Many patients with CF-related kwashiorkor have the characteristic kwashiorkor dermatosis: a rash with diffuse erythematous plaques, desquamation, and hyperpigmentation followed by peeling ( 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 ). Similar appearing rashes can occur in patients with essential fatty acid deficiency ( 24 ) or severe zinc deficiency, particularly, acrodermatitis enteropathica, a rare genetic condition where intestinal zinc absorption is impaired ( 23 , 25 , 26 ). These diagnoses should also be considered, and a thorough dietary history is extremely important.