Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders pp 980–981 Cite as

Direct Observation

- Anne Holmes M.S., C.C.C., B.C.B.A. 2

- Reference work entry

4273 Accesses

3 Citations

Direct observation, also known as observational study, is a method of collecting evaluative information in which the evaluator watches the subject in his or her usual environment without altering that environment. Direct observation is used when other data collection procedures, such as surveys, questionnaires, etc., are not effective; when the goal is to evaluate an ongoing behavior process, event, or situation; or when there are physical outcomes that can be readily seen.

Direct observation can be overt, when the subject and individuals in the environment know the purpose of the observation, or covert, when the subject and individuals in the environment are unaware of the purpose of the observation.

Structured direct observations are most appropriate when standardized information needs to be gathered, and result in quantitative data. Unstructured direct observation looks at natural occurrence and provides qualitative data, such as that used when administering the Childhood...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

References and Readings

Barnhill, G. P. (2002). Behavioral, social and emotional assessment of students with asd. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 27 (n1–2), 47–55.

Article Google Scholar

Carr, E. G., Ladd, M. V., & Schulte, C. F. (2008). Validation of the contextual assessment inventory for problem behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 10 , 91–104.

Drury, C. G. (1995). Methods for direct observation of performance. In J. R. Wilson & E. N. Corlett (Eds.), Evolution of human work; a practical ergonomics methodology (2nd ed., pp. 45–68). Philadelphia: Taylor and Francis.

Google Scholar

Matson, J. L., & Wilkins, J. (2007). A critical review of assessment targets and methods for social skill excesses and deficits for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 1 , 28–37.

Noterdaeme, M., Mildenberger, K., Sitter, S., & Amorosa, H. (2002). Parent information and direct observation in the diagnosis of pervasive and specific developmental disorders. Autism , 6 (2), 159–168. Abstract retrieved from http://www.online.sagepub.com

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Eden Autism Services, 2 Merwick Road, 08540, Princeton, NJ, USA

Anne Holmes M.S., C.C.C., B.C.B.A. ( Chief Clinical Officer )

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Anne Holmes M.S., C.C.C., B.C.B.A. .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Irving B. Harris Professor of Child Psychiatry, Pediatrics and Psychology Yale University School of Medicine, Chief, Child Psychiatry Children's Hospital at Yale-New Haven Child Study Center, New Haven, CT, USA

Fred R. Volkmar ( Director, Child Study Center ) ( Director, Child Study Center )

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Holmes, A. (2013). Direct Observation. In: Volkmar, F.R. (eds) Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1698-3_1758

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1698-3_1758

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-1-4419-1697-6

Online ISBN : 978-1-4419-1698-3

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Direct Observation Methods: a Practical Guide for Health Researchers

Affiliations.

- 1 VA Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research, Boston and Bedford, MA, USA.

- 2 Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA.

- 3 Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA, USA.

- 4 Department of Psychology, University of Maine, Orono, ME, USA.

- 5 Department of Public Health, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell, MA, USA.

- PMID: 36406296

- PMCID: PMC9670254

- DOI: 10.1016/j.pecinn.2022.100036

Objective: To provide health research teams with a practical, methodologically rigorous guide on how to conduct direct observation.

Methods: Synthesis of authors' observation-based teaching and research experiences in social sciences and health services research.

Results: This article serves as a guide for making key decisions in studies involving direct observation. Study development begins with determining if observation methods are warranted or feasible. Deciding what and how to observe entails reviewing literature and defining what abstract, theoretically informed concepts look like in practice. Data collection tools help systematically record phenomena of interest. Interdisciplinary teams--that include relevant community members-- increase relevance, rigor and reliability, distribute work, and facilitate scheduling. Piloting systematizes data collection across the team and proactively addresses issues.

Conclusion: Observation can elucidate phenomena germane to healthcare research questions by adding unique insights. Careful selection and sampling are critical to rigor. Phenomena like taboo behaviors or rare events are difficult to capture. A thoughtful protocol can preempt Institutional Review Board concerns.

Innovation: This novel guide provides a practical adaptation of traditional approaches to observation to meet contemporary healthcare research teams' needs.

Keywords: Direct Observation; Ethnography; Health Services Research; Methods; Qualitative Methods.

Grants and funding

- IK2 HX001783/HX/HSRD VA/United States

Designing and Conducting Case Studies

This guide examines case studies, a form of qualitative descriptive research that is used to look at individuals, a small group of participants, or a group as a whole. Researchers collect data about participants using participant and direct observations, interviews, protocols, tests, examinations of records, and collections of writing samples. Starting with a definition of the case study, the guide moves to a brief history of this research method. Using several well documented case studies, the guide then looks at applications and methods including data collection and analysis. A discussion of ways to handle validity, reliability, and generalizability follows, with special attention to case studies as they are applied to composition studies. Finally, this guide examines the strengths and weaknesses of case studies.

Definition and Overview

Case study refers to the collection and presentation of detailed information about a particular participant or small group, frequently including the accounts of subjects themselves. A form of qualitative descriptive research, the case study looks intensely at an individual or small participant pool, drawing conclusions only about that participant or group and only in that specific context. Researchers do not focus on the discovery of a universal, generalizable truth, nor do they typically look for cause-effect relationships; instead, emphasis is placed on exploration and description.

Case studies typically examine the interplay of all variables in order to provide as complete an understanding of an event or situation as possible. This type of comprehensive understanding is arrived at through a process known as thick description, which involves an in-depth description of the entity being evaluated, the circumstances under which it is used, the characteristics of the people involved in it, and the nature of the community in which it is located. Thick description also involves interpreting the meaning of demographic and descriptive data such as cultural norms and mores, community values, ingrained attitudes, and motives.

Unlike quantitative methods of research, like the survey, which focus on the questions of who, what, where, how much, and how many, and archival analysis, which often situates the participant in some form of historical context, case studies are the preferred strategy when how or why questions are asked. Likewise, they are the preferred method when the researcher has little control over the events, and when there is a contemporary focus within a real life context. In addition, unlike more specifically directed experiments, case studies require a problem that seeks a holistic understanding of the event or situation in question using inductive logic--reasoning from specific to more general terms.

In scholarly circles, case studies are frequently discussed within the context of qualitative research and naturalistic inquiry. Case studies are often referred to interchangeably with ethnography, field study, and participant observation. The underlying philosophical assumptions in the case are similar to these types of qualitative research because each takes place in a natural setting (such as a classroom, neighborhood, or private home), and strives for a more holistic interpretation of the event or situation under study.

Unlike more statistically-based studies which search for quantifiable data, the goal of a case study is to offer new variables and questions for further research. F.H. Giddings, a sociologist in the early part of the century, compares statistical methods to the case study on the basis that the former are concerned with the distribution of a particular trait, or a small number of traits, in a population, whereas the case study is concerned with the whole variety of traits to be found in a particular instance" (Hammersley 95).

Case studies are not a new form of research; naturalistic inquiry was the primary research tool until the development of the scientific method. The fields of sociology and anthropology are credited with the primary shaping of the concept as we know it today. However, case study research has drawn from a number of other areas as well: the clinical methods of doctors; the casework technique being developed by social workers; the methods of historians and anthropologists, plus the qualitative descriptions provided by quantitative researchers like LePlay; and, in the case of Robert Park, the techniques of newspaper reporters and novelists.

Park was an ex-newspaper reporter and editor who became very influential in developing sociological case studies at the University of Chicago in the 1920s. As a newspaper professional he coined the term "scientific" or "depth" reporting: the description of local events in a way that pointed to major social trends. Park viewed the sociologist as "merely a more accurate, responsible, and scientific reporter." Park stressed the variety and value of human experience. He believed that sociology sought to arrive at natural, but fluid, laws and generalizations in regard to human nature and society. These laws weren't static laws of the kind sought by many positivists and natural law theorists, but rather, they were laws of becoming--with a constant possibility of change. Park encouraged students to get out of the library, to quit looking at papers and books, and to view the constant experiment of human experience. He writes, "Go and sit in the lounges of the luxury hotels and on the doorsteps of the flophouses; sit on the Gold Coast settees and on the slum shakedowns; sit in the Orchestra Hall and in the Star and Garter Burlesque. In short, gentlemen [sic], go get the seats of your pants dirty in real research."

But over the years, case studies have drawn their share of criticism. In fact, the method had its detractors from the start. In the 1920s, the debate between pro-qualitative and pro-quantitative became quite heated. Case studies, when compared to statistics, were considered by many to be unscientific. From the 1930's on, the rise of positivism had a growing influence on quantitative methods in sociology. People wanted static, generalizable laws in science. The sociological positivists were looking for stable laws of social phenomena. They criticized case study research because it failed to provide evidence of inter subjective agreement. Also, they condemned it because of the few number of cases studied and that the under-standardized character of their descriptions made generalization impossible. By the 1950s, quantitative methods, in the form of survey research, had become the dominant sociological approach and case study had become a minority practice.

Educational Applications

The 1950's marked the dawning of a new era in case study research, namely that of the utilization of the case study as a teaching method. "Instituted at Harvard Business School in the 1950s as a primary method of teaching, cases have since been used in classrooms and lecture halls alike, either as part of a course of study or as the main focus of the course to which other teaching material is added" (Armisted 1984). The basic purpose of instituting the case method as a teaching strategy was "to transfer much of the responsibility for learning from the teacher on to the student, whose role, as a result, shifts away from passive absorption toward active construction" (Boehrer 1990). Through careful examination and discussion of various cases, "students learn to identify actual problems, to recognize key players and their agendas, and to become aware of those aspects of the situation that contribute to the problem" (Merseth 1991). In addition, students are encouraged to "generate their own analysis of the problems under consideration, to develop their own solutions, and to practically apply their own knowledge of theory to these problems" (Boyce 1993). Along the way, students also develop "the power to analyze and to master a tangled circumstance by identifying and delineating important factors; the ability to utilize ideas, to test them against facts, and to throw them into fresh combinations" (Merseth 1991).

In addition to the practical application and testing of scholarly knowledge, case discussions can also help students prepare for real-world problems, situations and crises by providing an approximation of various professional environments (i.e. classroom, board room, courtroom, or hospital). Thus, through the examination of specific cases, students are given the opportunity to work out their own professional issues through the trials, tribulations, experiences, and research findings of others. An obvious advantage to this mode of instruction is that it allows students the exposure to settings and contexts that they might not otherwise experience. For example, a student interested in studying the effects of poverty on minority secondary student's grade point averages and S.A.T. scores could access and analyze information from schools as geographically diverse as Los Angeles, New York City, Miami, and New Mexico without ever having to leave the classroom.

The case study method also incorporates the idea that students can learn from one another "by engaging with each other and with each other's ideas, by asserting something and then having it questioned, challenged and thrown back at them so that they can reflect on what they hear, and then refine what they say" (Boehrer 1990). In summary, students can direct their own learning by formulating questions and taking responsibility for the study.

Types and Design Concerns

Researchers use multiple methods and approaches to conduct case studies.

Types of Case Studies

Under the more generalized category of case study exist several subdivisions, each of which is custom selected for use depending upon the goals and/or objectives of the investigator. These types of case study include the following:

Illustrative Case Studies These are primarily descriptive studies. They typically utilize one or two instances of an event to show what a situation is like. Illustrative case studies serve primarily to make the unfamiliar familiar and to give readers a common language about the topic in question.

Exploratory (or pilot) Case Studies These are condensed case studies performed before implementing a large scale investigation. Their basic function is to help identify questions and select types of measurement prior to the main investigation. The primary pitfall of this type of study is that initial findings may seem convincing enough to be released prematurely as conclusions.

Cumulative Case Studies These serve to aggregate information from several sites collected at different times. The idea behind these studies is the collection of past studies will allow for greater generalization without additional cost or time being expended on new, possibly repetitive studies.

Critical Instance Case Studies These examine one or more sites for either the purpose of examining a situation of unique interest with little to no interest in generalizability, or to call into question or challenge a highly generalized or universal assertion. This method is useful for answering cause and effect questions.

Identifying a Theoretical Perspective

Much of the case study's design is inherently determined for researchers, depending on the field from which they are working. In composition studies, researchers are typically working from a qualitative, descriptive standpoint. In contrast, physicists will approach their research from a more quantitative perspective. Still, in designing the study, researchers need to make explicit the questions to be explored and the theoretical perspective from which they will approach the case. The three most commonly adopted theories are listed below:

Individual Theories These focus primarily on the individual development, cognitive behavior, personality, learning and disability, and interpersonal interactions of a particular subject.

Organizational Theories These focus on bureaucracies, institutions, organizational structure and functions, or excellence in organizational performance.

Social Theories These focus on urban development, group behavior, cultural institutions, or marketplace functions.

Two examples of case studies are used consistently throughout this chapter. The first, a study produced by Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988), looks at a first year graduate student's initiation into an academic writing program. The study uses participant-observer and linguistic data collecting techniques to assess the student's knowledge of appropriate discourse conventions. Using the pseudonym Nate to refer to the subject, the study sought to illuminate the particular experience rather than to generalize about the experience of fledgling academic writers collectively.

For example, in Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman's (1988) study we are told that the researchers are interested in disciplinary communities. In the first paragraph, they ask what constitutes membership in a disciplinary community and how achieving membership might affect a writer's understanding and production of texts. In the third paragraph they state that researchers must negotiate their claims "within the context of his sub specialty's accepted knowledge and methodology." In the next paragraph they ask, "How is literacy acquired? What is the process through which novices gain community membership? And what factors either aid or hinder students learning the requisite linguistic behaviors?" This introductory section ends with a paragraph in which the study's authors claim that during the course of the study, the subject, Nate, successfully makes the transition from "skilled novice" to become an initiated member of the academic discourse community and that his texts exhibit linguistic changes which indicate this transition. In the next section the authors make explicit the sociolinguistic theoretical and methodological assumptions on which the study is based (1988). Thus the reader has a good understanding of the authors' theoretical background and purpose in conducting the study even before it is explicitly stated on the fourth page of the study. "Our purpose was to examine the effects of the educational context on one graduate student's production of texts as he wrote in different courses and for different faculty members over the academic year 1984-85." The goal of the study then, was to explore the idea that writers must be initiated into a writing community, and that this initiation will change the way one writes.

The second example is Janet Emig's (1971) study of the composing process of a group of twelfth graders. In this study, Emig seeks to answer the question of what happens to the self as a result educational stimuli in terms of academic writing. The case study used methods such as protocol analysis, tape-recorded interviews, and discourse analysis.

In the case of Janet Emig's (1971) study of the composing process of eight twelfth graders, four specific hypotheses were made:

- Twelfth grade writers engage in two modes of composing: reflexive and extensive.

- These differences can be ascertained and characterized through having the writers compose aloud their composition process.

- A set of implied stylistic principles governs the writing process.

- For twelfth grade writers, extensive writing occurs chiefly as a school-sponsored activity, or reflexive, as a self-sponsored activity.

In this study, the chief distinction is between the two dominant modes of composing among older, secondary school students. The distinctions are:

- The reflexive mode, which focuses on the writer's thoughts and feelings.

- The extensive mode, which focuses on conveying a message.

Emig also outlines the specific questions which guided the research in the opening pages of her Review of Literature , preceding the report.

Designing a Case Study

After considering the different sub categories of case study and identifying a theoretical perspective, researchers can begin to design their study. Research design is the string of logic that ultimately links the data to be collected and the conclusions to be drawn to the initial questions of the study. Typically, research designs deal with at least four problems:

- What questions to study

- What data are relevant

- What data to collect

- How to analyze that data

In other words, a research design is basically a blueprint for getting from the beginning to the end of a study. The beginning is an initial set of questions to be answered, and the end is some set of conclusions about those questions.

Because case studies are conducted on topics as diverse as Anglo-Saxon Literature (Thrane 1986) and AIDS prevention (Van Vugt 1994), it is virtually impossible to outline any strict or universal method or design for conducting the case study. However, Robert K. Yin (1993) does offer five basic components of a research design:

- A study's questions.

- A study's propositions (if any).

- A study's units of analysis.

- The logic that links the data to the propositions.

- The criteria for interpreting the findings.

In addition to these five basic components, Yin also stresses the importance of clearly articulating one's theoretical perspective, determining the goals of the study, selecting one's subject(s), selecting the appropriate method(s) of collecting data, and providing some considerations to the composition of the final report.

Conducting Case Studies

To obtain as complete a picture of the participant as possible, case study researchers can employ a variety of approaches and methods. These approaches, methods, and related issues are discussed in depth in this section.

Method: Single or Multi-modal?

To obtain as complete a picture of the participant as possible, case study researchers can employ a variety of methods. Some common methods include interviews , protocol analyses, field studies, and participant-observations. Emig (1971) chose to use several methods of data collection. Her sources included conversations with the students, protocol analysis, discrete observations of actual composition, writing samples from each student, and school records (Lauer and Asher 1988).

Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988) collected data by observing classrooms, conducting faculty and student interviews, collecting self reports from the subject, and by looking at the subject's written work.

A study that was criticized for using a single method model was done by Flower and Hayes (1984). In this study that explores the ways in which writers use different forms of knowing to create space, the authors used only protocol analysis to gather data. The study came under heavy fire because of their decision to use only one method.

Participant Selection

Case studies can use one participant, or a small group of participants. However, it is important that the participant pool remain relatively small. The participants can represent a diverse cross section of society, but this isn't necessary.

For example, the Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988) study looked at just one participant, Nate. By contrast, in Janet Emig's (1971) study of the composition process of twelfth graders, eight participants were selected representing a diverse cross section of the community, with volunteers from an all-white upper-middle-class suburban school, an all-black inner-city school, a racially mixed lower-middle-class school, an economically and racially mixed school, and a university school.

Often, a brief "case history" is done on the participants of the study in order to provide researchers with a clearer understanding of their participants, as well as some insight as to how their own personal histories might affect the outcome of the study. For instance, in Emig's study, the investigator had access to the school records of five of the participants, and to standardized test scores for the remaining three. Also made available to the researcher was the information that three of the eight students were selected as NCTE Achievement Award winners. These personal histories can be useful in later stages of the study when data are being analyzed and conclusions drawn.

Data Collection

There are six types of data collected in case studies:

- Archival records.

- Interviews.

- Direct observation.

- Participant observation.

In the field of composition research, these six sources might be:

- A writer's drafts.

- School records of student writers.

- Transcripts of interviews with a writer.

- Transcripts of conversations between writers (and protocols).

- Videotapes and notes from direct field observations.

- Hard copies of a writer's work on computer.

Depending on whether researchers have chosen to use a single or multi-modal approach for the case study, they may choose to collect data from one or any combination of these sources.

Protocols, that is, transcriptions of participants talking aloud about what they are doing as they do it, have been particularly common in composition case studies. For example, in Emig's (1971) study, the students were asked, in four different sessions, to give oral autobiographies of their writing experiences and to compose aloud three themes in the presence of a tape recorder and the investigator.

In some studies, only one method of data collection is conducted. For example, the Flower and Hayes (1981) report on the cognitive process theory of writing depends on protocol analysis alone. However, using multiple sources of evidence to increase the reliability and validity of the data can be advantageous.

Case studies are likely to be much more convincing and accurate if they are based on several different sources of information, following a corroborating mode. This conclusion is echoed among many composition researchers. For example, in her study of predrafting processes of high and low-apprehensive writers, Cynthia Selfe (1985) argues that because "methods of indirect observation provide only an incomplete reflection of the complex set of processes involved in composing, a combination of several such methods should be used to gather data in any one study." Thus, in this study, Selfe collected her data from protocols, observations of students role playing their writing processes, audio taped interviews with the students, and videotaped observations of the students in the process of composing.

It can be said then, that cross checking data from multiple sources can help provide a multidimensional profile of composing activities in a particular setting. Sharan Merriam (1985) suggests "checking, verifying, testing, probing, and confirming collected data as you go, arguing that this process will follow in a funnel-like design resulting in less data gathering in later phases of the study along with a congruent increase in analysis checking, verifying, and confirming."

It is important to note that in case studies, as in any qualitative descriptive research, while researchers begin their studies with one or several questions driving the inquiry (which influence the key factors the researcher will be looking for during data collection), a researcher may find new key factors emerging during data collection. These might be unexpected patterns or linguistic features which become evident only during the course of the research. While not bearing directly on the researcher's guiding questions, these variables may become the basis for new questions asked at the end of the report, thus linking to the possibility of further research.

Data Analysis

As the information is collected, researchers strive to make sense of their data. Generally, researchers interpret their data in one of two ways: holistically or through coding. Holistic analysis does not attempt to break the evidence into parts, but rather to draw conclusions based on the text as a whole. Flower and Hayes (1981), for example, make inferences from entire sections of their students' protocols, rather than searching through the transcripts to look for isolatable characteristics.

However, composition researchers commonly interpret their data by coding, that is by systematically searching data to identify and/or categorize specific observable actions or characteristics. These observable actions then become the key variables in the study. Sharan Merriam (1988) suggests seven analytic frameworks for the organization and presentation of data:

- The role of participants.

- The network analysis of formal and informal exchanges among groups.

- Historical.

- Thematical.

- Ritual and symbolism.

- Critical incidents that challenge or reinforce fundamental beliefs, practices, and values.

There are two purposes of these frameworks: to look for patterns among the data and to look for patterns that give meaning to the case study.

As stated above, while most researchers begin their case studies expecting to look for particular observable characteristics, it is not unusual for key variables to emerge during data collection. Typical variables coded in case studies of writers include pauses writers make in the production of a text, the use of specific linguistic units (such as nouns or verbs), and writing processes (planning, drafting, revising, and editing). In the Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988) study, for example, researchers coded the participant's texts for use of connectives, discourse demonstratives, average sentence length, off-register words, use of the first person pronoun, and the ratio of definite articles to indefinite articles.

Since coding is inherently subjective, more than one coder is usually employed. In the Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988) study, for example, three rhetoricians were employed to code the participant's texts for off-register phrases. The researchers established the agreement among the coders before concluding that the participant used fewer off-register words as the graduate program progressed.

Composing the Case Study Report

In the many forms it can take, "a case study is generically a story; it presents the concrete narrative detail of actual, or at least realistic events, it has a plot, exposition, characters, and sometimes even dialogue" (Boehrer 1990). Generally, case study reports are extensively descriptive, with "the most problematic issue often referred to as being the determination of the right combination of description and analysis" (1990). Typically, authors address each step of the research process, and attempt to give the reader as much context as possible for the decisions made in the research design and for the conclusions drawn.

This contextualization usually includes a detailed explanation of the researchers' theoretical positions, of how those theories drove the inquiry or led to the guiding research questions, of the participants' backgrounds, of the processes of data collection, of the training and limitations of the coders, along with a strong attempt to make connections between the data and the conclusions evident.

Although the Berkenkotter, Huckin, and Ackerman (1988) study does not, case study reports often include the reactions of the participants to the study or to the researchers' conclusions. Because case studies tend to be exploratory, most end with implications for further study. Here researchers may identify significant variables that emerged during the research and suggest studies related to these, or the authors may suggest further general questions that their case study generated.

For example, Emig's (1971) study concludes with a section dedicated solely to the topic of implications for further research, in which she suggests several means by which this particular study could have been improved, as well as questions and ideas raised by this study which other researchers might like to address, such as: is there a correlation between a certain personality and a certain composing process profile (e.g. is there a positive correlation between ego strength and persistence in revising)?

Also included in Emig's study is a section dedicated to implications for teaching, which outlines the pedagogical ramifications of the study's findings for teachers currently involved in high school writing programs.

Sharan Merriam (1985) also offers several suggestions for alternative presentations of data:

- Prepare specialized condensations for appropriate groups.

- Replace narrative sections with a series of answers to open-ended questions.

- Present "skimmer's" summaries at beginning of each section.

- Incorporate headlines that encapsulate information from text.

- Prepare analytic summaries with supporting data appendixes.

- Present data in colorful and/or unique graphic representations.

Issues of Validity and Reliability

Once key variables have been identified, they can be analyzed. Reliability becomes a key concern at this stage, and many case study researchers go to great lengths to ensure that their interpretations of the data will be both reliable and valid. Because issues of validity and reliability are an important part of any study in the social sciences, it is important to identify some ways of dealing with results.

Multi-modal case study researchers often balance the results of their coding with data from interviews or writer's reflections upon their own work. Consequently, the researchers' conclusions become highly contextualized. For example, in a case study which looked at the time spent in different stages of the writing process, Berkenkotter concluded that her participant, Donald Murray, spent more time planning his essays than in other writing stages. The report of this case study is followed by Murray's reply, wherein he agrees with some of Berkenkotter's conclusions and disagrees with others.

As is the case with other research methodologies, issues of external validity, construct validity, and reliability need to be carefully considered.

Commentary on Case Studies

Researchers often debate the relative merits of particular methods, among them case study. In this section, we comment on two key issues. To read the commentaries, choose any of the items below:

Strengths and Weaknesses of Case Studies

Most case study advocates point out that case studies produce much more detailed information than what is available through a statistical analysis. Advocates will also hold that while statistical methods might be able to deal with situations where behavior is homogeneous and routine, case studies are needed to deal with creativity, innovation, and context. Detractors argue that case studies are difficult to generalize because of inherent subjectivity and because they are based on qualitative subjective data, generalizable only to a particular context.

Flexibility

The case study approach is a comparatively flexible method of scientific research. Because its project designs seem to emphasize exploration rather than prescription or prediction, researchers are comparatively freer to discover and address issues as they arise in their experiments. In addition, the looser format of case studies allows researchers to begin with broad questions and narrow their focus as their experiment progresses rather than attempt to predict every possible outcome before the experiment is conducted.

Emphasis on Context

By seeking to understand as much as possible about a single subject or small group of subjects, case studies specialize in "deep data," or "thick description"--information based on particular contexts that can give research results a more human face. This emphasis can help bridge the gap between abstract research and concrete practice by allowing researchers to compare their firsthand observations with the quantitative results obtained through other methods of research.

Inherent Subjectivity

"The case study has long been stereotyped as the weak sibling among social science methods," and is often criticized as being too subjective and even pseudo-scientific. Likewise, "investigators who do case studies are often regarded as having deviated from their academic disciplines, and their investigations as having insufficient precision (that is, quantification), objectivity and rigor" (Yin 1989). Opponents cite opportunities for subjectivity in the implementation, presentation, and evaluation of case study research. The approach relies on personal interpretation of data and inferences. Results may not be generalizable, are difficult to test for validity, and rarely offer a problem-solving prescription. Simply put, relying on one or a few subjects as a basis for cognitive extrapolations runs the risk of inferring too much from what might be circumstance.

High Investment

Case studies can involve learning more about the subjects being tested than most researchers would care to know--their educational background, emotional background, perceptions of themselves and their surroundings, their likes, dislikes, and so on. Because of its emphasis on "deep data," the case study is out of reach for many large-scale research projects which look at a subject pool in the tens of thousands. A budget request of $10,000 to examine 200 subjects sounds more efficient than a similar request to examine four subjects.

Ethical Considerations

Researchers conducting case studies should consider certain ethical issues. For example, many educational case studies are often financed by people who have, either directly or indirectly, power over both those being studied and those conducting the investigation (1985). This conflict of interests can hinder the credibility of the study.

The personal integrity, sensitivity, and possible prejudices and/or biases of the investigators need to be taken into consideration as well. Personal biases can creep into how the research is conducted, alternative research methods used, and the preparation of surveys and questionnaires.

A common complaint in case study research is that investigators change direction during the course of the study unaware that their original research design was inadequate for the revised investigation. Thus, the researchers leave unknown gaps and biases in the study. To avoid this, researchers should report preliminary findings so that the likelihood of bias will be reduced.

Concerns about Reliability, Validity, and Generalizability

Merriam (1985) offers several suggestions for how case study researchers might actively combat the popular attacks on the validity, reliability, and generalizability of case studies:

- Prolong the Processes of Data Gathering on Site: This will help to insure the accuracy of the findings by providing the researcher with more concrete information upon which to formulate interpretations.

- Employ the Process of "Triangulation": Use a variety of data sources as opposed to relying solely upon one avenue of observation. One example of such a data check would be what McClintock, Brannon, and Maynard (1985) refer to as a "case cluster method," that is, when a single unit within a larger case is randomly sampled, and that data treated quantitatively." For instance, in Emig's (1971) study, the case cluster method was employed, singling out the productivity of a single student named Lynn. This cluster profile included an advanced case history of the subject, specific examination and analysis of individual compositions and protocols, and extensive interview sessions. The seven remaining students were then compared with the case of Lynn, to ascertain if there are any shared, or unique dimensions to the composing process engaged in by these eight students.

- Conduct Member Checks: Initiate and maintain an active corroboration on the interpretation of data between the researcher and those who provided the data. In other words, talk to your subjects.

- Collect Referential Materials: Complement the file of materials from the actual site with additional document support. For example, Emig (1971) supports her initial propositions with historical accounts by writers such as T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, and D.H. Lawrence. Emig also cites examples of theoretical research done with regards to the creative process, as well as examples of empirical research dealing with the writing of adolescents. Specific attention is then given to the four stages description of the composing process delineated by Helmoltz, Wallas, and Cowley, as it serves as the focal point in this study.

- Engage in Peer Consultation: Prior to composing the final draft of the report, researchers should consult with colleagues in order to establish validity through pooled judgment.

Although little can be done to combat challenges concerning the generalizability of case studies, "most writers suggest that qualitative research should be judged as credible and confirmable as opposed to valid and reliable" (Merriam 1985). Likewise, it has been argued that "rather than transplanting statistical, quantitative notions of generalizability and thus finding qualitative research inadequate, it makes more sense to develop an understanding of generalization that is congruent with the basic characteristics of qualitative inquiry" (1985). After all, criticizing the case study method for being ungeneralizable is comparable to criticizing a washing machine for not being able to tell the correct time. In other words, it is unjust to criticize a method for not being able to do something which it was never originally designed to do in the first place.

Annotated Bibliography

Armisted, C. (1984). How Useful are Case Studies. Training and Development Journal, 38 (2), 75-77.

This article looks at eight types of case studies, offers pros and cons of using case studies in the classroom, and gives suggestions for successfully writing and using case studies.

Bardovi-Harlig, K. (1997). Beyond Methods: Components of Second Language Teacher Education . New York: McGraw-Hill.

A compilation of various research essays which address issues of language teacher education. Essays included are: "Non-native reading research and theory" by Lee, "The case for Psycholinguistics" by VanPatten, and "Assessment and Second Language Teaching" by Gradman and Reed.

Bartlett, L. (1989). A Question of Good Judgment; Interpretation Theory and Qualitative Enquiry Address. 70th Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. San Francisco.

Bartlett selected "quasi-historical" methodology, which focuses on the "truth" found in case records, as one that will provide "good judgments" in educational inquiry. He argues that although the method is not comprehensive, it can try to connect theory with practice.

Baydere, S. et. al. (1993). Multimedia conferencing as a tool for collaborative writing: a case study in Computer Supported Collaborative Writing. New York: Springer-Verlag.

The case study by Baydere et. al. is just one of the many essays in this book found in the series "Computer Supported Cooperative Work." Denley, Witefield and May explore similar issues in their essay, "A case study in task analysis for the design of a collaborative document production system."

Berkenkotter, C., Huckin, T., N., & Ackerman J. (1988). Conventions, Conversations, and the Writer: Case Study of a Student in a Rhetoric Ph.D. Program. Research in the Teaching of English, 22, 9-44.

The authors focused on how the writing of their subject, Nate or Ackerman, changed as he became more acquainted or familiar with his field's discourse community.

Berninger, V., W., and Gans, B., M. (1986). Language Profiles in Nonspeaking Individuals of Normal Intelligence with Severe Cerebral Palsy. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 2, 45-50.

Argues that generalizations about language abilities in patients with severe cerebral palsy (CP) should be avoided. Standardized tests of different levels of processing oral language, of processing written language, and of producing written language were administered to 3 male participants (aged 9, 16, and 40 yrs).

Bockman, J., R., and Couture, B. (1984). The Case Method in Technical Communication: Theory and Models. Texas: Association of Teachers of Technical Writing.

Examines the study and teaching of technical writing, communication of technical information, and the case method in terms of those applications.

Boehrer, J. (1990). Teaching With Cases: Learning to Question. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 42 41-57.

This article discusses the origins of the case method, looks at the question of what is a case, gives ideas about learning in case teaching, the purposes it can serve in the classroom, the ground rules for the case discussion, including the role of the question, and new directions for case teaching.

Bowman, W. R. (1993). Evaluating JTPA Programs for Economically Disadvantaged Adults: A Case Study of Utah and General Findings . Washington: National Commission for Employment Policy.

"To encourage state-level evaluations of JTPA, the Commission and the State of Utah co-sponsored this report on the effectiveness of JTPA Title II programs for adults in Utah. The technique used is non-experimental and the comparison group was selected from registrants with Utah's Employment Security. In a step-by-step approach, the report documents how non-experimental techniques can be applied and several specific technical issues can be addressed."

Boyce, A. (1993) The Case Study Approach for Pedagogists. Annual Meeting of the American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance. (Address). Washington DC.

This paper addresses how case studies 1) bridge the gap between teaching theory and application, 2) enable students to analyze problems and develop solutions for situations that will be encountered in the real world of teaching, and 3) helps students to evaluate the feasibility of alternatives and to understand the ramifications of a particular course of action.

Carson, J. (1993) The Case Study: Ideal Home of WAC Quantitative and Qualitative Data. Annual Meeting of the Conference on College Composition and Communication. (Address). San Diego.

"Increasingly, one of the most pressing questions for WAC advocates is how to keep [WAC] programs going in the face of numerous difficulties. Case histories offer the best chance for fashioning rhetorical arguments to keep WAC programs going because they offer the opportunity to provide a coherent narrative that contextualizes all documents and data, including what is generally considered scientific data. A case study of the WAC program, . . . at Robert Morris College in Pittsburgh demonstrates the advantages of this research method. Such studies are ideal homes for both naturalistic and positivistic data as well as both quantitative and qualitative information."

---. (1991). A Cognitive Process Theory of Writing. College Composition and Communication. 32. 365-87.

No abstract available.

Cromer, R. (1994) A Case Study of Dissociations Between Language and Cognition. Constraints on Language Acquisition: Studies of Atypical Children . Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 141-153.

Crossley, M. (1983) Case Study in Comparative and International Education: An Approach to Bridging the Theory-Practice Gap. Proceedings of the 11th Annual Conference of the Australian Comparative and International Education Society. Hamilton, NZ.

Case study research, as presented here, helps bridge the theory-practice gap in comparative and international research studies of education because it focuses on the practical, day-to-day context rather than on the national arena. The paper asserts that the case study method can be valuable at all levels of research, formation, and verification of theories in education.

Daillak, R., H., and Alkin, M., C. (1982). Qualitative Studies in Context: Reflections on the CSE Studies of Evaluation Use . California: EDRS

The report shows how the Center of the Study of Evaluation (CSE) applied qualitative techniques to a study of evaluation information use in local, Los Angeles schools. It critiques the effectiveness and the limitations of using case study, evaluation, field study, and user interview survey methodologies.

Davey, L. (1991). The Application of Case Study Evaluations. ERIC/TM Digest.

This article examines six types of case studies, the type of evaluation questions that can be answered, the functions served, some design features, and some pitfalls of the method.

Deutch, C. E. (1996). A course in research ethics for graduate students. College Teaching, 44, 2, 56-60.

This article describes a one-credit discussion course in research ethics for graduate students in biology. Case studies are focused on within the four parts of the course: 1) major issues, 2 )practical issues in scholarly work, 3) ownership of research results, and 4) training and personal decisions.

DeVoss, G. (1981). Ethics in Fieldwork Research. RIE 27p. (ERIC)

This article examines four of the ethical problems that can happen when conducting case study research: acquiring permission to do research, knowing when to stop digging, the pitfalls of doing collaborative research, and preserving the integrity of the participants.

Driscoll, A. (1985). Case Study of a Research Intervention: the University of Utah’s Collaborative Approach . San Francisco: Far West Library for Educational Research Development.

Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education, Denver, CO, March 1985. Offers information of in-service training, specifically case studies application.

Ellram, L. M. (1996). The Use of the Case Study Method in Logistics Research. Journal of Business Logistics, 17, 2, 93.

This article discusses the increased use of case study in business research, and the lack of understanding of when and how to use case study methodology in business.

Emig, J. (1971) The Composing Processes of Twelfth Graders . Urbana: NTCE.

This case study uses observation, tape recordings, writing samples, and school records to show that writing in reflexive and extensive situations caused different lengths of discourse and different clusterings of the components of the writing process.

Feagin, J. R. (1991). A Case For the Case Study . Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

This book discusses the nature, characteristics, and basic methodological issues of the case study as a research method.

Feldman, H., Holland, A., & Keefe, K. (1989) Language Abilities after Left Hemisphere Brain Injury: A Case Study of Twins. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 9, 32-47.

"Describes the language abilities of 2 twin pairs in which 1 twin (the experimental) suffered brain injury to the left cerebral hemisphere around the time of birth and1 twin (the control) did not. One pair of twins was initially assessed at age 23 mo. and the other at about 30 mo.; they were subsequently evaluated in their homes 3 times at about 6-mo intervals."

Fidel, R. (1984). The Case Study Method: A Case Study. Library and Information Science Research, 6.

The article describes the use of case study methodology to systematically develop a model of online searching behavior in which study design is flexible, subject manner determines data gathering and analyses, and procedures adapt to the study's progressive change.

Flower, L., & Hayes, J. R. (1984). Images, Plans and Prose: The Representation of Meaning in Writing. Written Communication, 1, 120-160.

Explores the ways in which writers actually use different forms of knowing to create prose.

Frey, L. R. (1992). Interpreting Communication Research: A Case Study Approach Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

The book discusses research methodologies in the Communication field. It focuses on how case studies bridge the gap between communication research, theory, and practice.

Gilbert, V. K. (1981). The Case Study as a Research Methodology: Difficulties and Advantages of Integrating the Positivistic, Phenomenological and Grounded Theory Approaches . The Annual Meeting of the Canadian Association for the Study of Educational Administration. (Address) Halifax, NS, Can.

This study on an innovative secondary school in England shows how a "low-profile" participant-observer case study was crucial to the initial observation, the testing of hypotheses, the interpretive approach, and the grounded theory.

Gilgun, J. F. (1994). A Case for Case Studies in Social Work Research. Social Work, 39, 4, 371-381.

This article defines case study research, presents guidelines for evaluation of case studies, and shows the relevance of case studies to social work research. It also looks at issues such as evaluation and interpretations of case studies.

Glennan, S. L., Sharp-Bittner, M. A. & Tullos, D. C. (1991). Augmentative and Alternative Communication Training with a Nonspeaking Adult: Lessons from MH. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 7, 240-7.

"A response-guided case study documented changes in a nonspeaking 36-yr-old man's ability to communicate using 3 trained augmentative communication modes. . . . Data were collected in videotaped interaction sessions between the nonspeaking adult and a series of adult speaking."

Graves, D. (1981). An Examination of the Writing Processes of Seven Year Old Children. Research in the Teaching of English, 15, 113-134.

Hamel, J. (1993). Case Study Methods . Newbury Park: Sage. .

"In a most economical fashion, Hamel provides a practical guide for producing theoretically sharp and empirically sound sociological case studies. A central idea put forth by Hamel is that case studies must "locate the global in the local" thus making the careful selection of the research site the most critical decision in the analytic process."

Karthigesu, R. (1986, July). Television as a Tool for Nation-Building in the Third World: A Post-Colonial Pattern, Using Malaysia as a Case-Study. International Television Studies Conference. (Address). London, 10-12.

"The extent to which Television Malaysia, as a national mass media organization, has been able to play a role in nation building in the post-colonial period is . . . studied in two parts: how the choice of a model of nation building determines the character of the organization; and how the character of the organization influences the output of the organization."

Kenny, R. (1984). Making the Case for the Case Study. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 16, (1), 37-51.

The article looks at how and why the case study is justified as a viable and valuable approach to educational research and program evaluation.

Knirk, F. (1991). Case Materials: Research and Practice. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 4 (1 ), 73-81.

The article addresses the effectiveness of case studies, subject areas where case studies are commonly used, recent examples of their use, and case study design considerations.

Klos, D. (1976). Students as Case Writers. Teaching of Psychology, 3.2, 63-66.

This article reviews a course in which students gather data for an original case study of another person. The task requires the students to design the study, collect the data, write the narrative, and interpret the findings.

Leftwich, A. (1981). The Politics of Case Study: Problems of Innovation in University Education. Higher Education Review, 13.2, 38-64.

The article discusses the use of case studies as a teaching method. Emphasis is on the instructional materials, interdisciplinarity, and the complex relationships within the university that help or hinder the method.

Mabrito, M. (1991, Oct.). Electronic Mail as a Vehicle for Peer Response: Conversations of High and Low Apprehensive Writers. Written Communication, 509-32.

McCarthy, S., J. (1955). The Influence of Classroom Discourse on Student Texts: The Case of Ella . East Lansing: Institute for Research on Teaching.

A look at how students of color become marginalized within traditional classroom discourse. The essay follows the struggles of one black student: Ella.

Matsuhashi, A., ed. (1987). Writing in Real Time: Modeling Production Processes Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation.

Investigates how writers plan to produce discourse for different purposes to report, to generalize, and to persuade, as well as how writers plan for sentence level units of language. To learn about planning, an observational measure of pause time was used" (ERIC).

Merriam, S. B. (1985). The Case Study in Educational Research: A Review of Selected Literature. Journal of Educational Thought, 19.3, 204-17.

The article examines the characteristics of, philosophical assumptions underlying the case study, the mechanics of conducting a case study, and the concerns about the reliability, validity, and generalizability of the method.

---. (1988). Case Study Research in Education: A Qualitative Approach San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Merry, S. E., & Milner, N. eds. (1993). The Possibility of Popular Justice: A Case Study of Community Mediation in the United States . Ann Arbor: U of Michigan.

". . . this volume presents a case study of one experiment in popular justice, the San Francisco Community Boards. This program has made an explicit claim to create an alternative justice, or new justice, in the midst of a society ordered by state law. The contributors to this volume explore the history and experience of the program and compare it to other versions of popular justice in the United States, Europe, and the Third World."

Merseth, K. K. (1991). The Case for Cases in Teacher Education. RIE. 42p. (ERIC).

This monograph argues that the case method of instruction offers unique potential for revitalizing the field of teacher education.

Michaels, S. (1987). Text and Context: A New Approach to the Study of Classroom Writing. Discourse Processes, 10, 321-346.

"This paper argues for and illustrates an approach to the study of writing that integrates ethnographic analysis of classroom interaction with linguistic analysis of written texts and teacher/student conversational exchanges. The approach is illustrated through a case study of writing in a single sixth grade classroom during a single writing assignment."

Milburn, G. (1995). Deciphering a Code or Unraveling a Riddle: A Case Study in the Application of a Humanistic Metaphor to the Reporting of Social Studies Teaching. Theory and Research in Education, 13.

This citation serves as an example of how case studies document learning procedures in a senior-level economics course.

Milley, J. E. (1979). An Investigation of Case Study as an Approach to Program Evaluation. 19th Annual Forum of the Association for Institutional Research. (Address). San Diego.

The case study method merged a narrative report focusing on the evaluator as participant-observer with document review, interview, content analysis, attitude questionnaire survey, and sociogram analysis. Milley argues that case study program evaluation has great potential for widespread use.

Minnis, J. R. (1985, Sept.). Ethnography, Case Study, Grounded Theory, and Distance Education Research. Distance Education, 6.2.

This article describes and defines the strengths and weaknesses of ethnography, case study, and grounded theory.

Nunan, D. (1992). Collaborative language learning and teaching . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Included in this series of essays is Peter Sturman’s "Team Teaching: a case study from Japan" and David Nunan’s own "Toward a collaborative approach to curriculum development: a case study."

Nystrand, M., ed. (1982). What Writers Know: The Language, Process, and Structure of Written Discourse . New York: Academic Press.

Owenby, P. H. (1992). Making Case Studies Come Alive. Training, 29, (1), 43-46. (ERIC)

This article provides tips for writing more effective case studies.

---. (1981). Pausing and Planning: The Tempo of Writer Discourse Production. Research in the Teaching of English, 15 (2),113-34.

Perl, S. (1979). The Composing Processes of Unskilled College Writers. Research in the Teaching of English, 13, 317-336.

"Summarizes a study of five unskilled college writers, focusing especially on one of the five, and discusses the findings in light of current pedagogical practice and research design."

Pilcher J. and A. Coffey. eds. (1996). Gender and Qualitative Research . Brookfield: Aldershot, Hants, England.

This book provides a series of essays which look at gender identity research, qualitative research and applications of case study to questions of gendered pedagogy.

Pirie, B. S. (1993). The Case of Morty: A Four Year Study. Gifted Education International, 9 (2), 105-109.

This case study describes a boy from kindergarten through third grade with above average intelligence but difficulty in learning to read, write, and spell.

Popkewitz, T. (1993). Changing Patterns of Power: Social Regulation and Teacher Education Reform. Albany: SUNY Press.

Popkewitz edits this series of essays that address case studies on educational change and the training of teachers. The essays vary in terms of discipline and scope. Also, several authors include case studies of educational practices in countries other than the United States.

---. (1984). The Predrafting Processes of Four High- and Four Low Apprehensive Writers. Research in the Teaching of English, 18, (1), 45-64.

Rasmussen, P. (1985, March) A Case Study on the Evaluation of Research at the Technical University of Denmark. International Journal of Institutional Management in Higher Education, 9 (1).

This is an example of a case study methodology used to evaluate the chemistry and chemical engineering departments at the University of Denmark.

Roth, K. J. (1986). Curriculum Materials, Teacher Talk, and Student Learning: Case Studies in Fifth-Grade Science Teaching . East Lansing: Institute for Research on Teaching.

Roth offers case studies on elementary teachers, elementary school teaching, science studies and teaching, and verbal learning.

Selfe, C. L. (1985). An Apprehensive Writer Composes. When a Writer Can't Write: Studies in Writer's Block and Other Composing-Process Problems . (pp. 83-95). Ed. Mike Rose. NMY: Guilford.

Smith-Lewis, M., R. and Ford, A. (1987). A User's Perspective on Augmentative Communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 3, 12-7.

"During a series of in-depth interviews, a 25-yr-old woman with cerebral palsy who utilized augmentative communication reflected on the effectiveness of the devices designed for her during her school career."

St. Pierre, R., G. (1980, April). Follow Through: A Case Study in Metaevaluation Research . 64th Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. (Address).

The three approaches to metaevaluation are evaluation of primary evaluations, integrative meta-analysis with combined primary evaluation results, and re-analysis of the raw data from a primary evaluation.

Stahler, T., M. (1996, Feb.) Early Field Experiences: A Model That Worked. ERIC.

"This case study of a field and theory class examines a model designed to provide meaningful field experiences for preservice teachers while remaining consistent with the instructor's beliefs about the role of teacher education in preparing teachers for the classroom."

Stake, R. E. (1995). The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

This book examines case study research in education and case study methodology.

Stiegelbauer, S. (1984) Community, Context, and Co-curriculum: Situational Factors Influencing School Improvements in a Study of High Schools. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA.

Discussion of several case studies: one looking at high school environments, another examining educational innovations.

Stolovitch, H. (1990). Case Study Method. Performance And Instruction, 29, (9), 35-37.

This article describes the case study method as a form of simulation and presents guidelines for their use in professional training situations.

Thaller, E. (1994). Bibliography for the Case Method: Using Case Studies in Teacher Education. RIE. 37 p.

This bibliography presents approximately 450 citations on the use of case studies in teacher education from 1921-1993.

Thrane, T. (1986). On Delimiting the Senses of Near-Synonyms in Historical Semantics: A Case Study of Adjectives of 'Moral Sufficiency' in the Old English Andreas. Linguistics Across Historical and Geographical Boundaries: In Honor of Jacek Fisiak on the Occasion of his Fiftieth Birthday . Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

United Nations. (1975). Food and Agriculture Organization. Report on the FAO/UNFPA Seminar on Methodology, Research and Country: Case Studies on Population, Employment and Productivity . Rome: United Nations.

This example case study shows how the methodology can be used in a demographic and psychographic evaluation. At the same time, it discusses the formation and instigation of the case study methodology itself.

Van Vugt, J. P., ed. (1994). Aids Prevention and Services: Community Based Research . Westport: Bergin and Garvey.

"This volume has been five years in the making. In the process, some of the policy applications called for have met with limited success, such as free needle exchange programs in a limited number of American cities, providing condoms to prison inmates, and advertisements that depict same-sex couples. Rather than dating our chapters that deal with such subjects, such policy applications are verifications of the type of research demonstrated here. Furthermore, they indicate the critical need to continue community based research in the various communities threatened by acquired immuno-deficiency syndrome (AIDS) . . . "

Welch, W., ed. (1981, May). Case Study Methodology in Educational Evaluation. Proceedings of the Minnesota Evaluation Conference. Minnesota. (Address).

The four papers in these proceedings provide a comprehensive picture of the rationale, methodology, strengths, and limitations of case studies.

Williams, G. (1987). The Case Method: An Approach to Teaching and Learning in Educational Administration. RIE, 31p.

This paper examines the viability of the case method as a teaching and learning strategy in instructional systems geared toward the training of personnel of the administration of various aspects of educational systems.

Yin, R. K. (1993). Advancing Rigorous Methodologies: A Review of 'Towards Rigor in Reviews of Multivocal Literatures.' Review of Educational Research, 61, (3).

"R. T. Ogawa and B. Malen's article does not meet its own recommended standards for rigorous testing and presentation of its own conclusions. Use of the exploratory case study to analyze multivocal literatures is not supported, and the claim of grounded theory to analyze multivocal literatures may be stronger."

---. (1989). Case Study Research: Design and Methods. London: Sage Publications Inc.

This book discusses in great detail, the entire design process of the case study, including entire chapters on collecting evidence, analyzing evidence, composing the case study report, and designing single and multiple case studies.

Related Links

Consider the following list of related Web sites for more information on the topic of case study research. Note: although many of the links cover the general category of qualitative research, all have sections that address issues of case studies.

- Sage Publications on Qualitative Methodology: Search here for a comprehensive list of new books being published about "Qualitative Methodology" http://www.sagepub.co.uk/

- The International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education: An on-line journal "to enhance the theory and practice of qualitative research in education." On-line submissions are welcome. http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/tf/09518398.html

- Qualitative Research Resources on the Internet: From syllabi to home pages to bibliographies. All links relate somehow to qualitative research. http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/qualres.html

Becker, Bronwyn, Patrick Dawson, Karen Devine, Carla Hannum, Steve Hill, Jon Leydens, Debbie Matuskevich, Carol Traver, & Mike Palmquist. (2005). Case Studies. Writing@CSU . Colorado State University. https://writing.colostate.edu/guides/guide.cfm?guideid=60

Observation Method in Psychology: Naturalistic, Participant and Controlled

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

The observation method in psychology involves directly and systematically witnessing and recording measurable behaviors, actions, and responses in natural or contrived settings without attempting to intervene or manipulate what is being observed.

Used to describe phenomena, generate hypotheses, or validate self-reports, psychological observation can be either controlled or naturalistic with varying degrees of structure imposed by the researcher.

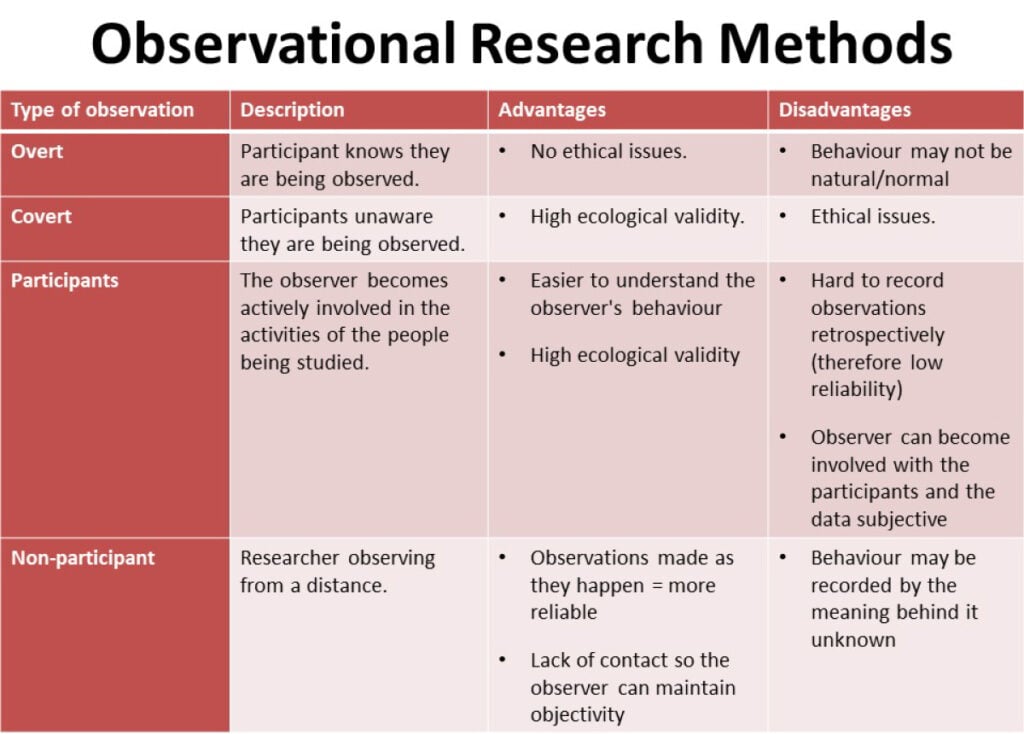

There are different types of observational methods, and distinctions need to be made between:

1. Controlled Observations 2. Naturalistic Observations 3. Participant Observations

In addition to the above categories, observations can also be either overt/disclosed (the participants know they are being studied) or covert/undisclosed (the researcher keeps their real identity a secret from the research subjects, acting as a genuine member of the group).

In general, conducting observational research is relatively inexpensive, but it remains highly time-consuming and resource-intensive in data processing and analysis.

The considerable investments needed in terms of coder time commitments for training, maintaining reliability, preventing drift, and coding complex dynamic interactions place practical barriers on observers with limited resources.

Controlled Observation

Controlled observation is a research method for studying behavior in a carefully controlled and structured environment.

The researcher sets specific conditions, variables, and procedures to systematically observe and measure behavior, allowing for greater control and comparison of different conditions or groups.

The researcher decides where the observation will occur, at what time, with which participants, and in what circumstances, and uses a standardized procedure. Participants are randomly allocated to each independent variable group.

Rather than writing a detailed description of all behavior observed, it is often easier to code behavior according to a previously agreed scale using a behavior schedule (i.e., conducting a structured observation).

The researcher systematically classifies the behavior they observe into distinct categories. Coding might involve numbers or letters to describe a characteristic or the use of a scale to measure behavior intensity.

The categories on the schedule are coded so that the data collected can be easily counted and turned into statistics.

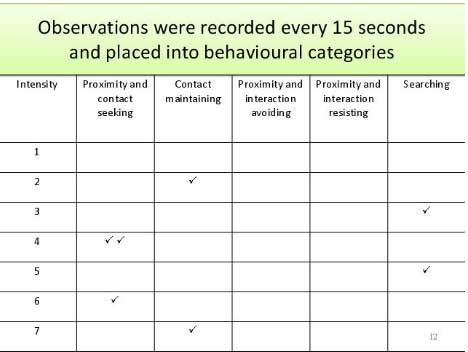

For example, Mary Ainsworth used a behavior schedule to study how infants responded to brief periods of separation from their mothers. During the Strange Situation procedure, the infant’s interaction behaviors directed toward the mother were measured, e.g.,

- Proximity and contact-seeking

- Contact maintaining

- Avoidance of proximity and contact

- Resistance to contact and comforting

The observer noted down the behavior displayed during 15-second intervals and scored the behavior for intensity on a scale of 1 to 7.

Sometimes participants’ behavior is observed through a two-way mirror, or they are secretly filmed. Albert Bandura used this method to study aggression in children (the Bobo doll studies ).

A lot of research has been carried out in sleep laboratories as well. Here, electrodes are attached to the scalp of participants. What is observed are the changes in electrical activity in the brain during sleep ( the machine is called an EEG ).

Controlled observations are usually overt as the researcher explains the research aim to the group so the participants know they are being observed.

Controlled observations are also usually non-participant as the researcher avoids direct contact with the group and keeps a distance (e.g., observing behind a two-way mirror).

- Controlled observations can be easily replicated by other researchers by using the same observation schedule. This means it is easy to test for reliability .

- The data obtained from structured observations is easier and quicker to analyze as it is quantitative (i.e., numerical) – making this a less time-consuming method compared to naturalistic observations.

- Controlled observations are fairly quick to conduct which means that many observations can take place within a short amount of time. This means a large sample can be obtained, resulting in the findings being representative and having the ability to be generalized to a large population.

Limitations

- Controlled observations can lack validity due to the Hawthorne effect /demand characteristics. When participants know they are being watched, they may act differently.

Naturalistic Observation

Naturalistic observation is a research method in which the researcher studies behavior in its natural setting without intervention or manipulation.

It involves observing and recording behavior as it naturally occurs, providing insights into real-life behaviors and interactions in their natural context.

Naturalistic observation is a research method commonly used by psychologists and other social scientists.

This technique involves observing and studying the spontaneous behavior of participants in natural surroundings. The researcher simply records what they see in whatever way they can.

In unstructured observations, the researcher records all relevant behavior with a coding system. There may be too much to record, and the behaviors recorded may not necessarily be the most important, so the approach is usually used as a pilot study to see what type of behaviors would be recorded.

Compared with controlled observations, it is like the difference between studying wild animals in a zoo and studying them in their natural habitat.

With regard to human subjects, Margaret Mead used this method to research the way of life of different tribes living on islands in the South Pacific. Kathy Sylva used it to study children at play by observing their behavior in a playgroup in Oxfordshire.

Collecting Naturalistic Behavioral Data

Technological advances are enabling new, unobtrusive ways of collecting naturalistic behavioral data.

The Electronically Activated Recorder (EAR) is a digital recording device participants can wear to periodically sample ambient sounds, allowing representative sampling of daily experiences (Mehl et al., 2012).

Studies program EARs to record 30-50 second sound snippets multiple times per hour. Although coding the recordings requires extensive resources, EARs can capture spontaneous behaviors like arguments or laughter.

EARs minimize participant reactivity since sampling occurs outside of awareness. This reduces the Hawthorne effect, where people change behavior when observed.