This website may not work correctly because your browser is out of date. Please update your browser .

Qualitative comparative analysis

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) is a means of analysing the causal contribution of different conditions (e.g. aspects of an intervention and the wider context) to an outcome of interest.

QCA starts with the documentation of the different configurations of conditions associated with each case of an observed outcome. These are then subject to a minimisation procedure that identifies the simplest set of conditions that can account for all the observed outcomes, as well as their absence.

The results are typically expressed in statements expressed in ordinary language or as Boolean algebra. For example:

- A combination of Condition A and condition B or a combination of condition C and condition D will lead to outcome E.

- In Boolean notation this is expressed more succinctly as A*B + C*D→E

QCA results are able to distinguish various complex forms of causation, including:

- Configurations of causal conditions, not just single causes. In the example above, there are two different causal configurations, each made up of two conditions.

- Equifinality, where there is more than one way in which an outcome can happen. In the above example, each additional configuration represents a different causal pathway

- Causal conditions which are necessary, sufficient, both or neither, plus more complex combinations (known as INUS causes – insufficient but necessary parts of a configuration that is unnecessary but sufficient), which tend to be more common in everyday life. In the example above, no one condition was sufficient or necessary. But each condition is an INUS type cause

- Asymmetric causes – where the causes of failure may not simply be the absence of the cause of success. In the example above, the configuration associated with the absence of E might have been one like this: A*B*X + C*D*X →e Here X condition was a sufficient and necessary blocking condition.

- The relative influence of different individual conditions and causal configurations in a set of cases being examined. In the example above, the first configuration may have been associated with 10 cases where the outcome was E, whereas the second might have been associated with only 5 cases. Configurations can be evaluated in terms of coverage (the percentage of cases they explain) and consistency (the extent to which a configuration is always associated with a given outcome).

QCA is able to use relatively small and simple data sets. There is no requirement to have enough cases to achieve statistical significance, although ideally there should be enough cases to potentially exhibit all the possible configurations. The latter depends on the number of conditions present. In a 2012 survey of QCA uses the median number of cases was 22 and the median number of conditions was 6. For each case, the presence or absence of a condition is recorded using nominal data i.e. a 1 or 0. More sophisticated forms of QCA allow the use of “fuzzy sets” i.e. where a condition may be partly present or partly absent, represented by a value of 0.8 or 0.2 for example. Or there may be more than one kind of presence, represented by values of 0, 1, 2 or more for example. Data for a QCA analysis is collated in a simple matrix form, where rows = cases and columns = conditions, with the rightmost column listing the associated outcome for each case, also described in binary form.

QCA is a theory-driven approach, in that the choice of conditions being examined needs to be driven by a prior theory about what matters. The list of conditions may also be revised in the light of the results of the QCA analysis if some configurations are still shown as being associated with a mixture of outcomes. The coding of the presence/absence of a condition also requires an explicit view of that condition and when and where it can be considered present. Dichotomisation of quantitative measures about the incidence of a condition also needs to be carried out with an explicit rationale, and not on an arbitrary basis.

Although QCA was originally developed by Charles Ragin some decades ago it is only in the last decade that its use has become more common amongst evaluators. Articles on its use have appeared in Evaluation and the American Journal of Evaluation.

For a worked example, see Charles Ragin’s What is Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA)? , slides 6 to 15 on The bare-bones basics of crisp-set QCA.

[A crude summary of the example is presented here]

In his presentation Ragin provides data on 65 countries and their reactions to austerity measures imposed by the IMF. This has been condensed into a Truth Table (shown below), which shows all possible configurations of four different conditions that were thought to affect countries’ responses: the presence or absence of severe austerity, prior mobilisation, corrupt government, rapid price rises. Next to each configuration is data on the outcome associated with that configuration – the numbers of countries experiencing mass protest or not. There are 16 configurations in all, one per row. The rightmost column describes the consistency of each configuration: whether all cases with that configuration have one type of outcome, or a mixed outcome (i.e. some protests and some no protests). Notice that there are also some configurations with no known cases.

Ragin’s next step is to improve the consistency of the configurations with mixed consistency. This is done either by rejecting cases within an inconsistent configuration because they are outliers (with exceptional circumstances unlikely to be repeated elsewhere) or by introducing an additional condition (column) that distinguishes between those configurations which did lead to protest and those which did not. In this example, a new condition was introduced that removed the inconsistency, which was described as “not having a repressive regime”.

The next step involves reducing the number of configurations needed to explain all the outcomes, known as minimisation. Because this is a time-consuming process, this is done by an automated algorithm (aka a computer program) This algorithm takes two configurations at a time and examines if they have the same outcome. If so, and if their configurations are only different in respect to one condition this is deemed to not be an important causal factor and the two configurations are collapsed into one. This process of comparisons is continued, looking at all configurations, including newly collapsed ones, until no further reductions are possible.

[Jumping a few more specific steps] The final result from the minimisation of the above truth table is this configuration:

SA*(PR + PM*GC*NR)

The expression indicates that IMF protest erupts when severe austerity (SA) is combined with either (1) rapid price increases (PR) or (2) the combination of prior mobilization (PM), government corruption (GC), and non-repressive regime (NR).

This slide show from Charles C Ragin, provides a detailed explanation, including examples, that clearly demonstrates the question, 'What is QCA?'

This book, by Schneider and Wagemann, provides a comprehensive overview of the basic principles of set theory to model causality and applications of Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA), the most developed form of set-theoretic method, for research ac

This article by Nicolas Legewie provides an introduction to Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA). It discusses the method's main principles and advantages, including its concepts.

COMPASSS (Comparative methods for systematic cross-case analysis) is a website that has been designed to develop the use of systematic comparative case analysis as a research strategy by bringing together scholars and practitioners who share its use as

This paper from Patrick A. Mello focuses on reviewing current applications for use in Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) in order to take stock of what is available and highlight best practice in this area.

Marshall, G. (1998). Qualitative comparative analysis. In A Dictionary of Sociology Retrieved from https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/qualitative-comparative-analysis

Expand to view all resources related to 'Qualitative comparative analysis'

- An introduction to applied data analysis with qualitative comparative analysis

- Qualitative comparative analysis: A valuable approach to add to the evaluator’s ‘toolbox’? Lessons from recent applications

'Qualitative comparative analysis' is referenced in:

- 52 weeks of BetterEvaluation: Week 34 Generalisations from case studies?

- Week 18: is there a "right" approach to establishing causation in advocacy evaluation?

Framework/Guide

- Rainbow Framework : Check the results are consistent with causal contribution

- Data mining

Back to top

© 2022 BetterEvaluation. All right reserved.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Transl Behav Med

- v.4(2); 2014 Jun

Using qualitative comparative analysis to understand and quantify translation and implementation

Heather kane.

RTI International, 3040 Cornwallis Road, Research Triangle Park, P.O. Box 12194, Durham, NC 27709 USA

Megan A Lewis

Pamela a williams, leila c kahwati.

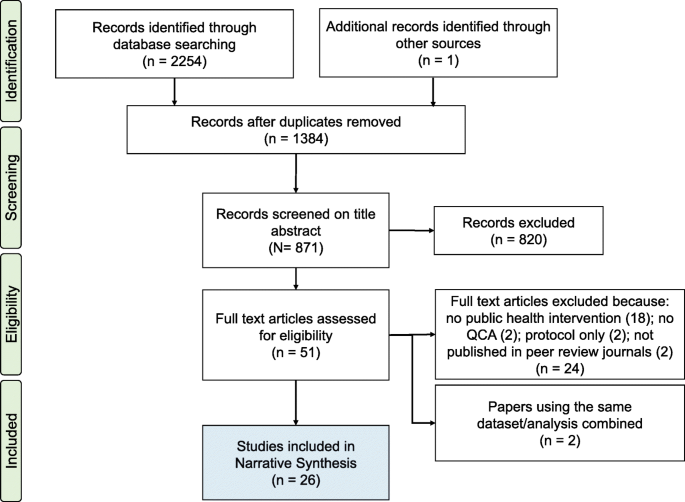

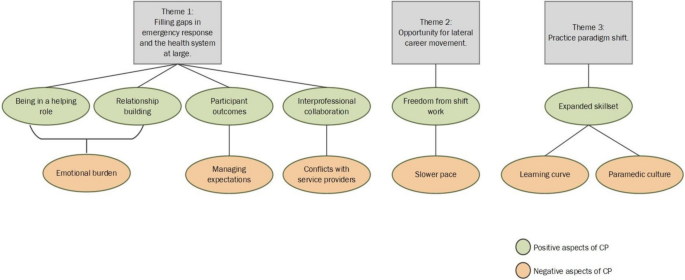

Understanding the factors that facilitate implementation of behavioral medicine programs into practice can advance translational science. Often, translation or implementation studies use case study methods with small sample sizes. Methodological approaches that systematize findings from these types of studies are needed to improve rigor and advance the field. Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) is a method and analytical approach that can advance implementation science. QCA offers an approach for rigorously conducting translational and implementation research limited by a small number of cases. We describe the methodological and analytic approach for using QCA and provide examples of its use in the health and health services literature. QCA brings together qualitative or quantitative data derived from cases to identify necessary and sufficient conditions for an outcome. QCA offers advantages for researchers interested in analyzing complex programs and for practitioners interested in developing programs that achieve successful health outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

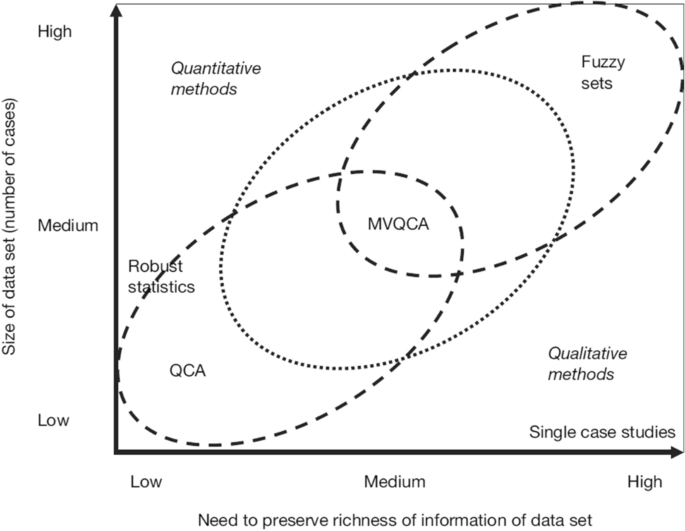

In this paper, we describe the methodological features and advantages of using qualitative comparative analysis (QCA). QCA is sometimes called a “mixed method.” It refers to both a specific research approach and an analytic technique that is distinct from and offers several advantages over traditional qualitative and quantitative methods [ 1 – 4 ]. It can be used to (1) analyze small to medium numbers of cases (e.g., 10 to 50) when traditional statistical methods are not possible, (2) examine complex combinations of explanatory factors associated with translation or implementation “success,” and (3) combine qualitative and quantitative data using a unified and systematic analytic approach.

This method may be especially pertinent for behavioral medicine given the growing interest in implementation science [ 5 ]. Translating behavioral medicine research and interventions into useful practice and policy requires an understanding of the implementation context. Understanding the context under which interventions work and how different ways of implementing an intervention lead to successful outcomes are required for “T3” (i.e., dissemination and implementation of evidence-based interventions) and “T4” translations (i.e., policy development to encourage evidence-based intervention use among various stakeholders) [ 6 , 7 ].

Case studies are a common way to assess different program implementation approaches and to examine complex systems (e.g., health care delivery systems, interventions in community settings) [ 8 ]. However, multiple case studies often have small, naturally limited samples or populations; small samples and populations lack adequate power to support conventional, statistical analyses. Case studies also may use mixed-method approaches, but typically when researchers collect quantitative and qualitative data in tandem, they rarely integrate both types of data systematically in the analysis. QCA offers solutions for the challenges posed by case studies and provides a useful analytic tool for translating research into policy recommendations. Using QCA methods could aid behavioral medicine researchers who seek to translate research from randomized controlled trials into practice settings to understand implementation. In this paper, we describe the conceptual basis of QCA, its application in the health and health services literature, and its features and limitations.

CONCEPTUAL BASIS OF QCA

QCA has its foundations in historical, comparative social science. Researchers in this field developed QCA because probabilistic methods failed to capture the complexity of social phenomena and required large sample sizes [ 1 ]. Recently, this method has made inroads into health research and evaluation [ 9 – 13 ] because of several useful features as follows: (1) it models equifinality , which is the ability to identify more than one causal pathway to an outcome (or absence of the outcome); (2) it identifies conjunctural causation , which means that single conditions may not display their effects on their own, but only in conjunction with other conditions; and (3) it implies asymmetrical relationships between causal conditions and outcomes, which means that causal pathways for achieving the outcome differ from causal pathways for failing to achieve the outcome.

QCA is a case-oriented approach that examines relationships between conditions (similar to explanatory variables in regression models) and an outcome using set theory; a branch of mathematics or of symbolic logic that deals with the nature and relations of sets. A set-theoretic approach to modeling causality differs from probabilistic methods, which examines the independent, additive influence of variables on an outcome. Regression models, based on underlying assumptions about sampling and distribution of the data, ask “what factor, holding all other factors constant at each factor’s average, will increase (or decrease) the likelihood of an outcome .” QCA, an approach based on the examination of set, subset, and superset relationships, asks “ what conditions —alone or in combination with other conditions—are necessary or sufficient to produce an outcome .” For additional QCA definitions, see Ragin [ 4 ].

Necessary conditions are those that exhibit a superset relationship with the outcome set and are conditions or combinations of conditions that must be present for an outcome to occur. In assessing necessity, a researcher “identifies conditions shared by cases with the same outcome” [ 4 ] (p. 20). Figure 1 shows a hypothetical example. In this figure, condition X is a necessary condition for an effective intervention because all cases with condition X are also members of the set of cases with the outcome present; however, condition X is not sufficient for an effective intervention because it is possible to be a member of the set of cases with condition X, but not be a member of the outcome set [ 14 ].

Necessary and sufficient conditions and set-theoretic relationships

Sufficient conditions exhibit subset relationships with an outcome set and demonstrate that “the cause in question produces the outcome in question” [ 3 ] (p. 92). Figure 1 shows the multiple and different combinations of conditions that produce the hypothetical outcome, “effective intervention,” (1) by having condition A present, (2) by having condition D present, or (3) by having the combination of conditions B and C present. None of these conditions is necessary and any one of these conditions or combinations of conditions is sufficient for the outcome of an effective intervention.

QCA AS AN APPROACH AND AS AN ANALYTIC TECHNIQUE

The term “QCA” is sometimes used to refer to the comparative research approach but also refers to the “analytic moment” during which Boolean algebra and set theory logic is applied to truth tables constructed from data derived from included cases. Figure 2 characterizes this distinction. Although this figure depicts steps as sequential, like many research endeavors, these steps are somewhat iterative, with respecification and reanalysis occurring along the way to final findings. We describe each of the essential steps of QCA as an approach and analytic technique and provide examples of how it has been used in health-related research.

QCA as an approach and as an analytic technique

Operationalizing the research question

Like other types of studies, the first step involves identifying the research question(s) and developing a conceptual model. This step guides the study as a whole and also informs case, condition (c.f., variable), and outcome selection. As mentioned above, QCA frames research questions differently than traditional quantitative or qualitative methods. Research questions appropriate for a QCA approach would seek to identify the necessary and sufficient conditions required to achieve the outcome. Thus, formulating a QCA research question emphasizes what program components or features—individually or in combination—need to be in place for a program or intervention to have a chance at being effective (i.e., necessary conditions) and what program components or features—individually or in combination—would produce the outcome (i.e., sufficient conditions). For example, a set theoretic hypothesis would be as follows: If a program is supported by strong organizational capacity and a comprehensive planning process, then the program will be successful. A hypothesis better addressed by probabilistic methods would be as follows: Organizational capacity, holding all other factors constant, increases the likelihood that a program will be successful.

For example, Longest and Thoits [ 15 ] drew on an extant stress process model to assess whether the pathways leading to psychological distress differed for women and men. Using QCA was appropriate for their study because the stress process model “suggests that particular patterns of predictors experienced in tandem may have unique relationships with health outcomes” (p. 4, italics added). They theorized that predictors would exhibit effects in combination because some aspects of the stress process model would buffer the risk of distress (e.g., social support) while others simultaneously would increase the risk (e.g., negative life events).

Identify cases

The number of cases in a QCA analysis may be determined by the population (e.g., 10 intervention sites, 30 grantees). When particular cases can be chosen from a larger population, Berg-Schlosser and De Meur [ 16 ] offer other strategies and best practices for choosing cases. Unless the number of cases relies on an existing population (i.e., 30 programs or grantees), the outcome of interest and existing theory drive case selection, unlike variable-oriented research [ 3 , 4 ] in which numbers are driven by statistical power considerations and depend on variation in the dependent variable. For use in causal inference, both cases that exhibit and do not exhibit the outcome should be included [ 16 ]. If a researcher is interested in developing typologies or concept formation, he or she may wish to examine similar cases that exhibit differences on the outcome or to explore cases that exhibit the same outcome [ 14 , 16 ].

For example, Kahwati et al. [ 9 ] examined the structure, policies, and processes that might lead to an effective clinical weight management program in a large national integrated health care system, as measured by mean weight loss among patients treated at the facility. To examine pathways that lead to both better and poorer facility-level weight loss, 11 facilities from among those with the largest weight loss outcomes and 11 facilities from among those with the smallest were included. By choosing cases based on specific outcomes, Kahwati et al. could identify multiple patterns of success (or failure) that explain the outcome rather than the variability associated with the outcome.

Identify conditions and outcome sets

Selecting conditions relies on the research question, conceptual model, and number of cases similar to other research methods. Conditions (or “sets” or “condition sets”) refer to the explanatory factors in a model; they are similar to variables. Because QCA research questions assess necessary and sufficient conditions, a researcher should consider which conditions in the conceptual model would theoretically produce the outcome individually or in combination. This helps to focus the analysis and number of conditions. Ideally, for a case study design with a small (e.g., 10–15) or intermediate (e.g., 16–100) number of cases, one should aim for fewer than five conditions because in QCA a researcher assesses all possible configurations of conditions. Adding conditions to the model increases the possible number of combinations exponentially (i.e., 2 k , where k = the number of conditions). For three conditions, eight possible combinations of the selected conditions exist as follows: the presence of A, B, C together, the lack of A with B and C present, the lack of A and lack of B with C present, and so forth. Having too many conditions will likely mean that no cases fall into a particular configuration, and that configuration cannot be assessed by empirical examples. When one or more configurations are not represented by the cases, this is known as limited diversity, and QCA experts suggest multiple strategies for managing such situations [ 4 , 14 ].

For example, Ford et al. [ 10 ] studied health departments’ implementation of core public health functions and organizational factors (e.g., resource availability, adaptability) and how those conditions lead to superior and inferior population health changes. They operationalized three core public functions (i.e., assessment of environmental and population public health needs, capacity for policy development, and authority over assurance of healthcare operations) and operationalized those for their study by using composite measures of varied health indicators compiled in a UnitedHealth Group report. In this examination of 41 state health departments, the authors found that all three core public health functions were necessary for population health improvement. The absence of any of the core public health functions was sufficient for poorer population health outcomes; thus, only the health departments with the ability to perform all three core functions had improved outcomes. Additionally, these three core functions in combination with either resource availability or adaptability were sufficient combinations (i.e., causal pathways) for improved population health outcomes.

Calibrate condition and outcome sets

Calibration refers to “adjusting (measures) so that they match or conform to dependably known standards” and is a common way of standardizing data in the physical sciences [ 4 ] (p. 72). Calibration requires the researcher to make sense of variation in the data and apply expert knowledge about what aspects of the variation are meaningful. Because calibration depends on defining conditions based on those “dependably known standards,” QCA relies on expert substantive knowledge, theory, or criteria external to the data themselves [ 14 ]. This may require researchers to collaborate closely with program implementers.

In QCA, one can use “crisp” set or “fuzzy” set calibration. Crisp sets, which are similar to dichotomous categorical variables in regression, establish decision rules defining a case as fully in the set (i.e., condition) or fully out of the set; fuzzy sets establish degrees of membership in a set. Fuzzy sets “differentiate between different levels of belonging anchored by two extreme membership scores at 1 and 0” [ 14 ] (p.28). They can be continuous (0, 0.1, 0.2,..) or have qualitatively defined anchor points (e.g., 0 is fully out of the set; 0.33 is more out than in the set; 0.66 is more in than out of the set; 1 is fully in the set). A researcher selects fuzzy sets and the corresponding resolution (i.e., continuous, four cutoff points, six cutoff) based on theory and meaningful differences between cases and must be able to provide a verbal description for each cutoff point [ 14 ]. If, for example, a researcher cannot distinguish between 0.7 and 0.8 membership in a set, then a more continuous scoring of cases would not be useful, rather a four point cutoff may better characterize the data. Although crisp and fuzzy sets are more commonly used, new multivariate forms of QCA are emerging as are variants that incorporate elements of time [ 14 , 17 , 18 ].

Fuzzy sets have the advantage of maintaining more detail for data with continuous values. However, this strength also makes interpretation more difficult. When an observation is coded with fuzzy sets, a particular observation has some degree of membership in the set “condition A” and in the set “condition NOT A.” Thus, when doing analyses to identify sufficient conditions, a researcher must make a judgment call on what benchmark constitutes recommendation threshold for policy or programmatic action.

In creating decision rules for calibration, a researcher can use a variety of techniques to identify cutoff points or anchors. For qualitative conditions, a researcher can define decision rules by drawing from the literature and knowledge of the intervention context. For conditions with numeric values, a researcher can also employ statistical approaches. Ideally, when using statistical approaches, a researcher should establish thresholds using substantive knowledge about set membership (thus, translating variation into meaningful categories). Although measures of central tendency (e.g., cases with a value above the median are considered fully in the set) can be used to set cutoff points, some experts consider the sole use of this method to be flawed because case classification is determined by a case’s relative value in regard to other cases as opposed to its absolute value in reference to an external referent [ 14 ].

For example, in their study of National Cancer Institutes’ Community Clinical Oncology Program (NCI CCOP), Weiner et al. [ 19 ] had numeric data on their five study measures. They transformed their study measures by using their knowledge of the CCOP and by asking NCI officials to identify three values: full membership in a set, a point of maximum ambiguity, and nonmembership in the set. For their outcome set, high accrual in clinical trials, they established 100 patients enrolled accrual as fully in the set of high accrual, 70 as a point of ambiguity (neither in nor out of the set), and 50 and below as fully out of the set because “CCOPs must maintain a minimum of 50 patients to maintain CCOP funding” (p. 288). By using QCA and operationalizing condition sets in this way, they were able to answer what condition sets produce high accrual, not what factors predict more accrual. The advantage is that by using this approach and analytic technique, they were able to identify sets of factors that are linked with a very specific outcome of interest.

Obtain primary or secondary data

Data sources vary based on the study, availability of the data, and feasibility of data collection; data can be qualitative or quantitative, a feature useful for mixed-methods studies and systematically integrating these different types of data is a major strength of this approach. Qualitative data include program documents and descriptions, key informant interviews, and archival data (e.g., program documents, records, policies); quantitative data consists of surveys, surveillance or registry data, and electronic health records.

For instance, Schensul et al. [ 20 ] relied on in-depth interviews for their analysis; Chuang et al. [ 21 ] and Longest and Thoits [ 15 ] drew on survey data for theirs. Kahwati et al. [ 9 ] used a mixed-method approach combining data from key informant interviews, program documents, and electronic health records. Any type of data can be used to inform the calibration of conditions.

Assign set membership scores

Assigning set membership scores involves applying the decision rules that were established during the calibration phase. To accomplish this, the research team should then use the extracted data for each case, apply the decision rule for the condition, and discuss discrepancies in the data sources. In their study of factors that influence health care policy development in Florida, Harkreader and Imershein [ 22 ] coded contextual factors that supported state involvement in the health care market. Drawing on a review of archival data and using crisp set coding, they assigned a value of 1 for the presence of a contextual factor (e.g., presence of federal financial incentives promoting policy, unified health care provider policy position in opposition to state policy, state agency supporting policy position) and 0 for the absence of a contextual factor.

Construct truth table

After completing the coding, researchers create a “truth table” for analysis. A truth table lists all of the possible configurations of conditions, the number of cases that fall into that configuration, and the “consistency” of the cases. Consistency quantifies the extent to which cases that share similar conditions exhibit the same outcome; in crisp sets, the consistency value is the proportion of cases that exhibit the outcome. Fuzzy sets require a different calculation to establish consistency and are described at length in other sources [ 1 – 4 , 14 ]. Table 1 displays a hypothetical truth table for three conditions using crisp sets.

Sample of a hypothetical truth table for crisp sets

1 fully in the set, 0 fully out of the set

QCA AS AN ANALYTIC TECHNIQUE

The research steps to this point fall into QCA as an approach to understanding social and health phenomena. Analysis of the truth table is the sine qua non of QCA as an analytic technique. In this section, we provide an overview of the analysis process, but analytic techniques and emerging forms of analysis are described in multiple texts [ 3 , 4 , 14 , 17 ]. The use of computer software to conduct truth table analysis is recommended and several software options are available including Stata, fsQCA, Tosmana, and R.

A truth table analysis first involves the researcher assessing which (if any) conditions are individually necessary or sufficient for achieving the outcome, and then second, examining whether any configurations of conditions are necessary or sufficient. In instances where contradictions in outcomes from the same configuration pattern occur (i.e., one case from a configuration has the outcome; one does not), the researcher should also consider whether the model is properly specified and conditions are calibrated accurately. Thus, this stage of the analysis may reveal the need to review how conditions are defined and whether the definition should be recalibrated. Similar to qualitative and quantitative research approaches, analysis is iterative.

Additionally, the researcher examines the truth table to assess whether all logically possible configurations have empiric cases. As described above, when configurations lack cases, the problem of limited diversity occurs. Configurations without representative cases are known as logical remainders, and the researcher must consider how to deal with those. The analysis of logical remainders depends on the particular theory guiding the research and the research priorities. How a researcher manages the logical remainders has implications for the final solution, but none of the solutions based on the truth table will contradict the empirical evidence [ 14 ]. To generate the most conservative solution term, a researcher makes no assumptions about truth table rows with no cases (or very few cases in larger N studies) and excludes them from the logical minimization process. Alternately, a researcher can choose to include (or exclude) rows with no cases from analysis, which would generate a solution that is a superset of the conservative solution. Choosing inclusion criteria for logical remainders also depends on theory and what may be empirically possible. For example, in studying governments, it would be unlikely to have a case that is a democracy (“condition A”), but has a dictator (“condition B”). In that circumstance, the researcher may choose to exclude that theoretically implausible row from the logical minimization process.

Third, once all the solutions have been identified, the researcher mathematically reduces the solution [ 1 , 14 ]. For example, if the list of solutions contains two identical configurations, except that in one configuration A is absent and in the other A is present, then A can be dropped from those two solutions. Finally, the researcher computes two parameters of fit: coverage and consistency. Coverage determines the empirical relevance of a solution and quantifies the variation in causal pathways to an outcome [ 14 ]. When coverage of a causal pathway is high, the more common the solution is, and more of the outcome is accounted for by the pathway. However, maximum coverage may be less critical in implementation research because understanding all of the pathways to success may be as helpful as understanding the most common pathway. Consistency assesses whether the causal pathway produces the outcome regularly (“the degree to which the empirical data are in line with a postulated subset relation,” p. 324 [ 14 ]); a high consistency value (e.g., 1.00 or 100 %) would indicate that all cases in a causal pathway produced the outcome. A low consistency value would suggest that a particular pathway was not successful in producing the outcome on a regular basis, and thus, for translational purposes, should not be recommended for policy or practice changes. A causal pathway with high consistency and coverage values indicates a result useful for providing guidance; a high consistency with a lower coverage score also has value in showing a causal pathway that successfully produced the outcome, but did so less frequently.

For example, Kahwati et al. [ 9 ] examined their truth table and analyzed the data for single conditions and combinations of conditions that were necessary for higher or lower facility-level patient weight loss outcomes. The truth table analysis revealed two necessary conditions and four sufficient combinations of conditions. Because of significant challenges with logical remainders, they used a bottom-up approach to assess whether combinations of conditions yielded the outcome. This entailed pairing conditions to ensure parsimony and maximize coverage. With a smaller number of conditions, a researcher could hypothetically find that more cases share similar characteristics and could assess whether those cases exhibit the same outcome of interest.

At the completion of the truth table analysis, Kahwati et al. [ 9 ] used the qualitative data from site interviews to provide rich examples to illustrate the QCA solutions that were identified, which explained what the solutions meant in clinical practice for weight management. For example, having an involved champion (usually a physician), in combination with low facility accountability, was sufficient for program success (i.e., better weight loss outcomes) and was related to better facility weight loss. In reviewing the qualitative data, Kahwati et al. [ 9 ] discovered that involved champions integrate program activities into their clinical routines and discuss issues as they arise with other program staff. Because involved champions and other program staff communicated informally on a regular basis, formal accountability structures were less of a priority.

ADVANTAGES AND LIMITATIONS OF QCA

Because translational (and other health-related) researchers may be interested in which intervention features—alone or in combination—achieve distinct outcomes (e.g., achievement of program outcomes, reduction in health disparities), QCA is well suited for translational research. To assess combinations of variables in regression, a researcher relies on interaction effects, which, although useful, become difficult to interpret when three, four, or more variables are combined. Furthermore, in regression and other variable-oriented approaches, independent variables are held constant at the average across the study population to isolate the independent effect of that variable, but this masks how factors may interact with each other in ways that impact the ultimate outcomes. In translational research, context matters and QCA treats each case holistically, allowing each case to keep its own values for each condition.

Multiple case studies or studies with the organization as the unit of analysis often involve a small or intermediate number of cases. This hinders the use of standard statistical analyses; researchers are less likely to find statistical significance with small sample sizes. However, QCA draws on analyses of set relations to support small-N studies and to identify the conditions or combinations of conditions that are necessary or sufficient for an outcome of interest and may yield results when probabilistic methods cannot.

Finally, QCA is based on an asymmetric concept of causation , which means that the absence of a sufficient condition associated with an outcome does not necessarily describe the causal pathway to the absence of the outcome [ 14 ]. These characteristics can be helpful for translational researchers who are trying to study or implement complex interventions, where more than one way to implement a program might be effective and where studying both effective and ineffective implementation practices can yield useful information.

QCA has several limitations that researchers should consider before choosing it as a potential methodological approach. With small- and intermediate-N studies, QCA must be theory-driven and circumscribed by priority questions. That is, a researcher ideally should not use a “kitchen sink” approach to test every conceivable condition or combination of conditions because the number of combinations increases exponentially with the addition of another condition. With a small number of cases and too many conditions, the sample would not have enough cases to provide examples of all the possible configurations of conditions (i.e., limited diversity), or the analysis would be constrained to describing the characteristics of the cases, which would have less value than determining whether some conditions or some combination of conditions led to actual program success. However, if the number of conditions cannot be reduced, alternate QCA techniques, such as a bottom-up approach to QCA or two-step QCA, can be used [ 14 ].

Another limitation is that programs or clinical interventions involved in a cross-site analysis may have unique programs that do not seem comparable. Cases must share some degree of comparability to use QCA [ 16 ]. Researchers can manage this challenge by taking a broader view of the program(s) and comparing them on broader characteristics or concepts, such as high/low organizational capacity, established partnerships, and program planning, if these would provide meaningful conclusions. Taking this approach will require careful definition of each of these concepts within the context of a particular initiative. Definitions may also need to be revised as the data are gathered and calibration begins.

Finally, as mentioned above, crisp set calibration dichotomizes conditions of interest; this form of calibration means that in some cases, the finer grained differences and precision in a condition may be lost [ 3 ]. Crisp set calibration provides more easily interpretable and actionable results and is appropriate if researchers are primarily interested in the presence or absence of a particular program feature or organizational characteristic to understand translation or implementation.

QCA offers an additional methodological approach for researchers to conduct rigorous comparative analyses while drawing on the rich, detailed data collected as part of a case study. However, as Rihoux, Benoit, and Ragin [ 17 ] note, QCA is not a miracle method, nor a panacea for all studies that use case study methods. Furthermore, it may not always be the most suitable approach for certain types of translational and implementation research. We outlined the multiple steps needed to conduct a comprehensive QCA. QCA is a good approach for the examination of causal complexity, and equifinality could be helpful to behavioral medicine researchers who seek to translate evidence-based interventions in real-world settings. In reality, multiple program models can lead to success, and this method accommodates a more complex and varied understanding of these patterns and factors.

Implications

Practice : Identifying multiple successful intervention models (equifinality) can aid in selecting a practice model relevant to a context, and can facilitate implementation.

Policy : QCA can be used to develop actionable policy information for decision makers that accommodates contextual factors.

Research : Researchers can use QCA to understand causal complexity in translational or implementation research and to assess the relationships between policies, interventions, or procedures and successful outcomes.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA)

Introduction.

- The Emergence of QCA

- Comparisons with Other Techniques

- Criticisms of QCA

- Case Selection and Combining Cross-Case and Within-Case Analysis

- Model Specification and Parameters of Fit

- Applications of QCA

- QCA Software

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Qualitative Methods in Sociological Research

- Quantitative Methods in Sociological Research

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Consumer Credit and Debt

- Global Inequalities

- LGBTQ+ Spaces

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) by Axel Marx LAST REVIEWED: 13 November 2018 LAST MODIFIED: 28 November 2016 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756384-0188

The social sciences use a wide range of research methods and techniques ranging from experiments to techniques which analyze observational data such as statistical techniques, qualitative text analytic techniques, ethnographies, and many others. In the 1980s a new technique emerged, named Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA), which aimed to provide a formalized way to systematically compare a small number (5<N<75) of case studies. John Gerring in the 2001 version of his introduction to social sciences identified QCA as one of the only genuine methodological innovations of the last few decades. In recent years, QCA has also been applied to large-N studies ( Glaesser 2015 , cited under Applications of QCA ; Ragin 2008 , cited under The Essential Features of QCA ) and the application of QCA to perform large-N analysis is in full development. This annotated bibliography aims to provide an overview of the main contributions of QCA as a research technique as well as an introduction to some specific issues as well as QCA applications. The contribution starts with sketching the emergence of QCA and situating the method in the debate between “qualitative” and “quantitative” methods. This contextualization is important to understand and appreciate that QCA in essence is a qualitative case-based research technique and not a quantitative variable-oriented technique. Next, the article discusses some key features of QCA and identifies some of the main books and handbooks on QCA as well as some of the criticism. In a third section, the overview focuses attention on the importance of cases and case selection in QCA. The fourth section introduces the way in which QCA builds explanatory models and presents the key contributions on the selection of explanatory factors, model specification, and testing. The fifth section canvasses the applications of QCA in the social sciences and identifies some interesting examples. Finally, since QCA is a formalized data-analytic technique based on algorithms, the overview ends with an overview of the main software package which can assist in the application of QCA.

Qualitative Case-Based Research in the Social Sciences

This section grounds Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) in the tradition of qualitative case-based methods. As a research approach QCA mainly focuses on the systematic comparison of cases in order to find patterns of difference and similarity between cases. The initial intention of Ragin 1987 (cited under The Essential Features of QCA ) was to develop an original “synthetic strategy” as a middle way between the case-oriented (or “qualitative”) and the variable-oriented (or “quantitative”) approaches, which would “integrate the best features of the case-oriented approach with the best features of the variable-oriented approach” ( Ragin 1987 , p. 84). However, instead of grounding qualitative research on the premises of quantitative research such as King, et al. 1994 did, Ragin aimed to develop a method which is firmly rooted on a case-based qualitative approach ( Ragin and Becker 1992 ; Ragin 1997 for a systematic discussion of the differences between QCA and the approach advocated by King, et al. 1994 ). In recent years the fundamental differences between case-based and variable-oriented approaches have been further elaborated in terms of selection of units of observation or cases, approaches to explanation, causal analysis, measurement of concepts, and external validity (scope and generalization). Many researchers including Charles Ragin, Andrew Bennett ( George and Bennett 2005 ), John Gerring ( Gerring 2007 , Gerring 2012 ), David Collier ( Brady and Collier 2004 ) and James Mahoney ( Mahoney and Rueschemeyer 2003 ) have contributed significantly to identifying the key ontological, epistemological, and logical differences between the two approaches. Goertz and Mahoney 2012 brings this literature together and shows the distinct differences between quantitative and qualitative research. The authors refer to two “cultures” of conducting social-scientific research. In this distinction QCA falls firmly in the “camp” of qualitative research. The overview below identifies some key texts which discuss these differences more in depth.

Brady, H., and D. Collier, eds. 2004. Rethinking social inquiry: Diverse tools, shared standards . Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

This edited volume goes into a detailed discussion with King, et al. 1994 and shows the distinctive strengths of different approaches with a strong emphasis on the distinctive strengths of qualitative case-based methods. Book also introduces the idea of process-tracing for within-case analysis. Reprint 2010.

George, A., and A. Bennett. 2005. Case research and theory development . Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Very extensive treatment of how case-based research focusing on longitudinal analysis and process-tracing can contribute to both theory development and theory testing. Discusses many examples from empirical political science research.

Gerring, J. 2007. Case study research: Principles and practice . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Very good introduction into what a case study is and what analytic and descriptive purposes it serves in social science research.

Gerring, J. 2012. Social science methodology: A unified framework . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

An update of the 2001 volume which provides a concise introduction to different research approaches and techniques in the social sciences. Clearly shows the added value of different approaches and aims to overcome “the one versus the other” approaches.

Goertz, G., and J. Mahoney. 2012. A tale of two cultures: Qualitative and quantitative research in the social sciences . Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

Book elaborates the differences between qualitative and quantitative research. They elaborate these differences in terms of (1) approaches to explanation, (2) conceptions of causation, (3) approaches toward multivariate explanations, (4) equifinality, (5) scope and causal generalization, (6) case selection, (7) weighting observations, (8) substantively important cases, (9) lack of fit, and (10) concepts and measurement.

King, G., R. Keohane, and S. Verba. 1994. Designing social enquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative research . Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

A much-quoted and highly influential book on research design for the social sciences. This book aimed to discuss and assess qualitative research and argued that qualitative research should be benchmarked against standards used in quantitative research such as never select cases on the dependent variables, making sure one has always more observations than variables, maximize variation, and so on.

Mahoney, J., and D. Rueschemeyer, eds. 2003. Comparative historical analysis in the social sciences . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

This is a very impressive volume with chapters written by the best researchers in macro-sociological research and comparative politics. It shows the key strengths of comparative historical research for explaining key social phenomena such as revolutions, social provisions, and democracy. In addition it combines masterfully substantive discussions with methodological implications and challenges and in this way shows how case-based research contributes fundamentally to understanding social change.

Poteete, A., M. Janssen, and E. Ostrom. 2010. Working together: Collective action, the commons and multiple methods in practice . Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

The study of Common Pool Resources (CPRs) has been one of the most theoretically advanced subjects in social sciences. This excellent book introduces different research designs to analyze questions related to the governance of CPRs and situates QCA nicely in the universe of different research designs and strategies.

Ragin, C. C. 1997. Turning the tables: How case-oriented methods challenge variable-oriented methods. Comparative Social Research 16:27–42.

Engages directly with the work of King, et al. 1994 and fundamentally disagrees with its authors Ragin argues that qualitative case-based research is based on different standards and that this type of research should be assessed on the basis of these standards.

Ragin, C. C., and H. Becker. 1992. What is a case? Exploring the foundations of social inquiry . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Brings together leading researchers to discuss the deceptively easy question “what is a case?” and shows the many different approaches toward case-study research. One red line going through the contributions is the emphasis on thinking hard about the question “what is my case a case of?” in theoretical terms.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Sociology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Actor-Network Theory

- Adolescence

- African Americans

- African Societies

- Agent-Based Modeling

- Analysis, Spatial

- Analysis, World-Systems

- Anomie and Strain Theory

- Arab Spring, Mobilization, and Contentious Politics in the...

- Asian Americans

- Assimilation

- Authority and Work

- Bell, Daniel

- Biosociology

- Bourdieu, Pierre

- Catholicism

- Causal Inference

- Chicago School of Sociology

- Chinese Cultural Revolution

- Chinese Society

- Citizenship

- Civil Rights

- Civil Society

- Cognitive Sociology

- Cohort Analysis

- Collective Efficacy

- Collective Memory

- Comparative Historical Sociology

- Comte, Auguste

- Conflict Theory

- Conservatism

- Consumer Culture

- Consumption

- Contemporary Family Issues

- Contingent Work

- Conversation Analysis

- Corrections

- Cosmopolitanism

- Crime, Cities and

- Cultural Capital

- Cultural Classification and Codes

- Cultural Economy

- Cultural Omnivorousness

- Cultural Production and Circulation

- Culture and Networks

- Culture, Sociology of

- Development

- Discrimination

- Doing Gender

- Du Bois, W.E.B.

- Durkheim, Émile

- Economic Institutions and Institutional Change

- Economic Sociology

- Education and Health

- Education Policy in the United States

- Educational Policy and Race

- Empires and Colonialism

- Entrepreneurship

- Environmental Sociology

- Epistemology

- Ethnic Enclaves

- Ethnomethodology and Conversation Analysis

- Exchange Theory

- Families, Postmodern

- Family Policies

- Feminist Theory

- Field, Bourdieu's Concept of

- Forced Migration

- Foucault, Michel

- Frankfurt School

- Gender and Bodies

- Gender and Crime

- Gender and Education

- Gender and Health

- Gender and Incarceration

- Gender and Professions

- Gender and Social Movements

- Gender and Work

- Gender Pay Gap

- Gender, Sexuality, and Migration

- Gender Stratification

- Gender, Welfare Policy and

- Gendered Sexuality

- Gentrification

- Gerontology

- Globalization and Labor

- Goffman, Erving

- Historic Preservation

- Human Trafficking

- Immigration

- Indian Society, Contemporary

- Institutions

- Intellectuals

- Intersectionalities

- Interview Methodology

- Job Quality

- Knowledge, Critical Sociology of

- Labor Markets

- Latino/Latina Studies

- Law and Society

- Law, Sociology of

- LGBT Parenting and Family Formation

- LGBT Social Movements

- Life Course

- Lipset, S.M.

- Markets, Conventions and Categories in

- Marriage and Divorce

- Marxist Sociology

- Masculinity

- Mass Incarceration in the United States and its Collateral...

- Material Culture

- Mathematical Sociology

- Medical Sociology

- Mental Illness

- Methodological Individualism

- Middle Classes

- Military Sociology

- Money and Credit

- Multiculturalism

- Multilevel Models

- Multiracial, Mixed-Race, and Biracial Identities

- Nationalism

- Non-normative Sexuality Studies

- Occupations and Professions

- Organizations

- Panel Studies

- Parsons, Talcott

- Political Culture

- Political Economy

- Political Sociology

- Popular Culture

- Proletariat (Working Class)

- Protestantism

- Public Opinion

- Public Space

- Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA)

- Race and Sexuality

- Race and Violence

- Race and Youth

- Race in Global Perspective

- Race, Organizations, and Movements

- Rational Choice

- Relationships

- Religion and the Public Sphere

- Residential Segregation

- Revolutions

- Role Theory

- Rural Sociology

- Scientific Networks

- Secularization

- Sequence Analysis

- Sex versus Gender

- Sexual Identity

- Sexualities

- Sexuality Across the Life Course

- Simmel, Georg

- Single Parents in Context

- Small Cities

- Social Capital

- Social Change

- Social Closure

- Social Construction of Crime

- Social Control

- Social Darwinism

- Social Disorganization Theory

- Social Epidemiology

- Social History

- Social Indicators

- Social Mobility

- Social Movements

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Networks

- Social Policy

- Social Problems

- Social Psychology

- Social Stratification

- Social Theory

- Socialization, Sociological Perspectives on

- Sociolinguistics

- Sociological Approaches to Character

- Sociological Research on the Chinese Society

- Sociological Research, Qualitative Methods in

- Sociological Research, Quantitative Methods in

- Sociology, History of

- Sociology of Manners

- Sociology of Music

- Sociology of War, The

- Suburbanism

- Survey Methods

- Symbolic Boundaries

- Symbolic Interactionism

- The Division of Labor after Durkheim

- Tilly, Charles

- Time Use and Childcare

- Time Use and Time Diary Research

- Tourism, Sociology of

- Transnational Adoption

- Unions and Inequality

- Urban Ethnography

- Urban Growth Machine

- Urban Inequality in the United States

- Veblen, Thorstein

- Visual Arts, Music, and Aesthetic Experience

- Wallerstein, Immanuel

- Welfare, Race, and the American Imagination

- Welfare States

- Women’s Employment and Economic Inequality Between Househo...

- Work and Employment, Sociology of

- Work/Life Balance

- Workplace Flexibility

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.150.64]

- 185.80.150.64

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics