LOGIN

Annual Report

- Board of Directors

- Nomination Process

- Organizational Structure

- ATS Policies

- ATS Website

- MyATS Tutorial

- ATS Experts

- Press Releases

Member Newsletters

- ATS in the News

- ATS Conference News

- Embargo Policy

ATS Social Media

Breathe easy podcasts, ethics & coi, health equity, industry resources.

- Value of Collaboration

- Corporate Members

- Advertising Opportunities

- Clinical Trials

- Financial Disclosure

In Memoriam

Global health.

- International Trainee Scholarships (ITS)

- MECOR Program

- Forum of International Respiratory Societies (FIRS)

- 2019 Latin American Critical Care Conference

Peer Organizations

Careers at ats, affordable care act, ats comments and testimony, forum of international respiratory societies, tobacco control, tuberculosis, washington letter, clinical resources.

- ATS Quick Hits

- Asthma Center

Best of ATS Video Lecture Series

- Coronavirus

- Critical Care

- Disaster Related Resources

- Disease Related Resources

- Resources for Patients

- Resources for Practices

- Vaccine Resource Center

Career Development

- Resident & Medical Students

- Junior Faculty

- Training Program Directors

- ATS Reading List

- ATS Scholarships

- ATS Virtual Network

ATS Podcasts

Ats webinars, professional accreditation, pulmonary function testing (pft), calendar of events, patient resources.

- Asthma Today

- Breathing in America

- Fact Sheets: A-Z

- Fact Sheets: Topic Specific

- Patient Videos

- Other Patient Resources

Lung Disease Week

Public advisory roundtable.

- PAR Publications

- PAR at the ATS Conference

Assemblies & Sections

- Abstract Scholarships

- ATS Mentoring Programs

- ATS Official Documents

- ATS Interest Groups

- Genetics and Genomics

- Medical Education

- Terrorism and Inhalation Disasters

- Allergy, Immunology & Inflammation

- Behavioral Science and Health Services Research

- Clinical Problems

- Environmental, Occupational & Population Health

- Pulmonary Circulation

- Pulmonary Infections and Tuberculosis

- Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Respiratory Cell & Molecular Biology

- Respiratory Structure & Function

- Sleep & Respiratory Neurobiology

- Thoracic Oncology

- Joint ATS/CHEST Clinical Practice Committee

- Clinicians Advisory

- Council of Chapter Representatives

- Documents Development and Implementation

- Drug/Device Discovery and Development

- Environmental Health Policy

- Ethics and Conflict of Interest

- Health Equity and Diversity Committee

- Health Policy

- International Conference Committee

- International Health

- Members In Transition and Training

- View more...

- Membership Benefits

- Categories & Fees

- Special Membership Programs

- Renew Your Membership

- Update Your Profile

- ATS DocMatter Community

- Respiratory Medicine Book Series

- Elizabeth A. Rich, MD Award

- Member Directory

- ATS Career Center

- Welcome Trainees

- ATS Wellness

- Thoracic Society Chapters

- Chapter Publications

- CME Sponsorship

Corporate Membership

- Assemblies and Sections

Webinar Date: March 7, 2023

This webinar is focused on providing our perspective on the importance of macro cognition and team cognition in the decision-making process in healthcare settings, most notably the intensive care unit (ICU). The webinar includes live presentations by experts in the field followed by an interactive session from attendees. This webinar features renowned experts: Abdullah Alismail, PhD, RRT, FCCP, FAARC Associate Professor of Cardiopulmonary Sciences & Medicine Department of Cardiopulmonary Sciences, School of Allied Health Professions, Loma Linda University Health, Loma Linda, CA Lauren Blackwell, MD Assistant Professor of Medicine Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai Beth Israel, New York, NY Sugeet K. Jagpal, MD Assistant Professor Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ May Lee, MD, ATSF, FCCP, FACP Clinical Associate Professor of Medicine Director, Pulmonary and Critical Care Fellowship Program Keck Medical Center of USC, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care, Los Angeles, CA Erica Lin, MD Assistant Professor Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA

Jared Chiarchiaro, MD MS Associate Professor of Medicine Clinical Chief, Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, & Critical Care Medicine Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR

Nayla Ahmed, M.B.B.S Pulmonary & Critical Care medicine fellow at Mayo Clinic We invite your participation in this session and look forward to an insightful discussion. If you have questions about this session or have suggestions for future sessions, please contact: Avraham Cooper ATS Section on Medical Education [email protected]

The American Thoracic Society improves global health by advancing research, patient care, and public health in pulmonary disease, critical illness, and sleep disorders. Founded in 1905 to combat TB, the ATS has grown to tackle asthma, COPD, lung cancer, sepsis, acute respiratory distress, and sleep apnea, among other diseases.

AMERICAN THORACIC SOCIETY 25 Broadway New York, NY 10004 United States of America Phone: +1 (212) 315-8600 Fax: +1 (212) 315-6498 Email: [email protected]

Privacy Statement | Term of Use | COI Conference Code of Conduct

Critical Thinking in Critical Care: Five Strategies to Improve Teaching and Learning in the Intensive Care Unit

Affiliations.

- 1 1 Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

- 2 2 Shapiro Institute for Education and Research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; and.

- 3 3 Critical Care Medicine Department, Clinical Center, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Massachusetts.

- PMID: 28157389

- PMCID: PMC5461985

- DOI: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201612-1009AS

Critical thinking, the capacity to be deliberate about thinking, is increasingly the focus of undergraduate medical education, but is not commonly addressed in graduate medical education. Without critical thinking, physicians, and particularly residents, are prone to cognitive errors, which can lead to diagnostic errors, especially in a high-stakes environment such as the intensive care unit. Although challenging, critical thinking skills can be taught. At this time, there is a paucity of data to support an educational gold standard for teaching critical thinking, but we believe that five strategies, routed in cognitive theory and our personal teaching experiences, provide an effective framework to teach critical thinking in the intensive care unit. The five strategies are: make the thinking process explicit by helping learners understand that the brain uses two cognitive processes: type 1, an intuitive pattern-recognizing process, and type 2, an analytic process; discuss cognitive biases, such as premature closure, and teach residents to minimize biases by expressing uncertainty and keeping differentials broad; model and teach inductive reasoning by utilizing concept and mechanism maps and explicitly teach how this reasoning differs from the more commonly used hypothetico-deductive reasoning; use questions to stimulate critical thinking: "how" or "why" questions can be used to coach trainees and to uncover their thought processes; and assess and provide feedback on learner's critical thinking. We believe these five strategies provide practical approaches for teaching critical thinking in the intensive care unit.

Keywords: cognitive errors; critical care; critical thinking; medical education.

- Clinical Competence*

- Critical Care*

- Education, Medical, Graduate / methods*

- Intensive Care Units

- Quality Improvement

- Medical Books

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Critical Thinking in the Intensive Care Unit: Skills to Assess, Analyze, and Act

Introduction: Critical thinking in the intensive care unit Chapter 1: Defining critical thinking Chapter 2: New graduate nurses and critical thinking Chapter 3: The critical thinking classroom Chapter 4: Orientation: Bringing critical thinking to the clinical environment Chapter 5: Nursing practice that promotes and motivates critical thinking Chapter 6: Novice to expert: Setting realistic expectations for critical thinking Chapter 7: Applying critical thinking to nursing documentation Chapter 8: Relating critical thinking to its higher purpose Chapter 9: Resources and tools

- ISBN-10 1578399718

- ISBN-13 978-1578399710

- Publisher HCPro, Inc.

- Publication date March 16, 2007

- Language English

- Dimensions 8.5 x 0.5 x 11 inches

- Print length 160 pages

- See all details

Editorial Reviews

About the author.

Polly Gerber Zimmermann, RN, MS, MBA, CEN, has been active in emergency and medical-surgical nursing clinical practice for more than 29 years and involved in nurse education for more than 10 years. She is a tenured assistant professor in the Department of Nursing at the Harry S. Truman College (Chicago).

Product details

- Publisher : HCPro, Inc. (March 16, 2007)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 160 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1578399718

- ISBN-13 : 978-1578399710

- Item Weight : 1 pounds

- Dimensions : 8.5 x 0.5 x 11 inches

- #147 in Critical & Intensive Care Nursing (Books)

- #728 in Nursing Critical & Intensive care

- #1,172 in Critical Care

About the author

Shelley cohen.

Although emergency nursing has been my passion for more than 35 years, I realized that many critical thinking skills cross nursing specialties. I also learned the value of nurse leadership in staff development, retention, and impact on work culture.

Combine all of the above and I have had the privilege to speak internationally on triage, leadership, and critical thinking skills. The content for these programs evolved into the release of more than 15 books and numerous articles.

I continue to work (this is my 42nd year as a nurse!) as a prn staff nurse in an emergency department in Tennessee. My clinical hours keep me grounded in the realities nurses and nurse leaders continues to face and the growing needs we have for professional development.

From authoring online triage courses to the critical thinking series as well as working with Kathleen Bartholomew on the Image of Nursing- the journey as an author has made me a better nurse.

When I do take off my stethoscope and close up the laptop, my husband Dennis and I sponsor Purple Heart heroes on our property for hunting events. This work is done through Wounded Warriors in Action Foundation (www.wwiaf.org).

Email me your feedback on any of the published works, your opinion matters!

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Publisher Home

- Editorial Board

- Submit Manuscript

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Application of evidence-based practice in intensive and critical care nursing, article information.

Identifiers and Pagination:

Article history:, article metrics, crossref citations:, total statistics:, unique statistics:.

Background:

Evidence-based solutions are the main point of high-quality and patient-centered care. Studies analyzing the implementation of evidence-based nursing are an integral part of quality improvement. The study aims to analyze the application of evidence-based practice in intensive and critical care nursing.

This research was performed in the Hospital of Lithuanian University of Health Sciences Kaunas Clinics in intensive care units (ICU) departments in 2019. 202 critical care nurses participated in this survey (response rate 94.3%)—method of research – anonymous questionnaire. Research object – implementing evidence-based nursing practice among nurses working in intensive care units. Research instrument – questionnaire composed by McEvoy et al. (2010) [1]. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 24.0 and MS Excel 2016 software. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse our sample and presented in percentages. Quantitive data are presented as mean with standard deviation (m±SD). Among exploratory groups, a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Nurses with higher university education claim to know evidence-based nursing terminology better with a statistical significance (p= 0.001) and to have higher self-confidence in evidence application (p= 0.001) compared to nurses with professional or higher non-university education. It has been determined that age directly correlates with the implementation of evidence-based nursing: compared to their older colleagues, younger nurses have statistically significantly more knowledge (p= 0.001), skills (p= 0.012) and self-confidence when applying evidence (p= 0.001) as well as a more positive approach to evidence-based nursing (p= 0.041). Nurses whose total work experience exceeds 20 years have statistically significantly less knowledge of evidence-based practice terminology than nurses whose work experience is 10 years or less (p= 0.001). It has been determined that Intensive and Critical Care Nurses (ICU Nurses) with 10 years or less experience under their belt know the terms related to evidence-based nursing statistically significantly better (p= 0.001) and applies evidence-based knowledge in clinical practice more often, compared to nurses who have worked in the ICU for longer, e.g. , 11-20 years or more than 20 years (p= 0.006). Compared to the nurses working in the ICU for 11-20 years, 10 years or less, those working for more than 20 years encounter statistically significantly more problems when applying an evidence-based approach in clinical practice (p=0.017).

Conclusion:

Younger nurses with higher education and less general work experience tend to have more knowledge and a more positive approach to evidence-based nursing. Problems with an evidence-based approach in clinical practice more often occur in nurses who have worked in the ICU for more than 20 years. Most of the nurses who participated in the study claimed that the lack of time was one of the key problems when practicing evidence-based nursing.

1. INTRODUCTION

In light of the changes in the health care system and the increasing expectations of society, the attitude towards nursing science and the limits of nursing competencies also change, increasing autonomy and advancement of the science of nursing [ 2 ]. Scientists return to the holistic approach to human health, evidence-based clinical solutions and treatment and nursing methods more and more often [ 3 ]. Evidence-based nursing is a fair application of an evidence-based approach in clinical practice and making decisions that ensure the highest quality of patient care [ 4 ]. Evidence-based practice forms a system of clinical solutions to problems and allows nurses to improve continuously and seek only the best professional results [ 5 , 6 ]. Efficient and high-quality care and patient safety are the most important aspects that are ensured by applying evidence-based nursing practice [ 7 ].

ICU Nurses make many clinical decisions in their work. According to the researchers, ICU nurses must make clinical decisions every five seconds [ 8 ]. Thus, it is especially important to base those decisions on scientific evidence. Systematic application of evidence in intensive and critical care has undisputable benefits both to the nurses and to the patients. Nurses get a boost in work satisfaction, gain autonomy and have higher self-confidence in making decisions directly related to their patients' health conditions [ 9 ]. Meanwhile, the patients and their relatives know that all performed manipulations are safe and efficient, as proven by scientific studies, their hospitalization is shorter, mistakes are avoided, and the individual wishes and needs of patients are taken into account [ 10 , 11 ]. Evidence-based nursing practice significantly contributes to avoiding common complications in ICU, such as respiratory tract infection and sepsis [ 12 - 14 ].

When introducing evidence-based nursing in an institution, the preparedness and attitude of employees are very important. Studies analyzing the knowledge, predisposition and skills of nurses and the obstacles they face in implementing advanced nursing practice are an important and integral part of the healthcare service improvement chain [ 15 , 16 ]. Analysis of organizational barriers to applying evidence-based practice is also important [ 17 ]. Courses, simulations and seminars initiated by the workplace notably contribute to nurses' capability to apply evidence-based practice [ 18 ]. However, not all healthcare professionals apply the evidence-based practice. There are various reasons for that. For example, nurses are not interested in scientific innovations; they value work experience based more on traditions due to tight working schedules, willingness to learn, lack of knowledge or other factors [ 19 ]. Timely correction of obstacles to applying evidence-based practice may significantly improve the quality of healthcare services [ 20 ]. Aspects related to evidence-based nursing are not widely researched in Lithuania, unlike in other countries worldwide. This is why a study was carried out to analyze the application of evidence-based practice in intensive and critical care nursing.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was carried out at the ICU of Kaunas Clinics of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences Hospital in 2019. The Center of Bioethics of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences issued a permit to carry out the study after the presentation of the annotation and the research instrument. Targeted sampling was applied. The respondents were the nurses working at the ICU of Kaunas Clinics of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences Hospital. A total of 202 nurses were questioned, with a response rate of 94.3%. Research method: an anonymous questionnaire-based survey. Research object: applying the evidence-based practice in intensive and critical care nursing. A total of 20 questionnaire examples were given to the ICU Nurses before the study. The pilot study results revealed that the questions given in the questionnaire were understandable. The nurses gave no comments, and thus no corrections were made. The research instrument was the questionnaire prepared by McEvoy et al. (2010) [ 1 ]. Cronbach’s alpha of the questionnaire is 0,954. It shows reliability and high internal consistency. The questionnaire was used with the permission of the authors. The questions could be categorized as follows:

1. Demographic questions determined the respondents' age, gender, education, professional experience, work experience at the current institution and work positions.

2. The respondents had to rate evidence-based nursing-related statements and terms from 1 to 5 based on the Likert scale, where 1 meant total disagreement and 5 meant total agreement. Factor analysis helped to sort the 58 statements into 5 areas: importance, obstacles, terminology, practice and self-confidence.

2.1. Statistical Data Analysis

Statistical data analysis was conducted using the SPSS 24.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) software and MC Excel 2016. Descriptive statistics, i.e. , absolute (n) and percentage (%) values, were applied to assess the distribution of the analyzed aspects in the sample. The quantitative data were presented as arithmetic means (m) with standard deviation (SD). The normalcy of the probability distribution of quantitative variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The ANOVA test was used, the Fisher criterion (F) was calculated, and the Bonferroni adjustment was employed to compare the mean values of parametric variables of more than two independent samples. Tables of related aspects were made to assess the connections between aspects. The dependence of aspects was determined using the chi-square (χ2) test, and the pair comparisons were carried out via the z-test and Bonferroni adjustment. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was calculated to assess the strength of the aspect connection satisfying the normalcy assumption (r). In the case of 0<|r|≤0.3, the values were slightly dependent, in the case of 0.3<|r|≤0.8, the values were averagely dependent, and in the case of 0.8<|r|≤1, the values were strongly dependent [ 21 ]. The correlation coefficient was positive when a value increased with another value and negative when a value decreased with another value. Linear regression was used to assess variable dependence when the significance level was p<0.05, the difference of aspects in respondent groups was deemed statistically significant and when p<0.001, it was deemed highly statistically significant.

3.1. Knowledge and Attitude of Icu Nurses in Terms of Evidence-based Nursing

The study included comparing evidence-based nursing application areas based on the respondents' education. Nurses with higher university education claimed to know evidence-based nursing terminology better with a statistical significance than nurses with professional or higher non-university education. The research data also showed that nurses with higher university education had statistically significantly more self-confidence when applying scientific evidence than nurses with professional or higher non-university education. Detailed scores of evidence-based nursing application areas with standard deviations and their comparison are given in Table 1 below.

Linear regression was done to analyze the dependency of evidence-based nursing application areas on the age of the respondents. The results showed that all areas of evidence-based nursing application were statistically significantly dependent on the age of the respondents. Negative β coefficients in all four areas meant that as the age of the respondents increased, their agreement with the statements reflecting the analyzed areas decreased. Older nurses deemed evidence-based nursing to be less important than the younger ones. The terminology knowledge of older respondents was also poorer than that of their younger colleagues. Also, older nurses exhibited less evidence-based nursing-related practice and lower self-confidence (Table 2 ).

The application of evidence-based nursing in the ICU based on the work experience of the respondents was analyzed. The way the nurses with work experience in the ICU assessed evidence-based nursing areas was compared. It was determined that nurses who have worked in the ICU for 10 years or less knew the terminology related to evidence-based nursing statistically significantly better. Also, these nurses statistically significantly more often based their decisions in clinical practice on scientific evidence, compared to nurses who have worked in the ICU for longer, e.g. , 11-20 years or over 20 years. Compared to respondents with over 20 years of work experience in the ICU, nurses with 10 years or less experience had statistically significantly high self-confidence in their knowledge and skills to apply evidence-based practice in nursing. Detailed information on the evidence-based nursing application area scores and standard deviations and their comparison with the work experience of the ICU Nurses are presented in Table 3 .

3.2. Obstacles That ICU Nurses Face When Applying Evidence-based Nursing

The comparison of the obstacles to evidence-based nursing based on the work experience of the nurses in the ICU was carried out. The maximum available score was 35. A statistically significant difference was found: compared to respondents who have worked for 11-20 years, 10 years or less, ICU Nurses with over 20 years of experience faced many obstacles when applying an evidence-based nursing approach. Thus, the longer the nurses work in the ICU, the more obstacles they face when applying an evidence-based nursing approach. Detailed information about the mean values of the scores and their comparison based on the work experience of the respondents in their current workplace is presented in Fig. ( 1 ).

3.3. Peculiarities Of Evidence-based Practice In Intensive And Critical Care Units Of Different Medical Fields

The study analyzed the peculiarities of applying the evidence-based practice in intensive and critical care units of different medical fields. It was determined that the ICU Nurses at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology considered evidence-based nursing to be less important than the Nurses working at the Central Resuscitation Department and the Neurosurgery Department. The difference was statistically significant. The importance of applying evidence in their work was rated highest by the ICU Nurses at the Neurosurgery Department and lowest by the ICU Nurses at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Detailed information about the importance of evidence-based nursing scores by the respondents from various departments and their comparison are presented in Fig. ( 2 ).

The study assessed the self-confidence of nurses when applying the evidence-based nursing approach and compared it among different departments. Self-confidence in evidence-based nursing and making evidence-based clinical decisions revealed statistically significant differences among the ICUs of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department, Cardiology Department, Neurosurgery Department and Central Resuscitation Department. Compared to the nurses in other departments, the ICU Nurses in the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department had lower self-confidence when applying the evidence-based nursing approach (Fig. 3 ).

The study revealed that nurses applying the evidence-based approach faced certain barriers. The obstacles encountered in evidence-based nursing in the ICU of different medical fields were compared. The results revealed that the majority of problems in evidence-based nursing were experienced by the ICU Nurses of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department. The Newborn ICU Nurses encountered the least problems. The difference was deemed statistically significant. Detailed information about the comparison of problems in evidence-based nursing based on the ICU profile is presented in Fig. ( 4 ).

4. DISCUSSION

The study analyzed the implementation of evidence-based nursing by the ICU Nurses at Kaunas Clinics in different aspects. The comparison of evidence-based nursing-related knowledge and attitude, the implementation of the evidence-based approach and self-confidence in its implementation was carried out in terms of the education of the respondents. The results revealed that nurses with higher university education had more knowledge and self-confidence when applying scientific evidence in clinical practice. Bovino et al. presented similar findings: according to their research of 2017, nurses with higher university education (bachelor’s or master’s degree) used evidence in their clinical practice more often and had higher self-confidence in their actions, compared to nurses with a lower level of education [ 22 ]. According to the study of Balakas et al. (2016), the implementation of evidence-based nursing was directly related to the education of the nurses, i.e. , those with master’s or doctor’s degrees showed better results in formulating clinical questions, searching for the most reliable evidence and applying it in clinical practice [ 23 ]. Majid et al. research showed that nurses with higher education and participating in evidence-based training had fewer barriers to applying evidence-based practice [ 19 ]. According to Li et al. , nurses with higher education and positions were more competent in applying evidence-based practice [ 24 ].

The age of the nurses also influenced the application of the evidence-based nursing approach. The study revealed that older nurses faced more obstacles when implementing evidence-based nursing. They had less knowledge and skills related to applying evidence in nursing. According to the study of Warren et al. (2016), younger nurses (22-29 years old) were statistically significantly better prepared to base their actions on evidence in clinical practice. Also, a statistically significantly higher number of younger nurses had a positive attitude toward evidence-based nursing and supported its importance [ 25 ].

Based on the opinion of many researchers, critical thinking is a key skill for ICU Nurses in making urgent clinical decisions, and the latter is integral to evidence-based practice. Ludin (2018) carried out a study with 113 ICU Nurses. It was determined that age and work experience in the ICU greatly affected the nurses' critical thinking and decision-making based on scientific evidence, e.g. , older nurses with higher work experience had statistically significantly better skills in critical thinking and making clinical decisions [ 8 ]. Meanwhile, the results of this study were the opposite: the clinical decisions made by younger nurses with less work experience were more often based on scientific evidence. The research conducted by Alqahtani and co-authors (2022) showed that nurses working in the intensive care unit and emergency department have more knowledge about evidence-based practice than nurses from general units. Their research also concluded that nurses who participated in evidence-based practice courses had better attitudes, knowledge, and leadership skills than nurses who did not participate [ 26 ].

The attitude of the nurses is very important in an evidence-based approach in clinical practice. This study revealed that older nurses deemed evidence-based nursing less important than younger nurses. Nurses with higher education showed a more positive attitude to the application of scientific evidence in nursing: the statement ‘I have had enough of evidence-based nursing’ gained the agreement of 34.2% of nurses with professional education, 11.5% of nurses with higher non-university education, and 14.9% of nurses with higher university education. The difference is statistically significant. Based on the study by Swiss researchers Pereira et al. (2018), nurses with a more positive attitude towards evidence-based nursing usually base their clinical decisions on evidence statistically significantly more often [ 27 ]. The same trend was seen in this study: younger nurses, who, as mentioned previously, deemed evidence-based practice more important than older nurses, based their clinical decisions on scientific evidence statistically significantly more often. 507 nurses participated in a study by Degu and co-authors (2022). 55% of participants had a positive attitude toward evidence-based practice. Research showed that higher-education nurses had more knowledge about evidence-based practice, which led to a more positive attitude to evidence-based practice [ 28 ].

The research data revealed that certain barriers existed when implementing evidence-based nursing. Stavor et al. (2017) indicated that the main obstacles to applying an evidence-based approach in nursing were the avoidance of change, negative attitude and lack of time [ 29 ]. According to a study by Chinese scientists (2020), the lack of knowledge was the main problem in applying evidence-based nursing [ 30 ]. O’Connell et al. (2018) distinguished the two barriers: insufficient knowledge and the lack of cooperation between the nurses and the doctors [ 31 ]. In this study, more than half of the respondents (55.4%) said that the lack of time was one of the largest obstacles to implementing evidence-based nursing in clinical practice. The study also revealed that compared to younger nurses and nurses with less experience in intensive and critical care, older nurses and nurses with more work experience in the ICU encountered more problems when applying the evidence-based approach in nursing. Al-Lenjawi et al. conducted a study with 278 nurses from ICU. The research revealed that the main barriers to applying evidence-based practice are lack of time and support from colleagues, inability to understand statistics, and negative attitude to evidence-based practice [ 32 ]. The mentorship program is one method to encourage nurses to use evidence-based practice. Nurses gained more knowledge and a more positive attitude; there were fewer obstacles to applying evidence-based practice after the mentorship program [ 33 ]. Following Patelarou et al. , evidence-based practice training strongly contributes to more effective healthcare and should be the priority in establishing nursing education programs [ 34 ]. The benefits of evidence-based practice training were emphasized by Ruppel et al. based on the data of their study – nurses with a positive attitude towards evidence-based practice still indicated that training is necessary due to a lack of knowledge [ 35 ].

Thus, critical thinking, a holistic approach to a patient’s health condition, and the ability to work and plan patient care in a multidisciplinary team based on the most trustworthy scientific evidence for each individual case should be the daily duties and responsibilities of each nurse. Studies analyzing the implementation of evidence-based practice are important in attaining the best results in nursing and its practice [ 36 ]. Most of this study's results comply with the studies of foreign researchers. Younger nurses with higher education have better knowledge of applying evidence-based practice in nursing and have a more positive attitude toward it. Nurses with a lower level of education, and in this study, older nurses encounter more problems when applying evidence in clinical practice. The main obstacles to implementing evidence-based nursing are the lack of time, resources and knowledge.

1. The knowledge and attitude of the ICU Nurses related to evidence-based nursing and the implementation of this approach depend on such factors as education, age and work experience. Younger nurses with higher education and less work experience in the ICU tend to have more knowledge of evidence-based nursing and a more positive attitude toward it.

2. Older nurses and nurses whose work experience in the ICU is over 20 years encounter problems when applying scientific evidence in clinical practice more often. Most of the respondents believe the lack of time is one of the major obstacles to implementing evidence-based nursing in clinical practice.

3. The comparison of the peculiarities of employing evidence-based nursing in the ICUs of different medical fields revealed that the ICU Nurses of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department deemed evidence-based nursing to be less important and thus had lower self-confidence and encountered more problems when applying an evidence-based approach in nursing.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The Center of Bioethics of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences issued a permit to carry out the study after the presentation of the annotation and the research instrument (the approval number BEC-ISP(M)-14). Participants submitted informed consent.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used in this research. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were per the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committees and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

Not applicable.

This study was funded by Lithuanian University of Health Sciences Kaunas Clinics Department of Cardiac, Thoracic and Vascular Surgery.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the ICU Nurses of Kaunas Clinics of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences Hospital, who have consented to participate in the study.

Track Your Manuscript

Published contents, about the editor, journal metrics, readership statistics:, total views/downloads: 1,019,472, unique views/downloads: 248,982, about the journal, table of contents.

- INTRODUCTION

- Statistical Data Analysis

- Knowledge and Attitude of Icu Nurses in Terms of Evidence-based Nursing

- Obstacles That ICU Nurses Face When Applying Evidence-based Nursing

- Peculiarities Of Evidence-based Practice In Intensive And Critical Care Units Of Different Medical Fields

Press Release

The open nursing journal, published by bentham open, has been accepted for inclusion in the directory of nursing journals.

The Directory of Nursing Journals is a joint service of Nurse, Author & Editor and the International Academy of Nursing Editors (INANE) . Their primary goal in maintaining this list is to help nurse authors find suitable and reputable journals in which to publish their work. The directory informs readers and consumers of nursing literature about the credibility of literature sources used to guide practice, research, policy and education. The two committees follow the COPE Principles of Transparency and Best Practice in Scholarly Publishing to vet journals.

The Open Nursing Journal is an Open Access online journal, which publishes research articles, reviews, letters and guest edited thematic issues in all areas of nursing. The Journal is an important and reliable source of current information on developments in nursing research and practice. The journal publishes quality papers that are freely accessible to readers worldwide.

For more information about the journal, please visit: https://opennursingjournal.com/index.php

Bentham Open Welcomes Sultan Idris University of Education (UPSI) as Institutional Member

Bentham Open is pleased to welcome Sultan Idris University of Education (UPSI), Malaysia as Institutional Member. The partnership allows the researchers from the university to publish their research under an Open Access license with specified fee discounts. Bentham Open welcomes institutions and organizations from world over to join as Institutional Member and avail a host of benefits for their researchers.

Sultan Idris University of Education (UPSI) was established in 1922 and was known as the first Teacher Training College of Malaya. It is known as one of the oldest universities in Malaysia. UPSI was later upgraded to a full university institution on 1 May, 1997, an upgrade from their previous college status. Their aim to provide exceptional leadership in the field of education continues until today and has produced quality graduates to act as future educators to students in the primary and secondary level.

Bentham Open publishes a number of peer-reviewed, open access journals. These free-to-view online journals cover all major disciplines of science, medicine, technology and social sciences. Bentham Open provides researchers a platform to rapidly publish their research in a good-quality peer-reviewed journal. All peer-reviewed accepted submissions meeting high research and ethical standards are published with free access to all.

Ministry Of Health, Jordan joins Bentham Open as Institutional Member

Bentham Open is pleased to announce an Institutional Member partnership with the Ministry of Health, Jordan . The partnership provides the opportunity to the researchers, from the university, to publish their research under an Open Access license with specified fee concessions. Bentham Open welcomes institutions and organizations from the world over to join as Institutional Member and avail a host of benefits for their researchers.

The first Ministry of Health in Jordan was established in 1950. The Ministry began its duties in 1951, the beginning of the health development boom in Jordan. The first accomplishment was the establishment of six departments in the districts headed by a physician and under the central administration of the Ministry. The Ministry of Health undertakes all health affairs in the Kingdom and its accredited hospitals include AL-Basheer Hospital, Zarqa Governmental Hospital, University of Jordan Hospital, Prince Hashem Military Hospital and Karak Governmental Hospital.

Bentham Open publishes a number of peer-reviewed, open access journals. These free-to-view online journals cover all major disciplines of science, medicine, technology and social sciences. Bentham Open provides researchers a platform to rapidly publish their research in a good-quality peer-reviewed journal. All peer-reviewed, accepted submissions meeting high research and ethical standards are published with free access to all.

Porto University joins Bentham Open as Institutional Member

Bentham Open is pleased to announce an Institutional Member partnership with the Porto University, Faculty of Dental Medicine (FMDUP) . The partnership provides the opportunity to the researchers, from the university, to publish their research under an Open Access license with specified fee concessions. Bentham Open welcomes institutions and organizations from world over to join as Institutional Member and avail a host of benefits for their researchers.

The Porto University was founded in 1911. Porto University create scientific, cultural and artistic knowledge, higher education training strongly anchored in research, the social and economic valorization of knowledge and active participation in the progress of the communities in which it operates.

Join Our Editorial Board

The Open Nursing Journal is an Open Access online journal, which publishes research articles, reviews, letters, case reports and guest-edited single topic issues in all areas of nursing. Bentham Open ensures speedy peer review process and accepted papers are published within 2 weeks of final acceptance.

The Open Nursing Journal is committed to ensuring high quality of research published. We believe that a dedicated and committed team of editors and reviewers make it possible to ensure the quality of the research papers. The overall standing of a journal is in a way, reflective of the quality of its Editor(s) and Editorial Board and its members.

The Open Nursing Journal is seeking energetic and qualified researchers to join its editorial board team as Editorial Board Members or reviewers.

- Experience in nursing with an academic degree.

- At least 20 publication records of articles and /or books related to the field of nursing or in a specific research field.

- Proficiency in English language.

- Offer advice on journals’ policy and scope.

- Submit or solicit at least one article for the journal annually.

- Contribute and/or solicit Guest Edited thematic issues to the journal in a hot area (at least one thematic issue every two years).

- Peer-review of articles for the journal, which are in the area of expertise (2 to 3 times per year).

If you are interested in becoming our Editorial Board member, please submit the following information to [email protected] . We will respond to your inquiry shortly.

- Email address

- City, State, Country

- Name of your institution

- Department or Division

- Website of institution

- Your title or position

- Your highest degree

- Complete list of publications and h-index

- Interested field(s)

Testimonials

"Open access will revolutionize 21 st century knowledge work and accelerate the diffusion of ideas and evidence that support just in time learning and the evolution of thinking in a number of disciplines."

"It is important that students and researchers from all over the world can have easy access to relevant, high-standard and timely scientific information. This is exactly what Open Access Journals provide and this is the reason why I support this endeavor."

"Publishing research articles is the key for future scientific progress. Open Access publishing is therefore of utmost importance for wider dissemination of information, and will help serving the best interest of the scientific community."

"Open access journals are a novel concept in the medical literature. They offer accessible information to a wide variety of individuals, including physicians, medical students, clinical investigators, and the general public. They are an outstanding source of medical and scientific information."

"Open access journals are extremely useful for graduate students, investigators and all other interested persons to read important scientific articles and subscribe scientific journals. Indeed, the research articles span a wide range of area and of high quality. This is specially a must for researchers belonging to institutions with limited library facility and funding to subscribe scientific journals."

"Open access journals represent a major break-through in publishing. They provide easy access to the latest research on a wide variety of issues. Relevant and timely articles are made available in a fraction of the time taken by more conventional publishers. Articles are of uniformly high quality and written by the world's leading authorities."

"Open access journals have transformed the way scientific data is published and disseminated: particularly, whilst ensuring a high quality standard and transparency in the editorial process, they have increased the access to the scientific literature by those researchers that have limited library support or that are working on small budgets."

"Not only do open access journals greatly improve the access to high quality information for scientists in the developing world, it also provides extra exposure for our papers."

"Open Access 'Chemistry' Journals allow the dissemination of knowledge at your finger tips without paying for the scientific content."

"In principle, all scientific journals should have open access, as should be science itself. Open access journals are very helpful for students, researchers and the general public including people from institutions which do not have library or cannot afford to subscribe scientific journals. The articles are high standard and cover a wide area."

"The widest possible diffusion of information is critical for the advancement of science. In this perspective, open access journals are instrumental in fostering researches and achievements."

"Open access journals are very useful for all scientists as they can have quick information in the different fields of science."

"There are many scientists who can not afford the rather expensive subscriptions to scientific journals. Open access journals offer a good alternative for free access to good quality scientific information."

"Open access journals have become a fundamental tool for students, researchers, patients and the general public. Many people from institutions which do not have library or cannot afford to subscribe scientific journals benefit of them on a daily basis. The articles are among the best and cover most scientific areas."

"These journals provide researchers with a platform for rapid, open access scientific communication. The articles are of high quality and broad scope."

"Open access journals are probably one of the most important contributions to promote and diffuse science worldwide."

"Open access journals make up a new and rather revolutionary way to scientific publication. This option opens several quite interesting possibilities to disseminate openly and freely new knowledge and even to facilitate interpersonal communication among scientists."

"Open access journals are freely available online throughout the world, for you to read, download, copy, distribute, and use. The articles published in the open access journals are high quality and cover a wide range of fields."

"Open Access journals offer an innovative and efficient way of publication for academics and professionals in a wide range of disciplines. The papers published are of high quality after rigorous peer review and they are Indexed in: major international databases. I read Open Access journals to keep abreast of the recent development in my field of study."

"It is a modern trend for publishers to establish open access journals. Researchers, faculty members, and students will be greatly benefited by the new journals of Bentham Science Publishers Ltd. in this category."

- Open access

- Published: 25 March 2024

Association between intensive care unit nursing grade and mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock and its cost-effectiveness

- Ki Hong Choi 1 na1 ,

- Danbee Kang 2 , 3 na1 ,

- Jin Lee 2 , 3 ,

- Hyejeong Park 3 ,

- Taek Kyu Park 1 ,

- Joo Myung Lee 1 ,

- Young Bin Song 1 ,

- Joo-Yong Hahn 1 ,

- Seung-Hyuk Choi 1 ,

- Hyeon-Cheol Gwon 1 ,

- Juhee Cho 2 , 3 &

- Jeong Hoon Yang 1 , 4

Critical Care volume 28 , Article number: 99 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1248 Accesses

31 Altmetric

Metrics details

Despite the high workload of cardiac intensive care unit (ICU), there is a paucity of evidence on the association between nurse workforce and mortality in patients with cardiogenic shock (CS). This study aimed to evaluate the prognostic impact of the ICU nursing grade on mortality and cost-effectiveness in CS.

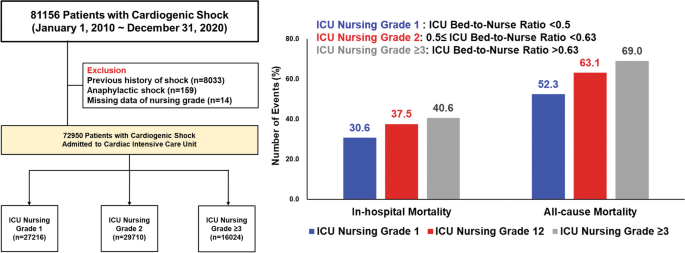

A nationwide analysis was performed using the K-NHIS database. Patients diagnosed with CS and admitted to the ICU at tertiary hospitals were enrolled. ICU nursing grade was defined according to the bed-to-nurse ratio: grade1 (bed-to-nurse ratio < 0.5), grade2 (0.5 ≤ bed-to-nurse ratio < 0.63), and grade3 (0.63 ≤ bed-to-nurse ratio < 0.77) or above. The primary endpoint was in-hospital mortality. Cost-effective analysis was also performed.

Of the 72,950 patients with CS, 27,216 (37.3%) were in ICU nursing grade 1, 29,710 (40.7%) in grade 2, and 16,024 (22.0%) in grade ≥ 3. The adjusted-OR for in-hospital mortality was significantly higher in patients with grade 2 (grade 1 vs. grade 2, 30.6% vs. 37.5%, adjusted-OR 1.14, 95% CI1.09–1.19) and grade ≥ 3 (40.6%) with an adjusted-OR of 1.29 (95% CI 1.23–1.36) than those with grade 1. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of grade1 compared with grade 2 and ≥ 3 was $25,047/year and $42,888/year for hospitalization and $5151/year and $5269/year for 1-year follow-up, suggesting that grade 1 was cost-effective. In subgroup analysis, the beneficial effects of the high-intensity nursing grade on mortality were more prominent in patients who received CPR or multiple vasopressors usage.

Conclusions

For patients with CS, ICU grade 1 with a high-intensity nursing staff was associated with reduced mortality and more cost-effectiveness during hospitalization compared to grade 2 and grade ≥ 3, and its beneficial effects were more pronounced in subjects at high risk of CS.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Cardiogenic shock (CS) is defined as reduced cardiac output together with the impairment of multi-organ blood flow and oxygen delivery to meet metabolic demands [ 1 , 2 ]. Although the widespread adoption of early revascularization strategies and enhancement of evidence-based medical treatments have led to a substantial decrease in mortality for patients with CS over the last 2 decades [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ], refractory CS remains the leading cause of death worldwide. Recently, standardized CS management protocols—including the timely recognition of CS, hemodynamic monitoring, and tailored application of mechanical circulatory support (MCS)—have been emphasized to reduce mortality in patients with CS [ 8 , 9 ]. However, variations in practice patterns for CS management across hospitals endure due to the significant human resources required to apply this careful approach.

Limited nursing staff is one of the challenges in caring for CS because nurses are designated individuals who are the first to detect the deterioration of a patient’s condition through close monitoring, which is the core of critical care [ 10 ]. Studies have found that the nurse staffing ratio is associated with hospitals’ quality of care and safety [ 11 , 12 ]. Overworked nurses would have difficulties providing optimal patient care, leading to adverse outcomes and potentially affecting patients’ survival [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. While extensive research has explored the general implications of nursing workload in critical care settings, there remains a paucity of data specifically focused on the unique challenges and outcomes associated with CS. Previous studies have often centered on broader ICU populations or specific surgical outcomes, such as those following esophageal surgery, which do not adequately capture the acute, life-threatening conditions inherent in CS [ 10 , 16 , 17 ]. This distinction underscores the necessity of our study, which concentrates on this underrepresented group within cardiac ICU settings. Considering the time-sensitive nature of CS, the negative impact of limited nurse staffing resources on the increased risk of death might be more pronounced in cardiac intensive care unit (ICU) settings [ 18 ]. In this regard, the American Heart Association proposes the categorization of cardiac ICU according to specific capabilities, including nurse staffing ratios, ranging from Level I (highest category) to III (lowest category), and care for patients at each level [ 19 ]. Nevertheless, many ICUs do not meet the recommended staffing standards, even in developed countries [ 20 ], which might affect clinical outcomes. Thus, we aimed to evaluate the association between ICU nursing grade and mortality in patients with CS using a national data. Given that nurse staffing accounts for a significant portion of hospital costs, we also conducted a cost-effectiveness analysis to assess the appropriate number of nurses in the cardiac ICU for managing patients with CS.

Study setting and data sources

This is a retrospective cohort study. We obtained data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service (K-NHIS) database. The K-NHIS covers approximately 97% of Koreans, whereas the remaining 3% of Koreans who cannot afford national insurance are covered by the Medical Aid Program [ 21 ]. Therefore, the K-NHIS database represents the entire population of South Korea and contains national records of all covered inpatient and outpatient visits, procedures, and prescriptions. The NHIS data includes modules on insurance eligibility and medical treatment. The insurance eligibility module contains information on age, sex, residential area, and income level. The medical treatment module contains information on treatment, including diseases and prescriptions [ 22 ].

For this study, we included patients aged ≥ 18 years who were diagnosed with cardiogenic shock and admitted to the ICU at tertiary hospitals between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2020 ( N = 81,156). Patients with cardiogenic shock were defined as having been admitted to the ICU with the diagnostic code for cardiogenic shock (International Classification of Disease, 10th revision codes: R57.0) and the presence of at least one of the following conditions: (1) presence of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) procedure code (K-NHIS procedure codes: O1901-O1904) or intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP, K-NHIS procedure codes: O1921, O1922); (2) prescription of vasoactive drugs including dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, and vasopressin for at least 1 day and presence of mechanical ventilation (K-NHIS procedure codes: M5857, M5858, and M5860) or continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT, K-NHIS procedure codes: O7031-O7034, O7051-O7054); or (3) prescription of a vasoactive drug for at least 2 days. Among the participants, we excluded those with anaphylaxis, as epinephrine can be used to treat it (codes: T78.0–T78.4, N = 159), and those with a history of shock ( N = 8033). We also excluded participants with “missing” on the nursing grade ( N = 14). The final sample size included 72,950 patients. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Samsung Medical Center (2021-08-147) and informed consent was exempted because we only accessed de-identified data.

Measurement

ICU nursing grade was defined using codes for ICU nursing-grade admission fees (K-NHIS procedure codes: AJ11–AJ19, AJ21–AJ29, and AJ31–AJ39), which represent the ratio of the number of beds to nurses. ICU nursing grades were categorized into nine (grades 1–9): grade 1 (the best) indicated that the ratio of the number of beds per nurse was less than 0.5, and grade 9 (the worst) indicated that the ratio was ≥ 2.5. For this study, we made three groups according to the ICU nursing grade: grade 1 (bed-to-nurse ratio < 0.5), grade 2 (0.5 ≤ bed-to-nurse ratio < 0.63), and grade 3 (0.63 ≤ bed-to-nurse ratio < 0.77) or above.

In-hospital mortality was defined as the receipt of an insurance death code at index admission. All-cause mortality was defined as the receipt of an insurance death code during the follow-up period (until December 31, 2020).

Information on the underlying disease, interventions, demographics, and hospital characteristics was based on claim codes. We used the Korean Classification of Disease, sixth edition, which is a modified version of the International Classification of Disease, 10th revision adapted for use in the Korean health system [ 23 ]. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) at admission was defined as the presence of a CPR procedure code (K-NHIS procedure codes: M5871, M5873, M5874, M5875, M5876, and M5877) in the emergency room prior to admission for the patients admitted from the emergency room. Interventions for critical care included the use of mechanical ventilation for more than 3 h (K-NHIS procedure codes: M5857, M5858, and M5860), ECMO (O1901–O1904), hemodialysis including CRRT (O7051-O7054), hemodialysis (O7020), and peritoneal dialysis (O7062). We identified the use of vasopressor drugs such as dobutamine (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical [ATC] code: C01CA07), dopamine (ATC code: C01CA04), epinephrine (ATC code: C01CA24), and norepinephrine (ATC code: C01CA03) for more than 2 days using Korean drugs and anatomical therapeutic chemical codes. We calculated hospital volumes using the number of patients per year. We also collected the total medical costs during the index hospitalization.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square and Student’s t-tests were used to compare categorical and continuous variables, respectively. The primary outcome of this study was in-hospital mortality. We calculated odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for in-hospital mortality using logistic regression. We adjusted for age, sex, cause of admission, comorbidities, use of multiple vasopressors, mechanical ventilation, IABP, ECMO, CRRT, and hospital volume to account for potential confounding factors. To account for potential non-linear associations between continuous covariates and outcomes, age and hospital volume included in the model using restricted cubic splines with 4 knots (solid curve). According to the guideline for improving causal inference, covariables were selected a priori based on their possible associations with ICU nursing grade and outcomes [ 24 ]. In addition, we explored the association between the ratio of the number of beds to nurses and in-hospital mortality in pre-specified, clinically relevant subgroups defined by age, sex, CPR at admission, multiple vasopressor use, mechanical ventilation, and ECMO. For all-cause mortality, patients were followed from the date of admission until the date of death or December 31, 2020 (end of the study), whichever occurred first. Cumulative all-cause mortality during the entire study period was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and log-rank tests were used to evaluate the differences between the groups. We calculated the hazard ratios (HRs) with a 95% CI for all-cause mortality using a Cox regression model. We examined the proportional hazard assumption using plots of the log–log survival function and Schoenfeld residuals.

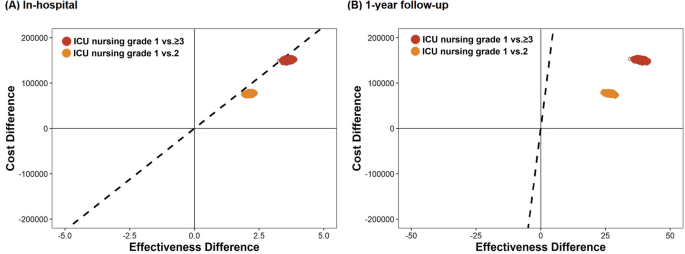

A cost-effectiveness analysis was conducted followed the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards guidelines [ 25 ]. A time horizon of in-hospital (from admission to discharge) and 1 year was applied. We estimated the length of survival from the time of admission to all-cause mortality and calculated the daily medical costs based on index hospitalization. In the analysis, the cost was presented in US dollars (1200 Korean Won [₩] = 1 dollar [$]). The cost-effectiveness of nursing grade 1 was expressed as the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), defined as the difference in the in-hospitalization costs divided by the difference in length of survivor within hospitalization and 1 year after discharge. To determine the optimal strategies, we utilized a willingness to pay threshold of $45,000, which is considered severe for ill conditions. We considered interventions with ICER values lower than the 1 × willingness to pay threshold to be cost-effective. A strategy that was both less costly and more effective than another was defined as dominant [ 26 ]. We also performed a probabilistic sensitivity analysis. The incremental cost-effectiveness plane for differences in costs and quality-adjusted life years and ICER was obtained using the bootstrap technique with the percentile method with 25,000 replications. Planned subgroup analyses of the cost-effectiveness of grade 1 of the ratio of the number of beds to nurses were performed according to CPR at admission, use of multiple vasopressors, mechanical ventilation, and ECMO.

All p values were two-sided, and a p value < 0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed using SAS® (SAS Institute Inc., USA) and R 4.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Patient characteristics

The participants’ mean (standard deviation) age was 69.4 (14.4) years, and 60.1% of them were male (Table 1 ). Of these, 33.2% visited hospitals due to acute myocardial infarction-related CS, and the remaining 66.8% visited due to non-acute myocardial infarction-related CS. Out of these patients, 63.4% required mechanical ventilation, and 21.3% and 8.0% of patients required CRRT and ECMO, respectively. In terms of nursing grading, the participants were divided as 37.3% ( N = 27,216) in ICU grade 1, 40.7% ( N = 29,710) in ICU grade 2, and 22.0% ( N = 16,024) in ICU grade ≥ 3. In comparison to patients in ICU grade 2 or grade ≥ 3, patients in ICU grade 1 had higher general risk factors, such as Charlson’s comorbidity index, history of congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and history of cancer. In addition, patients in ICU grade 1 were more likely to require ECMO (9.6% vs. 7.3% vs. 6.8%; p < 0.01) and CRRT (22.6% vs. 22.0% vs. 17.7%; p < 0.01; Table 1 ).

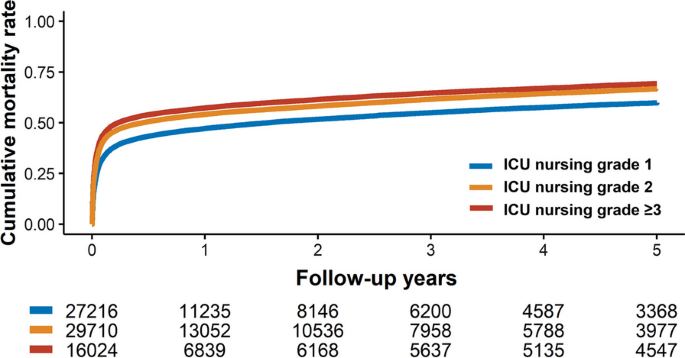

In-hospital and follow-up outcomes

The in-hospital mortality rates for patients in ICU grade 1, ICU grade 2, and ICU grade ≥ 3 groups were 30.6%, 37.5%, and 40.6%, respectively. The fully-adjusted ORs for in-hospital mortality in patients with grade 2 and grade ≥ 3, compared to those with grade 1, were 1.14 (95% CI 1.09–1.19) and 1.29 (95% CI1.23–1.36), respectively (Table 2 ). During the median 0.5 years of follow-up (interquartile range 0.03–3.41, maximum 11 years), 44,046 participants died. The mortality rate per 100 person-years was 52.3, 63.1 and 69.0 in ICU grades 1, 2, and ≥ 3 (Fig. 1 , log-rank p < 0.01). Crude HR (95% CI) for all-cause mortality was 1.23 and 1.34 when comparing grades 2 and ≥ 3 to grade 1 (Table 2 ). This association remained significant after adjusting for confounding factors (grade 1 vs. 2, HR 1.10, 95% CI 1.07–1.13; grade 1 vs. grade ≥ 3, HR 1.21, 95% CI 1.18–1.24).

Comparison of all-cause mortality according to ICU nursing grade in patients with CS. Kaplan–Meier curves are shown for comparing 5-year follow-up, all-cause mortality among patients treated by ICU nursing grade 1 (blue line), grade 2 (orange line), or grade ≥ 3 (red line) hospitals. CS cardiogenic shock, ICU intensive care unit

In the subgroup analysis, increased in-hospital mortality in patients with ICU grade 2 compared with those with ICU grade 1 was more prominent in patients who received CPR on admission ( P -for-interaction < 0.01) than in those who did not receive it. In ICU grade ≥ 3 versus ICU grade 1, the effect of increased mortality was stronger in patients who received CPR on admission ( P -for-interaction < 0.01) and multiple vasopressors ( P -for-interaction < 0.01) than in those who did not receive CPR or received a single vasopressor (Additional file 1 : Fig. S1).

- Cost-effectiveness

The estimated total cumulative cost per patient for grade 1 was $1365—approximately $199 higher than in grade 2 and $423 higher than in grade ≥ 3. Comparing grade 1 with grade 2 and 3, we found that grade 1 patients lived for 2.9 and 3.6 days longer, respectively, and they lived an additional 14.1 and 29.3 days longer at the 1-year follow-up, respectively (Table 3 and Additional file 1 : Table S1). The ICER comparing grade 2 and grade ≥ 3 was calculated as 25,047$/year and 42,888$/year for hospitalization and 5151$/year and 5269$/year for a 1-year follow-up period, respectively (Table 3 ). Grade 1 had higher cost-effectiveness across all analyzed subgroups, especially in patients who received CPR at admission, mechanical ventilation, and ECMO, than grades 2 and ≥ 3 (Table 3 ). Probabilistic sensitivity analysis showed that the probability of cost-effectiveness in grade 1 compared to grade 2 and in grade 1 compared to grade ≥ 3 was 100% and 99.9% in-hospital, and 100% and 100% at the 1-year follow-up, respectively (Fig. 2 ).

Incremental cost-effectiveness plane for ICU nursing grade 1 compared with grade 2 and grade ≥ 3 for costs until discharge and 1 year after admission. Replications of the incremental cost-effectiveness of ICU grade 1 compared with ICU grade 2 (orange dot) and ICU grade ≥ 3 (red dot) are shown. The incremental cost-effectiveness plane presented the effectiveness of admission to the grade 1 hospital for cardiogenic shock treatment, as compared to grades 2 and 3, on the difference in length of survival (effectiveness) and accompanying healthcare-related costs (dollars) during hospitalization and 1 year of follow-up. Each of the 25,000 points represents the result of one bootstrap replication. The difference in cumulative costs is displayed on the vertical axis, and the difference in the length of survival is displayed on the horizontal axis. The average ICER is indicated by a red dot. Willingness-to-pay thresholds of $45,000 per 1-year life gain added (dashed line) are indicated in the plane. ICU intensive care unit

This large, nationwide cohort study suggests that a lower bed-to-nurse ratio is associated with decreased in-hospital mortality in patients with CS (Graphical Abstract). Furthermore, ICU nursing grade 1 was more cost-effective than grades 2 and ≥ 3 during hospitalization and 1-year follow-up. The association between the bed-to-nurse ratio and mortality benefit was more pronounced in patients who underwent CPR at admission and required multiple vasopressors, indicating Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) shock classification stage D or E. Finally, admission to an ICU grade 1 hospital seems to be more cost-effective when dealing with situations that require advanced resources and careful management, such as mechanical ventilation, ECMO, and CPR.

In the ICU setting, an increased nurse workload was associated with higher mortality rates [ 10 , 27 , 28 ]. In addition, the shortage of nursing staff can lead to problems of insufficient supervision, and it may inhibit the early recognition of patients’ changes.[ 29 ]. In this regard, the American Nurses Association recommends that critical care units have a patient-to-nurse ratio of 1:2 or less [ 30 ]. However, data comparing the clinical outcomes based on the ICU nursing grade for patients with CS, which is a life-threatening, acute condition, are limited. Theoretically, nursing staff resources are more critical in the setting of patients in time-sensitive situations such as shock and arrest than in the setting of elective care for monitoring high-risk patients [ 12 ]. Furthermore, CS is a complex condition that requires not only treatment of the heart but also prevention and treatment of the development of multiple organ dysfunction, along with the use of advanced mechanical circulatory devices [ 31 ]. Considering the potential impact of prolonged shock leading to systemic inflammatory response syndrome and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome on mortality rates [ 32 , 33 ], enough nursing care to detect the early identification of potential complications is required to improve outcomes through continuous, careful monitoring in patients with CS. In particular, with the transformation from a conventional coronary care unit to a cardiac ICU, the focus on nursing workload and a multidisciplinary shock team approach in the setting of CS has been increasing [ 19 , 34 ]. In fact, nurse-to-patient ratio is an important factor when evaluating cardiac ICU quality, and a level 1 cardiac ICU is defined as a nurse-to-patient ratio of 1:1 or 1:2 [ 19 ]. In line with this background, we found that hospitals with ICU nursing grade 2 (0.5 ≤ bed-to-nurse ratio < 0.63) and grade 3 (0.63 ≤ bed-to-nurse ratio < 0.77) or above showed significantly higher risks of mortality compared to hospitals with ICU nursing grade 1 (bed-to nurse ratio < 0.5), when treating patients with CS.

In our subgroup analysis, the beneficial effects of lower bed-to-nurse ratios on mortality were more prominent in patients classified as having an advanced form of CS requiring CPR at admission or multiple types of vasopressors to maintain tissue perfusion. Recently, the SCAI proposed a new 5-stage CS classification to provide a simple schema that would allow clear communication regarding patient status and allow clinical trials to appropriately differentiate patient subsets [ 35 ]. Several observational studies have clearly demonstrated that the SCAI shock stage is associated with robust mortality risk stratification in patients with CS [ 36 , 37 , 38 ]. Especially in the advanced stages of CS, such as SCAI D (multiple vasopressor use) or E (undergoing CPR at admission), patients might be highly susceptible to minor medical errors. In addition, inadequate physician collaboration, poor nurse–patient communication, increased medical errors, and nosocomial infections may be possible causes of the association between high nurse workload and increased mortality [ 27 , 39 ]. Taken together, close monitoring, timely interventions, and efforts to reduce medical errors should be paid to rescue patients, particularly in the advanced form of CS, in accordance with the current findings.

The current study also showed that ICU grade 1 was more cost-effective than ICU grades 2 and 3 during hospitalization and at the 1-year follow-up. In the simplest scenario, increasing registered nurse staffing by 1 h per patient per day in the United Kingdom would cost $77,957 per life saved (2021 US dollar equivalent). Given a per capita gross domestic product of $47,334, this would be cost-effective if each life saved gained 1.6 quality-adjusted life years. Although the total cumulative cost per patient in grade 1 was higher than those in grades 2 and 3, it was still within the acceptable cost range, considering the significant improvement in life gain. The additional costs incurred in Grade 1 may have been offset by the benefits of extended survival and improved patient outcomes. In particular, patients who underwent invasive treatment with additional resources, such as CPR, mechanical ventilation, and ECMO, were more cost-effective in ICU grade 1 compared to the ICU grade 2 and grade ≥ 3 than those who did not. Considering the high cost of invasive procedures, it is essential to recognize that without adequate nurse staffing, expensive medical equipment may not yield the desired outcomes. Therefore, ensuring sufficient nursing resources is crucial to optimize the effectiveness of costly medical interventions in the care of patients with CS. Our findings have implications for clinical management and policymaking. Although we are aware that a high workload is associated with poor clinical outcomes [ 40 ], we could not assign a nurse to a patient according to the individual patient’s workload score before measuring individual patients. However, we could assume that when duties are assigned, patients require a high nurse staffing ratio and have priority in nurse allocation, which could be a cost-effective strategy for the management of patients with advanced CS.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, the identification of CS is based on ICD-10 codes reported by hospitals. Given that the recent Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry reported that only 50% of CS patients receiving ECMO support had an ICD code of R57.0 [ 41 ], there was a possibility that many patients with CS were missed in the current study. However, as recommended by the Shock Academic Research Consortium [ 42 ], we applied a strict additional definition of signs of organ failure, including mechanical ventilation, CRRT, IABP, or ECMO, and use of vasopressors for at least 2 days, to compensate for code-based sampling. Secondly, due to the nature of the dataset, we were not able to include certain key variables that could significantly influence the interpretation of our results. In particular, our dataset lacked direct measures of disease severity, such as multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, or Sequential Organ Failure Assessment scores, which are crucial for a comprehensive assessment of a patient’s clinical status. However, we attempted to adjust for severity of illness using the Shock Academic Research Consortium’s use of multiple vasopressors, CPR on admission, use of mechanical ventilation, IABP, ECMO, and CRRT as signs of organ failure. In addition, our dataset did not include information on the goals of care for individual patients, which can strongly influence treatment decisions and outcomes. Goals of care, which include critical decisions such as whether patients would accept CPR or intubation, play a key role in determining the intensity and type of care provided. Future studies incorporating these critical parameters would be necessary to better understand and improve patient care in cardiogenic shock scenarios. Thirdly, the measurement of nursing staffing levels was based on the number of hospital beds per nurse rather than patients per nurse. This approach was necessitated by the structure of our claims data, where nursing grades were determined based on the number of hospital beds at the time of data collection. Finally, our dataset lacked important information that could further influence patient outcomes, such as the scheduling of nursing shifts (morning, evening, or night) and the specific qualifications of nursing staff (e.g., nurse practitioner, registered nurse, licensed practical nurse, or certified nurse assistant).

ICU grade 1 with a high-intensity nurse staffing was associated with reduced mortality and was more cost-effective during hospitalization and 1-year follow-up, compared to hospitals with ICU grade 2 and ≥ 3 in patients with CS. The beneficial effects of lower bed-to-nurse ratios were more pronounced in patients with an advanced form of CS who received CPR and multiple vasopressors.

Availability of data and materials

We used the claim data provided by the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) database. Data can only be accessed by visiting the NHIS datacenter, after approval from data access committee of NHIS. Those who want to access data set of this study should contact corresponding authors ([email protected]), who will help with the process of contacting the NHIS.

Abbreviations

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Continuous renal replacement therapy

- Cardiogenic shock

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- Intensive care unit

Korean National Health Insurance Service

Mechanical circulatory support

Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions