Essay on What is Religion for Students and Children

500+ words essay on what is religion.

Religion refers to a belief in a divine entity or deity. Moreover, religion is about the presence of God who is controlling the entire world. Different people have different beliefs. And due to this belief, many different cultures exist.

Further, there are a series of rituals performed by each religion. This is done to please Gods of their particular religion. Religion creates an emotional factor in our country. The Constitution of our country is secular . This means that we have the freedom of following any religion. As our country is the most diverse in religions, religion has two main sub broad categories:

Monotheistic Religion

Monotheistic religions believe in the existence of one God. Some of the monotheistic religions are:

Islam: The people who follow are Muslims . Moreover, Islam means to ‘ surrender’ and the people who follow this religion surrender themselves to ‘Allah’.

Furthermore, the holy book of Islam is ‘ QURAN’, Muslims believe that Allah revealed this book to Muhammad. Muhammad was the last prophet. Above all, Islam has the second most popular religion in the entire world. The most important festivals in this religion are Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha.

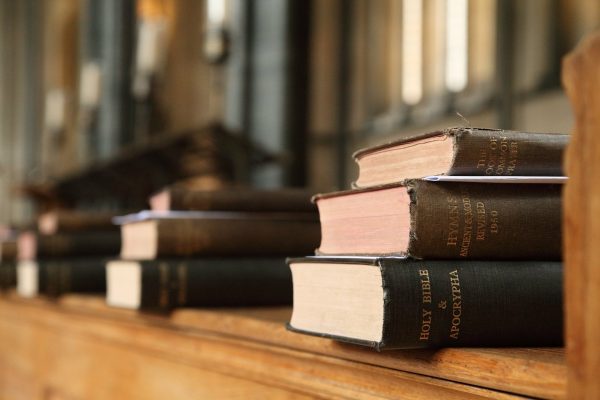

Christianity: Christian also believes in the existence of only one God. Moreover, the Christians believe that God sent his only Jesus Christ for our Salvation. The Holy book of Christians is the Bible .

Furthermore, the bible is subdivided into the Old Testament and the New Testament. Most Importantly, Jesus Christ died on the cross to free us from our sins. The people celebrate Easter on the third day. Because Jesus Christ resurrected on the third day of his death.

However, the celebration of Christmas signifies the birth of our Lord Jesus Christ. Above all Christianity has the most following in the entire world.

Judaism: Judaism also believes in the existence of one God. Who revealed himself to Abraham, Moses and the Hebrew prophets. Furthermore, Abraham is the father of the Jewish Faith. Most Noteworthy the holy book of the Jewish people is Torah.

Above all, some of the festivals that Jewish celebrate are Passover, Rosh Hashanah – Jewish New Year, Yom Kippur – the Day of Atonement, Hanukkah, etc.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Polytheistic Religion

Polytheistic religions are those that believe in the worship of many gods. One of the most believed polytheistic religion is:

Hinduism: Hinduism has the most popularity in India and South-east Asian sub-continent. Moreover, Hindus believe that our rewards in the present life are the result of our deeds in previous lives. This signifies their belief in Karma. Above all the holy book of Hindus is ‘Geeta’. Also, Hindus celebrate many festivals. Some of the important ones are Holi-The festival of colors and Diwali- the festival of lights.

Last, there is one religion that is neither monotheistic nor polytheistic.

Buddhism: Buddhism religion followers do not believe in the existence of God. However, that does not mean that they are an atheist. Moreover, Buddhism believes that God is not at all the one who controls the masses. Also, Buddhism is much different from many other religions. Above all, Gautam Buddha founded Buddhism.

Some FAQs for You

Q1. How many types of religions are there in the entire world?

A1. There are two types of religion in the entire world. And they are Monotheistic religions and Polytheistic religions.

Q2. What is a Polytheistic religion? Give an example

A2. Polytheistic religion area those that follow and worship any Gods. Hinduism is one of the examples of polytheistic religion. Hindus believe in almost 330 million Gods. Furthermore, they have great faith in all and perform many rituals to please them.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Best Bible Resources For Christians

Bible Facts

- Christian Life

- Read the Bible

Home > Bible Facts > Writing a Perfect Religion Essay for College Students

Writing a Perfect Religion Essay for College Students

Modified: January 9, 2024

Written by: Sven Eggers

Wonder how to write an amazing religion essay for collage? Here's a guideline that covers the basis of what to write and how to write.

- bible facts

- religion essays

(Many of the links in this article redirect to a specific reviewed product. Your purchase of these products through affiliate links helps to generate commission for Christian.net, at no extra cost. Learn more )

Are you a college student wondering how to write the perfect essay on religion? If yes, read on and find all that you need to know about writing a religion essay. This article will cover the basics and all you need to know about writing an excellent essay piece on religion.

What is a Religion Essay

Image by Thought Catalog on Unsplash

Well, religion essays are a kind of paper that relates to religion, belief, and faith.

In college, many students will be required to write a few essays on religion. Students typically struggle with writing assignments of this nature since they haven’t learned how to write professionally. After all, religion is a highly personal subject, and objective discussions about religion can be particularly difficult and generally mind-boggling.

As a result of this, many students prefer outsourcing their writing assignments on religion to a custom essay writing service like Edubirdie. On this “write an essay for me” platform, there are plenty of professional writers for you to choose from with guaranteed transparency on their profiles and reviews. After reviewing, you can simply choose a writer and you will have your essay delivered in no time.

On the other hand, some students prefer completing such religious essays themselves to improve their writing. If you fall under this category we’ve put together some tips for you. for you to ace your religion essay.

Read more : Christian Blogs To Follow Before Writing a Religious Essay

Tip 1: Choosing a Topic for a Religion Essay

Image by Keenan Beasley on Unsplash

Consider a topic that interests you, one that piques your curiosity . Though it’s said that curiosity kills the cat, it’s a much-needed drive in essays, especially ones that deal with theology and mind-boggling ideas. H aving an interest as your personal pedestal throughout is effective for your research and writing.

A contentious issue would make a fantastic topic for a religion essay because it means it’s a topic of interest to people and it gives room and framework to your arguments. An example can be whether hell is a truth or a myth . You can decide to look into where a particular religious idea came from and employ background information and opposing points of view to present your argument. Whatever the topic, always use the most reliable sources you can to back up your claims.

Next, contemplate what your stance is towards the issue and start to build your case around it. Are you for it or against it? Should this topic even be contentious in the first place? Are there other points that should be contended besides what has already been debated? Usually, a great religious essay identifies the issue and has tight arguments to support the thesis. But, an amazing essay is one that brings in a fresh perspective that’s been rarely discussed in class. So, work around that.

This step is usually the toughest, but once you’ve passed through it, the rest of the work is a breeze.

Tip 2: How to Write an Introduction for a Religion Essay

Image by Patrick Perkins on Unsplash

Prepare your notes and an overview of your case before beginning to write the introduction. In contrast to creative writing , the reader expects your thesis statement and facts up front in an essay. Because of this, seasoned writers advise pupils to read more books and develop their own points of view. But occasionally it can be advantageous to grab an idea from someone who wrote it before you. It’s catchy and demonstrates your familiarity with the subject. The reader should have a clear understanding of what to anticipate from the article from the beginning.

How can you create a strong essay introduction? The components of a strong introduction are numerous such as some background information, a thesis statement, a purpose statement, and a summary of what’s to be covered. Essentially, your introduction is your first impression and a blueprint of what the entire essay will be.

The topic and focus of the essay, as well as a few other important concepts, should be covered in the first paragraph. Along with the thesis, it should also give background details and the context of the argument. It should also describe the essay’s structure, which is outlined in the last paragraph. The importance of the introduction increases as the essay gets longer. Even though it may appear tedious, just like any first impression, the introduction is an important component of any paper.

Tip 3: How to Write the Body of a Religion Essay

Image by green chameleon on Unsplash

Introduce the basic tenets and principles of the religion you’re addressing in the major body of your essay. Then, you should investigate the crucial components of the tradition. What are its core ideals and beliefs? What role does it play in society? How is it relevant in our current world? Textual support must be provided because this is an excellent approach to capturing your readers’ interest.

The promise you made in your introduction should be fulfilled in the body of your essay. Make sure to add new proof to the main argument of each paragraph in the body of your essay. Each paragraph should be concluded with a sentence that emphasizes the importance of the argument and connects it to the following one.

Tip 4: How to Write the Conclusion Section for a Religion Essay

Image by Christin Hume on Unsplash

Your conclusion is a paragraph (or two) of concluding remarks that demonstrate the points you’ve made are still true and worth considering . Think of it as a final impression you make on the readers, you’d want to make yourself memorable Additionally, it should demonstrate that the arguments you made in the essay’s main body are supported by relevant evidence.

A great conclusion is also one that highlights the significance of your points and directs readers toward the best course of action for the future. This shows that you aren’t just someone who debates but someone who is also willing to try and better the situation. Keep in mind that your final chance to convince or impress your audience is the conclusion.

Read more : Teaching Religious Symbolism in Modern Literature

Tip 5: Find Proofreaders

Image by Joel Muniz on Unsplash

If I’d learned anything through my years of college essays, it’s to get people to proofread your essay. They are your safety nets. I’d usually find a coursemate or someone from my class to proofread. They are valuable second pairs of eyes to help you spot grammar mistakes but also in concepts that you may have applied. Next, find a friend that’s not from your course or class because they are an accurate assessment of how clear and cohesive your essay is. If they can understand what you’re writing, you can be sure that half the battle is already won.

Was this page helpful?

How The Synoptic Gospels View The Kingdom Of God Commentary

What Is A Radiating Chapel

About How Many Years Of Church History Does The Acts Of The Apostles Cover?

How May Apostles Were There

How Long Was John The Baptist In The Wilderness

Latest articles.

Who To Invite To First Communion

Written By: Sven Eggers

How Did The Concordat Resolve The Crisis Over Catholicism In France

Where And When Was Canterbury Cathedral Built

What Were The State And Church Institutions Unified Under In Colonial Massachusetts?

How Big Is The St. Peter's Basilica

Related post.

By: J.C • Christian Resources

By: J.C • Christian Life

By: Liming • Christian Resources

By: Cherin • Christian Resources

By: Maricris Navales • Christian Resources

By: Sophia • Christian Resources

By: Alyssa Castillo • Christian Life

Please accept our Privacy Policy.

CHRISTIAN.NET uses cookies to improve your experience and to show you personalized ads. Please review our privacy policy by clicking here .

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

- https://christian.net/theology-and-spirituality/writing-a-perfect-religion-essay-for-college-students/

Home — Essay Samples — Religion — Christian Worldview — Christianity Beliefs and Practices: Exploring the Christian Worldview

Christianity Beliefs and Practices: Exploring The Christian Worldview

- Categories: Christian Worldview Religious Beliefs

About this sample

Words: 600 |

Updated: 29 March, 2024

Words: 600 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

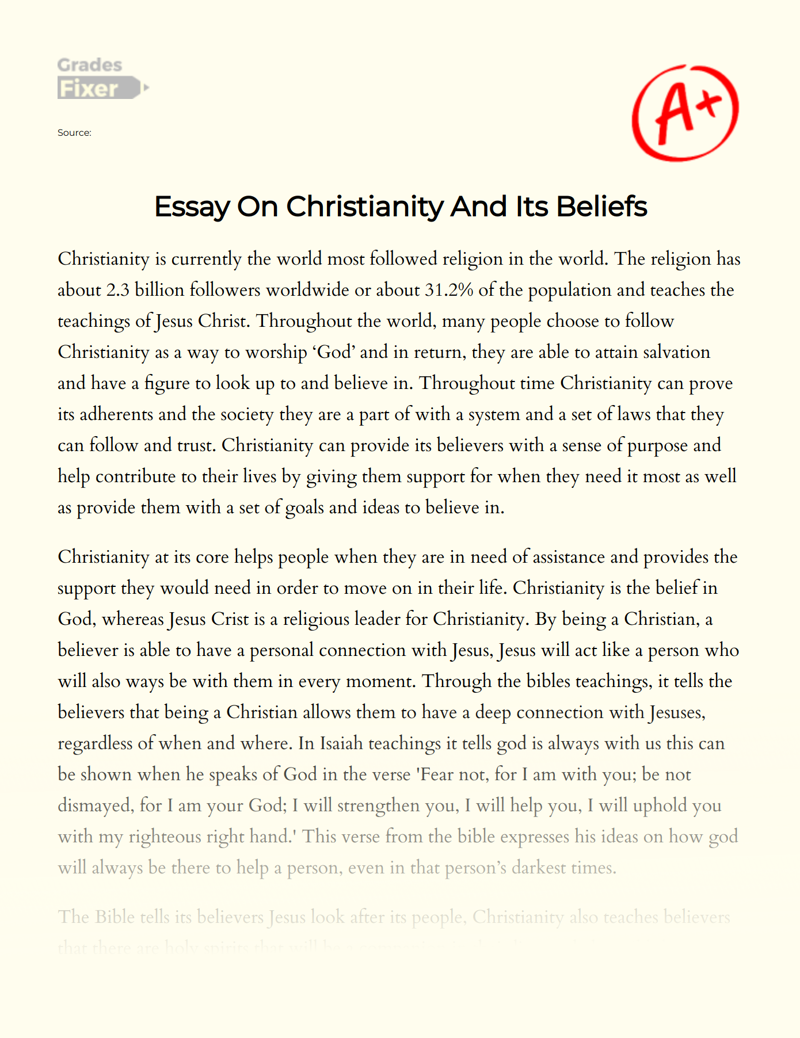

Support and Solace in Christianity

Should follow an “upside down” triangle format, meaning, the writer should start off broad and introduce the text and author or topic being discussed, and then get more specific to the thesis statement.

Provides a foundational overview, outlining the historical context and introducing key information that will be further explored in the essay, setting the stage for the argument to follow.

Cornerstone of the essay, presenting the central argument that will be elaborated upon and supported with evidence and analysis throughout the rest of the paper.

The topic sentence serves as the main point or focus of a paragraph in an essay, summarizing the key idea that will be discussed in that paragraph.

The body of each paragraph builds an argument in support of the topic sentence, citing information from sources as evidence.

After each piece of evidence is provided, the author should explain HOW and WHY the evidence supports the claim.

Should follow a right side up triangle format, meaning, specifics should be mentioned first such as restating the thesis, and then get more broad about the topic at hand. Lastly, leave the reader with something to think about and ponder once they are done reading.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Religion

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1515 words

7 pages / 3271 words

3 pages / 1271 words

4 pages / 1749 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Christian Worldview

The Rule of St. Benedict, written by St. Benedict of Nursia in the 6th century, is a foundational text for Western monasticism. This document outlines the principles and practices that govern the lives of monks living in a [...]

A Christian worldview is a framework of beliefs and values that shapes an individual's perception of the world and guides their decision-making process. It is rooted in the teachings of Jesus Christ and the Bible, and it [...]

A Book of Showings, also known as Showings or Revelations of Divine Love, is a theological work written by Julian of Norwich, an English anchoress believed to have lived from 1342 to around 1416. The text is a significant piece [...]

Christianity is the world's largest religion, with over 2.3 billion followers worldwide. It is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ, who is considered the Son of God and the savior of humanity. [...]

John Bunyan’s work The Pilgrim’s Progress, is one of the most renowned Christian books to read, but it is not in fact within Christian rules, according to the Bible, thus unveiling a logical fallacy. With careful analysis of [...]

Since birth, people are taught to live a certain way and be a certain someone by those who raise them. Many individuals are born into Christianity, attending church since birth, going to church camps and living the lifestyle of [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

The Concept of Religion

It is common today to take the concept religion as a taxon for sets of social practices, a category-concept whose paradigmatic examples are the so-called “world” religions of Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Daoism. [ 1 ] Perhaps equally paradigmatic, though somewhat trickier to label, are forms of life that have not been given a name, either by practitioners or by observers, but are common to a geographical area or a group of people—for example, the religion of China or that of ancient Rome, the religion of the Yoruba or that of the Cherokee. In short, the concept is today used for a genus of social formations that includes several members, a type of which there are many tokens.

The concept religion did not originally refer to a social genus, however. Its earliest references were not to social kinds and, over time, the extension of the concept has evolved in different directions, to the point that it threatens incoherence. As Paul Griffiths notes, listening to the discussions about the concept religion

rapidly suggests the conclusion that hardly anyone has any idea what they are talking about—or, perhaps more accurately, that there are so many different ideas in play about what religion is that conversations in which the term figures significantly make the difficulties in communication at the Tower of Babel seem minor and easily dealt with. These difficulties are apparent, too, in the academic study of religion, and they go far toward an explanation of why the discipline has no coherent or widely shared understanding of its central topic. (2000: 30)

This entry therefore provides a brief history of the how the semantic range of religion has grown and shifted over the years, and then considers two philosophical issues that arise for the contested concept, issues that are likely to arise for other abstract concepts used to sort cultural types (such as “literature”, “democracy”, or “culture” itself). First, the disparate variety of practices now said to fall within this category raises a question of whether one can understand this social taxon in terms of necessary and sufficient properties or whether instead one should instead treat it as a family resemblance concept. Here, the question is whether the concept religion can be said to have an essence. Second, the recognition that the concept has shifted its meanings, that it arose at a particular time and place but was unknown elsewhere, and that it has so often been used to denigrate certain cultures, raises the question whether the concept corresponds to any kind of entity in the world at all or whether, instead, it is simply a rhetorical device that should be retired. This entry therefore considers the rise of critical and skeptical analyses of the concept, including those that argue that the term refers to nothing.

1. A History of the Concept

2.1 monothetic approaches, 2.2 polythetic approaches, 3. reflexivity, reference, and skepticism, other internet resources, related entries.

The concept religion did not originally refer to a social genus or cultural type. It was adapted from the Latin term religio , a term roughly equivalent to “scrupulousness”. Religio also approximates “conscientiousness”, “devotedness”, or “felt obligation”, since religio was an effect of taboos, promises, curses, or transgressions, even when these were unrelated to the gods. In western antiquity, and likely in many or most cultures, there was a recognition that some people worshipped different gods with commitments that were incompatible with each other and that these people constituted social groups that could be rivals. In that context, one sometimes sees the use of nobis religio to mean “our way of worship”. Nevertheless, religio had a range of senses and so Augustine could consider but reject it as the right abstract term for “how one worships God” because the Latin term (like the Latin terms for “cult” and “service”) was used for the observance of duties in both one’s divine and one’s human relationships (Augustine City of God [1968: Book X, Chapter 1, 251–253]). In the Middle Ages, as Christians developed monastic orders in which one took vows to live under a specific rule, they called such an order religio (and religiones for the plural), though the term continued to be used, as it had been in antiquity, in adjective form to describe those who were devout and in noun form to refer to worship (Biller 1985: 358; Nongbri 2013: ch. 2).

The most significant shift in the history of the concept is when people began to use religion as a genus of which Christian and non-Christian groups were species. One sees a clear example of this use in the writings of Edward Herbert (1583–1648). As the post-Reformation Christian community fractured into literal warring camps, Herbert sought to remind the different protesting groups of what they nevertheless had in common. Herbert identified five “articles” or “elements” that he proposed were found in every religion, which he called the Common Notions, namely: the beliefs that

- there is a supreme deity, [ 2 ]

- this deity should be worshipped,

- the most important part of religious practice is the cultivation of virtue,

- one should seek repentance for wrong-doing, and

- one is rewarded or punished in this life and the next.

Ignoring rituals and group membership, this proposal takes an idealized Protestant monotheism as the model of religion as such. Herbert was aware of peoples who worshipped something other than a single supreme deity. He noted that ancient Egyptians, for instance, worshipped multiple gods and people in other cultures worshipped celestial bodies or forces in nature. Herbert might have argued that, lacking a belief in a supreme deity, these practices were not religions at all but belonged instead in some other category such as superstition, heresy, or magic. But Herbert did include them, arguing that they were religions because the multiple gods were actually servants to or even aspects of the one supreme deity, and those who worshiped natural forces worshipped the supreme deity “in His works”.

The concept religion understood as a social genus was increasingly put to use by to European Christians as they sought to categorize the variety of cultures they encountered as their empires moved into the Americas, South Asia, East Asia, Africa, and Oceania. In this context, fed by reports from missionaries and colonial administrators, the extension of the generic concept was expanded. The most influential example is that of anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor (1832–1917) who had a scholarly interest in pre-Columbian Mexico. Like Herbert, Tylor sought to identify the common denominator of all religions, what Tylor called a “minimal definition” of religion, and he proposed that the key characteristic was “belief in spiritual beings” (1871 [1970: 8]). This generic definition included the forms of life predicated on belief in a supreme deity that Herbert had classified as religion. But it could also now include—without Herbert’s procrustean assumption that these practices were really directed to one supreme being—the practices used by Hindus, ancient Athenians, and the Navajo to connect to the gods they revere, the practices used by Mahayana Buddhists to connect to Bodhisattvas, and the practices used by Malagasy people to connect to the cult of the dead. The use of a unifying concept for such diverse practices is deliberate on Tylor’s part as he sought to undermine assumptions that human cultures poorly understood in Christian Europe—especially those despised ones, “painted black on the missionary maps” (1871 [1970: 4])—were not on the very same spectrum as the religion of his readers. This opposition to dividing European and non-European cultures into separate categories underlies Tylor’s insistence that all human beings are equivalent in terms of their intelligence. He argued that so-called “primitive” peoples generate their religious ideas when they wrestle with the same questions that all people do, such as the biological question of what explains life, and they do so with the same cognitive capacities. They may lack microscopes or telescopes, but Tylor claims that they seek to answer these questions in ways that are “rational”, “consistent”, and “logical”. Tylor repeatedly calls the Americans, Africans, and Asians he studies “thinking men” and “philosophers”. Tylor was conscious that the definition he proposed was part of a shift: though it was still common to describe some people as so primitive that they had no religion, Tylor complains that those who speak this way are guilty of “the use of wide words in narrow senses” because they are only willing to describe as religion practices that resemble their own expectations (1871 [1970: 3–4]).

In the twentieth century, one sees a third and last growth spurt in the extension of the concept. Here the concept religion is enlarged to include not only practices that connect people to one or more spirits, but also practices that connect people to “powers” or “forces” that lack minds, wills, and personalities. One sees this shift in the work of William James, for example, when he writes,

Were one asked to characterize the life of religion in the broadest and most general terms possible, one might say that it consists of the belief that there is an unseen order, and our supreme good lies in harmoniously adjusting ourselves thereto. (1902 [1985: 51]; cf. Proudfoot 2000)

By an “unseen order”, James presumably means a structure that is non-empirical, though he is not clear about why the term would not also include political, economic, or other invisible but human-created orders. The same problem plagues James’s description of “a MORE” operating in the universe that is similar to but outside oneself (1902 [1985: 400], capitalization in the original). The anthropologist Clifford Geertz addresses this issue, also defining religion in terms of an “order” but specifying that he means practices tied to conceptions of “a general order of existence”, that is, as he also says, something whose existence is “fundamental”, “all-pervading”, or “unconditioned” (1973: 98, emphasis added). The practices that are distinctly religious for Geertz are those tied to a culture’s metaphysics or worldview, their conception of “the overall shape of reality” (1973: 104). Like James, then, Geertz would include as religions not only the forms of life based on the theistic and polytheistic (or, more broadly, animist or spiritualist) beliefs that Herbert and Tylor recognized, but also those based on belief in the involuntary, spontaneous, or “natural” operations of the law of karma, the Dao in Daoism, the Principle in Neo-Confucianism, and the Logos in Stoicism. This expansion also includes Theravada Buddhism because dependent co-origination ( pratītyasamutpāda ) is a conception of the general order of existence and it includes Zen Buddhism because Buddha-nature is said to pervade everything. This third expansion is why non-theistic forms of Buddhism, excluded by the Herbert’s and Tylor’s definitions but today widely considered religions, can serve as “a litmus test” for definitions of the concept (Turner 2011: xxiii; cf. Southwold 1978). In sum, then, one can think of the growth of the social genus version of the concept religion as analogous to three concentric circles—from a theistic to a polytheistic and then to a cosmic (or “cosmographic” [Dubuisson 1998]) criterion. Given the near-automatic way that Buddhism is taken as a religion today, the cosmic version now seems to be the dominant one.

Some scholars resist this third expansion of the concept and retain a Tylorean definition, and it is true that there is a marked difference between practices that do and practices that do not involve interacting with person-like beings. In the former, anthropomorphic cases, practitioners can ask for help, make offerings, and pray with an understanding that they are heard. In the latter, non-anthropomorphic cases, practitioners instead typically engage in actions that put themselves “in accord with” the order of things. The anthropologist Robert Marett marks this difference between the last two extensions of the concept religion by distinguishing between “animism” and “animatism” (1909), the philosopher John Hick by distinguishing between religious “personae” and religious “impersonae” (1989: ch. 14–15). This difference raises a philosophical question: on what grounds can one place the practices based on these two kinds of realities in the same category? The many loa spirits, the creator Allah, and the all-pervading Dao are not available to the methods of the natural sciences, and so they are often called “supernatural”. If that term works, then religions in all three concentric circles can be understood as sets of practices predicated on belief in the supernatural. However, “supernatural” suggests a two-level view of reality that separates the empirically available natural world from some other realm metaphorically “above” or “behind” it. Many cultures lack or reject a distinction between natural and supernatural (Saler 1977, 2021). They believe that disembodied persons or powers are not in some otherworldly realm but rather on the top of a certain mountain, in the depths of the forest, or “everywhere”. To avoid the assumption of a two-level view of reality, then, some scholars have replaced supernatural with other terms, such as “superhuman”. Hick uses the term “transcendent”:

the putative reality which transcends everything other than itself but is not transcended by anything other than itself. (1993: 164)

In order to include loa , Allah, and the Dao but to exclude nations and economies, Kevin Schilbrack (2013) proposes the neologism “superempirical” to refer to non-empirical things that are also not the product of any empirical thing. Wouter Hanegraaff (1995), following J. G. Platvoet (1982: 30) uses “meta-empirical”. Whether a common element can be identified that will coherently ground a substantive definition of “religion” is not a settled question.

Despite this murkiness, all three of these versions are “substantive” definitions of religion because they determine membership in the category in terms of the presence of a belief in a distinctive kind of reality. In the twentieth century, however, one sees the emergence of an importantly different approach: a definition that drops the substantive element and instead defines the concept religion in terms of a distinctive role that a form of life can play in one’s life—that is, a “functional” definition. One sees a functional approach in Emile Durkheim (1912), who defines religion as whatever system of practices unite a number of people into a single moral community (whether or not those practices involve belief in any unusual realities). Durkheim’s definition turns on the social function of creating solidarity. One also sees a functional approach in Paul Tillich (1957), who defines religion as whatever dominant concern serves to organize a person’s values (whether or not that concern involve belief in any unusual realities). Tillich’s definition turns on the axiological function of providing orientation for a person’s life.

Substantive and functional approaches can produce non-overlapping extensions for the concept. Famously, a functional approach can hold that even atheistic forms of capitalism, nationalism, and Marxism function as religions. The literature on these secular institutions as functionally religions is massive. As Trevor Ling says,

the bulk of literature supporting the view that Marxism is a religion is so great that it cannot easily be set aside. (1980: 152)

On capitalism as a religion, see, e.g., McCarraher (2019); on nationalism, see, e.g., Omer and Springs (2013: ch. 2). One functionalist might count white supremacy as a religion (Weed 2019; Finley et al. 2020) and another might count anti-racism as a religion (McWhorter 2021). Here, celebrities can reach a religious status and fandom can be one’s religious identity (e.g., Lofton 2011; Lovric 2020). Without a supernatural, transcendent, or superempirical element, these phenomena would not count as religious for Herbert, Tylor, James, or Geertz. Conversely, interactions with supernatural beings may be categorized on a functional approach as something other than religion. For example, the Thai villager who wears an apotropaic amulet and avoids the forest because of a belief that malevolent spirits live there, or the ancient Roman citizen who takes a bird to be sacrificed in a temple before she goes on a journey are for Durkheim examples of magic rather than religion, and for Tillich quotidian rather than ultimate concerns.

It is sometimes assumed that to define religion as a social genus is to treat it as something universal, as something that appears in every human culture. It is true that some scholars have treated religion as pan-human. For example, when a scholar defines religion functionally as the beliefs and practices that generate social cohesion or as the ones that provide orientation in life, then religion names an inevitable feature of the human condition. The universality of religion that one then finds is not a discovery but a product of one’s definition. However, a social genus can be both present in more than one culture without being present in all of them, and so one can define religion , either substantively or functionally, in ways that are not universal. As common as beliefs in disembodied spirits or cosmological orders have been in human history, for instance, there were people in the past and there are people in the present who have no views of an afterlife, supernatural beings, or explicit metaphysics.

2. Two Kinds of Analysis of the Concept

The history of the concept religion above shows how its senses have shifted over time. A concept used for scrupulous devotion was retooled to refer to a particular type of social practice. But the question—what type?—is now convoluted. The cosmic version of the concept is broader than the polytheistic version, which is in turn broader than the theistic version, and the functional definitions shift the sense of the term into a completely different register. What is counted as religion by one definition is often not counted by others. How might this disarray be understood? Does the concept have a structure? This section distinguishes between two kinds of answer to these questions. Most of the attempts to analyze the term have been “monothetic” in that they operate with the classical view that every instance that is accurately described by a concept will share a defining property that puts them in that category. The last several decades, however, have seen the emergence of “polythetic” approaches that abandon the classical view and treat religion , instead, as having a prototype structure. For incisive explanations of the classical theory and the prototype theory of concepts, see Laurence and Margolis (1999).

Monothetic approaches use a single property (or a single set of properties) as the criterion that determines whether a concept applies. The key to a monothetic approach is that it proposes necessary and sufficient conditions for membership in the given class. That is, a monothetic approach claims that there is some characteristic, or set of them, found in every religion and that if a form of life has it, then that form of life is a religion. Most definitions of the concept religion have been of this type. For example, as we saw above, Edward Tylor proposes belief in spiritual beings as his minimal definition of religion, and this is a substantive criterion that distinguishes religion from non-religion in terms of belief in this particular kind of entity. Similarly, Paul Tillich proposes ultimate concern as a functional criterion that distinguishes religion from non-religion in terms of what serves this particular role in one’s life. These are single criterion monothetic definitions.

There are also monothetic definitions that define religion in terms of a single set of criteria. Herbert’s five Common Notions are an early example. More recently, Clifford Geertz (1973: ch. 4) proposes a definition that he breaks down into five elements:

- a system of symbols

- about the nature of things,

- that inculcate dispositions for behavior

- through ritual and cultural performance, [ 3 ]

- so that the conceptions held by the group are taken as real.

One can find each of these five elements separately, of course: not all symbols are religious symbols; historians (but not novelists) typically consider their conceptions factual; and so on. For Geertz, however, any religious form of life will have all five. Aware of functional approaches like that of Tillich, Geertz is explicit that symbols and rituals that lack reference to a metaphysical framework—that is, those without the substantive element he requires as his (2)—would be secular and not religious, no matter how intense or important one’s feelings about them are (1973: 98). Reference to a metaphysical entity or power is what marks the other four elements as religious. Without it, Geertz writes, “the empirical differentia of religious activity or religious experience would not exist” (1973: 98). As a third example, Bruce Lincoln (2006: ch. 1) enumerates four elements that a religion would have, namely:

- “a discourse whose concerns transcend the human, temporal, and contingent, and that claims for itself a similarly transcendent status”,

- practices connected to that discourse,

- people who construct their identity with reference to that discourse and those practices, and

- institutional structures to manage those people.

This definition is monothetic since, for Lincoln, religions always have these four features “at a minimum” (2006: 5). [ 4 ] To be sure, people constantly engage in practices that generate social groups that then have to be maintained and managed by rules or authorities. However, when the practices, communities, and institutions lack the distinctive kind of discourse that claims transcendent status for itself, they would not count for Lincoln as religions.

It is worth noting that when a monothetic definition includes multiple criteria, one does not have to choose between the substantive and functional strategies for defining religion , but can instead include both. If a monothetic definition include both strategies, then, to count as a religion, a form of life would have to refer to a distinctive substantive reality and also play a certain role in the participants’ lives. This double-sided approach avoids the result of purely substantive definitions that might count as religion a feckless set of beliefs (for instance, “something must have created the world”) unconnected from the believers’ desires and behavior, while also avoiding the result of purely functional definitions that might count as religion some universal aspect of human existence (for instance, creating collective effervescence or ranking of one’s values). William James’s definition of religion (“the belief that there is an unseen order, and our supreme good lies in harmoniously adjusting ourselves thereto”) is double-sided in this way, combining a belief in the existence of a distinctive referent with the spiritual disciplines with which one seeks to embody that belief. Geertz’s definition of religion also required both substantive and functional aspects, which he labelled “worldview” and “ethos” (1973: ch. 5). To treat religion as “both/and” in this way is to refuse to abstract one aspect of a complex social reality but instead recognizes, as Geertz puts it, both “the dispositional and conceptual aspects of religious life” (1973: 113). [ 5 ]

These “monothetic-set definitions” treat the concept of religion as referring to a multifaceted or multidimensional complex. It may seem avant garde today to see religion described as a “constellation”, “assemblage”, “network”, or “system”, but in fact to treat religion as a complex is not new. Christian theologians traditionally analyzed the anatomy of their way of life as simultaneously fides , fiducia , and fidelitas . Each of these terms might be translated into English as “faith”, but each actually corresponds to a different dimension of a social practice. Fides refers to a cognitive state, one in which a person assents to a certain proposition and takes it as true. It could be translated as “belief” or “intellectual commitment”. Beliefs or intellectual commitments distinctive to participation in the group will be present whether or not a religious form of life has developed any authoritative doctrines. In contrast, fiducia refers to an affective state in which a person is moved by a feeling or experience that is so positive that it bonds the recipient to its source. It could be translated as “trust” or “emotional commitment”. Trust or emotional commitment will be present whether or not a religious form of life teaches that participation in their practices aims at some particular experience of liberation, enlightenment, or salvation. And fidelitas refers to a conative state in which a person commits themselves to a path of action, a path that typically involves emulating certain role models and inculcating the dispositions that the group considers virtuous. It could be translated as “loyalty” or “submission”. Loyalty or submission will be present whether or not a religious form of life is theistic or teaches moral rules. By the time of Martin Luther, Christian catechisms organized these aspects of religious life in terms of the “three C’s”: the creed one believed, the cult or worship one offered, and the code one followed. When Tillich (1957: ch. 2) argues that religious faith is distorted when one treats it not as a complex but instead as a function of the intellect alone, emotion alone, or the will alone, he is speaking from within this tradition. These three dimensions of religious practices—symbolically, the head, the heart, and the hand—are not necessarily Christian. In fact, until one adds a delimiting criterion like those discussed above, these dimensions are not even distinctively religious. Creed, cult, and code correspond to any pursuit of what a people considers true, beautiful, and good, respectively, and they will be found in any collective movement or cultural tradition. As Melford Spiro says, any human institution will involve a belief system, a value system, and an action system (Spiro 1966: 98).

Many have complained that arguments about how religion should be defined seem unresolvable. To a great extent, however, this is because these arguments have not simply been about a particular aspect of society but rather have served as proxy in a debate about the structure of human subjectivity. There is deep agreement among the rival positions insofar as they presuppose the cognitive-affective-conative model of being human. However, what we might call a “Cartesian” cohort argues that cognition is the root of religious emotions and actions. This cohort includes the “intellectualists” whose influence stretches from Edward Tylor and James Frazer to E. E. Evans-Pritchard, Robin Horton, Jack Goody, Melford Spiro, Stewart Guthrie, and J. Z. Smith, and it shapes much of the emerging field of cognitive science of religion (e.g., Boyer 2001). [ 6 ] A “Humean” cohort disagrees, arguing that affect is what drives human behavior and that cognition serves merely to justify the values one has already adopted. In theology and religious studies, this feelings-centered approach is identified above all with the work of Friedrich Schleiermacher and Rudolf Otto, and with the tradition called phenomenology of religion, but it has had a place in anthropology of religion since Robert Marett (Tylor’s student), and it is alive and well in the work of moral intuitionists (e.g., Haidt 2012) and affect theory (e.g., Schaefer 2015). A “Kantian” cohort treats beliefs and emotions regarding supernatural realities as relatively unimportant and argues instead that for religion the will is basic. [ 7 ] This approach treats a religion as at root a set of required actions (e.g., Vásquez 2011; C. Smith 2017). These different approaches disagree about the essence of religion, but all three camps operate within a shared account of the human. Thus, when William James describes religion as

the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual [people] in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider the divine. (1902 [1985: 34])

he is foregrounding an affective view and playing down (though not denying) the cognitive. When James’s Harvard colleague Alfred North Whitehead corrects him, saying that “[r]eligion is what a person does with their solitariness” (1926: 3, emphasis added), Whitehead stresses the conative, though Whitehead also insists that feelings always play a role. These are primarily disagreements of emphasis that do not trouble this model of human subjectivity. There have been some attempts to leave this three-part framework. For example, some in the Humean camp have suggested that religion is essentially a particular feeling with zero cognition. But that romantic suggestion collapses under the inability to articulate how an affective state can be noncognitive but still identifiable as a particular feeling (Proudfoot 1985).

Although the three-sided model of the true, the beautiful, and the good is a classic account of what any social group explicitly and implicitly teaches, one aspect is still missing. To recognize the always-presupposed material reality of the people who constitute the social group, even when this reality has not been conceptualized by the group’s members, one should also include the contributions of their bodies, habits, physical culture, and social structures. To include this dimension mnemonically, one can add a “fourth C”, for community. Catherine Albanese (1981) may have been the first to propose the idea of adding this materialist dimension. Ninian Smart’s famous anatomy of religion (1996) has seven dimensions, not four, but the two models are actually very similar. Smart calls the affective dimension the “experiential and emotional”, and then divides the cognitive dimension into two (“doctrinal and philosophical” and “narrative and mythological”), the conative into two (“ethical and legal” and “ritual”), and the communal into two (“social and institutional” and “material”). In an attempt to dislodge the focus on human subjectivity found in the three Cs, some have argued that the material dimension is the source of the others. They argue, in other words, that the cognitive, affective, and conative aspects of the members of a social group are not the causes but rather the effects of the group’s structured practices (e.g., Asad 1993: ch. 1–4; Lopez 1998). Some argue that to understand religion in terms of beliefs, or even in terms of any subjective states, reflects a Protestant bias and that scholars of religion should therefore shift attention from hidden mental states to the visible institutional structures that produce them. Although the structure/agency debate is still live in the social sciences, it is unlikely that one can give a coherent account of religion in terms of institutions or disciplinary practices without reintroducing mental states such as judgements, decisions, and dispositions (Schilbrack 2021).

Whether a monothetic approach focuses on one essential property or a set, and whether that essence is the substance or the function of the religion, those using this approach ask a Yes/No question regarding a single criterion. This approach therefore typically produces relatively clear lines between what is and is not religion. Given Tylor’s monothetic definition, for instance, a form of life must include belief in spiritual beings to be a religion; a form of life lacking this property would not be a religion, even if it included belief in a general order of existence that participants took as their ultimate concern, and even if that form of life included rituals, ethics, and scriptures. In a famous discussion, Melford Spiro (1966) works with a Tylorean definition and argues exactly this: lacking a belief in superhuman beings, Theravada Buddhism, for instance, is something other than a religion. [ 8 ] For Spiro, there is nothing pejorative about this classification.

Having combatted the notion that “we” have religion (which is “good”) and “they” have superstition (which is “bad”), why should we be dismayed if it be discovered that that society x does not have religion as we have defined the term? (1966: 88)

That a concept always corresponds to something possessing a defining property is a very old idea. This assumption undergirds Plato’s Euthyphro and other dialogues in which Socrates pushes his interlocutors to make that hidden, defining property explicit, and this pursuit has provided a model for much not only of philosophy, but of the theorizing in all fields. The traditional assumption is that every entity has some essence that makes it the thing it is, and every instance that is accurately described by a concept of that entity will have that essence. The recent argument that there is an alternative structure—that a concept need not have necessary and sufficient criteria for its application—has been called a “conceptual revolution” (Needham 1975: 351), “one of the greatest and most valuable discoveries that has been made of late years in the republic of letters” (Bambrough 1960–1: 207).

In discussions of the concept religion , this anti-essentialist approach is usually traced to Ludwig Wittgenstein (1953, posthumous). Wittgenstein argues that, in some cases, when one considers the variety of instances described with a given concept, one sees that among them there are multiple features that “crop up and disappear”, the result being “a complicated network of similarities overlapping and criss-crossing” (Wittgenstein 1953, §68). The instances falling under some concepts lack a single defining property but instead have a family resemblance to each other in that each one resembles some of the others in different ways. All polythetic approaches reject the monothetic idea that a concept requires necessary and sufficient criteria. But unappreciated is the fact that polythetic approaches come in different kinds, operating with different logics. Here are three.

The most basic kind of polythetic approach holds that membership in a given class is not determined by the presence of a single crucial characteristic. Instead, the concept maps a cluster of characteristics and, to count as a member of that class, a particular case has to have a certain number of them, no particular one of which is required. To illustrate, imagine that there are five characteristics typical of religions (call this the “properties set”) and that, to be a religion, a form of life has to have a minimum of three of them (call this the “threshold number”). Because this illustration limits the number of characteristics in the properties set, I will call this first kind a “bounded” polythetic approach. For example, the five religion-making characteristics could be these:

- belief in superempirical beings or powers,

- ethical norms,

- worship rituals,

- participation believed to bestow benefits on participants, and

- those who participate in this form of life see themselves as a distinct community.

Understanding the concept religion in this polythetic way produces a graded hierarchy of instances. [ 9 ] A form of life that has all five of these characteristics would be a prototypical example of a religion. Historically speaking, prototypical examples of the concept are likely to be instances to which the concept was first applied. Psychologically speaking, they are also likely to be the example that comes to mind first to those who use the concept. For instance, robins and finches are prototypical examples of a bird, and when one is prompted to name a bird, people are more likely to name a robin or a finch than an ostrich or a penguin. A form of life that has only four of these characteristics would nevertheless still be a clear example of a religion. [ 10 ] If a form of life has only three, then it would be a borderline example. A form of life that has only two of these characteristics would not be included in the category, though such cases might be considered “quasi-religions” and they might be the most interesting social forms to compare to religions (J. E. Smith 1994). A form of life that only had one of the five characteristics would be unremarkable. The forms of life that had three, four, or five of these characteristics would not be an unrelated set but rather a “family” with multiple shared features, but no one characteristic (not even belief in superempirical beings or powers) possessed by all of them. On this polythetic approach, the concept religion has no essence, and a member of this family that only lacked one of the five characteristics— no matter which one —would still clearly be a religion. [ 11 ] As Benson Saler (1993) points out, one can use this non-essentialist approach not only for the concept religion but also for the elements within a religion (sacrifice, scripture, and so on) and to individual religions (Christianity, Hinduism, and so on).

Some have claimed that, lacking an essence, polythetic approaches to religion make the concept so vague that it becomes useless (e.g., Fitzgerald 2000: 72–3; Martin 2009: 167). Given the focused example of a “bounded” approach in the previous paragraph and the widespread adoption of polythetic approaches in the biological sciences, this seems clearly false. However, it is true that one must pay attention to the parameters at work in a polythetic approach. Using a properties set with only five elements produces a very focused class, but the properties set is simply a list of similarities among at least two of the members of a class, and since the class of religions might have hundreds of members, one could easily create a properties set that is much bigger. Not long after Wittgenstein’s death, a “bounded” polythetic approach was applied to the concept religion by William Alston who identified nine religion-making characteristics. [ 12 ] Southwold (1978) has twelve; Rem Edwards (1972) has fourteen and leaves room for more. But there is no reason why one might not work with a properties set for religion with dozens or even hundreds of shared properties. Half a century ago, Rodney Needham (1975: 361) mentions a computer program that sorted 1500 different bacterial strains according to 200 different properties. As J. Z. Smith (1982: ch. 1) argues, treating the concept religion in this way can lead to surprising discoveries of patterns within the class and the co-appearance of properties that can lead to explanatory theories. The second key parameter for a polythetic approach is the threshold number. Alston does not stipulate the number of characteristics a member of the class has to have, saying simply, “When enough of these characteristics are present to a sufficient degree, we have a religion” (1967: 142). Needham (1975) discusses the sensible idea that each member has a majority of the properties, but this is not a requirement of polythetic approaches. The critics are right that as one increases the size of the properties set and decreases the threshold number, the resulting category becomes more and more diffuse. This can produce a class that is so sprawling that it is difficult to use for empirical study.

Scholars of religion who have used a polythetic approach have typically worked with a “bounded” approach (that is, with a properties set that is fixed), but this is not actually the view for which Wittgenstein himself argues. Wittgenstein’s goal is to draw attention to the fact that the actual use of concepts is typically not bound: “the extension of the concept is not closed by a frontier” (Wittgenstein 1953, §67). We can call this an “open” polythetic approach. To grasp the open approach, consider a group of people who have a concept they apply to a certain range of instances. In time, a member of the group encounters something new that resembles the other instances enough in her eyes that she applies the concept to it. When the linguistic community adopts this novel application, the extension of the concept grows. If their use of the concept is “open”, however, then, as the group adds a new member to the category named by a concept, properties of that new member that had not been part of the earlier uses can be added to the properties set and thereby increase the range of legitimate applications of the concept in the future. We might say that a bounded polythetic approach produces concepts that are fuzzy, and an open polythetic approach produces concepts that are fuzzy and evolving . Timothy Williamson calls this “the dynamic quality of family resemblance concepts” (1994: 86). One could symbolize the shift of properties over time this way:

Wittgenstein famously illustrated this open polythetic approach with the concept game , and he also applied it to the concepts of language and number (Wittgenstein 1953, §67). If we substitute our concept as Wittgenstein’s example, however, his treatment fits religion just as well:

Why do we call something a “religion”? Well, perhaps because it has a direct relationship with several things that have hitherto been called religion; and this can be said to give an indirect relationship to other things we call the same name. (Wittgenstein 1953, §67)

Given an open polythetic approach, a concept evolves in the light of the precedents that speakers recognize, although, over time, what people come to label with the concept can become very different from the original use.

In the academic study of religions, discussions of monothetic and polythetic approaches have primarily been in service of developing a definition of the term. [ 13 ] How can alternate definitions of religion be assessed? If one were to offer a lexical definition (that is, a description of what the term means in common usage, as with a dictionary definition), then the definition one offers could be shown to be wrong. In common usage, for example, Buddhism typically is considered a religion and capitalism typically is not. On this point, some believe erroneously that one can correct a definition by pointing to some fact about the referents of the term. One sees this assumption, for example, in those who argue that the western discovery of Buddhism shows that theistic definitions of religion are wrong (e.g., Southwold 1978: 367). One can correct a real or lexical definition in this way, but not a stipulative definition, that is, a description of the meaning that one assigns to the term. When one offers a stipulative definition, that definition cannot be wrong. Stipulative definitions are assessed not by whether they are true or false but rather by their usefulness, and that assessment will be purpose-relative (cf. Berger 1967: 175). De Muckadell (2014) rejects stipulative definitions of religion for this reason, arguing that one cannot critique them and that they force scholars simply to “accept whatever definition is offered”. She gives the example of a problematic stipulative definition of religion as “ice-skating while singing” which, she argues, can only be rejected by using a real definition of religion that shows the ice-skating definition to be false. However, even without knowing the real essence of religion, one can critique a stipulative definition, either for being less adequate or appropriate for a particular purpose (such as studying forms of life across cultures) or, as with the ice-skating example, for being so far from a lexical definition that it is adequate or appropriate for almost no purpose.

Polythetic definitions are increasingly popular today as people seek to avoid the claim that an evolving social category has an ahistorical essence. [ 14 ] However, the difference between these two approaches is not that monothetic definitions fasten on a single property whereas polythetic definitions recognize more. Monothetic definitions can be multifactorial, as we have seen, and they can recognize just as many properties that are “common” or even “typical” of religions, without being essential. The difference is also not that the monothetic identification of the essence of religion reflects an ethnocentrism that polythetic approaches avoid. The polythetic identification of a prototypical religion is equally ethnocentric. The difference between them, rather, is that a monothetic definition sorts instances with a Yes/No mechanism and is therefore digital, and a polythetic definition produces gradations and is therefore analog. It follows that a monothetic definition treats a set of instances that all possess the one defining property as equally religion, whereas a polythetic definition produces a gray area for instances that are more prototypical or less so. This makes a monothetic definition superior for cases (for example, legal cases) in which one seeks a Yes/No answer. Even if an open polythetic approach accurately describes how a concept operates, therefore, one might, for purposes of focus or clarity, prefer to work with a closed polythetic account that limits the properties set, or even with a monothetic approach that limits the properties set to one. That is, one might judge that it is valuable to treat the concept religion as structurally fuzzy or temporally fluid, but nevertheless place boundaries on the forms of life one will compare.

This strategy gives rise to a third kind of polythetic approach, one that stipulates that one property (or one set of properties) is required. Call this an “anchored” polythetic definition. Consistently treating concepts as tools, Wittgenstein suggests this “anchored” idea when he writes that when we look at the history of a concept,

what we see is something constantly fluctuating … [but we might nevertheless] set over against this fluctuation something more fixed, just as one paints a stationary picture of the constantly altering face of the landscape. (1974: 77)

Given a stipulated “anchor”, a concept will then possess a necessary property, and this property reintroduces essentialism. Such a definition nevertheless still reflects a polythetic approach because the presence of the required property is not sufficient to make something a religion. To illustrate this strategy, one might stipulate that the only forms of life one will consider a religion will include

(thereby excluding nationalism and capitalism, for example), but the presence of this property does not suffice to count this form of life as a religion. Consider the properties set introduced above that also includes

If the threshold number is still three, then to be a religion, a form of life would have to have three of these properties, one of which must be (A) . An anchored definition of religion like this would have the benefits of the other polythetic definitions. For example, it would not produce a clear line between religion and nonreligion but would instead articulate gradations between different forms of life (or between versions of one form of life at different times) that are less or more prototypically religious. However, given its anchor, it would produce a more focused range of cases. [ 15 ] In this way, the use of an anchor might both reflect the contemporary cosmological view of the concept religion and also address the criticism that polythetic approaches make a concept too vague.

Over the past forty years or so, there has been a reflexive turn in the social sciences and humanities as scholars have pulled the camera back, so to speak, to examine the constructed nature of the objects previously taken for granted as unproblematically “there”. Reflexive scholars have argued that the fact that what counts as religion shifts according to one’s definition reflects an arbitrariness in the use of the term. They argue that the fact that religion is not a concept found in all cultures but rather a tool invented at a certain time and place, by certain people for their own purposes, and then imposed on others, reveals its political character. The perception that religion is a politically motivated conceptual invention has therefore led some to skepticism about whether the concept picks out something real in the world. As with instrumentalism in philosophy of science, then, reflection on religion has raised doubts about the ontological status of the referent of one’s technical term.

A watershed text for the reflexive turn regarding the concept religion is Jonathan Z. Smith’s Imagining Religion (1982). Smith engages simultaneously in comparing religions and in analyzing the scholarly practice of comparison. A central theme of his essays is that the concept religion (and subcategories such as world religions , Abrahamic faiths , or nonliterate traditions ) are not scientific terms but often reflect the unrecognized biases of those who use these concepts to sort their world into those who are or are not “like us”. [ 16 ] Smith shows that, again and again, the concept religion was shaped by implicit Protestant assumptions, if not explicit Protestant apologetics. In the short preface to that book, Smith famously says,

[ T ] here is no data for religion . Religion is solely the creation of the scholar’s study. It is created for the scholar’s analytic purposes by his imaginative acts of comparison and generalization. Religion has no independent existence apart from the academy. (1982: xi, italics in original)

This dramatic statement has sometimes been taken as Smith’s assertion that the concept religion has no referent. However, in his actual practice of comparing societies, Smith is not a nonrealist about religion . In the first place, he did not think that the constructed nature of religion was something particular to this concept: any judgement that two things were similar or different in some respect presupposed a process of selection, juxtaposition, and categorization by the observer. This is the process of imagination in his book’s title. Second, Smith did not think that the fact that concepts were human products undermined the possibility that they successfully corresponded to entities in the world: an invented concept for social structures can help one discover religion—not “invent” it—even in societies whose members did not know the concept. [ 17 ] His slogan is that one’s (conceptual) map is not the same as and should be tested and rectified by the (non-conceptual) territory (J. Z. Smith 1978). Lastly, Smith did not think that scholars should cease to use religion as a redescriptive or second-order category to study people in history who lacked a comparable concept. On the contrary, he chastised scholars of religion for resting within tradition-specific studies, avoiding cross-cultural comparisons, and not defending the coherence of the generic concept. He writes that scholars of religion should be

prepared to insist, in some explicit and coherent fashion, on the priority of some generic category of religion. (1995: 412; cf. 1998: 281–2)

Smith himself repeatedly uses religion and related technical terms he invented, such as “locative religion”, to illuminate social structures that operate whether or not those so described had named those structures themselves—social structures that exist, as his 1982 subtitle says, from Babylon to Jonestown.

The second most influential book in the reflexive turn in religious studies is Talal Asad’s Genealogies of Religion (1993). Adopting Michel Foucault’s “genealogical” approach, Asad seeks to show that the concept religion operating in contemporary anthropology has been shaped by assumptions that are Christian (insofar as one takes belief as a mental state characteristic of all religions) and modern (insofar as one treats religion as essentially distinct from politics). Asad’s Foucauldian point is that though people may have all kinds of religious beliefs, experiences, moods, or motivations, the mechanism that inculcates them will be the disciplining techniques of some authorizing power and for this reason one cannot treat religion as simply inner states. Like Smith, then, Asad asks scholars to shift their attention to the concept religion and to recognize that assumptions baked into the concept have distorted our grasp of the historical realities. However, also like Smith, Asad does not draw a nonrealist conclusion. [ 18 ] For Asad, religion names a real thing that would operate in the world even had the concept not been invented, namely, “a coherent existential complex” (2001: 217). Asad’s critical aim is not to undermine the idea that religion exists qua social reality but rather to undermine the idea that religion is essentially an interior state independent of social power. He points out that anthropologists like Clifford Geertz adopt a hermeneutic approach to culture that treats actions as if they are texts that say something, and this approach has reinforced the attention given to the meaning of religious symbols, deracinated from their social and historical context. Asad seeks to balance this bias for the subjective with a disciplinary approach that sees human subjectivity as also the product of social structures. Smith and Asad are therefore examples of scholars who critique the concept religion without denying that it can still refer to something in the world, something that exists even before it is named. They are able, so to speak, to look at one’s conceptual window without denying that the window provides a perspective on things outside.

Other critics have gone farther. They build upon the claims that the concept religion is an invented category and that its modern semantic expansion went hand in hand with European colonialism, and they argue that people should cease treating religion as if it corresponds to something that exists outside the sphere of modern European influence. It is common today to hear the slogan that there is no such “thing” as religion. In some cases, the point of rejecting thing-hood is to deny that religion names a category, all the instances of which focus on belief in the same kind of object—that is, the slogan is a rejection of substantive definitions of the concept (e.g., Possamai 2018: ch. 5). In this case, the objection bolsters a functional definition and does not deny that religion corresponds to a functionally distinct kind of form of life. Here, the “no such thing” claim reflects the unsettled question, mentioned above, about the grounds of substantive definitions of “religion”. In other cases, the point of this objection is to deny that religion names a defining characteristic of any kind—that is, the slogan is a rejection of all monothetic definitions of the concept. Perhaps religion (or a religion, like Judaism) should always be referred to in the plural (“Judaisms”) rather than the singular. In this case, the objection bolsters a polythetic definition and does not deny that religion corresponds to a distinct family of forms of life. Here, the “no such thing” claim rejects the assumption that religion has an essence. Despite their negativity, these two objections to the concept are still realist in that they do not deny that the phrase “a religion” can correspond to a form of life operating in the world.

More radically, one sees a denial of this realism, for example, in the critique offered by Wilfred Cantwell Smith (1962). Smith’s thesis is that in many different cultures, people developed a concept for the individuals they considered pious, but they did not develop a concept for a generic social entity, a system of beliefs and practices related to superempirical realities. Before modernity, “there is no such entity [as religion and] … the use of a plural, or with an article, is false” (1962: 326, 194; cf. 144). Smith recommends dropping religion . Not only did those so described lack the concept, but the use of the concept also treats people’s behavior as if the phrase “a religion” names something in addition to that behavior. A methodological individualist, Smith denies that groups have any reality not explained by the individuals who constitute them. What one finds in history, then, is religious people, and so the adjective is useful, but there are no religious entities above and beyond those people, and so the noun reifies an abstraction. Smith contends that

[n]either religion in general nor any one of the religions … is in itself an intelligible entity, a valid object of inquiry or of concern either for the scholar or for the [person] of faith. (1962: 12)

More radical still are the nonrealists who argue that the concepts religion, religions, and religious are all chimerical. Often drawing on post-structuralist arguments, these critics propose that the notion that religions exist is simply an illusion generated by the discourse about them (e.g., McCutcheon 1997; 2018; Fitzgerald 2000; 2007; 2017; Dubuisson 1998; 2019). As Timothy Fitzgerald writes, the concept religion

picks out nothing and it clarifies nothing … the word has no genuine analytical work to do and its continued use merely contributes to the general illusion that it has a genuine referent …. (2000: 17, 14; also 4)

Advocates of this position sometimes call their approach the “Critical Study of Religion” or simply “Critical Religion”, a name that signals their shift away from the pre-critical assumption that religion names entities in the world and to a focus on who invented the concept, the shifting contrast terms it has had, and the uses to which it has been put. [ 19 ] Like the concept of witches or the concept of biological races (e.g., Nye 2020), religion is a fiction (Fitzgerald 2015) or a fabrication (McCutcheon 2018), a concept invented and deployed not to respond to some reality in the world but rather to sort and control people. The classification of something as “religion” is not neutral but

a political activity, and one particularly related to the colonial and imperial situation of a foreign power rendering newly encountered societies digestible and manipulable in terms congenial to its own culture and agenda. (McCutcheon & Arnal 2012: 107)

As part of European colonial projects, the concept has been imposed on people who lacked it and did not consider anything in their society “their religion”. In fact, the concept was for centuries the central tool used to rank societies on a scale from primitive to civilized. To avoid this “conceptual violence” or “epistemic imperialism” (Dubuisson 2019: 137), scholars need to cease naturalizing this term invented in modern Europe and instead historicize it, uncovering the conditions that gave rise to the concept and the interests it serves. The study of religions outside Europe should end. As Timothy Fitzgerald writes, “The category ‘religion’ should be the object, not the tool, of analysis” (2000: 106; also 2017: 125; cf. McCutcheon 2018: 18).