- Contributors

- National Co-ordinators

- Online Advertisement

- Print Advertisement

- Subscribe HIC

Last Sunday of January, World Leprosy Eradication Day | February 4, World Cancer Day | February 6, International Day of Zero Tolerance to Female Genital Mutilation | February 10, National Deworming Day | February 12, Sexual Reproductive Health Awareness Day | March 12-18, World Glaucoma Week | March 8, International Women’s Day | Second Wednesday of March, No Smoking Day | Second Thursday of March, World Kidney Day | March 16, Measles Immunization Day | March 20, World Oral Health Day | March 21, World Down Syndrome Day | March 22, World Water Day | March 24, World TB Day | First Tuesday of May, World Asthma Day | Second Sunday of May, Mother’s Day | May 8, World Red Cross Day | May 8, World Thalassaemia Day | May 12, World Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Awareness Day | May 12, International Nurses day | May 16, National Dengue Day | May 19, World Family Doctor Day | May 25 (Last Wednesday of May), World Multiple Sclerosis Day | May 28, International Day of Action for Women’s Health / International Womens Health Day | May 31, Anti-tobacco Day / World no tobacco Day | First Tuesday of May, World Asthma Day | Second Sunday of May, Mother’s Day | May 8, World Red Cross Day | May 8, World Thalassaemia Day | May 12, World Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Awareness Day | May 12, International Nurses day | May 16, National Dengue Day | May 19, World Family Doctor Day | May 25 (Last Wednesday of May), World Multiple Sclerosis Day | May 28, International Day of Action for Women’s Health / International Womens Health Day | May 31, Anti-tobacco Day / World no tobacco Day | June 5, World Environment Day | June 8, World Brain Tumor Day | June 14, World Blood Donor Day | June 15, World Elder Abuse Awareness Day | June 18, Autistic Pride Day | June 21, International Day of Yoga | June 26, International Day against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking | July 1, National Doctors Day | July 11, World Population Day | July 28, World Hepatitis Day | July 29, ORS Day | August 1-7, World Breast Feeding Week | August 20, World Mosquito Day | 25th August – 8th September, National Eye Donation Fortnight | September 1 to 7, National Nutrition week | September 5, Spinal Cord Injury Day | September 10, World Suicide Prevention Day | September 21, World Alzheimer’s Day | September 25, World Pharmacist Day | September 28, World Rabies Day | September 29, World Heart Day | October 9, World Sight Day | October 10, World Mental Health Day | October 12, World Arthritis Day | October 15, Global Handwashing Day | October 16, World Food Day | October 17, World Trauma Day | October 20, World Osteoporosis Day | October 21, World Iodine Deficiency Day | October 24, World Polio Day | October 26, World Obesity Day | October 29, World Stroke Day | October 30, World Thrift Day | November 10, World Immunisation Day | November 12, World Pneumonia Day | November 14, World Diabetes Day | November 17, National Epilepsy Day | November 19, World COPD Day | November 19, World Toilet Day 2015 | November 15 – 21, New Born Care Week | November 16-22, World Antibiotic Awareness Week | December 1, World AIDS Day | December 2, National Pollution Prevention Day | December 3, International Day of persons with disabilities | December 9, World Patient Safety Day | December 12, Universal Health Coverage Day

GROWTH OF NURSING IN INDIA: HISTORICAL AND FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Dr. Punitha Ezhilarasu Consultant Indian Nursing Council

Nurses are two-thirds of health workforce in India. Their central roles in health care delivery in terms of promotion, prevention, treatment, care and rehabilitation are highly significant. Their contributions towards achieving UN millennium development goals (MDG) and sustainable development goals (SDG) are very crucial but not sufficient enough particularly in developing countries like India to create major impact on health outcomes. Achieving universal coverage, increasing health financing, recruitment, training and retention of health workforce are two important goals that have direct relevance to India. Nursing today has witnessed several changes, successes and challenges through a lot of stride and movement. Nurses have widened their scope of their work, however while the roles and responsibilities have multiplied, there are still concerns with regard to development of nursing, workforce, selection and recruitment, placement as per specialization, pre service, in service training and human resource (HR) issues for their career growth. This paper attempts to present the futuristic nursing in the light of historical and contemporary perspectives.

Historical perspectives

Nursing and Nursing Education

In the ancient era, until 17th century, formalized nursing was not traced. Every village had a dai/traditional birth attendant to take care of maternal and child health needs of the people. Military nursing was the earliest type of modern nursing introduced by the Portuguese in the 17th century. In 1664, East India Company started a hospital for soldiers at Fort St. Geroge, Madras. In 1797, a lying-in-hospital (Maternity) for the poor in Madras was built. Some of the other earliest hospitals were the first hospital in Calcutta in Fort William (1708), Calcutta medical college hospital and London mission hospital at Neyyoor (1838), Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy (J.J) group in Mumbai (1843), Thomasan hospital at Agra (1853), Holy Family Hospital, Delhi (1855), Civil hospital Amritsar (1860), CMC, Ludhiana, Punjab (1881), 1892 Miraj medical school and hospital, Maharashtra (1892) and Bowring hospital in Bangalore (1895).

Florence Nightingale was the first woman to have great influence over nursing in India and brought reforms in military and civilian hospitals in 1861. St. Stevens Hospital at Delhi was the first one to begin training Indian women as nurses in 1867. In 1871, the government General Hospital at Madras was started with the first school of nursing for midwives with four students. Many nursing schools were started in different states of India between 18th and 19th century mostly by mission hospitals, which trained Indians as nurses. At this time there was no uniform educational standards followed in nursing schools. In 1907-1910, in North India, United Board of Examiners for mission hospitals was set up which formulated training standards and rules. Later Mid India (1926) and South India (1913) boards (boards of CMAI) were set up which conducted examination and gave diplomas. The first school of Health visitors was started in 1918 by Lady Reading Health School, Delhi. The first four-year Basic B.Sc. program was established in 1946 at RAK College of Nursing in Delhi and CMC College of Nursing in Vellore. In 1960, M.Sc. was established in RAK College of Nursing, Delhi. In 1951, a two-year ANM course was established in St. Mary’s Hospital at Punjab.

Bombay Presidency Nursing Association was the first state nursing association established in 1890. In 1908, the Trained Nurses Association was formed to uphold the dignity and honor of nursing profession. The first state registration council at Madras Nursing Council was constituted in 1926 and Bombay Nursing Council was constituted in 1935. In 1949, Indian Nursing Council (INC) was established to maintain a uniform standard of training for nurses, midwives and health visitors and regulate the standards of nursing in India. INC act was passed in 1947 that was amended in 1950 and 1957. General Nursing and Midwifery (GNM) syllabus was revised in 1951, 1965, and 1986, ANM in 1974 and B.Sc. in 1981.

The nursing scenario at the time of independence was not bright and there were about 7000 nurses for the population of 400 million. The hospitals were grossly understaffed, nursing lacked professional and social status, and the working and living conditions of nurses were far from satisfactory. The low status can be attributed to the low socio economic status of Indian women and nursing is primarily a women’s profession. In the fifties, more number of girls from different parts of the country joined nursing and slowly there are more entrants from better socioeconomic status. By 2000, nurses’ colony at Delhi was built by Central government; nursing advisor post was instituted at the national level; three nursing posts were increased to five with the introduction of Asst. Director General Nursing and Dy. Asst. Director General. The College of Nursing PGI, Chandigarh and College of Nursing, CMC Vellore were designated as WHO collaborating centers for nursing and midwifery development in 2003.

The development of various committees such as Bhore Committee (1943), Shetty Committee (1954), Mudaliar Committee (1959-61), Kartar Singh Committee (1973), Srivastava Committee (1974), High Power Committee (1987) alongside five year plans have brought about a transition in the status of nursing and midwifery. The recommendations made were in relation to staffing in hospital nursing service, public health settings, and schools/colleges, working and living conditions, infrastructure and equipment, regulations, and intensification of training programmes to meet the staff shortage. The reports of the above mentioned Committees and National Health Policy (NHP, 2002) have put forward very sound recommendations for nursing management capacity. The NHP laid emphasis on improving the skill-level of nurses and on increasing the ratio of degree-holding nurses vis-à-vis diploma-holding nurses. It also recognized the need for establishing training courses for super-speciality nurses required for tertiary care institutions. However, gap existed in actual implementation. This required a strong support at the policy level to ensure implementation of key recommendations.

Following independence, reorganization of the health services took place in the light of the Bhore Committee recommendations (1946). Health services were provided in the rural areas through the establishment of primary health centre (PHC) as a basic unit to provide an integrated curative and preventive health care for the population of 30,000 in the plains (20,000 in hilly areas). The staffing pattern of the PHC was not implemented fully as per the Bhore Committee with regard to nursing until now. As per the Bhore committee’s recommendations, the nursing staff of PHC includes Public health nurses – 4, Institutional nurse -1, Midwives – 4 and Trained Dais – 4. In 1952, a post-certificate Public Health Nursing programme was instituted at the college of Nursing, New Delhi and later transferred to All India Institute of Hygiene and Public Health, Calcutta. Community health nursing was integrated in the curriculum of GNM and BSc Nursing courses.

From 1977-till date, with the introduction of Multipurpose Health Worker’s Scheme following Kartar Singh’s Committee report in 1973, most of the categories of staff under various unipurpose programmes were re-designated for multipurpose work. Until recently, most of the health services in the homes were provided by the Health workers, health visitors, ASHAs and Trained Dais whose activities were and are still concerned primarily with maternity and child welfare. The auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM) gradually replaced the Dais to serve in the village through the primary health centre and its sub-centres. Under NRHM scheme in 1996, every PHC was manned with 2 staff nurses to provide RCH services. In 1977, the Indian Nursing Council revised the curriculum for ANM course, in order to prepare candidates with high school certificate as Health workers (Female) and Health workers (Male) under the multipurpose health workers’ scheme. The formulation and adoption of the global strategy for “Health for All” by the 34th World Health Assembly in 1981 through Primary Health Care approach got of a good start in India with the theme “Health for All” by 2000 AD. In 1987, The Government of India appointed a High Power Committee on Nurses and Nursing Profession to go into the working conditions of nurses, nursing education and other related matters and submitted manpower requirements for nursing personnel.

Contemporary Perspectives

The current healthcare environment is dramatically different from the past and it is the health system that shapes the educational system and pathways. The complexity of the healthcare influenced by the increasing longevity, shortening of hospital stays, scientific and technological advances, equality, poverty, discrimination, disasters, violence and cultural diversity leads to several challenges that threaten the health and wellbeing of the Indian Population. Currently India has only 0.7 doctors (Global average is 1/1000) and 1.7 nurses (Global is 2.5/1000) available per thousand population. The ratio of hospital beds to population in 0.98/1000 against the global average of 3.5 beds/1000 population (WHO). India stands at 67th rank against 133 developing countries with regard to number of doctors and 75th rank with respect to number of nurses. The Physician Nurse ratio is not satisfactory. Thus, International Nurse is 1:3 whereas India is having 1:1. The country needs 2.4 million nurses to meet the growing demand (FICCI report, 2016). The HLEG (High Level Expert Group) group report on UHC (Universal health coverage India) 2011 is increased reliance on a cadre of well- trained nurses, which will allow doctors to focus on complex clinical cases.

The roles of nurses are evolving and changing. Nurses can perform health assessment, actively support patients and families in all settings, create innovative models of care, and enhance work processes to raise quality, lower cost and improve access for our society. Nurses can undertake research to find evidence to support new nursing interventions. Nurses can contribute towards strengthening systems to work efficiently in interdisciplinary teams. They can effectively participate and influence policies related to nursing at local, state and national levels. There is a rising demand in terms of manpower for tertiary and quaternary care, which requires specialized and highly skilled resources including doctors, nurses and other paramedical staff. This is also emphasized in NHP 2017. As a result, the demand for trained manpower, especially nurses will continue to increase every year. The number of registered nurses/midwives was 6.7 lakhs in 1998 and has reached 17,91,285 nurses/midwives in 2014.

In India, nursing educational programs such as Auxiliary Nurse Midwifery, General Nursing and Midwifery, BSc(N), MSc(N), MPhil and PhD(N) exist. INC prescribes uniform standards and syllabi for every educational program to be implemented across the country. However, the implementation by educational institutions having varied capabilities is not uniform resulting in graduates with varying knowledge, attitude and competencies. The last syllabus revision for ANM was done in 2012-13, GNM 2015-16, B.Sc- 2006, PBBSc- 2006 and M.Sc 2008. The growth in nursing educations is phenomenal. From 2000 to 2016, ANM schools have increased from 298 to 1927, GNM schools from 285 to 3040, B.Sc colleges from 30 to 1752, and M.Sc colleges from10 to 611. Although the increase is significant still there is gap between demand and supply. The 12th five-year plan suggested establishing 24 centers of excellence in nursing. The HR efforts included up gradation of schools to colleges, strengthening of existing schools, faculty development, and establishment of 6 AIIMs like institutions.

Some of the INC initiatives and achievement include capacity building of 55 nursing educational institutions, training of 1,20,000 nurses and 3500 faculty in HIV/AIDS & TB through GFATM project. E Learning module was developed as a result of this project. A Live register is being developed for all categories of nurses. Every registered nurse will be provided with a nurse unique ID (NUID). The register will lead to development of a nurse tracking system across the country and aid in reciprocal registration alongside renewal of license linked with CNE. INC has become a member of ICN. A national consortium for PhD in nursing was constituted by INC in 2006 in collaboration with Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences. The main objective is to promote research activities in various fields of nursing. The total number of research scholars enrolled in 12 batches is 268 and 74 have been already awarded Phd degree. There are 8 PhD study centers now namely INC, New Delhi, St John’s College of Nursing, Bangalore, CMC College of Nursing, Vellore, CMC College of Nursing, Ludhiana, Govt College of Nursing, Hyderabad, Govt College of Nursing, Thiruvananthapuram, Govt College of Nursing, SSKM Kolkata, and INE, Mumbai. INC is in collaboration with JHPIEGO has taken initiative to strengthen the foundation of pre-service education resulting in better prepared service provider. In order to promote competency based training INC in collaboration with JHPIEGO is going to set up state of the art simulation center in India.

There is a scope for improving living and working conditions of nurses in the future. Through the efforts and representation by TNAI, Supreme Court has recommended minimum salary of 20,000 per month as starting salary of a staff nurse in private hospitals. Some states have developed mechanism to conduct and record CNE through State nursing councils. Integration of service and education model that is practiced in CMC Vellore is also introduced in a few more institutions particularly in St Johns College of Nursing, Bangalore. INC is in the process of developing a practical model for the country. Florence Nightingale awards instituted by MOH & FW in 1973 to recognize and honor the meritorious services of outstanding nursing personnel in the country are given to 35 nurses every year on May 12, the International Nurses Day. This award includes a medal, certificate, citation and cash award of Rs. 50,000/-.

Some of the top nursing colleges in India today are established in the earliest days and are continuing to maintain standards and quality of education. AIIMS College of Nursing Delhi, CMC College of Nursing Vellore, RAK College of Nursing Delhi, SNDT College of Nursing Mumbai, NIMHANS Bangalore, Manipal College of Nursing Manipal, PGI College of Nursing Chandigarh, AFMC College of Nursing Pune, , BM Birla College of Nursing, Kolkata, , St John’s Bangalore, Govt College of Nursing Thiruvananthapuram, CMC College of Nursing Ludhiana, Father Muller College of Nursing Mangalore, Sri Ramachandra Medical University College of Nursing Chennai, and Apollo College of Nursing, Chennai are some of the top colleges of Nursing today. Many universities are running PhD programmes in nursing and many colleges have been recognized as research departments.

Public Health Nursing

According to the Indian Nursing Council (Snapshots, 2016), 789,740 ANMs and 56,096 LHVs are registered in the different state nursing councils of the Country. About 2.00 lakh ANMs (Auxiliary nurse midwives) and thousands of female health supervisors and public health nurses are working in the public health sector alone. They are responsible for implementing all national and state health programmes at ground level. Critical activities related to maternal and child health, disease control, immunization, epidemic management and health promotion are carried out by peripheral public health nursing personnel. The training of public health nursing personnel varies widely ranging from a broad multipurpose training of less than two years for ANMs to six years education at university level to prepare community health nursing specialists. Currently, community health nursing is offered as a subject in the ANM, GNM (general nursing and midwifery), post-basic B.Sc. Nursing, regular four-year B.Sc. Nursing and M.Sc. Nursing.

The scope of public health nursing is wide in India and their potentials are not fully utilized in our country. Currently, public health nurses at PHC, Block and district levels plan, monitor, and mentor peripheral health staff to implement programmes on health promotion and disease prevention. The Bhore Committee gave a strong recommendation for introduction of public health nurses and the Mudaliar Committee reiterated this. Rather than moving forward into a professional cadre, public health nursing in India became stagnant at the lowest level of ANM due to the political and economical reasons. Shortage of nurses and its impact on the Indian health care delivery system remains a major concern to this day. Adding to the above problem, there is an undersupply of competent public health nurses who are willing to serve in the resource-limited community health care settings.

Future Perspectives

The future of healthy India lies in mainstreaming the health agenda in the framework of the sustainable development and strengthening primary, secondary and tertiary care services to serve the rural (70%) and urban (30%) population. NHP 2017 recommends setting up new Medical Colleges, Nursing Institutions and AIIMS in the country by the government, standardization quality of clinical training, revisiting entry policies into educational institutions, ensuring quality of education, continuing nursing education and on the job support to providers, especially those working in rural areas using digital tools and other appropriate training resources, strengthening human resource governance, regulation of practice, establishing cadres like Nurse Practitioner and Public Health Nurses, specialty training for tertiary care, nursing school/college for 20-30 lakh population, HR policy for faculty, centers of excellence in nursing in each state, career progression to nursing cadre and posting of regular nurses to sub-center in the state where adequate nursing institutions are present. The policy also recommends the use of mid-level service providers to provide comprehensive primary care to the rural community through Health and Wellness centers/Sub centers. Nurses can assume this role provided they undergo a six month bridge course.

In the light of the above recommendations pertaining to nursing and nursing education, INC has prepared curriculum for Nurse Practitioner (NP) programmes in Critical Care and primary care. NP in Critical Care (NPCC) programme is commencing from 2017 and NP in Primary Health Care (NPPHC) from 2018. Both are residency programs aimed at providing clinical training at the real practice settings. State governments are communicated by central government to create posts for nurse practitioners at the state level. The revision of existing BSc and MSc curriculum are being planned to integrate competency based education approach and the process has just begun. The regulation of nursing education and practice will be strengthened through Nursing Practice Act (NPA) for which INC at the direction of the MOH &FW has started the preparation and soon it will be ready. National license exit exam for entry into practice, periodic renewal of license linked with continuing nursing education, and completion of live register are some of the future activities.

Studies of nursing practice have demonstrated that better patient outcomes are achieved in hospitals and community staffed by a greater proportion of nurses with a baccalaureate degree (Benner, Sutphen, Leonard, & Day, 2010). Phasing out diploma programme and making BSc as entry level is being dialogued and this might become a reality in the future too. The WHO strategic directions for nursing and midwifery (SNDM) 2011 – 2015 provide stakeholders with a framework for collaborative action with the vision statement “Improved health outcome for individuals; families and communities through provision of competent, culturally sensitive, evidence based nursing and midwifery services. This should become the future for nursing.

Bibliography

Benner, P., Sutphen, M., Leonard, V., & Day, L. (2010). Educating nurses : A call for radical transformation. Danvers, MA: Wiley

- – FICCI Report, 2016

- – Indian Nursing Council, 2016

- – Indrani,TK (2004). History of Nursing, New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers

- – National Health Policy, 2002 & 2017

- – Trained Nurses’ Association of India (2001). History and Trends in Nursing in India, New Delhi: TNAI

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

SHADOW OF DIVYANGJAN: Empowering Nation through Rehabilitation & Technology

AYJNISHD(D): Accelerating Development and Innovation Through an Inclusive Collaborative Rehabilitation Approach for Empowerment of Persons with Speech and Hearing Disabilities

SVNIRTAR: TO BOOST COMMUNITY BASED REHABILITATION FOR DISABLED THROUGH RESEARCH AND TRAINING

Fulfilling “Make in India” Aspirations : TDB

NRDC bringing the fruits of National R&D for Socio-economic development of the Country

Child Health in India

Health watch, how to recognise and manage diabetes: dr. anoop misra, director, diabetes foundation of india(dfi), yogic management of backache (backpain), dental implants: prof. yatish agarwal, health columnist, health initiative, food fortification: journey towards micro nutrient deficiency free india, notto taking steps towards saving lives: prof. vimal bhandari, director, notto, national health portal in transforming health sector, latest news.

Mental Health Rehabilitation Helpline ‘KIRAN’ 24×7 Toll-Free (1800-599-0019) Launched.

India celebrates ‘Janaushadhi Diwas’ on 7th March across India for Use...

Swasth Bharat Yatra spreads the message of ‘Eat Safe, Eat Healthy...

Govt launches affordable sanitary napkin under PMBJP towards women hygiene, safety

January 4: World Braille Day, January 9: NRI Day, January 10: World Hindi Day, January 12: National Youth Day, January 15: Army day, January 24: National Girl Child Day, January 25: National Voters day, January (last Sunday): World Leprosy Eradication Day, February 4: World Cancer Day, February 6: International Day of Zero Tolerance to Female Genital Mutilation, February 7: Safer Internet Day (second day of the second week of February), February 10: National De-worming Day, February 12: National Productivity Day, February 13: World Radio Day, February 14: Valentine Day, February 20: World Day of Social Justice, February 21: International Mother Language Day, February 24: Central Excise Day, February 28: National Science Day, March 1: Zero Discrimination Day, March 3: World Wildlife Day, National Defence Day, March 4: National Security Day, March 8: International Women’s Day, March 13: No Smoking Day (second Wednesday in March), March 15: World Disabled Day; World Consumer Rights Day, March 18: Ordnance Factories Day (India), March 21: World Forestry Day; World Down Syndrome Day, March 22: World Day for Water, March 23: World Meteorological Day, March 24: World TB Day, March 27: World Theatre Day, April 2: World Autism Awareness Day, April 5: International Day for Mine Awareness; National Maritime Day, April 7: World Health Day, April 10: World Homeopathy Day, April 11: National Safe Motherhood Day, April 17: World Haemophilia Day, April 18: World Heritage Day, April 23: World Book and Copyright Day, April 24: National Panchayati Day, April 29: International Dance Day, May 1: Workers’ Day (International Labour Day), Maharashtra Day, May 3: Press Freedom Day, May (1st Sunday): World Laughter Day, May (1st Tuesday): World Asthma Day, May (2nd Sunday): Mother’s Day, May 4: Coal Miners’ Day; International Fireghters Day, May 7: World Athletics Day, May 8: World Red Cross Day, May 9: World Thalassaemia Day, May 11: National Technology Day, May 12: International Nurses Day, May 15: International Day of the Family, May 17: World Telecommunication Day; World Hypertension Day, May 18: World AIDS Vaccine Day, May 22: International Day for Biological Diversity, May 24: Commonwealth Day, May 31: Anti-tobacco Day, June 1: World Milk Day, June 4: International Day of Innocent Children Victims of Aggression, June 5: World Environment Day June (3rd Sunday): Father’s Day, June 8: World Ocean Day, June 12: Anti-Child Labor Day, June 14: World Blood Donor Day, June 20: World Refugee Day,June 21: International day of yoga, June 26: International Day against Drug Abuse and Illicit Tracking, July 1: Doctor’s Day, July 6: World Zoonoses Day, July 11: World Population Day, August (1st Sunday): International Friendship Day, August 6: Hiroshima Day, August 8: World Senior Citizen’s Day, August 9: Quit India Day, Nagasaki Day, August 15: Indian Independence Day, August 18: IntI. Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, August 19: Photography Day, August 29: National Sports Day, September 2: Coconut Day, September 5: Teachers’ Day; Sanskrit Day, September 8: International Literacy Day, September 15: Engineers’ Day, September 16: World Ozone Day, September 21: Alzheimer’s Day; Day for Peace & Non-violence (UN), September 22: Rose Day (Welfare of cancer patients), September 26: Day of the Deaf; World Contraception Day, September 27: World Tourism Day, September 29: World Heart Day, September: world rivers day (last Saturday of September), October 1: International Day for the Elderly, October 2: Gandhi Jayanthi; International Day of Non-Violence, October(rst Monday): World Habitat Day, October 4: World Animal Welfare Day, October 8: Indian Air Force Day, October 9: World Post Oce Day, October 10: National Post Day; World Mental Health Day, October 2nd Thursday: World Sight Day, October 13: UN International Day for Natural Disaster Reduction, October 14: World Standards Day, October 15: World Students Day; World White Cane Day (guiding the blind), October 16: World Food Day, October 24: UN Day; World Development Information Day, October 30: World Thrift Day, November 5: World tsunami day, November 7: National Cancer Awareness Day, November 9: Legal Services Day, November 14: Children’s Day; Diabetes Day, November 17: National Epilepsy Day, November 20: Africa Industrialization Day, November 21: World Television Day, November 29: International Day of Solidarity with Palestinian People, December 1: World AIDS Day, December 2: National Pollution Control, December 3: World Day of the Handicapped, December 4: Indian Navy Day, December 7: Indian Armed Forces Flag Day, December 10: Human Rights Day; IntI. Children’s Day of Broadcasting, December 11: International Mountain Day, December 14: World Energy Conservation Day, December 16: Vijay Diwas, December 18: Minorities Rights Day (India), December 22: National Mathematics Day, December 23: Kisan Divas (Farmer’s Day) (India), December 24: National Consumers Day, December 25: Christmas Day

LEVERAGING ICT FOR ACCESS TO QUALITY HIGHER EDUCATION IN INDIA: UGC’S...

- Open access

- Published: 06 March 2024

Factors Associated with Nursing Professionalism: Insights from Tertiary Care Center in India

- Poonam Kumari 1 ,

- Surya Kant Tiwari ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4718-0398 2 ,

- Nidhin Vasu 1 ,

- Poonam Joshi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7016-8437 3 &

- Manisha Mehra ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7699-947X 4

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 162 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

380 Accesses

Metrics details

Professionalism among nurses plays a critical role in ensuring patient safety and quality care and involves delivering competent, safe, and ethical care while also working with clients, families, communities, and healthcare teams.

Aims and objectives

To assess the level of nursing professionalism and the factors affecting professionalism among nurses working at a tertiary care center in India.

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted from October 2022 to March 2023 using a total enumeration sampling technique. Following institutional ethics committee approval, standardized tools were administered consisting of Nursing Professionalism Scale and socio-demographic, personal, and organizational characteristics.

A total of 270 nurses participated, with a response rate of 93.7%. The mean age of the participants was 27.33 ± 2.75 years, with the majority being female (82.6%) and belonged to the age group of 23–27 years (59.6%). More than half of the nurses exhibited high professionalism (53%), with the highest and lowest median scores for professional responsibility (29.0) and valuing human beings (13.0) respectively. Multivariate regression analysis demonstrated that, compared with their counterparts, nurses with a graduate nursing qualification (AOR = 4.77, 95% CI = 1.16–19.68), up-to-date training (AOR = 4.13, 95% CI = 1.88–9.06), and adequate career opportunity (AOR = 33.91, 95% CI = 14.48–79.39) had significant associations with high nursing professionalism.

Conclusion/Implications for practice

The majority of the nurses had high professionalism, particularly in the domains of professional responsibility and management. Hospitals and healthcare institutions can use these findings to develop policies and prioritize opportunities for nurses to attend conferences and workshops to enhance their professional values, ultimately leading to improved patient care outcomes.

Patient and public contribution

No patient or public contribution.

The study addresses the issue of nursing professionalism in a rapidly evolving healthcare landscape, emphasizing its crucial role in ensuring patient safety and quality care.

More than half of the nurses reported having high levels of professionalism. Professional qualifications, up-to-date training, and career opportunities were identified as key factors associated with high nursing professionalism.

The findings can serve as a foundation for developing policies and programs aimed at improving professionalism among nurses, with potential implications for patient outcomes.

The emphasis on the significance of professional qualifications and up-to-date training suggests the need for continuous education and training programs to enhance nursing professionalism.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

In the rapidly evolving healthcare landscape [ 1 ], professionalism among nurses plays a pivotal role in ensuring patient safety and quality care. The nursing profession has undergone a transformation, especially since the onset of the pandemic, evolving from a job into a profession marked by precision and professional independence.

Nursing, as a profession, is characterized by a set of dynamic values, dedication, obedience, commitment to societal betterment, unwavering ethical values, and a strong sense of accountability and responsibility [ 2 , 3 ]. It involves delivering competent, safe, and ethical care while collaborating with clients, families, communities, and healthcare teams.

Professionalism in nursing is guided by a multifaceted set of values that forms the foundation for nurses’ knowledge and practice [ 4 ]. This professionalism extends beyond technical competence and is rooted in ethical decision-making and adherence to practice guidelines and standards [ 5 , 6 ].

Few studies have revealed lacunae in applying the code of ethics in nursing practice among nurses and nursing students [ 7 , 8 ]. Furthermore, a systemic review has indicated that a poorly perceived nursing profession can lead to poor patient outcomes [ 9 ]. Several studies have revealed a gap between personal and professional values among nursing professionals [ 10 , 11 ], emphasizing the need to integrate professional values into nursing education. These discrepancies can significantly impact patient outcomes and influence nurses’ intention to leave the profession [ 12 ].

Thus, there is an urgent need to assess the level of professionalism and its associated factors among nurses. In India, until recently, only a few studies have explored nurses’ perspectives on professionalism. Therefore, we aimed to assess the level of professionalism and explore the factors affecting professionalism among nurses in a tertiary care center, which represents a first step in developing policies and programs for nurses.

Study design and setting

An institutional-based descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted from October 2022 to March 2023 to measure the level of professionalism and associated factors among nurses working at a tertiary care center in Eastern India using a total enumeration sampling technique.

Study participants

The source population for this study consisted of nurses employed in the hospital. The study population included all nurses who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate. The inclusion criteria consisted of nurses working in the hospital and available during data collection; those with less than 6 months of working experience were excluded from the study. We distributed a Google Form link to 288 registered nurses via WhatsApp and Gmail to complete the questionnaires. We received responses from 270 nurses, resulting in a response rate of 93.7%. The final data were collected from the pilot study.

Ethical considerations

The Institutional Ethics Committee of the procuring institute reviewed the protocol, and permission was granted to carry out the study vide no- IEC/AIIMS/Kalyani/Meeting/2022/46 dated 22/07/2022. All participants were informed about the purpose of the study and their participation was completely voluntary. Written informed consent was obtained from all the eligible participants. The participants were also assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of the obtained information.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated using the formula; n = Z² P (1 − P)/d². Considering the prevalence of high professionalism among nurses (P) as 68.6% [ 23 ] at a 95% confidence interval (Z = 1.96) with a 6% maximum allowable error (d). By inserting these values into the formula, we got a calculated sample size of 235. Furthermore, for a 10% nonresponse rate, the required sample size was set to 260.

Tool I consisted of sociodemographic, personal, and organizational characteristics such as age, gender, marital status, working experience, personal and job satisfaction, effective interpersonal relationships with patients and healthcare teams, up-to-date training, career opportunities, location of the institute, and satisfaction with the work schedule.

Tool II comprises a 38-item Nurse Professionalism Scale, initially developed by Braganca et al. [ 28 ], which assesses the professional behavior of nurses while performing roles and responsibilities related to the patient care activities on a five-point Likert scale (0 = Not Applicable; 1 = Never; 2 = Rarely; 3 = Sometimes; 4 = Mostly; 5 = Always). This scale includes six domains: professional responsibility and accountability, nursing practice, communication, and interpersonal relationships, valuing human beings, management, and professional advancement with total scores ranging from 0 to 190. A score ≥ 115 indicated high professionalism, 77–114 indicated moderate professionalism and a score less than 77 indicated low professionalism. The Cronbach’s alpha for nursing professionalism in the present study was 0.97.

Statistical analysis

The collected data were checked for completeness and accuracy before analysis and then coded and summarized in the master data sheet. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Software version 26.0 utilizing both descriptive and inferential statistics. For descriptive statistics, the frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation, and range were calculated. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to evaluate the normality of the distribution of the outcome variables. Due to the nonnormal distribution, nonparametric tests (Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis H) were used to compare means. Binary and multivariable logistic regression analyses were carried out to identify factors associated with nursing professionalism. Model fitness was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test ( p = 0.83), which indicated a well-fitted model. Additionally, all variables satisfied the chi-square assumption, and their odds ratios were examined. To assess multicollinearity among continuous variables, variance inflation factor (VIF) values were computed and found within the acceptable range (1 to 2), confirming the absence of multicollinearity. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were employed to identify factors associated with outcome variables. Variables with a p-value less than 0.2 in the bivariable analysis were included in the multivariable analysis. Significant associations with outcome variables were determined based on a p-value less than 0.05 with a 95% confidence interval.

The mean age of the nurses was 27.33 ± 2.75 years, with the majority belonging to 23–27 years age group (59.6%), female (82.6%), unmarried (70.4%), and having professional experience of 2 to 5 years (47.4%). Furthermore, the majority of participants reported satisfaction with their current job (67.8%), the location of the institute (66.7%), and work schedule (80.7%). (Table 1 )

Table 2 shows the level of nursing professionalism among the participants. More than half of the nurse participants exhibited high nursing professionalism (53%), while approximately one quarter had moderate (23.0%) or low nursing professionalism (24.0%).

The total median score (Q1-Q3) for professionalism among nurses was 120.50 (77.7–146.0). The highest median score was observed in the area of professional responsibility (29.0), followed by management (28.0), while relatively lower scores were observed in the domains of communication and interpersonal relationships (13.0) and valuing human beings (13.0). (Table 3 )

Table 4 shows the mean differences in nursing professionalism according to sociodemographic, personal, and organizational variables. There was a significant difference in the mean rank between professional qualification, job satisfaction, and career opportunity and nursing professionalism scores.

Table 5 depicts the factors associated with nursing professionalism for the study variables. According to our multivariable regression analysis, three variables, professional qualification, up-to-date training, and career opportunity, demonstrated significant associations with high nursing professionalism. Similarly, compared with those with a diploma, nurses with a graduate nursing qualification had 4.77 times greater odds of having high nursing professionalism (AOR = 4.77, 95% CI = 1.16–19.68). Furthermore, nurses who had received up-to-date training had 4.13 times greater odds of having high professionalism (AOR = 4.13, 95% CI = 1.88–9.06), while those with adequate career opportunities exhibited substantial 33.91 times greater odds of having high nursing professionalism (AOR = 33.91, 95% CI = 14.48–79.39) than did their counterparts.

This study focused on the level of professionalism among nurses and associated factors among 270 nurses working in a tertiary-level hospital in India. The results showed that more than half of the nurse participants exhibited high levels of professionalism, with variations across different domains. Professional qualifications, up-to-date training, and career opportunities were identified as key factors associated with high professionalism among nurses.

Nursing professionalism is a global concern, with variations observed across different countries and healthcare systems. The findings of our study revealed that more than half of the nurses had high professionalism, which was in line with the findings of various studies conducted in Ethiopia [ 6 , 21 ]. This high level of professionalism in our study participants can be attributed to younger age, adequate staffing ratio, resource availability, job security, and support for professional development opportunities in our institute, which could impact nurses’ motivation, job satisfaction, and, consequently professionalism [ 22 ].

Nursing professionalism is multidimensional, dynamic, and culture-oriented [ 5 ]. It may be influenced by various organizational, educational, and societal factors, which can vary significantly across countries. Studies among Japanese and Ethiopian nurses reported low levels of professionalism among nurses [ 23 , 24 ]. Another study showed professionalism as a common factor influencing job satisfaction in Korean and Chinese nurses [ 25 ]. Iranian nurses’ attitude towards professionalism was reported to be at an average level [ 26 ].

In this study, the highest median scores were attributed to the subdomain of professional responsibility and management. In contrast, another study attributed high scores to subdomains such as ‘maintaining the confidentiality of the patient’ and ‘safeguarding the patient’s right to privacy’ [ 2 ]. A Korean study depicted that higher professionalism among oncology nurses may lead to higher compassion satisfaction and lower compassion fatigue [ 18 ].

One of the interesting findings of our study is that nurses with more than 5 years of experience had higher mean scores on professionalism, which is supported by various studies that revealed high professionalism among highly experienced nurses [ 19 , 26 ]. On the other hand, a recent survey in India indicated that nurses with fewer years of experience exhibited greater professional values compared to their more experienced counterparts [ 3 ].

Professionalism in nursing practice is important for ensuring patient safety, quality care, and positive healthcare outcomes. Another intriguing finding of this study is that participants who are personally and job-satisfied and have effective interpersonal relationships with patients attain higher professional median scores. These finding aligns with those of other studies indicating that nurses who are satisfied with their peers have greater job satisfaction and, consequently greater professional value [ 11 , 20 ].

Multivariate regression analysis revealed that professional qualifications, up-to-date training, and career opportunities were significantly associated with nursing professionalism. A previous study showed that nurses with a diploma qualification exhibited high professionalism scores [ 19 ]. This finding contrasts with the present study, which demonstrated that nurses with a graduate degree exhibited high levels of professionalism. Other studies have noted that age, number of years of experience, and length of service significantly contribute to the nursing profession [ 6 ].

Continuous education plays a significant role in making learning more concrete, helping in pouring professional values and fostering deeper commitment to the profession [ 13 ]. Another major finding of this study is that nurses who have undergone up-to-date training exhibit higher levels of nursing professionalism, which has been supported by several studies [ 2 , 14 , 15 ]. These findings may be attributed to the continuous enrichment of knowledge and values through participation in conferences and workshops after graduation [ 16 ].

In our study, we did not find any influence of gender on nursing professionalism. In contrast, a study reported that female nurses had high professionalism [ 23 ]. This discrepancy could be due to differences in participant characteristics, such as professional qualification, age, educational attainment, location, and study period [ 17 ]. A recent study illustrated that nursing professionalism plays a mediating role in the relationship between self-efficacy and job embeddedness [ 27 ].

This comprehensive study provides valuable insights into the factors influencing nursing professionalism, covering various dimensions, such as sociodemographic, personal, and organizational factors. Additionally, we used validated tools for data collection and managed to acquire an adequate sample size with high response rates.

Limitations of the study

Our study has several limitations. The cross-sectional study design and single time point data do not allow for the examination of changes or trends over time. In addition, self-report bias may be introduced due to self-administered questionnaires and convenience sampling may introduce selection bias.

Clinical practice relevance

Our findings have important implications for redefining the roles of nurses in India to be more in line with those in Western countries. In Western countries, individuals are prioritized for continuous education and training, and nurses often have higher educational qualifications, and clear career paths with opportunities for specialization and advancement, which are associated with greater professionalism. Redefining the roles of nurses in India might involve establishing and promoting up-to-date training programs and encouraging the pursuit of advanced degrees. Policies in India could include support for attending conferences, workshops, and international collaborations, practices common in Western countries. Such alignment may improve patient care standards, increase professional satisfaction among nurses, and enhance healthcare outcomes in India.

Conclusions

To conclude, more than half of the nurse participants displayed high professionalism, particularly in domains related to professional responsibility and management. Factors associated with nursing professionalism include professional qualifications, up-to-date training, and career opportunities.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Tehranineshat B, Torabizadeh C, Bijani M. A study of the relationship between professional values and ethical climate and nurses’ professional quality of life in Iran. Int J Nurs Sci. 2020;7(3):313–9.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Poorchangizi B, Borhani F, Abbaszadeh A, Mirzaee M, Farokhzadian J. Professional values of nurses and nursing students: a comparative study. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):438.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Poreddi V, Narayanan A, Thankachan A, Joy B, Awungshi C, Reddy SSN. Professional and ethical values in nursing practice: an Indian perspective. Investig Educ En Enfermeria. 2021;39(2):e12.

Google Scholar

Hodges BD, Ginsburg S, Cruess R, Cruess S, Delport R, Hafferty F, et al. Assessment of professionalism: recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 conference. Med Teach. 2011;33(5):354–63.

Cao H, Song Y, Wu Y, Du Y, He X, Chen Y, et al. What is nursing professionalism? A concept analysis. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:34.

Fantahun A, Demessie A, Gebrekirstos K, Zemene A, Yetayeh G. A cross sectional study on factors influencing professionalism in nursing among nurses in Mekelle Public Hospitals, North Ethiopia, 2012. BMC Nurs. 2014;13(1):10.

Adhikari S, Paudel K, Aro AR, Adhikari TB, Adhikari B, Mishra SR. Knowledge, attitude and practice of healthcare ethics among resident doctors and ward nurses from a resource poor setting, Nepal. BMC Med Ethics. 2016;17(1):68.

Bijani M, Ghodsbin F, Javanmardi Fard S, Shirazi F, Sharif F, Tehranineshat B. An evaluation of adherence to ethical codes among nurses and nursing students. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2017;10:6.

Coster S, Watkins M, Norman IJ. What is the impact of professional nursing on patients’ outcomes globally? An overview of research evidence. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;78:76–83.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Donmez RO, Ozsoy S. Factors influencing development of professional values among nursing students. Pak J Med Sci. 2016;32(4):988–93.

Eskandari Kootahi Z, Yazdani N, Parsa H, Erami A, Bahrami R. Professional values and job satisfaction neonatal intensive care unit nurses and influencing factors: a descriptive correlational study. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2023;18:100512.

Tadesse B, Dechasa A, Ayana M, Tura MR. Intention to leave nursing Profession and its Associated factors among nurses: a facility based cross-sectional study. Inq J Med Care Organ Provis Financ. 2023;60:00469580231200602.

Boozaripour M, Abbaszadeh A, Shahriari M, Borhani F. Ethical values in nursing education: a literature review. Electron J Gen Med. 2018;15(3):em19.

Mlambo M, Silén C, McGrath C. Lifelong learning and nurses’ continuing professional development, a metasynthesis of the literature. BMC Nurs. 2021;20(1):62.

Poorchangizi B, Farokhzadian J, Abbaszadeh A, Mirzaee M, Borhani F. The importance of professional values from clinical nurses’ perspective in hospitals of a medical university in Iran. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18(1):20.

Price S, Reichert C. The importance of Continuing Professional Development to Career satisfaction and patient care: meeting the needs of novice to Mid- to late-Career nurses throughout their Career Span. Adm Sci. 2017;7(2):17.

Article Google Scholar

Tehranineshat B, Rakhshan M, Torabizadeh C, Fararouei M. Compassionate care in Healthcare Systems: a systematic review. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019;111(5):546–54.

PubMed Google Scholar

Jang I, Kim Y, Kim K. Professionalism and professional quality of life for oncology nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(19–20):2835–45.

Wynd CA. Current factors contributing to professionalism in nursing. J Prof Nurs off J Am Assoc Coll Nurs. 2003;19(5):251–61.

Fekonja U, Strnad M, Fekonja Z. Association between triage nurses’ job satisfaction and professional capability: results of a mixed-method study. J Nurs Manag. 2022;30(8):4364–77.

Abate HK, Abate AT, Tezera ZB, Beshah DT, Agegnehu CD, Getnet MA, et al. The magnitude of Perceived Professionalism and its Associated factors among nurses in Public Referral hospitals of West Amhara, Ethiopia. Nurs Res Rev. 2021;1121–30.<\/p>

Negussie BB, Oliksa GB. Factors influence nurses’ job motivation at governmental health institutions of Jimma Town, South-West Ethiopia. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2020;13:100253.

Bekalu YE, Wudu MA. Level of professionalism and Associated factors among nurses working in South Wollo Zone Public hospitals, Northeastern Ethiopia, 2022. SAGE Open Nurs. 2023;9:23779608231158976.

Tanaka M, Yonemitsu Y, Kawamoto R. Nursing professionalism: a national survey of professionalism among Japanese nurses. Int J Nurs Pract. 2014;20:(6):579–87.

Hwang JI, Lou F, Han SS, Cao F, Kim WO, Li P. Professionalism: the major factor influencing job satisfaction among Korean and Chinese nurses. Int Nurs Rev. 2009;56(3):313–8.

Shohani M, Zamanzadeh V. Nurses’ attitude towards professionalization and factors influencing it. J Caring Sci. 2017;6(4):345–57.

Kim Hjeong, Park D. Effects of nursing professionalism and self-efficacy on job embeddedness in nurses. Heliyon. 2023;9(6):e16991.

De Vaz A, Nirmala R. Nurse professionalism scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. 2020 [cited 2023 Oct 22]; Available from: http://irgu.unigoa.ac.in/drs/handle/unigoa/6401 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We express gratitude to all the study participants for their cooperation and devotion of time during the data collection period.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Nursing Services, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalyani, West Bengal, India

Poonam Kumari & Nidhin Vasu

College of Nursing, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raebareli, Uttar Pradesh, India

Surya Kant Tiwari

College of Nursing, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalyani, West Bengal, India

Poonam Joshi

College of Nursing, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna, Bihar, India

Manisha Mehra

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Study conception and design: PK, PJ, and MM designed the study, PK, NV, and PJ collected the data. SKT analysed the data and SKT, PJ, and MM drafted the manuscript. PK, SKT, NV, PJ, and MM review & editing the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Additionally, SKT and MM share the responsibility of corresponding the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Surya Kant Tiwari or Manisha Mehra .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate.

The Institutional Ethics Committee of All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalyani reviewed and approved the study vide IEC/AIIMS/Kalyani/Meeting/2022/46. Written informed consent was obtained from all the eligible participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kumari, P., Tiwari, S.K., Vasu, N. et al. Factors Associated with Nursing Professionalism: Insights from Tertiary Care Center in India. BMC Nurs 23 , 162 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01820-4

Download citation

Received : 16 January 2024

Accepted : 22 February 2024

Published : 06 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01820-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Patient safety

- Professionalism

- Regression analysis

- Tertiary care center

- Cross-sectional studies

BMC Nursing

ISSN: 1472-6955

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Paper Submission

- Testimonials

- Article Processing Charges

- Challenges faced by nurses in india the major workforce of the healthcare system

Submit manuscript...

Due to current covid19 situation and as a measure of abundant precaution, our member services centre are operating with minimum staff, eissn: 2572-8474, nursing & care open access journal.

Mini Review Volume 2 Issue 4

Challenges faced by Nurses in India-the major workforce of the healthcare system

Manju chhugani, merlin mary james function clickbutton(){ var name=document.getelementbyid('name').value; var descr=document.getelementbyid('descr').value; var uncopyslno=document.getelementbyid('uncopyslno').value; document.getelementbyid("mydiv").style.display = "none"; $.ajax({ type:"post", url:"https://medcraveonline.com/captchacode/server_action", data: { 'name' :name, 'descr' :descr, 'uncopyslno': uncopyslno }, cache:false, success: function (html) { //alert('data send'); $('#msg').html(html); } }); return false; } verify captcha.

Regret for the inconvenience: we are taking measures to prevent fraudulent form submissions by extractors and page crawlers. Please type the correct Captcha word to see email ID.

Department of Nursing, Rufaida College of Nursing, India

Correspondence: Merlin Mary James, Tutor, Rufaida College of Nursing, India, Tel +91-9971882433

Received: February 22, 2017 | Published: April 5, 2017

Citation: Chhugani M, James MM. Challenges faced by nurses in india-the major workforce of the healthcare system. Nurse Care Open Acces J. 2017;2(4):112-114. DOI: 10.15406/ncoaj.2017.02.00045

Download PDF

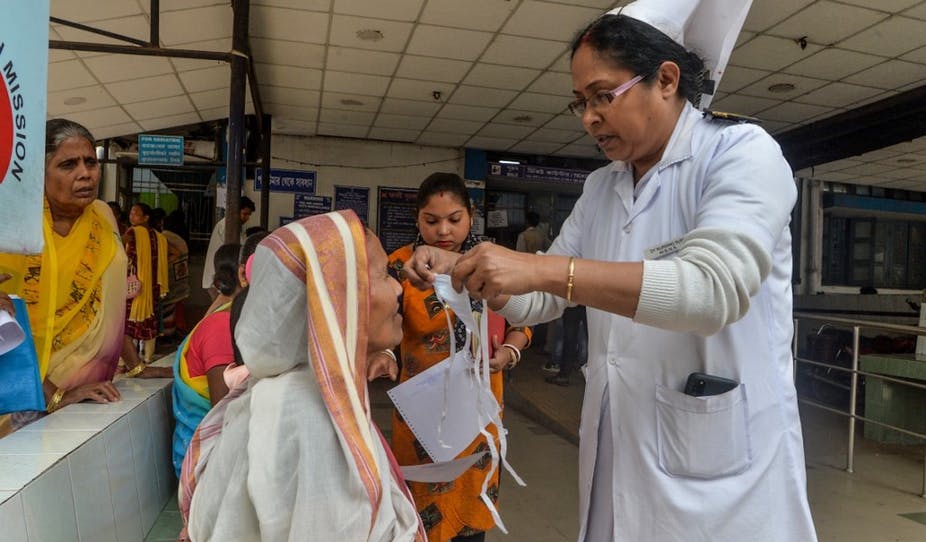

Nursing binds human society with a bond of care and affection. Nursing is a calling to care, which offers an oasis of poignant stories and pool of challenges. Despite of urbanization and globalization in India, the healthcare system in the country continues to face formidable changes. Nurses play an integral role in the healthcare industry, providing care to the patients and carrying out leadership roles in hospitals, health systems and other organizations. It is of paramount importance that all people everywhere should have access to a skilled, motivated and supportive nursing care within a robust healthcare system. The importance of nurses in healthcare should be underlined for attempting to create a better task force for better quality care for all. There are certain challenges which the Nurses in the present healthcare system face. These challenges arise due to issues at the organizational, state and national level. It is of utmost importance to first recognize and understand each and every possible challenge faced by the nurses in order to deal with them efficiently. Not just recognize and understand them but also find solutions to mitigate them.

Keywords: challenges, nurses and Healthcare system

Mini Review

Nursing binds human society with a bond of care and affection. Nursing is a calling to care, which offers an oasis of poignant stories and pool of challenges. The scope of nursing practice has expanded and extended to different settings other than hospital only. Nurses deal with the most precious thing in this wide world- ‘the human life’ . 1

Nurses are often the linchpin component across a wide continuum of care. A nurse’s professional skills and training contribute significantly to successful patient outcomes in a variety of care settings--from acute and tertiary care to prevention and wellness programs. 2 Their smiling face and compassionate touch and care provides great satisfaction to the patient.

Despite of urbanization and globalization in India, the healthcare system in the country continues to face formidable changes. The healthcare system has become increasingly detached from the curative aspect and more focusing on the satisfaction of material needs and enlarging the profit-earning aspects. This has led to unaffordability of the curative care to many common people due to the present framework of the healthcare system in the country. Subsequently the healthcare system is being plagued with various problems. The solution is to delve deeper into the roots of the problems and explore possible solutions to curb them.

Nurses play an integral role in the healthcare industry, providing care to the patients and carrying out leadership roles in hospitals, health systems and other organizations. Although nursing profession can be very rewarding but it is equally challenging and it entails a huge level of dedication and commitment. Nurses needs to be focused on not only the patient needs but also on the management of system of care. This often creates unfortunate hassles irrespective of how hard the nurse’s works towards patient care. They are coordinators and custodians of patient care. This entails lot of managerial skills where they need to possess apart from technical skills

Reduced workforce and lack of quality care leads to overburdened workforce which further leads to higher morbidity and mortality. It is of paramount importance that all people everywhere should have access to a skilled, motivated and supportive nursing care within a robust healthcare system. The importance of nurses in healthcare should be underlined for attempting to create a better task force for better quality care for all.

However, there are certain challenges which the Nurses in the present healthcare system face. These challenges arise due to issues at the organizational, state and national level. It is of utmost importance to first recognize and understand each and every possible challenges faced by the nurses in order to deal with them efficiently. Not just recognize and understand them but also find solutions to mitigate them.

In India, the healthcare system is undergoing a radical change and there are unmet health targets. The change is due to the change in demographics, advancement in medical technology, profit earning mentality, immigration, task shifting, education-service gap and economic recession to list a few. Subservient to medical fraternity even though long back it has been developed as profession (WHO). Nurses facilitate co-operation from other healthcare providers, for e.g., doctors, paramedical staff and other ancillary staff. There are several daunting challenges faced by nurses at workplace which leave them less efficient in rendering quality care to patients, thereby hoisting an unhealthy reputation to that particular healthcare setting.

Nevertheless, these challenges are arguably the primary motivators for nurses to leave their profession, less students opting for nursing profession, thereby contributing to staff shortage. They move to other countries as remuneration and working condition and respect better.

Challenges faced by nurses at workplace

Workplace mental violence

Workplace violence is widespread in healthcare settings. Huge amount of workload and responsibilities on the staff can often lead to disturbed mental peace which will ultimately lead to less efficient care. Multiple tasks can pose a problem in a healthcare unit. Workplace mental violence can be also in the form of threats, verbal abuse, hostility and harassment, which can cause psychological trauma and stress. At times verbal assault can escalate to physical violence. In a healthcare setting, the possible sources of violence include patients, visitors, intruders and even co-workers. From 2002 to 2013, incidents of serious workplace violence (those requiring days off for the injured worker to recuperate) were four times more common in healthcare than in private industry on average. Patients are the largest source of violence in healthcare settings, but they are not the only source. In 2013, 80 percent of serious violent incidents reported in healthcare settings were caused by interactions with patients. Other incidents were caused by visitors, co-workers, or other people. At many instances workplace violence is under-reported. 3

Shortage of staff

Deficient Manpower leads to unmanageable patient load and disparity in the Nurse: Patient ratio. Nurse: Patient ratio needs to be well maintained as it highly affects the patient care delivery system. When nurses are forced to work with high nurse-to-patient ratios, patients die, get infections, get injured, or get sent home too soon without adequate education about how to take care of their illness or injury. So they return right back to the hospital, often sicker than before. When nurses have fewer patients, they can take better care of them. 4 When there are sufficient number of nurses in a healthcare setting, the nurses have more time to advocate with the patients and their relatives about the plan of patient care and s/he can ensure that the patient gets everything s/he needs, and thereby patients are more likely to thrive in such situations.

Workplace health hazards

Nurses confront a high risk of developing occupational health hazards if not taken proper precautions and care. Nurses are confronted with a variety of biological, physical, and chemical hazards during the course of performing their duties. The level of occupational safety and health training and resources available to nurses, and the incorporation, implementation, and use of such training and resources with management support and leadership are critical factors in preventing adverse outcomes from the occupational safety and health hazards nurses are exposed to on a daily basis. 2

Long working hours

Short staffing pattern in a health care unit often results in long working hours and double shifts of staff nurses. It is evidently affecting the health of the nurses. It is quite difficult for a nurse to provide efficient nursing care with exhausted state of mind and body.

Lack of Synchronicity

Disharmony and lack of teamwork is an emerging challenge in the heath-care sector. Harmonious relationship amongst healthcare workers is an essential requirement for the healthcare system. Nurses bear the indirect opprobrium of every dreadful incident which occurs in the hospital. If the patient is not satisfied by the care rendered in the hospital, all the blame is accrued to the nurses, even if it is not her fault. Inadequacy in the care rendered may vary from ineffective medical care to non-availability of doctors, and yet nurses are being blamed. Non availability of equipment in hospital, which in turns affects the quality of care. Although the responsibility is not necessarily of nurses, yet nurses are ultimately responsible for patient care environment in their wards.

Lack of recognition

Hospitals must be safe places for sick folks and their nursing services carry responsibilities that are not always recognized. 1 There is no support system for nurses and hence their performances are usually not projected well. During inspections conducted in Hospitals by Medical Council of India and Indian Nursing Council, nurses play a vital role in all facilitations, and at the culmination of the inspections, the outcomes are not shared with them and they are not acknowledged for the work performed.

Non-nursing roles

In almost all healthcare settings, nurses undertake roles which are not of their forte, hence they are left with minimal time to carry out their actual roles and responsibilities. They are spending more time than necessary doing non-nursing-related work, for e.g., billing, record keeping, inventory, laundry, diet, physiotherapy, absconding of patient, etc., thereby diminishing time for patient care. If at any instance, there is any fault in these roles, the nurses have to bear the brunt of that in the form of cancellation of leaves, salary deductions etc., Very little efforts have been made in any jurisdiction to explicitly address this.

Solutions to curb the challenges

All the listed challenges are somehow interlinked and interdependent. It is necessary for us to look deep within these problems and to reach to the core of these challenges in order to find resolutions for the same.

Positive practice environment

Work environment: Work environment plays a large role in the ability of providing quality care. It impacts everything from the safety of patients and their caregivers to job satisfaction. There needs to be employer friendly work environment. Safety and security of the nurses should be given importance. To maximize the contributions nurses, make to society, it is necessary to protect the dignity and autonomy of nurses in the workplace. 5 A Healthy Work Environment is one that is safe, empowering, and satisfying. A culture of safety is paramount, in which all leaders, managers, health care workers, and ancillary staff have a responsibility as part of the patient centered team to perform with a sense of autonomy, professionalism, accountability, transparency, involvement, efficiency, and effectiveness. All must be mindful of the health and safety for both the patient and the health care worker in any setting providing health care, providing a sense of safety, respect, and empowerment to and for all persons. 6 Harmonious human relations and incentives in work settings may serve as motivation and encouragement for the nurses.

Equipment/materials : The availability and adequacy of samples of equipment and consumable supplies is often a matter of concern. Usually staff report that they are crippled by unavailability and inadequacy of certain equipment and supplies. The problems ranged from the inadequacy of life saving supplies and equipment including IV drugs adrenaline, oxygen and autoclaves to relatively cheap supplies including gauze and cotton wool. The hospital management should ensure at regular basis that the supplies and equipment are adequately available for the smooth functioning of the hospital.

Positive team work

A team needs to be taught about importance of team work and a good team can always conquer the goal of effective and quality patient care. It can also accelerate the focus on curative care of the patients.

Recruitment/retention policy

A proper and well planned policy for recruitment and retention has to be included in an organization in order to enhance the manpower for better support and care.

Closing education-service gap

Every heath care organization should be focusing on eradicating the difference between what is taught to the nurses during their study period and what is being done practically by them in hospitals. Practical and theoretical things of nursing aspects should be merged to an extent to close the education - service gap. Nursing colleges, year by year are strengthening their educational programs and their supervision in an effort to develop thoughtful nurses and to safeguard patients whom they tend. Students need to be taught reverence for human life, as tragedy lurks round every corner in a hospital-any hospital, good or bad and that price of safety is eternal vigilance. 1

Workload balance (Quality/Quantity)

Workload often leads to unwanted hassles and loss of mental peace which ultimately leads to less efficient care. An organization should try to balance the workload by distributing it equally among all the health care members so as to get the desired results out of a health care team.

Evidence based practice

Nurses should also deviate a part of their focus towards evidence based practice. Various practices have related researches which can be read by the nurses to see if that practice is actually effective or not. Regular reading of research articles and studying various experimental studies can improve the knowledge and practice of nurses and thus can have a huge positive effect of patient health care and curative care too Figure 1 .

Figure 1 Nursing Problems and solutions.

Patient and the public have the right to the highest performance from the healthcare professionals and this can only be achieved in a workplace that enables and sustains a motivated and well-prepared workforce. Catering to the needs of nurses and combating their challenges can make nurses empowered, encouraged, challenged and affirmed to continue doing what they do best without any barriers.

Acknowledgements

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

- Medical chivalry and team work. American Journal of Nursing . 1927;27(5):367.

- Ramsay, D James. A new look at nursing safety: The development and Use of JHAs in the emergency department. The Journal of Sh & e Research . 2005;2(2):1–18.

- https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3826.pdf

- http://www.truthaboutnursing.org/faq/short-staffed.html

- http://www.nursingworld.org/workenvironment

- http://www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/WorkplaceSafety/Healthy-Work-Environment

©2017 Chhugani, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the, Creative Commons Attribution License ,--> which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

Journal Menu

- Aims and Scope

- Editorial Board

- Reviewer Board

- Articles In Press

- Current Issue

- Article Processing Fee

- Journal Contact

Useful Links

- Submit Manuscript

- Author Guidelines

- Plagiarism Policy

- Peer Review System

- Terms & Conditions

- Editor Guidelines

- Associate Editor Guidelines

- Join as Editor

- Join as Associate Editor

- Reviewer Guidelines

- Publishing Process

- Join as Reviewer

- Withdrawal Policy

- Cover Letter-Manuscript Submission

- Template-Manuscript Submission

‘Nursing’ a Community into Marginalization: A Study on the Hardships Faced by Medical Nurses in India

It takes global catastrophes like the Covid-19 pandemic and World Wars to get people to realize how the marginalized community of medical nurses toils to safeguard a country’s civilians. It is disheartening that they are hailed as true soldiers only when a disaster strikes. This article aspires to throw light upon that fragment of the Indian nation which is often looked down upon and bring to the forefront the hardships the nursing professionals endure. It is recorded in tribute to Ms. Lini Puthusserry, the brave nurse who lost her life fighting the Nipah virus in Kerala.

The month of May 1942 saw the formation of the Women’s Auxiliary Corps (India) by the British. This welcomed female volunteers into the war front. This was a noteworthy step towards the recognition of women in combat roles which wasn’t possible up until then. However, civilian women had already taken up combat roles all across the globe by then. Women of the orient and occident were filling in as medical nurses many years prior to the formation of the Auxiliary Corps. Yes, being in a uniform had meant more than one thing.

In spite of being so intrinsically bound to the development of a nation, it is debatable whether nurses are given due credit as the man power of the Indian subcontinent. It becomes self-contradictory to explain the realms of injustice faced by this community which is largely constituted by women, in a language that is already gendered. India popularly perceives the profession of medical nurses as being inferior and undesirable, with very little scope for promotions or monetary gain. This also contributes to a commendable portion of professional nurses migrating overseas in search of better wages, working conditions, and respect. More often than not, Indian nurses are romanticized as angels during crises and forgotten once they settle down. This article will explore such discursive constructions and contradictions related to the nursing community of India that faces discrimination on multiple fronts.

An Interaction with an Indian Nurse

Following is a brief interaction with a medical nurse from a private hospital in Palakkad, Kerala (India). Both the nurse and the hospital management do not wish to reveal their identities, in fear of unwanted attention and bad publicity. In a few questions, the professional was able to reveal her apprehensions regarding her vocation and the hardships her community goes through on a regular basis.

How did you get into this profession?