Essay on Responsibility Of Youth

Students are often asked to write an essay on Responsibility Of Youth in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Responsibility Of Youth

Importance of youth responsibility.

Youth are the future. They have the power to shape the world. It’s important for them to understand their responsibilities. This includes caring for themselves, their families, and their communities. They should also respect the law and the rights of others.

Personal Responsibility

Youth have a duty to take care of their health. This means eating well, exercising, and avoiding harmful habits. They also need to focus on their education. Learning new skills can help them succeed in life.

Family Responsibility

Young people should help their families. They can do chores, take care of siblings, and support their parents. Family is a team, and everyone needs to do their part.

Community Responsibility

Youth should also help their communities. They can volunteer, clean up parks, or help neighbors. By doing these things, they can make their communities better places to live.

Respect for Law and Rights

Finally, youth must respect the law and the rights of others. They should follow rules and treat everyone with kindness. This helps create a peaceful society.

250 Words Essay on Responsibility Of Youth

Introduction.

Youth is a time of energy and potential. It is a time when we can shape our life. As young people, we have many responsibilities. These are not just to ourselves, but also to our families, our communities, and our world.

Responsibility to Self

The first duty of youth is to themselves. They must take care of their health and education. They should eat healthy food, exercise regularly, and get enough sleep. They should also study hard to gain knowledge and skills. This will help them to be successful in the future.

Responsibility to Family

Young people also have a duty to their families. They should respect their parents and elders. They should help with household chores. They should also care for their younger siblings. This helps to strengthen family bonds.

Responsibility to Society

Youth also have a role to play in society. They should be good citizens. They should obey laws and respect authority. They should also help those in need. This can be done by volunteering or donating to charity.

Responsibility to the World

Finally, youth have a responsibility to the world. They should care for the environment. They should also promote peace and understanding among different cultures and religions. This helps to make the world a better place.

In conclusion, youth have many responsibilities. By fulfilling these duties, they can make a positive impact. They can help to shape a better future for themselves and for everyone.

500 Words Essay on Responsibility Of Youth

Youth is a time of energy, growth, and potential. It is a period when we can shape our futures and influence our societies. As young people, we carry a great responsibility. This essay will explore the various responsibilities of youth.

Role in Society

Young people play a critical role in society. They are the leaders of tomorrow, and their actions today will shape the future. They have the responsibility to be informed about world events, local issues, and the needs of their communities. They must participate in social activities, volunteer work, and community service. By doing this, they can contribute to society and make the world a better place.

Education and Learning

Education is another key responsibility of youth. Young people must strive to learn and grow, not only in school but also in life. They should seek knowledge, develop skills, and cultivate curiosity. This will prepare them for future challenges and opportunities. They must also respect their teachers and peers, fostering a positive learning environment for all.

Health and Well-Being

Young people also have a responsibility towards their health and well-being. They should eat healthily, exercise regularly, and avoid harmful habits like smoking or excessive screen time. They should also take care of their mental health, seeking help when needed. By doing this, they can ensure a healthy and productive future.

Respect and Kindness

Respect and kindness are essential responsibilities of youth. Young people should treat others with dignity and respect, regardless of their background or beliefs. They should also show kindness and empathy towards others. This promotes harmony and understanding in society.

Environment Protection

Youth have a vital role in protecting the environment. They should be aware of environmental issues and take steps to reduce their carbon footprint. They can do this by recycling, conserving water, and using renewable energy. They should also advocate for environmental policies and participate in environmental campaigns.

In conclusion, the responsibilities of youth are vast and varied. From contributing to society and pursuing education, to maintaining health, showing respect, and protecting the environment, young people carry a heavy load. Yet, it is through these responsibilities that they can truly make a difference. As they step into adulthood, they carry with them the power to shape the future. It is up to them to use this power wisely, fulfilling their responsibilities and creating a better world for all.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Responsibility For Students

- Essay on Responsibility For Health

- Essay on Philosophy On Education

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Young people hold the key to creating a better future

Image: Fateme Alaie/Unsplash

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Klaus Schwab

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Youth Perspectives is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, youth perspectives.

Listen to the article

- Young people are the most affected by the crises facing our world.

- They are also the ones with the most innovative ideas and energy to build a better society for tomorrow.

- Read the report "Davos Labs: Youth Recovery Plan" here .

Have you read?

Youth recovery plan.

Young people today are coming to age in a world beset by crises. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic devastated lives and livelihoods around the world, the socio-economic systems of the past had put the liveability of the planet at risk and eroded the pathway to healthy, happy, fulfilled lives for too many.

The same prosperity that enabled global progress and democracy after the Second World War is now creating the inequality, social discord and climate change we see today — along with a widening generational wealth gap and youth debt burden, too. For Millennials, the 2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession resulted in significant unemployment, huge student debt and a lack of meaningful jobs. Now, for Generation Z, COVID-19 has caused school shutdowns, worsening unemployment, and mass protests.

Young people are right to be deeply concerned and angry, seeing these challenges as a betrayal of their future.

But we can’t let these converging crises stifle us. We must remain optimistic – and we must act.

The next generation are the most important and most affected stakeholders when talking about our global future – and we owe them more than this. The year 2021 is the time to start thinking and acting long-term to make intergenerational parity the norm and to design a society, economy and international community that cares for all people.

Young people are also the best placed to lead this transformation. In the past 10 years of working with the World Economic Forum’s Global Shapers Community, a network of people between the ages of 20 and 30 working to address problems in more than 450 cities around the world, I’ve seen first-hand that they are the ones with the most innovative ideas and energy to build a better society for tomorrow.

Over the past year, Global Shapers organized dialogues on the most pressing issues facing society, government and business in 146 cities, reaching an audience of more than 2 million. The result of this global, multistakeholder effort, “ Davos Labs: Youth Recovery Plan ,” presents both a stark reminder of our urgent need to act and compelling insights for creating a more resilient, sustainable, inclusive world.

One of the unifying themes of the discussions was the lack of trust young people have for existing political, economic and social systems. They are fed up with ongoing concerns of corruption and stale political leadership, as well as the constant threat to physical safety caused by surveillance and militarized policing against activists and people of colour. In fact, more young people hold faith in governance by system of artificial intelligence than by a fellow human being.

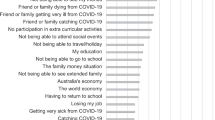

Facing a fragile labour market and almost bankrupt social security system, almost half of those surveyed said they felt they had inadequate skills for the current and future workforce, and almost a quarter said they would risk falling into debt if faced with an unexpected medical expense. The fact that half of the global population remains without internet access presents additional hurdles. Waves of lockdowns and the stresses of finding work or returning to workplaces have exacerbated the existential and often silent mental health crisis.

So, what would Millennials and Generation Z do differently?

Most immediately, they are calling for the international community to safeguard vaccine equity to respond to COVID-19 and prevent future health crises.

Young people are rallying behind a global wealth tax to help finance more resilient safety nets and to manage the alarming surge in wealth inequality. They are calling to direct greater investments to programmes that help young progressive voices join government and become policymakers.

I am inspired by the countless examples of young people pursuing collective action by bringing together diverse voices to care for their communities.

To limit global warming, young people are demanding a halt to coal, oil and gas exploration, development, and financing, as well as asking firms to replace any corporate board directors who are unwilling to transition to cleaner energy sources.

They are championing an open internet and a $2 trillion digital access plan to bring the world online and prevent internet shutdowns, and they are presenting new ways to minimize the spread of misinformation and combat dangerous extremist views. At the same time, they’re speaking up about mental health and calling for investment to prevent and tackle the stigma associated with it.

The Global Shapers Community is a network of young people under the age of 30 who are working together to drive dialogue, action and change to address local, regional and global challenges.

The community spans more than 8,000 young people in 165 countries and territories.

Teams of Shapers form hubs in cities where they self-organize to create projects that address the needs of their community. The focus of the projects are wide-ranging, from responding to disasters and combating poverty, to fighting climate change and building inclusive communities.

Examples of projects include Water for Life, a effort by the Cartagena Hub that provides families with water filters that remove biological toxins from the water supply and combat preventable diseases in the region, and Creativity Lab from the Yerevan Hub, which features activities for children ages 7 to 9 to boost creative thinking.

Each Shaper also commits personally and professionally to take action to preserve our planet.

Join or support a hub near you .

Transparency, accountability, trust and a focus on stakeholder capitalism will be key to meeting this generation’s ambitions and expectations. We must also entrust in them the power to take the lead to create meaningful change.

I am inspired by the countless examples of young people pursuing collective action by bringing together diverse voices to care for their communities. From providing humanitarian assistance to refugees to helping those most affected by the pandemic to driving local climate action, their examples provide the blueprints we need to build the more resilient, inclusive, and sustainable society and economy we need in the post-COVID-19 world.

We are living together in a global village, and it’s only by interactive dialogue, understanding each another and having respect for one another that we can create the necessary climate for a peaceful and sustainable world.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Youth Perspectives .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How countries can save millions by prioritising young people's sexual and reproductive health

Tomoko Fukuda and Andreas Daugaard Jørgensen

March 4, 2024

This is how to help young people navigate the opportunities and risks of AI and digital technology

Simon Torkington

January 31, 2024

Why we need to rebuild our social contract with the world's children

Catherine Russell

January 17, 2024

How global leaders can restore trust with young people

Natalie Pierce

January 13, 2024

A Children's Peace Prize winner's lessons on building trust between generations

Rena Kawasaki

December 20, 2023

Speaking Gen Z: How banks can attract young customers

Bob Wigley and Rupal Kantaria

November 17, 2023

Essay on Social Responsibility

Social responsibility is a term that has been used in different contexts, including the economy, education, politics , and religion. Social responsibility is challenging because it encompasses so many aspects, and there is no single definition of social responsibility. In simple words, social responsibility is the responsibility of an individual to act in a way that promotes social well-being. This means that a person has a sense of obligation to society and sacrifices for the good of others. BYJU’S essay on social responsibility explains the importance of being a socially responsible citizen.

A society’s responsibility to the individuals in that society can be seen through the various social programmes and laws. Governments try to create a better world for their citizens, so they implement various social programmes like welfare, tax assistance, and unemployment benefits. Laws are also crucial to a society because they enforce practical actions by its citizens and punish harmful actions. Now, let us understand the significance of social responsibility by reading a short essay on social responsibility.

Importance of Social Responsibility

BYJU’S essay on social responsibility highlights the importance of doing good deeds for society. The short essay lists different ways people can contribute to social responsibility, such as donating time and money to charities and giving back by visiting places like hospitals or schools. This essay discusses how companies can support specific causes and how people can be actively involved in volunteering and organisations to help humanitarian efforts.

Social responsibility is essential in many aspects of life. It helps to bring people together and also promotes respect for others. Social responsibility can be seen in how you treat other people, behave outside of work, and contribute to the world around you. In addition, there are many ways to be responsible for the protection of the environment, and recycling is one way. It is crucial to recycle materials to conserve resources, create less pollution, and protect the natural environment.

Society is constantly changing, and the way people live their lives may also vary. It is crucial to keep up with new technology so that it doesn’t negatively impact everyone else. Social responsibility is key to making sure that society is prosperous. For example, social media has created a platform for people to share their experiences and insights with other people. If a company were going to develop a new product or service, it would be beneficial for them to survey people about what they think about the idea before implementing it because prior knowledge can positively impact future decisions.

Social responsibility is essential because it creates a sense of responsibility to the environment . It can lead to greater trust among members of society. Another reason is that companies could find themselves at a competitive disadvantage if they do not ensure their practices are socially responsible. Moreover, companies help people in need through money, time, and clothing, which is a great way to showcase social responsibility.

Being socially responsible is a great responsibility of every human being, and we have briefly explained this in the short essay on social responsibility. Moreover, being socially responsible helps people upgrade the environment and society. For more essays, click on BYJU’S kids learning activities.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does being socially responsible help in protecting the environment.

Yes. Being socially responsible helps in protecting the environment.

Why should we be socially responsible?

We should be socially responsible because it is the right thing to upgrade society and the environment. Another reason is to help those in need because when more people have jobs, the economy can thrive, and people will have more opportunities.

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Preparing to Participate: The Role of Youth Social Responsibility and Political Efficacy on Civic Engagement for Black Early Adolescents

- Published: 08 September 2015

- Volume 9 , pages 609–630, ( 2016 )

Cite this article

- Elan C. Hope ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2886-5076 1

1792 Accesses

19 Citations

Explore all metrics

Civic engagement is critical for the well-being of youth and society. Scholars posit that civic beliefs are highly indicative of sustained civic engagement, particularly for Black youth living in the United States. In this study, I examine whether youth social responsibility and political efficacy beliefs are directly related to civic engagement and whether the relationship between youth social responsibility and civic outcomes varies by level of political efficacy among Black early adolescents in the Midwest United States ( N = 118). I also investigate whether youth social responsibility relates to civic engagement through political efficacy beliefs among this population. Findings show that political efficacy is related to four domains of civic engagement: helping, community action, formal political action, and activism. Political efficacy moderates the relationship between youth social responsibility and activism, such that the relationship between youth social responsibility and activism is stronger for Black youth with higher political efficacy beliefs. There is also an indirect effect of youth social responsibility on the relationship between political efficacy and civic engagement.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Social support in schools and related outcomes for LGBTQ youth: a scoping review

Enoch Leung, Gabriela Kassel-Gomez, … Tara Flanagan

“I Think Most of Society Hates Us”: A Qualitative Thematic Analysis of Interviews with Incels

Sarah E. Daly & Shon M. Reed

Risk and Protective Factors for Prospective Changes in Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Natasha R. Magson, Justin Y. A. Freeman, … Jasmine Fardouly

A Charter School is a publicly funded school that makes autonomous decisions with regard to curriculum and governance.

Adler, R. (2005). What do we mean by “civic engagement”? Journal of Transformative Education, 3 (3), 236–253.

Article Google Scholar

Aiken, L., & West, S. (1991). Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions . Newbury Park: Sage.

Google Scholar

Astuto, J., & Ruck, M. (2010). Early childhood as a foundation for civic engagement. In L. Sherrod, J. Torney-Purta, & C. Flanagan (Eds.), Handbook of research on civic engagement in youth (pp. 249–276). Hoboken: Wiley.

Chapter Google Scholar

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52 (1), 1–26.

Baron, R., & Kenny, D. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51 (6), 1173–1182.

Beaumont, E. (2010). Political agency and empowerment: pathways for developing a sense of political efficacy in young adults. In L. Sherrod, J. Torney-Purta, & C. Flanagan (Eds.), Handbook of research on civic engagement in youth (pp. 525–558). Hoboken: Wiley.

Checkoway, B., Allison, T., & Montoya, C. (2005). Youth participation in public policy at the municipal level. Children and Youth Services Review, 27 (10), 1149–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2005.01.001 .

Christens, B. (2012). Targeting empowerment in community development: a community psychology approach to enhancing local power and well-being. Community Development Journal, 47 (4), 538–554. doi: 10.1093/cdj/bss031 .

Christens, B., & Peterson, N. (2012). The role of empowerment in youth development: a study of sociopolitical control as mediator of ecological systems’ influence on developmental outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41 (5), 623–635. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9724-9 .

Christens, B., Peterson, N., & Speer, P. (2011). Community participation and psychological empowerment: testing reciprocal causality using a cross-lagged panel design and latent constructs. Health Education & Behavior, 38 (4), 339–347. doi: 10.1177/1090198110372880 .

Cohen, C. (2005). Democracy remixed: black youth and the future of american politics . New York: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, C. (2006). Black youth culture survey . Chicago: Black Youth Project. Data set accessed [2009] at http://www.blackyouthproject.com .

Crocetti, E., Jahromi, P., & Meeus, W. (2012). Identity and civic engagement in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 35 , 521–532. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescece.2011.08.003 .

Diemer, M. A., & Li, C.-H. (2011). Critical consciousness development and political participation among marginalized youth. Child Development, 82 (6), 1815–1833. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01650.x .

Eckstein, K., Noack, P., & Gniewosz, B. (2012). Attitudes toward political engagement and willingness to participate in politics: trajectories throughout adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 35 (3), 485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.07.002 .

Ekman, J., & Amnå, E. (2012). Political participation and civic engagement: towards a new typology. Human Affairs, 22 (3), 283–300.

Fine, M., Burns, A., Payne, Y., & Torre, M. (2004). Civic lessons: the color and class of betrayal. Teachers College Record, 106 (11), 2193–2223.

Finlay, A. K., Wray-Lake, L., & Flanagan, C. A. (2010). Civic engagement during the transition to adulthood: developmental opportunities and social policies at a critical juncture. In L. R. Sherrod & J. Torney-Purta (Eds.), Handbook of research on civic engagement in youth (pp. 277–305). Hoboken: Wiley.

Flanagan, C. (2013). Teenage citizens: the political theories of the young . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Flanagan, C., Beyers, W., & Žukauskienė, R. (2012). Political and civic engagement development in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 35 (3), 471–473. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.04.010 .

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed . New York: Continuum Publishing Co.

Gallay, L. (2006). Social responsibility. In L. Sherrod, C. Flanagan, R. Kassimir, & A. Syvertsen (Eds.), Youth activism: an international encyclopedia (pp. 599–602). Westport: Greenwood Publishing.

Ginwright, S. (2010). Black youth rising: activism and radical healing in urban America . New York: Teacher’s College Press.

Ginwright, S., & James, T. (2002). From assets to agents of change: social justice, organizing, and youth development. In B. Kirshner, J. O’Donoghue, & M. McLaughlin (Eds.), Youth participation: improving institutions and communities (pp. 27–46). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Graham, J. (2012). Missing data: analysis and design . New York: Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Gurin, P., Nagda, B., & Zuniga, X. (2013). Dialogue across difference: practice, theory, and research on intergroup dialogue . New York: Sage Foundation.

Hahn. (1998). Becoming political: comparative perspectives on citizenship education . New York: University of New York Press.

Hart, D., Donnelly, T. M., Youniss, J., & Atkins, R. (2007). High school community service as a predictor of adult voting and volunteering. American Educational Research Journal, 44 (1), 197–219.

Hoffman, L., & Thompson, T. (2009). The effect of television viewing on adolescents’ civic participation: political efficacy as a mediating mechanism. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 53 (1), 3–21. doi: 10.1080/08828150802643415 .

Hope, E., & Jagers, R. (2014). The role of sociopolitical attitudes and civic education in the civic engagement of black youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24 (3), 460–470. doi: 10.1111/jora.12117 .

Hope, E., Skoog, A., & Jagers, R. (2014). “It’ll never be the white kids, it’ll always be us”: black high school students’ evolving critical analysis of racial discrimination and inequity in schools. Journal of Adolescent Research, 30 (1), 83–112. doi: 10.1177/0743558414550688 .

Lerner, R. (2004). Liberty: thriving and civic engagement among America’s youth . Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Levinson, M. (2007). The civic achievement gap (CIRCLE working paper 51) . College Park: Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement.

Martínez, M. L., Peñaloza, P., & Valenzuela, C. (2012). Civic commitment in young activists: emergent processes in the development of personal and collective identity. Journal of Adolescence, 35 (3), 474–484. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.11.006 .

McGuire, J., & Gamble, W. (2006). Community service for youth: the value of psychological engagement over number of hours spent. Journal of Adolescence, 29 , 289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.07.006 .

Metzger, A., & Smetana, J. (2010). Social cognitive development and adolescent civic engagement. In L. Sherrod, J. Torney-Purta, & C. Flanagan (Eds.), Handbook of research on civic engagement in youth (pp. 221–248). Hoboken: Wiley.

Mitra, D. L., & Serriere, S. C. (2012). Student voice in elementary school reform: examining youth development in fifth graders. American Educational Research Journal, 49 (4), 743–774. doi: 10.3102/0002831212443079 .

Mohiyeddini, C., & Montada, L. (1998). Beliefs in a just world and self-efficacy in coping with observed victimization: results from a study about unemployment. In L. Montada & M. Lerner (Eds.), Responses to victimizations and belief in a just world (pp. 41–54). New York: Plenum Press.

Morrell, M. (2003). Survey and experimental evidence for a reliable and valid measure of internal political efficacy. Public Opinion Quarterly, 67 (4), 589–602.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2011). The nation’s report card: civics 2010 (NCES 2011–466) . Washington: Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Pancer, S., Pratt, M., Hunsberger, B., & Alisat, S. (2007). Community and political involvement in adolescence: what distinguishes the activists from the uninvolved? Journal of Community Psychology, 35 , 741–759.

Rappaport, J. (1987). Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: toward a theory for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 15 (2), 121–148.

Reinders, H., & Youniss, J. (2006). School-based required community service and civic development in adolescents. Applied Developmental Science, 10 (1), 2–12. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads1001_1 .

Schmid, C. (2012). The value “social responsibility’as a motivating factor for adolescents” readiness to participate in different types of political actions, and its socialization in parent and peer contexts. Journal of Adolescence, 35 (3), 533–547. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.03.009 .

Sherrod, L. R. (2003). Promoting the development of citizenship in diverse youth. Political Science and Politics, 36 (02), 287–292.

Sherrod, L., & Lauckhardt, J. (2008). The development of citizenship. In R. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (3rd ed., Vol. 2, pp. 372–408). Hoboken: Wiley.

Sherrod, L., Torney-Purta, J., & Flanagan, C. (2010). Research on the development of citizenship: a field comes of age. In L. Sherrod, J. Torney-Purta, & C. Flanagan (Eds.), Handbook of research on civic engagement in youth (pp. 1–22). Hoboken: Wiley.

Vela, H. (2013). Takoma Park lowers voting age to 16. ABC7 WJLA. Retrieved from http://www.wjla.com .

Watts, R. J., & Flanagan, C. A. (2007). Pushing the envelope on youth civic engagement: a developmental and liberation psychology perspective. Journal of Community Psychology, 35 (6), 779–792. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20178 .

Watts, R., & Guessous, O. (2006). Sociopolitical development: the missing link in research and policy on adolescents. In S. Ginwright, P. Noguera, & J. Cammarota (Eds.), Beyond resistance! youth activism and community change: new democratic possibilities for practice and policy for America’s youth . New York: Routledge.

Watts, R. J., Williams, N. C., & Jagers, R. J. (2003). Sociopolitical development. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31 (1), 185–194.

Watts, R. J., Diemer, M. A., & Voight, A. M. (2011). Critical consciousness: current status and future directions. In C. A. Flanagan & B. D. Christens (Eds.), Youth civic development: work at the cutting edge (Vol. 134). San Francisco: Josey-Bass.

Wentzel, K., Filisetti, L., & Looney, L. (2007). Adolescent prosocial behavior: the role of self-processes and contextual cues. Child Development, 78 (3), 895–910.

Wray-Lake, L., & Syvertsen, A. (2011). The developmental roots of social responsibility in childhood and adolescence. In C. A. Flanagan & B. D. Christens (Eds.), Youth civic development: work at the cutting edge (Vol. 134). San Francisco: Josey-Bass.

Yates, M., & Youniss, J. (1996). A developmental perspective on community service in adolescence. Social Development, 5 (1), 85–111.

Youniss, J., Bales, S., Christmas-Best, V., Diversi, M., McLaughlin, W., & Silbereisen, R. (2002). Youth civic engagement in the twenty-first century. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 12 (1), 121–148.

Zaff, J., Kawashima-Ginsberg, K., Lin, E., Lamb, M., Balsano, A., & Lerner, R. (2011). Journal of Adolescence, 34 (6), 1207–1220. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.07.005 .

Zimmerman, M. A. (1995). Psychological empowerment: issues and illustrations. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23 (5), 581–599.

Zimmerman, M. A., Ramirez-Valles, J., & Maton, K. I. (1999). Resilience among urban African american male adolescents: a study of the protective effects of sociopolitical control on their mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology, 27 (6), 733–751.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, North Carolina State University, 2310 Stinson Drive, Raleigh, NC, 27695-7650, USA

Elan C. Hope

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Elan C. Hope .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Hope, E.C. Preparing to Participate: The Role of Youth Social Responsibility and Political Efficacy on Civic Engagement for Black Early Adolescents. Child Ind Res 9 , 609–630 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-015-9331-5

Download citation

Accepted : 01 September 2015

Published : 08 September 2015

Issue Date : September 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-015-9331-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Civic engagement

- Political efficacy

- Social responsibility

- Early adolescence

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

SDGs Youth Leadership and Social Responsibility Education

Global duck (qingdao) education technology co., ltd ( private sector ), #sdgaction44147.

- Description

- SDGs & Targets

- SDG 14 targets covered

- Deliverables & timeline

- Resources mobilized

- Progress reports

The initiative aims to enhance the social responsibility and leadership of youth to achieve sustainable development goals (SDGs). The social responsibility and leadership to achieve the SDGs mainly refer to the sustainable development awareness, innovation and entrepreneurship ability and social influence. This initiative focuses on guiding youth to contribute to the zero Carbon, ecological civilization, rural revitalization, social equity and common prosperity. Hence, this initiative construct an international alliance to provide youth with more opportunities to take SDGs social innovation action by cooperating, encouraging and empowering different public stakeholders (government, enterprise, school and campus, non-governmental organization, community and family, individual, etc). Specifically, it will provide systematic SDGs training for the members in the alliance to jointly improve youth SDGs social responsibility and leadership. Meanwhile, it will constructs professional standards to support different stakeholders to design, monitor and evaluate the SDGs education in the various fields. Additionally, it will establish comprehensive certification and incentive systems of SDGs social responsibility and leadership for trainers and youths to create a positive SDGs acting culture. Specifically, in order to effectively achieve this initiative, it sets up an International education alliance which is governed by SDGs Youth Education Management Committee (SYEMC). The details are as follows.

1.Sustainable development promoting institutions (including non-governmental organizations), such as Youth Sharing Ecology Education Alliance which aims at leading college students to carry out urban and rural public welfare SDGs education projects. The SYEMC will invite China Green University Network, Ecological civilization education research branch of Chinese society of Higher Education and other authorities to promote and supervise this initiative.

2.Enterprise that promotes SDGs, ESG and CSR. For example, Global Duck (Qingdao) Education Technology Co., Ltd and Beijing Yanda Jinghua Education Technology Co., Ltd are two enterprises aiming at promoting SDGs education and ecological civilization education by STEAM courses. Qingdao GLOREES Investment & Consulting Co., Ltd is an international ESG investment enterprise, and it also provides one-stop emission reduction schemes for education, agriculture, tourism and other industries.

3.Campus and School (including teachers and students). The SYEMC invites Asian classic sustainable development schools and campus to join, which can provide front-line teaching and scientific research achievements. Most of them are come from the functional departments, laboratories and student associations, such as Green Oil Environmental Protection Association of China University of Petroleum (East China) which has been engaged in the field of youth environmental protection education for about ten years and gains the the authoritative award in the field of environmental protection for Chinese youth.

4.Community and family. As the important groups to educate youth, community and family are invited to share educational cases and life feeling about youth which will directly reflects the improve effect of SDGs leadership and social responsibility.

5.Experts from government, UN System, universities and non-governmental organizations. Experts will put forward suggestions for the implementation and effect evaluation of this initiative, and review the monthly report. The progress report of this initiative will not only submit to the UNDESA regularly but also share on the public media.

In order to give full play to the important role of youth in achieving SDGs, this initiative will take four methodologies: establish the SDGs International Competition and Communication Platform (SICCP) aiming at educating youth leadership and social responsibility in global governance practice; establish SDGs Standard Instructor Training Mechanism (SSITM) for enterprises, schools and campus, NGOs, communities, families and other stakeholders aiming at training more persons to jointly carry out SDGs youth education in various scenarios; establish SDGs Standard Youth Action Authentication System (SSYAAS) aiming at quantifying the effectiveness of actions and encourage youth to assume social responsibility; develop the SDGs Immersive Social Responsibility and Leadership Education System (SISRLES) based on the STEM and PBL for urban and rural youth aiming at promoting basic understanding of SDGs;

1.SDGs International Competition and Communication Platform. The theme of this competition is the game-changing solution innovation of SDGs which is divided into four levels, covering a period of 8 months every year. Many social enterprises and NGOs are invited as providers of practical competition cases. The SICCP will provide SDGs information package, SDGs evaluation tools, SDGs training camp, SDGs competition manual, long-term cooperation of award-winning projects and some other supports. The SICCP is open to youth around the world that put more emphasis on leading youth to influence more groups to achieve SDGs in daily life by improving their own SDG leadership and social responsibility. Meanwhile, it will establish the global and regional annual rankings to select the top 100 youth with the greatest SDGs leadership. Besides, the SICCP provides the platform for global youth to exchange and cooperate SDGs practice in various regions, and promotes the construction of a community with a shared future for mankind.

2.SDGs Standard Instructor Training Mechanism for enterprises, schools and campus, NGOs, communities, families and other stakeholders. The SSITM will set up three-level certification for education instructors in different industries according to the learning duration and mode to evaluates and authorizes qualified institutions as training partners to jointly conduct training for SDGs youth leadership and social responsibility. And it will grant project certification to compliant instructors. For example, SDGs Social Responsible Enterprise, SDGs Educational Influence School and Campus, SDGs Leadership Potential Community or Family, SDGs research center, SDGs immersive trainer, etc.

3.SDGs Standard Youth Action Authentication System. This system will provide youth with the tools for recording SDGs action plan, duration and effect. Through systematic certification, youth will be given the ranking of SDGs leadership and social responsibility. And youth will have the special certificate of SDGs action. Meanwhile, youth can obtain “green energy points” through the authentication, which can exchange series of ecological products and SDGs creative products.

4.SDGs Immersive Social Responsibility and Leadership Education System. This system will consist of comics and animation education software and hardware, which caters to the interest of youth. This initiative plans to develop hundreds of SDGs leadership and social responsibility courses which all have special certification label and study certificates.

1.Global Duck (Qingdao) Education Technology Co., Ltd, a social enterprise focusing on Ecological Civilization Education.

2.Qingdao GLOREES Investment & Consulting Co., Ltd, an enterprise focusing on ESG investment. 3.Green Oil Environmental Protection Association of China University of Petroleum (East China), a well-known college environmental protection association.

4.Youth Sharing Ecology Education Alliance, an active educational communication network.

5.Beijing Yanda Jinghua Education Technology Co., Ltd, an international K-12 education consulting company.

6.Qingdao West Coast New Area Wisdom Future Public Welfare Student Service Center, a non-governmental organization that has been committed to achieving high-quality education for many years.

Arrangements for Capacity-Building and Technology Transfer

1.SDGs International Competition and Communication Platform (SICCP) includes four levels of competitions: primary school level, junior middle school level, senior high school level and campus level. Each level will four-round competitions. The competition will be jointly organized by the government, enterprises, schools and non-governmental organization. The contestants will receive a series of SDGs online and offline professional training and be required to complete the learning content for a specified period of time. Participants who complete the competition according to the regulations will receive gold, silver and bronze awards which refer to different ranges of support.

2.SDGs Standard Instructor Training Mechanism (SSITM) offers courses on six topics: “Significance and Case Interpretation of SDGs”, “SDGs, Ecological Civilization, Rural Revitalization and Common Prosperity”, “Sustainable Development Planning of Corporate Social Responsibility”, “Incentive Strategies for Carbon Reduction Behavior in Citizen Production and Consumption”, “Teaching Practice of Youth Sustainable Development Career Planning” and “Circular Economy and Zero Carbon Goal”. These courses will be delivered by experts from SYEMC and international leading institutions in the sustainable development fields. These courses will formulate curriculum standards, instructor qualification certification and teaching mode for entities to participate in youth SDGs education, promote cooperation between entities and schools, communities and families, and enhance the global influence of SDGs education. The total course hours are 180 hours, which is divided into online, offline and practical parts. The SSITM will issue junior, intermediate and advanced instructor certificates according to the scope of study (compulsory and elective courses), learning hours (60 hours, 120 hours and 180 hours) and examination results (70% of the exam scores are qualified). Each certificate will have a unique number and one-year validity. Meanwhile, this initiative will authorize SDGs leadership and social responsibility education centers for entities which have have a certain number of certified instructors that they can independently carry out SDGs education activities.

3.SDGs Standard Youth Action Authentication System (SSYAAP) mainly provides four functions: release SDGs project, identify action duration, quantify carbon reduction effect and exchange ecological products. It provides youth with more practice opportunities to participate in SDGs projects in life and sets up a series of incentive behaviors to enable youth to lead more people to achieve SDGs. Meanwhile, the SSYAAP will set up local SDGs experience areas to provide support for offline communication activities of youth. SDGs Immersive Social Responsibility and Leadership Education System (SISRLES) offers PBL courses on six subject for youth. Every subject provides three levels of courses and eight immersive teaching methods of methods according to the age group of youth (6-12,12-18,18-22). The course has six characteristics: systematization, localization, immersive, practical, flipped and animation. The courses incorporate the concept of social innovation and selects the actual social development cases as the content, which not only efficiently improve the leadership and social responsibility but also achieve the 21st Century 5C Model of Core Literacy. The course adopts online and offline teaching strategies which are applicable to school-based education, community education, family education and camp education.

End poverty in all its forms everywhere

By 2030, eradicate extreme poverty for all people everywhere, currently measured as people living on less than $1.25 a day

Proportion of the population living below the international poverty line by sex, age, employment status and geographical location (urban/rural)

By 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions

Proportion of population living below the national poverty line, by sex and age

Proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions

Implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors, and by 2030 achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable

Proportion of population covered by social protection floors/systems, by sex, distinguishing children, unemployed persons, older persons, persons with disabilities, pregnant women, newborns, work-injury victims and the poor and the vulnerable

By 2030, ensure that all men and women, in particular the poor and the vulnerable, have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership and control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, natural resources, appropriate new technology and financial services, including microfinance

Proportion of population living in households with access to basic services

Proportion of total adult population with secure tenure rights to land, ( a ) with legally recognized documentation, and ( b ) who perceive their rights to land as secure, by sex and by type of tenure

By 2030, build the resilience of the poor and those in vulnerable situations and reduce their exposure and vulnerability to climate-related extreme events and other economic, social and environmental shocks and disasters

Number of deaths, missing persons and directly affected persons attributed to disasters per 100,000 population

Direct economic loss attributed to disasters in relation to global gross domestic product (GDP)

Number of countries that adopt and implement national disaster risk reduction strategies in line with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030

Proportion of local governments that adopt and implement local disaster risk reduction strategies in line with national disaster risk reduction strategies

Ensure significant mobilization of resources from a variety of sources, including through enhanced development cooperation, in order to provide adequate and predictable means for developing countries, in particular least developed countries, to implement programmes and policies to end poverty in all its dimensions

Total official development assistance grants from all donors that focus on poverty reduction as a share of the recipient country's gross national income

Proportion of total government spending on essential services (education, health and social protection)

Create sound policy frameworks at the national, regional and international levels, based on pro-poor and gender-sensitive development strategies, to support accelerated investment in poverty eradication actions

Pro-poor public social spending

End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture

By 2030, end hunger and ensure access by all people, in particular the poor and people in vulnerable situations, including infants, to safe, nutritious and sufficient food all year round

Prevalence of undernourishment

Prevalence of moderate or severe food insecurity in the population, based on the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES)

By 2030, end all forms of malnutrition, including achieving, by 2025, the internationally agreed targets on stunting and wasting in children under 5 years of age, and address the nutritional needs of adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women and older persons

Prevalence of stunting (height for age <-2 standard deviation from the median of the World Health Organization (WHO) Child Growth Standards) among children under 5 years of age

Prevalence of malnutrition (weight for height >+2 or <-2 standard deviation from the median of the WHO Child Growth Standards) among children under 5 years of age, by type (wasting and overweight)

Prevalence of anaemia in women aged 15 to 49 years, by pregnancy status (percentage)

Volume of production per labour unit by classes of farming/pastoral/forestry enterprise size

Average income of small-scale food producers, by sex and indigenous status

By 2030, ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices that increase productivity and production, that help maintain ecosystems, that strengthen capacity for adaptation to climate change, extreme weather, drought, flooding and other disasters and that progressively improve land and soil quality

Proportion of agricultural area under productive and sustainable agriculture

By 2020, maintain the genetic diversity of seeds, cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals and their related wild species, including through soundly managed and diversified seed and plant banks at the national, regional and international levels, and promote access to and fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge, as internationally agreed

Number of ( a ) plant and ( b ) animal genetic resources for food and agriculture secured in either medium- or long-term conservation facilities

Proportion of local breeds classified as being at risk of extinction

The agriculture orientation index for government expenditures

Total official flows (official development assistance plus other official flows) to the agriculture sector

Correct and prevent trade restrictions and distortions in world agricultural markets, including through the parallel elimination of all forms of agricultural export subsidies and all export measures with equivalent effect, in accordance with the mandate of the Doha Development Round

Agricultural export subsidies

Adopt measures to ensure the proper functioning of food commodity markets and their derivatives and facilitate timely access to market information, including on food reserves, in order to help limit extreme food price volatility

Indicator of food price anomalies

Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all

By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes

Proportion of children and young people ( a ) in grades 2/3; ( b ) at the end of primary; and ( c ) at the end of lower secondary achieving at least a minimum proficiency level in (i) reading and (ii) mathematics, by sex

Completion rate (primary education, lower secondary education, upper secondary education)

By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education

Proportion of children aged 24–59 months who are developmentally on track in health, learning and psychosocial well-being, by sex

Participation rate in organized learning (one year before the official primary entry age), by sex

By 2030, ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university

Participation rate of youth and adults in formal and non-formal education and training in the previous 12 months, by sex

By 2030, substantially increase the number of youth and adults who have relevant skills, including technical and vocational skills, for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship

Proportion of youth and adults with information and communications technology (ICT) skills, by type of skill

Parity indices (female/male, rural/urban, bottom/top wealth quintile and others such as disability status, indigenous peoples and conflict-affected, as data become available) for all education indicators on this list that can be disaggregated

By 2030, ensure that all youth and a substantial proportion of adults, both men and women, achieve literacy and numeracy

Proportion of population in a given age group achieving at least a fixed level of proficiency in functional ( a ) literacy and ( b ) numeracy skills, by sex

By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development

Extent to which (i) global citizenship education and (ii) education for sustainable development are mainstreamed in ( a ) national education policies; ( b ) curricula; ( c ) teacher education and ( d ) student assessment

Build and upgrade education facilities that are child, disability and gender sensitive and provide safe, non-violent, inclusive and effective learning environments for all

Proportion of schools offering basic services, by type of service

Volume of official development assistance flows for scholarships by sector and type of study

By 2030, substantially increase the supply of qualified teachers, including through international cooperation for teacher training in developing countries, especially least developed countries and small island developing States

Proportion of teachers with the minimum required qualifications, by education level

Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable

By 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums

Proportion of urban population living in slums, informal settlements or inadequate housing

Proportion of population that has convenient access to public transport, by sex, age and persons with disabilities

Ratio of land consumption rate to population growth rate

Proportion of cities with a direct participation structure of civil society in urban planning and management that operate regularly and democratically

Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage

Total per capita expenditure on the preservation, protection and conservation of all cultural and natural heritage, by source of funding (public, private), type of heritage (cultural, natural) and level of government (national, regional, and local/municipal)

By 2030, significantly reduce the number of deaths and the number of people affected and substantially decrease the direct economic losses relative to global gross domestic product caused by disasters, including water-related disasters, with a focus on protecting the poor and people in vulnerable situations

Direct economic loss attributed to disasters in relation to global domestic product (GDP)

( a ) Damage to critical infrastructure and ( b ) number of disruptions to basic services, attributed to disasters

By 2030, reduce the adverse per capita environmental impact of cities, including by paying special attention to air quality and municipal and other waste management

Proportion of municipal solid waste collected and managed in controlled facilities out of total municipal waste generated, by cities

Annual mean levels of fine particulate matter (e.g. PM2.5 and PM10) in cities (population weighted)

Average share of the built-up area of cities that is open space for public use for all, by sex, age and persons with disabilities

Proportion of persons victim of physical or sexual harassment, by sex, age, disability status and place of occurrence, in the previous 12 months

Support positive economic, social and environmental links between urban, peri-urban and rural areas by strengthening national and regional development planning

Number of countries that have national urban policies or regional development plans that ( a ) respond to population dynamics; ( b ) ensure balanced territorial development; and ( c ) increase local fiscal space

By 2020, substantially increase the number of cities and human settlements adopting and implementing integrated policies and plans towards inclusion, resource efficiency, mitigation and adaptation to climate change, resilience to disasters, and develop and implement, in line with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030, holistic disaster risk management at all levels

Number of countries that adopt and implement national disaster risk reduction strategies in line with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030

Support least developed countries, including through financial and technical assistance, in building sustainable and resilient buildings utilizing local materials

Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns

Implement the 10-Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns, all countries taking action, with developed countries taking the lead, taking into account the development and capabilities of developing countries

Number of countries developing, adopting or implementing policy instruments aimed at supporting the shift to sustainable consumption and production

By 2030, achieve the sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources

Material footprint, material footprint per capita, and material footprint per GDP

Domestic material consumption, domestic material consumption per capita, and domestic material consumption per GDP

By 2030, halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses

( a ) Food loss index and ( b ) food waste index

By 2020, achieve the environmentally sound management of chemicals and all wastes throughout their life cycle, in accordance with agreed international frameworks, and significantly reduce their release to air, water and soil in order to minimize their adverse impacts on human health and the environment

( a ) Hazardous waste generated per capita; and ( b ) proportion of hazardous waste treated, by type of treatment

By 2030, substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse

National recycling rate, tons of material recycled

Encourage companies, especially large and transnational companies, to adopt sustainable practices and to integrate sustainability information into their reporting cycle

Promote public procurement practices that are sustainable, in accordance with national policies and priorities

Number of countries implementing sustainable public procurement policies and action plans

By 2030, ensure that people everywhere have the relevant information and awareness for sustainable development and lifestyles in harmony with nature

Extent to which (i) global citizenship education and (ii) education for sustainable development are mainstreamed in ( a ) national education policies; ( b ) curricula; ( c ) teacher education; and ( d ) student assessment

Support developing countries to strengthen their scientific and technological capacity to move towards more sustainable patterns of consumption and production

Installed renewable energy-generating capacity in developing countries (in watts per capita)

Develop and implement tools to monitor sustainable development impacts for sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products

Implementation of standard accounting tools to monitor the economic and environmental aspects of tourism sustainability

Rationalize inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies that encourage wasteful consumption by removing market distortions, in accordance with national circumstances, including by restructuring taxation and phasing out those harmful subsidies, where they exist, to reflect their environmental impacts, taking fully into account the specific needs and conditions of developing countries and minimizing the possible adverse impacts on their development in a manner that protects the poor and the affected communities

Amount of fossil-fuel subsidies (production and consumption) per unit of GDP

Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts

Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries

Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning

Number of countries with nationally determined contributions, long-term strategies, national adaptation plans and adaptation communications, as reported to the secretariat of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

Total greenhouse gas emissions per year

Improve education, awareness-raising and human and institutional capacity on climate change mitigation, adaptation, impact reduction and early warning

Implement the commitment undertaken by developed-country parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change to a goal of mobilizing jointly $100 billion annually by 2020 from all sources to address the needs of developing countries in the context of meaningful mitigation actions and transparency on implementation and fully operationalize the Green Climate Fund through its capitalization as soon as possible

Amounts provided and mobilized in United States dollars per year in relation to the continued existing collective mobilization goal of the $100 billion commitment through to 2025

Promote mechanisms for raising capacity for effective climate change-related planning and management in least developed countries and small island developing States, including focusing on women, youth and local and marginalized communities

Number of least developed countries and small island developing States with nationally determined contributions, long-term strategies, national adaptation plans and adaptation communications, as reported to the secretariat of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development

By 2025, prevent and significantly reduce marine pollution of all kinds, in particular from land-based activities, including marine debris and nutrient pollution

( a ) Index of coastal eutrophication; and ( b ) plastic debris density

By 2020, sustainably manage and protect marine and coastal ecosystems to avoid significant adverse impacts, including by strengthening their resilience, and take action for their restoration in order to achieve healthy and productive oceans

Number of countries using ecosystem-based approaches to managing marine areas

Minimize and address the impacts of ocean acidification, including through enhanced scientific cooperation at all levels

By 2020, effectively regulate harvesting and end overfishing, illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and destructive fishing practices and implement science-based management plans, in order to restore fish stocks in the shortest time feasible, at least to levels that can produce maximum sustainable yield as determined by their biological characteristics

By 2020, conserve at least 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, consistent with national and international law and based on the best available scientific information

By 2020, prohibit certain forms of fisheries subsidies which contribute to overcapacity and overfishing, eliminate subsidies that contribute to illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and refrain from introducing new such subsidies, recognizing that appropriate and effective special and differential treatment for developing and least developed countries should be an integral part of the World Trade Organization fisheries subsidies negotiation

Degree of implementation of international instruments aiming to combat illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing

By 2030, increase the economic benefits to Small Island developing States and least developed countries from the sustainable use of marine resources, including through sustainable management of fisheries, aquaculture and tourism

Sustainable fisheries as a proportion of GDP in small island developing States, least developed countries and all countries

Increase scientific knowledge, develop research capacity and transfer marine technology, taking into account the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Criteria and Guidelines on the Transfer of Marine Technology, in order to improve ocean health and to enhance the contribution of marine biodiversity to the development of developing countries, in particular small island developing States and least developed countries

Provide access for small-scale artisanal fishers to marine resources and markets

Degree of application of a legal/regulatory/policy/institutional framework which recognizes and protects access rights for small‐scale fisheries

Enhance the conservation and sustainable use of oceans and their resources by implementing international law as reflected in United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which provides the legal framework for the conservation and sustainable use of oceans and their resources, as recalled in paragraph 158 of "The future we want"

Number of countries making progress in ratifying, accepting and implementing through legal, policy and institutional frameworks, ocean-related instruments that implement international law, as reflected in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, for the conservation and sustainable use of the oceans and their resources

Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss

By 2020, ensure the conservation, restoration and sustainable use of terrestrial and inland freshwater ecosystems and their services, in particular forests, wetlands, mountains and drylands, in line with obligations under international agreements

By 2020, promote the implementation of sustainable management of all types of forests, halt deforestation, restore degraded forests and substantially increase afforestation and reforestation globally

By 2030, combat desertification, restore degraded land and soil, including land affected by desertification, drought and floods, and strive to achieve a land degradation-neutral world

By 2030, ensure the conservation of mountain ecosystems, including their biodiversity, in order to enhance their capacity to provide benefits that are essential for sustainable development

Take urgent and significant action to reduce the degradation of natural habitats, halt the loss of biodiversity and, by 2020, protect and prevent the extinction of threatened species

Promote fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources and promote appropriate access to such resources, as internationally agreed

Take urgent action to end poaching and trafficking of protected species of flora and fauna and address both demand and supply of illegal wildlife products

By 2020, introduce measures to prevent the introduction and significantly reduce the impact of invasive alien species on land and water ecosystems and control or eradicate the priority species

By 2020, integrate ecosystem and biodiversity values into national and local planning, development processes, poverty reduction strategies and accounts

( a ) Number of countries that have established national targets in accordance with or similar to Aichi Biodiversity Target 2 of the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 in their national biodiversity strategy and action plans and the progress reported towards these targets; and ( b ) integration of biodiversity into national accounting and reporting systems, defined as implementation of the System of Environmental-Economic Accounting

Mobilize and significantly increase financial resources from all sources to conserve and sustainably use biodiversity and ecosystems

( a ) Official development assistance on conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity; and ( b ) revenue generated and finance mobilized from biodiversity-relevant economic instruments

Mobilize significant resources from all sources and at all levels to finance sustainable forest management and provide adequate incentives to developing countries to advance such management, including for conservation and reforestation

Enhance global support for efforts to combat poaching and trafficking of protected species, including by increasing the capacity of local communities to pursue sustainable livelihood opportunities

Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development

Strengthen domestic resource mobilization, including through international support to developing countries, to improve domestic capacity for tax and other revenue collection

Developed countries to implement fully their official development assistance commitments, including the commitment by many developed countries to achieve the target of 0.7 per cent of ODA/GNI to developing countries and 0.15 to 0.20 per cent of ODA/GNI to least developed countries; ODA providers are encouraged to consider setting a target to provide at least 0.20 per cent of ODA/GNI to least developed countries

Mobilize additional financial resources for developing countries from multiple sources

Additional financial resources mobilized for developing countries from multiple sources

Assist developing countries in attaining long-term debt sustainability through coordinated policies aimed at fostering debt financing, debt relief and debt restructuring, as appropriate, and address the external debt of highly indebted poor countries to reduce debt distress

Adopt and implement investment promotion regimes for least developed countries

Number of countries that adopt and implement investment promotion regimes for developing countries, including the least developed countries

Enhance North-South, South-South and triangular regional and international cooperation on and access to science, technology and innovation and enhance knowledge sharing on mutually agreed terms, including through improved coordination among existing mechanisms, in particular at the United Nations level, and through a global technology facilitation mechanism

Fixed Internet broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants, by speed

Promote the development, transfer, dissemination and diffusion of environmentally sound technologies to developing countries on favourable terms, including on concessional and preferential terms, as mutually agreed

Total amount of funding for developing countries to promote the development, transfer, dissemination and diffusion of environmentally sound technologies

Fully operationalize the technology bank and science, technology and innovation capacity-building mechanism for least developed countries by 2017 and enhance the use of enabling technology, in particular information and communications technology

Enhance international support for implementing effective and targeted capacity-building in developing countries to support national plans to implement all the Sustainable Development Goals, including through North-South, South-South and triangular cooperation

Dollar value of financial and technical assistance (including through North-South, South‑South and triangular cooperation) committed to developing countries

Promote a universal, rules-based, open, non-discriminatory and equitable multilateral trading system under the World Trade Organization, including through the conclusion of negotiations under its Doha Development Agenda

Significantly increase the exports of developing countries, in particular with a view to doubling the least developed countries’ share of global exports by 2020

Developing countries’ and least developed countries’ share of global exports

Realize timely implementation of duty-free and quota-free market access on a lasting basis for all least developed countries, consistent with World Trade Organization decisions, including by ensuring that preferential rules of origin applicable to imports from least developed countries are transparent and simple, and contribute to facilitating market access

Weighted average tariffs faced by developing countries, least developed countries and small island developing States

Enhance global macroeconomic stability, including through policy coordination and policy coherence

Enhance policy coherence for sustainable development

Respect each country’s policy space and leadership to establish and implement policies for poverty eradication and sustainable development

Enhance the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development, complemented by multi-stakeholder partnerships that mobilize and share knowledge, expertise, technology and financial resources, to support the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals in all countries, in particular developing countries

Number of countries reporting progress in multi-stakeholder development effectiveness monitoring frameworks that support the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals

Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships, building on the experience and resourcing strategies of partnerships

Amount in United States dollars committed to public-private partnerships for infrastructure

By 2020, enhance capacity-building support to developing countries, including for least developed countries and small island developing States, to increase significantly the availability of high-quality, timely and reliable data disaggregated by income, gender, age, race, ethnicity, migratory status, disability, geographic location and other characteristics relevant in national contexts

Statistical capacity indicator for Sustainable Development Goal monitoring

Number of countries with a national statistical plan that is fully funded and under implementation, by source of funding

By 2030, build on existing initiatives to develop measurements of progress on sustainable development that complement gross domestic product, and support statistical capacity-building in developing countries