Is It Fair Use? 7 Questions to Ask Before Using Copyrighted Material

Note from Jane : This guest post is by attorney Bradlee Frazer has been updated to address reader questions and offer more information about fair use. Be sure to read his previous posts:

- Q&A on Copyright —plus his 101 post on copyright

- Guidelines on using trademarks in your work

You might also want to reference my post: When Do You Need to Secure Permissions?

Authors create copyrights when they express their ideas into or onto a tangible medium. This means the author has the right to make copies of the work; the right to create derivative works; the right to distribute copies of the work; the right to publicly perform the work; the right to display the work; and, in the case of sound recordings, the right to perform the work by means of a digital audio transmission.

If you are the sole owner of the copyright to a work, you are the only one who may lawfully do these things or sell/license the rights to someone else to do these things. Conversely, doing one or more of these things without the copyright owner’s permission is called copyright infringement.

One defense against copyright infringement is fair use. Fair use allows you to use someone’s copyrighted work without permission. However, invoking fair use is not a straightforward matter.

The fair use doctrine is defined here . To bring your otherwise unauthorized use within the protection of the doctrine, there are two separate and important considerations. First, your use must be for “purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research.”

This is the first prong. If your use falls into one of these categories, then you move to the second prong of the test. A court will consider the following four factors to determine if your use is a fair use:

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (emphasis added)

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

If your use falls into one of the enumerated categories AND you are able to prevail factually on at least two of the four second-prong factors, you might succeed in proving that your use is fair and thus not copyright infringement.

Here’s an example.

Let’s say you are writing a novel for commercial publication and you wish to reproduce the lyrics to the song “Little Red Corvette” by Prince in the book. You are not reproducing the sheet music, and you are not including a sound recording of the song with the book. You are merely causing the literal words of the lyric to appear as prose within your book. Here is the analysis:

- Do you own the copyright to the work? No. The author and copyright claimant of these song lyrics are Prince Rogers Nelson (Prince’s real name).

- Do you have Prince’s permission? No.

- Is your use for “purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research”? No. You are writing a novel.

- Is the purpose and character of the use commercial or noncommercial? Commercial.

- What is the nature of the underlying work you are reproducing? Is it highly creative and subject to strong copyright protection, or is it less creative or perhaps even not subject to copyright protection at all? This is a highly creative work that is entitled to strong copyright protection.

- Did you use the whole lyric or just a few words? You used the whole lyric.

- Will your use of the lyric cause Prince to lose money, e.g., people will not download the song on iTunes anymore? No, your use will likely not cause Prince to lose money.

Of all the fair use factors, you would only perhaps win on one of them, the last one, so if Prince sued you, you would likely not be able to successfully invoke the fair use defense. Other defenses may be available, but probably not fair use.

In each case where you wish to use someone else’s work, and wish to invoke the fair use defense, you should ask those seven questions.

Not all situations call for invocation of the fair use defense. For example, if you only want to use the title of another work, that’s not copyright infringement because titles and short phrases (fewer than ten words or so) are not subject to copyright protection. Similarly, facts are not protected by copyright, and you may use plain, unadorned, uncreative lists of facts without copyright infringement liability. If someone had, for example, prepared an alphabetical list of the fifty states, that list of facts (state names) is not protected under copyright law.

What about using quotations—is it okay?

A question like “is it OK” is hard for a lawyer to answer because in truth, the only way to know for sure if something is “OK” is by getting sued and then winning that lawsuit. Then, the judge has told you, in essence, “Yes, your behavior is OK.”

A better way to ask the question is: “If I get sued for quoting another book without seeking permission, what defenses may I posit in the lawsuit to increase the chances I will not lose?”

Answering that question is possible, and the answer is that if you copy ten or fewer words from another book you may likely be able to defend yourself under the doctrine that titles and short phrases are not subject to copyright protection. If you use more than 10 or 15 words, then you should ask those 7 questions above to determine how and if you might be able to invoke fair use as a defense if you get sued for copyright infringement. This is why I tell clients to always seek permission, and to remember that attribution alone is not permission.

The big question: How risk averse are you?

Anytime you use any third-party content without permission ( including quotes), you run the risk of getting sued. No amount of opining by me or another lawyer can change that fact. No one has to get permission from a judge or lawyer to sue you when you use their “stuff.”

Remember, under U.S. law:

- Fair use is just and only a defense you assert after you’ve been sued.

- Public domain is just and only a defense you use after you’ve been sued.

- An argument that the work you copied is not copyrightable subject matter because its total length is too short to merit copyright protection (10-15 total words or less) is just and only a defense you use after you’ve been sued.

The arguments about the length of the quotes all fall within the realm of one of more of these defenses, but that’s all they are—defenses you use after you’ve been sued.

So, again, to my point: how risk averse are you? If you are very risk averse, you should seek and obtain permission or not use the quotes since you have no control over if they will sue you. Yes, you may have one or more defenses in that lawsuit, but do you want to get sued at all?

If you are very risk tolerant, you may wish to use the quotes hoping they will never catch you and never sue you, and if they do sue, you trust that you can assert one or more of these defenses.

Also remember that attribution is not permission and does not create a defense. Also remember that celebrities (even dead ones) can sue you for something called “a right of publicity violation” in addition to suing you for copyright infringement.

Not saying you can’t. Also not saying you can. No one knows if you can until you get sued—and win.

Can I quote a famous person if they’ve said something publicly?

Remember the definition of copyright. Answering this question turns on whether someone owns a copyright in the spoken words, i.e., have the words been reduced to a tangible medium by someone? The fact that they’ve spoken the words publicly has no bearing on the analysis. Factors to keep in mind:

- If the quote is very old, say, more than 100 years old, even if it is in a tangible medium, it is likely that the copyright in that work has expired and that the quote has now entered the public domain.

- If you’re using the quote as a means to sell your book, you could get sued for a right of publicity violation. (However, it is typically defensible to use someone else’s name or likeness for news, information, and public-interest purposes, but that doesn’t always rule out a violation.) Right of publicity laws vary in each of the fifty states (and publishing something online is like publishing in all states), so you have to be careful.

The right of publicity can apply to people who are dead—it varies from state to state. In general, the right of publicity survives the person’s death, in some states for as long as 75 years after they die. Some states may even be longer!

What if I’m quoting or referencing facts?

Plain, unadorned facts are not copyrightable subject matter. For example, if Sue writes down a list of the fifty U.S. states and places that list in her book, I may copy that list exactly from her book and my defense, if she sued me, would be that such a list is an unadorned list of facts and thus are not subject to copyright protection. If, however, Sally, made the list creative and made a photo collage out of it or something, copying the collage might be copyright infringement, but the underlying facts themselves are still not protected by copyright.

What about quoting, paraphrasing, or linking to online work?

There are three issues here: quoting, paraphrasing, and linking, but there is nothing fundamentally different about online works that changes the analysis. Some human being wrote the words that appear online, and that human being (or her employer or her assignee) owns a copyright in the work. If someone copies and reproduces most or all of those words somewhere else online (a) without permission; (b) without being able to invoke the Fair Use Defense; (c) without being able to argue that the original words were not copyrightable subject matter; or (d) without invoking some other defense, then that is copyright infringement.

For example, the Huffington Post can argue that it is a news outlet, and news outlets get greater latitude to argue the Fair Use Defense. Also, you can summarize another’s works without committing copyright infringement if you do not literally replicate the exact words and all you do is convey the same underlying ideas.

Lastly, in most cases you may link to another’s work, as long as you do not literally copy and reproduce all or most of the actual words at the linked story on your site.

What about recipes from cookbooks?

To the extent the recipe is just a list of facts (amounts and ingredients), it is not subject to copyright protection. When a recipe or formula is accompanied by an explanation or directions, the text directions may be copyrightable, but the recipe or formula itself remains uncopyrightable.

What about using quotes from TV, film, or advertisements?

Television, film, and advertisements are all copyrightable subject matter, and copying from them without permission is subject to the same analysis.

Please comment or e-mail me at bfrazer@hawleytroxell.com if you have any questions.

Brad Frazer is a partner at Boise, Idaho law firm Hawley Troxell where he practices internet and intellectual property law. He is a published novelist ( http://www.diversionbooks.com/books/the-cure/ ) and a frequent speaker and writer on legal matters of interest to content creators. He may be reached at bfrazer@hawleytroxell.com .

[…] Today’s guest post is by attorney Bradlee Frazer, who has been a guest here several times before. […]

How does copyright influences writing about topics that are based on personal thoughts on sites like Blogger and Tumblr. I’ve read a lot of posts that inspire a line in my WIP. They are my ideas, but they are rooted (sometimes even using a similar key comparison) from a comment of someone else’s. Does that still qualify under copyright?

If it’s your original words and work, you don’t have much to worry about. You can be inspired by other work without infringing on it.

Jane is correct. Copyright law protects against copying literal words and pictures and other types of expression. Underlying ideas are not protected by copyright.

[…] Is It Fair Use? 7 Questions to Ask Before You Use Copyrighted Material by lawyer Brad Frazer […]

[…] Is It Fair Use? 7 Questions to Ask Before Using Copyrighted Material […]

[…] Today’s guest post is by copyright lawyer Brad Frazer. He has written two other posts for this site: Trademark Is Not a Verb and Is It Fair Use? 7 Questions to Ask Before Using Copyrighted Material. […]

There must be a tremendous amount of copyright infringement in the Blogosphere, based upon this information. I always wonder about downloading images off some aggregate site and then captioning the source, which is often nothing more than a website. I gather that would be an indefensible offense. Ack.

There is a lot of infringement, yes. But there’s also a culture of sharing, which is codified under Creative Commons, a growing alternative to copyright. More here: http://creativecommons.org/

So how is most fan fiction not a copyright infringement or some kind of intellectual property infringement? Just wondering, not intending to stir anything up.

It is an infringement. Many authors simply choose to look the other way.

Amazon recently launched an initiative to bring fan fiction to market in a way that’s legal: http://www.amazon.com/gp/feature.html?ie=UTF8&docId=1001197421

Very helpful post. Thanks.

Thank you, Shirley.

[…] Fair use allows you to use someone’s copyrighted work without permission. However, invoking fair use is not a straightforward matter. […]

I write nonfiction, and I request permission for everything I quote, even one sentence. Generally speaking, the quotes are used are to illustrate a point. I make a statement, then I use that quote to substantiate it. My experience in obtaining quotes is varied. I had a run-around from one publisher last year: filled out the form online, waiting 8 weeks to followup (as instructed). “Oh, you sent it to the wrong department; start over.” Repeat. Same answer. Submitted to a third department; no response to followup, so after 5 months, I gave up and didn’t use the quote. It can be an incredibly frustrating process. I’ve gotten some permissions in 24 hours or less. Most take weeks, some months. Some never respond. What I find odd is what the copyright holder (usually the publisher) requests. I’ve had several who only wanted to know page numbers and word counts, not specific quotes. I felt that was a disservice to the author, but I didn’t tell them that. Some want to know the context of how I’m using the quote, which I believe is the most critical factor. Most of what I request are quotes from trade books (not academic); also the occasional blog and song lyrics. I have only been asked to pay a fee once, and since the proceeds of the book benefits a charity I support, I was okay with that. I prefer to err on the side of caution, even though I’m not using quotes to denigrate the author or argue against any position of theirs. My lawyer asked me “how risk averse are you?” That decided it. 🙂 Viki

Thank you for your comments, Vicki. I ask my clients the same thing.

Thank you for your comments, Viki. I ask my clients the same thing.

- Get Legal Help

Ask SPLC: Can we use an image found online to illustrate a movie review?

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Q: We’re reviewing a new movie (or a new song, video game, TV show, book, etc.). Can we use an image we found online as an illustration?

A: Yes, but you have to be selective. As a general rule, most of material that you find online — whether it’s a photo, a story, music, etc. — is protected by copyright. If you want to use it, you’ll first need to obtain permission from the copyright owner (which may or may not be the operator of the website where you find the material). There is, however, one important exception called Fair Use. The fair use exception allows you to use limited portions of otherwise copyrighted material without permission when engaged in news reporting or when publishing commentary or reviews. To qualify, the copyrighted material that you use must be very closely tied to a bona fide news story, news survey, commentary or review. For example, in reviewing the latest Jennifer Lawrence movie, the fair use exception would allow you to use a still image from the movie or a scaled down image of the movie’s promotional material (for example, the movie poster) taken from the movie’s official website to illustrate your review. Fair Use would also not apply if you were to use a candid photo of Lawrence from People Magazine or or some other third-party website that is unconnected to the movie you’re reviewing. A candid photo of Lawrence walking down a Los Angeles street taken by a People Magazine photographer really has nothing to do with the movie and would likely not qualify as a Fair Use. If you want to use it, you’d need to obtain People Magazine’s permission.

Every week, Student Press Law Center attorneys answer a frequently asked question about student media law in “Ask SPLC.”

See previous Ask SPLC questions

Have a question you’d like answered? Tell us in the form below. (Not all questions will be chosen for Ask SPLC.)

If you need immediate help, contact our Legal Hotline .

- Share this article

- General Business

The Ultimate Guide to Fair Use and Copyrights for Filmmakers

- Posted by Ron Dawson

- August 30, 2017

- Updated March 3, 2021

Disclaimer: What you’re about to read is a compendium on fair use and copyrights pertaining to film and video production. I provide plenty of links and references to support the information. But it should not replace consulting an attorney with regard to your particular situation.

What are copyrights and trademarks?

Simply put, a copyright protects literary and artistic assets such as books, movies, videos, plays songs, photographs, etc. It should not be confused with a trademark which is a form of protection geared towards words and symbols. Trademarks are predominantly for the protection of a company’s intellectual property surrounding its brands and logos .

Unless explicitly expressed, whoever creates an image (photo or video), owns the copyright to that image. As long as that image does not infringe on another pre-existing copyright. That is why it is so important for production companies to have contracts in place with both clients and subcontractors with regards to the videos or photographs they create.

What is Fair Use?

The laws and regulations around fair use and copyrights are among the most confusing aspects of filmmaking. When can you use a song, photo, or movie clip, etc., and be within the bounds of the law? And what about all those thousands of videos uploaded to YouTube and Vimeo every week? How are they able to get away with what appear to be copyrights violations?

Section 107

According to the U.S. Copyright Office , Fair Use is “a legal doctrine that promotes freedom of expression by permitting the unlicensed use of copyright-protected works in certain circumstances . Section 107 of the Copyright Act provides the statutory framework for determining whether something is a fair use and identifies certain types of uses—such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research —as examples of activities that may qualify as fair use. Section 107 calls for consideration of the following four factors in evaluating a question of fair use :

- Purpose and character of the use. Including whether the use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes

- Nature of the copyrighted work (using parts of something more creative in nature, like a movie or book, has a weaker “fair use” argument than news footage or a technical article).

- Amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole (i.e. do you really need 3 whole minutes of “Avengers: Age of Ultron” in that video essay about superhero movies? Or will 3 seconds do?)

- Effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work (will the use hurt the original copyright holder’s ability to make money from the work that was copied?).

The thing that makes fair use so difficult is that it’s not a clear-cut law. It’s relatively open to interpretation. Unless you’re actually sued or challenged, you may never know 100% whether your use adheres to the law or not. In court, it’s the ruling judge’s discretion based on his or her own interpretation of the law.

Transformative Work

These four factors boil down into two important questions:

First, are you repurposing the material for use in a way other than its original purpose? That is what it means for a work to be transformative . This is a common term you will hear in discussions of fair use. A classic example would be the use of a movie clip within an educational context. A clip from Saving Private Ryan’s opening scene in a video essay on how Spielberg uses cinema verité is transformative. You’re taking the original media (a piece of entertainment) and using it for education.

Is it fair?

However, if you took those same clips and dropped them into your WWII short film for the express purpose of being a battle scene, well, in the words of Andrew Garfield to Jesse Eisenberg’s in The Social Network , “Lawyer up!”

The second question to ask is, “If your use is transformative, are you using the appropriate amount for that transformative purpose?” Usually, this amount is a small percentage of the whole. In the above example of using clips from Saving Private Ryan , you could probably justify as much as 30 seconds to adequately show use of cinema verité. However, if you uploaded the entire movie to your “education channel,” and you only had a few random voice-over commentaries about color grading or cinematography, that would be a harder fair use argument to support.

The fab four

F our uses of copyrighted material are particularly addressed and often protected by fair use: commentary, criticism, education, and news. So satires, parodies, video essays, documentaries, etc., will usually be protected by fair use. However, your interpretation of “education” my not be the same as a judge’s. Lots of videos are uploaded to YouTube with a disclaimer like “This video is uploaded for educational purposes.”

But it’s just the full video with no transformative aspect. (Sorry buddy, that doesn’t cut it.)

Remember, fair use is the kind of law wherein a transgression isn’t definitively determined until after the fact (i.e. you get sued). It’s not like running a red light or shooting a person in cold blood. These are acts that you know are illegal beforehand . So invoking “fair use,” leaves you open to litigation if there are no expressed licenses in place. That’s just a cold hard truth.

With that said, you don’t have to be gun-shy about it. There are resources and past precedents in place wherein you can feel confident in your application of fair use. We’ll get to those later.

No discussion of copyrights and fair use in filmmaking would be complete without addressing to some extent the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA). This was a law signed by President Bill Clinton on October 12, 1998 that implements two treaties by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). The law is detailed and contains five titles. In short, and paraphrasing Wikipedia speak, “It criminalizes production and dissemination of technology, devices, or services intended to circumvent digital rights management (DRM).”

These are the technologies used to access copyrighted digital media such as computer programs, movies, etc. A key aspect is this. DMCA is the limitation of liability for internet companies with regards to copyrighted works distributed on the internet. In other words, sites like YouTube and Vimeo aren’t liable for violations by people who use their services. As long as they respond immediately to copyright holders’ requests for action against violators. We’ll address this later as well.

Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices

I’ve studied and written about the topic of fair use a number of times in the past. A year ago I had the opportunity to interview Patricia (“Pat”) Aufderheide, one of the co-founders for the Center for Media and Social Impact . This is a non-profit organization, based in Washington D.C. It fights for universal copyright and fair use standards for films, videos, photographs, and even podcasts and radio.

My interview was part 2 of a 2-part podcast series on Fair Use in Filmmaking. (You can hear my full interview with her here ). CMSI has worked with legal scholars and media professionals to create a series of PDFs. These aim to standardize fair usage and provide a centralized resource for media makers. One of the documents is The Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use . Pat specifically worked with one of the world’s most renowned experts on fair use, Peter Jaszi , to put this document together.

Driving force

The primary impetus for Pat and Peter creating this document (and leading the research to create it) was their discovery of the number of documentary filmmakers who were avoiding the usage of material they believed would put them at risk. Some recurring refrains from documentary filmmakers included: don’t cover any topics related to popular music; don’t cover any politics that would require you to use news footage; don’t cover anything related to popular culture; etc.

All of these topics would require huge clearance budgets, some even greater than the budgets of the entire films themselves. As Pat puts it, “Filmmakers aren’t waiting for people to censor them. They’re just going ahead and doing it to themselves.”

Based on these findings, Pat and Peter got funding from the Rockefeller and MacArthur Foundations. This was used to fund the extended research and creation of the statement of best practices.

The beauty of the statement of best practices is that it was created in conjunction with working feature film documentary filmmakers and the world’s leading legal scholars , to define, in simple words, what kinds of uses of copyright works fall under fair use. I used and referenced it in the making of my short film documentary “Mixed in America: Little Mixed Sunshine.”

I even had Pat watch the short to get her take on it. The prologue, in particular, contains a number of clips from music videos, old movies, and contemporary movies. Alongside the credits for the clips used, I also reference the Fair Use statement. So technically, could Disney or HBO come after me? Yes. But I followed the guidelines and went the extra mile to credit the clips used. So, I’m not losing any sleep over the “Mouse House” giving me a call.

The Big Five Filmmaking Scenarios

Now I want to address the top five areas where filmmakers run into trouble when using other people’s copyrights. This is based on my discussion with Pat and additional research. I’ll be using a combination of case studies where copyright violators went afoul of the respective copyright holders. And cases where the fair use appears to be categorically intact.

We’re also planning to produce some more articles on the business side of filmmaking.

[one_line_cta]

Trademarks and logos

You know how some reality TV shows blur out the logos on clothes? I used to think that was because the reality show didn’t want to give free advertising to the brand. But that is not the case. It turns out that it’s because of copyrights.

The first part of my aforementioned podcast 2-part interview was with New York documentary filmmaker Salima Koroma. I was interviewing her for something completely different, and I asked her how her morning was going. (You know, regular pre-interview chit chat.) She said it was hectic because she was meeting with her lawyers to go over all the clearances she had to go back and get for her documentary “Bad Rap.” Clearances she had no idea were needed. This pre-interview “small talk” led into a 15+ minute conversation that became its own separate episode .

For example, there’s a shot of Times Square in her film. In the background are all of these logos, musical posters, billboards, etc. According to Salima’s attorneys, they ALL needed clearances.

This seemed crazy to me. If anything seemed to fit under fair use, a 2-second shot of “The Lion King” billboard in the background of a documentary seemed it. Not only was it brief, but it was also incidental. These types of occurrence helped to inspire the work behind the CMSI-created document of best practices. Salima’s attorney’s response was that it’s better to be safe than sorry and get the clearances. Even if something technically fits under “fair use.”

In 2011 I participated in The 48 Hour Film Project. To this day it remains the most challenging and one of the most rewarding filmmaking experiences of my life. One of the rules of the festival was making sure you had clearances for any copyrighted material in your film. Including paintings and photographs.

“But Ron, didn’t you allude to the fact that incidental appearances of copyrights or trademarks might be okay?” That is true. But 1) these weren’t documentaries we’re making, they were narrative pieces of fiction. And 2) the 48HFP distributes the winning films online and internationally. So they’re covering themselves. And in case you’re wondering, no, my film didn’t win. We missed the deadline by 30 minutes because needed to re-export the project.

Stock photos and footage

But it’s just not the use of photographs or paintings as incidental appearances you need to be mindful of. If you’re using them in the video (i.e. you’re dropping the image on your NLE timeline), you need to make sure you have clearances. There are many resources for legally licensing stock photos and footage (e.g. Pond5 , Getty Images , Video Blocks , and Shutterstock , to name a few).

There are also plenty of resources to obtain free stock imagery. Sites like Unsplash and StockSnap have utilized Creative Commons Zero licenses. This is the most permissive of the creative commons licenses (see below for the full description of Creative Commons). It’s essentially just one “notch” below the public domain. A CC0 license allows you to use the copyrighted work any way you want. Without the need to even credit the copyright holder . I’ve frequently used Pixabay to find free stock video footage. (Keep in mind, you get what you pay for.)

Movie and television clips

As I mentioned above, I used clips from various movies and TV shows for my short film documentary. Perhaps the most common area where you might see this example of fair use is in video essays . Essayists like Tony Zhou (“ Every Frame a Painting ”) and Evan Puschak (“ Nerdwriter ”) garner millions of views from their respective video essays. And they all include movie clips, photographs, television clips, and in some cases, even music .

Yet, YouTube has not invoked DMCA rules to take their videos down. And, on top of that, these guys are making thousands of dollars per video (as of this writing, Tony’s Patreon campaign for “Every Frame a Painting” yields over $7,700 per video).

One of the tests for fair use adherence is whether the copyrighted material is used for commercial gain. It’s clear here that these guys have a commercial benefit from their use. Evan not only makes a few thousand dollars per video from his Patreon, but he also gets corporate sponsorship from companies like Squarespace.

But video essays are the quintessential example of fair use in terms of both education and critical commentary. That is the essence of a video essay. Based on the transformative use, the amount of the copyrighted material used, and the fact that this use is not hurting the commercial viability of the copyright holders, they’re protected.

Now, I cannot say for 100% certain those guys don’t actually have licenses with all parties whose copyrighted works are being used. But, I’m going to go out on a limb and say that a guy from Philly making videos in his living room and earning $3,000 per video has not paid licensing fees to a dozen or so different conglomerates.

I have another perfect example of this usage where I do know for sure the filmmaker did not have license or permission.

Kirby Ferguson is the filmmaker behind “ Everything’s a Remix .”

https://vimeo.com/14912890

This short film series has garnered millions of views and Kirby has even spoken on the TED stage. Back in 2010 I interviewed him for one of my older podcasts, and I later contacted him about his use of Tarantino movie clips, as well as music usage (where he used parts of famous songs to illustrate, coincidentally, how musicians sample songs). Kirby told me he did not get permission from the studios or labels to use those clips.

You know what he did do? He followed the guidelines of the CMSI’s The Documentary Filmmakers’ Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use . In fact, he was the first person to ever refer me to the work of Pat and the CMSI.

Intellectual Property

Intellectual Property (or “IP”) is a physically intangible item of value based on ideas, computer code, trademarks, copyrighted stories and characters, etc. For many companies, their IP is their primary product. So, it stands to reason, they go out of their way to protect that IP.

But filmmakers are nerds. (You’re reading an article by a huge one. A nerd that is). And we love our sci-fi and fantasy. Hence the fan film .

Fan service

YouTube contains tens of thousands of fan films. Media created by fans of a piece of IP wherein they use that IP to make their own films. (Some have jokingly argued that this season of “Game of Thrones” is a glorified “fan film” vs. an adaptation because George R.R. Martin hasn’t finished the final two books in his famous Song of Ice and Fire series upon which the HBO series is based. But, again, don’t get me started.)

Based on my understanding of fair use and copyright law, just about every single instance of a fan film is a copyright violation . They are not necessarily making money from these films; but for the most part, the films are not making any kind of commentary or critique on the IP. They are not transformative in purpose either (i.e. education). They are entertainment for entertainment’s sake, just like the original IP.

Now, some IP holders encourage fan films and allow a vibrant fan film community to flourish. Fan films keep the culture alive and fans excited about the traditional IP. Lucasfilm is a perfect example of that in how they’ve responded to and embraced the “Star Wars” fan film community. (One of the most celebrated “Star Wars” fan films recently was last year’s “Darth Maul – Apprentice” with over 14 million views as of this writing.)

However, some IP holders of sci-fi space stories are not as forgiving.

The Battle of Axanar

Earlier this year, after a legal battle that lasted nearly a year, Paramount Pictures and CBS (the owners of “Star Trek”) won a judgment against Axanar Productions . Axanar had raised over $1 million in crowdfunding to produce a feature-length version of it’s popular short film “ Prelude to Axanar .” Axanar claimed fair use. A U.S. district court judge said no .

Axanar and CBS/Paramount eventually reached a settlement whereby Axanar agreed to substantially change the length and content of their film (which naturally put them in a bit of a bind as they raised over a million dollars to make a feature).

What made this case particularly stand out was the fact that there have been “Star Trek” fan films literally for decades. Dating back as early as the 80s. Even Axanar’s original film “ Prelude to Axanar ” was made with no objection from CBS/Paramount and as of this writing has over 3 million views.

Don’t get them started

What set the studio off, in this case, was the scope of this new project. In addition to the feature-length and the $1 million+ budget, it stars well-known actors like Richard Hatch (Apollo from the original “Battlestar Galactica” and Tom Sarek in the SyFy Channel remake), Gary Graham, and Kate Vernon (also from SyFy’s “BSG”). In the eyes of CBS/Paramount, the feature-length fan film with those production values and cast, was too much. (especially with the new “Star Trek: Discovery” series on the horizon).

The uproar from the fans was huge. Needless to say, they were pissed. The fan community is what kept “Star Trek” alive, going as far back as the 70s. So many saw this lawsuit as an affront on the fan loyalty and devotion to the franchise.

In an effort to support the fan film community and encourage the continued production of fam films, CBS/Paramount created a set of guidelines for future fan film productions . They put limits on things like the amount of money raised (must be less than $50,000), the running time (less than 15 minutes), and that films must star and be produced by amateurs. Many feel that those guidelines are too limiting. Only time will tell how it all plays out.

The Wrath of Kahn

Joseph Kahn is one of the most prolific music video filmmakers on the planet. He is the go-to guy for Taylor Swift. He’s insanely talented and has the attitude to match.

About 2.5 years ago, he and producer Adi Shankar released what some have described as the most epic Power Rangers film ever made. Based on the popular children’s series owned by Saban Entertainment, Kahn and Shankar’s version is dark, gritty, and absolutely NOT FOR KIDS. This is due to sex, graphic violence, drug use, language, dark themes—pretty much everything you can put in a film that makes it NSFW.

Recognizable talent

The production values are top-notch, from the CGI to the choreography; and even the acting is very good. It too stars well-known actors, namely Katee Sackhoff (yet another SyFy BSG alum), and “Dawson” from the WB hit “Dawson’s Creek”, James Van Der Beek.

A quick response

It did not take long for the short to go viral. Saban, who at the time was in pre-production for a new Power Rangers film (released last year), ordered to have the video removed from Vimeo. Kahn was pissed.

Remember the DMCA I mentioned above? This is where it came into action. Under the regulations of the DMCA, Vimeo was required by law to remove it at the behest of Saban. And they retorted as such to Kahn on Twitter.

They released a formal statement on their blog where they said:

“The video creator feels that the video is covered by Fair Use based on the fact that it is non-commercial and satirical. We agree that an argument for fair use can be made, but the DMCA law does not give content hosts (like Vimeo) permission to disregard a takedown notice simply because of the presence of one or more fair use factors. This is a legal matter between the copyright holder and the video creator.”

Making a case

Kahn and Shankar were making the case that this video falls under Fair Use because they were not making any money from it, and they saw it as a satirical commentary on kids and violence. IMHO, I called B.S. on both, and I think Saban had a strong case against Kahn regarding this film.

- Kahn may not have been paid for the film, but you don’t have to be a Harvard business graduate to know that a film like this, and the publicity it was getting, will be worth more to him long-term than any director fee he would’ve earned. Filmmakers make these kinds of films all the time precisely for the marketing value they bring. All an attorney has to do is add up the press impressions Kahn had gotten on sites like Mashable, i09, HitFlix, and pretty much every major tech, sci-fi and movie website and calculate what ads on those sites would cost to come up with a figure.

- It’s obviously not an educational or “news” item.

- Lastly, I don’t think this kind of film really qualifies as a “commentary” on Power Rangers, or even a parody. It is a serious drama using the characters from the universe. In Kahn’s own words, he made it because he wanted to see a “good” Power Rangers film; not as a critique or commentary. Shankar released a video which gives his reasons why he made it . But the comedic nature of this video clearly shows there was no sincere desire to make a serious commentary about children and violence. At the end of the day, they wanted to make a kick-ass Power Rangers film. And without a doubt, they did.

Split decision

I loved that Power Rangers “fan film.” It was truly a marvel. But it really wasn’t fair use. As fan fiction, few reach the level of sophistication of the Kahn film. But if that fiction goes against the brand of the art in question, the copyright holder should have the right to have it removed, no matter how annoying or frustrating it might be even to the very fans for which it was made. IMHO, we as artists should actually be defending that right, not fighting against it (as many people did when Vimeo first took it down).

Ultimately Saban and Shankar/Kahn reached an agreement to reinstate the film if a disclaimer was added. I actually think that’s was pretty generous on the side of Saban. (And based on the dismal performance of their official Power Rangers movie, they may want to look into Kahn doing a feature-length version of his fan movie. One that is more kid-friendly, of course).

The last of the big five areas of fair use scenarios for filmmakers I want to cover is music. Oh boy. This will be fun.

No area of confusion on this issue is perhaps more misunderstood than music . You need look no further than the hundreds (if not thousands) of professionally shot wedding videos edited with copyrighted music. Or the countless epic short films on YouTube with Hans Zimmer or Michael Giacchino “scores.” Many novice filmmakers assume that if a video is “not for commercial purposes” and/or if the music was purchased on iTunes, then that clears them or their conscience. Unfortunately, it doesn’t (well, it may clear their conscience, but it definitely doesn’t clear them legally).

Within parameters

Music does indeed fall under fair use, and so your use of it must also fit within the parameters mentioned above. The problem is, most of the use of music in such film and video is a copyright violation. They use someone else’s music, unlicensed, in the manner for which it was originally purposed. There is no transformative use or commentary on the music itself.

In order to legally use music in your film or video, you need two types of licenses: a master (also known as mechanical) use license (controlled by the record label) and a synchronization (or sync) license (controlled by the publisher). The mechanical use license gives you rights to the song from the originator; the sync license gives you the right to the specific version of the song and set it to a film or video. In many cases, the same company represents the publisher and the label. But if they don’t, you’d have to arrange for licenses with each entity separately.

Years ago, The Harry Fox Agency was a centralized resource for getting all the appropriate licenses for use in films. They have since given up managing sync licenses and focus on mechanical use licenses.

Raising the stakes

Within the past 7 years, record companies have raised the stakes when it comes to illegally using their music . Two wedding videographers I know personally had rather high-profile public lawsuits by EMI when wedding videos they produced for celebrities went viral. As most wedding videos do, theirs had copyrighted music. Each settled out of court for amounts in the 5-figure range; that’s A LOT of money for a small wedding filmmaker to shell out. If you are a wedding and event videographer, don’t risk it. Fortunately, there are alternatives to using music illegally.

Music License Alternatives

Unless you have a huge budget, you will not be able to get popular music for that really cool short film or feature film. Thankfully, there is a growing number of sites where you can legally license music from a wide variety genres . Some of these sites even have mainstream popular music.

The length and cost of the license will depend on factors such as the intended audience (wedding, corporate, personal), the size of the audience, and the intended distribution (theatrical, online, DVD/Blu-ray, broadcast). For theatrically-released features, you will typically need to arrange some sort of custom license (which undoubtedly will cost you an arm and a leg).

Royalty-free? Or rights-managed?

The most important thing to keep in mind is that some of these sites have royalty-free licenses, and others have what’s called “rights-managed” licenses.

- Royalty-free is essentially “buy once, use indefinitely.” You can use royalty-free songs in just about all manners of production, for as many productions, for as long as you like. A few of the most popular royalty free sites I’m familiar with include Pond5 , PremiumBeat , and AudioJungle . You’ll notice that the rates on these sites can be as little as $12 to $40.

- Rights Managed licenses are more restrictive. They are typically for one song and one production. Whereas royalty-free sites have one price per song, rights-managed sites will change the price based on the license. The same song my cost $60 for use in a wedding video, but $500 if used in a local cable TV commercial, or a corporate promo video for a company with 50 or more employees. The rights managed sites I come across more often are Marmoset Music , Song Freedom (now FyrFly), MusicBed , and Triple Scoop Music .

As an avid podcaster who pretty much does it as a passion project, I don’t have the budget to license music for the episodes I produce. So I’ve turned to a resource that is not only great for music but applicable to all forms of copyrights: creative commons .

Creative Commons

Creative Commons is an organization dedicated to providing worldwide licensing for copyright holders who want the ability to freely and easily license their work to others. When you use a copyrighted work under Creative Commons, you agree to one of six types of licenses.

Creative Commons licenses

- Attribution (CC BY): This license lets others distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the copyright holder’s work, even commercially, as long as they give credit for the original creation.

- Attribution-ShareAlike (CC BY-SA): This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon the copyright holder’s work, even for commercial purposes, as long as they give credit and license their new creations under the identical terms. All new works will carry the same license, so any derivatives will also allow commercial use. This is the license used by Wikipedia and is recommended for materials that would benefit from incorporating content from Wikipedia and similarly licensed projects.

- Attribution-NoDerivs (CC BY-ND): This license allows for redistribution, commercial and non-commercial, as long as it is passed along unchanged and in whole, with credit to the copyright holder.

- Attribution-NonCommercial (CC BY-NC): This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon the copyright holder’s work non-commercially, and although their new works must also acknowledge the copyright holder and be non-commercial, they don’t have to license their derivative works on the same terms.

- Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA): This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon the copyright holder’s work non-commercially, as long as they give credit and license their new creations under the identical terms.

- Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND): This license is the most restrictive, only allowing others to download the copyright holder’s works and share them with others as long as they give credit. They can’t change them in any way or use them commercially.

As I mentioned earlier, I use CC music in my podcasts, but I also used it in my documentary short.

Creative Commons does extremely important work. It allows content creators to share and use copyrighted material in a way that is fair and equitable to both the copyright holders and the users of those copyrights. You can learn more about them at CreativeCommons.org .

As a filmmaker (documentary or otherwise) who wants to use other people’s copyrights in your work, there are a number of things you can do to protect yourself:

- Use the Statement of Best Practices : When CMSI did a study two years ago of documentary films over the previous ten years that had implemented the guidelines of fair use outlined in this document, they found the overwhelming majority of them had no problems with broadcasters, insurers, or lawyers.

- Where budgets allow, go ahead and get the clearance . You may recall my recent interview with the editors of HBO’s documentary series “The Defiant Ones”, about the careers of Dr. Dre and Jimmy Iovine. The music licensing budget for that 4-part series was the highest in HBO’s history.

- CC Yourself : when looking for music, photos, or even stock footage for your video needs, if you don’t have the budget, start with Creative Commons sites. You can even start your search directly from the CC Search Engine .

I’ve tried to give you an exhaustive list of resources and case studies related to fair use and copyright usage so that moving forward, you can make informed decisions. But I’m sure there are other resources I may have missed. What are some of your favorite sites for finding and using copyrighted material legally in productions? Please share.

[Header image Photo by Claire Anderson on Unsplash ]

Ron is an award-winning video producer with over 25 years experience telling stories in the video medium. He's a coach, speaker, and author of “ReFocus: Cutting Edge Strategies to Evolve Your Video Business." Ron was also the host and producer of Radio Film School a podcast described as " This American Life for Filmmakers." You can follow him on Twitter @BladeRonner .

You might also like...

The ten commandments of working with editors.

- Posted by Zack Arnold

- October 29, 2018

Essential Organization Habits for The Successful Editor

- Posted by Clara Lehmann

- December 20, 2017

What 15 Years of Writing Videography Contracts Has Taught Me

- April 21, 2017

CALL US! (310) 421-9970

Using film clips in movie reviews – entertainment law asked & answered.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 3:40 — 5.0MB)

Subscribe: RSS

TRANSCRIPT: www.firemark.com

Brief Explanation of Fair Use

YouTube’s Strike Policy

Tim wrote in with a question about his movie reviews channel on YouTube.

I'm Entertainment Lawyer Gordon Firemark, and this is Asked and Answered, where I answer your questions, so you can take your business in entertainment and media to the next level! My answer in just a sec…

So here's what Tim wrote in the comments on my YouTube channel…

“A friend and I want to start a YouTube channel that reviews movies. We want to give facts, actors, and other details about the featured movie, as well as put 2-3 short clips from that specific movie. How can we do this legally and without getting a copyright strike on our YouTube channel?”

First off, the best way to get questions to me is via https://firemark.com/questions , that way you get notified as soon as I post an answer via video. And you get subscribed to my free email newsletter, where I provide all kinds of other free, useful information.

OK, here goes…

Movie Reviews in electronic media have a long history of using clips, stills and other material from the the films they're reviewing. TV review shows, radio reviews, and what have you… All of them have done this. In most cases, the studios have provided the clips as part of the press-kit for the films. After all, they want to get these films out there for the public to know about, so they'll come and see them. That's how the studios make money.

So.. Start by contacting the major studios and film distributors and asking to be added to the circulation list for their Electronic Press Kits (EPK for short). Sometimes you can find the EPKs on the movie websites, so have a look around

Now if you get the clips this way, then you'd be operating under a license from the copyright owner… And as long as you comply with whatever terms they require, you should be fine.

But, small snippets used in the context of a bona-fide movie review will most likely constitute FAIR USE, and therefore NOT copyright infringement. The trouble is, it's risky to rely on Fair Use in these situations, since that determination is typically made on a case-by-case basis by a Judge or Jury… Which means you're already embroiled in a lawsuit by the time you get to present the defense.

You may also want to have a look at my “Brief Explanation of Fair Use” video: https://firemark.com/fairuseinbrief for a bit more detail.

The good news is that a recent court ruling requires copyright owners to make a good-faith determination about fair use BEFORE issuing a DMCA takedown. AND, if they do issue a takedown, you'd have a valid basis to issue a counternotice, and get the video reinstated.

YouTube’s strike policy is somewhat flexible, and they've recently indicated that they'll even help support users who have fair use claims. (see http://www.zdnet.com/article/google-announces-legal-support-for-youtube-fair-use-copyright-battles/ )

So, my advice is: See if you can get official press/PR copies of the footage you want to use, and be careful to comply with the film owners' requirements, but even if you're not able, consider whether your use falls within the fair use defense/exception to copyright infringement, and document your decision making process.

You may want to consider getting some Errors and Omissions insurance to cover you and legal fees if you're sued.

And, of course, contact me if you need further analysis and advice. I can prepare a formal opinion letter about your videos.

So if you have any question about entertainment law or business that you’d like to see answered here, send it over by or visiting https://firemark.com/questions

=============

This is intended as general information only and does not establish an attorney-client relationship. It is not a substitute for a private, independent consultation with an attorney selected to advise you after a full investigation of the facts and law relevant to your matter. We will not be responsible for viewers'’ detrimental reliance upon the information appearing in this feature.

Sorry, comments are closed for this post.

View our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use

- All Articles

- Latest Issue

Wed, 03/25/2009

Clip Show: A Practical Guide to Fair Use

By Tamsin Rawady

Filmmaking is a constant struggle between creative vision and budgetary restraint. In the production of our documentary, Bigger Stronger Faster , no issue better demonstrated this tug-of-war than our use of archival footage. As writers/producers, we quickly learned about an important tool called the Fair Use Doctrine, which could help us balance the conflict between our goal of being legally and fiscally responsible, and telling the most honest and accurate version of our story.

The first problem we encountered is that it seemed like Fair Use was sort of an urban legend: Does it really exist? Can you really use archival clips without licensing them? And does anyone understand how this all works? We spoke with many producers, who seemed to fall into two camps: those who never evoke the Fair Use Doctrine because they heard it is so complicated to wage your legal argument, and those who cavalierly claim “Fair Use!” for every clip in their film and then cross their fingers. Three years later, we managed to finish, sell and distribute a film containing over 800 archival clips with hundreds of cases of the Fair Use Doctrine being practiced, and we decided to share some of the practical lessons we learned about Fair Use with other filmmakers.

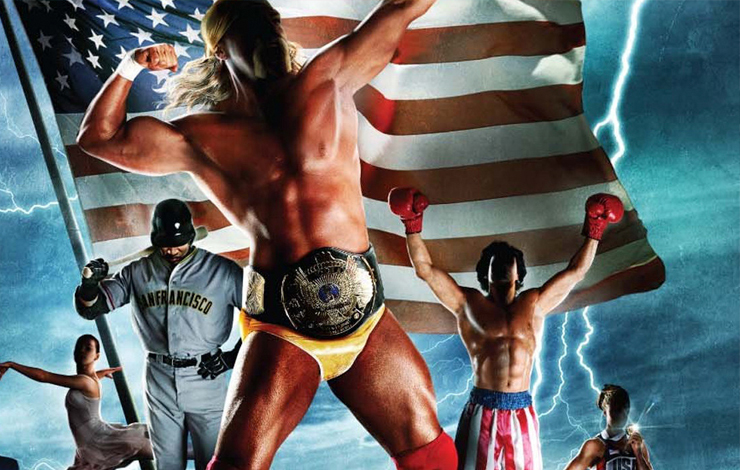

Bigger Stronger Faster is the story of our director, Chris Bell, and his two brothers who grew up during the ’80s under the influence of muscular action stars like Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone and Hulk Hogan. The American Way was being projected to these young, impressionable boys as a win-at-all-cost mentality, and we were interested in how that affected their decision to use performance-enhancing drugs later in life. To truly examine the impact popular culture had on these three brothers, we knew we had to use archival footage from the time period. We also knew we could never effectively tell this story without actually showing clips from professional sports. As we broke down our wish list of archival footage, it was full of movie and television clips from some of the most high-profile and notoriously litigious corporations in the world, including the International Olympic Committee, Major League Baseball, the National Football League and World Wrestling Entertainment—all of whom did not want their brand associated with a movie about performance-enhancing drugs. When they all denied us the right to license footage from them, it was easy to become discouraged.

Thankfully, we had a dedicated archival team (Andy Zare, Pamela Aguilar and Susan Ricketts), and a legal team that specializes in the application of the Fair Use Doctrine. You must find an attorney familiar with Fair Use. In our case, attorneys Michael Donaldson and Lisa Callif (Donaldson & Callif) soon became two of the most valuable members of our team; additional critical advice came from veteran archive producers Prue Arndt, Deborah Ricketts and Barbara Gregson. What follows is a list of steps and tips that we learned along the way.

The Rough Cut—Organizing the Footage

The first decision we had to make was whether to include clips in our rough cut that we knew we could never license. One philosophy is to only use timecoded clips from legit archive houses so that when it’s time to picture-lock and finish your film, the process is relatively straightforward. The other philosophy (which we adopted) is to explore any and every possible editorial option—clearances be damned! We decided it was more important to edit the film without creative restrictions, and thus we ended up digitizing footage from traditional archive sources whenever possible, but also from every other imaginable source: DVDs, YouTube videos, TiVo’d news programs, old VHS tapes, etc. But it was far from reckless abandon. Our archival team implemented an organization system to timecode and track every piece of footage through a Filemaker Pro database. Since this approach resulted in hundreds of hours of archival footage, we had a team of interns constantly logging new footage into our database, and an apprentice editor working the night shift digitizing footage.

The Legal Review

Once we had a relatively coherent rough cut, we output a timecoded DVD with a corresponding log of the archival clips in the cut, identifying the copyright holder, current licensing status, and whether we anticipated making a Fair Use argument for the clip. This DVD/log went to Donaldson & Callif for review. They examined the context of every archive clip we had marked as Fair Use, and gave us their legal opinion on the strength of each case. In all honesty, we were anticipating an “Us-vs-Them” kind of relationship where the lawyers were going to try to stop us from exerting our creativity with an overly conservative approach to the law. On the contrary, the goal of our attorneys was to exercise the Fair Use Doctrine as often as possible—not just as a Plan B if the clip license is denied. If our use of a clip falls within the definition of Fair Use, we would use the doctrine—and quite often not even approach the copyright holder at all.

Fair Use or Not Fair Use?

This is not to say that our attorneys let us off easy. They denied Fair Use for as many archive clips as they approved. They were very strict about the necessity for the clip to be contextualized, rather than just an entertaining cutaway. For example, in one scene we explore the use of amphetamines by Air Force pilots. As a fun introduction, we tried to use that memorable clip from Top Gun : “I feel the need for speed !” Funny? Yes. Fair Use? No. Our attorneys told us that if we wanted to use the clip here, we would have to obtain the license from the movie studio as well as the talent releases from the actors in the scene (including Tom Cruise).

Making the Case—and the Story—Stronger

Donaldson & Callif provided not just a list of approvals and denials, but also notes about how we could alter the rough cut in order to make Fair Use arguments. Does that sound like creative notes coming from your lawyer? Well, we were surprised to learn that by accepting their advice and better contextualizing a clip, we not only waged a better Fair Use argument, but we quite often made a clearer story point. For example, there was a clip of Hulk Hogan delivering his wonderfully over-the-top motto: “Train, say your prayers and eat your vitamins…Be a real American!” We thought the clip was hilarious, but on the advice of our attorneys, we added voiceover before the clip explaining how much that motto meant to Bell and his brothers as children. The result was a stronger defense for Fair Use as well as a much more meaningful scene.

When to Hire an Attorney

Another important point to understand about our relationship with our Fair Use attorneys is that we brought them into the process very early—six months before we finished editing. It was essential to get their advice while we still had time to re-cut scenes—even re-think scenes, if need be. It would have been an enormous mistake to limit the value of their input by waiting until picture lock before involving them.

The Downside of Fair Use

One of the benefits of licensing a clip, in lieu of applying Fair Use, is that you also get access to a high-quality master. With Fair Use, you are on your own to find the highest-quality copy of the footage, which can take weeks and requires a great deal of manpower. We ended up “mastering” from sources as degraded as old VHS recordings of TV shows that we bought second-hand and from low-res online downloads for which no master source even existed. Post-production became more difficult as we had to convert and up-res all of these different formats to high-def. In a few cases, we actually decided to pay for the license of clips for which we knew we could employ Fair Use, simply to get the high-quality master.

E&O Insurance

E&O Insurance is another important factor when considering Fair Use, as there are currently only a few insurance providers that will cover it, and it’s safe to assume that they will need a little extra explanation before they dive in—and may even ask you to alter your edit before they will agree to insure your film. Our Fair Use attorneys were vital in these steps as well.

The Distribution Stage

When it comes time to sell your film, bear in mind that many distributors are still clueless about the application of Fair Use. We would recommend allowing money in your budget for your attorney to talk through your archive clearances with your distributor’s legal department. The Fair Use Doctrine is also a little more difficult to apply when marketing the film. This makes it tricky when your distributor is producing the trailer, for example. You’ll need to approve the trailer to make sure they are not using any Fair Use footage out of context, lest it lead to a lawsuit from the copyright holder and affect the release of your film. Remember, as the independent producer, you are responsible for claims made against your film, not your distributor.

When Copyright Holders Attack

After the film has been released, expect to get calls from copyright holders upset about your use of their footage. Most copyright holders have never heard of Fair Use, and you should allow some money in your budget to have your attorney call and talk through the evidence you have. If you have been responsible in your Fair Use decisions, most complaints will only require one phone call from your attorney to make them go away. We encountered a handful of copyright holders from some very large corporations who were not pleased that their clips had been used in our film, but we were well prepared by our attorneys and had no problem avoiding any legal claims.

Know Your Rights

On a final note, Fair Use is still an area of law that only a limited number of professionals have a solid handle on. The legal departments of the major studios and television networks are prone to roll over and settle with copyright holders, rather than defend their Fair Use cases. This makes it especially difficult for the independent producer, but if filmmakers were more confident in their knowledge of the Fair Use Doctrine, they could tell their stories as truly intended. In truth, it can be very stressful to challenge a copyright holder’s right to their own footage, but it can be done, and your best resources are a good attorney—and a strong antacid.

Tamsin Rawady and Alex Buono are narrative and documentary writer/producers based in Venice, CA. Their production company is Third Person (www.thirdpersonfilm.com).

Digital Media Law Project

Legal resources for digital media, search form.

The policy behind copyright law is not simply to protect the rights of those who produce content, but to "promote the progress of science and useful arts." U.S. Const. Art. I, § 8, cl. 8 . Because allowing authors to enforce their copyrights in all cases would actually hamper this end, first the courts and then Congress have adopted the fair use doctrine in order to permit uses of copyrighted materials considered beneficial to society, many of which are also entitled to First Amendment protection. Fair use will not permit you to merely copy another’s work and profit from it, but when your use contributes to society by continuing the public discourse or creating a new work in the process, fair use may protect you.

Section 107 of the Copyright Act defines fair use as follows:

[T]he fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include -- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; the nature of the copyrighted work; the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

Unfortunately, there is no clear formula that you can use to determine the boundaries of fair use. Instead, a court will weigh these four factors holistically in order to determine whether the use in question is a fair use. In order for you to assess whether your use of another's copyrighted work will be permitted, you will need an understanding of why fair use applies, and how courts interpret each part of the test.

The Four Fair Use Factors

1. Purpose and Character of Your Use

If you use another's copyrighted work for the purpose of criticism, news reporting, or commentary, this use will weigh in favor of fair use. See Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music , 510 U.S. 569, 578 (1994). Purposes such as these are often considered "in the public interest" and are favored by the courts over uses that merely seek to profit from another’s work. Online Policy Group v. Diebold, Inc. , 337 F. Supp. 2d 1195, 1203 (N.D. Cal. 2004). When you put copyrighted material to new use, this furthers the goal of copyright to "promote the progress of science and useful arts."

In evaluating the purpose and character of your use, a court will look to whether the new work you've created is "transformative" and adds a new meaning or message. To be transformative, a use must add to the original "with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message." Campbell, 510 U.S. at 579. Although transformative use is not absolutely necessary, the more transformative your use is, the less you will have to show on the remaining three factors.

A common misconception is that any for-profit use of someone else's work is not fair use and that any not-for-profit use is fair. In actuality, some for-profit uses are fair and some not-for-profit uses are not; the result depends on the circumstances. Courts originally presumed that if your use was commercial it was an unfair exploitation. They later abandoned that assumption because many of the possible fair uses of a work listed in section 107's preamble , such as uses for purposes of news reporting, are conducted for profit. Although courts still consider the commercial nature of the use as part of their analysis, they will not brand a transformative use unfair simply because it makes a profit. Accordingly, the presence of advertising on a website would not, in of itself, doom one’s claim to fair use.

If you merely reprint or repost a copyrighted work without anything more, however, it is less likely to qualify for protection under this prong. If you include additional text, audio, or video that comments or expands on the original material, this will enhance your claim of fair use. In addition, if you use the original work in order to create a parody this may qualify as fair use so long as the thrust of the parody is directed toward the original work or its creator.

Moreover, if the original work or your use of it has news value, this can also increase the likelihood that your use is a fair use. Although there is no particular legal doctrine specifying how this is weighed, several court opinions have cited the newsworthiness of the work in question when finding in favor of fair use. See, e.g., Diebold, 337 F. Supp. at 1203 (concluding "[i]t is hard to imagine a subject the discussion of which could be more in the public’s interest”), Norse v. Henry Holt & Co., 847 F. Supp. 142, 147 (N.D. Cal. 1994) (noting "the public benefits from the additional knowledge that Morgan provides about William Burroughs and other writers of the same era").

2. Nature of the Copyrighted Work

In examining this factor, a court will look to whether the material you have used is factual or creative, and whether it is published or unpublished. Although non-fiction works such as biographies and news articles are protected by copyright law, their factual nature means that one may rely more heavily on these items and still enjoy the protections of fair use. Unlike factual works, fictional works are typically given greater protection in a fair use analysis. So, for example, taking newsworthy quotes from a research report is more likely to be protected by fair use than quoting from a novel. However, this question is not determinative, and courts have found fair use of fictional works in some of the pivotal cases on the subject. See, e.g., Sony Corp. v. Universal City Studios, Inc. , 464 U.S. 417, 456 (1984).

The published or unpublished nature of the original work is only a determining factor in a narrow class of cases. In 1992, Congress amended the Copyright Act to add that fair use may apply to unpublished works. See 17 U.S.C. § 107 . This distinction remains mostly to protect the secrecy of works that are on their way to publication. Therefore, the nature of the copyrighted work is often a small part of the fair use analysis, which is more often determined by looking at the remaining three factors.

3. Amount and Substantiality of the Portion Used

Unfortunately, there is no single guide that definitively states how much of a copyrighted work you can use without copyright liability. Instead, courts look to how such excerpts were used and what their relation was to the whole work. If the excerpt in question diminishes the value of the original or embodies a substantial part of the efforts of the author, even an excerpt may constitute an infringing use.

If you limit your use of copyrighted text, video, or other materials to only the portion that is necessary to accomplish your purpose or convey your message, it will increase the likelihood that a court will find your use is a fair use.

Of course, if you are reviewing a book or movie, you may need to reprint portions of the copyrighted work in the course of reviewing it in order to make you points. Even substantial quotations may qualify as fair use in "a review of a published work or a news account of a speech that had been delivered to the public or disseminated to the press." Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enters. , 471 U.S. 539, 564 (1985). However, substantial quotations from non-public sources or unpublished works do not enjoy the same protections.

4. The Effect of Your Use Upon the Potential Market for the Copyrighted Work

In examining the fourth factor, which courts tend to view as the most important factor, a court will look to see how much the market value of the copyrighted work is affected by the use in question. This factor will weigh in favor of the copyright holder if “unrestricted and widespread” use similar to the one in question would have a “substantially adverse impact” on the potential market for the work.

Although the copyright holder need not have established a market for the work beforehand, he or she must demonstrate that the market is "traditional, reasonable, or likely to be developed." Ringgold v. Black Entm't TV , 126 F.3d 70, 81 (2d Cir. 1997). An actual effect on the number of licensing requests need not be shown. The fact that the original work was distributed for free, however, may weigh against a finding that the work had publication value. See Nunez v. Caribbean Int'l News Corp. , 235 F.3d 18, 25 (1st Cir. 2000). Likewise, the fact that the source is out of print or no longer sold will also weigh in favor of fair use.

The analysis under this factor will also depend on the nature of the original work; the author of a popular blog or website may argue that there was an established market since some such authors have been given contracts to turn their works into books. Therefore, a finding of fair use may hinge on the nature of the circulated work; simple e-mails such as those in the Diebold case (discussed in detail below) are unlikely to have a market, while blog posts and other creative content have potential to be turned into published books or otherwise sold. In addition, the author of a work not available online, or available only through a paid subscription, may argue that the use in question will hurt the potential market value of that work on the Internet.

Assessing the impact on a copyrighted work’s market value often overlaps with the third factor because the amount and importance of the portion used will often determine how much value the original loses. For instance, the publication of five lines from a 100 page epic poem will not hurt the market for the original in the same way as the publication of the entirety of a five-line poem.

This fourth factor is concerned only with economic harm caused by substitution for the original, not by criticism. That your use harms the copyright holder through negative publicity or by convincing people of your critical point of view is not part of the analysis. As the Supreme Court has stated:

[W]hen a lethal parody, like a scathing theater review, kills demand for the original, it does not produce a harm cognizable under the Copyright Act. Because "parody may quite legitimately aim at garroting the original, destroying it commercially as well as artistically," the role of the courts is to distinguish between '[b]iting criticism [that merely] suppresses demand [and] copyright infringement[, which] usurps it.'"

The fact that your use creates or improves the market for the original work will favor a finding for fair use on this factor. See Nunez, 235 F.3d at 25 (finding fair use when the publication of nude photos actually stirred the controversy that created their market value and there was no evidence that the market existed beforehand).

In summary , although courts will balance all four factors when assessing fair use, the fair use defense is most likely to apply when the infringing use involves criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research. In addition, some general rules of thumb can be helpful in analyzing fair use:

- A use that transforms the original work in some way is more likely to be a fair use;

- A non-profit use is more likely to be considered a fair use than a for-profit use;

- A shorter excerpt is more likely to be a fair use than a long one; and

- A use that cannot act as a replacement for the original work is more likely to be a fair use than one that can serve as a replacement.

Some Special Considerations