Founders Online --> [ Back to normal view ]

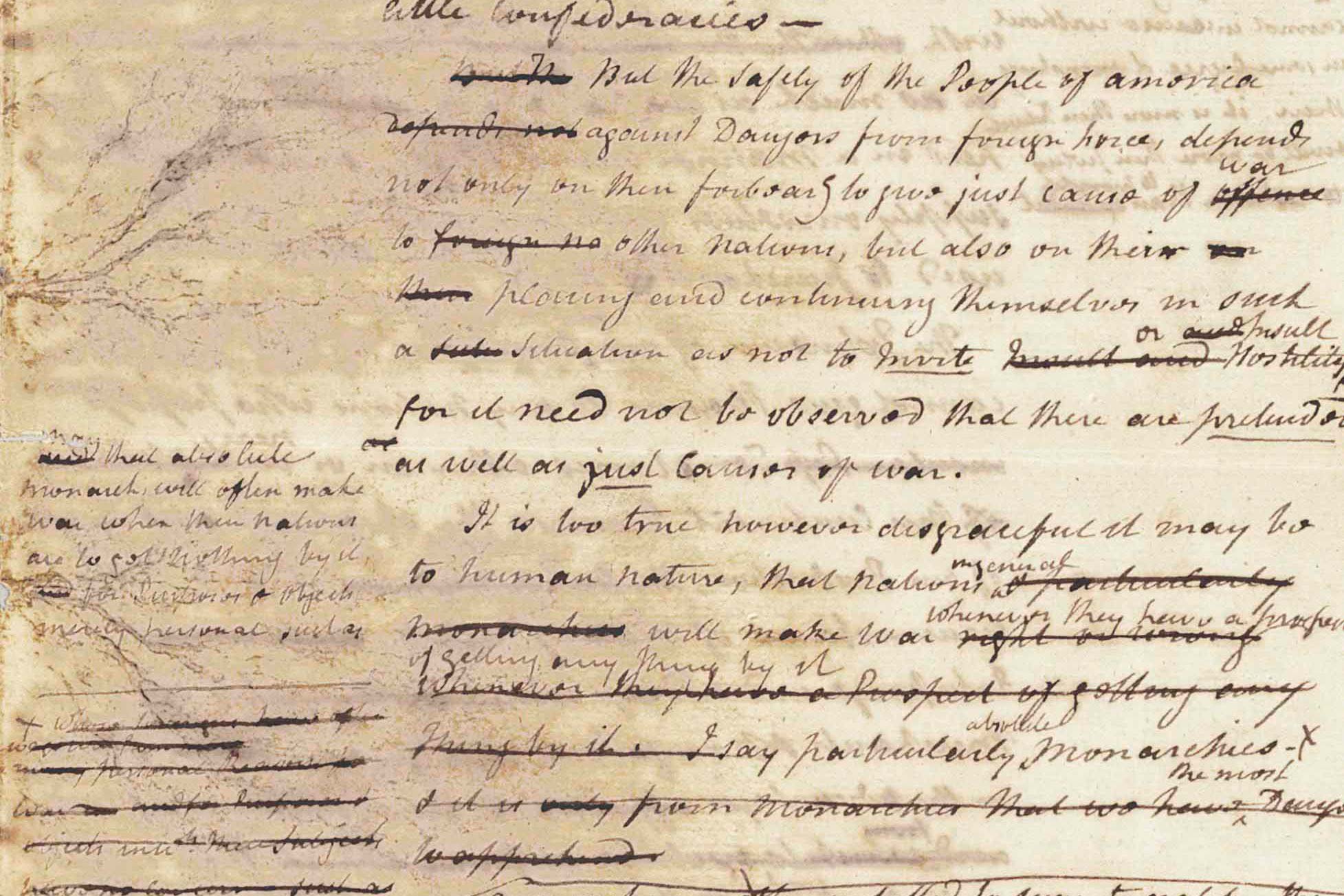

The federalist no. 51, [6 february 1788], the federalist no. 51 1 by james madison or alexander hamilton.

[New York, February 6, 1788]

To the People of the State of New-York.

TO what expedient then shall we finally resort for maintaining in practice the necessary partition of power among the several departments, as laid down in the constitution? The only answer that can be given is, that as all these exterior provisions are found to be inadequate, the defect must be supplied, by so contriving the interior structure of the government, as that its several constituent parts may, by their mutual relations, be the means of keeping each other in their proper places. Without presuming to undertake a full development of this important idea, I will hazard a few general observations, which may perhaps place it in a clearer light, and enable us to form a more correct judgment of the principles and structure of the government planned by the convention.

In order to lay a due foundation for that separate and distinct exercise of the different powers of government, which to a certain extent, is admitted on all hands to be essential to the preservation of liberty, it is evident that each department should have a will of its own; and consequently should be so constituted, that the members of each should have as little agency as possible in the appointment of the members of the others. Were this principle rigorously adhered to, it would require that all the appointments for the supreme executive, legislative, and judiciary magistracies, should be drawn from the same fountain of authority, the people, through channels, having no communication whatever with one another. Perhaps such a plan of constructing the several departments would be less difficult in practice than it may in contemplation appear. Some difficulties however, and some additional expence, would attend the execution of it. Some deviations therefore from the principle must be admitted. In the constitution of the judiciary department in particular, it might be inexpedient to insist rigorously on the principle; first, because peculiar qualifications being essential in the members, the primary consideration ought to be to select that mode of choice, which best secures these qualifications; secondly, because the permanent tenure by which the appointments are held in that department, must soon destroy all sense of dependence on the authority conferring them.

It is equally evident that the members of each department should be as little dependent as possible on those of the others, for the emoluments annexed to their offices. Were the executive magistrate, or the judges, not independent of the legislature in this particular, their independence in every other would be merely nominal.

But the great security against a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department, consists in giving to those who administer each department, the necessary constitutional means, and personal motives, to resist encroachments of the others. The provision for defence must in this, as in all other cases, be made commensurate to the danger of attack. Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place. It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to controul the abuses of government. But what is government itself but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controuls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: You must first enable the government to controul the governed; and in the next place, oblige it to controul itself. A dependence on the people is no doubt the primary controul on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.

This policy of supplying by opposite and rival interests, the defect of better motives, might be traced through the whole system of human affairs, private as well as public. We see it particularly displayed in all the subordinate distributions of power; where the constant aim is to divide and arrange the several offices in such a manner as that each may be a check on the other; that the private interest of every individual, may be a centinel over the public rights. These inventions of prudence cannot be less requisite in the distribution of the supreme powers of the state.

But it is not possible to give to each department an equal power of self defence. In republican government the legislative authority, necessarily, predominates. The remedy for this inconveniency is, to divide the legislature into different branches; and to render them by different modes of election, and different principles of action, as little connected with each other, as the nature of their common functions, and their common dependence on the society, will admit. It may even be necessary to guard against dangerous encroachments by still further precautions. As the weight of the legislative authority requires that it should be thus divided, the weakness of the executive may require, on the other hand, that it should be fortified. An absolute negative, on the legislature, appears at first view to be the natural defence with which the executive magistrate should be armed. But perhaps it would be neither altogether safe, nor alone sufficient. On ordinary occasions, it might not be exerted with the requisite firmness; and on extraordinary occasions, it might be perfidiously abused. May not this defect of an absolute negative be supplied, by some qualified connection between this weaker department, and the weaker branch of the stronger department, by which the latter may be led to support the constitutional rights of the former, without being too much detached from the rights of its own departmen[t]?

If the principles on which these observations are founded be just, as I persuade myself they are, and they be applied as a criterion, to the several state constitutions, and to the federal constitution, it will be found, that if the latter does not perfectly correspond with them, the former are infinitely less able to bear such a test.

There are moreover two considerations particularly applicable to the federal system of America, which place that system 2 in a very interesting point of view.

First. In a single republic, all the power surrendered by the people, is submitted to the administration of a single government; and 3 usurpations are guarded against by a division of the government into distinct and separate departments. In the compound republic of America, the power surrendered by the people, is first divided between two distinct governments, and then the portion allotted to each, subdivided among distinct and separate departments. Hence a double security arises to the rights of the people. The different governments will controul each other; at the same time that each will be controuled by itself.

Second. It is of great importance in a republic, not only to guard the society against the oppression of its rulers; but to guard one part of the society against the injustice of the other part. Different interests necessarily exist in different classes of citizens. If a majority be united by a common interest, the rights of the minority will be insecure. There are but two methods of providing against this evil: The one by creating a will in the community independent of the majority, that is, of the society itself; the other by comprehending in the society so many separate descriptions of citizens, as will render an unjust combination of a majority of the whole, very improbable, if not impracticable. The first method prevails in all governments possessing an hereditary or self appointed authority. This at best is but a precarious security; because a power independent of the society may as well espouse the unjust views of the major, as the rightful interests, of the minor party, and may possibly be turned against both parties. The second method will be exemplified in the federal republic of the United States. Whilst all authority in it will be derived from and dependent on the society, the society itself will be broken into so many parts, interests and classes of citizens, that the rights of individuals or of the minority, will be in little danger from interested combinations of the majority. In a free government, the security for civil rights must be the same as for religious rights. It consists in the one case in the multiplicity of interests, and in the other, in the multiplicity of sects. The degree of security in both cases will depend on the number of interests and sects; and this may be presumed to depend on the extent of country and number of people comprehended under the same government. This view of the subject must particularly recommend a proper federal system to all the sincere and considerate friends of republican government: Since it shews that in exact proportion as the territory of the union may be formed into more circumscribed confederacies or states, oppressive combinations of a majority will be facilitated, the best security under the republican form, for the rights of every class of citizens, will be diminished; and consequently, the stability and independence of some member of the government, the only other security, must be proportionally increased. Justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been, and ever will be pursued, until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit. In a society under the forms of which the stronger faction can readily unite and oppress the weaker, anarchy may as truly be said to reign, as in a state of nature where the weaker individual is not secured against the violence of the stronger: And as in the latter state even the stronger individuals are prompted by the uncertainty of their condition, to submit to a government which may protect the weak as well as themselves: So in the former state, will the more powerful factions or parties 4 be gradually induced by a like motive, to wish for a government which will protect all parties, the weaker as well as the more powerful. It can be little doubted, that if the state of Rhode Island was separated from the confederacy, and left to itself, the insecurity of rights under the popular form of government within such narrow limits, would be displayed by such reiterated oppressions of factious majorities, that some power altogether independent of the people would soon be called for by the voice of the very factions whose misrule had proved the necessity of it. In the extended republic of the United States, and among the great variety of interests, parties and sects which it embraces, a coalition of a majority of the whole society could seldom take place on 5 any other principles than those of justice and the general good; and 6 there being thus less danger to a minor from the will of the major party, there must be less pretext also, to provide for the security of the former, by introducing into the government a will not dependent on the latter; or in other words, a will independent of the society itself. It is no less certain than it is important, notwithstanding the contrary opinions which have been entertained, that the larger the society, provided it lie within a practicable sphere, the more duly capable it will be of self government. And happily for the republican cause , the practicable sphere may be carried to a very great extent, by a judicious modification and mixture of the federal principle .

The [New York] Independent Journal: or, the General Advertiser , February 6, 1788. This essay appeared on February 8 in New-York Packet and on February 11 in The [New York] Daily Advertiser . In the McLean description begins The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, As Agreed upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787. In Two Volumes (New York: Printed and Sold by J. and A. McLean, 1788). description ends edition this essay is numbered 51, in the newspapers it is numbered 50.

1 . For background to this document, see “The Federalist. Introductory Note,” October 27, 1787–May 28, 1788 .

Essay 51, like essay 50, was claimed by H and Madison. The internal evidence presented by Edward G. Bourne (“The Authorship of the Federalist,” The American Historical Review , II [April, 1897], 449–51), strongly indicates Madison’s authorship. Bourne printed in parallel columns sentences from essay 51 which correspond very closely, sometimes exactly, to earlier writings by Madison. For other reasons why Madison’s claim to the authorship of this essay outweighs (but does not necessarily obviate) that of H, see “The Federalist. Introductory Note,” October 27, 1787–May 28, 1788 .

2 . “it” substituted for “that system” in Hopkins description begins The Federalist On The New Constitution. By Publius. Written in 1788. To Which is Added, Pacificus, on The Proclamation of Neutrality. Written in 1793. Likewise, The Federal Constitution, With All the Amendments. Revised and Corrected. In Two Volumes (New York: Printed and Sold by George F. Hopkins, at Washington’s Head, 1802). description ends .

3 . “the” inserted at this point in Hopkins.

4 . “or parties” omitted in Hopkins.

5 . “upon” substituted for “on” in McLean description begins The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, As Agreed upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787. In Two Volumes (New York: Printed and Sold by J. and A. McLean, 1788). description ends and Hopkins.

6 . “Whilst” substituted for “and” in McLean and Hopkins.

Index Entries

You are looking at.

Get Email Updates from Ballotpedia

First Name *

Please complete the Captcha above

Ballotpedia on Facebook

Share this page

Follow Ballotpedia

Ballotpedia on Twitter

Federalist no. 51 by james madison or alexander hamilton (1788).

- Terms and definitions

- Court cases

- Major arguments

- State responses to federal mandates

- State responses to the federal grant review process survey, 2021

- State responses by question to the federal grant review process survey, 2021

- Federalism by the numbers: Federal mandates

- Federalism by the numbers: Federal grants-in-aid

- Federalism by the numbers: Federal information collection requests

- Overview of federal spending during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic

- Index of articles

- 1.1 Alexander Hamilton

- 1.2 James Madison

- 2 Full text of The Structure of the Government Must Furnish the Proper Checks and Balances Between the Different Departments

- 3 Background of the Federalist Papers

- 4 Full list of Federalist Papers

- 6 External links

- 7 Footnotes

Federalist Number (No.) 51 (1788) is an essay by British-American politicians Alexander Hamilton or James Madison arguing for the ratification of the United States Constitution . The full title of the essay is "The Structure of the Government Must Furnish the Proper Checks and Balances Between the Different Departments." It was written as part of a series of essays collected and published in 1788 as The Federalist and later known as The Federalist Papers . These essays were written by Alexander Hamilton , James Madison , and John Jay . They argued for ratification of the United States Constitution as a replacement for the Articles of Confederation . [1]

- Author: Alexander Hamilton or James Madison

- Source: Originally published in the New York Packet on February 8, 1788. Republished in 1788 as part of the collection The Federalist , now referred to as The Federalist Papers .

- Abstract: Hamilton or Madison argue for the separation of powers and address the ways checks and balances can be created within government.

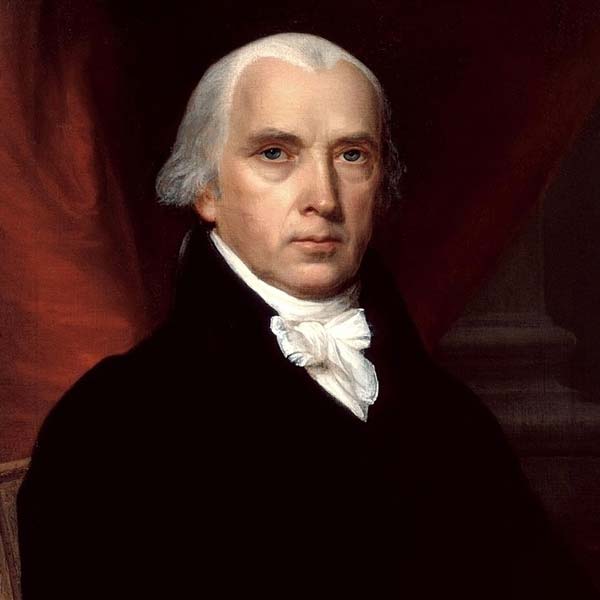

Background of the authors

This paper was written by either Alexander Hamilton or James Madison.

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (c. 1755-1804) was a British-American politician, lawyer, and military officer. He was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1787 and is considered a Founding Father of the United States. Below is a summary of Hamilton's career: [2]

- 1775-1777: Officer in the New York Provincial Artillery Company

- Including service as an adviser to General George Washington

- 1787: Delegate to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, Pa.

- 1787-1788: Author of 51 of the 85 essays in The Federalist Papers

- 1789-1795: First secretary of the treasury of the United States

James Madison

James Madison (1751-1836) was an American politician who served as the fourth president of the United States . He is considered a Founding Father of the United States and is also known as the Father of the Constitution due to his contributions to the development of the United States Constitution . Below is a summary of Madison's career: [3]

- 1775 : Joined the Virginia militia as a colonel

- 1777-1779 : Member of the Virginia Governor's Council

- 1780-1783 : Virginia delegate to the Continental Congress

- 1784-1786 : Member of the Virginia House of Delegates

- 1787 : Virginia representative to the Constitutional Convention

- 1789-1797 : Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia

- 1801-1809 : Fifth U.S. secretary of state

- 1809-1817 : Fourth president of the United States

Full text of The Structure of the Government Must Furnish the Proper Checks and Balances Between the Different Departments

The full text of Federalist No. 51 reads as follows: [1]

Background of the Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers are the 85 articles and essays James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay published arguing for the ratification of the U.S. Constitution and the full replacement of the Aritcles of Confederation. All three writers published their papers under the collective pseudonym Publius between 1787-1788. [5]

The Articles of Confederation were an agreement among the original thirteen states in the United States to unite under a central government consisting of the Continental Congress. The Continental Congress proposed the Articles in 1777, and they became effective in March 1781.

The Articles primarily authorized the national government to govern diplomatic foreign relations and regulate and fund the Continental Army. Under the Articles, the Continental Congress lacked the power to levy taxes and could only request funds from the states. The inability of the national government to raise money caused the government to default on pension payments to former Revolutionary War soldiers and other financial obligations, resulting in unrest. Shay's Rebellion was a prominent example of unrest related to the weakness of the central government and the Continental Congress' inability to fulfill its obligations.

The Constitutional Convention of 1787 was convened to solve the problems related to the weak national government. Federalists, including James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay, advocated for a completely new government under the United States Constitution . They rejected the Articles of Confederation as a weak governing document that needed fully replaced. The federalists thought the strengthened national government could help protect individual rights from factional conflicts at the state and local levels. They argued the Constitution would strengthen the federal government enough to allow for effective governance but not enough to infringe on the rights of individuals. [6] [7] [5]

Anti-federalists like Patrick Henry, Melancton Smith, and George Clinton argued that the national government proposed under the Constitution would be too powerful and would infringe on individual liberties. They thought the Articles of Confederation needed amended, not replaced. [6] [7] [5]

Full list of Federalist Papers

The following is a list of individual essays that were collected and published in 1788 as The Federalist and later known as The Federalist Papers . These essays were written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay. They argued for ratification of the United States Constitution as a replacement for the Articles of Confederation .

- Federalist Papers

- Anti-Federalist papers

External links

- Search Google News for this topic

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Yale Law School , "The Federalist Papers: No. 51," accessed June 15, 2022

- ↑ Biography.com , "Alexander Hamilton," accessed March 6, 2018

- ↑ Biography.com , "James Madison," accessed June 16, 2018

- ↑ Note: This text is quoted verbatim from the original source. Any inconsistencies are attributable to the original source.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 The Federalist Papers , "THE ANTIFEDERALIST PAPERS," accesses May 27, 2022

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Archive , "Federalism," accessed July 27, 2021

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Middle Tennessee State University , "Anti-Federalists," accessed July 27, 2021

- Pages using DynamicPageList3 dplreplace parser function

- Federalism tracking

- The Federalist Papers

Ballotpedia features 457,712 encyclopedic articles written and curated by our professional staff of editors, writers, and researchers. Click here to contact our editorial staff or report an error . For media inquiries, contact us here . Please donate here to support our continued expansion.

Information about voting

- What's on my ballot?

- Where do I vote?

- How do I register to vote?

- How do I request a ballot?

- When do I vote?

- When are polls open?

- Who represents me?

2024 Elections

- Presidential election

- Presidential candidates

- Congressional elections

- Ballot measures

- State executive elections

- State legislative elections

- State judge elections

- Local elections

- School board elections

2025 Elections

- State executives

- State legislatures

- State judges

- Municipal officials

- School boards

- Election legislation tracking

- State trifectas

- State triplexes

- Redistricting

- Pivot counties

- State supreme court partisanship

- Polling indexes

Public Policy

- Administrative state

- Criminal justice policy

- Education policy

- Environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG)

- Unemployment insurance

- Work requirements

- Policy in the states

Information for candidates

- Ballotpedia's Candidate Survey

- How do I run for office?

- How do I update a page?

- Election results

- Send us candidate contact info

Get Engaged

- Donate to Ballotpedia

- Report an error

- Newsletters

- Ballotpedia podcast

- Ballotpedia Boutique

- Media inquiries

- Premium research services

- 2024 Elections calendar

- 2024 Presidential election

- Biden Administration

- Recall elections

- Ballotpedia News

SITE NAVIGATION

- Ballotpedia's Sample Ballot

- 2024 Congressional elections

- 2024 State executive elections

- 2024 State legislative elections

- 2024 State judge elections

- 2024 Local elections

- 2024 Ballot measures

- Upcoming elections

- 2025 Statewide primary dates

- 2025 State executive elections

- 2025 State legislative elections

- 2025 Local elections

- 2025 Ballot measures

- Cabinet officials

- Executive orders and actions

- Key legislation

- Judicial nominations

- White House senior staff

- U.S. President

- U.S. Congress

- U.S. Supreme Court

- Federal courts

- State government

- Municipal government

- Election policy

- Running for office

- Ballotpedia's weekly podcast

- About Ballotpedia

- Editorial independence

- Job opportunities

- News and events

- Privacy policy

- Disclaimers

Federalist 51

“It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices [checks and balances] should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself. A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.

PDF: Federalist Papers No 51

Writing Federalist 51

In this Federalist Paper, James Madison explains and defends the checks and balances system in the Constitution . Each branch of government is framed so that its power checks the power of the other two branches; additionally, each branch of government is dependent on the people, who are the source of legitimate authority.

Madison also discusses the way republican government can serve as a check on the power of factions, and the tyranny of the majority. “[I]n the federal republic of the United States… all authority in it will be derived from and dependent on the society, the society itself will be broken into so many parts, interests, and classes of citizens, that the rights of individuals, or of the minority, will be in little danger from interested combinations of the majority.” All of the Constitution’s checks and balances, Madison concludes, serve to preserve liberty by ensuring justice. Madison explained, “Justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society.”

Madison’s political theory as expressed in this Federalist Paper demonstrated the influence of Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws on the Founders.

Federalist 51 | Primary Source Essentials

Related Resources

James Madison

No other Founder had as much influence in crafting, ratifying, and interpreting the United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights as he did. A skilled political tactician, Madison proved instrumental in determining the form of the early American republic.

Would you have been a Federalist or an Anti-Federalist?

Federalist or Anti-Federalist? Over the next few months we will explore through a series of eLessons the debate over ratification of the United States Constitution as discussed in the Federalist and Anti-Federalist papers. We look forward to exploring this important debate with you! One of the great debates in American history was over the ratification […]

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Historyplex

Summary and Analysis of James Madison’s Federalist No. 51

Federalist No. 51 advocates the balance of power in the US government by the principle of 'checks and balances'. For better understanding, this Historyplex post gives you the summary of Federalist No. 51, as well as the analysis of its main points.

Federalist No. 51 advocates the balance of power in the US government by the principle of ‘checks and balances’. For better understanding, this Historyplex post gives you the summary of Federalist No. 51, as well as the analysis of its main points.

Did You Know?

The identity of the authors of the Federalist Papers was kept a secret. James Madison published his essays using the name ‘Publius’.

Federalist No. 51 was an essay published by American politician and statesman, James Madison, on February 6, 1788. It was the fifty-first paper in a series of 85 articles that are collectively known as the Federalist Papers. These articles were aimed at modifying public opinion in favor of ratifying the new US Constitution.

These papers had several authors besides Madison, like Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, who were all federalists, giving the essays their name. Despite the contributions of these authors, James Madison alone was given the most credit for publishing these papers. His fame increased after he became President, and was later given the title of ‘Father of the American Constitution.’ On the other hand, a group of people called the anti-federalists campaigned against the new constitution, believing that it would lead to a corrupt government. Finally, the federalists won, and the new constitution was ratified on June 21, 1788.

Federalist No. 51 tries to explain how the new constitution will prevent departments of the government from intruding into each others’ domains, besides giving citizens the power to prevent their elected representatives from abusing their powers. It believes in the system of ‘checks and balances’, in which the government is divided into different departments which have conflicting powers that balance out each other. What is really interesting in this essay is the detailed analysis of various institutions, which is known today as ‘the theory of institutional design.’ Federalist No. 51 also gives an explanation about how the rights of minorities will be protected by the constitution. Here are the main points of this essay.

Summary of Federalist No. 51

In the essay, James Madison says that there is a need to partition power amongst the various departments of the government as the US Constitution mandates. This has to be done by creating a government that establishes such mutual relations between its departments, which prevents one from interfering in the affairs of the other.

Madison further adds that without going into intricate details, he will try to point out what is the ideal division of power that the constitution envisioned. He says that the independence of the departments is only possible if members of each department have as little control as possible over the appointment and tenure of the members of other departments. This would probably mean that the members of all the three branches of the US Government―the legislative, the executive, and the judiciary―should be elected by the citizens. However, there has to be some deviation to this rule in case of the judiciary, since the judges need to have certain educational and moral standards that the common public may not understand. Besides, the judges hold tenure for life, which makes it difficult for other departments to control them.

The remuneration offered to the members of one department must also not be controlled by any other department. To prevent encroachment of one department on another, certain constitutional powers should be provided. The ambitions of members should be in sync with the independence of their departments, as is required by the constitution. Madison also points out that the need to make departments independent from each other is because of man’s nature to usurp others’ powers. The principle of creating divisions and subdivisions to keep each other in check is present in all endeavors, both public and private.

Madison further adds that a perfectly equal division of power is against the Republican nature of the US Government, since the legislature has to be the most powerful arm of the government, according to this system. However, any misuse can be checked by dividing the legislature into various branches; the members of which are elected by different channels, thus making them independent. The executive wing of the government has to be strengthened to counteract the effects of the strong legislature, but giving it absolute power to completely annul the decisions of the legislative may be counterproductive. This power may either not be imposed firmly or it may be abused to cripple the legislative.

After giving these observations, Madison points out a few interesting things about the Federal nature of the American Government. This system divides the government into two parts; each is then divided and subdivided further into various departments that keep a check on each others’ excesses. This provides a ‘double security’ to the citizens. Further, society has to be handled in such a way that its major faction does not stifle the rights of the minority. This can be done either by creating a powerful, authoritarian government which cannot be dissuaded by the majority, or by dividing the society itself into so many different classes that any single group cannot impose its own views. The later method is granted to the US Government by its constitution.

Madison says that the security of citizens will depend on the diversity of sects and interests throughout the country. A federal republic is in the interests of the citizens, since a country which consists of many states and confederacies will lead to oppression by the majority in each, and the laws of the republic grant enhanced powers and independence to a certain department or member to counteract against this oppression. He further adds that the main aim of any government is to establish justice, where both the weaker and stronger sects of society are protected and there is no oppression. In a state where members of the majority rule and oppress the minority sects, there is a tendency to tilt the balance in favor of a power independent of either the majority or the minority.

The federal nature of the American Government guarantees that it possesses the will to deliver justice, irrespective of the power of the strong or weak sections of society. A country of many large groups will benefit by self-governance, and despite being too large to follow a federal plan, this plan can be modified to make it both possible and practical for the United States.

☞ A department in the government may try to influence the working of another by controlling appointments, tenure, or emoluments of its members.

☞ The majority class in the society may hold sway over the government, using it to oppress the weak or minority classes of society.

☞ Giving increased powers to any one department to prevent other departments from becoming excessively powerful may backfire, as this power may be misused or used less firmly.

Solutions Given by Federalist No. 51

➤ The structure of the government should be designed in such a way that departments have their own powers, and are independent from encroachment by others.

➤ The personal interest of every member should lie in keeping members of other departments out of their way. In Madison’s own words, “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition”.

➤ Different departments should have contrasting powers and responsibilities to keep each in its place. For example, the US President, as the head of the executive, has the power to prevent the legislature from becoming too powerful. But if the president is found guilty of misdemeanor, i.e., he misuses his powers, he can be impeached. Thus, the legislature and executive can keep each other in check.

➤ The members of departments of the government can be elected by the citizens. Thus, the greatest control on the departments is in the hands of the people themselves, who can remove any representative who abuses his powers.

➤ The members of the judiciary, such as judges of the Supreme Court, are to be appointed by the executive, rather than the public, keeping in mind their moral and educational qualifications. These members keep the legislative and judiciary in their proper place, as they solve disputes regarding distribution of power between the two departments. Members of the judiciary also cannot be impeached by the other two branches. However, the constitution has placed controls on the judiciary, by stating that their judgments are not binding on the members of either, the legislative or the executive. It has also not given control of finances in the judiciary’s hands, which is under the control of the legislative.

➤ Checks have been placed on the executive and the legislative to prevent them from ignoring the judiciary’s interpretation of the constitutional laws. The main control is again, the people, as by ignoring the constitution, the members of the government risk insulting the people’s respect for their constitution.

➤ The legislative is prevented from becoming too powerful, by dividing it into two parts, and then subdividing each part into various subdivisions. The members of each are elected by the public via separate channels, keeping them independent from each other. Their contrasting powers also help keep each other in check.

➤ The influence of the majority faction in society can be curtailed by subdividing it into various factions, each with different aspirations. This way, any single faction is kept away from power.

➤ In a country of many states or confederacies, the members of the majority faction tend to be empowered. To keep this at bay, the powers of a specific member of the government can be increased proportionally, so as to impose a system of checks and balances.

Federalist No. 51 is one of the most popular federalist papers, because it tries to give more power to ordinary citizens, and upholds the principles of liberty and justice, which are applicable even today.

Like it? Share it!

Get Updates Right to Your Inbox

Further insights.

Privacy Overview

- Avalon Statement of Purpose

- Accessibility at Yale

- Yale Law Library

- University Library

- Yale Law School

- Search Morris

- Search Orbis

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Federalist Papers

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 22, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The Federalist Papers are a collection of essays written in the 1780s in support of the proposed U.S. Constitution and the strong federal government it advocated. In October 1787, the first in a series of 85 essays arguing for ratification of the Constitution appeared in the Independent Journal , under the pseudonym “Publius.” Addressed to “The People of the State of New York,” the essays were actually written by the statesmen Alexander Hamilton , James Madison and John Jay . They would be published serially from 1787-88 in several New York newspapers. The first 77 essays, including Madison’s famous Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 , appeared in book form in 1788. Titled The Federalist , it has been hailed as one of the most important political documents in U.S. history.

Articles of Confederation

As the first written constitution of the newly independent United States, the Articles of Confederation nominally granted Congress the power to conduct foreign policy, maintain armed forces and coin money.

But in practice, this centralized government body had little authority over the individual states, including no power to levy taxes or regulate commerce, which hampered the new nation’s ability to pay its outstanding debts from the Revolutionary War .

In May 1787, 55 delegates gathered in Philadelphia to address the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation and the problems that had arisen from this weakened central government.

A New Constitution

The document that emerged from the Constitutional Convention went far beyond amending the Articles, however. Instead, it established an entirely new system, including a robust central government divided into legislative , executive and judicial branches.

As soon as 39 delegates signed the proposed Constitution in September 1787, the document went to the states for ratification, igniting a furious debate between “Federalists,” who favored ratification of the Constitution as written, and “Antifederalists,” who opposed the Constitution and resisted giving stronger powers to the national government.

The Rise of Publius

In New York, opposition to the Constitution was particularly strong, and ratification was seen as particularly important. Immediately after the document was adopted, Antifederalists began publishing articles in the press criticizing it.

They argued that the document gave Congress excessive powers and that it could lead to the American people losing the hard-won liberties they had fought for and won in the Revolution.

In response to such critiques, the New York lawyer and statesman Alexander Hamilton, who had served as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, decided to write a comprehensive series of essays defending the Constitution, and promoting its ratification.

Who Wrote the Federalist Papers?

As a collaborator, Hamilton recruited his fellow New Yorker John Jay, who had helped negotiate the treaty ending the war with Britain and served as secretary of foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation. The two later enlisted the help of James Madison, another delegate to the Constitutional Convention who was in New York at the time serving in the Confederation Congress.

To avoid opening himself and Madison to charges of betraying the Convention’s confidentiality, Hamilton chose the pen name “Publius,” after a general who had helped found the Roman Republic. He wrote the first essay, which appeared in the Independent Journal, on October 27, 1787.

In it, Hamilton argued that the debate facing the nation was not only over ratification of the proposed Constitution, but over the question of “whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.”

After writing the next four essays on the failures of the Articles of Confederation in the realm of foreign affairs, Jay had to drop out of the project due to an attack of rheumatism; he would write only one more essay in the series. Madison wrote a total of 29 essays, while Hamilton wrote a staggering 51.

Federalist Papers Summary

In the Federalist Papers, Hamilton, Jay and Madison argued that the decentralization of power that existed under the Articles of Confederation prevented the new nation from becoming strong enough to compete on the world stage or to quell internal insurrections such as Shays’s Rebellion .

In addition to laying out the many ways in which they believed the Articles of Confederation didn’t work, Hamilton, Jay and Madison used the Federalist essays to explain key provisions of the proposed Constitution, as well as the nature of the republican form of government.

'Federalist 10'

In Federalist 10 , which became the most influential of all the essays, Madison argued against the French political philosopher Montesquieu ’s assertion that true democracy—including Montesquieu’s concept of the separation of powers—was feasible only for small states.

A larger republic, Madison suggested, could more easily balance the competing interests of the different factions or groups (or political parties ) within it. “Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests,” he wrote. “[Y]ou make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens[.]”

After emphasizing the central government’s weakness in law enforcement under the Articles of Confederation in Federalist 21-22 , Hamilton dove into a comprehensive defense of the proposed Constitution in the next 14 essays, devoting seven of them to the importance of the government’s power of taxation.

Madison followed with 20 essays devoted to the structure of the new government, including the need for checks and balances between the different powers.

'Federalist 51'

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” Madison wrote memorably in Federalist 51 . “If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

After Jay contributed one more essay on the powers of the Senate , Hamilton concluded the Federalist essays with 21 installments exploring the powers held by the three branches of government—legislative, executive and judiciary.

Impact of the Federalist Papers

Despite their outsized influence in the years to come, and their importance today as touchstones for understanding the Constitution and the founding principles of the U.S. government, the essays published as The Federalist in 1788 saw limited circulation outside of New York at the time they were written. They also fell short of convincing many New York voters, who sent far more Antifederalists than Federalists to the state ratification convention.

Still, in July 1788, a slim majority of New York delegates voted in favor of the Constitution, on the condition that amendments would be added securing certain additional rights. Though Hamilton had opposed this (writing in Federalist 84 that such a bill was unnecessary and could even be harmful) Madison himself would draft the Bill of Rights in 1789, while serving as a representative in the nation’s first Congress.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Ron Chernow, Hamilton (Penguin, 2004). Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (Simon & Schuster, 2010). “If Men Were Angels: Teaching the Constitution with the Federalist Papers.” Constitutional Rights Foundation . Dan T. Coenen, “Fifteen Curious Facts About the Federalist Papers.” University of Georgia School of Law , April 1, 2007.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Suggestions

- A Streetcar Named Desire

- Death of a Salesman

- Pride and Prejudice

- Romeo and Juliet

Please wait while we process your payment

Reset Password

Your password reset email should arrive shortly..

If you don't see it, please check your spam folder. Sometimes it can end up there.

Something went wrong

Log in or create account.

- Be between 8-15 characters.

- Contain at least one capital letter.

- Contain at least one number.

- Be different from your email address.

By signing up you agree to our terms and privacy policy .

Don’t have an account? Subscribe now

Create Your Account

Sign up for your FREE 7-day trial

- Ad-free experience

- Note-taking

- Flashcards & Quizzes

- AP® English Test Prep

- Plus much more

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Already have an account? Log in

Choose Your Plan

Group Discount

$4.99 /month + tax

$24.99 /year + tax

Save over 50% with a SparkNotes PLUS Annual Plan!

Purchasing SparkNotes PLUS for a group?

Get Annual Plans at a discount when you buy 2 or more!

$24.99 $18.74 / subscription + tax

Subtotal $37.48 + tax

Save 25% on 2-49 accounts

Save 30% on 50-99 accounts

Want 100 or more? Contact us for a customized plan.

Payment Details

Payment Summary

SparkNotes Plus

Change

You'll be billed after your free trial ends.

7-Day Free Trial

Not Applicable

Renews April 24, 2024 April 17, 2024

Discounts (applied to next billing)

SNPLUSROCKS20 | 20% Discount

This is not a valid promo code.

Discount Code (one code per order)

SparkNotes PLUS Annual Plan - Group Discount

SparkNotes Plus subscription is $4.99/month or $24.99/year as selected above. The free trial period is the first 7 days of your subscription. TO CANCEL YOUR SUBSCRIPTION AND AVOID BEING CHARGED, YOU MUST CANCEL BEFORE THE END OF THE FREE TRIAL PERIOD. You may cancel your subscription on your Subscription and Billing page or contact Customer Support at [email protected] . Your subscription will continue automatically once the free trial period is over. Free trial is available to new customers only.

For the next 7 days, you'll have access to awesome PLUS stuff like AP English test prep, No Fear Shakespeare translations and audio, a note-taking tool, personalized dashboard, & much more!

You’ve successfully purchased a group discount. Your group members can use the joining link below to redeem their group membership. You'll also receive an email with the link.

Members will be prompted to log in or create an account to redeem their group membership.

Thanks for creating a SparkNotes account! Continue to start your free trial.

We're sorry, we could not create your account. SparkNotes PLUS is not available in your country. See what countries we’re in.

There was an error creating your account. Please check your payment details and try again.

Your PLUS subscription has expired

- We’d love to have you back! Renew your subscription to regain access to all of our exclusive, ad-free study tools.

- Renew your subscription to regain access to all of our exclusive, ad-free study tools.

- Go ad-free AND get instant access to grade-boosting study tools!

- Start the school year strong with SparkNotes PLUS!

- Start the school year strong with PLUS!

The Federalist Papers (1787-1789)

The founding fathers.

- Study Guide

Unlock your FREE SparkNotes PLUS trial!

Unlock your free trial.

- Ad-Free experience

- Easy-to-access study notes

- AP® English test prep

Federalist Essays No.47 - No. 51

One of the biggest criticisms of the newly proposed plan of government is that it violates the political belief that the legislative, executive and judicial and judicial branches should be separate and distinct. That there is too much mixing of powers in the U.S. Constitution and this threatens to progress to single body holding all the powers and trampling on the rights of the individuals.

The great authority on the division of powers is Montesquieu who held the highest regard for the British Constitution in which the branches had many interconnections. The threat, as articulated by Montesquieu, exists when the whole power of one branch is exercised by the same body that exercises the whole power of another branch. This did not occur in the British Constitution and has not been placed into the U.S. Constitution.

Each of the state constitutions as well, establishes a division of power that is not totally distinct and separate. There is not a single instance in which each branch has been kept totally separate. New Hampshire's constitution supports the idea that too much mixture is not good, but that some mixture is necessary. Therefore, the separation of powers described by the U.S. Constitution does not violate the principle of free government as it has ever been understood in America.

However, in a government of mixed powers, it is essential that each branch have a degree of control over the others. Most American constitutions have thought it enough protection to simply divide the duties amongst the different branches, but the experience of both Virginia and Pennsylvania provide evidence that dividing duties between branches does not protect each branch from the power of the others. The written demarcation of powers is not enough to prevent the concentration of powers in the hands of one body.

Some have argued that the people should be the final judge when one branch attempts to usurp the power of another, but there are many reasons why this would be dangerous to the government itself. Every appeal to the people to right the wrongs of government implies a defect in that government and reduces the respect the people give to that government. There is great danger in disturbing the public peace by frequently appealing to the public opinion. Finally, an appeal to the people would probably not adjust the imbalance that occurred in the first place.

In a representative republic, the most powerful branch is the legislative. The branches most likely to appeal to the people for usurpation of their powers would therefore be the executive or the judicial. The supporters of the executive and judicial branches be outnumbered by the supporters of the legislative branch, which is by its nature closer in proximity and affections with the people. Theoretically, the legislative branch represents the people's opinions. It is like asking the legislative branch to decide whether the legislative branch has usurped too much power.

Popular pages: The Federalist Papers (1787-1789)

Review quiz further study, take a study break.

Every Literary Reference Found in Taylor Swift's Lyrics

The 7 Most Messed-Up Short Stories We All Had to Read in School

QUIZ: Which Greek God Are You?

Answer These 7 Questions and We'll Tell You How You'll Do on Your AP Exams

The Federalist Papers

What is the thesis of federalist 51.

i dont the answer

This Federalist Paper, written by James Madison focuses on the need for checks and balances in government while reminding people in government that separation of powers is critical to balance any one person or branch whose ambition is overwhelming against someone who is also overly ambitious.

Actually the exact thesis is stated in the essay itself. It is as follows: "without presuming to undertake a full development of this important idea, I will hazard a few general observations which may perhaps place it in a clearer light, and enable us to form a more correct judgment of the principles les and structure of government planned by the convention".

Log In To Your GradeSaver Account

- Remember me

- Forgot your password?

Create Your GradeSaver Account

Commentary on Federalist 51

This is the last of fifteen essays written by Madison on “the great difficulty” of founding. There are ten paragraphs in the essay.

1. The way to implement the theory of separation of powers in practice is to so contrive “the interior structure of the government as that its several constituent parts may, by their mutual relations, be the means of keeping each other in their proper places.”

2. Accordingly, “each department should have a will of its own; and consequently should be so constituted that the members of each should have as little agency as possible in the appointment of the members of the others.”

3. “It is equally evident that the members of each department should be as little dependent as possible on those of the others for the emoluments annexed to their offices.”

4. A: “The great security against a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department consists in giving to those who administer each department the necessary constitutional means and personal motives to resist encroachments of the others… Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interests of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place.”

B: Isn’t relying on ambition and interest, “a reflection on human nature?” But, adds Madison, what is government itself but the greatest reflection on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary.”

C: “The Great Difficulty” of Founding: You must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself. A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government, but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.”

5. “This policy of supplying, by opposite and rival interests, the defect of better motives, might be traced through the whole system of human affairs, private as well as public.” Madison calls this policy “inventions of prudence.”

6. “In republican government, the legislative authority necessarily predominates.” Thus, it is “not possible to give to each department an equal power of self-defense.” Accordingly, we need to add here and subtract there. We can divide the legislature into two branches and fortify the executive a) with the power of a conditional veto and b) “some qualified connection” with the Senate.

7. The general government comes closer to passing the “self-defense” of each branch test than do the State governments.

8. “There are, moreover, two considerations particularly applicable to the federal system of America, which place that system in a very interesting point of view.”

9. First, America is a “compound republic,” rather than a “single republic.” This provides for a “double security… to the rights of the people. The different governments will control each other, at the same time that each will be controlled by itself.”

10. Second, there are only two ways to combat “the evil” of majority faction, a) “by creating a will in the community independent of the majority,” or b) creating an authoritative source “dependent on the society,” but, and here is the essence of the American experiment, the society “will be broken down into so many parts,” that it contain a vast number and variety of interests. To repeat, the American society will “be broken down into so many parts, interests and classes of citizens, that the rights of individuals, or the minority, will be in little danger from interested combinations of the majority.” Echoing Federalist 10, Madison says “the security for civil rights must be the same as that for religious rights. It consists in the one case in the multiplicity of interests, and in the other in the multiplicity of sects.” And both depend on “the extended republic.” Let us not forget, adds Madison, that “justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been and ever will be pursued until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit.” Fortunately, in “the extended republic… a coalition of a majority of the whole society could seldom take place on any other principles than those of justice and the general good.” We have rejected the “precarious security” provided by the “hereditary or self-appointed” alternative of “introducing into the government… a will independent of the society itself.”

Receive resources and noteworthy updates.

The American Founding

Federalist No. 51

February 6, 1788

INTRODUCTION

A number of Convention delegates who declined to sign the Constitution had voiced concerns that either the legislative or executive branch of the federal government would usurp the authority of the other. Their objections were now being voiced by Antifederalist writers. Publius (who in this essay is Madison) responds here to their concerns. It is in fact possible to contrive “the interior structure of the government as that its several constituent parts may, by their mutual relations, be the means of keeping each other in their proper places.” To avoid “a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department,” one must give “to those who administer each department the necessary constitutional means and personal motives to resist encroachments of the others. . . . Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interests of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place.” To provide those means and motives, one must assign each department of government distinct and competing powers and responsibilities, while taking care that the members of one branch not appoint the members of another or specify the salaries of another, except in certain specific cases.

These precautions may not be enough. Although in Federalist 10 Publius expressed a hope that the elected representatives of the people, being drawn from a large pool of candidates in so populous a republic, might be those most motivated by public interest, now Publius admits that ambition might corrupt even the best men. Such is human nature; and “What is government itself but the greatest reflection on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary.”

The right of the people to elect and recall their representatives will not in itself guarantee proper behavior of those in authority; “experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.” Hence one must empower each branch of government to defend itself against the encroachments of others. In a republic, the legislative branch, as most connected to the will of the people, necessarily dominates. Yet one can divide the legislative power into two branches that are constituted in different ways and thus responsible to different groupings of citizens. One can also grant veto power to the executive, while prudently refraining from making the executive veto final and absolute.

Closing his essay, Publius reiterates the argument of Federalist 10 , reminding the reader first, that America is a “compound republic,” rather than a “single republic”: it is a federation of states, each of which are governed through individual systems of balanced powers. Second, American society will “be broken down into so many parts, interests and classes of citizens, that the rights of individuals, or the minority, will be in little danger from interested combinations of the majority.” Justice is always the aim of popular government, Publius asserts, pointing out that even factious parties call for an arbitrator as soon as they feel an injustice is done to themselves. We need not seek in vain for some disinterested authority, aloof from society, to judge between competing interests. Correct judgment will arise from within society, since reasonable persons with widely varying private interests will agree only on those measures tending toward “justice and the general good.”

To what expedient then shall we finally resort, for maintaining in practice the necessary partition of power among the several departments, as laid down in the constitution? The only answer that can be given is, that as all these exterior provisions are found to be inadequate, the defect must be supplied, by so contriving the interior structure of the government, as that its several constituent parts may, by their mutual relations, be the means of keeping each other in their proper places. Without presuming to undertake a full development of this important idea, I will hazard a few general observations, which may perhaps place it in a clearer light, and enable us to form a more correct judgment of the principles and structure of the government planned by the convention.

In order to lay a due foundation for that separate and distinct exercise of the different powers of government, which, to a certain extent, is admitted on all hands to be essential to the preservation of liberty, it is evident that each department should have a will of its own; and consequently should be so constituted, that the members of each should have as little agency as possible in the appointment of the members of the others. Were this principle rigorously adhered to, it would require that all the appointments for the supreme executive, legislative, and judiciary magistracies, should be drawn from the same fountain of authority, the people, through channels having no communication whatever with one another. Perhaps such a plan of constructing the several departments, would be less difficult in practice, than it may in contemplation appear. Some difficulties, however, and some additional expense, would attend the execution of it. Some deviations, therefore, from the principle must be admitted. In the constitution of the judiciary department in particular, it might be inexpedient to insist rigorously on the principle; first, because peculiar qualifications being essential in the members, the primary consideration ought to be to select that mode of choice which best secures these qualifications; secondly, because the permanent tenure by which the appointments are held in that department, must soon destroy all sense of dependence on the authority conferring them.

It is equally evident, that the members of each department should be as little dependent as possible on those of the others, for the emoluments annexed to their offices. Were the executive magistrate, or the judges, not independent of the legislature in this particular, their independence in every other, would be merely nominal.

But the great security against a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department, consists in giving to those who administer each department, the necessary constitutional means, and personal motives, to resist encroachments of the others. The provision for defense must in this, as in all other cases, be made commensurate to the danger of attack. Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man, must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place. It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself. A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.

This policy of supplying, by opposite and rival interests, the defect of better motives, might be traced through the whole system of human affairs, private as well as public. We see it particularly displayed in all the subordinate distributions of power; where the constant aim is, to divide and arrange the several offices in such a manner as that each may be a check on the other; that the private interest of every individual may be a sentinel over the public rights. These inventions of prudence cannot be less requisite in the distribution of the supreme powers of the state.

But it is not possible to give to each department an equal power of self-defense. In republican government, the legislative authority necessarily predominates. The remedy for this inconveniency is, to divide the legislature into different branches; and to render them, by different modes of election, and different principles of action, as little connected with each other, as the nature of their common functions, and their common dependence on the society, will admit. It may even be necessary to guard against dangerous encroachments by still further precautions. As the weight of the legislative authority requires that it should be thus divided, the weakness of the executive may require, on the other hand, that it should be fortified. An absolute negative [1] on the legislature, appears, at first view, to be the natural defense with which the executive magistrate should be armed. But perhaps it would be neither altogether safe, nor alone sufficient. On ordinary occasions, it might not be exerted with the requisite firmness; and on extraordinary occasions, it might be perfidiously abused. May not this defect of an absolute negative be supplied by some qualified connection between this weaker department, and the weaker branch of the stronger department, by which the latter may be led to support the constitutional rights of the former, without being too much detached from the rights of its own department?

If the principles on which these observations are founded be just, as I persuade myself they are, and they be applied as a criterion to the several state constitutions, and to the federal constitution, it will be found, that if the latter does not perfectly correspond with them, the former are infinitely less able to bear such a test.

There are moreover two considerations particularly applicable to the federal system of America, which place that system in a very interesting point of view.

First. In a single republic, all the power surrendered by the people, is submitted to the administration of a single government; and the usurpations are guarded against, by a division of the government into distinct and separate departments. In the compound republic of America, the power surrendered by the people, is first divided between two distinct governments, and then the portion allotted to each subdivided among distinct and separate departments. Hence a double security arises to the rights of the people. The different governments will control each other; at the same time that each will be controlled by itself.

Second. It is of great importance in a republic, not only to guard the society against the oppression of its rulers; but to guard one part of the society against the injustice of the other part. Different interests necessarily exist in different classes of citizens. If a majority be united by a common interest, the rights of the minority will be insecure. There are but two methods of providing against this evil: the one, by creating a will in the community independent of the majority, that is, of the society itself; the other, by comprehending in the society so many separate descriptions of citizens, as will render an unjust combination of a majority of the whole very improbable, if not impracticable. The first method prevails in all governments possessing an hereditary or self-appointed authority. This, at best, is but a precarious security; because a power independent of the society may as well espouse the unjust views of the major, as the rightful interests of the minor party, and may possibly be turned against both parties. The second method will be exemplified in the federal republic of the United States. Whilst all authority in it will be derived from, and dependent on the society, the society itself will be broken into so many parts, interests, and classes of citizens, that the rights of individuals, or of the minority, will be in little danger from interested combinations of the majority. In a free government, the security for civil rights must be the same as that for religious rights. It consists in the one case in the multiplicity of interests, and in the other, in the multiplicity of sects. The degree of security in both cases will depend on the number of interests and sects; and this may be presumed to depend on the extent of country and number of people comprehended under the same government.

This view of the subject must particularly recommend a proper federal system to all the sincere and considerate friends of republican government: since it shows, that in exact proportion as the territory of the union may be formed into more circumscribed confederacies, or states, oppressive combinations of a majority will be facilitated; the best security under the republican form, for the rights of every class of citizens, will be diminished; and consequently, the stability and independence of some member of the government, the only other security, must be proportionally increased. Justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been, and ever will be, pursued, until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit. In a society, under the forms of which the stronger faction can readily unite and oppress the weaker, anarchy may as truly be said to reign, as in a state of nature, where the weaker individual is not secured against the violence of the stronger: and as, in the latter state, even the stronger individuals are prompted, by the uncertainty of their condition, to submit to a government which may protect the weak, as well as themselves: so, in the former state, will the more powerful factions or parties be gradually induced, by a like motive, to wish for a government which will protect all parties, the weaker as well as the more powerful. It can be little doubted, that if the state of Rhode Island was separated from the confederacy, and left to itself, the insecurity of rights under the popular form of government within such narrow limits, would be displayed by such reiterated oppressions of factious majorities, that some power altogether independent of the people, would soon be called for by the voice of the very factions whose misrule had proved the necessity of it. In the extended republic of the United States, and among the great variety of interests, parties, and sects, which it embraces, a coalition of a majority of the whole society could seldom take place upon any other principles, than those of justice and the general good: whilst there being thus less danger to a minor from the will of the major party, there must be less pretext also, to provide for the security of the former, by introducing into the government a will not dependent on the latter: or, in other words, a will independent of the society itself. It is no less certain than it is important, notwithstanding the contrary opinions which have been entertained, that the larger the society, provided it lie within a practicable sphere, the more duly capable it will be of self-government. And happily for the republican cause, the practicable sphere may be carried to a very great extent, by a judicious modification and mixture of the federal principle.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

In the McLean description begins The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, As Agreed upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787. In Two Volumes (New York: Printed and Sold by J. and A. McLean, 1788). description ends edition this essay is numbered 51, in the newspapers it is numbered 50. 1 .

The Federalist Papers were written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay working together. The Anti-Federalist Papers weren't as organized and instead collected together and even named "The Anti-Federalist Papers" by historians much later in the 20th century. We still don't know who wrote which papers with much certainty.

On February 8, 1788, James Madison published Federalist 51—titled "The Structure of the Government Must Furnish the Proper Checks and Balances Between the Different Departments."In this famous Federalist Paper essay, Madison explained how the Constitution's structure checked the powers of the elected branches and protected against possible abuses by the national government.

Federalist No. 51, titled: "The Structure of the Government Must Furnish the Proper Checks and Balances Between the Different Departments", is an essay by James Madison, the fifty-first of The Federalist Papers.This document was first published by The New York Packet on February 8, 1788, under the pseudonym Publius, the name under which all The Federalist papers were published.

On February 8, 1788, James Madison published Federalist No. 51—titled "The Structure of the Government Must Furnish the Proper Checks and Balances Between the Different Departments.". In this famous Federalist Paper essay, Madison explained how the Constitution's structure checked the powers of the elected branches and protected against ...

The Federalist Papers were a series of essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the pen name "Publius." ... Federalist No. 51. The Structure of the Government Must Furnish the Proper Checks and Balances Between the Different Departments. From the New York Packet Friday, February 8, 1788.

Background of the Federalist Papers. The Federalist Papers are the 85 articles and essays James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay published arguing for the ratification of the U.S. Constitution and the full replacement of the Aritcles of Confederation. All three writers published their papers under the collective pseudonym Publius between 1787-1788.

Federalist #51 is the last of 15 essays written by Madison on "the great difficulty" of founding. There are 10 paragraphs in the essay. The way to implement the theory of separation of powers in practice is to so contrive "the interior structure of the government as that its several constituent parts may, by their mutual relations, be the ...

Writing Federalist 51. In this Federalist Paper, James Madison explains and defends the checks and balances system in the Constitution. Each branch of government is framed so that its power checks the power of the other two branches; additionally, each branch of government is dependent on the people, who are the source of legitimate authority.

In Federalist 51, Publius (James Madison) argues that the separation of powers described in the Constitution will not survive "in practice" unless the structure of government is so contrived that the human beings who occupy each branch of the government have the "constitutional means and personal motives" to resist "encroachments" from the other branches.

Federalist No. 51 was an essay published by American politician and statesman, James Madison, on February 6, 1788. It was the fifty-first paper in a series of 85 articles that are collectively known as the Federalist Papers. These articles were aimed at modifying public opinion in favor of ratifying the new US Constitution.

The Federalist Papers essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of The Federalist Papers by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and James Madison. A Close Reading of James Madison's The Federalist No. 51 and its Relevancy Within the Sphere of Modern Political Thought

Source: Alexander Hamilton or James Madison, "Federalist No. 51," The Federalist: A Collection of Essays, Written in Favour of the New Constitution, as Agreed Upon by the Federal Convention, September 17, 1787, Vol. 2 (New York: J. & A. McLean, 1788), pp. 116-122, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, GLC01551

The Federalist Papers : No. 51. From the New York Packet. Friday, February 8, 1788. To the People of the State of New York: TO WHAT expedient, then, shall we finally resort, for maintaining in practice the necessary partition of power among the several departments, as laid down in the Constitution? The only answer that can be given is, that as ...

The first 77 essays, including Madison's famous Federalist 10 and Federalist 51, appeared in book form in 1788. Titled The Federalist , it has been hailed as one of the most important political ...