Our content is reader-supported. Things you buy through links on our site may earn us a commission

Join our newsletter

Never miss out on well-researched articles in your field of interest with our weekly newsletter.

- Project Management

- Starting a business

Get the latest Business News

Mastering communication: paraphrasing and summarizing skills.

Two very useful skills in communicating with others, including when coaching and facilitating, are paraphrasing and summarizing the thoughts of others.

How to Paraphrase When Communicating and Coaching With Others

Paraphrasing is repeating in your words what you interpreted someone else to be saying. Paraphrasing is powerful means to further the understanding of the other person and yourself, and can greatly increase the impact of another’s comments. It can translate comments so that even more people can understand them. When paraphrasing:

- Put the focus of the paraphrase on what the other person implied, not on what you wanted him/her to imply, e.g., don’t say, “I believe what you meant to say was …”. Instead, say “If I’m hearing you right, you conveyed that …?”

- Phrase the paraphrase as a question, “So you’re saying that …?”, so that the other person has the responsibility and opportunity to refine his/her original comments in response to your question.

- Put the focus of the paraphrase on the other person, e.g., if the person said, “I don’t get enough resources to do what I want,” then don’t paraphrase, “We probably all don’t get what we want, right?”

- Put the ownership of the paraphrase on yourself, e.g., “If I’m hearing you right …?” or “If I understand you correctly …?”

- Put the ownership of the other person’s words on him/her, e.g., say “If I understand you right, you’re saying that …?” or “… you believe that …?” or “… you feel that …?”

- In the paraphrase, use some of the words that the other person used. For example, if the other person said, “I think we should do more planning around here.” You might paraphrase, “If I’m hearing you right in this strategic planning workshop, you believe that more strategic planning should be done in our community?”

- Don’t judge or evaluate the other person’s comments, e.g., don’t say, “I wonder if you really believe that?” or “Don’t you feel out-on-a-limb making that comment?”

- You can use a paraphrase to validate your impression of the other’s comments, e.g., you could say, “So you were frustrated when …?”

- The paraphrase should be shorter than the original comments made by the other person.

- If the other person responds to your paraphrase that you still don’t understand him/her, then give the other person 1-2 chances to restate his position. Then you might cease the paraphrasing; otherwise, you might embarrass or provoke the other person.

How to Effectively Summarize

A summary is a concise overview of the most important points from a communication, whether it’s from a conversation, presentation or document. Summarizing is a very important skill for an effective communicator.

A good summary can verify that people are understanding each other, can make communications more efficient, and can ensure that the highlights of communications are captured and utilized.

When summarizing, consider the following guidelines:

- When listening or reading, look for the main ideas being conveyed.

- Look for any one major point that comes from the communication. What is the person trying to accomplish in the communication?

- Organize the main ideas, either just in your mind or written down.

- Write a summary that lists and organizes the main ideas, along with the major point of the communicator.

- The summary should always be shorter than the original communication.

- Does not introduce any new main points into the summary – if you do, make it clear that you’re adding them.

- If possible, have other readers or listeners also read your summary and tell you if it is understandable, accurate and complete.

For many related, free online resources, see the following Free Management Library’s topics:

- All About Personal and Professional Coaching

- Communications Skills

- Skills in Questioning

- Team Building

- LinkedIn Discussion Group about “Coaching for Everyone”

————————————————————————-

Carter McNamara, MBA, PhD – Authenticity Consulting, LLC – 763-971-8890 Read my blogs: Boards , Consulting and OD , and Strategic Planning .

Carter McNamara

How to Start Your Private Peer Coaching Group

Introduction Purpose of This Information The following information and resources are focused on the most important guidelines and materials for you to develop a basic, practical, and successful PCG. The information is intended for anyone, although it helps if you have at least some basic experience in working with groups. All aspects of this offering …

What Makes for An Effective Leader?

© Copyright Sandra Larson, Minneapolis, MN. Sandra Larson, previous executive director of MAP for Nonprofits, was once asked to write her thoughts on what makes an effective leader. Her thoughts are shared here to gel other leaders to articulate their own thoughts on what makes them a good leader. Also consider Related Library Topics Passion …

How to Design Leadership Training Development Programs

Written by Carter McNamara, MBA, Ph.D., Authenticity Consulting, LLC. Copyright; Authenticity Consulting, LLC (Note that there are separate topics about How to Design Your Management Development Program and How to Design Your Supervisor Development Program. Those two topics are very similar to this topic about leadership training programs, but with a different focus.) Sections of …

What is the One Best Model of Group Coaching?

Group and team coaching are fast becoming a major approach in helping more organizations and individuals to benefit from the power of coaching. There are numerous benefits, including that it can spread core coaching more quickly, be less expensive than one-on-one coaching, provide more diverse perspectives in coaching, and share support and accountabilities to get …

Avoiding Confusion in Learning and Development Conversations

It’s fascinating how two people can be talking about groups and individuals in almost any form of learning and development, but be talking about very different things. You can sense their confusion and frustration. Here’s a handy tip that we all used in a three-day, peer coaching group workshop in the Kansas Leadership Center, and …

Reflections on the Question: “Is it Group or Team Coaching?”

I started my first coaching groups in 1983 and since then, have worked with 100s of groups and taught hundreds of others how do design and coach/facilitate the groups. I’ve also read much of the literature about group and team coaching. Here are some of my lessons learned — sometimes painfully. 1. The most important …

Single-Project and Multi-Project Formats of Action Learning

In the early 1980s, I started facilitating Action Learning where all set members were working on the same problem or project (single-project Action Learning, or SPAL). My bias in Action Learning has always been to cultivate self-facilitated groups, somewhat in the spirit of Reginald Revans’ preferences for those kinds of sets, too. However, at least …

The Applications of Group Coaching - Part 2

In Part 1, we described group coaching, starting with a description of coaching and then group coaching. We also listed many powerful applications of group coaching. Basic Considerations in Designing Group Coaching It is very important to customize the design of group coaching to the specific way that you want to use it. There are …

6 Steps to Resolving a Level 1 Disagreement

A disagreement arises in a meeting you are facilitating. This is an inevitable scenario in many types of meetings where a group needs to come to critical decisions - such as strategic planning or issue resolution sessions. How do you - the person in the room responsible for building consensus - resolve it without breaking group dynamics or creating a tense environment of division? It's a tough job, but you can (and need to) do it. Here's one way to resolve the disagreement.

Empowering Action Learners and Coaches: Free Online Resources

(The aim of this blog has always been to provide highly practical guidelines, tools and techniques for all types of Action Learners and coaches. Here are links to some of the world’s largest collections of free, well-organized resources for practitioners in both fields.) The Action Learning framework and the field of personal and professional coaching …

Action Learning Certification: Exploring Independent Standards

The field of personal and professional coaching has a widely respected and accepted, independent certifying body called the International Coach Federation. It is independent in that it does not concurrently promote its own model of coaching — it does not engage in that kind of conflict of interest. There seems to be a mistaken impression …

Effective Recording Techniques: Capturing Information

As a meeting facilitator, you must employ several techniques for recording information in a session to make it a manageable process. When you are gathering input, ideas, and issues from your group at warp speed, it will inevitably be challenging and tedious. Here are a few methods to make the process easier.

What March Madness teaches us about facilitation

Here we go. It's now down to the Final Four in this year's NCAA March Madness. As I analyze the four remaining teams and highlights of their seasons (and take a look at my butchered bracket!), I think about how March Madness and - more importantly - the game of basketball really does embody what we know about facilitation. Let's consider that thought for these reasons.

What kind of a Tough Leader are you?

Alan Frohman Articles, books and experience identify at least two types of tough leaders. Each is demanding, but in very different ways. The first type is described in these terms: Critical Judgmental Lacks compassion Micromanaging Disrespectful They rarely view themselves that way. But that is how their people describe them. They see themselves as being …

6 Things You’ll Hear in an Unprepared Meeting

Many times, we, as facilitators, are not prepared (or ill prepared) for meetings, and that leads to some horrific results – including those feelings you experienced while watching a fellow facilitator suffer through a meeting. What are some things you'll hear in an unprepared meeting? Look out for these words. And, don't let this happen to you.

Privacy Overview

Effective Conversation: The Power of Active Listening and Paraphrasing

In today’s fast-paced world, effective communication is more important than ever. Whether you’re engaging in a personal conversation or a professional discussion, the ability to actively listen and paraphrase can make all the difference in the quality of your interactions. In this blog post, we will explore tips on how to have an effective conversation by mastering active listening and paraphrasing.

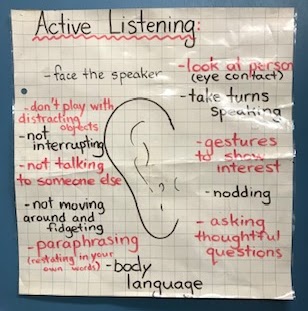

The Power of Active Listening

Active listening is a fundamental skill that allows you to fully understand and engage in a conversation. It involves giving your full attention to the speaker, both verbally and non-verbally. Here are some tips to enhance your active listening skills:

- Maintain eye contact: By making eye contact with the speaker, you show that you are fully present and focused on what they are saying.

- Use non-verbal cues: Nodding your head, smiling, or leaning in slightly can encourage the speaker to continue and feel heard.

- Avoid interrupting: Let the speaker finish their thoughts before interjecting. Interrupting can disrupt the flow of conversation and make the speaker feel unheard.

- Ask clarifying questions: If you are unsure about something the speaker said, ask for clarification. This demonstrates your genuine interest and ensures that you have a clear understanding of their message.

The Art of Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is the process of restating what the speaker has said in your own words. It shows that you are actively listening and helps to clarify and confirm your understanding. Here are some techniques to master the art of paraphrasing:

- Summarize the main points: After the speaker has finished talking, summarize the main points they made. This not only shows that you were paying attention but also helps to reinforce the key ideas.

- Reflect the speaker’s emotions: Pay attention to the speaker’s tone of voice and body language. Try to reflect their emotions when paraphrasing to show empathy and understanding.

- Avoid using the same words: Instead of repeating the speaker’s exact words, rephrase their message using your own language. This demonstrates that you have processed their message and are providing your own interpretation.

By mastering active listening and paraphrasing, you can have more meaningful and productive conversations. These skills not only help you to understand others better but also enable you to express your own thoughts and ideas more effectively. Practice these tips in your everyday conversations, and watch as your communication skills improve!

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Power of Communication: The Principle of Paraphrasing

This lesson is a part of an audio course the power of communication: learning to communicate effectively by hans fleurimont.

Let's talk about paraphrasing and why in my view it is a very important principle to know and to understand. A paraphrase is an accurate response to the person who’s speaking, which states the essence of the speaker’s words in the listener’s own words. To put it another way to paraphrase is to express the meaning of something written or spoken using different words in order to achieve greater clarity. (And that what I just did was an example of paraphrasing).

So if I’m talking to someone and they’re explaining something to me, what I would do is paraphrase what they just said but in my own words. For example, let’s say that my wife is talking about her day and what she did at work and she is explaining the process of doing someone's taxes to me. So she says:

“One of my clients got all upset because they didn’t receive the whole amount they expected from their tax return and they threw a fit in the office.”

And then I would say “So they got mad because it was less than what they thought.” It’s as simple as that. You can paraphrase what someone says to you and you can also paraphrase something you said (Like how I did earlier). So now let’s talk about what goes into paraphrasing.

The Essential Elements of Paraphrasing Are:

- Condensed. A good paraphrase is accurate. When people begin using this technique, they tend to be too wordy. A paraphrase should be shorter than the speaker’s statement.

- Only the essentials. An effective paraphrase reflects only the essentials of the speaker’s message. It cuts through the clutter of details and focuses on what is central in the original message.

- Focus on the Information. Another Characteristic of a paraphrase is that it focuses on the content of the message. It deals with the facts or ideas rather than the emotions the sender is expressing. Even though a firm distinction between facts and feelings is artificial, paraphrasing focuses on the content of the message.

- Stated in the listener’s own words. The listener summarizes their understanding of what they heard in their own words. Repeating the speaker’s exact words (which is parroting) usually stifles or dry’s up a conversation, while paraphrasing, when used appropriately, can contribute greatly to the communication between people.

Example of Paraphrasing

Here is another example of paraphrasing:

Person A says “I want to bring you up to speed on a particular project. I talked with Claire, and she has been meeting with people at the state level for weeks about the funding. Things sound really up in the air. We should proceed with caution until we know more.”

One way we can paraphrase this statement is by saying “So the whole project is dependent on whether or not state funding goes through.”

This is just a quick example but there are many ways you can use paraphrases.

Always remember paraphrasing is very useful because it shows the person or people we are talking to that we are actively listening to them and that we understand what they are communicating with us. It is also helpful when you are teaching or giving instructions to a group of people. To paraphrase, it's a great principle to use when communicating. Believe me, the ability to paraphrase helps a whole lot especially in meetings with important people in your career and life.

Hans Fleurimont

Listen to the full course.

The Power of Communication: Learning to Communicate Effectively

Related courses.

Negotiation Skills

Persuasion Science Masterclass

Handling Difficult People

Share this course, learn while doing something else.

Enjoy unlimited access to 2,000+ original audio lessons created by world-renowned experts.

Bridging Gaps, Finding Peace

Mastering The Art Of Paraphrasing For Effective Communication

Have you ever been in a conversation where you felt like the other person just wasn’t getting your point? Or have you ever been in a situation where you misunderstood what someone else was trying to say? Miscommunication can be frustrating, and it can often lead to conflicts or missed opportunities.

However, mastering the art of paraphrasing can help you become a more effective communicator and avoid these kinds of misunderstandings.

Consider this scenario: You’re in a meeting with your boss, discussing a project you’ve been working on. Your boss suggests that you make some changes to the design, but you’re not sure you understand exactly what she’s asking for.

You could nod your head and pretend to understand, or you could ask for clarification. But what if there was a third option? What if you could paraphrase what your boss said to make sure you understood correctly?

This is where the art of paraphrasing comes in. By restating what someone else has said in your own words, you can demonstrate that you are actively listening and processing the information, and you can avoid any misunderstandings that might arise from miscommunication.

Table of Contents

Key Takeaways

– Paraphrasing is a valuable skill for effective communication in both personal and professional settings. – Successful paraphrasing involves restating the message while maintaining its original meaning and checking for understanding. – Understanding non-verbal cues and asking clarifying questions are important in active listening and mastering the art of paraphrasing. – Poor communication can lead to conflicts, missed opportunities, and workplace mistakes, making effective communication strategies crucial for success.

Understanding the Importance of Effective Communication

Misunderstandings, missed deadlines, and conflicts can all be traced back to communication breakdowns. On the other hand, when people communicate well, businesses thrive, projects are completed on time, and personal relationships flourish. The benefits of effective communication in the workplace are manifold. It fosters teamwork, boosts morale, increases productivity, and leads to better decision-making.

Moreover, communication is also essential in personal relationships. A lack of communication can lead to misunderstandings, mistrust, and resentment. On the other hand, effective communication can help build stronger, healthier relationships by fostering understanding, empathy, and connection.

Whether you’re dealing with colleagues, clients, or loved ones, effective communication is key to building trust, resolving conflicts, and achieving your goals. With that said, let’s move on to the basics of paraphrasing.

The Basics of Paraphrasing

Then, you should use synonyms and different sentence structures to rephrase the information in your own words.

Finally, it’s crucial to avoid plagiarism by ensuring that your paraphrase isn’t too similar to the original text.

By following these guidelines, you can effectively communicate complex ideas without copying someone else’s work.

Identifying Key Points

Identifying key points is crucial for effective paraphrasing, as it allows for a clear understanding of the main ideas being presented. When identifying keywords, it’s important to keep in mind the overall message that the author’s trying to convey. This means reading and re-reading the text to ensure that you have a good grasp of the main ideas and concepts being presented.

Once you have identified the key points, you can then begin to summarize the information in your own words. Summarizing information involves taking the key points and presenting them in a concise and clear manner. This requires a deep understanding of the text and the ability to rephrase the information in a way that accurately reflects the author’s intent.

By identifying key points and summarizing information, you can effectively communicate the main ideas of a text to others. In the next section, we’ll explore how to use synonyms and different sentence structures to further enhance your paraphrasing skills.

Using Synonyms and Different Sentence Structures

Once you’ve got a firm grasp of the main ideas in the text, it’s time to start using synonyms and different sentence structures to give your paraphrasing a bit of flair and personality.

Using synonyms is one of the most effective techniques in paraphrasing. This method involves replacing words with their equivalents, which helps to enhance your understanding of the text and gives you the freedom to express the same idea in different ways. Synonyms also help to avoid repetition, which can make your writing sound monotonous.

Another effective technique is using different sentence structures. This involves changing the order of words in a sentence or using a different grammatical structure while maintaining the meaning of the original text. This technique not only adds creativity to your paraphrasing but also helps to clarify complex ideas. By using different sentence structures, you can convey the same idea in a more concise and easily understandable way.

These techniques of using synonyms and different sentence structures are essential for effective paraphrasing and creative expression, which helps you to communicate your ideas more effectively.

As you continue to hone your paraphrasing skills, it’s important to remember to avoid plagiarism. One way to do this is to always give credit where it’s due by citing your sources. This will not only help you avoid plagiarism but also show that you’ve done your research and can be trusted as a reliable source of information.

Avoiding Plagiarism

To avoid getting into trouble with plagiarism, it’s crucial to always give credit where credit is due by citing your sources. Plagiarism prevention is an essential part of mastering the art of paraphrasing for effective communication. When you use someone else’s words or ideas, you must acknowledge the original source in your writing. This is not only an ethical responsibility but also a legal requirement.

Different citation guidelines exist, such as APA, MLA, and Chicago, and it’s essential to follow them accurately to avoid plagiarism. By doing so, you demonstrate your respect for the work of others and establish your credibility as a writer. Incorporating citation guidelines into your writing may seem complicated, but it’s worth the effort. There are various online tools and resources available to help you with citations, such as citation generators and writing guides.

Knowing how to avoid plagiarism and cite your sources correctly is an essential skill in academic writing, professional communication, and even everyday life. By doing so, you demonstrate your integrity and commitment to ethical behavior. As you develop your paraphrasing skills, remember to keep these guidelines in mind to ensure that your writing is both effective and ethical.

Transitioning into the next section on listening skills, it’s important to remember that effective communication involves both speaking and listening.

Listening Skills

Additionally, it’s important to pay attention to non-verbal cues such as body language and tone of voice, as these can provide valuable insight into the speaker’s emotions and intentions.

Finally, asking clarifying questions can help ensure that you fully understand the speaker’s message and avoid misunderstandings.

Active Listening

If you want to become a better communicator, active listening is crucial. You should try to actively engage with the speaker, making eye contact and giving nonverbal cues like nodding. This will show the speaker that you’re fully present and interested in what they have to say.

To actively listen, you should also avoid interrupting the speaker or thinking about your response while they’re still talking. Instead, focus on understanding their message and ask clarifying questions if needed. By doing so, you can gain a deeper understanding of the speaker’s perspective and build stronger relationships.

Understanding non-verbal cues is also an important aspect of effective communication skills.

Understanding Non-Verbal Cues

You can truly connect with others by paying attention to their body language and facial expressions. Body language interpretation is a crucial aspect of effective communication. It involves understanding the non-verbal cues that people give off, such as their posture, gestures, and facial expressions. By interpreting these cues, you can gain insight into their thoughts and emotions, and respond accordingly.

This skill is particularly important in situations where verbal communication is limited, such as in a noisy environment or when communicating with someone who speaks a different language. Developing your emotional intelligence is key to understanding non-verbal cues. Emotional intelligence involves being aware of your own emotions and those of others, and using this awareness to guide your behavior.

By developing your emotional intelligence, you can become more attuned to the emotions of others, and better able to interpret their non-verbal cues. This can help you to build stronger relationships, resolve conflicts, and communicate more effectively.

In the next section, we’ll discuss how asking clarifying questions can further enhance your communication skills.

Asking Clarifying Questions

Asking clarifying questions can be a game-changer in improving your communication skills, but don’t forget that it’s all about being a VIP – a Very Inquisitive Person.

Clarifying intentions is key to effective communication. When someone is speaking, it’s important to actively listen to what they’re saying, and clarify their intentions by asking questions. Doing so not only ensures that you understand their message, but also shows that you care about what they have to say.

Active listening techniques are crucial in asking clarifying questions. When you’re listening to someone, make sure to give them your full attention. This means avoiding distractions and focusing on what they’re saying.

Additionally, try to reflect back on what they’ve said and rephrase it in your own words. This will not only help you better understand their message, but also show that you’re actively engaged in the conversation.

Remember, asking clarifying questions is all about being curious and wanting to understand others better.

Contextual Understanding

Contextual cues such as the tone of the conversation, body language, and even the location can provide important information that can help you understand the meaning behind the words being spoken.

Language nuances, such as idioms and cultural references, can also provide important context that can help you accurately paraphrase what’s being said.

To truly master paraphrasing, you must have a deep understanding of the context in which the conversation is taking place. This involves actively listening to the speaker and paying close attention to the details of the conversation.

By doing so, you’ll be able to accurately convey the message being conveyed without misinterpreting any of the contextual cues.

Once you have a thorough understanding of the context, you can then begin to practice your paraphrasing techniques to ensure effective communication.

Practice Techniques

There are several techniques and exercises that you can use to improve your skills, such as summarizing, reflecting, and clarifying. By using these techniques, you can better understand and restate what others are saying in a way that shows you have truly listened and understood their point of view.

Real life scenarios provide the best opportunities to practice your paraphrasing skills. Applying paraphrasing in everyday situations can help you gain confidence in your ability to communicate effectively. For example, when talking to your friends or family, try to summarize what they are saying or ask clarifying questions.

This will not only help you improve your communication skills but will also show them that you are actively listening and engaging with what they are saying.

In the next section, we will explore how you can use these skills in professional settings.

Paraphrasing in Professional Settings

When communicating with colleagues, clients, or managers, it’s important to paraphrase to ensure that you understand their message correctly. This not only helps to avoid misunderstandings, but it also shows that you’re actively listening and engaged in the conversation.

Here are some tips for successful paraphrasing in workplace scenarios:

– Listen actively and attentively to the speaker’s message. – Use your own words to restate the message while maintaining the original meaning. – Check for understanding by asking questions or clarifying any points that are unclear.

By implementing these strategies, you can improve your communication skills and build stronger relationships with your colleagues.

In the next section, we’ll dive into how to use paraphrasing in personal settings.

Paraphrasing in Personal Settings

By restating what your partner or friend has said in your own words, you show that you’re actively listening and trying to understand their perspective. This can help prevent misunderstandings, resolve conflicts, and strengthen bonds.

Paraphrasing is also a common technique used in therapy. Therapists may use paraphrasing to help clients feel heard and validated, and to encourage them to explore their thoughts and feelings in more depth. By restating what the client has said, the therapist can help them gain clarity and insight into their situation.

Similarly, using paraphrasing in personal conversations can help you gain a deeper understanding of your loved ones, and create a stronger, more compassionate connection.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the common mistakes people make while paraphrasing.

When paraphrasing, common pitfalls include using too many of the original words, failing to capture the intended meaning, and not properly citing sources. These errors can hinder effective communication and lead to misunderstandings.

How does paraphrasing affect non-verbal communication?

When you actively listen and use body language while paraphrasing, you show the speaker that you understand and care about their message. This can improve non-verbal communication and build stronger relationships.

Can paraphrasing be used in written communication as well?

Unlock the power of written communication by incorporating the benefits of paraphrasing in writing. Paraphrasing allows for clear and concise messaging while avoiding misinterpretation. Symbolize your intent and engage your audience with this technique.

How can one judge the effectiveness of their paraphrasing skills?

To judge the effectiveness of your paraphrasing, engage in self evaluation and seek feedback mechanisms. Consider whether your paraphrases accurately convey the original message and if they are received positively by others.

Are there any cultural differences to consider while paraphrasing in a diverse setting?

When paraphrasing in a diverse setting, it’s important to be aware of cultural nuances and language barriers. Take the time to understand the cultural context and use clear, simple language to ensure effective communication.

- Recent Posts

- Why Active Listening Is Important In Communication - July 5, 2023

- What Does Active Listening Mean In Sales - July 5, 2023

- What Does Active Listening Mean In Business - July 5, 2023

Related Posts

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets & Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Social Impact

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Services

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

Matt Abrahams: The Power of the Paraphrase

An expert on public speaking shows how paraphrasing can help you navigate tricky communication situations.

November 19, 2014

A job seeker raises his hand to ask a question | Reuters/Rick Wilking

When you are giving a public presentation, don’t you hate it when you face … the dreaded question. You know the one: the emotionally loaded challenge that serves to undermine everything you presented prior. You had hoped you wouldn’t get it, but here it is. Or, you may face … the obnoxious meeting participant. You know this guy: He thinks he’s Mr. Smarty-Pants and wants everyone to know it. He ruins your meeting by going on long rants that contribute little and waste much.

These two situations can make even the most confident and calm speaker nervous. One powerful way to navigate your way through these two tricky communication situations is to rely on paraphrasing. Paraphrasing is a listening and reflecting tool where you restate what others say in your own words. The most effective paraphrases concisely capture the essence of what another speaker says. For example, at the end of your presentation a questioner asks: “In the past you have been slow to release new products. How soon will your new product be available?” You might paraphrase her question in one of the following ways:

- “You’re asking about our availability.”

- “You’d like to know about our release schedule.”

- “Our release timeline will be … ”

Effective paraphrasing affords you several benefits. In Q&A sessions, for instance, it allows you to:

Make sure you understood the question correctly. After your paraphrase, the question asker has the opportunity to correct you or refine his or her question. There is no sense in answering a question you were not asked.

Think before you respond. Paraphrasing is not very mentally taxing, so while you are speaking your paraphrase you can begin to think of your response.

Acknowledge emotions prior to addressing the issue(s). Occasionally, you may find yourself confronted with an emotionally laden question. In order to be seen as empathetic, and to get the asker to “hear” your answer, you should recognize the emotion as part of your paraphrase. To a questioner who asks, “I get really exasperated when I try to use some of your features. How are you going to make it easier to use your product?” you might say: “I hear that you have emotion around the complexity of our offering.” By acknowledging the emotion, you can more easily move beyond it to address the issue at hand. Please note that you should avoid labeling the emotion, even if the asker does. If someone seems angry, it is better to use terms such as “strong emotion,” “clear concern,” and “passion.” I have seen a number of speakers get into a labeling battle with an audience member when the speaker names a specific emotion that the asker took offense to (e.g., saying an audience member seems frustrated when he is actually angry).

Reframe the question to focus on something you feel more comfortable addressing. I am not recommending pulling a politician’s trick and pivoting to answer the question you wanted rather than the one you got. Instead, by paraphrasing, you can make the question more comfortable for you to answer. The most striking example I have come across was in a sales situation where a prospect asked the presenter: “How come your prices are ridiculously expensive?” Clearly, the paraphrase “So you’re asking about our ridiculous pricing” is not the way to go. Rather, you can reframe the issue in your paraphrase to be about a topic you are better prepared to address. For example, “So you’d like to know about our product’s value.” Price is clearly part of value, but you start by describing the value and return on investment, which will likely soften the blow of the price.

Using paraphrases can also help you in facilitation situations, such as a meeting. In meetings, paraphrasing allows you to:

Acknowledge the participant’s effort. For many people, contributing in meetings can be daunting. There are real consequences for misspeaking or sounding unprepared. By paraphrasing the contributions you get from others, you validate the person’s effort by signaling that you really listened and valued their input.

Link various questions/ideas. You can pull together disparate contributions and questions and engage different participants by relating a current statement to previous ones. For example, you might say: “Your comment about our profitability links to the question a few minutes ago about our financial outlook.”

Manage over-contributors. Someone who over-shares or dominates a meeting with his or her opinions can be very disruptive and disrespectful. If it is your meeting, then the other participants will expect you to manage the situation. If you don’t, you will lose control and potentially credibility. Paraphrasing can help you move beyond the over-contributor while looking tactful. Fortunately, even the most loquacious person needs to inhale once in a while. During a pause, simply paraphrase a meaningful portion of the person’s diatribe and place focus elsewhere — to another person or topic. For example, you might say, “Forrest’s point about manufacturing delays is a good one. Laurie, what do you think?” Or, “Forrest’s point about manufacturing delays is a good one. What other issues are affecting our release schedule?” In both cases, you have politely informed Forrest that he is done, and you’ve turned the focus away from him and back to your agenda.

Beginning a paraphrase can sometimes be tricky, and people often ask me for suggestions for ways to initiate their paraphrases. Try one of the following lines to help you start your paraphrase:

- “So what you are saying/asking is … ”

- “What is important to you is … ”

- “You’d like to know more about … ”

- “The central idea of your question/comment is … ”

Paraphrasing has the power to help you connect with your audience, manage emotions, and steer the conversation. And once you begin to use the technique, you will realize it has the power to help you not only in presentations and meetings, but in virtually any interpersonal conversation.

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom .

Explore More

Lose yourself: the secret to finding flow and being fully present, speak your truth: why authenticity leads to better communication, when words aren’t enough: how to excel at nonverbal communication, editor’s picks.

July 25, 2014 Matt Abrahams: A Good Question Can Be the Key to a Successful Presentation A Stanford GSB lecturer and expert on public speaking explains how you can become a more compelling and confident presenter by asking – not telling – in the right situations.

March 13, 2014 Matt Abrahams: How to Make Unforgettable Presentations A Stanford lecturer and expert on public speaking explains how to ensure your audience remembers what they hear and see.

March 04, 2014 Matt Abrahams: Presentations and the Art of the Graceful Recovery A Stanford lecturer and expert on public speaking explains what to do when memory fails.

February 26, 2014 Matt Abrahams: How Do You Make a Memorable Presentation? A Stanford lecturer and expert on public speaking explains how to manage anxiety and deliver a smooth presentation.

- Priorities for the GSB's Future

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Business Transformation

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships and Prizes

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Get Involved

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- Career Advancement

- Career Change

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- Information for Recommenders

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- After You’re Admitted

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- Videos, Code & Data

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Reading Materials

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

- Founding Donors

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Program Contacts

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview

- Project Types

- Client Eligibility Criteria

- Client Screening

- ACT Leadership

- Social Innovation & Nonprofit Management Resources

- Develop Your Organization’s Talent

- Centers & Initiatives

- Student Fellowships

3 Benefits of Paraphrasing: The Skill for Learning, Writing and Communicating

Paraphrasing is the underrated skill of reinstating, clarifying or condensing the ideas of another in your own words. By paraphrasing, you can curate credible and well-developed documents, and arguments. But there’s more to paraphrasing than the final result, the process of paraphrasing engages your ability to learn actively, write well, and communicate creatively.

Paraphrasing allows you to share another’s ideas in your own words. This powerful technique is useful in both written and verbal communication, and acts as a tool for conveying information effectively. Paraphrasing is an underrated skill that is beneficial to a variety of individuals from students and writers to employees and business owners. In any setting, sharing information well is the key to good quality work and results. The process of paraphrasing itself also has a number of benefits, making you a better learner, writer and communicator.

Paraphrasing: The Active Learning Strategy

Paraphrasing requires you to think about the information you want to convey. You need to understand the meaning in order to reword and restructure the idea, and share it effectively. The process of paraphrasing encourages you to get to the core message, and improves your understanding of the material. In this way, you are actively engaging with the material . Instead of passively reading, you are breaking down the ideas and concepts. Rather than slotting information into your writing, you’re reworking and tailoring it to your needs and your audience.

Paraphrasing can improve your memory by encouraging you to engage with the information. The 5-step approach to paraphrasing suggests writing your first paraphrase without looking at the original material. This engages your ability to actively recall information from memory, and think of new ways to write it out, rather than simply trying to memorise what you read word for word. After your first draft, you’ll revisit the original material to check if your work conveys the same meaning, this part of the process can further strengthen memory. You’re again revisiting the material in a way that is active and assessing your understanding. Likewise, the practice of paraphrasing improves your ability to convey information, ensuring that it is well-written and tailored to your audience.

This learning method is particularly useful for exams. You’ll learn the material well, developing a deep understanding and continue to refine this as you paraphrase the information. You’ll also be practising your ability to share this information in a way that is well-written, avoids plagiarism and engages your audience. This means, you’ll be able to easily add these ideas into your assignments or exams, having already taken the time to understand the ideas deeply and even practised sharing this information. You’ll be able to show the depth of your learning through paraphrasing, proving you understand the bigger picture and the finer details.

Paraphrasing: The Technique for Improving Writing Ability

Once you’ve understood the concept well, the process of paraphrasing can improve your writing ability in a variety of ways. You’ll improve your vocabulary by making use of synonyms and identifying key words. You might also switch between word categories, using a noun instead of a verb or changing adjectives into adverbs. Overtime, this will make you a better writer. Paraphrasing is more than changing a few words and can involve switching between the active or passive voice, this can improve your ability to distinguish between the two. Effective paraphrasing also involves playing around with sentence structure, you might utilise shorter or longer sentences to convey the idea at hand.

These benefits can still be found even when using paraphrasing tools . You’ll still have to test your understanding by assessing the paraphrase the tool produced. Likewise, you’ll be exposed to new ways of writing things, new words, sentence structures, and organisation. You’ll learn how to pick out the paraphrasing styles that do or don’t work for your writing. Beyond the more technical aspects of writing, paraphrasing can also teach you how to communicate more clearly. You might rearrange the information to emphasise a particular point, or simplify the language to make it accessible to your audience. This improves your ability to clarify the ideas of the original material, and make ideas that might be overly complex, easier to digest.

Paraphrasing: The Skill for Better Communication

Finally, paraphrasing can make you a better and more creative communicator. By engaging in the process of paraphrasing, you’re developing your ability to share one idea in a variety of ways. For this to be engaging, you have to get creative. You might play around with the tone, switching between formal, informal, casual, or persuasive. Imagine a business launching a new product, communicating the idea to various internal teams, and customers, each would require a different approach and yet the meaning behind the information would remain the same.

You might ask questions such as, how can I tailor this information to my audience? How can I bring this aspect of the idea to life? This highlights how paraphrasing can really exercise your ability to communicate creatively. Similarly, paraphrasing can teach you how to share ideas in your own personal way. Whether you’re sharing an idea with a friend, or on social media, you’ll find you can share information in your own personal style while still retaining the original meaning. This can make ideas more accessible and relatable to those in your circle. Additionally, this can prove to be a useful skill in your career, studies or creative endeavours.

Do you want to achieve more with your time?

98% of users say genei saves them time and helps them work more productively. Why don’t you join them?

About genei

genei is an AI-powered research tool built to help make the work and research process more efficient. Our studies show genei can help improve reading speeds by up to 70%! Revolutionise your research process.

Articles you may like:

Find out how genei can benefit you

- INTERPERSONAL SKILLS

- Communication Skills

- Verbal Communication

Search SkillsYouNeed:

The SkillsYouNeed Guide to Interpersonal Skills

Interpersonal Skills:

- A - Z List of Interpersonal Skills

- Interpersonal Skills Self-Assessment

- What is Communication?

- Interpersonal Communication Skills

- Tips for Effective Interpersonal Communication

- Principles of Communication

- Barriers to Effective Communication

- Avoiding Common Communication Mistakes

- Social Skills

- Getting Social Online

- Giving and Receiving Feedback

- Improving Communication

- Interview Skills

- Telephone Interviews

- Interviewing Skills

- Business Language Skills

- The Ladder of Inference

- Listening Skills

- Top Tips for Effective Listening

- The 10 Principles of Listening

- Effective Listening Skills

- Barriers to Effective Listening

- Types of Listening

- Active Listening

- Mindful Listening

- Empathic Listening

- Listening Misconceptions

- Non-Verbal Communication

- Personal Appearance

- Body Language

- Non-Verbal Communication: Face and Voice

- Effective Speaking

- Conversational Skills

- How to Keep a Conversation Flowing

- Conversation Tips for Getting What You Want

- Giving a Speech

- Questioning Skills and Techniques

- Types of Question

- Clarification

- Emotional Intelligence

- Conflict Resolution and Mediation Skills

- Customer Service Skills

- Team-Working, Groups and Meetings

- Decision-Making and Problem-Solving

- Negotiation and Persuasion Skills

- Personal and Romantic Relationship Skills

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

However good you think your listening skills are, the only person who can tell you if you have understood correctly or not is the speaker. Therefore, as an extension of good listening skills, you need to develop the ability to reflect words and feelings and to clarify that you have understood them correctly.

It is often important that you and the speaker agree that what you understand is a true representation of what was meant to be said.

As well as understanding and reflecting the verbal messages of the speaker it is important to try to understand the emotions - this page explains how to use reflection effectively to help you build greater understanding of not only what is being said but the content, feeling and meaning of messages.

What is Reflecting?

Reflecting is the process of paraphrasing and restating both the feelings and words of the speaker. The purposes of reflecting are:

- To allow the speaker to 'hear' their own thoughts and to focus on what they say and feel.

- To show the speaker that you are trying to perceive the world as they see it and that you are doing your best to understand their messages.

- To encourage them to continue talking.

Reflecting does not involve you asking questions, introducing a new topic or leading the conversation in another direction. Speakers are helped through reflecting as it not only allows them to feel understood, but it also gives them the opportunity to focus their ideas. This in turn helps them to direct their thoughts and further encourages them to continue speaking.

Two Main Techniques of Reflecting:

Mirroring is a simple form of reflecting and involves repeating almost exactly what the speaker says.

Mirroring should be short and simple. It is usually enough to just repeat key words or the last few words spoken. This shows you are trying to understand the speakers terms of reference and acts as a prompt for him or her to continue. Be aware not to over mirror as this can become irritating and therefore a distraction from the message.

Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing involves using other words to reflect what the speaker has said. Paraphrasing shows not only that you are listening, but that you are attempting to understand what the speaker is saying.

It is often the case that people 'hear what they expect to hear' due to assumptions, stereotyping or prejudices. When paraphrasing, it is of utmost importance that you do not introduce your own ideas or question the speakers thoughts, feelings or actions. Your responses should be non-directive and non-judgemental.

It is very difficult to resist the temptation to ask questions and when this technique is first used, reflecting can seem very stilted and unnatural. You need to practice this skill in order to feel comfortable.

Reflecting Content, Feeling and Meaning

The most immediate part of a speaker's message is the content, in other words those aspects dealing with information, actions, events and experience, as verbalised by them.

Reflecting content helps to give focus to the situation but, at the same time, it is also essential to reflect the feelings and emotions expressed in order to more fully understand the message.

This helps the speaker to own and accept their own feelings, for quite often a speaker may talk about them as though they belong to someone else, for example using “you feel guilty” rather than “I feel guilty.”

A skilled listener will be able to reflect a speaker's feelings from body cues (non-verbal) as well as verbal messages. It is sometimes not appropriate to ask such direct questions as “How does that make you feel?” Strong emotions such as love and hate are easy to identify, whereas feelings such as affection, guilt and confusion are much more subtle. The listener must have the ability to identify such feelings both from the words and the non-verbal cues, for example body language, tone of voice, etc.

As well as considering which emotions the speaker is feeling, the listener needs to reflect the degree of intensity of these emotions. For example:

Reflecting needs to combine content and feeling to truly reflect the meaning of what the speaker has said. For example:

“ I just don't understand my boss. One minute he says one thing and the next minute he says the opposite. ”

“ You feel very confused by him? ”

Reflecting meaning allows the listener to reflect the speaker's experiences and emotional response to those experiences. It links the content and feeling components of what the speaker has said.

You may also be interested in our pages: What is Empathy? and Understanding Others .

Guidelines for Reflecting

- Be natural.

- Listen for the basic message - consider the content, feeling and meaning expressed by the speaker.

- Restate what you have been told in simple terms.

- When restating, look for non-verbal as well as verbal cues that confirm or deny the accuracy of your paraphrasing. (Note that some speakers may pretend you have got it right because they feel unable to assert themselves and disagree with you.)

- Do not question the speaker unnecessarily.

- Do not add to the speaker's meaning.

- Do not take the speaker's topic in a new direction.

- Always be non-directive and non-judgemental.

Further Reading from Skills You Need

Our Communication Skills eBooks

Learn more about the key communication skills you need to be an effective communicator.

Our eBooks are ideal for anyone who wants to learn about or develop their communication skills, and are full of easy-to-follow practical information and exercises.

Continue to: Clarifying Giving and Receiving Feedback

See Also: The 10 Principles of Listening Questioning Skills and Techniques Note-Taking | Conflict Resolution

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 12 min read

How to Paraphrase and Summarize Work

Summing up key ideas in your own words.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Imagine you're preparing a presentation for your CEO. You asked everyone in your team to contribute, and they all had plenty to say!

But now you have a dozen reports, all in different styles, and your CEO says that she can spare only 10 minutes to read the final version. What do you do?

The solution is to paraphrase and summarize the reports, so your boss gets only the key information that she needs, in a form that she can process quickly.

In this article, we explain how to paraphrase and how to summarize, and how to apply these techniques to text and the spoken word. We also explore the differences between the two skills, and point out the pitfalls to avoid.

What Is Paraphrasing?

When you paraphrase, you use your own words to express something that was written or said by another person.

Putting it into your own words can clarify the message, make it more relevant to your audience , or give it greater impact.

You might use paraphrased material to support your own argument or viewpoint. Or, if you're putting together a report , presentation or speech , you can use paraphrasing to maintain a consistent style, and to avoid lengthy quotations from the original text or conversation.

Paraphrased material should keep its original meaning and (approximate) length, but you can use it to pick out a single point from a longer discussion.

What Is Summarizing?

In contrast, a summary is a brief overview of an entire discussion or argument. You might summarize a whole research paper or conversation in a single paragraph, for example, or with a series of bullet points, using your own words and style.

People often summarize when the original material is long, or to emphasize key facts or points. Summaries leave out detail or examples that may distract the reader from the most important information, and they simplify complex arguments, grammar and vocabulary.

Used correctly, summarizing and paraphrasing can save time, increase understanding, and give authority and credibility to your work. Both tools are useful when the precise wording of the original communication is less important than its overall meaning.

How to Paraphrase Text

To paraphrase text, follow these four steps:

1. Read and Make Notes

Carefully read the text that you want to paraphrase. Highlight, underline or note down important terms and phrases that you need to remember.

2. Find Different Terms

Find equivalent words or phrases (synonyms) to use in place of the ones that you've picked out. A dictionary, thesaurus or online search can be useful here, but take care to preserve the meaning of the original text, particularly if you're dealing with technical or scientific terms.

3. Put the Text into Your Own Words

Rewrite the original text, line by line. Simplify the grammar and vocabulary, adjust the order of the words and sentences, and replace "passive" expressions with "active" ones (for example, you could change "The new supplier was contacted by Nusrat" to "Nusrat contacted the new supplier").

Remove complex clauses, and break longer sentences into shorter ones. All of this will make your new version easier to understand .

4. Check Your Work

Check your work by comparing it to the original. Your paraphrase should be clear and simple, and written in your own words. It may be shorter, but it should include all of the necessary detail.

Paraphrasing: an Example

Despite the undoubted fact that everyone's vision of what constitutes success is different, one should spend one's time establishing and finalizing one's personal vision of it. Otherwise, how can you possibly understand what your final destination might be, or whether or not your decisions are assisting you in moving in the direction of the goals which you've set yourself?

The two kinds of statement – mission and vision – can be invaluable to your approach, aiding you, as they do, in focusing on your primary goal, and quickly identifying possibilities that you might wish to exploit and explore.

We all have different ideas about success. What's important is that you spend time defining your version of success. That way, you'll understand what you should be working toward. You'll also know if your decisions are helping you to move toward your goals.

Used as part of your personal approach to goal-setting, mission and vision statements are useful for bringing sharp focus to your most important goal, and for helping you to quickly identify which opportunities you should pursue.

How to Paraphrase Speech

In a conversation – a meeting or coaching session, for example – paraphrasing is a good way to make sure that you have correctly understood what the other person has said.

This requires two additional skills: active listening and asking the right questions .

Useful questions include:

- If I hear you correctly, you're saying that…?

- So you mean that…? Is that right?

- Did I understand you when you said that…?

You can use questions like these to repeat the speaker's words back to them. For instance, if the person says, "We just don't have the funds available for these projects," you could reply: "If I understand you correctly, you're saying that our organization can't afford to pay for my team's projects?"

This may seem repetitive, but it gives the speaker the opportunity to highlight any misunderstandings, or to clarify their position.

When you're paraphrasing conversations in this way, take care not to introduce new ideas or information, and not to make judgments on what the other person has said, or to "spin" their words toward what you want to hear. Instead, simply restate their position as you understand it.

Sometimes, you may need to paraphrase a speech or a presentation. Perhaps you want to report back to your team, or write about it in a company blog, for example.

In these cases it's a good idea to make summary notes as you listen, and to work them up into a paraphrase later. (See How to Summarize Text or Speech, below.)

How to Summarize Text or Speech

Follow steps 1-5 below to summarize text. To summarize spoken material – a speech, a meeting, or a presentation, for example – start at step three.

1. Get a General Idea of the Original

First, speed read the text that you're summarizing to get a general impression of its content. Pay particular attention to the title, introduction, conclusion, and the headings and subheadings.

2. Check Your Understanding

Build your comprehension of the text by reading it again more carefully. Check that your initial interpretation of the content was correct.

3. Make Notes

Take notes on what you're reading or listening to. Use bullet points, and introduce each bullet with a key word or idea. Write down only one point or idea for each bullet.

If you're summarizing spoken material, you may not have much time on each point before the speaker moves on. If you can, obtain a meeting agenda, a copy of the presentation, or a transcript of the speech in advance, so you know what's coming.

Make sure your notes are concise, well-ordered, and include only the points that really matter.

The Cornell Note-Taking System is an effective way to organize your notes as you write them, so that you can easily identify key points and actions later. Our article, Writing Meeting Notes , also contains plenty of useful advice.

4. Write Your Summary