How to Write an Article Critique Step-by-Step

Table of contents

- 1 What is an Article Critique Writing?

- 2 How to Critique an Article: The Main Steps

- 3 Article Critique Outline

- 4 Article Critique Formatting

- 5 How to Write a Journal Article Critique

- 6 How to Write a Research Article Critique

- 7 Research Methods in Article Critique Writing

- 8 Tips for writing an Article Critique

Do you know how to critique an article? If not, don’t worry – this guide will walk you through the writing process step-by-step. First, we’ll discuss what a research article critique is and its importance. Then, we’ll outline the key points to consider when critiquing a scientific article. Finally, we’ll provide a step-by-step guide on how to write an article critique including introduction, body and summary. Read more to get the main idea of crafting a critique paper.

What is an Article Critique Writing?

An article critique is a formal analysis and evaluation of a piece of writing. It is often written in response to a particular text but can also be a response to a book, a movie, or any other form of writing. There are many different types of review articles . Before writing an article critique, you should have an idea about each of them.

To start writing a good critique, you must first read the article thoroughly and examine and make sure you understand the article’s purpose. Then, you should outline the article’s key points and discuss how well they are presented. Next, you should offer your comments and opinions on the article, discussing whether you agree or disagree with the author’s points and subject. Finally, concluding your critique with a brief summary of your thoughts on the article would be best. Ensure that the general audience understands your perspective on the piece.

How to Critique an Article: The Main Steps

If you are wondering “what is included in an article critique,” the answer is:

An article critique typically includes the following:

- A brief summary of the article .

- A critical evaluation of the article’s strengths and weaknesses.

- A conclusion.

When critiquing an article, it is essential to critically read the piece and consider the author’s purpose and research strategies that the author chose. Next, provide a brief summary of the text, highlighting the author’s main points and ideas. Critique an article using formal language and relevant literature in the body paragraphs. Finally, describe the thesis statement, main idea, and author’s interpretations in your language using specific examples from the article. It is also vital to discuss the statistical methods used and whether they are appropriate for the research question. Make notes of the points you think need to be discussed, and also do a literature review from where the author ground their research. Offer your perspective on the article and whether it is well-written. Finally, provide background information on the topic if necessary.

When you are reading an article, it is vital to take notes and critique the text to understand it fully and to be able to use the information in it. Here are the main steps for critiquing an article:

- Read the piece thoroughly, taking notes as you go. Ensure you understand the main points and the author’s argument.

- Take a look at the author’s perspective. Is it powerful? Does it back up the author’s point of view?

- Carefully examine the article’s tone. Is it biased? Are you being persuaded by the author in any way?

- Look at the structure. Is it well organized? Does it make sense?

- Consider the writing style. Is it clear? Is it well-written?

- Evaluate the sources the author uses. Are they credible?

- Think about your own opinion. With what do you concur or disagree? Why?

Article Critique Outline

When assigned an article critique, your instructor asks you to read and analyze it and provide feedback. A specific format is typically followed when writing an article critique.

An article critique usually has three sections: an introduction, a body, and a conclusion.

- The introduction of your article critique should have a summary and key points.

- The critique’s main body should thoroughly evaluate the piece, highlighting its strengths and weaknesses, and state your ideas and opinions with supporting evidence.

- The conclusion should restate your research and describe your opinion.

You should provide your analysis rather than simply agreeing or disagreeing with the author. When writing an article review , it is essential to be objective and critical. Describe your perspective on the subject and create an article review summary. Be sure to use proper grammar, spelling, and punctuation, write it in the third person, and cite your sources.

Article Critique Formatting

When writing an article critique, you should follow a few formatting guidelines. The importance of using a proper format is to make your review clear and easy to read.

Make sure to use double spacing throughout your critique. It will make it easy to understand and read for your instructor.

Indent each new paragraph. It will help to separate your critique into different sections visually.

Use headings to organize your critique. Your introduction, body, and conclusion should stand out. It will make it easy for your instructor to follow your thoughts.

Use standard fonts, such as Times New Roman or Arial. It will make your critique easy to read.

Use 12-point font size. It will ensure that your critique is easy to read.

How to Write a Journal Article Critique

When critiquing a journal article, there are a few key points to keep in mind:

- Good critiques should be objective, meaning that the author’s ideas and arguments should be evaluated without personal bias.

- Critiques should be critical, meaning that all aspects of the article should be examined, including the author’s introduction, main ideas, and discussion.

- Critiques should be informative, providing the reader with a clear understanding of the article’s strengths and weaknesses.

When critiquing a research article, evaluating the author’s argument and the evidence they present is important. The author should state their thesis or the main point in the introductory paragraph. You should explain the article’s main ideas and evaluate the evidence critically. In the discussion section, the author should explain the implications of their findings and suggest future research.

It is also essential to keep a critical eye when reading scientific articles. In order to be credible, the scientific article must be based on evidence and previous literature. The author’s argument should be well-supported by data and logical reasoning.

How to Write a Research Article Critique

When you are assigned a research article, the first thing you need to do is read the piece carefully. Make sure you understand the subject matter and the author’s chosen approach. Next, you need to assess the importance of the author’s work. What are the key findings, and how do they contribute to the field of research?

Finally, you need to provide a critical point-by-point analysis of the article. This should include discussing the research questions, the main findings, and the overall impression of the scientific piece. In conclusion, you should state whether the text is good or bad. Read more to get an idea about curating a research article critique. But if you are not confident, you can ask “ write my papers ” and hire a professional to craft a critique paper for you. Explore your options online and get high-quality work quickly.

However, test yourself and use the following tips to write a research article critique that is clear, concise, and properly formatted.

- Take notes while you read the text in its entirety. Right down each point you agree and disagree with.

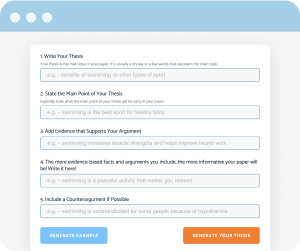

- Write a thesis statement that concisely and clearly outlines the main points.

- Write a paragraph that introduces the article and provides context for the critique.

- Write a paragraph for each of the following points, summarizing the main points and providing your own analysis:

- The purpose of the study

- The research question or questions

- The methods used

- The outcomes

- The conclusions were drawn by the author(s)

- Mention the strengths and weaknesses of the piece in a separate paragraph.

- Write a conclusion that summarizes your thoughts about the article.

- Free unlimited checks

- All common file formats

- Accurate results

- Intuitive interface

Research Methods in Article Critique Writing

When writing an article critique, it is important to use research methods to support your arguments. There are a variety of research methods that you can use, and each has its strengths and weaknesses. In this text, we will discuss four of the most common research methods used in article critique writing: quantitative research, qualitative research, systematic reviews, and meta-analysis.

Quantitative research is a research method that uses numbers and statistics to analyze data. This type of research is used to test hypotheses or measure a treatment’s effects. Quantitative research is normally considered more reliable than qualitative research because it considers a large amount of information. But, it might be difficult to find enough data to complete it properly.

Qualitative research is a research method that uses words and interviews to analyze data. This type of research is used to understand people’s thoughts and feelings. Qualitative research is usually more reliable than quantitative research because it is less likely to be biased. Though it is more expensive and tedious.

Systematic reviews are a type of research that uses a set of rules to search for and analyze studies on a particular topic. Some think that systematic reviews are more reliable than other research methods because they use a rigorous process to find and analyze studies. However, they can be pricy and long to carry out.

Meta-analysis is a type of research that combines several studies’ results to understand a treatment’s overall effect better. Meta-analysis is generally considered one of the most reliable type of research because it uses data from several approved studies. Conversely, it involves a long and costly process.

Are you still struggling to understand the critique of an article concept? You can contact an online review writing service to get help from skilled writers. You can get custom, and unique article reviews easily.

Tips for writing an Article Critique

It’s crucial to keep in mind that you’re not just sharing your opinion of the content when you write an article critique. Instead, you are providing a critical analysis, looking at its strengths and weaknesses. In order to write a compelling critique, you should follow these tips: Take note carefully of the essential elements as you read it.

- Make sure that you understand the thesis statement.

- Write down your thoughts, including strengths and weaknesses.

- Use evidence from to support your points.

- Create a clear and concise critique, making sure to avoid giving your opinion.

It is important to be clear and concise when creating an article critique. You should avoid giving your opinion and instead focus on providing a critical analysis. You should also use evidence from the article to support your points.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

Making sense of research: A guide for critiquing a paper

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Nursing, Griffith University, Meadowbrook, Queensland.

- PMID: 16114192

- DOI: 10.5172/conu.14.1.38

Learning how to critique research articles is one of the fundamental skills of scholarship in any discipline. The range, quantity and quality of publications available today via print, electronic and Internet databases means it has become essential to equip students and practitioners with the prerequisites to judge the integrity and usefulness of published research. Finding, understanding and critiquing quality articles can be a difficult process. This article sets out some helpful indicators to assist the novice to make sense of research.

Publication types

- Data Interpretation, Statistical

- Research Design

- Review Literature as Topic

- All eBooks & Audiobooks

- Academic eBook Collection

- Home Grown eBook Collection

- Off-Campus Access

- Literature Resource Center

- Opposing Viewpoints

- ProQuest Central

- Course Guides

- Citing Sources

- Library Research

- Websites by Topic

- Book-a-Librarian

- Research Tutorials

- Use the Catalog

- Use Databases

- Use Films on Demand

- Use Home Grown eBooks

- Use NC LIVE

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary vs. Secondary

- Scholarly vs. Popular

- Make an Appointment

- Writing Tools

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Summaries, Reviews & Critiques

- Writing Center

Service Alert

Article Summaries, Reviews & Critiques

- Writing an article SUMMARY

- Writing an article REVIEW

Writing an article CRITIQUE

- Citing Sources This link opens in a new window

- About RCC Library

Text: 336-308-8801

Email: [email protected]

Call: 336-633-0204

Schedule: Book-a-Librarian

Like us on Facebook

Links on this guide may go to external web sites not connected with Randolph Community College. Their inclusion is not an endorsement by Randolph Community College and the College is not responsible for the accuracy of their content or the security of their site.

A critique asks you to evaluate an article and the author’s argument. You will need to look critically at what the author is claiming, evaluate the research methods, and look for possible problems with, or applications of, the researcher’s claims.

Introduction

Give an overview of the author’s main points and how the author supports those points. Explain what the author found and describe the process they used to arrive at this conclusion.

Body Paragraphs

Interpret the information from the article:

- Does the author review previous studies? Is current and relevant research used?

- What type of research was used – empirical studies, anecdotal material, or personal observations?

- Was the sample too small to generalize from?

- Was the participant group lacking in diversity (race, gender, age, education, socioeconomic status, etc.)

- For instance, volunteers gathered at a health food store might have different attitudes about nutrition than the population at large.

- How useful does this work seem to you? How does the author suggest the findings could be applied and how do you believe they could be applied?

- How could the study have been improved in your opinion?

- Does the author appear to have any biases (related to gender, race, class, or politics)?

- Is the writing clear and easy to follow? Does the author’s tone add to or detract from the article?

- How useful are the visuals (such as tables, charts, maps, photographs) included, if any? How do they help to illustrate the argument? Are they confusing or hard to read?

- What further research might be conducted on this subject?

Try to synthesize the pieces of your critique to emphasize your own main points about the author’s work, relating the researcher’s work to your own knowledge or to topics being discussed in your course.

From the Center for Academic Excellence (opens in a new window), University of Saint Joseph Connecticut

Additional Resources

All links open in a new window.

Writing an Article Critique (from The University of Arizona Global Campus Writing Center)

How to Critique an Article (from Essaypro.com)

How to Write an Article Critique (from EliteEditing.com.au)

- << Previous: Writing an article REVIEW

- Next: Citing Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 15, 2024 9:32 AM

- URL: https://libguides.randolph.edu/summaries

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Can Med Educ J

- v.12(3); 2021 Jun

Writing, reading, and critiquing reviews

Écrire, lire et revue critique, douglas archibald.

1 University of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada;

Maria Athina Martimianakis

2 University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Why reviews matter

What do all authors of the CMEJ have in common? For that matter what do all health professions education scholars have in common? We all engage with literature. When you have an idea or question the first thing you do is find out what has been published on the topic of interest. Literature reviews are foundational to any study. They describe what is known about given topic and lead us to identify a knowledge gap to study. All reviews require authors to be able accurately summarize, synthesize, interpret and even critique the research literature. 1 , 2 In fact, for this editorial we have had to review the literature on reviews . Knowledge and evidence are expanding in our field of health professions education at an ever increasing rate and so to help keep pace, well written reviews are essential. Though reviews may be difficult to write, they will always be read. In this editorial we survey the various forms review articles can take. As well we want to provide authors and reviewers at CMEJ with some guidance and resources to be able write and/or review a review article.

What are the types of reviews conducted in Health Professions Education?

Health professions education attracts scholars from across disciplines and professions. For this reason, there are numerous ways to conduct reviews and it is important to familiarize oneself with these different forms to be able to effectively situate your work and write a compelling rationale for choosing your review methodology. 1 , 2 To do this, authors must contend with an ever-increasing lexicon of review type articles. In 2009 Grant and colleagues conducted a typology of reviews to aid readers makes sense of the different review types, listing fourteen different ways of conducting reviews, not all of which are mutually exclusive. 3 Interestingly, in their typology they did not include narrative reviews which are often used by authors in health professions education. In Table 1 , we offer a short description of three common types of review articles submitted to CMEJ.

Three common types of review articles submitted to CMEJ

More recently, authors such as Greenhalgh 4 have drawn attention to the perceived hierarchy of systematic reviews over scoping and narrative reviews. Like Greenhalgh, 4 we argue that systematic reviews are not to be seen as the gold standard of all reviews. Instead, it is important to align the method of review to what the authors hope to achieve, and pursue the review rigorously, according to the tenets of the chosen review type. Sometimes it is helpful to read part of the literature on your topic before deciding on a methodology for organizing and assessing its usefulness. Importantly, whether you are conducting a review or reading reviews, appreciating the differences between different types of reviews can also help you weigh the author’s interpretation of their findings.

In the next section we summarize some general tips for conducting successful reviews.

How to write and review a review article

In 2016 David Cook wrote an editorial for Medical Education on tips for a great review article. 13 These tips are excellent suggestions for all types of articles you are considering to submit to the CMEJ. First, start with a clear question: focused or more general depending on the type of review you are conducting. Systematic reviews tend to address very focused questions often summarizing the evidence of your topic. Other types of reviews tend to have broader questions and are more exploratory in nature.

Following your question, choose an approach and plan your methods to match your question…just like you would for a research study. Fortunately, there are guidelines for many types of reviews. As Cook points out the most important consideration is to be sure that the methods you follow lead to a defensible answer to your review question. To help you prepare for a defensible answer there are many guides available. For systematic reviews consult PRISMA guidelines ; 13 for scoping reviews PRISMA-ScR ; 14 and SANRA 15 for narrative reviews. It is also important to explain to readers why you have chosen to conduct a review. You may be introducing a new way for addressing an old problem, drawing links across literatures, filling in gaps in our knowledge about a phenomenon or educational practice. Cook refers to this as setting the stage. Linking back to the literature is important. In systematic reviews for example, you must be clear in explaining how your review builds on existing literature and previous reviews. This is your opportunity to be critical. What are the gaps and limitations of previous reviews? So, how will your systematic review resolve the shortcomings of previous work? In other types of reviews, such as narrative reviews, its less about filling a specific knowledge gap, and more about generating new research topic areas, exposing blind spots in our thinking, or making creative new links across issues. Whatever, type of review paper you are working on, the next steps are ones that can be applied to any scholarly writing. Be clear and offer insight. What is your main message? A review is more than just listing studies or referencing literature on your topic. Lead your readers to a convincing message. Provide commentary and interpretation for the studies in your review that will help you to inform your conclusions. For systematic reviews, Cook’s final tip is most likely the most important– report completely. You need to explain all your methods and report enough detail that readers can verify the main findings of each study you review. The most common reasons CMEJ reviewers recommend to decline a review article is because authors do not follow these last tips. In these instances authors do not provide the readers with enough detail to substantiate their interpretations or the message is not clear. Our recommendation for writing a great review is to ensure you have followed the previous tips and to have colleagues read over your paper to ensure you have provided a clear, detailed description and interpretation.

Finally, we leave you with some resources to guide your review writing. 3 , 7 , 8 , 10 , 11 , 16 , 17 We look forward to seeing your future work. One thing is certain, a better appreciation of what different reviews provide to the field will contribute to more purposeful exploration of the literature and better manuscript writing in general.

In this issue we present many interesting and worthwhile papers, two of which are, in fact, reviews.

Major Contributions

A chance for reform: the environmental impact of travel for general surgery residency interviews by Fung et al. 18 estimated the CO 2 emissions associated with traveling for residency position interviews. Due to the high emissions levels (mean 1.82 tonnes per applicant), they called for the consideration of alternative options such as videoconference interviews.

Understanding community family medicine preceptors’ involvement in educational scholarship: perceptions, influencing factors and promising areas for action by Ward and team 19 identified barriers, enablers, and opportunities to grow educational scholarship at community-based teaching sites. They discovered a growing interest in educational scholarship among community-based family medicine preceptors and hope the identification of successful processes will be beneficial for other community-based Family Medicine preceptors.

Exploring the global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical education: an international cross-sectional study of medical learners by Allison Brown and team 20 studied the impact of COVID-19 on medical learners around the world. There were different concerns depending on the levels of training, such as residents’ concerns with career timeline compared to trainees’ concerns with the quality of learning. Overall, the learners negatively perceived the disruption at all levels and geographic regions.

The impact of local health professions education grants: is it worth the investment? by Susan Humphrey-Murto and co-authors 21 considered factors that lead to the publication of studies supported by local medical education grants. They identified several factors associated with publication success, including previous oral or poster presentations. They hope their results will be valuable for Canadian centres with local grant programs.

Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical learner wellness: a needs assessment for the development of learner wellness interventions by Stephana Cherak and team 22 studied learner-wellness in various training environments disrupted by the pandemic. They reported a negative impact on learner wellness at all stages of training. Their results can benefit the development of future wellness interventions.

Program directors’ reflections on national policy change in medical education: insights on decision-making, accreditation, and the CanMEDS framework by Dore, Bogie, et al. 23 invited program directors to reflect on the introduction of the CanMEDS framework into Canadian postgraduate medical education programs. Their survey revealed that while program directors (PDs) recognized the necessity of the accreditation process, they did not feel they had a voice when the change occurred. The authors concluded that collaborations with PDs would lead to more successful outcomes.

Experiential learning, collaboration and reflection: key ingredients in longitudinal faculty development by Laura Farrell and team 24 stressed several elements for effective longitudinal faculty development (LFD) initiatives. They found that participants benefited from a supportive and collaborative environment while trying to learn a new skill or concept.

Brief Reports

The effect of COVID-19 on medical students’ education and wellbeing: a cross-sectional survey by Stephanie Thibaudeau and team 25 assessed the impact of COVID-19 on medical students. They reported an overall perceived negative impact, including increased depressive symptoms, increased anxiety, and reduced quality of education.

In Do PGY-1 residents in Emergency Medicine have enough experiences in resuscitations and other clinical procedures to meet the requirements of a Competence by Design curriculum? Meshkat and co-authors 26 recorded the number of adult medical resuscitations and clinical procedures completed by PGY1 Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians in Emergency Medicine residents to compare them to the Competence by Design requirements. Their study underscored the importance of monitoring collection against pre-set targets. They concluded that residency program curricula should be regularly reviewed to allow for adequate clinical experiences.

Rehearsal simulation for antenatal consults by Anita Cheng and team 27 studied whether rehearsal simulation for antenatal consults helped residents prepare for difficult conversations with parents expecting complications with their baby before birth. They found that while rehearsal simulation improved residents’ confidence and communication techniques, it did not prepare them for unexpected parent responses.

Review Papers and Meta-Analyses

Peer support programs in the fields of medicine and nursing: a systematic search and narrative review by Haykal and co-authors 28 described and evaluated peer support programs in the medical field published in the literature. They found numerous diverse programs and concluded that including a variety of delivery methods to meet the needs of all participants is a key aspect for future peer-support initiatives.

Towards competency-based medical education in addictions psychiatry: a systematic review by Bahji et al. 6 identified addiction interventions to build competency for psychiatry residents and fellows. They found that current psychiatry entrustable professional activities need to be better identified and evaluated to ensure sustained competence in addictions.

Six ways to get a grip on leveraging the expertise of Instructional Design and Technology professionals by Chen and Kleinheksel 29 provided ways to improve technology implementation by clarifying the role that Instructional Design and Technology professionals can play in technology initiatives and technology-enhanced learning. They concluded that a strong collaboration is to the benefit of both the learners and their future patients.

In his article, Seven ways to get a grip on running a successful promotions process, 30 Simon Field provided guidelines for maximizing opportunities for successful promotion experiences. His seven tips included creating a rubric for both self-assessment of likeliness of success and adjudication by the committee.

Six ways to get a grip on your first health education leadership role by Stasiuk and Scott 31 provided tips for considering a health education leadership position. They advised readers to be intentional and methodical in accepting or rejecting positions.

Re-examining the value proposition for Competency-Based Medical Education by Dagnone and team 32 described the excitement and controversy surrounding the implementation of competency-based medical education (CBME) by Canadian postgraduate training programs. They proposed observing which elements of CBME had a positive impact on various outcomes.

You Should Try This

In their work, Interprofessional culinary education workshops at the University of Saskatchewan, Lieffers et al. 33 described the implementation of interprofessional culinary education workshops that were designed to provide health professions students with an experiential and cooperative learning experience while learning about important topics in nutrition. They reported an enthusiastic response and cooperation among students from different health professional programs.

In their article, Physiotherapist-led musculoskeletal education: an innovative approach to teach medical students musculoskeletal assessment techniques, Boulila and team 34 described the implementation of physiotherapist-led workshops, whether the workshops increased medical students’ musculoskeletal knowledge, and if they increased confidence in assessment techniques.

Instagram as a virtual art display for medical students by Karly Pippitt and team 35 used social media as a platform for showcasing artwork done by first-year medical students. They described this shift to online learning due to COVID-19. Using Instagram was cost-saving and widely accessible. They intend to continue with both online and in-person displays in the future.

Adapting clinical skills volunteer patient recruitment and retention during COVID-19 by Nazerali-Maitland et al. 36 proposed a SLIM-COVID framework as a solution to the problem of dwindling volunteer patients due to COVID-19. Their framework is intended to provide actionable solutions to recruit and engage volunteers in a challenging environment.

In Quick Response codes for virtual learner evaluation of teaching and attendance monitoring, Roxana Mo and co-authors 37 used Quick Response (QR) codes to monitor attendance and obtain evaluations for virtual teaching sessions. They found QR codes valuable for quick and simple feedback that could be used for many educational applications.

In Creation and implementation of the Ottawa Handbook of Emergency Medicine Kaitlin Endres and team 38 described the creation of a handbook they made as an academic resource for medical students as they shift to clerkship. It includes relevant content encountered in Emergency Medicine. While they intended it for medical students, they also see its value for nurses, paramedics, and other medical professionals.

Commentary and Opinions

The alarming situation of medical student mental health by D’Eon and team 39 appealed to medical education leaders to respond to the high numbers of mental health concerns among medical students. They urged leaders to address the underlying problems, such as the excessive demands of the curriculum.

In the shadows: medical student clinical observerships and career exploration in the face of COVID-19 by Law and co-authors 40 offered potential solutions to replace in-person shadowing that has been disrupted due to the COVID-19 pandemic. They hope the alternatives such as virtual shadowing will close the gap in learning caused by the pandemic.

Letters to the Editor

Canadian Federation of Medical Students' response to “ The alarming situation of medical student mental health” King et al. 41 on behalf of the Canadian Federation of Medical Students (CFMS) responded to the commentary by D’Eon and team 39 on medical students' mental health. King called upon the medical education community to join the CFMS in its commitment to improving medical student wellbeing.

Re: “Development of a medical education podcast in obstetrics and gynecology” 42 was written by Kirubarajan in response to the article by Development of a medical education podcast in obstetrics and gynecology by Black and team. 43 Kirubarajan applauded the development of the podcast to meet a need in medical education, and suggested potential future topics such as interventions to prevent learner burnout.

Response to “First year medical student experiences with a clinical skills seminar emphasizing sexual and gender minority population complexity” by Kumar and Hassan 44 acknowledged the previously published article by Biro et al. 45 that explored limitations in medical training for the LGBTQ2S community. However, Kumar and Hassen advocated for further progress and reform for medical training to address the health requirements for sexual and gender minorities.

In her letter, Journey to the unknown: road closed!, 46 Rosemary Pawliuk responded to the article, Journey into the unknown: considering the international medical graduate perspective on the road to Canadian residency during the COVID-19 pandemic, by Gutman et al. 47 Pawliuk agreed that international medical students (IMGs) do not have adequate formal representation when it comes to residency training decisions. Therefore, Pawliuk challenged health organizations to make changes to give a voice in decision-making to the organizations representing IMGs.

In Connections, 48 Sara Guzman created a digital painting to portray her approach to learning. Her image of a hand touching a neuron showed her desire to physically see and touch an active neuron in order to further understand the brain and its connections.

You are using an outdated browser

Unfortunately Ausmed.com does not support your browser. Please upgrade your browser to continue.

How to Critique a Research Article

Published: 01 October 2023

Let's briefly examine some basic pointers on how to perform a literature review.

If you've managed to get your hands on peer-reviewed articles, then you may wonder why it is necessary for you to perform your own article critique. Surely the article will be of good quality if it has made it through the peer-review process?

Unfortunately, this is not always the case.

Publication bias can occur when editors only accept manuscripts that have a bearing on the direction of their own research, or reject manuscripts with negative findings. Additionally, not all peer reviewers have expert knowledge on certain subject matters , which can introduce bias and sometimes a conflict of interest.

Performing your own critical analysis of an article allows you to consider its value to you and to your workplace.

Critical evaluation is defined as a systematic way of considering the truthfulness of a piece of research, its results and how relevant and applicable they are.

How to Critique

It can be a little overwhelming trying to critique an article when you're not sure where to start. Considering the article under the following headings may be of some use:

Title of Study/Research

You may be a better judge of this after reading the article, but the title should succinctly reflect the content of the work, stimulating readers' interest.

Three to six keywords that encapsulate the main topics of the research will have been drawn from the body of the article.

Introduction

This should include:

- Evidence of a literature review that is relevant and recent, critically appraising other works rather than merely describing them

- Background information on the study to orientate the reader to the problem

- Hypothesis or aims of the study

- Rationale for the study that justifies its need, i.e. to explore an un-investigated gap in the literature.

Materials and Methods

Similar to a recipe, the description of materials and methods will allow others to replicate the study elsewhere if needed. It should both contain and justify the exact specifications of selection criteria, sample size, response rate and any statistics used. This will demonstrate how the study is capable of achieving its aims. Things to consider in this section are:

- What sort of sampling technique and size was used?

- What proportion of the eligible sample participated? (e.g. '553 responded to a survey sent to 750 medical technologists'

- Were all eligible groups sampled? (e.g. was the survey sent only in English?)

- What were the strengths and weaknesses of the study?

- Were there threats to the reliability and validity of the study, and were these controlled for?

- Were there any obvious biases?

- If a trial was undertaken, was it randomised, case-controlled, blinded or double-blinded?

Results should be statistically analysed and presented in a way that an average reader of the journal will understand. Graphs and tables should be clear and promote clarity of the text. Consider whether:

- There were any major omissions in the results, which could indicate bias

- Percentages have been used to disguise small sample sizes

- The data generated is consistent with the data collected.

Negative results are just as relevant as research that produces positive results (but, as mentioned previously, may be omitted in publication due to editorial bias).

This should show insight into the meaning and significance of the research findings. It should not introduce any new material but should address how the aims of the study have been met. The discussion should use previous research work and theoretical concepts as the context in which the new study can be interpreted. Any limitations of the study, including bias, should be clearly presented. You will need to evaluate whether the author has clearly interpreted the results of the study, or whether the results could be interpreted another way.

Conclusions

These should be clearly stated and will only be valid if the study was reliable, valid and used a representative sample size. There may also be recommendations for further research.

These should be relevant to the study, be up-to-date, and should provide a comprehensive list of citations within the text.

Final Thoughts

Undertaking a critique of a research article may seem challenging at first, but will help you to evaluate whether the article has relevance to your own practice and workplace. Reading a single article can act as a springboard into researching the topic more widely, and aids in ensuring your nursing practice remains current and is supported by existing literature.

- Marshall, G 2005, ‘Critiquing a Research Article’, Radiography , vol. 11, no. 1, viewed 2 October 2023, https://www.radiographyonline.com/article/S1078-8174(04)00119-1/fulltext

Sarah Vogel View profile

Help and feedback, publications.

Ausmed Education is a Trusted Information Partner of Healthdirect Australia. Verify here .

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to content

- Home – AI for Research

The Ultimate Guide to Critiquing Research Articles

The ultimate guide to critiquing research articles. Learn how to evaluate validity and reliability, identify biases, and contribute to knowledge. Enhance your critique skills and join the intellectual adventure now!

Critiquing research articles is a fundamental skill for any scientist or researcher. It allows us to evaluate the validity and reliability of the findings, identify potential biases or limitations, and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in our respective fields. But why is critiquing research articles so important?

The Importance of Critiquing Research Articles

There are several reasons why critiquing research articles is crucial:

Ensuring Accuracy and Integrity: By critically analyzing the methods, results, and conclusions of a study, we can identify any flaws or inconsistencies that may undermine the credibility of the research. This helps maintain the high standards of scientific inquiry and prevents the dissemination of misleading or erroneous information.

Facilitating Scientific Progress: By identifying gaps in existing knowledge or weaknesses in previous studies, we can propose new research questions and design more robust experiments. This iterative process of critique and improvement is essential for advancing our understanding of the world and finding solutions to complex problems.

Nurturing a Culture of Intellectual Rigor: Critiquing research articles encourages researchers to question assumptions, challenge established theories, and explore alternative explanations. This fosters healthy debate, drives innovation, and pushes the boundaries of scientific inquiry.

In this blog post, we will delve deeper into the importance and relevance of critiquing research articles. We will explore effective strategies and provide valuable insights to help you enhance your critique skills. So, whether you’re a seasoned researcher or just starting your scientific journey, join us as we embark on this intellectual adventure of critiquing research articles.

Stay tuned for our next section, where we’ll discuss how to capture the reader’s attention with a clear hook.

Understanding Research Articles

Research articles are a fundamental component of the academic and scientific community. They serve as a means for researchers to communicate their findings, share knowledge, and contribute to the advancement of their respective fields. In this section, we will delve into the purpose and structure of research articles, as well as explore the different types of research articles that exist.

Purpose and Structure of Research Articles

The purpose of a research article is to present the results of a study or experiment in a clear and organized manner. These articles typically follow a specific structure, which allows readers to navigate through the information easily. Understanding this structure is crucial for researchers who want to effectively communicate their work.

The structure of a research article usually consists of several sections, each serving a specific purpose. The most common sections include:

- Introduction: Sets the stage for the research, providing background information and stating the research question or hypothesis. This section helps readers understand the context and significance of the study.

- Methods: Outlines the procedures and techniques used in the research, including the sample size, data collection methods, and statistical analyses. This section allows other researchers to replicate the study and verify the results.

- Results: Presents the findings of the research in a concise and objective manner. It often includes tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. This section should be focused on presenting the facts without interpretation or bias.

- Discussion: Analyzes and interprets the results of the study. Researchers may compare their findings to previous research, discuss limitations, and propose future directions. This section demonstrates their understanding of the implications of their work.

- Conclusion: Summarizes the main findings of the study and reiterates their significance. It may also include recommendations for further research or practical applications of the findings.

Different Types of Research Articles

Research articles can take various forms depending on the nature of the study and the intended audience. The three main types of research articles are:

- Empirical Research Articles: Present the results of original studies or experiments. These articles follow the structure we discussed earlier, with a focus on presenting data and analysis. They are the most common type in scientific and academic journals.

- Review Articles: Provide a comprehensive analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. They summarize the findings of multiple studies and offer a broader perspective on the subject. Review articles are valuable resources for researchers looking to gain a deeper understanding of a specific field or topic.

- Theoretical Research Articles: Focus on developing new theories or frameworks. They propose conceptual models, hypotheses, or theoretical explanations for phenomena. These articles are often found in disciplines such as philosophy, sociology, and psychology.

Research articles play a critical role in the dissemination of knowledge within the academic and scientific communities. Understanding the purpose and structure of these articles is essential for researchers to effectively communicate their findings. By following a clear and organized structure, researchers can ensure that their work is accessible and impactful to their peers and the broader scientific community.

Importance of Critiquing Research Articles

Critiquing research articles plays a vital role in the academic and research community. It not only benefits researchers and academics but also contributes to the overall advancement of knowledge. In this section, we will explore the benefits of critiquing research articles, how it improves critical thinking skills and enhances research abilities, and the importance of identifying strengths, weaknesses, and gaps in existing research.

Benefits of Critiquing Research Articles for Researchers and Academics

Critiquing research articles provides researchers and academics with several important benefits:

- Staying up-to-date: By critically analyzing existing research, researchers can identify gaps in the literature and areas that require further exploration. This helps them shape their own research questions and contribute to the existing body of knowledge.

- Improving research methodologies: By closely examining the methods and techniques used in published studies, researchers can gain insights into best practices and avoid potential pitfalls. This enhances the quality and rigor of their own research, leading to more accurate and reliable results.

- Fostering collaboration and intellectual discussion: By engaging in critical analysis and providing constructive feedback, researchers can contribute to the ongoing dialogue and debate surrounding a particular topic. This not only enriches the academic discourse but also promotes the refinement and advancement of ideas.

Improving Critical Thinking Skills and Enhancing Research Abilities through Critiquing

Critiquing research articles is an excellent way to develop and improve critical thinking skills. By evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of published studies, researchers are challenged to think critically and objectively. This process cultivates a critical mindset that is essential for conducting high-quality research.

Moreover, critiquing research articles enhances researchers’ research abilities. Through the analysis of existing research, researchers gain a deeper understanding of the methodologies and approaches that have been used successfully in the past. This knowledge can be applied to their own research, allowing them to make informed decisions and design studies that are more likely to yield meaningful results.

Identifying Strengths, Weaknesses, and Gaps in Existing Research

One of the key benefits of critiquing research articles is the ability to identify strengths, weaknesses, and gaps in existing research. By critically evaluating published studies, researchers can:

- Assess the strengths of the research design, the validity of the findings, and the relevance of the conclusions.

- Avoid repeating mistakes in their own work by recognizing limitations in methodology, sample size, or data analysis.

- Identify areas that have not been adequately explored or where conflicting results exist, providing opportunities for further research and the potential to make significant contributions to the field.

The Key Elements of Critiquing Research Articles

When critiquing research articles, it is important to consider several key elements. These elements can help you analyze and evaluate the quality and validity of the research. In this section, we will explore some of these key components and provide tips for effectively critiquing each one.

- The Abstract: The abstract is a concise summary of the entire research article, providing an overview of the study’s purpose, methodology, results, and conclusions. When critiquing the abstract, pay attention to whether it accurately reflects the content of the article and effectively conveys the main points. Look for clarity, coherence, and relevance in the abstract.

- The Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for the research by providing background information, stating the research problem, and outlining the objectives and hypotheses of the study. When evaluating the introduction, consider whether it effectively contextualizes the research and justifies its significance. Look for logical progression of ideas and clear articulation of the research question or problem.

- The Methodology: The methodology section describes the research design, sample size, data collection methods, and statistical analysis used in the study. This section is crucial for assessing the quality and rigor of the research. When critiquing the methodology, consider whether the chosen research design is appropriate for the research question and objectives. Evaluate the sample size and whether it is representative of the target population. Assess the data collection methods for reliability and validity. Finally, examine the statistical analysis to determine if it is appropriate and accurately reflects the data.

- The Results: The results section presents the findings of the study, often using tables, graphs, or statistical analyses. When evaluating the results, look for clarity and coherence in the presentation of the data. Consider whether the results are relevant to the research question and objectives. Assess the statistical significance of the findings and whether they support or contradict previous research in the field.

- The Discussion: The discussion section is where the researchers interpret the results, relate them to previous research, and discuss the implications of the findings. When critiquing the discussion, consider whether the interpretation of the results is supported by the data presented. Look for logical connections between the results and the research question. Assess whether the authors acknowledge any limitations of the study and suggest directions for future research.

- The References: The references section provides a list of the sources cited in the research article. When critiquing the references, consider whether they are relevant, reputable, and up-to-date. Look for a variety of sources to support the research claims and ensure that proper citation formats are used.

To effectively critique research articles, it is essential to analyze each component thoroughly and consider their individual strengths and weaknesses. By paying attention to the key elements, such as the abstract, introduction, methodology, results, discussion, and references, you can develop a comprehensive understanding of the research and evaluate its quality. Remember to use the tips provided in this section to guide your analysis and critique.

Enhance Your Research Skills with Avidnote

If you want to learn more about research article critique and other valuable insights for academics and researchers, be sure to check out the Avidnote Blog. It offers a wealth of information and tips to enhance your research writing, reading, and analysis processes. Additionally, Avidnote, an AI platform recommended by universities, provides features tailored for researchers, such as summarizing text, analyzing research data, and organizing reading lists. Don’t forget to explore the Avidnote Premium options, including a free plan for Karlstad Studentkår members. Start improving your research workflow with Avidnote today!

The Pitfalls of Critiquing Research Articles

In the world of research, critiquing research articles is an essential skill. It allows researchers to evaluate the quality and validity of published studies, identify potential biases, and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in their field. However, there are common pitfalls that researchers should avoid when critiquing research articles. Let’s explore some of these pitfalls and how to overcome them.

Failing to Understand the Study Design and Methodology

One common mistake researchers make when critiquing research articles is failing to fully understand the study design and methodology. It is crucial to have a thorough understanding of the research design, including the sampling methods, data collection procedures, and statistical analyses employed. Without this understanding, it becomes challenging to assess the study’s strengths and weaknesses accurately.

To overcome this pitfall, researchers can start by carefully reading the methods section of the article. This section provides details about the study’s design, participants, data collection instruments, and analysis methods. By familiarizing themselves with the study’s methodology, researchers can better evaluate its appropriateness for addressing the research question and drawing valid conclusions.

Biases in the Critique Process

Another common pitfall is the presence of biases in the critique process. Biases can manifest in various ways, such as personal beliefs, professional affiliations, or even unconscious biases. These biases can influence the interpretation of the research findings and compromise the objectivity of the critique.

To mitigate biases, researchers should strive to maintain objectivity and impartiality throughout the critique process. One way to achieve this is by critically evaluating the evidence presented in the research article and considering alternative explanations for the findings. It is also essential to be aware of one’s own biases and consciously challenge them to ensure a fair and balanced evaluation.

Emotional Reactions

Researchers should be cautious of their emotional reactions when critiquing research articles. It is natural to have preferences or opinions, but it is crucial to separate personal beliefs from the evaluation of the study’s scientific merit. By focusing on the evidence and logical reasoning, researchers can avoid being swayed by emotional biases and provide a more objective critique.

Maintaining objectivity also involves being open to different perspectives and interpretations. It is essential to consider the limitations of the study and acknowledge areas where further research is needed. Constructive criticism can contribute to the development of robust scientific knowledge, and researchers should approach the critique process with a mindset of continuous improvement.

Critiquing research articles is a valuable skill for researchers, but it is not without its pitfalls. To avoid these pitfalls, researchers should strive to understand the study design and methodology thoroughly, overcome biases, and maintain objectivity and impartiality throughout the critique process. By doing so, researchers can provide insightful and constructive critiques that contribute to the advancement of knowledge in their field. So, let’s continue honing our critiquing skills and fostering a culture of rigorous and objective research evaluation.

Tools and Resources to Aid in Critiquing Research Articles

When it comes to critiquing research articles, having the right tools and resources can make the process more efficient and effective. In this section, we will explore some helpful tools and online platforms that can assist you in your critique. Additionally, we will discuss Avidnote, an AI-powered platform specifically designed to enhance the research critique process.

Online Platforms, Software, and AI Tools for Effective Critiquing

The internet has opened up a world of possibilities for researchers, providing access to a wealth of information and resources. When it comes to critiquing research articles, there are several online platforms and software tools available that can streamline the process and help you uncover the strengths and weaknesses of a study.

One online platform worth mentioning is Avidnote . Designed with researchers in mind, Avidnote offers a range of AI-powered features that can enhance your research writing, reading, and analysis processes. With Avidnote, you can write research papers faster, summarize text, analyze research data, transcribe interviews, and more. It’s like having a virtual research assistant at your fingertips.

Avidnote is highly recommended by universities and offers AI functionalities specifically tailored for researchers. Whether you’re a student or a seasoned academic, Avidnote can help you save time and improve the quality of your critique. Plus, Avidnote offers different pricing plans to suit your needs, ranging from a free plan to professional and premium plans with additional AI usage, storage, and features.

One of the standout features of Avidnote is its commitment to data privacy. As a user, you own all the data you produce on the platform, and Avidnote ensures that your information is kept secure. This is particularly important when critiquing research articles, as you may be dealing with sensitive or confidential data.

In addition to its powerful AI capabilities, Avidnote also promotes ethical writing practices. The platform encourages users to use its features responsibly and provides valuable insights and tips for academics and researchers on its blog. Whether you’re looking for guidance on critiquing research articles or other aspects of the research process, Avidnote’s blog is a valuable resource.

Avidnote also offers features to help you organize your reading lists and prepare for critiques. With its seamless integration with reference management software, you can easily annotate and mark papers, store secure and searchable notes, and take quick notes on the go. The platform also allows you to work in groups and create shared projects, making collaboration with colleagues a breeze.

If you’re a member of Karlstad Studentkår, you’ll be pleased to know that you can access Avidnote Premium for free by registering with the code KAU. This is a fantastic opportunity to take advantage of Avidnote’s premium features without breaking the bank. Additionally, PhD students who are members of the student association can also access Avidnote for free, further demonstrating the platform’s commitment to supporting academic research.

When it comes to critiquing research articles, having the right tools and resources can make all the difference. Online platforms, software tools, and AI-powered platforms like Avidnote can streamline the critique process, saving you time and improving the quality of your analysis. With its range of features tailored for researchers, Avidnote is a valuable tool that can enhance your research writing, reading, and analysis processes. So why not give it a try and see how it can transform your critique?

The Importance of Constructive Feedback in Research

In the research community, providing constructive feedback on research articles plays a crucial role in promoting growth and improvement. Constructive feedback not only helps researchers refine their work but also contributes to the overall advancement of knowledge in their field.

Constructive feedback is invaluable in the research community because it allows researchers to identify areas for improvement and refine their work. By offering insights and suggestions, reviewers can help authors strengthen their arguments, enhance the clarity of their writing, and address any potential weaknesses. This collaborative process fosters a culture of continuous improvement and drives the advancement of research.

Guidelines for Offering Helpful and Respectful Feedback

When providing feedback, it is essential to follow guidelines that ensure the feedback is helpful, respectful, and constructive. One important guideline is to focus on the content rather than the person behind it. By separating the work from the individual, feedback can be given in a way that is less personal and more objective. This approach helps maintain a positive and supportive environment for researchers.

Another guideline is to be specific and provide concrete examples. Vague statements like “this section needs improvement” are not helpful. Instead, pointing out specific areas that could benefit from clarification or providing alternative approaches can guide authors in making meaningful revisions. Additionally, offering examples or referring to relevant research can strengthen the feedback and provide authors with a clearer understanding of how to improve their work.

It is also important to be respectful and considerate when giving feedback. Recognize the effort and time that went into the research and acknowledge the strengths of the work. By starting with positive feedback, reviewers can create a more receptive atmosphere and help authors feel encouraged to make necessary revisions. Additionally, using a constructive and supportive tone throughout the feedback can help foster a collaborative relationship between reviewers and authors.

The Role of Feedback in Research Development

Feedback plays a crucial role in promoting growth and improvement in research. It helps researchers identify blind spots and encourages them to explore different perspectives. By engaging in a constructive dialogue, researchers can refine their ideas, challenge assumptions, and broaden the impact of their work. Constructive feedback also contributes to the overall quality of research publications, ensuring that they meet the rigorous standards of the scientific community.

Research is a dynamic and evolving process, and feedback is a key component in driving progress. By offering constructive feedback, researchers contribute to the continuous development of their field and help elevate the quality of research outcomes. It is through this collaborative effort that researchers can collectively push the boundaries of knowledge and make meaningful contributions to their respective disciplines.

In Conclusion

Providing constructive feedback on research articles is crucial for the growth and improvement of the research community. By adhering to guidelines that promote helpful, respectful, and constructive feedback, researchers can actively contribute to the advancement of their field. The feedback process fosters a culture of continuous improvement, encourages collaboration, and drives the overall progress of research. So, let us embrace the power of constructive feedback and work together to push the boundaries of knowledge.

Why Critiquing Research Articles is Crucial

Critiquing research articles is a crucial skill for researchers to develop for their personal and professional growth. It allows them to:

Evaluate the quality and validity of research

Identify gaps in knowledge

Contribute to the advancement of their field

Avidnote: Enhancing Research Processes

Avidnote is an AI platform designed for researchers that offers a range of features to enhance the research writing, reading, and analysis processes. With Avidnote, researchers can:

Write research papers faster

Summarize text

Analyze research data

Transcribe interviews

Avidnote provides researchers with the tools they need to streamline their work. It has recommendations from universities and offers a range of pricing plans to cater to researchers at every level. The platform ensures data privacy and promotes ethical writing practices.

Avidnote Blog: Valuable Resource for Researchers

The Avidnote blog is a valuable resource for academics and researchers. It provides insights and tips on various topics, including critiquing research articles. Avidnote also offers features to help users organize their reading lists and prepare for critiques, making the process more efficient and effective.

Avidnote’s Integration with OpenAI

Avidnote integrates with OpenAI’s private beta, staying at the forefront of research and academic work. This integration offers cutting-edge tools for users.

Members of Karlstad Studentkår can even access Avidnote Premium for free by registering with the code KAU. This further enhances their research capabilities.

Avidnote: Simplifying the Research Process

Avidnote is the ultimate companion for researchers, providing them with the necessary tools and resources to excel in their work. Whether it’s writing, organizing studies, or collaborating with others, Avidnote simplifies the research process and allows researchers to focus on making impactful contributions to their field. Try it out by clicking here .

Remember, your research has the power to shape the future. Let Avidnote be your ally on this journey.

You may also like

Ambio: A Comprehensive Resource for Environmental Research

Ambio: A comprehensive resource for environmental research. Explore a wealth of knowledge on the human-environment relationship and gain insights to shape our planet’s future. Join us today!

How to Enhance Productivity in Academia

Enhance productivity in academia with time management and efficiency strategies. Achieve academic goals by optimizing your workflow and finding a balance between work and self-care. Boost your productivity now!

Privacy Overview

Adding {{itemName}} to cart

Added {{itemName}} to cart

SPH Writing Support Services

- Appointment System

- ESL Conversation Group

- Mini-Courses

- Thesis/Dissertation Writing Group

- Career Writing

- Citing Sources

- Critiquing Research Articles

- Project Planning for the Beginner This link opens in a new window

- Grant Writing

- Publishing in the Sciences

- Systematic Review Overview

- Systematic Review Resources This link opens in a new window

- Writing Across Borders / Writing Across the Curriculum

- Conducting an article critique for a quantitative research study: Perspectives for doctoral students and other novice readers (Vance et al.)

- Critique Process (Boswell & Cannon)

- The experience of critiquing published research: Learning from the student and researcher perspective (Knowles & Gray)

- A guide to critiquing a research paper. Methodological appraisal of a paper on nurses in abortion care (Lipp & Fothergill)

- Step-by-step guide to critiquing research. Part 1: Quantitative research (Coughlan et al.)

- Step-by-step guide to critiquing research. Part 2: Qualitative research (Coughlan et al.)

Guidelines:

- Critiquing Research Articles (Flinders University)

- Framework for How to Read and Critique a Research Study (American Nurses Association)

- How to Critique a Journal Article (UIS)

- How to Critique a Research Paper (University of Michigan)

- How to Write an Article Critique

- Research Article Critique Form

- Writing a Critique or Review of a Research Article (University of Calgary)

Presentations:

- The Critique Process: Reviewing and Critiquing Research

- Writing a Critique

- << Previous: Citing Sources

- Next: Project Planning for the Beginner >>

- Last Updated: Apr 5, 2024 9:39 AM

- URL: https://libguides.sph.uth.tmc.edu/writing_support_services

IOE Writing Centre

- Writing a Critical Review

Writing a Critique

A critique (or critical review) is not to be mistaken for a literature review. A 'critical review', or 'critique', is a complete type of text (or genre), discussing one particular article or book in detail. In some instances, you may be asked to write a critique of two or three articles (e.g. a comparative critical review). In contrast, a 'literature review', which also needs to be 'critical', is a part of a larger type of text, such as a chapter of your dissertation.

Most importantly: Read your article / book as many times as possible, as this will make the critical review much easier.

1. Read and take notes 2. Organising your writing 3. Summary 4. Evaluation 5. Linguistic features of a critical review 6. Summary language 7. Evaluation language 8. Conclusion language 9. Example extracts from a critical review 10. Further resources

Read and Take Notes

To improve your reading confidence and efficiency, visit our pages on reading.

Further reading: Read Confidently

After you are familiar with the text, make notes on some of the following questions. Choose the questions which seem suitable:

- What kind of article is it (for example does it present data or does it present purely theoretical arguments)?

- What is the main area under discussion?

- What are the main findings?

- What are the stated limitations?

- Where does the author's data and evidence come from? Are they appropriate / sufficient?

- What are the main issues raised by the author?

- What questions are raised?

- How well are these questions addressed?

- What are the major points/interpretations made by the author in terms of the issues raised?

- Is the text balanced? Is it fair / biased?

- Does the author contradict herself?

- How does all this relate to other literature on this topic?

- How does all this relate to your own experience, ideas and views?

- What else has this author written? Do these build / complement this text?

- (Optional) Has anyone else reviewed this article? What did they say? Do I agree with them?

^ Back to top

Organising your writing

You first need to summarise the text that you have read. One reason to summarise the text is that the reader may not have read the text. In your summary, you will

- focus on points within the article that you think are interesting

- summarise the author(s) main ideas or argument

- explain how these ideas / argument have been constructed. (For example, is the author basing her arguments on data that they have collected? Are the main ideas / argument purely theoretical?)

In your summary you might answer the following questions: Why is this topic important? Where can this text be located? For example, does it address policy studies? What other prominent authors also write about this?

Evaluation is the most important part in a critical review.

Use the literature to support your views. You may also use your knowledge of conducting research, and your own experience. Evaluation can be explicit or implicit.

Explicit evaluation

Explicit evaluation involves stating directly (explicitly) how you intend to evaluate the text. e.g. "I will review this article by focusing on the following questions. First, I will examine the extent to which the authors contribute to current thought on Second Language Acquisition (SLA) pedagogy. After that, I will analyse whether the authors' propositions are feasible within overseas SLA classrooms."

Implicit evaluation

Implicit evaluation is less direct. The following section on Linguistic Features of Writing a Critical Review contains language that evaluates the text. A difficult part of evaluation of a published text (and a professional author) is how to do this as a student. There is nothing wrong with making your position as a student explicit and incorporating it into your evaluation. Examples of how you might do this can be found in the section on Linguistic Features of Writing a Critical Review. You need to remember to locate and analyse the author's argument when you are writing your critical review. For example, you need to locate the authors' view of classroom pedagogy as presented in the book / article and not present a critique of views of classroom pedagogy in general.

Linguistic features of a critical review

The following examples come from published critical reviews. Some of them have been adapted for student use.

Summary language

- This article / book is divided into two / three parts. First...

- While the title might suggest...

- The tone appears to be...

- Title is the first / second volume in the series Title, edited by...The books / articles in this series address...

- The second / third claim is based on...

- The author challenges the notion that...

- The author tries to find a more middle ground / make more modest claims...

- The article / book begins with a short historical overview of...

- Numerous authors have recently suggested that...(see Author, Year; Author, Year). Author would also be once such author. With his / her argument that...

- To refer to title as a...is not to say that it is...

- This book / article is aimed at... This intended readership...

- The author's book / article examines the...To do this, the author first...

- The author develops / suggests a theoretical / pedagogical model to…

- This book / article positions itself firmly within the field of...

- The author in a series of subtle arguments, indicates that he / she...

- The argument is therefore...

- The author asks "..."

- With a purely critical / postmodern take on...

- Topic, as the author points out, can be viewed as...

- In this recent contribution to the field of...this British author...

- As a leading author in the field of...

- This book / article nicely contributes to the field of...and complements other work by this author...

- The second / third part of...provides / questions / asks the reader...

- Title is intended to encourage students / researchers to...

- The approach taken by the author provides the opportunity to examine...in a qualitative / quantitative research framework that nicely complements...

- The author notes / claims that state support / a focus on pedagogy / the adoption of...remains vital if...

- According to Author (Year) teaching towards examinations is not as effective as it is in other areas of the curriculum. This is because, as Author (Year) claims that examinations have undue status within the curriculum.

- According to Author (Year)…is not as effective in some areas of the curriculum / syllabus as others. Therefore the author believes that this is a reason for some school's…

Evaluation language

- This argument is not entirely convincing, as...furthermore it commodifies / rationalises the...

- Over the last five / ten years the view of...has increasingly been viewed as 'complicated' (see Author, Year; Author, Year).

- However, through trying to integrate...with...the author...

- There are difficulties with such a position.

- Inevitably, several crucial questions are left unanswered / glossed over by this insightful / timely / interesting / stimulating book / article. Why should...

- It might have been more relevant for the author to have written this book / article as...

- This article / book is not without disappointment from those who would view...as...

- This chosen framework enlightens / clouds...

- This analysis intends to be...but falls a little short as...

- The authors rightly conclude that if...

- A detailed, well-written and rigorous account of...

- As a Korean student I feel that this article / book very clearly illustrates...

- The beginning of...provides an informative overview into...

- The tables / figures do little to help / greatly help the reader...

- The reaction by scholars who take a...approach might not be so favourable (e.g. Author, Year).

- This explanation has a few weaknesses that other researchers have pointed out (see Author, Year; Author, Year). The first is...

- On the other hand, the author wisely suggests / proposes that...By combining these two dimensions...

- The author's brief introduction to...may leave the intended reader confused as it fails to properly...

- Despite my inability to...I was greatly interested in...

- Even where this reader / I disagree(s), the author's effort to...

- The author thus combines...with...to argue...which seems quite improbable for a number of reasons. First...

- Perhaps this aversion to...would explain the author's reluctance to...

- As a second language student from ...I find it slightly ironic that such an anglo-centric view is...

- The reader is rewarded with...

- Less convincing is the broad-sweeping generalisation that...