Analyze your market like a pro with this step-by-step guide + insider tips

Don’t fall into the trap of assuming that you already know enough about your market.

No matter how fantastic your product or service is, your business cannot succeed without sufficient market demand .

You need a clear understanding of who will buy your product or service and why .

You want to know if there is a clear market gap and a market large enough to support the survival and growth of your business.

Industry research and market analysis will help make sure that you are on the right track .

It takes time , but it is time well spent . Thank me later.

WHAT is Market Analysis?

The Market Analysis section of a business plan is also sometimes called:

- Market Demand, Market Trends, Target Market, The Market

- Industry Analysis & Trends, Industry & Market Analysis, Industry and Market Research

WHY Should You Do Market Analysis?

First and foremost, you need to demonstrate beyond any reasonable doubt that there is real need and sufficient demand for your product or service in the market, now and going forward.

- What makes you think that people will buy your products or services?

- Can you prove it?

Your due diligence on the market opportunity and validating the problem and solution described in the Product and Service section of your business plan are crucial for the success of your venture.

Also, no company operates in a vacuum. Every business is part of a larger overall industry, the forces that affect your industry as a whole will inevitably affect your business as well.

Evaluating your industry and market increases your own knowledge of the factors that contribute to your company’s success and shows the readers of your business plan that you understand the external business conditions.

External Support

In fact, if you are seeking outside financing, potential backers will most definitely be interested in industry and market conditions and trends.

You will make a positive impression and have a better chance of getting their support if you show market analysis that strengthens your business case, combining relevant and reliable data with sound judgement.

Let’s break down how to do exactly that, step by step:

HOW To Do Market Analysis: Step-by-Step

So, let’s break up how market analysis is done into three steps:

- Industry: the total market

- Target Market: specific segments of the industry that you will target

- Target Customer: characteristics of the customers that you will focus on

Step 1: Industry Analysis

How do you define an industry.

For example, the fashion industry includes fabric suppliers, designers, companies making finished clothing, distributors, sales representatives, trade publications, retail outlets online and on the high street.

How Do You Analyze an Industry?

Briefly describe your industry, including the following considerations:

1.1. Economic Conditions

Outline the current and projected economic conditions that influence the industry your business operates in, such as:

- Official economic indicators like GDP or inflation

- Labour market statistics

- Foreign trade (e.g., import and export statistics)

1.2. Industry Description

Highlight the distinct characteristic of your industry, including:

- Market leaders , major customer groups and customer loyalty

- Supply chain and distribution channels

- Profitability (e.g., pricing, cost structure, margins), financials

- Key success factors

- Barriers to entry preventing new companies from competing in the industry

1.3. Industry Size and Growth

Estimate the size of your industry and analyze how industry growth affects your company’s prospects:

- Current size (e.g., revenues, units sold, employment)

- Historic and projected industry growth rate (low/medium/high)

- Life-cycle stage /maturity (emerging/expanding/ mature/declining)

1.4. Industry Trends

- Industry Trends: Describe the key industry trends and evaluate the potential impact of PESTEL (political / economic / social / technological / environmental / legal) changes on the industry, including the level of sensitivity to:

- Seasonality

- Economic cycles

- Government regulation (e.g. environment, health and safety, international trade, performance standards, licensing/certification/fair trade/deregulation, product claims) Technological change

- Global Trends: Outline global trends affecting your industry

- Identify global industry concerns and opportunities

- International markets that could help to grow your business

- Strategic Opportunity: Highlight the strategic opportunities that exist in your industry

Step 2: Target Customer Identification

Who is a target customer.

One business can have–and often does have–more than one target customer group.

The success of your business depends on your ability to meet the needs and wants of your customers. So, in a business plan, your aim is to assure readers that:

- Your customers actually exist

- You know exactly who they are and what they want

- They are ready for what you have to offer and are likely to actually buy

How Do You Identify an Ideal Target Customer?

2.1. target customer.

- Identify the customer, remembering that the decision-maker who makes the purchase can be a different person or entity than the end-user.

2.2. Demographics

- For consumers ( demographics ): Age, gender, income, occupation, education, family status, home ownership, lifestyle (e.g., work and leisure activities)

- For businesses ( firmographic ): Industry, sector, years in business, ownership, size (e.g., sales, revenues, budget, employees, branches, sq footage)

2.3. Geographic Location

- Where are your customers based, where do they buy their products/services and where do they actually use them

2.4 Purchasing Patterns

- Identify customer behaviors, i.e., what actions they take

- how frequently

- and how quickly they buy

2.5. Psychographics

- Identify customer attitudes, i.e., how they think or feel

- Urgency, price, quality, reputation, image, convenience, availability, features, brand, customer service, return policy, sustainability, eco-friendliness, supporting local business

- Necessity/luxury, high involvement bit ticket item / low involvement consumable

Step 3: Target Market Analysis

What is a target market.

Target market, or 'target audience', is a group of people that a business has identified as the most likely to purchase its offering, defined by demographic, psychographic, geographic and other characteristics. Target market may be broken down to target customers to customize marketing efforts.

How Do You Analyze a Target Market?

So, how many people are likely to become your customers?

To get an answer to this questions, narrow the industry into your target market with a manageable size, and identify its key characteristics, size and trends:

3.1. Target Market Description

Define your target market by:

- Type: B2C, B2B, government, non-profits

- Geographic reach: Specify the geographic location and reach of your target market

3.2. Market Size and Share

Estimate how large is the market for your product or service (e.g., number of customers, annual purchases in sales units and $ revenues). Explain the logic behind your calculation:

- TAM (Total Available/Addressable/Attainable Market) is the total maximum demand for a product or service that could theoretically be generated by selling to everyone in the world who could possibly buy from you, regardless of competition and any other considerations and restrictions.

- SAM (Serviceable Available Market) is the portion of the TAM that you could potentially address in a specific market. For example, if your product/service is only available in one country or language.

- SOM (Service Obtainable Market / Share of Market) is the share of the SAM that you can realistically carve out for your product or service. This the target market that you will be going after and can reasonably expect to convert into a customer base.

3.3. Market Trends

Illustrate the most important themes, changes and developments happening in your market. Explain the reasons behind these trends and how they will favor your business.

3.4. Demand Growth Opportunity

Estimate future demand for your offering by translating past, current and future market demand trends and drivers into forecasts:

- Historic growth: Check how your target market has grown in the past.

- Drivers past: Identify what has been driving that growth in the past.

- Drivers future: Assess whether there will be any change in influence of these and other drivers in the future.

How Big Should My Target Market Be?

Well, if the market opportunity is small, it will limit how big and successful your business can become. In fact, it may even be too small to support a successful business at all.

On the other hand, many businesses make the mistake of trying to appeal to too many target markets, which also limits their success by distracting their focus.

What If My Stats Look Bad?

Large and growing market suggests promising demand for your offering now and into the future. Nevertheless, your business can still thrive in a smaller or contracting market.

Instead of hiding from unfavorable stats, acknowledge that you are swimming against the tide and devise strategies to cope with whatever lies ahead.

Step 4: Industry and Market Analysis Research

The market analysis section of your business plan should illustrate your own industry and market knowledge as well as the key findings and conclusions from your research.

Back up your findings with external research sources (= secondary research) and results of internal market research and testing (= primary research).

What is Primary and Secondary Market Research?

Yes, there are two main types of market research – primary and secondary – and you should do both to adequately cover the market analysis section of your business plan:

- Primary market research is original data you gather yourself, for example in the form of active fieldwork collecting specific information in your market.

- Secondary market research involves collating information from existing data, which has been researched and shared by reliable outside sources . This is essentially passive desk research of information already published .

Unless you are working for a corporation, this exercise is not about your ability to do professional-level market research.

Instead, you just need to demonstrate fundamental understanding of your business environment and where you fit in within the market and broader industry.

Why Do You Need To Do Primary & Secondary Market Research?

There are countless ways you could go collecting industry and market research data, depending on the type of your business, what your business plan is for, and what your needs, resources and circumstances are.

For tried and tested tips on how to properly conduct your market research, read the next section of this guide that is dedicated to primary and secondary market research methods.

In any case, tell the reader how you carried out your market research. Prove what the facts are and where you got your data. Be as specific as possible. Provide statistics, numbers, and sources.

When doing secondary research, always make sure that all stats, facts and figures are from reputable sources and properly referenced in both the main text and the Appendix of your business plan. This gives more credibility to your business case as the reader has more confidence in the information provided.

Go to the Primary and Secondary Market Research post for my best tips on industry, market and competitor research.

7 TOP TIPS For Writing Market Analysis

1. realistic projections.

Above all, make sure that you are realistic in your projections about how your product or service is going to be accepted in the market, otherwise you are going to seriously undermine the credibility of your entire business case.

2. Laser Focus

Discuss only characteristic of your target market and customers that are observable, factual and meaningful, i.e. directly relate to your customers’ decision to purchase.

Always relate the data back to your business. Market statistics are meaningless until you explain where and how your company fits in.

For example, as you write about the market gap and the needs of your target customers, highlight how you are uniquely positioned to fill them.

In other words, your goal is to:

- Present your data

- Analyze the data

- Tie the data back to how your business can thrive within your target market

3. Target Audience

On a similar note, tailor the market analysis to your target audience and the specific purpose at hand.

For example, if your business plan is for internal use, you may not have to go into as much detail about the market as you would have for external financiers, since your team is likely already very familiar with the business environment your company operates in.

4. Story Time

Make sure that there is a compelling storyline and logical flow to the market information presented.

The saying “a picture is worth a thousand words” certainly applies here. Industry and market statistics are easier to understand and more impactful if presented as a chart or graph.

6. Information Overload

Keep your market analysis concise by only including pertinent information. No fluff, no repetition, no drowning the reader in a sea of redundant facts.

While you should not assume that the reader knows anything about your market, do not elaborate on unnecessary basic facts either.

Do not overload the reader in the main body of the business plan. Move everything that is not essential to telling the story into the Appendix. For example, summarize the results of market testing survey in the main body of the business plan document, but move the list of the actual survey questions into the appendix.

7. Marketing Plan

Note that market analysis and marketing plan are two different things, with two distinct chapters in a business plan.

As the name suggests, market analysis examines where you fit in within your desired industry and market. As you work thorugh this section, jot down your ideas for the marketing and strategy section of your business plan.

Final Thoughts

Remember that the very act of doing the research and analysis is a great opportunity to learn things that affect your business that you did not know before, so take your time doing the work.

Related Questions

What is the purpose of industry & market research and analysis.

The purpose of industry and market research and analysis is to qualitatively and quantitatively assess the environment of a business and to confirm that the market opportunity is sufficient for sustainable success of that business.

Why are Industry & Market Research and Analysis IMPORTANT?

Industry and market research and analysis are important because they allow you to gain knowledge of the industry, the target market you are planning to sell to, and your competition, so you can make informed strategic decisions on how to make your business succeed.

How Can Industry & Market Research and Analysis BENEFIT a Business?

Industry and market research and analysis benefit a business by uncovering opportunities and threats within its environment, including attainable market size, ideal target customers, competition and any potential difficulties on the company’s journey to success.

Sign up for our Newsletter

Get more articles just like this straight into your mailbox.

Related Posts

Recent Posts

How to Conduct an Industry Analysis? Steps, Template, Examples

Appinio Research · 16.11.2023 · 39min read

Are you ready to unlock the secrets of Industry Analysis, equipping yourself with the knowledge to navigate markets and make informed strategic decisions? Dive into this guide, where we unravel the significance, objectives, and methods of Industry Analysis.

Whether you're an entrepreneur seeking growth opportunities or a seasoned executive navigating industry shifts, this guide will be your compass in understanding the ever-evolving business terrain.

What is Industry Analysis?

Industry analysis is the process of examining and evaluating the dynamics, trends, and competitive forces within a specific industry or market sector. It involves a comprehensive assessment of the factors that impact the performance and prospects of businesses operating within that industry. Industry analysis serves as a vital tool for businesses and decision-makers to gain a deep understanding of the environment in which they operate.

Key components of industry analysis include:

- Market Size and Growth: Determining the overall size of the market, including factors such as revenue, sales volume, and customer base. Analyzing historical and projected growth rates provides insights into market trends and opportunities.

- Competitive Landscape: Identifying and analyzing competitors within the industry. This includes assessing their market share, strengths, weaknesses, and strategies. Understanding the competitive landscape helps businesses position themselves effectively.

- Customer Behavior and Preferences: Examining consumer behavior , preferences, and purchasing patterns within the industry. This information aids in tailoring products or services to meet customer needs.

- Regulatory and Legal Environment: Assessing the impact of government regulations, policies, and legal requirements on industry operations. Compliance and adaptation to these factors are crucial for business success.

- Technological Trends: Exploring technological advancements and innovations that affect the industry. Staying up-to-date with technology trends can be essential for competitiveness and growth.

- Economic Factors: Considering economic conditions, such as inflation rates, interest rates, and economic cycles, that influence the industry's performance.

- Social and Cultural Trends: Examining societal and cultural shifts, including changing consumer values and lifestyle trends that can impact demand and preferences.

- Environmental and Sustainability Factors: Evaluating environmental concerns and sustainability issues that affect the industry. Industries are increasingly required to address environmental responsibility.

- Supplier and Distribution Networks: Analyzing the availability of suppliers, distribution channels, and supply chain complexities within the industry.

- Risk Factors: Identifying potential risks and uncertainties that could affect industry stability and profitability.

Objectives of Industry Analysis

Industry analysis serves several critical objectives for businesses and decision-makers:

- Understanding Market Dynamics: The primary objective is to gain a comprehensive understanding of the industry's dynamics, including its size, growth prospects, and competitive landscape. This knowledge forms the basis for strategic planning.

- Identifying Growth Opportunities: Industry analysis helps identify growth opportunities within the market. This includes recognizing emerging trends, niche markets, and underserved customer segments.

- Assessing Competitor Strategies: By examining competitors' strengths, weaknesses, and strategies, businesses can formulate effective competitive strategies. This involves positioning the company to capitalize on its strengths and exploit competitors' weaknesses.

- Risk Assessment and Mitigation: Identifying potential risks and vulnerabilities specific to the industry allows businesses to develop risk mitigation strategies and contingency plans. This proactive approach minimizes the impact of adverse events.

- Strategic Decision-Making: Industry analysis provides the data and insights necessary for informed strategic decision-making. It guides decisions related to market entry, product development, pricing strategies, and resource allocation.

- Resource Allocation: By understanding industry dynamics, businesses can allocate resources efficiently. This includes optimizing marketing budgets, supply chain investments, and talent recruitment efforts.

- Innovation and Adaptation: Staying updated on technological trends and shifts in customer preferences enables businesses to innovate and adapt their offerings effectively.

Importance of Industry Analysis in Business

Industry analysis holds immense importance in the business world for several reasons:

- Strategic Planning: It forms the foundation for strategic planning by providing a comprehensive view of the industry's landscape. Businesses can align their goals, objectives, and strategies with industry trends and opportunities.

- Risk Management: Identifying and assessing industry-specific risks allows businesses to manage and mitigate potential threats proactively. This reduces the likelihood of unexpected disruptions.

- Competitive Advantage: In-depth industry analysis helps businesses identify opportunities for gaining a competitive advantage. This could involve product differentiation, cost leadership, or niche market targeting .

- Resource Optimization: Efficient allocation of resources, both financial and human, is possible when businesses have a clear understanding of industry dynamics. It prevents wastage and enhances resource utilization.

- Informed Investment: Industry analysis assists investors in making informed decisions about allocating capital. It provides insights into the growth potential and risk profiles of specific industry sectors.

- Adaptation to Change: As industries evolve, businesses must adapt to changing market conditions. Industry analysis facilitates timely adaptation to new technologies, market shifts, and consumer preferences .

- Market Entry and Expansion: For businesses looking to enter new markets or expand existing operations, industry analysis guides decision-making by evaluating the feasibility and opportunities in target markets.

- Regulatory Compliance: Understanding the regulatory environment is critical for compliance and risk avoidance. Industry analysis helps businesses stay compliant with relevant laws and regulations.

In summary, industry analysis is a fundamental process that empowers businesses to make informed decisions, stay competitive, and navigate the complexities of their respective markets. It is an invaluable tool for strategic planning and long-term success.

How to Prepare for Industry Analysis?

Let's start by going through the crucial preparatory steps for conducting a comprehensive industry analysis.

1. Data Collection and Research

- Primary Research: When embarking on an industry analysis, consider conducting primary research . This involves gathering data directly from industry sources, stakeholders, and potential customers. Methods may include surveys , interviews, focus groups , and observations. Primary research provides firsthand insights and can help validate secondary research findings.

- Secondary Research: Secondary research involves analyzing existing literature, reports, and publications related to your industry. Sources may include academic journals, industry-specific magazines, government publications, and market research reports. Secondary research provides a foundation of knowledge and can help identify gaps in information that require further investigation.

- Data Sources: Explore various data sources to collect valuable industry information. These sources may include industry-specific associations, government agencies, trade publications, and reputable market research firms. Make sure to cross-reference data from multiple sources to ensure accuracy and reliability.

2. Identifying Relevant Industry Metrics

Understanding and identifying the right industry metrics is essential for meaningful analysis. Here, we'll discuss key metrics that can provide valuable insights:

- Market Size: Determining the market's size, whether in terms of revenue, units sold, or customer base, is a fundamental metric. It offers a snapshot of the industry's scale and potential.

- Market Growth Rate: Assessing historical and projected growth rates is crucial for identifying trends and opportunities. Understanding how the market has evolved over time can guide strategic decisions.

- Market Share Analysis: Analyzing market share among industry players can help you identify dominant competitors and their respective positions. This metric also assists in gauging your own company's market presence.

- Market Segmentation : Segmenting the market based on demographics, geography, behavior, or other criteria can provide deeper insights. Understanding the specific needs and preferences of various market segments can inform targeted strategies.

3. Gathering Competitive Intelligence

Competitive intelligence is the cornerstone of effective industry analysis. To gather and utilize information about your competitors:

- Competitor Identification: Begin by creating a comprehensive list of your primary and potential competitors. Consider businesses that offer similar products or services within your target market. It's essential to cast a wide net to capture all relevant competitors.

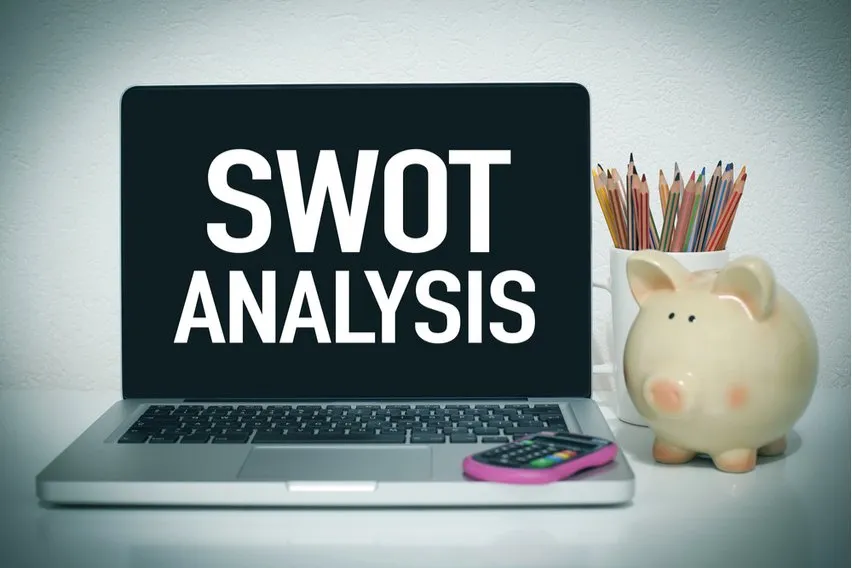

- SWOT Analysis : Conduct a thorough SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis for each competitor. This analysis helps you identify their internal strengths and weaknesses, as well as external opportunities and threats they face.

- Market Share Analysis: Determine the market share held by each competitor and how it has evolved over time. Analyzing changes in market share can reveal shifts in competitive dynamics.

- Product and Pricing Analysis: Evaluate your competitors' product offerings and pricing strategies . Identify any unique features or innovations they offer and consider how your own products or services compare.

- Marketing and Branding Strategies: Examine the marketing and branding strategies employed by competitors. This includes their messaging, advertising channels, and customer engagement tactics. Assess how your marketing efforts stack up.

Industry Analysis Frameworks and Models

Now, let's explore essential frameworks and models commonly used in industry analysis, providing you with practical insights and examples to help you effectively apply these tools.

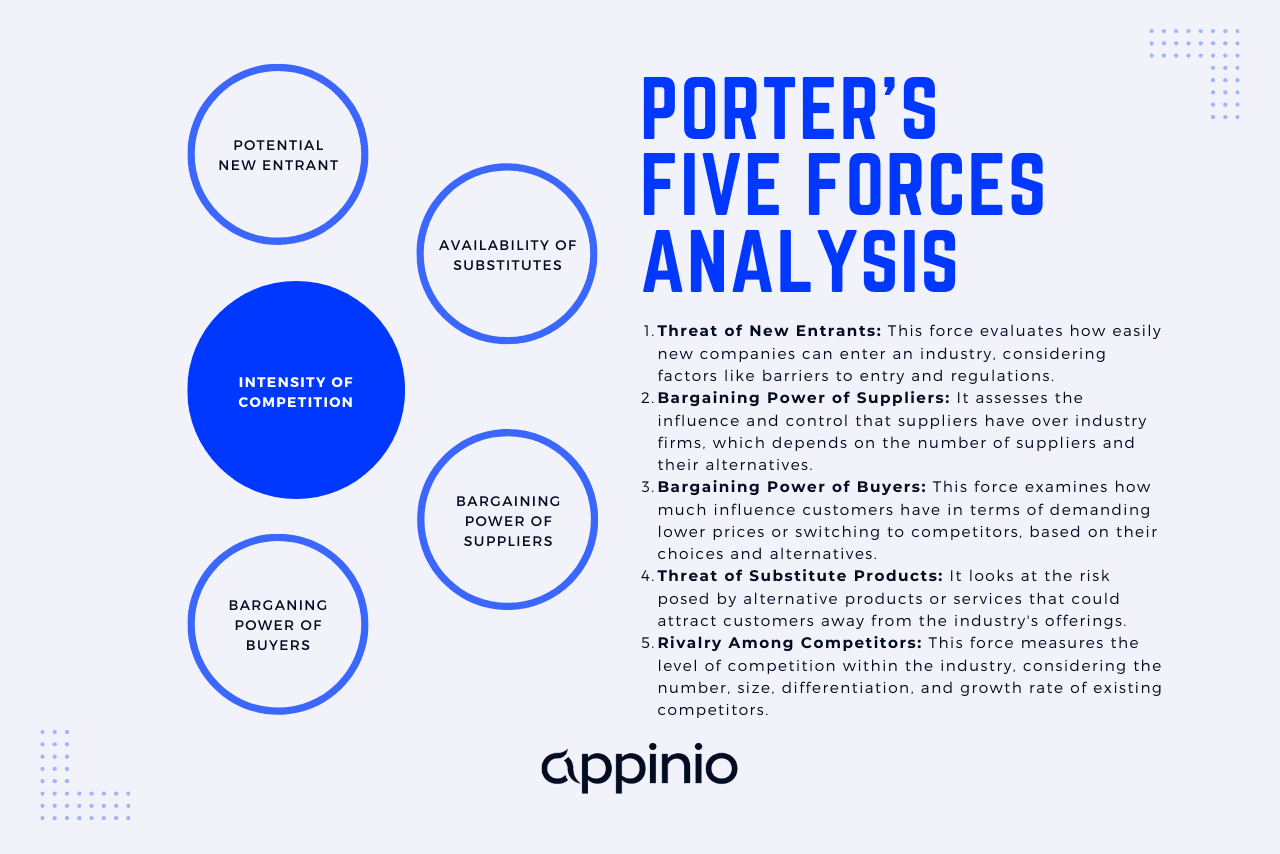

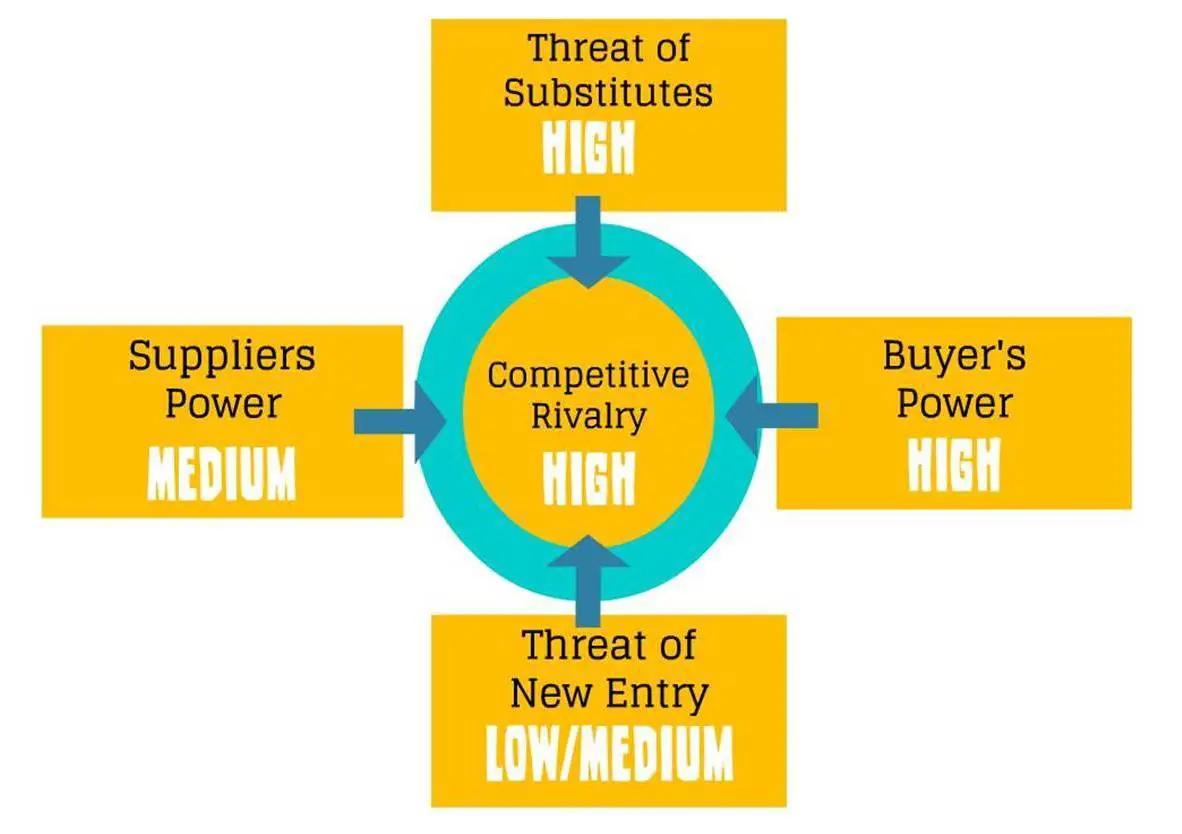

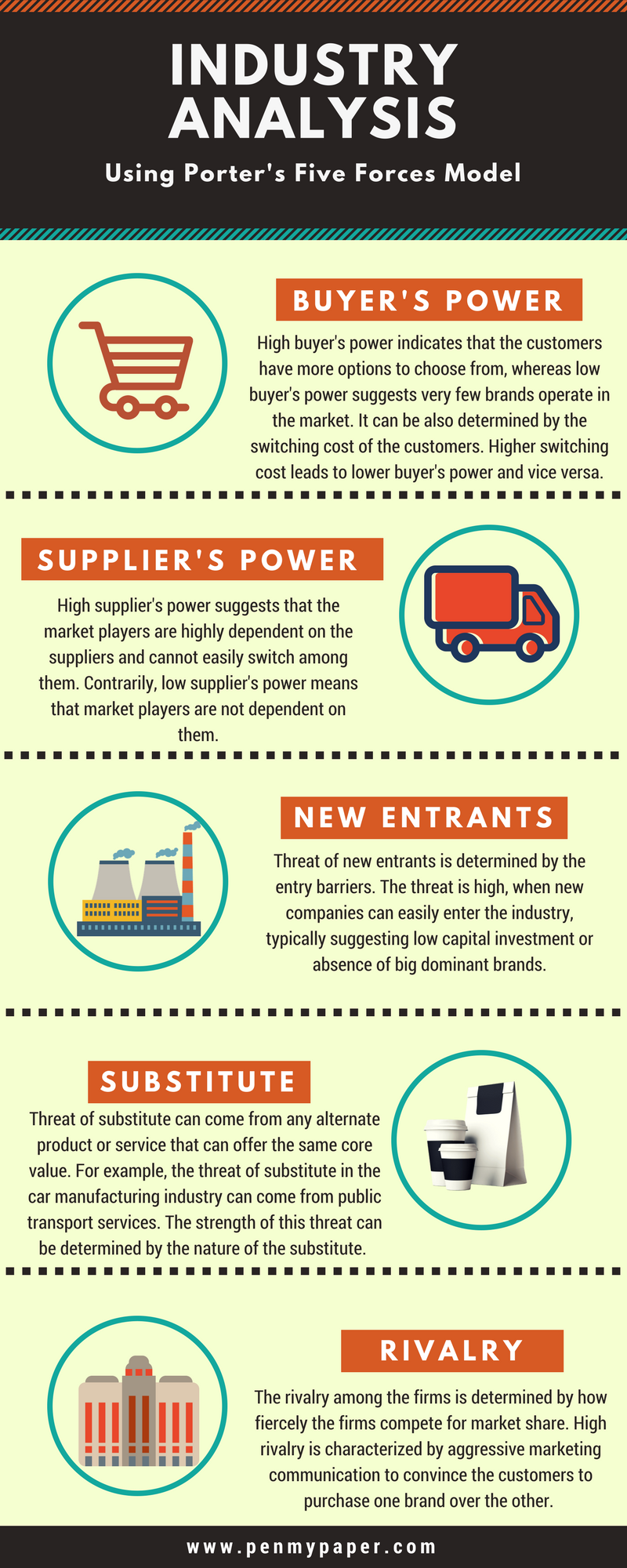

Porter's Five Forces Model

Porter's Five Forces is a powerful framework developed by Michael Porter to assess the competitive forces within an industry. This model helps you understand the industry's attractiveness and competitive dynamics.

It consists of five key forces:

- Threat of New Entrants: This force evaluates how easy or difficult it is for new companies to enter the industry. Factors that increase barriers to entry include high capital requirements, strong brand loyalty among existing players, and complex regulatory hurdles. For example, the airline industry has significant barriers to entry due to the need for large capital investments in aircraft, airport facilities, and regulatory approvals.

- Bargaining Power of Suppliers: This force examines the influence suppliers have on the industry's profitability. Powerful suppliers can demand higher prices or impose unfavorable terms. For instance, in the automotive industry, suppliers of critical components like microchips can wield significant bargaining power if they are few in number or if their products are highly specialized.

- Bargaining Power of Buyers: The bargaining power of buyers assesses how much influence customers have in negotiating prices and terms. In industries where buyers have many alternatives, such as the smartphone market, they can demand lower prices and better features, putting pressure on manufacturers to innovate and compete.

- Threat of Substitutes: This force considers the availability of substitute products or services that could potentially replace what the industry offers. For example, the rise of electric vehicles represents a significant threat to the traditional gasoline-powered automotive industry as consumers seek eco-friendly alternatives.

- Competitive Rivalry: Competitive rivalry assesses the intensity of competition among existing firms in the industry. A highly competitive industry, such as the smartphone market, often leads to price wars and aggressive marketing strategies as companies vie for market share.

Example: Let's consider the coffee shop industry . New entrants face relatively low barriers, as they can set up a small shop with limited capital. However, the bargaining power of suppliers, such as coffee bean producers, can vary depending on the region and the coffee's rarity. Bargaining power with buyers is moderate, as customers often have several coffee shops to choose from. Threats of substitutes may include energy drinks or homemade coffee, while competitive rivalry is high, with numerous coffee chains and independent cafes competing for customers.

SWOT Analysis

SWOT Analysis is a versatile tool used to assess an organization's internal strengths and weaknesses, as well as external opportunities and threats. By conducting a SWOT analysis, you can gain a comprehensive understanding of your industry and formulate effective strategies.

- Strengths: These are the internal attributes and capabilities that give your business a competitive advantage. For instance, if you're a tech company, having a talented and innovative team can be considered a strength.

- Weaknesses: Weaknesses are internal factors that hinder your business's performance. For example, a lack of financial resources or outdated technology can be weaknesses that need to be addressed.

- Opportunities: Opportunities are external factors that your business can capitalize on. This could be a growing market segment, emerging technologies, or changing consumer trends.

- Threats: Threats are external factors that can potentially harm your business. Examples of threats might include aggressive competition, economic downturns, or regulatory changes.

Example: Let's say you're analyzing the fast-food industry. Strengths could include a well-established brand, a wide menu variety, and efficient supply chain management. Weaknesses may involve a limited focus on healthy options and potential labor issues. Opportunities could include the growing trend toward healthier eating, while threats might encompass health-conscious consumer preferences and increased competition from delivery apps.

PESTEL Analysis

PESTEL Analysis examines the external macro-environmental factors that can impact your industry. The acronym stands for:

- Political: Political factors encompass government policies, stability, and regulations. For example, changes in tax laws or trade agreements can affect industries like international manufacturing.

- Economic: Economic factors include economic growth, inflation rates, and exchange rates. A fluctuating currency exchange rate can influence export-oriented industries like tourism.

- Social: Social factors encompass demographics, cultural trends, and social attitudes. An aging population can lead to increased demand for healthcare services and products.

- Technological: Technological factors involve advancements and innovations. Industries like telecommunications are highly influenced by technological developments, such as the rollout of 5G networks.

- Environmental: Environmental factors cover sustainability, climate change, and ecological concerns. Industries such as renewable energy are directly impacted by environmental regulations and consumer preferences.

- Legal: Legal factors encompass laws, regulations, and compliance requirements. The pharmaceutical industry, for instance, faces stringent regulatory oversight and patent protection laws.

Example: Consider the automobile manufacturing industry. Political factors may include government incentives for electric vehicles. Economic factors can involve fluctuations in fuel prices affecting consumer preferences for fuel-efficient cars. Social factors might encompass the growing interest in eco-friendly transportation options. Technological factors could relate to advancements in autonomous driving technology. Environmental factors may involve emissions regulations, while legal factors could pertain to safety standards and recalls.

Industry Life Cycle Analysis

Industry Life Cycle Analysis categorizes industries into various stages based on their growth and maturity. Understanding where your industry stands in its life cycle can help shape your strategies.

- Introduction: In the introduction stage, the industry is characterized by slow growth, limited competition, and a focus on product development. New players enter the market, and consumers become aware of the product or service. For instance, electric scooters were introduced as a new mode of transportation in recent years.

- Growth: The growth stage is marked by rapid market expansion, increased competition, and rising demand. Companies focus on gaining market share, and innovation is vital. The ride-sharing industry, exemplified by companies like Uber and Lyft, experienced significant growth in this stage.

- Maturity: In the maturity stage, the market stabilizes, and competition intensifies. Companies strive to maintain market share and differentiate themselves through branding and customer loyalty programs. The smartphone industry reached maturity with multiple established players.

- Decline: In the decline stage, the market saturates, and demand decreases. Companies must adapt or diversify to survive. The decline of traditional print media is a well-known example.

Example: Let's analyze the video streaming industry . The introduction stage saw the emergence of streaming services like Netflix. In the growth stage, more players entered the market, and the industry saw rapid expansion. The industry is currently in the maturity stage, with established platforms like Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Disney+ competing for market share. However, with continued innovation and changing consumer preferences, the decline stage may eventually follow.

Value Chain Analysis

Value Chain Analysis dissects a company's activities into primary and support activities to identify areas of competitive advantage. Primary activities directly contribute to creating and delivering a product or service, while support activities facilitate primary activities.

- Primary Activities: These activities include inbound logistics (receiving and storing materials), operations (manufacturing or service delivery), outbound logistics (distribution), marketing and sales, and customer service.

- Support Activities: Support activities include procurement (acquiring materials and resources), technology development (R&D and innovation), human resource management (recruitment and training), and infrastructure (administrative and support functions).

Example: Let's take the example of a smartphone manufacturer. Inbound logistics involve sourcing components, such as processors and displays. Operations include assembly and quality control. Outbound logistics cover shipping and distribution. Marketing and sales involve advertising and retail partnerships. Customer service handles warranty and support.

Procurement ensures a stable supply chain for components. Technology development focuses on research and development of new features. Human resource management includes hiring and training skilled engineers. Infrastructure supports the company's administrative functions.

By applying these frameworks and models effectively, you can better understand your industry, identify strategic opportunities and threats, and develop a solid foundation for informed decision-making.

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Once you have your data, it's time to start interpreting and analyzing the data you've collected during your industry analysis.

You can unlock the full potential of your data with Appinio 's comprehensive research platform. Beyond aiding in data collection, Appinio simplifies the intricate process of data interpretation and analysis. Our intuitive tools empower you to effortlessly transform raw data into actionable insights, giving you a competitive edge in understanding your industry.

Whether it's assessing market trends, evaluating the competitive landscape, or understanding customer behavior, Appinio offers a holistic solution to uncover valuable findings. With our platform, you can make informed decisions, strategize effectively, and stay ahead of industry shifts.

Experience the ease of data collection and interpretation with Appinio – book a demo today!

Book a Demo

1. Analyze Market Size and Growth

Analyzing the market's size and growth is essential for understanding its dynamics and potential. Here's how to conduct a robust analysis:

- Market Size Calculation: Determine the total market size in terms of revenue, units sold, or the number of customers. This figure serves as a baseline for evaluating the industry's scale.

- Historical Growth Analysis: Examine historical data to identify growth trends. This includes looking at past year-over-year growth rates and understanding the factors that influenced them.

- Projected Growth Assessment: Explore industry forecasts and projections to gain insights into the expected future growth of the market. Consider factors such as emerging technologies, changing consumer preferences, and economic conditions.

- Segmentation Analysis: If applicable, analyze market segmentation data to identify growth opportunities in specific market segments. Understand which segments are experiencing the most significant growth and why.

2. Assess Market Trends

Stay ahead of the curve by closely monitoring and assessing market trends. Here's how to effectively evaluate trends within your industry.

- Consumer Behavior Analysis: Dive into consumer behavior data to uncover shifts in preferences, buying patterns, and shopping habits. Understand how technological advancements and cultural changes influence consumer choices.

- Technological Advancements: Keep a keen eye on technological developments that impact your industry. Assess how innovations such as AI, IoT, blockchain, or automation are changing the competitive landscape.

- Regulatory Changes: Stay informed about regulatory shifts and their potential consequences for your industry. Regulations can significantly affect product development, manufacturing processes, and market entry strategies.

- Sustainability and Environmental Trends: Consider the growing importance of sustainability and environmental concerns. Evaluate how your industry is adapting to eco-friendly practices and how these trends affect consumer choices.

3. Evaluate Competitive Landscape

Understanding the competitive landscape is critical for positioning your business effectively. To perform a comprehensive evaluation:

- Competitive Positioning: Determine where your company stands in comparison to competitors. Identify your unique selling propositions and areas where you excel.

- Market Share Analysis: Continuously monitor market share among industry players. Identify trends in market share shifts and assess the strategies that lead to such changes.

- Competitive Advantages and Weaknesses: Analyze your competitors' strengths and weaknesses. Identify areas where you can capitalize on their weaknesses and where you need to fortify your own strengths.

4. Identify Key Success Factors

Recognizing and prioritizing key success factors is crucial for developing effective strategies. To identify and leverage these factors:

- Customer Satisfaction: Prioritize customer satisfaction as a critical success factor. Satisfied customers are more likely to become loyal advocates and contribute to long-term success.

- Quality and Innovation: Focus on product or service quality and continuous innovation. Meeting and exceeding customer expectations can set your business apart from competitors.

- Cost Efficiency: Strive for cost efficiency in your operations. Identifying cost-saving opportunities can lead to improved profitability.

- Marketing and Branding Excellence: Invest in effective marketing and branding strategies to create a strong market presence. Building a recognizable brand can drive customer loyalty and growth.

5. Analyze Customer Behavior and Preferences

Understanding your target audience is central to success. Here's how to analyze customer behavior and preferences:

- Market Segmentation: Use market segmentation to categorize customers based on demographics, psychographics , and behavior. This allows for more personalized marketing and product/service offerings.

- Customer Surveys and Feedback: Gather customer feedback through surveys and feedback mechanisms. Understand their pain points, preferences, and expectations to tailor your offerings.

- Consumer Journey Mapping: Map the customer journey to identify touchpoints where you can improve engagement and satisfaction. Optimize the customer experience to build brand loyalty.

By delving deep into data interpretation and analysis, you can gain valuable insights into your industry, uncover growth opportunities, and refine your strategic approach.

How to Conduct Competitor Analysis?

Competitor analysis is a critical component of industry analysis as it provides valuable insights into your rivals, helping you identify opportunities, threats, and areas for improvement.

1. Identify Competitors

Identifying your competitors is the first step in conducting a thorough competitor analysis. Competitors can be classified into several categories:

- Direct Competitors: These are companies that offer similar products or services to the same target audience. They are your most immediate competitors and often compete directly with you for market share.

- Indirect Competitors: Indirect competitors offer products or services that are related but not identical to yours. They may target a slightly different customer segment or provide an alternative solution to the same problem.

- Potential Competitors: These companies could enter your market in the future. Identifying potential competitors early allows you to anticipate and prepare for new entrants.

- Substitute Products or Services: While not traditional competitors, substitute products or services can fulfill the same customer needs or desires. Understanding these alternatives is crucial to your competitive strategy.

2. Analyze Competitor Strengths and Weaknesses

Once you've identified your competitors, you need to analyze their strengths and weaknesses. This analysis helps you understand how to position your business effectively and identify areas where you can gain a competitive edge.

- Strengths: Consider what your competitors excel at. This could include factors such as brand recognition, innovative products, a large customer base, efficient operations, or strong financial resources.

- Weaknesses: Identify areas where your competitors may be lacking. Weaknesses could involve limited product offerings, poor customer service, outdated technology, or financial instability.

3. Competitive Positioning

Competitive positioning involves defining how you want your business to be perceived relative to your competitors. It's about finding a unique position in the market that sets you apart. Consider the following strategies:

- Cost Leadership: Strive to be the low-cost provider in your industry. This positioning appeals to price-conscious consumers.

- Differentiation: Focus on offering unique features or attributes that make your products or services stand out. This can justify premium pricing.

- Niche Market: Target a specific niche or segment of the market that may be underserved by larger competitors. Tailor your offerings to meet their unique needs.

- Innovation and Technology: Emphasize innovation and technology to position your business as a leader in product or service quality.

- Customer-Centric: Prioritize exceptional customer service and customer experience to build loyalty and a positive reputation.

4. Benchmarking and Gap Analysis

Benchmarking involves comparing your business's performance and practices with those of your competitors or industry leaders. Gap analysis helps identify areas where your business falls short and where improvements are needed.

- Performance Benchmarking: Compare key performance metrics, such as revenue, profitability, market share, and customer satisfaction, with those of your competitors. Identify areas where your performance lags behind or exceeds industry standards.

- Operational Benchmarking: Analyze your operational processes, supply chain, and cost structures compared to your competitors. Look for opportunities to streamline operations and reduce costs.

- Product or Service Benchmarking: Evaluate the features, quality, and pricing of your products or services relative to competitors. Identify gaps and areas for improvement.

- Marketing and Sales Benchmarking: Assess your marketing strategies, customer acquisition costs, and sales effectiveness compared to competitors. Determine whether your marketing efforts are performing at a competitive level.

Market Entry and Expansion Strategies

Market entry and expansion strategies are crucial for businesses looking to enter new markets or expand their presence within existing ones. These strategies can help you effectively target and penetrate your chosen markets.

Market Segmentation and Targeting

- Market Segmentation: Begin by segmenting your target market into distinct groups based on demographics , psychographics, behavior, or other relevant criteria. This helps you understand the diverse needs and preferences of different customer segments.

- Targeting: Once you've segmented the market, select specific target segments that align with your business goals and capabilities. Tailor your marketing and product/service offerings to appeal to these chosen segments.

Market Entry Modes

Selecting the proper market entry mode is crucial for a successful expansion strategy. Entry modes include:

- Exporting: Sell your products or services in international markets through exporting. This is a low-risk approach, but it may limit your market reach.

- Licensing and Franchising: License your brand, technology, or intellectual property to local partners or franchisees. This allows for rapid expansion while sharing the risk and control.

- Joint Ventures and Alliances: Partner with local companies through joint ventures or strategic alliances. This approach leverages local expertise and resources.

- Direct Investment: Establish a physical presence in the target market through subsidiaries, branches, or wholly-owned operations. This offers full control but comes with higher risk and investment.

Competitive Strategy Formulation

Your competitive strategy defines how you will compete effectively in the target market.

- Cost Leadership: Strive to offer products or services at lower prices than competitors while maintaining quality. This strategy appeals to price-sensitive consumers.

- Product Differentiation: Focus on offering unique and innovative products or services that stand out in the market. This strategy justifies premium pricing.

- Market Niche: Target a specific niche or segment within the market that is underserved or has particular needs. Tailor your offerings to meet the unique demands of this niche.

- Market Expansion : Expand your product or service offerings to capture a broader share of the market. This strategy involves diversifying your offerings to appeal to a broader audience.

- Global Expansion: Consider expanding internationally to tap into new markets and diversify your customer base. This strategy involves thorough market research and adaptation to local cultures and regulations.

International Expansion Considerations

If your expansion strategy involves international markets, there are several additional considerations to keep in mind.

- Market Research: Conduct in-depth market research to understand the target country's cultural, economic, and legal differences.

- Regulatory Compliance: Ensure compliance with international trade regulations, customs, and import/export laws.

- Cultural Sensitivity: Adapt your marketing and business practices to align with the cultural norms and preferences of the target market.

- Localization: Consider adapting your products, services, and marketing materials to cater to local tastes and languages.

- Risk Assessment: Evaluate the political, economic, and legal risks associated with operating in the target country. Develop risk mitigation strategies.

By carefully analyzing your competitors and crafting effective market entry and expansion strategies, you can position your business for success in both domestic and international markets.

Risk Assessment and Mitigation

Risk assessment and mitigation are crucial aspects of industry analysis and strategic planning. Identifying potential risks, assessing vulnerabilities, and implementing effective risk management strategies are essential for business continuity and success.

1. Identify Industry Risks

- Market Risks: These risks pertain to factors such as changes in market demand, economic downturns, shifts in consumer preferences, and fluctuations in market prices. For example, the hospitality industry faced significant market risks during the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in decreased travel and tourism .

- Regulatory and Compliance Risks: Regulatory changes, compliance requirements, and government policies can pose risks to businesses. Industries like healthcare are particularly susceptible to regulatory changes that impact operations and reimbursement.

- Technological Risks: Rapid technological advancements can disrupt industries and render existing products or services obsolete. Companies that fail to adapt to technological shifts may face obsolescence.

- Operational Risks: These risks encompass internal factors that can disrupt operations, such as supply chain disruptions, equipment failures, or cybersecurity breaches.

- Financial Risks: Financial risks include factors like liquidity issues, credit risk , and market volatility. Industries with high capital requirements, such as real estate development, are particularly vulnerable to financial risks.

- Competitive Risks: Intense competition and market saturation can pose challenges to businesses. Failing to respond to competitive threats can result in loss of market share.

- Global Risks: Industries with a worldwide presence face geopolitical risks, currency fluctuations, and international trade uncertainties. For instance, the automotive industry is susceptible to trade disputes affecting the supply chain.

2. Assess Business Vulnerabilities

- SWOT Analysis: Revisit your SWOT analysis to identify internal weaknesses and threats. Assess how these weaknesses may exacerbate industry risks.

- Financial Health: Evaluate your company's financial stability, debt levels, and cash flow. Identify vulnerabilities related to financial health that could hinder your ability to withstand industry-specific challenges.

- Operational Resilience: Assess the robustness of your operational processes and supply chain. Identify areas where disruptions could occur and develop mitigation strategies.

- Market Positioning: Analyze your competitive positioning and market share. Recognize vulnerabilities in your market position that could be exploited by competitors.

- Compliance and Regulatory Adherence: Ensure that your business complies with relevant regulations and standards. Identify vulnerabilities related to non-compliance or regulatory changes.

3. Risk Management Strategies

- Risk Avoidance: In some cases, the best strategy is to avoid high-risk ventures or markets altogether. This may involve refraining from entering certain markets or discontinuing products or services with excessive risk.

- Risk Reduction: Implement measures to reduce identified risks. For example, diversifying your product offerings or customer base can reduce dependence on a single revenue source.

- Risk Transfer: Transfer some risks through methods such as insurance or outsourcing. For instance, businesses can mitigate cybersecurity risks by purchasing cyber insurance.

- Risk Acceptance: In cases where risks cannot be entirely mitigated, it may be necessary to accept a certain level of risk and have contingency plans in place to address potential issues.

- Continuous Monitoring: Establish a system for continuous risk monitoring. Regularly assess the changing landscape and adjust risk management strategies accordingly.

4. Contingency Planning

Contingency planning involves developing strategies and action plans to respond effectively to unforeseen events or crises. It ensures that your business can maintain operations and minimize disruptions in the face of adverse circumstances. Key elements of contingency planning include:

- Risk Scenarios: Identify potential risk scenarios specific to your industry and business. These scenarios should encompass a range of possibilities, from minor disruptions to major crises.

- Response Teams: Establish response teams with clearly defined roles and responsibilities. Ensure that team members are trained and ready to act in the event of a crisis.

- Communication Plans: Develop communication plans that outline how you will communicate with employees, customers, suppliers, and other stakeholders during a crisis. Transparency and timely communication are critical.

- Resource Allocation: Determine how resources, including personnel, finances, and equipment, will be allocated in response to various scenarios.

- Testing and Simulation: Regularly conduct tests and simulations of your contingency plans to identify weaknesses and areas for improvement. Ensure your response teams are well-practiced and ready to execute the plans effectively.

- Documentation and Record Keeping: Maintain comprehensive documentation of contingency plans, response procedures, and communication protocols. This documentation should be easily accessible to relevant personnel.

- Review and Update: Continuously review and update your contingency plans to reflect changing industry dynamics and evolving risks. Regularly seek feedback from response teams to make improvements.

By identifying industry risks, assessing vulnerabilities, implementing risk management strategies, and developing robust contingency plans, your business can navigate the complexities of the industry landscape with greater resilience and preparedness.

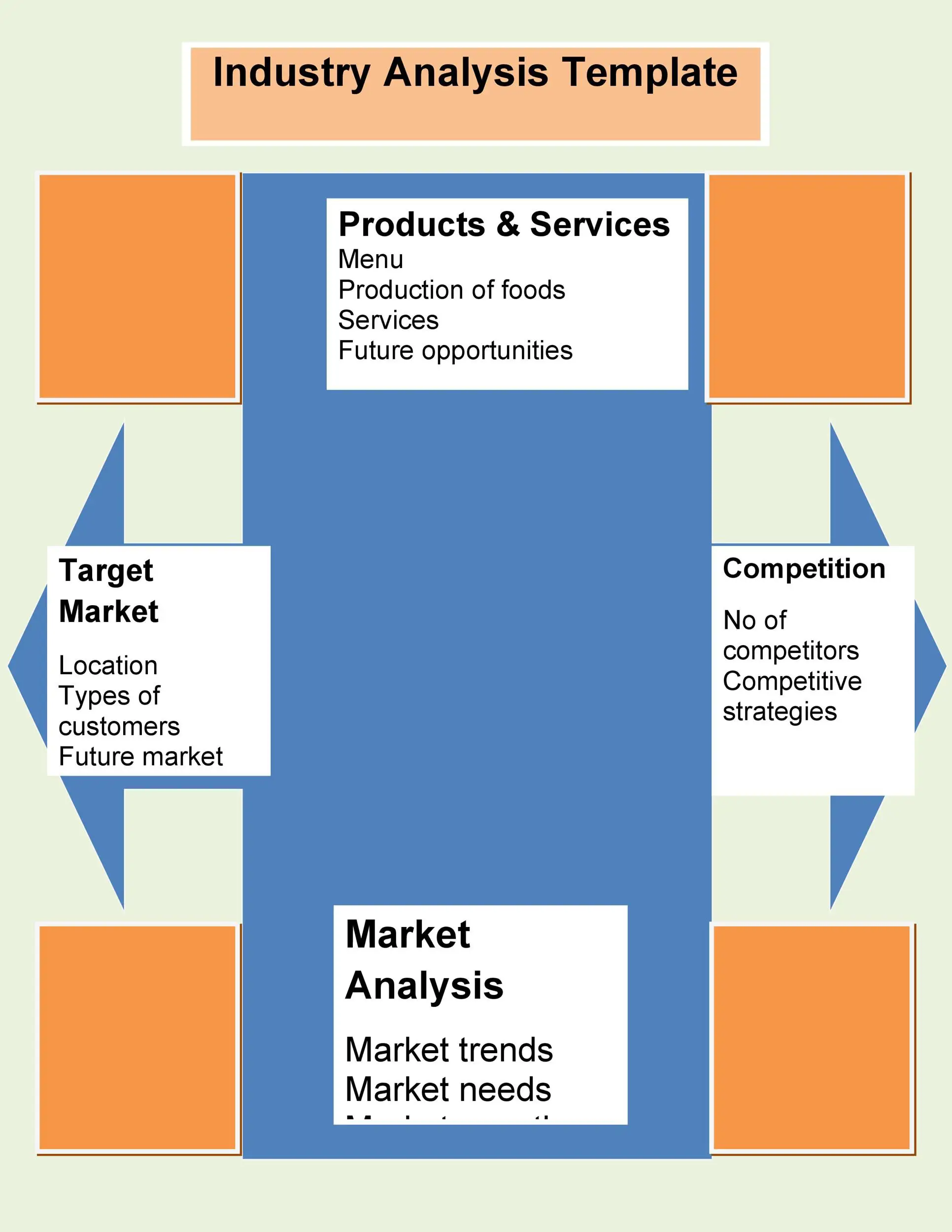

Industry Analysis Template

When embarking on the journey of Industry Analysis, having a well-structured template is akin to having a reliable map for your exploration. It provides a systematic framework to ensure you cover all essential aspects of the analysis. Here's a breakdown of an industry analysis template with insights into each section.

Industry Overview

- Objective: Provide a broad perspective of the industry.

- Market Definition: Define the scope and boundaries of the industry, including its products, services, and target audience.

- Market Size and Growth: Present current market size, historical growth trends, and future projections.

- Key Players: Identify major competitors and their market share.

- Market Trends: Highlight significant trends impacting the industry.

Competitive Analysis

- Objective: Understand the competitive landscape within the industry.

- Competitor Identification: List direct and indirect competitors.

- Competitor Profiles: Provide detailed profiles of major competitors, including their strengths, weaknesses, strategies, and market positioning.

- SWOT Analysis: Conduct a SWOT analysis for each major competitor.

- Market Share Analysis: Analyze market share distribution among competitors.

Market Analysis

- Objective: Explore the characteristics and dynamics of the market.

- Customer Segmentation: Define customer segments and their demographics, behavior, and preferences.

- Demand Analysis: Examine factors driving demand and customer buying behavior.

- Supply Chain Analysis: Map out the supply chain, identifying key suppliers and distribution channels.

- Regulatory Environment: Discuss relevant regulations, policies, and compliance requirements.

Technological Analysis

- Objective: Evaluate the technological landscape impacting the industry.

- Technological Trends: Identify emerging technologies and innovations relevant to the industry.

- Digital Transformation: Assess the level of digitalization within the industry and its impact on operations and customer engagement.

- Innovation Opportunities: Explore opportunities for leveraging technology to gain a competitive edge.

Financial Analysis

- Objective: Analyze the financial health of the industry and key players.

- Revenue and Profitability: Review industry-wide revenue trends and profitability ratios.

- Financial Stability: Assess financial stability by examining debt levels and cash flow.

- Investment Patterns: Analyze capital expenditure and investment trends within the industry.

Consumer Insights

- Objective: Understand consumer behavior and preferences.

- Consumer Surveys: Conduct surveys or gather data on consumer preferences, buying habits , and satisfaction levels.

- Market Perception: Gauge consumer perception of brands and products in the industry.

- Consumer Feedback: Collect and analyze customer feedback and reviews.

SWOT Analysis for Your Business

- Objective: Assess your own business within the industry context.

- Strengths: Identify internal strengths that give your business a competitive advantage.

- Weaknesses: Recognize internal weaknesses that may hinder your performance.

- Opportunities: Explore external opportunities that your business can capitalize on.

- Threats: Recognize external threats that may impact your business.

Conclusion and Recommendations

- Objective: Summarize key findings and provide actionable recommendations.

- Summary: Recap the most critical insights from the analysis.

- Recommendations: Offer strategic recommendations for your business based on the analysis.

- Future Outlook: Discuss potential future developments in the industry.

While this template provides a structured approach, adapt it to the specific needs and objectives of your Industry Analysis. It serves as your guide, helping you navigate through the complex landscape of your chosen industry, uncovering opportunities, and mitigating risks along the way.

Remember that the depth and complexity of your industry analysis may vary depending on your specific goals and the industry you are assessing. You can adapt this template to focus on the most relevant aspects and conduct thorough research to gather accurate data and insights. Additionally, consider using industry-specific data sources, reports, and expert opinions to enhance the quality of your analysis.

Industry Analysis Examples

To grasp the practical application of industry analysis, let's delve into a few diverse examples across different sectors. These real-world scenarios demonstrate how industry analysis can guide strategic decision-making.

Tech Industry - Smartphone Segment

Scenario: Imagine you are a product manager at a tech company planning to enter the smartphone market. Industry analysis reveals that the market is highly competitive, dominated by established players like Apple and Samsung.

Use of Industry Analysis:

- Competitive Landscape: Analyze the strengths and weaknesses of competitors, identifying areas where they excel (e.g., Apple's brand loyalty ) and where they might have vulnerabilities (e.g., consumer demand for more affordable options).

- Market Trends: Identify trends like the growing demand for sustainable technology and 5G connectivity, guiding product development and marketing strategies.

- Regulatory Factors: Consider regulatory factors related to intellectual property rights, patents, and international trade agreements that can impact market entry and operations.

- Outcome: Armed with insights from industry analysis, you decide to focus on innovation, emphasizing features like eco-friendliness and affordability. This niche approach helps your company gain a foothold in the competitive market.

Healthcare Industry - Telehealth Services

Scenario: You are a healthcare entrepreneur exploring opportunities in the telehealth sector, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Industry analysis is critical due to rapid market changes.

- Market Size and Growth: Evaluate the growing demand for telehealth services, driven by the need for remote healthcare during the pandemic and convenience factors.

- Regulatory Environment: Understand the evolving regulatory landscape, including changes in telemedicine reimbursement policies and licensing requirements.

- Technological Trends: Explore emerging technologies such as AI-powered diagnosis and remote monitoring that can enhance service offerings.

- Outcome: Industry analysis underscores the potential for telehealth growth. You adapt your business model to align with regulatory changes, invest in cutting-edge technology, and focus on patient-centric care, positioning your telehealth service for success.

Food Industry - Plant-Based Foods

Scenario: As a food industry entrepreneur , you are considering entering the plant-based foods market, driven by increasing consumer interest in health and sustainability.

- Market Trends: Analyze the trend toward plant-based diets and sustainability, reflecting changing consumer preferences.

- Competitive Landscape: Assess the competitive landscape, understanding that established companies and startups are vying for market share.

- Consumer Behavior: Study consumer behavior, recognizing that health-conscious consumers seek plant-based alternatives.

- Outcome: Informed by industry analysis, you launch a line of plant-based products emphasizing both health benefits and sustainability. Effective marketing and product quality gain traction among health-conscious consumers, making your brand a success in the plant-based food industry.

These examples illustrate how industry analysis can guide strategic decisions, whether entering competitive tech markets, navigating dynamic healthcare regulations, or capitalizing on shifting consumer preferences in the food industry. By applying industry analysis effectively, businesses can adapt, innovate, and thrive in their respective sectors.

Industry Analysis is the compass that helps businesses chart their course in the vast sea of markets. By understanding the industry's dynamics, risks, and opportunities, you gain a strategic advantage that can steer your business towards success. From identifying competitors to mitigating risks and formulating competitive strategies, this guide has equipped you with the tools and knowledge needed to navigate the complexities of the business world.

Remember, Industry Analysis is not a one-time task; it's an ongoing journey. Keep monitoring market trends, adapting to changes, and staying ahead of the curve. With a solid foundation in industry analysis, you're well-prepared to tackle challenges, seize opportunities, and make well-informed decisions that drive your business toward prosperity. So, set sail with confidence and let industry analysis be your guiding star on the path to success.

How to Conduct Industry Analysis in Minutes?

Introducing Appinio , the real-time market research platform that transforms how you conduct Industry Analysis. Imagine getting real-time consumer insights in minutes, putting the power of data-driven decision-making at your fingertips. With Appinio, you can:

- Gain insights swiftly: Say goodbye to lengthy research processes. Appinio delivers answers fast, ensuring you stay ahead in the competitive landscape.

- No research degree required: Our intuitive platform is designed for everyone. You don't need a PhD in research to harness its capabilities.

- Global reach, local insights: Define your target group precisely from over 1200 characteristics and access consumer data in over 90 countries.

Join the loop 💌

Be the first to hear about new updates, product news, and data insights. We'll send it all straight to your inbox.

Get the latest market research news straight to your inbox! 💌

Wait, there's more

25.04.2024 | 37min read

Targeted Advertising: Definition, Benefits, Examples

17.04.2024 | 25min read

Quota Sampling: Definition, Types, Methods, Examples

15.04.2024 | 34min read

What is Market Share? Definition, Formula, Examples

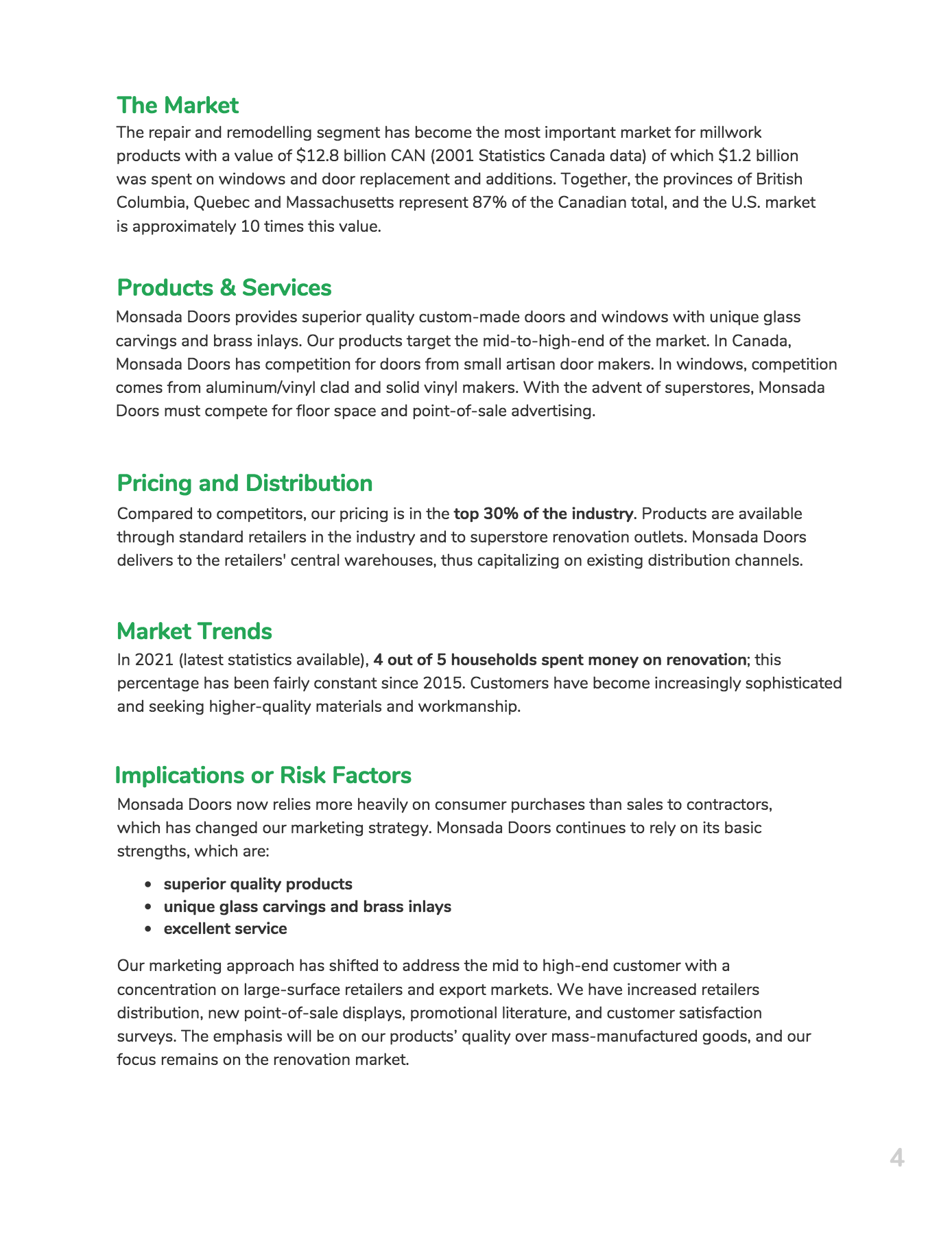

How to Write an Effective Business Plan: Industry Profile

Treana wunsch.

- December 7, 2022

Having an industry profile section in a business plan is essential for success. It serves to provide the reader with background information on the industry, along with its current trends and future projections. This section will help to assess whether or not an idea is feasible, as well as how competitive it may be in the marketplace.

The industry profile should include both qualitative and quantitative data. Qualitative data can illustrate points such as the current market share of competitors, product, price, promotion and distribution trends or any other relevant factors that may affect the business’s ability to succeed. Quantitative data consists of numerical figures like sales volume and growth rate of particular products within the industry over time.

Including this kind of information will help potential investors understand why your business should exist by highlighting its unique niche within the marketplace.

What is an industry?

An industry is an economic sector that produces goods and services. It is the driving force behind a country’s economy. Industries can range from large-scale enterprises with hundreds of employees to small, family-run businesses. As such, each industry has unique characteristics that must be taken into consideration when writing an effective business plan.

When researching an industry for your business plan, it’s important to understand the factors affecting its performance, including market trends and government regulations. Additionally, you should consider the competition in the market – both current players and potential new entrants – as well as customer habits and preferences. All this information will help you gain insight into how best to position your business within this particular industry in order to succeed.

Industry classification

When creating an industry profile, it’s important to understand the classification system used by experts in the field. This includes macro industries, subsectors, industries and even trade groups, each of which provides further detail on a company’s market.

The North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) is one of the most widely used systems for classifying businesses by type of activity and geographic location. It categorizes establishments based on their primary production process or product line and assigns them a six-digit code that uniquely identifies them within their sector. The NAICS also makes it easy to compare businesses across different sectors and regions by grouping similar companies together under broader categories such as transportation or manufacturing.

How to find your industry

Finding the right industry for your company is a crucial step in the process of writing an effective business plan. Understanding what industry you are entering and who your competitors are will help determine how to structure your plan and position yourself in the market. Knowing where to start can be challenging, so here are some tips on how to find your industry and create an effective business plan.

First off, research current trends in the market and identify areas that you believe have potential for growth or represent a good fit for your company’s products or services. Look at macroeconomic data from government sources such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics, as well as industry-specific reports from organizations like Forbes or Business Insider. Analyze these reports to determine which industries may offer more potential than others, then narrow down your choices by researching key factors such as demand, competition and capital requirements within those industries.

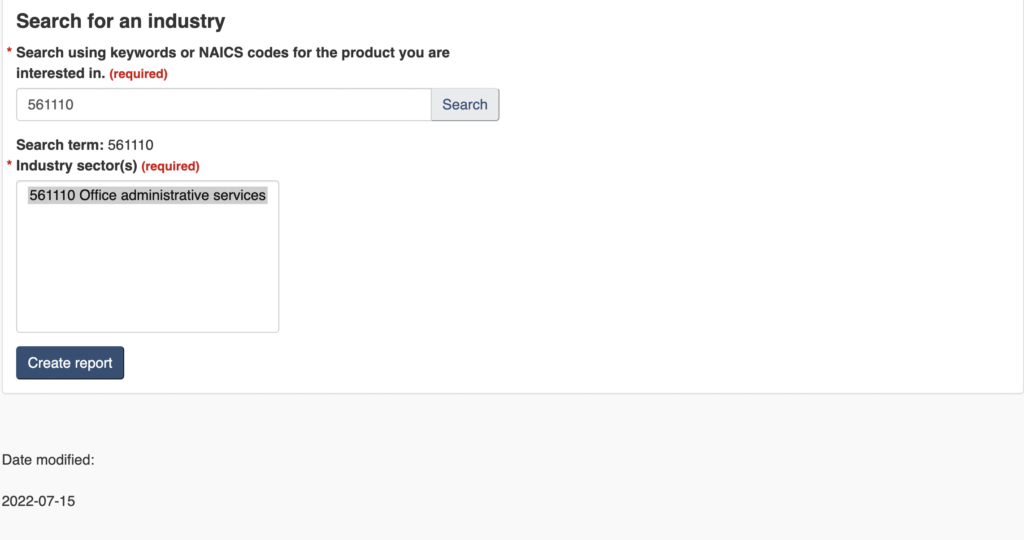

How to find your industry NAICS code

The first step in writing an effective business plan is to identify your industry and the associated North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code. NAICS codes are used by governments, businesses, and other organizations to classify industries according to the type of economic activity they engage in. Knowing your industry NAICS code is essential for gathering information about your industry and its competitive landscape, as well as determining which regulations apply to you.

Fortunately, it’s easy to find out what your industry NAICS code is. To begin, visit the Statistics Canada website and use their searchable database of NAICS codes. You can also contact a government agency or trade association related to your industry for more help finding your specific NAICS code.

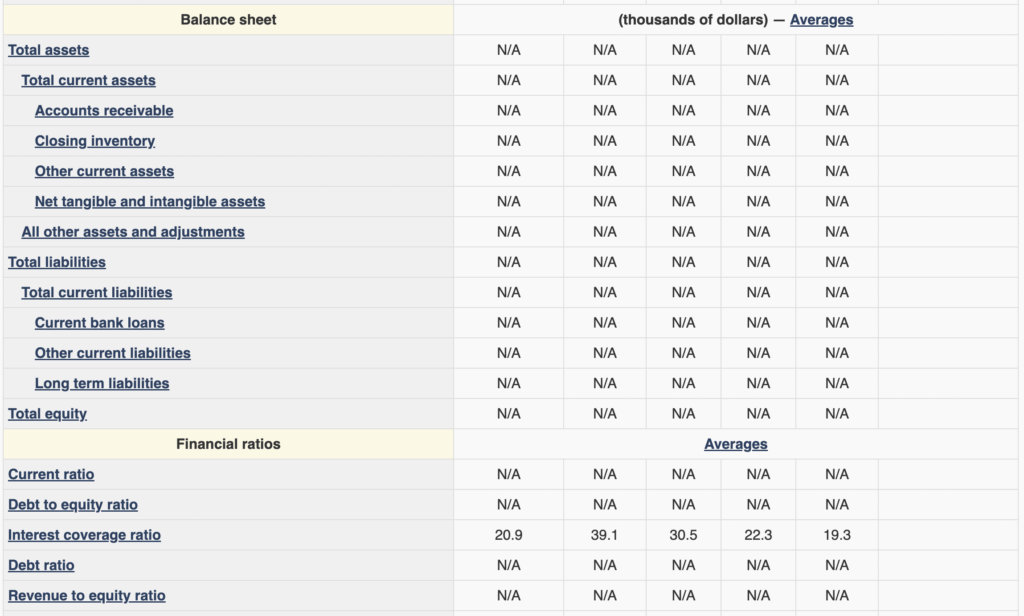

Financial Performance Data by Industry in Canada

Financial performance data by industry in Canada is an important factor to consider when writing an effective business plan. Knowing the key financial ratios specific to your industry will help you benchmark your performance, identify potential weak spots and develop strategies for growth. Different industries have their own unique financial metrics with which they measure success. It is important to understand these ratios and how they apply to you and your target market before writing a comprehensive business plan.

By analyzing the common financial trends of businesses within certain industries in Canada, you can gain valuable insight into how successful companies in that sector operate. Using this information, you can adjust your strategy accordingly so that it meets or exceeds the expectations of investors and other stakeholders involved with your venture. The ability to effectively identify industry-specific financial indicators gives businesses a competitive edge that can result in greater profitability over time.

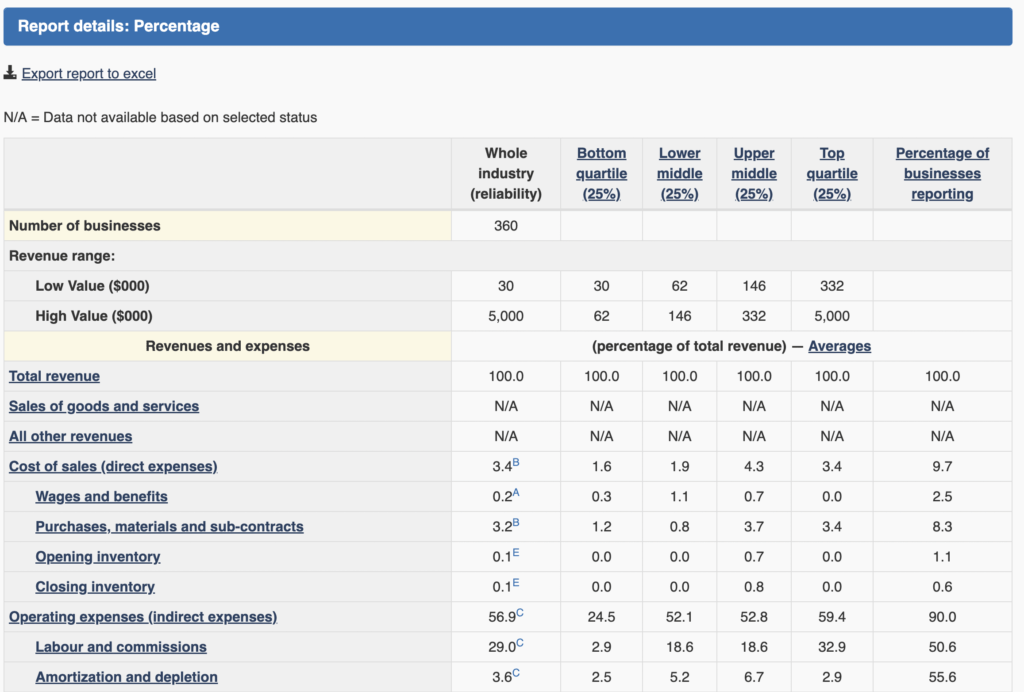

You can find your industry’s financial performance here . Choose the location you want data from then choose ‘total revenue’ and ‘percentage’ and ‘search for an industry’ as your other options. Then type your NAICS code that you discovered under ‘Search for an industry’ and click on ‘search’.

Your options will come up below. Choose the appropriate option and ‘create report’.

If balance sheet data is available it will also be shown.

The lower portion of the report indicates the percentage of businesses that are profitable.

You can also do an internet search of the NAICS code to see what else comes up.

Industry codes help you to discover your specific industry and define the boundaries of that industry. Understanding the health of your industry and where the future of the industry may be going offers valuable insight into how successful your business could be. You can also measure your business performance against industry performance. All of this helps you to make better decisions for your business.

FREE Business Plan Template

Click to download the Classic Google Docs Business Plan Template

Industry Lifecycle

Industry Lifecycle is an important concept for any business to understand and plan for. It is the process of a given industry maturing over time and passing through distinct stages of growth, decline, and eventual restabilization. Knowing the lifecycle of an industry can help you plan ahead by understanding where it is currently, what its likely future will be, and how to best capitalize on its strengths while minimizing weaknesses.

To write an effective business plan, an understanding of the industry’s current position in its lifecycle is essential. This knowledge will help you create realistic goals and strategies that are tailored to your specific market conditions.

This section should provide a comprehensive overview of the industry and its particular lifecycle. The lifecycle of an industry often determines how successful businesses in that sector will be and what strategies are best for them to pursue.

In order to determine the lifecycle of an industry, you must look at key factors such as trends in demand, competition from substitutes or new entrants into the market, technological advances, and changes in consumer preferences. It’s also necessary to assess potential risks within the sector including shifts in regulations or economic dips that could negatively impact performance. Additionally, you should consider how long the industry has been around and whether it’s likely to grow or decline over time.

The automotive industry is a good example of the industry lifecycle. It began with a period of introduction, followed by growth, then maturity and eventually decline. During the introduction phase, new technologies like the automobile were developed and brought to market. There was strong growth as the market for automobiles expanded. As the industry grew, it matured and reached a stable point where existing companies competed. Eventually, the industry declined as new technologies and sources of energy made it obsolete.

Industry History

It’s essential for aspiring entrepreneurs to have a basic understanding of the history of their chosen industry. Industry history is used to build an understanding of the current state of the market, as well as its potential for growth in the future. By studying past trends and developments in an industry, entrepreneurs can identify successful strategies that have been employed by previous businesses, enabling them to develop a comprehensive business plan that stands out from competitors. Moreover, they can use this information to gauge how quickly or slowly their venture may grow over time.

Industry Leaders

Industry Leaders are the heart of any successful business. Whether you’re launching a startup or expanding an existing business, understanding your industry and its leaders is essential for success. An effective business plan must include an industry profile to demonstrate comprehensive knowledge of the competitive landscape and identify strategies for establishing a foothold in the market.

An Industry Profile is a detailed analysis of your industry’s size, structure, growth rate, key players, trends and more. It begins with examining leading companies – their products/services; target markets; operations & financials; competitive advantages – and how they contribute to industry dynamics. Knowing who sets the standard in terms of quality, innovation & sustainability will also help evaluate customer preferences & overall satisfaction levels within the sector. Once identified, these insights can be used to craft actionable plans that position your company as a leader in its respective field.

Industry Threats

To create an accurate industry profile, you must carefully consider the various external factors that can potentially threaten your company’s operations. These threats may include changes in laws or regulations, economic conditions such as inflation or recession, competition from other businesses, technological advances, new entrants into the market, and customer preferences.

By analyzing these elements of your industry and assessing their potential impact on your business plan, you can better anticipate changes in the environment and develop strategies to minimize any adverse effects these threats might have on your company’s profitability.

Industry Predictions

Industry predictions can help businesses stay ahead of the curve and plan for the future. When researching your industry profile, it is essential to look at key economic indicators such as consumer spending habits, employment rates, and capital investments. Additionally, consider major disruptors like technological advancements or regulatory changes that may influence your market dynamics over time. By gaining a comprehensive understanding of these factors, you will be better equipped to make informed decisions when creating your business plan and developing strategies for growth.

Tuesday Takeaways Newsletter

Industry associations.

Industry associations play an integral role in the development of a business plan. They provide industry professionals with information, resources, and contacts to help them create successful business plans and gain strategic insights into their industry. Furthermore, they can also help entrepreneurs identify potential customers and develop marketing strategies based on current industry trends.

The first step to utilizing an industry association is researching the available options and learning about their current activities. After finding one that fits the needs of your business plan, it’s important to join the organization so you have access to all the benefits they offer. Once you’ve joined, be sure to take advantage of any educational opportunities or events designed for members; these are excellent ways for entrepreneurs to network with other professionals in their field and learn more about specific trends related to their industry.

Industry Statistical Analysis