Oratory Club

Public Speaking Helpline

How to Introduce Group Members in a Presentation Script

In a presentation script, introduce group members by briefly stating their names and roles. In this introduction, we will discuss the best ways to introduce group members in a presentation script, ensuring clarity and engagement with the audience.

A well-crafted introduction can set the tone for a successful presentation. When introducing group members, it is essential to provide concise information about their names and roles, allowing the audience to understand the expertise each member brings to the table.

By effectively introducing group members, you create a connection between the audience and the presenters, fostering trust and interest in the presentation content. We will explore various strategies and tips for introducing group members in a presentation script while adhering to SEO-friendly writing principles. Let’s dive in and discover how to make impactful introductions for group members in your next presentation script.

Table of Contents

The Importance Of Introducing Group Members In A Presentation Script

Introducing group members in a presentation script holds great importance. It helps establish credibility and build trust. By introducing the team, you create a personal connection with the audience. This allows them to understand the expertise and diversity within the group.

Moreover, it gives each team member a chance to showcase their strengths and contributions. By highlighting individual roles, the audience gains a comprehensive understanding of the presentation’s content. Furthermore, introducing group members fosters a collaborative and professional environment. It shows that the team is well-prepared and unified in their goals.

Overall, introducing group members in a presentation is essential for effective communication and successful outcomes.

Elements Of A Successful Group Member Introduction

Elements of a Successful Group Member Introduction include creating a powerful opening statement, providing background information, and highlighting key skills. Starting with a captivating statement grabs the audience’s attention. Sharing relevant background information about each team member builds credibility. Highlighting key skills and expertise establishes their qualifications.

A concise and engaging introduction sets the tone for the presentation, making it more memorable and impactful. By following these guidelines, you can ensure that your group member introductions are effective and leave a lasting impression on your audience. So, be strategic in your approach and craft introductions that truly showcase the talent and capabilities of your team members.

Crafting An Engaging Presentation Script

Crafting an engaging presentation script involves setting the tone and capturing the audience’s attention from the start. To achieve this, structuring the script for smooth transitions is essential. Rather than simply listing the group members, incorporate storytelling techniques to make the introductions memorable.

By crafting a narrative around each member, you create a connection with the audience, allowing them to relate and engage with the individuals. Use anecdotes, interesting facts, or unique qualities to highlight each person’s contribution. This not only adds a personal touch but also keeps the audience engaged throughout the presentation.

Remember, an effective presentation script is not just about delivering information but also creating a compelling and memorable experience for the listeners. So, take the opportunity to make your introductions stand out and leave a lasting impression on your audience.

Begin With A Captivating Hook

Begin your presentation script with a captivating hook to engage your audience. Capture their attention with a powerful quote or statistic, highlighting the importance of group members in presentations. Share an intriguing anecdote that relates to the topic, sparking curiosity and stimulating their interest.

To provoke thoughtful reflection, ask a question that encourages the audience to consider the significance of working as a team in a presentation setting. By starting strong, you create a compelling opening that sets the tone for an impactful and engaging presentation.

Introducing Each Group Member

Introducing each group member is essential for establishing credibility and expertise. By sharing relevant accomplishments and experiences, you highlight their value to the team. Highlighting their areas of expertise can boost their credibility and gain the audience’s trust. Use concise sentences to mention their key achievements and qualifications.

It is crucial to showcase how each member’s unique skills contribute to the team’s success. By doing so, you ensure that the presentation is informative and engaging. Introducing each group member allows the audience to connect with them on a personal level, making the presentation more relatable and memorable.

Ultimately, effective introductions help establish a strong foundation for a successful presentation.

Credit: fellow.app

Connecting Group Members To The Presentation Topic

Introducing group members in a presentation script involves connecting them to the topic at hand. By demonstrating how each team member’s expertise aligns with the subject matter, the audience gains insight into their contributions. Additionally, showcasing the unique perspectives of each member enhances the overall presentation, enriching it with diverse viewpoints.

Moreover, emphasizing the collective knowledge and capabilities of the team highlights their collaborative efforts. This approach creates a cohesive and well-rounded presentation, capturing the audience’s attention. It is important to avoid generic and overused phrases while introducing group members in order to maintain the reader’s interest.

By following these guidelines, you can effectively introduce group members in your presentation script while keeping your audience engaged and informed.

Tips For A Fluent And Natural Delivery

Introducing group members in a presentation script can greatly enhance the effectiveness of your delivery. To ensure a fluent and natural delivery, it is important to practice the script beforehand. By using conversational language and tone, you can engage the audience and make them feel more connected to your presentation.

Eye contact and body language also play a crucial role in keeping the audience engaged and interested. Make sure to maintain eye contact with individuals throughout your presentation and use gestures and movements to emphasize key points. This will create a positive and interactive atmosphere, increasing the impact of your presentation.

So remember, practice your script, use conversational language, and engage your audience through eye contact and body language for a successful presentation.

Avoiding Common Mistakes In Group Member Introductions

Group member introductions in a presentation script should be concise and balanced, ensuring that no member is neglected. When introducing each member, avoid using jargon or technical terms that may confuse the audience. It is important not to overwhelm the listeners with excessive information.

Keep it simple and straightforward, providing only relevant details about each member’s role and expertise. By doing so, you can engage the audience and maintain their interest throughout the presentation. Clear and concise introductions create a positive impression and help establish credibility among the group members.

So, remember to be mindful of these common mistakes and deliver effective introductions that leave a lasting impact on your audience.

Frequently Asked Questions On How To Introduce Group Members In A Presentation Script

How do you start a group presentation introduction script.

To start a group presentation introduction, follow these simple steps. Begin with a catchy opening line to grab the audience’s attention. Introduce yourself and your group members briefly, sharing relevant qualifications or expertise. Next, outline the purpose of your presentation and how it will benefit the audience.

Transition into providing an overview of the main topics you will cover, using succinct and engaging language. Lastly, conclude the introduction by highlighting the key takeaways or outcomes your audience can expect. Remember to speak confidently and maintain eye contact with the audience to enhance your delivery.

By following these steps, you can set a strong foundation for a successful group presentation.

How To Introduce Myself And My Group Members In A Presentation Script?

In a presentation script, introducing yourself and your group members can be done in a concise and engaging manner. Begin by stating your name and role within the group. Then, briefly mention the expertise or qualifications that make you suitable for the presentation.

Transition smoothly to introducing each group member by mentioning their names and roles, along with a key attribute or achievement. This will highlight their credibility and relevance to the topic. Remember to focus on the value they bring to the presentation.

By keeping your introductions short and informative, the audience will quickly grasp who you are and why you are qualified to speak on the topic. This establishes credibility and sets the stage for an impactful presentation.

How Do You Introduce Team Members In A Script?

To introduce team members in a script, use concise sentences to keep the information clear and engaging. Start by stating each team member’s name and their role or position within the team. For example, “John Smith is our creative director,” or “Sarah Jones is our marketing specialist.

” Highlight each team member’s expertise and relevant experience, showcasing their unique contributions to the team’s success. Use positive and descriptive language to make their introductions more captivating. Consider adding a personal touch by mentioning their hobbies or interests related to their work.

This will help create a connection between the team members and the audience. Remember to keep the introductions brief to maintain the script’s flow and overall impact.

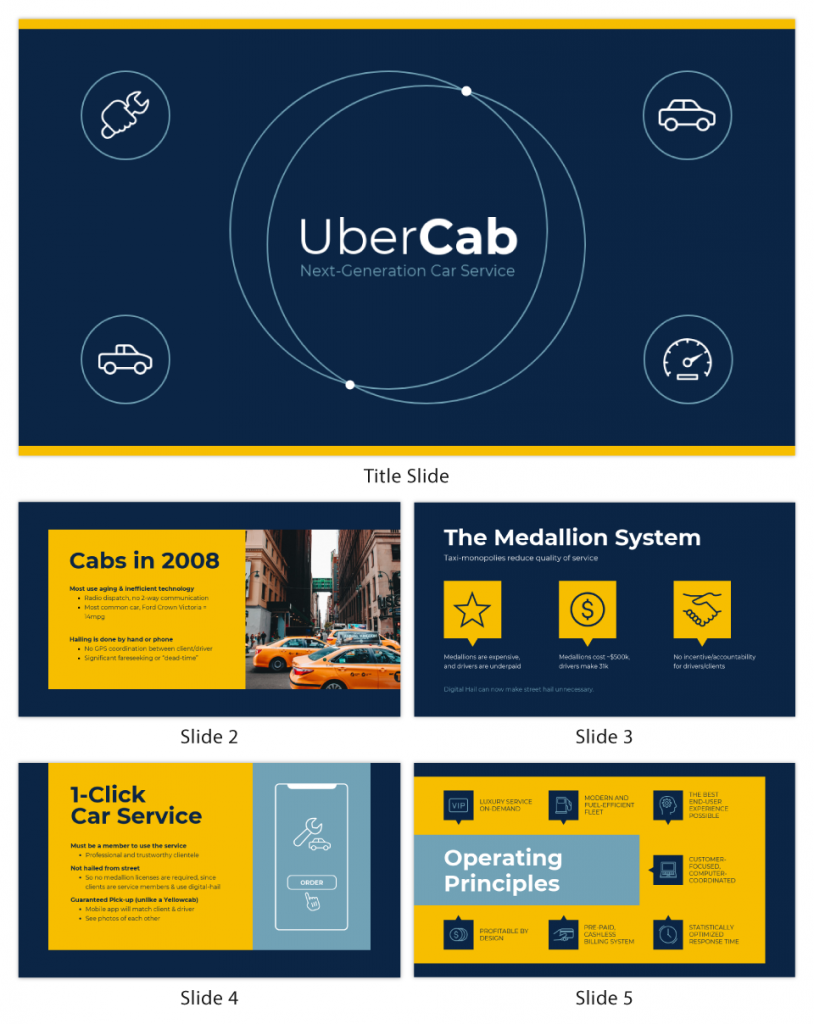

How Do You Introduce A Team Member In Powerpoint?

To introduce a team member in PowerPoint, follow these simple steps. First, open PowerPoint and navigate to the slide where you want to introduce the team member. Then, click on the “Insert” tab in the top menu and select “Text Box” from the options.

In the text box, type the name and position of the team member. Next, click on the “Design” tab and choose a suitable layout or design for the slide. You can also add a photo of the team member by clicking on the “Insert” tab again and selecting “Picture”.

Once you have entered the necessary information and customized the slide, you can present it by clicking on the “Slide Show” tab and selecting “From Beginning”. This will allow you to introduce your team member to your audience effectively and visually.

Introducing group members in a presentation script is a crucial aspect of delivering a successful presentation. By following a structured approach, you can effectively introduce your team members, create a positive impression, and engage your audience. Start by explaining the purpose and relevance of introducing the group members to establish their credibility.

Be sure to provide essential details like names, roles, and expertise, highlighting their qualifications and achievements. Utilize storytelling techniques and incorporate personal anecdotes to make the introductions more relatable and captivating. Remember to maintain a consistent flow and pace throughout the script, ensuring that each team member’s introduction seamlessly transitions into the next.

By following these guidelines, you can effectively introduce group members in your presentation script, creating a dynamic and engaging experience for your audience.

Similar Posts

How to start a conference presentation.

Are you preparing to give a conference presentation but unsure of how to start? Don’t worry, we’ve got you covered! The beginning of your presentation is crucial in capturing your audience’s attention and setting the tone for the rest of your talk. In this article, we will provide you with valuable tips and strategies on…

Why Do We Use Digital Presentation?

We use digital presentations to enhance communication and engage our audience. Digital presentations allow for the effective delivery of information through visually appealing and interactive content, helping to convey complex concepts in a clear and concise manner. By utilizing digital tools such as slideshows, videos, and animations, we are able to captivate our audience’s attention…

What Makes A Good Presentation For A Conference?

Are you ready to captivate your audience at your next conference presentation? In today’s fast-paced world, it is essential to understand what makes a good presentation stand out from the rest. Whether you are a seasoned presenter or just starting out, this topic will provide you with valuable insights and practical tips to wow your…

Transition in A Presentation

Transition in a presentation helps smoothly connect ideas and guide the audience from one topic to another, improving the flow and comprehension. When used effectively, transitions can maintain engagement and facilitate understanding. We will explore the importance of transitions in presentations, discuss different types of transitions, and provide practical tips for mastering their usage. Understanding…

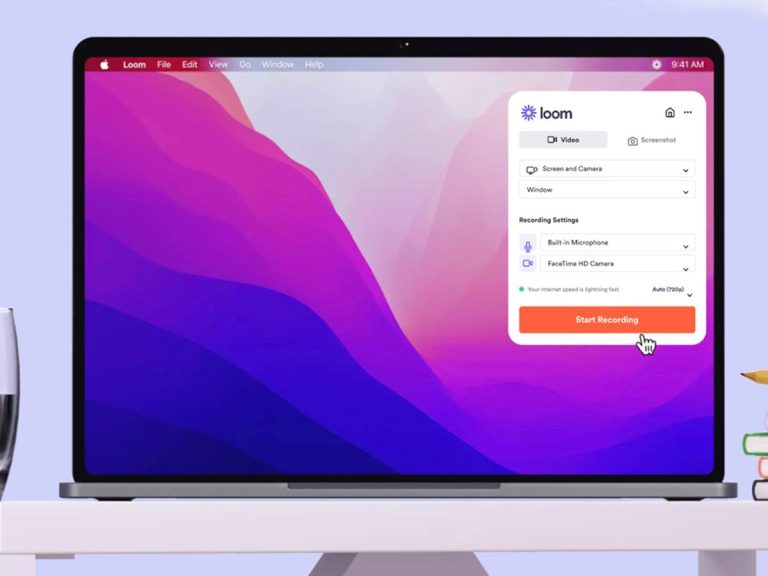

Best Apps to Record Presentation

The best app to record presentations is VEED. With VEED, you can easily customize your Microsoft PowerPoint presentation recordings by selecting different layouts and backgrounds. It allows you to record your screen, webcam, audio, and upload your PowerPoint slides to present while recording. VEED is a user-friendly and efficient app for recording presentations. Why Recording…

Which is the Digital Page of the Presentation?

The digital page of a presentation is the virtual slide or screen where the content is displayed. In today’s digital age, presentations are often created and displayed using software such as PowerPoint or Google Slides, which simulate the traditional physical pages of a presentation. These digital pages allow for the organization and presentation of information…

How To Present With A Group: 14 Expert Tips

Hrideep barot.

- Presentation

If we consider the research and writing part of a presentation, then a group presentation doesn’t seem that different from a single-person presentation.

If you wish to deliver a successful presentation, you still need to put in a fair deal of individual research, writing, and practice. Even for the presenting bit: when you speak, the onus of delivering a great speech, as well as the audience’s attention, is going to be on you.

However, a group presentation is significantly different from a normal presentation.

While you’ll still have to do your own research, the amount of research you’ll have to do will probably be decreased, as the research material will be divided amongst all the members. Practice and delivery of the speech will not be merely an individual thing: you’ll have to work and synch it with the rest of the group.

Moreover, while it might seem that the individual responsibility is going to reduce if you’re delivering a presentation with more than one person, often the case is quite the opposite. This is because if a single person messes up–or simply doesn’t wish to put in as much effort as the others–the repercussions are going to be faced by the entire group.

However, group presentations don’t necessarily have to be a difficult thing. Think of your most favorite sports team: what makes the team the best? What makes them stand out from other teams? How are they successful?

The answer for what makes a sports team the best isn’t much different from what makes a group presentation the best:

Advance planning and division of work, having a strong leader, fostering a sense of comariderie between group members, as well as staying vigilant and supportive on the big day are the key to delivering an awesome group presentation.

And the goal isn’t as tough to achieve as you might think.

Stick till the end of this article to find out!

What Is A Group Presentation?

A group presentation is a collaborative exercise in which a team of speakers works together to create and deliver a presentation on a given topic. The number of members in a group presentation can range from anything between two to over ten! Group presentations are used in a variety of settings like school, workplace, colleges, seminars, etc.

While the task of presenting with a group of people might feel daunting, especially if you identify as a lone wolf, group presentations can be a great learning experience and teach you how to better navigate the task of dealing with a multitude of people with a multitude of opinions and experiences.

By keeping in mind a few things, group presentations can be delivered just as efficiently as single-speaker presentations.

Is A Group Presentation For You?

To decide whether you should deliver a group presentation or not, you need to decide whether the pros of a group presentation outweigh the cons for you.

Group presentations are great because they decrease workload, increase efficiency, improve the quantity and quality of ideas, and also provide you with experience to work in a group setting.

However, there are a few fall-backs to group presentation as well.

Sometimes, a few group members might not work as hard as the other ones, thus increasing the workload on the other members. Also, group members might have different ideas and opinions, which can cause clashes within the group. Coordinating between the group members might be a problem. And if you’re a shy person, you might find it difficult to speak out and voice your opinion in front of other group members.

So, there is no single answer to whether you should do a group presentation or not. Weigh in the pros and cons of doing one before making your decision.

Tips For Delivering A Group Presentation: The Preparation Stage

1. Decide On The Purpose Of Your Presentation

First and foremost, you must determine what is the purpose of your presentation. It might seem like a redundant step, but trust me: it’s not. You’ll be surprised by how different people perceive and understand the same topic.

So, say you’re delivering a research paper on the topic “The Effect Of The Coronavirus Pandemic On Street Animals”, sit down together and ask your group members what each individual person thinks the topic is about and the points they feel we need to include in it.

If possible, one member can jot down all the points that the other speakers make, and once all the members are done talking, you can come to a consensus about what to and what not to include in the presentation.

2. Choose A Presentation Moderator

In the simplest terms, the presentation moderator is the designated “leader” of a group. That is, they’re the one responsible for the effective functioning of the group, and to make sure that the group achieves their shared purpose i.e giving the presentation.

They sort out any potential conflicts in the group, help out other members when they ask for guidance, and also have the final say on important decisions that the group makes. The best and the simplest way to select the presentation moderator is by vote. This will ensure that every member has a say, and avoid any potential conflicts in the future.

3. Divide The Work Fairly

The next step is to divide the work. The best way to do this is to break your presentation into equal parts, and then to assign them to group members. While doing so, you can keep in mind individuals’ preferences, experience, and expertise. For example, if there are three people, you can divide your presentation into three sections: the beginning, the middle, and the end.

Then you can ask which member would feel more comfortable with a particular section, and assign the sections accordingly. In case of any overlap, the individual members can be asked to decide themselves who’s the better fit for the part. Alternatively, if the situation doesn’t seem to resolve, the presentation moderator can step in and assign parts randomly to the members; the members can do this themselves, too.

4 . Do A Member Analysis

To know the individual strengths and weaknesses of group members, it’s important to carry out a member analysis. Not everyone feels comfortable in front of a crowd. Or, someone could be great at building presentations, but not so good with speaking into a mic. On the contrary, a member might be an excellent orator but terrible with technology.

So, in order to efficiently divide the work and to have a seamless presentation, carry out a member analysis beforehand.

5. Individual And Group Practice Are Equally Important

Individual practice is important as it helps you prepare the presentation in solitude, as you would if you were the only speaker. Practicing alone is generally more comfortable, as you do not have to worry about other people watching or judging you.

It also allows you to prepare at your own convenience and time, while for group practice you’ll have to adjust to when it’s convenient for the other members to practice, as well.

Besides, the individual practice also saves the group’s time as each member can simultaneously but separately prep their own part, while group practice sessions are often longer as the other members generally have to pay attention to the speaking member instead of their own bit.

However, it’s essential to do group practice at least three to four times before delivering your presentation. This is important not just for the smooth delivery of the presentation, but also for the group members to grow comfortable with each other.

Group practice sessions also help you time out the total duration of the presentation, have smooth transitions between speakers, avoid repetitions, and also sort out any potential hiccups or fallbacks in the presentation.

6. Perfect The Transitions

A common fallback of group presentations is having awkward transitions between members. Not only will this be an unpleasant experience for the audience, but it might also make you waste precious time.

So, make sure you practice and perfect the transitions before the big day. It doesn’t have to be too long–even a single line will do. What matters is how well you execute it.

7. Bond With The Group Members

Bonding with the group is a great way to enhance the overall presentation experience; both, for yourself as well as the audience. This is because a better bond between the group members will make for the smoother functioning of the group, reduce potential conflicts, make decisions quickly and more easily, and also make the presentation fun!

The audience will also be able to sense, maybe even witness, this camaraderie between the members. They will thus have a better viewing experience.

There are many ways to improve the bonding between group members. Before the presentation, you could go out for dinner, a movie, or even meet up at one location–like somebody’s house–to get to know each other better. Group calls are another option. You could also play an ice-breaker if you’re up for some fun games!

8. Watch Other Group Presentations Together

This is another great way of bonding with the team and also improving your presentation skills as you do so. By listening to other group presentations, you will be able to glean a better idea of how you can better strategize your own presentation. As you watch the presentation, make note of things like the time division, the way the topics are divided, the transition between speakers, etc.

A few presentations you could watch are:

Delivering A Successful Team Presentation

Takeaway: This is a great video to learn how to deliver a great group presentation. As you watch the video, make note of all the different tips that each speaker gives, and also how they incorporate them in their own presentation, which goes on simulatenously with the tips.

Sample Group Presentation: Non-Verbal Communication

Takeaway: This is another great video that depicts how you can deliver a presentation with a group. Notice how the topics are divided, the transition between different speakers, and also the use of visuals in the presentation.

AthleteTranx Team Presentation- 2012 Business Plan Competition

Takeaway: Another great example of a group presentation that you can watch with your own group. In this video, keep a lookout for how the different speakers smoothly transition, their body language, and the way the presentation itself is organized to make it an amazing audience experience.

Tips For Delivering A Group Presentation: The Presentation Stage

1.Introduce All Members

A good idea to keep in mind while delivering a group presentation is to introduce all members at the onset of the presentation. This will familiarize the audience with them, and also work to ease the member’s nerves.

Besides, an introduction will make the members feel more included, and if done correctly, can also give a more shy member a confidence boost. The simplest way of introducing members is to have the person beginning the speech do it. Alternatively, the presentation moderator could do it.

Need some tips on how to introduce people? Check out our article on How To Introduce A Speaker In Any Setting (And Amaze Your Audience).

2. Coordinate Your Dressing

What better way to make people believe that you’re a team than dressing up as one?

Coordinated dressing not only makes the group stand out from the audience, but it can also make the group members feel more like one team.

A general rule of thumb is to dress one level more formally than your audience. Don’t wear your casual clothes: remember that it’s a formal event and your clothing must reflect that. Also, keep in mind individual preferences and beliefs while choosing the clothing.

This is important as if a person is uncomfortably dressed, it can have a negative impact on their performance, which will eventually be detrimental to the group performance.

Confused about what to wear on the presentation day? Check out our article on Guide: Colors To Wear During A Presentation.

3. Make Sure To Incorporate Visual & Audio Aids

Visual elements like photographs, videos, graphs, etc. Are a must in all presentations, group or otherwise. This is because visual aids help the audience better understand the topic, besides making the presentation a better experience overall. Same goes with audio elements, which include things like audio clips, music, background sounds etc.

So, if you wish to have your audience’s attention, make sure to incorporate tons of visual and audio elements in your presentation. You could also divide the kind of visual elements you use between different members: for example, one person could show a short documentary to expand on their point, and the other could make use of memes and animation to add a dose of fun to their part.

4. Pay Attention To What Others Are Saying

Another thing to keep in mind while delivering your speech is to pay attention to what the other speakers are saying. While it might be tempting to tune out others and use the extra time to rehearse your own presentation, it’s not a good idea to do so.

Remember that the audience can see each speaker on the stage. If you don’t look interested, then why should they pay attention? Besides, your lack of attention can make the speaker feel bad: if their own team members aren’t listening to them speaking, does that mean they’re doing a bad job? So, make sure to keep your eyes and ears on your teammate as they deliver their speech.

5. Remember All Speech Parts By Heart

This is a great way to ensure that you have a seamless presentation. One of the primary benefits of having a team to work with is knowing that you can turn to them for help if something goes wrong.

So, it’s important to not just practice and work together but to also be well-versed in what other group members are going to be saying. This will make it easier for you to cue or help someone if they forget their part. Also, if there’s an emergency or if a member is not able to make it to the speech, the other members can easily take their place.

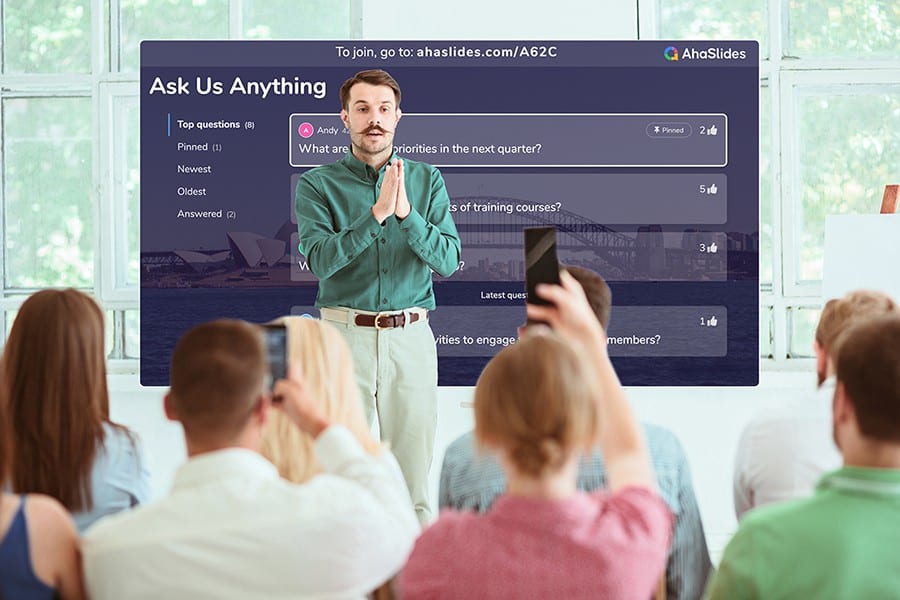

6. Work Together For A Question And Answer Session

Q & A sessions are a common element in most presentations. They might seem daunting to an individual speaker, however, a group setting makes the session much easier. This is because an individual speaker doesn’t have to know everything about the topic.

The presentation moderator can simply refer to the speaker who is the most well-versed about the topic or is best able to answer the question from the group, and they can answer it.

Creative Ideas To Make Use Of Multiple Presenters!

There are many ways by which you can use the fact that there’s not just one single presentator but many to your advantage. A few of them are:

1. Add A Dose Of Fun With Skits!

Adding a dose of creativity to your presentation will greatly enhance its appeal to the audience, and make it more likely that they will remember your presentation in the future!

One way of doing this is by having a short skirt in the opening. This is another great way of introducing the members, and of warming up the audience to them.

A fun skit can not only expand on the topic you’re about to present but will also elevate the audience’s mood, which will improve their attention span as well as their opinion of you! What else could you ask for?

2. Make Them Engage With Cosplay!

Cosplay is another great way of making your presentation stand apart! This can make the presentation more interactive for the audience, as well, and earn you that sought-after dose of chuckling.

It’s not necessary to buy the most expensive costumes or be perfect in your cosplay, either. You can pick an outfit that’s easy to drape over your other outfit, and pick props that are easy to carry as well as versatile so that you can use them in other parts of your presentation as well.

3. Write & Sing A Song Together!

Listen, you don’t have to be a professional singer or composer to do this. You’re not trying to sell a studio album. All you need is a little dose of creativity and some brainstorming, and you can write a song that helps you explain a component of your speech better.

You could even summarize the entire topic in that song, and sing it in the end as a sort of post-credits scene (thank you, Marvel). Alternatively, the song doesn’t necessarily have to explain your speech, but can simply be a surprise element after you’re done with the main part of your speech!

4. Record A Short Film!

If you don’t want to have a live skit, another creative way to add fun to your skit is by recording a short film beforehand and playing it during your presentation. The film doesn’t have to be very long–even a few minutes work.

What matters is the content of the film, and how well-made it is. If not all members wish to act or record themselves, the ones that are not up for it can do the editing and compilation, or even write the script! After all, it’s not just actors that make a film successful: a strong director and writer are just as important!

5. Have A Continuous Story

Another great way to make the presentation seem more connected and seamless is by incorporating a continuous story. You can pick a story–or even make one up–related to your topic and break it up in sections.

Then, assign a section to each speaker. This will not only make the presentation more intriguing but if done right will also hook your audience’s attention and make them anticipate what comes next. Awesome, right?

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

Q. how do i begin a group presentation.

To begin a group presentation, have the moderator or any other group member introduce all other members and the topic that they’ll be speaking on. This might seem like a redundancy, however it is anything but useless.

This gives the chance to the audience to become familiar with the speakers, which is necessary if you want them to grow comfortable with you. Also, prior introduction of members saves the audience’s time, as each speaker will not have to re-introduce themself before driving into their topic.

If each member wishes to individually introduce themselves, then that can be done too. However, make sure that you’ve practiced transitioning between members smoothly, so as to avoid making the switch look awkward.

Next, share a brief summary of what you’re going to be talking about. Like the introduction, you could even split the summary among yourselves, with each speaker describing briefly what they’re going to be talking about. Tell the audience why it’s relevant, and how you’re planning to go about giving the speech. Incorporating attention-grabbing statements is another good idea.

This could be a sneak peek into what’s going to be coming in your presentation, or simply a relevant statement, fact or statistic. Make sure the introduction doesn’t last too long, as you want to keep the audience fresh and primed for the main content of your speech.

For some awesome opening lines, check out our article on 15 Powerful Speech Opening Lines (And How To Create Your Own).

Q. HOW DO I TRANSITION BETWEEN DIFFERENT SPEAKERS?

As mentioned before, having a smooth transition between speakers in the group is imperative to provide the audience with a seamless experience. The abrupt way of doing this would be to simply have the first speaker stop and for the other speaker to begin speaking.

However, a better way to transition would be by using transitional phrases. Pass the baton to the next speaker by introducing them. You could do this by saying something like, “To talk about the next topic we have…” Or something like, “Now I would like to invite…”

After verbally introducing them, it’s also a good idea to motion towards or look towards the new speaker. Also, if you’re the next speaker, it’s always good manners to thank the previous one.

Transitioning is one place where many presentations go wrong. Practicing the transition might seem redundant, but it’s anything but that. In fact, it’s as necessary as the practice of the other elements of your speech. Also, make sure to incorporate both, verbal and non-verbal cues while moving to the next speaker. That is, don’t just say that ‘A’ is going to be speaking now and then walk away.

Make eye contact with the speaker, motion for them towards the podium, or smile at them. That is, both speakers should acknowledge the presence of each other.

Make sure to practice this beforehand too. If you want, you could also have the moderator do the transitioning and introduce all speakers. However, make sure that your transitions are brief, as you don’t want to take up too much time from the main presentation.

Q. HOW DO I END A GROUP PRESENTATION?

For the ending of the presentation, have the moderator or any other group member step forward again. They can provide a quick summary of the presentation, before thanking the audience and asking them if they have any questions.

The moderator doesn’t have to answer all the questions by themselves: the members can pitch in to answer the question that relates to their individual part. If there’s another group presenting after you, the moderator can conclude by verbally introducing them or saying that the next group will take over now.

During the end, you could have all the presenters on the stage together, as this will provide a united front to your audience. If you don’t wish to finish the presentation with a Q & A, you could also end it by a call to action.

Or, you could loop back and make a reference to the opening of your presentation, or the main part of your speech. If you’d set up a question at the beginning, now would be a good time to answer it. This will increase the impact of your speech.

Make sure that the closing words aren’t vague. The audience should know it’s the end of the presentation, and not like you’re keeping them hanging for something more. Make sure to thank and acknowledge your audience, and any other speakers or dignitaries present. Lastly, just like the opening and the transitioning, practice the ending before you step onto the stage!

Want some inspiration for closing lines? Check out our article on 15 Powerful Speech Ending Lines (And Tips To Create Your Own).

Q. HOW DO I INTRODUCE THE NEXT SPEAKER IN A GROUP PRESENTATION?

There are many ways by which you can introduce the next speaker in the presentation. For starters, you could wrap up your presentation by simply summarizing what you said (make sure it’s a brief summary) and then saying the other speaker will take over from this point.

Or, you could finish with your topic and then give a brief introduction of the next speaker and what they’re going to be talking about. The introduction can be simply the name of the speaker, or you could also provide a brief description of them and their achievements if any.

To lighten the mood, you could even add a fun fact about the speaker in your introduction–this is, of course, provided that you’re both comfortable with it. You could also ask for a round of applause to welcome them onto the stage.

However you choose to approach the transition, make sure that your introduction is short, and not more than two minutes at the maximum. Remember that it’s the next speaker’s turn to speak–not yours. If you’re the incoming speaker, make sure to thank the speaker who introduced you. You could also respond to their description or fun fact about you. A smile doesn’t hurt, either!

Conclusion

To sum up, while group presentations might seem daunting at first, if planned and executed properly, they don’t have to be difficult at all! On the contrary, they can make the presentation a more seamless and fun experience overall. By doing thorough preparation in advance, dividing the work properly, as well as staying vigilant and supportive during the presentation, you can execute your next group presentation as easily as an individual project!

Enroll in our transformative 1:1 Coaching Program

Schedule a call with our expert communication coach to know if this program would be the right fit for you

How to Negotiate: The Art of Getting What You Want

10 Hand Gestures That Will Make You More Confident and Efficient

Interrupted while Speaking: 8 Ways to Prevent and Manage Interruptions

- [email protected]

- +91 98203 57888

Get our latest tips and tricks in your inbox always

Copyright © 2023 Frantically Speaking All rights reserved

Kindly drop your contact details so that we can arrange call back

Select Country Afghanistan Albania Algeria AmericanSamoa Andorra Angola Anguilla Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Armenia Aruba Australia Austria Azerbaijan Bahamas Bahrain Bangladesh Barbados Belarus Belgium Belize Benin Bermuda Bhutan Bosnia and Herzegovina Botswana Brazil British Indian Ocean Territory Bulgaria Burkina Faso Burundi Cambodia Cameroon Canada Cape Verde Cayman Islands Central African Republic Chad Chile China Christmas Island Colombia Comoros Congo Cook Islands Costa Rica Croatia Cuba Cyprus Czech Republic Denmark Djibouti Dominica Dominican Republic Ecuador Egypt El Salvador Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Estonia Ethiopia Faroe Islands Fiji Finland France French Guiana French Polynesia Gabon Gambia Georgia Germany Ghana Gibraltar Greece Greenland Grenada Guadeloupe Guam Guatemala Guinea Guinea-Bissau Guyana Haiti Honduras Hungary Iceland India Indonesia Iraq Ireland Israel Italy Jamaica Japan Jordan Kazakhstan Kenya Kiribati Kuwait Kyrgyzstan Latvia Lebanon Lesotho Liberia Liechtenstein Lithuania Luxembourg Madagascar Malawi Malaysia Maldives Mali Malta Marshall Islands Martinique Mauritania Mauritius Mayotte Mexico Monaco Mongolia Montenegro Montserrat Morocco Myanmar Namibia Nauru Nepal Netherlands Netherlands Antilles New Caledonia New Zealand Nicaragua Niger Nigeria Niue Norfolk Island Northern Mariana Islands Norway Oman Pakistan Palau Panama Papua New Guinea Paraguay Peru Philippines Poland Portugal Puerto Rico Qatar Romania Rwanda Samoa San Marino Saudi Arabia Senegal Serbia Seychelles Sierra Leone Singapore Slovakia Slovenia Solomon Islands South Africa South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands Spain Sri Lanka Sudan Suriname Swaziland Sweden Switzerland Tajikistan Thailand Togo Tokelau Tonga Trinidad and Tobago Tunisia Turkey Turkmenistan Turks and Caicos Islands Tuvalu Uganda Ukraine United Arab Emirates United Kingdom United States Uruguay Uzbekistan Vanuatu Wallis and Futuna Yemen Zambia Zimbabwe land Islands Antarctica Bolivia, Plurinational State of Brunei Darussalam Cocos (Keeling) Islands Congo, The Democratic Republic of the Cote d'Ivoire Falkland Islands (Malvinas) Guernsey Holy See (Vatican City State) Hong Kong Iran, Islamic Republic of Isle of Man Jersey Korea, Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Republic of Lao People's Democratic Republic Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Macao Macedonia, The Former Yugoslav Republic of Micronesia, Federated States of Moldova, Republic of Mozambique Palestinian Territory, Occupied Pitcairn Réunion Russia Saint Barthélemy Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan Da Cunha Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia Saint Martin Saint Pierre and Miquelon Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Sao Tome and Principe Somalia Svalbard and Jan Mayen Syrian Arab Republic Taiwan, Province of China Tanzania, United Republic of Timor-Leste Venezuela, Bolivarian Republic of Viet Nam Virgin Islands, British Virgin Islands, U.S.

We use essential cookies to make Venngage work. By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

Manage Cookies

Cookies and similar technologies collect certain information about how you’re using our website. Some of them are essential, and without them you wouldn’t be able to use Venngage. But others are optional, and you get to choose whether we use them or not.

Strictly Necessary Cookies

These cookies are always on, as they’re essential for making Venngage work, and making it safe. Without these cookies, services you’ve asked for can’t be provided.

Show cookie providers

- Google Login

Functionality Cookies

These cookies help us provide enhanced functionality and personalisation, and remember your settings. They may be set by us or by third party providers.

Performance Cookies

These cookies help us analyze how many people are using Venngage, where they come from and how they're using it. If you opt out of these cookies, we can’t get feedback to make Venngage better for you and all our users.

- Google Analytics

Targeting Cookies

These cookies are set by our advertising partners to track your activity and show you relevant Venngage ads on other sites as you browse the internet.

- Google Tag Manager

- Infographics

- Daily Infographics

- Graphic Design

- Graphs and Charts

- Data Visualization

- Human Resources

- Training and Development

- Beginner Guides

Blog Marketing

How To Start a Presentation: 15 Ways to Set the Stage

By Krystle Wong , Jul 25, 2023

The opening moments of your presentation hold immense power – it’s your opportunity to make a lasting impression and captivate your audience.

A strong presentation start acts as a beacon, cutting through the noise and instantly capturing the attention of your listeners. With so much content vying for their focus, a captivating opening ensures that your message stands out and resonates with your audience.

Whether you’re a startup business owner pitching a brilliant idea, a seasoned presenter delivering a persuasive talk or an expert sharing your experience, the start of your presentation can make all the difference. But don’t fret — I’ve got you covered with 15 electrifying ways to kickstart your presentation.

The presentation introduction examples in this article cover everything from self-introduction to how to start a group presentation, building anticipation that leaves the audience eager to delve into the depths of your topic.

Click to jump ahead:

How to start a presentation introduction

15 ways to start a presentation and captivate your audience, common mistakes to avoid in the opening of a presentation, faqs on how to start a presentation, captivate the audience from the get-go.

Presentations can be scary, I know. But even if stage fright hits, you can always fall back on a simple strategy.

Just take a deep breath, introduce yourself and briefly explain the topic of your presentation.

To grab attention at the start, try this opening line: Hello everyone. I am so glad you could join me today. I’m very excited about today’s topic. I’m [Your Name] and I’ll be talking about [Presentation Topic]. Raise your hand if you’ve ever felt overwhelmed by [Challenge related to your topic]. Many of us might have faced challenges with [Challenge related to your topic]. Today, we’ll explore some strategies that’ll help us [Solution that you’re presenting].

Regardless of your mode of presentation , crafting an engaging introduction sets the stage for a memorable presentation.

Let’s dive into some key tips for how to start a presentation speech to help you nail the art of starting with a bang:

Understand your audience

The key to an engaging introduction is to know your audience inside out and give your audience what they want. Tailor your opening to resonate with their specific interests, needs and expectations. Consider what will captivate them and how you can make your presentation relevant to their lives or work.

Use a compelling hook

Grab the audience’s attention from the get-go with a compelling hook. Whether it’s a thought-provoking question, a surprising fact or a gripping story, a powerful opening will immediately pique their curiosity and keep them invested in what you have to say.

State your purpose

Be crystal clear about your subject matter and the purpose of your presentation. In just a few sentences, communicate the main objectives and the value your audience will gain from listening to you. Let them know upfront what to expect and they’ll be more likely to stay engaged throughout.

Introduce yourself and your team

Give a self introduction about who you are such as your job title to establish credibility and rapport with the audience.

Some creative ways to introduce yourself in a presentation would be by sharing a brief and engaging personal story that connects to your topic or the theme of your presentation. This approach instantly makes you relatable and captures the audience’s attention.

Now, let’s talk about — how to introduce team members in a presentation. Before introducing each team member, briefly explain their role or contribution to the project or presentation. This gives the audience an understanding of their relevance and expertise.

Group presentations are also a breeze with the help of Venngage. Our in-editor collaboration tools allow you to edit presentations side by side in real-time. That way, you can seamlessly hare your design with the team for input and make sure everyone is on track.

Maintain enthusiasm

Enthusiasm is contagious! Keep the energy levels up throughout your introduction, conveying a positive and upbeat tone. A vibrant and welcoming atmosphere sets the stage for an exciting presentation and keeps the audience eager to hear more.

Before you think about how to present a topic, think about how to design impactful slides that can leave a lasting impression on the audience. Here are 120+ presentation ideas , design tips, and examples to help you create an awesome slide deck for your next presentation.

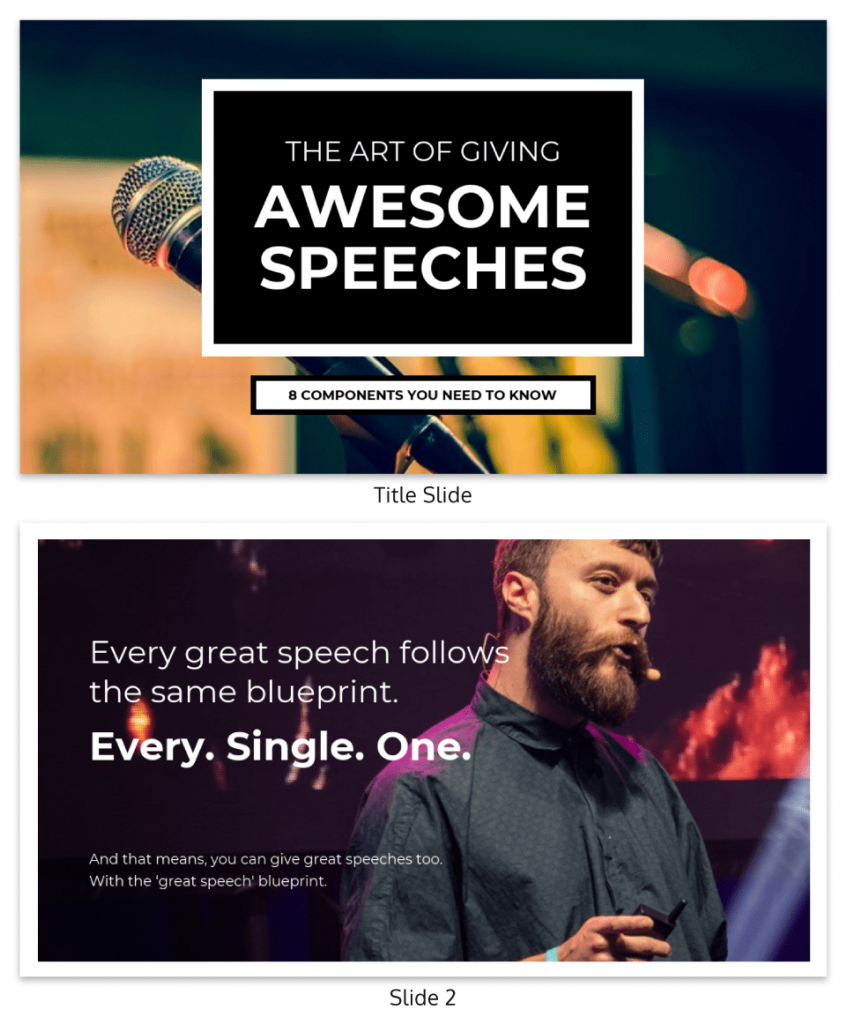

Captivating your audience from the get-go is the key to a successful presentation. Whether you’re a seasoned speaker or a novice taking the stage for the first time, the opening of your presentation sets the tone for the entire talk.

So, let’s get ready to dive into the 15 most creative ways to start a presentation. I promise you these presentation introduction ideas will captivate your audience, leaving them hanging on your every word.

Grab-attention immediately

Ask a thought-provoking question.

Get the audience’s wheels turning by throwing them a thought-provoking question right out of the gate. Make them ponder, wonder and engage their critical thinking muscles from the very start.

Share a surprising statistic or fact

Brace yourself for some wide eyes and dropped jaws! Open your presentation with a jaw-dropping statistic or a mind-blowing fact that’s directly related to your topic. Nothing captures attention like a good ol’ dose of shock and awe.

State a bold statement or challenge

Ready to shake things up? Kick off with a bold and daring statement that sets the stage for your presentation’s epic journey. Boldness has a way of making ears perk up and eyes widen in anticipation!

Engage with a poll or interactive activity

Turn the audience from passive listeners to active participants by kicking off with a fun poll or interactive activity. Get them on their feet, or rather — their fingertips, right from the start!

Venngage’s user-friendly drag-and-drop editor allows you to easily transform your slides into an interactive presentation . Create clickable buttons or navigation elements within your presentation to guide your audience to different sections or external resources.

Enhance engagement by incorporating videos or audio clips directly into your presentation. Venngage supports video and audio embedding, which can add depth to your content.

Begin with an opening phrase that captures attention

Use opening phrases that can help you create a strong connection with your audience and make them eager to hear more about what you have to say. Remember to be confident, enthusiastic and authentic in your delivery to maximize the impact of your presentation.

Here are some effective presentation starting words and phrases that can help you grab your audience’s attention and set the stage for a captivating presentation:

- “Imagine…”

- “Picture this…”

- “Did you know that…”

- “Have you ever wondered…”

- “In this presentation, we’ll explore…”

- “Let’s dive right in and discover…”

- “I’m excited to share with you…”

- “I have a confession to make…”

- “I want to start by telling you a story…”

- “Before we begin, let’s consider…”

- “Have you ever faced the challenge of…”

- “We all know that…”

- “This is a topic close to my heart because…”

- “Over the next [minutes/hours], we’ll cover…”

- “I invite you to journey with me through…”

Build connection and credibility

Begin with a personal connection .

Share a real-life experience or a special connection to the topic at hand. This simple act of opening up creates an instant bond with the audience, turning them into your biggest cheerleaders.

Having the team share their personal experiences is also a good group presentation introduction approach. Team members can share their own stories that are related to the topic to create an emotional connection with your audience.

Tell a relevant story

Start your presentation with a riveting story that hooks your audience and relates to your main message. Stories have a magical way of captivating hearts and minds. Organize your slides in a clear and sequential manner and use visuals that complement your narrative and evoke emotions to engage the audience.

With Venngage, you have access to a vast library of high-quality and captivating stock photography, offering thousands of options to enrich your presentations. The best part? It’s entirely free! Elevate your visual storytelling with stunning images that complement your content, captivate your audience and add a professional touch to your presentation.

Use a powerful quote

Sometimes, all you need is some wise words to work wonders. Begin with a powerful quote from a legendary figure that perfectly fits your presentation’s theme — a dose of inspiration sets the stage for an epic journey.

Build anticipation

Provide a brief outline.

Here’s a good introduction for presentation example if you’re giving a speech at a conference. For longer presentations or conferences with multiple speakers especially, providing an outline helps the audience stay focused on the key takeaways. That way, you can better manage your time and ensure that you cover all the key points without rushing or running out of time.

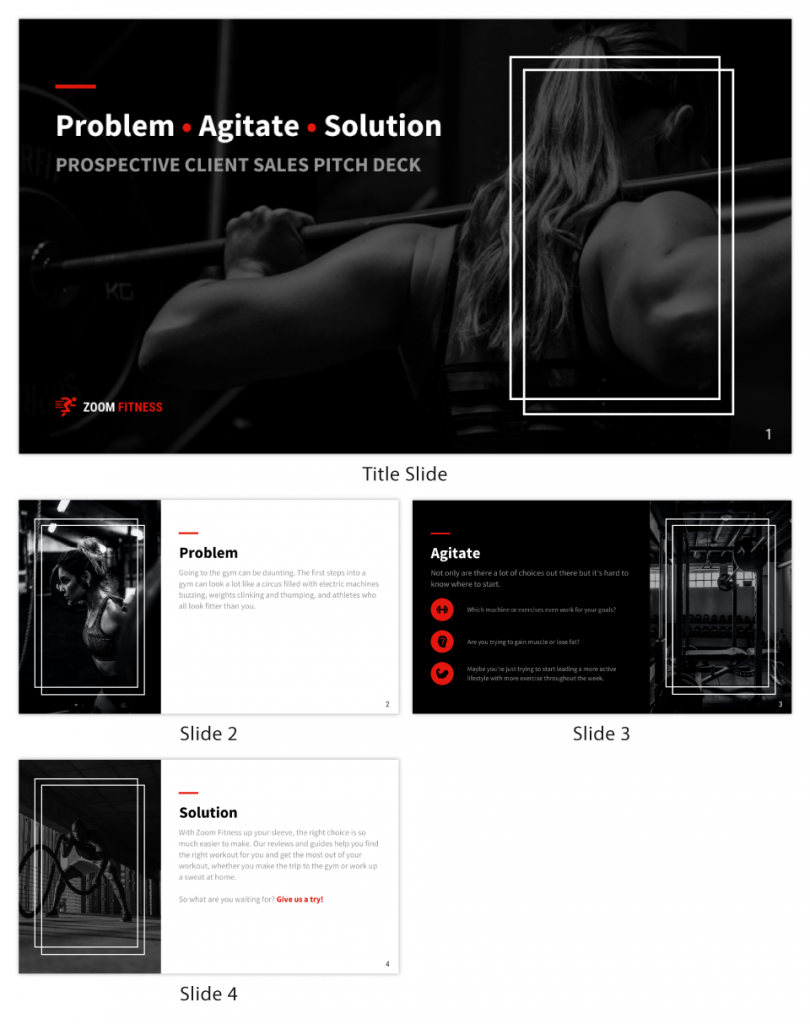

Pose a problem and offer a solution

A great idea on how to start a business presentation is to start by presenting a problem and offering a well-thought-out solution. By addressing their pain points and showcasing your solution, you’ll capture their interest and set the stage for a compelling and successful presentation.

Back up your solution with data, research, or case studies that demonstrate its effectiveness. This can also be a good reporting introduction example that adds credibility to your proposal.

Preparing a pitch deck can be a daunting task but fret not. This guide on the 30+ best pitch deck tips and examples has everything you need to bring on new business partners and win new client contracts. Alternatively, you can also get started by customizing one of our professional pitch deck templates for free.

Incite curiosity in the audience

Utilize visuals or props.

Capture your audience’s gaze by whipping out captivating visuals or props that add an exciting touch to your subject. A well-placed prop or a stunning visual can make your presentation pop like a fireworks show!

That said, you maybe wondering — how can I make my presentation more attractive. A well-designed presentation background instantly captures the audience’s attention and creates a positive first impression. Here are 15 presentation background examples to keep the audience awake to help you get inspired.

Use humor or wit

Sprinkle some humor and wit to spice things up. Cracking a clever joke or throwing in a witty remark can break the ice and create a positively charged atmosphere. If you’re cracking your head on how to start a group presentation, humor is a great way to start a presentation speech.

Get your team members involved in the fun to create a collaborative and enjoyable experience for everyone. Laughter is the perfect way to break the ice and set a positive tone for your presentation!

Invoke emotion

Get those heartstrings tugging! Start with a heartfelt story or example that stirs up emotions and connects with your audience on a personal level. Emotion is the secret sauce to a memorable presentation.

Aside from getting creative with your introduction, a well-crafted and creative presentation can boost your confidence as a presenter. Browse our catalog of creative presentation templates and get started right away!

Use a dramatic pause

A great group presentation example is to start with a powerful moment of silence, like a magician about to reveal their greatest trick. After introducing your team, allow a brief moment of silence. Hold the pause for a few seconds, making it feel deliberate and purposeful. This builds anticipation and curiosity among the audience.

Pique their interest

Share a fun fact or anecdote.

Time for a little fun and games! Kick-off with a lighthearted or fascinating fact that’ll make the audience go, “Wow, really? Tell me more!” A sprinkle of amusement sets the stage for an entertaining ride.

While an introduction for a presentation sets the tone for your speech, a good slide complements your spoken words, helping the audience better understand and remember your message. Check out these 12 best presentation software for 2023 that can aid your next presentation.

The opening moments of a presentation can make or break your entire talk. It’s your chance to grab your audience’s attention, set the tone, and lay the foundation for a successful presentation. However, there are some common pitfalls that speakers often fall into when starting their presentations.

Starting with Apologies

It might be tempting to start with a preemptive apology, especially if you’re feeling nervous or unsure about your presentation. However, beginning with unnecessary apologies or self-deprecating remarks sets a negative tone right from the start. Instead of exuding confidence and credibility, you’re unintentionally undermining yourself and your message.

Reading from Slides

One of the most common blunders in the opening of a PowerPoint presentation is reading directly from your slides or script. While it’s crucial to have a well-structured outline, reciting word-for-word can lead to disengagement and boredom among your audience. Maintain eye contact and connect with your listeners as you speak. Your slides should complement your words, not replace them.

Overwhelming with Information

In the excitement to impress, some presenters bombard their audience with too much information right at the beginning.

Instead of overloading the audience with a sea of data, statistics or technical details that can quickly lead to confusion and disinterest, visualize your data with the help of Venngage. Choose an infographic template that best suits the type of data you want to visualize. Venngage offers a variety of pre-designed templates for charts, graphs, infographics and more.

Ignoring the Audience

It’s easy to get caught up in the content and forget about the people in front of you. Don’t overlook the importance of acknowledging the audience and building a connection with them. Greet them warmly, make eye contact and maintain body language to show genuine interest in their presence. Engage the audience early on by asking a show of hands question or encourage audience participation.

Lack of Clarity

Your audience should know exactly what to expect from your presentation. Starting with a vague or unclear opening leaves them guessing about the purpose and direction of your talk. Clearly communicate the topic and objectives of your presentation right from the beginning. This sets the stage for a focused and coherent message that resonates with your audience.

Simplicity makes it easier for the audience to understand and retain the information presented. Check out our gallery of simple presentation templates to keep your opening concise and relevant.

Skipping the Hook

The opening of your presentation is the perfect opportunity to hook your audience’s attention and keep them engaged. However, some presenters overlook this crucial aspect and dive straight into the content without any intrigue. Craft an attention-grabbing hook that sparks curiosity, poses a thought-provoking question or shares an interesting fact. A compelling opening is like the key that unlocks your audience’s receptivity to the rest of your presentation.

Now that you’ve got the gist of how to introduce a presentation, further brush up your speech with these tips on how to make a persuasive presentation and how to improve your presentation skills to create an engaging presentation .

How can I overcome nervousness at the beginning of a presentation?

To overcome nervousness at the beginning of a presentation, take deep breaths, practice beforehand, and focus on connecting with your audience rather than worrying about yourself.

How long should the opening of a presentation be?

The opening of a presentation should typically be brief, lasting around 1 to 3 minutes, to grab the audience’s attention and set the tone for the rest of the talk.

Should I memorize my presentation’s opening lines?

While it’s helpful to know your opening lines, it’s better to understand the key points and flow naturally to maintain authenticity and flexibility during the presentation.

Should I use slides during the opening of my presentation?

Using slides sparingly during the opening can enhance the message, but avoid overwhelming the audience with too much information early on.

How do I transition smoothly from the opening to the main content of my presentation?

Transition smoothly from the opening to the main content by providing a clear and concise outline of what’s to come, signaling the shift and maintaining a logical flow between topics.

Just as a captivating opening draws your audience in, creating a well-crafted presentation closing has the power to leave a lasting impression. Wrap up in style with these 10 ways to end a presentation .

Presenting virtually? Check out these tips on how to ace your next online presentation .

Captivating your audience from the very beginning is crucial for a successful presentation. The first few moments of your talk can set the tone and determine whether your audience remains engaged throughout or loses interest.

Start with a compelling opening that grabs their attention. You can use a thought-provoking question, a surprising statistic or a powerful quote to pique their curiosity. Alternatively, storytelling can be a potent tool to draw them into your narrative. It’s essential to establish a personal connection early on, whether by sharing a relatable experience or expressing empathy towards their needs and interests.

Lastly, be mindful of your body language and vocal delivery. A confident and engaging speaker can captivate an audience, so make eye contact, use appropriate gestures and vary your tone to convey passion and sincerity.

In conclusion, captivating your audience from the very beginning requires thoughtful preparation, engaging content and a confident delivery. With Venngage’s customizable templates, you can adapt your presentation to suit the preferences and interests of your specific audience, ensuring maximum engagement. Go on and get started today!

5 Powerful Group Presentation Examples + Guide to Nail Your Next Talk

Leah Nguyen • 04 Apr 2024 • 5 min read

A group presentation is a chance to combine your superpowers, brainstorm like mad geniuses, and deliver a presentation that’ll have your audience begging for an encore.

That’s the gist of it.

It can also be a disaster if it’s not done right. Fortunately, we have awesome group presentation examples to help you get the hang of it💪.

Table of Contents

What is a good group presentation, #1. delivering a successful team presentation, #2. athletetrax team presentation, #3. bumble – 1st place – 2017 national business plan competition, #4. 2019 final round yonsei university, #5. 1st place | macy’s case competition, bottom line, frequently asked questions, tips for audience engagement.

- Manager your timing in presentation better

- Learn to introduce team member now

Start in seconds.

Get free templates for your next interactive presentation. Sign up for free and take what you want from the template library!

Here are some key aspects of a good group presentation:

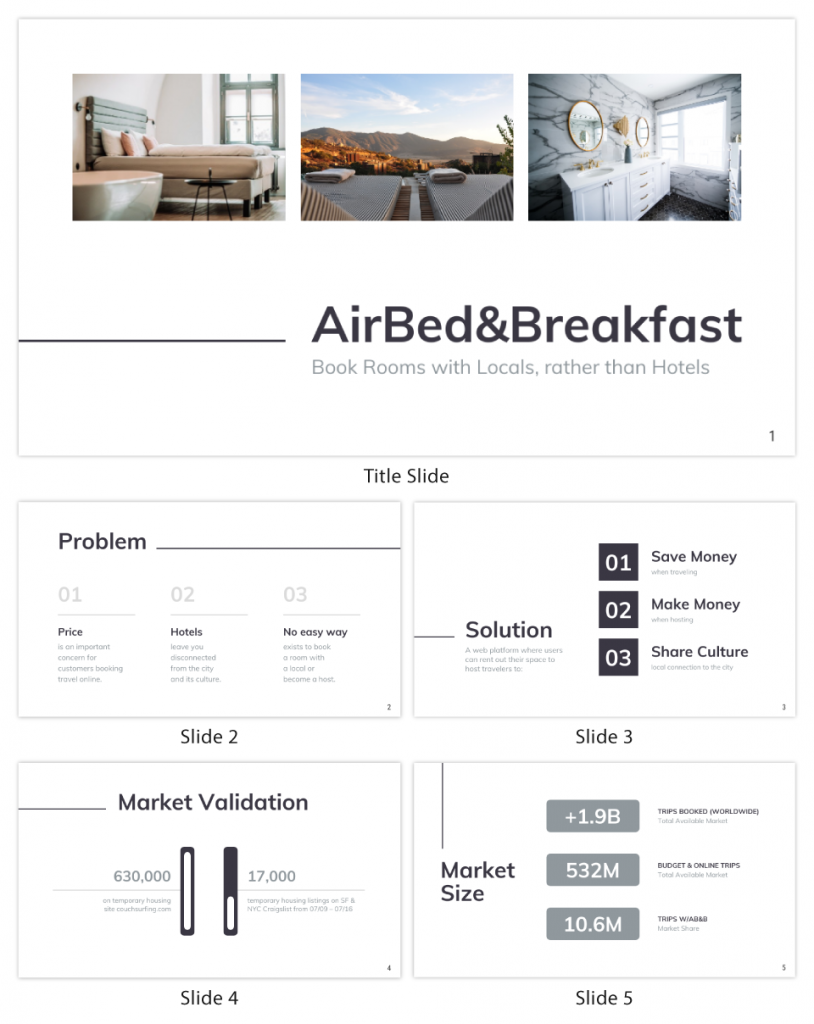

• Organisation – The presentation should follow a logical flow, with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion. An outline or roadmap shown upfront helps guide the audience.

• Visual aids – Use slides, videos, diagrams, etc. to enhance the presentation and keep it engaging. But avoid overly packed slides with too much text. For the sake of convenience of quickly sharing the content, you can attach a QR code directly in your presentation using slides QR code generator for this goal.

• Speaking skills – Speak clearly, at an appropriate pace and volume. Make eye contact with the audience. Limit filler words and verbal tics.

• Participation – All group members should contribute to the presentation in an active and balanced way. They should speak in an integrated, conversational manner. You can also gather attention from your audience by using different interactive features, including spinner wheel live word clouds , live Q&A , online quiz creator and survey tool , to maximize engagement.

🎉 Choose the best Q&A tool with AhaSlides

• Content – The material should be relevant, informative, and at an appropriate level for the audience. Good research and preparation ensure accuracy.

• Interaction – Involve the audience through questions, demonstrations, polls , or activities. This helps keep their attention and facilitates learning.

• Time management – Stay within the allotted time through careful planning and time checks. Have someone in the group monitor the clock.

• Audience focus – Consider the audience’s needs and perspective. Frame the material in a way that is relevant and valuable to them.

• Conclusion – Provide a strong summary of the main points and takeaways. Leave the audience with key messages they’ll remember from your presentation.

🎊 Tips: Icebreaker games | The secret weapon for connecting a new group

Present in powerful and creative visual

Engage your audience in real-time. Let them imprint your presentation in their head with revolutionising interactive slides!

Best Group Presentation Examples

To give you a good idea of what a good group presentation is, here are some specific examples for you to learn from.

The video provides helpful examples and recommendations to illustrate each of these tips for improving team presentations.

The speaker recommends preparing thoroughly as a team, assigning clear roles to each member, and rehearsing multiple times to deliver an effective team presentation that engages the audience.

They speak loudly and clearly, make eye contact with the audience, and avoid reading slides word for word.

The visuals are done properly, with limited text on slides, and relevant images and graphics are used to support key points.

The presentation follows a logical structure, covering the company overview, the problem they are solving, the proposed solution, business model, competition, marketing strategy, finances, and next steps. This makes it easy to follow.

The presenters speak clearly and confidently, make good eye contact with the audience, and avoid simply reading the slides. Their professional demeanor creates a good impression.

They provide a cogent and concise answer to the one question they receive at the end, demonstrating a good understanding of their business plan.

This group nails it with a positive attitude throughout the presentation . Smiles show warmness in opposition to blank stares.

The team cites relevant usage statistics and financial metrics to demonstrate Bumble’s growth potential. This lends credibility to their pitch.

All points are elaborated well, and they switch between members harmoniously.

This group presentation shows that a little stutter initially doesn’t mean it’s the end of the world. They keep going with confidence and carry out the plan flawlessly, which impresses the judging panel.

The team provides clear, supported responses that demonstrate their knowledge and thoughtfulness.

When answering the questions from the judge, they exchange frequent eye contact with them, showing confident manners.

🎉 Tips: Divide your team into smaller groups for them to practice presenting better!

In this video , we can see instantly that each member of the group takes control of the stage they present naturally. They move around, exuding an aura of confidence in what they’re saying.

For an intricate topic like diversity and inclusion, they made their points well-put by backing them up with figures and data.

🎊 Tips: Rate your presentation by effective rating scale tool , to make sure that everyone’s satisfied with your presentation!

We hope these group presentation examples will help you and your team members achieve clear communication, organisation, and preparation, along with the ability to deliver the message in an engaging and compelling manner. These factors all contribute to a good group presentation that wow the audience.

More to read:

- 💡 10 Interactive Presentation Techniques for Engagement

- 💡 220++ Easy Topics for Presentation of all Ages

- 💡 Complete Guide to Interactive Presentations

What is a group presentation?

A group presentation is a presentation given by multiple people, typically two or more, to an audience. Group presentations are common in academic, business, and organisational settings.

How do you make a group presentation?

To make an effective group presentation, clearly define the objective, assign roles among group members for researching, creating slides, and rehearsing, create an outline with an introduction, 3-5 key points, and a conclusion, and gather relevant facts and examples to support each point, include meaningful visual aids on slides while limiting text, practice your full presentation together and provide each other with feedback, conclude strongly by summarising key takeaways.

Leah Nguyen

Words that convert, stories that stick. I turn complex ideas into engaging narratives - helping audiences learn, remember, and take action.

More from AhaSlides

- Student Login:

How to Organize Your Introduction for a Presentation [+ FREE Presentation Checklist]

May 1, 2018 | Business Professional English , Free Resource , Public Speaking & Presentations

This lesson on how to organize your introduction for a presentation in English has been updated since its original posting in 2016 and a video has been added.

Getting ready to present in English? Here’s how to make sure your introduction for a presentation in English is successful.

But first… When you think about a presentation, I know you’re thinking about something like a TED video or a presentation at a conference. You’re thinking about a speech, with PowerPoint slides and a big audience.

But did you know we use the same skills when we share new information or ideas with our work colleagues? Or when we tell stories to our friends and family? The situation or speaking task may be different but we still use the same skills.

When presenting information or telling stories, we need to:

- Capture a listener’s attention

- Share information, ideas, or opinions

- Give the important details

- Make your information memorable

- Get your audience (family, friends, colleagues or strangers) to agree, to take action, to change their mind, etc.

So today you’re going to learn how to take the first big step in your English presentation: how to start with a great introduction.

The introduction is the most important part of your presentation. It is the first impression you’ll make on your audience. It’s your first opportunity to get their attention. You want them to trust you and listen to you right away.

However, that first moment when you start to speak is often the hardest. Knowing how to best prepare and knowing what to say will help you feel confident and ready to say that first word and start your presentation in English.

Be sure to include these 5 things in your inroduction.

Lesson by Annemarie

How to Organize Your Introduction for a Presentation in English and Key Phrases to Use

Organize Your Introduction Correctly

Okay, first let’s focus on what you need to include in your English introduction. Think of this as your formula for a good introduction. Using this general outline for your introduction will help you prepare. It will also help your audience know who you are, why you’re an expert, and what to expect from your presentation.

Use this general outline for your next presentation:

- Welcome your audience and introduce yourself

- Capture their attention

- Identify your number one goal or topic of presentation

- Give a quick outline of your presentation

- Provide instructions for how to ask questions (if appropriate for your situation)

Use Common Language to Make Your Introduction Easy to Understand

Great, now you have the general outline of an introduction for a speech or presentation in English. So let’s focus on some of the key expressions you can use for each step. This will help you think about what to say and how to say it so you can sound confident and prepared in your English presentation.

“The introduction is the most important part of your presentation. It is the first impression you’ll make on your audience. It’s your first opportunity to get their attention. You want them to trust you and listen to you right away.”

Welcome Your Audience & Introduction

It is polite to start with a warm welcome and to introduce yourself. Everyone in the audience will want to know who you are. Your introduction should include your name and job position or the reason you are an expert on your topic. The more the audience trusts you, the more they listen.

- Welcome to [name of company or event]. My name is [name] and I am the [job title or background information].

- Thank you for coming today. I’m [name] and I’m looking forward to talking with you today about [your topic].

- Good morning/afternoon ladies and gentlemen. I’d like to quickly introduce myself. I am [name] from [company or position]. (formal)

- On behalf of [name of company], I’d like to welcome you today. For those of you who don’t already know me, my name is [name] and I am [job title or background]. (formal)

- Hi everyone. I’m [name and background]. I’m glad to be here with you today. Now let’s get started. (informal)

Capture Their Attention

For more information about how to best capture your audience’s attention and why, please see the next session below. However, here are a few good phrases to get you started.

- Did you know that [insert an interesting fact or shocking statement]?

- Have you ever heard that [insert interesting fact or shocking statement]?

- Before I start, I’d like to share a quick story about [tell your story]…

- I remember [tell your story, experience or memory]…

- When I started preparing for this talk, I was reminded of [tell your story, share your quote or experience]…

Identify Your Goal or Topic of Presentation

At this stage, you want to be clear with your audience about your primary topic or goal. Do you want your audience to take action after your talk? Is it a topic everyone is curious about (or should be curious about)? This should be just one or two sentences and it should be very clear.

- This morning I’d like to present our new [product or service].

- Today I’d like to discuss…

- Today I’d like to share with you…

- What I want to share with you is…

- My goal today is to help you understand…

- During my talk this morning/afternoon, I’ll provide you with some background on [main topic] and why it is important to you.

- I will present my findings on…

- By the end of my presentation, I’d like for you to know…

- I aim to prove to you / change your mind about…

- I’d like to take this opportunity to talk about…

- As you know, this morning/afternoon I’ll be discussing…

Outline Your Presentation

You may have heard this about presentations in English before:

First, tell me what you’re going to tell me. Then tell me. And finally, tell me what you told me.

It sounds crazy and weird, but it’s true. This is how we structure presentations in English. So today we’re focusing on the “First, tell me what you’re going to tell me” for your introduction. This means you should outline the key points or highlights of your topic.

This prepares your listens and helps to get their attention. It will also help them follow your presentation and stay focused. Here are some great phrases to help you do that.

- First, I’m going to present… Then I’ll share with you… Finally, I’ll ask you to…

- The next thing I’ll share with you is…

- In the next section, I’ll show you…

- Today I will be covering these 3 (or 5) key points…

- In this presentation, we will discuss/evaluate…

- By the end of this presentation, you’ll be able to…

- My talk this morning is divided into [number] main sections… First, second, third… Finally…

On Asking Questions

You want to be sure to let you audience know when and how it is appropriate for them to ask you questions. For example, is the presentation informal and is it okay for someone to interrupt you with a question? Or do you prefer for everyone to wait until the end of the presentation to ask questions?

- If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to interrupt me. I’m happy to answer any questions as we go along.

- Feel free to ask any questions, however, I do ask that you wait until the end of the presentation to ask.

- There will be plenty of time for questions at the end.

- Are there any questions at this point? If not, we’ll keep going.

- I would be happy to answer any questions you may have now.

Capture Your Audience’s Attention

Do you feel unsure about how to capture the attention of your audience? Don’t worry! Here are some common examples used in English-speaking culture for doing it perfectly!

Two of the most famous speakers in the English-speaking world are Steve Jobs and Oprah Winfrey. While Steve Jobs is no longer living, people still love to watch his speeches and presentations online. Oprah is so famous that no matter what she does, people are excited to see her and listen to her.

BUT, if you listen to a speech by Steve Jobs or Oprah Winfrey, they still work to get your attention!

The don’t start with a list of numbers or data. They don’t begin with a common fact or with the title of the presentation. No – they do much more.