Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Write a Research Paper Introduction (with Examples)

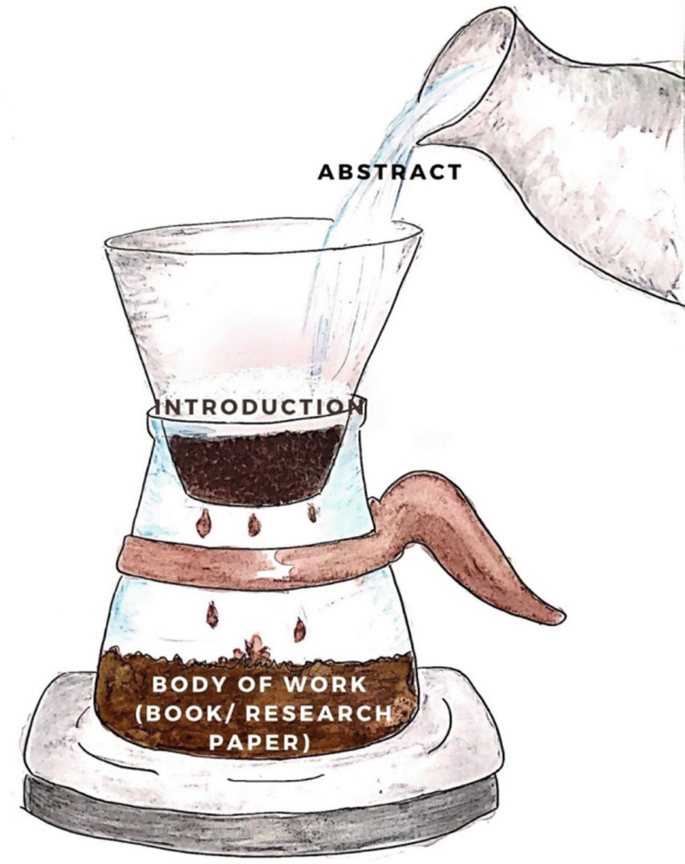

The research paper introduction section, along with the Title and Abstract, can be considered the face of any research paper. The following article is intended to guide you in organizing and writing the research paper introduction for a quality academic article or dissertation.

The research paper introduction aims to present the topic to the reader. A study will only be accepted for publishing if you can ascertain that the available literature cannot answer your research question. So it is important to ensure that you have read important studies on that particular topic, especially those within the last five to ten years, and that they are properly referenced in this section. 1 What should be included in the research paper introduction is decided by what you want to tell readers about the reason behind the research and how you plan to fill the knowledge gap. The best research paper introduction provides a systemic review of existing work and demonstrates additional work that needs to be done. It needs to be brief, captivating, and well-referenced; a well-drafted research paper introduction will help the researcher win half the battle.

The introduction for a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your research topic

- Capture reader interest

- Summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Define your specific research problem and problem statement

- Highlight the novelty and contributions of the study

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The research paper introduction can vary in size and structure depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or is a review paper. Some research paper introduction examples are only half a page while others are a few pages long. In many cases, the introduction will be shorter than all of the other sections of your paper; its length depends on the size of your paper as a whole.

- Break through writer’s block. Write your research paper introduction with Paperpal Copilot

Table of Contents

What is the introduction for a research paper, why is the introduction important in a research paper, craft a compelling introduction section with paperpal. try now, 1. introduce the research topic:, 2. determine a research niche:, 3. place your research within the research niche:, craft accurate research paper introductions with paperpal. start writing now, frequently asked questions on research paper introduction, key points to remember.

The introduction in a research paper is placed at the beginning to guide the reader from a broad subject area to the specific topic that your research addresses. They present the following information to the reader

- Scope: The topic covered in the research paper

- Context: Background of your topic

- Importance: Why your research matters in that particular area of research and the industry problem that can be targeted

The research paper introduction conveys a lot of information and can be considered an essential roadmap for the rest of your paper. A good introduction for a research paper is important for the following reasons:

- It stimulates your reader’s interest: A good introduction section can make your readers want to read your paper by capturing their interest. It informs the reader what they are going to learn and helps determine if the topic is of interest to them.

- It helps the reader understand the research background: Without a clear introduction, your readers may feel confused and even struggle when reading your paper. A good research paper introduction will prepare them for the in-depth research to come. It provides you the opportunity to engage with the readers and demonstrate your knowledge and authority on the specific topic.

- It explains why your research paper is worth reading: Your introduction can convey a lot of information to your readers. It introduces the topic, why the topic is important, and how you plan to proceed with your research.

- It helps guide the reader through the rest of the paper: The research paper introduction gives the reader a sense of the nature of the information that will support your arguments and the general organization of the paragraphs that will follow. It offers an overview of what to expect when reading the main body of your paper.

What are the parts of introduction in the research?

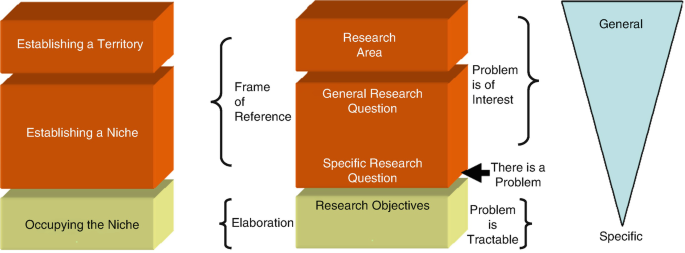

A good research paper introduction section should comprise three main elements: 2

- What is known: This sets the stage for your research. It informs the readers of what is known on the subject.

- What is lacking: This is aimed at justifying the reason for carrying out your research. This could involve investigating a new concept or method or building upon previous research.

- What you aim to do: This part briefly states the objectives of your research and its major contributions. Your detailed hypothesis will also form a part of this section.

How to write a research paper introduction?

The first step in writing the research paper introduction is to inform the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening statement. The second step involves establishing the kinds of research that have been done and ending with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to address. Finally, the research paper introduction clarifies how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses. If your research involved testing hypotheses, these should be stated along with your research question. The hypothesis should be presented in the past tense since it will have been tested by the time you are writing the research paper introduction.

The following key points, with examples, can guide you when writing the research paper introduction section:

- Highlight the importance of the research field or topic

- Describe the background of the topic

- Present an overview of current research on the topic

Example: The inclusion of experiential and competency-based learning has benefitted electronics engineering education. Industry partnerships provide an excellent alternative for students wanting to engage in solving real-world challenges. Industry-academia participation has grown in recent years due to the need for skilled engineers with practical training and specialized expertise. However, from the educational perspective, many activities are needed to incorporate sustainable development goals into the university curricula and consolidate learning innovation in universities.

- Reveal a gap in existing research or oppose an existing assumption

- Formulate the research question

Example: There have been plausible efforts to integrate educational activities in higher education electronics engineering programs. However, very few studies have considered using educational research methods for performance evaluation of competency-based higher engineering education, with a focus on technical and or transversal skills. To remedy the current need for evaluating competencies in STEM fields and providing sustainable development goals in engineering education, in this study, a comparison was drawn between study groups without and with industry partners.

- State the purpose of your study

- Highlight the key characteristics of your study

- Describe important results

- Highlight the novelty of the study.

- Offer a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

Example: The study evaluates the main competency needed in the applied electronics course, which is a fundamental core subject for many electronics engineering undergraduate programs. We compared two groups, without and with an industrial partner, that offered real-world projects to solve during the semester. This comparison can help determine significant differences in both groups in terms of developing subject competency and achieving sustainable development goals.

Write a Research Paper Introduction in Minutes with Paperpal

Paperpal Copilot is a generative AI-powered academic writing assistant. It’s trained on millions of published scholarly articles and over 20 years of STM experience. Paperpal Copilot helps authors write better and faster with:

- Real-time writing suggestions

- In-depth checks for language and grammar correction

- Paraphrasing to add variety, ensure academic tone, and trim text to meet journal limits

With Paperpal Copilot, create a research paper introduction effortlessly. In this step-by-step guide, we’ll walk you through how Paperpal transforms your initial ideas into a polished and publication-ready introduction.

How to use Paperpal to write the Introduction section

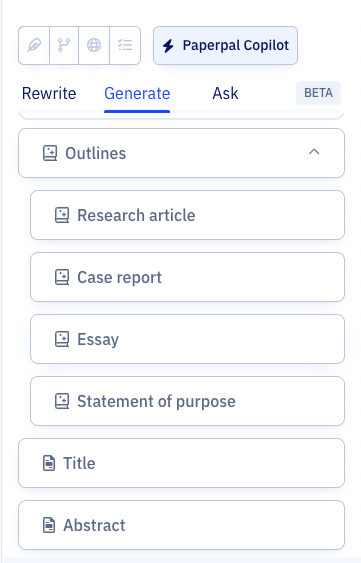

Step 1: Sign up on Paperpal and click on the Copilot feature, under this choose Outlines > Research Article > Introduction

Step 2: Add your unstructured notes or initial draft, whether in English or another language, to Paperpal, which is to be used as the base for your content.

Step 3: Fill in the specifics, such as your field of study, brief description or details you want to include, which will help the AI generate the outline for your Introduction.

Step 4: Use this outline and sentence suggestions to develop your content, adding citations where needed and modifying it to align with your specific research focus.

Step 5: Turn to Paperpal’s granular language checks to refine your content, tailor it to reflect your personal writing style, and ensure it effectively conveys your message.

You can use the same process to develop each section of your article, and finally your research paper in half the time and without any of the stress.

The purpose of the research paper introduction is to introduce the reader to the problem definition, justify the need for the study, and describe the main theme of the study. The aim is to gain the reader’s attention by providing them with necessary background information and establishing the main purpose and direction of the research.

The length of the research paper introduction can vary across journals and disciplines. While there are no strict word limits for writing the research paper introduction, an ideal length would be one page, with a maximum of 400 words over 1-4 paragraphs. Generally, it is one of the shorter sections of the paper as the reader is assumed to have at least a reasonable knowledge about the topic. 2 For example, for a study evaluating the role of building design in ensuring fire safety, there is no need to discuss definitions and nature of fire in the introduction; you could start by commenting upon the existing practices for fire safety and how your study will add to the existing knowledge and practice.

When deciding what to include in the research paper introduction, the rest of the paper should also be considered. The aim is to introduce the reader smoothly to the topic and facilitate an easy read without much dependency on external sources. 3 Below is a list of elements you can include to prepare a research paper introduction outline and follow it when you are writing the research paper introduction. Topic introduction: This can include key definitions and a brief history of the topic. Research context and background: Offer the readers some general information and then narrow it down to specific aspects. Details of the research you conducted: A brief literature review can be included to support your arguments or line of thought. Rationale for the study: This establishes the relevance of your study and establishes its importance. Importance of your research: The main contributions are highlighted to help establish the novelty of your study Research hypothesis: Introduce your research question and propose an expected outcome. Organization of the paper: Include a short paragraph of 3-4 sentences that highlights your plan for the entire paper

Cite only works that are most relevant to your topic; as a general rule, you can include one to three. Note that readers want to see evidence of original thinking. So it is better to avoid using too many references as it does not leave much room for your personal standpoint to shine through. Citations in your research paper introduction support the key points, and the number of citations depend on the subject matter and the point discussed. If the research paper introduction is too long or overflowing with citations, it is better to cite a few review articles rather than the individual articles summarized in the review. A good point to remember when citing research papers in the introduction section is to include at least one-third of the references in the introduction.

The literature review plays a significant role in the research paper introduction section. A good literature review accomplishes the following: Introduces the topic – Establishes the study’s significance – Provides an overview of the relevant literature – Provides context for the study using literature – Identifies knowledge gaps However, remember to avoid making the following mistakes when writing a research paper introduction: Do not use studies from the literature review to aggressively support your research Avoid direct quoting Do not allow literature review to be the focus of this section. Instead, the literature review should only aid in setting a foundation for the manuscript.

Remember the following key points for writing a good research paper introduction: 4

- Avoid stuffing too much general information: Avoid including what an average reader would know and include only that information related to the problem being addressed in the research paper introduction. For example, when describing a comparative study of non-traditional methods for mechanical design optimization, information related to the traditional methods and differences between traditional and non-traditional methods would not be relevant. In this case, the introduction for the research paper should begin with the state-of-the-art non-traditional methods and methods to evaluate the efficiency of newly developed algorithms.

- Avoid packing too many references: Cite only the required works in your research paper introduction. The other works can be included in the discussion section to strengthen your findings.

- Avoid extensive criticism of previous studies: Avoid being overly critical of earlier studies while setting the rationale for your study. A better place for this would be the Discussion section, where you can highlight the advantages of your method.

- Avoid describing conclusions of the study: When writing a research paper introduction remember not to include the findings of your study. The aim is to let the readers know what question is being answered. The actual answer should only be given in the Results and Discussion section.

To summarize, the research paper introduction section should be brief yet informative. It should convince the reader the need to conduct the study and motivate him to read further. If you’re feeling stuck or unsure, choose trusted AI academic writing assistants like Paperpal to effortlessly craft your research paper introduction and other sections of your research article.

1. Jawaid, S. A., & Jawaid, M. (2019). How to write introduction and discussion. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia, 13(Suppl 1), S18.

2. Dewan, P., & Gupta, P. (2016). Writing the title, abstract and introduction: Looks matter!. Indian pediatrics, 53, 235-241.

3. Cetin, S., & Hackam, D. J. (2005). An approach to the writing of a scientific Manuscript1. Journal of Surgical Research, 128(2), 165-167.

4. Bavdekar, S. B. (2015). Writing introduction: Laying the foundations of a research paper. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 63(7), 44-6.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Scientific Writing Style Guides Explained

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

- 8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

Practice vs. Practise: Learn the Difference

Academic paraphrasing: why paperpal’s rewrite should be your first choice , you may also like, ai in education: it’s time to change the..., is it ethical to use ai-generated abstracts without..., what are journal guidelines on using generative ai..., quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives, what is an academic paper types and elements , should you use ai tools like chatgpt for..., publish research papers: 9 steps for successful publications , what are the different types of research papers, how to make translating academic papers less challenging, self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how....

Microsoft 365 Life Hacks > Writing > How to write an introduction for a research paper

How to write an introduction for a research paper

Beginnings are hard. Beginning a research paper is no exception. Many students—and pros—struggle with how to write an introduction for a research paper.

This short guide will describe the purpose of a research paper introduction and how to create a good one.

What is an introduction for a research paper?

Introductions to research papers do a lot of work.

It may seem obvious, but introductions are always placed at the beginning of a paper. They guide your reader from a general subject area to the narrow topic that your paper covers. They also explain your paper’s:

- Scope: The topic you’ll be covering

- Context: The background of your topic

- Importance: Why your research matters in the context of an industry or the world

Your introduction will cover a lot of ground. However, it will only be half of a page to a few pages long. The length depends on the size of your paper as a whole. In many cases, the introduction will be shorter than all of the other sections of your paper.

Write with Confidence using Editor

Elevate your writing with real-time, intelligent assistance

Why is an introduction vital to a research paper?

The introduction to your research paper isn’t just important. It’s critical.

Your readers don’t know what your research paper is about from the title. That’s where your introduction comes in. A good introduction will:

- Help your reader understand your topic’s background

- Explain why your research paper is worth reading

- Offer a guide for navigating the rest of the piece

- Pique your reader’s interest

Without a clear introduction, your readers will struggle. They may feel confused when they start reading your paper. They might even give up entirely. Your introduction will ground them and prepare them for the in-depth research to come.

What should you include in an introduction for a research paper?

Research paper introductions are always unique. After all, research is original by definition. However, they often contain six essential items. These are:

- An overview of the topic. Start with a general overview of your topic. Narrow the overview until you address your paper’s specific subject. Then, mention questions or concerns you had about the case. Note that you will address them in the publication.

- Prior research. Your introduction is the place to review other conclusions on your topic. Include both older scholars and modern scholars. This background information shows that you are aware of prior research. It also introduces past findings to those who might not have that expertise.

- A rationale for your paper. Explain why your topic needs to be addressed right now. If applicable, connect it to current issues. Additionally, you can show a problem with former theories or reveal a gap in current research. No matter how you do it, a good rationale will interest your readers and demonstrate why they must read the rest of your paper.

- Describe the methodology you used. Recount your processes to make your paper more credible. Lay out your goal and the questions you will address. Reveal how you conducted research and describe how you measured results. Moreover, explain why you made key choices.

- A thesis statement. Your main introduction should end with a thesis statement. This statement summarizes the ideas that will run through your entire research article. It should be straightforward and clear.

- An outline. Introductions often conclude with an outline. Your layout should quickly review what you intend to cover in the following sections. Think of it as a roadmap, guiding your reader to the end of your paper.

These six items are emphasized more or less, depending on your field. For example, a physics research paper might emphasize methodology. An English journal article might highlight the overview.

Three tips for writing your introduction

We don’t just want you to learn how to write an introduction for a research paper. We want you to learn how to make it shine.

There are three things you can do that will make it easier to write a great introduction. You can:

- Write your introduction last. An introduction summarizes all of the things you’ve learned from your research. While it can feel good to get your preface done quickly, you should write the rest of your paper first. Then, you’ll find it easy to create a clear overview.

- Include a strong quotation or story upfront. You want your paper to be full of substance. But that doesn’t mean it should feel boring or flat. Add a relevant quotation or surprising anecdote to the beginning of your introduction. This technique will pique the interest of your reader and leave them wanting more.

- Be concise. Research papers cover complex topics. To help your readers, try to write as clearly as possible. Use concise sentences. Check for confusing grammar or syntax . Read your introduction out loud to catch awkward phrases. Before you finish your paper, be sure to proofread, too. Mistakes can seem unprofessional.

Get started with Microsoft 365

It’s the Office you know, plus the tools to help you work better together, so you can get more done—anytime, anywhere.

Topics in this article

More articles like this one.

What is independent publishing?

Avoid the hassle of shopping your book around to publishing houses. Publish your book independently and understand the benefits it provides for your as an author.

What are literary tropes?

Engage your audience with literary tropes. Learn about different types of literary tropes, like metaphors and oxymorons, to elevate your writing.

What are genre tropes?

Your favorite genres are filled with unifying tropes that can define them or are meant to be subverted.

What is literary fiction?

Define literary fiction and learn what sets it apart from genre fiction.

Everything you need to achieve more in less time

Get powerful productivity and security apps with Microsoft 365

Explore Other Categories

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How to Write an Introduction for a Research Paper

Table of Contents

Writing an introduction for a research paper is a critical element of your paper, but it can seem challenging to encapsulate enormous amount of information into a concise form. The introduction of your research paper sets the tone for your research and provides the context for your study. In this article, we will guide you through the process of writing an effective introduction that grabs the reader's attention and captures the essence of your research paper.

Understanding the Purpose of a Research Paper Introduction

The introduction acts as a road map for your research paper, guiding the reader through the main ideas and arguments. The purpose of the introduction is to present your research topic to the readers and provide a rationale for why your study is relevant. It helps the reader locate your research and its relevance in the broader field of related scientific explorations. Additionally, the introduction should inform the reader about the objectives and scope of your study, giving them an overview of what to expect in the paper. By including a comprehensive introduction, you establish your credibility as an author and convince the reader that your research is worth their time and attention.

Key Elements to Include in Your Introduction

When writing your research paper introduction, there are several key elements you should include to ensure it is comprehensive and informative.

- A hook or attention-grabbing statement to capture the reader's interest. It can be a thought-provoking question, a surprising statistic, or a compelling anecdote that relates to your research topic.

- A brief overview of the research topic and its significance. By highlighting the gap in existing knowledge or the problem your research aims to address, you create a compelling case for the relevance of your study.

- A clear research question or problem statement. This serves as the foundation of your research and guides the reader in understanding the unique focus of your study. It should be concise, specific, and clearly articulated.

- An outline of the paper's structure and main arguments, to help the readers navigate through the paper with ease.

Preparing to Write Your Introduction

Before diving into writing your introduction, it is essential to prepare adequately. This involves 3 important steps:

- Conducting Preliminary Research: Immerse yourself in the existing literature to develop a clear research question and position your study within the academic discourse.

- Identifying Your Thesis Statement: Define a specific, focused, and debatable thesis statement, serving as a roadmap for your paper.

- Considering Broader Context: Reflect on the significance of your research within your field, understanding its potential impact and contribution.

By engaging in these preparatory steps, you can ensure that your introduction is well-informed, focused, and sets the stage for a compelling research paper.

Structuring Your Introduction

Now that you have prepared yourself to tackle the introduction, it's time to structure it effectively. A well-structured introduction will engage the reader from the beginning and provide a logical flow to your research paper.

Starting with a Hook

Begin your introduction with an attention-grabbing hook that captivates the reader's interest. This hook serves as a way to make your introduction more engaging and compelling. For example, if you are writing a research paper on the impact of climate change on biodiversity, you could start your introduction with a statistic about the number of species that have gone extinct due to climate change. This will immediately grab the reader's attention and make them realize the urgency and importance of the topic.

Introducing Your Topic

Provide a brief overview, which should give the reader a general understanding of the subject matter and its significance. Explain the importance of the topic and its relevance to the field. This will help the reader understand why your research is significant and why they should continue reading. Continuing with the example of climate change and biodiversity, you could explain how climate change is one of the greatest threats to global biodiversity, how it affects ecosystems, and the potential consequences for both wildlife and human populations. By providing this context, you are setting the stage for the rest of your research paper and helping the reader understand the importance of your study.

Presenting Your Thesis Statement

The thesis statement should directly address your research question and provide a preview of the main arguments or findings discussed in your paper. Make sure your thesis statement is clear, concise, and well-supported by the evidence you will present in your research paper. By presenting a strong and focused thesis statement, you are providing the reader with the information they could anticipate in your research paper. This will help them understand the purpose and scope of your study and will make them more inclined to continue reading.

Writing Techniques for an Effective Introduction

When crafting an introduction, it is crucial to pay attention to the finer details that can elevate your writing to the next level. By utilizing specific writing techniques, you can captivate your readers and draw them into your research journey.

Using Clear and Concise Language

One of the most important writing techniques to employ in your introduction is the use of clear and concise language. By choosing your words carefully, you can effectively convey your ideas to the reader. It is essential to avoid using jargon or complex terminology that may confuse or alienate your audience. Instead, focus on communicating your research in a straightforward manner to ensure that your introduction is accessible to both experts in your field and those who may be new to the topic. This approach allows you to engage a broader audience and make your research more inclusive.

Establishing the Relevance of Your Research

One way to establish the relevance of your research is by highlighting how it fills a gap in the existing literature. Explain how your study addresses a significant research question that has not been adequately explored. By doing this, you demonstrate that your research is not only unique but also contributes to the broader knowledge in your field. Furthermore, it is important to emphasize the potential impact of your research. Whether it is advancing scientific understanding, informing policy decisions, or improving practical applications, make it clear to the reader how your study can make a difference.

By employing these two writing techniques in your introduction, you can effectively engage your readers. Take your time to craft an introduction that is both informative and captivating, leaving your readers eager to delve deeper into your research.

Revising and Polishing Your Introduction

Once you have written your introduction, it is crucial to revise and polish it to ensure that it effectively sets the stage for your research paper.

Self-Editing Techniques

Review your introduction for clarity, coherence, and logical flow. Ensure each paragraph introduces a new idea or argument with smooth transitions.

Check for grammatical errors, spelling mistakes, and awkward sentence structures.

Ensure that your introduction aligns with the overall tone and style of your research paper.

Seeking Feedback for Improvement

Consider seeking feedback from peers, colleagues, or your instructor. They can provide valuable insights and suggestions for improving your introduction. Be open to constructive criticism and use it to refine your introduction and make it more compelling for the reader.

Writing an introduction for a research paper requires careful thought and planning. By understanding the purpose of the introduction, preparing adequately, structuring effectively, and employing writing techniques, you can create an engaging and informative introduction for your research. Remember to revise and polish your introduction to ensure that it accurately represents the main ideas and arguments in your research paper. With a well-crafted introduction, you will capture the reader's attention and keep them inclined to your paper.

Suggested Reads

ResearchGPT: A Custom GPT for Researchers and Scientists Best Academic Search Engines [2023] How To Humanize AI Text In Scientific Articles Elevate Your Writing Game With AI Grammar Checker Tools

You might also like

AI for Meta Analysis — A Comprehensive Guide

How To Write An Argumentative Essay

Beyond Google Scholar: Why SciSpace is the best alternative

How to write an effective introduction for your research paper

Last updated

20 January 2024

Reviewed by

However, the introduction is a vital element of your research paper. It helps the reader decide whether your paper is worth their time. As such, it's worth taking your time to get it right.

In this article, we'll tell you everything you need to know about writing an effective introduction for your research paper.

- The importance of an introduction in research papers

The primary purpose of an introduction is to provide an overview of your paper. This lets readers gauge whether they want to continue reading or not. The introduction should provide a meaningful roadmap of your research to help them make this decision. It should let readers know whether the information they're interested in is likely to be found in the pages that follow.

Aside from providing readers with information about the content of your paper, the introduction also sets the tone. It shows readers the style of language they can expect, which can further help them to decide how far to read.

When you take into account both of these roles that an introduction plays, it becomes clear that crafting an engaging introduction is the best way to get your paper read more widely. First impressions count, and the introduction provides that impression to readers.

- The optimum length for a research paper introduction

While there's no magic formula to determine exactly how long a research paper introduction should be, there are a few guidelines. Some variables that impact the ideal introduction length include:

Field of study

Complexity of the topic

Specific requirements of the course or publication

A commonly recommended length of a research paper introduction is around 10% of the total paper’s length. So, a ten-page paper has a one-page introduction. If the topic is complex, it may require more background to craft a compelling intro. Humanities papers tend to have longer introductions than those of the hard sciences.

The best way to craft an introduction of the right length is to focus on clarity and conciseness. Tell the reader only what is necessary to set up your research. An introduction edited down with this goal in mind should end up at an acceptable length.

- Evaluating successful research paper introductions

A good way to gauge how to create a great introduction is by looking at examples from across your field. The most influential and well-regarded papers should provide some insights into what makes a good introduction.

Dissecting examples: what works and why

We can make some general assumptions by looking at common elements of a good introduction, regardless of the field of research.

A common structure is to start with a broad context, and then narrow that down to specific research questions or hypotheses. This creates a funnel that establishes the scope and relevance.

The most effective introductions are careful about the assumptions they make regarding reader knowledge. By clearly defining key terms and concepts instead of assuming the reader is familiar with them, these introductions set a more solid foundation for understanding.

To pull in the reader and make that all-important good first impression, excellent research paper introductions will often incorporate a compelling narrative or some striking fact that grabs the reader's attention.

Finally, good introductions provide clear citations from past research to back up the claims they're making. In the case of argumentative papers or essays (those that take a stance on a topic or issue), a strong thesis statement compels the reader to continue reading.

Common pitfalls to avoid in research paper introductions

You can also learn what not to do by looking at other research papers. Many authors have made mistakes you can learn from.

We've talked about the need to be clear and concise. Many introductions fail at this; they're verbose, vague, or otherwise fail to convey the research problem or hypothesis efficiently. This often comes in the form of an overemphasis on background information, which obscures the main research focus.

Ensure your introduction provides the proper emphasis and excitement around your research and its significance. Otherwise, fewer people will want to read more about it.

- Crafting a compelling introduction for a research paper

Let’s take a look at the steps required to craft an introduction that pulls readers in and compels them to learn more about your research.

Step 1: Capturing interest and setting the scene

To capture the reader's interest immediately, begin your introduction with a compelling question, a surprising fact, a provocative quote, or some other mechanism that will hook readers and pull them further into the paper.

As they continue reading, the introduction should contextualize your research within the current field, showing readers its relevance and importance. Clarify any essential terms that will help them better understand what you're saying. This keeps the fundamentals of your research accessible to all readers from all backgrounds.

Step 2: Building a solid foundation with background information

Including background information in your introduction serves two major purposes:

It helps to clarify the topic for the reader

It establishes the depth of your research

The approach you take when conveying this information depends on the type of paper.

For argumentative papers, you'll want to develop engaging background narratives. These should provide context for the argument you'll be presenting.

For empirical papers, highlighting past research is the key. Often, there will be some questions that weren't answered in those past papers. If your paper is focused on those areas, those papers make ideal candidates for you to discuss and critique in your introduction.

Step 3: Pinpointing the research challenge

To capture the attention of the reader, you need to explain what research challenges you'll be discussing.

For argumentative papers, this involves articulating why the argument you'll be making is important. What is its relevance to current discussions or problems? What is the potential impact of people accepting or rejecting your argument?

For empirical papers, explain how your research is addressing a gap in existing knowledge. What new insights or contributions will your research bring to your field?

Step 4: Clarifying your research aims and objectives

We mentioned earlier that the introduction to a research paper can serve as a roadmap for what's within. We've also frequently discussed the need for clarity. This step addresses both of these.

When writing an argumentative paper, craft a thesis statement with impact. Clearly articulate what your position is and the main points you intend to present. This will map out for the reader exactly what they'll get from reading the rest.

For empirical papers, focus on formulating precise research questions and hypotheses. Directly link them to the gaps or issues you've identified in existing research to show the reader the precise direction your research paper will take.

Step 5: Sketching the blueprint of your study

Continue building a roadmap for your readers by designing a structured outline for the paper. Guide the reader through your research journey, explaining what the different sections will contain and their relationship to one another.

This outline should flow seamlessly as you move from section to section. Creating this outline early can also help guide the creation of the paper itself, resulting in a final product that's better organized. In doing so, you'll craft a paper where each section flows intuitively from the next.

Step 6: Integrating your research question

To avoid letting your research question get lost in background information or clarifications, craft your introduction in such a way that the research question resonates throughout. The research question should clearly address a gap in existing knowledge or offer a new perspective on an existing problem.

Tell users your research question explicitly but also remember to frequently come back to it. When providing context or clarification, point out how it relates to the research question. This keeps your focus where it needs to be and prevents the topic of the paper from becoming under-emphasized.

Step 7: Establishing the scope and limitations

So far, we've talked mostly about what's in the paper and how to convey that information to readers. The opposite is also important. Information that's outside the scope of your paper should be made clear to the reader in the introduction so their expectations for what is to follow are set appropriately.

Similarly, be honest and upfront about the limitations of the study. Any constraints in methodology, data, or how far your findings can be generalized should be fully communicated in the introduction.

Step 8: Concluding the introduction with a promise

The final few lines of the introduction are your last chance to convince people to continue reading the rest of the paper. Here is where you should make it very clear what benefit they'll get from doing so. What topics will be covered? What questions will be answered? Make it clear what they will get for continuing.

By providing a quick recap of the key points contained in the introduction in its final lines and properly setting the stage for what follows in the rest of the paper, you refocus the reader's attention on the topic of your research and guide them to read more.

- Research paper introduction best practices

Following the steps above will give you a compelling introduction that hits on all the key points an introduction should have. Some more tips and tricks can make an introduction even more polished.

As you follow the steps above, keep the following tips in mind.

Set the right tone and style

Like every piece of writing, a research paper should be written for the audience. That is to say, it should match the tone and style that your academic discipline and target audience expect. This is typically a formal and academic tone, though the degree of formality varies by field.

Kno w the audience

The perfect introduction balances clarity with conciseness. The amount of clarification required for a given topic depends greatly on the target audience. Knowing who will be reading your paper will guide you in determining how much background information is required.

Adopt the CARS (create a research space) model

The CARS model is a helpful tool for structuring introductions. This structure has three parts. The beginning of the introduction establishes the general research area. Next, relevant literature is reviewed and critiqued. The final section outlines the purpose of your study as it relates to the previous parts.

Master the art of funneling

The CARS method is one example of a well-funneled introduction. These start broadly and then slowly narrow down to your specific research problem. It provides a nice narrative flow that provides the right information at the right time. If you stray from the CARS model, try to retain this same type of funneling.

Incorporate narrative element

People read research papers largely to be informed. But to inform the reader, you have to hold their attention. A narrative style, particularly in the introduction, is a great way to do that. This can be a compelling story, an intriguing question, or a description of a real-world problem.

Write the introduction last

By writing the introduction after the rest of the paper, you'll have a better idea of what your research entails and how the paper is structured. This prevents the common problem of writing something in the introduction and then forgetting to include it in the paper. It also means anything particularly exciting in the paper isn’t neglected in the intro.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- If you are writing in a new discipline, you should always make sure to ask about conventions and expectations for introductions, just as you would for any other aspect of the essay. For example, while it may be acceptable to write a two-paragraph (or longer) introduction for your papers in some courses, instructors in other disciplines, such as those in some Government courses, may expect a shorter introduction that includes a preview of the argument that will follow.

- In some disciplines (Government, Economics, and others), it’s common to offer an overview in the introduction of what points you will make in your essay. In other disciplines, you will not be expected to provide this overview in your introduction.

- Avoid writing a very general opening sentence. While it may be true that “Since the dawn of time, people have been telling love stories,” it won’t help you explain what’s interesting about your topic.

- Avoid writing a “funnel” introduction in which you begin with a very broad statement about a topic and move to a narrow statement about that topic. Broad generalizations about a topic will not add to your readers’ understanding of your specific essay topic.

- Avoid beginning with a dictionary definition of a term or concept you will be writing about. If the concept is complicated or unfamiliar to your readers, you will need to define it in detail later in your essay. If it’s not complicated, you can assume your readers already know the definition.

- Avoid offering too much detail in your introduction that a reader could better understand later in the paper.

- picture_as_pdf Introductions

How to Write a Research Paper Introduction

Learn how to write a research paper introduction with expert guidance.

Last updated on Mar 13th, 2024

When you click on affiliate links on QuillMuse.com and make a purchase, you won’t pay a penny more, but we’ll get a small commission—this helps us keep up with publishing valuable content on QuillMuse. Read More .

Table of Contents

We write different types of papers for academic and professional reasons. Research paper is one of the most important papers and it is different from other papers. There are different types of rules for writing a research paper , the first part is the introduction. Through this article, we will try to tell you how to write an introduction for a research paper beautifully.

Introduction

Before starting to write any papers, especially research papers one should know how to write a research paper introduction. The introduction is intended to guide the reader from a general subject to a specific area of study. It establishes the context of the research being conducted by summarizing current understanding and background information on the topic, stating the purpose of the work in the form of a thesis, question, or research problem, Briefly explaining your rationale, your methodological approach, highlight the potential findings your research may reveal, and describe the remaining structure of the paper.

A well-written introduction is imperative since, essentially, you never get a second chance to form a great first impression. The opening passage of your paper will give your audience their introductory impression, almost the rationale of your contention, your composing style, the general quality of your investigation, and, eventually, the legitimacy of your discoveries and conclusions. A vague, disorganized, or error-filled introduction will create a negative impression on the readers. While a brief, engaging, and well-written introduction will begin your readers off considering profoundly your expository abilities, your writing style, and your research approach.

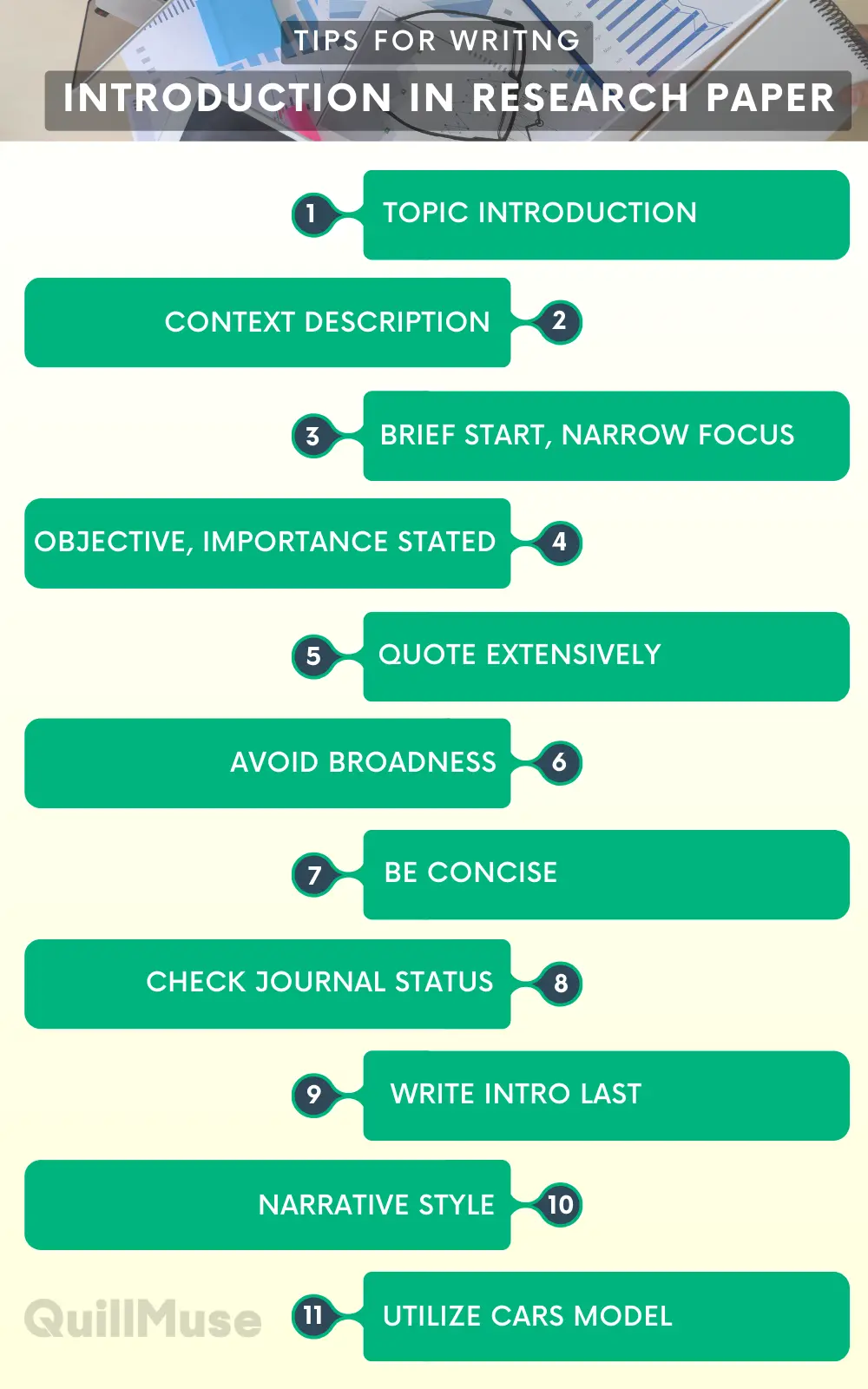

Tips for Writng an Introduction in Research Paper

Introduce your topic

This is a significant part of how to write an introduction for a research paper. The first task of the introduction is to tell the reader what your topic is and why it is interesting or important. This is usually done with a strong opening hook.

A hook is a strong opening sentence that conveys relevance to your topic. Think of an interesting fact or statistic, a powerful statement, a question, or a brief anecdote that will make readers wonder about your topic.

Describe the context

This introduction varies depending on your approach to your writing. In a more argumentative article, you will explore the general context here. In a more empirical paper, this is a great place to review previous research and determine how your research fits together.

Start briefly, and narrow down

The first thing of a research paper introduction is, to briefly describe your broad parts of research, then narrow in on your specific focus. This will help position your research topic within a broader field, making the work accessible to a wider audience than just experts in your field.

A common mistake when writing a research paper introduction is trying to fit everything in at once. Instead, pace yourself and present each piece of information in the most logical order the reader can understand. Typically, this means starting with the big picture and then gradually getting more specific with the details.

For your research paper introduction, you should first present an overview of the topic and then focus on your specific paper. This “funnel” structure naturally includes all the necessary parts of what should be included in a research paper introduction, from context to appropriate or research gaps and finally to relevance.

State Objective and Importance

Papers abandoned because they “do not demonstrate the importance of the topic” or “lack a clear motivation” often miss this point. Say what you want to achieve and why your readers should want to know whether you achieved it or not.

Quote generously

Once you have focused on the specific topic of your research, you should detail the latest and most relevant literature related to your research. Your literature review should be comprehensive but not too long. Remember, you are not writing a review. If you find your introduction is too long or has too many citations, a possible solution is to cite journal articles, rather than cite all of the individual articles that have been summarised in the journal.

Do not Keep it broad

Try to avoid lengthy introductions. A good target is between 500 and 1,000 words, although checking the magazine’s guidelines and back issues will provide the clearest guidance.

The introduction is not lengthy or detailed; rather, they are initiating actions. Introductions are best when they get to the point: save the details in the body of the document, where they belong.

The most important point of a research paper introduction is that they are clear and easy to understand. Writing at length can be distracting and even make your point harder to understand, so cut out unnecessary words and try to express things in simple terms that everyone understands. understandable.

Check journal condition

Many journals have specific assertions in their author instructions. For example, a maximum of one word may be stated, or instructions may require specific content, such as a supposition statement or a summary of your key findings.

Write the introduction to your research paper at the last moment

Your introduction may appear first in a research paper, but the general advice is to wait to write it until everything else has been written. This makes it easier for you to summarize your article because at this point you know everything you’re going to say. This also eliminates the urge to include everything in the introduction because you don’t want to forget anything.

Additionally, it is especially helpful to write an introduction after your research paper is finished. The introduction and conclusion of a research paper have similar topics and often reflect the structure of each topic. Writing the conclusion is also generally easier thanks to the pace created by writing the rest of the paper, and the conclusion can guide you in writing the introduction.

Make your introduction narrative style

Although not always appropriate for formal writing, using a narrative style in the introduction of your research paper can do a lot to engage readers and engage them emotionally. A 2016 study found that in some articles, using narrative strategies improved how often they were cited in other articles. Narrative style involves making the paper more personal to appeal to the reader’s emotions.

- Use first-person pronouns (I, we, my, our) to show that you are the narrator expressing emotions and feelings in the text setting up the scene.

- Describe the times and locations of important events to help readers visualize them.

- Appeal to the reader’s morality, sympathy, or urgency as a persuasive tactic. Again, this style will not be appropriate for all research paper introductions, especially those devoted to scientific research.

However, for more informal research papers and especially essays, this style can make your writing more interesting or at least interesting, perfect for making readers excited right from the beginning of the article.

Use the CARS model

British scientist John Swales developed a method called the CARS model to “generate a search space” in the introduction. Although intended for scientific papers, this simple three-step structure can be used to outline the introduction to any research paper.

Explain the background of your topic, including previous research. Explain that information is lacking in your topic area or that current research is incomplete.

Explain how your research “fills in” missing information about your topic.

the research findings and providing an overview of the structure of the rest of the paper, although this does not apply to all research papers, especially those Unofficial documents.

Six Essential Elements of How to Write a Research Paper Introduction

1. topic overview.

Start with a general overview of your topic. Refine your outline until you address the specific topic of your article. Next, mention any questions or concerns you have about the case. Note that you will address these in the article.

2. Previous research

Your introduction is the perfect place to review other findings about your topic. Includes both old and modern scholars. This general information shows that you are aware of previous research. It also presents previous findings to those who may not have that expertise.

3. A justification for your article

Explain why your topic needs to be discussed now. If possible, connect it to current issues. Additionally, you can point out problems with old theories or reveal gaps in current research. No matter how you do it, a good reason will keep readers interested and demonstrate why they should read the rest of your article.

4. Describe the method you used

Tell about your processes to make your writing more trustworthy. Identify your goals and the questions you will answer. Reveal how you conducted the research and describe how you measured the results. Also, explain why you made the important choices.

5. A thesis statement

Your main introduction should end with a thesis statement. This statement summarises the ideas that will run throughout your entire research paper. It must be simple and clear.

6. An outline

It is an adequate idea of how to write an introduction for a research paper.

The introduction usually ends with an overview. Your layout should quickly present what you plan to cover in the following sections. Think of it as a road map, guiding readers to the end of your article.

What is the purpose of the introduction in a research paper, and why is it considered crucial?

The purpose of the introduction in a research paper is to guide the reader from a general subject to a specific area of study. It establishes the context of the research by summarizing current understanding, stating the purpose of the work, explaining the rationale and methodological approach, highlighting potential findings, and describing the paper’s structure. It’s considered crucial because it forms the reader’s first impression and sets the tone for the rest of the paper.

How can I effectively use a hook to engage readers in my research paper introduction?

Using a hook, such as an interesting fact, a powerful statement, a question, or a brief anecdote, can effectively engage readers in your research paper introduction. A hook captures the reader’s attention and makes them curious about your topic, encouraging them to continue reading.

How long the introduction should be in a research paper?

While there’s no strict word count, a good target for a research paper introduction is between 500 and 1,000 words, although you should check the specific guidelines provided by the journal you’re submitting to. It’s recommended to write the introduction after the rest of the paper has been completed. This way, you have a comprehensive understanding of your research, making it easier to summarize and guide your readers effectively.

Conclusion

These are the important tips and tricks on how to write an introduction for a research paper properly. If you maintain these rules we believe that you will be able to write an excellent introduction in your research paper.

How we've reviewed this article

Our content is thoroughly researched and fact-checked using reputable sources. While we aim for precision, we encourage independent verification for complete confidence.

We keep our articles up-to-date regularly to ensure accuracy and relevance as new information becomes available.

- Current Version

- Mar 13th, 2024

- Oct 14th, 2023

Share this article

I found the step-by-step guide really helpful. Looking forward to implementing these tips in my next academic endeavor. Thanks for sharing!

Thank you for your positive feedback! We’re thrilled to hear that you found the guide helpful. If you have any more questions or need further assistance with your research paper, feel free to ask. Best of luck with your academic endeavors!

We write different types of papers for academic and professional reasons. Research paper is one of the most important papers and it is different from other papers. There are different types of rules for writing a research paper, the first part is the introduction. Through this article, we will try

MLA Format Research Paper: Examples & 9 Steps Guide

Writing a research paper in MLA format requires attention to detail and allegiance to particular rules set by the Modern Language Association. From formatting the title page to citing sources accurately, MLA format is fundamental for academic success. Let’s start by synthesizing the key components and steps included in making

How to Write a Research Paper Conclusion With Example

The conclusion is the last part of every research paper or document. Without a conclusion, your research paper will not be complete. A few days ago, I got some comments on our website about how to write a research paper conclusion. Some are interested in knowing about research paper conclusion

Report this article

Let us know if you notice any incorrect information about this article or if it was copied from others. We will take action against this article ASAP.

- Profile Page

- Edit Profile

- Add New Post

Read our Content Writing Guide .

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 4. The Introduction

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The introduction leads the reader from a general subject area to a particular topic of inquiry. It establishes the scope, context, and significance of the research being conducted by summarizing current understanding and background information about the topic, stating the purpose of the work in the form of the research problem supported by a hypothesis or a set of questions, explaining briefly the methodological approach used to examine the research problem, highlighting the potential outcomes your study can reveal, and outlining the remaining structure and organization of the paper.

Key Elements of the Research Proposal. Prepared under the direction of the Superintendent and by the 2010 Curriculum Design and Writing Team. Baltimore County Public Schools.

Importance of a Good Introduction

Think of the introduction as a mental road map that must answer for the reader these four questions:

- What was I studying?

- Why was this topic important to investigate?

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study?

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding?

According to Reyes, there are three overarching goals of a good introduction: 1) ensure that you summarize prior studies about the topic in a manner that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem; 2) explain how your study specifically addresses gaps in the literature, insufficient consideration of the topic, or other deficiency in the literature; and, 3) note the broader theoretical, empirical, and/or policy contributions and implications of your research.

A well-written introduction is important because, quite simply, you never get a second chance to make a good first impression. The opening paragraphs of your paper will provide your readers with their initial impressions about the logic of your argument, your writing style, the overall quality of your research, and, ultimately, the validity of your findings and conclusions. A vague, disorganized, or error-filled introduction will create a negative impression, whereas, a concise, engaging, and well-written introduction will lead your readers to think highly of your analytical skills, your writing style, and your research approach. All introductions should conclude with a brief paragraph that describes the organization of the rest of the paper.

Hirano, Eliana. “Research Article Introductions in English for Specific Purposes: A Comparison between Brazilian, Portuguese, and English.” English for Specific Purposes 28 (October 2009): 240-250; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide. Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Structure and Approach

The introduction is the broad beginning of the paper that answers three important questions for the reader:

- What is this?

- Why should I read it?

- What do you want me to think about / consider doing / react to?

Think of the structure of the introduction as an inverted triangle of information that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem. Organize the information so as to present the more general aspects of the topic early in the introduction, then narrow your analysis to more specific topical information that provides context, finally arriving at your research problem and the rationale for studying it [often written as a series of key questions to be addressed or framed as a hypothesis or set of assumptions to be tested] and, whenever possible, a description of the potential outcomes your study can reveal.

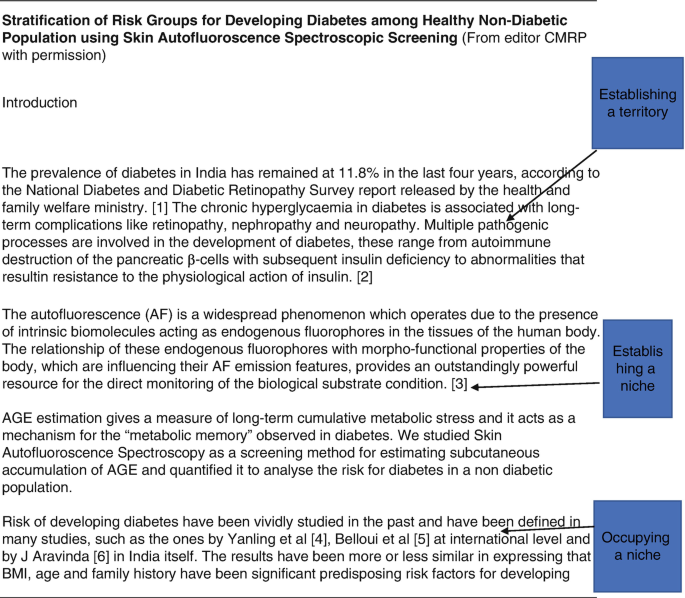

These are general phases associated with writing an introduction: 1. Establish an area to research by:

- Highlighting the importance of the topic, and/or

- Making general statements about the topic, and/or

- Presenting an overview on current research on the subject.

2. Identify a research niche by:

- Opposing an existing assumption, and/or

- Revealing a gap in existing research, and/or

- Formulating a research question or problem, and/or

- Continuing a disciplinary tradition.

3. Place your research within the research niche by:

- Stating the intent of your study,

- Outlining the key characteristics of your study,

- Describing important results, and

- Giving a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

NOTE: It is often useful to review the introduction late in the writing process. This is appropriate because outcomes are unknown until you've completed the study. After you complete writing the body of the paper, go back and review introductory descriptions of the structure of the paper, the method of data gathering, the reporting and analysis of results, and the conclusion. Reviewing and, if necessary, rewriting the introduction ensures that it correctly matches the overall structure of your final paper.

II. Delimitations of the Study

Delimitations refer to those characteristics that limit the scope and define the conceptual boundaries of your research . This is determined by the conscious exclusionary and inclusionary decisions you make about how to investigate the research problem. In other words, not only should you tell the reader what it is you are studying and why, but you must also acknowledge why you rejected alternative approaches that could have been used to examine the topic.

Obviously, the first limiting step was the choice of research problem itself. However, implicit are other, related problems that could have been chosen but were rejected. These should be noted in the conclusion of your introduction. For example, a delimitating statement could read, "Although many factors can be understood to impact the likelihood young people will vote, this study will focus on socioeconomic factors related to the need to work full-time while in school." The point is not to document every possible delimiting factor, but to highlight why previously researched issues related to the topic were not addressed.

Examples of delimitating choices would be:

- The key aims and objectives of your study,

- The research questions that you address,

- The variables of interest [i.e., the various factors and features of the phenomenon being studied],

- The method(s) of investigation,

- The time period your study covers, and

- Any relevant alternative theoretical frameworks that could have been adopted.

Review each of these decisions. Not only do you clearly establish what you intend to accomplish in your research, but you should also include a declaration of what the study does not intend to cover. In the latter case, your exclusionary decisions should be based upon criteria understood as, "not interesting"; "not directly relevant"; “too problematic because..."; "not feasible," and the like. Make this reasoning explicit!

NOTE: Delimitations refer to the initial choices made about the broader, overall design of your study and should not be confused with documenting the limitations of your study discovered after the research has been completed.

ANOTHER NOTE : Do not view delimitating statements as admitting to an inherent failing or shortcoming in your research. They are an accepted element of academic writing intended to keep the reader focused on the research problem by explicitly defining the conceptual boundaries and scope of your study. It addresses any critical questions in the reader's mind of, "Why the hell didn't the author examine this?"

III. The Narrative Flow

Issues to keep in mind that will help the narrative flow in your introduction :

- Your introduction should clearly identify the subject area of interest . A simple strategy to follow is to use key words from your title in the first few sentences of the introduction. This will help focus the introduction on the topic at the appropriate level and ensures that you get to the subject matter quickly without losing focus, or discussing information that is too general.

- Establish context by providing a brief and balanced review of the pertinent published literature that is available on the subject. The key is to summarize for the reader what is known about the specific research problem before you did your analysis. This part of your introduction should not represent a comprehensive literature review--that comes next. It consists of a general review of the important, foundational research literature [with citations] that establishes a foundation for understanding key elements of the research problem. See the drop-down menu under this tab for " Background Information " regarding types of contexts.

- Clearly state the hypothesis that you investigated . When you are first learning to write in this format it is okay, and actually preferable, to use a past statement like, "The purpose of this study was to...." or "We investigated three possible mechanisms to explain the...."

- Why did you choose this kind of research study or design? Provide a clear statement of the rationale for your approach to the problem studied. This will usually follow your statement of purpose in the last paragraph of the introduction.

IV. Engaging the Reader

A research problem in the social sciences can come across as dry and uninteresting to anyone unfamiliar with the topic . Therefore, one of the goals of your introduction is to make readers want to read your paper. Here are several strategies you can use to grab the reader's attention:

- Open with a compelling story . Almost all research problems in the social sciences, no matter how obscure or esoteric , are really about the lives of people. Telling a story that humanizes an issue can help illuminate the significance of the problem and help the reader empathize with those affected by the condition being studied.

- Include a strong quotation or a vivid, perhaps unexpected, anecdote . During your review of the literature, make note of any quotes or anecdotes that grab your attention because they can used in your introduction to highlight the research problem in a captivating way.

- Pose a provocative or thought-provoking question . Your research problem should be framed by a set of questions to be addressed or hypotheses to be tested. However, a provocative question can be presented in the beginning of your introduction that challenges an existing assumption or compels the reader to consider an alternative viewpoint that helps establish the significance of your study.

- Describe a puzzling scenario or incongruity . This involves highlighting an interesting quandary concerning the research problem or describing contradictory findings from prior studies about a topic. Posing what is essentially an unresolved intellectual riddle about the problem can engage the reader's interest in the study.

- Cite a stirring example or case study that illustrates why the research problem is important . Draw upon the findings of others to demonstrate the significance of the problem and to describe how your study builds upon or offers alternatives ways of investigating this prior research.

NOTE: It is important that you choose only one of the suggested strategies for engaging your readers. This avoids giving an impression that your paper is more flash than substance and does not distract from the substance of your study.

Freedman, Leora and Jerry Plotnick. Introductions and Conclusions. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Introduction. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Introductions. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Introductions, Body Paragraphs, and Conclusions for an Argument Paper. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Resources for Writers: Introduction Strategies. Program in Writing and Humanistic Studies. Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Sharpling, Gerald. Writing an Introduction. Centre for Applied Linguistics, University of Warwick; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Swales, John and Christine B. Feak. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Skills and Tasks . 2nd edition. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2004 ; Writing Your Introduction. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University.

Writing Tip

Avoid the "Dictionary" Introduction

Giving the dictionary definition of words related to the research problem may appear appropriate because it is important to define specific terminology that readers may be unfamiliar with. However, anyone can look a word up in the dictionary and a general dictionary is not a particularly authoritative source because it doesn't take into account the context of your topic and doesn't offer particularly detailed information. Also, placed in the context of a particular discipline, a term or concept may have a different meaning than what is found in a general dictionary. If you feel that you must seek out an authoritative definition, use a subject specific dictionary or encyclopedia [e.g., if you are a sociology student, search for dictionaries of sociology]. A good database for obtaining definitive definitions of concepts or terms is Credo Reference .

Saba, Robert. The College Research Paper. Florida International University; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

Another Writing Tip

When Do I Begin?

A common question asked at the start of any paper is, "Where should I begin?" An equally important question to ask yourself is, "When do I begin?" Research problems in the social sciences rarely rest in isolation from history. Therefore, it is important to lay a foundation for understanding the historical context underpinning the research problem. However, this information should be brief and succinct and begin at a point in time that illustrates the study's overall importance. For example, a study that investigates coffee cultivation and export in West Africa as a key stimulus for local economic growth needs to describe the beginning of exporting coffee in the region and establishing why economic growth is important. You do not need to give a long historical explanation about coffee exports in Africa. If a research problem requires a substantial exploration of the historical context, do this in the literature review section. In your introduction, make note of this as part of the "roadmap" [see below] that you use to describe the organization of your paper.

Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Always End with a Roadmap

The final paragraph or sentences of your introduction should forecast your main arguments and conclusions and provide a brief description of the rest of the paper [the "roadmap"] that let's the reader know where you are going and what to expect. A roadmap is important because it helps the reader place the research problem within the context of their own perspectives about the topic. In addition, concluding your introduction with an explicit roadmap tells the reader that you have a clear understanding of the structural purpose of your paper. In this way, the roadmap acts as a type of promise to yourself and to your readers that you will follow a consistent and coherent approach to addressing the topic of inquiry. Refer to it often to help keep your writing focused and organized.