- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

How to Do a Science Investigatory Project

Last Updated: February 2, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Bess Ruff, MA . Bess Ruff is a Geography PhD student at Florida State University. She received her MA in Environmental Science and Management from the University of California, Santa Barbara in 2016. She has conducted survey work for marine spatial planning projects in the Caribbean and provided research support as a graduate fellow for the Sustainable Fisheries Group. There are 7 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 301,764 times.

A Science Investigatory Project (SIP) uses the scientific method to study and test an idea about how something works. It involves researching a topic, formulating a working theory (or hypothesis) that can be tested, conducting the experiment, and recording and reporting the results. You will probably need to follow this procedure if you are planning to enter a project in a school science fair, for instance. However, knowing how to do an SIP is useful for anyone interested in the sciences as well as anyone who wants to improve their problem-solving skills.

Employing the Scientific Method

- Think about something that interests, surprises, or confuses you, and consider whether it is something you can reasonably investigate for a project. Formulate a single question that sums up you would like to examine. [1] X Research source

- For instance, say you've heard that you can make a simple solar oven out of a pizza box. [2] X Research source You may, however, be skeptical as to whether this can be done, or done consistently at least. Therefore, your question might be: "Can a simple solar oven be made that works consistently in various conditions?"

- Make sure the topic you select is manageable within your time frame, budget, and skill level, and that it doesn't break any rules for the assignment/fair/competition (for example, no animal testing). You can search for ideas online if you need help, but don't just copy a project you find there; this will also be against the rules and is unethical.

- However, you can modify an existing project to test a different hypothesis or look into a question that was not answered by previous experiments. This isn't an ethical breach, and can often make for interesting results and discussions.

- Be aware of the requirements for your project. Many science fairs require that you have at least three reputable academic sources such as peer-reviewed journal publications to use as references. [4] X Research source

- Your sources will need to be unbiased (not tied to a product for sale, for instance), timely (not an encyclopedia from 1965), and credible (not some anonymous comment on a blog post). Web sources that are supported by a scientific organization or journal are a good bet. Ask your teacher or project director for guidance if you need it.

- For instance, the search query "how to make a solar oven out of a pizza box" will produce a bounty of sources, some more scientifically-grounded (and thus reliable) than others. The hit on an on-topic article in a recognized, reputable periodical should be considered a valid source. [5] X Research source

- On the other hand, blog posts, anonymous articles, and crowd-sourced materials probably won't make the cut. As valuable a resource as wikiHow is, it may not be considered a valid source for your SIP. It can, however, be helpful in introducing you to your chosen experiment and pointing you toward more academic sources. Choosing well-developed articles with numerous footnotes (that link to solid sources themselves) will improve the odds of acceptance, but discuss the issue with your instructor, fair organizer, etc.

- It is often helpful to turn your question into a hypothesis by thinking in "if / then" terms. You may want to frame your hypothesis (at least initially) as "If [I do this], then [this will happen]."

- For our example, the hypothesis might be: "A solar oven made from a pizza box can consistently heat foods any time there is abundant sunshine."

- Consideration of variables is key in setting up your experiment. Scientific experiments have three types of variables: independent (those changed by you); dependent (those that change in response to the independent variable); and controlled (those that remain the same). [8] X Trustworthy Source Science Buddies Expert-sourced database of science projects, explanations, and educational material Go to source

- When planning your experiment, consider the materials that you will need. Make sure they are readily available and affordable, or even better, use materials that are already in your house.

- For our pizza box solar oven, the materials are easy to acquire and assemble. The oven, item cooked (s'mores, for instance), and full sunshine will be controlled variables. Other environmental conditions (time or day or time of year, for instance) could be the independent variable; and "done-ness" of the item the dependent variable.

- Closely follow the steps that you have planned to test your experiment. However, if your test can not be conducted as planned, reconfigure your steps or try different materials. (If you really want to win the science fair, this will be a big step for you!)

- It is common practice for science fairs that you will need to conduct your test at least three times to ensure a scientifically-valid result. [10] X Trustworthy Source Science Buddies Expert-sourced database of science projects, explanations, and educational material Go to source

- For our pizza box oven, then, let's say you decide to test your solar oven by placing it in direct sun on three similar, 90-degree Fahrenheit days in July, at three times each day (10 am, 2 pm, 6 pm).

- Sometimes your data may be best recorded as a graph, chart, or just a journal entry. However you record the data, make sure it is easy to review and analyze. Keep accurate records of all your results, even if they don't turn out the way you hoped or planned. This is also part of science! [11] X Research source

- As per the solar oven tests at 10 am, 2 pm, and 6 pm on three sunny days, you will need to utilize your results. By recording the done-ness of your s'mores (by how melted the chocolate and marshmallow is, for instance), you may find that only the 2 pm placement was consistently successful. [12] X Research source

- If you started out with a simple, clear, straightforward question, and a similar hypothesis, it should be easier to craft your conclusion.

- Remember, concluding that your hypothesis was completely wrong does not make your SIP a failure. If you make clear, scientifically-grounded findings, and present them well, it can and will be a success.

- In the pizza box solar oven example, our hypothesis was "A solar oven made from a pizza box can consistently heat foods any time there is abundant sunshine." Our conclusion, however, might be: "A solar oven made from a pizza box can only be consistently successful in heating foods in mid-day sun on a hot day."

Explaining and Presenting Your Project

- For a science fair, for example, the judging could be based on the following criteria (adding up to 100%): research paper (50%); oral presentation (30%); display poster (20%).

- SIP abstracts are often limited to one page in length, and perhaps 250 words. In this short space, focus on the purpose of your experiment, procedures, results, and any possible applications. [14] X Research source

- Use the guidelines provide by your teacher or the science fair director for information on how to construct your research paper.

- As one example, your paper may need to be broken down into categories such as: 1) Title Page; 2) Introduction (where you identify your topic and hypothesis); 3) Materials & Methods (where you describe your experiment); 4) Results & Discoveries (where you identify your findings); 5) Conclusion & Recommendations (where you "answer" your hypothesis); 6) References (where you list your sources).

- Write up your research paper first, and use it as your guide in constructing your oral presentation. Follow a similar framework in outlining your hypothesis, experiments, results, and conclusions.

- Focus on clarity and concision. Make sure everyone understands what you did, why you did it, and what you discovered in doing it.

- Science fairs commonly use a standard size, three panel display board, approximately 36 inches high by 48 inches wide.

- You should lay out your poster like the front page of a newspaper, with your title at the top, hypothesis and conclusion front and center, and supporting materials (methods, sources, etc.) clearly placed under headings on either side.

- Use images, diagrams, and the like to spruce up the visual appeal of your poster, but don't sacrifice content for visual pizzazz.

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.khanacademy.org/science/biology/intro-to-biology/science-of-biology/a/the-science-of-biology

- ↑ http://www.education.com/science-fair/article/design-solar-cooker/

- ↑ https://www.societyforscience.org/isef/international-rules/rules-for-all-projects/

- ↑ http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/sunny-science-build-a-pizza-box-solar-oven/

- ↑ http://www.sciencebuddies.org/science-fair-projects/project_guide_index.shtml

- ↑ http://spaceplace.nasa.gov/science-fair/en/

- ↑ https://ctsciencefair.org/student-guide/abstract

About This Article

To do a science investigatory project, start by thinking about a question you'd like to answer. For example, you may be wondering “Does the same kind of mold grow on different types of bread?” Then, once you have a question that's specific, form a hypothesis about what you think the answer will be. For this experiment, a good hypothesis might be “While all bread will produce the same kind of mold, the type of bread will impact how fast the mold grows.” With this hypothesis in mind, grab a few different kinds of of bread, set up your work station, and do your experiment at least 3 times to make sure the results are right. To learn how to record and analyze your results, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Did this article help you?

Rachelle Hart Matthews

Dec 3, 2016

DennisDayline Saga Nuñez

May 30, 2017

Lamberto Garcia

Nov 19, 2016

Roselyn Fadri

Dec 7, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Writing a Science Report

With science fair season coming up as well as many end of the year projects, students are often required to write a research paper or a report on their project. Use this guide to help you in the process from finding a topic to revising and editing your final paper.

Brainstorming Topics

Sometimes one of the largest barriers to writing a research paper is trying to figure out what to write about. Many times the topic is supplied by the teacher, or the curriculum tells what the student should research and write about. However, this is not always the case. Sometimes the student is given a very broad concept to write a research paper on, for example, water. Within the category of water, there are many topics and subtopics that would be appropriate. Topics about water can include anything from the three states of water, different water sources, minerals found in water, how water is used by living organisms, the water cycle, or how to find water in the desert. The point is that “water” is a very large topic and would be too broad to be adequately covered in a typical 3-5 page research paper.

When given a broad category to write about, it is important to narrow it down to a topic that is much more manageable. Sometimes research needs to be done in order to find the best topic to write about. (Look for searching tips in “Finding and Gathering Information.”) Listed below are some tips and guidelines for picking a suitable research topic:

- Pick a topic within the category that you find interesting. It makes it that much easier to research and write about a topic if it interests you.

- You may find while researching a topic that the details of the topic are very boring to you. If this is the case, and you have the option to do this, change your topic.

- Pick a topic that you are already familiar with and research further into that area to build on your current knowledge.

- When researching topics to do your paper on, look at how much information you are finding. If you are finding very little information on your topic or you are finding an overwhelming amount, you may need to rethink your topic.

- If permissible, always leave yourself open to changing your topic. While researching for topics, you may come across one that you find really interesting and can use just as well as the previous topics you were searching for.

- Most importantly, does your research topic fit the guidelines set forth by your teacher or curriculum?

Finding and Gathering Information

There are numerous resources out there to help you find information on the topic selected for your research paper. One of the first places to begin research is at your local library. Use the Dewey Decimal System or ask the librarian to help you find books related to your topic. There are also a variety of reference materials, such as encyclopedias, available at the library.

A relatively new reference resource has become available with the power of technology – the Internet. While the Internet allows the user to access a wealth of information that is often more up-to-date than printed materials such as books and encyclopedias, there are certainly drawbacks to using it. It can be hard to tell whether or not a site contains factual information or just someone’s opinion. A site can also be dangerous or inappropriate for students to use.

You may find that certain science concepts and science terminology are not easy to find in regular dictionaries and encyclopedias. A science dictionary or science encyclopedia can help you find more in-depth and relevant information for your science report. If your topic is very technical or specific, reference materials such as medical dictionaries and chemistry encyclopedias may also be good resources to use.

If you are writing a report for your science fair project, not only will you be finding information from published sources, you will also be generating your own data, results, and conclusions. Keep a journal that tracks and records your experiments and results. When writing your report, you can either write out your findings from your experiments or display them using graphs or charts .

*As you are gathering information, keep a working bibliography of where you found your sources. Look under “Citing Sources” for more information. This will save you a lot of time in the long run!

Organizing Information

Most people find it hard to just take all the information they have gathered from their research and write it out in paper form. It is hard to get a starting point and go from the beginning to the end. You probably have several ideas you know you want to put in your paper, but you may be having trouble deciding where these ideas should go. Organizing your information in a way where new thoughts can be added to a subtopic at any time is a great way to organize the information you have about your topic. Here are two of the more popular ways to organize information so it can be used in a research paper:

- Graphic organizers such as a web or mind map . Mind maps are basically stating the main topic of your paper, then branching off into as many subtopics as possible about the main topic. Enchanted Learning has a list of several different types of mind maps as well as information on how to use them and what topics fit best for each type of mind map and graphic organizer.

- Sub-Subtopic: Low temperatures and adequate amounts of snow are needed to form glaciers.

- Sub-Subtopic: Glaciers move large amounts of earth and debris.

- Sub-Subtopic: Two basic types of glaciers: valley and continental.

- Subtopic: Icebergs – large masses of ice floating on liquid water

Different Formats For Your Paper

Depending on your topic and your writing preference, the layout of your paper can greatly enhance how well the information on your topic is displayed.

1. Process . This method is used to explain how something is done or how it works by listing the steps of the process. For most science fair projects and science experiments, this is the best format. Reports for science fairs need the entire project written out from start to finish. Your report should include a title page, statement of purpose, hypothesis, materials and procedures, results and conclusions, discussion, and credits and bibliography. If applicable, graphs, tables, or charts should be included with the results portion of your report.

2. Cause and effect . This is another common science experiment research paper format. The basic premise is that because event X happened, event Y happened.

3. Specific to general . This method works best when trying to draw conclusions about how little topics and details are connected to support one main topic or idea.

4. Climatic order . Similar to the “specific to general” category, here details are listed in order from least important to most important.

5. General to specific . Works in a similar fashion as the method for organizing your information. The main topic or subtopic is stated first, followed by supporting details that give more information about the topic.

6. Compare and contrast . This method works best when you wish to show the similarities and/or differences between two or more topics. A block pattern is used when you first write about one topic and all its details and then write about the second topic and all its details. An alternating pattern can be used to describe a detail about the first topic and then compare that to the related detail of the second topic. The block pattern and alternating pattern can also be combined to make a format that better fits your research paper.

Citing Sources

When writing a research paper, you must cite your sources! Otherwise you are plagiarizing (claiming someone else’s ideas as your own) which can cause severe penalties from failing your research paper assignment in primary and secondary grades to failing the entire course (most colleges and universities have this policy). To help you avoid plagiarism, follow these simple steps:

- Find out what format for citing your paper your teacher or curriculum wishes you to use. One of the most widely used and widely accepted citation formats by scholars and schools is the Modern Language Association (MLA) format. We recommended that you do an Internet search for the most recent format of the citation style you will be using in your paper.

- Keep a working bibliography when researching your topic. Have a document in your computer files or a page in your notebook where you write down every source that you found and may use in your paper. (You probably will not use every resource you find, but it is much easier to delete unused sources later rather than try to find them four weeks down the road.) To make this process even easier, write the source down in the citation format that will be used in your paper. No matter what citation format you use, you should always write down title, author, publisher, published date, page numbers used, and if applicable, the volume and issue number.

- When collecting ideas and information from your sources, write the author’s last name at the end of the idea. When revising and formatting your paper, keep the author’s last name attached to the end of the idea, no matter where you move that idea. This way, you won’t have to go back and try to remember where the ideas in your paper came from.

- There are two ways to use the information in your paper: paraphrasing and quotes. The majority of your paper will be paraphrasing the information you found. Paraphrasing is basically restating the idea being used in your own words. As a general rule of thumb, no more than two of the original words should be used in sequence when paraphrasing information, and similes should be used for as many of the words as possible in the original passage without changing the meaning of the main point. Sometimes, you may find something stated so well by the original author that it would be best to use the author’s original words in your paper. When using the author’s original words, use quotation marks only around the words being directly quoted and work the quote into the body of your paper so that it makes sense grammatically. Search the Internet for more rules on paraphrasing and quoting information.

Revising and Editing Your Paper

Revising your paper basically means you are fixing grammatical errors or changing the meaning of what you wrote. After you have written the rough draft of your paper, read through it again to make sure the ideas in your paper flow and are cohesive. You may need to add in information, delete extra information, use a thesaurus to find a better word to better express a concept, reword a sentence, or just make sure your ideas are stated in a logical and progressive order.

After revising your paper, go back and edit it, correcting the capitalization, punctuation, and spelling errors – the mechanics of writing. If you are not 100% positive a word is spelled correctly, look it up in a dictionary. Ask a parent or teacher for help on the proper usage of commas, hyphens, capitalization, and numbers. You may also be able to find the answers to these questions by doing an Internet search on writing mechanics or by checking you local library for a book on writing mechanics.

It is also always a good idea to have someone else read your paper. Because this person did not write the paper and is not familiar with the topic, he or she is more likely to catch mistakes or ideas that do not quite make sense. This person can also give you insights or suggestions on how to reword or format your paper to make it flow better or convey your ideas better.

More Information:

- Quick Science Fair Guide

- Science Fair Project Ideas

Teaching Homeschool

Welcome! After you finish this article, we invite you to read other articles to assist you in teaching science at home on the Resource Center, which consists of hundreds of free science articles!

Shop for Science Supplies!

Home Science Tools offers a wide variety of science products and kits. Find affordable beakers, dissection supplies, chemicals, microscopes, and everything else you need to teach science for all ages!

Related Articles

Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS)

What are the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS)? These guidelines summarize what students “should” know and be able to do in different learning levels of science. The NGSS is based on research showing that students who are well-prepared for the future need...

The Beginners Guide to Choosing a Homeschool Science Curriculum

Homeschool science offers families incredible flexibility and personalization for their students’ education. There are many wonderful science curriculums available, and while plenty of options offer flexibility, figuring out which option is right for you can be a...

Synthetic Frog Dissection Guide Project

Frog dissections are a great way to learn about the human body, as frogs have many organs and tissues similar to those of humans. It is important to determine which type of dissection is best for your student or child. Some individuals do not enjoy performing...

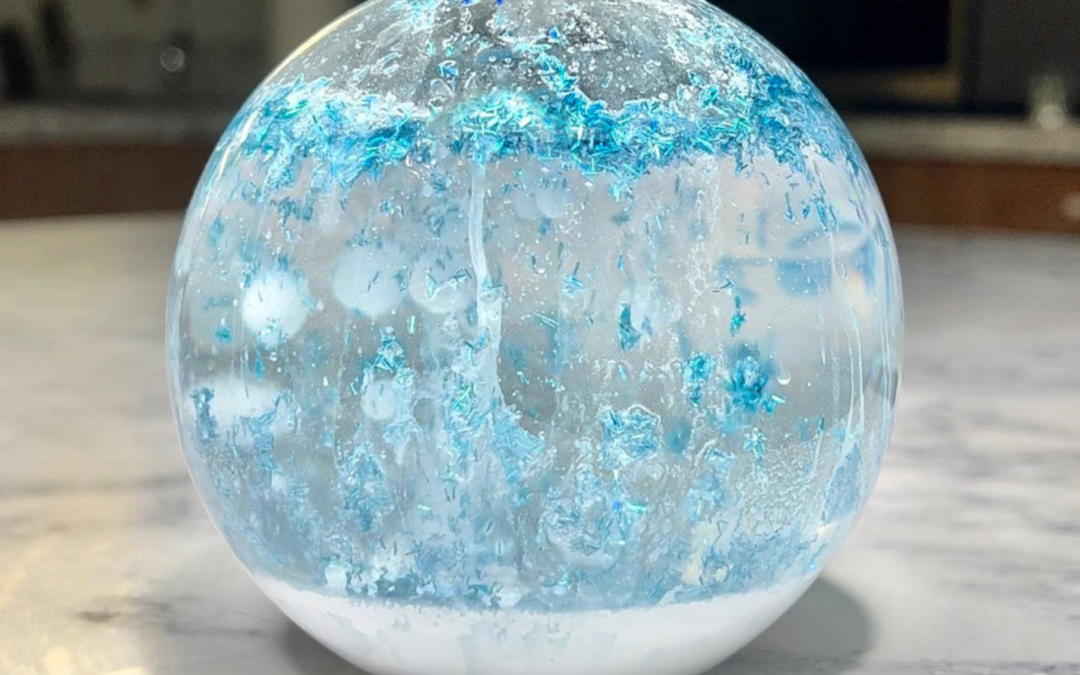

Snowstorm in a Boiling Flask Density Project

You know the mesmerizing feeling of watching the snow fall during a snowstorm? With this project, you can make your own snowstorm in a flask using an adaptation from the lava lamp science experiment! It’s a perfect project for any winter day.

Thanksgiving Family Genetics Activity

This Turkey Family Genetics activity is a fun way to teach your student about inheriting different traits and spark a lively conversation about why we look the way that we do.

JOIN OUR COMMUNITY

Get project ideas and special offers delivered to your inbox.

Advertisement

Investigative Research Projects for Students in Science: The State of the Field and a Research Agenda

- Open access

- Published: 16 March 2023

- Volume 23 , pages 80–95, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Michael J. Reiss ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1207-4229 1 ,

- Richard Sheldrake ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2909-6478 1 &

- Wilton Lodge ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9219-8880 1

3146 Accesses

2 Citations

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

One of the ways in which students can be taught science is by doing science, the intention being to help students understand the nature, processes, and methods of science. Investigative research projects may be used in an attempt to reflect some aspects of science more authentically than other teaching and learning approaches, such as confirmatory practical activities and teacher demonstrations. In this article, we are interested in the affordances of investigative research projects where students, either individually or collaboratively, undertake original research. We provide a critical rather than a systematic review of the field. We begin by examining the literature on the aims of science education, and how science is taught in schools, before specifically turning to investigative research projects. We examine how such projects are typically undertaken before reviewing their aims and, in more detail, the consequences for students of undertaking such projects. We conclude that we need social science research studies that make explicit the possible benefits of investigative research projects in science. Such studies should have adequate control groups that look at the long-term consequences of such projects not only by collecting delayed data from participants, but by following them longitudinally to see whether such projects make any difference to participants’ subsequent education and career destinations. We also conclude that there is too often a tendency for investigative research projects for students in science to ignore the reasons why scientists work in particular areas and to assume that once a written report of the research has been authored, the work is done. We therefore, while being positive about the potential for investigative research projects, make specific recommendations as to how greater authenticity might result from students undertaking such projects.

L’une des façons d’enseigner les sciences aux étudiants est de leur faire faire des activités scientifiques, l’objectif étant de les aider à comprendre la nature, les processus et les méthodes de la science. On peut avoir recours à des projets de recherche et d’enquête afin de refléter plus fidèlement certains éléments relevant de la science qu’en utilisant d’autres approches d’enseignement et d’apprentissage, telles que les activités pratiques de confirmation et les démonstrations faites par l’enseignant. Dans cet article, nous nous intéressons aux possibilités offertes par les projets de recherche dans lesquels les étudiants, individuellement ou en collaboration, entreprennent des recherches novatrices. Nous proposons un examen critique du domaine plutôt que d’y porter un regard systématique. Nous commençons par examiner la documentation portant sur les objectifs de l’enseignement des sciences et la manière dont les sciences sont enseignées dans les écoles, avant de nous intéresser plus particulièrement aux projets de recherche et d’enquête. Nous analysons la manière dont ces projets sont généralement menés avant d’examiner leurs buts et d’évaluer de façon plus approfondie quelles sont les conséquences pour les élèves de réaliser de tels projets. Nous constatons que nous avons besoin d’études de recherche en sciences sociales qui rendent explicites les avantages potentiels des projets de recherche et d’enquête scientifiques. Ces études devraient comporter des groupes de contrôle adéquats qui examinent les conséquences à long terme de ces projets, non seulement en recueillant des données différées auprès des participants, mais aussi en suivant ceux-ci de manière longitudinale de façon à voir si ces projets font une quelconque différence dans l’éducation subséquente et les destinations professionnelles ultérieures des participants. Nous concluons également que les projets de recherche et d’enquête des étudiants en sciences ont trop souvent tendance à ignorer les raisons pour lesquelles les scientifiques travaillent dans des domaines particuliers et à supposer qu’une fois que le rapport de recherche a été rédigé, le travail est terminé. Par conséquent, tout en demeurant optimistes quant au potentiel que représentent les projets de recherche et d’enquête, nous formulons des recommandations particulières en ce qui a trait à la manière dont une plus grande authenticité pourrait résulter de la réalisation de tels projets par les étudiants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Investigative School Research Projects in Biology: Effects on Students

Moving Research into the Classroom: Synergy in Collaboration

Reintroducing “the” Scientific Method to Introduce Scientific Inquiry in Schools?

Markus Emden

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Many young people are interested in science but do not necessarily see themselves as able to become scientists (Archer & DeWitt, 2017 ; Archer et al., 2015 ). Others may not want to become scientists even though they may see themselves as succeeding in science (Gokpinar & Reiss, 2016 ). At the same time, in many countries, governments and industry want more young people to continue with science, primarily in the hope that they will go into science or science-related careers (including engineering and technology), but also because of the benefits to society that are presumed to flow from having a scientifically literate population. Making science more inclusive and accessible to everyone may need endeavours and support from across education, employers, and society (Royal Society, 2014 ; Institute of Physics, 2020 ).

However, getting more people to continue with science, once it is no longer compulsory, is only one purpose of school science (Mansfield & Reiss, 2020 ). Much of school science is focused on getting students to understand core content of science—things like the particulate theory of matter, and the causes of disease in humans and other organisms. Another strand in school science is on getting students to understand something of the practices of science, particularly through undertaking practical work. A further, recently emerging, position is that science education should help students to use their knowledge and critical understanding of the content and practices of science to strive for social and environmental justice (Sjöström & Eilks, 2018 ).

In this article, we are interested in the affordances of investigative research projects—discussed in more detail below but essentially pieces of work undertaken by students either individually or collaboratively in which they undertake original research. We provide a critical rather than a systematic review of the field and suggest how future research might be undertaken to explore in more detail the possible contribution of such projects. We begin by examining the literature on the aims of science education, and how science is taught in schools, before specifically turning to investigative research projects. We examine how such projects are typically undertaken before reviewing their aims and, in more detail, the consequences for students of undertaking such projects. We make recommendations as to how investigative research projects might more fruitfully be undertaken and conclude by proposing a research agenda.

Aims of Science Education

School science education typically aims to prepare some students to become scientists, while concurrently educating all students in science and about science (Claussen & Osborne, 2013 ; Hofstein & Lunetta, 2004 ; Osborne & Dillon, 2008 ). For example, in England, especially for older students, the current science National Curriculum for 5–16-year-olds is framed as providing a platform for future studies and careers in science for some students, and providing knowledge and skills so that all students can understand and engage with the natural world within their everyday lives (Department for Education, 2014 ). Accordingly, science education within the National Curriculum in England broadly aims to develop students’ scientific knowledge and conceptual understanding; develop students’ understanding of the nature, processes, and methods of science (aspects of ‘working scientifically’, including experimental, analytical, and other related skills); and ensure that students understand the relevance, uses, and implications of science within everyday life (Department for Education, 2014 ). Comparable aims are typically found in other countries (Coll & Taylor, 2012 ; Hollins & Reiss, 2016 ).

Science education often involves practical work, which is generally intended to help students gain conceptual understanding, practical and wider skills, and understanding of how science and scientists work (Abrahams & Reiss, 2017 ; Cukurova et al., 2015 ; Hodson, 1993 ; Millar, 1998 ). Essentially, the thinking behind much practical work is that students would learn about science by doing science. Practical work has often been orientated towards confirming and illustrating scientific knowledge, although it is increasingly orientated around reflecting the processes of investigation and inquiry used within the field of science, and providing understanding of the nature of science (Abrahams & Reiss, 2017 ; Hofstein & Lunetta, 2004 ).

In many countries, especially those with the resources to have school laboratories, practical work in science is undertaken at secondary level relatively frequently, although this is less the case with older students (Hamlyn et al., 2020 , 2017 ). Practical work is more frequent in schools within more advantaged regions (Hamlyn et al., 2020 ) and many students report that they would have preferred to do more practical work (Cerini et al., 2003 ; Hamlyn et al., 2020 ).

The impact of practical work remains less clear (Cukurova et al., 2015 ; Gatsby Charitable Foundation, 2017 ). Society broadly expects that students in any one country will experience practical work to similar extents, so it is unfeasible, for more than a handful of lessons (e.g. Shana & Abulibdeh, 2020 ), to apply experimental designs where some students undertake practical work while others do not. One study, where students were assigned to one of four different groups, concluded that while conventional practical work led to more student learning than did either watching videos or reading textbooks, it was no more effective than when students watched a teacher demonstration (Moore et al., 2020 ).

The study by Moore et al. ( 2020 ) illustrates an important point, namely, that students can acquire conceptual knowledge and theoretical understanding by ways other than engagement in practical work. Indeed, there are some countries where less practical work is undertaken than in others, yet students score well, on average, on international measures of attainment. Some, but relatively few, studies have focused on whether the extent of practical work, and/or whether practical work undertaken in particular ways, associates with any educational or other outcomes. There are some indications that more frequent practical work associates with benefits (Cukurova et al., 2015 ). For example, students in higher-performing secondary schools have reported that they undertake more frequent practical work than pupils in lower-performing schools, although this does not reflect the impact of practical work alone (Hamlyn et al., 2017 ). In a more recent study, Oliver et al. ( 2021a , b ), in their analysis of the science scores in the six Anglophone countries (Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, the UK, and the USA) that participated in PISA (Program for International Student Assessment) 2015, found that “Of particular note is that the highest level of student achievement is associated with doing practical work in some lessons (rather than all or most) and this patterning is consistent across all six countries” (p. 35).

Students often appreciate and enjoy practical work in science (Hamlyn et al., 2020 ; National Foundation for Educational Research, 2011 ). Nevertheless, students do not necessarily understand the purposes of practical work, some feel that practical work may not necessarily be the best way to understand some aspects of science, and some highlight that practical work does not necessarily give them what they need for examinations (Abrahams & Reiss, 2012 ; Sharpe & Abrahams, 2020 ). Teachers have also spoken about the challenges of devising and delivering practical work, and often value practical work for being motivational for students rather than for helping them to understand science concepts (Gatsby Charitable Foundation, 2017 ; National Foundation for Educational Research, 2011 ).

Teaching Approaches

Educational research has examined how teaching and learning could best be undertaken. Many teaching and learning approaches have been found to associate with students’ learning outcomes, such as their achievement (Bennett et al., 2007 ; Furtak et al., 2012 ; Hattie et al., 2020 ; Savelsbergh et al., 2016 ; Schroeder et al., 2007 ) and interest (e.g. Chachashvili-Bolotin et al., 2016 ; Swarat et al., 2012 ), both in science and more generally. However, considering different teaching and learning approaches is complicated by terminology (where the definitions of terms can vary and/or terms can be applied in various ways) and wider aspects of generalisation (where it can be difficult to determine trends across studies undertaken in diverse ways across diverse contexts).

Inquiry-based approaches to teaching and learning generally involve students having more initiative to direct and undertake activities to develop their understanding (although not necessarily without guidance and support from teachers), such as working scientifically to devise and undertake investigations. However, it is important to emphasise that inquiry-based approaches do not necessitate practical work. Indeed, there are many subjects where no practical work takes place and yet students can undertake inquiries. In science, examples of non-practical-based inquiries that could fruitfully be undertaken collaboratively or individually and using the internet and/or libraries include the sort of research that students might undertake to investigate a socio-scientific issue. An example of such research includes what the effects of reintroducing an extinct or endangered species might be on an ecosystem, such as the reintroduction of the Eurasian beaver ( Castor fiber ) into the UK, or the barn owl ( Tyto alba ) into Canada. Inquiry-based learning in school science has often been found to associate with greater achievement (Furtak et al., 2012 ; Savelsbergh et al., 2016 ; Schroeder et al., 2007 ), though too much time spent on inquiry can result in reduced achievement (Oliver et al., 2021a ).

Allied to inquiry-based approaches is project-based learning. Here, students take initiative, manifest autonomy, and exercise responsibility for addressing an issue (often attempting to solve a problem) that usually results in an end product (such as a report or model), with teachers as facilitators and guides. The project occurs over a relatively long duration of time (Helle et al., 2006 ), to allow time for planning, revising, undertaking, and writing up the study. Project-based learning tends to associate positively with achievement (Chen & Yang, 2019 ).

Context-based approaches to teaching and learning use specific contexts and applications as starting points for the development of scientific ideas, rather than more traditional approaches that typically cover scientific ideas before moving on to consider their applications and contexts (Bennett et al., 2007 ). Context-based approaches have been found to be broadly equivalent to other teaching and learning approaches in developing students’ understanding, with some evidence for helping foster positive attitudes to science to a greater extent than traditional approaches (Bennett et al., 2007 ). Specifically relating learning to students’ experiences or context (referred to as ‘enhanced context strategies’) often associates positively with achievement (Schroeder et al., 2007 ). The literature on context-based approaches overlaps with that on the use of socio-scientific issues in science education, where students develop their scientific knowledge and understanding by considering complicated issues where science plays a role but on its own is not sufficient to produce solutions (e.g. Dawson, 2015 ; Zeidler & Sadler, 2008 ). To date, the literature on context-based approaches and/or socio-scientific issues has remained distinct from that on investigative research projects but, as we will argue below, there might be benefit in considering their intersection.

Various other teaching and learning approaches have been found to be beneficial in science, including collaborative work, computer-based work, and the provision of extra-curricular activities (Savelsbergh et al., 2016 ). Similarly, but specifically focusing on chemistry, various teaching and learning practices have been found to associate positively with academic outcomes, including (most strongly) collaborative learning and problem-based learning (Rahman & Lewis, 2019 ).

Most attention has focused on achievement-related outcomes. Nevertheless, inquiry-based learning, context-based learning, computer-based learning, collaborative learning, and extra-curricular activities have often also been found to associate positively with students’ interests and aspirations towards science (Savelsbergh et al., 2016 ). While many teaching and learning approaches associate with benefits, it remains difficult definitively to establish whether any particular approach is optimal and/or whether particular approaches are better than others. Teaching and learning time are limited, so applying a particular approach may mean not applying another approach.

Investigative Research Projects

Science education has often (implicitly or explicitly) been orientated around students learning science by doing science, intending to help students understand the nature, processes, and methods of science. An early critique of pedagogical approaches that saw students as scientists was provided by Driver ( 1983 ) who, while not dismissing the value of the approach, cautioned against over-enthusiastic adoption on the grounds that, unsurprisingly, school students, compared to actual scientists, manifest a range of misconceptions about how scientific research is undertaken. Contemporary recommendations for practical work include schools delivering frequent and varied practical activities (in at least half of all science lessons), and students also having the opportunity to undertake open-ended and extended investigative projects (Gatsby Charitable Foundation, 2017 ).

Investigative research projects may be intended to reflect some aspects of science more accurately or authentically than other teaching and learning approaches, such as confirmatory practical activities and teacher demonstrations. Nevertheless, authenticity in science and science education can be approached and/or defined in various ways (Braund & Reiss, 2006 ), and the issue raises wider questions such as whether only (adult) scientists can authentically experience science, and who determines what science is and what authentic experiences of science are (Kapon et al., 2018 ; Martin et al., 1990 ).

Although too tight a definition can be unhelpful, investigative research projects in science typically involve students determining a research question (where the outcome is unknown) and approaches to answer it, undertaking the investigation, analysing the data, and reporting the findings. The project may be undertaken alone or in groups, with support from teachers and/or others such as scientists and researchers (Bennett et al., 2018 ; Gatsby Charitable Foundation, 2017 ). Students may have varying degrees of autonomy—but then that is true of scientists too.

Independent research projects in science for students have often been framed around providing students with authentic experiences of scientific research and with the potential for wider benefits around scientific knowledge and skills, attitudes, and motivations around science, and ultimately helping science to become more inclusive and accessible to everyone (Bennett et al., 2018 ; Milner-Bolotin, 2012 ). Considered in review across numerous studies, independent research projects for secondary school students (aged 11–19) have often (but not necessarily always) resulted in benefits, including the following:

Acquisition of science-related knowledge (Burgin et al., 2012 ; Charney et al., 2007 ; Dijkstra & Goedhart, 2011 ; Houseal et al., 2014 ; Sousa-Silva et al., 2018 ; Ward et al., 2016 );

Enhancement of knowledge and/or skills around aspects of research and working scientifically (Bulte et al., 2006 ; Charney et al., 2007 ; Ebenezer et al., 2011 ; Etkina et al., 2003 ; Hsu & Espinoza, 2018 ; Ward et al., 2016 );

Greater confidence in undertaking various aspects of science, including applying knowledge and skills (Abraham, 2002 ; Carsten Conner et al., 2021 ; Hsu & Espinoza, 2018 ; Stake & Mares, 2001 , 2005 );

Aspirations towards science-related studies and/or careers (Abraham, 2002 ; Stake & Mares, 2001 ), although students in other studies have reported unchanged and already high aspirations towards science-related studies and/or careers (Burgin et al., 2015 , 2012 );

Subsequently entering science-related careers (Roberts & Wassersug, 2009 );

Development of science and/or research identities and/or identification as a scientist or researcher (Carsten Conner et al., 2021 ; Deemer et al., 2021 );

Feelings and experiences of real science and doing science (Barab & Hay, 2001 ; Burgin et al., 2015 ; Chapman & Feldman, 2017 );

Wider awareness and/or understanding of science, scientists, and/or positive attitudes towards science (Abraham, 2002 ; Houseal et al., 2014 ; Stake & Mares, 2005 );

Benefits akin to induction into scientific or research communities of practice (Carsten Conner et al., 2018 );

Development of wider personal, studying, and/or social skills, including working with others and independent work (Abraham, 2002 ; Moote, 2019 ; Moote et al., 2013 ; Sousa-Silva et al., 2018 ).

Positive experiences of projects and programmes are often conveyed by students (Dijkstra & Goedhart, 2011 ; Rushton et al., 2019 ; Williams et al., 2018 ). For example, students have reported appreciating the greater freedom and independence to discover things, and that they felt they were undertaking real experiments with a purpose, and a greater sense of meaning (Bulte et al., 2006 ).

Nevertheless, it remains difficult to determine the extent of generalisation from diverse research studies undertaken in various ways and across various contexts: benefits have been observed across studies involving different foci (determining what was measured and/or reported), projects for students, and contexts and countries. Essentially, each individual research study did not cover and/or evidence the whole range of benefits. Many benefits have been self-reported, and only some studies have considered changes over time (Moote, 2019 ; Moote et al., 2013 ).

Investigative science research projects for students are delivered in various ways. For example, some projects are undertaken through formal programmes that provide introductions and induction, learning modules, equipment, and the opportunity to present findings (Ward et al., 2016 ). Some programmes put a particular emphasis on the presentation and dissemination of findings (Bell et al., 2003 ; Ebenezer et al., 2011 ; Stake & Mares, 2005 ). Some projects are undertaken through schools (Ebenezer et al., 2011 ; Ward et al., 2016 ); others entail students working at universities, sometimes undertaking and/or assisting with existing projects (Bell et al., 2003 ; Burgin et al., 2015 , 2012 ; Charney et al., 2007 ; Stake & Mares, 2001 , 2005 ) or in competitions (e.g. Liao et al., 2017 ). While many projects are undertaken in laboratory settings, some are undertaken outdoors, in the field (Carsten Conner et al., 2018 ; Houseal et al., 2014 ; Young et al., 2020 ).

Primary School

While much of the school literature on investigative research projects in science concentrates on secondary or university students, some such projects are undertaken with students in primary school. These projects are often perceived as enjoyable and considered to benefit scientific skills and knowledge and/or confidence in doing science (Forbes & Skamp, 2019 ; Liljeström et al., 2013 ; Maiorca et al., 2021 ; Tyler-Wood et al., 2012 ). Such projects often help students feel that they are scientists and doing science (Forbes & Skamp, 2019 ; Reveles et al., 2004 ).

For example, one programme for primary school students in Australia intended students to develop and apply skills in thinking and working scientifically with support by scientist mentors over 10 weeks. It involved the students identifying areas of interest and testable questions within a wider scientific theme, collaboratively investigating their area of interest through collecting and analysing data, and then presenting their findings. Data on the programme’s outcomes were obtained through interviews with students and by studying the reports that they wrote (Forbes & Skamp, 2016 , 2019 ). Participating students said that they appreciated the autonomy and practical aspects, and enjoyed the experiences. The students showed developments in thinking scientifically and around the nature of science, where science often became seen as something that could be interesting, enjoyable, student-led, collaborative, creative, challenging, and a way to understand how things work within the world (Forbes & Skamp, 2019 ). The experiences of thinking and working scientifically, and aspects such as collaborative working and learning from each other, were broadly considered to help develop students’ scientific identities and include them within a scientific community of practice. Some students felt that they were doing authentic (‘real’) science, in contrast to some of their earlier or other experiences of science at school, which had not involved an emphasis on working scientifically and/or specific activities within working scientifically, such as collecting and analysing data (Forbes & Skamp, 2019 ).

CREST Awards

CREST Awards are intended to give young people (aged 5–19) in the UK the opportunity to explore real STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) projects, providing the experience of ‘being a scientist’ (British Science Association, 2018 ). The scheme has been running since the 1980s and some 30,000 Awards are given each year. They exist at three levels (Bronze, Silver, and Gold), reflecting the necessary time commitment and level of independence and originality expected. The Awards are presented as offering the potential for participants to experience the process of engaging in a project, and developing investigation, problem-solving, and communication skills. They are also presented as something that can contribute to further awards (such as Duke of Edinburgh Awards) and/or competition entries (such as The Big Bang Competition). CREST Gold Awards can be used to enhance applications to university and employment. At Gold level, arranging for a STEM professional in a field related to the student’s work to act as a mentor is recommended, though not formally required. CREST Awards are assessed by teachers and/or assessors from industry or academia, depending on the Award level.

Classes of secondary school students in Scotland undertaking CREST Awards projects appeared to show some benefits around motivational and studying strategies, but less clearly than would be ideal (Moote, 2019 ; Moote et al, 2013 ). Students undertaking CREST Silver Awards between 2010 and 2013 gained better qualifications at age 16 and were more likely to study science subjects for 16–19-year-olds than other comparable students (matched on prior attainment and certain personal characteristics), although the students may have differed on unmeasured aspects, such as attitudes and motivations towards science and studying (Stock Jones et al., 2016 ). A subsequent randomised controlled trial found that year 9 students (aged 13–14) undertaking CREST Silver Awards and other comparable students ultimately showed similar science test scores, attitudes towards school work, confidence in undertaking various aspects of life (not covering school work), attitudes towards science careers (inaccurately referred to as self-efficacy), and aspirations towards science careers (Husain et al., 2019 ). Nevertheless, teachers and students perceived benefits, including students acquiring transferable skills such as time management, problem-solving, and team working, and that science topics were made more interesting and relevant for students (Husain et al., 2019 ). Overall, it remains difficult to form any definitive conclusions about impacts, given the diverse scope of CREST Awards but limited research. For example, whether and/or how CREST Awards projects are independent of or integrated with curricula areas may determine the extent of (curricula-based) knowledge gains.

Nuffield Research Placements

Nuffield Research Placements involve students in the UK undertaking STEM research placements during the summer between years 12 and 13, and presenting their findings at a celebration event (Nuffield Foundation, 2020 ). The scheme has been running since 1996 and a little over 1000 students participate each year. The programme is variously framed as an opportunity for students to undertake real research and develop scientific and other skills, and an initiative to enhance access/inclusion and assist the progression of students into STEM studies at university (Cilauro & Paull, 2019 ; Nuffield Foundation, 2020 ).

The application process is competitive, and requires a personal statement where students explain their interest in completing the placement. Students need to be studying at least one STEM subject in year 12, be in full-time education at a state school (i.e. not a private school that requires fees), and have reached a certain academic level at year 11. The scheme historically aimed to support and prioritise students from disadvantaged backgrounds, and is now only available for students from disadvantaged backgrounds based on family income, living or having lived in care, and/or being the first person in their immediate family who will study in higher education (Nuffield Foundation, 2020 ).

There have been indications that students who undertake Nuffield Research Placements are, on average, more likely to enrol on STEM subjects at top (Russell Group) UK universities and complete a higher number of STEM qualifications for 16–19-year-olds than other students (Cilauro & Paull, 2019 ). Nevertheless, it remains difficult to isolate independent impacts of the placements, given that (for example) students commence their 16–19 education prior to the placements.

Following their Nuffield Research Placements, students have reported increased understanding of what STEM researchers do in their daily work and unchanging (already high) enjoyment of STEM and interest in STEM job opportunities (Bowes et al., 2017 ; Cilauro & Paull, 2019 ). Wider benefits have been attributed to the placement, including skills in writing reports, working independently, confidence in their own abilities in general, and team working (Bowes et al., 2017 ). Students also often report that they feel they have contributed to an authentic research study in an area of STEM in which they are interested (Bowes et al., 2021 ).

Institute for Research in Schools Projects

The Institute for Research in Schools (IRIS) started in 2016 and has about 1000 or more participating students in the UK annually. It facilitates students to undertake a range of investigative research projects from a varied portfolio of options. For example, these projects have included CERN@School (Whyntie, 2016 ; Whyntie et al., 2015 , 2016 ), where students have been found to have positive experiences, developing research and data analysis skills, and developing wider skills such as collaboration and communication (Hatfield et al., 2019 ; Parker et al., 2019 ). Teachers who have facilitated projects for their students (Rushton & Reiss, 2019 ) report that the experiences produced personal and wider benefits around:

Appreciating the freedom to teach and engage in the research projects;

Connecting or reconnecting with science and research, including interest and enthusiasm (in science as well as teaching it) and with a role as a scientist, including being able to share past experiences or work as a scientist with students;

Collaborating with students and scientists, researchers, and others in different and/or new ways via doing research (including facilitating students and providing support);

Professional and skills development (refreshing/revitalising teaching and interest), including recognition by colleagues/others (strengthening recognition as a teacher/scientist, as having skills, as someone who provides opportunities/support for students).

The teachers felt that their students developed a range of specific and transferable benefits, including around research, communication, teamwork, planning, leadership, interest and enthusiasm, confidence, and awareness of the realities of science and science careers. Some benefits could follow and/or be enhanced by the topics that the students were studying, such as interest and enthusiasm linking with personal and wider/real-life relevance, for example, for topics like biodiversity (Rushton & Reiss, 2019 ).

Students in England who completed IRIS projects and presented their findings at conferences reported that the experiences were beneficial through developing skills (including communication, confidence, and managing anxiety); gaining awareness, knowledge, and understanding of the processes of research and careers in research; collaboration and sharing with students and teachers; developing networks and contacts; and doing something that may benefit their university applications (Rushton et al., 2019 ). Presenting and disseminating findings at conferences were considered to be inspirational and validating (including experiencing the impressive scientific and historical context of the conference venue), although also challenging, given limited time, competing demands, anxiety and nervousness, and uncertainty about how to engage with others and undertake networking (Rushton et al., 2019 ).

Although our principal interest is in investigative research projects in science at school, it is worth briefly surveying the literature on such projects at university level. This is because while such projects are rare at school level, normally resulting from special initiatives, there is a long tradition in a number of countries of investigative research projects in science being undertaken at university level, alongside other types of practical work.

Unsurprisingly, university science students typically report having little to no prior experience with authentic research, although they may have had laboratory or fieldwork experience on their pre-university courses (Cartrette & Melroe-Lehrman, 2012 ; John & Creighton, 2011 ). University students still perceive non-investigative-based laboratory work as meaningful experiences of scientific laboratory work, even if these might be less authentic experiences of (some aspects of) scientific research (Goodwin et al., 2021 ; Rowland et al., 2016 ).

Research experiences for university science students are often framed around providing students with authentic experiences of scientific research, with more explicit foci towards developing research skills and practices, developing conceptual understanding, conveying the nature of science, and fostering science identities (Linn et al., 2015 ). Considered in review across numerous studies, research experiences for university science students have often (but not necessarily always) resulted in benefits, including to research skills and practices and confidence in applying them, enhanced understanding of the reality of scientific research and careers, and higher likelihood of persisting or progressing within science education and/or careers (Linn et al., 2015 ).

For example, in one study, university students of science in England reported having no experience of ‘real’ research before undertaking a summer research placement programme (John & Creighton, 2011 ). After the programme, the majority of students agreed that they had discovered that they liked research and that they had gained an understanding of the everyday realities of research. Most of the students reported that their placement confirmed or increased their intentions towards postgraduate study and research careers (John & Creighton, 2011 ).

Implications and Future Directions

Investigative research projects in science have the potential for various benefits, given the findings from wider research into inquiry-based learning (Furtak et al., 2012 ; Savelsbergh et al., 2016 ; Schroeder et al., 2007 ), context-based learning (Bennett et al., 2007 ; Schroeder et al., 2007 ), and project-based learning (Chen & Yang, 2019 ). However, the potential for benefits involves broad generalisations, where inquiry-based learning (for example) covers a diverse range of approaches that may or may not be similar to those encountered within investigative research projects. Furthermore, we do not see investigative research projects as a universal panacea. It is, for example, unrealistic to expect that students can simultaneously learn scientific knowledge, learn about scientific practice, and engage skillfully and appropriately in aspects of scientific practice. Indeed, careful scaffolding from teachers is likely to be required for any, let alone all, of these benefits to result.

We are conscious that enabling students to undertake investigative research projects in science places particular burdens on teachers. Anecdotal evidence suggests that if teachers themselves have had a university education in which they undertook one or more such projects themselves (e.g. because they undertook a research masters or doctorate in science), they are more likely both to be enthused about the benefits of this way of working and to be able to help their students undertake research. It would be good to have this hypothesis investigated rigorously and, more importantly, to have data on effective professional development for teachers to help their students undertake investigative research projects in science. It is known that school teachers of science can benefit from undertaking small-scale research projects as professional development (e.g. Bevins et al., 2011 ; Koomen et al., 2014 ), but such studies do not seem rigorously to have followed individual teachers through into their subsequent day-to-day work with their students to determine the long-term consequences for the students.

Benefits accruing from investigative research projects are likely to be enhanced if there is an alignment between the form of the assessment and the intended outcomes of the investigative research project (cf. Molefe, 2011 ). The first author recalls how advanced level biology projects (for 16–18-year-olds) were assessed in England by one of the Examination Boards back in the 1980s. At the end of the course, each student who had submitted such a project had a 15-min viva with an external examiner. The mark scheme rewarded not only the sorts of things that any advanced level biology mark scheme would credit (use of literature, appropriate research design, care in data collection, thorough analysis, etc.) but originality too. There was therefore an emphasis on novel research. Indeed, occasionally students published sole- or co-authored accounts of their work in biology or biology education journals.

We mentioned above Driver’s ( 1983 ) caution about the extent to which it is realistic to envisage high school students undertaking investigative research projects that have more than superficial resemblance to those undertaken by actual scientists. Nevertheless, as the above review indicates, there is a strong strand within school science education of advocating the benefits of students designing and undertaking open-ended research projects (cf. Albone et al., 1995 ). Roth ( 1995 ) argued that for school science to be authentic, students need to:

(1) learn in contexts constituted in part by ill-defined problems; (2) experience uncertainties and ambiguities and the social nature of scientific work and knowledge; (3) learning is predicated on, and driven by, their current knowledge state; (4) experience themselves as parts of communities of inquiry in which knowledge, practices, resources and discourse are shared; (5) in these communities, members can draw on the expertise of more knowledgeable others whether they are peers, advisors or teachers. (p. 1)

Investigative research projects in science allow learners to learn about science by doing science, and therefore might help foster science identities. Science identities can involve someone recognising themselves and also being recognised by others as being a science person, and also with having various experiences, knowledge, and skills that are valued and recognised within the wider fields of science.

However, the evidence base, as indicated above and in the systematic review of practical independent research projects in high school science undertaken by Bennett et al. ( 2018 ), is still not robust. We need research studies that make explicit the putative benefits of investigative research projects in science, that have adequate control groups, and that look at the long-term consequences of such projects not only by collecting delayed data from participants (whether by surveys or interviews) but by following them longitudinally to see whether such projects make any difference to their subsequent education and career destinations. We also know very little about the significance of students’ home circumstances for their enthusiasm and capacity to undertake investigative research projects in science, though it seems likely that students with high science capital (DeWitt et al., 2016 ) are more likely to receive familial support in undertaking such projects (cf. Lissitsa & Chachashvili‐Bolotin, 2019 ).

We also need studies that consider more carefully what it is to engage in scientific practices. It is notable that the existing literature on investigative research projects for students in science makes no use of the literature on ethnographic studies of scientists at work—neither the foundational texts (e.g. Latour & Woolgar, 1979 ; Knorr-Cetina, 1983 ) nor more recent studies (e.g. Silvast et al., 2020 ). Too often there is a tendency for investigative research projects for students in science to ignore the reasons why scientists work in particular areas and to assume that once a written report of the research has been authored, the work is done. There can also be a somewhat simplistic belief that the sine qua non of an investigative research project is experimental science. Keen as we are on experimental science, there is more to being a scientist than undertaking experiments. For example, computer simulations (Winsberg, 2019 ) and other approaches that take advantage of advances in digital technologies are of increasing importance to the work of many scientists. It would be good to see such approaches reflected in more school student investigative projects (cf. Staacks et al., 2018 ).

More generally, greater authenticity would be likely to result if the following three issues were explicitly considered with students:

How should the particular focus of the research be identified? Students should be helped to realise that virtually all scientific research requires substantial funding. It may not be enough, therefore, for students to identify the focus for their work on the grounds of personal interest alone if they wish to understand how science is undertaken in reality. Here, such activities as participating in well-designed citizen science projects that still enable student autonomy (e.g. Curtis, 2018 ) can help.

Students should be encouraged, once their written report has been completed, to present it at a conference (as happens, for instance, with many IRIS projects) and to write it up for publication. Writing for publication is more feasible now that publication can be via blogs or on the internet, compared to the days when the only possible outlets were hard-copy journals or monographs.

What change in the world does the research wish to effect? Much student research in science seems implicitly to presume that science is neutral. The reality—back to funding again—is that most scientific research is undertaken with specific ends in mind (for instance, the development of medical treatments, the location of valuable mineral ores, the manufacture of new products for which desire can also be manufactured). It is not, of course, that we are calling for students unquestioningly to adopt the same values as those of professional scientists. Rather, we would encourage students to be enabled to reflect on such ends and values.

Abraham, L. (2002). What do high school science students gain from field-based research apprenticeship programs? The Clearing House, 75 (5), 229–232.

Article Google Scholar

Abrahams, I., & Reiss, M. (2012). Practical work: its effectiveness in primary and secondary schools in England. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 49 (8), 1035–1055.

Abrahams, I., & Reiss, M. J. (Eds) (2017). Enhancing learning with effective practical science 11-16 . London: Bloomsbury.

Google Scholar

Albone, E., Collins, N., & Hill, T. (Eds) (1995). Scientific research in schools: a compendium of practical experience. Bristol: Clifton Scientific Trust.

Archer, L., Dawson, E., DeWitt, J., Seakins, A., & Wong, B. (2015). “Science capital”: a conceptual, methodological, and empirical argument for extending Bourdieusian notions of capital beyond the arts. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 52 (7), 922–948.

Archer, L., & DeWitt, J. (2017). Understanding young people’s science aspirations: How students form ideas about ‘becoming a scientist’. Abingdon: Routledge.

Barab, S., & Hay, K. (2001). Doing science at the elbows of experts: issues related to the science apprenticeship camp. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38 (1), 70–102.

Bell, R., Blair, L., Crawford, B., & Lederman, N. (2003). Just do it? Impact of a science apprenticeship program on high school students’ understandings of the nature of science and scientific inquiry. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 40 (5), 487–509.

Bennett, J., Dunlop, L., Knox, K., Reiss, M. J., & Torrance Jenkins, R. (2018). Practical independent research projects in science: a synthesis and evaluation of the evidence of impact on high school students. International Journal of Science Education, 40 (14), 1755–1773.

Bennett, J., Lubben, F., & Hogarth, S. (2007). Bringing science to life: a synthesis of the research evidence on the effects of context-based and STS approaches to science teaching. Science Education, 91 (3), 347–370.

Bevins, S., Jordan, J., & Perry, E. (2011). Reflecting on professional development. Educational Action Research, 19 (3), 399–411.

Bowes, L., Birkin, G., & Tazzyman, S. (2017). Nuffield research placements evaluation: final report on waves 1 to 3 of the longitudinal survey of 2016 applicants. Leicester: CFE Research.

Bowes, L., Tazzyman, S., Stutz, A., & Birkin, G. (2021). Evaluation of Nuffield future researchers. London: Nuffield Foundation.

Braund, M., & Reiss, M. (2006). Towards a more authentic science curriculum: the contribution of out-of-school learning. International Journal of Science Education , 28 , 1373–1388.

British Science Association. (2018). CREST Awards: getting started guide, primary. London: British Science Association.

Bulte, A., Westbroek, H., de Jong, O., & Pilot, A. (2006). A research approach to designing chemistry education using authentic practices as contexts. International Journal of Science Education, 28 (9), 1063–1086.

Burgin, S., McConnell, W., & Flowers, A. (2015). ‘I actually contributed to their research’: the influence of an abbreviated summer apprenticeship program in science and engineering for diverse high-school learners. International Journal of Science Education, 37 (3), 411–445.

Burgin, S., Sadler, T., & Koroly, M. J. (2012). High school student participation in scientific research apprenticeships: variation in and relationships among student experiences and outcomes. Research in Science Education, 42 , 439–467.

Carsten Conner, L., Oxtoby, L., & Perin, S. (2021). Power and positionality shape identity work during a science research apprenticeship for girls. International Journal of Science Education , 1–14.

Carsten Conner, L., Perin, S., & Pettit, E. (2018). Tacit knowledge and girls’ notions about a field science community of practice. International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 8 (2), 164–177.

Cartrette, D., & Melroe-Lehrman, B. (2012). Describing changes in undergraduate students’ preconceptions of research activities. Research in Science Education, 42 , 1073–1100.

Cerini, B., Murray, I., & Reiss, M. (2003). Student review of the science curriculum: major findings . London: Planet Science.

Chachashvili-Bolotin, S., Milner-Bolotin, M., & Lissitsa, S. (2016). Examination of factors predicting secondary students’ interest in tertiary STEM education. International Journal of Science Education , 38 (3), 366–390.

Chapman, A., & Feldman, A. (2017). Cultivation of science identity through authentic science in an urban high school classroom. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 12 , 469–491.

Charney, J., Hmelo-Silver, C., Sofer, W., Neigeborn, L., Coletta, S., & Nemeroff, M. (2007). Cognitive apprenticeship in science through immersion in laboratory practices. International Journal of Science Education, 29 (2), 195–213.

Chen, C.-H., & Yang, Y.-C. (2019). Revisiting the effects of project-based learning on students’ academic achievement: a meta-analysis investigating moderators. Educational Research Review, 26 , 71–81.

Cilauro, F., & Paull, G. (2019). Evaluation of Nuffield research placements: interim report. London: Nuffield Foundation.

Claussen, S., & Osborne, J. (2013). Bourdieu’s notion of cultural capital and its implications for the science curriculum. Science Education, 97 (1), 58–79.

Coll, R. K., & Taylor, N. (2012). An international perspective on science curriculum development and implementation. In B. J. Fraser, K. Tobin, & C. J. McRobbie (Eds), Second international handbook of science education (pp. 771–782). Springer, Dordrecht.

Chapter Google Scholar

Cukurova, M., Hanley, P., & Lewis, A. (2015). Rapid evidence review of good practical science. London: Gatsby Charitable Foundation.

Curtis, V. (2018). Online citizen science and the widening of academia: distributed engagement with research and knowledge production . Cham: Palgrave.

Dawson, V. (2015). Western Australian high school students’ understandings about the socioscientific issue of climate change. International Journal of Science Education , 37 (7), 1024–1043.

Deemer, E., Ogas, J., Barr, A., Bowdon, R., Hall, M., Paula, S., … Lim, S. (2021). Scientific research identity development need not wait until college: examining the motivational impact of a pre-college authentic research experience. Research in Science Education , 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-021-09994-6

Department for Education. (2014). The national curriculum in England: framework document. London: Department for Education. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-framework-for-key-stages-1-to-4 . Accessed 1 July 1 2017.

DeWitt, J., Archer, L., & Mau, A. (2016). Dimensions of science capital: exploring its potential for understanding students’ science participation. International Journal of Science Education, 38 , 2431–2449.

Dijkstra, E., & Goedhart, M. (2011). Evaluation of authentic science projects on climate change in secondary schools: a focus on gender differences. Research in Science & Technological Education, 29 (2), 131–146.

Driver, R. (1983). The pupil as scientist? Milton Keynes: Open University Press.