Search Google Appliance

How to do oral history.

Oral history is a technique for generating and preserving original, historically interesting information – primary source material – from personal recollections through planned recorded interviews. Below are suggestions for anyone looking to start recording oral histories based on best practices used in the Smithsonian Oral History Program at the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Click here for a printout of our How to Do Oral History Guide .

What is oral history.

The Six R’s of Oral History Interviewing

Preparing for Oral History Interviews

How to ask questions in oral history interviews, suggestions for recording oral history interviews.

Suggested Topics/Questions for Oral History Interviews

After the Oral History Interview

Readings and online resources.

Oral history is a technique for generating and preserving original, historically interesting information – primary source material – from personal recollections through planned recorded interviews. This method of interviewing is used to preserve the voices, memories and perspectives of people in history. It’s a tool we can all use to engage with and learn from family members, friends, and the people we share space with in an interview that captures their unique history and perspective in their own words. Oral history stems from the tradition of passing information of importance to the family or tribe from one generation to the next. In the United States, the Oral History Association connects oral historians and provides a broad range of information on oral history.

Technique : The methodology of oral history can be adapted to many different types of projects from family history to academic research projects in many different disciplines. The interviews should usually be conducted in a one-on-one situation, although group interviews can also be effective.

Sharing: In collaboration with a well-prepared and empathetic interviewer, the narrator may be able to share information that they do not realize they recall and to make associations and draw conclusions about their experience that they would not be able to produce without the interviewer.

Preserving : Recording preserves the interview, in sound or video and later in transcript for use by others removed in time and/or distance from the interviewee. Oral history also preserves the ENTIRE interview, in its original form, rather than the interviewer’s interpretation of what was said.

Original historically important information : The well-prepared interviewer will know what information is already in documents and will use the oral history interview to seek new information, clarification, or new interpretation of a historical event.

Personal recollections : The interviewer should ask the narrator for first-person information. These are memories that the narrator can provide on a reliable basis, e.g., events in which they participated or witnessed or decisions in which they took part. Oral history interviews can convey personality, explain motivation, and reveal inner thoughts and perceptions.

Martha Ross: The Six R's of Oral History Interviewing

The oral history interviewer should strive to create a situation in which the interviewee is able to reflect widely, to recall fully, and to associate freely on the subject of the interview, and to maintain an atmosphere in which they are willing to articulate fully those recollections.

The following six considerations are basic to good oral history practice.

1. RESEARCH: Thorough preparation enables the interviewer to know what questions to ask and is essential to establishing rapport with the interviewee. Research pays off during the interview, when the interviewer’s knowledge of names, dates, and places may jog the interviewee’s memory.

2. RAPPORT: Good rapport is established with the interviewee by approaching them properly, informing them of the purpose of the project, and advising them of their role and their rights. A pre-interview call or visit to get acquainted and discuss procedures is recommended.

3. RESTRAINT: The experienced interviewer maintains rapport by following good interview techniques: being efficient but unobtrusive with equipment, starting at the beginning and proceeding chronologically, asking open-ended questions, listening closely without interrupting, following up on details or unexpected avenues of information, challenging questionable information in a non-threatening way, and generally maintaining an atmosphere in which the interviewee feels able to respond fully and truthfully.

4. RETREAT: Close each interview session by asking a “deflationary” question, such as an assessment of the experiences just discussed. All sessions should be planned and scheduled so that they conclude before the interviewee becomes fatigued.

5. REVIEW: Interviewers should listen to their interviews soon afterwards to analyze their interviewing techniques and to pick up details to follow up on in subsequent sessions.

6. RESPECT: Respect underlies every aspect of oral history – respect for the interviewee as an individual, their experience, for the way they remember that experience, and for the way they are able and willing to articulate those recollections. Maintaining respect toward the individual interviewee and toward the practice of oral history interviewing is essential to success as an interviewer.

NOTE: Martha Ross is the “mother” of oral history in the mid-Atlantic region and taught at the University of Maryland in the 1970s and 1980s.

1. Select an interviewee.

2. Ask the interviewee if they are interested.

3. If interviewee is interested, set up a time and place for the interview. Also request any background information the interviewee might want to provide. Check about the best place – somewhere quiet where you won’t be disturbed. Request at least two hours for the interview session.

4. Write a follow-up email confirming plans for the interview that discusses the goals, legal rights, and how the interviews will be handled. Provide a very general list of topic areas and ask them to think about topics they would like to cover.

5. Conduct basic biographical research on your interviewee. Conduct internet searches. Read publications and profiles. Ask others about topics you should cover, stories they should tell.

6. Develop a chronology of the important events in their life. Develop lists of personal names and terms important in their life, such as geographic names where they traveled, names of important family or community members. Compile a folder of photographs of the interviewee and their world. These will prove invaluable in the interview when the interviewee gets confused or forgets names.

7. Rework the question outline, making it relevant to this interviewee, deleting topics that don’t pertain to them, and adding areas, such as organizations they were involved in, etc.

8. With the equipment, PRACTICE, PRACTICE, PRACTICE until you can use it in your sleep. Practice interviewing family members and friends. Then delete all the files you’ve created, so the recorder is at full capacity. Make sure all the settings match the instruction sheet. Make sure that you have all the necessary pieces of equipment, such as the recorder power cord and an extension cord.

9. The day before the interview, confirm time and place.

10. Bring with you: equipment, extension cord, cell phone (in case of equipment problems), question outline, chronology, terms, photos, etc., legal forms, extra paper for notes and a pen. Also bring throat lozenges or hard candy, in case throats get dry. If possible, bring a camera and take photograph of the interviewee at the interview.

11. When you arrive, assess room for sound. Turn off equipment, close doors, and rearrange furniture into a comfortable arrangement facing each other close enough to hand photos but not too close. Set up equipment so you can monitor it constantly and discretely, without turning away from the interviewee.

12. Go over the list of topic areas again and permissions again.

13. Ask about any scrapbooks, news clippings, awards, etc., that they might want to bring out.

1. Find a quiet place to conduct the interview where you won't be bothered by telephones, family members, pets, traffic noise, etc. Get two glasses of water. Take a photograph. Turn off cell phones, etc.

2. Explain to your interviewee what you are doing.

Explain their legal rights. Explain how interview is likely to be used. Explain that they can choose what questions to answer and that the recorder can be turned off at any time.

3. Ask your interviewee to sign the deed of gift and cosign it yourself if you have one.

4. Use an outline of topics you wish to cover, with follow-up questions, that you have prepared in advance. Also bring photographs and a personal name and term list, and chronology.

5. Start with easy questions, such as their name, where and when born, names of family members.

6. Allow the interviewee to do the talking.

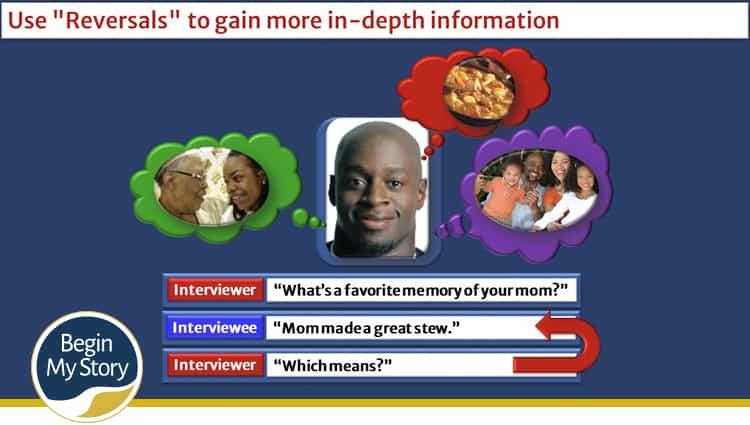

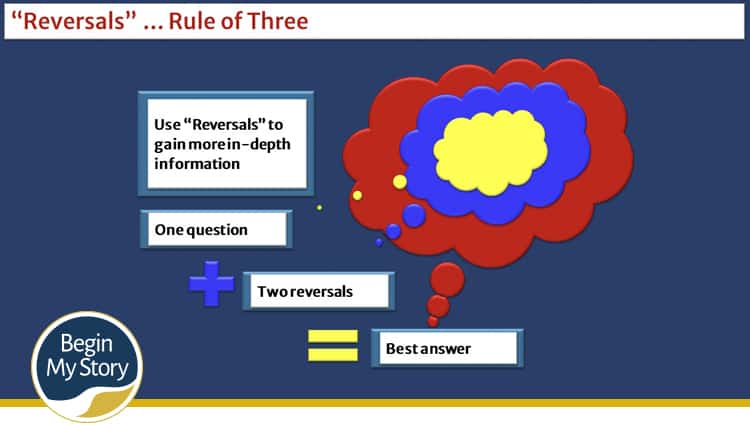

7. Ask "open-ended" questions, such as, tell me about, describe, etc., what do you remember about?

If the interviewee responds with just a yes or no, ask how, why, when, where, who. What the interviewee chooses to tell you and how they choose to tell it is just as informative/revealing as the actual answers they give.

8. Avoid “closed-ended” questions that can end in a yes or not, or single fact.

Examples, were you there? What was date of that? Did you like that? If you get a short answer, follow up with tell me more, who, what, when, where, how and why.

9. Do not ask leading questions – was it this or that? Or I thought that the most important thing was…..These have been demonstrated to affect interviewee’s answer and will taint your interview.

10. Ask one question at a time and try to ask simple questions.

11. Try to ask follow-up questions – tell me more, who, what, where.

12. To stimulate their memory, use “statement questions” such as, “In 1956, you traveled to Tibet to conduct research. How did that trip come about?”

13. Focus on recording their personal experiences, rather than stories about others or that they have heard. If you’re getting general stories, say tell me about your role, describe how you felt that day or dealt with that crisis, etc.

14. Don't worry about silences. Let the interviewee think and take time before they answer. Look at your outline and check off topics if the interviewee needs time to think.

15. Note what types of questions your interviewee responds best to and try to adapt your style to what works best with them.

16. Let the interviewee suggest topics to you that you might not have thought of.

17. Allow the interviewee to drift off to topics not on your outline. These can be the best part of your interview.

18. After an hour or less, ask interviewee if they would like to take a break. Write down the last words as you turn the recorder off.

19. Provide the interviewee with feedback by nodding, smiling, listening attentively. Try to avoid too many verbal responses that will record over the interviewee, such as “Really!’ or “Uh-huh, uh-huh.”

20. Don’t be afraid to politely question information that might be incorrect – ask for a clarification, or say something to the effect, “Oh, I’m confused, I thought that Mrs. X was involved in that.”

21. Reword questions that the interviewee does not answer – they may not have heard what you thought you asked. But they have the right to not answer if they don’t want to.

22. Do allow the interviewee to tell “THE STORY.” Most interviews have a favorite story. They will fit it in somehow, so let it happen! Allow some repetition since additional details may emerge with a second version, but don’t allow your interviewee to keep telling the same story over and over.

23. Bring visuals, if possible, to stimulate memory or ask to bring out photo albums of trips or family events, etc. Invite the interviewee to bring visuals to the interview.

24. Let the interviewee do the talking. Try to avoid telling your own stories, “Yes! When I was there….” or offering your own opinions. If asked for an opinion, explain that the interview is designed to record their point of view, not yours.

25. An interview usually does not last much longer than 1 1/2 to 2 hours. After that both interviewer and interviewee get tired and lose their concentration.

26. End interview gracefully, asking them to assess their lives and the topics you have discussed.

27. Ask your interviewee to spell any names or places you did not understand.

28. Clean up. Make sure you have all pieces of equipment.

29. As you depart, keep options open to return for an additional interview.

1. There are many recorder options that will record an uncompressed preservation quality audio file. If you do not have access to a recorder, most smartphones have recording software that will record an MP3 audio file.

2. If possible, record an uncompressed WAV audio file at 24 bit.

3. Use external microphones if possible.

4. Check room for extraneous noise such as motors, fans, pets, traffic, etc.

5. Test the recorder to check the volume of the interviewer and interviewee and to see if it is picking up any static or surrounding noise.

6. Begin with an introduction that identifies who is being interviewed, who is conducting the interview, where, when, and the purpose of the interview.

7. Ask if you have permission to record the interview.

8. Avoid speaking while your interviewee is sharing. Instead, try to use physical cues that you’re listening like nodding and taking notes instead of affirming “mhmms.”

9. Upload the files from the recorder to your computer, external hard drive and/or the cloud to ensure you don’t lose the file.

10. Name the file in a way you can identify it later. Ex: LastnameFirstname_Date_Interview#_File#

11. Make copies of your digital file. Save a copy to an external hard drive and/or the cloud.

Suggested Topics/Questions for Oral History Interviews

1. What is your full name?

2. Do I have permission to record this interview?

3. Where and when were you born?

4. Who else was in your family?

What were your parents’ names? Are there any traditional first names in your family? What type of work did they do?

5. Did other family members live nearby?

Tell me about them. How did they meet? What did they do for a living? When did you get to see them?

6. What did your community look like outside of your family?

How did you meet them? What types of activities would you do together? Tell me about your neighborhood.

7. Where did your ancestors come from?

When did they come to the United States? Where did they first settle? Did your family name change when your family immigrated to the United States? Are any of their traditions still carried on today? What language did your parents and grandparents speak?

8. What games did you play when you were young?

What toys did you have? Who did you play with? Where did you play? Did you have any hobbies? Have your hobbies and interests changed over time? Did you collect anything? Baseball cards, dolls, etc.

9. Tell me about your grammar and high school education?

Describe your grammar school/high school. What subjects did you study? Tell me about your interests in your school days. Did you have any influential teachers? Any leadership roles in organizations/classes? What were your hobbies and interests as a child? Did you read much, if so, what topics? Did you belong to any influential clubs or organizations? Did you have any goals/dreams for when you grew up? How did gender roles affect you during K-12 education?

10. What holidays did your family celebrate?

How did you celebrate them? What was your favorite part of the holidays?

11. Tell me about the house you grew up in.

How was it furnished? Did you have your own room? Where did you spend most of your time? Did you move to another home while you were growing up? Tell me about the new home. How did your community change?

12. What were mealtimes like in your family?

What foods did you eat? Who cooked the food? Who cleaned up after meals?

13. Did you have any pets? Describe them.

Who took care of them?

14. What type of clothes did you wear?

Where did you get them/who made them? When did you get new clothes?

15. How did your family get around?

Did you have a car? Did you use public transportation? If you had a car, when did you get it? Who drove it? Did you go on vacations in it? When did you learn to drive? Describe your first car. What kind of public transportation was available?

16. What sort of entertainment did you like?

What did you listen to growing up? Did you watch TV growing up? What did you watch? What large moments do you remember watching on TV?

17. Who was your family doctor? Describe them.

Do you remember any epidemics or diseases? Did your family have any home remedies? If so, describe.

18. What was your first job?

Describe a typical work day. How much money did you earn? How long did you have that job? What lessons did you learn? Additional jobs and details – trace career path, changes Tell me about any influential mentors. What were the most memorable aspects of that position?

19. Did you attend college?

Tell me about your college years. What school? How did you decide to go there? What was your major? Any influential mentors? Did you do a semester abroad? Describe your major interests? What were successes/accomplishments and challenges/frustrations? Tell me about any gender challenges you encountered in college.

20. How have historic events, such as 9/11, hurricanes, the Great Depression, world wars, natural disasters, strikes, and now Covid-19 etc., affected you?

Did these events impact your community?

1. Download interview files onto your computer, following the instructions provided.

2. On your computer, rename each file by right clicking on file and selecting rename. Rename it in this format: LastnameFirstname_Date_Interview#_File#, for example, JonesSandra_04-30-2020_1.

3. Click on file to be sure it plays properly.

4. Do not erase files from your computer until you have made duplicates.

5. Erase files from recorder, so the recorder will be empty for next interview.

6. Write a one paragraph summary of what the interview is about, providing technical details. Also list a dozen or so name and subject terms for indexing. This will be used to identify the interview for future use.

7. Prepare a longer list of all names, terms, etc. to use for transcription.

8. Prepare an introduction for the transcript that provides an overview of the interview for the reader and helps them understand what they are about to read. The introduction should include an opening paragraph that states why the individual was selected, i.e., the special significance or accomplishments of the individual; information as to the place and particular conditions of the interviews, e.g., the interviewee’s home or office; research the interviewer did to prepare for the interview, i.e., books read or scrapbooks reviewed, and any prior relationship of special affinity between the interviewer and interviewee, e.g., friends for 25 years, grandchild or child. The interviewer should also prepare a biography of one or two paragraphs about themselves, including background and experiences of the interviewer related to the conduct of this particular interview.

9. Photocopy or scan the signed legal form, your question outline, chronology, etc.

10. Write a follow-up note to the interviewee, thanking them for their time and reminiscences.

Abrams, Lynn. Oral History Theory, second edition. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Boyd, Douglas A. Oral history and digital humanities: voice, access, and engagement. Springer, 2014.

Frisch, Michael. A Shared Authority: Essays on the Craft and Meaning of Oral and Public History. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990.

Gluck, Sherna Berger, and Daphne Patai, eds. Women's words: The feminist practice of oral history. Routledge, 2016.

Murphy, Kevin P., Jennifer L. Pierce, and Jason Ruiz. "What Makes Queer Oral History Different." The Oral History Review 43, no. 1 (2016): 1-24.

Neuenschwander, John A. A guide to oral history and the law. Oxford University Press, USA, 2014.

Perks, Robert and Alistair Thomson, The Oral History Reader, third edition. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Ritchie, Donald A. Doing oral history. Oxford University Press, 2014.

Thompson, Paul. The voice of the past: Oral history. Oxford university press, 2017.

Oral History in the Digital Age https://www.oralhistory.org/oral-history-in-the-digital-age/ Oral History Association website, covering every aspect of oral history, from family and community oral history to academic oral history projects.

Smithsonian Folklife and Oral History Interviewing Guide https://folklife.si.edu/the-smithsonian-folklife-and-oral-history-interviewing-guide/smithsonian Contains guidelines Smithsonian folklorists have developed over the years for collecting folklife and oral history from family and community members, with a general guide to conducting an interview, as well as a sample list of questions that may be adapted to your own needs and circumstances, an information on preservation and use.

Oral History Association: https://www.oralhistory.org/

Oral History Discussion List: H-Oralhist http://www.h-net.msu.edu/~oralhist/ is the oral history discussion list.

Library of Congress, Oral History Lesson Plans http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/lessons/index.html#topic230

Vermont Folklife Center, Oral History Guide https://www.vermontfolklifecenter.org/events/oral-history-an-introduction

Guide to Conducting Oral History Interviews (Comprehensive)

- Categories: Research for Storytelling

- Tags: featured , Oral history interviews

A complete guide for conducting oral history interviews for storytelling.

Of all the various opportunities I have to research and write narratives, the most important and productive research was when I conducted oral history interviews. When we talk about the oral history interview, we closely associate the topic with writing individual and family narratives. In this “Complete Guide for Conducting Oral History Interviews for Writing Narratives,” I will present the oral Interview and oral history as one topic under the umbrella of oral history.

The difference between writing mediocre and a great narrative is planning, researching, and carefully stitching the memories and artifacts into a cohesive blend of resources to tell the story that will inspire generations to come.

In the beginning. Shortly after my mother’s passing 25 years ago, I began the process of conducting interviews with her (Mary’s) immediate family, friends, and others who knew her. As time continued, I expanded the oral history research to include my mother’s and father’s immediate and extended family. When I completed the task 4 years later, I had gathered information spanning 100-plus years of memory, 160+ hours of interviewing, have received physical or digital copies of thousands of family images, writings, and artifacts related to those interviews. Throughout this guide, I will refer to some of my experiences in conducting these oral history interviews.

This guide is based on my personal and professional experience in interviewing hundreds of people and writing thousands of narratives over the last several decades. The following are the topics that will be covered in this guide:

- What are Oral History Interviews?

- What I Learned in the First Ten Oral History Interviews

- How to Begin Preparing for the Oral History Interview

- Oral History Interview Considerations

- How to Set-up the Oral History Interview

- How to Correct Oral History Recording Noise Problems

- Getting Ready for the Oral History Interview

- How to Conduct an Oral History Interview

- Use Open-Ended Questions in Oral History Interviews

- How to Get the Best Answers in Oral History Interviews

- How to Take Care of Recorded Oral History Interview

- Documenting Oral History Interview and Narrative

Other resources to consider include:

- Complete Guide to Writing A Personal Narrative

- 7,500-plus Questions About Life to Ask People When Writing Narratives

Every life is important and unique. It’s about the people known, the places visited, the decisions made, the opportunities lost or gained, and the spiritual, physical, and mental vitality and folly. If your life is essential to you for no other reason, and that is reason enough to write a personal narrative.

Please do not underestimate your value and how essential your narrative will be to you and those who will read it. So often, I have heard people say, “I wish that my grandparents had written a personal narrative/history,”? We have many questions about those who have gone before us. The narrative you write will be among the most prized possessions you give to others.

Return to list of topics for Complete Guide for Conducting Oral History Interviews.

1.What Are Oral History Interviews?

The oral history interview is the collection and recording of personal memoirs as historical documentation. It emphasizes the significance of the human experience.

Oral history interviews are not the best method for obtaining factual data—such as specific dates, places, or times—because people rarely remember such detail accurately. Instead, you will need to use more traditional historical research methods—courthouse records, club minutes, newspaper accounts, and so forth—to help fill in these gaps.

Oral history interviews are the best method to get an idea of what happened, what those times meant to people, and how it felt to be a part of that time.

Oral history interviews are great for capturing eyewitness accounts and reminiscences about events and experiences that occurred during the lifetime of the person being interviewed and for gathering narratives passed down verbally from generation to generation beyond any individual’s lifetime. This includes stories, songs, sayings, memorized speeches, and traditional accounts of past events.

Oral histories provide an added dimension to historical research. An oral history project can aid your research in the following ways:

- Foster appreciation for little-known or rapidly vanishing ways of life.

- Verify the historical nature of events that traditional methods of historical research cannot determine.

- Correct stereotypical images of life, ways, and people.

- Recover and preserve essential aspects of a human experience that would otherwise go undocumented.

What are the types of oral history interviews?

There are four basic types of oral history interviews. They include:

Life histories. These are oral interviews with individuals about their backgrounds from childhood to adulthood. Most of these oral interviews follow a chronology in time. Life histories provide an opportunity to discuss various subjects based on the interviewer’s interests and the interviewee’s remembered experiences and perspectives. They are ideal for writing narratives and learning about family.

Topical histories. These oral interviews are often used for focused studies of particular events, eras, or organizations. Examples include discussing the Depression Era in the local county/community or about an event like a flood, mudslide, or storm that devastated a community. An oral study about World War II in a specific locale, for example, might include interviews about military involvement, civil defense preparedness, the home front, rationing, bond and scrap metal drives, war industries, and myriad related topics.

Thematic histories. These studies focus on broad patterns and concepts. These themes could include love, conflict, hope, religion, education, competition, success, or art. Thematic oral histories are not common, but they present opportunities worth considering.

Histories to document specific artifacts or sites. Oral history interviews may be used, for example, to explain items within a museum collection— how to churn butter, how to operate a Farmall F-12 tractor, how to use a Victrola, how to dress for travel in the 1940s. Another method is to have a subject orally document the history of an individual home, a particular street, an old schoolhouse, a vacant field or an overgrown cotton patch.

2. What I Learned in the First Ten Oral History Interviews

During my mother’s funeral and memorial services, I had many people tell me about their experiences with Mary as a youth, as an adult, and at work. They told me about her service and reshared her thoughts and pride for my siblings and me. I longed to know more about my mother. I realized that I knew very little about my mother. I felt a genuine sorrow and emptiness for wanting to learn more about my mother.

Whenever I asked Mom (Mary Schreiber) about her life while living, she replied that it was hard and nothing more needed to be said. Because of my need and desire to learn about my mother, I awkwardly yet earnestly began reaching out to people my mother knew to see if they would allow me to interview them about my mother. Every person gladly agreed. So within three months, I began conducting oral history interviews. The journey started with my conducting oral interviews with family, friends, co-workers, and my mother’s acquaintances. I expanded the project also to include discussions related to my father. Over six years, I conducted over 160 hours of oral history interviews.

The first ten oral history interviews were more than people simply answering my questions. They were individuals who had respect, love, and insight into Mary as a mother, friend, and sister. I was discovering the Mary Schreiber I was never privileged to know thoroughly. I loved my mother before, but I loved her even more following the interviews. This group of ten people held the keys to every stage of my mother’s life. They answered my questions honestly, directly, and without any reservation. As a result of the interviews, I learned about the following aspects of my mother’s life:

- Cherished experiences they shared with Mary

- Traits they admired about Mary

- Innermost thoughts Mary shared with them about her life and family

- Her dreams that were dashed by choices in marriage

- Dark, troublesome times of pain and sorrow that was triumphantly overcome

- My heritage and roles of progenitors in preparing a path for me

- Family rifts that were three generations deep

- Identification of photos and other artifacts

- Individuals and families from my heritage whom I should learn more about

- “Skeletons” that were long since buried

- Precious artifacts (photos, cards, letters, scrapbooks, journals) that were given to me to keep or to scan

- Artifacts that existed and where I could find them

There were two important takeaways from those first ten oral interviews for anyone just starting to conduct oral history interviews about individuals or family members. They include:

Conduct oral history interviews with immediate family members

Take time to interview and compare your memories with those who have direct knowledge about the person. This can include siblings, parents, cousins, grandparents, and others. Oral history is about people, who they were, and the stories of their lives. People often share that they want to learn more about individuals and their family heritage.

I will respond with questions like, “What is keeping you from talking to your family?” The replies vary from

- I don’t know how or where to start.

- I don’t get along with some of my family.

- I don’t have time.

- I will wait till I am retired.

I try to emphasize by sharing that those were my feelings exactly. Then I briefly share my experience with the death of my mother and my need to know more. I conclude by gently encouraging them not to wait until after a relative passes on to find information or conduct oral histories. Someone in the family has excellent information. People will and want to talk to you. Because you are willing to take the effort and ask questions, people will go out of their way to help answer your questions and share information and artifacts (e.g., photographs, letters, scrapbooks, journals, video, and more) related to your quest. Rest assured that your family will answer your questions and insights that will be invaluable to writing a narrative, story, or memoir.

Oral interviews provide opportunities to locate family records

Oral interviews provide opportunities to locate, identify, catalog, and preserve artifacts significant to the family and why those items are essential. Artifacts can include heirlooms (such as furniture, small collectibles, and photographs), manuscript materials (diaries, letters, and family bibles), and copies of public records (certificates of birth, marriage, death, land, patents, and wills.)

Of the more than 60,000 artifacts I have gathered relating to my mother and father and their ancestral lines, 75 percent have come from interviews with family. Once I was made aware of available information, I was permitted to scan or photograph the artifacts. In several instances, I was given the life-long research of the person I was interviewing because I had an interest shared by anyone else.

3. How to Begin Preparing for the Oral History Interview

It is natural to want to rush out and start the interview process, but no project should begin without some essential investigation of available resources. I found that by gathering and organizing material, I was able to gain an excellent insight into which direction I should go and what questions I needed to ask. As you prepare, you may need to review other artifacts, such as old newspapers, county histories, archival records, cemeteries, and photographs.

Who should I include when writing an individual or family narrative?

Include family and friends of the person whose narrative you are writing. Involving family and friends in writing a personal, individual or family narrative will make the process more accessible (and the result more interesting). Still, it will also help ensure that you have an audience of interested readers connected to the completed work. Start the process of involving family and friends by sending them a letter or email signed by the subject of the narrative, if available. These communications are most effective if, at a minimum, they accomplish the following:

- Introduce the narrative writing project and explain the desired time frame for completion.

- Share that you will be reaching out over the next several months to request and schedule time for an oral history interview.

- Ask the recipients to collect photos, stories, and memorabilia that might be appropriate for use in the completed narrative.

- Offer to pay for any copies and other costs they incur in assisting you.

- Ask family members to contribute their favorite stories concerning the subject.

- If writing a letter, include a self-addressed, padded envelope and “advance reimbursement” for the out-of-pocket costs they will incur in assisting you.

Who should I interview for the narrative?

Start by creating an acquaintance list. For Mary, my mother, I brainstormed a list of family, friends, and acquaintances who I knew. The list started with 20 names. This will grow over time. As I conducted interviews, I was introduced to new people with whom I should meet.

Who should I interview first? I organized Mary’s list of family, friends, and acquaintances into the following three groups:

- Group One: Family and friends she spoke with often during the last five years of her life.

- Group Two: Family, friends, and acquaintances appeared (in artifacts) at critical moments in her life (for example, bridesmaids at her wedding).

- Group Three : Family, friends, and acquaintances in everyday activities with her, such as a friend’s birthday or a group picture in the cafeteria.

I began with Group One, which consisted of ten people. I prepared for the interviews by developing a few general, broad questions that would help uncover information about each period of my mother’s life and call each person to set up the Interview.

4. Oral History Interview Considerations

Before I get into the actual details about how to set up and conduct oral history interviews, I would like to address essential choices such as

- Where to Conduct the Interview

- Type of equipment to consider and use

How many people should I interview at a time?

When you have an option, choose to interview the person in their own home. It is by far the best option, as the interviewee will be much more relaxed. A one-on-one interview is best. Privacy encourages an atmosphere of trust and honesty. A third person present, even a close partner, can inhibit and influence the free discussion.

Should I audio record or video record an oral history interview?

I would say that 85% of my interviews are done with audio recordings. When possible, I like to use both the audio recorder and video for interviews. However, the choice may not be yours. Sometimes, a person who is comfortably sitting and talking into a digital recorder will cringe at the thought of being on a video recording. If you’re uncertain, ask the interviewee. Whether using audio or video is more convenient for you, you’ll get the most from an interviewee who is comfortable with the environment. Getting their Interview is most important.

Do I need to record the oral history interview?

Because you can’t write down everything that someone tells you, it is a good idea to use an audio or video recorder. Over the years that I have conducted interviews, I have found that recording the Interview leaves me free to focus on the discussion. The only notes I took were thoughts that came during the discussion about further questions to ask or expand upon.

Your recordings will be unique historical documents that other people need to hear and understand quickly, so it’s worth getting a good-quality recording. When you record, you can focus on the Interview and worry about writing down notes and deciphering them later.

When should I conduct telephone oral history interviews? I did say that the interviews are in person. However, I would say that 50% of my oral history interviews have been over the phone. Why? I simply lived too far away from the interviewee.

Recording an Interview via Telephone. The FCC protects the privacy of telephone conversations by requiring notification before a recording device is used to record interstate (between different states) or international phone calls. I always ask the interviewee if I can record the call and have their answer on the recording. If they say, no, then I shut off the recording. Interstate or international telephone conversations may not be recorded unless the use of the recording device meets the following requirements:

- Preceded by verbal or written consent of all parties to the telephone conversation; or

- Preceded by a verbal notification that is recorded at the beginning, and as part of the call, by the recording party; or

- Accompanied by an automatic tone warning device, sometimes called a “beep tone,” automatically produces a distinct signal that is repeated at regular intervals during the telephone conversation when the recording device is in use.

Also, a recording device can only be used to be physically connected to and disconnected from the telephone line or if it can be switched on and off.

What type of equipment do you need for a telephone oral history interview?

There are many ways and apps to use when recording a telephone call. I used the following equipment and resources for interviews because they have proven to the most reliable:

- A digital-cassette player like the Sony ICD-UX570 Digital Voice Recorder.

- A microphone that I could place under the earpad like the Olympus TP-8 Telephone Pick-up Microphone. The microphone is on the outside of the earplug.

- Headset like the Plantronics Blackwire C3220 Headset for clear communication. My headset is the “Plantronics Voyager Focus UC Bluetooth USB B825 202652-01 Headset with Active Noise Cancelling” which I use also use for work.

- List of questions for Interview.

- Note pad to record thoughts, requests, and promises.

- Computer to save my digital recording afterward.

Before each interview, I made sure the recorder worked and the lines were clear. If you haven’t used a recorder for interviews before, it is imperative that you practice recording and asking questions so you know your equipment and questions. That way, if you have any problems, you will have time to research and make corrections.

Can I use video conference software like Zoom for remote oral history interviews?

Yes. Zoom and other video conferencing software can be an excellent alternative to in-person and telephone-only oral history interviews. However, as the narrator/interviewer, you will need to have some essential practice on using the software and how to help the interviewee set up software on their end.

Pre-interview with Interviewee. Don’t assume you will set up an interview and jump on video conferencing software like Zoom and conduct a video oral history interview. While you may have had the experience of multiple interviews, your interviewee will not have had this experience. I suggest you set aside some time to become acquainted with the software and work out the technical aspects. Set up a pre-interview meeting with the interviewee. During the meeting, you can discuss how the interview will progress, set up both interviewer and interviewee computers, and make adjustments for sound, recording, camera, bandwidth speed of internet connection, and quiet room with little or no noise.

Choose a quiet, well-lit room . As the interviewer, you must find a quiet, well-lit, and relatively quiet room. The following is a checklist of considerations when recording.

- Room smaller than 12 feet x 15 feet. Home office or den with carpet or plush services.

- Make sure the room is well. I like having an incandescent or table lamp. I am looking to have a light that will show both sides of my face. Overhead lighting tends to leave dark shadows on a person’s face.

- Ensure your computer or another camera you are using does not face the window or direct light source. Close the blinds or find another space.

- Sound can bounce off walls and give you an echo effect. To reduce this effect, I like rooms with a mix of features like carpet, plush soft surfaces, plush/stuffed furnishings, bookcases, etc., which help to absorb sound.

- Listen for noise such as fans, clocks, refrigerators, animal sounds like barking, outdoor sounds (close windows).

- Close blinds or shield computer camera from direct sunlight.

- Listen for other sounds coming from other rooms that can be heard and affect recording quality, such as flushing toilets, feet on the wood floor, fluorescent lighting, walking upstairs, talking, animal sounds like barking, clocks, fans, refrigerators, and more. Where possible, seek to minimize these sounds like asking the family to be in a different room while you are recording, using a different bathroom, not running the lawnmower, taking off shoes, and so forth.

- Do not use artificial digital backgrounds. They look fake and can be irritating for the interview to watch.

- Check your background. Less is more. By this, I mean, stay away from busy backgrounds. A bare wall is ok, but a painting or bookcase on the screen is better.

Recording equipment. When you are conducting a video interview, you need to be aware it takes more than simply opening your computer and turning on Zoom or video conferencing software. Consider the following:

- Laptops with built-in cameras and microphones ideal. Tablets with the same configuration are also appropriate.

- I like to use headphones with a built-in mic. The headphones help block out sound, help me contrate on the interview, and improve my voice with the mic. For example, a headset like the Plantronics Blackwire C3220 Headset for clear communication. My headset is the “Plantronics Voyager Focus UC Bluetooth USB B825 202652-01 Headset with Active Noise Cancelling,” which I use also use for work.

- Listen for mic rub. This is where your mic rubs against clothing and delivers a scratchy sound. Avoid clothing with turtlenecks, large jewelry, scarfs, and large stiff collars.

- Shut off all apps on your computer. Close as many tabs as possible from your browser.

- A good quality Zoom or video conferencing call needs a minimum download/upload speed of 75/9 MBPS (megabytes per second). If you have connections, try turning off Wi-Fi devices in the home and minimize video streaming by others such as the TV, phones, etc. You can find your intent speed by doing a Google search on the term “Internet Speed Test.”

- Beware of internet bandwidth. Bandwidth has to do with how much information your internet can upload and download. Many neighborhoods run off the same cable provider internet system. Reduces speed can cause an issue like stalled video images, breakup voice, etc. If this is happening, consider moving your interview to a time in the evening when there is less internet use. If you have fiber optic connections, you should be fine.

- I use a digital record digital-cassette player like the Sony ICD-UX570 Digital Voice Recorder for backup and a microphone that I could place under the earpad like the Olympus TP-8 Telephone Pick-up Microphone. The microphone is on the outside of the earplug.

Interview. At the designated time you set up for the interview, join the zoom or video call you had set up. Before the interview, you should have had practice sessions of setting up the Zoom meeting, recording, etc. For more information about how to set up Zoom or other video conferencing software, do a Google search on terms like:

- Zoom for oral history interviews

- Zoom for interviews.

- How to set up Zoom for interviews

As a best practice, I will do one or more of the following methods to make sure I have a backup of the oral history interview.

- A digital-cassette player likes the Sony ICD-UX570 Digital Voice Recorder.

- A microphone that I could place under the earpad like the Olympus TP-8 Telephone Pick-up Microphone. The microphone is on the outside of the earplug. See recording equipment.

- On your laptop, use screen recording software to record the session.

What do I need to know about digital recorders?

Not all digital recorders are suitable for interviews. Avoid those that use proprietary software—for example, “personal recorders” that create files that can only be used with the manufacturer’s software. You are dependent on such software for listening to the sound and copying it. The typical price range for a digital recorder suitable for oral history is between $75 to $500. It comes down to the bells and whistles.

Minimum recording requirements for all digital media, including computers, are as follows:

- 44.1 kHz—minimum sampling rate

- 16 bit—minimum bit depth

Can I use an analog tape recorder for recording the oral history interview?

My personal choice would be NO. If I had this question in 2010, I would have said sure, go for it. In 2010, the recorders cost $50 to $100, those same microcassette recorders list for $300 to $600. I recently had to look for one such recorder to play 50 microcassettes that I had recorded at one time.

If you choose to use a tape recorder, you will still need to digitize the recording. Ensure you have a professional-quality tape recorder with an external microphone, and high-quality cassettes should be used. If you have a suitable tape recorder that has not been used for a while, take it to a technician for a maintenance check.

Features to look for in a tape recorder include the following:

- Controls that allow you to play the tape (PLAY), wind back the tape (REWIND), wind the tape forward quickly (FAST FORWARD), RECORD, STOP and EJECT

- A tape counter, which allows you to find your place within the tape by denoting a numerical location

- A jack socket for an external microphone

- Recording-level volume control allows you to adjust the volume at which you record

- A recording-level meter

- The option of using either a wall socket or battery power

- A jack socket for headphones

- A built-in speaker

How do I clean the recording head of a tape recorder? Cleaning your tape recorder with Isopropyl alcohol, which is 91 percent pure, applied with Q-Tips, will eliminate debris from all recorder parts that come in contact with the magnetic tape. Standard “rubbing alcohol,” which may contain some undesirable lubricants, should not be used because the ingredients may damage the rubber pinch-roller if applied regularly.

Cassettes tapes. The following are some tips to keep in mind when considering cassette tapes for recording your interviews:

- Use 60-minute cassettes for recording your interviews. They are thicker than the longer-playing ones and are less likely to stretch (and thus distort the sound) or break. Do not use 90-minute tapes or larger ones. Longer tapes are too thin and tend to bleed, stretch, or tear.

- Buy regular tapes, not metal or high-bias ones. The latter is designed for recording music and is too expensive for this purpose.

- It is a good idea to use cassettes put together with tiny screws in each corner instead of glue because if the tape jams or breaks, the case can be opened, the tape repaired, and the case put back together again. If you are using tapes without screws, you have to destroy the case to get to the tape if it jams or breaks.

- Use only name-brands of cassettes, such as Sony and TDK.

What should I use for microphones when conducting an oral history interview?

Whatever recorder you decide to use, it is essential to use an external microphone. If you are buying microphones, go for the best quality you can afford. An external microphone is preferred over one built into the recorder. A built-in microphone will record all sounds indiscriminately, including the noise made by the recorder itself. It is challenging to position a digital recorder with an inbuilt microphone to record all voices.

If you are buying only one microphone, you will need one with a stand, not one that has to be held. Hand-held microphones record any sound of the mic itself moving. Free-standing or table-top microphones are generally relatively unobtrusive and record both the interviewee and interviewer clearly if they are placed carefully. However, they often pick up an undesirable level of background noise.

Microphones pick up a range of noise in four patterns. The different types are as follows:

- Unidirectional or cardioid, which picks up sound in a heart-shaped pattern in one direction. They generally record the sound around them but not directly behind them. These are the best type to use.

- Omi-directional, which picks up sound coming from all directions.

- Bi-directional, which picks up sound from two opposite directions.

- Hyper-directional, which picks up sound from one direction only and has a very narrow field.

Microphones for indoor recording. For one-on-one interviews indoors, the best microphone is a small tie clip or lapel microphone. Lapel microphones tend not to record as much background noise as free-standing ones because the wearer’s body helps to absorb unwanted noise. Their only disadvantage is that most recorders do not have an input for more than one microphone, so while the interviewee is recorded clearly, the interviewer sounds very distant. There are two solutions to this problem: buy a recorder with two microphone input jacks, or buy a “split cord” which allows you to plug two microphones into one cord and then into the recorder. If your recorder is stereo and has two microphone sockets, you can get two microphones—one for your interviewee and one for yourself. They can be attached discreetly to your clothing and give excellent results.

Microphones for outdoor recording . For interviews done outdoors, a unidirectional (or cardioid) hand-held microphone is best, as it will pick up less unwanted noise. The ideal for interviews is to use two lapel microphones that clip onto the clothing of the interviewer and the interviewee. Electric condenser or dynamic microphones are perfect. Talk to someone at your local electronics shop (such as Radio Shack) or contact a manufacturer to determine what model would be best for your requirements. Tell them you will be recording voices, not music.

Should I use batteries, wall plugs or others with my recorder?

Most digital records come with an internal battery that will last for several hours. Make sure you bring along a way to recharge your recorder. Even better, bring an extra recorder if you can afford it if the one you are using fails for any reason.

If you use a recorder that uses batteries and has a wall plug adaptor, uses the wall adaptor first, allowing you to plug your recorder into an outlet. If you have to use batteries for your recorder, you will need a battery tester to ensure they are fully charged. I make it practice to fresh batteries for every Interview. If they are not fully charged when recording, the tape will slowly wind through the machine. When you play the recording at average speed, the voices may be distorted.

What more important, saving on batteries or getting a great, clean recording?

What should I use to carry my recording equipment?

A padded bag, such as a camera bag, helps carry your equipment and protect it from damage.

5. How to Set-up the Oral History Interview

The best way to approach someone you want to interview is by personal contact rather than by letter, and often the initial contact will be by telephone. This allows you to introduce yourself, explain your project, and outline the sort of topics you might cover in your conversation. The person you have approached may be uncertain or might feel they have nothing interesting to say, so you sometimes have to do a bit of persuading. The key is to talk in terms of “a chat about the past” or a “share a story” rather than an “interview,” which can sound intimidating.

How do I ask someone about participating in an oral history interview?

Once you have chosen the individuals with whom you would like to interview, I suggest you telephone them first. Only email them a second resort. Why? I find it much more personable to talk and have a conversation. If you can call or email, then send a letter. When I was working on my mom’s narrative, I sent emails to people and shared that I would like to speak with them about a story I was writing about my mom. I did not have anyone refuse to talk to me.

When you can talk to the potential interviewee, do the following:

- Introduce yourself.

- Explain why you are doing the project. Suppose the interviewee is a member of your family or someone you know very well. In that case, you will still need to explain the project, get their Agreement to record an interview, gather biographical information from them, and explain the other details listed here.

- Explain what you will be covering in the Interview.

- Explain that you would like to record the Interview.

- Explain what will happen to the Interview once you have finished it.

- Make an appointment to conduct the Interview and record it, preferably within a week.

- Explain your desire to find photos, documents, and so forth to help tell the story.

- Request their address or email address so you can write to them after they’ve had a few days to ponder your questions.

- Give the interviewee your name and phone number to contact in case they need to clarify anything else.

Note: If the person does not wish to be interviewed, thank them for their time. Do not try to persuade them to change their mind. Every time I had coaxed someone to interview when they first said no, I had had a less-than-acceptable interview.

How do I prepare for the oral history interview?

Preparing for an interview—whether it’s ten minutes or all day in length—requires careful planning, research, familiarity with your equipment, and establishing a good rapport with the interviewee. Consider the following as part of your preparation:

- Practice a couple of interviews before the real thing. Before you start recording, make at least one practice interview, preferably with someone you know, so that you are not afraid to make mistakes. This will give you practice in interview techniques and help you become confident in using your equipment. Practice setting up your equipment quickly and efficiently.

- Take the time to experiment with different recording levels on your machine and change the distance of the microphone from the interviewee so that you know the optimum positions for recording. You aim to make recordings in which both the interviewee and the interviewer are audible, with little unwanted background or tape noise.

Tip: Take some time to watch or listen to how professional interviewers conduct interviews on TV and radio. One of my favorite interviewers is Terry Gross of Fresh Air f rom NPR.

6. How to Correct Oral History Recording Noise Problems

When you record an oral history interview, you want your recording to be clean and crisp. Sadly, from my own experience, I have had too many recordings that marginal at best because of simple things that have muffled and distort the voices. I want to share what I have learned about recording and address common noise problems that can affect your oral history interview quality.

Listed below are some common noise problems and suggestions for their solution.

Hiss. It could be your air conditioning or fluorescent lighting. It could also be caused by recording at too low of a level. Turn up your recording-level volume. It can also be read the instructions carefully.

Hum. The microphone may be too close to the machine and pick up the recorder’s mechanical noise. Move the microphone away from the machine. Alternatively, the machine and microphone may be too close to a power source or near another electrical appliance. If so, move the machine and microphone. The wiring on your machine or microphone may be faulty. Have them serviced if you think this is the problem.

Whistle. This could be that you are too close to a speaker. Sound is being transmitted, amplified, and coming from the speakers, albeit low.

Distortion . Having the level set too high when recording digitally can cause clipping, unwanted distortion of the audio. While distortion happens in analog recording, the artifacts caused by digital distortion can be more severe.

- A popping noise when people say “p,” a whistle when they say “s,” or a sizzling noise when they say “t” occurs because either they are speaking too close to the microphone or the recording volume is too high. To fix these problems, change the microphone’s angle, move it further away, or turn down the recording level.

- If you are recording someone with a high-pitched voice, you may need to adjust the recording volume.

Echo. This results from recording in a room with few soft furnishings and no carpet, such as a kitchen. Because there is little to absorb it, the sound bounces off the hard surfaces and is re-recorded.

You can get around this problem by moving the microphone closer to the interviewee, placing it on a cushion to absorb the echo, drawing the curtains, or moving to another room. A lapel microphone is helpful because the interviewee’s body will absorb a lot of echoes.

The effect will prevent broadcast-quality recording but is acceptable for research purposes.

Microphone cable noise. This is crackling or clicking noise on the tape caused by the movement of the microphone cable, which usually happens if you are holding the microphone.

It is best to use a microphone stand while recording. Alternatively, place the microphone on some magazines or a cushion. If you have to hold the microphone while recording, wrap the cable around your hand.

Cable noise sometimes occurs when you use a clip-on microphone and the interviewee fidgets with it. If this happens, explain politely that this will muffle their voice on the recording and ask them to stop. You may wish to give them something else to play with; a rubber band is an ideal toy for restless fingers, as it makes no noise.

Recording outside . You should avoid interviewing outside because it is almost impossible to control the recording of background noise.

If you cannot avoid recording outside, you will need some sort of windshield for the microphone, either a foam-rubber one you can buy or something like a handkerchief or a few layers of muslin secured with a rubber band.

Try to place the recorder on the ground or a wall, as the motor speed may vary if it is hanging from your shoulder, causing the sound to be distorted when you replay the tape.

Other sounds to avoid include rustling paper, clicking pens, fluorescent lights humming, clocks are ticking, traffic noise, caged birds, dogs barking, and open fires. To avoid the first two, use a pencil and write your questions and notes on a notecard rather than paper. There is little you can do about the others except notice them at the preliminary meeting and suggest recording the Interview in another room.

If you deliberately record some of the above effects when practicing with your equipment, you will hear how irritating they sound when the tape is played back. You will then realize why you need to make an audible recording for interviews, mainly if you collect for an archive.

7. Getting Ready for the Oral History Interview

The difference between writing mediocre and a great narrative is planning, researching, and carefully stitching the memories and artifacts into a cohesive blend of resources to tell the story that will inspire generations to come. You are in charge of the Interview. The Interview will be as good as your preparation.

Should I try to conduct the oral history interview in one setting?

Yes and no. Most of the oral history interviews I did to write my mom’s narrative lasted between 45 and 90 minutes.

When I interviewed my dad, I lived in a different state. I asked my dad if I could set up a series of telephone interviews that I could record. I chose to break up the Interview into 10 60- to 90-minute sessions over six weeks. Each talk focused on a different time or topic of his life. At the end of each Interview, I outlined what I wanted to cover in the following Interview to give my dad time to ponder what stories he wanted to share. During our interviews, he shared many personal stories that I had never heard. We laughed, cried, and shared many precious and tender moments.

Do you ask all the oral history questions on your list?

I try to make sure that I give the person I am interviewing a list of the questions before the interview, so they have time to think.

Did I ask my parents and others the questions exactly as they listed as I had them? No. I used the questions to begin our discussion and explore the stories they wanted to share. I would encourage you to make these questions your own and personalize them with the person you are interviewing. When you are ready to conduct an interview, have the questions to get the information you desire. Family conversations can go in many directions. When possible, with the permission of the person you are interviewing, record the Interview on audio or video.

Some of the best things you find out will be unexpected. Once you get started with the Interview, you are likely to be told some things you had not previously thought about, so it is essential to give the person you are recording plenty of space to tell you what they think matters. But you should not let the interview drift: it is your job to guide it. For this, you need an overall plan. Group the topics you want to cover logically. I like the chronological structure, such as talking through life stages in order. I have provided examples of questions organized by life stages to preview and download from the companion website.

What kind of last-minute preparations do you do for an oral history interview?

It’s now the day before your Interview. Take time to do a quick check of the material, equipment, and artifacts you will take with you to make sure you’re all set. A simple checklist might help make sure you have all the equipment you need. Ensure that everything is in good working order. Check that you know how to operate all your equipment correctly and fresh batteries or an adaptor. Put together a folder containing maps, additional questions, a notepad, pencils or pens, and interview agreements (if you are using them).

Review the questions you have developed and choose which would be most appropriate for each person and whether there are other questions you should be asking specifically about the family line the person belonged to (such as grandparents, times in which they lived and so on). Then send each person a letter or email with the following information:

- Your name, address, email, and telephone number

- A brief overview of the project

- Questions you are going to ask

- A request to share artifacts

8. How to Conduct an Oral History Interview

Up to now, I have talked about getting ready for the oral history interview. In this section, I will introduce how to conduct an oral history interview.

Where should I set up an in-person oral history interview?

Choose a quiet place. Try to pick a room that is not near a busy road. If you can, switch off radios and televisions, which can sometimes make it difficult to hear what someone is saying.

What should I say in the oral history introduction?

Before you begin the interview, explain to the person that not all of the information provided will be used in the family history. They will have an opportunity to see and approve it before being published or distributed to other family members. Explain that you will ask questions to prompt ideas, but they do not have to answer all the questions. If a question seems too personal, have them let you know and then move on to the next question; if they tell you something they later regret, have them tell you and let them know that you will exclude it from being used.

How should I set up my equipment and resources for the oral history interview?

It’s essential to make sure your equipment is set upright. Plug the recorder into the wall or put in the batteries. Switch it on. Put a battery in the microphone if it needs one, and plug it into the microphone jack socket. Turn the microphone on. Always check the microphone battery before going to an interview, and carry spare batteries at all times. I always put in fresh batteries for an interview. All you need to make you a believer is one experience where the recorder becomes slow or stopped, and you have to do the Interview over.

If using a tape recorder, make sure you have the tape in the right way, and remember that nothing will be recorded on the clear plastic lead-in at the beginning, so wait until it has wound through before you start talking. Alternatively, wind the lead-in tape through manually so that you can begin to record as soon as you press the “record” button.

Check that you have your recording volume adjusted to the correct level and your playback volume turned off. If you don’t, you may experience a shrieking noise called feedback. Check to see that you have copies of your questions and other pertinent material for the Interview. Place the microphone on the table or clip it to the interviewee. Press the “record” button or the “record” and “play” buttons, depending on your machine.

Remember that if your recorder has only a playback volume control, this does not control the recording level. You can adjust only by moving the microphone or speaking more loudly or softly.

If you have only one clip-on microphone, place it on your interviewee and speak up yourself. While it is more important to record their voice than yours, it is useless if the listener to the tape cannot hear your questions, making sure that your voice is also audible.

For a unidirectional tabletop microphone, the optimum position is for the two of you to speak over it at a 90-degree angle.

How close should the microphone be?

Generally, the closer the microphone is, the better the results will be. If possible, use a clip-on microphone and put it about nine inches from the person’s mouth. With a hand-held microphone, place it as near as possible but not on the same surface as the recorder nor on a hard surface, which gives poor sound quality.

Is there anything I should record before I start the oral history interview?

Before every interview, I will make sure that I provide some type of identification for the Interview. Why? Because it may be months before I will return to the recording to digest what was said. The following is a typical identification:

Interview with [Say the name and spell it. ](say—Susan Longhurst, spelled S-U-S-A-N, New word L-O-N-G-H-U-R-S-T) 25 September 2021. Interviewed by Author Schreiber. [State purpose of Interview]

What are the best practices for conducting the oral history interview?

As I shared earlier in the Guide for Conducting Oral History Interviews for Writing Narratives, I have conducted hundreds of interviews. The following are just important best practices that I incorporate in my interview:

Be reassuring. You are their guest, and if they are elderly, you may be the first person they have spoken to for several days. They will be as nervous and apprehensive as you are, so it is essential to be cordial and patient.

The Interview is not a conversation. The point of the Interview is to get the narrator to tell her story. Limit your remarks to a few pleasantries to break the ice, then brief questions to guide her along. It is not necessary to give her the details of your great-grandmother’s trip in a covered wagon to get her to tell you about her grandfather’s trip to California. Just say, “I understand your grandfather came through the Panama Canal to California for his immigration in 1925. What did he tell you about the trip?”

One-on-one is best. Interviews usually work out better if there is no one present but you and the interviewee. Sometimes two or more interviewers can be successfully recorded, but usually, each one of them would have been better alone.

If you are using interview agreements, ask your interviewee to review and sign the agreement form before starting the Interview.

Begin the Interview with straightforward questions. Start with questions that are not controversial; save the delicate questions, if there are any until you have become better acquainted. An excellent place to begin is with the interviewee’s youth and background. For example, ask questions about the following topics:

- Date of birth and birthplace

- Names of parents

- Names of spouse and children

- Names of siblings

- Occupation, schooling

Ask questions that require a detailed answer. Early in the Interview, ask a question that requires a very detailed answer. After gaining the trust of the person you are interviewing, have some questions ready to signal to the person that you want details. Sometimes asking for a tour of a place, such as a house or place of work, helps gain much information. Ask follow-up questions with each “step” through the structure.

9. Use Open-Ended Questions in Oral History Interviews

Throughout the Interview, the questions that will give you the best information start with how, who, why, what, where, or when. Ask specific questions to get specific answers and open-ended ones to get longer, more detailed answers.

What type of questions should I ask in an oral history interview?

I am a firm believer in using open-ended questions. Open-ended questions allow people to tell stories they want to share. An example of open-ended questions are:

- What did you like to do when you were a little girl?

- What did you do on your first date?

- Where do you like to go for a vacation?

- Who is your favorite author, and why?

- What some of your favorite experiences with your mom and dad?

As you develop your questions, use plain words and avoid suggesting the answers. Rather than saying, “I suppose you must have had a poor and unhappy childhood,” instead ask, “Can you describe your childhood?”

You will need some questions that encourage precise answers, such as “Where did you move to next?” But you also need questions that are open, inviting descriptions, comments, and opinions. Some examples of open questions include “How did you feel about that?” “What sort of person was he?” “Can you describe the house you lived in?” and “Why did you decide to change jobs?”

There are some points to cover in every Interview, such as date and place of birth and what their parents and their main jobs were.

I will address how to interview in later sections of this guide.

Where can I find oral history questions that have already been developed?

I have written a comprehensive 27 articles, 108 category series entitled “ 7,500-plus Questions About Life to Ask People When Writing Narratives .” The prompts and questions are provided to help you look at life from as many angles as possible when writing narratives about yourself, your family, and others.

Can you provide examples of oral history interview questions/outlines?

I like to break up questions into either period of life or by topic. Below is a sample outline of the interview questions I have used.

Married Life and Children

- Children: • Names • Dates and places of birth • The health of the mother before and after • How father fared • Characteristics and differences • Talents and hobbies • Smart sayings and doings • Growing up (daily routine in-home) • Humorous episodes • Problems • Joys and sorrows • Accomplishments

- Child-rearing psychology • Role of yourself, spouse, children in the home

- Family traditions • Holidays • Birthdays • Graduation • Deer hunting • Funerals • Mother’s Day, Father’s Day • Weddings

- Family vacations

- Grandchildren • How many • Where they live • How their parents raised them • Things have done together • Trips to visit them and vice versa

Middle Age and Toward Retirement

- General life pattern changing: • More time on hand • Financial situation • Different and new interests • New friends and associates • New hobbies (genealogy, golf, reading, music, art, books)

- Health • In general • Operations • Allergies • Physical disabilities

- Decided preferences- favorite foods and so on

- Civic and political activities • Positions held • Services rendered • Politics • Political issues you were involved in • Memorable campaigns • Red Cross or other volunteer work • Church positions

- New business ventures: Memorable travels

- New and different homes

- Retirement and its impact • Financial • Family • Leisure time • Volunteer activities

Personal Philosophy about Life in General

- Your ideal-What personal trait do you admire most and why?

- Regrets-If you had your life to live over again, what would you do differently?

- One of the most important days of your life and why?

- The greatest joy and most enormous sorrow

- The biggest lesson in life you found to be true

- The most important lesson, message, or advice you’ve learned that you would like passed on for others to profit by

- One word on how to live successfully

- Your secret for living a long, healthy, happy, prosperous life

- Does the Lord answer prayers?

- How you would like to be remembered

- Funeral arrangements-music, speaker, ceremony, special instructions, headstone inscriptions, selection of burial clothes

- Unique words of counsel to: • Children • Grandchildren • Other families

10. How to Get the Best Answers in Oral History Interviews

In an oral history interview, there is an art to asking questions. It’s more than simply asking a question and then waiting for an answer. I found this out when I used the same set of questions to 5 siblings from the same family in 5 different interviews. For example, one of my questions was, “What was it like growing up in your hometown.” One sibling shared how wonderful it had been and all the activities and people who were part of their life. The other sibling, paused and with tears, shared how ugly the city had been for them because of the teasing, bullying, and living in the shadow of an older sibling.

What are some best practices for conducting oral history interviews?

As the interviewer, you are the one who is asking the questions. You are the one who asked for the Interview. I can assure you that not every Interview is going to be great. It is just the nature of interviewing. However, there a few best practices for conducting oral histories and asking questions that help you get the best answers possible. The following are some of the most important lessons I have learned.

Avoid simple yes-or-no questions. For example, ask, “What were your living conditions like?” rather than “Did you have cramped living conditions?” Ask open-ended questions if you want a description or comment: “What can you remember of the trip over to England?” or “Can you tell me more about what swimming in the Great Salt Lake was like?” Don’t ask more than one question at a time.

Get past stereotypes and generalizations. This is one of the most challenging aspects of interviewing people. As well as a mere descriptive retelling of events, try to explore motives and feelings with questions like “Why?” and “How did you feel?”