The Message of Cities

[ Tim Lee ] A good essay by Paul Graham on cities and ambition:

Great cities attract ambitious people. You can sense it when you walk around one. In a hundred subtle ways, the city sends you a message: you could do more; you should try harder. The surprising thing is how different these messages can be. New York tells you, above all: you should make more money. There are other messages too, of course. You should be hipper. You should be better looking. But the clearest message is that you should be richer. What I like about Boston (or rather Cambridge) is that the message there is: you should be smarter. You really should get around to reading all those books you've been meaning to. When you ask what message a city sends, you sometimes get surprising answers. As much as they respect brains in Silicon Valley, the message the Valley sends is: you should be more powerful.

Here in St. Louis, the message is "you should have met the right people in school." The cliche here is that the first thing St. Louisans ask when they meet each other is "what high school did you go to?" The answer tells them about the speaker's social class and often his religious background. Also, if you want to be successful in Missouri you don't don't go to the highly-ranked Washington University, but to the University of Missouri in Columbia, which is where the kids of other rich and powerful Missourians go to school. Needless to say, moving to St. Louis in your 20s isn't a brilliant career move:

No matter how determined you are, it's hard not to be influenced by the people around you. It's not so much that you do whatever a city expects of you, but that you get discouraged when no one around you cares about the same things you do.

When I lived in DC and I told people I worked at a think tank, virtually everyone knew what that was and many were interested to know which one and what I did there. When I go to a party in St. Louis, the people I meet not only don't know what a think tank is, but a lot of them don't know what public policy is. I've taken to just telling people I'm a writer, which is something most people have heard of. Here's Graham's take on DC, which he admits he hasn't lived in long enough to be sure of:

In DC the message seems to be that the most important thing is who you know. You want to be an insider. In practice this seems to work much as in LA. There's an A List and you want to be on it or close to those who are. The only difference is how the A List is selected. And even that is not that different.

- Environments

Cities and Ambition: Paul Graham

A new essay by Graham, Cities and Ambition , plays right into my own proclivity to compare and contrast life in the major cities that I have known in my life. I grew up in the Bay Area—San Francisco, Berkeley and Silicon Valley—then spent the rest of my adult life in New York City and Boston/Cambridge. As I have continued to visit my former haunts on a regular basis, I came up with a few favorite delineators to compare the quality of life in each of these cities. (One that I used as an indicator of a city’s quality and that Graham also mentions is the eavesdropping factor.) But Graham’s taxonomy is so much more extensive and better than anything I’ve thought or read. He’s brilliant.

Because he is a Cantabridgian his assessment may seemed skewed to favor the home team. It probably is. But I’ll take a stand and say I agree with him wholeheartedly. All points of view are invited to comment. If you feel you need to make a case for Salt Lake City or Pittsburgh, please be my guest.

Note: This essay is bloody long, but I’m including the entire text because it is so interesting. If you aren’t in the mood to spend the time plowing through the whole thing, you can still find enjoyment in just the first few paragraphs. Hard core fans can ride it all the way to the end.

Cities and Ambition By Paul Graham

Great cities attract ambitious people. You can sense it when you walk around one. In a hundred subtle ways, the city sends you a message: you could do more; you should try harder.

The surprising thing is how different these messages can be. New York tells you, above all: you should make more money. There are other messages too, of course. You should be hipper. You should be better looking. But the clearest message is that you should be richer.

What I like about Boston (or rather Cambridge) is that the message there is: you should be smarter. You really should get around to reading all those books you’ve been meaning to.

When you ask what message a city sends, you sometimes get surprising answers. As much as they respect brains in Silicon Valley, the message the Valley sends is: you should be more powerful.

That’s not quite the same message New York sends. Power matters in New York too of course, but New York is pretty impressed by a billion dollars even if you merely inherited it. In Silicon Valley no one would care except a few real estate agents. What matters in Silicon Valley is how much effect you have on the world. The reason people there care about Larry and Sergey is not their wealth but the fact that they control Google, which affects practically everyone.

How much does it matter what message a city sends? Empirically, the answer seems to be: a lot. You might think that if you had enough strength of mind to do great things, you’d be able to transcend your environment. Where you live should make at most a couple percent difference. But if you look at the historical evidence, it seems to matter more than that. Most people who did great things were clumped together in a few places where that sort of thing was done at the time.

You can see how powerful cities are from something I wrote about earlier: the case of the Milanese Leonardo. Practically every fifteenth century Italian painter you’ve heard of was from Florence, even though Milan was just as big. People in Florence weren’t genetically different, so you have to assume there was someone born in Milan with as much natural ability as Leonardo. What happened to him?

If even someone with the same natural ability as Leonardo couldn’t beat the force of environment, do you suppose you can?

I don’t. I’m fairly stubborn, but I wouldn’t try to fight this force. I’d rather use it. So I’ve thought a lot about where to live.

I’d always imagined Berkeley would be the ideal place—that it would basically be Cambridge with good weather. But when I finally tried living there a couple years ago, it turned out not to be. The message Berkeley sends is: you should live better. Life in Berkeley is very civilized. It’s probably the place in America where someone from Northern Europe would feel most at home. But it’s not humming with ambition.

In retrospect it shouldn’t have been surprising that a place so pleasant would attract people interested above all in quality of life. Cambridge with good weather, it turns out, is not Cambridge. The people you find in Cambridge are not there by accident. You have to make sacrifices to live there. It’s expensive and somewhat grubby, and the weather’s often bad. So the kind of people you find in Cambridge are the kind of people who want to live where the smartest people are, even if that means living in an expensive, grubby place with bad weather.

As of this writing, Cambridge seems to be the intellectual capital of the world. I realize that seems a preposterous claim. What makes it true is that it’s more preposterous to claim about anywhere else. American universities currently seem to be the best, judging from the flow of ambitious students. And what US city has a stronger claim? New York? A fair number of smart people, but diluted by a much larger number of neanderthals in suits. The Bay Area has a lot of smart people too, but again, diluted; there are two great universities, but they’re far apart. Harvard and MIT are practically adjacent by West Coast standards, and they’re surrounded by about 20 other colleges and universities. [1]

Cambridge as a result feels like a town whose main industry is ideas, while New York’s is finance and Silicon Valley’s is startups.

When you talk about cities in the sense we are, what you’re really talking about is collections of people. For a long time cities were the only large collections of people, so you could use the two ideas interchangeably. But we can see how much things are changing from the examples I’ve mentioned. New York is a classic great city. But Cambridge is just part of a city, and Silicon Valley is not even that. (San Jose is not, as it sometimes claims, the capital of Silicon Valley. It’s just 178 square miles at one end of it.)

Maybe the Internet will change things further. Maybe one day the most important community you belong to will be a virtual one, and it won’t matter where you live physically. But I wouldn’t bet on it. The physical world is very high bandwidth, and some of the ways cities send you messages are quite subtle.

One of the exhilarating things about coming back to Cambridge every spring is walking through the streets at dusk, when you can see into the houses. When you walk through Palo Alto in the evening, you see nothing but the blue glow of TVs. In Cambridge you see shelves full of promising-looking books. Palo Alto was probably much like Cambridge in 1960, but you’d never guess now that there was a university nearby. Now it’s just one of the richer neighborhoods in Silicon Valley. [2]

A city speaks to you mostly by accident—in things you see through windows, in conversations you overhear. It’s not something you have to seek out, but something you can’t turn off. One of the occupational hazards of living in Cambridge is overhearing the conversations of people who use interrogative intonation in declarative sentences. But on average I’ll take Cambridge conversations over New York or Silicon Valley ones.

A friend who moved to Silicon Valley in the late 90s said the worst thing about living there was the low quality of the eavesdropping. At the time I thought she was being deliberately eccentric. Sure, it can be interesting to eavesdrop on people, but is good quality eavesdropping so important that it would affect where you chose to live? Now I understand what she meant. The conversations you overhear tell you what sort of people you’re among.

No matter how determined you are, it’s hard not to be influenced by the people around you. It’s not so much that you do whatever a city expects of you, but that you get discouraged when no one around you cares about the same things you do.

There’s an imbalance between encouragement and discouragement like that between gaining and losing money. Most people overvalue negative amounts of money: they’ll work much harder to avoid losing a dollar than to gain one. Similarly, though there are plenty of people strong enough to resist doing something just because that’s what one is supposed to do where they happen to be, there are few strong enough to keep working on something no one around them cares about.

Because ambitions are to some extent incompatible and admiration is a zero-sum game, each city tends to focus on one type of ambition. The reason Cambridge is the intellectual capital is not just that there’s a concentration of smart people there, but that there’s nothing else people there care about more. Professors in New York and the Bay area are second class citizens—till they start hedge funds or startups respectively.

This suggests an answer to a question people in New York have wondered about since the Bubble: whether New York could grow into a startup hub to rival Silicon Valley. One reason that’s unlikely is that someone starting a startup in New York would feel like a second class citizen. [3] There’s already something else people in New York admire more.

In the long term, that could be a bad thing for New York. The power of an important new technology does eventually convert to money. So by caring more about money and less about power than Silicon Valley, New York is recognizing the same thing, but slower. [4] And in fact it has been losing to Silicon Valley at its own game: the ratio of New York to California residents in the Forbes 400 has decreased from 1.45 when the list was first published in 1982 to .83 in 2007.

Not all cities send a message. Only those that are centers for some type of ambition do. And it can be hard to tell exactly what message a city sends without living there. I understand the messages of New York, Cambridge, and Silicon Valley because I’ve lived for several years in each of them. DC and LA seem to send messages too, but I haven’t spent long enough in either to say for sure what they are.

The big thing in LA seems to be fame. There’s an A List of people who are most in demand right now, and what’s most admired is to be on it, or friends with those who are. Beneath that the message is much like New York’s, though perhaps with more emphasis on physical attractiveness.

In DC the message seems to be that the most important thing is who you know. You want to be an insider. In practice this seems to work much as in LA. There’s an A List and you want to be on it or close to those who are. The only difference is how the A List is selected. And even that is not that different.

At the moment, San Francisco’s message seems to be the same as Berkeley’s: you should live better. But this will change if enough startups choose SF over the Valley. During the Bubble that was a predictor of failure—a self-indulgent choice, like buying expensive office furniture. Even now I’m suspicious when startups choose SF. But if enough good ones do, it stops being a self-indulgent choice, because the center of gravity of Silicon Valley will shift there.

I haven’t found anything like Cambridge for intellectual ambition. Oxford and Cambridge (England) feel like Ithaca or Hanover: the message is there, but not as strong.

Paris was once a great intellectual center. If you went there in 1300, it might have sent the message Cambridge does now. But I tried living there for a bit last year, and the ambitions of the inhabitants are not intellectual ones. The message Paris sends now is: do things with style. I liked that, actually. Paris is the only city I’ve lived in where people genuinely cared about art. In America only a few rich people buy original art, and even the more sophisticated ones rarely get past judging it by the brand name of the artist. But looking through windows at dusk in Paris you can see that people there actually care what paintings look like. Visually, Paris has the best eavesdropping I know. [5]

There’s one more message I’ve heard from cities: in London you can still (barely) hear the message that one should be more aristocratic. If you listen for it you can also hear it in Paris, New York, and Boston. But this message is everywhere very faint. It would have been strong 100 years ago, but now I probably wouldn’t have picked it up at all if I hadn’t deliberately tuned in to that wavelength to see if there was any signal left.

So far the complete list of messages I’ve picked up from cities is: wealth, style, hipness, physical attractiveness, fame, political power, economic power, intelligence, social class, and quality of life.

My immediate reaction to this list is that it makes me slightly queasy. I’d always considered ambition a good thing, but I realize now that was because I’d always implicitly understood it to mean ambition in the areas I cared about. When you list everything ambitious people are ambitious about, it’s not so pretty.

On closer examination I see a couple things on the list that are surprising in the light of history. For example, physical attractiveness wouldn’t have been there 100 years ago (though it might have been 2400 years ago). It has always mattered for women, but in the late twentieth century it seems to have started to matter for men as well. I’m not sure why—probably some combination of the increasing power of women, the increasing influence of actors as models, and the fact that so many people work in offices now: you can’t show off by wearing clothes too fancy to wear in a factory, so you have to show off with your body instead.

Hipness is another thing you wouldn’t have seen on the list 100 years ago. Or wouldn’t you? What it means is to know what’s what. So maybe it has simply replaced the component of social class that consisted of being “au fait.” That could explain why hipness seems particularly admired in London: it’s version 2 of the traditional English delight in obscure codes that only insiders understand.

Economic power would have been on the list 100 years ago, but what we mean by it is changing. It used to mean the control of vast human and material resources. But increasingly it means the ability to direct the course of technology, and some of the people in a position to do that are not even rich—leaders of important open source projects, for example. The Captains of Industry of times past had laboratories full of clever people cooking up new technologies for them. The new breed are themselves those people.

As this force gets more attention, another is dropping off the list: social class. I think the two changes are related. Economic power, wealth, and social class are just names for the same thing at different stages in its life: economic power converts to wealth, and wealth to social class. So the focus of admiration is simply shifting upstream.

Does anyone who wants to do great work have to live in a great city? No; all great cities inspire some sort of ambition, but they aren’t the only places that do. For some kinds of work, all you need is a handful of talented colleagues.

What cities provide is an audience, and a funnel for peers. These aren’t so critical in something like math or physics, where no audience matters except your peers, and judging ability is sufficiently straightforward that hiring and admissions committees can do it reliably. In a field like math or physics all you need is a department with the right colleagues in it. It could be anywhere—in Los Alamos, New Mexico, for example.

It’s in fields like the arts or writing or technology that the larger environment matters. In these the best practitioners aren’t conveniently collected in a few top university departments and research labs—partly because talent is harder to judge, and partly because people pay for these things, so one doesn’t need to rely on teaching or research funding to support oneself. It’s in these more chaotic fields that it helps most to be in a great city: you need the encouragement of feeling that people around you care about the kind of work you do, and since you have to find peers for yourself, you need the much larger intake mechanism of a great city.

You don’t have to live in a great city your whole life to benefit from it. The critical years seem to be the early and middle ones of your career. Clearly you don’t have to grow up in a great city. Nor does it seem to matter if you go to college in one. To most college students a world of a few thousand people seems big enough. Plus in college you don’t yet have to face the hardest kind of work—discovering new problems to solve.

It’s when you move on to the next and much harder step that it helps most to be in a place where you can find peers and encouragement. You seem to be able to leave, if you want, once you’ve found both. The Impressionists show the typical pattern: they were born all over France (Pissarro was born in the Carribbean) and died all over France, but what defined them were the years they spent together in Paris.

Unless you’re sure what you want to do and where the leading center for it is, your best bet is probably to try living in several places when you’re young. You can never tell what message a city sends till you live there, or even whether it still sends one. Often your information will be wrong: I tried living in Florence when I was 25, thinking it would be an art center, but it turned out I was 450 years too late.

Even when a city is still a live center of ambition, you won’t know for sure whether its message will resonate with you till you hear it. When I moved to New York, I was very excited at first. It’s an exciting place. So it took me quite a while to realize I just wasn’t like the people there. I kept searching for the Cambridge of New York. It turned out it was way, way uptown: an hour uptown by air.

Some people know at 16 what sort of work they’re going to do, but in most ambitious kids, ambition seems to precede anything specific to be ambitious about. They know they want to do something great. They just haven’t decided yet whether they’re going to be a rock star or a brain surgeon. There’s nothing wrong with that. But it means if you have this most common type of ambition, you’ll probably have to figure out where to live by trial and error. You’ll probably have to find the city where you feel at home to know what sort of ambition you have.

[1] This is one of the advantages of not having the universities in your country controlled by the government. When governments decide how to allocate resources, political deal-making causes things to be spread out geographically. No central goverment would put its two best universities in the same town, unless it was the capital (which would cause other problems). But scholars seem to like to cluster together as much as people in any other field, and when given the freedom to they derive the same advantages from it.

[2] There are still a few old professors in Palo Alto, but one by one they die and their houses are transformed by developers into McMansions and sold to VPs of Bus Dev.

[3] How many times have you read about startup founders who continued to live inexpensively as their companies took off? Who continued to dress in jeans and t-shirts, to drive the old car they had in grad school, and so on? If you did that in New York, people would treat you like shit. If you walk into a fancy restaurant in San Francisco wearing a jeans and a t-shirt, they’re nice to you; who knows who you might be? Not in New York.

One sign of a city’s potential as a technology center is the number of restaurants that still require jackets for men. According to Zagat’s there are none in San Francisco, LA, Boston, or Seattle, 4 in DC, 6 in Chicago, 8 in London, 13 in New York, and 20 in Paris.

(Zagat’s lists the Ritz Carlton Dining Room in SF as requiring jackets but I couldn’t believe it, so I called to check and in fact they don’t. Apparently there’s only one restaurant left on the entire West Coast that still requires jackets: The French Laundry in Napa Valley.)

[4] Ideas are one step upstream from economic power, so it’s conceivable that intellectual centers like Cambridge will one day have an edge over Silicon Valley like the one the Valley has over New York.

This seems unlikely at the moment; if anything Boston is falling further and further behind. The only reason I even mention the possibility is that the path from ideas to startups has recently been getting smoother. It’s a lot easier now for a couple of hackers with no business experience to start a startup than it was 10 years ago. If you extrapolate another 20 years, maybe the balance of power will start to shift back. I wouldn’t bet on it, but I wouldn’t bet against it either.

[5] If Paris is where people care most about art, why is New York the center of gravity of the art business? Because in the twentieth century, art as brand split apart from art as stuff. New York is where the richest buyers are, but all they demand from art is brand, and since you can base brand on anything with a sufficiently identifiable style, you may as well use the local stuff.

Share this:

6 replies to “cities and ambition: paul graham”.

Wow, I live in Cambridge and I never heard of this man. Fascinating — thanks! I need to be on a better party list perhaps. Or just, on a party list.

I actually did read the whole thing, even though in a way I would hate to be quizzed on. The reflections of smart people in various disciplines — as opposed to urban planners, who may be smart but are also thinking thoughts they’re supposed to think — on what creates quality of life in a city would make a very good book. Deborah?

Writing in _The City in History_ (1961), Lewis Mumford produced the largest, fairest, simplest and most inclusive vision that I have ever seen of how the quality of life in a city should be judged. It would depend, he said, on how many places there were in that city to sit down without having to buy anything. Growing up in a large Texas city in the 50’s and 60’s, I did not, when I first read those words in 1968, know what he meant. Seating yourself downtown in broad daylight was something vagrants did, and there was no one to sell you anything anyhow if you pulled up the sidewalk. Several years later, I started spending lots of time in European cities, and saw that Mumford had had a penetrating insight into why some cities were for people and others were more like massive cubic mileages of pure hospital, incorporating patient care without, really, prioritizing it, and running only to be running.

What a powerful observation of too many of our American cities–“more like massive cubic mileages of pure hospital, incorporating patient care without, really, prioritizing it, and running only to be running.” Brilliant, and so painfully accurate.

I read Mumford so long ago. He and Jane Jacobs both came out with books around the same time (hers was The Death and Life of Great American Cities ) and I remember being very influenced by both of them. Maybe it is time to revisit both those writers.

Thanks for reading Graham all the way through. We’ll have to talk about it when we do some “in the flesh” connecting soon…

Very interesting, Deborah. I can see what he means. Toledo, in Spain, was the intellectual capital of Europe in the eleventh century because of all the different religions coexisting there at the time. All those translations of the Koran, the Torah, and the Bible. It makes sense.

I’ve spent some time in Cambridge and the Boston area, taught school there for a year. There’s a lot of pressure to go to the right private school, the right university. It’s funny, though, that in the metro area of Boston, people with a native Cambridge accent get made fun of. They’re kind of considered to be townies. Wonder what Graham would say about that.

what I liked about his essay was his take on each city, what vibe he thought each city gave off. I live in metro Atlanta. It’s so big, you’d really have to divide the city into zones, each one emanating its own aura or personality.

Where I live people say ” you should be more Christian, live in a bigger house, have a better car, and look better.” Very superficial. Very neo-con, literaal-minded. I do rise above that vibe, but I’m always daydreaming about moving to another section of the city, or even to a new location. I’m partial to artistic settings.

Great post. I’m going to start listening more to what cities tell me.

C, Thanks for your insights. I know the vibe you talk of–the “more Christian/bigger house/better car/look better” ethos–which drains a lot of creativity out of a system and a population.

And the two culture division in Boston/Cambridge between townies and the Ivy leaguers (touched on in the movie Good Will Hunting) is real, absolutely. Because Graham is a technologist I think his lens is skewed to a particular segment of the population.

Thanks for your thoughts on this.

Hmmm…yes lengthy but worthy. I struggled with this because I have always lived in the suburbs. As a teenager we would always go to Squirrel Hill to “Heads Together” to browse vinyls and peruse paraphernalia. To Shadyside to get cheesecake. There was nothing happening in the blue collar mentality of the burbs. My parents were escaping the grubby city, for something better or so it seemed. I came back to the city, when my son enrolled at CMU. I renewed my acquaintance with the city that I traversed as an adventuress.

But Pittsburgh has this “tunnel” mentality. No, literally. The tunnels are a physical barrier that has come to define a mental barrier to going into the city. If you do not live within the confines of the city you are doomed to:

“There’s an imbalance between encouragement and discouragement like that between gaining and losing money. Most people overvalue negative amounts of money: they’ll work much harder to avoid losing a dollar than to gain one. Similarly, though there are plenty of people strong enough to resist doing something just because that’s what one is supposed to do where they happen to be, there are few strong enough to keep working on something no one around them cares about.”

D, thank you for the Pittsburgh debrief…having spent so much time there while our kids were both at CMU, I know what you mean about the tunnel mentality. Much more could be said about the life of every city than Graham deals with here, so perhaps that is another conversation in the future.

Comments are closed.

André Chaperon

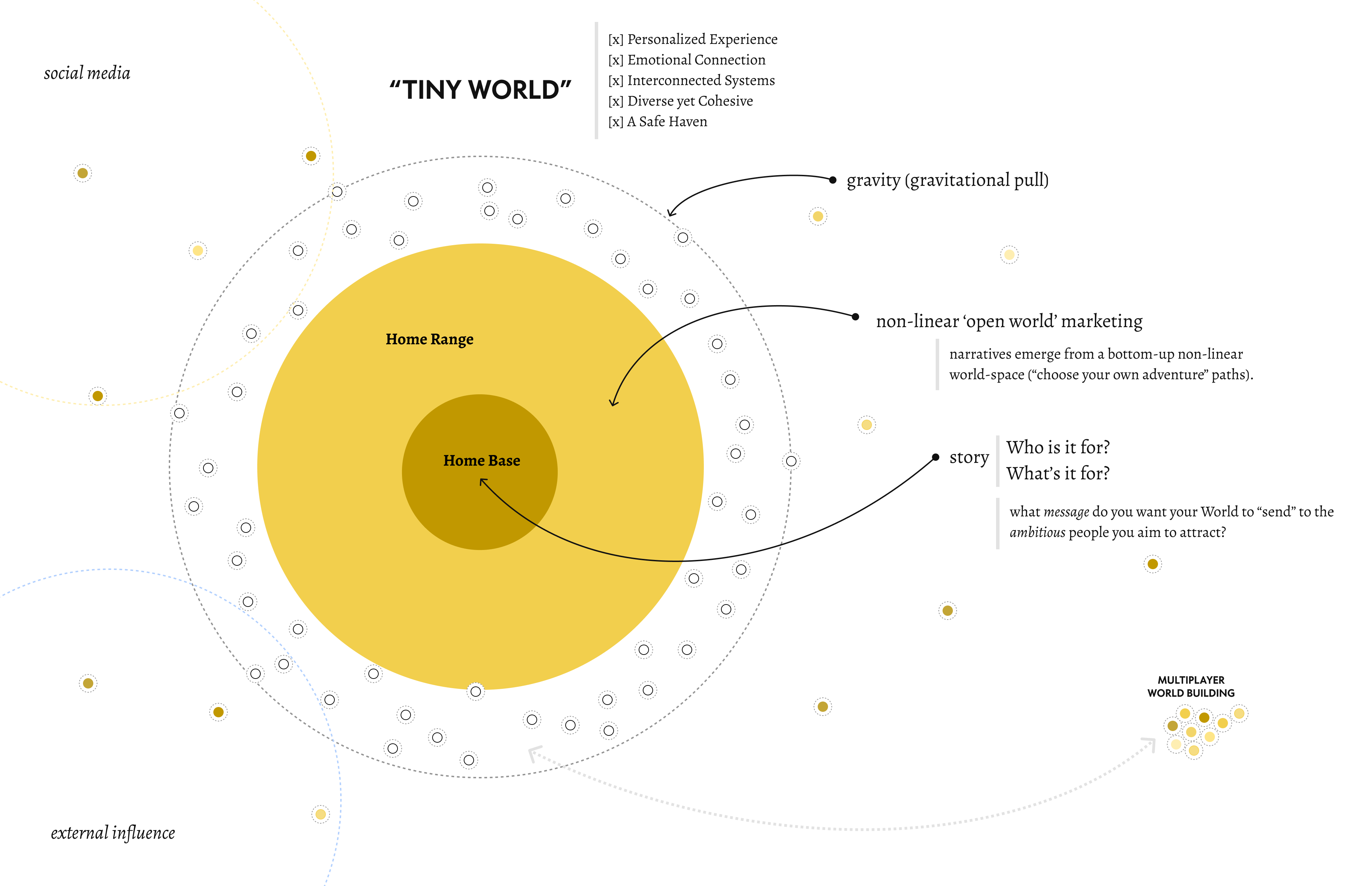

I write about how Sovereign Creators can build a Digital World around their core idea. This new approach shifts focus from chasing audiences to attracting them, thus building trust and earning attention. Welcome to the art of building a Tiny Digital World .

Cities and Ambition

Have you ever been to a city that gives off a subtle “message” of either resonance or dissonance?

Dissonance is sometimes easier to sense or feel. The first time I visited Sofia, Bulgaria, was in the winter of 2003, and I liked nothing about the city.

It was cold, gray, and ugly — trying unsuccessfully to shed its past communist rule. The buildings still bore the stark, utilitarian architecture of the Soviet era, their concrete facades chipped and weather-worn. The streets were lined with dilapidated infrastructure, strewn with potholes you could lose a car in, and the public spaces lacked vibrancy and warmth.

I couldn’t wait to leave the city. It was overwhelmingly depressing. The “message” Sofia sent me was subtle but unmistakable: a sense of dissonance.

Not all cities radiate a message. Most don’t. Most are mute.

In May 2008, Paul Graham , the co-founder of influential startup accelerator firm Y Combinator, published an essay, Cities and Ambition . (It’s an excellent read.)

I don’t recall when I first read it, but it left an indelible mark.

I reread it recently (a few times), and it’s provided me with language I didn’t have before in describing the “messages” some cities subtly broadcast to their inhabitants.

Paul Graham’s framing is mapped to the idea of ‘ambition.’ And I like that because it ties directly to why a particular collection of people are attracted to a city.

Because the message the city sends to these people is the same.

“ Great cities attract ambitious people . You can sense it when you walk around one. In a hundred subtle ways, the city sends you a message: you could do more; you should try harder.” “The surprising thing is how different these messages can be. New York tells you, above all: you should make more money. There are other messages too, of course. You should be hipper. You should be better looking. But the clearest message is that you should be richer.” “When you ask what message a city sends, you sometimes get surprising answers. As much as they respect brains in Silicon Valley, the message the Valley sends is: you should be more powerful.” “That’s not quite the same message New York sends. Power matters in New York too of course, but New York is pretty impressed by a billion dollars even if you merely inherited it. In Silicon Valley no one would care except a few real estate agents. What matters in Silicon Valley is how much effect you have on the world. The reason people there care about Larry and Sergey is not their wealth but the fact that they control Google, which affects practically everyone.” Excerpts from Cities and Ambition by Paul Graham (2008)

When you talk about cities in this context, Paul Graham makes an interesting observation that what you’re really talking about is collections of people .

Cities implicitly “curate” a concentration of like-minded people.

As Paul Graham argues in the essay, Cambridge (Massachusetts) feels like a town whose primary industry is ideas , while New York’s is finance and Silicon Valley’s is startups . The message Paris sends now is: do things with style .

Cities provide an audience and a funnel for peers because it’s hard not to be influenced by the people around you climbing the same mountain.

Where opportunities not available elsewhere can take hold, and serendipity can thrive.

But when a city doesn’t send a message, it doesn’t attract (ambitious) people of a particular calling. And it’s discouraging when no one around you cares about the same things you do.

Sofia had that effect on me twenty years ago.

A city speaks to you mostly by accident — in things you see through windows, in conversations you overhear. It’s not something you have to seek out, but something you can’t turn off.

Bath in Somerset, UK, is one of those cities.

I can’t “turn off” the message I get from the city, a feeling that instantly resonated with me the first time I visited (and every time since).

I instantly fell in love.

I’ve since visited a handful of times, and each time the city sends me the same message: you should be an artist; a writer; a creative hell-raiser doing shit differently, a rebel, a misfit, one of the crazy ones .

The city seems to care for people like this, a subtle embrace, an insider’s nod invisible to everyone who doesn’t identify as a creative soul seeking a collection of their “weird” people.

… but, to me, the subtleties continue — the message from the old medieval city also says: you should love good food with local ingredients thoughtfully prepared and overvalue wonderful entertainment.

There’s a young vibe, too, thanks to the University of Bath (named University of the Year in 2023) contributing to the message.

I was there last month and had lunch with my dear friend and author, Joanna Penn .

I arrived a little early (I’m always early), so I popped into The Huntsman , a pub in stunning Georgian surroundings, and nursed an excellent locally brewed ale.

There was no desire to browse on my mobile. Not in this beautiful city, teaming with people. So I people-watched . Enjoying the atmosphere, the hum of conversations, random laughter, the clinking of glasses for celebrations unknown. The warm, rustic Georgian interior was filled with a mix of locals and tourists (two Spanish sat to my right), all contributing to the vibrant energy of the place. The aroma of hearty pub food wafted through the air, mingling with the hoppy scent of the ale in my hand.

I met Jo thirty minutes later at the OAK Restaurant , a two-minute walk just around the corner. She was already there, a white wine in front of her. She picked the spot, being the local, so I knew it would be wonderful.

But damn, was it “cozy” (aka small!) — no seats empty.

I’ve never tasted hummus, zhoug, and chickpeas like this before. Stunning! I’m so returning to this restaurant next time I visit Bath.

On the OAK website , it says:

As a grocer we specialise in organic, biodynamic and low intervention ingredients. At the heart of OAK is the idea that great food puts the soil first. As growers, grocers and cooks we want to sell produce and serve food that is simple and thoughtful, to find vegetables that not only look and taste great, but also come from land that has been farmed properly, without chemicals or over cultivation.

The city spoke to me over and over, like a faint signal in the air: you should be an artist, a writer, a creative hell-raiser. You should love good food with local ingredients thoughtfully prepared and overvalue wonderful entertainment.

Great cities attract ambitious people.

Walking around a great city, you can sense the ambition in the air. People are striving to achieve great things, and they are constantly surrounded by others who are doing the same.

People cut from the same weird cloth.

When surrounded by ambitious people working towards similar goals, staying motivated, focused, and energized can be easier, opening up opportunities not available elsewhere in such a concentration.

While Paul Graham’s essay focuses on (living in) physical cities, there is a noticeable analog to (some) online businesses.

As sovereign creators and Tiny World Builders , we architect non-linear Worlds for our audiences to inhabit, attracting ambitious people into our fold — the weird people we serve; the hell-raisers.

Like a great city, the “message” our Tiny Worlds says attracts a specific collection of ambitious people with common needs, wants, or aspirations.

For the sovereign creators I’m serving, the “city” I’m building here says:

- you can do better;

- the quality of your audience matters;

- delight the weird;

- the sacred act of earning trust and attention and fostering lasting relationships is worth the long-term effort;

- ‘open-world’ marketing is a container for this to happen, a canvas from which you build your Tiny World.

This Tiny World I’m building for you to inhabit is still small but will expand over time — the “message” it sends you will become more distinct and clear.

I’ll leave you with a question: What ‘message’ do you want your “city” to send to the ambitious citizens you aim to attract?

Because make no mistake, like it or not, your website, your place of business — it’s putting out a message . Subtly, implicitly, or “by accident,” it’s there, talking to your people.

The message is an emergent property — a felt voice — from all the “parts” of your business interacting in ways that are not always obvious or predictable.

But it’s there. Talking. Attracting.

(And repelling.)

©2003-2024 • Handcrafted from the Rock of Gibraltar by André Chaperon • Contact

Proudly built with GeneratePress + GenerateBlocks on WordPress • Hosted by Rocket (the world's fastest WordPress hosting) • Email is sent using the brilliant ConvertKit (full review here ) • Articles

- Liberty Fund

- Adam Smith Works

- Law & Liberty

- Browse by Author

- Browse by Topic

- Browse by Date

- Search EconLog

- Latest Episodes

- Browse by Guest

- Browse by Category

- Browse Extras

- Search EconTalk

- Latest Articles

- Liberty Classics

- Search Articles

- Books by Date

- Books by Author

- Search Books

- Browse by Title

- Biographies

- Search Encyclopedia

- #ECONLIBREADS

- College Topics

- High School Topics

- Subscribe to QuickPicks

- Search Guides

- Search Videos

- Library of Law & Liberty

- Home /

ECONLOG POST

May 28 2008

Paul Graham on Cities

Arnold kling .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-avatar img { width: 80px important; height: 80px important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-avatar img { border-radius: 50% important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a { background-color: #655997 important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a { color: #ffffff important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a:hover { color: #ffffff important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-recent-posts-title { border-bottom-style: dotted important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-recent-posts-item { text-align: left important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { border-style: none important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { color: #3c434a important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { border-radius: px important; } .pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline ul.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-ul { display: flex; } .pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline ul.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-ul li { margin-right: 10px }.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.pp-multiple-authors-wrapper.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-post-id-69046.box-instance-id-1.ppma_boxes_69046 ul li > div:nth-child(1) {flex: 1 important;}.

By Arnold Kling, May 28 2008

He writes ,

In DC the message seems to be that the most important thing is who you know. You want to be an insider. In practice this seems to work much as in LA. There’s an A List and you want to be on it or close to those who are. The only difference is how the A List is selected. And even that is not that different.

Exactly. LA and DC are both name-dropper cities. In LA, the names to drop are those of leaders in the movie or TV business. In DC, the names to drop are those of key figures in Congress or the Administration.

Read the whole thing. Pointer from Megan’s guest-blogger (Tim Lee), who offers his own insight.

The cliche here is that the first thing St. Louisans ask when they meet each other is “what high school did you go to?” The answer tells them about the speaker’s social class and often his religious background.

Again, having grown up in St. Louis, I would say that this is spot on. The St. Louis elite is a remarkably closed, self-satisified set. The Merle Kling model of politics seems to apply particularly well in St. Louis. The game is for insiders there.

READER COMMENTS

- READ COMMENT POLICY

guy in the veal calf office

May 28 2008 at 6:56pm.

I don’t understand the point of all this. What is the utility of knowing A listers? I can’t name a single thing it would improve in my life– even film premiers suck; I’d rather pay and do it simply.

May 28 2008 at 9:04pm

I had always thought that it was about “who you know” and figured that I would never make it because I am terrible at that sort of thing, and don’t know anybody (or didn’t). Plus I don’t have the usual credentials. But so far, I have gotten all my jobs, and now including my job at a prestigious think tank, without knowing anybody. I still don’t name drop because most names fall from my brain before they reach my tongue.

It turns out that other stuff matters, at least in DC.

May 29 2008 at 6:36am

“DC is LA for ugly people.”

I do not know the source, first saw it on Wonkette maybe 3 years ago? It is now ubiquitous in the blogosphere.

David Tufte

May 29 2008 at 11:50am.

New Orleans is similar to St. Louis, although Don Boudreaux would be a better source on this than me.

Comments are closed.

RECENT POST

The ministry of silly hospitals, bryan caplan .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-avatar img { width: 80px important; height: 80px important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-avatar img { border-radius: 50% important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a { background-color: #655997 important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a { color: #ffffff important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-meta a:hover { color: #ffffff important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-recent-posts-title { border-bottom-style: dotted important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-author-boxes-recent-posts-item { text-align: left important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { border-style: none important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { color: #3c434a important; } .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.box-post-id-69046.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-instance-id-1 .pp-multiple-authors-boxes-li { border-radius: px important; } .pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline ul.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-ul { display: flex; } .pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline ul.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-ul li { margin-right: 10px }.pp-multiple-authors-boxes-wrapper.pp-multiple-authors-wrapper.pp-multiple-authors-layout-inline.multiple-authors-target-shortcode.box-post-id-69046.box-instance-id-1.ppma_boxes_69046 ul li > div:nth-child(1) {flex: 1 important;}.

Check out these true Monty Python-esque dialogues between a series of hospitals and a guy who wants an affordable colonoscopy. First dialogue:Conversation with Stanford Hospital: Me: My wife needs a colonoscopy: Could you give me a price on it? Stanford Hospital: (businesslike tone) Twenty five hundred to ...

Are Charities Like Startups?

From Another Paul Graham essay: If you start from successful startups, you find they often behaved like nonprofits. And if you start from ideas for nonprofits, you find they'd often make good startups. In Under the Radar, where I argued in favor of bootstrapping a business, I wrote Fundraising is not for businesses....

He writes, In DC the message seems to be that the most important thing is who you know. You want to be an insider. In practice this seems to work much as in LA. There's an A List and you want to be on it or close to those who are. The only difference is how the A List is selected. And even that is not that different. ...

Erik Trautman

“everything you can imagine is real.” -- pablo picasso, paul graham on "cities and ambition".

I don't intend to use this as a platform for just relinking to other blogs but, given the context of my recent posts, in this case it seems rather appropriate. In an archived essay, Paul Graham brings up some very insightful things about the characters of ambitious cities that I couldn't write any better myself. In particular, he talks about the subtler messages that cities send and why that is so important for choosing the right one. Check it out: http://paulgraham.com/cities.html

Receive new posts directly to your inbox

Recent posts.

A response to Seth Godin on NFTs

Give NFTs a Chance

UX Equilibrium

Why I'm Interested in Blockchain

Talking Your Book

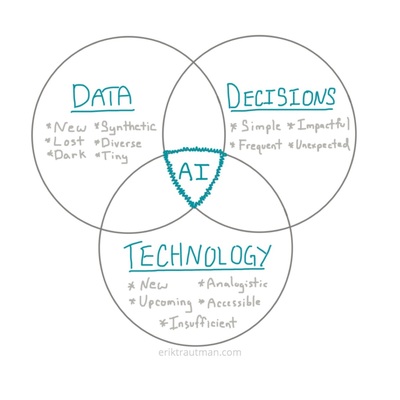

A Practical Framework for Identifying Opportunities in Artificial Intelligence

- About the author

- Most popular articles

- Top Ten Usability Tools of 2019

PREVIOUS NEXT

July 28th, 2011

In Philosophy

No Comments

If you enjoy this article, see the other most popular articles

Paul Graham on cities and ambition

(written by lawrence krubner, however indented passages are often quotes). You can contact lawrence at: [email protected], or follow me on Twitter .

Damn, this might be the best essay that Paul Graham has ever written , and I’ve liked every essay that he’s ever written:

How much does it matter what message a city sends? Empirically, the answer seems to be: a lot. You might think that if you had enough strength of mind to do great things, you’d be able to transcend your environment. Where you live should make at most a couple percent difference. But if you look at the historical evidence, it seems to matter more than that. Most people who did great things were clumped together in a few places where that sort of thing was done at the time. You can see how powerful cities are from something I wrote about earlier: the case of the Milanese Leonardo. Practically every fifteenth century Italian painter you’ve heard of was from Florence, even though Milan was just as big. People in Florence weren’t genetically different, so you have to assume there was someone born in Milan with as much natural ability as Leonardo. What happened to him? If even someone with the same natural ability as Leonardo couldn’t beat the force of environment, do you suppose you can? I don’t. I’m fairly stubborn, but I wouldn’t try to fight this force. I’d rather use it. So I’ve thought a lot about where to live. I’d always imagined Berkeley would be the ideal place—that it would basically be Cambridge with good weather. But when I finally tried living there a couple years ago, it turned out not to be. The message Berkeley sends is: you should live better. Life in Berkeley is very civilized. It’s probably the place in America where someone from Northern Europe would feel most at home. But it’s not humming with ambition. In retrospect it shouldn’t have been surprising that a place so pleasant would attract people interested above all in quality of life. Cambridge with good weather, it turns out, is not Cambridge. The people you find in Cambridge are not there by accident. You have to make sacrifices to live there. It’s expensive and somewhat grubby, and the weather’s often bad. So the kind of people you find in Cambridge are the kind of people who want to live where the smartest people are, even if that means living in an expensive, grubby place with bad weather. …No matter how determined you are, it’s hard not to be influenced by the people around you. It’s not so much that you do whatever a city expects of you, but that you get discouraged when no one around you cares about the same things you do.

Post external references

- 1 http://www.paulgraham.com/cities.html

RECENT COMMENTS

February 8, 2022 9:33 am

From Michael S on How I recovered from Lyme Disease: I fasted for two weeks, no food, just water

"Did you have Bartonella, too? Seems it uses autogenesis..."

January 11, 2022 4:33 am

From Essie on Docker is the dangerous gamble which we will regret

"Once in 1990s, there are popular high performance solution called HPC software, many commercial softwares are ..."

December 17, 2021 7:32 pm

From John Carston on The ethics of being a high level tech consultant (a Fractional CTO)

"It helped when you mentioned that it is important to have a real connection with your consumer. My cousin ment..."

September 2, 2021 7:47 pm

From Mojavedfo on Where PHP regex fails

"55 thousand Greek, 30 thousand Armenian..."

August 7, 2021 9:53 am

From Colin Steele on The ethics of being a high level tech consultant (a Fractional CTO)

"Fantastic essay. Thoughtful, well-constructed, timely and applicable. I think every part-timer in the tech f..."

August 5, 2021 3:02 pm

From Rachiovwn on Where PHP regex fails

"consists of the book itself..."

October 19, 2019 3:08 am

From Bernd Schatz on Object Oriented Programming is an expensive disaster which must end

"I really enjoyed your article. But i can't understand the example with the interface. The example is reall..."

October 17, 2019 4:50 pm

From Anderson Nascimento Nunes on The conventional wisdom among social media companies is that you can’t put too much of the onus on users to personalize their own feeds

"Can't speak for anyone else, but on my feed reader: 5K bookmarked feeds, 50K regex on the killfile to filter o..."

October 10, 2019 11:17 am

From روابط: البث المباشر – صفحات صغيرة on RSS has been damaged by in-fighting among those who advocate for it

"[...] تاريخ تقنية RSS، مقال قديم ويلقي نظرة على الناس الذين طوروا التقنية [...]..."

October 9, 2019 3:08 pm

From Dan Campbell on Object Oriented Programming is an expensive disaster which must end

"Object-Oriented Programming is Bad https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QM1iUe6IofM..."

October 4, 2019 8:44 pm

From lawrence on My final post regarding the flaws of Docker / Kubernetes and their eco-system

"Gorgi Kosev, I am working to clean up some of my Packer/Terraform code so I can release it on Github, and then..."

October 4, 2019 5:14 pm

From Gorgi Kosev on My final post regarding the flaws of Docker / Kubernetes and their eco-system

"> Packer, sometimes with some Ansible. The combination of Packer and Terraform typically gives me what I ne..."

October 4, 2019 12:40 pm

"Gorgi Kosev, about this: "I would love if you could point out which VM based system makes it simpler and..."

October 4, 2019 7:31 am

"I won't list anything concrete that you missed, because that will just give you ammunition to build the next a..."

October 4, 2019 1:39 am

"Gorgi Kosev, also, I don't think you understand what a "straw man argument" is. This is a definition from Wiki..."

NO COMMENTS

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Copyright © 2010 Smash Company. All rights reserved. Mission Statement .

Paul Graham 101

There’s probably no one who knows more about startups than Paul Graham. Having helped thousands of startups through Y Combinator, the startup accelerator he co-founded, there’s a thing or two to learn from his essays. And Graham’s wisdom isn’t limited to startups either; his essays, read by millions, touch on education, intelligence, writing, society, the human mind, and much more.

I’ve read all of Paul Graham’s published essays (200+), ending up with enough notes to fill a book. This post tries to summarize the parts I’ve found most insightful and provide an accessible starting point for someone new to Graham.

Whenever possible, I’ve included links to his essays so you can easily go to the source when something interesting catches your eye. (Indeed, I recommend it - use this post as a gateway to the good stuff rather than a complete account in itself).

If my description of Graham’s idea sounds interesting, expect his essay to be 100x better. Always go back to the essays, where the ideas are fleshed out in full. This post is a very shallow overview.

Nevertheless, I hope this post inspires you to read Graham’s essays. They’re worth your time.

Boring disclaimer stuff:

- I made a Google Docs version of this post, in case that's easier to navigate.

- I’ve included all essays that were published before November 2021 ( Beyond Smart is the latest essay included). You can find a list of all essays on Graham’s site .

- The info included is based on my interests at the time of reading the posts. Had I read an essay a year earlier or later, I’d likely have included something else. Plus, with over 200 essays, I’ve just downright overlooked and forgot important stuff. Again, I recommend you explore the essays yourself.

- This post does NOT cover Paul Graham’s thoughts or essays on programming / coding. I’m simply not interested in or knowledgeable about that stuff, so I didn't think it fair to talk about it. He’s written a lot about coding, so if that’s your interest, explore his essays yourself.

- Finally, if something seem off or missing, let me hear about it and I’ll fix it: [email protected] / Twitter

Okay, let’s jump in.

Paul Graham on Startups

Unsurprisingly, many of Graham’s essays are startup-related. Given his experience on the topic, there’s a lot to unwrap, including some classics like “Ramen Profitable”, “Do Things that Don’t Scale” and “Maker’s Schedule, Manager’s Schedule”. Let’s start with an overview.

Startups in 13 sentences :

- Pick good co-founders.

- Launch fast.

- Let your idea evolve.

- Understand your users.

- Better to make a few users love you than a lot ambivalent.

- Offer surprisingly good customer service.

- You make what you measure.

- Spend little.

- Get ramen profitable.

- Avoid distractions.

- Don't get demoralized.

- Don't give up.

- Deals fall through.

For a detailed account, try How to Start a Startup .

This section presents some of Graham’s core ideas around startups, including the principles above.

Essays mentioned in this section:

Startups in 13 sentences

How to Start a Startup

Startup = Growth

How to Make Wealth

After Credentials

The Lesson to Unlearn

The Power of the Marginal

News from the Front

A Student's Guide to Startups

What Startups Are Really Like

Before the Startup

Hiring is Obsolete

Why to Not Not Start a Startup

The Hardest Lessons for Startups to Learn

Organic Startup Ideas

Six Principles for Making New Things

Frighteningly Ambitious Startup Ideas

Black Swan Farming

Crazy New Ideas

Why There Aren't More Googles

Ideas for Startups

Jessica Livingston

Startup FAQ

Earnestness

Relentlessly Resourceful

A Word to the Resourceful

The Anatomy of Determination

Mean People Fail

Why It's Safe for Founders to Be Nice

Design and Research

A Version 1.0

What Microsoft Is this the Altair Basic of?

Beating the Averages

Do Things that Don't Scale

Ramen Profitable

Default Alive or Default Dead?

Maker's Schedule, Manager's Schedule

Holding a Program in One's Head

How Not to Die

Disconnecting Distraction

Good and Bad Procrastination

Don’t talk to Corp Dev

The Top Idea in Your Mind

The Fatal Pinch

Startups are fundamentally different

Startups aren’t ordinary businesses. “ A startup is a company designed to grow fast ”, it is fundamentally different from your standard restaurant or hair salon. All decisions reflect this need to grow. Indeed, Graham says : “If you want to understand startups, understand growth”.

“Economically, you can think of a startup as a way to compress your whole working life into a few years. Instead of working at a low intensity for forty years, you work as hard as you possibly can for four. This pays especially well in technology, where you earn a premium for working fast.” (From How to Make Wealth )

Startups are also vastly different from your school experience. Your tests at school can be hacked, but success at startups is unhackable. At school, you learned that the way to get ahead is to perform well in a test, so you learned how to hack the tests . But in startups, you cannot really trick investors to give you money; the real hack is to be a good investment. You cannot really trick people to use your product; the real hack is to build something great. Valuable work is something you cannot hack.

So you don’t need to be a good student to be a good startup founder. In fact, if your opinions differ from those of your business teacher, that may even be a good thing (if your business teacher was excellent in business, they’d probably be a startup founder). In a startup, credentials don’t really matter - your users won’t care if you went to Stanford or got straight A’s. (Related: A Student's Guide to Startups ) .

Starting a startup is fundamentally different from a normal job , too. In a startup, experience is overrated . The one thing that matters is to be an expert on your users and the problem; everything else can be figured out along the way. “The most productive young people will always be undervalued by large organizations, because the young have no performance to measure yet, and any error in guessing their ability will tend toward the mean.” (From Hiring is Obsolete ). By starting a startup, you can figure out your real market value.

So, startups are fundamentally different from other companies, school and “normal work”. But why don’t more people start them? Graham has listed common excuses (and rebuttals) in Why to Not Not Start a Startup .

Startups are wealth-creation machines

So, startups are fundamentally different. You cannot really understand them by looking at other things. But what are they then?

Startups are one of the most powerful legal ways to get rich. If you’re successful, you can, in a few years, get so rich you don’t know what to do with all the money. But perhaps even better than the money is all the time a successful founder saves:

“Economically, a startup is best seen not as a way to get rich, but as a way to work faster. You have to make a living, and a startup is a way to get that done quickly, instead of letting it drag on through your whole life.” (From The Hardest Lessons for Startups to Learn )

In How to Make Wealth , Graham shows why startups are optimized for wealth-creation. (And for clarity, wealth is different from money: wealth is what people want, while money is merely the medium of exchange to get it. So a startup doesn’t actually create money, it creates wealth; in other words, it creates something people want, and people give money for that. This distinction may seem small but it’s important: “making money” seems really complicated while “making something people want” is far easier.)

Why are startups optimized for wealth-creation?

Leverage: If a startup solves a complex problem, it only needs to solve it once, then scale it infinitely with technology. So a startup, once it cracks the code, can create a lot of wealth rapidly.

Measurement: The performance of every employee in a startup is easier to measure than the performance of every employee in a big organization. So if you perform well and create wealth, you’re in a better position to get paid according to your value in a startup.

More detail in How to Make Wealth .

Good startup ideas come from personal need and they don’t sound convincing

While there are many ways you could get startup ideas, Graham has observed that most successful startups were founded because of a personal need. Fix something for yourself, and don’t even think that you’re starting a company. Just keep on fixing the problem until you find that you’ve started a company. (From Organic Startup Ideas )

He’s also observed that good ideas tend to come from the margins - places you’d not expect. The idea is often very focused - like a book store online or a networking site for university students - so it isn’t obvious how it would change the world; we dismiss the idea until it becomes obvious.

So, good ideas don’t initially sound like billion-dollar ideas - what even is a billion-dollar idea? Certainly not something we could recognize in advance. Indeed, the initial idea is usually so crude and basic that you’ll ignore it if you’re looking for a billion-dollar idea. The really big ideas may even repel you - they are too ambitious.

A good idea doesn’t sound convincing because, for no one to have already taken it, it must be a bit crazy or unconventional. “The most successful founders tend to work on ideas that few beside them realize are good. Which is not that far from a description of insanity, till you reach the point where you see results.” (From Black Swan Farming )

Indeed, when someone presents a crazy new idea to you, and if they are “both a domain expert and a reasonable person”, chances are that it’s a good idea (even if it sounds like a bad one). “If the person proposing the idea is reasonable, then they know how implausible it sounds. And yet they're proposing it anyway. That suggests they know something you don't. And if they have deep domain expertise, that's probably the source of it.”

Graham also emphasizes that it is not the idea that matters, but the people who have them.

Oh, and "Don't worry about people stealing your ideas. If your ideas are any good, you'll have to ram them down people's throats." ( Graham quoting Howard Aiken )

Nevertheless, if you’re in need of inspiration, Graham has some good starting points for coming up with startup ideas.

Founders make the startup

“ The earlier you pick startups, the more you’re picking the founders. ” Throughout his essays, Graham emphasizes the importance of the founders. More than anything - target audience, trends, TAM… - a startup’s success is influenced by the founders. (Obviously, the other employees matter, too. But founders are special, they are the heart and soul of the startup.)

“Cofounders are for a startup what location is for real estate. You can change anything about a house except where it is. In a startup you can change your idea easily, but changing your cofounders is hard.” (from Startups in 13 Sentences ).

Indeed, Graham notes that most successful startups tend to have multiple founders .

Earnestness and resourcefulness make a good founder

If the founders are the most important factor for a startup’s success, it is critical to understand what makes a good founder. Indeed, this is the topic of numerous essays.

According to Graham, a good founder is:

“The highest compliment we can pay to founders is to describe them as ‘earnest.’”

An earnest person does something for the right reasons and tries as hard as they can. The right reason usually isn’t to make a lot of money, but to solve a problem or satisfy an intellectual curiosity. This is why it’s important to figure out your intrinsic motivation or embrace your nerdiness (both of which we’ll discuss later).

“A couple days ago I finally got being a good startup founder down to two words: relentlessly resourceful.”

Relentless = make things go your way

Resourceful = adapt and try new things to make things go your way

Relentlessly resourceful people know what they want, and they will aggressively try things out and “hustle” until they get what they want. Consider the Airbnb founders and selling cereal .

Graham noticed a pattern around resourcefulness: when he talks to resourceful founders, he doesn’t need to say much. He can point them in the right direction, and they’ll take it from there. The un-resourceful founders felt harder to talk to.

It is not the most intelligent who succeed, but the most determined . Smart people fail all the time while dumb people succeed just because they decide they must.

"Make something people want" is the destination, but "Be relentlessly resourceful" is how you get there.

Oh, also: good founders aren’t mean. Mean People Fail and can’t get good people to work with them while startup founders who are nice tend to attract people to them .

Make something people want

If there’s one piece of startup advice to take from Graham, it’s this: “Make something people want”. (As you may know, this is also Y Combinator’s motto)

Yes, it is obvious. But it’s also pretty much the only thing that matters in a startup: if you just make something people want, you’ll attract users, employees, investors, money. “ You can envision the wealth created by a startup as a rectangle, where one side is the number of users and the other is how much you improve their lives .”

Indeed, many early-stage startups are “ indistinguishable from a nonprofit ”, because they focus so much on helping the users and less so on making money. Funnily, this approach makes them money in the long term.

“In nearly every failed startup, the real problem was that customers didn't want the product. For most, the cause of death is listed as ‘ran out of funding,’ but that's only the immediate cause. Why couldn't they get more funding? Probably because the product was a dog, or never seemed likely to be done, or both.” (From How to Start a Startup )

So how do you make something people want? Get close to users, launch fast, then iterate.

Get close to users

“The essential task in a startup is to create wealth; the dimension of wealth you have most control over is how much you improve users' lives; and the hardest part of that is knowing what to make for them. Once you know what to make, it's mere effort to make it, and most decent hackers are capable of that.” (From Startups in 13 Sentences )

“You have to design for the user, but you have to design what the user needs, not simply what he says he wants. It's much like being a doctor. You can't just treat a patient's symptoms. When a patient tells you his symptoms, you have to figure out what's actually wrong with him, and treat that.” (From Design and Research )

Since you may not precisely know who your users are and what exactly are their needs before you launch, it’s useful to yourself be a user of your product. If you use and like the product, other people like you may, too. This is why successful startups tend to arise from personal need.

Launch fast, then iterate

“The thing I probably repeat most is this recipe for a startup: get a version 1 out fast, then improve it based on users' reactions.”

The importance of iterations is highlighted in “ A Version 1.0 ”, “ What Microsoft Is this the Altair Basic of? ” and “ Early Work ”, among others. (If you understand the importance of iterations, then you understand that you must release a version 1 as soon as possible, so you can start iterating sooner.)

Some ideas from these essays:

- Don’t be discouraged by people’s ridicules of your early work. Just keep on iterating. (There will always be Trolls and Haters . Don’t mind them.)

- Don’t compare your early work with someone’s finished work. (If you wanted to compare your work to something, it’d optimally be a successful person’s early work. But people tend to hide their first drafts, precisely because they don’t want to be ridiculed.)

- When in doubt, ask: Could this really lame version 1 turn into an impressive masterpiece, given enough iterations?

Iterating and getting through the lame early work never gets easy. But Graham has listed some useful tips to trick your brain in “ Early Work ”.

Execution is a pathless land, but there is advice to be given

Mostly, a startup shouldn’t try to replicate what other startups do:

“If you do everything the way the average startup does it, you should expect average performance. The problem here is, average performance means that you'll go out of business. The survival rate for startups is way less than fifty percent. So if you're running a startup, you had better be doing something odd. If not, you're in trouble.”

Startup execution is a pathless land; there’s no formula to follow, even though many blog posts and thought leaders want you to believe otherwise. This is why it’s so important for the founders to be earnest and relentlessly resourceful: they need to figure it out themselves.

Even though there isn’t a connect-the-dots type of way to succeed in the startup world, Graham has observed hundreds (if not thousands) of startups from a very close distance, so he has identified general principles that help:

Do Things that Don’t Scale

“Think of startups not only as something you build and you scale, but something you build and force to scale.”

“Startups take off because the founders make them take off. If you don’t take off, it’s not necessarily because the market doesn’t exist but because you haven’t exerted enough effort.”

At some point, your startup may grow on autopilot. But before you’re there, you need to do seemingly insignificant things, like cold emailing potential clients, speaking to people at conferences or offering “ surprisingly good customer service ”.

The “Do Things that Don’t Scale” advice helps us remember that building something great is only one part of the equation; we must also do laborious, unscalable work to get initial growth, no matter how great the product is.

Get Ramen Profitable

Ramen profitability = a startup makes just enough to pay the founders’ living expenses.

“Ramen profitability means the startup does not need to raise money to survive. The only major expenses are the founders’ living expenses, which are now covered (if they eat ramen).”

Significance: Ramen profitability means that the startup turns from default dead into default alive . The game changes from “don’t run out of money” into “don’t run out of energy”. While running a startup is never not stressful, reaching ramen profitability does take a weight off your shoulders.

To increase your startup’s chances of succeeding, increase your chances of survival; to increase your chances of survival, reach ramen profitability.

Maintain a Maker’s Schedule

To get into the making/building mindset, you need big chunks of time with no interruptions. You can’t build a great product in 1-hour units in-between meetings; “that’s barely enough time to get started”. If you think of the stereotypical coder, they prefer to work throughout the night, probably because no one can distract them at 3am.

“When you're operating on the maker's schedule, meetings are a disaster. A single meeting can blow a whole afternoon, by breaking it into two pieces each too small to do anything hard in.”

If you want to create great stuff, you need to be mindful that a manager and a maker operate on very different schedules. If you’re the manager, try to give big blocks of time for the maker; if you’re the maker, try to schedule all meetings on two days of the week so the rest is free for creating.

Holding a Program in One's Head expands on some of these ideas.

What not to do

Graham has also figured out something about the inverse: what not to do. Or, as he puts it, “ How Not to Die ”.

- Keep morale up (don’t run out of energy)

- Don’t run out of money (for example, hire too fast)

- Don’t do other things. The startup needs your full attention. ( Procrastination is mostly distraction . Avoid distractions and you’ll avoid procrastination. Note, though, that you can procrastinate well .)

- Make failing unbelievably humiliating (to force you to give your everything)

- Simply don’t give up, especially when things get tough

To summarize this part on execution, here are Paul Graham’s Six Principles for Making New Things :

- Simple solutions

- To overlooked problems

- That actually need to be solved

- Deliver these solutions as informally as possible

- Starting with a very crude version 1

- Then iterating rapidly

The more you focus on money, the less you focus on the product

Graham doesn’t often talk about money, and when he does, I get this weird feeling. It’s like “sure, we’re talking about money... but I’d rather we talk about the product instead.” Let me explain:

In Don’t talk to Corp Dev , Graham says all a startup needs to know about M&A is that you should never talk to corp dev unless you intend to sell right now. So it’s better to focus on the product until you absolutely must think about M&A.

In The Top Idea in Your Mind : “once you start raising money, raising money becomes the top idea in your mind”, instead of users and the product. So your product suffers.

When you get money, don’t spend it . “ The most common form of failure is running out of money ”, and you can avoid that by not spending money, not hiring too fast.

One instance when you should think about money is if your startup is default dead . “Assuming their expenses remain constant and their revenue growth is what it has been over the last several months, do they make it to profitability on the money they have left?” If you know you’re default dead, your focus quickly shifts to turning the ship around and reaching profitability; avoiding The Fatal Pinch .

In the long term, it’s obvious that the company that focuses more on the users and product beats the company that obsesses over investors and raising money.

Paul Graham on What to work on

What to work on is one of the most important questions in your life, along with where you live and who you’re with. While Graham’s treatment of this question definitely leans on the side of startups, you can also view his ideas from the perspective of side hustles, hobbies, projects (in or outside of a career) and so on.

What Doesn't Seem Like Work?

Why Nerds are Unpopular

Fashionable Problems

How to Do What You Love

You Weren't Meant to Have a Boss

A Project of One's Own

Great Hackers

Follow intrinsic motivation

If it’s something you’re intrinsically motivated about, that’s something where you have infinite curiosity, and that’s something you’ll eventually do well in. (Later, we’ll discuss how curiosity leads to genius.)

“ If something that seems like work to other people doesn't seem like work to you, that's something you're well suited for. ” Put another way: the stranger your tastes seem to other people, the more you should embrace those tastes.

Because of the internet, you can make money by following your curiosity. This is a revolutionary shift : in the past, money was gained from a boring job, and you satisfied your curiosity during the weekends. But now, you can make real money just by following your curiosity, whether it’s from a startup or a YouTube or Gumroad account.